|

The History of Europe And the Church

The Relationship that Shaped the Western World

The historic relationship between Europe and the Church is a relationship that has shaped the history of the Western World.

Europe stands at a momentous crossroads. Events taking shape there will radically change the face of the continent and world.

To properly understand today's news and the events that lie ahead, a grasp of the sweep of European history is essential.

Only within an historical context can the events of our time be fully appreciated - which is why this

narrative series is written

in the historic present to give the reader a sense of being on the scene as momentous events unfold on the stage of history.

|

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

THE HABSBURG dream of a unified Empire

embracing the entire Christian world has been thwarted by the forces of

nationalism and religious enmity.

The Schmalkaldic Wars between the

Lutheran princes of the Holy Roman Empire and Catholic princes led by Emperor

Charles V. have ended in 1555 with the Peace of Augsburg. Now, both Roman

Catholics and Lutherans are officially recognized within the Empire.

But this compromise peace has many

shortcomings and satisfies no one completely. And it does not recognize

Calvanism, a faith that spreads rapidly in the latter half of the 16th century.

Political rivalries among the numerous

petty princes are sharpened by religious differences among them. In 1618 the

uncertain peace collapses and the most terrible of all religious conflicts

breaks out — the Thirty Years' War.

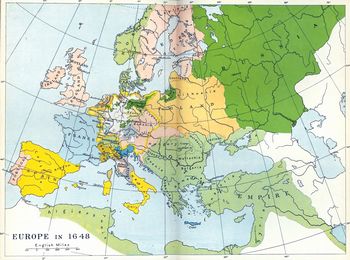

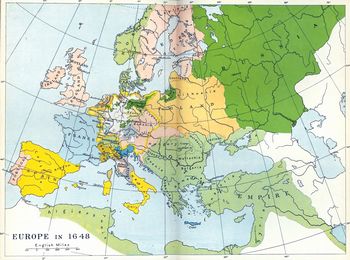

Europe in 1648, Peace of Westphalia.

(click to enlarge) |

Europe in 1648, after the Thirty Years' War.

(click to enlarge) |

The term Peace of Westphalia denotes a series of peace treaties signed in 1648. These treaties

ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) in the Holy Roman Empire, and the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) between

Spain and the Dutch Republic. The treaties did not restore the peace throughout Europe, however.

France and Spain remained at war for the next eleven years, making peace only in the Treaty of the Pyrenees of 1659.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

It begins as a conflagration between

Catholic and Protestant, but quickly grows into a life-and-death national

struggle between the French Bourbons and Austrian-Spanish Habsburgs for the

mastery of Europe!

Not since Attila the Hun has the

continent of Europe seen such butchery and destruction. In this war, all are

losers.

In 1648 the Peace of Westphalia ends the

war and restores a precarious peace to the Continent. But the German countryside

is ruined. It will take a century to recover.

The war has dealt a heavy blow to the

Holy Roman Empire. From now on, the Empire has no history of its own. It has

become a loose collection of separate rival states.

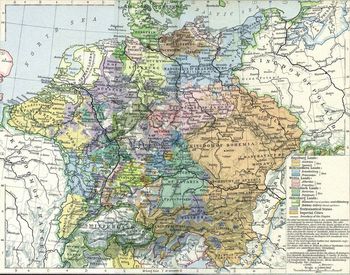

By the year 1700, Germany is a patchwork

of more than 1,700 independent and semi-independent princes and nobles. They are

vassals of the Habsburg Emperor in name only.

Without a united and subservient Empire,

the Emperor's position in Europe is very weak. Prospects for realizing the ideal

of a single European Empire — a unified Christendom — appear exceedingly dim.

The "Holy Roman Empire" has become but a

hollow name. The French philosopher Voltaire will shortly describe it as

"neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire." Yet the outward forms and titles of the Empire are continued.

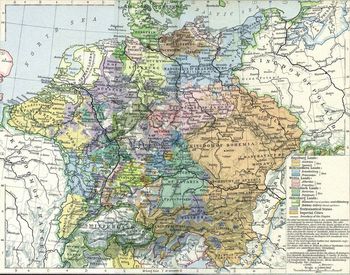

Central Europe About 1648.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Further threatening the existence of the

Holy Roman Empire is the rising power of France.

In 1661 young King Louis XIV. assumes

active personal control of the state affairs of France. Louis has a strong sense

of royal mission. He wants to become the foremost prince of Europe. He envisions

himself as the heir of Charlemagne and seeks to resurrect the Frankish Empire

under his leadership.

Ruling from his grand palace at

Versailles, Louis' royal control is absolute. "L'état c'est moi," he

declares — "I am the state!" He is popularly known as

"The Grand Monarch," and as

le Roi Soleil — "the Sun King."

Under Louis, France's influence in Europe

expands. The French army becomes the strongest in Europe. The French monarchy reaches its zenith.

