Before

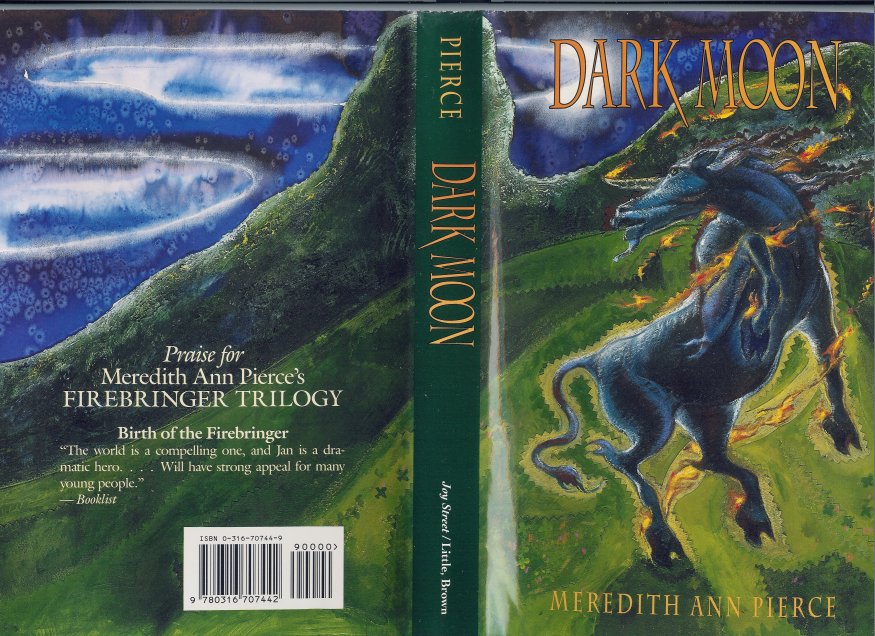

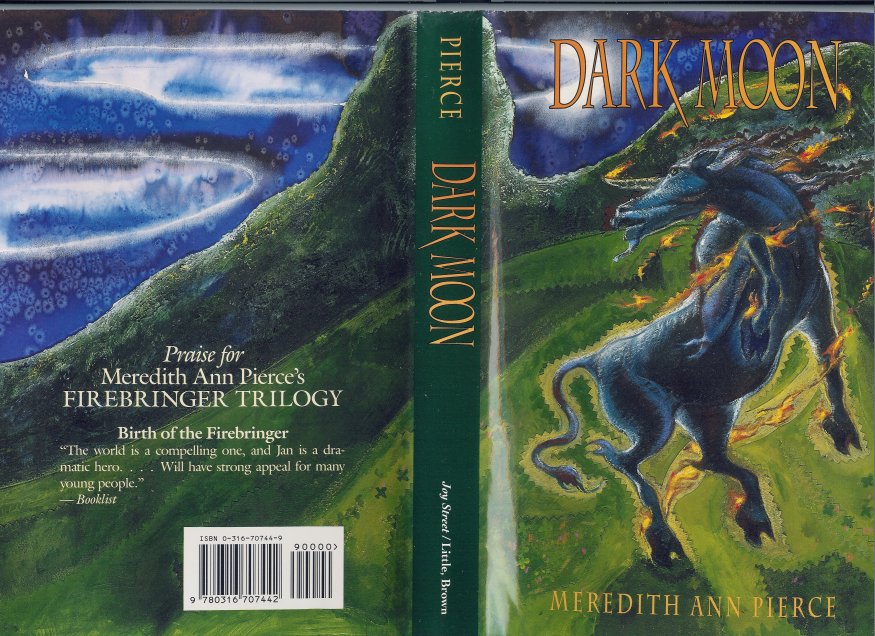

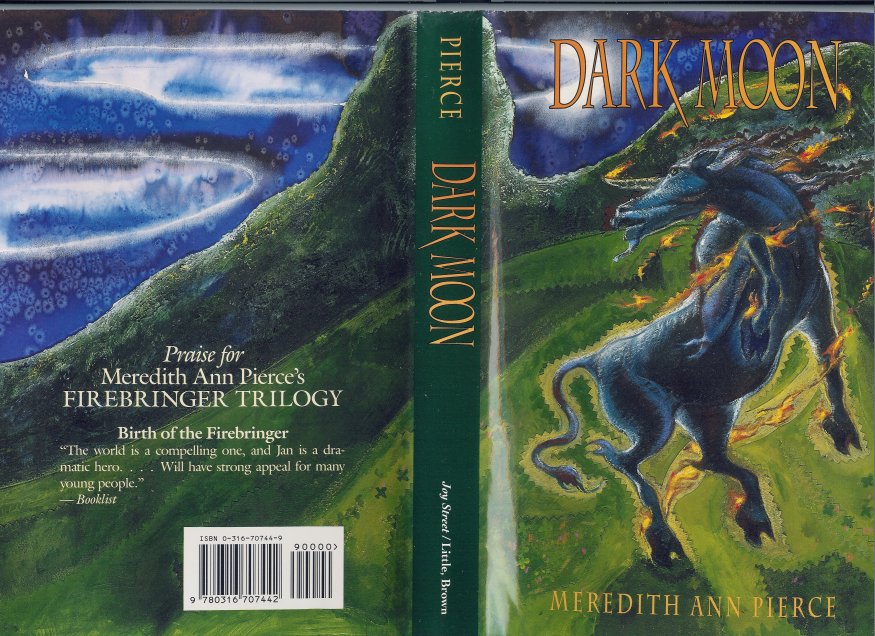

He was the youngest prince the unicorns had ever known, and his name meant Dark Moon. Aljan son-of-Korr was swart as the well of a weasel’s eye, the night-dark son of a night-dark sire, with keen, cloven hooves and a lithe, dancer’s frame, a long horn sharper than any thorn, and a mane like black cornsilk blowing. While still counted among the colts, young Jan had won himself a place in the Ring of Warriors. Upon the death of his royal grandsire, Jan had seen his own father declared the king and himself—barely half-grown—made battle-prince.

During time of peace, Korr the king would have ruled the herd, but because the unicorns considered themselves at war, it was to Jan, their prince, that the Law gave leadership. His people’s bitterest enemies, the wyverns, dwelt far to the north, in sacred hills stolen from the unicorns many generations past. Vengeful gryphons held the eastern south, barely a day’s flight from the great Vale in which the exiled herd now made its home. And hostile goat-footed pans inhabited the dense woodlands bordering the Vale.

Such were the uneasy times during which this young prince came to power. I am his chronicler, and yestereve I spoke of his warrior’s initiation, during which the goddess Alma marked him, tracing a slim silver crescent upon his brow and setting a white star on one heel in token that one day he must become her Firebringer, long prophesied to end his people’s exile and lead them triumphant back to the Hallow Hills.

Tonight, I resume my tale little more than a year after Jan’s accession: it was the afternoon of Summer’s Eve. The morrow would be Solstice Day, when thriving spring verged into summer. Jan stood on a lookout knoll high above the Vale, rump to the rolling valley below, black eyes scanning the Pan Woods spilling green-dark to the far horizon, beyond which the Gryphon Mountains rose, flanking the Summer Sea.

1.

Solstice

Cloudless sky soared overhead, blue as the sweep of a gryphon’s wing. Breeze snuffed and gusted through the dark unicorn’s mane, warm with the scent of cedars sprawling the slope below. Sun hung westering. Jan shifted one cloven heel and sighed. He was not on watch—no sentries needed this time of year: gryphons never raided past first spring. But the herd’s losses had been heavy that season in fillies and foals carried off by formels—the great blue gryphon females—to feed their ravenous newly hatched young.

Brooding, the prince of the unicorns surveyed the folds of the Pan Woods before him. It was not the number of recent raids which troubled him most, but their manner. Always in springs past, wingcats had come singly, at most in mated pairs. This year, though, many of the raids had included more than two gryphons. A few had even consisted solely of tercels—male gryphons—no female at all. Jan snorted: clearly at least some of the spring’s forays had had little to do with a formel’s need to feed her chicks.

“Alma,” the young prince whispered, and the wind stole the name of the goddess from his teeth. “Alma, tell me what I must do to defend my people.”

Only silence replied. Jan’s skin twitched. With his long flywhisk tail, he lashed at the sweatsipper that had alighted on his withers. Vivid memory came to him of how, only the year before, the goddess had marked him with fire, granted him the barest glimpse of his destiny—and spoken not a word to him since. Standing alone on the lookout knoll, he felt doubt chill him to the bone. He wondered now if the voice of Alma and her vision had been nothing but a dream.

A twig snapped in the undergrowth behind him. Jan wheeled to spot a half-grown warrior emerging from the trees. Pale dusty yellow with dapples of grey, the other shook himself, head up, horn high. Jan backed and sidled. Like a fiercely burning eye, the copper sun floated closer to the distant horizon. The other snorted, ramped, then whistled a challenge, and the prince sprang to meet him. Horns clattered in the stillness as they fenced. A few more furious strokes, then the pair of them broke off. Jan tossed his head. Grinning, the dappled half-grown shouldered against him. The prince eyed his battle-companion Dagg.

“Peace!” Dagg panted. “What brings you brooding up onto the steeps so close to dusk?“

Jan shook himself and nickered, not happily.

“Gryphons.”

Again his shoulder-friend snorted, as though the very thought of gryphons stank.

