(Page 2 of 2)

After the war she pursued work as an animator in Paris and was hired by the American who would become her husband, Art Babbitt. They married, moved to California and had two daughters. The Babbitts divorced in 1962, and Mrs. Babbitt returned to animation, working on characters like Tweety Bird, Wile E. Coyote and Cap’n Crunch.

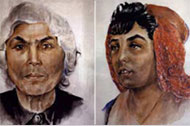

These are among the portraits owned by the Auschwitz museum. Josef Mengele wanted Dina Babbitt to document what he saw as Gypsy features.

Readers’ Opinions

In 1973 the Auschwitz museum told her that the watercolors had survived. The curators had determined that she was the artist by comparing her signature — “Dina 1944” — to the ones on artworks she had done shortly after the war for a book on the Holocaust.

The artist borrowed money to fly to Poland to authenticate the work, carrying a briefcase that she planned to use to take the watercolors home. When museum officials refused to give them to her, the long-running dispute began.

Negotiations seemed promising in the late 1990’s when Rabbi Baker and others tried to arrange compromises. Mrs. Babbitt rejected a suggestion that the museum lend the art to her for the remainder of her life; she said she wanted ownership and the right to hang the works in an American museum.

“She wanted all or nothing,” said Stuart E. Eizenstat, a former State Department official who mediated the talks. “I understood that, but in these kinds of claims, where you don’t have clarity in terms of legal doctrine, you have to work out these kinds of compromises.”

The Auschwitz museum has also wavered on compromise proposals; it was unwilling to give up just a portion of the works for fear of setting a precedent under which other survivors could claim additional artifacts on display.

“Nearly every item left or contributed to the museum in Auschwitz-Birkenau could be claimed by a rightful owner as personal property,” wrote the Polish ambassador to the United States in 2001, Przemyslaw Grudzinski, in a letter to Ms. Berkley. “Should they be returned?”

Ms. Berkley, one of Mrs. Babbitt’s strongest advocates, helped pass a resolution in 2002 that directed the State Department to work toward securing the paintings for Mrs. Babbitt. Ms. Berkley said in a telephone interview that she had also raised the issue with the president of Poland when she visited a few years ago.

“The Auschwitz museum has a lofty goal not to dismantle the museum,” she said. “I can relate to that. The Roma people have a stake in it because it’s their images. But to Dina, this is her life. This is the life of her mother.”

The museum insists that it respects Mrs. Babbitt’s position, informing her regularly about the status of the material and asking her permission whenever the works are to be reproduced or published. To Mrs. Babbitt, this is an acknowledgment that the museum recognizes that the works belong to her.

Displayed on an easel in her cottage is her attempt to repaint the Gypsy woman Celine as the young woman might have wanted to be painted — with longer hair and without her ear protruding from her scarf. But it’s not the same as having the original portrait.

“Every single thing, including our underwear, was taken away from us,” Mrs. Babbitt said. “Everything we owned, ever. My dog, our furniture, our clothes. And now, finally, something is found that I created, that belongs to me. And they refuse to give it to me. This is why I feel the same helplessness as I did then.”