| Henry Gray (1821–1865). Anatomy of the Human Body. 1918. |

| |

| 2e. The Abdomen |

| |

| The abdomen is the largest cavity in the body. It is of an oval shape, the extremities of the oval being directed upward and downward. The upper extremity is formed by the diaphragm which extends as a dome over the abdomen, so that the cavity extends high into the bony thorax, reaching on the right side, in the mammary line, to the upper border of the fifth rib; on the left side it falls below this level by about 2.5 cm. The lower extremity is formed by the structures which clothe the inner surface of the bony pelvis, principally the Levator ani and Coccygeus on either side. These muscles are sometimes termed the diaphragm of the pelvis. The cavity is wider above than below, and measures more in the vertical than in the transverse diameter. In order to facilitate description, it is artificially divided into two parts: an upper and larger part, the abdomen proper; and a lower and smaller part, the pelvis. These two cavities are not separated from each other, but the limit between them is marked by the superior aperture of the lesser pelvis. | 1 |

| The abdomen proper differs from the other great cavities of the body in being bounded for the most part by muscles and fasciæ, so that it can vary in capacity and shape according to the condition of the viscera which it contains; but, in addition to this, the abdomen varies in form and extent with age and sex. In the adult male, with moderate distension of the viscera, it is oval in shape, but at the same time flattened from before backward. In the adult female, with a fully developed pelvis, it is ovoid with the narrower pole upward, and in young children it is also ovoid but with the narrower pole downward. | 2 |

| | | Boundaries.—It is bounded in front and at the sides by the abdominal muscles and the Iliacus muscles; behind by the vertebral column and the Psoas and Quadratus lumborum muscles; above by the diaphragm; below by the plane of the superior aperture of the lesser pelvis. The muscles forming the boundaries of the cavity are lined upon their inner surfaces by a layer of fascia. | 3 |

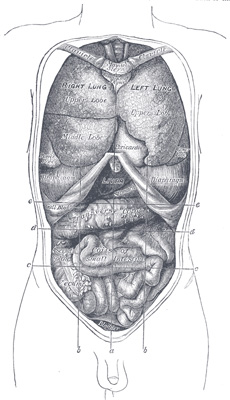

| The abdomen contains the greater part of the digestive tube; some of the accessory organs to digestion, viz., the liver and pancreas; the spleen, the kidneys, and the suprarenal glands. Most of these structures, as well as the wall of the cavity in which they are contained, are more or less covered by an extensive and complicated serous membrane, the peritoneum. | 4 |

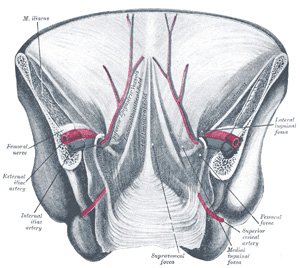

| | | The Apertures in the Walls of the Abdomen.—The apertures in the walls of the abdomen, for the transmission of structures to or from it, are, in front, the umbilical (in the fetus), for the transmission of the umbilical vessels, the allantois, and vitelline duct; above, the vena caval opening, for the transmission of the inferior vena cava, the aortic hiatus, for the passage of the aorta, azygos vein, and thoracic duct, and the esophageal hiatus, for the esophagus and vagi. Below, there are two apertures on either side: one for the passage of the femoral vessels and lumboinguinal nerve, and the other for the transmission of the spermatic cord in the male, and the round ligament of the uterus in the female. | 5 |

|

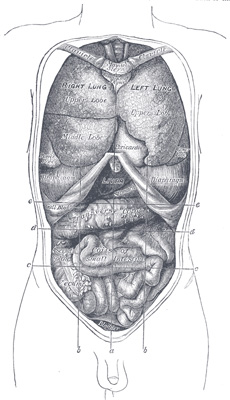

FIG. 1034– Front view of the thoracic and abdominal viscera. a. Median plane. b b. Lateral planes. c c. Trans tubercular plane. d d. Subcostal plane. e e. Transpyloric plane. (See enlarged image) | | |

| | | Regions.—For convenience of description of the viscera, as well as of reference to the morbid conditions of the contained parts, the abdomen is artificially divided into nine regions by imaginary planes, two horizontal and two sagittal, passing through the cavity, the edges of the planes being indicated by lines drawn on the surface of the body. Of the horizontal planes the upper or transpyloric is indicated by a line encircling the body at the level of a point midway between the jugular notch and the symphysis pubis, the lower by a line carried around the trunk at the level of a point midway between the transpyloric and the symphysis pubis. The latter is practically the intertubercular plane of Cunningham, who pointed out 163 that its level corresponds with the prominent and easily defined tubercle on the iliac crest about 5 cm. behind the anterior superior iliac spine. By means of these imaginary planes the abdomen is divided into three zones, which are named from above downward the subcostal, umbilical, and hypogastric zones. Each of these is further subdivided into three regions by the two sagittal planes, which are indicated on the surface by lines drawn vertically through points half-way between the anterior superior iliac spines and the symphysis pubis. 164 | 6 |

