|

The History of Europe And the Church

The Relationship that Shaped the Western World

The historic relationship between Europe and the Church is a relationship that has shaped the history of the Western World.

Europe stands at a momentous crossroads. Events taking shape there will radically change the face of the continent and world.

To properly understand today's news and the events that lie ahead, a grasp of the sweep of European history is essential.

Only within an historical context can the events of our time be fully appreciated - which is why this

narrative series is written

in the historic present to give the reader a sense of being on the scene as momentous events unfold on the stage of history.

|

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

FOR three decades the illustrious Charlemagne has lain in his grave at Aachen. The great Emperor had revived the tradition of the Roman Caesars, and

shown Europeans the ideal of a unified Christian Empire in the West.

But Charlemagne's New Europe is not destined to endure. His

descendants have little of his genius. Charlemagne's quarrelsome grandsons

finally settle their differences; first with the

Treaty of Verdun

in 843, then in 870 with the

Treaty of Mersen.

The treaties

partition Charlemagne's Empire, foreshadowing the modern geography of Western

Europe. In its wake, a French realm and a German realm will slowly begin to

crystallize.

But for the moment the domains of the once-great Carolingian Empire

further disintegrate into warring principalities and kingdoms. The political

unity forged by Charlemagne goes completely to pieces. Europe is a shambles.

Europe's political weakness tempts outside powers, notably Norsemen,

Slays, Magyars and Saracens. Destructive raids from the north, east and south

place the vulnerable continent in imminent jeopardy. The Papacy, too, has sunk

to a miserable condition. Several Popes openly lead corrupt lives and are widely

despised by devout Catholic and non-Catholic alike. Battered and torn by

invasions and civil strife, Western civilization appears to be on a fast slide

downward. Throughout Europe the general mood is one of apprehension and

foreboding.

A great-grandson of Charlemagne is crowned Emperor by the Pope in 915.

After his death in 924, there is an imperial vacancy for nearly four decades.

Something must be done and quickly — to rescue Europe. Who will resist the

barbarian invaders and reimpose order on the fragmented West? The answer will

come from northeast of the Rhine — from the evolving power of Germany.

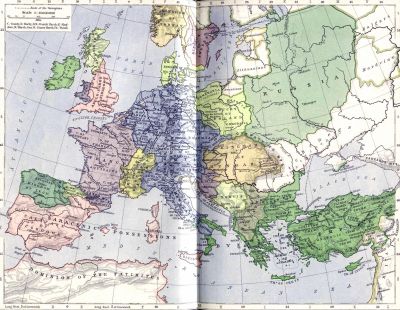

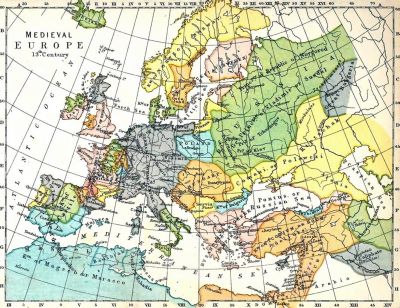

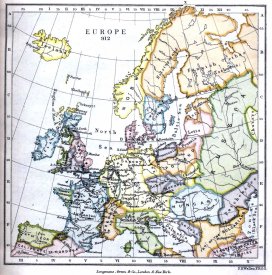

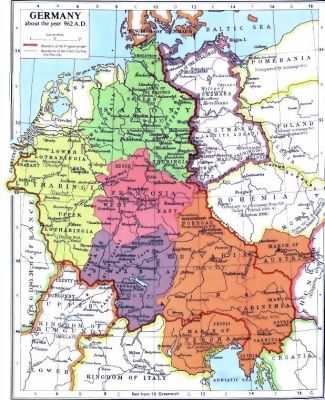

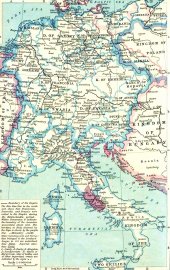

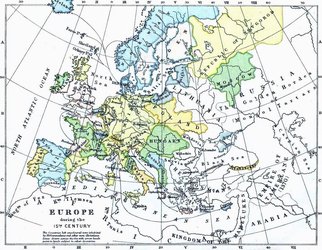

Europe in 900 A.D.

(click to enlarge) |

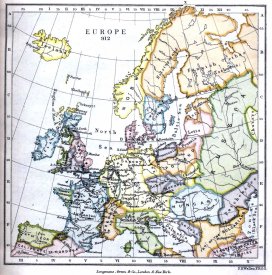

Europe in 912 A.D.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

There is no Emperor. But in Germany, kings still rule. The geographical

territory of Germany has become the dominant region of Europe. In 918 the

rulers of the great German duchies choose Henry the Fowler, duke of the Saxons,

as their king. He is called Fowler because he was laying bird snares when

informed of his election. Henry is founder of the Saxon dynasty of kings, which

will rule until 1024. He strengthens the German army and confronts the many

invaders threatening Europe. Upon Henry's death in 936, his 24-year-old son

Otto is elected king by the German dukes. The people raise their right hands to

show approval. "Sieg und Heil !" they shout — "Victory and Salvation !"

The archbishops of Mainz and Cologne crown Otto and hand him the

imperial sword with which to fight the enemies of Christ. Otto quickly

consolidates the German realm by suppressing rebellious nobles and ambitious

relatives. By bringing the duchies under centralized control, he unites

Germany under his rule. Otto also intervenes in Italian affairs. In 951 he

marches into war-torn Italy to assist Adelheid (Adelaide), the widow of an

Italian king being abused by her husband's successor. Otto declares himself king

of the Lombards and marries Adelheid, thereby becoming ruler of northern Italy.

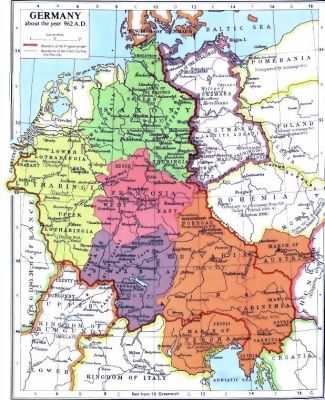

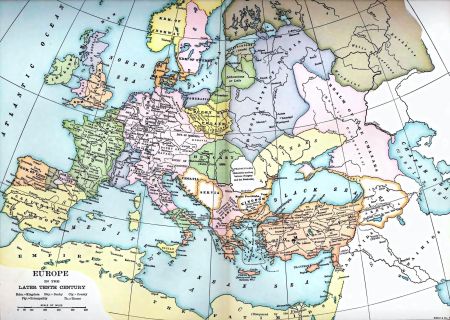

Germany About the Year 962.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In

August 955, Otto halts an invasion of the pagan Magyars (Hungarians), who have been

conducting annual raids on Germany for a few decades. In this momentous Battle of Lechfeld

(Augsburg), he delivers a decisive blow to the invaders. The Magyar menace is

ended, they raid no more. Otto can now rightfully claim the title "protector of Europe." He is

widely viewed as another Charles Martel, who stopped the Islamic Saracen advance

in Western Europe in A.D. 732. Otto was, in fact, a descendant of Charles Martel and of Charlemagne.