“Bad weather to them,” Dagg muttered. “Broken wings and ill fortune—praise Alma spring’s past now and we’re done with them for another year.”

Jan nodded, champing. Dusk wind lifted the long forelock out of his eyes, exposing the thin silver crescent upon his brow. Gloomily, he picked at the pine-straw underhoof with his white-starred hind heel. Beside him, Dagg shifted, favoring one foreleg.

“How’s your shank?” Jan asked him.

The dappled warrior blinked grey mane from his eyes and slapped at a humming gnat ghosting one flank. He flexed the joint.

“Stiff yet, but the break’s well knit. Teki the healer knows his craft.”

Behind them, the Gryphon Mountains stood misty with distance. The reddened sun above the Pan Woods had nearly touched the rim of the world. Lightly, Jan nipped his shoulder-friend.

“Come,” he told him. “Sun’s fair down.”

Dagg shook him off and fell in alongside as they started through the evergreens that forested the Vale’s inner slopes. Amber sunlight streamed through the canopy. Just ahead, a pied form moved among the treeboles. Jan halted, startled, felt Dagg beside him half shy. A moment later, he recognized the young warrior mare Tek. Her oddly patterned coat, pale rose and black, blended into the long, many-stranded shadows.

“Ho, prince,” she called, “and Dagg, make haste! Moondance begins.”

Jan bounded forward with a glad shout, reaching to nip at the pied mare’s neck, but light as a deer, she dodged away. Tek nickered, shook her mane, back-stepping, laughing still. The young prince snorted, pawing the ground. The next instant, he charged. This time, the pied mare reared to meet him, and the two of them smote at one another with their forehooves, like colts. Tek was a lithe, strapping mare, strong-built but lean, a year Jan’s senior—though the young prince was at last catching up to his mentor in size. They were of a common height and heft now, very evenly matched. He loved the quickness of her, her sleek, slim energy parrying his every lunge and pressing him hard. With Tek, he need never hold back.

“So, prince,” she taunted, feinting and thrusting. The clash of their horns reverberated in the dusky stillness. “Is this the best my pupil can do? Fence so lackadaisical this summer by the Sea and you’ll never win a mate!”

Jan locked his teeth, redoubled his efforts. On the morrow, he knew, he, Tek, and Dagg—and all the other unpaired young warriors—must depart upon their yearly trek to the Summer shore, there to laze and court and spar till season’s turn at equinox, when most would pledge their mates before the journey home.

Tek clipped and pricked him. Jan glimpsed Dagg standing off, absently scrubbing a flybite against the rough bark of a fir, and whistled his shoulder-friend to join in the game—but just then, more quick than Jan could blink, the young mare lunged to champ his shoulder, taunting him with her wild green eyes. In a flash, he was after her. Jan heard Dagg’s distant, startled shout at being left behind as the young prince plunged breakneck downslope through treeboles and shadows. The last rays of red sunlight faded. Moments later, he burst from the trees onto the Vale’s grassy lower slope.

The hour was later than he had reckoned, the round-bellied moon not yet visible beyond the Vale’s far steep, but turning the deep blue evening sky to gleaming slate in the east. On the valley floor below, the herd already formed a rudimentary circle. Ahead of him, the pied mare pitched abruptly to a halt. Lock-kneed, snorting, Jan followed suit. Korr, the king, stood on the hillside just below them. Jan tensed as his massive sire advanced through the gathering gloom.

“Greetings, healer’s daughter,” Korr rumbled.

“Greetings, my king,” Tek answered boldly. “A fine night for Moondance, is it not?”

Jan felt himself stiffen at the black king’s nod. He barely glanced at Jan.

“It is that,” Korr agreed, “and a fine eve to precede your courting trek.” The healer’s daughter laughed. Pale stars pricked the heavens. The unseen moon was washing the dark sky lighter and yet more light. “Faith, young mare,” Korr added in a moment, “I’d thought to see you pledged long before now.”

Jan felt apprehension chill him. He had always dreaded Tek’s inevitable choosing of a mate. The prospect of losing her company to another filled the young prince with a nameless disquiet—the pied mare would doubtless be long and happily paired by the time such a raw and untried young stallion as he ever won a mate. Restless, he pawed the turf, and his companion glanced back at him with her green, green gryphon’s eyes.

“Fleet to be made warrior, but slow to wed, I fear,” she answered Korr. “Perhaps this year, my king.”

The eastern sky turned burning silver above the far, high crest of the Vale.

“But I will leave you,” she continued, “for plainly you did not wait upon this slope to treat with me.”

Tek shook herself. Korr acknowledged her bow with a grave nod as she kicked into a gallop for the hillside’s base. Still paces apart, Jan and his sire watched the healer’s daughter join the milling herd below.

“A fine young mare,” murmured Korr. “Let us trust this season she accepts a mate.”

Jan felt a simmering rush. “Perhaps I’ll join her,” he said impulsively.

Korr’s gaze flicked to him. “You’re green yet to think of pledging.”

Jan shrugged, defiant, eyes still on Tek. “I was green, too, to succeed you as prince,” he answered evenly. “But perhaps I shall be Tek’s opposite: slow to be made warrior, yet quick to wed.”

The sky in the east gleamed near-white above the far slope. Korr’s expression darkened. “Have a care, my son,” he warned. You’ve years yet to make your choice.”

The young prince bristled. Behind them, Dagg cantered from the trees and halted, plainly taken by surprise. He glanced from Korr to Jan, then bowed hastily to the king before continuing downslope. The young prince snorted, lashing his tail. The king’s eyes pricked him like a burr.

“Be sure I will choose when I know myself ready,” he told Korr curtly and started after Dagg.

His sire took a sudden step toward him, blocking his path.

“If it be this year, my son,” he warned, “then look to those born in the same year as you. Fillies your own age.”

Astonished, Jan nearly halted. By Law, not even the unicorns’ king might command their battle-prince. Angrily, he brushed past Korr. “Do you deem your son a colt still, to be pairing with fillies?” he snapped. “A bearded warrior, I’ll choose a mare after my own heart.”

He did not look back. White moonlight spilled over the valley floor as the herd before him began to sway, the great Ring shifting first one way, then the other over the trampled grass. Jan’s eyes found his mother, Ses, among the crowd. Beside the pale cream mare with mane of flame frisked his amber-colored sister, Lell: barely a year old, her horn no more than a nub upon her nursling’s brow. Korr cantered angrily past Jan, veering to join his mate and daughter as the dancers found their rhythm, began to turn steadily deasil.

Jan hung back. Dagg’s sire and dam moved past: Tas, Korr’s shoulder-companion, like his son a flaxen dun dappling into grey; Leerah, white with murrey spots, danced beside her mate. Jan spied his granddam Sa farther back among the dancers. Dark grey with a milky mane, the widowed mate of the late king Khraa whickered and nodded to her grandson in passing, placing her pale hooves neatly as a doe’s. Jan dipped his neck to her, but still he did not join the Ring.

Other celebrants swirled by, frolicking, high-stepping, sporting in praise of Alma under the new-risen moon. The circling herd gained momentum, drawing strength from the moonstuff showering all around; the white fire that burned in the bones and teeth, in the hooves and horns of all unicorns, placed there by the goddess when, in fashioning her creatures at the making of the world, she had dubbed the unicorns, as favored sons and daughters, “children-of-the-moon.”

Tek swept into view, pivoting beside the healer Teki. The black and rose in her coat flashed in the moonlight beside the jet and alabaster of her sire. Tek’s riant eyes met Jan’s, and she tossed her mane, teasing, her keen hooves cutting the trampled turf, daring him to join her. Daring him.

In a bound, the young prince sprang to enter the Ring. Bowing, Teki gave ground to let Jan dance beside his daughter. The two half-growns circled, paths crossing and crisscrossing. Dagg drifted near, chivvying Jan’s flank. Jan gave a whistle, and the two of them mock-battled, feinting and shoulder-wrestling.

Tek’s eyes flashed a warning. Jan turned to catch Korr’s disapproving glare. Reflexively, the young prince pulled up. Then, blood burning beneath the skin, Jan shook himself, putting even more vigor into his step. Moondance might have been a staid and stately trudge during his father’s princely reign—but not during his own! Dancers chased and circled past him in the flowing recurve of the Ring. He found his grandmother beside him suddenly, matching him turn for turn.

“Don’t mind your father’s glower.” The grey mare chuckled. “It nettles him that it is you now, not he, who leads the dance.”

Jan whinnied, prancing, and the grey mare nickered, pacing him. They gamboled loping through the ranks of revelers until, far too soon, the ringdance ended. Moon had mounted well up into the sky. All around, unicorns threw themselves panting to the soft, trampled ground, or else stood tearing hungrily at the sweet-tasting turf. Fillies rolled to scrub their backs. Dams licked their colts. Foals suckled. Stallions nipped their mates, who kicked at them. Jan nuzzled his grandmother, then vaulted onto the rocky rise that lay at the Circle’s heart.

“Come,” he cried. “Come into the Ring, all who would join me on the courting trek.”

Eagerly, the unpaired half-growns bounded into the open space surrounding the rise. Behind them, their fellows sidled to close the gaps their absence left, that the Circle might remain whole, unbroken under the moon. Jan marked Tek and Dagg entering the center with the rest.

“Tonight is Summer’s Eve,” he cried. “The morrow will be Solstice Day. Before first light, as is the Law, all unpaired warriors must depart the Vale for the Summer Sea, there to dance court and seek our mates. There, too, must we treat with the dust-blue herons, our allies of old, who succored our ancestors long ago. But mine is not to sing that tale. One far more skilled than I will tell you of it. Singer, come forth. Let the story be sung!”

