This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any resemblance to real people or events is purely coincidental.

Blood and Ivory: A Tapestry: Copyright © 2002 by P. C. Hodgell

All rights reserved by the publisher. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without the written permission of the publisher, except for the purpose of reviews.

Hearts of Woven Shadow Copyright © 2002 by P. C. Hodgell,

(Original to this collection.)

Lost Knots Copyright © 2002 by P. C. Hodgell,

(Original to this collection.)

Among the Dead Copyright © 2002 by P. C. Hodgell,

(Original to this collection.)

Child of Darkness Copyright © 1980 by P. C. Hodgell,

(Originally appeared in Berkley Showcase Number II.)

A Matter of Honor Copyright © 1977 by P. C. Hodgell,

(Originally appeared in Clarion SE)

Bones Copyright © 1984 by P. C. Hodgell,

(Originally appeared in Elsewhere Volume III.)

Stranger Blood Copyright © 1985 by P. C. Hodgell,

(Originally appeared in Imaginary Lands.)

A Ballad of the White Plague Copyright © 2002 by P. C. Hodgell

(Originally appeared in The Confidential Casebook of Sherlock Holmes)

Baen Publishing Enterprises

P.O. Box 1403

Riverdale, NY 10471

www.baen.com

Paper versions are available from

Meisha Merlin Publishing Inc.

www.meishamerlin.com

ISBN: Hardcover 1-892065-72-XSoft cover 1-892065-73-8

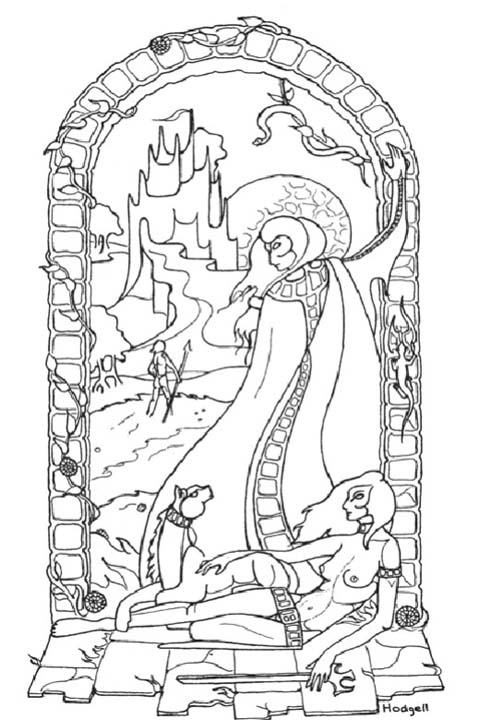

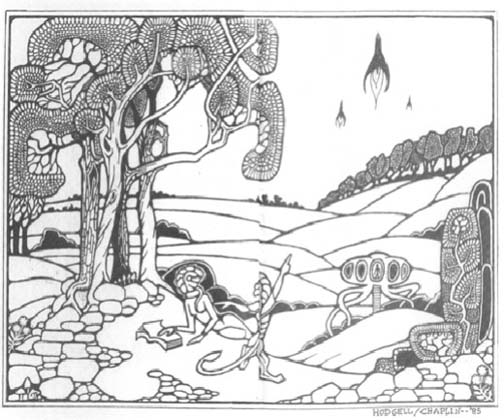

Cover art by P. C. Hodgell

All interior art work done by, and copyrighted by P. C. Hodgell

First Baen Ebook, April 2007

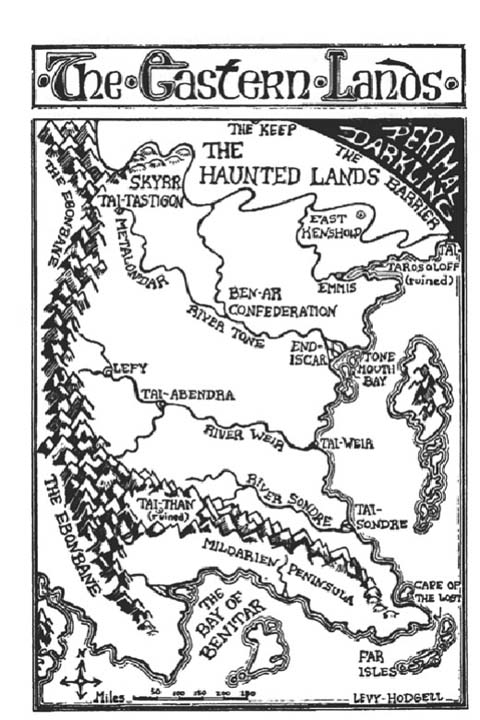

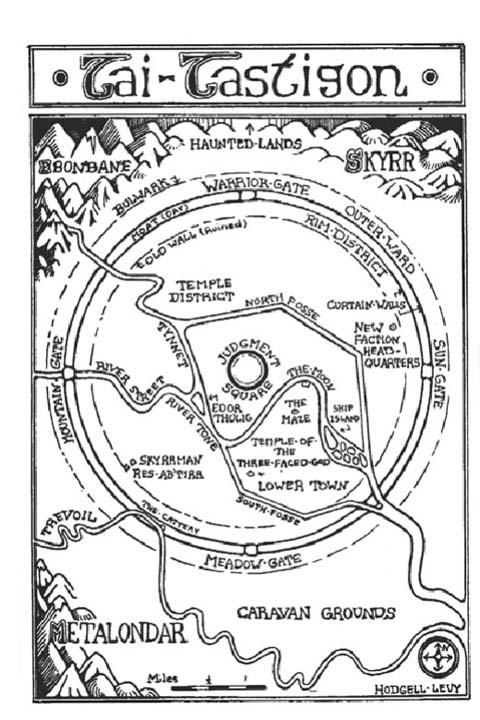

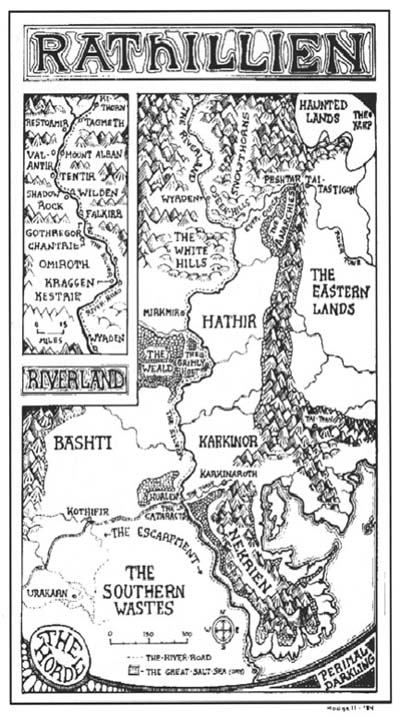

"Out of the Haunted Lands to the city of Tai-tastigon comes Jame, one of the few remaining Kencyr left to carry on their millennium-long battle against Perimal Darkling, an entity of primal evil. Establishing herself in the city, Jame becomes an apprentice in the Thieves' Guild, make friends and enemies, and begins to develop her magical abilities. Hodgell has crafted an excellent and intricate fantasy, with humor and tragedy, and a capable and charming female hero. Highly recommended."—Library Journal, September 15, 1985

"God Stalk by P.C. Hodgell takes some familiar elements of fantasy—a city of many gods, a Thieves' Guild, a heroine with the strange powers of an ancient race—and blends them into a delightful concoction bubbling with originality. The heroine, Jame, stumbles into the city of Tai-tastigon suffering from amnesia and the strain of headlong flight from her enemies. She finds herself in an apparently uninhabited maze, a chaos of weird supernatural effects. When the inhabitants finally appear, they're a quirky, lively, and (most of them) down-to-earth group who draw Jame into the network of their lives and concerns.

"With this novel, [Hodgell] makes a promising debut, and its sequels could turn out to be major contributions to the fields."—Locus, September, 1982

"It's become increasingly hard to do anything new in the high-fantasy field, but there's still a big difference between those who can only reheat the same old stew and those who can take full advantage of all that's been done before to brew up a fresh mix. Hodgell proves with this debut novel to be in the latter group.

"Jame is a fully fleshed character in a rich fantasy milieu influenced by the likes of C.L. Moore and Elizabeth Lynn. Like their work, this novel and the series it begins should prove popular."—Publishers' Weekly, September 21, 1982

"Those who regard fantasy as an insignificant branch of the literary tree lack understanding of the many ways in which all people approach that mystic realm we call 'reality.' Reading God Stalk might allow them to confront a few of their own demons. For the rest of us, whether because we are seeking ways of looking at our lives through fiction or because we simply want to explore someone else's vision, Hodgell's book is a dramatic introduction to a new world that both embodies and transcends our own."—The Minnesota Daily, September 28, 1982

"In God Stalk, P.C. Hodgell set in motion a convoluted plot involving such standard elements of fantasy as dark lords, thieves' guilds, and homey inns, and she transcended convention through sheer force of imagination. The sequel, Dark of the Moon, takes all these tendencies even further, with more convolutions, more familiar themes, and—again—a redeeming, delightful originality of vision.

Already she brings a welcome freshness and flair to a field where creativity often seems more the exception than the rule."—Locus, September, 1985

"P.C. Hodgell is one of the best young fantasy writers we have and yet her work is not all that well known. This is partly due to her low productivity (two novels and a handful of short stories in the last ten years) and partly due to the difficulty and darkness of her work. Where so much of contemporary fantasy seems to consist of little more than a mindless reworking of Tolkien and Howard, Hodgell's affinities lie with the complex plotting of Mervyn Peake, the dark humor of Fritz Leiber, and the gruesomely poetic detail work of Clark Ashton Smith."—Fantasy Magazine, October 1985

"You come away from one of Pat's books with your mind and heart humming. The reverberations of what you've read carry through into the world beyond the book's pages and you see things differently. Connections that originated in the novels link with our own lives, offering insights and questions, both of which are important as we make our way through the confusing morass of the world. The insights show us established paths we can take that we might not have seen before. The questions make us look a little harder so that we can forge our own routes."