Meanwhile, the Papacy continues in tragic decline. Sergius III.

(904-911) gains the papal chair through murder and lives openly with the

prostitute Marozia. Their illegitimate son becomes Pope John XI. (931-935). Under

Pope John XII. (955-964), the Lateran palace becomes a literal brothel.

Rome, and all Italy, are in chaos. Pope John XII. appeals to Otto to

restore order to the peninsula and to assist him against his adversaries. In 961

Otto sweeps into Italy and defeats the enemies of the Pope. Pope John recognizes

Otto's position in Europe by crowning him Holy Roman Ernperor on February 2,

962. Not since that historic Christman Day in AD. 800, when the Western Roman

Empire was restored by the coronation of Charlemagne, has an event of such magnitude occurred.

Western Europe again has an Emperor !

Charlemagne's Empire is revived in an alliance between Emperor and

Church. With the support of the Church, Otto reigns supreme throughout Western

Christendom over the German Reich, or Empire.

The year 962 marks the restoration of the imperial tradition. Later

historians will view it as the beginning of what would later be officially

styled the Sacrum Roman urn Jmperiurn

Nationis Germanicae — the "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation."

(The full term will not be officially applied until the 15th century.)

Throughout the Middle Ages, the imperial title and German kingship will

remain indissolubly united. It will be the kings of the Germans, crowned by the

Pope, who will henceforth be named Holy Roman Emperors. Germany is the heart and

core — the power center — of the Empire.

The octagonal imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire is made

especially for the coronation of Otto in 962. For centuries to come, it will be

the very symbol of the concept of European unity.

The Empire of Otto the Great, Divided into Duchies 962 A.D.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Shortly after his coronation, Otto issues his controversial Privilegium

Ottonianum, ordering Pope John to take an oath of obedience to him. The Pope

rebels, and conspires with Otto's enemies. Late in 963 Otto calls a council at

St. Peter's in Rome, which deposes John for conspiracy and misconduct. Otto's

own candidate is now elected Pope in his place. Otto believes it is his duty to

preserve and strengthen Church institutions. He seeks to use the Church as a

stabilizing influence in Europe. But he also wants the Church subordinate to the

authority of the Empire.

On May 7, 973, Otto the Great dies and is buried in Magdeburg. He

leaves a peaceful and secure Empire. His son Otto II. (973-983) succeeds him. Otto III. — son

of Otto II. — is crowned as German king at Aachen late in 983. He is but 3

years old, so his mother and grandmother serve as regents. The king comes of age

in 994. Two years later he answers an appeal by Pope John XV. and puts down a

rebellion in Italy. By the time he reaches Rome, the Pope is dead. Otto then

secures the election of his cousin, Bruno of Carinthia, as Gregory V. He is the first German Pope.

On May 21, 996, Otto is crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Gregory. Otto

makes Rome the administrative center of the Empire and spends much of his time

there. In 998 Otto sets on his seal the inscription,

Renovatio imperii Romanorum — "Restoration

of the Empire of the Romans." Roman ideals are still strong in Western Europe.

Otto realizes that the united Europe he and his dynasty have envisioned must

have a worthy religious head. The Papacy must be raised to a position of

European esteem. Its influence must be revived.

When Pope Gregory V. dies in 999, Otto nominates his former teacher, the

scholar Gerbert of Aurillac. Gerbert becomes Pope, with the name Sylvester II.

He is the first French Pope. Both Sylvester and Otto dream of an Empire in which

Emperor and Pope would serve as joint heads of a unified entity. Gerbert strives

to raise the reputation of the Papacy throughout Europe. He denounces some of

his unworthy predecessors as "monsters of more than human iniquity," and as

"Antichrist, sitting in the temple of God and playing the part of God." Otto

hopes for a harmonious alliance of future Emperors and Popes. But it is not to be so.

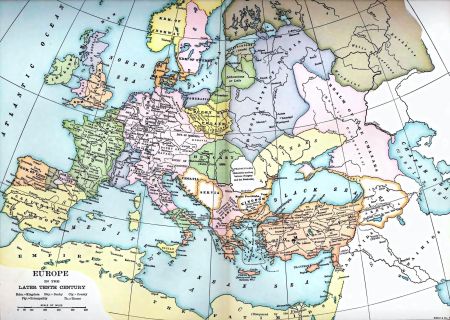

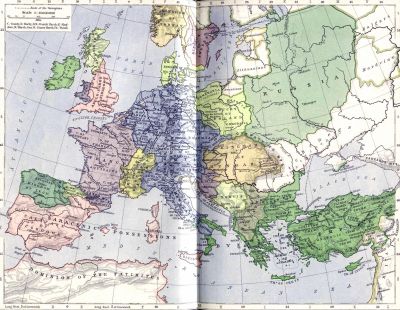

Europe in the Late 10

th Century.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Henry II. (1002-1024) is the last of the Saxon rulers of Germany. At his

death, Conrad II., duke of Franconia, receives the imperial crown. Conrad II.

(1024-1039) is the first Franconian or Salian German Emperor. His reign begins

what later historians will call the great period of the Holy Roman Empire. The

reign of Conrad's son Henry III. (1039-1056) marks the zenith of German imperial power.

It is during the reign of Henry III. as Holy Roman Emperor that the

final schism between the Westerm (Roman) and Eastern (Orthodox) churches takes

place. The break had existed for centuries and had grown progressively wider. In

1054 it becomes formal and complete when the Pope at Rome and the Patriarch of

Constantinople excommunicate each other. Not long afterward comes another

important development in the religious sphere. In 1059 Pope Nicholas II. convenes

the Lateran which decrees that future Popes will be elected by a college (group

or body) of cardinals. This action takes away the Emperor's influence in Papal

elections. The decree of the Lateran Council sparks a major rupture between

Germany and Rome. Now begins the great medieval struggle between the Empire and Papacy.

Europe and the Byzantine Empires 1000 A.D.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Henry III. is succeeded by his young five year old son Henry IV.

(1056-1106). He will play a mojor role in one of the most famous episodes in medieval history — a

personal confrontation between Pope and Emperor.

The Archbishop Hanno of Cologne had once kidnapped the boy-king from his mother.

Archbishop Adalbert of Bremen eventually secured the golden boy; then Archbishop Hanno recovered the royal pawn again.

These were the two leading prelates of Germany and it is said about them;

both were fierce and ambitious bishops who hesitated at nothing to attain their end, whether by fraud or violence.

