STEPHEN

KING

THE

DARK TOWER II

THE

DRAWING

OF THE THREE

Illustrated

by Phil Hale

PLUME

Published by the

Penguin Group

Penguin Putnam

Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books

Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England

Penguin Books

Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books

Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue,

Toronto,

Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books

(N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

Penguin Books

Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

Published by

Plume, an imprint of Dutton Signet,

a member of

Penguin Putnam Inc.

Originally

published in a limited edition by Donald M. Grant, Publisher, Inc.,

West Kingston,

Rhode Island.

First Plume

Printing, March, 1989

5 7

9 11 13 12 10

8 6

Copyright ©

Stephen King, 1987

Illustrations copyright

© Phil Hale, 1987

All rights

reserved

REGISTERED

TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA

LIBRARY OF

CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA:

King, Stephen.

The drawing of

the three.

(The Dark tower;

2)

I. Title. II.

Series: King, Stephen.

Dark tower; 2..

PS3561.I483D74 1989

813'.54 88-28018

ISBN

0-452-27961-5

Printed in the

United States of America

Without limiting

the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this

publication may be

reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or

transmitted, in

any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording, or

otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright

owner and the

above publisher of this book.

BOOKS ARE

AVAILABLE AT QUANTITY DISCOUNTS WHEN USED TO PROMOTE PRODUCTS

OR SERVICES. FOR

INFORMATION PLEASE WRITE TO PREMIUM MARKETING DIVISION,

PENGUIN PUTNAM

INC., 375 HUDSON STREET, NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10014.

To

Don Grant, who's taken a chance on these novels, one by one.

CONTENTS

ARGUMENT

prologue: the sailor

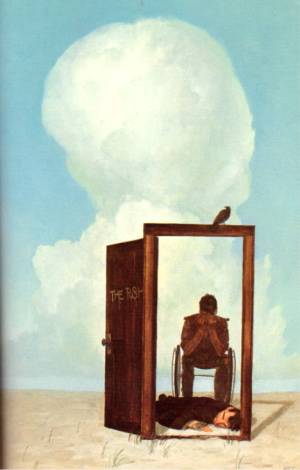

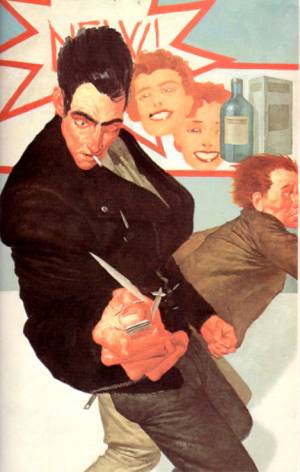

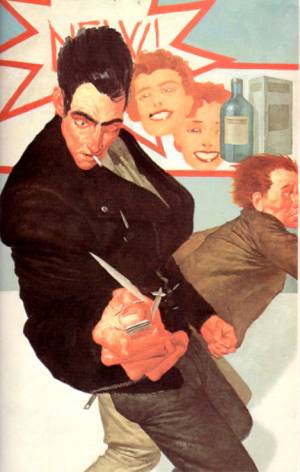

THE

PRISONER

1

• THE DOOR

2

• EDDIE DEAN

3

• CONTACT AND LANDING

4

• THE TOWER

5

• SHOWDOWN AND SHOOT-OUT

SHUFFLE

THE

LADY OF SHADOWS

1

• DETTA AND ODETTA

2

• RINGING THE CHANGES

3

• ODETTA ON THE OTHER SIDE

4

• DETTA ON THE OTHER SIDE

RESHUFFLE

THE

PUSHER

1

• BITTER MEDICINE

2

• THE HONEYPOT

3

• ROLAND TAKES HIS MEDICINE

4

• THE DRAWING

FINAL

SHUFFLE

AFTERWORD

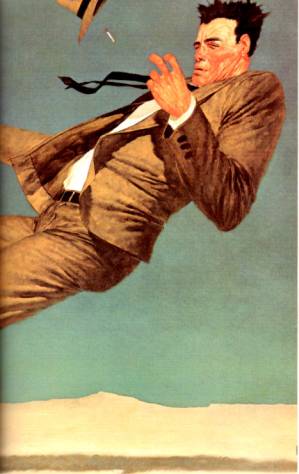

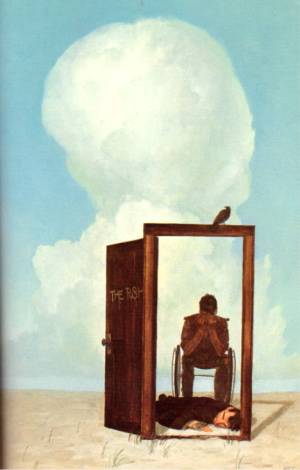

ILLUSTRATIONS

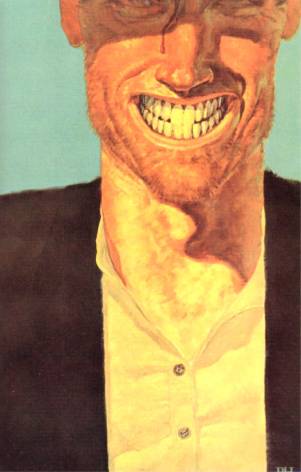

DID-A-CHICK

ROLAND

ON

THE BEACH

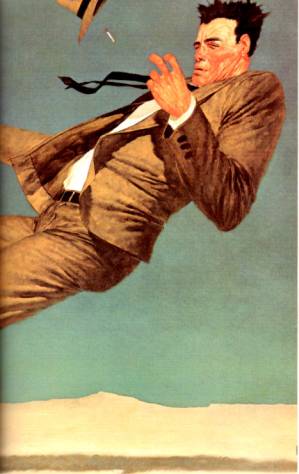

SOUVENIR

WAITING

FOR ROLAND

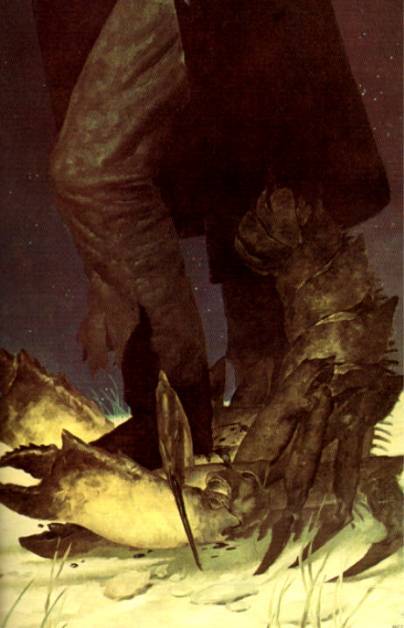

DETTA

WAITNG

FOR THE PUSHER

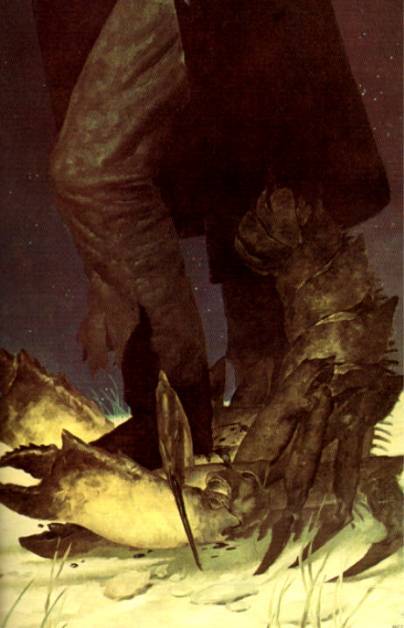

NOTHING

BUT THE HILT

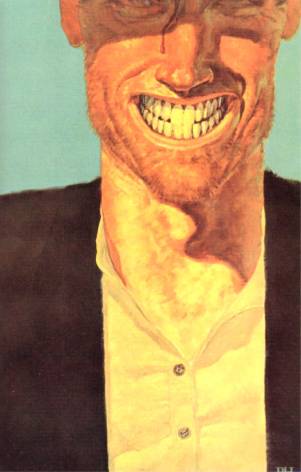

JACK

MORT

THE

GUNSLINGER

ARGUMENT

The Drawing of the

Three is the second volume of a long tale called The

Dark Tower, a tale inspired by and to some degree dependent upon Robert

Browning's narrative poem "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came"

(which in its turn owes a debt to King Lear).