"Like many of us, Pat has cast her net into the pool of what went before, but unlike most, she replenishes those waters with more than what she took. You can't ask much more of an artist and for Pat's unwavering commitment to give us so much, she deserves not only our support, but our admiration and respect as well."

"Pat Hodgell is one of the original voices and great talents of our field and I couldn't be happier to see her work back in print once more, with at least a fourth novel scheduled to appear in the future. If you're new to her work, get comfortable and allow a master storyteller to take you in hand."—Charles de Lint

An introduction to "Hearts of Woven Shadow,"

"Lost Knots," and "Among the Dead"

Epic fantasies usually begin in medias res, in the middle of things. Consider, for example, how much history comes before we meet Frodo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings, and I'm not just talking about its prequel, The Hobbit. The Silmarillion will give you a better idea. In this eon-long context, the One Ring can be seen as merely a loose end that must be tidied up before it and its master can destroy all of Middle-earth, smashing sundry lives in the process including those of various innocent hobbits.

This pattern runs through much of modern fantasy. The past is a looming shadow that shapes the present and threatens the future. Characters thus totter between light and dark, between simple, everyday life and cosmic destruction, on a scale that sometimes boggles the mind even of their creator.

To lower our discourse a notch, I have always been aware that certain events in the past shape my heroine Jame's life and world. Gerridon's fall is perhaps the most dramatic instance—all the more so because, like Sauron, Gerridon is still active behind the scenes some three thousand years later. In fact, he is Jame's uncle because his sister-consort, Jamethiel Dream-Weaver, is Jame's mother. How (and why) that happened is central to Jame's story. It also matters, of course, to her twin brother Torisen. They and one other are the innocents in my story, at least so far.

I knew many of the details before I sat down to write the following three stories, which appear here for the first time anywhere. However, I hadn't thought out all the ramifications. The time-line came as a surprise. So did Ganth Gray Lord, Jame and Tori's father. Is he also an innocent?

You decide.

P. C

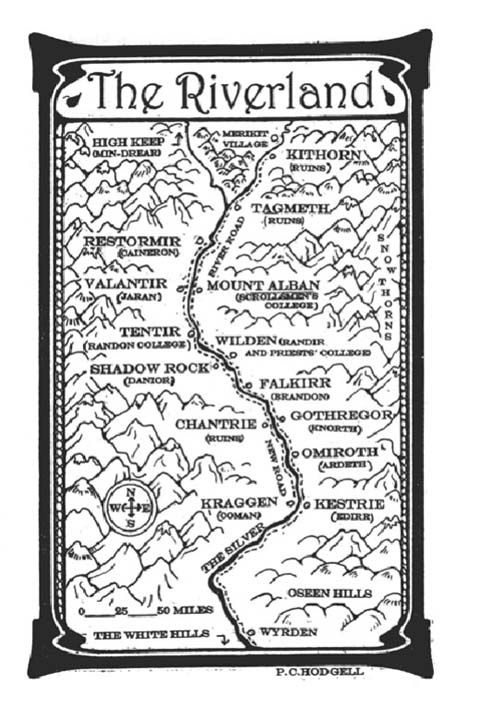

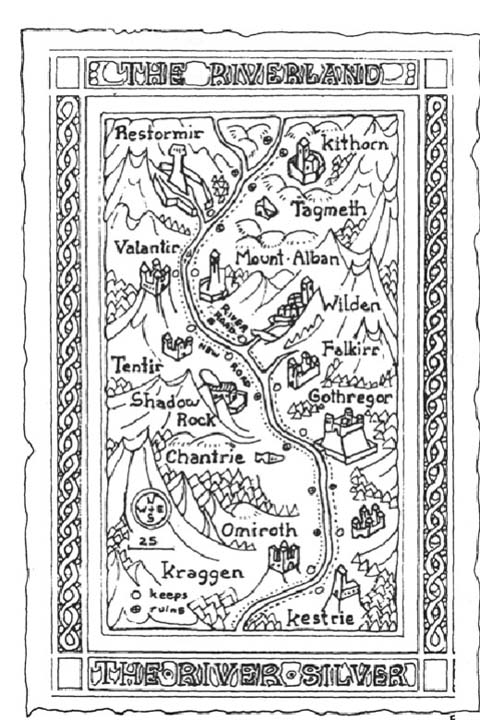

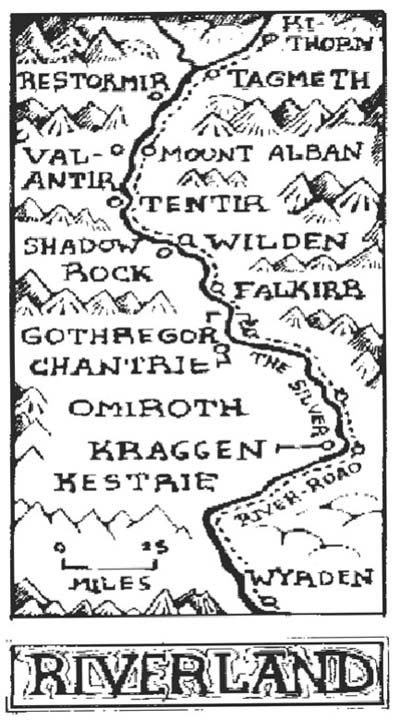

IT WAS THE SIXTH NIGHT of summer, and the moon was dark. High over the Riverland, wisps of cloud blew confusedly this way and that, making the stars flicker. Mountains blotted out the sky to east and west, but the hunched, gathering darkness to the north was far more profound, and ominous.

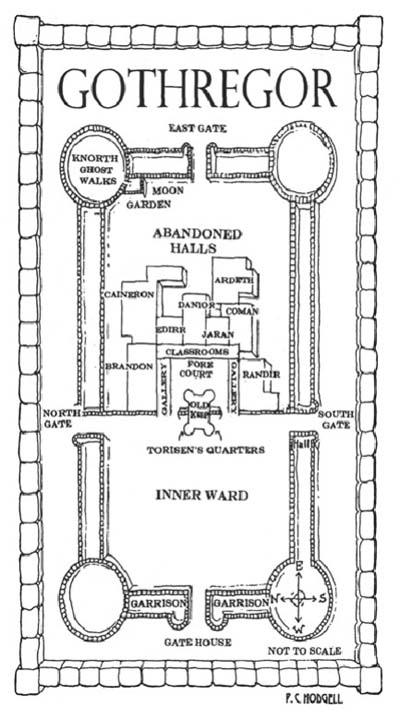

Gothregor's forecourt lay in deep shadow. Across it, however, the gallery windows of the Women's Halls flared briefly with wary light and flickered with shadows. No one slept. The fortress waited and watched as it had night after night after night.

"Dead!" cried a muffled voice. Stone ground on stone as if the very walls shrank from that terrible cry. "Dead, dead, dead!"

Between the forecourt and the inner ward of Gothregor rose the keep, ancient, fragile heart of House Knorth on Rathillien. Its door opening into darkness. The low-beamed hall within seemed to exhale—haaaaa—its chill breath rank with a hideous stench and the buzz of flies. Inside, footsteps paced the stone floor, their echo instantly smothered. On and on they went, around and around, and a low, hoarse voice went with them, muttering.

"How l-long?" asked one of the people standing in the doorway. He spoke in a husky whisper, as if the smell had taken him by the throat.

A large shape moved uneasily behind him. Furtive light from the windows opposite caught the glint of a randon captain's silver collar. "Five days, lord. Ever since we brought the body back from the college at Tentir. He won't let the priests have it."

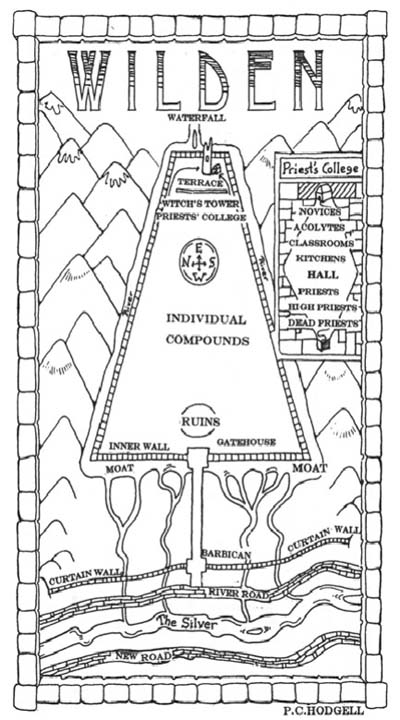

"Sweet Trinity. A soul trapped for f-five days in a rotting carcass . . . I don't understand." The Highborn ran distraught fingers through dark hair flecked with gray. He was young, barely eighteen, but life had already raked him with its claws. "What h-happened, Sere? How did my brother die? And why wasn't I told sooner? God's claws, I was only upriver at Wilden on house business! You m-must have passed right by me on the River Road, without a word. If this lady hadn't somehow learned of it . . . "

"I'd like to know how," muttered the tall Kendar named Sere.

He shot a hard look at the slender young woman standing back a pace, listening, motionless except for where the fretful wind teased her traveling cloak. Under hood and mask, her expression was unreadable.

Behind her, her attendant smirked. The lower half of his face seemed briefly to distort, the lip's corner hitching up into the shadow of his cowl, then snapping solemn-straight again.

Sere blinked, then rubbed tired eyes and turned his back on them both.

"The Randon College at Tentir has been sealed to prevent spread of the news," he said to the Highborn in a low voice. "The Commandant was to have come with us to explain what happened, but he preferred the White Knife. So have many here."

