|

The History of Europe And the Church

The Relationship that Shaped the Western World

The historic relationship between Europe and the Church is a relationship that has shaped the history of the Western World.

Europe stands at a momentous crossroads. Events taking shape there will radically change the face of the continent and world.

To properly understand today's news and the events that lie ahead, a grasp of the sweep of European history is essential.

Only within an historical context can the events of our time be fully appreciated - which is why this

narrative series is written

in the historic present to give the reader a sense of being on the scene as momentous events unfold on the stage of history.

|

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The greatest power the world has ever known is trampled in the dust. The Empire that had conquered the world is herself conquered!

Italy is overrun by Germanic tribes. Odoacer, a chieftain of the Germanic Heruli, has deposed the boy-monarch Romulus Augustulus. The great city is without an emperor!

The long and

gradual collapse is now complete.

The ancient

world is at an end. The Middle Ages have begun.

The stage is now set for momentous events — events that

will determine the course of history for centuries to come.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In the East, the old Roman Empire still

lives, protected by the almost impregnable walls of Constantinople. There, Zeno

sits on the throne of the Eastern or Byzantine Empire. In theory, the German

Odoacer accepts the overlordship of Emperor Zeno. Zeno considers Italy one of

the administrative divisions of his empire.

In reality, Constantinople has little power west of the Adriatic. Odoacer

holds the administration of Italy firmly in his own hands. He is master of the

peninsula.

Odoacer perpetuates the Roman form of

government, which he admires. He initially encounters little serious opposition

from the people of Italy. But Odoacer is an Arian Christian; that is, a

Christian who follows the teachings of the scholar Anus. The Italians, by

contrast, are Catholics.

The same is true in North Africa. There,

the Germanic Vandals have held sway since AD. 429. The Vandals, too, continue

and maintain the Roman system of administration within their kingdom. The

Vandals are also Arian Christians. They persecute the Catholics within their

realm, often fiercely. The Roman Catholic Church bristles under the feet of the

Arian barbarians dominating the West. Since the days of Constantine, the Church

had had the wholehearted support of the civil power. Now things have changed

radically — for the worst. Something will have to be done about these hated Arian

heretics.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In AD. 476 — the same year Odoacer deposes

the last Roman emperor — a young noble named Theodoric becomes leader of the

Ostrogoths (East Goths). Theodoric quickly becomes the most powerful of the

barbarian kings in southeastern Europe.

Zeno, the Eastern emperor, fears the

ambitious Theodoric. To prevent the troublesome Ostrogoths from invading his

Eastern Empire, Zeno recognizes Theodoric as "king of Italy" in 488. Zeno hopes

to appease Theodoric, thereby ridding himself of the Ostrogothic menace.

Theodoric immediately leads 100,000

Ostrogoths into Italy to claim his kingdom from Odoacer. By the autumn of 490,

Theodoric has captured nearly the entire peninsula. But throughout Italy,

military garrisons still hold towns for Odoacer. These bastions must be eliminated!

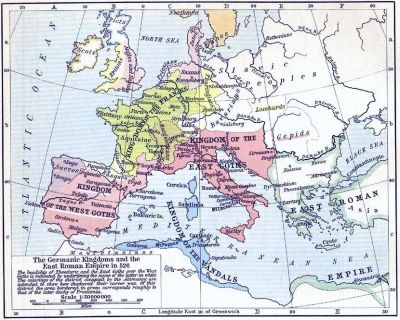

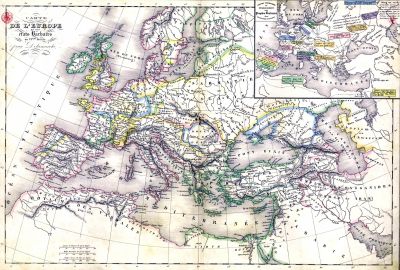

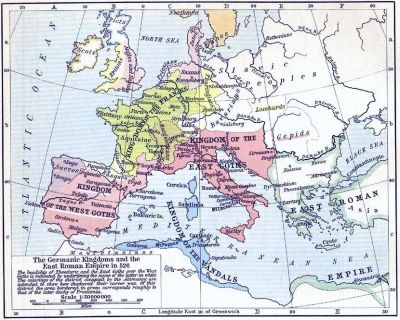

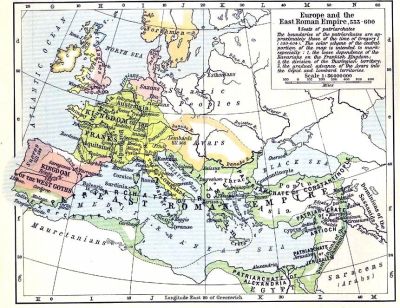

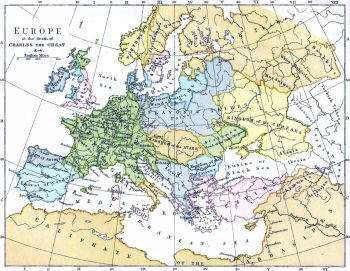

The Germanic Kingdoms and the East Roman Empire in 486.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Though Theodoric is himself attached to

the Arian creed, he is supported by the Catholic clergy in Italy. The clergymen

feel they will fare better under Theodoric than under Odoacer. Secret orders are

sent to the overwhelmingly Catholic citizenry throughout Italy. The Heruli and

other soldiers still loyal to Odoacer are to be dealt with once and for all!

The secret of the plot is well kept. It

is executed precisely on time. The Heruli are caught completely off guard.

