Dachau Trials

US vs. Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-Pyrmont

Trial of 31 war criminals

from Buchenwald concentration camp

On March 4, 1947, war crimes charges

were brought against Hermann

Pister, the Commandant of the Buchenwald concentration camp

from 1942 to 1945, and 30 others associated with the camp.

The proceedings against the 31 accused

Buchenwald war criminals began on April 11, 1947, the second

anniversary of the liberation of the camp by the 6th Armored Division

of the US Third Army.

The "Buchenwald trial" was

held in a courtroom at the Dachau concentration camp complex;

it was officially known as US vs. Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-Pyrmont,

Case No. 000-50-5-9. Waldeck was an SS general and the highest

ranking person among the accused.

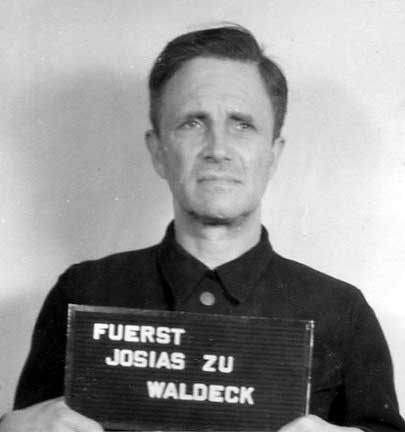

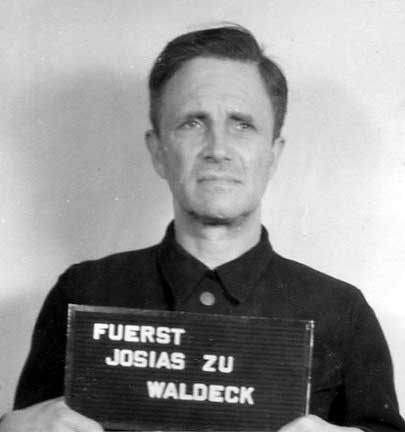

Josias Erbprinz zu

Waldeck-Pyrmont

Ilse

Koch, the wife of former Buchenwald

Commandant Karl Otto Koch, was the most famous of the 31 war

criminals in the Buchenwald case. She was accused of having prisoners

killed at Buchenwald and then having their tattooed skin removed

to make human lamp shades.

Among the accused was Hans Merbach, the SS soldier who had been

in charge of the transport train on which around 5,000 Buchenwald

inmates were transported to the Dachau concentration camp, and

only about 25% of them survived the trip. This was the infamous

Death

Train which was discovered by the American liberators on

the day that they liberated the Dachau concentration camp.

The Nazi concentration camps had been

declared to be a criminal enterprise by the Allies. Under the

Allied concept of co-responsibility which was used in all the

World War II war crimes trials, anyone who worked in one of the

camps in any capacity was a war criminal. The 31 accused persons

in the Buchenwald trial included at least one person who represented

each job title in the camp.

The relatively low number of Buchenwald

war criminals might have been due to the fact that 76 of the

SS staff members had been hunted down and killed by the inmates

with the help of the American liberators. It was not a war crime

for American soldiers to kill German POWs at that time because

General Dwight D. Eisenhower had had the foresight in March 1945

to designate all future German POWs as Disarmed Enemy Forces

in order to get around the rules of the Geneva Convention of

1929, which America had signed.

The list of the 31 accused war criminals

in the main Buchenwald case is as follows:

Otto Barnewald

August Bender

Anton Bergmeier

Arthur Dietzsch (Kapo)

Dr. Hans Eisele (Camp doctor)

Werner Greunuss

Philipp Grimm

Hermann Grossmann

Heinrich Hackmann

Gustav Heigel

Hermann Helbig

Dr. Edwin Katzen-Ellenbogen (prisoner)

Josef Kestel

Ilse Koch

Richard Koehler

Hubert Krautwurst

Hans Merbach

Peter Merker

Wolfgang Otto

Hermann Pister (Camp Commandant)

Emil Pleissner

Guido Reimer

Helmut Rocher

Hans Schmidt

Max Schobert

Albert Schwartz

Josias, Erbprinz von und zu Waldeck-Pyrmont (SS general)

Dr. Walter Wendt (Kapo)

Friedrich Wilhelm

Hans Wolf

Hans Zinecker

Famous photo shows

emaciated Buchenwald prisoners

The charges against the 31 accused war

criminals in the Buchenwald trial was that they had participated

in a "common design" or a "common plan" to

violate the Laws and Usages of War under the Hague Convention

of 1907 and the Geneva Convention of 1929. These two conventions

stated the rules of warfare pertaining to Enemy Prisoners of

War.

Buchenwald was not a prisoner of war

camp, but in the proceedings of the American Military Tribunals

at Dachau, the prisoners in the Nazi concentration camps were

regarded as detainees who were entitled to the same treatment

as POWs under the Geneva Convention of 1929. It was not until

1949, after all the Military Tribunals had been concluded, that

a new Geneva Convention gave all detainees the same rights as

POWs.

In the photo below, a Russian Prisoner

of War points an accusing finger at a German guard whom he claimed

had abused him at the Buchenwald camp; this photo was taken on

April 14, 1945, three days after the camp was liberated.

Buchenwald guard is

identified by a Russian prisoner

Photo Credit: USHMM

A panel of American military officers,

guided by "law member" Lt. Col. John S. Dwinell, who

made legal rulings, served as both judge and jury for the proceedings.