Louis embarks on a long series of wars

aimed at maintaining France's domination of the Continent. This policy

ultimately leads to disaster. The greatest of these conflicts is the War of

Spanish Succession (1701-1714), in which Louis fights to secure the crown of Spain

for his grandson. It is the culmination of the rivalry between Bourbon and

Habsburg. French armies sustain a series of costly defeats. An impoverished

France is reduced to a second-rate European power — for a time.

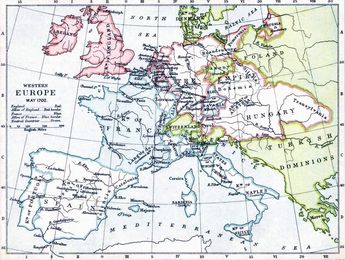

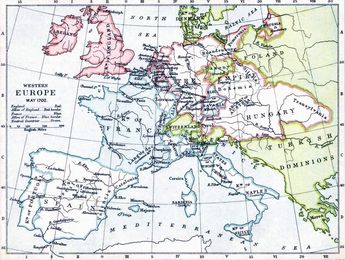

Europe in 1702.

(click to enlarge) |

Western Europe after the Treaties of Utrecht and Rastadt in 1713.

(click to enlarge) |

The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht registered the defeat of French ambitions

expressed in the wars of Louis XIV. and preserved the European system based on the balance of power.

The Treaty of Rastatt in 1714 ended hostilities between France and Austria at the end of the War of the

Spanish Succession. It complemented the Treaty of Utrecht, which had, the previous year,

ended hostilities with Britain and the Dutch Republic. A third treaty, the Treaty of Baden,

was required to end the hostilities between France and the Holy Roman Empire.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Meanwhile, another European power is on

the rise — the Protestant state of Brandenburg, soon to be known as

Brandenburg-Prussia, or simply Prussia.

Prussia is ruled by the Hohenzollerns, a

family of German counts. In May 1740 Frederick II. comes to the throne as king in

Prussia. History will know him as Frederick the Great.

Frederick believes that a third strong

political power must be established in Europe to offset the strength of France

and Austria. That power, he declares, must be Prussia.

Under Frederick, Prussia becomes a rival

to Austria for control of the German states. A non-Catholic, Frederick holds the

Catholic Habsburgs in low esteem and subjects them to public ridicule.

Frederick builds a strong government and

an efficient army. In short order, Prussia's military reputation becomes

unsurpassed in Europe.

The great war of his reign comes in 1756

. It is the Seven Years' War, pitting Frederick against the combined armies of

Austria, France, Russia, Sweden and Saxony. Frederick is vigorously attacked,

and his forces face annihilation. The very existence of Prussia is at stake !

In the end, the death of Elizabeth of

Russia and the exhaustion of France saves him. Alone, Austria and her allies are

unable to overcome Frederick. Austria has to accept the fact that Prussia is a

strong rival for leadership in Germany.

After another century passes, the

Prussian king will actually become emperor of a united Germany !

Europe in 1721.

(click to enlarge) |

Europe in 1740.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Back in France, the situation is dire.

Louis XIV. is dead. His weak great-grandson, Louis XV., devotes himself to the

pursuit of women. "Après moi le deluge," he declares —

"After me, the flood." And it is so.

The reign of his grandson, Louis XVI.,

begins in 1774. It is the prelude to revolution. The profligacy of the French

monarchy has nearly ruined the country. The lavish spending of the

court — epitomized by Louis XVI's unpopular and extravagant queen, Marie

Antoinette — earns it the contempt of the French people. The outmoded feudal

privileges of the nobility are widely resented.

Discontent is widespread. Taxation is

heavy. The misery of the common man reaches the breaking point.

Events now move swiftly.

On July 14, 1789, the population of Paris

takes matters into its own hands. A mob storms the Bastille prison, the hated

symbol of absolute monarchy and despotism. This event triggers the mighty

explosion that history will call the French Revolution. The insurrection spreads rapidly

throughout France. The crown and nobility come under siege. Peasants burn

chateaus and terrorize their noble landlords. A revolutionary government seizes

control of the state.

Louis XVI. and his queen are imprisoned.

They are later tried and guillotined. A bloody Reign of Terror grips the country, as nobles

and persons with real or suspected counterrevolutionary sympathies are condemned to the blade.

Europe in 1763 after the Treaty of Hubertsburg.

(click to enlarge) |

Central Europe about 1786.

(click to enlarge) |

The Treaty of Hubertusburg was signed in 1763 at Hubertusburg by Prussia, Austria, and Saxony.

Together with the Treaty of Paris (1763), it marked the end of the Seven Years' War and the French and Indian War.

The latter is the common U.S. name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763.

The name refers to the two main enemies of the British colonists: the royal French forces and the various

Native American forces allied with them.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Religion also comes under attack. The

Church in France is put under state control. Church lands and wealth are

confiscated, religious orders suppressed, and the clergy required to take oaths

of fidelity to the constitution.

The picture is little better elsewhere in

Europe.

