|

John Day Fossil Beds Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Two:

EARLY EXPLORATIONS AND EXPEDITIONS (continued)

Fur Trade Explorations

In 1821 the Hudson's Bay Company succeeded to the interests of the North West Company in the Pacific Northwest. George Simpson, governor of its operations in North America, visited the Columbia watershed in 1824 and laid plans to strengthen British control of the fur trade. Simpson moved the regional headquarters from Astoria to a new post, Fort Vancouver, situated on the north bank of the Columbia near its confluence with the Willamette River. He was also made aware of the steady westward advance of Americans and the real prospect they would soon press beyond the Rocky Mountains. Sensing the potential of the Snake River watershed, he wrote:

If properly managed no question exists that it would yield handsome profits as we have convincing proof that the Country is a rich preserve of Beaver and which for political reasons we should endeavor to destroy as fast as possible (Rich and Johnson 1950: xlii).

Simpson's strategy was to dispatch a succession of brigades into the watershed of the Snake River and to trap out its fur-bearing animals. His plan would bring economic returns to the company in the shorter term and create a region so devoid of small mammals that the Americans, once they crossed the mountains and entered the region, would turn back in frustration. Peter Skene Ogden drew the primary assignment to execute the policy. Ogden's travels in connection with this assignment made him the first Euro-American to enter and explore the John Day basin.

Ogden's first expedition into the Snake country occurred between December, 1824, and October, 1825. At Fort Nez Perces on the Columbia River at the mouth of the Walla Walla, Ogden outfitted a return brigade. Throughout the fur trade era, Fort Nez Perces (subsequently known as Fort Walla Walla) was a center of influence among Sahaptin-speakers and Northern Paiute of the Columbia Plateau. Alexander Ross and Donald Mckenzie of the North West Company had built the post in 1818 at the junction of the Walla Walla and Columbia rivers just east of Wallula Gap. Constructed originally of timber, the post burned in 1841 but was reconstructed of adobe and continued in use into the era of overland emigration. During the fur trade, the post was singularly significant as an administrative center for the great "horse farm" operated by the Hudson's Bay Company. Horses for the brigades were supplied from the herds at Fort Nez Perces. It also was an important depot for trade goods flowing into the lives of Native Americans who resided in the region (Stern 1993, 1996).

Fig. 5. Fort Nez Perces (Walla Walla) at

the confluence of the Walla Walla and Columbia rivers, 1855. (OrHi

1651).

Peter Skene Ogden departed Fort Nez Perces on November 21, 1825, proceeding west across the Columbia Plateau to The Dalles. He and his brigade then ascended Fifteen Mile Creek, crossed to the Deschutes watershed, ascended the Crooked River, and then dropped into the watershed of the South Fork of the John day where the party camped on January 11, 1826, Ogden wrote:

... the country we came over this day well wooded with Norway Pine & also a tree strongly resembling the Box wood and altho I may be mistaken it greatly resembles it — the Soil good but stoney we had for part of the day about three inches of Snow distance this day 15 miles 3 Beavers (Rich and Johnson 1950: 113).

Ogden's party had success, taking 265 beaver and nine otter in the Deschutes watershed, but found icy conditions and near starvation on the John Day. On January 14, south of present Dayville, Ogden wrote:

We started early our course W and by N. for three miles and then North 6 miles along the main Branch of Deys River a fine large Stream — nearly as wide again as it is at the entrance of the Columbia and from appearance this river as well as the River of the Falls [Deschutes] also Utalla [Umatilla] take their sources from nearly the same quarter consequently the two first are very long from the winding course they take and from appearances Deys River must have been well stocked in Beaver — but all along our route this day we found Snake Huts [i.e., Northern Paiute lodges] not long since abandoned and from appearances have been killing Beaver from their want of Traps they destroy not many but the remainder become so shy that it is very difficult to take them . . . (Rich and Johnson 1950: 114).

Ogden's brigade entered the main valley of the John Day on January 17. He and his men remained for several days, catching both beaver and otter but coping with high water and loss of their traps. They discovered the beaver were shy or spooked because the Indians had raided the beaver dams and lodges in an attempt to kill the animals to secure pelts for trading at Fort Nez Perces. Ogden found "Snake" (probably Northern Paiute) Indians along the upper John Day. On January 19, for example, he noted:

Early this morning five Snake Indians paid us a visit they traded 6 Large and 2 small Beavers for Knives & Beads and 10 Beavers they traded with my Guide for a Horse I treated them kindly and made a trifling present to an Old man who accompanied them and as far as I could Judge from appearances they appear'd to respect, they were fine tall Men and well Dress'd, and for so barren a Country in good condition (Rich and Johnson 1950: 117).

The privations this party endured were many: hunger, ice, and uncertainty about its route. At the base of the Blue Mountains, where Ogden was about to commence a difficult crossing to Burnt River, he reflected: "we shall leave the waters of Dey's River and I have to remark altho we have taken some Beaver a poorer Country does not exist in any part of the World . . . (Rich and Johnson 1950: 119).