The court president was Brig. Gen. Emil Charles Kiel. The accused

were defended by American military officers, led by Captain Emmanuel

Lewis, the chief defense counsel. Dr. Richard Wacker was one

of the defense attorneys.

The chief prosecutor was 34-year-old

Lt. Col. William Denson, who had a conviction rate of 100% in

similar proceedings against the staff members of the Dachau,

Mauthausen, and Flossenbürg concentration camps.

Josias Erbprinz zu

Waldeck-Pyrmont sentenced to life, August 14, 1947

Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-Pyrmont, the

highest ranking prisoner among the accused, was an SS-Obergruppenführer

and head of judicial matters in the district which included the

city of Weimar and the Buchenwald camp. Waldeck was a member

of the German royalty, who had joined the SS in 1929. He is shown

in the photograph above, as he faced the Tribunal to hear his

sentence of life in prison. His crime was that he had allowed

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, who reported directly

to Hitler, to maintain a concentration camp at Buchenwald which

was in his district.

Waldeck was the one who blew the whistle

on Buchenwald Commandant Karl Otto Koch in 1943 after he noticed

the name of Dr. Walter Kramer on a list of political prisoners

who had been executed on Koch's orders. By that time, Koch had

been transferred to the Majdanek death camp in Poland, but his

wife, Ilse, was still living at the Commandant's house in Buchenwald.

Waldeck ordered a full scale investigation of the camp by Dr.

Georg Konrad Morgen, an SS officer who was a judge in a German

court. It was during this investigation that prisoners at Buchenwald

told Dr. Morgen about the lampshades allegedly made from human

skin.

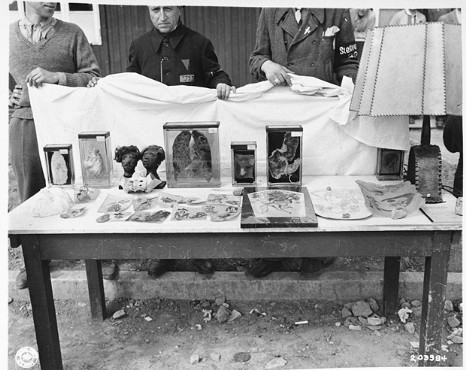

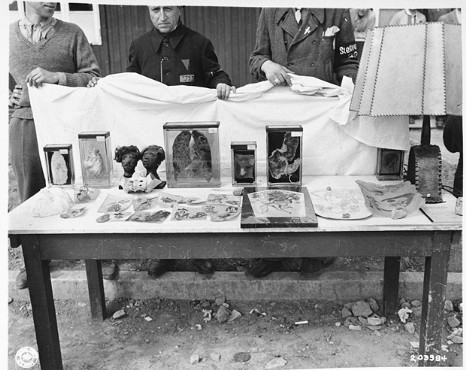

After American soldiers had liberated

the Buchenwald camp, they were astounded when the Communist prisoners

took them on a tour of the camp, showing them pieces of tattooed

human skin, two shrunken heads, preserved human body parts, an

ash tray made from a human bone, and a table lamp with a lampshade

allegedly made from human skin. The shrunken heads resembled

those made by primitive tribes in South America.

A movie about the Buchenwald camp, directed

by famed Hollywood director Billy Wilder, had been made by a

film crew of the Signal Corps of the US Army shortly after the

liberation of the camp; it included some footage of a display

table. The photograph below is a still shot from the film which

was shown during the proceedings at Dachau.

Body parts in jars,

shrunken heads, tattooed skin and table lamp

The proceedings against the 31 accused

in the "Buchenwald trial" began with the showing of

the film made by Billy Wilder. The defense objected, pointing

out that the film had been made three or four days after the

camp came under the control of the American Army, and that it

did not show anything that had occurred prior to that time. The

objection was overruled and the film was shown. The defense also

objected to the display of the two shrunken heads, but this objection

was also overruled.

The narration in the film, as quoted

by Joshua M. Greene, in his book "Justice at Dachau,"

is as follows:

This is a pictorial record of the

almost unprecedented crimes perpetrated by the Nazis at the Buchenwald

concentration camp. In the official report, Buchenwald is termed

an extermination factory, and the means of extermination: starvation

complicated by hard work, abuse, beatings, tortures, incredibly

crowded sleeping conditions, and sicknesses of all types. This

is the body disposal plant. There inside are the ovens that gave

the crematory a maximum disposal capacity of four hundred bodies

per ten-hour day. The ovens are extremely modern in design, made

by a firm that specialized in baking ovens. All bodies were finally

reduced to bone ash. One of the first things that German civilians

from neighboring Weimar see on a forced tour of the camp is the

parchment display. A lampshade, made of human skin, made at the

request of an SS officer's wife..."

The SS officer's wife, who was mentioned

in the film, was none other than Ilse Koch, the "Bitch of

Buchenwald," and the wife of the former Commandant, Karl

Otto Koch.

Dr. Kurte Sitte, a 36-year-old doctor

of Physics at Manchester University who had been a political

prisoner at Buchenwald since September 1939, testified at the

Buchenwald trial that a shrunken head, which he identified in

the courtroom, was the head of a Polish prisoner who had been

decapitated on the order of SS Doctor Mueller at Buchenwald.

Although the prisoners in all the Nazi camps had their heads

shaved, this Polish prisoner had long black hair at the time

he was decapitated.