For decades, the Papacy has been

virtually excluded from the political affairs of Europe. Under Pius VI., Pope

from 1775 to 1799, the Papacy reaches its nadir. It is all but stripped of power

and influence. In the Habsburg dominions, the Catholic Church is still

influential, but even there it is subordinate to the state.

French armies march on Rome and occupy

the city early in 1798. A republic is declared. Pius refuses to renounce his

temporal sovereignty, and is taken prisoner by the French in March 1799. He is

taken to France, where he dies at Valence in August.

It is a "Canossa in reverse." Church

influence has deteriorated considerably since the time when Pope Gregory VII.,

"master of Emperors," forced the capitulation of Henry IV. at Canossa, Italy, in 1077.

Europe in 1789.

(click to enlarge) |

Europe in 1792.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In Paris, radical political leaders vie

with one another for power. Corruption, incompetence, bloodshed and hysteria

are the order of the day.

Amid this domestic turmoil, a new star is

on the rise in the French firmament: Napoleon Bonaparte. In desperation, the

country turns to him for relief.

A new era is about to begin in France.

Napoleon's ascent to power has been

meteoric. By age 26 the Corsican-born military genius of Byzantine stock had

become commander of the French army in Italy.

In 1799 the young hero returns from an

expedition against the English in Egypt. He seizes power in a bold move, setting

up a new government of three members. Borrowing a title from ancient Rome, he

calls them consuls. He himself is First Consul — a virtual dictator at age 30 !

Like a Roman imperator, Napoleon

concentrates all powers of state in his own hands. He dreams of being another

Caesar. Classical imagery fills his mind. A bust of Julius Caesar adorns his study.

"I am of the race of the Caesars, and of

the best, of those who laid the foundations," Napoleon will observe.

The Corsican patriot Pasquale di Paoli

had been the first to recognize the Roman in Napoleon.

"There is nothing modern

about you, Napoleon," he had once observed.

"You come from the age of (the classical biographer) Plutarch !"

Napoleon dreams of a resurrected

Roman-European civilization dominated by France. He had grown up amid dreams of

the classical world. Now he means to make them reality !

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

One of Napoleon's first concerns is the Papacy.

"The influence of Rome is incalculable,"

he declares. "It was a serious error to break with this power."

Napoleon realizes that the Papacy cannot

be conquered by the sword. He must come to terms with it in order to make use of it.

In 1801 a concordat (an agreement for the

regulation of ecclesiastical matters) is concluded between France and the

Papacy. The Catholic Church again becomes the official church of France. The breach is healed.

The next year, Napoleon is appointed

"First Consul for Life." France puts herself fully in his hands. He is moving

relentlessly toward his ultimate goal. No hand can stay him.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In 1804 all veils are cast aside. It is the year of destiny.

In May the French Tribunate votes in

favor of declaring Napoleon Emperor. The Senate passes the measure soon

thereafter. A plebiscite is held throughout France. The vote is 3,572,329 in

favor, 2,569 against. Napoleon has become Emperor of the French, his realm an Empire.

The very Frenchmen who did away with monarchy 12 years earlier now reestablish it !

Napoleon summons Pope Pius VII. (1800-1823) to Paris

"to give the highest religious connotation to the

anointing and crowning of the first Emperor of the French."

The Pope crosses the Alps late in November.

The spectacular coronation ceremony is

held at the Cathedral of Notre Dame on December 2, 1804, a millennium after

Charlemagne was crowned by Leo III. in Rome.

Napoleon walks to the high altar leading

his wife, Josephine, by the hand. She is a beautiful Creole, born in Martinique

in the West Indies.

The Pope is waiting, surrounded by

cardinals. Napoleon approaches. All expect him to kneel before the Pontiff. But,

to the amazement of the congregation, Napoleon seizes the crown from the Pope's

hands, turns his back on the Pope and the altar and

crowns himself'! He then crowns

his kneeling wife as Empress.

Napoleon is officially Emperor of the

French at age 34! He has made it clear that religion must be in the hands of the

state.

The Pope had been informed of Napoleon's intentions shortly before the ceremony,

but had chosen to proceed anyway. He now anoints and blesses the imperial couple.

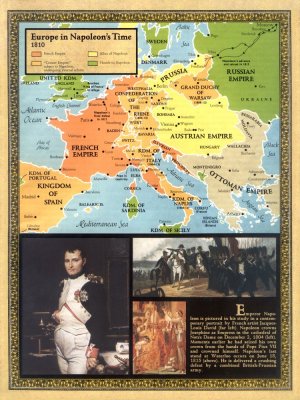

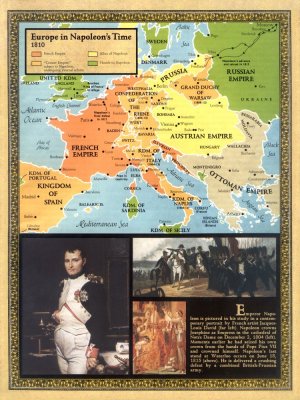

Europe in Napoleon's Time 1810

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

For years, Napoleon has seen himself as a

new Alexander the Great and a modern Roman Caesar. Now he begins to consider

himself more as the heir of the great Charlemagne. He goes to Aachen

(Aix-la-Chapelle) for a ceremonial visit to the tomb of the great Frankish Emperor.

