The yellow lantern-lights of Mainz's dockside inns reached out across the dark Rhine. Standing on the prow of the riverboat, Erik Hakkonsen stared at them, thinking of little more than food and a bed. He'd left his home in Iceland three weeks earlier, to answer the Emperor's summons. They'd had a stormy crossing. Then the late spring thaw had ensured that the roads of the Holy Roman Empire were fetlock deep in glutinous mud. And, finally, the river had been full and the rain steady. Tomorrow he would have to go to the Imperial palace, and find out how to seek an interview with Emperor Charles Fredrik.

But tonight he could sleep.

The riverboat nudged into the quay. A wet figure stepped out from under the eaves of the inn. "Is there one Erik Hakkonsen on this vessel?" he demanded, half-angrily. The rain hadn't been kind to the skinny courtier's bright cloak. The satin clung to him, and he was shivering.

Erik pushed back his oilskin-hood. "I'm Hakkonsen."

"Thank God for that! I'm soaked to the skin. I've been here for hours," complained the man. "Come. I've got horses in the stable. The Emperor awaits you."

Erik made no move. "Who are you?"

The fellow shivered. "Baron Trolliger. The Emperor's privy secretary." He held out his hand to show a heavy signet. It was incised with the Roman Eagle.

That was not a seal anyone would dare to forge. Erik nodded. "I'll get my kit."

The shivering baron shook his head. "Leave it." He pointed to the sailor who had paused in his mooring to stare. "You. Watch over this man's gear. Someone will be sent for it."

As much as anything else, the alacrity with which the sailor obeyed the order drove home the truth to Erik. He was in the heart of the Holy Roman Empire, for a certainty. In his native Iceland—or Vinland, or anywhere else in the League of Armagh—that peremptory order would have been ignored, if not met with outright profanity.

"Come," the baron repeated. "The Emperor is waiting."

Passing from the narrow dark streets and sharp-angled tall houses into the brightness of the imperial palace, Erik had little time to marvel and gawk at the heavy gothic splendor of it all. Instead, Baron Trolliger rushed him through—still trailing mud—into a large austere room. As soon as Erik entered, the baron closed the door behind him, not entering himself.

In the center of the room, staring at Erik, stood the most powerful man in all of Europe. He was a large man, though now a bit stooped from age. His eyebrows seemed as thick and heavy as the purple cloak he was wearing; his eyes, a shade of blue so dark they almost matched the cloak.

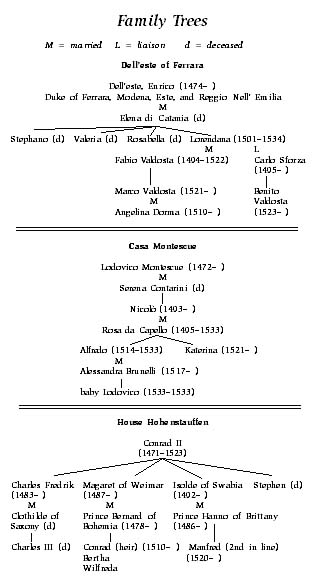

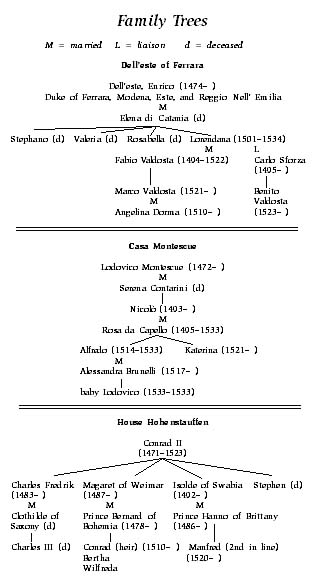

Charles Fredrik. The latest in a long line of Hohenstauffens.

Guardian of the Church, Bulwark of the Faith. Lord of lands from northern Italy to the pagan marches in the Baltic. Ruler over millions of people throughout central Europe.

The Holy Roman Emperor, himself. In direct line of descent from the great Fredrick Barbarossa.

All of that mattered little to Erik. His tie to the Emperor was a clan tie, not a dynastic one. He was there to become the Emperor's servant, not his subject. So, Erik simply bowed to the old man, rather than kneeling, and spoke no words of fealty. Simply the old oath: "Linn gu linn."

The words were Gaelic, but the oath that bound him came from the cold fjells of pagan Norway. An oath that went back generations, to the time when a Hohenstauffen prince had rescued a pagan clan from demons set loose by their own foolishness.

Charles Fredrik spoke like an old man—despite being no older than Erik's father. But he voiced the ritual words strongly. "From generation to generation."

He held out the dagger that Erik had heard described with infinite care all his life. The dagger was iron. Old iron. Sky iron. Hammered with stone in the pagan Northlands, from a fallen thunderbolt. The hilt was shaped into a dragon head—the detail lost in the blurring of hundreds of years of use.

It still drew blood for the blood-oath like new steel did. "Blood for blood. Clan for clan." Erik renewed the oath calmly.