The first volume, The

Gunslinger, tells how Roland, the last gunslinger of a world which has

"moved on," finally catches up with the man in black ... a sorcerer

he has chased for a very long time—just how long we do not yet know. The

man in black turns out to be a fellow named Walter, who falsely claimed the

friendship of Roland's father in those days before the world moved on.

Roland's goal is not

this half-human creature but the Dark Tower; the man in black—and, more

specifically, what the man in black knows—is his first step on his road to

that mysterious place.

Who, exactly, is

Roland? What was his world like before it "moved on?" What is the

Tower, and why does he pursue it? We have only fragmentary answers. Roland is a

gunslinger, a kind of knight, one of those charged with holding a world Roland

remembers as being "filled with love and light" as it is; to keep it

from moving on.

We know that Roland

was forced to an early trial of manhood after discovering that his mother had

become the mistress of Marten, a much greater sorcerer than Walter (who,

unknown to Roland's father, is Marten's ally); we know Marten has planned

Roland's discovery, expecting Roland to fail and to be "sent West";

we know that Roland triumphs in his test.

What else do we know? That the gunslinger's

world is not completely unlike our own. Artifacts such as gasoline pumps and

certain songs ("Hey Jude," for instance, or the bit of doggerel that

begins "Beans, beans, the musical fruit . . .") have survived; so

have customs and rituals oddly like those from our own romanticized view of the

American west.

And there is an umbilicus which somehow connects

our world to the world of the gunslinger. At a way-station on a long-deserted

coach-road in a great and sterile desert, Roland meets a boy named Jake who died

in our world. A boy who was, in fact, pushed from a street-corner by the

ubiquitous (and iniquitous) man in black. The last thing Jake, who was on his

way to school with his book-bag in one hand and his • lunch-box in the other,

remembers of his world—our world— I is being crushed beneath the wheels

of a Cadillac . . . and dying.

Before reaching the man in black, Jake dies

again. . . this time because the gunslinger, faced with the second-most agonizing

choice of his life, elects to sacrifice this symbolic son. Given a choice

between the Tower and child, possibly between damnation and salvation, Roland

chooses the Tower.

"Go, then," Jake tells him before

plunging into the abyss. "There are other worlds than these."

The final confrontation between Roland and Walter

occurs in a dusty golgotha of decaying bones. The dark man tells Roland's

future with a deck of Tarot cards. These cards, showing a man called The

Prisoner, a woman called The Lady of Shadows, and a darker shape that is simply

Death ("but not for you, gunslinger," the man in black tells him),

are prophecies which become the subject of this volume. . . and Roland's

second step on the long and difficult path to the Dark Tower.

The Gunslinger end?, with Roland sitting upon

the beach of the Western Sea, watching the sunset. The man in black is dead,

the gunslinger's own future course unclear; The Drawing of the Three begins

on that same beach, less than seven hours later.

-PROLOGUE:

THE

SAILOR

PROLOGUE

The gunslinger came awake from a confused dream

which seemed to consist of a single image: that of the Sailor in the Tarot deck

from which the man in black had dealt (or purported to deal) the gunslinger's

own moaning future.

He drowns, gunslinger, the man in black was

saying, and no one throws out the line. The boy Jake.

But this was no nightmare. It was a good dream.

It was good because he was the one drowning, and that meant he was not

Roland at all but Jake, and he found this a relief because it would be far

better to drown as Jake than to live as himself, a man who had, for a cold

dream, betrayed a child who had trusted him.

Good, all right, I'll drown, he thought, listening to

the roar of the sea. Let me drown. But this was not the sound of the

open deeps; it was the grating sound of water with a throatful of stones. Was

he the Sailor? If so, why was land so close? And, in fact, was he not on

the land? It felt as if—

Freezing cold water doused his boots and ran up

his legs to his crotch. His eyes flew open then, and what snapped him out of

the dream wasn't his freezing balls, which had suddenly shrunk to what felt

like the size of walnuts, nor even the horror to his right, but the thought of

his guns. . . his guns, and even more important, his shells. Wet guns could be

quickly disassembled, wiped dry, oiled, wiped dry again, oiled again, and

re-assembled; wet shells, like wet matches, might or might not ever be usable

again.

The horror was a crawling thing which must have

been cast up by a previous wave. It dragged a wet, gleaming body laboriously

along the sand. It was about four feet long and about four yards to the right.

It regarded Roland with bleak eyes on stalks. Its long serrated beak dropped

open and it began to make a noise that was weirdly like human speech:

plaintive, even desperate questions in an alien tongue. "Did-a-chick?

Dum-a-chum? Dad-a-cham? Ded-a-check?"

The gunslinger had seen lobsters. This wasn't

one, although lobsters were the only things he had ever seen which this creature

even vaguely resembled. It didn't seem afraid of him at all. The gunslinger

didn't know if it was dangerous or not. He didn't care about his own mental

confusion—his temporary inability to remember where he was or how he had gotten

there, if he had actually caught the man in black or if all that had only been

a dream. He only knew he had to get away from the water before it could drown

his shells.

He heard the grinding, swelling roar of water

and looked from the creature (it had stopped and was holding up the claws with

which it had been pulling itself along, looking absurdly like a boxer assuming

his opening stance, which, Cort had taught them, was called The Honor Stance)

to the incoming breaker with its curdle of foam.

It hears the wave, the gunslinger thought. Whatever

it is, it's got ears. He tried to get up, but his legs, too numb to feel,

buckled under him.

I'm still dreaming, he thought, but even in

his current confused state this was a belief much too tempting to really be

believed. He tried to get up again, almost made it, then fell back. The wave

was breaking. There was no time again. He had to settle for moving in much the

same way the creature on his right seemed to move: he dug in with both hands

and dragged his butt up the stony shingle, away from the wave.

He didn't progress enough to avoid the wave

entirely, but he got far enough for his purposes. The wave buried nothing but

his boots. It reached almost to his knees and then retreated. Perhaps the

first one didn't go as far as I thought. Perhaps—

There was a half-moon in the sky. A caul of mist

covered it, but it shed enough light for him to see that the holsters were too

dark. The guns, at least, had suffered a wetting. It was impossible to tell how

bad it had been, or if either the shells currently in the cylinders or those in

the crossed gunbelts had also been wetted. Before checking, he had

to get away from the water. Had to—

"Dod-a-chock?"

This was much closer. In his worry over the water he had

forgotten the creature the water had cast up. He looked around and saw it was

now only four feet away. Its claws were buried in the stone- and shell-littered

sand of the shingle, pulling its body along. It lifted its meaty, serrated

body, making it momentarily resemble a scorpion, but Roland could see no

stinger at the end of its body.

Another grinding roar,

this one much louder. The creature immediately stopped and raised its claws

into its own peculiar version of the Honor Stance again.

This wave was bigger.

Roland began to drag himself up the slope of the strand again, and when he put

out his hands, the clawed creature moved with a speed of which its previous

movements had not even hinted.

The gunslinger felt a

bright flare of pain in his right hand, but there was no time to think about

that now. He pushed with the heels of his soggy boots, clawed with his hands,

and managed to get away from the wave.

"Did-a-chick?"

the monstrosity enquired in its plaintive Won't you help

me? Can't you see I am desperate? voice, and Roland saw the stumps of the

first and second fingers of his right hand disappearing into the creature's

jagged beak. It lunged again and Roland lifted his dripping right hand just in

time to save his remaining two fingers.

"Dum-a-chum? Dad-a-cham?"

The gunslinger

staggered to his feet. The thing tore open his dripping jeans, tore through a

boot whose old leather was soft but as tough as iron, and took a chunk of meat

from Roland's lower calf.

He drew with his right

hand, and realized two of the fingers needed to perform this ancient killing

operation were gone only when the revolver thumped to the sand.

The monstrosity

snapped at it greedily.

"No,

bastard!" Roland snarled, and kicked it. It was like kicking a block of

rock. . . one that bit. It tore away the end of Roland's right boot, tore away

most of his great toe, tore the boot itself from his foot.

The gunslinger bent,

picked up his revolver, dropped it, cursed, and finally managed. What had once

been a thing so easy it didn't even bear thinking about had suddenly become a

trick akin to juggling.

The creature was

crouched on the gunslinger's boot, tearing at it as it asked its garbled

questions. A wave rolled toward the beach, the foam which curdled its top

looking pallid and dead in the netted light of the half-moon. The lobstrosity

stopped working on the boot and raised its claws in that boxer's pose.

