EDITOR’S PREFACE

STORIESBreaking NewsCONTINUING SERIALS

Ounces Of Prevention

Burmashave

Schwarza Falls

Susan’s Story

Of Masters And Men

Murphy’s LawSuite For Four HandsFACT ARTICLES

Euterpe, Episode 3In Vitro Veritas: Glassmaking After The Ring Of FireIMAGES

Dyes And Mordants

What Replaces the SRG?

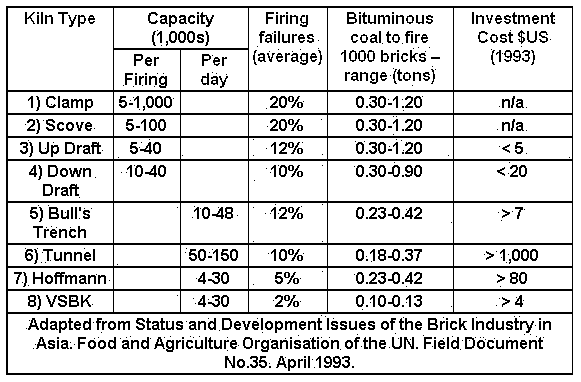

The Grantville Brickmaker’s Primer

SUBMISSIONS TO THE MAGAZINE

Grantville Gazette Volume V

Just what is going on around Grantville, these days?

Questions are being asked, rumors are flying . . .Tony Adducci is tearing his hair out, wondering if he and his inexperienced staff will be able to track down and bust the perps . . .

In Rome, a concerned mother wonders if deciding to send her talented daughter to Grantville didn’t get her a bit more than she bargained for . . .

Nikki Jo Prickett, who’s gone to the Republic of Essen, struggles to make a certain ambassador understand that antibiotics aren’t always the right answer . . .

What is all that secrecy over in Meiningen about, anyway?

Oops! There’s a bit of a shortage of laboratory glassware these days. Where are we going to find what we need to make more?

Just what did the Ring of Fire look like from the other side? Hermann Decker knows—he was there . . .

Then there’s the wicked Velma . . . How can she get away with that sort of rottenness?

The army needs another gun . . . which one will it be?

Will Franz ever play the violin again? And what is so attractive about Grantville, that it should attract so many musicians, anyway?

Is Maestro Carissimi’s immortal soul in danger because he hangs out with all those Protestants?

Will the brick industry ever get off the ground . . .

And just how do you get the color red from a bug . . .

These and other burning questions will be answered . . .

In Grantville Gazette, Volume 5 . . .

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

First electronic printing, September 2005

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020Printed in the United States of America

DOI: 1011250009

Copyright 2005 by Eric Flint

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

A Baen Books Original

Baen Publishing Enterprises

P.O. Box 1403

Riverdale, NY 10471

http://www.baen.comProduction by WebWrights, Newport, TN

Electronic version by WebWrights

http://www.webwrights.com

Well—hallelujah—we managed to get Volume 5 of the Gazette out pretty much on schedule, about four months after the publication of Volume 4. As I said in my preface to that issue, I’m hoping to be able to maintain a triannual publication schedule for the magazine. We should be able to do the same, I think, with Volumes 6 and 7. We’ve already got all the stories and articles assembled for Vol. 6, and most of the ones we’ll need for Vol. 7.

That said, most of the time involved in producing such a magazine is required by the editing and copy-editing process, which takes some time. Still, we should be able to get volume 6 out before the end of the year.

Some remarks on the contents of this volume:

As always, parsing the distinction between “regular stories” and “continuing serials” probably falls somewhere in the category of secularized medieval scholasticism. Just to name one example, Karen Bergstralh’s “Of Masters and Men” is essentially a sequel to her “One Man’s Junk,” published in the last volume. But since there is—yet, anyway—no indication that she’s going to be continuing this story, I chose not to put it in the category of continuing sequels.

Yes, you can argue the point. The fact remains that I’m the editor of the magazine and if say the number of angels who can dance on the head of a pin is 15,468,622, then—here, at least—15,468,622 it is.

Ultimately, this is probably a hopeless battle on my part for Literary Clarity. Hopeless, because as time goes on, it’s becoming clearer and clearer to me that the assessment I made of the Grantville Gazette in my preface to Volume 4 is indeed correct. The Gazette is, indubitably, that most lowly and despised of all literary sub-genres.