The crowning of Charlemagne in

AD. 800 by Pope Leo III. had initiated a close alliance between Pope and Empire.

This "marriage" had formally linked the spiritual power of the Pope with the

temporal power of the Emperor. The Empire is thereafter regarded as God's chosen political organization

over Western Christendom. The Church at Rome is viewed as God's chosen instrument in

religious matters. Pope and Emperor are regarded as God's appointed

vice-regents on earth. This concept perhaps will be best summarized late in the

19th century by Pope Leo XIII.:

"The Almighty has appointed the charge of the

human race between two powers, the ecclesiastical and the civil, the one being

set over divine, the other over human things."

Leo will also point out that

"Church and State are like soul and body

and both must be united in order to live and function rightly."

This intimate

alliance of Church and State serves the needs of both institutions. The Empire

exercises its political and military powers to defend religion and enforce

religious uniformity. The Church, in turn, acts as a "glue" for Europe, holding

together the differing nationalities and cultures within the Empire by the tie

of common religion.

As Leo XIII. will also note in retrospect,

"The Roman Pontiffs, by the

institution of the Holy Empire, consecrated the political power in a wonderful manner."

This harmonious ideal in Church-State relations, however, is never

completely realized. The respective powers and privileges of Church and Empire

are not clearly defined. The result is frequent conflict between Emperor and

Pope for the leadership of Christian Europe.

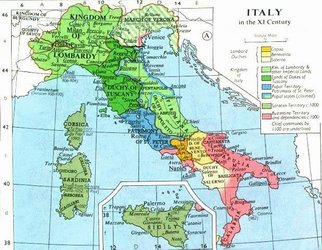

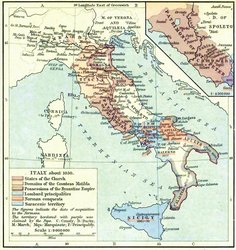

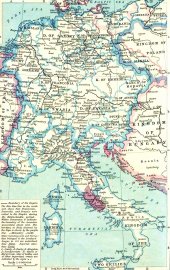

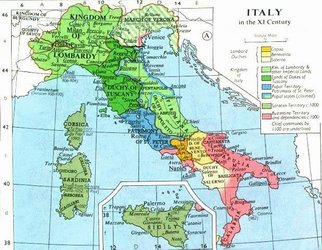

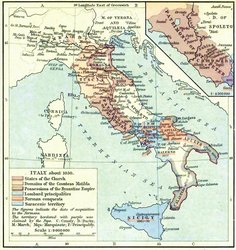

Italy in the 11th Century.

(click to enlarge) |

Italy About the Year 1050.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Pope Gregory VII. comes to the Papal throne in 1073. He leaves no doubt

as to his position. "The Pope is the master of Emperors!" he declares. A stern

idealist, Gregory is determined to subordinate the authority of the Emperor to

that of the Pope. Gregory insists that the Pope is above all nations and

independent of every temporal sovereign, responsible only to God. The supremacy

of Church over Empire, he asserts, is symbolized by the traditional crowning of

the Holy Roman Emperors by the Popes in Rome — publicly demonstrating that all

political power comes from God by way of the Roman Pontiff.

Henry IV is not impressed by such arguments. He becomes embroiled in a

bitter dispute with Pope Gregory. The controversy focuses on an issue that has

been a continuing irritant in Church-State relations: lay investiture. The

question is whether secular rulers should be able to appoint bishops and abbots

and invest them with symbols of spiritual authority. Emperors have long used — and

abused — such control over Church offices to their own ends. Gregory wants it to

stop.

Henry defies the Pope, denounces him and attempts to have him deposed.

The headstrong Henry ends a letter to Pope Gregory with the curse, "Down, down,

to be damned through all the ages!" Gregory is not intimidated. The controversy

now escalates. It is a life-and-death struggle between the Papacy and German

imperial power! Gregory is determined to free the Church from secular control.

He finally excommunicates the unyielding Henry. This action absolves all Henry's

subjects from their oaths of allegiance to the Emperor, and triggers a baronial revolt in Germany.

Henry's demise appears imminent. He now sees clearly that imperial

power depends on the support of the Church. To save his throne, Henry must make

peace with the Pope. In January 1077, Henry journeys to a castle at Canossa in

northern Italy where Pope Gregory is temporarily staying. For three days the

Emperor humiliates himself by standing barefoot and in sackcloth in the snow

outside Gregory's window. Gregory finally grants absolution, and Henry is reconciled to the Church.

The imperial capitulation at Canossa comes to symbolize the submission

of the State to the Church. But it is only a temporary victory for the Church.

Soon after Canossa, the struggle breaks out again. In 1122 the Concordat of

Worms ends a bitter contest between Holy Roman Emperor Henry V (1106-1125) — Henry

IV.'s son — and Pope Calixtus II. (1119-1124). It settles the Investiture

Controversy by stipulating that an Emperor can still

nominate bishops and abbots, but

the clergy will do the actual choosing and can refuse approval of an Emperor's

nominees. Emperors are permitted to confer upon new bishops only the temporal

insignia of their offices, due them in their position as vassals of the crown.

The spiritual symbols the ring and staff — can be bestowed only by the Church.

Even after this compromise, the struggle for supremacy between Empire

and Papacy will continue for centuries. But despite their incessant rivalry, the

Papacy and Empire will remain closely associated throughout the Middle Ages.

Their mutual need for each other will override disagreements of lesser

importance.

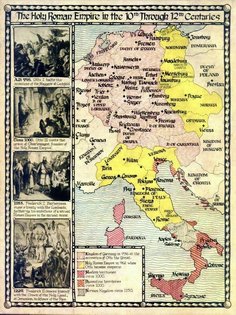

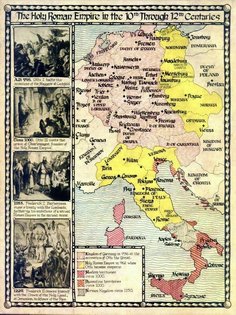

Germany from the the 10th to the 12th Century

Under the Saxon and Franconian Houses.

(click to enlarge) |

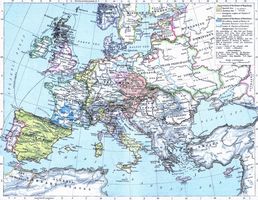

The Holy Roman Empire in the 10th Through 12th Centuries.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

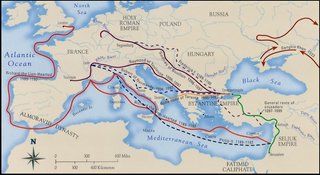

The power and influence of the Papacy at this time is evidenced by the

popular reaction to the Papal call, late in 1095, for the First Crusade. Pope

Urban II exhorts Christians throughout Europe to come to the aid of the

Byzantine Emperor, who is threatened by advancing Turks, and to free holy

Jerusalem from the "legions of Antichrist" the Moslems. Reaction to Urban's plea

is extraordinary. The outpouring of popular enthusiasm for the cause sets in

motion a succession of military expeditions to the Holy Land that will continue

for two centuries before ending in dismal failure. And for a time, the prestige

of the Papacy is greatly enhanced by this wave of religious fervor.