Prosecution witness

Dr. Kurte Sitte holds shrunken head in the courtroom

Defense attorney Capt. Emmanuel Lewis

objected to the admission of the shrunken head into evidence

because Dr. Mueller was not on trial, but his objection was overruled.

Under the rules of the American Military Tribunals, any and all

evidence was admissible, whether or not it pertained to the case,

because the charges against all of the accused was participating

in a "common plan" to commit war crimes.

At the suggestion of General Dwight D.

Eisenhower, a group of newspaper reporters and U.S. Congressmen

were flown in from America; they were taken on a grand tour of

the Buchenwald camp on April 24, 1945 and shown all the gory

artifacts on the display table pictured above. Every major newspaper

in America carried the story of how Ilse Koch, the wife of the

Commandant, had imperiously ridden her chestnut stallion through

the Buchenwald camp, selecting tattooed prisoners to be killed

by her lover in order to make human lamp shades for her home.

The nickname, "Bitch of Buchenwald,"

was given to Isle Koch by a reporter, and it soon became a household

word in America. The public couldn't get enough of the lampshade

story and the proceedings of the Military Tribunal at Dachau

were sensationalized by the media. Film clips from the Buchenwald

camp, with footage of the display table, were shown in the newsreels

in every American theater. In the two years since the liberation

of Buchenwald, Ilse Koch had already been convicted by the media.

The Military Tribunal proceedings were filmed and every week,

film clips were shown in the newsreels at the movie theaters

in America.

After the German Army surrendered to

the Allies in May 1945, a total of 1,672 German war criminals

were brought before a series of American Military Tribunals,

held at the former Dachau concentration camp, between November

1945 and December 1947. These cases against staff members of

the Nazi concentration camps were those in which the American

military had jurisdiction by virtue of having been the liberators

of the camps where the crimes had been committed.

The authority for charging the defeated

Germans with war crimes came from the London Agreement, signed

on August 8, 1945 by the four winning countries: Great Britain,

France, the Soviet Union and the USA. The basis for the proceedings

of the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal against the

accused German war criminals was Law Order No. 10, issued by

the Allied Control Council, the governing body for Germany before

the country was divided into East and West Germany. Law Order

No. 10 defined Crimes against Peace, War Crimes, and Crimes against

Humanity. A fourth crime category was membership in any organization,

such as the Nazi party, the SS or the Gestapo, all of which were

declared to be criminal under Law Order No. 10.

In addition to the war crimes prosecuted

by the Nuremberg IMT, Law Order No. 10 also gave the authority

for each of the Allied countries to conduct trials of their own.

The proceedings of the American Military Tribunals at Dachau

were conducted according to "the rules and procedure"

determined by the Zone Commander of the American Zone of occupation,

as authorized by Law Order No. 10.

The following quote is from Article III

of Law Order No. 10:

Article III

1. Each occupying authority, within

its Zone of Occupation,

[...]

(d) shall have the right to cause

all persons so arrested and charged, and not delivered to another

authority as herein provided, or released, to be brought to trial

before an appropriate tribunal.

[...]

2. The tribunal by which persons charged

with offenses hereunder shall be tried and the rules and procedure

thereof shall be determined or designated by each Zone Commander

for his respective Zone.

Although commonly referred to as "trials,"

the proceedings at Dachau were technically not trials because

the normal rules of court trials in America or Great Britain

were not followed. Hearsay testimony was allowed and most of

the prosecution witnesses were paid. Affidavits from witnesses

were allowed, which meant that the defense had no opportunity

to cross-examine the witness who had signed the affidavit.

Interrogators questioned the accused

before the proceedings began and established that they were guilty.

The accused were not presumed to be innocent until proven guilty.

The chief interrogator was 24-year-old

Lt. Paul Guth, an American Jew who was born in Vienna and educated

in England before emigrating to the United States. It was Guth's

job to get confessions from the accused, who were then regarded

as guilty until proven innocent. Many of the accused claimed

that they had been beaten or tortured during their interrogation.

The persons on trial were not called

"defendants" because the burden of proof was on them,

not on the prosecution as is customary in a court trial. All

that was necessary, to prove that one of the accused war criminals

was guilty of being part of a "common plan," was to

prove that he had some association with the place where the crimes

had been committed.

The basis for the "common plan"

concept of co-responsibility was Article II, paragraph 2 of Law

Order No. 10 which stated as follows:

2. Any person without regard to nationality

or the capacity in which he acted, is deemed to have committed

a crime as defined in paragraph 1 of this Article, if he was

(a) a principal or (b) was an accessory to the commission of

any such crime or ordered or abetted the same or (c) took a consenting

part therein or (d) was connected with plans or enterprises involving

its commission or (e) was a member of any organization or group

connected with the commission of any such crime or (f) with reference

to paragraph 1 (a), if he held a high political, civil or military

(including General Staff) position in Germany or in one of its

Allies, co-belligerents or satellites or held high position in

the financial, industrial or economic life of any such country.

Under the rules of Article II, as quoted

above, Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-Pyrmont was charged with participating

in a "common plan" to commit any or all of the alleged

crimes at the Buchenwald concentration camp, even though he was

not a member of the staff.

Although there was testimony during the

Nuremberg International Military Tribunal that prisoners had

been killed in a gas chamber at Buchenwald, no one in the

Buchenwald case was specifically charged with this crime. The

accused were only charged with crimes against Allied nationals

during the time that America was at war with Germany, and since

the names of the prisoners who had allegedly been gassed at Buchenwald

were unknown, the alleged gas chambers at Buchenwald were not

mentioned in the Buchenwald trial.