After binding their wounds himself, Charles Fredrik took Erik by the elbow and led him across to a window. The window was a mere arrow-slit, testimony to the palace's ancient origins. Against modern cannon, such fortifications were almost useless. But . . . there was a certain undeniable, massive dignity to the huge edifice.

There they stood, silent for some time, looking out at the scattered shawl of lights which was the great sleeping city of Mainz. Erik was quite sure that those lights represented more people than lived in all Iceland. Their lives, and those of many more, rested in the hands of the old man standing next to him.

The Emperor seemed to have read his thoughts. "It is a great load, at times," he said softly.

His heavy jaws tightened. The next words were spoken almost harshly. "I have called for the Clann Harald because my heirs have need. My son is . . . very sickly. And I do not expect my only surviving brother to outlive me. Not with his wounds. So I must take special care to watch over my two nephews, for it is quite likely that one of them will succeed to the throne after I am gone."

The Emperor sighed. "Your older brother Olaf watched over my nephew Conrad for his bond-time, as your father Hakkon watched over me." A slight smile came to his face. "To my surprise, I find I miss him. He used to beat me, you know."

"He has told me about it, Godar of the Hohenstauffen." Erik did not add: Often.

Charles Fredrik's smile broadened. "According to your brother Olaf—'often.' " He chuckled. "It did me the world of good, I eventually came to realize. Nobody had dared punish me before that. Do you know that your family are the only people in the world who don't call me 'Emperor,' or 'Your Imperial Highness?' I think it is why we trust you."

"Our loyalty is to the Godar of the Hohenstauffen. Not to the Empire." That too his father had said. Often.

"You must sit and tell me the news of them once I have given you your task. I warn you, it will be a more onerous chore than Olaf's. Manfred, my younger nephew, reminds me of myself at that age. You will have to—as your father did with me—serve as confrere in the monastic order of the Knights of the Holy Trinity. Of course—as then—your identity and purpose must remain secret. Manfred's also."

Erik nodded. "My father has told me about the Knights."

The Emperor's eyes narrowed. "Yes. But things have changed, Hakkonsen. It is one of the things that worries me. The Knights have always been—nominally, at least—independent of the Empire. Servants of God, not of any earthly power. In practice they have served as the Empire's bulwarks to the North and East. In your father's day the nobility from all the corners of the Holy Roman Empire came to serve as the Knights of Christ, in the pious war against the pagan. And many brave souls came from the League of Armagh, not just the handful of Icelanders sworn by clan loyalty to the service of the Emperor."

Erik nodded again. "My grandfather says that in his day, Aquitaines made up as many as a quarter of the order's ranks."

The Emperor clenched his fist, slowly. "Exactly. Today, no knight from that realm would dream of wearing the famous tabard of the Knights of the Holy Trinity. Once the brotherhood Knights were truly the binding threads in the cloak of Christianity. Today . . . the Knights of the Holy Trinity come almost entirely from the Holy Roman Empire. Not even that. Only from some of its provinces. They're Prussians and Saxons, in the main, with a small sprinkling of Swabians. A few others."

He paused. Then he looked Erik in the eyes. "They're beginning to take an interest in politics. Far too much for my liking. And they're also—I like this even less—getting too close to the Servants of the Holy Trinity. Damn bunch of religious fanatics, that lot of monks."

Charles Fredrik snorted. "All of it, mind you, supposedly in my interests. Some of them probably even believe it. But I have no desire to get embroiled in the endless squabbling of Italian city-states, much less a feud with the Petrine branch of the church. The Grand Duke of Lithuania and King Emeric of Hungary give me quite enough to worry about, leaving aside the outright pagans of Norseland and Russia."

Again, he sighed. "And they're not a binding force any more. Today, the common people call the church's arm militant 'The Knots,' more often than not. And, what's worse, the Knights themselves seem to relish the term."

"The Clann Harald do not mix in Empire politics," stated Erik firmly. His father had warned him that this might happen.

The Emperor gave a wry smile. "So your father always said. Just as I'm sure he warned you before you left Iceland. But, Erik Hakkonsen, because you guard Manfred . . . do not think you will be able to avoid it. Any more than your father could."

The old man turned and faced Erik squarely. "Politics will mix with you, lad, whether you like it or not. You can be as sure of that as the sunrise. Especially in Venice."

Erik's eyes widened. The Emperor chuckled.

"Oh, yes. I forgot to mention that, didn't I?"

He took Erik by the arm again and began to lead him toward the door. "But we can discuss Venice tomorrow. Venice, and the expedition of the Knights to that city, which you will be joining. An expedition which I find rather . . . peculiar."

They were at the door. By some unknown means, a servant appeared to open it for them. "But that's for tomorrow," said the Emperor. "What's left for tonight, before you get some well-deserved rest, is to meet the cross you must bear. I suspect the thought of Venice will be less burdensome thereafter."

About halfway down the long corridor leading to the great staircase at the center of the palace, he added: "Anything will seem less burdensome, after Manfred."

It took the Emperor, and quite a few servants, some time to track down Manfred. Eventually the royal scion was discovered. In the servants' quarters, half-drunk and half-naked, sprawled on a grimy bed. Judging from the half-sob and half-laugh coming from under the bed, Manfred and the servant girl had been interrupted in a pastime which boded ill for the prince's hope of attaining heaven without spending some time in purgatory.