| The middle region of the upper zone is called the epigastric; and the two lateral regions, the right and left hypochondriac. The central region of the middle zone is the umbilical; and the two lateral regions, the right and left lumbar. The middle region of the lower zone is the hypogastric or pubic region; and the lateral regions are the right and left iliac or inguinal (Fig. 1034). | 7 |

| The pelvis is that portion of the abdominal cavity which lies below and behind a plane passing through the promontory of the sacrum, lineæ terminales of the hip bones, and the pubic crests. It is bounded behind by the sacrum, coccyx, Piriformes, and the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments; in front and laterally by the pubes and ischia and Obturatores interni; above it communicates with the abdomen proper; below it is closed by the Levatores ani and Coccygei and the urogenital diaphragm. The pelvis contains the urinary bladder, the sigmoid colon and rectum, a few coils of the small intestine, and some of the generative organs. | 8 |

| When the anterior abdominal wall is removed, the viscera are partly exposed as follows: above and to the right side is the liver, situated chiefly under the shelter of the right ribs and their cartilages, but extending across the middle line and reaching for some distance below the level of the xiphoid process. To the left of the liver is the stomach, from the lower border of which an apron-like fold of peritoneum, the greater omentum, descends for a varying distance, and obscures, to a greater or lesser extent, the other viscera. Below it, however, some of the coils of the small intestine can generally be seen, while in the right and left iliac regions respectively the cecum and the iliac colon are partly exposed. The bladder occupies the anterior part of the pelvis, and, if distended, will project above the symphysis pubis; the rectum lies in the concavity of the sacrum, but is usually obscured by the coils of the small intestine. The sigmoid colon lies between the rectum and the bladder. | 9 |

| When the stomach is followed from left to right it is seen to be continuous with the first part of the small intestine, or duodenum, the point of continuity being marked by a thickened ring which indicates the position of the pyloric valve. The duodenum passes toward the under surface of the liver, and then, curving downward, is lost to sight. If, however, the greater omentum be thrown upward over the chest, the inferior part of the duodenum will be observed passing across the vertebral column toward the left side, where it becomes continuous with the coils of the jejunum and ileum. These measure some 6 meters in length, and if followed downward the ileum will be seen to end in the right iliac fossa by opening into the cecum, the commencement of the large intestine. From the cecum the large intestine takes an arched course, passing at first upward on the right side, then across the middle line and downward on the left side, and forming respectively the ascending transverse, and descending parts of the colon. In the pelvis it assumes the form of a loop, the sigmoid colon, and ends in the rectum. | 10 |

| The spleen lies behind the stomach in the left hypochondriac region, and may be in part exposed by pulling the stomach over toward the right side. | 11 |

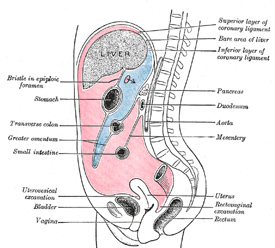

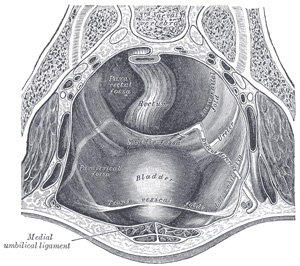

| The glistening appearance of the deep surface of the abdominal wall and of the surfaces of the exposed viscera is due to the fact that the former is lined, and the latter are more or less completely covered, by a serous membrane, the peritoneum. | 12 |

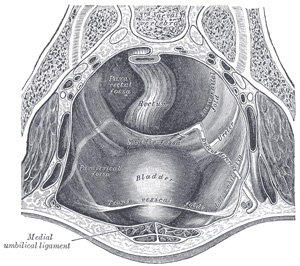

| | | the Peritoneum (Tunica Serosa)—The peritoneum is the largest serous membrane in the body, and consists, in the male, of a closed sac, a part of which is applied against the abdominal parietes, while the remainder is reflected over the contained viscera. In the female the peritoneum is not a closed sac, since the free ends of the uterine tubes open directly into the peritoneal cavity. The part which lines the parietes is named the parietal portion of the peritoneum; that which is reflected over the contained viscera constitutes the visceral portion of the peritoneum. The free surface of the membrane is smooth, covered by a layer of flattened mesothelium, and lubricated by a small quantity of serous fluid. Hence the viscera can glide freely against the wall of the cavity or upon one another with the least possible amount of friction. The attached surface is rough, being connected to the viscera and inner surface of the parietes by means of areolar tissue, termed the subserous areolar tissue. The parietal portion is loosely connected with the fascial lining of the abdomen and pelvis, but is more closely adherent to the under surface of the diaphragm, and also in the middle line of the abdomen. | 13 |