Ogden's men had trapped 185 beaver and sixteen otter along the John Day. His 1825-26 brigade took him as far east as Fort Hall. He then turned westward, working down the south bank of the Snake, exploring the Bruneau River, and finally ascending Burnt River to retrace his party's January trip through the upper John Day River region. He reached the John Day again on July 1 but did not tarry. On July 3 the expedition ascended the hills to the west to the Crooked River. Ogden guided his party on to the Deschutes, crossed the Cascade Range, and then passed through the Willamette Valley to arrive at Fort Vancouver in mid-July (Rich and Johnson 1950: 196-197).

Peter Skene Ogden led Hudson's Bay Company employees through the upper John Day watershed a second time in early July, 1829. This time his brigade moved northward from the Harney Basin up the Silvies River and over the Strawberry Mountains. In the vicinity of Dayville, the trappers found both elk and black-tail deer; the hunters killed six of the latter. Ogden continued on, arriving at what was probably the entrance to Picture Gorge: "Having reached the main stream we proceeded on following it down for six miles, when our progress was again arrested by high and lofty rocks, and as far as the eye can reach it appears to be the same." The party stopped here near the south boundary of what is now the Sheep Rock unit of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument:

We encamped not wishing from the low state of our horses and from the gloomy prospect before us to advance further for this day, but tomorrow I shall make the attempt though I verily believe were it left optional with the trappers prefer to proceed on and pass by the Dalles. This route would lengthen our journey eight days and at this season the natives being most numerous both at the Falls and Dalles stand a chance of having our horses stolen. Thus situated I am determined to persevere by this river . . . (Williams et al. 1971:164).

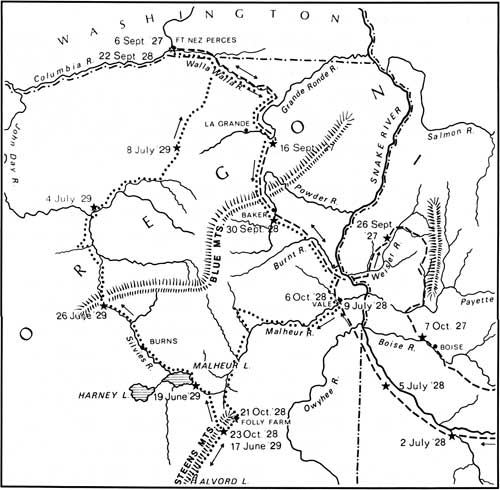

Fig. 6. Ogden's campsites in the John

Day watershed, June — July, 1829. Legend of expedition routes

1828-29; 1827-28 (Williams, Miller and Miller 1971: map).

Continuing downriver the next day, apparently having bypassed Picture Gorge, Ogden's party found a Northern Paiute camp "of fifty men with their families all busily employed with their salmon fisheries." In short order he bartered for fish and obtained two hundred salmon. Ogden wrestled with the vagaries of the men in the brigade:

Canadians are certainly strange beings — in the morning more curses were bestowed on me than a parson would bestow blessings in a month, and now they find themselves rich in food with a fair prospect of soon reaching the end of their journey I am in the opinion of all a clever fellow for coming this way. Such is the nature of the men I have to travel with in this barren country, and truly may it be remarked the reverse of being an enviable one, and if any man be of a different opinion let him make the experiment and he will soon be convinced (Williams et al. 1971: 164-165).

On July 4 Ogden's party reached the North Fork of the John Day at the present town of Kimberly, and was fortified by the purchase the previous day of twenty fresh salmon. He led his party up the North Fork for three days, then turned northward toward Fort Nez Perces, which they reached on July 9. "This ends my fifth trip to the Snake Country," he observed, "and so far as regards my party have no cause to complain of our success" (Williams et al. 1971: 165-166).

The journals of Peter Skene Ogden's two brigades of the 1820s, both of which entered the John Day watershed, confirm active use of the region by fur seekers and the presence of Northern Paiute Indians along the upper river. Although the Northern Paiute were culturally a Great Basin people, they were clearly engaged in the salmon fishery during Ogden's visit in the summer of 1829. Ogden also noted the presence of the Cayuse in the upper John Day region, observing what he described as the "remains of a Cayouse camp of last fall" and what he thought was the "Cayouse camp road" (Williams et al. 1971: 163-164).