The room where Ilse Koch and other members

of the Buchenwald staff were brought before an American military

tribunal was in one of the buildings in the former Dachau concentration

camp complex. Extra rows of seats had to be installed in the

200-foot-long courtroom to accommodate the crowd of photographers

and reporters who flocked to see the "Bitch of Buchenwald."

The accused war criminals who were awaiting trial were housed

in the prison barracks of the former Dachau concentration camp.

At the opening of the trial, the court

president, Brig. Gen. Emil Charles Kiel, asked the defense counsel,

"How do the accused plead?"

To this, Captain Emmanuel Lewis replied:

As chief defense counsel, I enter

a plea of not guilty for all of the accused. Before we begin,

if it please the court, there is a matter of great concern. The

accused are charged with victimizing captured and unarmed citizens

of the United States, and they seek to defend themselves against

this charge. But despite our repeated requests, the prosecution

has failed to furnish us with the name or whereabouts of even

one single American victim.

Lt. Col. William D. Denson, the chief

prosecutor, replied:

We are unfortunately unable to comply.

The victims were last seen being carted into the crematories.

From there they went up the chimney in smoke, and all the power

of the United States and all the documents in Augsburg cannot

tell us which way they went. We are sorry that we cannot furnish

their whereabouts, but we fail to see that it is material whether

one American or fifty thousand were incarcerated in Buchenwald.

The crimes of these accused would be just as heinous.

Contrary to Lt. Col. Denson's colorful

story of what had happened to these American POWs, it is now

known that, after about three months in Buchenwald, the Americans

were rescued by a Luftwaffe General and transferred to Stalag

III, a POW camp.

The American prisoners at Buchenwald

were members of a group of American Air Force pilots, who had

been supplying the French resistance; they were captured after

being shot down in France. Buchenwald was one of the main camps

for French resistance fighters, and the pilots had been lumped

in with captured French civilians who were fighting as insurgents.

According to the Geneva Convention of 1929, it was a war crime

to aid insurgents in a country that had signed an Armistice and

promised to stop fighting. Technically, these pilots had violated

the Geneva Convention by helping insurgents that were illegal

combatants who had continued to fight after their country had

surrendered.

The defense motion to have the prosecution

furnish the names of the Americans killed at Buchenwald was denied.

In his opening statement in the Buchenwald

proceedings, the chief prosecutor, Lt. Col. Denson, asked for

the death penalty for each of the accused who was charged with

participating in a "common design" to subject the inmates

of Buchenwald to "killings, tortures, starvation, beatings,

and other indignities." He had not asked for the death penalty

for all of the accused in the Dachau, Mauthausen and Flossenbürg

cases, but the Buchenwald crimes were much more heinous.

The accused were charged with violations

of the Geneva Convention of 1929 with respect to Soviet Prisoners

of war, although the Soviet Union had not signed the Convention,

and did not treat German POWs according to its laws during the

war and for 10 years afterwards.

Regarding the rules of the Geneva Convention

of 1929 with respect to Soviet POWs, defense attorney Captain

Lewis said:

We think that the language of the

Convention is simple and clear. It binds only those nations who

sign it as between themselves. It is not binding as between a

signatory and a nation that has refused to join the family of

nations.

In reply, Lt. Col. Denson said the following:

I am perfectly ready, willing, and

able to talk at this time of legality and of the law that is

to be applied here. In Hall's Treatise on International Law,

we have the following quotation: "More than necessary violence

must not be used by a belligerent in all his relations with his

enemy." The fact that Russia was not a signatory to the

convention did not give Germans the right to mistreat Russian

Prisoners of War. The Hague and Geneva Conventions were nothing

more than a clarification of customs and usages already in practice

among civilized nations.

Buchenwald was the site of medical experiments

carried out by doctors in the camp in an effort to find a vaccine

for typhus, a disease which was devastating all the concentration

camps. The Nazis claimed that the subjects of the experiments

were condemned criminals who were prisoners in the camp. Bodies

of prisoners who died after being forced to participate in the

experiments were autopsied by the camp doctors and the internal

organs were then preserved in formaldehyde in glass display cases.

America had developed a typhus vaccine

which had been sent to American POWs in Red Cross packages during

the war. The Germans took great pains to deliver these packages,

and consequently 96% of the American POWs in Germany survived

their imprisonment, according to the Red Cross.

The doctors in all the Nazi concentration

camps delighted in studying and displaying medical oddities,

such as human deformities. This was all part of their obsession

with eugenics and their plan to breed a superior race. According

to Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler, a Munich bishop who was a prisoner

at Dachau, the Dachau concentration camp had a medical museum.

He wrote in his book "What was it like in Dachau?"

that "The museum containing plaster images of prisoners

who were marked by bodily defects or particular characteristics

was gladly visited by Hitler's officers." Given this proclivity

for displaying medical curiosities, it is not at all surprising

that the doctors at Buchenwald removed large sections of tattooed

skin from dead prisoners and preserved it.

In the photograph below, a Buchenwald

prisoner shows preserved body organs to an American Jewish soldier.