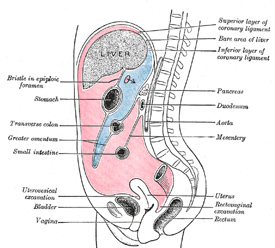

| The space between the parietal and visceral layers of the peritoneum is named the peritoneal cavity; but under normal conditions this cavity is merely a potential one, since the parietal and visceral layers are in contact. The peritoneal cavity gives off a large diverticulum, the omental bursa, which is situated behind the stomach and adjoining structures; the neck of communication between the cavity and the bursa is termed the epiploic foramen (foramen of Winslow). Formerly the main portion of the cavity was described as the greater, and the omental bursa as the lesser sac. | 14 |

| The peritoneum differs from the other serous membranes of the body in presenting a much more complex arrangement, and one that can be clearly understood only by following the changes which take place in the digestive tube during its development. | 15 |

| To trace the membrane from one viscus to another, and from the viscera to the parietes, it is necessary to follow its continuity in the vertical and horizontal directions, and it will be found simpler to describe the main portion of the cavity and the omental bursa separately. | 16 |

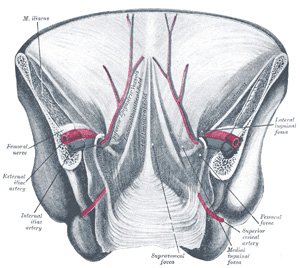

| | | Vertical Disposition of the Main Peritoneal Cavity (greater sac) (Fig. 1035).—It is convenient to trace this from the back of the abdominal wall at the level of the umbilicus. On following the peritoneum upward from this level it is seen to be reflected around a fibrous cord, the ligamentum teres (obliterated umbilical vein), which reaches from the umbilicus to the under surface of the liver. This reflection forms a somewhat triangular fold, the falciform ligament of the liver, attaching the upper and anterior surfaces of the liver to the diaphragm and abdominal wall. With the exception of the line of attachment of this ligament the peritoneum covers the whole of the under surface of the anterior part of the diaphragm, and is continued from it on to the upper surface of the right lobe of the liver as the superior layer of the coronary ligament, and on to the upper surface of the left lobe as the superior layer of the left triangular ligament of the liver. Covering the upper and anterior surfaces of the liver, it is continued around its sharp margin on to the under surface, where it presents the following relations: (a) It covers the under surface of the right lobe and is reflected from the back part of this on to the right suprarenal gland and upper extremity of the right kidney, forming in this situation the inferior layer of the coronary ligament; a special fold, the hepatorenal ligament, is frequently present between the inferior surface of the liver and the front of the kidney. From the kidney it is carried downward to the duodenum and right colic flexure and medialward in front of the inferior vena cava, where it is continuous with the posterior wall of the omental bursa. Between the two layers of the coronary ligament there is a large triangular surface of the liver devoid of peritoneal covering; this is named the bare area of the liver, and is attached to the diaphragm by areolar tissue. Toward the right margin of the liver the two layers of the coronary ligament gradually approach each other, and ultimately fuse to form a small triangular fold connecting the right lobe of the liver to the diaphragm, and named the right triangular ligament of the liver. The apex of the triangular bare area corresponds with the point of meeting of the two layers of the coronary ligament, its base with the fossa for the inferior vena cava. (b) It covers the lower surface of the quadrate lobe, the under and lateral surfaces of the gall-bladder, and the under surface and posterior border of the left lobe; it is then reflected from the upper surface of the left lobe to the diaphragm as the inferior layer of the left triangular ligament, and from the porta of the liver and the fossa for the ductus venosus to the lesser curvature of the stomach and the first 2.5 cm. of the duodenum as the anterior layer of the hepatogastric and hepatoduodenal ligaments, which together constitute the lesser omentum. If this layer of the lesser omentum be followed to the right it will be found to turn around the hepatic artery, bile duct, and portal vein, and become continuous with the anterior wall of the omental bursa, forming a free folded edge of peritoneum. Traced downward, it covers the antero-superior surface of the stomach and the commencement of the duodenum, and is carried down into a large free fold, known as the gastrocolic ligament or greater omentum. Reaching the free margin of this fold, it is reflected upward to cover the under and posterior surfaces of the transverse colon, and thence to the posterior abdominal wall as the inferior layer of the transverse mesocolon. It reaches the abdominal wall at the head and anterior border of the pancreas, is then carried down over the lower part of the head and over the inferior surface of the pancreas on the superior mesenteric vessels, and thence to the small intestine as the anterior layer of the mesentery. It encircles the intestine, and subsequently may be traced, as the posterior layer of the mesentery, upward and backward to the abdominal wall. From this it sweeps down over the aorta into the pelvis, where it invests the sigmoid colon, its reduplication forming the sigmoid mesocolon. Leaving first the sides and then the front of the rectum, it is reflected on to the seminal vesicles and fundus of the urinary bladder and, after covering the upper surface of that viscus, is carried along the medial and lateral umbilical ligaments (Fig. 1036) on to the back of the abdominal wall to the level from which a start was made. | 17 |