Behind him, another burst of flame bloomed above a courtyard hidden within Gothregor's crouching darkness. A gust of wind breathed the stench of pyres into the forecourt, and stray ashes drifted down, silent calamity riding the air.

"I have seen war, and death, and madness, but this . . . The Highlord's grief is . . . terrible. And contagious." A tremor, frightening in itself, shook his strong voice. "I think it could almost unmake our world. We randon are trained, after a fashion, to protect ourselves; but our children aren't. Lord, do something. After all, you are the Knorth Heir now."

The young Highborn flinched. "Trinity. I'd forgotten that. What a m-mess, and how like my dear brother to have caused it, even in death." He swallowed, and his thin face sharpened. "All right. Wait here. You too, lady."

Skirts rustled impatiently. "But . . . "

He rounded on her with a suppressed violence that sent her gliding backward several steps into the windy forecourt. Her attendant skipped out of the way.

"I said, wait!"

It was almost a berserker flare. The big randon tensed.

The hooded attendant put his hand on the young woman's shoulder and leaned forward to whisper in her ear. Her lips twitched into a brief smile.

"I had forgotten," she said in a low, pleasant voice, the purr of a cat to a mouse. "You were expelled from Tentir last fall, were you not, dear Ganth, for your . . . er . . . temper, as well as for that other thing which we Randir will never forget."

"M'lord Grayling left by choice," said the Kendar sharply. "You know very well, lady, that no blood price can be demanded for any . . . um . . . accident at the college. Even a fatal one. We wish he had stayed."

"To learn s-s-self—" Ganth clenched his fists, fighting the nervous stammer. "Control. There. As you see, I am neither berserker nor god-cursed S-s-shanir. I am not."

"So you say," murmured the lady, "and so, of course, you are. Or not."

Ganth Grayling took a deep breath. It was hard to remember how irresistible he had found this girl when they had first met, he a shy boy of thirteen, she a fine young lady at least three years his senior.

It had been Autumn's Eve, five years ago. His father was in the keep's low hall, chanting the names of the dead to keep their memory alive as he did every year on this night. The only better immortality was to win one's way into a singer's song or a scrollsman's scroll. Ganth's brother Greshan should have been with him, but had gone hunting instead. Time enough later, he had said, to learn who was who in that moldy gallery and Father, laughing, had let him go. There had been no question of his younger brother taking his place. After all, Ganth would never be highlord—or anything else worthwhile, according to Greshan. So he had walked among the white flowers of his grandmother's garden, wanted nowhere, feeling lonely and restless. Then, suddenly, there she was, black and silver in the starlight.

She shouldn't have been in the Moon Garden at all, of course: Highborn girls were usually confined to the Women's Halls of Gothregor where they were taught to become proper ladies. Then too, she had been trespassing on Knorth ground, avid to see how the Highlord's family lived; and he had been charmed into showing her.

"Lady Rawneth of the Randir," he said now with brittle courtesy. "I am s-sorry for your loss in this most recent tragedy, if one can be said to lose what one has never actually possessed, but this business concerns only my h-house."

As he turned back to the dark hall, the Kendar touched his arm. "Lord, be careful. He drove us out with Kin-Slayer, unsheathed."

The Highborn hesitated. That ill-omened blade had never yet been drawn without shedding blood.

He wished suddenly, intensely, that the randon would go in with him, and not for fear of any sword. Last fall, it was Sere who had welcomed him to Tentir, to the start of a new life as a randon cadet. He had thought, surrounded by so many other students, it would not matter that Greshan was also at the college, starting his final year. It had mattered. Now he must face his brother again . . . and his father. Alone.

Ganth stepped over the threshold and began to pull the door shut after him. Its lower edge grated loudly on the uneven floor.

The footsteps stopped. "Who's there?"

"I, Highlord." He fumbled for steel and flint on a ledge beside the door. "Your son."

The answer came in a hoarse howl, raw with pain. "My son is dead!" The hall seemed to rock. Ganth caught the doorpost to steady himself.

"Your other s-son, lord. Ganth Grayling."

He found the first wall torch by touch, struck fire, and kindled it, then the next, and the next. Between them, faces moved uneasily in the flaring light. Men and women, young and old, portrait tapestries woven out of threads teased from the clothes in which each had died—all had the distinctive Knorth faces: high cheekbones, large silver-gray eyes, thin mouths often twisted in pain, or arrogance, or cruelty. Kendar weavers had the right to portray their Highborn masters as they had been in life.

They had been kind (thank Trinity!) to his mother, Telarien, dead less than a year with the birth of her last child—Tieri, a daughter. She hung in shadow on the far wall, her death still a wound too raw to face.

These banners, however, were far more ancient, layered, many dating back to the Fall nearly three millennia ago. Unbidden, the ancient lament echoed in his mind:

Gerridon Highlord, Master of Knorth, a proud man was he. The Three People held he in his hands—Arrin-ken, Highborn, and Kendar. Wealth and power had he and knowledge deeper than the Sea of Stars. But he feared death. "Dread Lord," said Gerridon to the Shadow that Crawls, even to Perimal Darkling, ancient of enemies, "my god regards me not. If I serve thee, wilt thou preserve me, even to the end of time?" Night bowed over him. Words they spoke. Then went my lord Gerridon to his sister and consort, Jamethiel Dream-Weaver, and said, "Dance out the souls of the faithful, that darkness may enter in." And she danced.

Two-thirds of the Kencyrath had fallen that night and stayed in the shadows to serve their dire master until, one by one, he devoured their souls, reaped for him by the Dream-Weaver. That was the price of his immortality, paid by others.

But these Kencyr had escaped, following their new Highlord, Glendar, into this new world, Rathillien. "A watch we will keep" they had said, "and our honor someday avenge. Alas for the greed of a man and the deceit of a woman, that we should come to this!"

Three thousand years ago. One hundred and fifty generations. Now here they hung moldering in a dark hall, as long as thread clung to thread and their names were remembered.

Ganth flinched. Starting out of the shadows in front of him was a tapestry that had given him and many another of his house nightmares since childhood. Perhaps that was its purpose. Although one of the oldest banners in the hall, it was always hung outermost, "to warn."

"Of w-what?" Ganth had once asked his grandmother, Kinzi.

"Of heart's desire," she had said. "Of passions strong enough to break the soul. We are a passionate house, and not always wise."

Most of the dead were portrayed with hands lowered in benediction. This woman, however, had raised them to cover her face. Blood ran down between her long fingers, each one tipped with an ivory claw, over gaunt cheeks, into a mouth that gaped in a silent scream.

Everyone knew that insanity ran in the Highlord's house. Most blamed it on the Shanir taint, the curse of the Old Blood, that carried with it both power and madness. This lady had been Shanir, allied by her traits to That-Which-Destroys, the Third Face of God. Power and madness, madness and . . .

Stop it, Ganth thought. Defiantly, he touched the woman's frayed cheek.

His fingers came away wet. The tapestry was bleeding. As he backed away, he saw that many more were as well. Blood trickled down their sodden threads and dripped, stealthily, onto the floor. The room brimmed with its furtive patter.

"Ancestors preserve me," he murmured, and turned.

Kin-Slayer's point wavered inches from the hollow of his throat. Down its flame-lit length, he met the pale, mad eyes of his father, Gerraint Highlord.

"Your brother was worth a dozen of you! Why is he dead and you still alive?"

The words fell like a sharp blow on thin ice. Beneath, Ganth sensed black waters, colder than death. Gerraint might say anything now. So might he. Control, he thought desperately, fighting to breathe. Keep control. He is old, and sick with grief, and very, very dangerous.

Skirts rustled behind them. Rawneth had followed Ganth into the hall and now stood by the pall-draped catafalque, her attendant hovering dusty black in her torch-cast shadow. She pushed back her hood. Firelight shone off sleek ebon hair, intricately braided.

"So it is true," she said, her voice muffled through the cloth that she held to her face against the stench. "I thought the rumor was a trick to put me off."

Gerraint stared at her. "You fool!" he spat at his son. "Why did you bring that woman here?"

Ganth stood still. Despite Kin-Slayer at his throat, he refused to back into that bleeding banner, within reach of those claw-tipped fingers. "You s-sent me to Wilden to make a contract with 'that woman,' Lord Randir's daughter, to heal the breach between our houses. Remember? However, Lady Rawneth preferred my brother Greshan to m-me, or perhaps only the next highlord to a second son."

"Ha. Not such a fool, then, as you."

"Oh!" Her exclamation made them both turn again sharply. "He moved!"

In a moment, Gerraint was beside the bier. He dropped Kin-Slayer, seized a cold, flaccid hand and chaffed it between his own scarcely warmer ones. "My son, my son, wake up! You can't be dead! I know you aren't!"

So far, death had scarcely touched Greshan's handsome face. In life, good looks and charm had always gotten him whatever he wanted—that, and being the long-desired, half-despaired of heir to a house desperately short on sons. Five years later, Ganth had come as such a surprise that Telarien had nearly died giving birth to him. She had never been well again. It was hard to tell whom Gerraint blamed most for her death: Ganth, the infant Tieri, or himself.

Now here lay Greshan, his only other son, like an effigy of the perfect hero, clothed in gilded leather armor whose gleam was only slightly dimmed by five days of dust. Beyond that, all that betrayed him was the dark fluid leaking from his mouth and nose and, like bloody tears, from under the long fringe of his eyelashes. That, and the flies.

His chest rose again slightly as if with a secret, in-drawn breath.

Aahhh . . . ! breathed the death banners on the walls.

Neither they nor he exhaled. Leather armor strained taut, creaking, over Greshan's stomach.

"Gas," said Rawneth, with interest, drawing closer again. "The body is bloating. Do you suppose it will eventually explode?"

Ganth gingerly picked up Kin-Slayer. "Lady, for Perimal's s-s-sake!" And this was the man whom she had wanted for a consort?