Erik studied the young royal, now sitting up on the edge of the bed. Manfred was so big he was almost a giant, despite being only eighteen years old. Erik was pleased by the breadth of shoulders, and the thick muscle so obvious on the half-clad body. He was not pleased with the roll of fat around the waist. The hands were very good also. Thick and immensely strong, clearly enough, but Erik did not miss the suggestion of nimbleness as the embarrassed royal scion hastily buttoned on a cotte.

He was pleased, also, by the evident humor in the prince's eyes. Bleary from drink, true, but . . . they had a sparkle to them. And Erik decided the square, block-toothed grin had promise also. Whatever else Prince Manfred might be, he was clearly not a sullen boy.

It remained to be seen how intelligent he was. There, Erik's hopes were much lower.

The Emperor, standing in the doorway of the servant's little room, cleared his throat. "This is your Clann Harald guardian, you young lout. You'll have to mind your manners from now on."

The prince's huge shoulders seemed to ripple a bit, as if he were suppressing a laugh.

"This—willow? Uncle! The way you always described these Icelandic sheep farmers, I got the impression—"

Manfred gasped, clutching his belly. Erik's boot had left a nice muddy imprint. The prince choked, struggling for breath.

"You stinking—" he hissed. A moment later the prince was hurling himself off the bed, great arms stretched wide. Erik was pleased by the rapid recovery. Just as he had been when his driving foot hit the thick muscle beneath the belly fat.

Manfred's charge would have driven down an ogre. Unfortunately, ogres don't know how to wrestle. Erik had learned the art from an old Huron thrall on the Hakkonsen steading, and polished it during his three years in Vinland—much of which time he had spent among his family's Iroquois relatives.

Manfred flattened nicely against the stone wall, like a griddle cake. The palace almost seemed to shake. The prince himself was certainly shaking, when he staggered back from the impact.

Not for long. Erik's hip roll brought him to the floor with a crash, flat on his back. The knee drop in the gut half-paralyzed the prince; the Algonquian war hatchet held against the royal nose did paralyze him. Manfred was almost cross-eyed, staring at the cruel razor-sharp blade two inches from his eyes.

"You'll learn," grunted the Emperor. "Give him a scar. He's overdue."

Erik's pale blue eyes met Manfred's brown ones. He lifted an eyebrow.

"Which cheek, Prince?" he asked.

Manfred raised a thick finger. "One moment, please," he gasped. "I need some advice."

The prince rolled his head on the floor, peering under the bed. "You'd better decide, sweetling. Right or left?"

A moment later, a girlish voice issued from under the bed. "Left."

The prince rolled his head back. "The left, then."

Erik grinned; the hatchet blurred; blood gushed from an inch-long gash. He was still grinning when he arose and began wiping off the blade.

"I think the prince and I will get along fine, Emperor."

The most powerful man in Europe nodded heavily. "Thank God for that." He began to turn away. "Tomorrow, we will speak about Venice."

"No politics," insisted Erik.

There was no response except a harsh laugh, and the sight of a broad purple back receding into the darkness.

"Come, brothers," said the slightly-built priest who limped into the small chapel where his two companions awaited him. "The Grand Metropolitan has made his decision."

One of the other priests cocked his head quizzically. "Is it the Holy Land, then, as we hoped?"

"No. Not yet, at least. He has asked us—me, I should say—to go to Venice."

The third priest sighed. "I begin to wonder if we will ever make our pilgrimage, Eneko." The Italian words were slurred, as always, with Pierre's heavy Savoyard accent.

The small priest shrugged. "As I said, the Grand Metropolitan only requires me to go to Venice. You—you and Diego both—are free to carry out the pilgrimage we planned."

"Don't be a typical Basque fool," growled Pierre. "Of course we will accompany you."

"What would you do without us?" demanded Diego cheerfully. Again, he cocked his head. "Yes, yes—granted you are superb in the use of holy magic. But if it's Venice, I assume that's because of the Grand Metropolitan's scryers."

"Do those men ever have good news to report?" snorted Pierre.

The Basque priest named Eneko smiled thinly. "Not often. Not since Jagiellon took the throne in Vilna, that's certain."

Pierre scowled. "Why else would we be going to that miserable city?"

Eneko gazed at him mildly. "I wasn't aware you had visited the place."

Pierre's scowl deepened. "Not likely! A pit of corruption and intrigue—the worst in Italy, which is bad enough as it is."

The Basque shrugged. "I dislike the city myself—and, unlike you, I've been there. But I don't know that it's any more corrupt than anywhere else." Then, smiling: "More complicated, yes."

Diego's head was still cocked to one side. The mannerism was characteristic of the Castilian. "Eneko, why—exactly—are we going there? It can't be simply because of the scryers. Those gloomy fellows detect Lithuanian and Hungarian schemes everywhere. I'm sure they'd find Chernobog rooting in the ashes of my mother's kitchen fire, if they looked long enough."