To wit, a soap opera.

Look, let’s face it. In the 1632 novels, you get—more or less—The Big Picture featuring the Stars of the Story. In the 1632 anthologies, you get basically more of the same, simply with a narrower and tighter focus and (often but not always) featuring a worthy character actor who gets his or her day to strut on the stage.

What do you get in the Gazette? All the shenanigans of everybody else, that’s what. The damn spear-carriers, run amok. Slice of life story piled onto family sagas—functional and dysfunctional alike—and all of it ladled over with a heavy scoop of personal melodrama.

I mean, honestly.

Who cares—just to name one example—if Karen Bergstralh’s woebegone blacksmith gets around the oppression of the guild-masters and starts setting up his own successful business? Who cares—to name another example—if the pimply-faced American teenager in Jay Robinson’s “Breaking News” wins the heart of the (hopefully not acne-ridden) teenage daughter of a downtime artist who is only remember by art connoisseurs?

(The mother, not the daughter—nobody except scholars remembers the daughter, for Pete’s sake, until Jay dragged her out of historical obscurity.)

Shall I go on? Who cares if Velma Hardesty’s daughters escape from the Horrible Mother’s clutches, in Goodlett and Huff’s “Susan Story”? Just to make it worse, from what I can tell about a dozen other writers seem to have become infatuated with Wicked Velma, and it looks like we’ll be getting a small cottage industry cropping up of “Velma Gets Her Just Desserts” stories.

Sigh. Not one of these stories deals with Ye Big Picture. Not one of them fails to wallow in the petty details of Joe or Dieter or Helen or Ursula’s angst-ridden existence.

Pure, unalloyed, soap opera, what it is.

Fortunately, before I start tearing my hair out over the Lit’rary Disgrace involved, my commercial instincts rally to the rescue. Because, while it is indeed true that soap opera gets no respect from the Illuminati, it’s...

Well.

Wildly popular.

So, I brace myself. No, more. I find a peculiar sort of glee in contemplating the fact that a universe I originally created in order to explore some of the alternate possibilities for The Big Issues—democracy, religious tolerance, that stuff—has expanded to include a veritable spaghetti bowl of personal stories that have absolutely no function or purpose than to examine the multitude of ways in which the unwashed masses get about their lives under the changing circumstances.

It’s a fitting full circle, I think. Let us not forget that, in the end, democracy is just a form of government—and the only purpose of government (legitimate one, anyway) is to enable the unwashed masses to get about their lives with a minimum of grief and anxiety. That way they can invent, discover, explore and wallow in their own hassles, instead of being saddled with somebody else’s.

So, again, we venture into the 1632 soap opera. Hankies can be found on the coffee table, I believe. Yes, I know the guys won’t need them. Shirt-sleeves will always do, in a pinch.

Eric Flint

August, 2005

An apprentice escorted Artemisia Gentileschi into the stifling studio. She was expected.

“Maestra Gentileschi, my dear, how pleasant to see you!” Gian Lorenzo Bernini stood in the middle of his studio. The young sculptor’s handsomeness was barely diminished by a layer of rock dust. Apprentices and journeymen worked busily on busts and other statuary.

“It is good to see you, Cavaliere,” Artemisia Gentileschi said.

“Enough of this ’cavaliere’ nonsense, Artemisia. We’ve known each other too long for such formalities.”

“And we’ve known each other too long for me to believe you didn’t know I was in Rome, Gian Lorenzo.”

Bernini laughed. “You always did have the measure of me. You are correct of course; I knew of your arrival almost instantly. Come, let’s sit on the balcony and talk. It will be more pleasant there.”

Bernini motioned to the apprentice who’d shown Artemisia into the studio. “You! Bring wine for Maestra Gentileschi and myself.” The young man scrambled to obey.

The two artists spent some time catching up. Gian Lorenzo Bernini was far more adept at making enemies than friends, but Artemisia Gentileschi was a friend. Though Bernini painted a little, it was working the stone that he loved, and Artemisia supposed that the main reason they got along was because the sculptor didn’t view her as a rival for commissions. They were also both second-generation artists, a relative rarity. When small talk and nostalgia had run its course, Bernini decided to get to the heart of the matter.

“What is it that brings you to me, Artemisia? Surely not merely to pass an afternoon in conversation, pleasant though that may be.”