Roland drew with his

left hand and pulled the trigger three times. Click, click, click.

Now he knew about the

shells in the chambers, at least.

He bolstered the left

gun. To holster the right he had to turn its barrel downward with his left hand

and then let it drop into its place. Blood slimed the worn ironwood handgrips;

blood spotted the holster and the old jeans to which the holster was

thong-tied. It poured from the stumps where his fingers used to be.

His mangled right foot

was still too numb to hurt, but his right hand was a bellowing fire. The ghosts

of talented and long-trained fingers which were already decomposing in the

digestive juices of that thing's guts screamed that they were still there, that

they were burning.

I

see serious problems ahead, the gunslinger thought remotely.

The wave retreated.

The monstrosity lowered its claws, tore a fresh hole in the gunslinger's boot,

and then decided the wearer had been a good deal more tasty than this bit of

skin it had somehow sloughed off.

"Dud-a-chum?"

it asked, and scurried toward him with ghastly speed. The

gunslinger retreated on legs he could barely feel, realizing that the creature

must have some intelligence; it had approached him cautiously, perhaps from a

long way down the strand, not sure what he was or of what he might be capable.

If the dousing wave hadn't wakened him, the thing would have torn off his face

while he was still deep in his dream. Now it had decided he was not only tasty

but vulnerable; easy prey.

It was almost upon

him, a thing four feet long and a foot high, a creature which might weigh as

much as seventy pounds and which was as single-mindedly carnivorous as David,

the hawk he had had as a boy—but without David's dim vestige of loyalty.

The gunslinger's left

bootheel struck a rock jutting from the sand and he tottered on the edge of

falling.

"Dod-a-chock?"

the thing asked, solicitously it seemed, and peered at the

gunslinger from its stalky, waving eyes as its claws reached . . . and then a

wave came, and the claws went up again in the Honor Stance. Yet now they

wavered the slightest bit, and the gunslinger realized that it responded to the

sound of the wave, and now the sound was—for it, at least—fading a bit.

He stepped backward

over the rock, then bent down as the wave broke upon the shingle with its

grinding roar. His head was inches from the insectile face of the creature. One

of its claws might easily have slashed the eyes from his face, but its

trembling claws, so like clenched fists, remained raised to either side of its

parrotlike beak.

The gunslinger reached

for the stone over which he had nearly fallen. It was large, half-buried in the

sand, and his mutilated right hand howled as bits of dirt and sharp edges of

pebble ground into the open bleeding flesh, but he yanked the rock free and

raised it, his lips pulled away from his teeth.

"Dad-a—" the

monstrosity began, its claws lowering and opening as the wave broke and its

sound receded, and the gunslinger swept the rock down upon it with all his

strength.

There was a crunching

noise as the creature's segmented back broke. It lashed wildly beneath the

rock, its rear half lifting and thudding, lifting and thudding. Its

interrogatives became buzzing exclamations of pain. Its claws opened and shut

upon nothing. Its maw of a beak gnashed up clots of sand and pebbles.

And yet, as another

wave broke, it tried to raise its claws again, and when it did the gunslinger

stepped on its head with his remaining boot. There was a sound like many small

dry twigs being broken. Thick fluid burst from beneath the heel of Roland's

boot, splashing in two directions. It looked black.

The thing arched and

wriggled in a frenzy. The gunslinger planted his boot harder.

A wave came.

The monstrosity's

claws rose an inch . . . two inches . . . trembled and then fell, twitching

open and shut.

The gunslinger removed

his boot. The thing's serrated beak, which had separated two fingers and one

toe from his living body, slowly opened and closed. One antenna lay broken on

the sand. The other trembled meaninglessly.

The gunslinger stamped

down again. And again.

He kicked the rock

aside with a grunt of effort and marched along the right side of the

monstrosity's body, stamping methodically with his left boot, smashing its

shell, squeezing its pale guts out onto dark gray sand. It was dead, but he

meant to have his way with it all the same; he had never, in all his long

strange time, been so fundamentally hurt, and it had all been so unexpected.

He kept on until he

saw the tip of one of his own fingers in the dead thing's sour mash, saw the

white dust beneath the nail from the golgotha where he and the man in black had

held their long palaver, and then he looked aside and vomited.

The gunslinger walked

back toward the water like a drunken man, holding his wounded hand against his

shirt, looking back from time to time to make sure the thing wasn't still

alive, like some tenacious wasp you swat again and again and still twitches, stunned

but not dead; to make sure it wasn't following, asking its alien questions in

its deadly despairing voice.

Halfway down the

shingle he stood swaying, looking at the place where he had been, remembering.

He had fallen asleep, apparently, just below the high tide line. He grabbed his

purse and his torn boot.

In the moon's glabrous

light he saw other creatures of the same type, and in the caesura between one

wave and the next, heard their questioning voices.

The gunslinger

retreated a step at a time, retreated until he reached the grassy edge of the

shingle. There he sat down, and did all he knew to do: he sprinkled the stumps

of fingers and toe with the last of his tobacco to stop the bleeding, sprinkled

it thick in spite of the new stinging (his missing great toe had joined the

chorus), and then he only sat, sweating in the chill, wondering about

infection, wondering how he would make his way in this world with two fingers

on his right hand gone (when it came to the guns both hands had been equal, but

in all other things his right had ruled), wondering if the thing had some

poison in its bite which might already be working its way into him, wondering

if morning would ever come.

CHAPTER

1

THE

DOOR

1

Three. This is the number of your fate.

Three?

Yes, three is mystic. Three stands at the heart

of the mantra.

Which three?

The first is dark-haired. He stands on the brink

of robbery and murder. A demon has infested him. The name of the demon is

HEROIN.

Which demon is that? I

know it not, even from nursery stories.

He tried to speak but his voice was gone, the

voice of the oracle, Star-Slut, Whore of the Winds, both were gone; he saw a

card fluttering down from nowhere to now here, turning and turning in the lazy

dark. On it a baboon grinned from over the shoulder of a young man with dark

hair; its disturbingly human fingers were buried so deeply in the young man's

neck that their tips had disappeared in flesh. Looking more closely, the

gunslinger saw the baboon held a whip in one of those clutching, strangling

hands. The face of the ridden man seemed to writhe in wordless terror.

The Prisoner, the

man in black (who had once been a man the gunslinger trusted, a man named

Walter) whispered chummily. A trifle upsetting, isn't he? A trifle upsetting

... a trifle upsetting ... a trifle—

2

The gunslinger snapped

awake, waving at something with his mutilated hand, sure that in a moment one

of the monstrous shelled things from the Western Sea would drop on him,

desperately enquiring in its foreign tongue as it pulled his face off his

skull.

Instead a sea-bird,

attracted by the glister of the morning sun on the buttons of his shirt,

wheeled away with a frightened squawk.

Roland sat up.

His hand throbbed

wretchedly, endlessly. His right foot did the same. Both fingers and toe

continued to insist they were there. The bottom half of his shirt was gone;

what was left resembled a ragged vest. He had used one piece to bind his hand,

the other to bind his foot.

Go away, he

told the absent parts of his body. You are ghosts now. Go away.

It helped a little.

Not much, but a little. They were ghosts, all right, but lively ghosts.

The gunslinger ate

jerky. His mouth wanted it little, his stomach less, but he insisted. When it

was inside him, he felt a little stronger. There was not much left, though; he

was nearly up against it.

Yet things needed to

be done.

He rose unsteadily to

his feet and looked about. Birds swooped and dived, but the world seemed to

belong to only him and them. The monstrosities were gone. Perhaps they were

nocturnal; perhaps tidal. At the moment it seemed to make no difference.

The sea was enormous,

meeting the horizon at a misty blue point that was impossible to determine. For

a long moment the gunslinger forgot his agony in its contemplation. He had

never seen such a body of water. Had heard of it in children's stories, of

course, had even been assured by his teachers—some, at least—that it

existed—but to actually see it, this immensity, this amazement of water after

years of arid land, was difficult to accept. . . difficult to even see.

He looked at it for a

long time, enrapt, making himself see it, temporarily forgetting his

pain in wonder.

But it was morning,

and there were still things to be done.

He felt for the

jawbone in his back pocket, careful to lead with the palm of his right hand,

not wanting the stubs of his fingers to encounter it if it was still there,

changing that hand's ceaseless sobbing to screams.

