Readers’ Opinions

FELTON, Calif. — At 83, Dina Gottliebova Babbitt still recalls the rickety easel where in 1944, under orders from the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele, she painted watercolors of the haggard faces of Gypsy prisoners.

But her memories of the Auschwitz concentration camp, vivid though they are, aren’t enough for Mrs. Babbitt. Seven of the 11 portraits that saved Mrs. Babbitt and her mother remain not far from where she created them, on display at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum in Poland.

“They are definitely my own paintings; they belong to me, my soul is in them, and without these paintings I wouldn’t be alive, my children and grandchildren wouldn’t be alive,” Mrs. Babbitt said with a Czech accent as she served schnitzel in her cottage here in the hills outside Santa Cruz. “I created them. Who else’s could they be?”

Her three-decade effort to retrieve them, which has stagnated for years, is drawing renewed interest this summer as a heart problem threatening Mrs. Babbitt’s health reinvigorates her supporters’ efforts to resolve the dispute.

Shelley Berkley, a Democratic representative of Nevada — Mrs. Babbitt’s daughter lives in Las Vegas — testified about the case in July at a Congressional hearing into the recovery of art stolen during World War II. And more recently a letter to the Auschwitz museum was signed by 13 artists, art dealers and museum curators, including a former executive director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“Reuniting Mrs. Babbitt with her paintings would be a sign of the museum’s dedication not only to history but also to humanity,” said the letter, which was organized by the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies in Philadelphia.

The Auschwitz museum, which considers the watercolors to be its property, has argued that they are rare artifacts and important evidence of the Nazi genocide, part of the cultural heritage of the world. Teresa Swiebocka, the museum’s deputy director, wrote by e-mail that the portraits “serve important documentary and educational functions as a part of the permanent exhibition” about the murder of thousands of Gypsy, or Roma, victims. The portraits, she added, “are on permanent exhibition, although they have to be rotated to preserve them, since they are watercolors on paper.”

She added that “we do not regard these as personal artistic creations but as documentary work done under direct orders from Dr. Mengele and carried out by the artist to ensure her survival.”

In a statement issued in 2001, she noted, the memorial’s international council asserted that six of the original watercolors had been purchased by the museum in 1963 from an Auschwitz survivor, and that the seventh was acquired in 1977.

Mrs. Babbitt’s case is unusual among the property disputes to emerge from the Holocaust because it involves artwork created under the duress of Nazis, not property confiscated by the Nazis.

“You have the natural dilemma between something that is clearly significant historical documentation of events and the claim of someone, which can’t be dismissed outright, that this was her creative work,” said Rabbi Andrew Baker of the American Jewish Committee, a lobbyist group, and a member of the International Auschwitz Council, which advises the museum. “I don’t know of a case quite like it.”

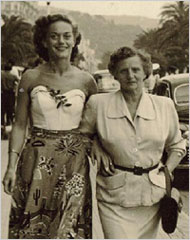

Dina Gottliebova was a 19-year-old art student in Prague in 1942 when she first went to a concentration camp. In September 1943 she and her mother, Johanna, were moved to Auschwitz, where she tried to cheer the imprisoned children by painting a mural of a Swiss mountainside and “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

The work drew the attention of Mengele, whose experiments sought scientific evidence to support Nazi racial theories. Frustrated that photographs did not accurately depict Gypsy skin tones, Mrs. Babbitt said, he wanted her to paint them.

Mengele singled her out, Mrs. Babbitt recalled, in March 1944, on a day when thousands of other prisoners were being taken to be exterminated. She said that she demanded of Mengele that he also spare her mother or she would commit suicide by touching an electrified fence. She and her mother were among the 27 Czechoslovak Jews to survive from their group of more than 5,000.

Her first subject was a Gypsy woman named Celine, who had recently lost her newborn to starvation. Celine is shown with a scarf covering her shaved head and one ear protruding, Mrs. Babbitt said, because Mengele linked the shape of Gypsy ears to inferiority.

After two months of painting — she believes that she did 11 portraits — all of the camp’s Gypsies were killed. Then she was forced to paint medical procedures for Mengele.

Mrs. Babbitt and her mother survived internment in two more concentration camps before liberation in May 1945.