Greshan had found them in Grandmother Kinzi's quarters. While going through the Matriarch's clothing chests, Rawneth had unearthed an intricate piece of needlework, ivory with age. She was fingering it while Ganth looked on, increasingly nervous and anxious that she should leave. What if Gran came back? She was only across Gothregor in the Women's Halls, visiting the blind Ardeth Matriarch, Adiraina.

"Well, well, well." Greshan lounged in the doorway. He reeked of the hunt, of sweat, blood, and offal; a filthy, gorgeously embroidered coat was draped over one shoulder. Tunic laces hung loose, half undone, at his throat. "What have you brought me, Gander? Will I enjoy it?"

He and Rawneth talked. Afterward, Ganth couldn't remember exactly what they had said, only the tone, first wary on her part, then bantering on both.

They circled each other beside Kinzi's bed. Her long, black hair stirred and rose about her as if in an updraft, although the room was close and still. Her fingertips brushed against his bare chest, leaving faint red lines. He slid his hand (the nails dirty, Ganth noted with revulsion, dried blood caked under them) through her shining hair, then suddenly gripped it and jerked her face up to his. She stifled a cry, but tears of pain glittered on her cheeks. He bent his head, licked them off, and shuddered.

"Bitter," he said thickly. "And potent. Is the magic in your blood as strong?"

"Taste it and see."

The tendrils of black hair that had wound about his hand slowly relaxed into a caress. She gave a husky laugh.

"You should meet my cousin Roane. He likes to play games too."

"Later. Gangray, get out."

She eyed Ganth askance over Greshan's shoulder, black eyes glittering half in mockery, half in challenge. "Oh, let the little boy watch . . . unless he wishes to join us and become a man."

Let him watch.

Greshan had watched him at Tentir. Ganth hadn't noticed at first. There was so much to do, so much to learn. For the first time in his life, he had felt he might amount to something. He even had friends, after a fashion, with whom to swim after the dust and heat of the day. Then he had seen Greshan and the Randir Roane watching him from the bank. No one ever wore clothes in that mountain pool, but of them all only Ganth had felt suddenly, terribly, naked.

Now, beside his brother's bier, he looked down at Gerraint's wild, white hair, haloed by carrion flies, and his face twisted. "Father, please, let him go. Besides, h-he wasn't the hero you think. He could be petty, and vicious, and . . . "

Gerraint lunged. Ganth found himself trying to level Kin-Slayer at his father's throat to hold him off. The blade fell from his nerveless hand, ringing, onto the stone floor.

"A lesson for you, boy. Only those prepared to use that sword can wield it. What are you but an empty gesture? Petty? Vicious? Greshan?" He laughed, a bark of searing scorn. "Don't think I've forgotten the vile lies you told about him when you were both children. Oh, I knew then how little to value you!"

"What lies?" asked Rawneth.

Ganth shot her a harassed look. Lies were the death of honor. True or not, one did not speak of such things in front of an enemy, and that she clearly was, now and forever.

Gerraint had bent again over the body and cradled its face between his hands. Gelid blood oozed over his long, thin fingers and emerald signet ring, down the pall and onto the floor. Drip, drip, drip. "Oh, my son, my son. You should have come home in triumph, with full randon honors. Instead, your welcome feast rots in the hall and the dogs fight over it. I don't understand. I don't understand."

"Oh, but surely the Knorth Heir goes to Tentir for more than a pretty collar," said Rawneth. Her spy whispered in her ear again. "Ah. I see! The randon decide if he is worthy to become the next highlord. If not, well, unfit lordan have died at Tentir before, one way or another, have they not? Unavenged, too. As you keep telling me, Tentir will allow no blood price."

Ganth remembered how little attention Greshan had paid to his duties at Tentir, assuming that no one would dare deny the Knorth Lordan his collar in the end. Surely that hadn't been enough to get him killed, though. Besides, this past season the college had been under the command of the Knorth war-leader—until he had committed suicide rather than explain the Heir's death to his father.

We have enemies, Ganth thought, fully realizing it for the first time. Perhaps even within our own halls.

Gerraint was shaking his head, harder and harder. White hair whipped. "No, no, no! Greshan, unworthy? Madness. You!" He seized Ganth by the jacket. "Somehow, this is all your fault. You were always jealous of him!"

"No! Yes. S-sometimes. I had no cause to love him, but I never wished him dead. Trinity! D'you think I want to be the next highlord?"

"Over my dead body!"

"Of course," murmured Rawneth. "How else? And, of course, over Greshan's too."

Gerraint ignored her. "It goes back to last autumn and the death of that wretched Randir, doesn't it? Doesn't it? Damn you, boy, what did you do?"

"You know what I did." Ganth felt himself growing cold with anger and alarm. His stammer had disappeared. Control, he thought desperately. Control. Remember only so much, nothing more. "I killed Roane. At Tentir. In my brother's quarters. At three in the morning."

The dormitory in the Knorth barracks, the row of cots full of soft breathing. How many slept, exhausted by the day? How many lay awake, as he did, listening to his brother's nightly carousal in his chambers overhead?

(Don't remember. Don't! But he did.)

Greshan's drunken shout of laughter. Roane laughed too, but more softly. Ganth knew, instinctively, that the Randir was drinking one cup to every three of the Knorth Lordan, while seeming to keep pace. Roane had been the Heir's shadow ever since Ganth had come to Tentir, and probably before that. Together, they concocted the various cruel "jokes" for which Greshan was becoming famous. What were they plotting tonight?

A hand on his shoulder, making him jump. The voice of Roane's servant in his ear: "The Lordan wants you. In his quarters. Now."

Ganth wrenched his mind back to the present. He met Rawneth's eyes over his father's shoulder. "D-do you know what your cousin and my dear brother tried to do to me that night, lady?"

She shrugged, dismissing it. "Boys will be boys."

For the first time, the old man looked almost frightened. He clung to Ganth. "What is she saying? What does she mean?"

"If I told you, f-father, you would only call me a liar. Again."

"No." His grip tightened. "I won't listen. No, no, NO!"

Ganth cried out in pain as Gerraint's power surged through him, reaching out, ruthlessly pulling in strength from everyone, everything, bound to the Highlord's will, down to the very stones of Gothregor. Distant voices screamed. The whole fabric of the Knorth was being wrenched out of shape, about to tear. Through his father, Ganth felt minds shatter and spirits crack. His own heart lurched in his chest. He wondered if he was dying. He had often wanted to, but not now, not now. So this too was the power of a highlord, to break as well as to bind.

"I think it could unmake our world," the randon captain had said.

Ganth could sense him now, standing outside the door of the keep like a rock, all his training at full stretch to anchor the Knorth's reeling soulscape. Other wills scattered throughout the fortress joined his, most randon but one above all others so strong that Ganth could see her standing small and gallant at her window overlooking the Moon Garden—his grandmother Kinzi, the Knorth Matriarch. Behind her, a lesser presence but still there, adding her strength, was his young cousin Aerulan, and in her arms his infant sister Tieri.

Kinzi was staring across the dark roofs at the tower keep.

"Gerraint!" she cried. Her high, clear voice rang through the troubled air, piercing bone and stone. Dull thunder from the north rumbled under it. "What are you doing? Stop it, at once!"

Her cry flung father and son apart. Gerraint staggered against the bier, shaking it; Ganth reeled into the eastern wall and slid down its pad of banners to the floor.

"Not . . . strong . . . enough," Gerraint panted.

Rawneth stood rigid with anger. "Kinzi. Always Kinzi."

Just so, she had bared her teeth at the Knorth Matriarch on that distant night when Kinzi had found Rawneth and Greshan in her quarters. Perhaps Kinzi had even heard the Randir's last, taunting words flung at a young Ganth: "Let him watch . . . unless he wishes to join us and become a man."

Ganth had always thought of his grandmother as a fine-boned sparrow. True, she was remarkably trim and unusually small for a Highborn. When he hugged her, he could rest his chin on the top of her neatly groomed head. That seemed so strange since all his life, growing up, he had only felt safe in her shadow. Greshan had jeered at him for that, but never in front of Grandmother herself. No one laughed at Kinzi Keen-Eyed.

Before, Ganth had never quite understood. She was his dear, tiny Gran, who sang at dawn as sweet as any bird and loved riddles. He had smiled at rumors that the Highlord did nothing without her advice and had dismissed whispered stories of her fabled rage, which he had never seen.

He saw it now.

Greshan's sneer froze. Slack-jawed, for once he looked every inch the stupid man that he was. He gasped. His breath smoked on the suddenly chill air.

Kinzi stood in the doorway, motionless. "Leave," she said to her grandson, in a tone to freeze the blood. "Now." Greshan goggled at her, made a choking sound, and reeled past, out of the room.

Knorth and Randir faced each other.

"So. You would bind the Highlord's heir if you could."

"Do you think it beyond me, Matriarch?"

"I think you believe that very little is."

They were circling each other now, gliding, the tall, elegant girl and the tiny old woman. Ganth backed into the corner, as far away as he could get. It seemed to him as if the room was tilting this way and that, twisted by the clash of their wills; but there was no question who was the stronger.

Kinzi held out her small hand. "Give me that."

Ganth realized that all this time Rawneth had been clutching the embroidery with its fine pattern of knotwork. Now she tried instinctively to hide it behind her back, but Kinzi's Rawneth flung wide her arms with a cry of triumph: "Ha, Kinzi!"

Then she unfastened her cloak and let it fall. Beneath it she wore a tight, black bodice and a full skirt spangled with stars that glinted as she began slowly to turn, arms out again, long fingers winnowing the air. She had let her nails grow almost into talons, Ganth noted with a spasm of nausea. Behind her mask, her eyes were closed. Her braid tumbled down and swung wide, darting, probing, as if with a mind of its own. When she stopped in a swirl of stars, it coiled around her neck.