Buchenwald prisoner

shows human organs to Corporal Jack Levine

Dr. Eugen Kogon testifies

on April 16, 1947 at Dachau

One of the most famous inmates of Buchenwald

was 43-year-old Dr. Eugen Kogon, an Austrian Social Democrat

and political activist, who was a prisoner there from September

1939 to April 1945. Kogon was the main contributor to The Buchenwald

Report, a 400-page book about the Buchenwald camp which was put

together in only four weeks by the US Army, after conducting

interviews with over 100 former prisoners at the camp. Kogon

later wrote a book called "The Theory and Practice of Hell,"

which was a rewrite of the Buchenwald Report and one of the first

books about the Nazi atrocities in the Buchenwald concentration

camp.

Kogon testified during the Dachau proceedings

about the harsh treatment suffered by the prisoners at Buchenwald,

although he was one of the privileged political prisoners who

actually ran the camp.

Kogon's testimony was contradicted by

Dr. Georg Konrad Morgen who was the main witness for the defense

in the Buchenwald case. Morgen also testified at the Nuremberg

IMT in August 1946, before the Buchenwald case came to trial

at Dachau. At Nuremberg, Morgen testified on 7 August 1946 regarding

the conditions at Buchenwald. In response to a question from

the prosecutor at Nuremberg, Morgen had answered as follows:

Q. Did you gain the impression, and

at what time, that the concentration camps were places for the

extermination of human beings?

A. I did not gain this impression.

A concentration camp is not a place for the extermination of

human beings. I must say that my first visit to a concentration

camp, namely Weimar-Buchenwald, was a great surprise to me. The

camp was on wooded heights, with a wonderful view. The installations

were clean and freshly painted. There were grass and flowers.

The prisoners were healthy, normally fed, sun-tanned, working...

THE PRESIDENT of the Tribunal: When

are you speaking of? When are you speaking of?

A. I am speaking of the beginning

of my investigations in July, 1943.

Q. What crimes - you may continue

- please, be more brief.

A. The installations of the camp were

in good order, especially the hospital. The camp authorities,

under the Commandant Pister, aimed at providing the prisoners

with an existence worthy of human beings. They had regular mail

service. They had a large camp library, even with foreign books.

They had variety shows, motion pictures, sporting events. They

even had a brothel. Nearly all the other concentration camps

were similar to Buchenwald.

THE PRESIDENT: What was it they even

had?

A. A brothel.

Commandant

Hermann Pister

Execution

of Communist Commissars

Ilse

Koch - human lampshades

Dr.

