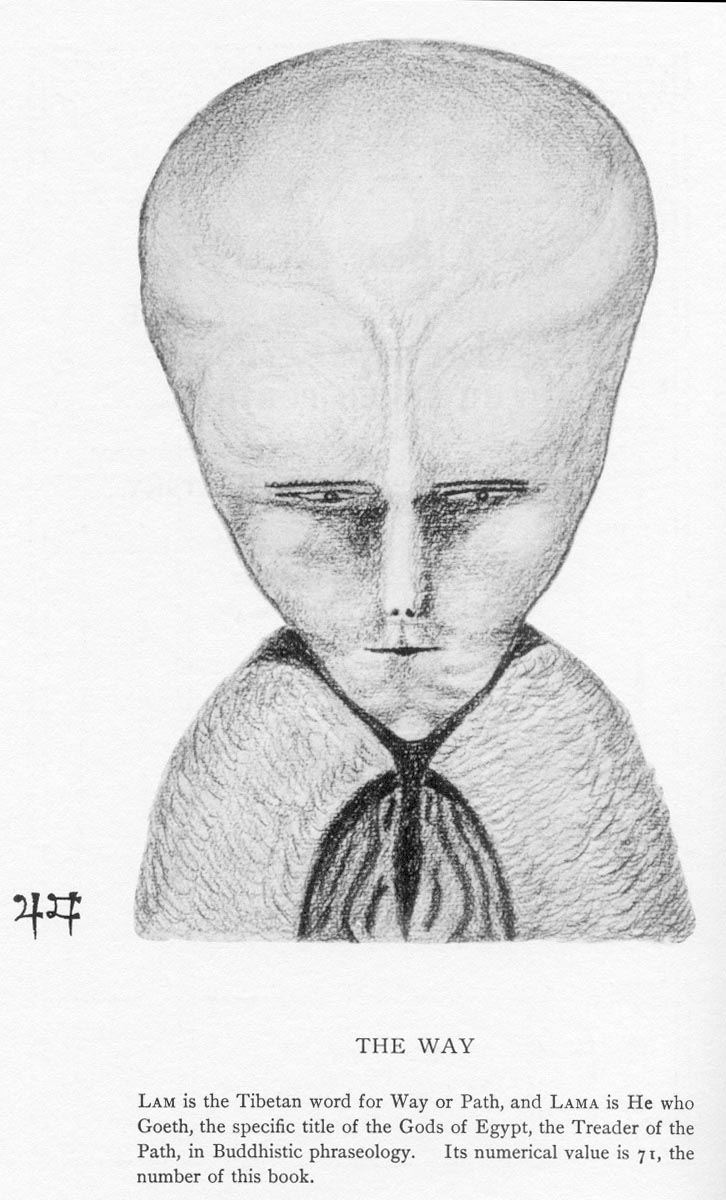

Figure 14. The Way.

Lam is the Tibetan word for Way or Path, and Lama is He who Goeth, the specific title of the Gods of Egypt, the Treader of the Path, in Buddhistic phraseology. Its numerical value is 71, the number of this book.

Prefatory Note

Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.

IT IS NOT VERY DIFFICULT to write a book, if one chance to possess the necessary degree of Initiation, and the power of expression. It is infernally difficult to comment on such a Book. The principal reason for this is that every statement is true and untrue, alternately, as one advances upon the Path of the Wise. The question always arises: For what grade is this Book meant? To give one simple concrete example, it is stated in the third part of this treatise that Change is the great enemy. This is all very well as meaning that one ought to stick to one’s job. But in another sense Change is the Great Friend. As it is marvelous well shewed forth by The Beast Himself in Liber Aleph, Love is the law, and Love is Change, by definition. Short of writing a separate interpretation suited for every grade, therefore, the commentator is in a bog of quandary which makes Flanders Mud seem like polished granite. He can only do his poor best, leaving it very much to the intelligence of each reader to get just what he needs. These remarks are peculiarly applicable to the present treatise; for the issues are presented in so confused a manner that one almost wonders whether Madame Blavatsky was not a reincarnation of the Woman with the Issue of Blood familiar to readers of the Gospels. It is astonishing and distressing to notice how the Lanoo, no matter what happens to him, soaring aloft like the phang, and sailing gloriously through innumerable Gates of High Initiation, nevertheless keeps his original Point of View, like a Bourbon. He is always getting rid of Illusions, but, like the entourage of the Cardinal Lord Arch bishop of Rheims after he cursed the thief, nobody seems one penny the worse—or the better.

Probably the best way to take the whole treatise is to assume that it is written for the absolute tyro, with a good deal between the lines for the more advanced mystic. This will excuse, to the mahatma-snob, a good deal of apparent triviality and crudity of standpoint. It is of course necessary for the commentator to point out just those things which the novice is not expected to see. He will have to shew mysteries in many grades, and each reader must glean his own wheat.

At the same time, the commentator has done a good deal to uproot some of the tares in the mind of the tyro aforesaid, which Madame Blavatsky was apparently content to let grow until the day of judgment. But that day is come since she wrote this Book; the New Æon is here, and its Word is Do what thou wilt. It is certainly time to give the order: Chautauqua est delenda.

Love is the law, love under will.

Fragments from the Book of the Golden Precepts

FRAGMENT I

The Voice of the Silence

[Madame Blavatsky’s notes are omitted in this edition, as they are diffuse, full of inaccuracies, and intended to mislead the presumptuous.—Ed.]

1. These instructions are for those ignorant of the dangers of the lower iddhi (magical powers).

Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. Nothing less can satisfy than this Motion in your orbit.

It is important to reject any iddhi of which you may become possessed. Firstly, because of the wasting of energy, which should rather be concentrated on further advance; and secondly, because iddhi are in many cases so seductive that they lead the unwary to forget altogether the real purpose of their endeavours.

The Student must be prepared for temptations of the most extraordinary subtlety; as the Scriptures of the Christians mystically put it, in their queer but often illuminating jargon, the Devil can disguise himself as an Angel of Light.

A species of parenthesis is necessary thus early in this Comment. One must warn the reader that he is going to swim in very deep waters. To begin with, it is assumed throughout that the student is already familiar with at least the elements of Mysticism. True, you are supposed to be ignorant of the dangers of the lower iddhi; but there are really quite a lot of people, even in Boston, who do not know that there are any iddhi at all, low or high. However, one who has been assiduous with Book 4, by Frater Perdurabo, should have no difficulty so far as a general comprehension of the subject-matter of the Book is concerned. Too ruddy a cheerfulness on the part of the assiduous one will however be premature, to say the least. For the fact is that this treatise does not contain an intelligible and coherent cosmogony. The unfortunate Lanoo is in the position of a sea-captain who is furnished with the most elaborate and detailed sailing-instructions, but is not allowed to have the slightest idea of what port he is to make, still less given a chart of the Ocean. One finds oneself accordingly in a sort of “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower came” atmosphere. That poem of Browning owes much of its haunting charm to this very circumstance, that the reader is never told who Childe Roland is, or why he wants to get to the Dark Tower, or what he expects to find when he does get there. There is a skillfully constructed atmosphere of Giants, and Ogres, and Hunchbacks, and the rest of the apparatus of fairy-tales; but there is no trace of the influence of Bædeker in the style. Now this is really very irritating to anybody who happens to be seriously concerned to get to that tower. I remember, as a boy, what misery I suffered over this poem. Had Browning been alive, I think I would have sought him out, so seriously did I take the Quest. The student of Blavatsky is equally handicapped. Fortunately, Book 4, Part III, comes to the rescue once more with a rough sketch of the Universe as it is conceived by Those who know it; and a regular investigation of that book, and the companion volumes ordered in “The Curriculum of the A∴ A∴,” fortified by steady persistence in practical personal exploration, will enable this Voice of the Silence to become a serious guide in some of the subtler obscurities which weigh upon the Eyelids of the Seeker.

2. He who would hear the voice of nāda, the “Soundless Sound,” and comprehend it, he has to learn the nature of dhāranā (concentrated thought).

The voice of nada is very soon heard by the beginner, especially during the practice of pranayama (control of breath-force). At first it resembles distant surf, though in the adept it is more like the twittering of innumerable nightingales; but this sound is premonitory, as it were, the veil of more distinct and articulate sounds which come later. It corresponds in hearing to that dark veil which is seen when the eyes are closed, although in this case a certain degree of progress is necessary before anything at all is heard.

3. Having become indifferent to objects of perception, the pupil must seek out the Rāja (King) of the senses, the Thought-Producer, he (sic!) who awakes illusion.