It was.

All right.

Next.

He clumsily unbuckled

his gunbelts and laid them on a sunny rock. He removed the guns, swung the

chambers out, and removed the useless shells. He threw them away. A bird

settled on the bright gleam tossed back by one of them, picked it up in its

beak, then dropped it and flew away.

The guns themselves

must be tended to, should have been tended to before this, but since no gun in

this world or any other was more than a club without ammunition, he laid the

gunbelts themselves over his lap before doing anything else and carefully ran

his left hand over the leather.

Each of them was damp

from buckle and clasp to the point where the belts would cross his hips; from

that point they seemed dry. He carefully removed each shell from the dry

portions of the belts. His right hand kept trying to do this job, insisted on

forgetting its reduction in spite of the pain, and he found himself returning

it to his knee again and again, like a dog too stupid or fractious to heel. In

his distracted pain he came close to swatting it once or twice.

I see serious problems

ahead, he thought again.

He put these shells,

hopefully still good, in a pile that was dishearteningly small. Twenty. Of

those, a few would almost certainly misfire. He could depend on none of them.

He removed the rest and put them in another pile. Thirty-seven.

Well, you weren't

heavy loaded, anyway, he thought, but he recognized the

difference between fifty-seven live rounds and what might be twenty. Or ten. Or

five. Or one. Or none.

He put the dubious

shells in a second pile.

He still had his

purse. That was one thing. He put it in his lap and then slowly disassembled

his guns and performed the ritual of cleaning. By the time he was finished, two

hours had passed and his pain was so intense his head reeled with it; conscious

thought had become difficult. He wanted to sleep. He had never wanted that more

in his life/But in the service of duty there was never

any acceptable reason for denial.

"Cort," he

said in a voice that he couldn't recognize, and laughed dryly.

Slowly, slowly, he

reassembled his revolvers and loaded them with the shells he presumed to be

dry. When the job was done, he held the one made for his left hand, cocked

it... and then slowly lowered the hammer again. He wanted to know, yes. Wanted

to know if there would be a satisfying report when he squeezed the trigger or

only another of those useless clicks. But a click would mean nothing, and a

report would only reduce twenty to nineteen... or nine... or three... or none.

He tore away another

piece of his shirt, put the other shells—the ones which had been wetted—in it,

and tied it, using his left hand and his teeth. He put them in his purse.

Sleep, his

body demanded. Sleep, you must sleep, now, before dark, there's nothing

left, you're used up—

He tottered to his

feet and looked up and down the deserted strand. It was the color of an

undergarment which has gone a long time without washing, littered with

sea-shells which had no color. Here and there large rocks protruded from the

gross-grained sand, and these were covered with guano, the older layers the

yellow of ancient teeth, the fresher splotches white.

The high-tide line was

marked with drying kelp. He could see pieces of his right boot and his

waterskins lying near that line. He thought it almost a miracle that the skins

hadn't been washed out to sea by high-surging waves. Walking slowly, limping

exquisitely, the gunslinger made his way to where they were. He picked up one

of them and shook it by his ear. The other was empty. This one still had a

little water left in it. Most would not have been able to tell the difference

between the two, but the gunslinger knew each just as well as a mother knows

which of her identical twins is which. He had been travelling with these

waterskins for a long, long time. Water sloshed inside. That was good—a gift.

Either the creature which had attacked him or any of the others could have

torn this or the other open with one casual bite or slice of claw, but none had

and the tide had spared it. Of the creature itself there was no sign, although

the two of them had finished far above the tide-line. Perhaps other predators

had taken it; perhaps its own kind had given it a burial at sea, as the elaphaunts,

giant creatures of whom he had heard in childhood stories, were reputed to

bury their own dead.

He lifted the

waterskin with his left elbow, drank deeply, and felt some strength come back

into him. The right boot was of course ruined. . . but then he felt a spark of

hope. The foot itself was intact—scarred but intact—and it might be possible to

cut the other down to match it, to make something which would last at least

awhile. . . .

Faintness stole over

him. He fought it but his knees unhinged and he sat down, stupidly biting his

tongue.

You won't fall

unconscious, he told himself grimly. Not here, not where

another of those things can come back tonight and finish the job.

So he got to his feet

and tied the empty skin about his waist, but he had only gone twenty yards back

toward the place where he had left his guns and purse when he fell down again,

half-fainting. He lay there awhile, one cheek pressed against the sand, the

edge of a seashell biting against the edge of his jaw almost deep enough to

draw blood. He managed to drink from the waterskin, and then he crawled back to

the place where he had awakened. There was a Joshua tree twenty yards up the

slope—it was stunted, but it would offer at least some shade.

To Roland the twenty

yards looked like twenty miles.

Nonetheless, he

laboriously pushed what remained of his possessions into that little puddle of

shade. He lay there with his head in the grass, already fading toward what

could be sleep or unconsciousness or death. He looked into the sky and tried to

judge the time. Not noon, but the size of the puddle of shade in which he

rested said noon was close. He held on a moment longer, turning his right arm

over and bringing it close to his eyes, looking for the telltale red lines of

infection, of some poison seeping steadily toward the middle of him.

The palm of his hand

was a dull red. Not a good sign.

I

jerk off left-handed, he thought, at least that's something.

Then darkness took

him, and he slept for the next sixteen hours with the sound of I he Western Sea

pounding ceaselessly in his dreaming ears.

3

When the gunslinger

awoke again the sea was dark but there was faint light in the sky to the east.

Morning was on its way. He sat up and waves of dizziness almost overcame him.

He bent his head and

waited.

When the faintness had

passed, he looked at his hand. It was infected, all right—a tell-tale red

swelling that spread up the palm and to the wrist. It stopped there, but

already he could see the faint beginnings of other red lines, which would lead

eventually to his heart and kill him. He felt hot, feverish.

I need medicine, he

thought. But there is no medicine here.

Had he come this far

just to die, then? He would not. And if he were to die in spite of his

determination, he would die on his way to the Tower.

How remarkable you

are, gunslinger! the man in black tittered inside his

head. How indomitable! How romantic in your stupid obsession!

"Fuck you,'' he

croaked, and drank. Not much water left, either. There was a whole sea in front

of him, for all the good it could do him; water, water everywhere, but not a

drop to drink. Never mind.

He buckled on his

gunbelts, tied them—this was a process which took so long that before he was

done the first faint light of dawn had brightened to the day's actual

prologue—and then tried to stand up. He was not convinced he could do it until

it was done.

Holding to the Joshua

tree with his left hand, he scooped up the not-quite-empty waterskin with his

right arm and slung it over his shoulder.

Then his purse. When he

straightened the faintness washed over him again and he put his head down,

waiting, willing.

The faintness passed.

Walking with the

weaving, wavering steps of a man in the last stages of ambulatory drunkenness,

the gunslinger made his way back down to the strand. He stood, looking at an

ocean as dark as mulberry wine, and then took the last of his jerky from his

purse. He ate half, and this time both mouth and stomach accepted a little more

willingly. He turned and ate the other half as he watched the sun come up over

the mountains where Jake had died—first seeming to catch on the cruel and

treeless teeth of those peaks, then rising above them.

Roland held his face

to the sun, closed his eyes, and smiled. He ate the rest of his jerky.

He thought: Very

well. I am now a man with no food, with two less fingers and one less toe than

I was born with; I am a gunslinger with shells which may not fire; I am sickening

from a monster's bite and have no medicine; I have a day's water if I'm lucky;

I may be able to walk perhaps a dozen miles if I press myself to the last

extremity. I am, in short, a man on the edge of everything.

Which way should he

walk? He had come from the east; he could not walk west without the powers of a

saint or a savior. That left north and south.

North.

That was the answer

his heart told. There was no question in it.

North.

The gunslinger began

to walk.

4

He walked for three

hours. He fell twice, and the second time he did not believe he would be able

to get up again. Then a wave came toward him, close enough to make him remember

his guns, and he was up before he knew it, standing on legs that quivered like

stilts.

He thought he had

managed about four miles in those three hours. Now the sun was growing hot, but

not hot enough to explain the way his head pounded or the sweat pouring down

his face; nor was the breeze from the sea strong enough to explain the sudden

fits of shuddering which sometimes gripped him, making his body lump into

gooseflesh and his teeth chatter.

Fever, gunslinger, the

man in black tittered. What's left inside you has been touched afire.