"There will be no peace in Europe," he

says to his companions as he stands before the tomb, "until the whole Continent

is under one suzerain, an Emperor whose chief officers are kings, whose generals have become monarchs."

Napoleon has visions of conquest on a

grand scale. It will be he who will carry out the projects of Charlemagne, Otto

the Great and Charles V. in the modern world. "I did not succeed Louis XVI., but

Charlemagne," Napoleon declares.

In 1805 Napoleon makes himself king of Italy.

"When I see an empty throne," he confides, "I feel the urge to sit on it."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

On December 2, 1805, Napoleon engages the

combined armies of Russia and Austria at Austerlitz. Dawn begins with thick fog

and mist. The Russians and Austrians could wish for nothing better. Under its

cover, they hope, the Austro-Russian armies will be able to complete their

maneuvers without the French seeing what they are doing.

"But suddenly," as one

historian will describe it, "the sun with uncommon brightness came through the

mist, the sun of Austerlitz. It was in this blazing sun that Napoleon at once

sent a huge cavalry force under Marshal Soult into the gap left between the

center and the left of the Austro-Russian battlefield."

This is the break Napoleon needs. His victory is sealed. Many see it as the result of divine intervention.

France is now indisputably the leading

power on the Continent.

Austerlitz gives Napoleon increased confidence.

"Tell the Pope," he writes to Rome, "I am Charlemagne,

the Sword of the Church, his Emperor, and as such I expect to be treated !"

With renewed vigor, Napoleon pushes ahead

with his plans for a United States of Europe — a league of European states under

French hegemony. "I shall fuse all the nations into one," he declares.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In July 1806 Napoleon organizes the

Confederation of the Rhine (Rheinbund). It is a union of all the states of

Germany (except, of course, Austria and Prussia) under his protection.

With the advent of this French-controlled

federation, it becomes clear to all that the Austrian-led Holy Roman Empire is

dead. Napoleon has rearranged the map of Europe. He is supreme in Western

Europe, and is virtual dictator in the German states. He has usurped the Holy

Roman Emperor's primacy among Europe's monarchs.

In view of these facts, it is

preposterous for an Austrian archduke to bear the grandiose title of "Holy Roman

Emperor," pretending to be supreme over all Christendom.

On August 6, 1806, Holy Roman Emperor

Francis II. formally resigns his titles and divests himself of the imperial

crown. He is now simply "Emperor of Austria." Technically, Napoleon has swept

away the moribund Holy Roman Empire, the sacrum Romanum imperium.

But he perpetuates it, under a different name, for another eight years.

In October 1806 Napoleon defeats Prussia

in the battles of Jena and Auerstädt. No power can stand before him. He is the

unchallenged Emperor of the West !

In 1806 Napoleon crowns himself again,

this time with the celebrated "iron crown" of Lombardy. One of the great historic

symbols of Europe, this crown had previously been worn by Charlemagne, Otto the

Great and other European sovereigns.

Germany and Italy in 1803.

(click to enlarge) |

Germany and Italy in 1806 - Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Meanwhile, relations between Napoleon and

the Papacy deteriorate rapidly.

Pius VII. refuses to join Napoleon's

Continental System, the emperor's plan for shutting Great Britain out from all

connection with the continent of Europe. On February 2, 1808, French forces

occupy Rome. The Pope is arrested and detained. "The present Pope has too much

power," Napoleon writes his brother. "Priests are not made to rule."

In 1809 Napoleon decrees the Papal States

annexed as a part of the French Empire. Pius replies with a bull of

excommunication on June 10. Napoleon's reply ?

"In these enlightened days none

but children and nursemaids are afraid of curses," he laughs.

The Pope becomes Napoleon's prisoner, and is eventually transferred to Fontainebleau,

near the city of Paris. He does not return to the Vatican until May 1814.

Europe in 1811.

(click to enlarge) |

Europe in 1812.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In April 1810 Napoleon marries

Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria, having dissolved his childless marriage

with the empress Josephine. Marie-Louise is a Habsburg princess, the eldest

daughter of the last Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II. In March 1811 she bears

Napoleon a long-desired son, who is given the title "King of Rome."

Though elated at the birth of an heir,

Napoleon is growing restless. Western Europe is already beginning to seem too

small for him. He now plans what is to be the capstone of his career — the

incorporation of Russia into his Empire.

In June 1812 Napoleon and his 600,000-man

Grand Army cross the Niemen River and invade Russia. Following the Battle of

Borodino on September 7, the Russians retreat. The French reach Moscow on

September 14 only to find it burned by the Russians at the encouragement of the

British.

But Napoleon has overreached himself. In

trying to grasp too much, he loses all. The freezing Russian winter devours his

men by the multiple thousands. A disastrous retreat from Russia begins.