The word “indifferent” here implies “able to shut out.” The Rajah referred to is in that spot whence thoughts spring. He turns out ultimately to be Mayan, the great Magician described in the 3rd Æthyr (See The Equinox, Vol I no. 5, Special Supplement). Let the Student notice that in his early meditations, all his thoughts will be under the Tamo-Guna, the principle of Inertia and Darkness. When he has destroyed all those, he will be under the dominion of an entirely new set of the type of Rajo-Guna, the principle of Activity, and so on. To the advanced Student a simple ordinary thought, which seems little or nothing to the beginner, becomes a great and terrible fountain of iniquity, and the higher he goes, up to a certain point, the point of definitive victory, the more that is the case. The beginner can think, “it is ten o’clock,” and dismiss the thought. To the mind of the adept this sentence will awaken all its possible correspondences, all the reflections he has ever made on time, as also accidental sympathetics like Mr. Whistler’s essay; and if he is sufficiently far advanced, all these thoughts in their hundreds and thousands diverging from the one thought, will again converge, and become the resultant of all those thoughts. He will get samadhi upon that original thought, and this will be a terrible enemy to his progress.

4. The Mind is the great Slayer of the Real.

In the word “Mind” we should include all phenomena of Mind, including Samādhi itself. Any phenomenon has causes and produces results, and all these things are below the “REAL.” By the REAL is here meant the NIBBANADHATU.

5. Let the Disciple slay the Slayer. For—

This is a corollary of Verse 4. These texts may be interpreted in a quite elementary sense. It is of course the object of even the beginner to suppress mind and all its manifestations, but only as he advances will he discover what Mind means.

6. When to himself his form appears unreal, as do on waking all the forms he sees in dreams;

This is a somewhat elementary result. Concentration on any subject leads soon enough to a sudden and overwhelming conviction that the object is unreal. The reason of this may perhaps be—speaking philosophically—that the object, whatever it is, has only a relative existence. (See The Equinox, vol. I, no. 4, p. 159).

7. When he has ceased to hear the many, he may discern the ONE—the inner sound which kills the outer.

By the “many” are meant primarily noises which take place outside the Student, and secondly, those which take place inside him. For example, the pulsation of the blood in the ears, and later the mystic sounds which are described in Verse 40.

8. Then only, not till then, shall he forsake the region of ASAT, the false, to come unto the realm of SAT, the true.

By “SAT, the true,” is meant a thing previous to the “REAL” referred to above. SAT itself is an illusion. Some schools of philosophy have a higher ASAT, Not-Being, which is beyond SAT, and consequently is to Shivadarshana as SAT is to Atmadarshana. Nirvana is beyond both these.

9. Before the soul can see, the Harmony within must be attained, and fleshly eyes be rendered blind to all illusion.

By the “Harmony within” is meant that state in which neither objects of sense, nor physiological sensations, nor emotions, can disturb the concentration of thought.

10. Before the Soul can hear, the image (man) has to become as deaf to roarings as to whispers, to cries of bellowing elephants as to the silvery buzzing of the golden fire-fly.

In the text the image is explained as “Man,” but it more properly refers to the consciousness of man, which consciousness is considered as being a reflection of the Non-Ego, or a creation of the Ego, according to the school of philosophy to which the Student may belong.

11. Before the soul can comprehend and may remember, she must unto the Silent Speaker be united just as the form to which the clay is modeled, is first united with the potter’s mind.

Any actual object of the senses is considered as a precipitation of an ideal. Just as no existing triangle is a pure triangle, since it must be either equilateral, isosceles, or scalene, so every object is a miscarriage of an ideal. In the course of practice one concentrates upon a given thing, rejecting this outer appearance and arriving at that ideal, which of course will not in any way resemble any of the objects which are its incarnations. It is with this in view that the verse tells us that the Soul must be united to the Silent Speaker. The words “Silent Speaker” may be considered as a hieroglyph of the same character as Logos, אדני or the Ineffable Name.

12. For then the soul will hear and will remember.

The word “hear” alludes to the tradition that hearing is the organ of Spirit, just as seeing is that of Fire. The word “remember” might be explained as “will attain to memory.” Memory is the link between the atoms of consciousness, for each successive consciousness of Man is a single phenomenon, and has no connection with any other. A looking-glass knows nothing of the different people that look into it. It only reflects one at a time. The brain is however more like a sensitive plate, and memory is the faculty of bringing up into consciousness any picture required. As this occurs in the normal man with his own experiences, so it occurs in the Adept with all experiences. (This is one more reason for His identifying Himself with others.)

13. And then to the inner ear will speak— THE VOICE OF THE SILENCE. And say:—

What follows must be regarded as the device of the poet, for of course the “Voice of the Silence” cannot be interpreted in words. What follows is only its utterance in respect of the Path itself.

14. If thy soul smiles while bathing in the Sunlight of thy Life; if thy soul sings within her chrysalis of flesh and matter; if thy soul weeps inside her castle of illusion; if thy soul struggles to break the silver thread that binds her to the MASTER; know, O Disciple, thy Soul is of the earth.

In this verse the Student is exhorted to indifference to everything but his own progress. It does not mean the indifference of the Man to the things around him, as it has often been so unworthily and wickedly interpreted. The indifference spoken of is a kind of inner indifference. Everything should be enjoyed to the full, but always with the reservation that the absence of the thing enjoyed shall not cause regret. This is too hard for the beginner, and in many cases it is necessary for him to abandon pleasures in order to prove to himself that he is indifferent to them, and it may be occasionally advisable even for the Adept to do this now and again. Of course during periods of actual concentration there is no time whatever for anything but the work itself; but to make even the mildest asceticism a rule of life is the gravest of errors, except perhaps that of regarding Asceticism as a virtue. This latter always leads to spiritual pride, and spiritual pride is the principal quality of the brother of the Left-hand Path.

“Ascetic” comes from the Greek άσκέο “to work curiously, to adorn, to exercise, to train.” The Latin ars is derived from this same word. Artist, in its finest sense of creative craftsman, is therefore the best translation. The word has degenerated under Puritan foulness.

15. When to the World’s turmoil thy budding soul lends ear; when to the roaring voice of the great illusion thy Soul responds; when frightened at the sight of the hot tears of pain, when deafened by the cries of distress, thy soul withdraws like the shy turtle within the carapace of SELFHOOD, learn, O Disciple, of her Silent “God,” thy Soul is an unworthy shrine.

This verse deals with an obstacle at a more advanced stage. It is again a warning not to shut one’s self up in one’s own universe. It is not by the exclusion of the Non-Ego that saintship is attained, but by its inclusion. Love is the law, love under will.

16. When waxing stronger, thy Soul glides forth from her secure retreat; and breaking bose from the protecting shrine, extends her silver thread and rushes onward; when beholding her image on the waves of Space she whispers, “This is I,” —declare, O Disciple, that thy Soul is caught in the webs of delusion.

An even more advanced instruction, but still connected with the question of the Ego and the non-Ego. The phenomenon described is perhaps Ātmadarshana, which is still a delusion, in one sense still a delusion of personality; for although the Ego is destroyed in the Universe, and the Universe in it, there is a distinct though exceedingly subtle tendency to sum up its experience as Ego.

These three verses might be interpreted also as quite elementary; v. 14 as blindness to the First Noble Truth “Everything is Sorrow”; v. 15 as the coward’s attempt to escape Sorrow by Retreat; and v. 16 as the acceptance of the Astral as SAT.

17. This Earth, Disciple, is the Hall of Sorrow, wherein are set along the Path of dire probations, traps to ensnare thy EGO by the delusion called “Great Heresy.”

Develops still further these remarks.

18. This earth, O ignorant Disciple, is but the dismal entrance leading to the twilight that precedes the valley of true light—that light which no wind can extinguish, that light which burns without a wick or fuel.

“Twilight” here may again refer to Ātmadarshana. The last phrase is borrowed from Eliphas Lévi, who was not (I believe) a Tibetan of antiquity. [Madame Blavatsky humorously pretended that this Book is an ancient Tibetan writing.—Ed.]

19. Saith the Great Law:—”In order to become the KNOWER of ALL-SELF, thou hast first of SELF to be the knower.” To reach the knowledge of that SELF, thou hast to give up Self to Non-Self, Being to Non-Being, and then thou canst repose between the wings of the GREAT BIRD. Aye, sweet is rest between the wings of that which is not born, nor dies, but is the AUM throughout eternal ages.

The words “give up” may be explained as “yield” in its subtler or quasi-masochistic erotic sense, but on a higher plane. In the following quotation from the “Great Law” it explains that the yielding is not the beginning but the end of the Path.

- Then let the End awake. Long hast thou slept, O great God Terminus! Long ages hast thou waited at the end of the city and the roads thereof.