The red lines of inlet

lion were more pronounced now; they had marched upward from his right wrist

halfway to his elbow.

He made another mile

and drained his waterbag dry. He tied it around his waist with the other. The

landscape was monotonous and unpleasing. The sea to his right, the mountains

to his left, the gray, shell-littered sand under the feet of his cut-down

boots. The waves came and went. He looked for the lobstrosities and saw none.

He walked out of nowhere toward nowhere, a man from another time who, it

seemed, had reached a point of pointless ending.

Shortly before noon he

fell again and knew he could not get up. This was the place, then. Here. This

was the end, after all.

On his hands and

knees, he raised his head like a groggy fighter . . . and some distance ahead,

perhaps a mile, perhaps three (it was difficult to judge distances along the

unchanging reach of the strand with the fever working inside him, making his

eyeballs pulse in and out), he saw something new. Something which stood

upright on the beach.

What was it?

(three)

Didn't matter.

(three is the number

of your fate)

The gunslinger managed

to get to his feet again. He croaked something, some plea which only the

circling sea-birds heard (and how happy they would be to gobble my eyes from

my head, he thought, how happy to have such a tasty bit!), and

walked on, weaving more seriously now, leaving tracks behind him that were

weird loops and swoops.

He kept his eyes on

whatever it was that stood on the strand ahead. When his hair fell in his eyes

he brushed it aside. It seemed to grow no closer. The sun reached the roof of

the sky, where it seemed to remain far too long. Roland imagined he was in the

desert again, somewhere between the last out-lander's hut

(the musical fruit the

more you eat the more you toot)

and the way-station

where the boy

(your Isaac)

had awaited his

coming.

His knees buckled,

straightened, buckled, straightened again. When his hair fell in his eyes once

more he did not bother to push it back; did not have the strength to push it

back. He looked at the object, which now cast a narrow shadow back toward the upland,

and kept walking.

He could make it out

now, fever or no fever.

It was a door.

Less than a quarter of

a mile from it, Roland's knees buckled again and this time he could not stiffen

their hinges. He fell, his right hand dragged across gritty sand and shells,

the stumps of his fingers screamed as fresh scabs were scored away. The stumps

began to bleed again.

So he crawled. Crawled

with the steady rush, roar, and retreat of the Western Sea in his ears. He used

his elbows and his knees, digging grooves in the sand above the twist of dirty

green kelp which marked the high-tide line. He supposed the wind was still

blowing—it must be, for the chills continued to whip through his body—but the

only wind he could hear was the harsh gale which gusted in and out of his own

lungs.

The door grew closer.

Closer.

At last, around three

o'clock of that long delirious day, with his shadow beginning to grow long on

his left, he reached it. He sat back on his haunches and regarded it wearily.

It stood six and a

half feet high and appeared to be made of solid ironwood, although the nearest

ironwood tree must grow seven hundred miles or more from here. The doorknob

looked as if it were made of gold, and it was filigreed with a design which the

gunslinger finally recognized: it was the grinning face of the baboon.

There was no keyhole

in the knob, above it, or below it.

The door had hinges,

but they were fastened to nothing— or so it seems, the gunslinger

thought. This is a mystery, a most marvellous mystery, but does it really matter?

You are dying. Your own mystery—the only one that really matters to any man or

woman in the end—approaches.

All the same, it did

seem to matter.

This door. This door

where no door should be. It simply stood there on the gray strand twenty feet

above the high tide line, seemingly as eternal as the sea itself, now casting

the slanted shadow of its thickness toward the east as the sun westered.

Written upon it in

black letters two-thirds of the way up, written in the high speech, were two

words:

THE

PRISONER

A demon has infested

him. The name of the demon is HEROIN.

The gunslinger could

hear a low droning noise. At first he thought it must be the wind or a sound in

his own feverish head, but he became more and more convinced that the sound was

the sound of motors . . . and that it was coming from behind the door.

Open it then. It's not

locked. You know it's not locked.

Instead he tottered

gracelessly to his feet and walked above the door and around to the other side.

There was no

other side.

Only the dark gray

strand, stretching back and back. Only the waves, the shells, the high-tide

line, the marks of his own approach—bootprints and holes that had been made by

his elbows. He looked again and his eyes widened a little. The door wasn't

here, but its shadow was.

He started to put out

his right hand—oh, it was so slow learning its new place in what was left of

his life—dropped it, and raised his left instead. He groped, feeling for hard

resistance.

If I feel it I'll

knock on nothing, the gunslinger thought. That would be

an interesting thing to do before dying!

His hand encountered

thin air far past the place where the door—even if invisible—should have been.

Nothing to knock on.

And the sound of

motors—if that's what it really had been—was gone. Now there was just the wind,

the waves, and the sick buzzing inside his head.

The gunslinger walked

slowly back to the other side of what wasn't there, already thinking it had

been a hallucination to start with, a—

He stopped.

At one moment he had

been looking west at an uninterrupted view of a gray, rolling wave, and then

his view was interrupted by the thickness of the door. He could see its

keyplate, which also looked like gold, with the latch protruding from it like

a stubby metal tongue. Roland moved his head an inch to the north and the door

was gone. Moved it back to where it had been and it was there again. It did not

appear; it was just there.

He walked all the way

around and faced the door, swaying.

He could walk around

on the sea side, but he was convinced that the same thing would happen, only

this time he would fall down.

I wonder if I could go

through it from the nothing side?

Oh, there were all

sorts of things to wonder about, but the truth was simple: here stood this door

alone on an endless stretch of beach, and it was for only one of two things:

opening or leaving closed.

The gunslinger

realized with dim humor that maybe he wasn't dying quite as fast as he thought.

If he had been, would he feel this scared?

He reached out and

grasped the doorknob with his left hand. Neither the deadly cold of the metal

or the thin, fiery heat of the runes engraved upon it surprised him.

He turned the knob.

The door opened toward him when he pulled.

Of all the things he

might have expected, this was not any of them.

The gunslinger looked,

froze, uttered the first scream of terror in his adult life, and slammed the

door. There was nothing for it to bang shut on, but it banged shut just the

same, sending seabirds screeching up from the rocks on which they had perched

to watch him.

5

What he had seen was

the earth from some high, impossible distance in the sky—miles up, it seemed.

He had seen the shadows of clouds lying upon that earth, floating across it

like dreams. He had seen what an eagle might see if one could fly thrice

as high as any eagle could.

To step through such a

door would be to fall, screaming, for what might be minutes, and to end by

driving one's self deep into the earth.

No, you saw more.

He considered it as he

sat stupidly on the sand in front of the closed door with his wounded hand in

his lap. The first faint traceries had appeared above his elbow now. The infection

would reach his heart soon enough, no doubt about that.

It was the voice of

Cort in his head.

Listen to me, maggots.

Listen for your lives, for that's what it could mean some day. You never see

all that you see. One of the things they send you to me for is to show you what

you don't see in what you see—what you don't see when you're scared, or

fighting, or running, or fucking. No man sees all that he sees, but before

you're gunslingers—those of you who don't go west, that is—you'll see more in

one single glance than some men see in a lifetime. And some of what you don't

see in that glance you'll see afterwards, in the eye of your memory—if you live

long enough to remember, that is. Because the difference between seeing and not

seeing can be the difference between living and dying.

He had seen the earth

from this huge height (and it had somehow been more dizzying and distorting

than the vision of growth which had come upon him shortly before the end of his

time with the man in black, because what he had seen through the door had been

no vision), and what little remained of his attention had registered the fact

that the land he was seeing was neither desert nor sea but some green place of

incredible lushness with interstices of water that made him think it was a

swamp, but—

What little remained

of your attention, the voice of Cort mimicked savagely. You saw more!

Yes.

He had seen white.

White edges.

Bravo, Roland! Cort

cried in his mind, and Roland seemed to feel the swat of that hard, callused

hand. He winced.

He had been looking

through a window.

The gunslinger stood with

an effort, reached forward, felt cold and burning lines of thin heat against

his palm. He opened the door again.

6

The view he had

expected—that view of the earth from some horrendous, unimaginable height—was

gone. He was looking at words he didn't understand. He almost understood

them; it was as if the Great Letters had been twisted. . . .

Above the words was a

picture of a horseless vehicle, a motor-car of the sort which had supposedly

filled the world before it moved on. Suddenly he thought of the things Jake had

said when, at the way station, the gunslinger had hypnotized him.