|

FIG. 1035– Vertical disposition of the peritoneum. Main cavity, red; omental bursa, blue. (See enlarged image) | | |

|

FIG. 1036– Posterior view of the anterior abdominal wall in its lower half. The peritoneum is in place, and the various cords are shining through. (After Joessel.) (See enlarged image) | | |

| Between the rectum and the bladder it forms, in the male, a pouch, the rectovesical excavation, the bottom of which is slightly below the level of the upper ends of the vesiculæ seminales—i. e., about 7.5 cm. from the orifice of the anus. When the bladder is distended, the peritoneum is carried up with the expanded viscus so that a considerable part of the anterior surface of the latter lies directly against the abdominal wall without the intervention of peritoneal membrane (prevesical space of Retzius). In the female the peritoneum is reflected from the rectum over the posterior vaginal fornix to the cervix and body of the uterus, forming the rectouterine excavation (pouch of Douglas). It is continued over the intestinal surface and fundus of the uterus on to its vesical surface, which it covers as far as the junction of the body and cervix uteri, and then to the bladder, forming here a second, but shallower, pouch, the vesicouterine excavation. It is also reflected from the sides of the uterus to the lateral walls of the pelvis as two expanded folds, the broad ligaments of the uterus, in the free margin of each of which is the uterine tube. | 18 |

| | | Vertical Disposition of the Omental Bursa (lesser peritoneal sac) (Fig. 1035).—A start may be made in this case on the posterior abdominal wall at the anterior border of the pancreas. From this region the peritoneum may be followed upward over the pancreas on to the inferior surface of the diaphragm, and thence on to the caudate lobe and caudate process of the liver to the fossa from the ductus venosus and the porta of the liver. Traced to the right, it is continuous over the inferior vena cava with the posterior wall of the main cavity. From the liver it is carried downward to the lesser curvature of the stomach and the commencement of the duodenum as the posterior layer of the lesser omentum, and is continuous on the right, around the hepatic artery, bile duct, and portal vein, with the anterior layer of this omentum. The posterior layer of the lesser omentum is carried down as a covering for the postero-inferior surfaces of the stomach and commencement of the duodenum, and is continued downward as the deep layer of the gastrocolic ligament or greater omentum. From the free margin of this fold it is reflected upward on itself to the anterior and superior surfaces of the transverse colon, and thence as the superior layer of the transverse mesocolon to the anterior border of the pancreas, the level from which a start was made. It will be seen that the loop formed by the wall of the omental bursa below the transverse colon follows, and is closely applied to, the deep surface of that formed by the peritoneum of the main cavity, and that the greater omentum or large fold of peritoneum which hangs in front of the small intestine therefore consists of four layers, two anterior and two posterior separated by the potential cavity of the omental bursa. | 19 |

| | | Horizontal Disposition of the Peritoneum.—Below the transverse colon the arrangement is simple, as it includes only the main cavity; above the level of the transverse colon it is more complicated on account of the existence of the omental bursa. Below the transverse colon it may be considered in the two regions, viz., in the pelvis and in the abdomen proper. | 20 |

|

FIG. 1037– The peritoneum of the male pelvis. (Dixon and Birmingham.) (See enlarged image) | | |