Awake Thou! wait no more!- Nay, Lord! but I am come to Thee. It is I that wait at last.

- The prophet cried against the mountain; come thou hither, that I may speak with thee!

- The mountain stirred not. Therefore went the prophet unto the mountain, and spake unto it. But the feet of the prophet were weary, and the mountain heard not his voice.

- But I have called unto Thee, and I have journeyed unto Thee, and it availed me not.

- I waited patiently, and Thou wast with me from the beginning.

- This now I know, O my beloved, and we are stretched at our ease among the vines.

- But these thy prophets; they must cry aloud and scourge themselves; they must cross trackless wastes and unfathomed oceans; to await Thee is the end, not the beginning. [LXV, II, 55-62]

AUM is here quoted as the hieroglyph of the Eternal. “A” the beginning of sound, “U” its middle, and “M” its end, together form a single word or Trinity, indicating that the Real must be regarded as of this three-fold nature, Birth, Life and Death, not successive, but one. Those who have reached trances in which “time” is no more will understand better than others how this may be.

20. Bestride the Bird of Life, if thou would’st know.

The word “know” is specially used here in a technical sense. Avidya, ignorance, the first of the fetters, is moreover one which includes all the others.

With regard to this Swan “Aum” compare the following verses from the “Great Law,” “Liber LXV,” 11:17—25.

- Also the Holy One came upon me, and I beheld a white swan floating in the blue.

- Between its wings I sate, and the æons fled away.

- Then the swan flew and dived and soared, yet no whither we went.

- A little crazy boy that rode with me spake unto the swan, and said:

- Who art thou that dost float and fly and dive and soar in the inane? Behold, these many æons have passed; whence camest thou? Whither wilt thou go?

- And laughing I chid him, saying: No whence! No whither!

- The swan being silent, he answered: Then, if with no goal, why this eternal journey?

- And I laid my head against the Head of the Swan, and laughed, saying: Is there not joy ineffable in this aimless winging? Is there not weariness and impatience for who would attain to some goal?

- And the swan was ever silent. Ah! but we floated in the infinite Abyss. Joy! Joy!

White swan, bear thou ever me up between thy wings!

21. Give up thy life, if thou would’st live.

This verse may be compared with similar statements in the Gospels, in The Vision and the Voice, and in the Books of Thelema. It does not mean asceticism in the sense usually under stood by the world. The 12th Æthyr (see The Equinox, vol. I, no. 5, Supplement) gives the clearest explanation of this phrase.

22. Three Halls, O weary pilgrim, lead to the end of toils. Three Halls, O conqueror of Mara, will bring thee through three states into the fourth and thence into the seven worlds, the worlds of Rest Eternal.

If this had been a genuine document I should have taken the three states to be Sirotāpanna, etc., and the fourth Arhat, for which the reader should consult “Science and Buddhism” and similar treatises. But as it is better than “genuine,” being, like The Chymical Marriage of Christian Rosencreutz, the forgery of a great adept, one cannot too confidently refer it thus. For the “Seven Worlds” are not Buddhism.

23. If thou would’st learn their names, then hearken, and remember. The name of the first Hall is IGNORANCE —Avidyā. It is the Hall in which thou saw’s the light, in which thou livest and shalt die.

These three Halls correspond to the gunas: Ignorance, tamas; Learning, rajas; Wisdom, sattva.

Again, ignorance corresponds to Malkuth and Nephesch (the animal soul), Learning to Tiphareth and Ruach (the mind), and Wisdom to Binah and Neschamah (the aspiration or Divine Mind).

24. The name of Hall the second is the Hall of LEARNING. In it thy Soul will find the blossoms of life, but under every flower a serpent coiled.

This Hall is a very much larger region than that usually under stood by the Astral World. It would certainly include all states up to dhyāna. The Student will remember that his “rewards” immediately transmute themselves into temptations.

25. The name of the third Hall is Wisdom, beyond which stretch the shoreless waters of AKSHARA, the indestructible Fount of Omniscience.

Akshara is the same as the Great Sea of the Qabalah. The reader must consult The Equinox for a full study of this Great Sea.

26. If thou would’st cross the first Hall safely, let not thy mind mistake the fires of lust that burn therein for the Sunlight of life.

The metaphor is now somewhat changed. The Hall of ignorance represents the physical life. Note carefully the phraseology, “let not thy mind mistake the fires of lust.” It is legitimate to warm yourself by those fires so long as they do not deceive you.

27. If thou would’st cross the second safely, stop not the fragrance of its stupefying blossoms to inhale. if freed thou would’st be from the karmic chains, seek not for thy guru in those māyāvic regions.

A similar lesson is taught in this verse. Do not imagine that your early psychic experiences are Ultimate Truth. Do not become a slave to your results.

28. The WISE ONES tarry not in pleasure-grounds of senses.

This lesson is confirmed. The wise ones tarry not. That is to say, they do not allow pleasure to interfere with business.

29. The WISE ONES heed not the sweet-tongued voices of illusion.

The wise ones heed not. They listen to them, but do not necessarily attach importance to what they say.

30. Seek for him who is to give thee birth, in the Hall of Wisdom, the Hall which lies beyond, wherein all shadows are unknown, and where the light of truth shines with unfading glory.

This apparently means that the only reliable guru is one who has attained the grade of Magister Templi. For the attainments of this grade consult The Equinox, vol. I, no. 5, Supplement, etc.

31. That which is uncreate abides in thee, Disciple, as it abides in that Hall. If thou would’st reach it and blend the two, thou must divest thyself of thy dark garments of illusion. Stifle the voice of flesh, allow no image of the senses to get between its light and thine that thus the twain may blend in one. And having learnt thine own ajñāna, flee from the Hall of Learning. This Hall is dangerous in its perfidious beauty, is needed but for thy probation. Beware, Lanoo, lest dazzled by illusive radiance thy Soul should linger and be caught in its deceptive light.

This is a résumé of the previous seven verses. It inculcates the necessity of unwavering aspiration, and in particular warns the advanced Student against accepting his rewards. There is one method of meditation in which the Student kills thoughts as they arise by the reflection, “That’s not it.” Frater P. indicated the same by taking as his motto, in the Second Order which reaches from Yesod to Chesed, “ΟΥ ΜΗ,” “No, certainly not!”

32. This light shines from the jewel of the Great Ensnarer, (Māra). The senses it bewitches, blinds the mind, and leaves the unwary an abandoned wreck.

I am inclined to believe that most of Blavatsky’s notes are intended as blinds. “Light” such as is described has a technical meaning. It would be too petty to regard Mara as a Christian would regard a man who offered him a cigarette. The supreme and blinding light of this jewel is the great vision of Light. It is the light which streams from the threshold of nirvāna, and Māra is the “dweller on the threshold.” It is absurd to call this light “evil” in any commonplace sense. It is the two-edged sword, flaming every way, that keeps the gate of the Tree of Life. And there is a further Arcanum connected with this which it would be improper here to divulge.

33. The moth attracted to the dazzling flame of thy night lamp is doomed to perish in the viscid oil. The unwary Soul that fails to grapple with the mocking demon of illusion, will return to earth the slave of Māra.

The result of failing to reject rewards is the return to earth. The temptation is to regard oneself as having attained, and so do no more work.

34. Behold the Hosts of Souls. Watch how they hover o’er the stormy sea of human life, and how exhausted, bleeding, broken-winged, they drop one after other on the swelling waves. Tossed by the fierce winds, chased by the gale, they drift into the eddies and disappear within the first great vortex

In this metaphor is contained a warning against identifying the Soul with human life, from the failure of its aspirations.

35. If through the Hall of Wisdom, thou would’st reach the Vale of Bliss, Disciple, close fast thy senses against the great dire heresy of separateness that weans thee from the rest.

This verse reads at first as if the heresy were still possible in the Hall of Wisdom, but this is not as it seems. The Disciple is urged to find out his Ego and slay it even in the beginning.

36. Let not thy “Heaven-born,” merged in the sea of mäyā, break from the Universal Parent (SOUL), but let the fiery power retire into the inmost chamber, the chamber of the Heart, and the abode of the World’s Mother.

This develops verse 35. The heaven-born is the human consciousness. The chamber of the Heart is the Anahata lotus. The abode of the World’s Mother is the Mulādhāra lotus. But there is a more technical meaning yet—and this whole verse describes a particular method of meditation, a final method, which is far too difficult for the beginner. (See, however, The Equinox, on all these points

37. Then from the heart that Power shall rise into the sixth, the middle region, the place between thin eyes, when it becomes the breath of the ONE-SOUL, the voice which filleth all, thy Master’s voice.