Hans Eisele

Hans

Merbach

Sentences

of the guilty

Back to Dachau

Trials

Home

This page was last updated on September

16, 2009

Dachau TrialsUS vs. Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-PyrmontTrial of 31 war criminals from Buchenwald concentration campOn March 4, 1947, war crimes charges were brought against Hermann Pister, the Commandant of the Buchenwald concentration camp from 1942 to 1945, and 30 others associated with the camp. The proceedings against the 31 accused Buchenwald war criminals began on April 11, 1947, the second anniversary of the liberation of the camp by the 6th Armored Division of the US Third Army. The "Buchenwald trial" was held in a courtroom at the Dachau concentration camp complex; it was officially known as US vs. Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-Pyrmont, Case No. 000-50-5-9. Waldeck was an SS general and the highest ranking person among the accused.  Ilse Koch, the wife of former Buchenwald Commandant Karl Otto Koch, was the most famous of the 31 war criminals in the Buchenwald case. She was accused of having prisoners killed at Buchenwald and then having their tattooed skin removed to make human lamp shades. Among the accused was Hans Merbach, the SS soldier who had been in charge of the transport train on which around 5,000 Buchenwald inmates were transported to the Dachau concentration camp, and only about 25% of them survived the trip. This was the infamous Death Train which was discovered by the American liberators on the day that they liberated the Dachau concentration camp. The Nazi concentration camps had been declared to be a criminal enterprise by the Allies. Under the Allied concept of co-responsibility which was used in all the World War II war crimes trials, anyone who worked in one of the camps in any capacity was a war criminal. The 31 accused persons in the Buchenwald trial included at least one person who represented each job title in the camp. The relatively low number of Buchenwald war criminals might have been due to the fact that 76 of the SS staff members had been hunted down and killed by the inmates with the help of the American liberators. It was not a war crime for American soldiers to kill German POWs at that time because General Dwight D. Eisenhower had had the foresight in March 1945 to designate all future German POWs as Disarmed Enemy Forces in order to get around the rules of the Geneva Convention of 1929, which America had signed. The list of the 31 accused war criminals in the main Buchenwald case is as follows: Otto Barnewald  The charges against the 31 accused war criminals in the Buchenwald trial was that they had participated in a "common design" or a "common plan" to violate the Laws and Usages of War under the Hague Convention of 1907 and the Geneva Convention of 1929. These two conventions stated the rules of warfare pertaining to Enemy Prisoners of War. Buchenwald was not a prisoner of war camp, but in the proceedings of the American Military Tribunals at Dachau, the prisoners in the Nazi concentration camps were regarded as detainees who were entitled to the same treatment as POWs under the Geneva Convention of 1929. It was not until 1949, after all the Military Tribunals had been concluded, that a new Geneva Convention gave all detainees the same rights as POWs. In the photo below, a Russian Prisoner of War points an accusing finger at a German guard whom he claimed had abused him at the Buchenwald camp; this photo was taken on April 14, 1945, three days after the camp was liberated.  A panel of American military officers, guided by "law member" Lt. Col. John S. Dwinell, who made legal rulings, served as both judge and jury for the proceedings. The court president was Brig. Gen. Emil Charles Kiel. The accused were defended by American military officers, led by Captain Emmanuel Lewis, the chief defense counsel. Dr. Richard Wacker was one of the defense attorneys. The chief prosecutor was 34-year-old Lt. Col. William Denson, who had a conviction rate of 100% in similar proceedings against the staff members of the Dachau, Mauthausen, and Flossenbürg concentration camps.  Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-Pyrmont, the highest ranking prisoner among the accused, was an SS-Obergruppenführer and head of judicial matters in the district which included the city of Weimar and the Buchenwald camp. Waldeck was a member of the German royalty, who had joined the SS in 1929. He is shown in the photograph above, as he faced the Tribunal to hear his sentence of life in prison. His crime was that he had allowed Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, who reported directly to Hitler, to maintain a concentration camp at Buchenwald which was in his district. Waldeck was the one who blew the whistle on Buchenwald Commandant Karl Otto Koch in 1943 after he noticed the name of Dr. Walter Kramer on a list of political prisoners who had been executed on Koch's orders. By that time, Koch had been transferred to the Majdanek death camp in Poland, but his wife, Ilse, was still living at the Commandant's house in Buchenwald. Waldeck ordered a full scale investigation of the camp by Dr. Georg Konrad Morgen, an SS officer who was a judge in a German court. It was during this investigation that prisoners at Buchenwald told Dr. Morgen about the lampshades allegedly made from human skin. After American soldiers had liberated the Buchenwald camp, they were astounded when the Communist prisoners took them on a tour of the camp, showing them pieces of tattooed human skin, two shrunken heads, preserved human body parts, an ash tray made from a human bone, and a table lamp with a lampshade allegedly made from human skin. The shrunken heads resembled those made by primitive tribes in South America. A movie about the Buchenwald camp, directed by famed Hollywood director Billy Wilder, had been made by a film crew of the Signal Corps of the US Army shortly after the liberation of the camp; it included some footage of a display table. The photograph below is a still shot from the film which was shown during the proceedings at Dachau.  The proceedings against the 31 accused in the "Buchenwald trial" began with the showing of the film made by Billy Wilder. The defense objected, pointing out that the film had been made three or four days after the camp came under the control of the American Army, and that it did not show anything that had occurred prior to that time. The objection was overruled and the film was shown. The defense also objected to the display of the two shrunken heads, but this objection was also overruled. The narration in the film, as quoted by Joshua M. Greene, in his book "Justice at Dachau," is as follows: This is a pictorial record of the almost unprecedented crimes perpetrated by the Nazis at the Buchenwald concentration camp. In the official report, Buchenwald is termed an extermination factory, and the means of extermination: starvation complicated by hard work, abuse, beatings, tortures, incredibly crowded sleeping conditions, and sicknesses of all types. This is the body disposal plant. There inside are the ovens that gave the crematory a maximum disposal capacity of four hundred bodies per ten-hour day. The ovens are extremely modern in design, made by a firm that specialized in baking ovens. All bodies were finally reduced to bone ash. One of the first things that German civilians from neighboring Weimar see on a forced tour of the camp is the parchment display. A lampshade, made of human skin, made at the request of an SS officer's wife..." The SS officer's wife, who was mentioned in the film, was none other than Ilse Koch, the "Bitch of Buchenwald," and the wife of the former Commandant, Karl Otto Koch. Dr. Kurte Sitte, a 36-year-old doctor of Physics at Manchester University who had been a political prisoner at Buchenwald since September 1939, testified at the Buchenwald trial that a shrunken head, which he identified in the courtroom, was the head of a Polish prisoner who had been decapitated on the order of SS Doctor Mueller at Buchenwald. Although the prisoners in all the Nazi camps had their heads shaved, this Polish prisoner had long black hair at the time he was decapitated.  