Such men as come Proud, open-eyed

and laughing to the tomb.—William Butler Yeats

"Doo-do-n'doo—doo-n'doo-doo—"

"—Run-run—"

I cracked an eyelid and peered blearily at the offending clock-radio. Snippets of thought began to daisy-chain into coherent memory.

Eight twenty-two.

Sundown.

Time to rise and shine.

The music became more insistent: Sedaka, Elton John; duet. I moaned, lifting a sleep-numbed arm as they chorused: " . . . Bad blood! Talkin' 'bout bad blood. . . ."

My hand closed on the clock's plastic case, ignoring the off and snooze buttons.

Neil Sedaka belted: "Bad!"

"Ba-ad!" echoed Elton John.

"Blood!" wailed Neil.

Elton never got the chance to follow through as the clock-radio arced across the bedroom to a termination point against the far wall. Whatever course the disease might be taking, it had yet to affect my reflexes. I groaned out of bed, shrugged into my robe, and began the evening rounds and rituals.

The house was a split-level arrangement with the downstairs rec room serving as my present sleeping quarters. After opening the heavy curtains to the pale remnants of fading sunlight, I started up the stairs for the kitchen.

Halfway up, I did postal calisthenics, retrieving a spill of mail beneath the brass-flapped slot in the front door. Out of a dozen pieces only three were properly addressed to Mr. Christopher L. Csejthe. One was from the insurance company, and the name was probably the only detail they'd managed to get right in the past year. The rest employed a variety of creative misspellings including one designated for "ocupant" on a dot-matrixed label. So much for computerized spell-checking.

I resisted the urge to lay the envelopes out on the dining room table like a tarot reading—I see a tall, dark bill collector in your future—tossed the junk mail aside, and carried the rest into the kitchen. Turned on the radio and began filling the teakettle with tap water.

The graveyard shift makes it easy to disconnect. You sleep while the rest of the world works, plays, lives. Then you rise and go forth while everyone else is in bed, dead to the world. The nightly newscast was my daily ritual for reconnecting. Plus, keeping tabs on the competition is de rigueur, when you work in radio.

I set the kettle on the stove to boil, thumbed through the envelopes that obviously contained bills and then, believing you start with the bad news first, opened the one from the insurance company. I expected an argument over last month's billing for lab tests and blood work. Instead, there were two checks inside, both made payable to me: one for twenty-five thousand dollars, the other for ten thousand.

It had taken almost a full year, but they had finally gotten around to rewarding me for killing my wife and daughter.

The tiled bathroom walls amplified the rattlesnake clatter of the shower, smothering the best efforts of the radio just outside the bathroom door. Muffled music gave way to mumbled talk. By the time I reached for my towel, the newscast was five minutes along.

I hadn't missed much; the lead story was the national economy. Again. Congress still hadn't figured out that it was fiscal madness to spend more money than it was taking in every year.

I brushed my teeth as world and national events gave way to regional and local news.

New reports of cattle mutilations a couple of counties to the north. And, between there and here, a couple of people had disappeared in Linn and Bourbon counties. Any day now the local news outlets would start running a short series on UFOs or Satanists. Oboy.

Tonight's icing on the cake: a mysterious murder just across the Missouri state line but considerably closer to home. An orderly had turned up murdered on the night-shift at St. Peter's Regional Medical Center. The Joplin copshop was tight-lipped (as usual) but rumors were circulating that the remains were found "filed" in various parts of the hospital records room.

The news ended with the announcer observing that while no motive or suspects had been established, yet, last night was the first night of the full moon.

Nyuck, nyuck.

Well, actually, it wasn't that facetious a sign-off. The Midwest seems relatively benign to most of the big-city Coasters, but we make up for our lack of urban angst and high crime rates by occasionally producing monsters that make Dave Berkowitz and Jeff Dahmer look like the Hardy Boys. Come to think of it, Dahmer was one of ours as well.