This verse teaches the concentration of the kundalini in the Ajñā Cakra. “Breath” is that which goes to and fro, and refers to the uniting of Shiva with Shakti in the Sahasrara. (See The Equinox.)

38. ‘Tis only then thou canst become a “Walker of the Sky” who treads the winds above the waves, whose step touches not the waters.

This partly refers to certain Iddhi, concerning Understanding of Devas (gods), etc.; here the word “wind” may be interpreted as “spirit.” It is comparatively easy to reach this state, and it has no great importance. The “walker of the sky” is much superior to the mere reader of the minds of ants.

39. Before thou set’st thy foot upon the ladder’s upper rung, the ladder of the mystic sounds, thou hast to hear the voice of thy INNER GOD in seven manners.

The word “seven” is here, as so frequently, rather poetic than mathematic; for there are many more. The verse also reads as if it were necessary to hear all the seven, and this is not the case— some will get one and some another. Some students may even miss all of them.

(This might happen as the result of his having conquered, and uprooted them, and “fried their seeds” in a previous birth.)

40. The first is like the nightingale’s sweet voice chanting a song of parting to its mate.

The second comes as the sound of a silver cymbal of the dhyānis, awakening the twinkling stars.

The next is as the plaint melodious of the ocean-sprite imprisoned in its shell.

And this is followed by the chant of Vina (the Hindu lute).

The fifth like sound of bamboo-flute shrills in thine ear. It changes next into a trumpet-blast.

The last vibrates like the dull rumbling of a thunder cloud.

The seventh swallows all the other sounds. They die, and then are heard no more.

The first four are comparatively easy to obtain, and many people can hear them at will. The last three are much rarer, not necessarily because they are more difficult to get, and indicate greater advance, but because the protective envelope of the Adept is become so strong that they cannot pierce it. The last of the seven sometimes occurs, not as a sound, but as an earthquake, if the expression may be permitted. It is a mingling of terror and rapture impossible to describe, and as a general rule it completely discharges the energy of the Adept, leaving him weaker than an attack of Malaria would do; but if the practice has been right, this soon passes off, and the experience has this advantage, that one is far less troubled with minor phenomena than before. It is just possible that this is referred to in the Apocalypse XVI, XVII, XVIII.

41. When the six are slain and at the Master’s feet are laid, then is the pupil merged into the ONE, becomes that ONE and lives therein.

The note tells that this refers to the six principles, so that the subject is completely changed. By the slaying of the principles is meant the withdrawal of the consciousness from them, their rejection by the seeker of truth. Sabhapaty Swāmi has an excellent method on these lines; it is given, in an improved form, in Liber HHH. (See The Equinox, vol. I, no. 5, p. 5; also Book 4, Part III, app, VII.)

42. Before that path is entered, thou must destroy thy lunar body, cleanse thy mind-body and make clean thy heart.

The Lunar body is Nephesch, and the Mind body Ruach. The heart is Tiphareth, the centre of Ruach.

43. Eternal life’s pure waters, clear and crystal, with the monsoon tempest’s muddy torrents cannot mingle.

We are now again on the subject of suppressing thought. The pure water is the stilled mind, the torrent the mind invaded by thoughts.

44. Heaven’s dew-drop glittering in the morn’s first sun beam within the bosom of the lotus, when dropped on earth becomes a piece of clay; behold, the pearl is now a speck of mire.

This is not a mere poetic image. This dew-drop in the lotus is connected with the mantra “Aum Mani Padme Hum,” and to what this verse really refers is known only to members of the ninth degree of O.T.O.

45. Strive with thy thoughts unclean before they overpower thee. Use them as they will thee, for if thou sparest them and they take root and grow, know well, these thoughts will overpower and kill thee. Beware, Disciple, suffer not, e’en though it be their shadow, to approach. For it will grow, increase in size and power, and then this thing of darkness will absorb thy being before thou hast well realized the black four monster’s presence.

The text returns to the question of suppressing thoughts. Verse 44 has been inserted where it is in the hope of deluding the reader into the belief that it belongs to verses 43 and 45, for the Arcanum which it contains is so dangerous that it must be guarded in all possible ways. Perhaps even to call attention to it is a blind intended to prevent the reader from looking for something else.

46. Before the “mystic Power” can make of thee a god, Lanoo, thou must have gained the faculty to slay thy lunar form at will.

It is now evident that by destroying or slaying is not meant a permanent destruction. If you can slay a thing at will it means that you can revive it at will, for the word “faculty” implies repeated action.

47. The Self of Matter and the Self of Spirit can never meet. One of the twain must disappear; there is no place for both.

This is a very difficult verse, because it appears so easy. It is not merely a question of Advaitism, it refers to the spiritual marriage. [Advaitism is a spiritual Monism—Ed.]

48. Ere thy Soul’s mind can understand, the bud of personality must be crushed out, the worm of sense destroyed past resurrection.

This is again filled with deeper meaning than that which appears on the surface. The words “bud” and “worm” form a clue.

49. Thou canst not travel on the Path before thou hast become that Path itself.

Compare the scene in Parsifal, where the scenery comes to the knight instead of the knight going to the scenery. But there is also implied the doctrine of the tao, and only one who is an accomplished Taoist can hope to understand this verse. (See “The Hermit of Esopus Island,” of The Magical Record of the Beast 666, to be published in The Equinox, vol. III)

50. Let thy Soul lend its ear to every cry of pain like as the lotus bares its heart to drink the morning sun.

51. Let not the fierce sun dry one tear of pain before thyself hast wiped it from the sufferer’s eye.

52. But let each burning human tear drop on thy heart and there remain; nor ever brush it off, until the pain that caused it is removed.

This is a counsel never to forget the original stimulus which has driven you to the Path, the “first noble truth.” Everything is now “good.” This is why verse 53 says that these tears are the streams that irrigate the fields of charity immortal. (Tears, by the way. Think!)

53. These tears, O thou of heart most merciful, these are the streams that irrigate the fields of charity immortal. ‘Tis on such soil that grows the midnight blossom of Buddha, more difficult to find, more rare to view than is the flowers of the Vogay tree. It is the seed of freedom from rebirth. It isolates the Arhat both from strife and lust, it leads him through the fields of Being unto the peace and bliss known only in the land of Silence and Non-Being.

The “midnight blossom” is a phrase connected with the doctrine of the Night of Pan, familiar to Masters of the Temple. “The Poppy that flowers in the dusk” is another name for it. A most secret Formula of Magick is connected with this “Heart of the Circle.”

54. Kill out desire; but if thou killest it take heed lest from the dead it should again rise.

By “desire” in all mystic treatises of any merit is meant tendency. Desire is manifested universally in the law of gravitation, in that of chemical attraction, and so on; in fact, everything that is done is caused by the desire to do it, in this technical sense of the word. The “midnight blossom” implies a certain monastic Renunciation of all desire, which reaches to all planes. One must however distinguish between desire, which means unnatural attraction to an ideal, and love, which is natural Motion.

55. Kill love of life, but if thou slayest tanhā, let this not be for thirst of life eternal, but to replace the fleeting by the everlasting.

This particularizes a special form of desire. The English is very obscure to any one unacquainted with Buddhist literature. The “everlasting” referred to is not a life-condition at all.

56. Desire nothing. Chafe not at karma, nor at Nature’s changeless laws. But struggle only with the personal, the transitory, the evanescent and the perishable.

The words “desire nothing” should be interpreted positively as well as negatively. The main sense of the rest of the verse is to advise the Disciple to work, and not to complain.

57. Help Nature and work on with her; and Nature will regard thee as one of her creators and make obeisance.

Although the object of the Disciple is to transcend Law, he must work through Law to attain this end.

It may be remarked that this treatise—and this comment for the most part—is written for disciples of certain grades only. It is altogether inferior to such Books as Liber CXI Aleph; but for that very reason, more useful, perhaps, to the average seeker.

58. And she will open wide before thee the portals of her secret chambers, lay bare before thy gaze the treasures hidden in the depths of her pure virgin bosom. Unsullied by the hand of matter she shows her treasures only to the eye of Spirit—the eye which never closes, the eye for which there is no veil in all her kingdoms.

This verse reminds one of the writings of Alchemists; and it should be interpreted as the best of them would have interpreted it.

59. Then will she show thee the means and way, the first gate and the second, the third, up to the very seventh. And then, the goal—beyond which he, bathed in the sunlight of the Spirit, glories untold, unseen by any save the eye of Soul.

These gates are described in the third treatise. The words “spirit” and “soul” are highly ambiguous, and had better be regarded as poetic figures, without a technical meaning being sought.