But the prestige and power of the Holy Roman Emperor has taken a turn

for the worst. The Emperor's power has been seriously weakened by the lay

investiture struggle. With the death of Henry V. in 1125, Germany and the Empire

are beset by civil strife and chaos. Many fear the Empire will fall completely

to pieces.

Two rival dynasties of German nobles scramble to gain the imperial

throne — the Welfs (or Guelphs) and the Hohenstaufens. The Hohenstaufens are

descended from Henry IV. in the female line. Finally, in 1138, Conrad III. comes

to the German throne. Conrad — a grandson of Henry IV and nephew of Henry V. — is the

first king of the Hohenstaufen family. The Hohenstaufens will preside over the Empire until 1268.

Conrad is followed, in 1152, by his nephew Frederick, who will be known

to history as Frederick I. Barbarossa ("Red Beard"). Frederick is formally

crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Adrian IV. in Rome on June 18, 1155. He will

reign for nearly four decades. Frederick Barbarossa considers himself the

spiritual heir of his predecessors, Charlemagne and Otto the Great (from whom he

is also descended physically), and of the great imperial tradition. His desire

is to restore the glory of the Roman Empire. As a later chronicler will observe,

"During all his reign nothing was dearer to his heart than the reestablishment

of the Empire of Rome on its ancient basis."

Frederick imposes order on Germany, and intervenes in Italian and Papal

politics. This sparks a renewal of the imperial conflict with the Papacy in the

form of a bitter feud with Pope Adrian. As had many of his predecessors,

Frederick seeks to make the Church subordinate to the authority of the Empire.

When asked from whom his imperial office is received, Frederick declares to Papal legates,

"We hold our kingdom and our empire not as a fief of the Pope

but by election of the princes from God alone."

Pope Adrian counters,

"What were the Franks till Pope Zacharias

welcomed Pepin? The chair of Peter has given and can withdraw its gifts!"

Frederick realizes, however, that a full-blown feud with Rome could have

disastrous consequences.

In 1177 he publicly makes peace with Adrian's successor, Pope Alexander III. But the peace is to be short-lived.

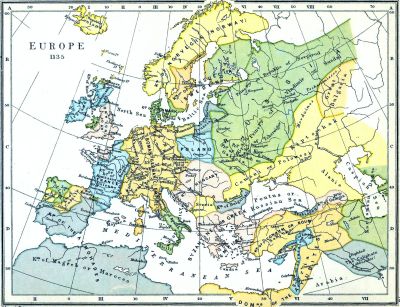

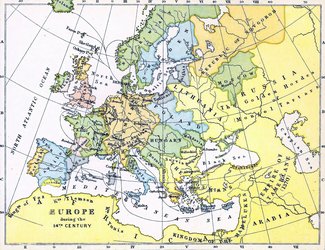

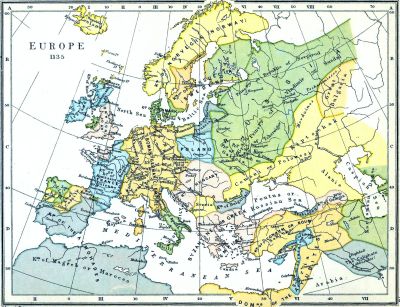

Europe in 1135.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Emperor Frederick Barbarossa dies by accidental drowning in 1190, while

leading the Third Crusade. His son, Emperor Henry VI. (1190-1197), further

strengthens the Hohenstaufen Empire. But after his death, civil war erupts in

Germany. In 1212 a new German king finally emerges from the chaos. He is

Frederick II., Frederick Barbarossa's grandson. In 1215 Frederick II. is crowned

Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Innocent III. It is under Innocent III. (1198-1216)

that the Church reaches the height of its medieval power. Virtually every

European nation feels the power of this Pope. Innocent seeks to reduce the

Empire to a plaything of the Pope. He asserts that kings derive their powers

from the Pope, just as the moon derives its light from the sun. Innocent declares that the Pope is

"less than God but more than a man."

"No king can

reign happily," Innocent claims, "unless he devoutly serves Christ's vicar."

Emperor Frederick II. does not openly quarrel with Innocent III. He

does, however, wage a fierce struggle with later Popes, notably Gregory IX.

(1227-1241). Frederick's ambition is to rule all of Italy, including Rome. This

desire for full control of Italy brings him into direct conflict with the

Papacy. Frederick is finally excommunicated by Pope Gregory, who calls the

Emperor a heretic and the personification of Antichrist.

"Out of the depths of

the sea rises the beast," shouts Gregory in a reference to Revelation 13, "filled

with the names of blashemy ......... Behold the head, the middle and the end of

this beast, Frederick, this so-called emperor." Pope Gregory also speaks of

Frederick as "this scorpion spewing poison from the sting of his tail."

Frederick lashes back, labeling Pope Gregory the Antichrist. "The Roman Church

has never erred," Gregory counters. "To resist it is to resist God!"

The Papacy and the "viper brood" of Hohenstaufens are locked in a

mortal struggle. In its wake, the last remnants of imperial power will be damaged almost beyond repair.

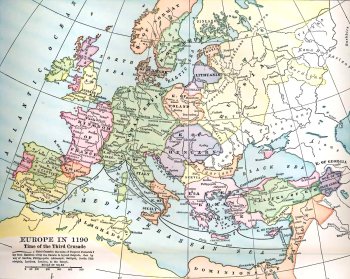

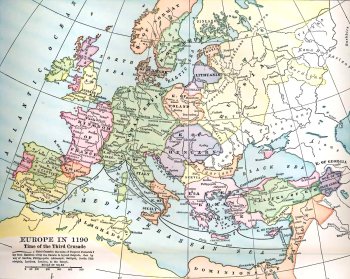

Europe in 1190, Time of the 3rd Crusade.

(click to enlarge) |

Europe and the Holy Roman Empire

Under Hohenstaufen from 1138 to 1254.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Frederick II.

dies in 1250. He is the last of the great Hohenstaufens. With his death, the

Empire crumbles. The last of the German Hohenstaufen dynasty is Conradin, grandson of Frederick II.,

whose father Conrad IV. is excommunicated in 1254 and dies of malaria that same year, Conradin is only two.