"True enough," agreed Eneko, smiling. "But in this instance, the matter is more specific. Apparently rumors have begun to surface that the Strega Grand Master was not murdered after all. He may still be alive. The Grand Metropolitan wants me to investigate."

The last sentence caused both Diego and Pierre to frown. The first, with puzzlement; the second, with disapproval.

"Why is it our business what happens to a pagan mage?" demanded Pierre.

Again, Eneko bestowed that mild gaze upon the Savoyard. "The Church does not consider the Strega to be 'pagans,' I would remind you. Outside our faith, yes. Pagans, no. The distinction was implicit already in the writings of Saint Hypatia—I refer you especially to her second debate with Theophilus—although the Church's final ruling did not come until—"

"I know that!" grumbled Pierre. "Still . . ."

Diego laughed. "Leave off trying to teach this stubborn Savoyard the fine points of theology, Eneko. He knows what he knows, and there's an end to it."

Eneko chuckled; and so, after a moment, did Pierre himself. "I suppose I still retain the prejudices of my little village in the Alps," he said grudgingly. "But I still don't understand why the Holy Father is making such an issue out of it."

"Pierre," sighed Diego, "we are not talking about some obscure witch-doctor. Dottore Marina was considered by every theologian in the world, Christian or not—especially those versed in the use of magic—to be the most knowledgeable Strega scholar in centuries. He was not simply a Magus, you know. He was a Grimas, a master of all three of the stregheria canons: Fanarra, Janarra and Tanarra. The first Grimas since Vitold, in fact."

"And we all know how that Lithuanian swine wound up," growled Pierre. His Savoyard accent was even heavier than usual.

Eneko's eyebrows, a solid bar across his forehead, lowered. "Pierre! I remind you—again—that the Church does not extend its condemnation of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania onto their subjects."

The Savoyard priest looked away. Then, nodded acknowledgement of the justice of the reproof.

"Besides," continued the Basque, "the criticism is unfair in any event. Vitold's fate derived from his boldness, not from sin. Rashness, if you prefer. But I remind you—"

Eneko's stern gaze swept back and forth between his two companions. "I remind you, brothers, that we have set ourselves the same purpose as that of doomed Vitold—to stand firmly against Chernobog and all manner of evil."

For a moment, his eyes roamed the austere interior of the chapel. Finding comfort there, perhaps, but not forgetting how long it had taken them to find such a chapel in Rome.

"To challenge it on the field of holy battle," he continued softly, "instead of lolling in comfort while our Pauline brethren wage the struggle alone."

Hearing the Paulines referred to as "brethren" brought a momentary tightness to Pierre's lips, but the Savoyard did not challenge the term. As often as Eneko Lopez's odd views grated on the Savoyard's upbringing and attitudes, he had long since made the decision to follow the man anywhere he chose to lead them.

As had Diego. "Well enough, Eneko. Venice it is. And we should send for Francis in Toulouse as well. He would be invaluable in Venice, dealing with Strega."

Lopez shook his head. "No," he said firmly. "I want Francis to go to Mainz and try to get an audience, if he can, with the Emperor. I'm not certain yet, but I think he will be far more useful there than he would be in Venice with us."

The Basque priest's words caused his two companions to stiffen. Again, Diego made that cocked-head quizzical gesture. "Am I to take it that the Grand Metropolitan is looking more favorably on our proposal?"

Lopez shrugged. "He keeps his own counsel. And he is a cautious man, as you know. But . . . yes, I think so. I suspect he views this expedition to Venice as something in the way of a test. So do I, brothers. And if I'm right as to what we will find there, we will need a private conduit with Charles Fredrik."

Those words cheered Pierre immediately. "Well, then! By all means, let's to Venice!"

The next morning, as they led their mules through the streets of Rome, the Savoyard finally unbent enough to ask the question again. This time, seeking an answer rather than registering a protest.

He did it a bit pugnaciously, of course.

"I still don't understand why we're looking for a Strega scholar."

"We are not," came Eneko's firm reply. "We are soldiers of God, Pierre, not students. Battle is looming, with Venice as the cockpit—on that every holy scryer in the Vatican is agreed. We are not looking for what the scholar can explain, we are looking for what the mage can summon. Perhaps."

Pierre's eyes widened. Even as a boy in a small village in the Alps, he had heard that legend.

"You're joking!" he protested.

Eneko gazed at him mildly, and said nothing. It was left to Diego to state the obvious.

"He most certainly is not."

Not for the first time, the shaman thought longingly of the relative safety of the lakes and forests of Karelen from which he had come. It required all his self-control to keep from trembling. That would be disastrous. His master tolerated fear; he did not tolerate a display of it.

As always in his private chambers, Jagiellon was not wearing the mask which the Grand Duke wore in his public appearances. Jagiellon was officially blind—due to the injuries he had suffered in his desperate attempt to save his father from the assassins who murdered him. Such, at least, was Jagiellon's claim. The shaman doubted if very many people in Lithuania believed that tale; none at all, in the capital city of Vilna. Most of the populace of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Poland were quite certain that Jagiellon had organized his father's murder in order to usurp the throne.