Defense attorney Capt. Emmanuel Lewis objected to the admission of the shrunken head into evidence because Dr. Mueller was not on trial, but his objection was overruled. Under the rules of the American Military Tribunals, any and all evidence was admissible, whether or not it pertained to the case, because the charges against all of the accused was participating in a "common plan" to commit war crimes. At the suggestion of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, a group of newspaper reporters and U.S. Congressmen were flown in from America; they were taken on a grand tour of the Buchenwald camp on April 24, 1945 and shown all the gory artifacts on the display table pictured above. Every major newspaper in America carried the story of how Ilse Koch, the wife of the Commandant, had imperiously ridden her chestnut stallion through the Buchenwald camp, selecting tattooed prisoners to be killed by her lover in order to make human lamp shades for her home. The nickname, "Bitch of Buchenwald," was given to Isle Koch by a reporter, and it soon became a household word in America. The public couldn't get enough of the lampshade story and the proceedings of the Military Tribunal at Dachau were sensationalized by the media. Film clips from the Buchenwald camp, with footage of the display table, were shown in the newsreels in every American theater. In the two years since the liberation of Buchenwald, Ilse Koch had already been convicted by the media. The Military Tribunal proceedings were filmed and every week, film clips were shown in the newsreels at the movie theaters in America. After the German Army surrendered to the Allies in May 1945, a total of 1,672 German war criminals were brought before a series of American Military Tribunals, held at the former Dachau concentration camp, between November 1945 and December 1947. These cases against staff members of the Nazi concentration camps were those in which the American military had jurisdiction by virtue of having been the liberators of the camps where the crimes had been committed. The authority for charging the defeated Germans with war crimes came from the London Agreement, signed on August 8, 1945 by the four winning countries: Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union and the USA. The basis for the proceedings of the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal against the accused German war criminals was Law Order No. 10, issued by the Allied Control Council, the governing body for Germany before the country was divided into East and West Germany. Law Order No. 10 defined Crimes against Peace, War Crimes, and Crimes against Humanity. A fourth crime category was membership in any organization, such as the Nazi party, the SS or the Gestapo, all of which were declared to be criminal under Law Order No. 10. In addition to the war crimes prosecuted by the Nuremberg IMT, Law Order No. 10 also gave the authority for each of the Allied countries to conduct trials of their own. The proceedings of the American Military Tribunals at Dachau were conducted according to "the rules and procedure" determined by the Zone Commander of the American Zone of occupation, as authorized by Law Order No. 10. The following quote is from Article III of Law Order No. 10: Article III 1. Each occupying authority, within its Zone of Occupation, [...] (d) shall have the right to cause all persons so arrested and charged, and not delivered to another authority as herein provided, or released, to be brought to trial before an appropriate tribunal. [...] 2. The tribunal by which persons charged with offenses hereunder shall be tried and the rules and procedure thereof shall be determined or designated by each Zone Commander for his respective Zone. Although commonly referred to as "trials," the proceedings at Dachau were technically not trials because the normal rules of court trials in America or Great Britain were not followed. Hearsay testimony was allowed and most of the prosecution witnesses were paid. Affidavits from witnesses were allowed, which meant that the defense had no opportunity to cross-examine the witness who had signed the affidavit. Interrogators questioned the accused before the proceedings began and established that they were guilty. The accused were not presumed to be innocent until proven guilty. The chief interrogator was 24-year-old Lt. Paul Guth, an American Jew who was born in Vienna and educated in England before emigrating to the United States. It was Guth's job to get confessions from the accused, who were then regarded as guilty until proven innocent. Many of the accused claimed that they had been beaten or tortured during their interrogation. The persons on trial were not called "defendants" because the burden of proof was on them, not on the prosecution as is customary in a court trial. All that was necessary, to prove that one of the accused war criminals was guilty of being part of a "common plan," was to prove that he had some association with the place where the crimes had been committed. The basis for the "common plan" concept of co-responsibility was Article II, paragraph 2 of Law Order No. 10 which stated as follows: 2. Any person without regard to nationality or the capacity in which he acted, is deemed to have committed a crime as defined in paragraph 1 of this Article, if he was (a) a principal or (b) was an accessory to the commission of any such crime or ordered or abetted the same or (c) took a consenting part therein or (d) was connected with plans or enterprises involving its commission or (e) was a member of any organization or group connected with the commission of any such crime or (f) with reference to paragraph 1 (a), if he held a high political, civil or military (including General Staff) position in Germany or in one of its Allies, co-belligerents or satellites or held high position in the financial, industrial or economic life of any such country. Under the rules of Article II, as quoted above, Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck-Pyrmont was charged with participating in a "common plan" to commit any or all of the alleged crimes at the Buchenwald concentration camp, even though he was not a member of the staff. Although there was testimony during the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal that prisoners had been killed in a gas chamber at Buchenwald, no one in the Buchenwald case was specifically charged with this crime. The accused were only charged with crimes against Allied nationals during the time that America was at war with Germany, and since the names of the prisoners who had allegedly been gassed at Buchenwald were unknown, the alleged gas chambers at Buchenwald were not mentioned in the Buchenwald trial. The room where Ilse Koch and other members of the Buchenwald staff were brought before an American military tribunal was in one of the buildings in the former Dachau concentration camp complex. Extra rows of seats had to be installed in the 200-foot-long courtroom to accommodate the crowd of photographers and reporters who flocked to see the "Bitch of Buchenwald." The accused war criminals who were awaiting trial were housed in the prison barracks of the former Dachau concentration camp. At the opening of the trial, the court president, Brig. Gen. Emil Charles Kiel, asked the defense counsel, "How do the accused plead?" To this, Captain Emmanuel Lewis replied: As chief defense counsel, I enter a plea of not guilty for all of the accused. Before we begin, if it please the court, there is a matter of great