The long confrontation with the late Hohenstaufen Frederick II. devolves into interurban struggles

between nominally pro-Imperial Ghibellines and even more nominally pro-papal Guelf factions,

in which Frederick II.'s heir Manfred, a son of Frederick II. and uncle to Conradin, is immersed.

Any Hohenstaufen in Sicily is bound to have claims

over the cities of Lombardy, and as a check to Manfred, Pope Urban IV., 1261-1264, introduces Charles of Anjou

into the equation, to place the crown of the Two Sicilies in the hands of a monarch amenable to papal control.

For two years Urban IV. negotiates with Manfred regarding whether Manfred will aid the Latins in regaining

Constantinople in return for papal confirmation of the Hohenstaufen rights.

Meanwhile the papal pact solidifies with Charles. Charles promises to restore the annual census

or feudal tribute due the Pope as overlord, some 10,000 ounces

of gold being agreed upon, while the Pope will work to block Conradin from election as King of the Germans.

Pope Urban IV. writes a letter suggesting that by "immemorial custom",

seven princes have the right to elect the King and future Emperor.

In 1265 the new Pope, Clement IV., forms an alliance with Charles of

Anjou, the brother of the king of France, in which he offers Charles the kingdom

of Sicily as a reward for ridding Italy of the Hohenstaufens. By 1268 the

Hohenstaufen forces are defeated. Young Conradin, at the age of 16 is beheaded in the public

marketplace at Naples with his 19 year old friend Frederick I. of Baden who had years earlier fled

his fief for fear of his safety from the king of Bohemia.

The Papacy has won its victory over the Hohenstaufens. The dynasty is

extinct. But the Papal victory has brought political instability to Germany.

Germany becomes more a geographical term than a nation. It is a loose

confederation of separate princes. The German king has become one of the weakest

rulers on the Continent. The Great Interregnum (1254-1273), as this period will

be known to history, is a stormy and confused period. It is the kaiserlose,

schreckliche Zeit "the terrible time without an emperor." Western Europe is now

about to enter a new phase. The Great Interregnum comes to an end in 1273. In

that year, the imperial crown is revived and given to the Austrian Count Rudolf

of Habsburg. The Empire now has an Austrian head.

Rudolf's ancestors — of Trojan and Merovingian descent — had built a family

castle in Switzerland in the 11th century. They had called it

Habichtsburg — Castle of the Hawk. Hence, the word Habsburg. Rudolf is the first

Habsburg to ascend the imperial throne. He will succeed in establishing some

degree of order within the Empire. The House of Habsburg will play a leading

role in European affairs for centuries to come. The ideal of universal

rule — unity under a single authority — is by no means dead.

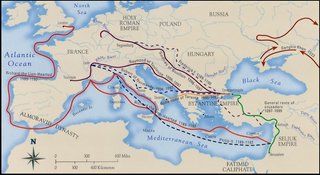

Crusades of the 11th and 12th Century.

(click to enlarge) |

Crusades from 1202 to 1270, including those of Frederick II and Louis IX.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

THE TWO decades of anarchy known as

the "Great Interregnum" (1254-1273) leave Germany in political ruins.

It is the "terrible time without an emperor" or

as the Germans word it, die kaiserlose, schreckliche Zeit.

A new period of German history begins when the German princes assemble

at Frankfurt in the early autumn of 1273 and elect a Swiss count as German king.

He is Rudolf of Habsburg. Three weeks later — on October 24, 1273, Rudolf is

crowned at the city of Aachen, Charlemagne's old capital. Late the following

year he is recognized by Pope Gregory X.

Rudolf is the first Habsburg to hold the office of Holy Roman Emperor,

though French influence in Rome prevents him from being officially crowned as

such by the Pope. Rudolf rebuilds Germany from the ruins left by the Great

Interregnum. He suppresses the lawless robber knights at home and restores

German prestige abroad. He also consolidates and adds to Habsburg ancestral

lands, laying a solid foundation for future Habsburg greatness.

The major development in this regard comes in 1278, when Rudolf drives

the non-German Ottocar, king of Bohemia, from Austria. Additionally, he made his

twelve-year-old son Rudolf Duke of Swabia, which had been without a ruler since Conradin's execution.

This victory establishes the Habsburg dynasty as the territorial rulers of Austria, which emerges as one

of the most powerful of the German states. It will become the territorial nucleus of future Habsburg power.

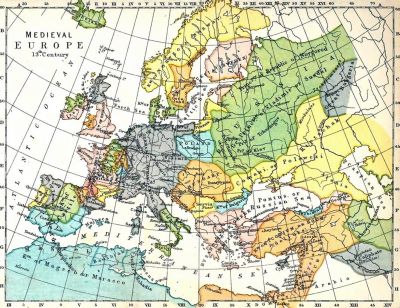

Medieval Europe in the 13

th Century.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Rudolf I of Habsburg dies in July 1291. The German Imperial Electors

— German princes who take part in choosing the Emperor — are concerned over the

rapid rise of the Habsburgs. They therefore refuse to recognize the claims of

Rudolf's son, and instead recognize Adolf of Nassau as king of Germany. A

century and a half will pass before the next Habsburg sits on the imperial

throne.

Meanwhile, in 1355, Charles IV. of Luxembourg (now the German king and

king of Bohemia) receives the crown of the Holy Roman Empire in Rome. In an

effort to check growing political disorder, he issues the following year an

imperial edict known as the "Golden Bull." This document spells out a precise

procedure for the election and coronation of a German king.

Seven German nobles called Kurfürsten,

Prince-electors, including the Duke of Saxony, the margrave of Brandenburg, the King of Bohemia,

Count Palatine of the Rhine, and the archbishops of

Trier, Cologne and Mainz will henceforth determine who is to be king of the Germans —

the "king to be promoted emperor". Election is to

be by majority vote. The Golden Bull becomes the constitution of the Holy Roman

Empire, and will remain its fundamental law for 4½ centuries, until 1806.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Noticeably absent in the Golden Bull is a role for the Papacy. Papal

confirmation is no longer a necessity in the election process. Things have

deteriorated rapidly since the pontificate of Innocent III., when the Church

seemed unassailable in its prestige and power. Some years before the Golden

Bull, Pope Boniface VIII. (1294-1303) is sensing a rising national consciousness

and development of a new type of secular authority in Western Europe. He

realizes this could be dangerous to the Church and attempts to reassert Papal

power over the new forces of nationalism.

His bull Clericis Laicos (1296)

forbids kings, under penalty of excommunication, to tax the clergy

without Rome's consent. In another bull, Unam Sanctum (1302),

Boniface asserts that to obtain salvation, every man

must be subject to Rome. In the same document, he declares the supremacy of the Pope over all kings:

"Both swords, the spiritual and the material, are in the

power of the Church; the one to be wielded for the Church, the other by the

Church; the one by the hand of the priest, the other by the hand of kings and

knights, but at the will and sufferance of the priest. One sword, moreover ought

to be under the other, and the temporal authority to be subjected to the spiritual."