"This is an old place," she said, as if to herself, "full of deep power. This keep is built on the ruins of a Merikit hill fort, as is Wilden, as are all our strongholds up and down the Riverland. Trinity knows on what the Merikit built except that it was . . . no, is . . . strong. But sleeping. Muffled. The House Knorth is still reeling. You almost shattered it tonight, Highlord, all by yourself, and so nearly brought down the bounds between the worlds but there are so many Kencyr dead here, still on guard. These banners . . . they must be destroyed."

She was facing Ganth and the oldest, eastern wall where the torches flared. Between them hung the ancient dead, rank on serried rank.

Gerraint made a choking sound. All the names that he had learned year after year at his father's side, all the Autumn's Eves since that he had chanted them himself, honoring the dead, keeping whole the fabric of his house . . .

"Well?" Rawneth was enjoying this. "Will you let your son molder with these other lost souls? Will you give him to the pyre?"

"No." He rubbed his left arm as if it hurt and shivered. "No!" With a sob, he threw himself at the wall, clutched a banner, and ripped it down, crying, "For my son! For my son!"

Behind it was another and another. Many disintegrated at a touch, their woof of old cloth hanging in rotten tufts on the rougher warp threads. Cords snapped. Faces distorted in silent shrieks and slumped down in a cloud of dust. As each fell, the Highlord sobbed out its name.

Ganth huddled beneath this storm of destruction, too weak to escape. His heart fought in his chest. Fragments of burial cloth clung to the cold sweat on his face. He gagged, tasting, breathing the dead.

Through the billowing dust, he saw Rawneth standing by the bier. She was softly clapping her hands in delight.

"Go down, go down, old house," she crooned. "Fall to ruin—go!—so that others may rise."

Behind her stood the one who had come with her in the guise of servant and spy. She couldn't see his face, but Ganth did. It was twitching from one cast of features to another, over and over, with each name that Gerraint cried, with each falling banner. Cruel as the portraits often were, the caricatures mirrored on that shifting face were obscene in their gleeful malice. What in Perimal's name had Rawneth brought into the heart of the Knorth? Did she even know herself? A creature out of legend, out of childhood nightmare, one of Gerridon's fallen, a darkling changer . . .

"Gran!" Ganth cried, and hid his face from it in the crook of his arm, "Gran, help!"

For a moment, he saw her tiny form sitting hunched on her bed, head in hands, supported by Aerulan. She seemed to hear, tried to rise, but fell back. "Oh, my strength is spent! I am too old. Child, fight him! Feel your anger. Draw power from it, as I do!"

But his heart was clawing at his chest like a trapped animal and he . . . couldn't . . . breathe . . .

Harsh panting echoed his own. Gerraint stood motionless in front of him, gripping the banner that hung over Ganth's head. The changer had raised his own hands and was cowering behind them in mock terror. Ganth knew suddenly beneath which tapestry he had taken shelter.

Gerraint braced himself and jerked downward. There was a tearing sound. Rawneth stared. So did the changer, with lowered hands and a blank countenance probably as close to his own as he still possessed. The banner fell, folding on top of Ganth as if bending over him. A terrible face rushed toward his. Gerraint had wrenched down those concealing fingers, tearing them clean out of the tapestry. Beneath were empty sockets streaming with blood: she had clawed out her own eyes.

Power and madness . . .

Ganth tried to thrust the banner away, but it clung, its threads wrapped tightly around him. The stench of moldering cloth half-choked him. He could feel the weight and dying writhe of the body that they had clothed—Trinity, dead how many centuries?

Madness and . . .

"Let me not see, "keened a threadbare voice in his ear, in his mind. "Let me not see. Oh, Jamethiel!"

Ganth gasped for air, struggling to free himself. His thoughts swirled like birds flung up into a storm-torn sky, the dark earth reeling under their wings. Death was nothing, or should be. The pyre freed the soul from its cage of flesh. To be trapped, while even a bone remained unburnt . . . horrible, horrible.

But what of blood? Sweet Trinity, how many here had died violent deaths and still carried the stains of their passing on their banners, long after they themselves were nothing but ashes on the wind? This lady whose name he didn't even know . . .

"Oh, Dream-weaver! Why did you do it?"

. . . how long had she hung here in agony and mute despair?

His own mother, Telarien, had bled to death in childbirth. If he were to look into her eyes now . . .

"No." Ganth lurched to his feet, still trapped and blind in the other's death throes, her memories like bleeding wounds in his mind.

" 'Then went my lord Gerridon to his sister and consort, Jamethiel Dream- Weaver, and said, 'Dance out the souls of the faithful, that darkness may enter in. And she danced . . . ' Oh, sister-kin, let me not see! But I have seen. "

Ganth staggered into someone—Gerraint, he thought—but his own terror had already broken the Highlord's grip on his mind, and if he had hurt his father, he neither knew nor, for the moment, cared.

Then he fetched up against something else hard enough to double over it. Finally, he managed to claw the rotten shroud away from his face. He was leaning over the catafalque, over his brother's corpse. Greshan's lips parted as if to speak. What moved them, however, was only the white seethe of maggots that bred in his mouth.

"NO!"

Ganth shoved his brother away. The corpse fell off the other side of the bier, trailing flies, and hit the floor with a meaty thud. The pall, dislodged, slid down over him. From where he sprawled by the northern wall, Gerraint cried out in horror. Turning, Ganth tripped over the banner that had slid down to entangle his feet, and fell hard on something that knocked the breath out of him.

Looking up, dazed, he saw Rawneth laughing down at him: "Little man, I could watch you all night."

"Oh, sh-shutup!"

Someone must have opened the door, Ganth thought as he groped for the thing that had nearly broken his ribs. Certainly, there was a powerful draft, almost a wind, whipping his hair into his eyes. Thunder rumbled, muffled to a tremor in the stones. Something above fell with a clatter. Banners rustled uneasily as air rushed down the spiral stairs at each corner of the lower hall. Maybe the keep's roof had blown off. Maybe the old walls would tumble in on them all. Best, perhaps, if they did.

"A dying, failed house" his father had said, and what had Rawneth chanted? "Fall to ruin . . . go!"

Something jerked at Ganth's foot. He looked down to see threads wrapped around his ankle like fingers, clutching. The wind was tugging at the tapestry. That was all. Then a face lifted out of the tangle of flying cords, eyes ragged bleeding holes, blanched lips mouthing words he tried not to hear:

"My soul and honor I ransomed with my eyes. I have seen, I have seen, but oh, kinsman, let me not fall!"

His hand closed on Kin-Slayer's hilt. He wrenched free the blade and hacked at that terrible face, at those desperate, clutching fingers. "Filthy Shanir, let go of me!"

She . . . it . . . the banner tumbled away, driven by the wind toward the guttering torches and between them, through a stone wall that was no longer there.

A vast space opened up beyond, and the wind poured through into it as if into a gaping mouth, fringed with unraveling banners. Ganth stared. This was hardly what he had meant when he had wished that the keep would fall in on them all. Instead, it seemed to have opened outward—into what? The flaring torches dazzled his eyes. He regained his feet, holding Kin-Slayer.

"Did you expect this?" he demanded of Rawneth.

She shook her head, staring. "No. Oh, no."

The void drew him. He moved toward it, shielding his eyes from the torchlight. The wind faltered, then turned, sluggishly, to breathe in his face: Haaahhh . . . It stank of old, old death, of ancient sickness and despair. Aaaahhh . . . a slow, deep inhalation, as of a sleeping monster, and the banners clung, shivering, to the keep walls. Haaahhh . . .

At first, it was like looking into deep, black water, a darkness thick enough to move with its own slow respiration. Then Ganth began to make out a floor, dark marble shot with glowing veins of green that seemed, faintly, to pulse. It stretched far, far back to a wall of still, white faces. Like the chamber in which he stood, the monstrous hall beyond was lined with death banners, but thousands upon thousands of them, a mighty host of the dead, watching.

Under their eyes, two figures revolved around each other, the one in black only visible when it eclipsed the one clad in white. They appeared to be . . . dancing.

Ganth edged closer to the wall that wasn't there, drawn by that second figure. He was almost sure that it was a woman.

Let me not see . . .

Something brushed against his face. Jumping back, startled, he saw what he had previously been looking straight through: the merest wraith of a banner stretched across the void's mouth. Like flies caught in a long abandoned web, old blood held tufts of rotting cloth to frayed threads. The whole shivered and seemed to gather itself. For a moment, Ganth looked into the ghost of a face known to him only from legend.

"G-glendar?" he stammered.

Question answered question, in a wisp of breath: "Have you seen?" The specter shuddered. "I have seen. " And it fell to dust.

"Rise up, High lord of the Kencyrath," the Arrin-ken had said to Gerridon's younger brother on that terrible night—Glendar, whom his family had counted as worthless, who had been taught to think of himself as little better. "Your brother has forfeited all. Flee, man, flee, and we will follow." And so he fled into the new world. Barriers he raised, and his people consecrated them . . .

But those people were gone, their banners torn down by a grief-mad father, and the way that they had guarded in life, in death, lay open. Huddled against the northern wall, Gerraint hid his face in his hands and wept at what he had done.

The changer laughed. "Ah, Glendar. Who will remember you now, you who could have lived forever? Knorth, you should rejoice. See? There in the shadows walks your own true lord and master. The Arrin-ken can't change that, not in three millennia, not in a thousand."

As Rawneth turned on him, his face immediately reassumed the aspect it had worn in the courtyard, the only one, apparently, that she knew. She slapped him, hard. "My spy. My creature. Who are you to say such things?"

The blow twisted his smile, and his eyes glittered before he cast them down in mock abasement. "Why, mistress, how could I be your . . . creature and not know your mind? Have I said anything that you have not already considered? Then consider this also: to whom do you owe loyalty? Where does your honor lie?"