Artemisia sipped her wine before answering. “I have come to seek your assistance in a matter, Gian Lorenzo.”

“Is it money? I keep telling you that miser Philip doesn’t pay you what you’re worth.”

“Money isn’t everything,” said Artemisia. This was an old argument between them. “There is no small amount of prestige to be had painting for His Most Christian Majesty. And he’s not nearly so jealous a patron as His Holiness.”

“Jealous Pope Urban may be, but he is generous. Extremely generous. If it is not money, then, what is it you need? And what makes you think I can help you and King Philip cannot?”

“You have heard of this new town in the Germanies? Grantville, I believe it is called.”

“It is called Grantville,” Bernini confirmed. “And it has been the subject of much talk in the papal court. Mostly rumors, and wild ones at that. Its inhabitants are proving most puzzling. They are allied with the Swede, yet by all accounts, there is a Catholic church in Grantville that flourishes alongside Protestant churches and even a synagogue. Its leaders have made no attempt to suppress the Church and even seem to tolerate the open presence of the Jesuits.”

“The father-general must be pleased,” Artemisia said. “However, it confirms what I have heard, that Grantville is a place of freedom and possibilities.”

“You seek to go there?”

“No. I want to send Prudentia there. Facts about Grantville are hard to come by, but it seems that women are not barred from advancement merely because they are women. It will be good for her development as a painter and as a person.”

“This, from the only female member of the Florentine Academy of Design?” Bernini’s feigned shock was intentionally theatrical.

Artemisia was not in a joking mood, not about this. “You know as well as I what I’ve had to go through. And you also know that Rome is a snake pit for an artist.”

“True enough,” said Bernini in a more serious tone. The sculptor didn’t even try to deny Artemisia’s statement. How could he deny it when he was the snake pit’s most poisonous viper?

“I believe I can do as you ask. In fact, there is a most suitable traveling companion for young Prudentia with plans to depart for Grantville very soon.”

“Thank you, Gian Lorenzo. I am in your debt.”

“Yes, you are. And don’t think I will let you forget it.”

James Byron “Jabe” McDougal was having a hard time concentrating on this week’s selection for the Grantville “Dinner and a Movie” club. It wasn’t because of the selection. Doctor Strangelove was one of his favorites. No, it was Prudentia Gentileschi that was the distraction. From Jabe’s point of view, practically everything about the fifteen-year-old shrieked: “out of your league!” She was beautiful—Jabe thought she was, anyway—she was smart, she was funny . . .

She was even famous. At least, her mother was famous, if you knew anything about art. Artemisia Gentileschi painted for cardinals, dukes, even kings.

Tonight’s meeting was at Stephanie Turski’s house. The group had grown out of an informal advisory committee brought together by Janice Ambler when Janice found herself programming director of the one and only working television station in the seventeenth century. The group still served an advisory function, but had evolved. As Janice firmed up programming hours and policies of the station—it had been christened WVOA-TV and the name had stuck—Dinner and a Movie became more of a group to watch and discuss films that didn’t have broad enough appeal to merit a showing on WVOA.

Membership was fluid but there was a steady core of regulars in addition to Janice and Stephanie: Amber Higham, Eric Hudson, Ev Beasley, and Lorelei Rawls were all film buffs, and Father Mazzare and Reverend Jones came when they had the time. Balthazar Abrabanel, fascinated by the medium, also came when his health permitted and his medical duties didn’t interfere; and Prudentia Gentileschi. Prudentia had been schooled in painting since she was old enough to hold a brush, and if her mother knew how well Prudentia could hold forth on the use of light and shadow in composing film shots, Artemisia would have been proud indeed. Her perspectives on this uniquely up-time art form were always surprising.

The discussion of Dr. Strangelove was winding down when the phone rang. Stephanie answered and handed the phone to Jabe. It was the duty officer at the barracks. Jabe was ordered to return as quickly as his feet could get him there.

“Sorry, everybody,” Jabe said. “I need to go.”

“I need to go as well,” said Prudentia, in her heavily accented English. “Signor Nobili does not like me to be out late.”

“I’ll take you there,” said Jabe. “You shouldn’t walk alone.”

Prudentia’s responding smile had an undertone that embarrassed Jabe a little. Mostly because he was quite sure she wasn’t fooled at all. In point of fact, Grantville’s streets were quite safe, even at night—and Prudentia knew it just as well as he did.

