|

John Day Fossil Beds Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Four:

SETTLEMENT (continued)

Cultural Resources Summary

Because of its isolation, some corners of the John Day basin witnessed a period of subsistence-level settlement that lasted from the early 1860s to the turn of the century and beyond. Early ranching and farming activities altered the landscape, and left a pattern of physical imprints on the land different from that imposed by native peoples. Cultural resources associated with settlement in the area are not limited to buildings and structures, but will likely include more ephemeral remnants such as ornamental vegetation, irrigation system features, and abandoned farming equipment.

Homesteads in the vicinity of the Monument clung to the bottomlands of the river and its tributary streams where water was available for domestic and agricultural purposes. On individual homesteads, rudimentary wood structures and corrals clustered near natural springs and native groves of black cottonwoods. The farmsteads were oriented for maximum protection from sun and winter storms.

Arable land was limited to the narrow river plain. Settlers broke the land for cultivation, first in a limited way with gardens, orchards, and shade trees, and later with fields of grain or hay to supplement the feeding of livestock. Irrigation was a necessity in the semi-arid climate. Settlers built hand-dug ditches — main lines and laterals — providing gravity feed systems that served the long, linear fields along the river corridor. The early settlers of John Day primarily ran cattle and sheep operations, so the physical impact of each family's presence extended to range lands miles from the homestead's headquarters. By 1900, native bunch grasses had largely disappeared due to overgrazing, and cheatgrass and other weeds grew in its place. Increasingly, fencing segmented the open range (Strong 1940: 274).

Fig. 20. Original T.B. Hoover Cabin on

Hoover Creek, vicinity of Fossil, 1927 (Courtesy Fossil

Museum)

Only one cultural resource within the boundaries of the Monument (or within all of Grant and Wheeler counties) associated with the theme of settlement is listed in the National Register of Historic Places:

The Cant Ranch, established as the Officer Homestead ca. 1890.Oregon State Inventory of Historic Places listings from Grant and Wheeler counties (encompassing listings in both Umatilla and Malheur National Forests)

Oregon State Inventory of Historic Places listings from Grant and Wheeler counties (encompassing listings in both Umatilla and Malheur National Forests) include the following examples of rural settlement:

The Oliver Ranch, established 1880 in the Canyon City area.

Mountain Creek School, built 1910 in the vicinity of Mitchell.

Chess Wooden Homestead Cabin, ca. 1880, Mitchell vicinity.

"Mountain Ranch" House and Barn, built Ca. 1870s, 1880s, in the Mitchell area.

Howard-McGee House, built ca. 1890 in the Mitchell area

Lower Pine Creek School, built ca. 1900 in the Clarno area, now moved into the town of Fossil

Joaquin Miller Cabin, dating from 1865, now part of the Grant County Historic Museum complex at Canyon City

Henry H. Wheeler Landmark, erected in the 1920s in the Mitchell vicinity

Lovlett Corral, from ca. 1900, in the Umatilla National Forest in northeastern Grant County

Princess Cabin, Buck Bulch Cabin. Rapp Cabin, dating from 1902 — 1920s, all in Umatilla National Forest

Lyons Ranch, dating from the 1920s, Malheur National Forest in southeastern Grant County

Kight Cabin, Snow Cabin, Still Cabin, Blue Bird Cabin, and Brown Bear Cabin, dating from 1900 — 1926, all in the Malheur National Forest

Area tourism literature listings for places associated with early settlement, in addition to places identified above, include:

Old Red Barn, built 1883, on U.S. Hwy. 26 outside Mt. Vernon

Julia Henderson Pioneer Park, site of the annual Eastern Oregon Pioneer Picnic (dating from 1899), on SR 19 between Fossil and Service Creek

The Cant Ranch remains the most intact example of homestead settlement followed by sustained sheep and cattle ranching, inside the boundaries of the Monument. The National Park Service purchased 878 acres of the ranch in 1975 to expand the Sheep Rock Unit (Cant and Cant 1984; Steber 1984). Recognizing the significance of the property to the Monument's cultural history, the Park Service nominated the 200-acre Cant Ranch Historic District to the National Register in 1983 (Toothman 1983). The district has since been more broadly assessed as a cultural landscape, and encompasses twenty-four contributing resources — eleven buildings, five structures, and eight sites, including agricultural fields along the river (Taylor and Gilbert 1996). Now serving as headquarters for the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, the Cant Ranch is also the focal point of the Monument's cultural resource interpretive program.

BLM records indicate that a handful of other homesteaders settled, if only temporarily, within the present-day boundaries of Sheep Rock, Painted Hills, and Clarno. Yet no evidence has arisen to suggest that any other significant homesteads survive on National Park Service-owned lands within the Monument. Probable locations for settlement along the river and streams are well-known and well-traveled. Park Service staff interviewed early in this project knew of no other standing homestead-era structures on Monument land (Hammett, Cahill, Fremd 1996). Burtchard, Cheung, and Gleason's archaeological reconnaissance of 1993 located nothing of significance in terms of homestead remnants. An identified historic enclosure in Sheep Rock turned out to be a part of the Cant Ranch. Sheepherder Springs Site, which includes a cabin, was identified in the survey on private land north of the Clarno (Burtchard, Cheung and Gleason 1998).