Jan descended the council rise as the healer Teki rose to take his place. The singer’s black-encircled eyes, set in a bone-white face, seemed never to blink. Jan threw himself down beside Dagg as the pied stallion began to chant.

“Hark now and heed. I’ll sing you a tale of when red princess Halla ruled over the unicorns….”

Restlessly, Jan cast about him, searching for Tek. He spotted her at last, nearly directly in front of him, eyes on her sire. Contentedly, Jan settled down to listen to the singer’s fine, sonorous voice tell of the defeated unicorns’ wandering across the Great Grass Plain. After months, Halla’s ragged band stumbled onto the shores of the Summer Sea, watched over by wind-soaring seaherons with wings of dusty blue.

“So Halla, princess of the unicorns, made parley with these herons, to treat with them and plead her people’s case,” Teki sang, turning slowly to encompass all the Ring beneath his ghostly gaze.

“ ‘These strands are ours,’ the herons said. ‘And though the browse here may seem good in summer, little that is edible to your kind remains during the cold and stormy months of winter.’

“ ‘We do not ask to share your lands,’ the red princess sadly replied. ‘Not long since, we consented to the same with treasonous wyverns, only to find our trust betrayed and ourselves cast from our own rightful hills. Now we seek new lands, wild and unclaimed, to shelter us before the winter comes.’ ”

Tek tore a clump of leaf-grass from the ground beside her and shook her head. Jan watched the soft fall of her parti-colored mane against the graceful curve of her throat. Her green eyes caught the moonlight. Jan felt again the flush of warmth suffusing him. Truth, never had a mare lived—not even red Halla—more comely than Tek. As the singer lifted his voice again, Jan wondered if that long-dead princess of whom the other sang had had green eyes.

“ ‘We will go in search of such a place for you,’ the blue herons said. ‘Our wings are strong and the winds of summer fair. Your people are spent from your long wayfaring. Sojourn here for the season beside our Sea while we seek out a place such as you describe.’ ”

Teki sang on, finishing the lay with the herons’ discovery of the grassy Vale at the heart of the Pan Woods, verdant in foliage, its steep slopes honeycombed with grottoes to lend shelter against wind and rain, the whole valley uninhabited save for witless goats and deer. Exultant, the unicorns had claimed the Vale, securing at last a safe wintering ground: their new home in exile until the foretold coming of Alma’s Firebringer would one day lead them to reclaim their ancestral lands.

Listening, Jan found his thoughts straying to the fierce, furtive pans, whose territory he and his band must on the morrow begin to cross in order to reach the Summer Sea. Bafflement and frustration over the worsening gryphon raids crowded his mind as well, mingled with thoughts of the distant wyverns and this fitful, generations-long impasse his people termed a war.

Heavily, Jan shook his head. The moon upon his forehead burned. Somehow, he must find a way to conquer all these enemies and return his people to the Hallow Hills. Legend promised that he could do so only with fire. Yet he possessed no fire and no knowledge of fire, no notion of where the magical, mystical stuff could be found—not even the goddess’s word on where to begin.

Alma, speak to me! he cried inwardly.

But the divine voice that had once guided him so clearly held silent still. Despair champed at him. Teki quit the rise, his lay ended. Jan sighed wearily and stretched himself upon the springy turf. Dagg sprawled alongside him, head down, eyes already closed. Before him, Jan saw Tek, too, lay down her head. The moon, directly above, gazed earthward in white radiance. Jan shut his eyes. Others all around, he knew, already slumbered.

He felt himself drift, verge into dreams. Tangled thoughts of his people’s adversaries and his own impossible destiny washed away from him. Even memory of Korr’s harsh, disapproving stare faded. In dreams, the young prince moved through mysterious dances along a golden-shored green sea. Before him galloped a proud, fearless mare, her name unknown to his dreaming self, though she reminded him of none so strongly as the legendary princess Halla—save that this nameless, living mare had a coat not red, but parti-colored jet and rose, and green, green gryphon’s eyes.

2.

Summer

Tek tossed her mane, wild with the running. Wet golden sand scrunched between the two great toes of each cloven hoof. Alongside her, companions frisked through cool green waves. Summer sea breeze sighed warm and salt in her nostrils, mingling with the distant scent of pines. Ahead of her, the prince loped easily along the strand, his long-shanked, lean frame well-muscled as a stag’s. She loved the look of him, all energy and grace. What a stallion he would make when he was grown! Tek laughed for sheer delight.

High grassy downs bordered the shore. Jan led the band toward the maze of tidal canyons known as the Singing Cliffs. Wind fluted through their honeycombs like panpipes, a plaintive, sobbing, strangely beautiful sound. Above their soughing rose the shrieks and ranting of the seabirds which nested there.

Far overhead one speck among the myriad began spiraling earthward. Head up, the pied mare halted alongside Dagg as the prince whistled his band to a standstill. Other specks glided effortlessly down, blue as the sky in which they sailed. Soon they dropped low enough for Tek to distinguish long wings and slender necks, sharp, bent bills and lanky, web-footed legs.

In another moment, they began alighting on the sand. One heron, taller than the rest, her eye roughly level with Jan’s shoulder, fanned her feathery head-crest to reveal deep coral coloring under the dusty blue.

“Greetings, Tlat, far-roving windrider,” Jan hailed her. “Peace to you and to your flock.”

The leader of the herons clapped her bill and studied Jan with one coral-colored eye. Behind and around her, her people bobbled, folding their elongated wings with difficulty.

“So. Jan,” she called in her high, raucous voice. “The prince of unicorns returns.”

“Yes, I am returned,” the dark stallion answered. “Last year found me no mate, so this year I must try again.”

“Ah!” the seaheron cried. Bobbing and clattering, her people echoed her.

“How fared your own courting this past spring?” Jan inquired as the herons subsided.

Obviously pleased, Tlat groomed her breast. “Ah!” she piped. “The crested cranes—tried to steal our nesting grounds again this year. Ah! We drove them off.”

The prince nodded solemnly. Breathing in the tangy sea breeze and feeling the deep, steady warmth of sun upon her back, Tek bit down a smile. Every year the same report. Though the cliffs held ample nesting sites for all, the ritual clash between herons and cranes continued spring after spring. Tlat gabbled on.

“Now the nests are built, the hatchlings fat and sleek with down. My own brood numbers six! My consorts and I press hard to feed them all.”

Behind her, several of the smaller birds, males, began to step in circles, ruffling and fanning their crests. Tek counted half a dozen of them: one consort to father each chick? Jan bowed to them.

“My greetings to your mates, and to your unseen young as well. I trust we will meet when their wing-feathers grow?”

“Yes! Doubtless!” screamed Tlat proudly. “But we cannot stay. Our squabs cry out to us from the cliffs, and we must not let them hunger. Greetings and farewell!”

Tek glimpsed the red chevron on the underside of each pinion as the windriders shook out their wings.

Bowing, Jan replied, “The herons have been our allies for generations. We do not forget the debt we owe. Our courting dances will be the more joyous for your greeting.”

“Good!” screeched Tlat. “Beware the stinging sea-jells washed up on shore today. Though they are delicious to our kind, we know you find them unpleasant.”

The heron queen stretched her neck and stood on toes.

“Welcome, children-of-the-moon! May your summer here prove fruitful—though how odd that your kind takes but a single mate. Unicorns are strange beasts.” Abruptly, the stiff wind caught her, plucking her away almost before the pied mare could blink. Other seaherons followed, rising light as chaff. Tek joined Jan and her fellows in bowing again to the departing herons.

“Good winds and fair weather attend you,” the prince called after them. Tek was not sure they could hear him above the thrash of surf and eerie crooning of the Cliffs. The windriders had already dwindled to mere motes overhead. A moment later, she lost sight of them, swallowed by the fierce blue, cloudless sky.

Stinging sea-jells did indeed lie beached downshore as the windriders had warned. Jan kept his people out of the waves until the next tide swept the bladderlike creatures with their trailing tendrils away. Summer passed in a headlong rush. The young prince felt himself growing, bones lengthening, muscles massing. He was ravenous and glad of the freely abundant forage. The sky held mostly warm and fair.

He devoted a good part of his day to chasing the other young half-growns and setting them to races and mock-battles, dances and games. Herons brought news of shifts in the wind so that Jan could whistle his band to shelter in the tangled thickets well before any storm. What time he did not spend tending the band he passed with Dagg, exploring inland at low tide along the Singing Cliffs, stopping now and again for a furious round of fencing.

Tek’s admirers, he noted testily, were even thicker this year than last. Yet she seemed to pay them as little heed as ever. Once or twice, he even noted her ordering some overly bold young stallion smartly off. More and more, the young prince observed, the healer’s daughter sought him out, teasing him away from the band—even from Dagg—to run with her along the wet, golden beach, dodging through dunes, or up onto the highlands above the cliff-lined shore.

Though he knew she could only be doing so to gain respite from bothersome suitors, Jan found himself increasingly willing to be led away. The pied mare’s every word, her every move fascinated him. He loved to brush against her smooth, hard flank in play or simply prick ear to the cadence of her voice.

Long summer days ambled lazily by, the starry evenings fleetingly brief. With each passing moon, the high sun of summer gradually receded toward the southern horizon. Now it shone nearly directly overhead at noon. Nights lengthened: soon they would overtake the days in span. Equinox, marking the summer’s end, crept up on the young prince unawares.