| (1) In the Pelvis.—The peritoneum here follows closely the surfaces of the pelvic viscera and the inequalities of the pelvic walls, and presents important differences in the two sexes. (a) In the male (Fig. 1037) it encircles the sigmoid colon, from which it is reflected to the posterior wall of the pelvis as a fold, the sigmoid mesocolon. It then leaves the sides and, finally, the front of the rectum, and is continued on to the upper ends of the seminal vesicles and the bladder; on either side of the rectum it forms a fossa, the pararectal fossa, which varies in size with the distension of the rectum. In front of the rectum the peritoneum forms the rectovesical excavation, which is limited laterally by peritoneal folds extending from the sides of the bladder to the rectum and sacrum. These folds are known from their position as the rectovesical or sacrogenital folds. The peritoneum of the anterior pelvic wall covers the superior surface of the bladder, and on either side of this viscus forms a depression, termed the paravesical fossa, which is limited laterally by the fold of peritoneum covering the ductus deferens. The size of this fossa is dependent on the state of distension of the bladder; when the bladder is empty, a variable fold of peritoneum, the plica vesicalis transversa, divides the fossa into two portions. On the peritoneum between the paravesical and pararectal fossæ the only elevations are those produced by the ureters and the hypogastric vessels. (b) In the female, pararectal and paravesical fossæ similar to those in the male are present: the lateral limit of the paravesical fossa is the peritoneum investing the round ligament of the uterus. The rectovesical excavation is, however, divided by the uterus and vagina into a small anterior vesicouterine and a large, deep, posterior rectouterine excavation. The sacrogenital folds form the margins of the latter, and are continued on to the back of the uterus to form a transverse fold, the torus uterinus. The broad ligaments extend from the sides of the uterus to the lateral walls of the pelvis; they contain in their free margins the uterine tubes, and in their posterior layers the ovaries. Below, the broad ligaments are continuous with the peritoneum on the lateral walls of the pelvis. On the lateral pelvic wall behind the attachment of the broad ligament, in the angle between the elevations produced by the diverging hypogastric and external iliac vessels is a slight fossa, the ovarian fossa, in which the ovary normally lies. | 21 |

|

FIG. 1038– Horizontal disposition of the peritoneum in the lower part of the abdomen. (See enlarged image) | | |

| (2) In the Lower Abdomen (Fig. 1038).—Starting from the linea alba, below the level of the transverse colon, and tracing the continuity of the peritoneum in a horizontal direction to the right, the membrane covers the inner surface of the abdominal wall almost as far as the lateral border of the Quadratus lumborum; it encloses the cecum and vermiform process, and is reflected over the sides and front of the ascending colon; it may then be traced over the duodenum, Psoas major, and inferior vena cava toward the middle line, whence it passes along the mesenteric vessels to invest the small intestine, and back again to the large vessels in front of the vertebral column, forming the mesentery, between the layers of which are contained the mesenteric bloodvessels, lacteals, and glands. It is then continued over the left Psoas; it covers the sides and front of the descending colon, and, reaching the abdominal wall, is carried on it to the middle line. | 22 |

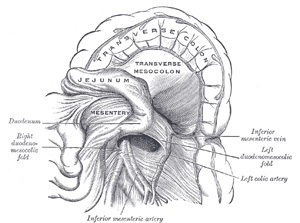

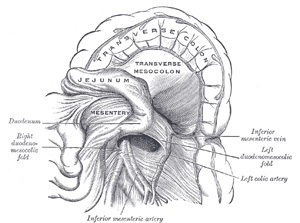

|

FIG. 1039– Horizontal disposition of the peritoneum in the upper part of the abdomen. (See enlarged image) | | |

| (3) In the Upper Abdomen (Fig. 1039).—Above the transverse colon the omental bursa is superadded to the general sac, and the communication of the two cavities with one another through the epiploic foramen can be demonstrated. | 23 |

| (a) Main Cavity.—Commencing on the posterior abdominal wall at the inferior vena cava, the peritoneum may be followed to the right over the front of the suprarenal gland and upper part of the right kidney on to the antero-lateral abdominal wall. From the middle line of the anterior wall a backwardly directed fold encircles the obliterated umbilical vein and forms the falciform ligament of the liver. Continuing to the left, the peritoneum lines the antero-lateral abdominal wall and covers the lateral part of the front of the left kidney, and is reflected to the posterior border of the hilus of the spleen as the posterior layer of the phrenicolienal ligament. It can then be traced around the surface of the spleen to the front of the hilus, and thence to the cardiac end of the greater curvature of the stomach as the anterior layer of the gastrolienal ligament. It covers the antero-superior surfaces of the stomach and commencement of the duodenum, and extends up from the lesser curvature of the stomach to the liver as the anterior layer of the lesser omentum. | 24 |