Throughout Italy, Catholic civilians set upon the unsuspecting Heruli at a

predetermined hour. At ones stroke, the Italian citizenry accomplishes what the

Ostrogoths could not. This "sacrificial massacre" (as one contemporary describes

it) puts an end to Heruli as a military power once and for all.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Beaten in the field, Odoacer has taken

refuge behind the strong fortifications of Ravenna, north of Rome. There he is

besieged nearly three years. Early in 493, Odoacer finally surrenders. Theodoric

graciously offers to rule Italy jointly with him. A few days later on March 5,

493 Theodoric invites Odoacer to a banquet. Odoacer accepts — with disastrous

consequences. As Odoacer enters the banquet hall, two of Theodoric's men

suddenly grasp his arms. Others hidden in ambush rush forward with drawn swords.

Apparently they had not been told the identity of their intended victim, for

when they see Odoacer standing helpless before them they are panic-stricken !

The soldiers hesitate. Theodoric himself

rushes forward to do the job for them. With one powerful blow of his broadsword,

Theodoric splits Odoacer in two from his collarbone to his hip! With this piece

of treachery, Theodoric becomes the sole and undisputed master of Rome.

He establishes a strong Gothic kingdom in Italy. Theodoric, too, has great

respect for Roman civilization, and continues the traditional Roman system of

government.

But Theodoric and his heirs are Arians.

And for this reason, they, too, will have to be uprooted. Theodoric dies in

Ravenna on August 30, 526. He has no male issue, so his kingdom is divided among

his grandsons. Civil war soon breaks out in Italy — with dire consequences for the

Ostrogothic nation.

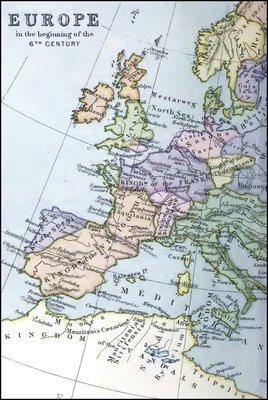

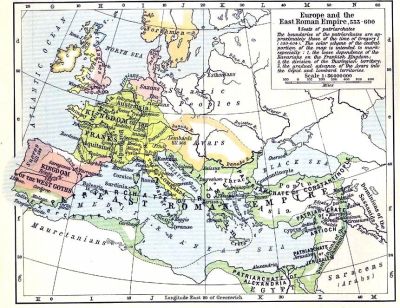

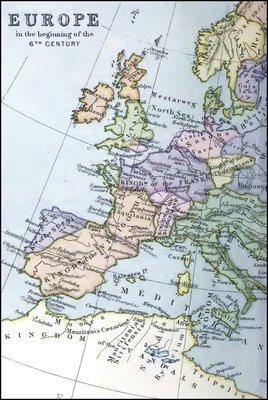

Europe in the Beginning of the 6

th Century.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Meanwhile, Constantinople is growing in

importance. As the western part of the Roman Empire had gradually succumbed to

the barbarians, the star of the eastern capital had steadily risen. Emperor

Constantine had begun building the magnificent new capital of the Roman Empire

in AD. 327. He had called it Nova Roma — "New Rome." It was founded on the site

of the ancient Greek city of Byzantium. Before Byzantium became New Rome, it had

occupied the favored location on the Bosporus for more than 1,000 years.

With the fall of Rome, Constantinople and

its emperors carry on the traditions of Roman civilization. Emperor Zeno who had

made Theodoric king of Italy — is followed as emperor by Anastasius (491-518).

Anastasius is succeeded by Justin (518-527). In August 527 — exactly a year after

Theodoric died heirless in Ravenna, a new emperor comes to the throne of the

Eastern Empire. The childless Justin is succeeded by his nephew and protégé

Justinian. He will rule for nearly four decades.

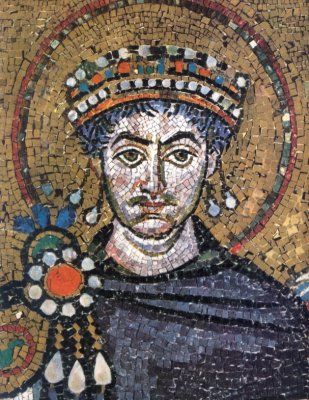

Justinian is 45 years old. He possesses

great intelligence and boundless energy. He is popularly called "the man who

never sleeps." Beside Justinian at the helm of state is his beautiful wife and

empress, Theodora. Justinian had married her four years earlier, in 523.

Theodora is lowborn. In her teens she had been the most salacious performer in the theatre,

a former actress and dancer. Her father had been a bear trainer at the Hippodrome circus.

Vicious rumor declares her to have once been the most licentious courtesan in the city.

Unscrupulous, she had the sleek ferocity of a panther. The truth of these charges will be debated for centuries.

Despite her past. Theodora becomes a queen in every sense of the word. Her

personal morals as empress will never be called into question. For 21 years,

until her death from cancer in 548. she will live with Justinian as his faithful

spouse and adviser. Theodora is brilliant, brave and wise. Had she been

otherwise, Justinian would not have held his throne. And his historic mission — a

mission of the highest significance to the course of history — would never have

been realized.

The Germanic Kingdoms and the East Roman Empire in 526

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Justinian's career is almost ended before

it begins. Constantinople is a sports-minded city. Its people are divided in

their allegiance to different charioteers. They are called the Greens and the

Blues, according to the color of dress of their favorite jockeys. In January

532, a disturbance breaks out between the two factions. The ringleader of each

party is punished. In response, the two rival factions unite in armed revolt

against the government. Open violence erupts as the government cracks down on

both factions. The city is filled with fire, bloodshed and murder. Thousands are

slain in the rioting. The crowd cries out "Nika!"

(Greek for "Conquer!").

History will thus record the event as the "Nika Riots."

Justinian's life stands in jeopardy. He

decides to abdicate, and prepares to abandon his capital by ship. But at the

last moment he is dissuaded by Empress Theodora. In a bold speech, Theodora

turns the tide of her husband's fear.