Southeast Kansas has a particularly ghoulish history with more than its share of bloodbaths, hauntings, and just plain weirdness. They run the gamut from the Marais des Cygnes massacre to the Bloody Benders of the pioneer days to the purported hauntings of the Lightning Creek bridge, the ghost in Pitt State's McCray Hall, and the stories that linger amid the crumbled remains of the old Greenbush church. Even today those big, empty fields by day aren't always so empty by night. Nope, when the news ends with unusual and unexplained death, the observation of lunar phenomena, and the exhortation to lock your doors and windows, you'd better listen up, friends and neighbors; it's a good night to stay indoors and clean and oil your guns. And listen to Yours Truly on the radio.

Shaving was never the high point of my evening ablutions and, lately, it had become a major nuisance. In spite of slamming 150 watters into the bathroom fixtures, it was getting harder and harder to see what I was doing with the razor. I'd heard of the wasting effect of certain illnesses but, with each passing day, my own reflection seemed to fade before my own eyes.

"To be or not to be," I murmured, peering into the uncooperative mirror. What else had the Bard penned? O! that this too too solid flesh would melt, thaw and resolve itself into a dew. . . .

Hamlet was a butthead.

Tonight I decided "hell with it" and made the three-day-old beard official. Additional UV protection, I figured. I wouldn't miss my face in the mirror. Dark hair, dark eyes, a slight Slavic caste to otherwise bland features: it was not the kind of face that distinguished its owner in any definable way. Why Jenny had ever given me a second look—

I threw my razor across the bathroom and stalked back into the bedroom. It was shaping up into a good night for throwing things.

Questions, I coached myself, staggering into a pair of white chinos and a tan short sleeve shirt: Is my eyesight affected? Will I eventually go blind? Is it treatable?

Is it terminal?

I pulled on a pair of white canvas deck shoes.

Oh hell, let's cut to the chase: have I got AIDS, Doc?

The mirror might play tricks on me, but there was no problem in reading the bathroom scales: I was still losing weight. Which wasn't hard to figure. Since my appetite had deserted me, I'd managed a dozen meals over the past two weeks.

What are you hungry for when you don't know what you're hungry for?

Nothing on a Ritz.

After dark it's only a fifteen-minute drive from one end of Pittsburg, Kansas, to the other.

The population sign boasts 30,000, but the downtown area is condensed into a couple of miles of main street that fronts about eighty percent of the city's shops and stores. The old façades reflect the central European culture from the boomtown coal mining days of nearly a century ago. Today, aside from some manufacturing and a dog track north of town, most of the local economy is tied to agriculture and Pittsburg State University. The mines have long since played out.

The main drag runs north and south. Homes sprawl for miles in all directions but, once you've gone more than four blocks, either east or west, the houses disperse like boxy children in a wide-ranging game of rural hide-and-seek.

So getting from one end of the town proper to the other is relatively quick and simple. Especially after eight p.m. when they roll up the sidewalks.

This particular night, however, the trip to the hospital seemed interminable. Marsh's voice on my answering machine had promised "some answers," but his tone sounded just as bewildered as when he had run the first batch of tests nearly three months ago.

I glanced over at the three books stacked beside me on the passenger seat: Whitman's Leaves of Grass, Tuchman's A Distant Mirror, and Jung's Man and His Symbols.

How much time, Doc?

Maybe I should have picked up something from the Reader's Digest Book Club, instead.

I checked my watch in the Mount Horeb Hospital parking lot: close to an hour before I was due at the radio station. Time enough for "some answers."

But enough time for the answer I dreaded most? And the one that loomed right behind it: will my insurance cover the treatments?

Tough call.

Total your car and your insurance agent consults the Blue Book like it was holy writ. Not so simple when you total a seven-year-old girl and her mother. Some asshole behind a desk at the home office wanted to dither over revised actuarial tables and adjust the compensatory payout schedule. Did he think I was going to cut a special deal with the coroner? Maybe fake a funeral while I took them down to some arcane body shop and got them up and running, again? Jesus.

So what kind of investment are they going to see in spending tens of thousands of dollars on dead-end treatments for moi that would probably just delay the inevitable for a few more months?

I walked across the parking lot, empty and empty-handed; nothing left to throw.

The emergency room was as silent as a tomb.

Whoa, scratch that allusion. . . .

