| Family XXXIX. ANATINAE. DUCKS. GENUS V. FULIGULA. SEA-DUCK. |

Next >> |

Family |

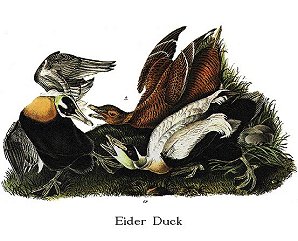

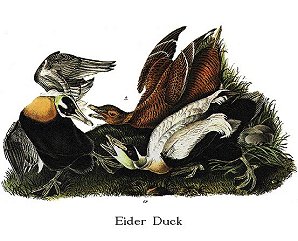

THE EIDER DUCK. [Common Eider.] |

| Genus | FULIGULA MOLLISSIMA, Linn. [Somateria mollissima.] |

The history of this remarkable Duck must ever be looked upon with great interest by the student of nature. The depressed form of its body, the singular

shape of its bill, the beautiful colouring of its plumage, the value of its down

as an article of commerce, and the nature of its haunts, render it a very

remarkable species. Considering it as such, I shall endeavour to lay before you

as full an account of it as I have been able to obtain from my own observation.

The fact that the Eider Duck breeds on our eastern coasts, must be

interesting to the American ornithologist, whose fauna possesses but few birds

of this family that do so. The Fuligulae are distinguished from all other Ducks

that feed in fresh or salt water, by the comparative shortness of the neck, the

greater expansion of their feet, the more depressed form of their body, and

their power of diving to a considerable depth, in order to reach the beds on

which their favourite shelly food abounds. Their flight, too, differs from that

of the true Ducks, inasmuch as it is performed nearer the surface of the water.

Rarely, indeed, do the Fuligulae fly at any considerable height over that

element, and with the exception of three species, they are rarely met with

inland, unless when driven thither by storms. They differ, more-over, in their

propensity to breed in communities, and often at a very small distance from each

other. Lastly, they are in general more ready to abandon their females, the

moment incubation has commenced. Thus the female is left in a state of double

responsibility, which she meets, however, with a courage equal to the occasion,

although alone and unprotected.

The Eider is now seldom seen farther south along our eastern coast than the

vicinity of New York. WILSON says they are occasionally observed as far as the

Capes of Delaware; but at the present day this must be an extremely rare

occurrence, for the fishermen of the Jerseys informed me that they knew nothing

of this Duck. In WILSON'S time, however, it bred in considerable numbers, from

Boston to the Bay of Fundy, and it is still to be met with on the rocky shores

and islands between these points. Farther to the eastward they become more and

more plentiful, until you reach Labrador, to which thousands of pairs annually

resort, to breed and spend the short summer. Many, however, proceed much

farther north; but, as usual, I will here confine myself to my own observations.

In the latter part of October 1832, the Eiders were seen in considerable

numbers in the Bay of Boston. A large bagful of them was brought to me by a

fisherman-gunner in my employ, a person advanced in years, formerly a brave tar,

and one whom I feel some pride in telling you I assisted in obtaining a small

pension from our government, being supported in my application by two of my

Boston friends, the one the generous GEORGE PARKMAN, M. D., the other that great

statesman JOHN QUINCY ADAMS. The old man had once served under my father, and

to receive a bagful of Eider Ducks from him was a gratification which you may

more easily conceive than I can describe. Well, there were the Ducks, all

turned out on the floor; young males still resembling their mother, others of

more advanced age, and several males and females complete in all their parts,

only that the bills of the former had lost the orange tint, which that part

exhibits during a few weeks of the breeding season. Twenty-one there were in

all, and they had been killed in a single day by the veteran and his son. Those

masterly gunners told me, that to procure this species, they were in the habit

of anchoring their small vessel about fifty yards off the rocky isles round

which these birds harbour and feed at this season. There, while the birds were

passing on wing, although usually in long lines, they could now and then kill

two of them at a shot. Sometimes the King Eider was also procured under similar

circumstances, as the two species are wont to associate together during winter.