He and Tek chased across the high downs above the shore, wind whipping their manes and beards. Overhead, herons soared, diving like dropped stones into the shallows of the Sea, fishing for squid. Tek laughed, plunging to a halt at cliff’s edge. Frothed with foam, the surging green waters below shaded into ultramarine at the far horizon. Shouldering beside her, Jan was surprised to find himself now taller than she. Had he truly grown so in these last swift months?

Tek tossed her head. The rose and black strands of her mane stung against his neck. The Gryphon Mountains stood barely within sight across the vast bay, but Jan spared them scarcely a thought. Never had unicorns summering upon the Sea been troubled by raiders. Wingcats attacked unicorns only within the Vale, and only at first spring. Spotting his shoulder-friend on the smooth beach below, in the thick of a group of sparring warriors, Jan felt a sudden chill.

“We should go back,” he said. “We’ve left Dagg.”

The healer’s daughter shrugged. “He is with companions”—she eyed him coolly—“and seems content.”

Jan snorted, champing. “We leave him much alone these days.” Even so high above the shore, he still caught the faint click of parrying horns. Wind gusted and sighed. Farther down the strand, another knot of young half-growns frisked, fishing fibrous kelp from the waves and playing tussle-tug. Salt seethed heavy in the wind. Abruptly, Jan turned to Tek.

“You are ever luring me off these days, even from our shoulder-friend. Will not Dagg’s company do as well as mine to keep your admirers at bay?”

Tek laughed. “Dagg may be my shoulder-friend as well,” she answered, watching him aslant. “But he is not the one I am courting, prince.”

Jan felt surprise slip through him like a thorn. He stared at her. She could not have knocked the wind from him more thoroughly if she had kicked him.

“What, what do you mean?” he demanded. “I’m far too callow—”

“Are you?” the healer’s daughter asked. “So speaks your sire! But what say

you?” She sidled, teasing, nipping at him with her words. “Three times before have I come to the courting shore—each time only to depart unpaired. The first two summers, I was newly initiated, just barely half-grown. Last year, it was the one on whom I’d set my eye who was just freshly bearded, unready yet to eye the mares. This year, though, while young yet, he has wit enough to know his own heart—and I count him well grown.”

She shouldered him. Jan looked at her, unable to utter a word. A sudden fire consumed him at her touch.

“Hear me, prince,” the pied mare said, “for I begin to chafe. Long have I waited for you to catch me up.” She shied from him, circling, leading him. The dark unicorn followed as by a gryphon mesmerized. “Surely you do not mean to make me wait forever?”

Trailing after Tek, Jan felt himself growing lost. Her eyes drew him in like the surging Sea. In their jewel-green depths, he saw of a sudden possibilities he had never before dared contemplate: Tek dancing the courting dance with him under the equinox moon, the two of them running the rest of their days side to side, unparted by any other—and in a year or two years’ time, fillies, foals….

“I—I must think on this,” he stammered, stumbling to a stop, and cursed himself inwardly for sounding like a witless foal. Tek only smiled.

“Think quickly, prince. Equinox falls in only six days’ time. Five nights hence, we dance the dance.” She snorted, shaking her mane. The scent of her was like rosehips and seafoam. “Remember my words,” she said saucily, “come equinox.”

She sidled against him, nuzzled him, her teeth light as a moth’s wing against his skin. Jan shivered as Tek broke from him, flying away across the downs, skirting the cliff’s edge and heading for the steep slope angling down toward shore. Dumbstruck, the prince of the unicorns stared after her. By the time he had gathered both wit and limb, she was already gone.

“So you’ve decided,” the dappled warrior remarked. Jan and he trotted along the narrow strand flanking the Singing Cliffs. Tide was out, affording them passage. The sea breeze hooted and sighed through the twisting canyons.

The young prince halted, unable to mistake his shoulder friend’s meaning. “How did you know?”

Dagg whinnied. “I’ve known since spring. I wish you both joy.”

His mirth had a strangely painful ring. Hearing it, Jan became suddenly aware that Dagg had no young mare like Tek with whom to spend his hours and dream of one day dancing court. Jan shook himself. The thought of making the pledge himself and leaving Dagg behind, unpaired, made his skin taut.

“Hist, nothing’s decided until the eve of equinox!” he cried, shouldering against the younger stallion. “Come, you’ve time yet to make a choice—any number of mares would spring to pledge with you. What of that filly I saw you sparring with the other day? The slim, long-legged blue…”

“What—Gayasa’s daughter, Moro?” Dagg laughed again, in earnest this time. “She’s barely got her beard; she was only made warrior this spring past—far too young.” He shook his head. “And so am I. Another year.”

Turning, he broke into a trot. Jan loped after him. “It doesn’t have to be,” he said urgently.

Dagg halted, stood gazing off across the green and foaming waves. “She’s not among us,” he said at last. “She’s not yet here for me to pledge.”

Jan frowned, not following. The dappled warrior turned.

“Do you recall,” he asked quietly, “the night of our initiation two springs past?”

Jan nodded slowly: the night when initiates to the Ring of Warriors became, for one brief instant, dreamers, to whom Alma granted glimpses of their destinies.

“Tek says she saw the foretold Firebringer,” continued Dagg, “moon-browed, star-heeled.”

The young prince shook the forelock out of his eyes, digging nervously at the shell-embedded shore with his left hind heel.

Aye, marked as the Firebringer, he thought miserably,

but without so much as an inkling of where I’m to find my fire! Dagg glanced at him.

“You yourself beheld visions of the goddess’s Great Dance.”

Jan shrugged and sidled.

And only darkness since: not even a whisper of a dream. “What did you see?” he asked his friend suddenly. “You’ve never said.”

Dagg closed his eyes. “I saw a mare,” he said, “small, but exquisitely made, high-headed, her coat a strange bright hue such as none I’ve ever seen. Each Moondance, I’ve scanned the assembled herd….” He opened his eyes and turned to look at Jan. “Even though I know my search is hopeless. Her mane stands upright along her neck. Her tail falls silky as a mane. Her chin is beardless, no horn upon her brow. Each hoof is one great solid, single toe.”

The young prince stared at him, dumbstruck. Dagg nodded. “Aye. She’s not of the Ring, Jan,” he whispered. “She’s a renegade.”

Frowning, Jan shook his head. “You and I both know those legends of outlaws losing their horns when banished from the Vale are only old mares’ tales.”

Dagg stood silent. Again, the young prince shook his head.

“Yet, if not a Plainsdweller,” he murmured, “what manner of mare could this dream creature be?”

The dappled warrior snorted, shrugged, his pale eyes full of pain. “I’ve no notion. I only know she is my destiny—and I’ll never find her in the Vale.”

They both stood silent then. The breeze through the near Cliffs hummed and shuddered. Cranes wheeled screaming among the herons overhead. Tide came foaming in, wetting the two unicorns’ cloven hooves, eating away the beach. The prince’s shoulder-friend leaned hard against him.

“Jan, don’t wait for me,” he said. “Alma alone knows when I’m to find my mate. You’ve already found yours. Don’t hold off. Don’t spoil your own happiness—and Tek’s—because I can’t join you this year in the pledge.”

Jan turned to study his friend. Favoring one foreleg, Dagg forced a grin. Half-rearing, he smote at the dark unicorn smartly with his heels. Jan whistled and shied, fencing with him, grateful and relieved. He felt as though he had tossed a hillcat from his shoulders. Wheeling, Dagg sprinted away. Jan sprang to follow, and the two galloped back along the seacliffs to rejoin the band.

On the night before equinox, the firefish were running: small, many-armed creatures that swirled luminous like stars through the great bay’s pellucid water. They filled its breadth with a blaze of rose and pale blue light. The herons celebrated the advent of the firefish with noisy whoops, diving from moonlit air into the midst of those swarming near the surface of the waves, tentacles entwined, about their own strange courting rites.

Other windriders skimmed low, their bent bills laden with tangled, suckered arms as they snatched prey from the combers. Their eerie, loonlike cries and staccato splashes sounded through the cool, motionless air. For once, the Singing Cliffs held silent, no wind to wake their ghostly song. Jan and Dagg stood at the edge of a tangled thicket, watching herons and firefish and foaming sea as evening fell.

“Moon’s up,” Dagg told him.

The huge, mottled disk hung just above the far Gryphon Mountains to the east, dwarfing them, paling the stars. Its light made a long path of brightness across the placid bay. Jan nodded.

Dagg fell in beside him as he turned and trotted through the verges of the thicket. Jan’s ears pricked. Above the herons’ distant plash and cry, the quiet rush of waves along the shore, he heard the sounds of unicorns gathering: snorts and shaking, the dunning of hoofbeats, a restless stamp.

He and Dagg emerged from the trees. Horn-browed faces turned expectantly as the dark prince loped to the center of the dancing glade, a circular, open space at grove’s heart, trampled clean of vegetation by generations of unicorns. He halted, chivvying, his own blood running high. His restless followers milled and fidgeted, anxious to declare their choices in the dance. Jan tossed his head.

“This is the night we have all awaited,” he told them. “Let those who know their hearts choose mates tonight, pledging faith to one another in the eyes of Alma for all time!”