This horseless vehicle

with a woman wearing a fur stole laughing beside it, could be whatever had run

Jake over in that strange other world.

This is

that other world, the gunslinger thought.

Suddenly the view . .

.

It did not change; it moved.

The gunslinger wavered on his feet, feeling vertigo and a touch of nausea.

The words and the picture descended and now he saw an aisle with a double row

of seats on the far side. A few were empty, but there were men in most of them,

men in strange dress. He supposed they were suits, but he had never seen any

like them before. The things around their necks could likewise be ties or

cravats, but he had seen none like these, either. And, so far as he could tell,

not one of them was armed—he saw no dagger nor sword, let alone a gun. What

kind of trusting sheep were these? Some read papers covered with tiny

words—words broken here and there with pictures—while others wrote on papers

with pens of a sort the gunslinger had never seen. But the pens mattered little

to him. It was the paper. He lived in a world where paper and gold were

valued in rough equivalency. He had never seen so much paper in his life. Even

now one of the men tore a sheet from the yellow pad which lay upon his lap and

crumpled it into a ball, although he had only written on the top half of one

side and not at all on the other. The gunslinger was not too sick to feel a

twinge of horror and outrage at such unnatural profligacy.

Beyond the men was a

curved white wall and a row of windows. A few of these were covered by some

sort of shutters, but he could see blue sky beyond others.

Now a woman approached

the doorway, a woman wearing what looked like a uniform, but of no sort Roland

had ever seen. It was bright red, and part of it was pants. He could see

the place where her legs became her crotch. This was nothing he had ever seen

on a woman who was not undressed.

She came so close to

the door that Roland thought she would walk through, and he blundered back a

step, lucky not to fall. She looked at him with the practiced solicitude of a

woman who is at once a servant and no one's mistress but her own. This did not

interest the gunslinger. What interested him was that her expression never

changed. It was not the way you expected a woman—anybody, for that matter—to

look at a dirty, swaying, exhausted man with revolvers crisscrossed on his

hips, a blood-soaked rag wrapped around his right hand, and jeans which looked

as if they'd been worked on with some kind of buzzsaw.

"Would you like.

. ." the woman in red asked. There was more, but the gunslinger didn't

understand exactly what it meant. Food or drink, he thought. That red cloth—it

was not cotton. Silk? It looked a little like silk, but—

"Gin," a

voice answered, and the gunslinger understood that. Suddenly he understood much

more:

It wasn't a door.

It was eyes.

Insane as it might

seem, he was looking at part of a carriage that flew through the sky. He was

looking through someone's eyes.

Whose?

But he knew. He was

looking through the eyes of the prisoner.

CHAPTER

2

EDDIE

DEAN

1

As if to confirm this

idea, mad as it was, what the gun-slinger was looking at through the doorway

suddenly rose and slid sidewards. The view turned (that feeling of

vertigo again, a feeling of standing still on a plate with wheels under it, a

plate which hands he could not see moved this way and that), and then the aisle

was flowing past the edges of the doorway. He passed a place where several women,

all dressed in the same red uniforms, stood. This was a place of steel things,

and he would have liked to make the moving view stop in spite of his pain and

exhaustion so he could see what the steel things were—machines of some sort.

One looked a bit like an oven. The army woman he had already seen was pouring

the gin which the voice had requested. The bottle she poured from was very

small. It was glass. The vessel she was pouring it into looked like

glass but the gunslinger didn't think it actually was.

What the doorway

showed had moved along before he could see more. There was another of those

dizzying turns and he was looking at a metal door. There was a lighted sign in

a small oblong. This word the gunslinger could read. VACANT, it said.

The view slid down a

little. A hand entered it from the right of the door the gunslinger was looking

through and grasped the knob of the door the gunslinger was looking at. He saw

the cuff of a blue shirt, slightly pulled back to reveal crisp curls of black

hair. Long fingers. A ring on one of them, with a jewel set into it that might

have been a ruby or a firedim or a piece of trumpery trash. The

gunslinger rather thought it this last—it was too big and vulgar to be real.

The metal door swung

open and the gunslinger was looking into the strangest privy he had ever seen.

It was all metal.

The edges of the metal

door flowed past the edges of the door on the beach. The gunslinger heard the

sound of it being closed and latched. He was spared another of those giddy

spins, so he supposed the man through whose eyes he was watching must have

reached behind himself to lock himself in.

Then the view did

turn—not all the way around but half—and he was looking into a mirror, seeing a

face he had seen once before... on a Tarot card. The same dark eyes and spill

of dark hair. The face was calm but pale, and in the eyes—eyes through which he

saw now reflected back at him— Roland saw some of the dread and horror of that

baboon-ridden creature on the Tarot card.

The man was shaking.

He's sick, too.

Then he remembered

Nort, the weed-eater in Tull.

He thought of the

Oracle.

A demon has infested

him.

The gunslinger

suddenly thought he might know what HEROIN was after all: something like the

devil-grass.

A trifle upsetting,

isn't he?

Without thought, with

the simple resolve that had made him the last of them all, the last to continue

marching on and on long after Cuthbert and the others had died or given up,

committed suicide or treachery or simply recanted the whole idea of the Tower;

with the single-minded and incurious resolve that had driven him across the

desert and all the years before the desert in the wake of the man in black, the

gunslinger stepped through the doorway.

2

Eddie ordered a gin

and tonic—maybe not such a good idea to be going into New York Customs drunk,

and he knew once he got started he would just keep on

going—but he had to have something.

When you got to get

down and you can't find the elevator, Henry had told him

once, you got to do it any way you can. Even if it's only with a shovel.

Then, after he'd given

his order and the stewardess had left, he started to feel like he was maybe

going to vomit. Not for sure going to vomit, only maybe, but it was

better to be safe. Going through Customs with a pound of pure cocaine under

each armpit with gin on your breath was not so good; going through Customs that

way with puke drying on your pants would be disaster. So better to be safe. The

feeling would probably pass, it usually did, but better to be safe.

Trouble was, he was

going cool turkey. Cool, not cold. More words of wisdom from that great

sage and eminent junkie Henry Dean.

They had been sitting

on the penthouse balcony of the Regency Tower, not quite on the nod but edging

toward it, the sun warm on their faces, done up so good. . . back in the good

old days, when Eddie had just started to snort the stuff and Henry himself had

yet to pick up his first needle.

Everybody talks about

going cold turkey, Henry had said, but before you get

there, you gotta go cool turkey.

And Eddie, stoned out

of his mind, had cackled madly, because he knew exactly what Henry was talking

about. Henry, however, had not so much as cracked a smile.

In some ways cool

turkey's worse than cold turkey, Henry said. At

least when you make it to cold turkey, you KNOW you're gonna puke, you KNOW

you're going to shake, you KNOW you're gonna sweat until it feels like you're

drowning in it. Cool turkey is, like, the curse of expectation.

Eddie remembered

asking Henry what you called it when a needle-freak (which, in those dim dead

days which must have been all of sixteen months ago, they had both solemnly

assured themselves they would never become) got a hot shot.

You call that baked

turkey, Henry had replied promptly, and then had looked surprised, the

way a person does when he's said something that turned out to be a lot funnier

than he actually thought it would be, and they looked at each other, and

then they were both howling with laughter and clutching each other. Baked

turkey, pretty funny, not so funny now.

Eddie walked up the

aisle past the galley to the head, checked the sign—VACANT—and opened the door.

Hey Henry, o great

sage if eminent junkie big brother, while we're on the subject of our feathered

friends, you want to hear my definition of cooked goose? That's when the

Customs guy at Kennedy decides there's something a little funny about the way

you look, or it's one of the days when they got the dogs with the PhD noses out

there instead of at Port Authority and they all start to bark and pee all over

the floor and it's you they're all just about strangling themselves on their

choke-chains trying to get to, and after the Customs guys toss all your luggage

they take you into the little room and ask you if you'd mind taking off your

shirt and you say yeah I sure would I'd mind like hell, I picked up a little

cold down in the Bahamas and the air-conditioning in here is real high and I'm

afraid it might turn into pneumonia and they say oh is that so, do you always

sweat like that when the air-conditioning's too high, Mr. Dean, you do, well,

excuse us all to hell, now do it, and you do it, and they say maybe you better

take off the t-shirt too, because you look like maybe you got some kind of a

medical problem, buddy, those bulges under your pits look like maybe they could

be some kind of lymphatic tumors or something, and you don't even bother to say

anything else, it's like a center-fielder who doesn't even bother to chase the

ball when it's hit a certain way, he just turns around and watches it go into the

upper deck, because when it's gone it's gone, so you take off the t-shirt and

hey, looky here, you're some lucky kid, those aren't tumors, unless they're

what you might call tumors on the corpus of society,

yuk-yuk-yuk, those things look more like a couple of baggies held there with

Scotch strapping tape, and by the way, don't worry about that smell, son,

that's just goose. It's cooked.