At Boston the Eiders sold that winter at from fifty to seventy-five cents the

pair, and they are much sought after by epicures.

On the 31st of May, 1833, my son and party killed six Eiders on the island

of Grand Manan, off the Bay of Fundy, where the birds were seen in considerable

numbers, and were just beginning to breed. A nest containing two eggs, but not

a particle of down, was found at a distance of more than fifty yards from the

water.

Immediately after landing on the coast of Labrador, on the 18th of June in

the same year, we saw a great number of "Sea Ducks," as the gunners and

fishermen on that coast, as well as on our own, call the Eiders and some other

species. On visiting an island in "Partridge Bay," we procured several females.

The birds there paid little attention to us, and some allowed us to approach

within a few feet before they left their nests, which were so numerous that a

small boat-load might have been collected, had the party been inclined. They

were all placed amid the short grass growing in the fissures of the rock, and

therefore in rows, as it were. The eggs were generally five or six, in several

instances eight, and in one ten. Not a male bird was to be seen. At the first

discharge of the guns, all the sitting birds flew off and alighted in the sea,

at a distance of about a hundred yards. They then collected, splashed up the

water, and washed themselves, until the boat left the place. Many of the nests

were unprovided with down; some had more or less than others, and some, from

which the female was absent when the party landed, were quite covered with it,

and the eggs felt warm to the hand. The musquitoes and flies were there as

abundant and as tormenting as in any of the Florida swamps.

On the 24th of the same month, two male Eiders, much advanced in the moult,

were shot out of a flock all composed of individuals of the same sex. While

rambling over the moss-covered shores of a small pond, on the 7th of July, we

saw two females with their young on the water. As we approached the edges, the

old birds lowered their heads and swam off with those parts lying flat on the

surface, while the young followed so close as almost to touch them. On firing

at them without shot, they all dived at once, but rose again in a moment, the

mothers quacking and murmuring. The young dived again, and we saw no more of

them; the old birds took to wing, and, flying over the hills, made for the sea,

from which we were fully a mile distant. How their young were to reach it was

at that time to me a riddle; but was afterwards rendered intelligible, as you

will see in the sequel. On the 9th of July, while taking an evening walk, I saw

flocks of female Eiders without broods. They were in deep moult, kept close to

the shore in a bay, and were probably sterile birds. On my way back to the

vessel, the captain and I started a female from a broad flat rock, more than a

hundred yards from the water, and, on reaching the spot, we found her nest,

which was placed on the bare surface, without a blade of grass within five yards

of it. It was of the usual bulky construction, and contained five eggs, deeply

buried in down. She flew round us until we retired, when we had the pleasure to

see her alight, walk to her nest, and compose herself upon it.

Large flocks of males kept apart, and frequented the distant sea islands at

this period, when scarcely any were able to fly to any distance, although they

swam about from one island to another with great ease. Before their moulting

had commenced, or fully a month earlier, these male birds, we observed, flew in

long lines from place to place around the outermost islands every morning and

evening, thus securing themselves from their enemies, and roosted in numbers

close together on some particular rock difficult to be approached by boats,

where they remained during the short night. By the 1st of August scarcely an

Eider Duck was to be seen on the coast of Labrador. The young were then able to

fly, the old birds had nearly completed their moult, and all were moving

southward.

Having now afforded you some idea of the migrations and general habits of

this interesting bird from spring to the close of the short summer of the

desolate regions of Labrador, I proceed, with my journals before me, and my

memory refreshed by reading my notes, to furnish you with such details as may

perhaps induce you to study its habits in other parts of the world.

The Eider Duck generally arrives on the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador

about the 1st of May, nearly a fortnight before the waters of the Gulf of St.