But this vigorous assertion of Papal power and rights comes too late.

By the end of Boniface's reign, the Papacy is no longer able to withstand the

growing independence in the secular realm. Unam Sanctum

receives violent opposition from many quarters, most

notably from Philip the Fair of France. In a letter to Boniface, the French king

dares to refer to the pontiff as "Your Supreme Foolishness."

The Papacy is on a downward slide. With each passing year, it becomes clearer to all

that the days when the Papacy could command are gone. Now it can only influence and advise.

Italy in the 12

th and 13

th Centuries.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Because of the unsettling political conditions in Rome,

Pope Clement V. (1305-1314) takes up residence at the city of Avignon, a Papal possession in

France, in 1305. There he is subject to powerful French influence.

For just more than 70 years — from 1305 to 1377 — the Popes remain at

Avignon. The Papacy becomes a tool of the French court. This period will be

called the "Babylonian Captivity" of the Church — an allusion to the 70-year exile

of the Jews to Babylon in the sixth century B.C. The loss to Papal prestige is

enormous. Leadership in Europe has clearly passed from the Pope to secular rulers.

The German princes believe that Rome is the only rightful capital for

the Church. Finally, in 1377 Pope Gregory XI. (1370-1378) returns to Rome from

Avignon, ending the "Babylonian Captivity." He dies the next year.

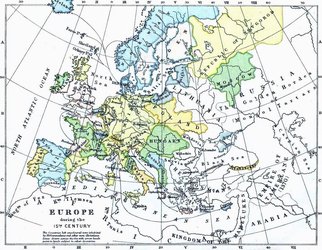

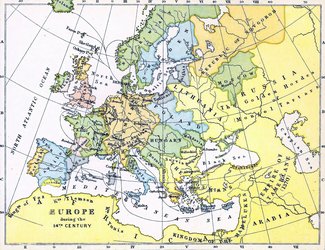

Europe in the 14th Century.

(click to enlarge) |

Europe in 1360.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Urban VI., an Italian, is elected as Pope by popular demand in 1378. But

French cardinals hold that the election of Urban is invalid because of outside

pressure on the voters. A Frenchman, Clement VII., is elected Pope and rules from

French-dominated Avignon. There are now two Popes !

Each excommunicates the other as the "Antichrist."

The states of Europe support one or the other according to political considerations.

The Papacy is rent asunder. Each section of Christendom declares the

other "lost." Many are uncertain which claimant actually possesses Papal

authority. For nearly four decades, Western

Christendom is divided. History will refer to the situation as the

"Western Schism" (or "Great Schism" though this

term is more often applied to the East–West Schism of 1054).

Neither Pope will abdicate. Neither will arbitrate differences.

In 1409, cardinals from both camps meet at the Council of Pisa. They

seek to end the schism by deposing both pontiffs and electing a third man,

Alexander V. But the two "deposed" Popes refuse to resign. Now there are

three claimants to the Papal chair! This intolerable situation is finally rectified in 1417.

The Council of Constance deposes the three rival Popes and unanimously elects Pope Martin V.

The Great Schism is ended, but the Papacy has suffered irreparable loss of prestige.

Western Schism from 1378 to 1417

Allegiances to Multiple Popes.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

By the 15th century, Germany is a jumble of virtually independent

duchies, arch-duchies, margravates, counties and free cities — collectively known

as "the Germanies." There is no real "Germany" in a unified sense. The German

king reigns, but does little ruling.

Otto the Great had started Germany on the way to becoming a

strong, unified state, but it did not work out as he had planned.

During the decades of trial for Western Europe and the Church, an

influential family has been working quietly behind the scenes. It has added to

its ancestral land holdings and consolidated its power base. It is now ready to

make its great influence felt. That family is the House of Habsburg. Having been

held by members of the House of Luxembourg from 1347 to 1437, the German

imperial crown now comes again into the possession of the Habsburgs. In 1438,

the Habsburg Albert II of Austria is made king of Germany. He is recognized as

Holy Roman Emperor, but is not crowned.

Henceforth, the imperial title will be hereditary in the Habsburg

family. Despite this, the office is not legally hereditary, and the heir can not title himself

"Emperor" without being personally elected.

The House of Habsburg is on its way to becoming the most potent

political force in Europe. In 1440, Frederick III., a cousin of the now-deceased

Albert II., is named German king. A dozen years later he is crowned Holy Roman

Emperor in Rome by the Pope. He will be the last Emperor to be crowned in that

city. The deteriorating position of Rome in European affairs is thus further

highlighted. Frederick III. has a mysterious royal monogram: the vowels of the

alphabet (A.E.I.O.U.). Its meaning? They are the first letters of the words

Austriae est imperare orbi universo — "All

the world is subject to Austria." The House of Austria — the

Habsburg dynasty — has indeed set high goals !

Central Europe in 1477.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In 1453, the Ottoman Turks under

Mohammed the Conqueror capture Byzantium (Constantinople), ending the

Eastern Roman Empire. After centuries of decline, the last vestige of the Roman

Empire in the East is gone. Many historians will later regard 1453 as the ending date for the Middle Ages.

Maximilian I. of Habsburg, son of Frederick III., becomes Emperor in 1493.

He envisions himself as a new Constantine. His mission is to save Christendom from the scourge of the Turks.

By a calculated policy of dynastic marriages, the Habsburgs strengthen

and enlarge their power. The marriage of Maximilian to Mary of Burgundy, heiress

of the Netherlands, adds the Dutch kingdom to the Habsburg domains. A son of

this marriage, Philip, later marries Joanna (Juana), daughter of Ferdinand and

Isabella of Spain. Juan, the only son of Ferdinand and Isabella, marries

Maximilian's daughter Margaret, linking Castile and Aragon in Spain with Austria.

Europe During the 15th Century.

(click to enlarge) |

Europe in 1490.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

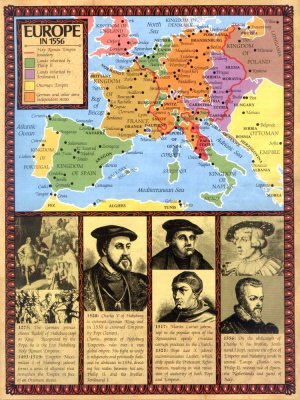

It is now the year 1500. A son is born to Joanna and Philip. They name

him Charles. To history, he will be Charles V. greatest of Habsburg emperors.

Charles is elected king of Germany in 1519, following the death of his

grandfather Maximilian. He is crowned at Aachen in October 1520. At the same

time he assumes the title of Roman Emperor-elect. But he is not immediately

crowned Holy Roman Emperor. That event will not come for another decade. In the

person of Charles the Spanish dominions are united with the Habsburg possessions

in the Netherlands, Austria and elsewhere in Europe. Never had any monarch so many possessions!