60. There is but one road to the Path; at its very end alone the “Voice of the Silence” can be heard. The ladder by which the candidate ascends is formed of rungs of suffering and pain; these can be silenced only by the voice of virtue. Woe, then, to thee, Disciple, if there is one single vice thou hast not left behind. For then the ladder will give way and overthrow thee; its foot rests in the deep mire of thy sins and failings, and ere thou canst attempt to cross this wide abyss of matter thou hast to lave thy feet in Waters of Renunciation. Beware lest thou should’st set a foot still soiled upon the ladder’s lowest rung. Woe unto him who dares pollute one rung with miry feet. The foul and viscous mud will dry, become tenacious, then glue his feet unto the spot, and like a bird caught in the wily fowler’s lime, he will be stayed from further progress. His vices will take shape and drag him down. His sins will raise their voices like as the jackal’s laugh and sob after the sun goes down; his thoughts become an army, and bear him off a captive slave.

A warning against any impurity in the original aspiration of the Disciple. By impurity is meant, and should always be meant, the mingling (as opposed to the combination) of two things. Do one thing at a time. This is particularly necessary in the matter of the aspiration. For if the aspiration be in any way impure, it means divergence in the will itself; and this is will’s one fatal flaw. It will however be understood that aspiration constantly changes and develops with progress. The beginner can only see a certain distance. Just so with our first telescopes we discovered many new stars, and with each improvement in the instrument we have discovered more. The second and more obvious meaning in the verse preaches the practice of yama, niyama, before serious practice is started, and this in actual life means, map out your career as well as you can. Decide to do so many hours’ work a day in such conditions as may be possible. It does not mean that you should set up neuroses and hysteria by suppressing your natural instincts, which are perfectly right on their own plane, and only wrong when they invade other planes, and set up alien tyrannies.

61. Kill thy desires, Lanoo, make thy vices impotent, ere the first step is taken on the solemn journey.

By “desires” and “vices” are meant those things which you your self think to be inimical to the work; for each man they will be quite different, and any attempt to lay down a general rule leads to worse than confusion.

62. Strangle thy sins, and make them dumb for ever, before thou dost lift one foot to mount the ladder.

This is merely a repetition of verse 61 in different language. But remember: “The word of Sin is Restriction.” “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.”

63. Silence thy thoughts and fix thy whole attention on thy Master whom yet thou dost not see, but whom thou feelest.

This again commands the stilling of thoughts. The previous verses referred rather to emotions, which are the great stagnant pools on which the mosquito thought breeds. Emotions are objectionable, as they represent an invasion of the mental plane by sensory or moral impressions.

64. Merge into one sense thy senses, if thou would’st be secure against the foe. ‘Tis by that sense alone which lies concealed within the hollow of thy brain, that the steep path which leadeth to thy Master may be disclosed before thy Soul’s dim eyes.

This verse refers to a Meditation practice somewhat similar to those described in Liber 831. (See The Equinox, also Book 4, Part III, appendix VII.)

65. Long and weary is the way before thee, O Disciple. One single thought about the past that thou hast left behind, will drag thee down and thou wilt have to start the climb anew.

Remember Lot’s wife.

66. Kill in thyself all memory of past experiences. Look not behind or thou art lost.

Remember Lot’s wife.

It is a division of Will to dwell in the past. But one’s past experiences must be built into one’s Pyramid, as one advances, layer by layer. One must also remark that this verse only applies to those who have not yet come co reconcile past, present, and future. Every incarnation is a Veil of Isis.

67. Do not believe that lust can ever be killed out if gratified or satiated, for this is an abomination inspired by Māra. It is by feeding vice that it expands and waxes strong, like to the worm that fattens on the blossom’s heart.

This verse must not be taken in its literal sense. Hunger is not conquered by starvation. One’s attitude to all the necessities which the traditions of earthly life involve should be to rule them, neither by mortification nor by indulgence. In order co do the work you must keep in proper physical and mental condition. Be sane. Asceticism always excites the mind, and the object of the Disciple is to calm it. However, ascetic originally meant athletic, and it has only acquired its modern meaning on account of the corruptions that crept into the practices used by those in “training.” The prohibitions, relatively valuable, were exalted into general rules. To “break training” is not a sin for anyone who is not in training. Incidentally, it takes all sorts to make a world. Imagine the stupidity of a universe full of Arhans! All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.

68. The rose must re-become the bud born of its parent stem, before the parasite has eaten through its heart and drunk its life-sap.

The English is here ambiguous and obscure, but the meaning is that it is important to achieve the Great Work while you have youth and energy.

69. The golden tree puts forth its jewel-buds before its trunk is withered by the storm.

Repeats this in clearer language.

70. The Pupil must regain THE CHILD-STATE HE HAS LOST ere the first sound can fall upon his ear.

Compare the remark of “Christ,” “Except ye become as little children ye shall in no wise enter into the Kingdom of Heaven,” and also, “Ye must be born again.” It also refers to the over coming of shame and of the sense of sin. If you think the Temple of the Holy Ghost to be a pig-stye, it is certainly improper to perform therein the Mass of the Graal. Therefore purify and consecrate yourselves; and then, Kings and Priests unto God, perform ye the Miracle of the One Substance.

Here is written also the Mystery of Harpocrates. One must become the “Unconscious” (of Jung), the Phallic or Divine Child or Dwarf-Self.

71. The light from the ONE MASTER, the one unfading golden light of Spirit, shoots its effulgent beams on the disciple from the very first. its rays thread through the thick, dark clouds of Matter.

The Holy Guardian Angel is already aspiring to union with the Disciple, even before his aspiration is formulated in the latter.

72. Now here, now there, these rays illumine it, like sun sparks light the earth through the thick foliage of jungle growth. But, O Disciple, unless the flesh is passive, head cool, the soul as firm and pure as flaming diamond, the radiance will not reach the chamber, its sunlight will not warm the heart, nor will the mystic sounds of Ākāsic heights reach the ear, however eager, at the initial stage.

The uniting of the Disciple with his Angel depends upon the former. The Latter is always at hand. “Akashic heights”—the dwelling-place of Nuit.

73. Unless thou hearest, thou canst not see. Unless thou seest, thou canst not hear. To hear and see this is the second stage.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

This is an obscure verse. It implies that the qualities of fire and Spirit commingle to reach the second stage. There is evidently a verse missing, or rather omitted, as may be understood by the row of dots; this presumably refers to the third stage. This third stage may be found by the discerning in Liber 831.

74. When the disciple sees and hears, and when he smells and tastes, eyes closed, ears shut, with mouth and nostrils stopped; when the four senses blend and ready are to pass into the fifth, that of the inner touch—then into stage the fourth he hath passed on.

The practice indicated in verse 74 is described in most books upon the Tatwas. The orifices of the face being covered with the fingers, the senses take on a new shape.

75. And in the fifth, O slayer of thy thoughts, all these again have to be killed beyond reanimation.

It is not sufficient to get rid temporarily of one’s obstacles. One must seek out their roots and destroy them, so that they can never rise again. This involves a very deep psychological investigation, as a preliminary. But the whole matter is one between the Self and its modifications, not at all between the Instrument and its gates. To kill out the sense of sight is nor achieved by removing the eyes. This mistake has done more to obscure the Path than any other, and has been responsible for endless misery.

76. Withhold thy mind from ah external objects, all external sights. Withhold internal images, lest on thy Soul-light a dark shadow they should cast.

This is the usual instruction once more, but, going further, it intimates that the internal image or reality of the object must be destroyed as well as the outer image and the ideal image.

77. Thou art now in dhāranā, the sixth stage.

DHARANA has been explained thoroughly in Book 4, q.v.

78. When thou hast passed into the seventh, O happy one, thou shall perceive no more the sacred three, for thou shalt have become that three thyself. Thyself and mind, like twins upon a line, the star which is thy goal, burns overhead. The three that dwell in glory and in bliss ineffable, now in the world of māyā have host their names. They have become one star, the fire that burns but scorches not, that fire which is the upādhi of the Flame.

It would be a mistake to attach more than a poetic meaning to these remarks upon the sacred Three; but Ego, non-Ego, and That which is formed from their wedding, are here referred to. There are two Triangles of especial importance to mystics; one is the equilateral, the other that familiar to the Past Master in Craft Masonry. The last sentence in the text refers to the “Seed” of Fire, the “Ace of Wands,” the “Lion-Serpent,” the “Dwarf-Self,” the “Winged Egg,” etc., etc., etc.

79. And this, O yogin of success, is what men call dhyāna, the right precursor of samādhi.

These states have been sufficiently, and much better, described in Book 4, q.v.