Lawrence are freed from ice. None are seen there during winter, and their first

appearance is looked upon with pleasure by the few residents as an assurance of

the commencement of the summer season. At this period they are seen passing in

long files not many feet above the ice or the surface of the water, along the

main shores, and around the inner bays or islands, as if in search of the places

where they had formerly nestled, or where they had been hatched. All the birds

appear to be paired, and in perfect plumage. After a few days, during which

they rest themselves on the shores fronting the south, most of them remove to

the islands that border the coast, at distances varying from half a mile to five

or six miles. The rest seek for places in which to form their nests, along the

craggy shores, or by the borders of the stunted fir woods not far from the

water, a few proceeding as far as about a mile into the interior. They are now

seen only in pairs, and they soon form their nests. I have never had an

opportunity of observing their courtships, nor have I received any account of

them worthy of particular notice.

In Labrador, the Eider Ducks begin to form their nests about the last week

of May. Some resort to islands scantily furnished with grass, near the tufts of

which they construct their nests; others form them beneath the spreading boughs

of the stunted firs, and in such places, five, six, or even eight are sometimes

found beneath a single bush. Many are placed on the sheltered shelvings of

rocks a few feet above high-water mark, but none at any considerable elevation,

at least none of my party, including the sailors, found any in such a position.

The nest, which is sunk as much as possible into the ground, is formed of

sea-weeds, mosses, and dried twigs, so matted and interlaced as to give an

appearance of neatness to the central cavity, which rarely exceeds seven inches

in diameter. In the beginning of June the eggs are deposited, the male

attending upon the female the whole time. The eggs, which are regularly placed

on the moss and weeds of the nest, without any down, are generally from five to

seven, three inches in length, two inches and one-eighth in breadth, being thus

much larger than those of the domestic Duck, of a regular oval form,

smooth-shelled, and of a uniform pale olive-green. I may here mention, by the

way, that they afford delicious eating. I have not been able to ascertain the

precise period of incubation. If the female is not disturbed, or her eggs

removed or destroyed, she lays only one set in the season, and as soon as she

begins to sit the male leaves her. When the full complement of eggs has been

laid, she begins to pluck some down from the lower parts of her body; this

operation is daily continued for some time, until the roots of the feathers, as

far forward as she can reach, are quite bare, and as clean as a wood from which

the undergrowth has been cleared away. This down she disposes beneath and

around the eggs. When she leaves the nest to go in search of food, she places

it over the eggs, and in this manner, it may be presumed to keep up their

warmth, although it does not always ensure their safety, for the Black-backed

Gall is apt to remove the covering, and suck or otherwise destroy the eggs.

No sooner are the young hatched than they are led to the water, even when

it is a mile distant, and the travelling difficult, both for the parent bird and

her brood; but when it happens that the nest has been placed among rocks over

the water, the Eider, like the Wood Duck, carries the young in her bill to their

favourite element. I felt very anxious to find a nest placed over a soft bed of

moss or other plants, to see, whether, like the Wood Duck on such occasions, the

Eider would suffer her young ones to fall from the nest; but unfortunately I had

no opportunity of observing, a case of this kind. The care which the mother

takes of her young for two or three weeks, cannot be exceeded. She leads them

gently in a close flock in shallow waters, where, by diving, they procure food,

and at times, when the young are fatigued, and at some distance from the shore,

she sinks her body in the water, and receives them on her back, where they

remain several minutes. At the approach of their merciless enemy, the

Black-backed Gull, the mother beats the water with her wings, as if intending to

raise the spray around her, and on her uttering a peculiar sound, the young dive

in all directions, while she endeavours to entice the marauder to follow her, by

feigning lameness, or she leaps out of the water and attacks her enemy, often so

vigorously, that, exhausted and disappointed, he is glad to fly off, on which

she alights near the rocks, among which she expects to find her brood, and calls

them to her side. Now and then I saw two females which had formed an attachment

to each other, as if for the purpose of more effectually contributing to the

safety of their young, and it was very seldom that I saw these prudent mothers

assailed by the Gull.