It is the beginning of the end. Napoleon

returns to France having lost more than 400,000 men! The handwriting is on the

wall.

In October 1813 Napoleon meets the allied

armies of Prussia, Russia and Austria at Leipzig in the "Battle of the Nations."

His army is torn to shreds.

The Allies close in on Paris. In March 1814 the

Treaty of Chaumont is signed by Russia, Prussia, Austria and Great Britain. It restores the Bourbon dynasty.

With everything crashing around him,

Napoleon finally abdicates in favor of his young son on April 6, 1814. The

Allies reject this solution. The Senate, too, does not recognize the child's

title, and calls the Bourbon Louis XVIII. to the throne instead. Napoleon then

abdicates unconditionally and is sent into exile on the island of Elba.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

With the fall of Napoleon in 1814, the

time-honored system of Roman-inspired government first resurrected by Justinian

in AD. 554 comes to an end after 1,260 years.

A year later, Napoleon escapes from his

island home. Recruiting an army, he marches on Paris. His brief return to power

is to last but 100 days.

On June 18, 1815, Napoleon meets a

combined British-Prussian army near the Belgian town of Waterloo. After a bitter

battle he is delivered a crushing defeat. As the French author Victor Hugo will

write: "It was time for this vast man to fall."

On July 15 Napoleon surrenders and, as a

prisoner, is sent to Saint Helena, a volcanic island in the South Atlantic

Ocean. The little Corsican who had conquered Europe becomes a caged eagle.

"What can I do on a little rock at the world's end?" he laments.

From the abyss of Saint Helena, Napoleon reminisces:

"I wanted to found a European system, a European

code of laws, a European judiciary. There would have been but one people throughout Europe."

Napoleon dies on May 5, 1821, on Saint

Helena, having been slowly poisoned by one of his disenchanted countrymen. His

dream of a unified Europe will have to be left to others. Even as Napoleon's

body is being interred in the island's rocky soill (later to be entombed in

Paris), the Continent is beginning to reform and reshape itself. The nations of

Europe are moving toward a new configuration — and an unexpected destiny.

Central Europe 1814-1815 - Treaty Adjustments.

(click to enlarge) |

Europe in 1815.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

THE NAPOLEONIC attempt to restore the

Roman Empire in the West is but a short-lived success.

Napoleon's final defeat at Waterloo in

1815 sends the one-time master of Europe into lonely exile on the rocky island

of St. Helena in the south Atlantic. And his dream of a unified Europe follows

him into the abyss.

Defeated France is reduced to her 1790

boundaries, assessed a large indemnity payment and forced to submit to an allied

army of occupation. The unpopular Bourbons are restored to the French throne

under Louis XVIII., brother of Louis XVI. He will reign as French king until his death in 1824.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

But the affairs of the rest of Europe

also have to be reordered.

To guard against the recurrence of war,

the Congress of Vienna convenes to redraw the map of Europe and bring stability

to the war-exhausted Continent.

Among the chief negotiators are Austria's

chancellor Prince Metternich, Britain's foreign minister Lord Castlereagh, Czar

Alexander I. of Russia, Prussia's King Frederick William III., France's

representative Talleyrand, and the Papal delegate Cardinal Consalvi.

The international assembly reorganizes

the political boundaries of Europe. One of the results of the Congress is the

establishment of the German Confederation (Deutscher

Bund) under the presidency of Austria. The defunct Holy Roman Empire

of the German Nation is no more.

Napoleon's reorganization of Germany

consolidated scores of smaller German states into larger entities. The new

German Confederation is an association of 39 sovereign German states. But it is

a feeble organization. Unity is still severely hampered by rivalries among

states. The loosely knit league will limp along until 1866.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Prince Metternich (1773-1859), the

Austrian chancellor, seeks to make Austria a leading European power and the

undisputed head of the German-speaking peoples. But his designs are opposed by a

formidable antagonist — Prussia.

Under Frederick the Great (king in

Prussia from 1740 to 1786), Prussia had become a rival to Austria for control of

the German states. This rivalry persists. Prussia still seeks to gain the upper

hand in German affairs.

In 1834, Prussia organizes a German

customs union, known as the Zollverein, under

Prussian leadership. It creates a free-trade area throughout much

of Germany, removing unnecessary restrictions from commerce. And, significantly,

it undermines Austria's dominant position in the region.

The Zollverein shows the Germans the

value of cooperation. It encourages the desire for unity. Historians will look

back on the customs union as a key first step on the road toward German

reunification.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Back in France, a revolution in July 1830

drives the Bourbons from the throne. The Bourbon monarch, Charles X. (1824-1830),

flees to England in exile.

The new king of the French is

Louis-Philippe, duke of Orleans. Though a relative of the exiled king,

Louis-Philippe has a reputation as a progressive. He reigns for nearly 18 years

as constitutional monarch.

In 1848, a revolutionary tide sweeps

across Europe. The colorless and increasingly unpopular Louis-Philippe is one of

its victims. Abdicating in February, he too flees to England.