Few of them cared, in truth. Succession in Lithuania was often a bloody affair, to begin with, and in the four years since he ascended to the throne Jagiellon had made it quite clear that he was even more ruthless than his father had been.

But, if they doubted his other claim, few Lithuanians doubted Jagiellon's claim of blindness. Indeed, they took a certain grim satisfaction in the knowledge. Jagiellon was more savage than his father, true—but at least the father had managed to blind the son before succumbing to the usurpation. Not surprising, really. Jagiellon's father had been as famous with a blade as Jagiellon himself.

The shaman suffered from no such delusion. In the time since he entered the grand duke's service, the shaman had realized the truth. Jagiellon had made his way to the throne by delving into magic even blacker than his father had been willing to meddle with. And . . .

Had delved too deeply. The demon Jagiellon had thought to shackle to his service had been too powerful for the rash and ambitious young prince. And so, while Jagiellon had indeed lost his eyes, that loss had been the least of it.

Eyes were still there, after all. Easily seen—naked and visible—with the mask removed. But they were no longer Jagiellon's eyes, for all that they rested in Jagiellon's face.

The eyes were black, covered with eyelids so fat and heavy they turned the orbs into mere slits. But the shaman could see them well enough. Far too well. Those eyes had neither pupils nor irises, nor any trace of white eyeball. Ebony-colored and opaque; uniform throughout; appearing, at first, like two agates—until, deep within, the emptiness could be sensed. As if stones were really passageways into some place darker than any night.

"Do it," commanded Grand Duke Jagiellon, and his huge hand swept across the floor, re-opening the passage.

Stifling a whimper of protest, the shaman underwent the shape-change again. As always, the transition was accompanied by agony—and even more so the passage through which his master sent him. But those agonies were familiar things. The source of the shaman's terror lay elsewhere.

Nor did the terror stem from the lagoon itself, as much as the shaman despised the stink of the waters—in his new form even more than he would have in his human one. His fishlike body swam through the murky shallows, nosing the scents drifting through the mud swirls and reeds.

He detected the mage soon enough, as familiar as he now was with that scent. Again, as before, the odor was very faint. The mage remained near water at all times, but rarely ventured into it. To do otherwise would have been dangerous.

More dangerous to leave the water's vicinity than to enter it, in truth. The shaman's jaws gaped wide, displaying teeth that could rend human flesh easily. But the display was more for the purpose of driving away the shaman's own fear than any prospect of savaging the mage. The mage had protectors in these waters. The shaman was not the only thing swimming there which possessed sharp teeth.

And there were worse perils than teeth, anyway. Much worse. It was to detect the greatest of those perils that Jagiellon had sent the shaman back—again and again—to scour the waters of Venice and the Jesolo.

Keeping a wary eye out for undines, the shaman swam for two hours before turning away from the marshes. He made no attempt to cut short his investigation. Jagiellon would be watching him. The grand duke could see through that magic passageway as well as send the shaman through it—or return the shaman to the palace in Vilna, in the event of disobedience. Once given to Jagiellon's service, escape was impossible for the servant.

For the same reason, the shaman did not stint in his ensuing search through the canals of the city. That search also lasted a full two hours, despite the fact that the shaman hated the canals even more than the marsh waters. True, the canals were not as dangerous. Undines rarely ventured into the city. But the stench of human effluvia sickened the shaman. He was, in the end, a creature born and bred in the wilderness of Finland. Civilization nauseated him.

Enough. Even for Jagiellon—even for the thing which Jagiellon truly was—this was enough. The shaman swam back into the open sea and waited for his master's summons.

The summons came soon enough, and the shaman underwent the agony. Almost gaily, now that he knew he had escaped once again from the peril which lurked in Venice. The Lion still slumbered.

Fear returned quickly, however. Great fear, once the grand duke explained his new plan.

"You would do better to use the broken god," the shaman said softly, trying his best to keep the whine out of his voice. Simply a counselor, offering sage advice.

In the end, his master took the advice. But not before flaying the shaman. Jagiellon's conclusion rested on the frailty of shamans as compared to simple monsters. He accepted the fact; punished the frailty.

The next day, the new shaman was summoned to an audience in the grand duke's private quarters. The shaman, just arrived in Vilna, was also from the lakes and forests of Karelen. The grand duke was partial to that breed of Finns, especially for water work.

"Sit," commanded Jagiellon, pointing a huge finger at the heavy table in the center of the kitchen.

The shaman stared. Whatever else he had expected, the shaman had never thought to see the ruler of Lithuania cooking his own meal over a stove. The sight was incongruous. Erect, in his heavy robes of office, Grand Duke Jagiellon seemed as enormous as a bear. The ease and agility with which those great thick hands stirred food frying in a pan was equally incongruous.

Despite his astonishment, the shaman obeyed instantly. Jagiellon was . . . famous.

Grunting softly, the grand duke removed the pan from the stove and shoveled a portion of its contents onto a wooden platter. Then, as if he were a servant himself, laid the plate before the shaman.

"Eat. All of it. If your predecessor poisoned himself, I will need to discard the rest. Which would be a pity. It's one of my favorites dishes."