"I will remain, and like the great men of

old, regard my throne as a glorious tomb," she declares.

Her firm stand arouses new determination in Justinian. He decides to stand his ground.

Justinian dispatches Belisarius, his

trusted and brilliant general, to the Hippodrome with 3,000 veterans. The

riots are decisively suppressed. In one day, Belisarius slaughters 30,000!

Justinian's throne is saved. Had the Emperor been toppled, history might have

taken a much different course.

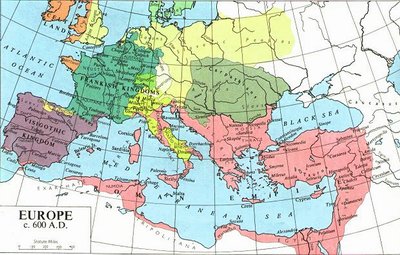

Europe in 526.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Justinian is now in a position to pursue

his one burning ambition: the recovery of the Western provinces that his

predecessors had lost to the barbarians. His dream is to restore the Roman

Empire to its full ancient grandeur — under his s own scepter! Justinian sees

himself a as rightful ruler of the whole Roe man world. But Justinian realizes

that there cannot be unity of empire without unity of religion.

Throughout the Empire — West and East

Christianity is established. But the form of Christianity is not the same

everywhere. Quarrels over basic articles of faith tear it at the unity of

Christendom. Justinian believes that a theological rapprochement will prepare

the way for the eventual political reunion of Byzantium and Italy. He views

political and ecclesiastical policy as inextricably linked. They are the two

major aspects of his envisioned Christian Empire. One of the most divisive

religious controversies centers around the old argument about the union of the

human and the divine in Jesus Christ. Some believe that Christ had only one

nature — a divine one or rather than a combined human and as divine nature, as

Catholics believe. They are called "Monophysites" — believers in one nature. The

West — led by the Pope in Rome — rejects the Monophysite doctrine, charging that it

over stresses the divine in Christ at the expense of the human. In AD. 451, the

Council of Chalcedon (held in what is now modern Turkey) condemns Monophysitism

as heresy, just as the Council of Nicaea had condemned Arianism in 325.

But Monophysitism persists. The Eastern

Church is torn between Catholic orthodoxy and the Monophysite doctrine. Zeno

and his successor Anastasius sympathize with the Monophysites, triggering a

schism between Constantinople and Rome. The Monophysites are powerful in the

Eastern provinces of Egypt and Syria. The Eastern emperors do not want to

endanger their control of these provinces by condemning the doctrine.

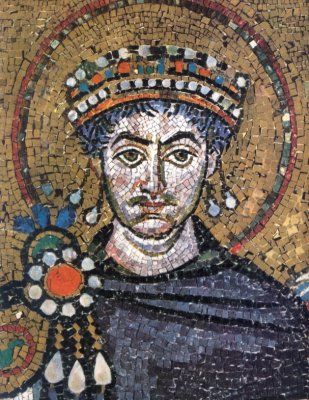

Mosaic of the imperial retinue in the choir, San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy.

Laid prior to A.D. 547, detail shows Emperor Justinian.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Upon the accession of Justin in 518, good

relations are renewed with the Papacy. Communion is reestablished with Rome. The

Eastern prelates sign a letter of reconciliation proclaiming the decision of

Chalcedon as binding on all Christians and stressing the primacy of the Roman

See as the final arbiter of what constitutes the faith.

The authority of Chalcedon is thus

renewed. The Eastern and Western churches are, for a time, reconciled, albeit

tenuously. But this does not end the problem. Monophysitism still thrives in

many areas. Personally, Justinian is a most zealous supporter of the Council of

Chalcedon and the cause of orthodoxy. But he would like to somehow unite the

die-hard Monophysites with the Church. He seeks to placate the Monophysites

without offending Rome a difficult task. He will have but slight success.

Justinian's efforts are hampered by the

sympathies of Empress Theodora. She leans toward the Monophysite position. In

536, Theodora intrigues with Vigilius, a Roman deacon. Succumbing to an impulse

of ambition, he agrees to modify Western intransigence toward the Monophysites

in exchange for her helping him become Pope. (the Romans had recently elected Pope Silverius (536-37),

a son of Pope Hormisdas(514-23); since Pope Agapetus (535-36) who had engaged in a violent quarrel

with the Empress had suddenly died, as opponents of the Empress frequently did.)

It is said he gives Theodora a secret guarantee that he will use his papal influence to abolish the Council of

Chalcedon. The next year, Vigilius is installed as Pope. But Theodora's hopes of

manipulating the Roman See are disappointed. Under many opposing pressures,

Vigilius vacillates and fails to offer clear concessions to the Monophysites.

For years the problem continues to plague the religious world. The situation

grows so acute that Justinian is finally prompted to convoke a general church

council. In May 553, the Second Council of Constantinople (the Fifth Ecumenical

Council) opens . It has been called in yet another attempt to reconcile the

Monophysites. The issues are complex. The Council finally settles on an

interpretation that is technically orthodox but leans a bit toward the

Monophysite position.

Few are satisfied with this compromise

formula. To the Monophysites, the new interpretation is just as unacceptable as

the old. Pope Vigilius initially refuses to accept the decrees of the Council.

But under pressure he later signs a formal statement (February 554) giving

pontifical approbation to the Council's verdict. In return, Justinian grants

Vigilius an imperial document known as the Pragmatic Sanction and permits him to

return from Constantinople to Rome. Vigilius dies on the way back. A new Pope,

Pelagius, is eleeted — with Justinian's insistence.