On December 10, 1848, Louis Napoleon

Bonaparte (1808-1873), a nephew of the late Emperor Napoleon I., is elected

president of France's Second Republic. The republic, however, is short-lived.

In the last month of 1851, Louis Napoleon

Bonaparte stages a widely popular coup d'etat, establishing an authoritarian

government under his leadership. A vote is taken in favor of the restoration of

the Empire.

The Second Empire is formally inaugurated

on December 2, 1852, the day of Louis Napoleon's coronation. He styles himself

Napoleon III., Emperor of the French. (Napoleon II., the young son of Napoleon I.,

had died in 1832)

A major concern of his reign will be the

threatened emergence of a unified German nation. The stage is being set for a

titanic clash of ambitions that will rock Europe to its very foundations !

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Meanwhile, in Italy, a crucial series of

events is taking place.

The Congress of Vienna had again divided

Italy into numerous states. Most of the peninsula is now dominated by Austria.

Only the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont is free of Austrian influence.

In 1849, Victor Emmanuel II. comes to the

Sardinian throne. He is head of the House of Savoy. During the 18th century,

this dynasty had acquired the rulership of the island of Sardinia and

territories in northern Italy, centered on the region of Piedmont. The capital

of the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont is the city of Turin.

A growing movement is now under way for

Italian freedom and unification. It is called the

Risorgimento ("resurgence").

Victor Emmanuel is an ardent supporter of the cause of Italian independence.

In 1852, Count di Cavour (1810-1861)

becomes prime minister of Sardinia-Piedmont. He is a descendant of one of the

ancient noble families of Piedmont. Like his king, Cavour is devoted to the

cause of ejecting Austria from Italian affairs and bringing about the

unification of Italy under the House of Savoy.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In July 1858, Cavour meets with Napoleon

III., Emperor of the French. They agree to provoke Austria into war.

The war comes in 1859. The Franco-Italian

coalition succeeds in breaking the power of Austria in the Italian peninsula.

But at the last moment, Napoleon III. deserts the Italians and concludes a treaty

with the Austrians. He wants Italy liberated from Austria, but does not want the peninsula united under Savoy.

Despite this setback, the movement for Italian unification continues.

Another figure now enters the picture: Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882).

Years earlier, Garibaldi had joined Young

Italy, a movement for Italian liberty and unification organized by the

revolutionist Giuseppe Mazzini. Now Garibaldi decides that the best road to

unity lies in his working with Victor Emmanuel and Cavour.

In May 1860, with the support of

Cavour, Garibaldi leads a 1,000-man volunteer guerrilla army from Genoa in a

spectacular invasion of Sicily, then ruled by the king of Naples. This is the

famous Expedition of the Thousand. Garibaldi's men are clad in scarlet shirts,

and are popularly dubbed the Red Shirts.

Sicily is taken after threemonths of

fighting. Garibaldi then moves against Naples. That city falls on September 7,

1860. Sicily and Naples have been conquered! Garibaldi is a national hero.

Garibaldi hands his conquests over to Victor Emmanuel. Other Italian states

declare by plebiscite for union with Sardinia-Piedmont. On March 17, 1861,

Victor Emmanuel II. is proclaimed the first king of Italy. Most of Italy is

united under the House of Savoy! But the unification of the peninsula is by no means complete.

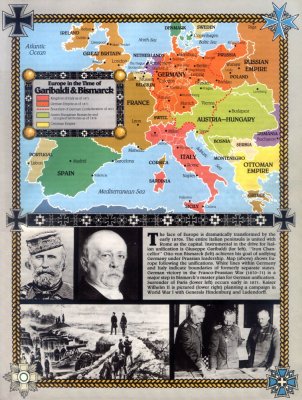

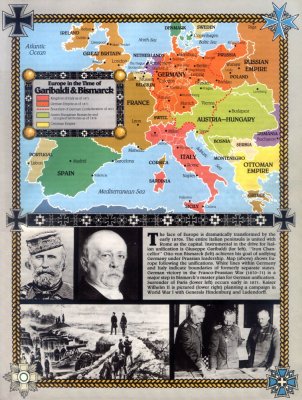

Europe in the Time of Garibaldi and Bismarck 1870's

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Not included in the new kingdom is the Papal possession of Rome.

Emperor Napoleon I. had taken the Papal

States — territory in central Italy ruled by the Papacy — from the Pope in 1809.

They were restored to the Pontiff by the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

Now, the Papal States (or States of the

Church) are seized by the armies of Victor Emmanuel and annexed to Italy. The

Church's temporal power is shattered! Only Rome — garrisoned by French

troops — remains under Papal sovereignty. France considers herself the protector

of the Papacy. Garibaldi still dreams of Rome as the capital of the new united

Italy. In 1862, he raises a force to capture Rome and annex it to the Italian

kingdom. But Victor Emmanuel, desirous of avoiding a conflict with France,

orders his own forces to stop Garibaldi. Four years later Garibaldi tries

again, but is defeated by Papal and French forces.