The young, at the age of one week, are of a dark mouse-colour, thickly

covered with soft warm down. Their feet at this period are proportionally very

large and strong. By the 20th of July they seemed to be all hatched. They grew

rapidly, and when about a fortnight old were, with great difficulty, obtained,

unless during stormy weather, when they at times retired from the sea to shelter

themselves under the shelvings of the rocks at the head of shallow bays. It is

by no means difficult to rear them, provided proper care be taken of them, and

they soon become quite gentle and attached to the place set apart for them. A

fisherman of Eastport, who carried eight or ten of them from Labrador, kept them

several years in a yard close to the water of the bay, to which, after they were

grown, they daily betook themselves, along with some common Ducks, regularly

returning on shore towards evening. Several persons who had seen them, assured

me that they were as gentle as their associates, and although not so active on

land, were better swimmers, and moved more gracefully on the water. They were

kept until the male birds acquired their perfect plumage and mated; but some

gunners shot the greater number of them one winter day, having taken them for

wild birds, although none of them could fly, they having been pinioned. I have

no doubt that if this valuable bird were domesticated, it would prove a great

acquisition, both on account of its feathers and down, and its flesh as an

article of food. I am persuaded that very little attention would be necessary

to effect this object. When in captivity, it feeds on different kinds of grain

and moistened corn-meal, and its flesh becomes excellent. Indeed, the sterile

females which we procured at Labrador in considerable number, tasted as well as

the Mallard. The males were tougher and more fishy, so that we rarely ate of

them, although the fishermen and settlers paid no regard to sex in this matter.

When the female Eider is suddenly discovered on her nest, she takes to wing

at a single spring; but if she sees her enemy at some distance, she walks off a

few steps, and then flies away. If, unseen by a person coming near, as may

often happen, when the nest is placed under the boughs of the dwarf fir, she

will remain on it, although she may hear people talking. On such occasions my

party frequently discovered the nests by raising the pine branches, and were

often as much startled as the Ducks themselves could be, as the latter instantly

sprung past them on wing, uttering a harsh cry. Now and then some were seen to

alight on the ground within fifteen or twenty yards, and walk as if lame and

broken-winged, crawling slowly away, to entice their enemies to go in pursuit.

Generally, however, they would fly to the sea, and remain there in a large flock

until their unwelcome visiters departed. When pursued by a boat, with their

brood around them, they allowed us to come up to shooting distance, when,

feigning decrepitude, they would fly off, beating the water with partially

extended wings, while the young either dived or ran on the surface with

wonderful speed, for forty or fifty yards, then suddenly plunged, and seldom

appeared at the surface unless for a moment. The mothers always flew away as

soon as their brood dispersed, and then ended the chase. The cry or note of the

female is a hoarse rolling croak; that of the male I never heard.

Should the females be robbed of their eggs, they immediately go off in

search of mates, whether their previous ones or not I cannot tell, although I am

inclined to think so. However this may be, the duck in such a case soon meets

with a drake, and may be seen returning the same day with him to her nest. They

swim, fly, and walk side by side, and by the end of ten or twelve days the male

takes his leave, and rejoins his companions out at sea, while the female is

found sitting on a new set of eggs, seldom, however, exceeding four. But this

happens only at an early period of the season, for I observed that as soon as

the males had begun to moult, the females, whose nests had been plundered,

abandoned the place. One of the most remarkable circumstances connected with

these birds is, that the females with broods are fully three weeks later in

moulting than the males, whereas those which do not breed begin to moult as

early as they. This may probably seem strange, but I became quite satisfied of

the fact while at Labrador, where, from the number which we procured in a state

of change, and the vast quantities every now and then in sight, our

opportunities of observing these birds in a perfectly natural state were ample.