He reached behind him

and pulled the locking knob. The lights in the head brightened. The sound of

the motors was a soft drone. He turned toward the mirror, wanting to see how

bad he looked, and suddenly a terrible, pervasive feeling swept over him: a

feeling of being watched.

Hey, come on, quit it,

he thought uneasily. You're supposed to be the most

unparanoid guy in the world. That's why they sent you. That's why—

But it suddenly seemed

those were not his own eyes in the mirror, not Eddie Dean's hazel, almost-green

eyes that had melted so many hearts and allowed him to part so many pretty sets

of legs during the last third of his twenty-one years, not his eyes but those

of a stranger. Not hazel but a blue the color of fading Levis. Eyes that were

chilly, precise, unexpected marvels of calibration. Bombardier's eyes.

Reflected in them he

saw—clearly saw—a seagull swooping down over a breaking wave and snatching

something from it.

He had time to think What

in God's name is this shit? and then he knew it wasn't going to

pass; he was going to throw up after all.

In the half-second

before he did, in the half-second he went on looking into the mirror, he saw

those blue eyes disappear . . . but before that happened there was suddenly

the feeling of being two people ... of being possessed, like the little

girl in The Exorcist.

Clearly he felt a new

mind inside his own mind, and heard a thought not as his own thought but more

like a voice from a radio: I've come through. I'm in the sky-carriage.

There was something

else, but Eddie didn't hear it. He was too busy throwing up into the basin as

quietly as he could.

When he was done,

before he had even wiped his mouth, something happened which had never happened

to him before. For one frightening moment there was nothing—only a blank

interval. As if a single line in a column of newsprint had been neatly and

completely inked out.

What is this? Eddie

thought helplessly. What the hell is this shit?

Then he had to throw

up again, and maybe that was just as well; whatever you might say against it,

regurgitation had at least this much in its favor: as long as you were doing

it, you couldn't think of anything else.

3

I've come through. I'm

in the sky-carriage, the gunslinger thought.

And, a second later: He sees me in the mirror!

Roland pulled back—did

not leave but pulled back, like a child retreating to the furthest corner of a

very long room. He was inside the sky-carriage; he was also inside a man who

was not himself. Inside The Prisoner. In that first moment, when he had been

close to the front (it was the only way he could describe it), he had

been more than inside; he had almost been the man. He felt the man's

illness, whatever it was, and sensed that the man was about to retch. Roland

understood that if he needed to, he could take control of this man's body. He

would suffer his pains, would be ridden by whatever demon-ape rode him, but if

he needed to he could.

Or he could stay back

here, unnoticed.

When the prisoner's

fit of vomiting had passed, the gun-slinger leaped forward—this time all the

way to the front. He understood very little about this strange

situation, and to act in a situation one does not understand is to invite the

most terrible consequences, but there were two things he needed to know—and he

needed to know them so desperately that the needing outweighed any consequences

which might arise.

Was the door he had come

through from his own world still there?

And if it was, was his

physical self still there, collapsed, untenanted, perhaps dying or already dead

without his self's self to go on unthinkingly running lungs and heart and

nerves? Even if his body still lived, it might only continue to do so until

night fell. Then the lobstrosities would come out to ask their questions and

look for shore dinners.

He snapped the head

which was for a moment his head around in a fast backward glance.

The door was still

there, still behind him. It stood open on his own world, its hinges buried in

the steel of this peculiar privy. And, yes, there he lay, Roland, the last

gunslinger, lying on his side, his bound right hand on his stomach.

I'm breathing, Roland

thought. I’ll have to go back and move me. But there are things to do

first. Things . . .

He let go of the

prisoner's mind and retreated, watching, waiting to see if the prisoner knew he

was there or not.

4

After the vomiting

stopped, Eddie remained bent over the basin, eyes tightly closed.

Blanked there for a

second. Don't know what it was. Did I look around?

He groped for the

faucet and ran cool water. Eyes still closed, he splashed it over his cheeks

and brow.

When it could be

avoided no longer, he looked up into the mirror again.

His own eyes looked

back at him.

There were no alien

voices in his head.

No feeling of being

watched.

You had a momentary

fugue, Eddie, the great sage and eminent junkie advised him. A

not uncommon phenomenon in one who is going cool turkey.

Eddie glanced at his

watch. An hour and a half to New York. The plane was scheduled to land at 4:05

EDT, but it was really going to be high noon. Showdown time.

He went back to his

seat. His drink was on the divider. He took two sips and the stew came back to

ask him if she could do any thing else for him. He opened his mouth to say no.

. .and then there was another of those odd blank moments.

5

"I'd like

something to eat, please," the gunslinger said through Eddie Dean's mouth.

"We'll be serving

a hot snack in—"

"I'm really

starving, though," the gunslinger said with perfect truthfulness.

"Anything at all, even a popkin—"

"Popkin?"

the army woman frowned at him, and the gunslinger suddenly looked into the

prisoner's mind. Sandwich . . . the word was as distant as the murmur

in a conch shell.

"A sandwich,

even," the gunslinger said.

The army woman looked

doubtful. "Well... I have some tuna fish ..."

"That would be

fine," the gunslinger said, although he had never heard of tooter fish in

his life. Beggars could not be choosers.

"You do look

a little pale," the army woman said. "I thought maybe it was

air-sickness."

"Pure

hunger."

She gave him a

professional smile. "I'll see what I can rustle up."

Russel? the

gunslinger thought dazedly. In his own world to russel was a slang verb

meaning to take a woman by force. Never mind. Food would come. He had no idea

if he could carry it back through the doorway to the body which needed it so

badly, but one thing at a time, one thing at a time.

Russel, he

thought, and Eddie Dean's head shook, as if in disbelief.

Then the gunslinger

retreated again.

6

Nerves, the

great oracle and eminent junkie assured him. Just nerves. All part of the

cool turkey experience, little brother.

But if nerves was what

it was, how come he felt this odd sleepiness stealing over him—odd because he

should have been itchy, ditsy, feeling that urge to squirm and scratch that

came before the actual shakes; even if he had not been in Henry's "cool turkey"

state, there was the fact that he was about to attempt bringing two pounds of

coke through U.S. Customs, a felony punishable by not less than ten years in

federal prison, and he seemed to suddenly be having blackouts as well.

Still, that feeling of

sleepiness.

He sipped at his drink

again, then let his eyes slip shut.

Why'd you black out?

I didn't, or she'd be

running for all the emergency gear they carry.

Blanked out, then.

It's no good either way. You never blanked out like that before in your life. Nodded

out, yeah, but never blanked out.

Something odd about

his right hand, too. It seemed to throb vaguely, as if he had pounded it with a

hammer.

He flexed it without

opening his eyes. No ache. No throb. No blue bombardier's eyes. As for the blank-outs,

they were just a combination of going cool turkey and a good case of what the

great oracle and eminent et cetera would no doubt call the smuggler's blues.

But I'm going to

sleep, just the same, he thought. How 'bout that?

Henry's face drifted by

him like an untethered balloon. Don't worry, Henry was saying. You'll

be all right, little brother. You fly down there to Nassau, check in at the

Aquinas, there'll be a man come by Friday night. One of the good guys. He'll

fix you, leave you enough stuff to take you through the weekend. Sunday night

he brings the coke and you give him the key to the safe deposit box. Monday

morning you do the routine just like Balazar said. This guy will play; he knows

how it's supposed to go. Monday noon you fly out, and with a face as honest as

yours, you'll breeze through Customs and we'll be eating steak in Sparks before

the sun goes down. It's gonna be a breeze, little brother, nothing but a cool

breeze.

But it had been sort

of a warm breeze after all.

The trouble with him

and Henry was they were like Charlie Brown and Lucy. The only difference was

once in awhile Henry would hold onto the football so Eddie could kick

it—not often, but once in awhile. Eddie had even thought, while in one of his

heroin dazes, that he ought to write Charles Schultz a letter. Dear Mr.