80. And now thy Self is lost in SELF, thyself unto THYSELF, merged in THAT SELF from which thou first didst radiate.

In this verse is given a hint of the underlying philosophical theory of the Cosmos. See Liber CXI for a full and proper account of this.

81. Where is thy individuality, Lanoo, where the Lanoo himself? It is the spark lost in the fire, the drop within the ocean, the ever-present Ray become the ALL and the eternal radiance.

Again principally poetical. The man is conceived as a mere accretion about his “Dwarf-Self,” and he is now wholly absorbed therein. For IT is also ALL, being of the Body of Nuit.

82. And now, Lanoo, thou art the doer and the witness, the radiator and the radiation, Light in the Sound, and the Sound in the Light.

Important, as indicating the attainment of a mystical state, in which you are not only involved in an action, but apart from it. There is a higher state described in the Bhagavad-gita. “I who am all, and made it all, abide its separate Lord.”

83. Thou art acquainted with the five impediments, O blessed one. Thou art their conqueror, the Master of the sixth, deliverer of the four modes of Truth. The Light that falls upon them shines from thyself, O thou who wast Disciple but art Teacher now.

The five impediments are usually taken to be the five senses. In this case the term “Master of the sixth” becomes of profound significance. The “sixth sense” is the race-instinct, whose common manifestation is in sex; this sense is then the birth of the Individual or Conscious Self with the “Dwarf-Self,” the Silent Babe, Harpocrates. The “four modes of Truth” (noble Truths) are adequately described in “Science and Buddhism.” (See Crowley, Collected Works.)

84. And of these modes of Truth:—

Hast thou not passed through knowledge of all misery—Truth the first?

85. Hast thou not conquered the Māras’ King at Tsi, the portal of assembling—truth the second?

86. Hast thou not sin at the third gate destroyed and truth the third attained?

87. Hast thou not entered Tau, “the Path” that leads to knowledge—the fourth truth?

The reference to the “Māras’ King” confuses the second truth with the third. The third Truth is a mere corollary of the Second, and the Fourth a Grammar of the Third.

88. And now, rest ‘neath the bodhi tree, which is perfection of all knowledge, for, know, thou art the Master of samādhi—the state of faultless vision.

This account of Samadhi is very incongruous. Throughout the whole treatise Hindu ideas are painfully mixed with Buddhist, and the introduction of the “four noble truths” comes very strangely as the precursor of verses 88 and 89.

89. Behold! thou hast become the light, thou hast become the Sound, thou art thy Master and thy God. Thou art THYSELF the object of thy search: the VOICE unbroken, that resounds throughout eternities, exempt from change, from sin exempt, the seven sounds in one,

THE VOICE OF THE SILENCE

Om Tat Sat.

This is a pure peroration, and clearly involves an egocentric metaphysic.

The style of the whole treatise is characteristically occidental.

Fragments from the Book of the Golden Precepts

FRAGMENT II

The Two Paths

1. And now, O Teacher of Compassion, point thou the way to other men. Behold, all those who knocking for admission, await [sic] in ignorance and darkness, to see the gate of the Sweet Law flung open!

This begins with the word “And,” rather as if it were a sequel to “The Voice of the Silence.” It should not be assumed that this is the case. However, assuming that the first Fragment explains the Path as far as Master of the Temple, it is legitimate to regard this second Fragment, so called, as the further instruction; for the Master of the Temple must leave his personal progress to attend to that of other people, a task from which, I am bound to add, even the most patient of Masters feels at times a tendency to revolt!

2. The voice of the Candidates:

Shalt not thou, Master of thine own Mercy, reveal the doctrine of the Heart? Shalt thou refuse to lead thy Servants unto the Path of Liberation?

One is compelled to remark a certain flavour of sentimentality in the exposition of the “Heart doctrine,” perhaps due to the increasing age and weight of the Authoress. The real reason of the compassion (so-called) of the Master is a perfectly practical and sensible one. It has nothing to do with the beautiful verses, “It is only the sorrows of others Cast their shadows over me.” The Master has learnt the first noble truth: “Everything is sorrow,” and he has learnt that there is no such thing as separate existence. Existence is one. He knows these things as facts, just as he knows that two and two make four. Consequently, although he has found the way of escape for that fraction of consciousness which he once called “I,” and although he knows that not only that consciousness, but all other consciousnesses, are but part of an illusion, yet he feels that his own task is not accomplished while there remains any fragment of consciousness thus unemancipated from illusion. Here we get into very deep metaphysical difficulties, but that cannot be helped, for the Master of the Temple knows that any statement, however simple, involves metaphysical difficulties which are not only difficult, but insoluble. On the plane of which Reason is Lord, all antinomies are irreconcilable. It is impossible for any one below the grade of Magister Templi even to begin to comprehend the resolution of them. This fragment of the imaginary “Book of the Golden Precepts” must be studied without ever losing sight of this fact.

3. Quoth the Teacher:

The Paths are two; the great Perfections three; six are the Virtues that transform the body into the Tree of Knowledge.

The “Tree of Knowledge” is of course another euphemism, the “Dragon Tree” representing the uniting of the straight and the curved. A further description of the Tree under which Gautama sat and attained emancipation is unfit for this elementary comment. Aum Mani Padme Hum.

4. Who shall approach them?

Who shall first enter them?

Who shall first hear the doctrine of two Paths in one, the truth unveiled about the Secret Heart? The Law which, shunning learning, teaches Wisdom, reveals a tale of woe.

This expression “two Paths in one” is intended to convey a hint that this fragment has a much deeper meaning than is apparent. The key should again be sought in Alchemy.

5. Alas, alas, that all men should possess Alaya, be one with the great Soul, and that possessing it, Alaya should so little avail them!

6. Behold how like the moon, reflected in the tranquil waves, Alaya is reflected by the small and by the great, is mirrored in the tiniest atoms, yet fails to reach the heart of all. Alas, that so few men should profit by the gift, the priceless boon of learning truth, the right perception of existing things, the Knowledge of the non existent!

This is indeed a serious metaphysical complaint. The solution of it is not to be found in reason.

7. Saith the Pupil:

O Teacher, what shall I do to reach to Wisdom?

O Wise one, what, to gain perfection?

8. Search for the Paths. But, O Lanoo, be of clean heart before thou startest on thy journey. Before thou takest thy first step learn to discern the real from the false, the ever-fleeting from the everlasting. Learn above all to separate Head-learning from Soul-Wisdom, the “Eye” from the “Heart” doctrine.

The Authoress of these treatises is a little exacting in the number of things that you have to do before you take your first step, most of them being things which more nearly resemble the difficulties of the last step. But by learning to distinguish the “real from the false” is only meant a sort of elementary discernment between things that are worth having and those that are not worth having, and, of course, the perception will alter with advance in knowledge. By “Head-learning” is meant the contents of the Ruach (mind) or manahs. Chiah is subconsciousness in its best sense, that subliminal which is sublime. The “Eye” doctrine then means the exoteric, the “Heart” doctrine the esoteric. Of course, in a more secret doctrine still, there is an Eye Doctrine which transcends the Heart Doctrine as that transcends this lesser Eye Doctrine.

9. Yea, ignorance is like unto a closed and airless vessel; the soul a bird shut up within. It warbles not, nor can it stir a feather; but the songster mute and torpid sits, and of exhaustion dies.

The Soul, ātman, despite its possession of the attributes omni science, omnipotence, omnipresence, etc., is entirely bound and blindfolded by ignorance. The metaphysical puzzle to which this gives rise cannot be discussed here—it is insoluble by reason, though one may call attention to the inherent incommensurability of a postulated absolute with an observed relative.

10. But even ignorance is better than Head-learning with no Soul-wisdom to illuminate and guide it.

The word “better” is used rather sentimentally, for, as “It is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all,” so it is better to be a madman than an idiot. There is always a chance of putting wrong right. As, however, the disease of the age is intellectualism, this lesson is well to teach. Numerous sermons on this point will be found in many of the writings of Frater Perdurabo.

11. The seeds of Wisdom cannot sprout and grow in airless space. To live and reap experience the mind needs breadth and depth and points to draw it towards the Diamond Soul. Seek not those points in māyä’s realm; but soar beyond illusions, search the eternal and the changeless SAT, mistrusting fancy’s false suggestions.

Compare what is said in Book 4, Part II, about the Sword. In the last part of the verse the adjuration is somewhat obvious, and it must be remembered that with progress the realm of Maya constantly expands as that of sat diminishes. In orthodox Buddhism this process continues indefinitely. There is also the resolution SAT = ASAT.