Some authors have said that the males keep watch near the females; but,

although this may be the case in countries such as Greenland and Iceland, where

the Eiders have been trained into a state of semi-domestication, it certainly

was not so in Labrador. Not a single male did we there see near the females

after incubation had commenced, unless in the case mentioned above, when the

latter had been deprived of their eggs. The males invariably kept aloof and in

large flocks, sometimes of a hundred or more individuals, remaining out at sea

over large banks with from seven to ten fathoms of water, and retiring at night

to insular rocks. It seemed very wonderful that in the long lines in which we

saw them travelling, we did not on any occasion discover among them a young

bird, or one not in its mature plumage. The young males, if they breed before

they acquire their full colouring, must either be by themselves at this period,

or with the barren females, which, as I have already said, separate from those

that are breeding. I am inclined to believe that the old males commence their

southward migration before the females or the young, as none were to be seen for

about a fortnight before the latter started. In winter, when these Ducks are

found on the Atlantic shores of the United States, the males and females are

intermingled; and at the approach of spring the mated pairs travel in great

flocks, though disposed in lines, when you can distinctly see individuals of

both sexes alternating.

The flight of the Eider is firm, strong, and generally steady. They propel

themselves by constant beats of the wings, undulating their lines according to

the inequality of surface produced by the waves, over which they pass at the

height of a few yards, and rarely more than a mile from the shores. Few fly

across the Gulf of St. Lawrence, as they prefer following the coasts of Nova

Scotia and Newfoundland, to the eastern entrance of the straits of Belle Isle,

beyond which many proceed farther north, while others ascend that channel and

settle for the season along the shores of Labrador, as far up as Partridge Bay,

and still farther up the St. Lawrence. Whilst on our waters, or at their

breeding grounds, the Eiders are not unfrequently seen flying much higher than

when travelling, but in that case they seem to be acting with the intention of

guarding against their enemy man. The velocity of their flight has been

ascertained to be about eighty miles in the hour.

This species dives with great agility, and can remain a considerable time

under water, often going down in search of food to the depth of eight or ten

fathoms, or even more. When wounded, however, they soon become fatigued in

consequence of the exertion used in diving, and may be overtaken by a

well-manned boat in the course of half an hour or so, as when fatigued they swim

just below the surface, and may be struck dead with an oar or a boat-hook.

Their food consists principally of shell-fish, the shells of which they

seem to have the power of breaking into pieces. In many individuals which I

opened, I found the entrails almost filled with small fragments of shells mixed

with other matter. Crustaceous animals and their roe, as well as that of

various fishes, I also found in their stomach, along with pebbles sometimes as

large as a hazel nut. The oesophagus, which is in form like a bag, and is of a

leathery firm consistence, was often found distended with food, and usually

emitted a very disagreeable fishy odour. The gizzard is extremely large and

muscular. The trachea of the young male, so long as it remains in its imperfect

plumage, or for the first twelve months, does not resemble that of the old male.

The males do not obtain their full plumage until the fourth winter. They at

first resemble the mother, then gradually become pie-bald, but not in less time

than between two and three years.

The Eider Duck takes a heavy shot, and is more easily killed on wing than

while swimming. When on shore they mark your approach while you are yet at a

good distance, and fly off before you come within shot. Sometimes you may

surprise them while swimming below high rocks, and, if you are expert, then

shoot them; but when they have first seen you, it is seldom that you can procure

them, as they dive with extreme agility. While at Great Macatina Harbour, we

discovered a large basin of water, communicating with the sea by a very narrow

passage about thirty yards across, and observed that at particular stages of the

tides the Eider Ducks entered and returned by it. By hiding ourselves on both

sides of this channel, we succeeded in killing a good number, but rarely more

than one at a shot, although sometimes we obtained from a single file as many as

we had of gun-barrels.

Excepting in a single nest, I found no down clean, it having been in every

other instance more or less mixed with small dry fir twigs and bits of grass.

When cleaned, the down of a nest rarely exceeds an ounce in weight, although,

from its great elasticity, it is so bulky as to fill a hat, or if properly

prepared even a larger space. The eggers of Labrador usually collect it in

considerable quantity, but at the same time make such havoc among the birds,

that at no very distant period the traffic must cease.