Ganth backed away, toward his father. He felt the other's words twist like a knife in his soul. What if Glendar and all who had followed him were the truly fallen, for having abandoned their rightful lord? Where lay honor then? Perhaps the emptiness he had always felt came from living a lie.

The darkling eyed him askance. Little man. Hollow-heart. My master could make you whole.

Rawneth drew herself up. "Change is coming, and we Kencyr must change or perish. My honor follows my interest. What can this shadow lord do for me?"

"Ask, and see."

She laughed, but behind the mask her black eyes shifted to the beckoning darkness and she bit her lip. She would kill the man who played her for a fool, but if this offer was real . . . She approached the breach, swaying willow-supple. Her voice, mock coy at first, sharpened with an ambition as keen as hunger, as strong as madness:

"Master, master, will you grant me my heart's desire? Will you raise the dead to love me? Will you give me an heir to power?"

A long pause. The darkness breathed in . . . and out, in . . . and out. Ganth swayed, dizzy, unconsciously trying to match that vast respiration. Then, out of the shadows, a voice spoke. It was slow, deep, and distorted as if heard under water. Ganth couldn't distinguish the words, but Rawneth listened, rigid, her mouth partly open.

"Yes," she breathed. "Oh, yes!"

Gerraint made an inarticulate sound and struggled to rise. Ganth put a hand on his father's shoulder to restrain him. They both stared at Greshan as he stood in dusty black beside his bier, smiling.

Rawneth gave a crack of laughter edged with hysteria. To stifle it, she jammed her knuckles into her mouth and bit them until they bled. Then she glided toward the man whom she had chosen as her mate. Her hair unbraided by itself as she went and floated up as if she were descending into deep water. They began to circle each other, two figures of darkness, hands down at first, then weaving in the kantirs of the Senetha, almost but not quite touching. Skin tingled with the nearness. Breath wove with breath on flushed lips. Ambition was there, but also thwarted lust sharper than famine, so that even Ganth ached with it where he stood, watching.

"I will have my will," murmured the Randir, "now and forever. It has been promised to me." And she gave Greshan her bloody hand to kiss.

Gerraint tried again to rise. Again, Ganth pressed him down, not taking his eyes off the two by the bier.

Greshan looked at him askance and raised an eyebrow. What, will you allow your brother to be blood-bound by your mortal foe? He gripped Rawneth's hand so that her bones ground together. She shuddered in luxurious pain.

"Here?" he said, with a glance at the bier.

"No. I have a more . . . fitting place in mind. Come with me, my love, my consort. Come to Kinzi's precious Moon Garden, and let her watch."

"Go on ahead, my lover, my mate. I will join you there."

"Soon, then."

They kissed as if they would devour each other, and parted.

"Remember your word, Highlord," she said over her shoulder, "if that still counts. My son will be your true heir." With that, she departed in a swirl of her starry skirt.

Gerraint beat his fist against the floor. The emerald signet cracked stone. "Why didn't you stop them?" he cried at Ganth. "He is confused, seduced by that . . . that . . . but you—you were always weak and jealous. Always! And so you stood aside. Greshan, my son . . . "

"He isn't G-greshan," said Ganth. "Forget the face. Look at the clothes."

The changer grinned, his features shifting almost at random. He pulled up his hood to over-shadow them.

"So I fooled you too, old man, but not you, boy. And you did nothing. You must truly hate that woman. Ah, but she is clever. I told my master that if I brought her here, now, she would find her way to him. Darkness seeks its own level."

"Then seek yours." Ganth stood between the changer and his father. "In the shadows or in the garden, I don't care. Just g-go—"

The changer eyed the sword in his hand. "That blade and I will meet someday, but not tonight. As for going . . . " He craned around Ganth to address Gerraint. "Do you really want that, old man, with our business unfinished?" He stepped back and flipped aside a corner of the pall. The flies that had gathered, thwarted, on the cloth, rose in a swarm and settled again on Greshan's sprawling corpse. "He isn't getting any fresher, you know."

"Oh, for Trinity's s-sake," said Ganth. "If you won't call a priest, father, I will. Here. I'll s-start the damned pyre myself."

Stepping to the wall, he took down one of the torches. Before he could turn, however, something smashed into the back of his head. Stunned and bleeding on the floor, he looked up to see Gerraint standing over him with a fragment of paving stone in his hand.

"F-father!"

"Greshan is my son. I have no other." He turned, panting, to the changer. "I've come this far, broken oaths and betrayed my house—all for its own sake, I swear! Do you swear your lord can do this thing?"

"Gerridon is your lord too, old man, whatever the Arrin-ken say. Ask, and see."

Gerraint made a choking sound, then lurched around to face that breach into eternal night.

"Master, master!" he cried. "Will you grant me my heart's desire? Will you restore my son to me?"

Ganth struggled up on an elbow. His head was splitting and his vision blurred, or perhaps the latter came from trying to focus on that vast, shadowy hall beyond the keep's chamber. The void breathed in . . . and out, in . . . and out. Then it spoke, in the distorted rumble of a voice in an empty room, buried fathoms deep.

Ganth was vaguely aware of the dark figure who had come almost to the threshold. Like his servant, he was cowled and muffled, but somehow gave the impression of a leanness bordering on famine. That, Ganth dimly supposed, was Gerridon, the Master of Knorth, who had betrayed all for this meager, immortal life. So many death banners, rank on rank . . . had he devoured all his followers, to come to this? His hall, Perimal Darkling itself, surrounded him like the belly of a beast that has swallowed everything, even itself, and still hungers for more.

But it was not at Gerridon that Ganth looked. Behind him, in the middle of that cold hall, Jamethiel Dream-Weaver danced. A slim, graceful figure in white with flowing black hair, she seemed untouched by shadow or age, innocent beyond evil, beautiful enough to stop the heart.

Wraiths danced with her, tattered souls shivering in the threads of their death banners, torn loose from the keep and swept in this maw of darkness. There was Glendar, hardly a wisp. With a sigh, he melted into his sister's white arms and was gone. One by one, the others followed, their empty threads tumbling to the cold, dark floor. Only a ragged specter with bloody eyes remained. She and the Dream-Weaver circled each other, one dance mirroring the other in water-flowing kantirs, drawing ever closer.

" . . . sisterkin . . . "

One, or both, breathed that word, and they came together. Jamethiel stroked the other's wild hair, murmuring words Ganth could not hear, as hard as he tried. Then, very gently, she kissed those ruined eyes. With a shudder, the gaunt ghost folded into the Dream-Weaver's embrace and gave up her tortured soul, lip to lip.

Ganth shivered.

"Beware," his grandmother had said. "We are a passionate house, and not always wise."

But Kinzi hadn't grown up starved for acceptance, for any scrap of love, so he would not accept her judgment. At last the emptiness within him had a shape, now and forever, that only one being could fill. He would die for the Dream-Weaver. He would kill. He would foreswear any oath he had ever sworn, if only she would look at him. And she did, dreamily, with the smallest of smiles. Silver eyes, mirrors to trap the soul—was he reflected in them?

Mistress, mistress, will you grant me my heart's desire? Will you leave the dead to love me?

Too late. The dance turned her and her gaze slid away. What did she see now? It didn't matter. He had seen her.

His father was speaking. "That is your price? A contract for a pure-bred Knorth lady?"

Ganth scrambled to remember what he must have half-heard. What lady? Not Rawneth; she was Randir. Not the Dream-Weaver, surely, unless . . . unless . . . His heart leaped. A contract with whom?

His father sounded equally bewildered.

"But, Master, you already have a consort." He and Ganth both looked at the pale shimmer where Jamethiel danced, the opaque air a halo around her. She bent, graceful beyond a lover's dream, to gather up the tangled threads of the dead. The darkness rumbled. "Oh," said Gerraint, blankly. "You want a child, a . . . daughter? But why?"

The cowled head turned as the Dream-Weaver drifted toward him. Absently, smiling, she kissed him, and the ghost of souls glimmered from her lips to his within the hood's shadow. He reached out as if to return her caress, but stopped himself. Her hair slid through his fingers like black silken water as she turned and drifted away. His hand clenched and fell.

"Such power comes at a cost," said the changer. He smiled crookedly at Ganth, as if he had read the young man's heart. "She is already dangerous to touch. Soon it will be worse."

"I don't believe you," said Ganth.

The smile became a grimace. "Of course you don't."

Gerraint was frowning. "We are so few, and fewer still of our women are free to make new contracts." He crossed his arms, hugging himself. It was both a sign of pain, for his gray face shone with sweat, and his unconscious gesture when he meant to shave the truth. "However, there is my daughter Tieri . . . "

"Who is only a year old!" Ganth burst out. "You haven't even asked to s-see her since Mother died. Do you really hate the child that much?"

"What is she compared to my son? What is any female but a potential asset to her house?"

The shadows spoke.

"Age doesn't matter," translated the changer. "Only bloodlines. There are rooms in the Master's House where time barely crawls. He will retreat into one of them and await his . . . pleasure. As for the Mistress, she will do his bidding, as she does now."

Dancing, humming to herself, the Dream-Weaver wove the threads of the death banners into a new fabric picked out with flecks of ancient blood. The flecks were words; the whole, a document that she presented to her lord.

Ganth floundered to his feet, using Kin-Slayer as a crutch. From the throbbing in his head, he wondered if Gerraint really had cracked his skull. He knew beyond question that this contract would be his sister's death, but Gerraint had already reached into the shadows to seal it with his emerald ring.

"How cold!" he murmured, withdrawing his hand. "My fingers are numb."

They were worse than that. As Gerraint stared, blanched skin split open across his knuckles and the meager flesh beneath drew back on tendon and bone. Then the bones themselves began to crumble. Ganth caught the signet ring as it fell and threw an arm around his father to steady him. Cold rage unfolded in his mind like black wings spreading. He could feel them flex.