Besides, there was a faint whisper of background noise, muffled sounds that put one in mind of a high-tech fish tank. Aging fluorescents added to the aquarium effect, but the waiting room was empty, as if some giant ichthyologist had netted it out preemptory to a water change. The lone receptionist surfaced from her computer terminal just long enough to direct me down the corridor with a desultory wave, then submerged again without a single word being spoken. I walked the length of the corridor, feeling my feet drag as if encased in a deep-sea diver's leaden boots.

Dr. Donald Marsh, third-year resident, was waiting for me at the second treatment station. Fair of skin, the only contrast to his green-bleached-to-white surgical scrubs was his buzz-cut orange hair and a dusting of freckles. Picture the Pillsbury Doughboy sprinkled with cinnamon.

I didn't recognize the short, broad-faced woman standing on the other side of the treatment table. Her white lab coat was a sharper contrast to her nut-brown face and hands. Her black hair was braided, curving around and dropping down across her right shoulder like spun obsidian.

Don smiled as I approached. The woman didn't, glanced down at a clipboard. Looked back up at me.

"Chris . . ." Marsh's firm hand enveloped mine, didn't squeeze. " . . . how're you feeling?"

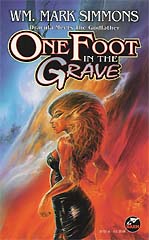

"Like I've got one foot in the grave and the other on a banana peel," I said, trying for the light touch. It almost came off.

Marsh looked uncomfortable. With each examination I had watched that look move across his features like lengthening shadows on an old sundial. Now I studied his face for new shadings but saw nothing beyond fresh uncertainty in his eyes.

"You still don't know." Logic followed on the heels of disappointment: "It's not AIDS, then?"

Marsh shook his head. "We know that much."

"So what else do we know?"

"We know you haven't been taking sulfanilamide or any other drugs known to produce photosensitivity as a side effect," he said. "The blood tests have ruled out eosin, rose bengal, hematoporphyrin, phylloerythrin, and other known photodynamic substances in your bloodstream. And I'm pretty damn sure you haven't been ingesting plants with photoreactive pigments like Hypericum, geeldikkop, and buckwheat."

"Buckwheat?"

"In extreme situations it can cause fagopyrism. But I've never heard of a case in humans and what you have is nothing like fagopyrism."

I'd grown weary of asking Marsh to stop speaking in tongues. "So what is it like?"

"Porphyria," the woman answered unexpectedly.

"Excuse me?"

Marsh cleared his throat. "I promised you results on the last batch of tests we ran. Well. I guess you might say the main result is Dr. Mooncloud."

She smiled suddenly and extended a small, brown hand. "Taj Mooncloud, Mr. Csejthe." My surname came out sounding like a sneeze.

Taj?

"My father was a Native American," she explained as if I'd voiced the question, "my mother, East Indian."

Interesting. I took her hand across the gurney. "Pleased," I said. "My great-great grandfather was Rumanian: it's pronounced 'Chey-tay.' "

"Do forgive me."

"No offense taken," I said, patiently two-stepping the dance of etiquette. "You were saying something about my condition?"

"Ah, yes." The businesslike demeanor was back. "I have an interest in certain types of blood disorders and I've arranged for most of the major labs to flag my computer when something unusual comes in for testing. Your blood samples hold a particular interest for me."

"How nice."

"Let's see. Christopher L. Csejthe: Caucasian, male, thirty-two years of age," she read from the clipboard. "No significant history of disease in either personal or family medical records. Military records are curiously incomplete. . . ."

Which meant that she had the edited version. And she shouldn't have had even that.

"Marital blood tests registered no anomalies as of nine years ago."

I glanced down at the white band of flesh circling the base of my ring finger. Almost a year, now, and still refusing to tan. . . .

"Could I have picked something up while I was in the service? Some exotic bug or exposure to chemical—"

Marsh glanced over Mooncloud's shoulder and shook his head. "That was over a decade ago, wasn't it? Even such diverse hazards as malaria or sand flies or Agent Orange have warning symptoms that kick in much sooner."

"How long have you been working in radio?" Mooncloud asked.

It was my turn to shake my head. "If you're wondering about exposure to RF radiation, Doc, it's a dead end. I didn't start my current profession until this thing—whatever it is—necessitated my taking night work. Before that I taught English Lit. Eight years. Exposure to radical ideas comes with the territory but I doubt that's the causative agent here."

