|

John Day Fossil Beds Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Six:

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT (continued)

Cattle Ranching

In the years 1862-1922, settlers steadily pushed into Grant and Wheeler counties. While the initial lure was gold, grasslands provided the more enduring attraction. The rugged upper John Day watershed possessed both fertile bottomlands along the river and its tributary streams as well as upland areas of abundant bluebunch wheatgrass. The nutritious grass proved an irresistible draw to raisers of cattle, horses, and sheep. As stockmen realized the potentials of the interior of the Pacific Northwest, they rushed in to secure lands and place their herds. J. Orin Oliphant, historian of the "Rise of Transcascadia," described a grazing province of some 16,000 square miles in central and eastern Oregon. "Here, on uplands and lowlands, on grasslands and sagelands," wrote Oliphant, "cattle in large numbers roamed freely the year round in scattered districts of a cattlemen's kingdom which flourished during the 1870's and much of the 1880's" (Oliphant 1968: 75-76).

Initially, cattle to feed hungry miners were brought from west of the Cascade Mountains. In 1862 alone, 46,000 head were imported from west of the mountains, as compared to an estimated 7,000 head of cattle entering the region with overland emigrants from the east. This build up of herds was in direct response to the local mining market, the seemingly inexhaustible grasslands, and the opportunity to use the Homestead Act (1862) or the cash entry purchase system secure to key range lands and water sources (Oliphant 1968: 79).

Early cattle ranchers in Grant and Wheeler counties took advantage of the luxurious, stirrup-high bunch grasses. Their rangy herds grazed uncontrolled throughout the year on the vast, unfenced ranges of the public domain, on rocky hillsides and in mountain forests. Large cattle holdings in Wheeler County in the early years included those of the Gilman & French Company with 38,120 acres; the Sophiana Ranch with 10,095 acres; and the Butte Creek Land, Livestock & Lumber Company with 8,634 acres. The Gilman & French holdings included Henry Wheeler's homestead, the Corn Cob Ranch, six miles north and west of Spray. From 1872 through 1902, the Gilman brothers and the French brothers also acquired the Prairie Ranch, the Hoyt Ranch, the Sutton Ranch, the O.K. Ranch, and various Wheeler County parcels needed to control most of the land in between. All of these places were well capitalized and famous for their large barns, extensive fences, early indoor plumbing and electrical systems, and productive hay and grain fields (Shaver et al. 1905: 657; Stinchfield 1983: 28-30).

In Grant County in 1885, vast cattle ranches included Todhunter & Devine's White Horse Ranch with 40,000 cattle, and French & Glenn's "P" Ranch, with 30,000 cattle. The Bear Valley, Silvies Valley, Juniper, Crane Creek, Otis, Murderer's Creek, and Paulina valleys were all monopolized by cattlemen.

This stranglehold over some of the best meadowlands and water sources was decried by the region's champions of economic development. The periodical West Shore proclaimed in 1885:

When . . .these numerous valleys are wrested from the grip of the cattle kings and divided up into homesteads for actual settlers; when they are made to yield the diversified products of which they are capable; when the numerous farmers shall utilize the adjacent hills for the grazing of as many cattle, sheep, etc. as each can properly care for; then the school house shall replace the cowboy's nut and the settler's cabin shall be seen in every nook and corner of these vacant valleys, then the country will multiply its population and wealth, and the era of its real prosperity will dawn (Anonymous 1902: 399).

In the early 1880s, many of the larger cattle operations in northern and central Oregon did in fact begin moving or selling their herds into the Harney Basin to the south. There they discovered the lush, wide-open meadows of that watershed, and began to push for the closure of the Malheur Indian Reservation. In Grant and Wheeler counties, sheep raising gained a firm foothold in the local economy, in the same decade (Anonymous 1902: 394).