Justinian's Pragmatic Sanction confirms

and increases the Papacy's temporal power, and gives guidelines for regulating

civil and ecclesiastical affairs in Rome and Italy. It is issued on August 13,

554. The year 554 will become a decisive date in history for yet another

reason — the result of events in the military arena.

For the moment, the Papacy is under the

Eastern Emperor's thumb. But it is not destined to remain so. Ultimately,

Justinian's efforts in the religious sphere prove fruitless. At his death, the

Empire will still be badly divided in its religious belief. The unhealed wounds

of reigious strife between the churches of East and West will continue to

fester — coming to a head, as we shall see, in the Great Schism of 1054.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

While the aforementioned ecclesiastical

maneuverings are underway, events are moving swiftly ahead in the political

sphere. The persecuted Catholics in North Africa appeal to Justinian to send

troops against their Arian andal oppressors. This sparks the short-lived

Vandalic Wars. Justinian sends Belisarius — the greatest general of his age to do

the job. In 533-34, imperial armies move against the Vandals. Belisarius makes

short work of the barbarians. He receives the submission of the Vandal king

Gelimer, and North Africa is reincorporated into the Empire.

Phase Two of Justinian's Grand Design

follows immediately: the military re-conquest of Italy, the heart and mother

province of the Western Empire. The Ostrogoths have played into Justinian's

hands. In his latter years, Theodoric had begun to persecute the Catholic

Italians. Following his death, Ostrogothic cruelty toward non-Arians

intensifies. Italians look for a deliverer to uproot Arianism.

Justinian now has an excuse for invading

Italy. He sees himself as God's agent in destroying the barbarian heretics and

winning back the lost provinces of the West. If he succeeds in toppling the

barbarian usurper from the Western throne, his dream of restoring the Roman

Empire will become reality!

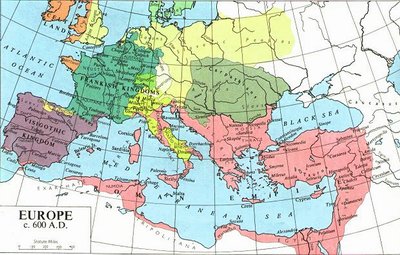

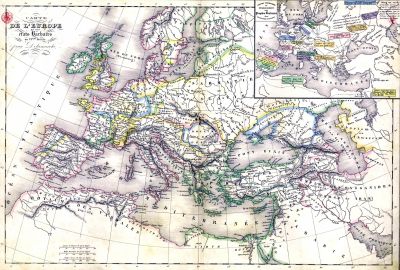

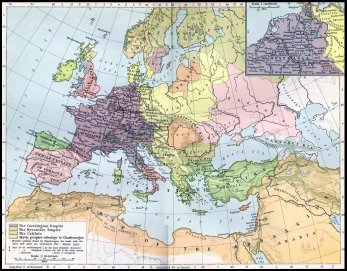

Europe and the Barbarian States in the 6

th Century.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In 535, Belisarius fresh from victory in North Africa — arrives in Italy to take on the Ostrogoths. Italy is plunged into war.

The fighting will continue for nearly two decades. In 540, Belisarius captures

Ravenna and announces the end of the war. But the Goths soon regroup under a new

king, Totila, and again take the offensive. City after city falls to Totila,

including Rome in 546. (Totila holds the last chariot races in Rome's Circus

Maximus in 549.) In 549, Belisarius is recalled to Constantinople. In 552,

Justinian sends a strong force against Totila under the command of General

Narses. Totila is defeated and mortally wounded in the summer of 552. His body

is placed at the feet of Justinian in Constantinople.

By 554, the Gothic hold is completely

broken. The reconquest of the peninsula is complete.

Italy is regained! Italy is now firmly in

Justinian 's hands. His Pragmatic Sanction of 554 (mentioned previously)

officially restores the Italian lands taken by the Ostrogoths. Italy is again an

integral part of the Empire. Three barbarian Arian kingdoms have been uprooted

and swept away! The deadly wound of AD. 476 is healed! The ancient Roman Empire

is revived — restored under the scepter

of Justinian. Both "legs" of the Empire — East and West — are now under his personal

control. History will memorialize his great achievement as

the "Imperial Restoration." It is a milestone in the story of mankind.

Europe and the East Roman Empire 533-600.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Many territories have been regained.

During his reign, Justinian has doubled the Empire's extent!

The great Emperor dies on November 14, 565. He has lived 83

years and reigned 38. At his death, his restoration is ready to crumble. The

resources of the Empire are not sufficient to maintain those territories that

have been recovered. The treasury is empty. The army is scattered and ill paid.

Within a century after his death, the Empire will have lost more territory than

Justinian had gained! Just three years after his death, the Longobardi, or

Lombards — a Germanic tribe — invade and conquer half of Italy. Again the Eastem

Empire is deprived of the greater portion of the Italian peninsula. The

continuing threat of the Empire's traditional enemy to the east, Persia — further

saps Byzantium's strength. And soon, the forces unleashed by Mohammed in Arabia

will introduce yet another peril. In the meantime, the Roman court of the East

will lose much of its Western character.

For these and other reasons,

the focus of events will now shift to the West. As the

Eastern Empire founders, Papal Rome will turn its eyes toward Western Europe,

where the powerful Frankish kingdom is on the rise. Subsequent revivals of the

ancient Roman Empire will surface in France, Germany and Austria. The center

will shift away from the Mediterranean to the heart of Europe. But Justinian's

efforts are not to be slighted. His reign has signaled a rebirth of imperial

greatness. He has been a true Roman emperor, an heir of the Roman Caesars! Much

of what will be envisioned and accomplished by later conquerors who build upon

the ruins of the Roman Empire will be owed to the memory of the Grand Design of Justinian.

The historical consequences will be major.