12. For mind is like a mirror; it gathers dust while it reflects. It needs the gentle breezes of Soul-Wisdom to brush away the dust of our illusions. Seek, O Beginner, to blend thy Mind and Soul.

The charge is to eliminate rubbish from the Mind, and teaches that Soul-wisdom is the selective agent. But these Fragments will be most shamefully misinterpreted if a trace of sentimentality is allowed to creep in. “Soul-wisdom” does not mean “piety” and “nobility” and similar conceptions, which only flourish where truth is permanently lost, as in England. Soul-wisdom here means the Will. You should eliminate from your mind anything which does not subserve your real purpose. It was, however, said in verse 11 that the “mind needs breadth,” and this also is true, but if all the facts known to the Thinker are properly coordinated and connected causally, and by necessity, the ideal mind will be attained, for although complex it will be unified. And if the summit of its pyramid be the Soul, the injunction in this verse 12 to the Beginner will be properly observed.

13. Shun ignorance, and likewise shun illusion. Avert thy face from world deceptions; mistrust thy senses, they are false. But within thy body—the shrine of thy sensations—seek in the Impersonal for the “eternal man”; and having sought him out, look inward: thou art Buddha.

“Shun ignorance”: Keep on acquiring facts.

“Shun illusion”: Refer every fact to the ultimate reality. “Interpret every phenomenon as a particular dealing of God with your Soul.”

“Mistrust thy senses”: Avoid superficial judgment of the facts which they present to you.

The last paragraph gives too succinct a statement of the facts. The attainment of the knowledge of the Holy Guardian Angel is only the “next step.” It does not imply Buddhahood by any means.

14. Shun praise, O Devotee. Praise leads to self-delusion. Thy body is not self, thy SELF is in itself without a body, and either praise or blame affects it not.

Pride is an expansion of the Ego, and the Ego must be destroyed. Pride is its protective sheath, and hence exceptionally dangerous, but this is a mystical truth concerning the inner life. The Adept is anything but a “creeping Jesus.”

15. Self-gratulation, O disciple, is like unto a lofty tower, up which a haughty fool has climbed. Thereon he sits in prideful solitude and unperceived by any but himself.

Develops this: but, this treatise being for beginners as well as for the more advanced, a sensible commonplace reason is given for avoiding pride, in that it defeats its own object.

16. False learning is rejected by the Wise, and scattered to the Winds by the good Law. Its wheel revolves for all, the humble and the proud. The “Doctrine of the Eye” is for the crowd, the “Doctrine of the Heart” for the elect. The first repeat in pride: “Behold, I know,” the last, they who in humbleness have garnered, low confess, “thus have I heard.”

Continues the subject, but adds a further Word to discriminate from Daäth (knowledge) in favour of Binah (understanding).

17. “Great Sifter” is the name of the “Heart Doctrine,” O disciple.

This explains the “Heart Doctrine” as a process of continual elimination which refers both to the aspirants and to the thoughts.

18. The wheel of the good Law moves swiftly on. It grinds by night and day. The worthless husks it drives from out the golden grain, the refuse from the flour. The hand of karma guides the wheel; the revolutions mark the beatings of the karmic heart.

The subject of elimination is here further developed. The favourite Eastern image of the Wheel of the Good Law is difficult to Western minds, and the whole metaphor appears to us somewhat confused.

19. True knowledge is the flour, false learning is the husk. If thou would’st eat the bread of Wisdom, thy flour thou hast to knead with Amrita’s clear waters. But if thou kneadest husks with māyā’s dew, thou canst create but food for the black doves of death, the birds of birth, decay and sorrow.

“Amrita” means not only Immortality, but is the technical name of the Divine force which descends upon man, but which is burnt up by his tendencies, by the forces which make him what he is. It is also a certain Elixir which is the Menstruum of Harpocrates.

Amrita here is best interpreted thus, for it is in opposition to “māyā.” To interpret illusion is to make confusion more confused.

20. If thou art told that to become Arhan thou hast to cease to love all beings—tell them they lie.

Here begins an instruction against Asceticism, which has always been the stumbling block most dreaded by the wise. “Christ” said that John the Baptist came neither eating nor drinking, and the people called him mad. He himself came eating and drinking; and they called him a gluttonous man and a wine bibber, a friend of publicans and sinners. The Adept does what he likes, or rather what he wills, and allows nothing to interfere with it, but because he is ascetic in the sense that he has no appetite for the stale stupidities which fools call pleasure, people expect him to refuse things both natural and necessary. Some people are so hypocritical that they claim their dislikes as virtue, and so the poor, weedy, unhealthy degenerate who cannot smoke because his heart is out of order, and cannot drink because his brain is too weak to stand it, or perhaps because his doctor has forbidden him to do either for the next two years, the man who is afraid of life, afraid to do anything lest some result should follow, is acclaimed as the best and greatest of mankind.

It is very amusing in England to watch the snobbishness, particularly of the middle classes, and their absurd aping of their betters, while the cream of the jest is that the morality to which the middle classes cling does not exist in good society. Those who have Master Souls refuse to be bound by anything but their own wills. They may refrain from certain actions because their main purpose would be interfered with, just as a man refrains from smoking if he is training for a boat-race; and those in whom cunning is stronger than self-respect sometimes dupe the populace by ostentatiously refraining from certain actions, while, however, they perform them in private. Especially of recent years, some Adepts have thought it wise either to refrain or to pretend to refrain from various things in order to increase their influence. This is a great folly. What is most necessary to demonstrate is that the Adept is not less but more than a man. It is better to hit your enemy and be falsely accused of malice, than to refrain from hitting him and be falsely accused of cowardice.

21. If thou art told that to gain liberation thou hast to hate thy mother and disregard thy son; to disavow thy father and call him “householder”; for man and beast all pity to renounce—tell them their tongue is false.

This verse explains that the Adept has no business to break up his domestic circumstances. The Rosicrucian Doctrine that the Adept should be a man of the world, is much nobler than that of the hermit. If the Ascetic Doctrine is carried to its logical conclusion, a stone is holier than Buddha himself. Read, however, “Liber CLVI.” (See The Equinox, also Book 4, part III, appendix vii

22. Thus teach the Tirthikas, the unbelievers.

It is a little difficult to justify the epithet “unbeliever”—it seems to me that on the contrary they are the believers. Scepticism is sword and shield to the wise man.

But by scepticism one does not mean the sneering infidelity of a Bolingbroke, or the gutter-snipe agnosticism of a Harry Boulter, which are crude remedies against a very vulgar colic.

23. If thou art taught that sin is born of action and bliss of absolute inaction, then tell them that they err. Non-permanence of human action, deliverance of mind from thralldom by the cessation of sin and faults, are not for “deva Egos.” Thus saith the “Doctrine of the Heart.”

This Doctrine is further developed. The term “deva Egos” is again obscure. The verse teaches that one should not be afraid to act. Action must be fought by reaction, and tyranny will never be overthrown by slavish submission to it. Cowardice is conquered by a course of exposing oneself unnecessarily to danger. The desire of the flesh has ever grown stronger for ascetics, as they endeavored to combat it by abstinence, and when with old age their functions are atrophied, they proclaim vaingloriously “I have conquered.” The way to conquer any desire is to under stand it, and freedom consists in the ability to decide whether or no you will perform any given action. The Adept should always be ready to abide by the toss of a coin, and remain absolutely indifferent as to whether it falls head or tail.

24. The Dharma (Law) of the “Eye” is the embodiment of the external, and the non-existing.

By “non-existing” is meant the lower Asat. The word is used on other occasions to mean an Asat which is higher than, and beyond, Sat.

25. The Dharma of the “Heart” is the embodiment of Bodhi, the Permanent and Everlasting.

“Bodhi” implies the root “Light” in its highest sense of L.V.X. But, even in Hindu Theory, παντα ρει.

26. The Lamp burns bright when wick and oil are clean. To make them clean a cleaner is required. The flame feels not the process of the cleaning. “The branches of the tree are shaken by the wind; the trunk remains unmoved.”

This verse again refers to the process of selection and elimination already described. The aspiration must be considered as unaf fected by this process except in so far as it becomes brighter and clearer in consequence of it. The last sentence seems again to refer to this question of asceticism. The Adept is not affected by his actions.

27. Both action and inaction may find room in thee; thy body agitated, thy mind tranquil, thy Soul as limpid as a mountain lake.

This repeats the same lesson. The Adept may plunge into the work of the world, and undertake his daily duties and pleasures exactly as another man would do, but he is not moved by them as the other man is.

28. Wouldst thou become a yogin of “Time’s Circle”?

Then, O Lanoo:

29. Believe thou not that sitting in dark forests, in proud seclusion and apart from men; believe thou not that life on roots and plants, that thirst assuaged with snow from the great Range—believe thou not, O Devotee, that this will lead thee to the goal of final liberation.