The time is not yet ripe for the conquest

of Rome.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Now the focus shifts to Germany

In Prussia, Otto von Bismarck becomes

prime minister and minister of foreign affairs in the autumn of 1862. He serves

under King William I. (Wilhelm), who acceded to the Prussian throne in 1861.

Bismarck was born in 1815, the year of

Napoleon's final defeat at Waterloo. He is a political genius, ultraconservative

in viewpoint. From 1859 to 1862, he served as Prussian ambassador to Russia.

Bismarck's chief ambition is to unify

Germany under Prussian leadership and exclude Austria from German politics.

During a short stay in London in the summer of 1862, he astonishes British

statesmen by bluntly declaring that when he becomes Prussian prime minister, his first move

"will be to reorganize the army with or without the help of the Diet.

As soon as the army shall have been brought into such a condition as to

inspire respect, I shall seize the first pretext to declare war on Austria,

dissolve the German Diet, subdue the minor states, and give national unity to

Germany under Prussian leadership."

Within nine years he will fulfill this program.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

At the very outset of his premiership,

Bismarck stuns the world by declaring to the Ways and Means Committee of the Prussian Diet:

"The great questions of our day cannot be solved by speeches and

majority votes, but by blood and iron."

He is thereafter popularly known as the Iron Chancellor.

Bismarck expands the Prussian military as

the long-standing hostility between Prussia and Austria nears the breaking

point.

In 1866, the question of the leadership

of Germany is finally fought out. In June, Bismarck picks a quarrel with Austria

over the possession of Schleswig-Holstein, a territory at the base of the

Jutland peninsula bordering Denmark. Thus begins the Seven Weeks' War, occupying the summer of 1866.

The Seven Weeks' War is a conflict

between opposing groups of German states, one led by Austria and the other by

Prussia. It culminates at the battle of Sadowa (Koniggrütz) an overwhelming Prussian victory.

Austria is now excluded from

participation in German affairs. Bismarck declares null and void the

Constitution of the German Confederation of 1815.

Europe in 1866 with the Peace of Prague.

(click to enlarge)

The Peace of Prague is a peace treaty signed in 1866 which ended the Austro-Prussian War.

The Habsburgs were permanently excluded from German affairs (Kleindeutschland). The Kingdom of Prussia thus

established itself as the only major power among the German states. The North German Confederation was formed,

with the north German states joining together, and the Southern German states having to pay large indemnities to Prussia.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In the wake of the Prussian victory over

Austria, the North German Confederation (Norddeutscher

Bund) is formed under Prussian hegemony in 1867. It is a union of the

German states north of the Main River.

Berlin becomes the capital of this new

Confederation. Bismarck writes a constitution making the Prussian king the

hereditary ruler and the Prussian prime minister its chancellor.

The four large southern German states of

Baden, Bavaria, Saxony and Wurttemberg remain independent and are permitted to

form a separate confederation. They enter into a military alliance with Prussia.

Austria's defeat in the Seven Weeks' War

leads Austrian Emperor Franz Josef and his government to establish a dual

monarchy embracing the Empire of Austria and the Kingdom of Hungary. It is officially known as

the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy (Oesterreich isch — Ungarische Monarchie).

The two halves of the

monarchy are independent of each other . The bond of union is the common dynasty

and a close political alliance. The crown is hereditary in the Habsburg-Lorraine

dynasty.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Bismarck's ultimate goal — that of uniting

all Germany under Prussian leadership — has still not been achieved. His next

move will be to bring the south German states into final union with the

Prussian-led North German Confederation. He will accomplish this by provoking a

war with France. After making sure that Russia will remain neutral in any

Franco-German conflict, Bismarck uses the candidacy of a Hohenzollern prince to

the throne of Spain to goad France into war.

Napoleon III. of France declares war on

Prussia on July 19, 1870 — just as the Iron Chancellor had hoped. The ambitions of

the two men have come to a clash. Thus begins the Franco-Prussian War.

As Bismarck had anticipated, the south

German states side with Prussia against France. Fighting side by side against

the armies of Napoleon III., Germans of the north and south develop a sense of

camaraderie and oneness — another step toward the unification of all Germany.

The German offensive is planned

brilliantly by General Helmuth von Moltke. On September 1, 1870 Prussia defeats

France at the battle of Sedan. Napoleon III. surrenders himself to the Prussians.

Paris itself is captured on January 28, 1871.

The German victory marks the end of

French hegemony in continental Europe. The war is concluded by the peace of Frankfurt on May 10, 1871.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Franco-Prussian War brings about a

strong feeling among German states for a closer union. The south German states

decide to unite with the North German Confederation.

On January 18, 1871, King William I. of

Prussia is proclaimed German Emperor (Deutscher Kaiser) in the Hall of Mirrors

at Versailles near Paris. North and South Germany are united into a single

Reich, or Empire. Bismarck has succeeded in consolidating Germany under the Prussian Hohenzollerns !