concern. The accused are charged with victimizing captured and unarmed citizens of the United States, and they seek to defend themselves against this charge. But despite our repeated requests, the prosecution has failed to furnish us with the name or whereabouts of even one single American victim. Lt. Col. William D. Denson, the chief prosecutor, replied: We are unfortunately unable to comply. The victims were last seen being carted into the crematories. From there they went up the chimney in smoke, and all the power of the United States and all the documents in Augsburg cannot tell us which way they went. We are sorry that we cannot furnish their whereabouts, but we fail to see that it is material whether one American or fifty thousand were incarcerated in Buchenwald. The crimes of these accused would be just as heinous. Contrary to Lt. Col. Denson's colorful story of what had happened to these American POWs, it is now known that, after about three months in Buchenwald, the Americans were rescued by a Luftwaffe General and transferred to Stalag III, a POW camp. The American prisoners at Buchenwald were members of a group of American Air Force pilots, who had been supplying the French resistance; they were captured after being shot down in France. Buchenwald was one of the main camps for French resistance fighters, and the pilots had been lumped in with captured French civilians who were fighting as insurgents. According to the Geneva Convention of 1929, it was a war crime to aid insurgents in a country that had signed an Armistice and promised to stop fighting. Technically, these pilots had violated the Geneva Convention by helping insurgents that were illegal combatants who had continued to fight after their country had surrendered. The defense motion to have the prosecution furnish the names of the Americans killed at Buchenwald was denied. In his opening statement in the Buchenwald proceedings, the chief prosecutor, Lt. Col. Denson, asked for the death penalty for each of the accused who was charged with participating in a "common design" to subject the inmates of Buchenwald to "killings, tortures, starvation, beatings, and other indignities." He had not asked for the death penalty for all of the accused in the Dachau, Mauthausen and Flossenbürg cases, but the Buchenwald crimes were much more heinous. The accused were charged with violations of the Geneva Convention of 1929 with respect to Soviet Prisoners of war, although the Soviet Union had not signed the Convention, and did not treat German POWs according to its laws during the war and for 10 years afterwards. Regarding the rules of the Geneva Convention of 1929 with respect to Soviet POWs, defense attorney Captain Lewis said: We think that the language of the Convention is simple and clear. It binds only those nations who sign it as between themselves. It is not binding as between a signatory and a nation that has refused to join the family of nations. In reply, Lt. Col. Denson said the following: I am perfectly ready, willing, and able to talk at this time of legality and of the law that is to be applied here. In Hall's Treatise on International Law, we have the following quotation: "More than necessary violence must not be used by a belligerent in all his relations with his enemy." The fact that Russia was not a signatory to the convention did not give Germans the right to mistreat Russian Prisoners of War. The Hague and Geneva Conventions were nothing more than a clarification of customs and usages already in practice among civilized nations. Buchenwald was the site of medical experiments carried out by doctors in the camp in an effort to find a vaccine for typhus, a disease which was devastating all the concentration camps. The Nazis claimed that the subjects of the experiments were condemned criminals who were prisoners in the camp. Bodies of prisoners who died after being forced to participate in the experiments were autopsied by the camp doctors and the internal organs were then preserved in formaldehyde in glass display cases. America had developed a typhus vaccine which had been sent to American POWs in Red Cross packages during the war. The Germans took great pains to deliver these packages, and consequently 96% of the American POWs in Germany survived their imprisonment, according to the Red Cross. The doctors in all the Nazi concentration camps delighted in studying and displaying medical oddities, such as human deformities. This was all part of their obsession with eugenics and their plan to breed a superior race. According to Dr. Johannes Neuhäusler, a Munich bishop who was a prisoner at Dachau, the Dachau concentration camp had a medical museum. He wrote in his book "What was it like in Dachau?" that "The museum containing plaster images of prisoners who were marked by bodily defects or particular characteristics was gladly visited by Hitler's officers." Given this proclivity for displaying medical curiosities, it is not at all surprising that the doctors at Buchenwald removed large sections of tattooed skin from dead prisoners and preserved it. In the photograph below, a Buchenwald prisoner shows preserved body organs to an American Jewish soldier.   One of the most famous inmates of Buchenwald was 43-year-old Dr. Eugen Kogon, an Austrian Social Democrat and political activist, who was a prisoner there from September 1939 to April 1945. Kogon was the main contributor to The Buchenwald Report, a 400-page book about the Buchenwald camp which was put together in only four weeks by the US Army, after conducting interviews with over 100 former prisoners at the camp. Kogon later wrote a book called "The Theory and Practice of Hell," which was a rewrite of the Buchenwald Report and one of the first books about the Nazi atrocities in the Buchenwald concentration camp. Kogon testified during the Dachau proceedings about the harsh treatment suffered by the prisoners at Buchenwald, although he was one of the privileged political prisoners who actually ran the camp. Kogon's testimony was contradicted by Dr. Georg Konrad Morgen who was the main witness for the defense in the Buchenwald case. Morgen also testified at the Nuremberg IMT in August 1946, before the Buchenwald case came to trial at Dachau. At Nuremberg, Morgen testified on 7 August 1946 regarding the conditions at Buchenwald. In response to a question from the prosecutor at Nuremberg, Morgen had answered as follows: Q. Did you gain the impression, and at what time, that the concentration camps were places for the extermination of human beings? A. I did not gain this impression. A concentration camp is not a place for the extermination of human beings. I must say that my first visit to a concentration camp, namely Weimar-Buchenwald, was a great surprise to me. The camp was on wooded heights, with a wonderful view. The installations were clean and freshly painted. There were grass and flowers. The prisoners were healthy, normally fed, sun-tanned, working... THE PRESIDENT of the Tribunal: When are you speaking of? When are you speaking of? A. I am speaking of the beginning of my investigations in July, 1943. Q. What crimes - you may continue - please, be more brief. A. The installations of the camp were in good order, especially the hospital. The camp authorities, under the Commandant Pister, aimed at providing the prisoners with an existence worthy of human beings. They had regular mail service. They had a large camp library, even with foreign books. They had variety shows, motion pictures, sporting events. They even had a brothel. Nearly all the other concentration camps were similar to Buchenwald. THE PRESIDENT: What was it they even had? A. A brothel. Commandant Hermann PisterExecution of Communist CommissarsIlse Koch - human lampshadesDr. Hans EiseleHans MerbachSentences of the guiltyBack to Dachau TrialsHomeThis page was last updated on September 16, 2009 |