With a shout, eager half-growns sprang into vigorous, high-stepping cadence, prancing and sidling before their prospective mates. Jan watched the moving river of unicorns, chasing and fleeing their partners in an endless ring. Dagg cantered past twice, three times—but where was Tek? He did not see her. Frowning, the young prince scanned the russets and blues of the others until a flash of pale rose and black revealed the pied mare. She seemed to be deliberately skirting the fringe, ducking behind other warriors to conceal herself from him.

The young prince plunged into the dance. The healer’s daughter quickened her pace. With a surge of determination, he sprinted after her. All around him, companions circled, manes streaming, heels drumming. The moon rose higher until the youngest warriors, wearied and unpartnered still, dropped out to stand at the edge of the grove, only watching now. He glimpsed Dagg among them, pulling back, panting, sparing his once-broken foreleg just slightly.

Jan redoubled his pursuit of Tek, dodging through the remaining half-growns. In pairs, some of these had started to slip away, mares leading, stallions following, chasing off into the trees. Jan listened to their whistled laughter, their hoofbeats fading. Deep under cover of darkness, they would dance their own, more privy dances under Alma’s eyes alone.

The crowded rush had begun to thin, more than half having slipped off or dropped away, unpaired. Yet still the healer’s daughter eluded him. The young prince snorted, wild with frustration. How could she manage it, threading so nimbly among the others, always just a few teasing strides ahead? Once more he started to quicken his gait—then abruptly stopped himself, for all at once, he understood. He must stop trying to catch her, cease striving to run her down like some rival in a race—for this was not a race, he realized suddenly, nor any sort of contest at all. It was a dance.

They moved in a circuit. He could not lose her, and whether it was he who overtook her, or she who circled forward to catch him from behind, what did it matter? Laughing, he let himself fall back into the flowing ring of unicorns, and all at once, she was beside him, the two of them prancing and frisking, chasing and circling one another. Others around them faded from his thoughts. He and Tek formed their own circle at the heart of every larger circle and cycle and dance.

They had left the grove, he realized. The sound of the other celebrants faded behind them as he and Tek loped deeper into the trees. The murmur of sea and shore drew nearer. The shimmer of sealight glistened beyond the shadows, mingled with the pale gleam of moonlight.

Tek moved ahead of him, still beyond his reach, but only trotting now. She glanced over one shoulder, nickering, her green eyes lit by the moon. In another moment, he would catch her and pledge his vows, hear her pledge hers in return. Then they would be conjoined for life, their bond unshakable in Alma’s eyes. It was what he had always longed for. He knew that now, and the knowledge warmed him like a fire.

3.

Storm

Jan stirred in the grey light of morning. He lay on dry, sandy soil under knotted, smooth-barked shore trees. The beach lay only a short way off. Sky had grown heavy and overcast, dark slate in color. No longer calm, the grey-green sea frothed, foaming along the strand. Storm in the wind, he thought. Even now, at slack tide, the sea was running high.

His head rested upon another’s flank, his neck lying along her back. He savored the warmth of the other’s side against his own, her breaths even and light. Tek woke and, lifting her head, leaned back against him, caressing his strong-muscled neck with her own. Gently, he nipped her. She laughed, gathered her limbs, and, shaking the sand from her, rose. Jan did the same, nuzzling her.

“My mate,” he murmured.

Again the pied mare nickered, shook him off. “Enough, prince! All night we danced, and I am spent. We must rejoin the others and take our leave of the dust-blue herons.”

Jan sighed. By custom, the newly paired warriors must be gone from the courting shore by noon of equinox day. He stretched his limbs. Time enough to dance with his mate again when they reached the Vale some three days hence. He smiled, languid still, as Tek started away through the trees.

“What sluggards we have been,” she called. “Half the morn is lost!”

Jan laughed, trotted to catch her up. The trees were sparse enough to keep the shore in view. The sea was truly wild this morn. Wind gusted, frothing the waves to spume. The beach had been eaten almost away by the rising tide. Dense clouds thickened the sky. Across the broad bay, great purple thunderheads boiled above the Gryphon Mountains. The air smelled humid, heavy with the coming rain. Abruptly, the dark prince halted. Against the soughing of wind and the crash of sea he heard high, keening screams—too sharp and full-throated to be herons’ cries. Tek’s ears pricked.

“List,” she started. “What…?”

The strident calling intensified. Jan’s heart contracted suddenly as he caught the piercing whistles of warriors taken by surprise. Dagg’s voice bellowed orders from the beach.

“Gryphons! Haste—rally: make ring! Wingcats are upon us—”

With a shout, Jan charged past Tek, heard the drum of his mate’s heels only a half-pace behind. The trees fell away as he burst from the grove to behold his whole terrified band ramping on the wind-whipped shore, sea foaming behind them, while a dozen screaming gryphons circled above. Jan shied, staring, stunned. Never had such a thing been recounted in story or lay, that gryphons should attack unicorns upon the shores of the summer Sea. Wingcats only raided the Vale—and only at first spring!

Before him, the young warriors scrambled to form a ring. Dagg whinnied orders, hurrying them into rank. Skirling gryphons dived. The flock consisted mostly of lighter, smaller males: the tercels’ jewel-green feathers and golden pelts stood out against the storm-dark sky. Only four of the raiders were the larger females—blue-fletched formels with tawny hide. Jan shook his head: these were not mated pairs! Nor, so late in the year, could any hungry hatchlings yet remain in the nest.

Fiercely, the unicorns reared and jabbed at their attackers. Sprinting past her mate, Tek sounded her war cry. Furiously, Jan trumpeted his own. He dodged a green-and-gold tercel’s swoop—then, quick as stormflash, leapt after and felt his horn slash golden hide. The gryphon shrilled. Jan whinnied in defiance. Tek, he saw, had safely reached the ring. He himself was beside Dagg a moment later.

“They fell on us without warning,” the dappled warrior panted, rearing and stabbing at a swooping formel. She pulled up before meeting his horn. Dagg smote the ground in frustration. “Just moments before you arrived!”

“No taunts? No challenges?” Jan asked him, then shouted at a young warrior starting after a low-flying tercel to get back into line and not break ring.

“Nothing!” Dagg answered, wheeling to drive off another formel diving from behind toward the center of the ring.

Jan grazed her wing, champed a cluster of feathers in his teeth. He yanked hard, trying to pull her down but, shrieking, she tore free. Dagg gouged her belly, and she slashed at him with one claw.

“It’s war, then,” Jan said grimly. “Not just hunting.”

Across from them, he glimpsed Tek repelling a tercel that dropped toward a mare who had stumbled. Around her, the ring of warriors ramped and jostled, badly crowded by the tight formation. Above them the circling gryphons darted, stooping to slash, then lofting away. The young prince snorted in disgust. A traditional defense was proving useless. Nearly impenetrable to grounded foes, the band’s outward-facing ranks availed little against adversaries that darted from the air, attacking the unicorns’ unprotected hindquarters at the circle’s heart.

“Get to the trees!” he shouted as yet another formel plunged toward the ring’s center. “Haste! Break ring! Get into cover of the grove!”

“Jan, what—” cried Dagg, aghast.

“Fly!” ordered the prince. What he urged was unprecedented, he knew—but clearly facing an airborne foe required fresh tactics. “They can’t swoop to attack us among the trees!”

Rising wind nearly ripped the words from his teeth. He saw his mate nipping and hying her fellows, driving them toward the trees. Dagg and too many of the others simply continued to stare. The dark prince whirled and shouldered the young stallion nearest him, striking him across the rump with the flat of his horn to send him off. The half-grown mare beyond bolted as well while the wingcats redoubled their attack.

“Move!” he cried.

The dappled warrior seemed to swallow his consternation at last as the ring, now hopelessly broken, scattered toward refuge in the grove beyond the dunes. For an instant as she fled past him, Tek’s puzzled gaze met his. Clearly she did not understand his strategy, even as she carried out his commands. Dagg started after her. Jan himself did not follow, watching as the two of them hung back a bit, forming a rearguard for their escaping fellows. They were the last to disappear into the trees.

“The prince! The unicorn prince!” one of the tercels cried.

Other wingcats took up the chant. The wind off the sea had grown so strong that Jan saw his attackers wobbling precariously as they banked and turned, breaking off their pursuit of the retreating unicorns. The relentless sea surged at his back. As a dozen wingcats beat toward him from above the dunes, he knew he could never hope to win past them to the grove.

“Alma aid me,” he whispered. “Stand at my shoulder, O Mother-of-all!”

The Singing Cliffs rose to his left. Their honeycomb of wind tunnels and tidal canyons shrieked in the rising stormwind. Jan noted with relish how the wingcats strained and labored through the air. Whipping gusts tossed and batted at them. Earthbound, he himself was not so hampered.

As the first gryphon to reach him stooped, the dark unicorn dodged, sprinting away down the beach. The angry cries of his pursuers rose behind. The tall Cliffs opened before him. Jan ducked into their twisting maze. The air around him hummed, vibrated. Wind sheered and shuddered through the turning canyons, whistling like warriors, like birdsong, like reed flutes of the woodland pans.

His path looped and folded back upon itself. Powerful air currents buffeted treacherously. Rounding a bend, Jan glimpsed a wingcat formel being dashed by the gale against the cliff’s side behind him. She crumpled, falling, and her companions screamed, increasing their speed. Long, keening wails rose on the stormwind as the churning air grew furious, laden with scattered, stinging rain.