Europe around 600.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

JUSTINIAN'S RESTORATION OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE IN THE WEST IN A.D. 554 is a landmark in history.

For a brief moment, both "legs" of the old Roman Empire

East and West are under his personal control. But Justinian's history-making

restoration barely survives him.

With the great Emperor's death, the Eastern Empire, with its capital at

Byzantium, falls into a period of weakness and decline. At home, civil and

religious strife tear at the fabric of society. To the east, the Persians renew

their wars. To the west, the Germanic Lombards invade and conquer much of Italy.

Justinian's "Imperial Restoration" crumbles into the dustbin of

history. Though dying of lethargy, the Eastern Roman Empire, long since known as

Byzantium, continues to be recognized as the eastern successor of the old Roman

Empire . This weakened eastern leg will stand precariously for another

millennium.

Meanwhile, papal Rome turns its eyes toward Western Europe. There, a

powerful kingdom to the northwest is on the rise — the kingdom of the Franks. The

Franks earlier had settled along the Rhine after migrating up the Danube River.

It will be under Frankish tutelage that the western leg of the Roman Empire will

rediscover its vitality and strength.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Frankish tribes are ruled by a royal family of kings known as the

Merovingians. The Merovingians claim direct descent from the royal house of

ancient Troy. The Merovingian rulers possess an unusual mark of authority. All

the kings of this dynasty wear long hair.

They believe that their uncut locks are the secret of their kingly power,

reminiscent of the nazarite vow of Samson in the Old Testament (Judges 13:5;

16:17; see also Numbers 6:5).

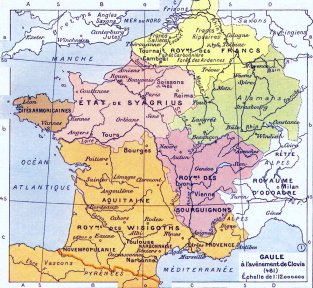

The Merovingian dynasty had been founded by Clodion in AD. 427. But its

most famous ruler is Clovis (481-511). Later historians will consider Clovis to

have been the founder of the Frankish kingdom.

On December 25, 496, Clovis is baptized a Catholic, along with 3,000 of

his own warriors. He thereby becomes the first Catholic king of the Franks and the only

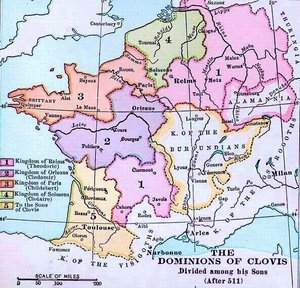

orthodox Christian ruler in the West. Upon Clovis' death in 511, his kingdom is divided among his

sons, who further enlarge its borders. The Frankish kingdom rapidly becomes the

West's most powerful realm. With the passage of time, however, the old line of

Frankish kings grows weak. The decadent Merovingian kings succumb to luxurious

living. They will be designated by French historians as "les rois

fainéants" — "the enfeebled kings." During this period, the

real power of the Frankish kingdom lies in the hands of the court chancellors,

who are known as major domus regiae,

or "mayors of the palace."

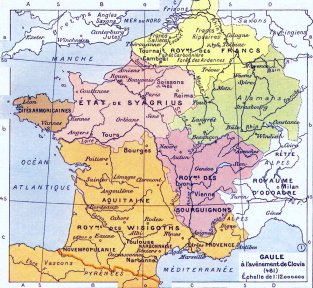

Gaule at the Beginning of the Rule of Clovis 481.

(click to enlarge) |

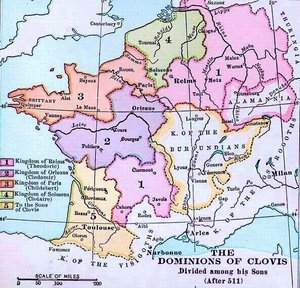

The Dominions of Clovis Divided Among his Sons after 511.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

It is now 751. Pepin (or Pippin), surnamed

Le Bref ("the Short"), holds the

office of mayor of the palace under the Merovingian king. Pepin, of course, is

also a German Frank by blood and speech. Pepin the Short is ambitious. He is

not content to be merely the king's chief minister or viceroy. He covets the

office of king itself.

Pepin asks Pope Zacharias for an opinion on the legitimacy of his bid.

The Pope replies that

"it is better that the man who has the real power should

have the title of king instead of the man who has the mere title but no power."

In November 751, Archbishop Boniface, the papal legate, anoints Pepin king of

the Franks at a gathering of Frankish nobles in the Merovingian capital at

Soissons. Pepin is now "God's anointed" and the Merovingian king Childeric III

is deposed and imprisoned. His sacred flowing hair is ritually shorn by the

command of Pope Stephen II (752-757). The power of the Merovingians is broken!

Childeric is sent to a monastery for the rest of his days. The

Merovingian bloodline, however, will survive, through intermarriage, in the line

of the dukes of Hapsburg-Lorraine. The Merovingians have reigned by right of

conquest. But Pepin has now assumed the sovereignty

in the name of God. He believes it is God's will that his family rule

the Franks. Pepin accordingly styles himself

rex gratia Dei ("king by the grace of God"), a title retained by his

successors. Pepin's new dynasty will be known as the Carolingians. The name

derives from Pepin's father, Charles (Carolus) Martel, who had been mayor of the

palace before him. It had been Charles Martel ("the Hammer") who saved Europe

from the invading Saracens (Muslim Umayyads) at Tours, in France, in October 732. By that

momentous victory, the Franks had become widely recognized as the real defenders

of Christendom. The Papacy had long since realized that Byzantium could defend

no one.