Mooncloud consulted the second page on her clipboard: "Patient first complained of sensitivity to light eight months ago. Shortly thereafter the formation of epidermal carcinomas necessitated avoidance of all exposure to ultravi—"

"I am familiar with my own medical history, Doctor; the treatments for skin cancer and subsequent diagnosis of pernicious anemia." My temper was frayed like an old rope that had been stretched too far, too long. "A moment ago you used a word I haven't heard before."

"Porphyria."

"That's the one."

"It's a genetic disorder," Marsh explained, "a hereditary disease that affects the blood. Porphyria causes the body to fail to produce one of the enzymes necessary to make heme, the red pigment in your hemoglobin. You're gonna love this—" he grinned wryly "— it's the vampire disease."

I must have goggled a bit. "The what?"

"The vampire disease. At least that's what the tabloids have dubbed it."

I scowled: I was not amused by the idea of a "vampire disease" and any connection to the tabloids was something I liked even less.

Marsh looked to Mooncloud for help, but she was preoccupied with her clipboard. "There was a paper done back in eighty-five by a Canadian chemist named David Dolphin," he said. "He hypothesized that porphyria could have been the basis for some of the medieval legends of vampires and werewolves." He held up a finger. "Extreme sensitivity to light: the most common symptom."

I shook my head. "And vampires can't stand sunlight, right? Give me a br—"

"It's more than that, Chris. Some porphyria victims are so sensitive to sunlight that their skin becomes damaged and, in extreme cases, lose their noses and ears—fingers, too. In other cases, hair may grow on the exposed skin."

"Werewolves," I muttered.

Marsh added a second finger to the first. "Another symptom is the shriveling of the gums and the lips may be drawn tautly, as well, giving the teeth a fanglike appearance."

"Great. Anything else?"

"Well, although it remains incurable, we have a few options in terms of treatment, now. But back in the Middle Ages there was just one way to survive. To fulfill your body's requirements for heme, you had to ingest—drink—large quantities of blood."

I stared at Marsh. "Nice. How about garlic and crosses?"

He shrugged. "I don't know anything about the religious angle, but garlic is a definite no-no."

"Really."

"Stimulates heme production. Which can turn a mild case of porphyria into an extremely painful one."

"And you're telling me I have this 'porphyria disease'?"

"No," Mooncloud said. "You asked what your symptoms were like. I said 'porphyria'—which they are. Like. But porphyria is a genetic disorder and tends to be hereditary."

"Which is why all that inbreeding during the Middle Ages produced pockets of it," Marsh said.

"But since there's no record of it in your family history," Mooncloud continued, "it seems unlikely. Particularly since it's shown up rather late in life for a genetic condition. Which also rules out hydroa and xeroderma pigmentosum. But I won't rule it out until we've run a full spectrum of genetic tests. Maybe they can tell us what the blood tests didn't."

"Okay." I felt my temper ease back a couple of notches. "Let's get started."

"Not here," Mooncloud said.

"Then where?"

"Washington."

"D.C.?"

She shook her head. "Seattle."

"Tomorrow should see mostly sunny skies with highs in the upper eighties. Currently, it's seventy-three degrees under mostly cloudy skies and although the lunar signs are less than auspicious, I'd give little credence to them. . . ." I tapped a button and then closed the microphone as Creedence Clearwater Revival launched into "Bad Moon Rising."

"Clever." Mooncloud had doffed her lab coat and was wearing a sleeveless shirt of blue cotton and tan slacks. Beaded moccasins completed the ensemble.

I shrugged. "Radio—it's what the teeming millions demand and expect."

"Teeming millions? In southeast Kansas?"

"Teeming thousands," I corrected.

"At one o'clock in the morning?"

"Hundreds. Teeming hundreds."

She arched an eyebrow. "How about teeming dozens. . . ." It wasn't a question.

"Hey, it's a job—with benefits and insurance. Something I can't afford to walk away from with a preexisting condition like this." I sorted through stacks of compact disks for my next piece of music.

"All the insurance in the world isn't going to help you if the doctors don't understand what they're treating."