| (b) Omental Bursa (bursa omentalis; lesser peritoneal sac).—On the posterior abdominal wall the peritoneum of the general cavity is continuous with that of the omental bursa in front of the inferior vena cava. Starting from here, the bursa may be traced across the aorta and over the medial part of the front of the left kidney and diaphragm to the hilus of the spleen as the anterior layer of the phrenicolienal ligament. From the spleen it is reflected to the stomach as the posterior layer of the gastrosplenic ligament. It covers the postero-inferior surfaces of the stomach and commencement of the duodenum, and extends upward to the liver as the posterior layer of the lesser omentum; the right margin of this layer is continuous around the hepatic artery, bile duct, and portal vein, with the wall of the general cavity. | 25 |

| The epiploic foramen (foramen epiploicum; foramen of Winslow) is the passage of communication between the general cavity and the omental bursa. It is bounded in front by the free border of the lesser omentum, with the common bile duct, hepatic artery, and portal vein between its two layers; behind by the peritoneum covering the inferior vena cava; above by the peritoneum on the caudate process of the liver, and below by the peritoneum covering the commencement of the duodenum and the hepatic artery, the latter passing forward below the foramen before ascending between the two layers of the lesser omentum. | 26 |

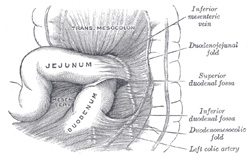

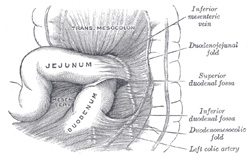

| The boundaries of the omental bursa will now be evident. It is bounded in front, from above downward, by the caudate lobe of the liver, the lesser omentum, the stomach, and the anterior two layers of the greater omentum. Behind, it is limited, from below upward, by the two posterior layers of the greater omentum, the transverse colon, and the ascending layer of the transverse mesocolon, the upper surface of the pancreas, the left suprarenal gland, and the upper end of the left kidney. To the right of the esophageal opening of the stomach it is formed by that part of the diaphragm which supports the caudate lobe of the liver. Laterally, the bursa extends from the epiploic foramen to the spleen, where it is limited by the phrenicolienal and gastrolienal ligaments. | 27 |

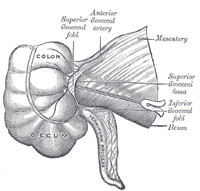

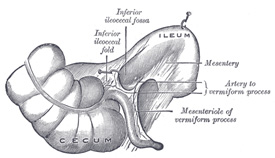

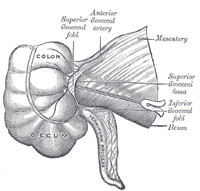

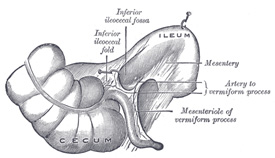

| The omental bursa, therefore, consists of a series of pouches or recesses to which the following terms are applied: (1) the vestibule, a narrow channel continued from the epiploic foramen, over the head of the pancreas to the gastropancreatic fold; this fold extends from the omental tuberosity of the pancreas to the right side of the fundus of the stomach, and contains the left gastric artery and coronary vein; (2) the superior omental recess, between the caudate lobe of the liver and the diaphragm; (3) the lienal recess, between the spleen and the stomach; (4) the inferior omental recess, which comprises the remainder of the bursa. | 28 |

| In the fetus the bursa reaches as low as the free margin of the greater omentum, but in the adult its vertical extent is usually more limited owing to adhesions between the layers of the omentum. During a considerable part of fetal life the transverse colon is suspended from the posterior abdominal wall by a mesentery of its own, the two posterior layers of the greater omentum passing at this stage in front of the colon. This condition occasionally persists throughout life, but as a rule adhesion occurs between the mesentery of the transverse colon and the posterior layer of the greater omentum, with the result that the colon appears to receive its peritoneal covering by the splitting of the two posterior layers of the latter fold. In the adult the omental bursa intervenes between the stomach and the structures on which that viscus lies, and performs therefore the functions of a serous bursa for the stomach. | 29 |

| Numerous peritoneal folds extend between the various organs or connect them to the parietes; they serve to hold the viscera in position, and, at the same time, enclose the vessels and nerves proceeding to them. They are grouped under the three headings of ligaments, omenta, and mesenteries. | 30 |