The shaman recognized the . . . food. Fortunately, he managed not to gag. More fortunately still, he managed to choke it all down. As he ate, he was aware of Jagiellon moving to the door and opening it, but did not dare to watch. Jagiellon was . . . famous.

When the shaman was done with the meal, Jagiellon's huge form loomed beside him again. "Take the platter with you to your quarters," commanded the grand duke, his heavy voice sliding out the words like ingots from a mold. "Do not clean it. Display it prominently. It will help you to remember the consequences of failure."

The shaman bobbed his head in nervous obedience.

"My project in Venice will require subtlety, shaman, lest the spirit that guards the city be roused from its slumber. That is why I summoned you here. My last shaman was subtle enough, but he lacked sufficient courage. See to it that you have both."

The shaman was confused. He had heard of Venice, but knew nothing about the city. Somewhere in Italy, he thought.

"I will explain later. Go now. You may take this with you also. It will remind you of the consequences of success."

As he rose from the table, clutching the platter, the shaman beheld a woman standing next to the grand duke. She was very beautiful.

"You will not have the use of it for long," warned the grand duke. "Soon enough, the thing must be sent off to Venice."

The shaman bobbed his head again; more with eagerness, now, than anxiety. The shaman was not given to lingering over such pleasures, in any event. In that, too, he was a creature of the wilderness.

By the time he reached his chambers, the woman following obediently in his wake, the shaman had come to realize that she was no woman at all. Simply the form of one, which his master had long since turned into his vessel.

The shaman did not care in the least. A vessel would serve his purpose well enough; and did so. But the time came, his lust satisfied, when the shaman rolled over in his bed and found himself staring into an empty platter instead of empty eyes. And he wondered whether he had made such a wise decision, answering the summons of the Grand Duke of Lithuania.

Not that he had had much choice, of course. Jagiellon was . . . famous.

Each hammer blow was a neat, precise exercise of applied force. Enrico Dell'este loved this process, this shaping of raw metal into the folded and refolded blade-steel. His mind and spirit found surcease from trouble in the labor. At the moment, as for the past several years, he needed that surcease. Needed it badly.

Besides, a duke who worked steel was intensely popular among his steelworking commons. Duke Dell'este, Lord of Ferrara, Modena, Este, and Reggio nell'Emilia, needed that also. Ferrara stood between too many enemies in the shifting morass of Italian politics in the year of our Lord 1537. Ferrara had no natural defenses like Venice, and no great allies. All it had was the Duke Enrico Dell'este—the Old Fox, as his populace called him—and the support of that populace.

A page entered the forge-room. Shouted above the steady hammering. "Milord. Signor Bartelozzi is here to see you. He awaits you in the sword salon."

The duke nodded, without stopping or even looking up from his work. "Antimo will wait a few moments. Steel won't." He forced himself to remain calm, to finish the task properly. If Antimo Bartelozzi had bad news he would have sent a messenger, or simply sent a letter. The fact that he needed to talk to the duke . . .

That could only mean good news about his grandchildren. Or news which was at least hopeful.

Dell'este lifted the bar of hammered metal with the tongs and lowered it into the quenching tank. He nodded at the blacksmith standing nearby, who stepped forward to continue the work. The duke hung his tools neatly and took the towel from the waiting factotum. "The Old Fox," he murmured, as he dried the sweat. "Tonight I just feel old."

The room the duke entered was spartan. Stone-flagged, cool. Its only furnishings a wooden table which leaned more to sturdiness and functionality than elegance; and a single chair, simple and not upholstered. Hardly what one would expect the lair of the Lord of the cities of Ferrara, Este, Modena, and Reggio nell' Emilia to look like. On the wall above the fireplace was a solitary piece of adornment. And that was absolutely typical of Dell'este. It was a sword, hung with crimson tassels. The pommel showed faint signs of generations of careful polishing. The wall opposite the fireplace contained an entire rack of such weapons.

The Old Fox sat at the table and looked at the colorless man standing quietly in the corner. Antimo Bartelozzi had the gift of being the last person in a crowd of two that you'd ever notice. He was also utterly loyal, as the duke well knew. Bartelozzi had had ample opportunity to betray the Dell'este in times past.

The duke used other spies and agents for various other tasks. Antimo Bartelozzi was for family affairs. To the duke that was the only thing more precious than good sword-steel.

"Greetings, Antimo. Tell me the worst."

The lean gray-haired man smiled. "Always the same. The worst first. The 'worst' is that I did not find them, milord. Either one. Nor do I have knowledge of their whereabouts."

The Old Fox shuddered, trying to control the relief which poured through him. "My grandsons are alive."

Bartelozzi paused. "It's . . . not certain. To be honest, milord, all I've established is that Marco Valdosta was last seen the night your daughter Lorendana was killed. And I had established that much two years ago. But I did find this."

The duke's agent reached into a small pouch. He handed over a small, sheathed knife, whose pommel was chased and set with an onyx. "This dagger is a signed Ferrara blade that turned up in the thieves market at Mestre. The seller was . . . questioned. He admitted to having bought it from one of the Jesolo marsh-bandits."