Charles has more than 60 royal and princely titles, including king of

Germany, archduke of Austria, duke of Burgundy, king of Castile and Aragon, king

of Hungary — to name just a few. Spain is, in itself, an empire — a global

empire, with colonial territories even in the New World. The Empire of Charles V. stretches from

Vienna to Peru! Charles declares, "In my realm, the sun never sets." And it is so !

The Habsburgs' holdings constitute the world's first truly great modern empire. Many observers begin to believe

that the growth of sovereign nation states might be halted, and a universal

Christian empire achieved in Europe! But other forces are already at work that

will ultimately thwart this Habsburg dream.

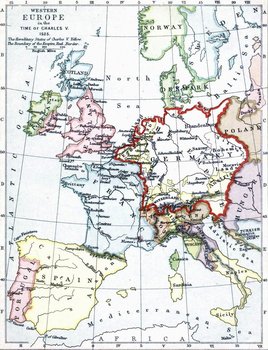

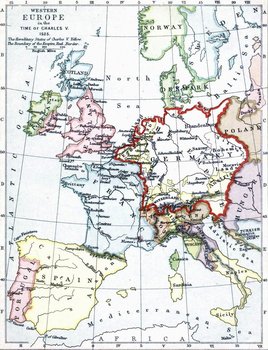

Western Europe in the Time of Charles V. 1525.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The spirit of the Middle Ages has been one of faith and devotion to

institutions. The individual has

not been considered very important in the vast scheme of things. But now a

change is in the wind. A movement had begun in Italy in the 14th century

known to history as the Renaissance ("rebirth"). It is a great reawakening of

interest in the literature and philosophy of ancient Greece and Rome. It is

marked by a flowering of the arts, a turning toward an appreciation of worldly

things and a lively interest in secular affairs. Man is now growing conscious of

his own importance. The present world, rather than the "next world," is becoming

the chief concern. The Renaissance brings a new spirit — a pagan spirit, as some

contemporary critics describe it. It is a questioning and critical spirit, a

spirit of skepticism.

Not surprisingly, this new spirit spawns a revolt against time-honored

institutions, including the Church. The Church's ideals no longer command the

same respect among the population at large. The personal lives of the Popes of

this period don't help the situation. Renaissance Popes such as Alexander VI.

(1492-1503) — formerly Rodrigo Borgia of the noted Borgia family lead corrupt

lives, neglecting affairs of the Church in pursuit of personal pleasures. He fathers four, and possibly five children.

Lucrezia, his daughter, has her betrothal and wedding ceremonies at the Vatican Palace. His son

Cesare, then only eighteen years old, he made a cardinal; and despite this Cesare wars incessantly for years afterwards.

The critical spirit of the Renaissance spreads from Italy northward to

the German universities. There, discontent with ecclesiastical corruption and

immorality grows rapidly. And there, early in the 16th century, religious

dissidents finally find a champion.

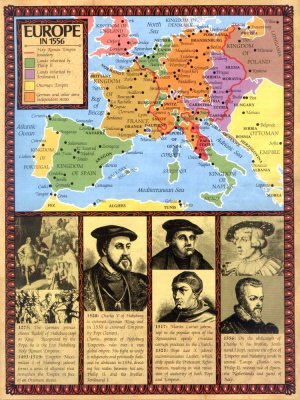

Europe in 1556 - (click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In 1511, a German monk and educator named Martin Luther makes a

pilgrimage to Rome. He is appalled at the corruption and vice he finds so openly

practiced there. He has often heard the popular proverb, "If there is a hell,

Rome is built over it." Now he believes it.

After his return to Germany, Luther is further disturbed by the

practice of selling Papal indulgences, or pardons for sin. The profitable

selling of indulgences has become big business in many parts of Europe.

On October 31, 1517, Luther nails a document to the door of the court church at

Wittenberg, Germany. On it are his "Ninety-Five Theses" in criticism of selling

Papal indulgences. The documents are forwarded to Rome. In June 1520, Pope Leo X

issues a Papal bull criticizing Luther's teachings.

On December 10, 1520, Luther publicly burns the Papal bull. An

ecclesiastical revolution to be known as the Protestant Reformation is now in

full swing! It will spread like wildfire over Germany and beyond. Luther is

excommunicated in January 1521. Soon afterward, he is summoned by Emperor

Charles V, a devout Catholic, to appear for a hearing before the Diet (assembly)

of Worms, a German city on the Rhine. But it is already too late to arrest the

movement. The assembly settles nothing. Luther refuses to recant — and Charles

declares war on the protestors.

A few of Luther's protestations against the popish indulgences are given, as specimens of the whole.

21. The commissioners of indulgences are in error in saying that, through the indulgence of the Pope, man is delivered from all punishment, and saved.

27. Those persons preach human inventions, who pretend that, at the very moment when the money sounds in the strong box, the soul escapes from purgatory.

28. This is certain: that as soon as the money sounds, avarice and love of gain come in, grow, and multiply. But the assistance and prayers of the church depend only on the will and good pleasure of God.

32. Those who fancy themselves sure of their salvation by indulgences, will go to the devil with those who teach them this doctrine.

36. Every Christian who feels true repentance for his sins, has perfect remission from the punishment and from the sin, without the need of indulgences.

37. Every true Christian, dead or living, is a partaker of all the riches of Christ, or of the church, by the gift of God, and without any letter of indulgence.

46. We must teach Christians, that if they have no superfluity, they are bound to keep for their families wherewith to procure necessaries, and they ought not to waste their money on indulgences.

50. We must teach Christians, that if the Pope knew the exactions of the preachers of indulgences, he would rather that the metropolitan church of St. Peter were burnt to ashes, than see it built up with the skin, the flesh and bones of his flock.

51. We must teach Christians, that the Pope, as in duty bound, would willingly give his own money, though it should be necessary to sell the metropolitan church of St. Peter for the purpose, to the poor people, whom the preachers of indulgences now rob of their last penny.

52. To hope to be saved by indulgences is to hope in lies and vanity; even although the commissioner of indulgences, nay, though even the Pope himself should pledge his own soul in attestation of their efficacy.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

German Protestantism gains rapid headway. Many German states sever

themselves from the Roman Catholic Church. In 1531, the Lutheran princes within

Charles' Empire establish a defensive alliance known as the Schmalkaldic League.

A threatened invasion by the Turks prevents Charles from taking immediate action

against these "heretic" Lutherans. By 1540, all North Germany is Lutheran.