| The ligaments will be described with their respective organs. | 31 |

| There are two omenta, the lesser and the greater. | 32 |

| The lesser omentum (omentum minus; small omentum; gastrohepatic omentum) is the duplicature which extends to the liver from the lesser curvature of the stomach and the commencement of the duodenum. It is extremely thin, and is continuous with the two layers of peritoneum which cover respectively the antero-superior and postero-inferior surfaces of the stomach and first part of the duodenum. When these two layers reach the lesser curvature of the stomach and the upper border of the duodenum, they join together and ascend as a double fold to the porta of the liver; to the left of the porta the fold is attached to the bottom of the fossa for the ductus venosus, along which it is carried to the diaphragm, where the two layers separate to embrace the end of the esophagus. At the right border of the omentum the two layers are continuous, and form a free margin which constitutes the anterior boundary of the epiploic foramen. The portion of the lesser omentum extending between the liver and stomach is termed the hepatogastric ligament, while that between the liver and duodenum is the hepatoduodenal ligament. Between the two layers of the lesser omentum, close to the right free margin, are the hepatic artery, the common bile duct, the portal vein, lymphatics, and the hepatic plexus of nerves—all these structures being enclosed in a fibrous capsule (Glisson’s capsule). Between the layers of the lesser omentum, where they are attached to the stomach, run the right and left gastric vessels. | 33 |

| The greater omentum (omentum majus; great omentum; gastrocolic omentum) is the largest peritoneal fold. It consists of a double sheet of peritoneum, folded on itself so that it is made up of four layers. The two layers which descend from the stomach and commencement of the duodenum pass in front of the small intestines, sometimes as low down as the pelvis; they then turn upon themselves, and ascend again as far as the transverse colon, where they separate and enclose that part of the intestine. These individual layers may be easily demonstrated in the young subject, but in the adult they are more or less inseparably blended. The left border of the greater omentum is continuous with the gastrolienal ligament; its right border extends as far as the commencement of the duodenum. The greater omentum is usually thin, presents a cribriform appearance, and always contains some adipose tissue, which in fat people accumulates in considerable quantity. Between its two anterior layers, a short distance from the greater curvature of the stomach, is the anastomosis between the right and left gastroepiploic vessels. | 34 |

| The mesenteries are: the mesentery proper, the transverse mesocolon, and the sigmoid mesocolon. In addition to these there are sometimes present an ascending and a descending mesocolon. | 35 |

| The mesentery proper (mesenterium) is the broad, fan-shaped fold of peritoneum which connects the convolutions of the jejunum and ileum with the posterior wall of the abdomen. Its root—the part connected with the structures in front of the vertebral column—is narrow, about 15 cm. long, and is directed obliquely from the duodenojejunal flexure at the left side of the second lumbar vertebra to the right sacroiliac articulation (Fig. 1040). Its intestinal border is about 6 metres long; and here the two layers separate to enclose the intestine, and form its peritoneal coat. It is narrow above, but widens rapidly to about 20 cm., and is thrown into numerous plaits or folds. It suspends the small intestine, and contains between its layers the intestinal branches of the superior mesenteric artery, with their accompanying veins and plexuses of nerves, the lacteal vessels, and mesenteric lymph glands. | 36 |

| The transverse mesocolon (mesocolon transversum) is a broad fold, which connects the transverse colon to the posterior wall of the abdomen. It is continuous with the two posterior layers of the greater omentum, which, after separating to surround the transverse colon, join behind it, and are continued backward to the vertebral column, where they diverge in front of the anterior border of the pancreas. This fold contains between its layers the vessels which supply the transverse colon. | 37 |

| The sigmoid mesocolon (mesocolon sigmoideum) is the fold of peritoneum which retains the sigmoid colon in connection with the pelvic wall. Its line of attachment forms a V-shaped curve, the apex of the curve being placed about the point of division of the left common iliac artery. The curve beings on the medial side of the left Psoas major, and runs upward and backward to the apex, from which it bends sharply downward, and ends in the median plane at the level of the third sacral vertebra. The sigmoid and superior hemorrhoidal vessels run between the two layers of this fold. | 38 |

| In most cases the peritoneum covers only the front and sides of the ascending and descending parts of the colon. Sometimes, however, these are surrounded by the serous membrane and attached to the posterior abdominal wall by an ascending and a descending mesocolon respectively. A fold of peritoneum, the phrenicocolic ligament, is continued from the left colic flexure to the diaphragm opposite the tenth and eleventh ribs; it passes below and serves to support the spleen, and therefore has received the name of sustentaculum lienis. | 39 |

|

FIG. 1040– Diagram devised by Delépine to show the lines along which the peritoneum leaves the wall of the abdomen to invest the viscera. (See enlarged image) | | |

| The appendices epiploicæ are small pouches of the peritoneum filled with fat and situated along the colon and upper part of the rectum. They are chiefly appended to the transverse and sigmoid parts of the colon. | 40 |

|

FIG. 1041– Superior and inferior duodenal fossæ. (Poirier and Charpy.) (See enlarged image) | | |

|

FIG. 1042– Duodenojejunal fossa. (Poirier and Charpy.) (See enlarged image) | | |

