At this point it will be well, both for the sake of greater clearness and of giving credit where credit is due, to give some account of the method of collecting the material for the Dictionary and of the work done by the voluntary readers and sub-editors. Each member of these two classes stood to the final editors in a relation similar to that which Socrates in the Ion compares to the magnet and the suspended rings, each depending on and operating through the other, although in the case of the Dictionary the order of their sequence was reversed.

The example of Johnson and Richardson had shown clearly that the citation of authority for a word was one of the essentials for establishing its meaning and tracing its history. It was therefore obvious that the first step towards the building up of a new dictionary must be the assembling of such authority, in the form of quotations from English writings throughout the various periods of the language. Johnson and Richardson had been selective in the material they assembled, and obviously some kind of selection would be imposed by practical limits, however wide the actual range might be. This was a point on which control was difficult; the one safeguard was that the care and judgement of some readers would make up for the possible deficiencies of others.

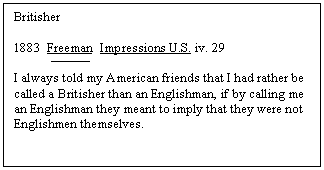

By the directions which were issued to intending readers in 1858, and again in 1879, uniformity in the methods of presenting the quotations was attained. Each was written on a separate slip of paper, at first of the size of a half-sheet of note-paper, latterly of a quarter of a sheet of foolscap, except when readers who supplied their own paper (such as Dr Furnivall, Dr Fitzedward Hall, and the Revd W. B. R. Wilson) wrote on pieces of any size or quality that came to hand. This difference in size makes it easy to distinguish the slips belonging to the two periods of collecting. When completed, the normal slip presented three things, (1) the word for which it was selected, written in the upper left-hand corner, (2) the date, author, title, page, etc., of the work cited, and (3) the quotation itself, either in full, or in an adequate form. A typical slip therefore presented something like the following appearance:

To obviate the tedium of repeating item (2) over and over again on hundreds of slips, it was in a large number of instances printed on each, in accordance with an estimate of the number that would be required for the particular book, or was supplied by stamping after the quotations themselves had been written. In this way, too, it was easier to make the references to page, chapter, line, etc., conform to general rules.

How the readers were to be guided in their selection of words was thus explained in the directions issued in 1879:

Make a quotation for every word that strikes you as rare, obsolete, old-fashioned, new, peculiar, or used in a peculiar way.

Take special note of passages which show or imply that a word is either new and tentative, or needing explanation as obsolete or archaic, and which thus help to fix the date of its introduction or disuse.

Make as many quotations as you can for ordinary words, especially when they are used significantly, and tend by the context to explain or suggest their own meaning.

It is obvious that these rules would apply in very varying degrees to different books, and that the task of some readers would be much more difficult and extensive than that of others in books of the same size. The amount undertaken or done by the different readers also varied enormously. In both periods of collecting there were a number who were marvels of industry and whose mark is plain on almost every page of the Dictionary to those who can recognize it. With these on the one hand, and the large army of lesser, but often important, contributors on the other, it is not surprising that the piles of quotations grew into the interminable series that filled to overflowing the pigeon-holes of the Scriptorium. How rapidly the material increased in the periods of greatest activity will best be realized by a few of the passages relating to this phase of the work. In May 1879, in response to the appeal issued at the end of April, ‘165 readers have offered themselves, 128 of these have chosen their books, been supplied with slips, and are now at work for us. The number of books actually undertaken and entered against readers is 234; arrangements are in progress for perhaps as many more.’ A year later the number of readers had risen to 754. ‘Altogether 1,568 books have been undertaken, of which 924 have been finished’, and ‘the total number of printed slips supplied to readers now amounts to 625,035, while the quotations returned are 361,670’. Of these readers some had sent in a large number of slips varying from 4,500 to 11,000. By another year (1881) ‘the number of readers has now risen to upwards of 800, of whom 510 are still at work. The slips issued now number 817,625, and the quotations returned 656,900.’ The total number of authors then represented in the Reference Index was 2,700, and the titles numbered some 4,500.

Many of the particulars of this remarkable activity were given in the preface to the first volume of the Dictionary, and a full list of the readers and the books read by them between 1879 and 1884, with the approximate number of quotations supplied by each, forms an appendix of 32 pages to the Presidential Address for 1884 (pp. 101-42).

On looking over this list, the observant reader will notice that the interest in the Dictionary which at its first beginning had been manifested in the United States had been maintained, though not on the lines suggested by Coleridge. The interest, and the results it produced, are specially referred to by Dr Murray in his Presidential Address for 1880 in these words:

In connexion with the Reading, I cannot sufficiently express my appreciation of the kindness of our friends in the United States, where the interest taken in our scheme, springing from a genuine love of our common language, its history, and a warm desire to make the Dictionary worthy of that language, has impressed me very deeply. I do not hesitate to say that I find in Americans an ideal love for the English language as a glorious heritage, and a pride in being intimate with its grand memories, such as one does find sometimes in a classical scholar in regard to Greek, but which is rare indeed in Englishmen towards their own tongue; and from this I draw the most certain inferences as to the lead which Americans must at no distant date take in English scholarship.

Dr Murray then specially refers to the services rendered by Prof. Francis A. March of Lafayette College in directing the reading done in the United States at that time, and adds:

There is another feature of American help to which I must allude, because it contrasts with that we have obtained in England - I refer to that offered to the Dictionary by men of Academic standing in the States. The number of Professors in American Universities and Colleges included among our readers is very large; and in several instances a professor has put himself down for a dozen works, which he has undertaken to read personally, and with the help of his students. We have had no such help from any college or university in Great Britain; only one or two Professors of English in this country have thought the matter of sufficient importance to talk to their students about it, and advise them to help us.

By far the greater part of the material supplied by these American readers, it may be noted, was of the same type as that furnished by the British contributors, that is, it was mainly drawn from literary or scientific works written in standard English, or without noticeable American features in vocabulary or idiom. It was thus very serviceable in supplementing the English evidence, but failed to a very large extent to bring out the special developments of the language in the American colonies and the United States. Much of the material for these was specially supplied during the progress of the Dictionary by one or two workers, notably by Mr Albert Matthews of Boston.

In addition to the quotations supplied by all this new reading, a few collections of Dictionary material, which had already been made by various persons, were by them generously handed over for use in the new work. If the Dictionary as it stands is a monument of scholarship, it is also one of unselfish giving on the part of a great number of men and women whose nameless contributions form the foundation of almost every article it contains.

Only second in value to the work done by the voluntary readers was that of the volunteer sub-editors. Without these, the mere handling and reducing to alphabetical order of three and a half millions of slips would have formed a task sufficiently heavy to delay for some years the actual preparation of the Dictionary. Even those who did no more than this rendered good service, but most of them went much farther, and so arranged and subdivided the words they dealt with, and defined their various senses, that their work was of real value in the final editing. It is with good reason, therefore, that the portions done by each were carefully recorded in the various reports on the Dictionary presented to the Philological Society and in the Preface to each letter in the Dictionary itself.

|

|

|