Schultz, he would say. You're missing a bet by ALWAYS having Lucy pull

the football up at the last second. She ought to hold it down there once in

awhile. Nothing Charlie Brown could ever predict, you understand. Sometimes

she'd maybe hold it down for him to kick three, even four times in a row, then

nothing for a month, then once, and then nothing for three or four days, and

then, you know, you get the idea. That would REALLY fuck the kid up, wouldn't

it?

Eddie knew it

would really fuck the kid up.

From experience he

knew it.

One of the good guys, Henry

had said, but the guy who showed up had been a sallow-skinned thing

with a British accent, a hairline moustache that looked like something out of a

1940s film noire, and yellow teeth that all leaned inward, like

the teeth of a very old animal trap.

"You have the

key, Senor?" he asked, except in that British public school accent

it came out sounding like what you called your last year of high school.

"The key's

safe," Eddie said, "if that's what you mean."

"Then give it to

me."

"That's not the

way it goes. You're supposed to have something to take me through the weekend.

Sunday night you're supposed to bring me something. I give you the key. Monday

you go into town and use it to get something else. I don't know what, 'cause

that's not my business."

Suddenly there was a

small flat blue automatic in the sallow-skinned thing's hand. "Why don't

you just give it to me, Senor? I will save time and effort; you will

save your life."

There was deep steel

in Eddie Dean, junkie or no junkie. Henry knew it; more important, Balazar knew

it. That was why he had been sent. Most of them thought he had gone because he

was hooked through the bag and back again. He knew it, Henry knew it, Balazar,

too. But only he and Henry knew he would have gone even if he was as straight

as a stake. For Henry. Balazar hadn't got quite that far in his figuring, but

fuck Balazar.

"Why don't you

just put that thing away, you little scuzz?" Eddie asked. "Or do you

maybe want Balazar to send someone down here and cut your eyes out of your head

with a rusty knife?"

The sallow thing

smiled. The gun was gone like magic; in its place was a small envelope. He

handed it to Eddie. "Just a little joke, you know."

"If you say

so."

"I see you Sunday

night."

He turned toward the

door.

"I think you

better wait."

The sallow thing

turned back, eyebrows raised. "You think I won't go if I want to go?"

"I think if you

go and this is bad shit, I'll be gone tomorrow. Then you'll be in deep shit."

The sallow thing

turned sulky. It sat in the room's single easy chair while Eddie opened the

envelope and spilled out a small quantity of brown stuff. It looked evil. He

looked at the sallow thing.

"I know how it

looks, it looks like shit, but that's just the cut," the sallow thing

said. "It's fine."

Eddie tore a sheet of

paper from the notepad on the desk and separated a small amount of the brown

powder from the pile. He fingered it and then rubbed it on the roof of his

mouth. A second later he spat into the wastebasket.

"You want to die?

Is that it? You got a death-wish?"

"That's all there

is." The sallow thing looked more sulky than ever.

"I have a

reservation out tomorrow," Eddie said. This was a lie, but he didn't

believe the sallow thing had the resources to check it. "TWA. I did it on

my own, just in case the contact happened to be a fuck-up like you. I don't

mind. It'll be a relief, actually. I wasn't cut out for this sort of

work."

The sallow thing sat

and cogitated. Eddie sat and concentrated on not moving. He felt like

moving; felt like slipping and sliding, hipping and bopping, shucking and

jiving, scratching his scratches and cracking his crackers. He even felt his eyes

wanting to slide back to the pile of brown powder, although he knew it was

poison. He had fixed at ten that morning; the same number of hours had gone by

since then. But if he did any of those things, the situation would change. The

sallow thing was doing more than cogitating; it was watching him, trying to

calculate the depth of him.

"I might be able

to find something," it said at last.

"Why don't you

try?" Eddie said. "But come eleven, I turn out the light and put the

DO NOT DISTURB sign on the door, and anybody that knocks after I do that, I

call the desk and say someone's bothering me, send a security guy."

"You are a

fuck," the sallow thing said in its impeccable British accent.

"No," Eddie

said, "a fuck is what you expected. I came with

my legs crossed. You want to be here before eleven with something that I can

use—it doesn't have to be great, just something I can use—or you will be one

dead scuzz."

7

The sallow thing was

back long before eleven; he was back by nine-thirty. Eddie guessed the other

stuff had been in his car all along.

A little more powder

this time. Not white, but at least a dull ivory color, which was mildly

hopeful.

Eddie tasted. It

seemed all right. Actually better than all right. Pretty good. He rolled a bill

and snorted.

"Well, then,

until Sunday," the sallow thing said briskly, getting to its feet.

"Wait,"

Eddie said, as if he were the one with the gun. In a way he was. The gun was

Balazar. Emilio Balazar was a high-caliber big shot in New York's wonderful

world of drugs.

"Wait?" the

sallow thing turned and looked at Eddie as if he believed Eddie must be insane.

"For what?"

"Well, I was

actually thinking of you," Eddie said. "If I get really sick from

what I just put into my body, it's off. If I die, of course it's off. I

was just thinking that, if I only get a little sick, I might give you

another chance. You know, like that story about how some kid rubs a lamp and

gets three wishes."

"It will not make

you sick. That's China White."

"If that's China

White," Eddie said, "I'm Dwight Gooden."

"Who?"

"Never

mind."

The sallow thing sat

down. Eddie sat by the motel room desk with the little pile of white powder

nearby (the D-Con or whatever it had been had long since gone down the John).

On TV the Braves were getting shellacked by the Mets, courtesy of WTBS and the

big satellite dish on the Aquinas Hotel's roof. Eddie felt a faint sensation of

calm which seemed to come from the back of his mind . . . except where it was

really coming from, he knew from what he had read in the medical journals, was

from the bunch of living wires at the base of his spine, that place where

heroin addiction takes place by causing an unnatural thickening of the nerve

stern.

Want to take a quick

cure? he had asked Henry once. Break your spine,

Henry. Your legs stop working, and so does your cock, but you stop needing the

needle right away.

Henry hadn't thought

it was funny.

In truth, Eddie hadn't

thought it was that funny either. When the only fast way you could get rid of

the monkey on your back was to snap your spinal cord above that bunch of

nerves, you were dealing with one heavy monkey. That was no capuchin, no cute

little organ grinder's mascot; that was a big mean old baboon.

Eddie began to

sniffle.

"Okay," he

said at last. "It'll do. You can vacate the premises, scuzz."

The sallow thing got

up. "I have friends,'' he said. “They could come in here and do things to

you. You'd beg to tell me where that key is."

"Not me,

champ," Eddie said. "Not this kid." And smiled. He didn't know

how the smile looked, but it must not have looked all that cheery because the

sallow thing vacated the premises, vacated them fast, vacated them without

looking back.

When Eddie Dean was

sure he was gone, he cooked.

Fixed.

Slept.

8

As he was sleeping

now.

The gunslinger,

somehow inside this man's mind (a man whose name he still did not know; the

lowling the prisoner thought of as "the sallow thing'' had not known it,

and so had never spoken it), watched this as he had once watched plays as a

child, before the world had moved on. . . or so he thought he watched, because

plays were all he had ever seen. If he had ever seen a moving picture, he would

have thought of that first. The things he did not actually see he had been able

to pluck from the prisoner's mind because the associations were close. It was

odd about the name, though. He knew the name of the prisoner's brother, but not

the name of the man himself. But of course names were secret things, full of

power.

And neither of the

things that mattered was the man's name. One was the weakness of the addiction.

The other was the steel buried inside that weakness, like a good gun sinking in

quicksand.

This man reminded the

gunslinger achingly of Cuthbert.

Someone was coming.

The prisoner, sleeping, did not hear. The gunslinger, not sleeping, did, and

came forward again.

9

Great, Jane

thought. He tells me how hungry he is and I fix something up for him because

he's a little bit cute, and then he falls asleep on me.

Then the passenger—a

guy of about twenty, tall, wearing clean, slightly faded bluejeans and a

paisley shirt—opened his eyes a little and smiled at her.

"Thankee

sai," he said—or so it sounded. Almost archaic ... or

foreign. Sleep-talk, that's all, Jane thought.

"You're

welcome." She smiled her best stewardess smile, sure he would fall asleep