I stopped and leaned across a pair of dusty turntables. "Dr. Mooncloud . . . I appreciate the fact that you traveled all the way to Pittsburg, Kansas, to meet me and review my case. I suppose I should be flattered as hell that you've followed me to work and are sitting here in an empty building in the wee hours of the morning to try to offer me a special treatment program. Most doctors won't even make house calls."

"I am not most doctors, Mr. Csejthe." Her smile was pure Mona Lisa. "And you are not most patients."

"Patience and I seem to be mutually exclusive these days," I said. "Can you guarantee me a cure if I come to Seattle?"

"A cure? Only God guarantees cures and He's a notoriously reluctant prognosticator. I can guarantee you a medical research team with experience in your kind of malady and a strong interest in your particular case. It won't cost you a thing and I can guarantee you a job in the Seattle area—"

"I've already got a job right here. And working the night shift is perfect when your skin suddenly develops an allergy to sunlight."

There was a muffled thump and the lights suddenly went out. The studio was an interior room with no windows to the outside: the darkness was sudden and complete. As was the silence. C.C.R. had gotten as far as "don't go out tonight," quitting as if someone had yanked amp and mike cords in perfect unison.

Then the emergency lighting kicked in like flashlights of the gods, amplifying the shadows in Mooncloud's frown to intimidating proportions. "What's wrong? What happened?"

"Gremlins." Surprise eclipsed annoyance as I watched this professional woman—who had just spent the last forty minutes speaking of medical matters that bordered on twenty-first century science—make the same gesture my grandmother had used to ward off the "evil eye."

"A bird, actually," I said, pulling the phone over and flipping through the pad of emergency numbers. "There's a place on the utility pole, just thirty feet from the building, where the power lines junction with a transformer. When a bird picks that particular spot to roost: zap! One fried feathered friend and one powerless public radio station."

"You don't have a backup generator?"

"Darlin'," I drawled, "this is Kansas and we're public radio." I fumbled the receiver to my ear and began punching out a series of numbers on the keypad. "We just call the power company and they send a guy over with a long pole who resets the circuit breaker—" I stopped, listening to the silence as I pushed the buttons. Breaking the assumed connection, I listened for a dial tone.

"What sort of bird would roost at one in the morning?" she asked, making the gesture again.

I smacked the receiver back into the cradle with a sigh. "Phone's dead."

The emergency lights flickered. And, inexplicably, went out.

"Um, they can't do that," I announced to no one in particular. The emergency lights were on individual battery sources: even if it were remotely possible for one to go out that quickly, they all wouldn't fail at the same time.

Ignoring the rules of probability, the emergency lights remained off-line, preferring some variant of the chaos theory, instead.

"From ghosties and ghoulies and long-leggity beasties," Mooncloud whispered.

"Nocturnal volleyball teams." I groped my way across the room in the darkness.

"I beg your pardon?" I would have sworn that the disoriented quality in her voice was not entirely due to the sudden blackout.

"Things that go 'bump' in the night."

"Marsh warned me about you," she said.

"Yeah? What did he say?"

"That I could look up 'attitude' in the dictionary and find your picture."

I bit back a curse as I barked my shin on a tape console that had been moved out of its place for servicing.

"That you?"

"Of course it's me!" I was trying to keep my temper from erasing my mental map of the studio's layout. "The building's locked up tighter than a drum. Who else would it be?"

There was another sound, then, from the other end of the building. It took a moment to place it: the rattling of a metal security grate. "I stand corrected—someone must have left a door unlocked."

"Is there a back door?" Mooncloud's voice was decidedly unsteady.

"Doctor, there's no need to panic. It's probably one of the campus security guards checking the building. We'll just sit here until the power is restored—"

The security grating rattled again.

And then it screamed.

The sound of rending metal groaned and shrieked, echoing down the hallway like a slow-motion freight train braking in a tunnel. I fumbled for Mooncloud's hand in the darkness, aiming for the luminous dial of her watch. "The back door's this way, Doc. Last one out's—"

"I know," she said grimly. "Far better than you, in fact."

I led her around the consoles and fumbled open the sliding glass door that led to the engineering section. Groping across a bank of demodulators and telemetry panels, we maneuvered through the stacks of equipment toward the back door. A workbench caught my hip, bruising it and turning us around so that I was disoriented for a moment.