No comprehensive field survey of extant historic resources has ever been conducted in Grant or Wheeler counties. And yet, secondary sources are replete with names of early pioneers who settled in the nooks and crannies of the John Day country. There are likely to be extant historic properties associated with settlement in the larger area around the Monument, and there are undoubtedly historic archaeological sites and scatters to mark the locations of failed homesteads.

Some ranchers succeeded and remained on the land, reusing, adapting, moving, and remodeling early homestead structures over the years. Such 'evolutionary" ranches may not have the obvious integrity of the Cant Ranch, but will reflect layers of continued use over time. An example is the Mascall Ranch, at the head of Picture Gorge in Sheep Rock, where successive generations of the Mascall family have raised sheep and cattle since 1874 (Mascall 1939). Another is Burnt Ranch, five miles north of the Painted Hills at the mouth of Bridge Creek, homestead of James N. Clark, stage stop on The Dalles Military Road, and site of a well-known raid by Paiute Indians in 1865 (Fussner 1975: 23-24).

Other property types in addition to homesteads reflect the era of early settlement. The site of Camp Watson relates to government efforts to wrest the land from native inhabitants, opening the door to settlement. Situated near the former village of Antone on an old, unimproved stretch of The Dalles Military Road southeast of Mitchell, its precise location on the ground has been lost in recent decades. In 1932, local American Legion posts sponsored a dedication and placements of marble grave markers at the camp cemetery. In 1957, historian Judith Keyes Kenney easily located the site:

Today, the site of Camp Watson, about five miles west of Anatone [sic], is easily accessible from the Mitchell-John Day highway. Fort Creek still flows, though nothing else remains to be seen but marble markers in the cemetery, overgrown with pine. It lays on the western hill, with the markers placed in a row.. (Kenney 1957: 15-16).

In November of 1958, the National Park Service entered the site of Camp Watson on the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings, under the theme of Westward Migration (Military and Indian Affairs). At that time, the field surveyor was unsuccessful in re-locating the site (Everhart 1958).

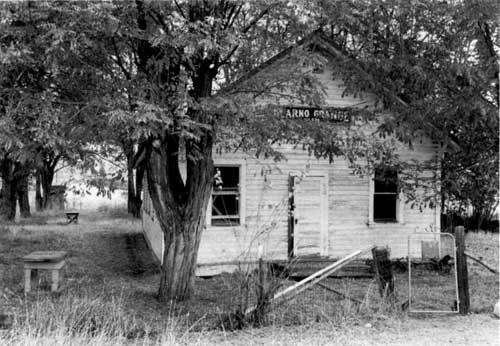

Family cemeteries such as the Clarno and Carroll family plots are mentioned in secondary literature. There are likely to be more of these on remote knolls and hillsides. This is affirmed by entries in the Oregon Cemetery Survey (conducted 1978) for fifteen pioneer cemeteries in Wheeler County and thirty-five cemeteries in Grant County (OR DOT 1978). Other rural crossroads structures associated with early settlement, such as the grange hall at Clarno, have yet to be inventoried by the State of Oregon or by the respective counties.

Fig. 21. The Clarno Grange, adjacent to

the SR 218 bridge at Clarno. F.K. Lentz, 1996 (National Park

Service)

Several suggestions are made for further investigation of cultural resources associated with the context of Settlement:

Conduct a historic resource survey/inventory of ranch inholdings within the Monument. Not specified within the scope of this historic resource study, a comprehensive, property by property field survey of inholdings would provide a stronger comparative basis for the interpretation of the Cant Ranch. Permission to access private lands, and the cooperation of private owners would be required. Such a survey could yield information about "evolutionary" ranches in the era, where the continued use and adaptation of the ranch complex to the present time has made historic character less visible.

Expand the excellent oral history program conducted in the Sheep Rock Unit to the Painted Hills and Clarno units.

Update the November, 1958 National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings listing of Camp Watson, through field verification of the fort site and cemetery.

Ascertain locations of any pioneer cemeteries (beginning with the Clarno and Carroll family plots) in the vicinity of the Clarno, Painted Hills, or Sheep Rock units. Work with property owners adjacent to and/or within the bounds of the Monument to ensure the preservation and security of pioneer cemeteries in the area.

Encourage and/or partner with the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office to conduct professional survey/inventory of historic properties in Grant and Wheeler counties. Current survey data is out-of-date, unsubstantiated, and terribly incomplete. Updated survey would provide much-needed site-specific data to enliven the broad themes outlined in this report, thus increasing the interpretive knowledge base at the Monument.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/hrs4i.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002