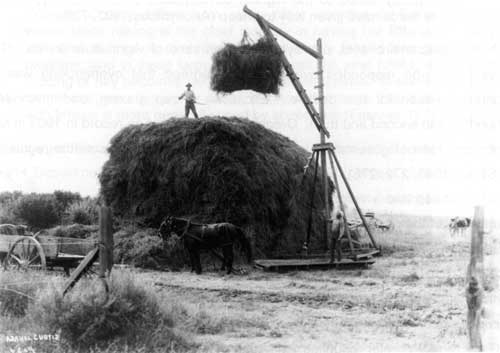

By 1890, after a five-year drop in cattle prices from a peak in 1885, and an especially severe winter in which ranchers suffered heavy losses, cattlemen began gradually to consider the advisability of providing their herds with winter feed (Strong 1940: 262). Alfalfa hay and grains to supplement winter feed could be successfully grown on irrigated bottomlands of the John Day and its tributary creeks. The harvested fields made excellent fall pasture for the herds. This combination of livestock raising and limited agriculture created a healthy economic mix that persisted in both Grant and Wheeler counties into the twentieth century (Fussner 1975: 86).

Fig. 43. Hay stacking in eastern Oregon

(Photograph by Asahel Curtis) (OrHi 54200).

Several factors, nonetheless, worked to further erode the survival of the cattle industry in Grant and Wheeler counties in the later years of the nineteenth century and early decades of the twentieth. Overgrazing of the range, the competition of the sheep industry, and homesteading were its chief challenges. As these challenges were met, the open range cattle business was transformed into the modern fenced range industry that persists today (Strong 1940: 258)

As early as the 1880s, the range was beginning to show signs of lower production due to overgrazing. Grant County recognized the effect this was having on its cattle industry in 1902:

Stock raising has been in the past and must continue to be a leading pursuit. At one time the stockman's investments were almost entirely in cattle, but in recent years the range has not furnished grass in quantity and quality suited to the highest development of this industry, and the cattle herds have given way to sheep (Anonymous 1902: 728).

In a questionnaire sent out by the Department of Agriculture in ca. 1905, cattlemen who responded overwhelmingly agreed that overstocking was the primary reason for this decline. Excessive sheep grazing, and methods of handling ran second and third. Oregon cattlemen went on record in 1903 in favor of some form of government control of the range under reasonable regulations (Strong 1940: 272, 276).

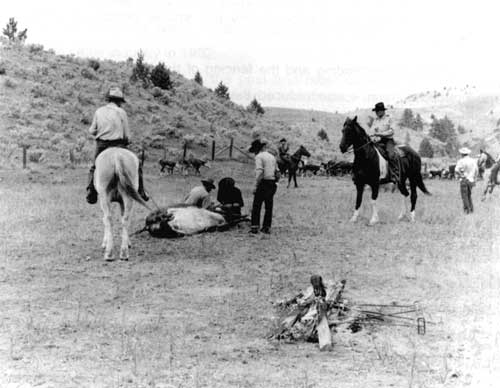

Sheep had a notably more destructive effect on range grass than cattle, because of the plants they ate, their close cropping of forage, and the damage of their restless hooves as they stood close together in the heat of the day (Strong 1940: 275). As available range land diminished, the competition for access to it pitted cattle families against sheep families, and ranchers against homesteaders in what became commonly known as the "range wars." There was violence in Grant and Wheeler counties, although it was mostly against animals and property. in 1895, the Fossil Journal reported that "a sheep-hater burns 600 tons of hay on three farms near Mitchell." The Wheeler County News ran an account on May 27, 1904:

Poison was deposited in the range 8 miles east from town a short distance from the Canyon city road and the result of this cowardly act is that 12 head of range cattle belonging to Sigfrit Brothers dies last week.... Following the poisoning episode came the news to town early Monday morning that about 3 a.m. five men attacked the band of yearling sheep in the corral on the place belonging to Butler Brothers of Richmond. 106 sheep were killed and a great number were so wounded as to either die or have to be killed. These sheep were being grazed on leased land, and no motive can be found why this should occur.... (Fussner 1975: 93-94).

General homesteading and the fencing of the land — sometimes illegally on the public domain — also reduced the acreage available for running range cattle. The Oregonian noted in 1903:

Wheeler County differs from many other counties in Eastern Oregon where stock raising is the chief industry in having but little public range. Hills and valleys on every hand are generally fenced into great private pastures, and in these large herds are kept the year round, although the feeding of hay becomes necessary in the wintertime. In earlier times, the range was used largely for cattle, but now the range that is not enclosed with fences is more generally used by sheepmen (Fussner 1975: 94-95).

The Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909 encouraged further settlement in the area. A 1914 Department of Agriculture survey noted that 20 percent of range land in central, south-central, and southeastern Oregon had been homesteaded since 1910. The narrow, watered valleys of Grant and Wheeler counties offered conditions conducive to agriculture. As a result, Grant County witnessed a 33 1/2 percent decrease in cattle because of homesteading in the decade from 1904 to 1914, and Wheeler County saw a 60 percent decrease in cattle during that same period (Strong 1940: 261). Passage of the Stock Raising Homestead Act (1916), which allowed filing on up to one square mile of land, and the return of veterans following World War I who filed under that law, sped up the pace of homesteading on lands around the Monument, and put still more range lands under fence (Humphreys 1984a: 2).

Fig. 44. Branding cattle in the John Day

watershed, n d (OrHi 99078, ODOT 4172).

The first steps taken to regulate the use of range lands came about indirectly through the establishment of national forest reserves. In Oregon, the earliest of these was the Cascade Forest Reserve, created by executive proclamation in 1893, comprising 4,490,800 acres and running from the Columbia River almost to the California line. The Blue Mountain Forest Reserve was created in 1906. Later it was subdivided into National Forests that now include Malheur, Umatilla, and Ochoco, part of each of these lying in Grant and Wheeler counties. Grazing by both cattle and sheep was allowed but controlled within the bounds of the forest reserves, where the region's high summer ranges were found. In the year 1900, permits for grazing became required, and starting in January of 1906, fees per head were charged. The fees were low at first — 18 cents per animal per season in 1911 — but increased in increments over the years. In return for the fees, cattlemen had access to carefully controlled summer ranges, parceled out through an allotment system, and scientifically managed to prevent depletion from overgrazing. Although cattlemen had initially opposed the creation of the forest reserves, by 1924 there was a general feeling that the Forest Service was successfully increasing the carrying capacity of the summer ranges (Strong 267-269).

A second important step toward regulation of range lands and a critical one in sustaining the cattle industry in Oregon, was passage of the Taylor Grazing Act of 1935. This piece of legislation affected 80,000,000 acres of the public domain in the West, eliminating all uncontrolled grazing. Thousands of acres of spring and fall range lands in Grant and Wheeler counties became subject to annual permits and fees. The Act specified that a high percentage of fees collected would be funneled back into communities for range improvements through local grazing districts (Strong 1940: 276-277).

The Depression and World War Two combined to swing the economic pendulum from sheep back to cattle ranching in central Oregon. The influx of homesteaders in the inter-war years, increased competition for range lands, falling prices, and labor shortages combined to make sheep ranching less profitable than cattle ranching. Many local ranchers, like the James Cant family and the Rhys Humphreys family, sold their sheep and switched to cattle in the years just before and just after World War Two (Taylor and Gilbert 1996: 39-40; Humphreys 1984a: 2-3).

Managing a cattle ranch in the middle years of the twentieth century was an increasingly complex enterprise. Herman Oliver wrote of his highly successful cattle operations near the town of John Day:

There isn't any system of ranch management, such as systems of bookkeeping. You can't say, "now do this and this and this and you will succeed." Management is thousands of little things, all tied together. Grass, hay, cows, water, weather, fences, calves, bulls, steers, markets, breeding, health, corrals — all these things must fit together like a machine. Any one of them, out of kilter, can cause the owner to lose his shirt (Oliver 1961: 108).

Fig. 45. View of the Oliver Ranch south

of John Day, n.d. (OrHi 100406).

Like the Cant Ranch, the Oliver Ranch required constant upkeep and repair. The Olivers routinely ended each year with planning for the next. They classified and inventoried all livestock, measured the hay and grain to determine if they had enough, estimated next year's sales, laid out the year's fencing and ditching program, inspected corrals and gates, mended fences, and repaired buildings. The Oliver's home ranch had thirteen buildings, "all exactly square with each other and all in good repair. We thought this helped in giving buyers a good first impression." Herman Oliver, like most cattle ranchers, was jack of all trades — a rough carpenter, blacksmith, machine repairman, and harness worker (Oliver 1961: 120)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/hrs6a.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002