The duke hissed between his teeth. He took the blade and unscrewed the pommel. Looked at the tiny marks on the tang. "This was Marco Valdosta's blade." He looked at the wall. At the empty space next to one of the hereditary blades on its rack. The space for a small dagger given to a boy, next to the sword—still in its place—destined for the man. His grandson Marco's blades.

"And you don't take this as another bad sign? Perhaps whoever stole the dagger from him killed the boy." The Old Fox eyed Bartelozzi under lowered eyebrows. "You found one of the bandits. Questioned him."

Antimo nodded. "They robbed the boy, yes. Beat him badly. Badly enough that the bandits assumed he would not survive. But . . . there are rumors."

"The Jesolo is full of rumors," snorted Dell'este. "Still, it's something."

He moved toward the blade-rack. "Tell me that I can return it to its place, Antimo. You know the tradition."

Behind him, he heard a little noise. As if Bartelozzi was choking down a sarcastic reply. The duke smiled grimly.

" 'No Ferrara blade, once given to a Dell'este scion, may be returned until it is blooded.' You may hang it in the rack, milord. That blade is well and truly blooded. I slid the bandit into the water myself. The thief-vendor also. There was barely enough blood left in them to draw the fish."

Dell'este hung the dagger and turned back. "And the younger boy? Sforza's bastard?"

Antimo Bartelozzi looked decidedly uncomfortable. "Milord. We don't know that the condottiere was his father."

"Spare me," growled the duke. "My younger grandson was the spitting image of Sforza by the time he was ten. You knew my slut daughter, as well as I did. She was enamored of all things Milanese, and Sforza was already then the greatest captain in Visconti's service."

Antimo studied Dell'este for a moment, as if gauging the limits of his master's forbearance. It was a brief study. For Bartelozzi, the Old Fox's limits were . . . almost nonexistent.

"That is a disservice to her memory, milord, and you know it perfectly well. To begin with, her devotion was to the Montagnard cause, not to Milan. Your daughter was a fanatic, yes; a traitor . . . not really."

The duke's jaws tightened, but he did not argue the point. Bartelozzi continued:

"Nor was she a slut. Somewhat promiscuous, yes; a slut, no. She rebuffed Duke Visconti himself, you know, shortly after she arrived in Milan. Quite firmly, by all accounts—even derisively. A bold thing for a woman to do, who had cast herself into Milan's coils. That may well have been the final factor which led Visconti to have her murdered, once she had fallen out of favor with her lover Sforza. Not even Visconti would have been bold enough to risk his chief military captain's anger."

Dell'este restrained his own anger. It was directed at the daughter, anyway, not the agent. Besides, it was an old thing, now. A dull ember, not a hot flame. And . . . that core of honesty which had always lain at the center of the Old Fox's legendary wiliness accepted the truth of Bartelozzi's words. The duke's daughter Lorendana had been headstrong, willful, given to wild enthusiasms, reckless—yes, all those. In which, the duke admitted privately, she was not really so different from the duke himself at an early age. Except that Enrico Dell'este had possessed, even as a stripling prince, more than his share of acumen. And . . . he had been lucky.

Bartelozzi was continuing. "All we know about the younger boy is what we learned two years ago. He was thrown out of Theodoro Mantesta's care once the true story of Lorendana's death leaked out. Mantesta, not surprisingly, was terrified of Milanese assassins himself. Your youngest grandson seems to have then joined the canal-brats."

"Damn Mantesta, anyway—I would have seen to his safety." For a moment, he glowered, remembering a night when he had slipped into Venice incognito. The Duke of Ferrara was no mean bladesman himself. Theodoro Mantesta had been almost as terrified of him as he had been of Milanese assassins. Almost, but . . . not quite. And for good reason. In the end, Dell'este had let him live.

The Old Fox waved his hand irritably. "I know all this, Antimo! Shortly thereafter, you discovered that a child very like him, from the poor description we had, was killed about three weeks later. And while it wasn't certain—hundreds of poor children live under the bridges and pilings of Venice—it seemed logical enough that the victim was my youngest grandson. So tell me what you have learned since, if you please."

Antimo smiled. "What I have learned since, milord, is that the boy whose throat was slit had actually died of disease the day before."

The duke's eyes widened. "Who would be that cunning? Not my grandson! He was only twelve at the time."

"Two ladies by the name of Claudia and Valentina would be that cunning, milord." Bartelozzi shook his head. "You would not know them. But in their own circles they are quite famous. Notorious, it might be better to say. Tavern musicians, officially—excellent ones, by all account—but also thieves. Excellent thieves, by reputation. And according to rumor, shortly thereafter the two women gained an accomplice. A young boy, about twelve. I've not laid eyes on him myself, mind you—neither have any of my agents. The boy seems to have been well trained in stealth. But I have gotten a description, quite a good one. In fact, the description came from a former mercenary in Sforza's service. 'Could be one of the Wolf's by-blows,' as he put it. 'Lord knows he's scattered them across Italy.' "

The Duke of Ferrara closed his eyes, allowing the relief to wash over him again. It made sense, yes—it all made sense. His youngest grandson had been a wily boy—quite unlike the older. As if all of the legendary cunning of Dell'este had been concentrated in the one, at the expense of the other. Combined, alas, with the amorality of the father Sforza. Even when the boy had been a toddler, the duke had found his youngest grandson . . . troubling.