Gaule at the Beginning of the Rule of Charles Martel 714.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Church now looks to the Carolingians for protection against the

Germanic Lombards, who are occupying much of Italy — and want the rest! The

situation becomes desperate. As the Lombards threaten Rome, Pope Stephen II sets

out across the stormy Alps in November 753. His goal is Pepin's winter camp. The

Pope asks Pepin to come to his aid. The Church must be protected from the

encroachment of the Lombards!

At the same time, Pope Stephen 7 personally anoints and crowns Pepin,

and blesses Pepin's sons and heirs. The Franks answer the call Pepin invades

Italy and defeats the Lombards. He then confers the conquered Lombard territory

upon the Pope (754). This gift of rescued lands is called the "Donation of

Pepin." It cements the alliance between the Carolingians and the Church.

(The Donation of Pepin is not to be confused with the fictitious "Donation of

Constantine", a forgery also dating from about this time. This document — whose

falsity would not be proved for another 700 years — ostensibly came from the pen

of the Emperor Constantine himself early in the fourth century, when he moved to

the new capital of Constantinople. The document purports to be an offer from

Constantine to Pope Sylvester I and his successors of temporal rulership over

Rome, over Italy and over most territories of the Western world! Believed to be

genuine, the parchment carries vast implications and bolsters significantly the

prestige and authority of the Papacy.)

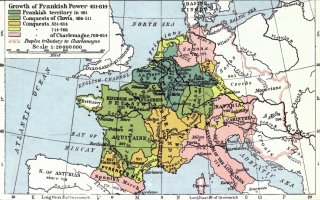

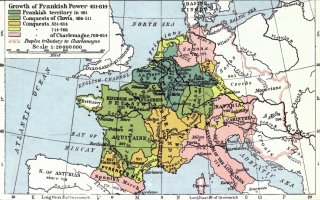

Growth of Frankish Power from 481 to 814.

(click to enlarge) |

The Frankish Expansion from 481 to 870.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Pepin dies in 768. His sons Charles (Karl) and Carloman jointly succeed

to the Frankish throne. In 771, Carloman dies suddenly, and Charles becomes sole

king of the Franks. Though only 29 years old Charles is an imposing figure He

most literally exudes power and authority! Charles is

7 feet tall — well over a foot

above average height and robust. He is stately and dignified in bearing, but is

known for his warmheartedness and charity. He speaks a type of Old High German.

But most important, he is a zealous and dedicated Catholic Christian!

Now in undisputed possession of the Frankish throne Charles directs

his efforts against the enemies of his kingdom. His great goal is to reestablish

the political unity that had existed in Europe before the invasions of the fifth

century.

He first launches a campaign against the fierce Saxons, who are

threatening his frontiers . The Saxons are the last great pagan German nation.

During the next three decades, Charles will wage 18 campaigns in his costly and

bitter struggle against the stubborn Saxons. In 804 they will finally be

Christianized at the point of the sword and incorporated into his empire.

Charles also undertakes campaigns against the Bavarians, Avars, Slays, Bretons,

Arabs and 35 numerous other peoples. During his long career, he will conduct 53

expeditions and war against 12 different nations! And in the process he will

unite by conquest nearly all the lands of Western Europe into one political

unit.

Emperor Charlemagne as portrayed in a 14th-century reliquary

(a container for religious objects) found today in the Cathedral Treasure at Aachen.

Charlemagne revived the tradition of the Roman Caesars and restored the Roman Empire in Western Europe.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Pepin had delivered a crushing defeat to the Lombards, but he had not

totally subdued them. The Church is now threatened once more. Rome needs a

champion! In 772, Charles receives an urgent plea for aid from Pope Adrian I,

whose territories have been invaded by Desiderius, king of the Lombards. So,

Charles crosses the Alps from Geneva with two armies. In 774 he decisively

overthrows the kingdom of the Lombards, deposes Desiderius and proclaims himself

sovereign of the Lombards.

Charles is now master of Italy! Charles takes the title

Rex Francorum et Longobardorum atque Patricius Romanorum ("King of

the Franks and Lombards and Patrician of the Romans"). The famous "iron crown" of

the Lombards which will become one of the great historic symbols of Europe is

placed upon Charles' head. It will be used in subsequent centuries by Frederick Barbarossa, Conrad II,

Charles V, Napoleon and other sovereigns of Europe.

Charles confirms and expands the Donation made to the Papacy by his

father. This territory will later be known as the States of the Church. Italy is

again united for the first time in centuries. Charles is heralded as defender of

the Church and the guardian of the Christian faith. The Frankish monarchy and

the Papacy stand in partnership against the enemies of civilization! Charles is

now the most conspicuous ruler in Europe. History will know him as

Charlemagne — "Charles the Great."

Charles came,

as he shows in his letters, to despise the Pope and to defy him on a

point of doctrine; for at that time the use and veneration of statues in

the churches was made a doctrinal issue between East and West. “The veneration of images”

was the greatest issue in the Church, Charlemagne put his own name

to a book in which Roman practice and theory were denounced as sinful,

the whole Galliclan Church was got to support him, and the timid

protests of the Pope were contemptuously ignored.

The Iron Crown with which Lombard rulers were crowned,

contains an iron ring within, allegedly made from a nail of Christ's cross.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

It is 795. There is a new Pope — Leo III. — in Rome. He immediately

recognizes Charles as patricius of

the Romans. By now, Western Christendom fully recognizes the bishop of Rome as

its head. But there are elements within the city of Rome itself that wish to see

Leo deposed and another candidate crowned as Pope in his stead.

In the spring of 799, Pope Leo is accused of misconduct. Adultery,

perjury and simony are among the charges. He is driven out of Rome by an

insurrection, and is granted refuge at the court of Charlemagne, protector of

the Holy See. Charlemagne reserves judgment, and has Leo escorted back to

Rome. In November 800, Charlemagne himself comes to Rome to investigate the

charges. A bishop's commission of inquiry into Leo's conduct is set up.