Glancing back again, Jan saw more gryphons swept against the cliffs. The tremendous gusts barely reached him in the canyons’ depths. Elated, the dark prince sped on while his remaining pursuers struggled to keep aloft despite the pelting rain. Drops fell more heavily, pounding down. Another tercel smashed into a ledge. Blue lightning split the heavens, casting a cold sheen like moonlight across the cliffs.

Tidewater spilled into the canyons suddenly. Jan found himself running through seawater up to his pasterns, flinging sheets of spray with every step. Only three gryphons remained in pursuit, green tercels all. Their shrieks tore at his ears. The cliffs sang, shuddered with stormwind. He heard the hammering of waves just beyond the canyon wall.

More seawater poured into the chasm. Halfway up his shanks, its depth impeded his gallop. Rain pummeled down. The tempest howled. Jan plunged on, limbs straining against the turbulent water’s pull. The canyon ran straight now, without a bend. If he did not find a way out of the Cliffs soon, he realized, he might well drown.

The cliffside opened abruptly before him. Jan glimpsed beach and storm-filled sky. Only a single gryphon’s voice trailed him now, the others all lost, or dashed to their deaths, or given up. Seawater crashed into the opening, the swell up to his knees, its undertow fierce. Furiously, Jan fought his way through the inrushing tide. The gryphon behind him shrilled in fury, so close the sound sliced the prince’s ears.

Suddenly he was free of the cliffs, in a tidal trough deep with running sea. Firm ground lay within sight, a rocky beachhead only a score of paces beyond. Jan plowed toward it through the foaming surf. Again the gryphon’s savage cry. The dark unicorn felt talons score his back, a razor beak striking the crest of his neck. He ducked, dodged sharply. Great green wings slapped the waves to either side. The raptor’s grip tore into his flesh, fastening upon his shoulder blades.

Screaming with pain, Jan bucked and reared. Lion’s claws hooked into his flanks, forcing him down onto all fours again. With a surge of unsought strength, Jan galloped breakneck, thrashing. Broken shells and beach gravel ground beneath his heels. The wingcat’s grip slipped, balance faltering. The sea drew back, momentarily shallower—then a huge green wave twice Jan’s height broke, overwhelming the young stallion and his attacker both.

Jan felt himself trod down as by a mighty hoof, the breath knocked violently from him. His knees, his ribs grated against the tidal trough’s stony bed. He felt the gryphon torn from him by the surge. Struggling against a powerful current, he broke surface, snatched a breath. The black sky above roiled as rain-pebbled waves swept him under again.

Choking and snorting, he flailed madly to keep afloat. He glimpsed the Cliffs—much farther off than he had expected—and strove frantically to swim back to land. But the tow only pulled him farther out to sea. Something green and gold washed onto the distant rocks. The surge dragged it back before flinging it higher. This time it lodged, sodden and unmoving: the body of the gryphon tercel, broken by the waves.

Jan lost sight of shore. Rolling hills of water bobbed all around. Merciless wind whipped, its driving rain blinding him. Again a wavecrest broke over him, forcing him down into churning depths. Again he fought his way up, but more weakly this time. Something drifted against him in the darkness under the waves, brushing his flank. Long tendrils twined about his limbs, pricking him with needles of fire. Sea-jells! Rucked up from deep ocean by the storm.

Panicked, the dark prince floundered, gasping, choking. But the barbed streamers only entangled him further. Their burning poison began to numb him. Vainly, he searched for land. The sea heaved. Stormwind buffeted. Presently, the sea-jells released him and floated on. Strange drowsiness stole over him. His burning limbs twitched, heavy as stone. Then his eyelids slid shut as he sank beneath the cold and furious sea.

4.

Search

Tek hunkered down, rump to the driving rain. No gryphons had pursued them into the trees. Dagg hunched close, his nearness shielding her. Tek wished it were Jan flanking her as well—but in the confusion of flight, she had lost track of her mate. The pied mare shuddered. Wind and storm were now so furious she could scarcely see the other warriors huddled among the treeboles of the grove.

At last after what seemed an age, the gale spent itself. Black clouds parted, scudded away across the sky. The clean-washed air seemed dazzling, charged. And cold. The brilliant, midafternoon sunlight held no warmth. The first draft of autumn breathed unmistakably across the shore. The pied mare shook her rain-soaked pelt. Dagg trotted off to round up stragglers. Tek headed the other way, eager to discover Jan—but as she nipped and shouldered her scattered fellows back toward the rest, she felt a beat of fear.

“I don’t see him,” she called, glancing anxiously through the half-growns following Dagg. The prince’s shoulder-friend cavaled.

“I’d hoped he was with you.”

Drenched and weary, the battered young warriors milled around them. Tek noted bruises but few gashes, none deep. Most simply seemed badly shaken. Frowning, she lashed her tail. Where was the prince? It should have been he, not she and Dagg, to gather the band.

“Would he have gone scouting?” the dappled half-grown asked.

The pied mare shook her head. Why would Jan search for wingcats on his own when companions would have made the task far safer? The young warriors fidgeted.

“Ho,” she called to them. “Which of you sheltered beside the prince?”

Half-growns shifted, glanced at one another. No one spoke. Tek snorted.

“I say regroup on the beach,” Dagg offered. “Jan’s most likely already there.”

Tek whistled the others into line, unease edging into full-blown worry. She doubted her mate would rush to examine a battlesite when all trace of the fray had surely been obliterated by storm and tide. Trotting briskly to the head of the band, she called back, “Dagg, take rearguard.”

They picked up a few more stragglers among the trees—but the beach lay deserted, half-eaten by storm. The gale-high tide had only partly receded. The pied mare gazed in dismay at the cast-up sea wrack, the carcasses of dead sealife. She spotted a dark shape lying beached upon the shore and froze, her heart beating hard. Then her terror subsided as she recognized it for what it was: a black whale calf, dead. Roughly the same size as a half grown unicorn—but not Jan. Not Jan.

Tek champed her teeth, sent the others off to comb the strand. The unicorns fanned out, calling their prince’s name. She kept several of the keener-eyed on watch, scanning the sky, not daring to trust the gryphons safely gone. When one of the lookouts whistled, Dagg and the others came galloping back to where she and the sentries stood craning heavenward.

“Wingcats?” he panted.

“Nay,” she answered. “Look at the pinions’ length: seabirds, not raptors.”

“Herons!” cried Dagg. “We can enlist their aid in finding Jan.” As the slender forms of the seabirds dropped within range of her voice, Tek hailed them.

“Succor us, O herons! Your allies have need of your airborne eyes.”

Gingerly, awkwardly, the flock alighted, their leader, Tlat, touching down to the damp sand first, followed by her consorts and the rest. Tek noted a number of gangling half-growns among them, uncrested, barely full-fletched. They gazed at the unicorns with round, curious eyes. Beside her, Dagg snorted and sidled impatiently. Tek hissed at him to be still, then whistled the others to keep their hooves firmly planted, lest the flighty windrovers take wing in alarm.

“Ah!” cried the heron queen, bobbing and dancing. “Where is your prince, pied one? Where is the unicorn Jan? First storm of fall has blown, and we have flown our young from the cliffs at last to teach them to forage on their own. Whale meat! Sweet squids! And to show them the unicorns before you must depart. Equinox is past. Fall glides in. You must be off, we know. But where is Jan? I would show him my brood.”

Scarcely able to contain her urgency, Tek forced herself to hear Tlat out and to bow her neck respectfully.

“Your many young are beautiful, Queen Tlat, strong-limbed and finely feathered. May their crests grow brilliant. Would that my mate were here to see them. But he is lost to us. We do not know where he is. We were set upon by gryphons just before the storm. Now we cannot find Jan.”

“Gryphons!” shrieked Tlat, hopping backwards. “Stormriders, yes.”

Her people fluffed and began clapping bills, some dancing in agitation. One young bird started to whoop, and one of Tlat’s mates stalked over and pecked it to silence. Tlat preened, fanning her crest, and looked at Tek one-eyed.

“We saw the cat-eagles, yes! Approaching across the bay—we longed to send you warning, but the wind was already too strong. We dared not leave our cliffs. So they attacked you? War! War! Marauders.”

She stabbed at a crab digging itself out of the sand near her toes, cracked its shell, then tossed its contents down. More bill-clattering from the flock. Tek fought for composure in the midst of the cacophony.

“We regret you were unable to bring us warning,” she replied, striving to recapture Tlat’s attention. The queen of the seaherons stood turning her head from side to side, eyeing the dead crab first with one eye, then the other. “But we ask your aid now. The herons are our fast allies, and we value the deep friendship between our two peoples.”

“Friendship,” clucked Tlat. “Allies, yes! How may we aid you?”

“Lend us your wings and your eyes,” Tek urged her. “Help us to search for my mate, our prince.”

“Prince’s mate!” the heron queen cried. “Look for your mate—yes. We will! We will help you seek the prince of unicorns!”

With a scream, Tlat unfolded her slim, lengthy wings and fanned the air. The seawind—now no more than a breeze—caught, lifted her. Dipping her long neck to catch up the empty crabshell in her bill, the heron queen rose. Her consorts and children and the rest of her people followed, soaring aloft, shouting, “Find the prince! The prince!”

One of her consorts skimmed near to pluck the crabshell from her bill. It was snatched from his by another bird and passed from beak to beak throughout the flock. Tek stood on the beach, gazing after them, mystified. Another fear had begun to gnaw at her like a biting fly: that Jan perhaps lay wounded among the trees, invisible from the air.