His musings were interrupted by Bartelozzi. Antimo's next words brought the duke's eyes wide open again.

"The two women who may have succored your grandson are also reputed to be Strega. Genuine Strega, too, not peddlers and hucksters. The reputation seems well founded, from what I could determine."

"Strega? Why would they care what happened to the bloodline of Valdosta and Dell'este?"

Bartelozzi stared at him. After a moment, Dell'este looked away. Away, and down. "Because Venice is the best refuge of the Strega," he answered his own question. "Has been for centuries. If Venice falls . . ."

A brief shudder went through his slender but still muscular body. "I have been . . . not myself, Antimo. These past two years. All my offspring dead . . . it was too much."

His most trusted agent's nod was one of understanding. But pitiless for all that.

"You have other offspring, milord. Of position if not of blood. All of Ferrara depends upon you. Venice too, I suspect, in the end. There is no leadership in that city that can compare to yours. If you begin leading again, like a duke and not a grieving old man."

Dell'este tightened his lips, but accepted the reproof. It was a just one, after all.

"True," he said curtly. Then, after a moment, his lips began to curve into a smile. Hearing Bartelozzi's sigh of relief, he allowed his smile to broaden.

"You think it is time the Old Fox returned, eh?"

"Past time," murmured Bartelozzi. "The storm clouds are gathering, milord. Have been for some time, as you well know. If Venice is destroyed, Ferrara will go down with it."

The Duke of Ferrara began pacing about. For all his age, there was a spryness to his steps. "Venice first, I think. That will be the cockpit."

He did not even bother to glance at Bartelozzi to see his agent's nod of agreement. So much was obvious to them both. "Which means we must find an anchor of support in the city. A great house which can serve to rally the populace of Venice. The current quality of Venetian leadership is dismal, but the population will respond well—as they have for a thousand years—if a firm hand takes control." He sighed regretfully. "Doge Foscari was capable once, and still has his moments. But—he is too old, now."

"If either of your grandsons is alive . . ."

The Old Fox shook his head firmly. "Not yet, Antimo. Let our enemies think the ancient house of Valdosta is well and truly destroyed. That will be our secret weapon, when the time comes. For the moment—assuming they are still alive—my grandsons are far safer hidden amongst the poor and outcast of Venice."

"We could bring them here, milord."

The duke hesitated, his head warring with his heart. But only for an instant, before the head began shaking firmly. Not for nothing did that head—that triangular, sharp-jawed face—resemble the animal he had been named after.

"No," he said firmly. "As you said yourself, Antimo, I have a responsibility to all of my offspring. Those of position as well as those of blood." For a moment, he paused in his pacing; stood very erect. "Dell'este honor has always been as famous as its cunning. Without the one, the other is meaningless."

Bartelozzi nodded. In obeisance as much as in agreement. He shared, in full measure, that loyalty for which the retainers of Dell'este were also famous.

"Valdosta cannot serve, for the moment." The Old Fox resumed his pacing. "Of the others . . . Brunelli is foul, as you well know, however cleverly that house has managed to disguise it. Dorma has potential, but the head of the house is still too young, unsure of himself."

"Petro Dorma may surprise you, milord."

The duke glanced at him. "You know something I don't?"

Bartelozzi shrugged. "Simply an estimate, nothing more."

Dell'este stared out the window which opened on to the little city of Ferrara. Looked past the city itself to the lush countryside beyond. "Perhaps, Antimo. I'm not sure I agree. Petro Dorma is a judicious man, true enough. And, I think, quite an honorable one. But that's not enough. A sword must have an edge also."

The duke sighed. "If only Montescue . . . There's the man with the right edge. And, for all his age, the tested blade to hold it."

Hearing Bartelozzi's little choke, the duke smiled wryly. "Don't tell me. He's still trying to have my grandsons assassinated."

"It seems so, milord. Apparently the same rumors have reached him as well."

The Old Fox turned his head and gazed squarely upon his most trusted agent and adviser. "Instruct me, Antimo. In this matter, I do not entirely trust myself."

Bartelozzi hesitated. Then: "Do nothing, milord. Casa Montescue has fallen on such bad times that old Lodovico Montescue will not be able to afford better than middling murderers. And"—again, he hesitated—"we may as well discover now, at the beginning of the contest, how sharp a blade your grandsons will make."

The Duke of Ferrara pondered the advice, for a moment. Then, nodded. "Spoken like a Dell'este. See to it then, Antimo. Pass the word in Venice—very quietly—that if either of my grandsons come to the surface, we will pay well for whoever takes them under his wing. Until then . . . they will have to survive on their own. Blades, as you say, must be tempered."

His lips tightened, became a thin line. Those of a craftsman, gauging his material. "No doubt iron would scream also, if it could feel the pain of the forge and the hammer and the quenching tank. No matter. So is steel made."