Charlemagne presides over the tribunal.

Pope Leo swears on the Gospels that he is innocent of the crimes

alleged against him. The judgment of the tribunal is in his favor. Leo is

formally cleared and reinstated on December 23. On the same day, emissaries from

Harun al-Rashid, caliph of Baghdad, arrive in Rome with the keys to the Holy

Sepulchre in Jerusalem. (Jerusalem lies within the extensive domains of the

caliph.) The keys are officially presented to Charlemagne. This act symbolizes

the Moslem caliph's recognition of Charlemagne as protector of Christians and

Christian properties.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

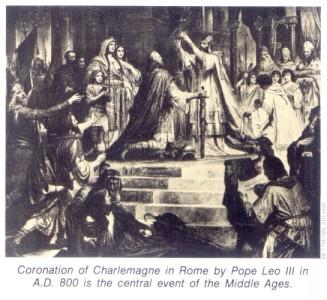

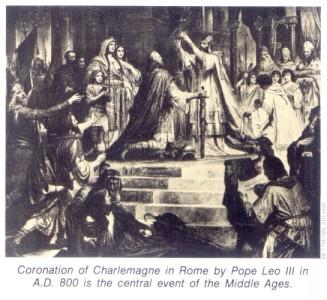

Charlemagne remains in Rome for the Christmas holidays. On Christmas

Day, A.D. 800, the king of the Franks attends a service in St. Peter's Basilica

on Vatican Hill. The stage is now set for one of the great scenes

of all history. Charlemagne kneels before the altar in

worship. There is a dramatic hush in the church. As the great king rises, Pope

Leo without warning, suddenly turns around and places a golden crown on the

monarch's head! Immediately the assembled people cry in unison:

"Long life and victory to Charles Augustus, crowned by God, great and peace-giving Emperor of the Romans!"

The Pope has crowned Charlemagne as imperator Romanorum — "Emperor

of the Romans"! Something profound has occurred. The West once more has an emperor!

Historians will look back on this as the central event of the entire Middle

Ages.

Coronation of Charlemagne in Rome by Pope Leo III in A.D. 800.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The coronation of Charlemagne marks the restoration of the Western

Roman Empire — the first revival of Roman Europe since Justinian. Charlemagne is

now officially a successor of the Roman emperors. The tradition of the Roman

Caesars is revived. In Charlemagne, Western Europe now has a Christian Caesar — a

Roman emperor born of German race! The

act also demonstrates that the memory of the once-great Roman Empire still

lives as a vital tradition in the hearts of Europeans. Historians will view

Charlemagne' s coronation as the beginning of what will be known as the Holy

Roman Empire. The political foundation of the Middle Ages has been laid !

Charlemagne is ruler of nearly all the territories that had once

constituted the Western Roman Empire. He has more than

doubled the territory he had inherited from his father and brother. All

France, nearly all of Germany and Austria, and all of Italy except the kingdom

of Naples are his! Under Charlemagne's scepter Western Europe for the first time

in centuries has something approaching unity. A new Roman Empire — a new

Europe — has been born !

In 803, Charlemagne will stamp on his seal the words

Renovatio Romani Imperii — "Renewal

of the Roman Empire."

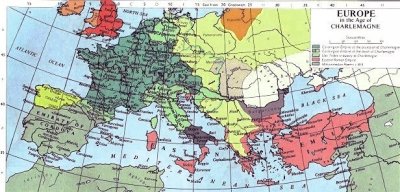

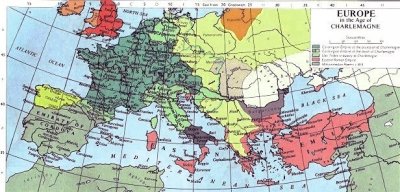

Europe in the Age of Charlemagne A.D. 800.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

There is yet another significance to the events of December 25, A.D.

800. Charlemagne has received the imperial crown

at the hands of the Pope! The populace see it as having come from

God. The message is clear to all: The imperial crown is a

papal gift. The kingdoms of this

earth belong to the bishop of Rome; they are his to give and to take away!

This assertion will often be challenged in following centuries, and

will have tragic consequences when kings and Popes wage war against each other.

But it leaves an indelible impression on the minds of Europeans. Charlemagne has

been taken unawares. He is reported to have grumbled that he would not have gone

to church on that day if he had known the Pope's intentions.

The Emperor is not unhappy about being emperor. His misgivings are over

the manner of the coronation. He has

won his empire on the battlefield through military genius; he does not

owe it to a Pope. Yet Leo has made it appear so. Whatever his doubts,

Charlemagne makes no protest. He quietly accepts the imperial crown from Leo.

The Pope has cleverly executed a "coup." In the eyes of all, the

Papacy has been symbolically exalted above the authority of the secular power. A

great legal precedent has been set. Charlemagne holds no grudge. Pope and

Emperor have too many interests in common to permit ill-feeling to exist. There

has been a "marriage" formally linking the spiritual power of the Pope with the

temporal power of the Emperor. The two are joint sovereigns on earth.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

As head of the recreated empire of the West, Charlemagne presides over

a new society born of the union of Roman and German elements. Charlemagne is a

German, but he is inspired with the spirit of Rome.

The Emperor organizes his empire on the pattern of the old Roman model.

He prizes the traditions of ancient Roman civilization. His Romano-Germanic

society will set a precedent for future European monarchs.

Charlemagne's capital is the German city of Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle).

Following his coronation, the Emperor spends the remaining years of his reign

there in comparative quiet. He becomes a patron of learning and the arts,

importing scholars from throughout Europe to study and teach at his court.