EIDER DUCK, Anas mollissima, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. viii. p. 122.

FULIGULA MOLLISSIMA, Bonap. Syn., p. 389.

SOMATERA MOLLISSIMA, Eider, Swains. and Rich. F. Bor. Amer., vol. ii.p. 448.

EIDER DUCK, Nut t. Man., vol. ii. p. 406.

EIDER DUCK, Fuligula mollissima, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iii. p. 344; vol. v. p. 611.

Male, 25, 42. Female, 24, 39.

Breeds in Maine, on the Bay of Fundy, in Labrador, Newfoundland, as far

northward as travellers have proceeded. Common in winter from Nova Scotia to

Massachusetts; rarely seen in New York.

Adult Male.

Bill about the length of the head, deeper than broad at the base, somewhat

depressed towards the end, which is broad and rounded. Upper mandible with a

soft tumid substance at the base, extending upon the forehead, and deeply

divided into two narrow rounded lobes, its whole surface marked with divergent

oblique lines, the dorsal outline nearly straight and sloping to beyond the

nostrils, then curved, the ridge broad at the base, broadly convex towards the

end, the edges perpendicular, obtuse, with about fifty small lamellae on the

inner side, the unguis very large, elliptical. Nostrils sub-medial, oblong,

large, pervious, nearer the ridge than the edge. Lower mandible flattened, with

the angle very long, rather narrow and rounded, the dorsal line short and

slightly convex, the edges with about sixty lamellae, the unguis very broad,

elliptical.

Head very large. Eyes of moderate size. Neck of moderate length, rather

slender at its upper part. Body bulky and much depressed. Wings rather small.

Feet very short, strong, placed rather far behind; tarsus very short,

compressed, anteriorly having a series of scutella in its whole length, and a

partial series above the fourth toe, the rest reticulated with angular scales.

Hind toe small, with a free membrane beneath; anterior toes double the length of

the tarsus, connected by reticulated membranes, having a sinus at their free

margins, the inner with a broad lobed marginal membrane, the outer with a

thickened edge; all obliquely scutellate above, the third and fourth about equal

and longest. Claws small, that of first toe very small and curved, of middle

toe largest, all rather depressed and blunt.

Plumage short, dense, soft, blended. Feathers on the fore part of the head

extremely small; on the upper part very narrow, on the occiput and upper and

lateral parts of the neck hair-like, stiff and glossy. Wings rather short,

narrow, pointed; primary quills curved, strong, tapering, the first longest, the

second scarcely shorter, the rest rapidly graduated; secondaries short, broad,

rounded, the inner elongated, tapering, and recurved. Tail very short, much

rounded, of sixteen narrow feathers.

Bill pale greyish-yellow, the unguis lighter, the soft tumid part pale

flesh-colour. Iris brown. Feet dingy light green, the webs dusky. Upper part

of the head bluish-black; the central part from the occiput to the middle white.

The hair-like feathers on the upper part and sides of the neck are of a delicate

pale green tint. The sides of the head, the throat, and the neck, are white,

the fore neck at its lower part of a fine colour intermediate between buff and

cream-colour. The rest of the lower surface is brownish-black, as are the upper

tail-coverts, and the central part of the rump. The rest of the back, the

scapulars, smaller wing-coverts, and inner curved secondary quills, white, the

scapulars tinged with yellow. Secondary coverts and outer secondaries

brownish-black; primaries and tail-coverts greyish-brown.

Length to end of tail 25 inches, to end of wings 21 1/2, to end of claws

27; extent of wings 42; wing from flexure 11 1/2; tail 4 1/4; bill from

extremity of tumid part 2 10/12, from its notch 2 2/12, along the edge of lower

mandible 2 10/12; tarsus 1 3/4; middle toe 2 10/12, its claw 7/12. Weight in

winter, 5 lbs. 5 1/2 oz.; in breeding time 4 lbs. 8 1/2 oz.

Adult Female.