"Hurry," she whispered.

"A moment," I hissed, waving my free arm around in search of a blind man's landmark. I suddenly realized that the exit door was before me, a vague, grey rectangle in the deeper blackness. Glancing back over my shoulder, I saw a dim glow through the tiny window inset in the main studio's outer door.

"Don't look back!" Mooncloud shouted, pushing at my shoulder. "Go! Go!"

The glow was mesmerizing, intensifying, but I turned my attention to the fire door in front of us. I slapped the crash-bar but the door would not budge.

"Break it down."

"What?"

"Break it down!" she insisted.

I was going to say something about the weight and immovability of a fire door, but the sound of exploding glass from the main studio derailed that train of thought. I whirled and kicked the door just above the bar: the metal panel buckled and the door erupted out of its frame, sailed over the concrete porch and steps, and went surfing across the rear parking lot.

Outside, the night seemed preternaturally bright despite the fact that the streetlights that normally illuminated the north end of the campus were dark. A van—no, one of those mobile homes on wheels—was swinging around a concrete median and heading right for us. It didn't seem to be traveling all that fast, which was fortunate as the driver had neglected to switch on his headlamps.

Dr. Mooncloud was also moving in slow motion, looking somewhat like Lindsay Wagner in a grainy rerun of The Bionic Woman. It felt as if Time, itself, had perceptibly tapped its own fourth-dimensional brakes. I had to make a conscious effort to linger, just to keep from leaving her behind.

As I slowed, Dr. Mooncloud seemed to speed up, her left hand withdrawing a hip flask from the pocket of her windbreaker. The RV was braking to a stop just ten feet away and, as she began a slow turn on the ball of her foot, another woman jumped out of the driver's side of the vehicle. The driver closed the distance between us at an amazing speed and I was only able to catch random impressions: long, dark hair, though not as black as Dr. Mooncloud's. Tall, athletic; she wore Nikes, blue jeans, and a tank-top that revealed arms like carved cherry wood. As she reached the foot of the steps, I could see that she was carrying a crossbow. . . .

And suddenly everything seemed to snap back into realtime.

"How many?" the driver bellowed, bounding up the stairs.

"One." Mooncloud turned back to face the doorway we had just passed through. "I only detected one."

"Get in the van," the driver ordered, shouldering her way between us. "Give me fifty and then haul ass whether I'm back or not."

"Soon as I seal the door." Mooncloud unstopped the flask and, as the newcomer disappeared through the doorway, poured the contents across the threshold. She took special care to form a solid, unbroken stream from post to post and then stuffed it back in her jacket. "Come on!" She took me by the arm.

"What?"

"Get in the camper!"

"Camper?" I was still thinking in slow motion.

She yanked me down the stairs and shoved me toward the recreational vehicle. "Now!"

"I can't abandon the station! The FCC—"

A scream sliced the night air—an animal sound as far removed from a human voice as the previous scream of tortured metal. It was a sound that went on and on as we hurried toward the RV. Mooncloud yanked the passenger door open and then ran around to the driver's side as I climbed up onto the bench seat. As she slid behind the wheel the other woman leapt from the building's rear doorway, sailing over the stairs and landing on the ground below. As she crouched on the asphalt, there was a shattering roar that canceled out the screaming. A ball of flame rolled out from the doorway like an orange party favor, licking the air just a few feet above her head.

Mooncloud threw the van in gear and brought it skidding around as the blaze snapped back through the opening.

Before I could reach for the door handle the woman was springing through the open window to land across my lap.

"Go!" she shouted, but Mooncloud was already whipping the vehicle in a tight turn and accelerating toward the parking lot's north exit. The speed bump smacked my head against the roof of the cab. By the time my vision cleared, we were driving more sedately down a side street, the woman with the crossbow sitting between me and the passenger door. In the rearview mirror a pillar of flame was climbing from the roof of the old dormitory that housed the radio station.

I shook my head to clear away the last of the planetarium show and gripped the dashboard. "Will somebody please tell me what's going on?"

"It's very simple, Mr. Csejthe," Dr. Mooncloud said, pressing a button that locked the cab doors. "You are a dead man."