| | | Peritoneal Recesses or Fossæ (retroperitoneal fossæ).—In certain parts of the abdominal cavity there are recesses of peritoneum forming culs-de-sac or pouches, which are of surgical interest in connection with the possibility of the occurrence of “retroperitoneal” herniæ. The largest of these is the omental bursa (already described), but several others, of smaller size, require mention, and may be divided into three groups, viz.: duodenal, cecal, and intersigmoid. | 41 |

| 1. Duodenal Fossæ (Figs. 1041, 1042).—Three are fairly constant, viz.: (a) The inferior duodenal fossa, present in from 70 to 75 per cent. of cases, is situated opposite the third lumbar vertebra on the left side of the ascending portion of the duodenum. Its opening is directed upward, and is bounded by a thin sharp fold of peritoneum with a concave margin, called the duodenomesocolic fold. The tip of the index finger introduced into the fossa under the fold passes some little distance behind the ascending portion of the duodenum. (b) The superior duodenal fossa, present in from 40 to 50 per cent. of cases, often coexists with the inferior one, and its orifice looks downward. It lies on the left of the ascending portion of the duodenum, in front of the second lumbar vertebra, and behind a sickle-shaped fold of peritoneum, the duodenojejunal fold, and has a depth of about 2 cm. (c) The duodenojejunal fossa exists in from 15 to 20 per cent. of cases, but has never yet been found in conjunction with the other forms of duodenal fossæ it can be seen by pulling the jejunum downward and to the right, after the transverse colon has been pulled upward. It is bounded above by the pancreas, to the right by the aorta, and to the left by the kidney; beneath is the left renal vein. It has a depth of from 2 to 3 cm., and its orifice, directed downward and to the right, is nearly circular and will admit the tip of the little finger. | 42 |

|

FIG. 1043– Superior ileocecal fossa. (Poirier and Charpy.) (See enlarged image) | | |

|

FIG. 1044– Inferior ileocecal fossa. The cecum and ascending colon have been drawn lateralward and downward, the ileum upward and backward, and the vermiform process downward. (Poirier and Charpy.) (See enlarged image) | | |

| 2. Cecal Fossæ (pericecal folds or fossæ).—There are three principal pouches or recesses in the neighborhood of the cecum (Figs. 1043 to 1045): (a) The superior ileocecal fossa is formed by a fold of peritoneum, arching over the branch of the ileocolic artery which supplies the ileocolic junction. The fossa is a narrow chink situated between the mesentery of the small intestine, the ileum, and the small portion of the cecum behind. (b) The inferior ileocecal fossa is situated behind the angle of junction of the ileum and cecum. It is formed by the ileocecal fold of peritoneum (bloodless fold of Treves), the upper border of which is fixed to the ileum, opposite its mesenteric attachment, while the lower border, passing over the ileocecal junction, joins the mesenteriole of the vermiform process, and sometimes the process itself. Between this fold and the mesenteriole of the vermiform process is the inferior ileocecal fossa. It is bounded above by the posterior surface of the ileum and the mesentery; in front and below by the ileocecal fold, and behind by the upper part of the mesenteriole of the vermiform process. (c) The cecal fossa is situated immediately behind the cecum, which has to be raised to bring it into view. It varies much in size and extent. In some cases it is sufficiently large to admit the index finger, and extends upward behind the ascending colon in the direction of the kidney; in others it is merely a shallow depression. It is bounded on the right by the cecal fold, which is attached by one edge to the abdominal wall from the lower border of the kidney to the iliac fossa and by the other to the postero-lateral aspect of the colon. In some instances additional fossæ, the retrocecal fossæ, are present. | 43 |

| 3. The intersigmoid fossa (recessus intersigmoideus) is constant in the fetus and during infancy, but disappears in a certain percentage of cases as age advances. Upon drawing the sigmoid colon upward, the left surface of the sigmoid mesocolon is exposed, and on it will be seen a funnel-shaped recess of the peritoneum, lying on the external iliac vessels, in the interspace between the Psoas and Iliacus muscles. This is the orifice leading to the intersigmoid fossa, which lies behind the sigmoid mesocolon, and in front of the parietal peritoneum. The fossa varies in size; in some instances it is a mere dimple, whereas in others it will admit the whole of the index finger. 165 | 44 |

|

FIG. 1045– The cecal fossa. The ileum and cecum are drawn backward and upward. (Souligoux.) (See enlarged image) | | |

| Note 164. Journal of Anatomy and Physiology, vols. xxxiii, xxxiv, xxxv. [back] |

| Note 165. On the anatomy of these fossæ, see the Arris and Gale Lectures by Moynihan, 1899. [back] |

|

|