"Bastard," he said to the changer. "You knew this would happen."

"No. How the shadows enter each man's soul is his own affair."

"Nonetheless, I will kill you someday, darkling."

"Perhaps, unless I kill you first. Such dear enemies should know each other's names. Mine is Keral." He stood by the door, again wearing Greshan's face, and bowed. "I go now to make a lady happy—for a time. Alas for the greed of a woman and the grief of a man, that you should come to this! Farewell, Ganth Grayling."

Then he stepped out into the boisterous night. The door scraped shut after him, cutting short the startled exclamation of the Kendar captain still on guard outside, locking.

Gerraint swayed, clutching his arm. "So cold," he moaned.

It was cold. Ganth looked down. Thick, murky air was flowing out of Perimal Darkling, close to the floor. Haaaahhhhh . . . breathed the darkness, exhaling. Ganth drew his father back.

They retreated slowly almost to the western wall, trailing chalky dust on the floor. Gerraint began to stumble with shock. His hand had crumbled entirely away, and the flesh of his forearm was withering fast. Ganth held him insecurely in the circle of an arm, his own right hand clutching the signet ring; his left, Kin-Slayer's hilt.

Thick air settled around the bier, sluggishly rose, and piled up over it. Torchlight flared through sullen, slowly writhing coils of shadow. Shapes moved within them, crawling over and under each other, over and under, like half-digested souls or lovers impossibly entwined. One had no eyes. Its mouth gaped as if, silently, to scream.

Aaaaaahhh . . . breathed the darkness, inhaling, and sucked the clotted air back into its maw. Firelight flared—on a naked stonewall. The gate had closed.

A scraping sound came from the far side of the bier, then a heavy grunt. A hand rose and fumbled at the bier's edge. A figure clad in gilded leather dragged itself upright. It hawked, spat out a mouthful of maggots, and slowly turned. Greshan squinted at his father and brother with death-clouded eyes.

" 'm hungry," he muttered, chewing and swallowing.

Gerraint had cried out with joy at his son's first movement and tried, weakly, to break away from Ganth. "Your welcome feast awaits. Oh, my dear son, won't you come with me into the hall of the living to eat?"

" 'm hungry," said Greshan again, thickly, swaying. There was a terrible stench as he voided the gas of decay from both ends and somewhere in between, " 's better, 's of bitches at Tentir. Challenged me. Tricked me. Hurt me. Thought I was dead. Joke's on them, eh? All the time in t'world to make 'm pay when I am highlord. All t' time. I will give 'm blood to drink, an' more, an' more, an' more . . . "

He sniffed and shambled forward. "I smell death on you, father. Time you were gone. Ring and sword. Give me. My time, 'm hungry. Dear, dear father, feed me . . . "

Gerraint seemed to melt out of his son's grasp. Perhaps he had fainted. Ganth, perforce, let him slide down to rest against the wall and turned to face his brother.

Greshan gave a thick gurgle and hawked up more maggots. "Well, well, well. Dear little G-g-g-g-ganoid. M' childhood playmate. Remember what fun we used t' have? Our midnight games? You din't enjoy them much—that was half the fun—but I did. An' then you tried to tell father!" He grinned through broken teeth. "Oh, that was funny! Remember?"

"I remember," said Ganth, and he did. Everything.

The slow walk up the stairs to Greshan's quarters, knowing that every step was watched by fellow cadets no longer even feigning sleep. The wash of heat and light rolling over him as the door opened, the closeness as it shut behind him . . .

At first, dazzled, he could see nothing but the fire roaring in the grate. The room was hot and airless, sour with the stench of sweat and spilt wine. Roane's servant shoved him from behind. He stumbled forward, tripping over a welter of beautiful, filthy clothes, the soiled, spoiled wealth of his house. Someone laughed. Now he could make out two figures sitting on either side of the hearth, watching, waiting.

"Well, well, well. Dear little Gangrene." Greshan's voice slurred only a bit, a sign that he was very drunk but nowhere near passing out. "All grown up and come to Tentir to play soldier. So you still like games. Shall we show my dear friend Roane how we used to play? Now, be a good boy and take off your clothes."

Slowly, with numb fingers, Ganth removed his tunic. They laughed at his lean build. Not much muscle there. No wonder he was doing so poorly at Tentir.

He wanted to say, "How can I do well, when you always watch me?" but he couldn't speak.

"Now the pants," said Greshan.

When he didn't move, his arms were seized. Roane had two servants with him, not just one. Roane also had a knife. A long, narrow one, double-edged. Ganth saw it as the Randir stood and sauntered toward him, turning it over in his hands so that the firelight played off of it.

Now Roane was behind him. "Little boys should do as they are told," he said.

The knife's cold kiss made Ganth flinch as it slid down first one leg, then the other, cutting away his clothes.

Greshan leaned forward, licking his lips.

"Your house is soft, rotting from within," Roane breathed in Ganth's ear, too low for the Lordan to hear. "We will mold it to our liking until it falls apart in our hands. Now be a good little Knorth, like your drunken lout of a brother, and submit."

Ganth stared into the heart of the fire, willing himself far away as he had as a child so that whatever happened, happened to someone else.

But he was no longer a child, and this was wrong.

Sudden pain, and sudden rage—black, cold, powerful.

His hands twisted in the others' grasps and gripped them in turn. The next moment, he had sent one floundering into his brother and the other headfirst into the fire. The knife's point skittered across his hip. He grabbed Roane's wrist, pulled, and bent. They were on the floor now, he on top, the knife between them. Firelight shifted across their faces as the servant lurched out of the fireplace and staggered, wrapped in flames, about the room, futilely pursued by his mate.

Ganth looked down into the Randir's astonished eyes. "Let's see how you like it," he said softly.

Then he drove the blade into the other's stomach and leaned on it. Down it went, through muscle walls, scrapping against the spine, into the floor. There, slowly, Ganth screwed it home.

Someone had been hammering for some time on the door. Now the lock broke and it burst open. Sere stood on the threshold, dark shapes behind him.

Ganth ignored them. He saw only his brother, staring at him slack-jawed with amazement, beginning to back away. Ganth rose and followed him. Somehow, he had acquired a sword, and there was an emerald signet ring on his finger. Greshan held out hands as blotched and swollen as bad sausages. He backed into the catafalque, knocking it over.

"No, no . . . brother, dear brother, I'm y'r lord. I want to live . . . "

"But you are dead. You died a long, long time ago."

The randon in the doorway reached behind him and hauled forward someone in a priest's robe. "Say it," he demanded, giving the man a shake that rattled his teeth. "Say it now."

The priest gulped, and spoke the pyric rune.

Greshan burst into flame. So did many of the banners lining the walls that had been woven of bloodied thread. More kindled as the Lordan blundered into them. Ganth, following, hewed him down. Kin-Slayer felt light in his hand, eager. He struck again and again, to kill memories of weakness and shame, to obliterate them forever so that, finally, he might live.

The randon called him back to his father's side.

Gerraint sprawled against the wall. His right sleeve and the whole right side of his coat hung limp, empty. Half of his face began to sink and wither on the bone even as they watched. He reached out and gripped Ganth. "Tell me it isn't true," he said with difficulty, able to use only the left side of his mouth. "Tell me, as children, he didn't . . . didn't . . . "

Ganth considered the child he had been, soft and weak, who might have forgiven this dying man and found a way to show him mercy. That was the boy who had stumbled out of Tentir that autumn night wearing clothes picked at random from his brother's filthy floor, leaving all his hopes in tatters behind him, forswearing forever (or so he had thought) the black rage that had made him do such terrible things.

"Another god-cursed Knorth berserker . . . "

No. Anger was power, nothing more, nothing less.

The Knorth Matriarch had known that when she bade him draw on it, and so he had, and so he would continue to do, for now he needed strength as never before.

"Father," he said evenly, meeting that desperate gaze, "I didn't lie."

Gerraint's hand fell away from his son's sleeve and he turned his ruined face to the wall. His clothes began to smolder.

"Leave him," said Ganth to the randon as the latter bent pick him up. "His pyre is laid and he is ready for it. Let him burn with his son."

Sere looked sharply at him, then inclined his head in submission and rose. "Yes, Highlord."

On the threshold, Ganth looked back. Gerraint's body was already burning. So was the banner above it, Telarien's sweet features melting into flame. He tried to carry his mother's image out into the night, where his new household anxiously waited, but only one face went with him.

Let me not see . . . but he had seen.

Secretive and smiling, Jamethiel danced on and on, weaving dreams and desire in a corner of his soul.

[A cloth letter, unfinished, undelivered, found in the quarters of the Knorth Matriarch Kinzi Keen-Eyed on the night that Shadow Assassins massacred the Knorth ladies]

. . . and so, dear sisterkin, I will spend some time stitching this note to you while I wait for my grandson Ganth and the others to return from the hunt, being too on edge to do anything else.

How the Tishooo howls! Does it also shake your tower in the Women's Halls?

Odd, to think of you so close, and yet so far. We could have been together tonight if not for this stupid hunt—for a rathorn, no less. I asked Ganth not to go, but you know how restless and unmanageable he has been of late. I tell him he should take a consort, but he only gives that bitter laugh of his. He has someone in mind, though, I swear, but whom? Oh, my dear, I used to know him so well. It hurts me to see him turned so hard, as if afraid to show any softness, and as for his temper . . . ! If only he would recognize its Shanir source, I could help him master it. Instead, I fear that some day it will master him.

Speaking of berserker tendencies, yes, you should send your granddaughter-kin Brenwyr to me. You have done wonders with her since her mother's death, but an untrained Shanir maledight is so very, very dangerous. Worse, I fear that she and Aerulan have quarreled—over little Tieri! Sometimes I wonder if we of the Women's World are any wiser than our squabbling men-folk, but at least we rarely draw blood.

And so, circling, I near the heart of my unease.