Another Hudson's Bay Company brigade leader working in the Snake River watershed explored the John Day basin. John Work led his party north from Harney Basin via the Silvies River into the John Day valley in July of 1831. Work wrote: "Crossed the mountains to Day's River, a distance of 22 miles N. W. the road very hilly and steep, particularly the N. side of the mountain. The mountain is thickly wooded with tall pine timber." Work's men camped on the John Day River and bartered for five beaver pelts from two Indians. The next day the trappers traveled sixteen miles down the river to the vicinity of present Dayville. On July 12 Work wrote about his travels and an Indian fish weir:

. . . we stopped near a camp of Snake Indians who have the river barred for the purpose of catching salmon. We, with difficulty, obtained a few salmon from them, perhaps enough to give all hands a meal. They are taking very few salmon, and are complaining of being hungry themselves. No roots can be obtained from them, but some of the men traded two or three dogs, but even the few of these animals they have are very lean, a sure sign of a scarcity of food among Indians. We found two horses with these people who were stolen from the men I left on Snake River in September last. They gave up the horses without hesitation, and said they had received them from another band that are in the mountains with some more horses which were stolen at the same time . . . Part of the way today the road lay over rugged rocks on the banks of the river, and was very hard on the already wounded feet of the horses. Five beaver were taken in the morning (Elliott 1913: 311-312).

Work's men remained in camp on July 13 — weary and hungry, obtaining only three salmon from the famished Indians. "They complain of starving themselves," he noted. On July 14 the Hudson's Bay Company brigade traveled twenty-five miles down the John Day River and on July 15 continued another eight miles to the North Fork at Kimberly and ascended it for seven miles. "The road hilly and stony," he wrote. "These two days the people found great quantities of currants along the banks of the river." On July 16 the brigade continued another eight miles up the North Fork then cut across the mountains toward Fort Nez Perces (Elliott 1913: 312-313).

Work's brigade reached Fort Nez Perces on July 18. Two days later he described his ambitious expedition:

Since our spring journey commenced we have traveled upwards of 1000 miles, and from the height of the water and scarcity of beaver we have very little for the labour and trouble which we experienced. Previous to taking up our winter quarters last fall we traveled upwards of 980 miles, which, with the different moves made during the winter makes better than 2000 miles traveled during our voyage.

Work's brigade lost eighty-two horses by drowning, theft, death, or being killed for food (Elliott 1913: 314).

During the fur trade era, several scientists also entered the region and passed by the mouth of the John Day River. These included the botanist David Douglas and naturalist John Kirk Townsend. Douglas, a Scottish explorer in the employ of the Royal Horticultural Society of London, traveled up and down the Columbia on plant-collecting expeditions. He sought new ornamentals to introduce into European gardens. Townsend traveled overland in 1834 with Thomas Nuttall, a botanist from Harvard University. Both collected specimens and made notes on their observations. Townsend sold his duplicate bird and animal skins to John James Audubon who used them in his books on birds and mammals (McKelvey 1991: 299-341, 586-616).

Nathaniel Wyeth, an American fur trapper and company owner, explored the Deschutes watershed to the west of the John Day in 1835. An ice merchant who had prospered in Massachusetts, Wyeth sought to compete with the Hudson's Bay Company. He traveled overland to Oregon in 1832 to examine prospects, returned east in 1833, and formed the Columbia River Fishing and Trading Company. He dispatched supplies and personnel on the May Dacre, a vessel he planned to use for the export of salted salmon to Hawaii, and in 1834 returned to Oregon. His overland party of twenty included the naturalists Nuttall and Townsend as well as the Methodist missionary Jason Lee and his compatriots (Sampson 1 968[5]: 381-401).

Wyeth founded Fort William on Sauvies Island at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers and established a farm on French Prairie to grow vegetables and produce livestock for his employees. He personally concentrated on trapping south of the Columbia River in the watershed of the Deschutes River. Winter conditions, hunger, lack of knowledge of the terrain and survival techniques beleaguered the Wyeth party. Far up the Deschutes in January, 1835, camping amid snowdrifts three feet deep, he penned a lamentation in his journal:

The thoughts that have run through my brain while I have been lying here in the snow would fill a volume and of such matter as was never put into one, my infancy, my youth, and its friends and faults, my manhoods troubled stream, its vagaries, its aloes mixed with the gall of bitterness and its results viz under a blankett hundreds perhaps thousands of miles from a friend, the Blast howling about, and smothered in snow, poor, in debt, doing nothing to get out of it, despised for a visionary, nearly naked, but there is one good thing plenty to eat health and heart (Young 1899: 241-243).

Wyeth, a man of many interests, recorded the first geological comments on Oregon east of the Cascades. On February 6, 1836, on the Deschutes, he noted:

. . . the upper part of the mountain was of mica slate very much twisted this afternoon the rock was volcanic and in some places underlaid with green clay Saw today small bolders of a blackrock which from its fracture I took to be bituminous coal but its weight was about that of hornblende perhaps it might be Obsidian but I think was heavier than any I have ever seen (Young 1899: 249).

A fortune in furs and salmon slipped from Wyeth's grasp. The realities of the Oregon country and the stiff competition of the Hudson's Bay Company proved too much. He withdrew and returned in 1836 to Boston to resume his career as an inventor and ice merchant (Sampson 1968: 397-401).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/hrs2a.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002