High above, the herons broke and scattered, some skimming up the beach, others down, and many inland, sailing low over the tops of the trees. Shaking herself, Tek whistled her own followers into a similar sweep, desperately hopeful that they would find her young mate soon.

The seaherons spied no trace of Jan that day, nor the next day, nor the next, though they found nearly a dozen gryphons dead in the honeycombs of the Singing Cliffs. Had the remainder carried the prince away? Rising panic held Tek’s heart in its teeth at the thought that she might have become the prince’s mate but for a night, their wedding dance the last joy of him she would ever know. As heron messengers returned each night, Tek found it harder and harder to stave off despair.

On the third day, Dagg ceased to speak, all optimism dashed. Other members of the band remained painfully silent: angry, grieving, stunned. Tek felt all her wild hopes dying. The day ended in storm, not so violent as that of equinox, but bone chill, beating down the seaoats to rot and whipping the foliage from the trees. When the following cold, grey morning dawned, Tek, herself frozen past any feeling but exhaustion, forced herself to speak.

“He is gone,” she told the band. They stood subdued before her, silent. “Surely the gryphons took him. They have killed our prince in open war. We must return to the Vale and bring word of this to the herd.”

Dagg bowed his head. None of the others so much as raised a voice in protest. With a start, Tek realized that they had all despaired days ago. Only she had clung to the stubborn dream that Jan might still live. Outrage filled her at her own foolishness.

When the seaherons came again, Tek bade them farewell, thanked them woodenly for their hospitality, and praised again their lank, gawking children. Pledging to return the following summer, she expressed the unicorns’ unending gratitude for their allies’ diligence in the search. Plumage drooping, crests flattened to the skull, the typically raucous herons only nodded. Tlat even solemnly returned Tek’s bow before soaring away with her flock.

Numb, Tek whistled her own followers into line. They straggled after her from the sandy shore, climbed the downs, traversed the coastal plain, and entered once more into the dark Pan Woods, having failed even to discover and carry back to the Vale their prince’s bones to be laid with proper ceremony upon the altar cliffs beneath the sky.

What will I tell his father? What will I tell the king? The refrain repeated itself relentlessly inside the pied mare’s skull as she led the band dejectedly homeward. Dagg brought up rearguard. They could not bear to face one another. Tek groaned inwardly, wretched. All the while the image of Korr, dark and brooding, loomed before her.

5.

Fever

The rhythm of the waves woke him, their gentle wash against and across him soaking his pelt. He felt the cold sting of air briefly, then another wave. The dark unicorn opened his eyes to find himself lying pressed against wet sand. Another swell sluiced over him. Choking, he rolled to his knees, pitched shakily to his feet.

He stood on a low, flat beach, the sand silver-white. No cliffs or downs flanked the shore, only dunes—and beyond them, dense thickets of trees. The dark unicorn blinked in confusion. He did not recognize the grey sea and white sand. He had come from a place of green waves, golden shore. He remembered a storm.

Weakly, the dark unicorn shook himself, staggered. Beach grit abraded his skin. His withers and back were scored by deep wounds, his limbs and belly patterned with raw, raised welts. His mind felt poisoned, numb. The salt air breathed against his wet coat, chilled him to shivering. The waves foaming placidly against his pasterns and shanks felt soothingly warm.

Turning, he gazed cross the calm, grey expanse: no longer storm-tossed, the sky above pearly with a thin overcast of cloud. The wind shouldered against him insistently, full of salt and particles. He faced away from the sea, climbed laboriously higher onto the beach. His hooves sank deep into the soft, dry sand. He set his rump to the wind’s relentless, gentle gusts and bowed his head. The sting-welts ached. His shoulders ached. Heat burned in him, guttering against the cold.

“Fever,” he muttered.

Feebly, he slapped the draggle of wet mane from his eyes and gazed at the trees beyond the dunes. Trees would shelter him, provide forage. Maybe water. The gummy, salt taste of his own tongue constricted his gorge.

“Water,” he told himself dully. “Find water.”

Aye, a soft voice answered now. Get out of the wind and cold. Find shelter. You’ve drifted a long time.

The dark unicorn blinked. No speaker met his eye. The wind swept beach lay empty, deserted. Strange. The words had seemed to come from within. Feverchills danced along his ribs and limbs. Still muddled, he shook his head.

“Water first,” he croaked. “Then…find the others.”

He remembered companions vaguely: unicorns like himself. What were their names and whence had they come? Somehow he knew the golden, cliff-lined strand he recalled was not their home. Yet neither was this flat expanse of silvery shore.

Find the fire, the inner voice said clearly.

Glimmers of warmth and tremors of cold gusted through him. The dark unicorn shook his head.

“Fire?” he muttered.

He had forgotten his own name. Small grey-and-white seabirds wheeled overhead: dark hooded, with darting pinions. The strange voice commanding him sounded half like the sighing of shore wind and half like their high, piping calls.

Behold.

The dark unicorn started, stared as a brilliant red streak arched burning across the sky in the far, far distance. A dark wisp of vapor or dust blossomed up leagues upon leagues away, beyond horizon’s western edge. Long seconds afterwards, a faint concussion reached him: the earth trembled.

Head west, the inner voice instructed him. Along the shore.

The dark unicorn staggered, nearly fell. Standing took almost more effort than he could muster. “What is my name?”

West, the voice reiterated. When you have found my fire, you will once more know yourself.

The voice faded, faint as a gull’s trill on the wind. The dark unicorn blinked dizzily. Shelter, food, and water—he must find them soon, or he would die. Painfully, he dragged his hooves across the low, white dunes, heading westward toward the distant, tangled trees.

6.

Home

The sky spanned clear, the air crisp with the breath of fall. Tek shook her head. Had they been but three days crossing the Pan Woods, returning from the Summer Sea? It felt like dozens. Solemn half-growns straggled around her as they emerged from the trees onto the Vale’s grassy lower slopes. Tek beheld the waiting herd below: mares and stallions, fillies and foals milling expectantly. Her heart froze as she spotted Korr, the king; his mate, Ses; and their yearling filly, Lell: princess of the unicorns now. The pied mare shivered, glad Dagg had come forward to walk alongside her.

“What has happened?” thundered Korr as they reached the bottom of the slope. “We awaited your return days since! Why do you, healer’s daughter, head the band instead of Jan? Where is my son?”

Heartsick, she met Korr’s gaze.

“Jan is not among us,” she answered. “Gryphons took him. He is slain.”

The dark stallion’s eyes widened. Around him, the whole herd started, shying. Tek heard shrill whinnies of astonishment. Before her, the king reared, snorting wildly.

“Gryphons?” he demanded. “On the Summer shore?”

Tek nodded and listened, mute, while Dagg recounted the wingcats’ attack, unicorns and herons searching, finding only dead gryphons among the cliffs.

“They’ve killed our prince,” he concluded, voice hard. “It’s war. When spring returns, we must strike back.”

“Aye, vengeance! War!”

The whole herd took up the cry, whinnying and stamping in a frenzy of mourning. Korr tossed his head, pawing the air and smiting the ground. Ses wept softly. Lell looked frightened, anxious to suckle, but her mother fidgeted, too distracted to stand still. Withdrawn into herself, Tek scarcely heeded the clamor until all at once, Korr spun on her.

“So, healer’s daughter,” he demanded furiously, “how is it you alone keep silent? All around you mourn and rage against the gryphons’ treachery, yet you stand there cold.”

The pied mare stared at him.

“I have been three days weeping in the Pan Woods, king—as have all the band—and three days before that searching the Summer shore. I’ve wept me dry. I’ve no more tears to spill. My mate is dead! What more would you have of me?”

She found herself shouting by the end of it. She wished that she might shout until she dropped. The king drew himself up short, eyes white-rimmed suddenly.

“Your…mate?” he whispered.

Baffled, Tek nodded. “Aye.”

“My son?” cried Korr, voice rising. “My son—your mate?”

“Aye!” Tek flung back at him, angry and confused. “We danced the courting dance and pledged—”

Only then did she realize Dagg had begun his recounting on equinox morn, never mentioned who had paired with whom the night before. The king continued to stare at Tek, his breathing hoarse.

“You?” he choked. “You beguiled my son?”

“He chose me,” Tek answered. “And I him.”

Abruptly, she remembered the preceding spring: Korr’s odd but unmistakable disapproval whenever he had glimpsed the two of them in each other’s company.

“Seducer!” screamed the king, bolting toward her through the press of unicorns. “Cursed mare. Daughter of a renegade!”

Tek shied, crying out in astonishment. She had to scramble back to avoid Korr’s hooves as Dagg and his father, Tas, lunged to turn the huge stallion. Korr shouldered into Dagg, nearly knocking him to the ground. Tas, as tall as Korr, if leaner, threw his full weight against the king’s side and forced him to a halt.

Other unicorns crowded forward: her own father, Teki, as well as the king’s mate, Ses, and Dagg’s young dam, Leerah. The healer’s daughter looked on in consternation with the rest of the herd as the king, still shouting, strove to plunge past those who boxed him in.

“Temptress! Betrayer! Because of you my son is dead!”

“What are you saying?” Tek gasped. “I loved your son!”

“Liar! Outlaw’s get. Four summers unpaired, you lay in wait to destroy him!”

The pied mare shook her head in dismay as the king fought on, struggling to reach her, the look in his dark eyes murderous.

Not even Ses could still him.

“Alma will wreak her revenge—”

“Enough! Enough of this, my son.”