30. Think not that breaking bone, that rending flesh and muscle, unites thee to thy “silent Self.” Think not, that when the sins of thy gross form are conquered, O Victim of thy Shadows, thy duty is accomplished by nature and by man.

Once again the ascetic life is forbidden. It is moreover shown to be a delusion that the ascetic life assists liberation. The ascetic thinks that by reducing himself to the condition of a vegetable he is advanced upon the path of Evolution. It is not so. Minerals have no inherent power of motion save intramolecularly. Plants grow and move, though but little. Animals are free to move o every direction, and space itself is no hindrance to the higher principles of man. Advance is in the direction of more continuous and more untiring energy.

31. The blessed ones have scorned to do so. The Lion of the Law, the Lord of Mercy, perceiving the true cause of human woe, immediately forsook the sweet but selfish rest of quiet wilds. From Aranyani He became the Teacher of mankind. After Julai had entered the Nirvana, He preached on mount and plain, and held discourses in the cities, to devas, men and gods.

Reference is here made to the attainment of the Buddha. It was only after he had abandoned the Ascetic Life that he attained, and so far from manifesting that attainment by non-action, he created a revolution in India by attacking the Caste system, and by preaching his law created a karma so violent that even today its primary force is still active. The present “Buddha,” the Master Therion, is doing a similar, but even greater work, by His proclamation: Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.

32. Sow kindly acts and thou shalt reap their fruition. Inaction in a deed of mercy becomes an action in a deadly sin.

Thus saith the Sage.

This continues the diatribe against non-action, and points out that the Ascetic is entirely deluded when he supposes that doing nothing has no effect. To refuse to save life is murder.

33. Shalt thou abstain from action? Not so shall gain thy soul her freedom. To reach Nirvana one must reach Self-Knowledge, and Self-Knowledge is of loving deeds the child.

Continues the subject. The basis of knowledge is experience.

34. Have patience, Candidate, as one who fears no failure, courts no success. Fix thy Soul’s gaze upon the star whose ray thou art, the flaming star that shines within the lightless depths of ever-being, the boundless fields of the Unknown.

The Candidate is exhorted to patience and one-pointedness, and, further to an indifference to the result which comes of true confidence that that result will follow. Cf. Liber CCXX 1:44: “For pure will, unassuaged of purpose, delivered from the lust of result, is every way perfect.”

35. Have perseverance as one who doth for evermore endure. Thy shadows live and vanish; that which in thee shall live for ever, that which in thee knows, for it is knowledge, is not of fleeting life; it is the Man that was, that is, and will be, for whom the hour shall never strike.

Compare Lévi’s aphorism, “The Magician should work as though he had omnipotence at his command and eternity at his disposal.” Do not imagine that it matters whether you finish the task in this life or not. Go on quietly and steadily, unmoved by anything whatever.

36. If thou would’st reap sweet peace and rest, Disciple, sow with the seeds of merit the fields of future harvests. Accept the woes of birth.

Accept the Laws of Nature and work with them. Do not be always trying to take short cuts. Do not complain, and do not be afraid of the length of the Path. This treatise being for beginners, reward is offered. And—it is really worthwhile. One may find oneself in the Office of a Buddha.

- Yea, cried the Holy One, and from Thy spark will I the Lord kindle a great light; I will burn through the great city in the old and desolate land; I will cleanse it from its great impurity.

- And thou, O prophet, shalt see these things, and thou shalt heed them not.

- Now is the Pillar established in the Void; now is Asi fulfilled of Asar; now is Hoor let down into the Animal Soul of Things like a fiery star that falleth upon the darkness of the earth.

- Through the midnight thou art dropt, O my child, my conqueror, my sword-girt captain, O Hoor! and they shall find thee as a black gnarl’d glittering stone, and they shall worship thee.

37. Step out from sunlight into shade, to make more room for others. The tears that water the parched soil of pain and sorrow, bring forth the blossoms and the fruits of karmic retribution. Out of the furnace of man’s life and its black smoke, winged flames arise, flames purified, that soaring onward, ‘neath the karmic eye, weave in the end the fabric glorified of the three vestures of the Path.

Now the discourse turns to the question of the origin of Evil. The alchemical theory is here set forth. The first matter of the work is not so worthy as the elixir, and it must pass through the state of the Black Dragon to attain thereto.

38. These vestures are: Nirmānakāya, Sambhogkāya, Dharmakāya, robe Sublime.

The Nirmanakaya body is the “Body of Light” as described in Book 4, Part III. But it is to be considered as having been developed to the highest point possible that is compatible with incarnation.

The Sambhogkaya has “three perfections” added, so-called. These would prevent incarnation.

The Dharmakaya body is what may be described as the final sublimation of an individual. It is a bodiless flame on the point of mingling with the infinite flame. A description of the state of one who is in this body is given in “The Hermit of Æsopus Island.”

Such is a rough account of these “robes” according to Mme. Blavatsky. She further adds that the Dharmakaya body has to be renounced by anyone who wants to help humanity. Now, helping humanity is a very nice thing for those who like it, and no doubt those who do so deserve well of their fellows. But there is no reason whatever for imagining that to help humanity is the only kind of work worth doing in this universe. The feeling o desire to do so is a limitation and a drag just as bad as any other and it is not at ah necessary to make all this fuss about Initiator and ah the rest of it. The universe is exceedingly elastic, especially for those who are themselves elastic. Therefore, though o. course one cannot remember humanity when one is wearing the Dharmakaya body, one can hang the Dharamakaya body in one’s magical wardrobe, with a few camphor-balls to keep the moths out, and put it on from time to time when feeling in need of refreshment. In fact, one who is helping humanity is constantly in need of a wash and brush-up from time to time. There i5 nothing quite so contaminating as humanity, especially Theosophists, as Mme. Blavatsky herself discovered. But the best of all illustrations is death, in which ah things unessential to progress are burned up. The plan is much better than that of the Elixir of Life. It is perfectly ah right to use this Elixir for energy and youth, but despite all, impressions keep on cluttering up the mind, and once in a while it is certainly a splendid thing for everybody to have the Spring Cleaning of death.

With regard to one’s purpose in doing anything at ahi, it depends on the nature of one’s Star. Blavatsky was horribly hampered by the Trance of Sorrow. She could see nothing else in the world but helping humanity. She takes no notice whatever of the question of progress through other planets.

Geocentricity is a very pathetic and amusingly childish characteristic of the older schools. They are always talking about the ten thousand worlds, but it is only a figure of speech. They do not believe in them as actual realities. It is one of the regular Oriental tricks to exaggerate all sorts of things in order to impress other people with one’s knowledge, and then to forget altogether to weld this particular piece of information on to the wheel of the Law. Consequently, ah Blavatsky’s talk about the sublimity of the Nirmanakaya body is no more than the speech of a politician who is thanking a famous general for having done some of his dirty work for him.

39. The Shangna robe, ‘tis true, can purchase hight eternal. The Shangna robe alone gives the Nirvāna of destruction; it stops rebirth, but, O Lanoo, it also kills—compassion. No longer can the perfect Buddhas, who don the Dharmakāya glory, help man’s salvation. Alas! shall SELVES be sacrificed to Self, mankind, unto the weal of Units?

The sum of misery is diminished only in a minute degree by the attainment of a pratyeka-buddha. The tremendous energy acquired is used to accomplish the miracle of destruction. If the keystone of an arch is taken away the other stones are not promoted to a higher place. They fall. [A Pratykeka-Buddha is one who attains emancipation for himself alone.—Ed.]

(“Nirvana of destruction”! Nirvana means ‘cessation’. What messy English!)

40. Know, O beginner, this is the Open PATH, the way to selfish bliss, shunned by the Bodhisattvas of the “Secret Heart,” the Buddhas of Compassion.

The words “selfish bliss” must not be taken in a literal sense. It is exceedingly difficult to discuss this question. The Occidental mind finds it difficult even to attach any meaning to the conditions of Nirvāna. Partly it is the fault of language, partly it is due to the fact that the condition of Arhan is quite beyond thought. He is beyond the Abyss, and there a thing is only true in so far as it is self-contradictory. The Arhan has no self to be blissful. It is much simpler to consider it on the lines given in my commentary to the last verse.

41. To live to benefit mankind is the first step. To practice the six glorious virtues is the second.

42. To don Nirmānakāya’s humble robe is to forego eternal bliss for Self, to help on man’s salvation. To reach Nirvana’s bliss but to renounce it, is the supreme, the final step—the highest on Renunciation’s Path.