Can it really be ten years since Gerraint died? You have been impatient with me for not having told you more about that night. In truth, Ganth has told me virtually nothing of what happened in the death banner hall before so much of it burned, and you have laughed at rumors that Greshan was seen walking the halls of Gothregor when he was five days dead.

Well, I saw him too. In my precious Moon Garden. With that bitch of Wilden, Rawneth. She led him in by the secret door behind the tapestry and there, under my very window, made love to him.

Except it wasn't Greshan.

I knew that the moment I saw him, and I didn't warn her. Oh, Adiraina, I was tired and angry, and so I let her damn herself. Then he changed—into whom, I don't know. I couldn't see his face, but Rawneth did. She gaped like a trout, then burst out laughing, half in hysteria, half, I swear, in triumph. What face could he have shown her to cause that?

I have since bricked up my window, but that question continues to haunt me. Especially now.

It has been three months since Lord Randir died and four since the Randir Lordan disappeared. My spies tell me that Rawneth contracted the Shadow Guild to assassinate him—much luck they seem to have had against a randon weapons-master, as strange as he may be in other respects. Now she insists that Ganth confirm her own son, Kenan, as the new lord of Wilden.

And here we come to the heart of the matter.

Rawneth went back to Wilden that same night, contracted with a highborn of her own house, and some nine months gave birth to Kenan. But who is Kenan's father—the Randir noble or the thing in the garden? Without knowing, how can I advise Ganth to accept or reject his claim? And so I have summoned Rawneth and her son to Gothregor while you are also here, since your Shanir talent lies in determining bloodlines at a touch. You will tell me, dear heart, and then I will know how to act. I must admit, I do hope our dear Rawneth has mated with a monster.

But if so, why did she laugh so triumphantly?

How the wind howls! Now something has fallen over below. I hear many feet on the stair. Perhaps it is Ganth, come home at last . . .

"Tell me a story," said one of the twins.

Anar clawed his way out of the past like someone scrambling up a rubble-strewn slope. Here were bits of his childhood at the scrollsmen's college, where he had been happy. Hard to remember, now, how that had felt. Here were the ruins of a beautiful, embroidered coat—Greshan's, probably, that cruel swine. Anar had often wondered about m'lord's childhood with such a brother, how much it might have influenced the man he had become. Here was a scrap of memory, charred at the edges, that still seared: a pyre and at its heart, a small, indomitable woman wrapped in flame.

Oh, Kinzi, and all the women of my house, burning, burning, the taste of their ashes bitter on my lips . . .

He scrubbed a dirty hand across his mouth and blinked up at the child on the hillcrest above him, dark against the slow, opalescent seethe of the Barrier.

Was it the boy or the girl? When not together, they were hard to tell apart. The same wild black hair, cropped short; the same eyes, storm-gray or silver as light or mood caught them; at seven years old even still much the same build, thin and wiry . . . there was even some confusion as to which had been born first. But one had fingernails and the other, this one, usually hid her hands because she didn't.

The girl Jame perched above the keep's straggly kitchen garden, watching him, waiting.

"A story," she prompted. "Something true."

"Not all stories are," he said absently. "You ask the singers about their precious Lawful Lie." Not that she could: the only singer to go into exile with his lord had been among the first to die.

He stared at the roil behind her of the Barrier that separated this world from the next. Beyond it, shadow folding into shadow, Perimal Darkling waited. That was true enough, ancestors preserve them. So was the Master's House, that nightmare looming out of a fallen past. He could almost distinguish the crooked lines of its many roofs, shifting in the shadows of countless moonless nights, its windows without number opening to the soulless dark within.

Trinity, but it was close. Only once before had it been closer. The garrison had been some three years into its exile then, long enough to see that it would only end in death. The sooner the better, they had thought, and so again followed their lord headlong into hopeless battle, this time against primordial darkness itself.

Death, at last, with honor . . .

Anar shuddered, remembering the slow churn of mist under that cliff of shadow that had confounded and dragged them apart. Only he and two score others had stumbled out. Some, gaunt with hunger, mad with thirst, said that they had been trapped for days, for weeks, in that murky limbo. Some only stared with hollow eyes, mouthing the same words over and over again:

" 'm hungry, 'm hungry . . . "

That had been the garrison's first experience with the haunts that gave this accursed land its name.

It was also when they discovered that their priest, Ishtier, had run off, taking his lord's Kendar mistress and his own priestly powers with him, just when they had most needed a pyric rune to deal with their own walking dead.

Of them all, only the Gray Lord had penetrated the shadows and come at last to the Master's Hall, or so Anar guessed. Where else could he have found that beautiful, nameless lady whom he had brought out with him to grace his bed and bear these children, brother and sister, with so much of her strange magic in the silver shadow of their eyes?

Words whispered in his mind, silken fingers meant to tease out memory like a snarl:

Let no one see . . .

See what? Of whom had he been thinking?

Anar floundered for a moment before the subtle sinews of his patchwork priest-craft steadied him.

He had come to this twisting of the way before—every time, in fact, that he thought or spoke of the twins' mother. Others looked puzzled if he mentioned her, as if she were a fading dream, half or wholly forgotten, a thread of sweet song, a movement of heart-breaking grace limned in moonlight, a fleeting glimpse of glamour.

Let no one see . . .

Only the children remembered, and the randon Winter, who had her own reasons, and the Gray Lord.

Anar felt his breath catch. Somehow, he had forgotten: there was the House, looming, and Lord Grayling had gone again, alone, to storm it, to reclaim the fey bride whom he had somehow lost or perhaps just misplaced. How long had he been gone? Days? Weeks? If he didn't return, what would happen to his people, who had gone into this bitter exile for his sake? Did he even care?

Pushing aside the thought, the scrollsman pulled up something that should have been a carrot. It was the right color, at least, but its tip twitched like a rat's nose and its white rootlets stung his hand. Anar snapped the root in two, ignoring its thin, piping shriek.

"Dare you to dig up a potato," said the child. "All those eyes, blinking. Ugh."

"At least they don't scream," said Anar.

He blinked, remembering the pile of limp vegetables that already lay in the keep's kitchen, some of them still mewling weakly and trying to crawl away. Since m'lord had stormed out, no one had felt like cooking or eating. What a waste. It had taken long, hard work to make the soil of the Haunted Lands yield even this sorry crop. Only the collective will of the garrison continued to make it possible—that, and Anar's own makeshift attempts at priest-craft which, he knew, were slowly unraveling his mind.

"I don't think you're mad," said the child, judiciously, "or at least not as mad as Tigon. He keeps trying to eat his own toes."

Sweet Trinity, he must have been thinking out loud again.

"Yes," said the child, "you are, off and on. What does 'fey' mean?"

Don't think. Talk.

"A story," he gabbled. "You asked for a story."

But what story could he safely tell? M'lord had forbidden him even to teach these children their father's true name. Someday, he might inform his son and heir, Torisen, but never this fey, unwanted daughter, already too like her mother for comfort.

"That word again. 'Fey.' Is that why Father doesn't like me?"

Shut up and talk.

"Suppose," Anar said, desperately launching himself, "that there is a land where the animate and inanimate, the living and the dead, don't overlap."

"You can always tell them apart?"

"Yes. No. Most of the time. Suppose the lord of that land came home one day to find all the women of his family slaughtered."

"They didn't turn into haunts?"

"No. He had a priest speak the pyric rune and they all burned up. Crackle, crackle."

"Who killed them?"

"This lord had many enemies, but he thought he knew whom to blame and he set out to punish them."

Anar shivered, remembering the Highlord's rage as he turned from his grandmother Kinzi's pyre, his berserker madness that had infected them all.

"Did he make them pay?" asked Kinzi's great-granddaughter.

"No. He guessed wrong. I think. Anyway, there was a big fight and a lot of his own people got killed. After that, they didn't want him to lead them anymore, so they drove him away."

Why was he telling this of all stories? M'lord would kill him! Belatedly, Anar shoved half the carrot into his mouth to silence himself. The rootlets writhed and stung as he bit down.

Let me not speak . . .

"What happened to him? How does the story end?"

"I don't know." The words were slurred, his mouth already swelling. "So far, it hasn't."

The child waited to see if he would say anything more or, perhaps, fall over dead. When he did neither, only flapping a hand helplessly at her in dismissal, she jumped up and ran away.

THE HILLS of the Haunted Lands seemed to roll on forever, under a rolling sky. Jame ran down through the coarse, clinging grass and up, down and up, jumping off the crests, trying to fly.

From a rise, she saw the squat tower of the keep, dark against the Barrier except where the crystal dome over the lord's solar caught the evening light. The sun was going down to the west; to the east, a gibbous moon slowly climbed the sky. A fitful, sour wind from the north ruffled her hair and combed the grass over her toes.

Turning southward, Jame plunged down again; then, more slowly, she climbed. Beyond, she could hear Winter grunting instructions:

"Here. Aim. The foot, so. Your shoulders . . . turn them into the strike. Better."

Jame dropped to her stomach and wriggled up to the hilltop. Through a fringe of grass she watched as their former wet-nurse taught her brother a fire-leaping move of the Senethar.

Winter, a big, raw-boned Kendar, towered over her young student, holding a large hand higher and higher to make him extend his kick. Scowling with concentration, Tori pivoted and struck. His bare foot slapped against her palm.

"Good," she grunted, and hooked his other foot out from under him. "Not so good."

Tori had landed on his back without adequately breaking his fall. The rock-hard ground smacked the air out of him and for a moment he lay there gasping.

"Up," said Winter. "Again."

Jame watched, idly plucking stems of grass and letting them snake through her hair. They wriggled and tickled as they tried to take root in her scalp. She thought they camouflaged her nicely, until Winter turned her long, horse-face up toward her.

"Come down," she said; and then, to Tori, "Enough for today. Practice that."