Startled, the king whirled, and the uproar around him abruptly ceased. Those blocking his path fell back a pace as Sa, the old king’s widow, emerged from the crowd.

“What means this frenzy?” Dark grey with a milky mane, she faced him, her expression full of pain and dismay. “You revile your slain heir’s widow as if she were your foe.”

The grey mare’s son stood panting. His dam waited. “Speak,” she said. “Why do you fly at one who has done you no injury?”

Panting still, Korr turned on Tek. Clearly he longed to fall on her even yet. Alert, watching him, the pied mare held her ground.

“No injury?” he growled. “You left my son to die upon the shore.”

The king gazed with open hatred at the healer’s daughter. “You should have stayed with him! Died with him—died for him. You were his…his mate!”

He choked on the word, as though it tasted filthy in his mouth. Fury sparked in Tek. She felt her eyes sting, her ribs lock tight. She had thought she had no tears left to shed.

“My son, you shame me.” Once more she heard the grey mare’s fierce rebuke. “You shame yourself and the office you hold. Tek is blameless in Jan’s death. Have done, I say.”

Swiftly, pointedly, she turned away. The king’s jaw dropped. The herd milled in astonished silence. Abruptly, Korr wheeled and bolted across the Vale. Unicorns scattered from his path, then stared after him, stunned. Tas glanced at Ses, but the king’s mate shook her head.

“Let him go,” she murmured. “Only time can cool him.”

Tek shuddered. She felt the pressure of Dagg’s shoulder solidly beside hers and leaned against it gratefully.

“Pay him no heed.” The dappled warrior spoke gently. “Our news came too suddenly. He’s mad for grief.”

“Come, child”—the late king’s widow turned to her—“my granddaughter now by Law. You are spent from tears and journeying. Rest in my grotto, until the dance.”

Trembling, Tek closed her eyes at the thought of Jan’s funeral train to be danced at dusk: a great slow procession used only for those of the prince’s line. The mourners, all smutched from rolling in the dust and hoarse from wailing, would call out, “He is dead! He is dead! He of the ancient line of Halla, dead!”

“He was my prince,” she muttered as she stumbled after Sa through the crowd toward the grey mare’s cave. “And faithfully I fulfilled his command—to get the others to the trees.” Her father, Teki, nuzzled her. Dagg flanked her other side. Tek swallowed hard. “Now Korr despises me.”

“Not so!” Dagg insisted. “How could he?”

They had reached the far slope of the Vale and started to climb. Sa glanced back as though to assure herself that they followed. The crowd behind them had begun to pull apart, the sound of their lamentations floating upward on the still morning air, making the pied mare shiver. The dappled warrior snorted.

“Korr’s always favored you highly. Truth, many’s the time he’s treated you better even than his own son!“

The healer chafed her gently, reassuringly. “The king will relent.”

But Tek shook her head, heaved a great sigh, painful against the crushing tightness of her breast. “Nay. Never. I should have stayed on the beach with Jan. I wish I had died instead of him.”

7.

Firekeepers

Days blended one into another, sometimes stormy, sometimes fair, but always cold. Fever consumed the dark unicorn. Often, he lay shuddering among the trees, too weak to rise. The mysterious voice spoke clearest to him then, urging him westward along the strand. It almost seemed that he himself were made of fire. More than once he came to awareness amid surroundings he did not recognize, certain that hours or days had passed of which he had no memory. Time wandered by in a dream.

Evening fell. Sun sank in a fiery blaze beyond the western horizon, the sky to the east grown dark as bilberries. Stars burned overhead, thinly veiled by fog. The full moon peering above the waves shone ghostly bright. Frowning, the dark unicorn stumbled to a halt. An amber glow flickered in the distance before him. As he left the strand and headed toward the dusky glimmer across the dunes, he caught a whiff of acrid, pungent scent. The sound of chanting reached his ears.

“Dai’chon!”

One clear voice sounded above the rest, calling urgently, ecstatic, echoed by a chorus of other, deeper voices.

“Dai’chon!” It was no tongue the dark unicorn recognized. He halted on the rim of a deep pit in the dunes, as though the hoof of some unaccountably vast being had dug a trough in the sand with a single sweep. Perhaps two or three dozen creatures hunched in a circle at the bottom of the pit. Smaller than unicorns, they were shaped like pans, with round heads and flat faces, their upper limbs not fashioned for the bearing of weight.

Their smooth, nearly hairless bodies were swathed in something that was neither plumage nor pelts. The dark unicorn’s nostrils flared. It smelled of seedsilk. He stared, fascinated by these two-footed creatures’ false skins. All of them knelt around a fire, its bright, reddish flames dancing over blackened driftwood. Grey tendrils of smoke curled upward through the misty air. The dark unicorn shivered.

“Dai’chon!

Dai’chon!” Chanting, the two-foots faced a stone embedded in the deepest part of the pit. The sand there was scorched, fused into glass. Deeply pocked and charred, the stone resembled a small, dark moon. The black unicorn recognized readily enough what it must be: a sky cinder. Such heavenly gifts were formed of a substance both harder and heavier than true stone, a substance that resounded with a clang when struck or stamped upon.

Before the sky cinder, a tiny figure stood, pale crescent marking the breast of its dark falseskin. Grasped in one black forelimb rose a long, sharp stake. From the other hung a vine, its end frayed into a flail. The figure’s limbs and torso resembled a two-foot’s, but its neck was thicker, longer, a brushlike mane cresting the ridge. The muzzle of its face was long and slim, like a hornless unicorn’s, with white teeth bared and red-flecked nostrils savagely flared.

Smoke rose from those nostrils. Astonished, the dark unicorn snorted, his own breath congealing in the cold, damp air. Strangely rigid, the little figure never moved. It smelled of fire and skystuff, not living flesh. Some object created by the two-foots? It must be hollow, he realized, its belly filled with burning spice.

Before it, the foremost of the two-foots rose and bowed. Green falseskins draped her. A crescent of silvery skystuff glinted upon her breast. The four kneeling nearest her were also females, the dark unicorn perceived by their scent, the remainder all hairy-faced males. Puzzled, the young stallion frowned. Why so many males, so few females? And where were their elders, their young? The eldest male, though grizzled, did not look much past the middle of his age.

“Dai’chon!” the green-clad female chanted, and the other twofoots echoed her,

“Dai’chon!” Forelimbs upraised, she beckoned her four companions, who rose. One by one, the males approached them, bearing seedpods and spicewood, dried foliage, and much else the dark unicorn could not identify. These the females laid carefully, as though in offering, at the feet of the little figure smoking before the sky cinder. What could the purpose of such a strange object be? the dark unicorn wondered.

The eldest of the males stepped forward with a great bunch of ripe, fragrant rueberries. The dark unicorn’s belly clenched at the sight and scent of food. He leaned after it longingly. Reaching to receive the gift, the moon-breasted female glanced up. Suddenly her eyes widened, and she gasped. The dark unicorn froze. Drawn by the delicious heat of the two-foots’ camp, he realized with a start, he had emerged unawares from the mist and shadows into the light of the fire.

The other females lifted their eyes. The males forming the circle before them turned. Abruptly, their chanting ceased. For five wild heartbeats, two-foots and unicorn stared at one another. Then the male crouching nearest the dark unicorn sprang up and bolted with a cry. Screaming, the leader’s four companions dropped their offerings and fled. With shouts of fear, the remaining males scrambled after them, dashed desperately up the steep sides of the sandpit and vanished into the fog.

The dark unicorn stood dumbstruck, dismayed. The camp below lay in disarray. Only the green-clad female remained, transfixed. The young stallion shifted nervously, nearly staggering from hunger and fatigue. Tossing the forelock back from his eyes, he switched his long, slim tail once against his flank, uncertain what best to do or say. Below him, the other’s gaze darted from his mooncrested brow to his steaming breath to his fly-whisk tail. Catching the firelight, the dark skewer of his horn glinted.

Behind her, the black figurine with its hornless unicorn’s head stood wreathed in smoke, its chest emblazoned with a silver crescent, the hornlike skewer clasped in one forepaw, the frayed vine dangling from the other. The two-foot leader’s words came in a rush.

“Dai’chon,” she whispered, crumpling to the ground. “Dai’chon!”

She pressed her forehead to the sand. Confused, the dark unicorn gazed at her. Had she collapsed from fear? Unsteadily, he descended the pit’s sandy, glassy slope and nosed her gently. The black hair on her head smelled clean and very fine, like a new colt’s mane. Trembling, she raised her head. Carefully, he tried to repeat her words.

“Taichan,” he managed, but his mouth found the strangely inflected syllables almost impossible to frame. He tried again: “Daijan.”

“Tai-shan?” the other said suddenly.

She touched the moon image upon her breast and gazed at the pale crescent underscoring the horn on his brow.

“Tai-zhan,” he tried, finding that a bit easier. “Tai-shan.”

The creature before him listened, rapt. The dark unicorn snorted, not pleased with his awkwardness. The two-foot language was full of odd chirps and grunts.

“Forgive me,” he told her, reverting to his own tongue. “I mean you no harm.“

The crackling blaze of the fire drew him. He stepped nearer, trembling with cold. The two-foot made no move to halt him, only gazed at him as though spellbound. Dried fruit, fragrant seed grass, and other offerings lay strewn about the sand. Hungrily, the dark unicorn eyed the tempting stuff.

“May I share your forage?” he asked. “I’ve found little but bitter bark and shoreoats for…for many days.”