The female differs greatly from the male. The bill is shorter, its tumid

basal part much less and narrower. The feathers of the head and upper part of

the neck are very small, soft, and uniform; the scapulars and inner secondaries

are not elongated, as in the male. Bill pale greyish-green; iris and feet as in

the male. The head and neck all round light brownish-red, with small lines of

brownish-black. Lower part of neck all round, the whole upper surface, the

sides, and the lower tail-coverts of the same colours, but there the

brownish-black markings are broad. Secondary quills and larger coverts

greyish-brown, tipped with white, primaries brownish-black; tail-feathers

greyish-brown. Breast and abdomen greyish-brown, obscurely mottled.

Length to end of tail 24 inches, to end of wings 20 1/2, to end of claws

27; extent of wings 39; wing from flexure 11 1/4; tail 4; bill 3 7/12; tarsus

1 3/4; middle toe 2 7/12, its claw (5 1/2)/12. Weight in winter 4 lbs.

4 1/2 oz.; in breeding time 3 lbs. 12 oz.

The down of the female is light grey; that of the male on the white parts

is pure white, on the dark, greyish-white.

I have represented three of these birds in a state of irritation. A mated

pair, having a few eggs already laid, have been approached by a single male, and

are in the act of driving off the intruder, who, to facilitate his retreat, is

lashing his antagonists with his wings.

Adult Male, from Dr. T. M. BREWER. The roof of the mouth is broadly and

deeply concave; the posterior aperture of the nares linear, 10 twelfths long,

margined with two rows of very pointed papillae. Tongue 2 inches long, convex

above, with a large median groove, fleshy, very thick, with a semicircular

thin-edged horny tip; the breadth at the base 4 3/4 twelfths, at the tip 4

twelfths; the sides with two longitudinal series of bristles. The width of the

mouth is 1 inch 3 twelfths. The oesophagus is 10 1/2 inches long, for 4 1/2

inches, its width is 1 inch, it then enlarges so as to form what might be

considered as a kind of crop, 1 inch 7 twelfths in width; after this it

continues of the uniform diameter of 1 inch, but in the proventriculus, Fig. 1,

[b c], enlarges to 1 1/4 inches. Its muscular walls are very thick, and the

external fibres conspicuous, the inner coat longitudinally plicate. The left

lobe of the liver is 2 inches 2 twelfths long, the right lobe 4 inches. The

gall-bladder elliptical, 1 inch 5 twelfths in length, 11 twelfths in breadth.

The stomach, [c d e f g h], is a gizzard of enormous size, placed obliquely,

transversely elliptical, its length 2 1/2 inches, its breadth 3 inches. The

proventricular glands are extremely numerous, and form a belt 2 inches in

breadth. The left muscle of the stomach, [d e], is 1 1/4 inches thick, the

right, [g h], 1 inch 2 twelfths; the epithelium very thick, and of a horny

texture, with two elliptical convex grinding plates, of which the right is 2

inches in length, the left 1 inch 7 twelfths. Intestine 74 inches long; the

width of the duodenum, [h i j], 1/2 inch, diminishing to 5 twelfths; the rectum, Fig. 2, [a b], 7 twelfths in width; the coeca, [c c], 3 1/2 inches long, 4

inches distant from the extremity; their greatest width 4 1/2 twelfths, for an

inch at the base only 1 twelfth; the cloaca very slightly dilated, its breadth

being only 8 twelfths.

The trachea is 9 1/4 inches long, nearly of the uniform width of 5

twelfths, moderately flattened; the rings 130, well ossified, ending in a

transversely oblong dilatation, projecting more toward the left side, 1 inch in

breadth, 1/2 inch in length. Bronchial half rings 32, the bronchi very wide,

rings very narrow and cartilaginous. The contractor muscles are very large, and

expanded over the whole anterior surface. At the distance of 1 1/2 inches from

the tympanum they give off the cleido-tracheal muscles, and at the tympanum

itself the stern tracheal.

| Next >> |