Bismarck assumes the office of Reich Chancellor and is made a prince.

This new German Empire is called the

Second Reich. (The First Reich had been inaugurated in AD. 962 with the crowning

of Otto the Great as Holy Roman Emperor by Pope John XII.) This Second Reich,

born in 1871, will live 47 years (until 1918). Germany has become the dominant force in European affairs !

Europe in 1871

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

With the French defeat in the

Franco-Prussian War, Napoleon III.'s troops in Rome return home. For years they

had maintained the temporal power of the Papacy over that city. Now Rome is virtually defenseless.

On September 20, 1870, the forces of

Victor Emmanuel II. enter Rome. The "Eternal City" is taken by Italian troops in

the name of the Kingdom of Italy. In October, Romans vote overwhelmingly to be a

come part of the Italian kingdom. Rome officially becomes the capital of a united Italy on July 2, 1871.

After 1500 years, Rome is again the capital of Italy !

But what of the Papacy ?

The Pope, Pius IX. (1846-1878), has been

stripped of temporal power by troops of the Kingdom of Italy. He excommunicates

the invaders, declares himself a prisoner in the Vatican and refuses to

recognize the new kingdom. His successors, too, will become voluntary prisoners

in their own palace. It will be six decades before a reconciliation is effected.

Though weak in the temporal sphere, the Papacy is asserting its strength in the spiritual realm.

Pope Pius had convoked the first Vatican

Council in 1869. The next year it declared Papal infallibility as a formal

article of Catholic belief. This dogma holds that when a Pope speaks officially

(ex cathedra) to the universal

Church on a doctrine of faith or morals, he cannot err.

This dogma had long been held in some

form, but in view of objections being made against it, the bishops in the

Vatican Council thought it expedient to make clear the stand of the Church.

Not all, however, are willing to submit to this newly defined and reasserted Papal authority.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The German Reich is ruled by a Protestant

dynasty, the Hohenzollerns. Bismarck seeks to strengthen the unity of the Reich

by limiting thepower of the Catholic Church within Germany. He accuses Catholic

elements within the Reich of political separatism, and labels them a threat to the unified German state.

Thus begins the so-called Kulturkampf (1871-1887), the

conflict between Prussia and the Church of Rome. It is a struggle between two

rival cultures and powers — the Catholic Church and the secular state. Bismarck's

objective is to wipe out the Vatican's political influence within the Reich.

"We are not going to Canossa, either

bodily or spiritually!" Bismarck declares, in an allusion to the capitulation of

Emperor Henry IV. to the Pope at Canossa in 1077.

A series of drastic laws are passed to intimidate the Catholic clergy.

"What is here at stake is a struggle for power,

a struggle as old as the human race, the struggle for power between monarchy and

priesthood. That is a struggle for power which has filled the whole of German

history," Bismarck declares.

Pope Pius dies in 1878 after a pontificate of 32 years — the longest in the history of the Popes.

But the Kulturkampf continues, though on a lesser scale, for an other nine ears.

A major reason for the Kulturkampf had

been Bismarck's desire to create some focus for national resentment. But with

the rise of socialism, Bismarck now sees the socialists filling that role even

better. He gradually begins to rescind his anti-Catholic measures.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Bismarck is also active in the

international political arena. On October 7, 1879, he concludes a military pact

with Austria-Hungary, allying the Habsburgs with Prussian-dominated Germany. The

alliance is designed to render France powerless against the Reich.

In 1882, Italy joins, forming the Triple

Alliance. It will remain in force until Italy's defection in 1915.

The ancient ties of Italy and Germany,

extending back to the days of Charlemagne and Otto the Great, are reforged. It

is the prelude to an era that will arise more than a half century later under

Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Emperor William I. dies March 9, 1888. His

son and successor, Frederick III., lives only a few months.

In June 1888, William II. becomes Emperor of Germany. The new Kaiser

is anxious to direct the government personally. He demands the Iron Chancellor's resignation.

After 38 years of service, Bismarck

steps down in March 1890. He retires to his castle, Friedrichsruh, near

Hamburg. The Kaiser then sets an aggressively independent course in foreign

affairs — a course that leads eventually to war.

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Françis

Ferdinand — heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary — is assassinated by a Serbian

in the Balkan town of Sarajevo. The great powers are caught in the webs of their

alliances. The bloody event triggers World War I.

When the guns finally fall silent on November 11, 1918,

a staggering 10 million lie dead. And the German Empire lies vanquished.

The abdication of the Kaiser is announced November 9. Defeated Germany is demilitarized and becomes a

republic. A new German constitution is adopted at the city of Weimar (Weimar Republic).

Many German war veterans are embittered

by defeat and the humiliations imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles. Among them is

a young Gefreiter (lance corporal) by the name of Adolf Hitler.

Europe in 1910.

(click to enlarge) |

Europe in 1911.

(click to enlarge) |

In the public interest.

Text by: Keith W. Stump