In 812 — two years before his death — Charlemagne receives news from the

East. Eastern Emperor Michael I. at Constantinople has swallowed his pride and

recognized Charlemagne as co-emperor. The equality of the two halves of the

Empire is now official. For all intents and purposes, however, the two "legs" of

the Empire are completely autonomous. A plan had been conceived shortly after

Charlemagne's coronation to combine his empire with the Byzantine empire through

his marriage to the Eastern Empress Irene (780-802). But the plan failed when

she was overthrown.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

During the last four years of his life, Charlemagne is subject to

frequent fevers. On the 28th day of January, in the year 814, the great Emperor

dies at nine o'clock in the morning. His death occurs in the 72nd year of his

life, and the 47th of his reign. The Emperor is buried in the church

he built at Aachen, sitting upright with sword in hand. His mammoth achievements

will be lauded in popular legend and poetry for centuries to come. Charlemagne

has not ended an age; he has begun one. He will be called

rex pater Europae — "King father of Europe." He has shown all Europeans

an ideal. He has bequeathed to them a common cultural and political tradition .

Even in the distant 20th century, men will point to his model as a blueprint for

European unity. Charlemagne has left his mark

on European history as no other man. He has, in large measure,

determined the political fate of Western Europe.

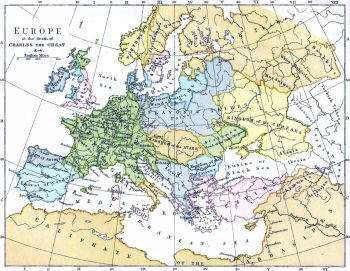

Europe at the Death of Charlemagne in 814.

(click to enlarge) |

The Carolingian and Byzantine Empires in 814.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Justinian's "Imperial Restoration" in

AD. 554 fell apart almost immediately upon his death. Charlemagne's empire survives him by only one

generation. This very cyclical pattern of revival and disintegration will be

often repeated in centuries to come.

Charlemagne is succeeded by his son Louis the Pious. The well-meaning

but weak Louis is dominated by his wife and by churchmen. He possesses no

qualifications for governing the empire to which he succeeds. Louis dies in 840.

Civil war then breaks out among his three sons. In 843, the

Treaty of Verdun

temporarily settles the quarrels among Louis' sons. It divides Charlemagne's empire into

three parts — one for each of his grandsons. In 870 the

Treaty of Mersen

realigns the borders again.

In short order, however, Europe crumbles into scattered feudal states. The Carolingian Empire disappears. The

political unity of Christian Europe becomes a thing of the past.

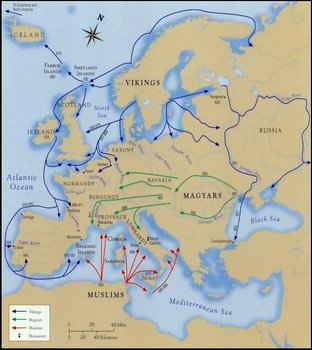

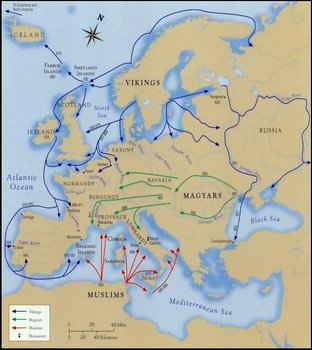

In its weakness, Western Europe falls victim to invasions by Northmen,

Saracens and Magyars. The Continent is again a political shambles.

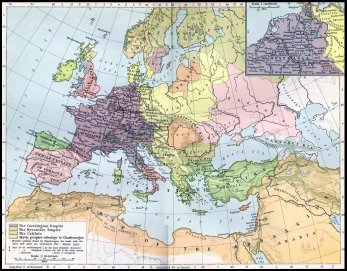

The Empire of 814 will be Cut in 3 Pieces a Generation Later.

(click to enlarge) |

The Carolingian Empire is Divided into 3 for Charlemagne's 3 Grandsons.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Papacy is also in trouble. The Holy See is increasingly torn by

factionalism. Intrigue becomes rampant. The papal office is bought and sold and

occasionally obtained by murder. The corruption and immorality of the Papacy

during this period will prompt later historians to call it a "pornocracy." The

infamous "Cadaver Synod" serves as a bizarre illustration of the turmoil in

Rome.

The body of former Pope Formosus (891-896) is exhumed by newly elected

Pope Stephen VI late in 896 and put on trial, charged with treason! The corpse

is dressed in papal regalia, assaulted with questions and accusations, then

dragged through the streets of Rome with a mob cheering on !

The next year, Pope Stephen is himself overthrown, imprisoned and

strangled. Sergius III, pope from 904 to 911, attains the office after ordering

the murder of his predecessor. His life of open sin with the noted prostitute

Marozia brings widespread disrepute upon the Papacy. Sergius fathers a number of

sons by Marozia, among them the future Pope John XI. Sergius' reign begins a

period known as "The Rule of the Harlots."

The Multiple Invasions of Europe in the 9

th Century.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Chaos reigns in Rome — and throughout Europe.

The situation is grave. It becomes clear to many that the disunity and weakness in Europe is tied closely

to the disunity and weakness of the Church — and vice versa. Perceptive churchmen

realize that they must call in a strong prince to again unite Europe. Western civilization must be saved !

With the Frankish realm in eclipse, Rome must look elsewhere for a

champion to resurrect the tradition of imperial unity. When the next great

Emperor appears in Western Europe in the middle of the 10th century, he will not

be a Frank but a Saxon German. As medieval Germany rises to a predominant

position in the West, the dignity of the title of Roman Emperor will become

permanently connected with that of the king of Germany.

The first German Reich is about to appear on the scene !

In the public interest.

Text by: Keith W. Stump