Luther has demolished the old order. The religious unity of Europe is

destroyed! Nations begin to go their separate ways. The Reformation destroys the

meaning of the office of Holy Roman Emperor. The Emperor now becomes the head of

one party, the Catholics. Though the outward form of the Holy Roman Empire will

continue for some centuries, it is never the same again. The political as well

as the spiritual muscle of the Papacy is eroded. To counteract the Protestant

Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church organizes the "Counter-Reformation." The

Council of Trent (1545-63) decrees a thorough reform of the Church and clarifies

Catholic doctrine. These efforts eliminate many of the abuses that had triggered

the Protestant Reformation, and revitalize the Church in many parts of Europe.

But the Church has plummeted far from the zenith of its power, when

Papal authority was felt and feared in every country in Europe.

"The wars of religion and the collapse of church unity marked the end of theology as the

decisive force in Western civilization," a West German political figure, Franz

Josef Strauss, will observe centuries later.

Central Europe in 1547.

(click to enlarge) |

The Religious Situation in Europe about 1560.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In the meantime, a rather complicated situation has developed in the

political arena. Geopolitical events in the early 16th century revolve around

four powerful monarchs: Emperor Charles V., Francis I. of France, Henry VIII. of

England, and Suleiman of Turkey.

In the same year Charles was crowned at Aachen (1520), a new Turkish

sultan had ascended the throne in Constantinople — Suleiman, known to Turkish

history as "the Magnificent." The Ottoman Turks now control the eastern

Mediterranean and are viewed as a menace to Christian Europe. But the main foe

of the Habsburgs is France. France has emerged as a major continental power and

an aggressive antagonist of the German empire. Habsburg power all but surrounds

France. In response, Francis I. allies himself with the Islamic Turks and German

Protestants, despite the fact that he is a French Catholic king.

In England, Henry VIII. seeks to maintain the balance of power to

prevent the domination of Europe by either the Habsburgs or France. He shifts

his support from side to side as circumstances require, equalizing the power of

the continental rivals.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In 1525, a defensive alliance is created to check growing Habsburg

power. It is the Holy League of Cognac, made up of France, the Papal States,

Rome and Venice. England supports the new league. Early in 1527, mutinous troops

of Charles V. march against the Pope. They enter the defenseless city of Rome and

plunder it. This is the infamous sacco di Roma —

the Sack of Rome. The Pope, Clement VII., surrenders.

The Pope is ready for a compromise. He makes peace with Charles, and

meets with him in Bologna in February 1530. There, Pope Clement crowns Charles

Holy Roman Emperor. This is the last time that a

Holy Roman Emperor will be crowned by a Pope. Charles believes the

Emperor must be supreme if there is to be real peace. But the imperial title is

not what it used to be. The Empire has more shadow than substance. Charles'

globe-girdling Empire is united only in the sense that it has a common personal

ruler. The nation-state is on the rise, and the Empire is torn religiously.

Charles is opposed by princes whose own power is stronger when the Emperor is

weak.

The very extent of Charles' vast realm is in itself a drawback. There are

too many problems in too many places. The political situation is dire. In 1546,

open civil war erupts between the Schmalkaldic League and Catholic forces led by

Charles. The imperial armies score a victory over the League at Muhlberg in

April 1547. But a new war breaks out in 1551. It wears on for four years. In

September 1555, the Peace of Augsburg ends the hostilities. This compromise

officially sanctions the Lutheran faith in the Empire. Now, the two opposing

Christian religious communities can lawfully live together within the Holy Roman

Empire side by side. The princes of the territories of the Empire can choose

between Lutheranism or Catholicism, each prince's choice being made obligatory

for his subjects. Charles' dream of restoring religious unity throughout his

dominions has been thwarted. And by further entrenching the power of the

princes, the Augsburg settlement reinforces the decentralization of the Germanies.

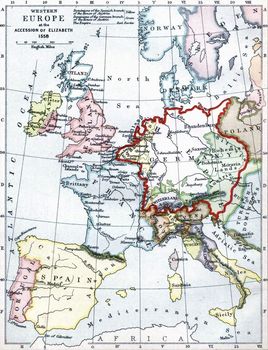

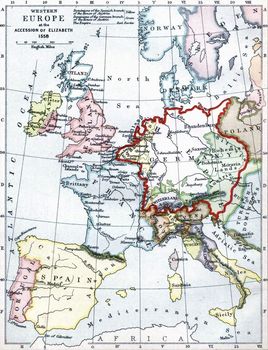

Western Europe at the Accession of Elizabeth 1558.

(click to enlarge) |

Western Europe in the Time of Elizabeth.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Disappointed in his ambitions and ill of health, Charles V. abdicates

and retires to a monastery in August 1556. He turns over the rule of Spain, the

Netherlands and Italian holdings to his son Philip II. To his brother Ferdinand

goes the imperial office and Habsburg lands in central Europe. After 35 years'

rule, Charles — the last universal Emperor of the West — steps aside. Historians

will consider him to have been the greatest monarch to bear the imperial crown

since Charlemagne. He dies September 21, 1558.

Charles V. was the last Emperor to actively attempt to realize the

medieval ideal of a unified Empire embracing the entire Christian world.

Inspired by the concept of a spiritually and politically united Christian realm,

he had fought vigorously for a united Church.

More than four centuries after the death of Charles, a 20th century

descendant Otto von Habsburg — will write a biography of his illustrious ancestor.

Dr. Habsburg will observe that

"he (Charles V.) was attempting not to conquer or

to dominate, but to establish the nations in a free community of equal partners.

His ultimate aim was to create an alliance of peoples who, while retaining their

own individual characteristics and laws, would be linked together by a united

Church and a common desire to defend the west."

Dr. Habsburg will also note:

"The ideas coming to the surface in this,

the second half of the twentieth century, are surprisingly allied to those

problems and concepts which preoccupied Charles. Together with ecumenicity (the

movement promoting Christian unity), European unity has become the major issue

of our time.... The notion of a united Europe is taking hold again. People are

once again beginning to appreciate that religion and politics are indeed

interdependent...."

In assessing the role of Charles V., Dr. Habsburg will observe:

"Thus Charles V., once regarded as the last fighter in a rearguard action, is suddenly

seen to have been a forerunner.... Our generation will find its historical

inspiration in the concepts last embodied in the person, mind and political

views of Charles V. .... Inasmuch as he represents an eternal ideal, the Emperor

(Charles V.), after more than five centuries, is still living among us — not only

as our European ancestor, but as a guide towards the centuries to come."

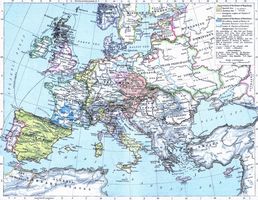

Diminions of the House of Habsburg

in Europe at the Abdication of Charles V.

(click to enlarge) |

Possessions of the House of Hapsburg,

including the Route of the Spanish Armada of 1588.

(click to enlarge) |

In the public interest.

Text by: Keith W. Stump