However . . . She didn’t seem to mind.

Prudentia’s arrival in Grantville had been overshadowed, first by Mazarini’s visit and then by the Croat raid and its aftermath. Artemisia Gentileschi wasn’t a household name in a town like Grantville, certainly, but Father Mazzare had known who she was. So had Balthazar Abrabanel. He had recalled some rumors that Prudentia’s grandfather Orazio had relocated to England from his native Rome, but if that was true Balthazar had never crossed paths with the man.

Before long, Prudentia Gentileschi was a minor celebrity—much to her embarrassment. Living arrangements were soon made, with Tino Nobili agreeing to provide lodging. Though Artemisia had wanted her daughter to be educated in Grantville, it was soon determined she already had an education which surpassed almost all Grantville’s down-time citizens, and more than a few up-timers as well. In the end, Prudentia became a part-time student, mostly taking courses she chose for herself, and assisted the art and art history teachers in Grantville. In return for the latter, she was given a modest stipend to supplement the money her mother had sent with her.

Jabe and Prudentia spent most of the walk to the Nobili home in awkward silence, or even more awkward small talk. Jabe knew he was caught in the painful limbo between friendship and romance. The worst of that limbo, of course, being the fact that he had no idea if Prudentia felt the same way—and had no better idea how he might try to find out.

Even with an up-time girl, Jabe would have been too shy to try for a goodnight kiss, unless the girl was practically waving flags at him. With a down-timer like Prudentia, he didn’t have a clue how he’d recognize a waving flag even if he saw one.

At the Nobilis’ door, they bid each other good night. Jabe spent the walk to the barracks alternately cursing himself for blowing his chance with Prudentia—if there’d been one at all—and wondering what was going on.

Mike Stearns imagined that he looked like hell. He felt even worse. He hadn’t gotten any sleep the night before and wasn’t counting on getting much tonight. Mike had walked from the radio shack to his rooms so many times the last few days he could have made the trip in his sleep.

It may yet come to that, Mike thought. He stood up and stretched, stepping away from the radio. The radio window for the evening was now closed, and Mike could do no more here tonight.

He called for his escort for the evening. “Pete! I’m ready to head back.”

Pete McDougal opened the door. “If you don’t mind me saying so, you look like nine kinds of rough,” he said.

“Ten kinds, Pete.”

For the first few moments, they walked in comfortable silence. The two had been fellow UMWA officials in their local before the Ring of Fire and had known each other a long time.

Mike shook his head. “Medals don’t seem like enough, Pete. I wish I could do more. If we were up-time these kids would have been all over TV. Dateline NBC, Sixty Minutes, the whole works.”

After hearing Pete’s response, Mike abruptly changed course, leaving Pete scrambling to keep up. “What a great idea! Let’s go get Frank out of bed.”

Mike had hoped to have Jesse Wood fly Frank Jackson back to Grantville the day before, but things hadn’t worked out quite that neatly. As Frank and Jesse touched down, the American general found himself, for once, a little grateful he was in the early modern world. At least, Frank thought, the thirty-minute news cycle was a thing of the past. Or future, depending on how you looked at it.

By now, it had been officially acknowledged that Eddie, Larry, Hans, and Swedish sailor Bjorn Svedberg had been killed in action at Wismar, but the situation in Magdeburg had not left time for the release of a detailed statement. Until now.

Frank found Henderson Coonce waiting for him at the airstrip, truck engine running. Coonce saluted, and they drove to the high school. Even if Frank had been vain enough to think his rank entitled him to a chauffeur with captain’s bars, Henderson put paid to that notion by complaining the whole way. By the time they pulled up to the high school, Frank was ready to recruit an entire regiment’s worth of press officers, just to shut Coonce up.

“If you don’t want to wait, Captain, I’ll ring when I’m done,” said Frank.

“I can wait,” said Coonce.

“I said you’d get your press officer.”

Coonce smiled. “I heard you, Frank. Why do you think your ass ain’t walking back?”

Military protocol in the new little United States still had a long way to go. Frank just shook his head and went into the school.

He found Janice Ambler and Jabe McDougal waiting for him. Jabe sprang to attention. Prudentia Gentileschi sat quietly in a corner, sketching something off of a television screen.

“At ease, Jabe. We’re not in the barracks.”

He went straight to the subject. “You still have all that video stuff you were doing after the Ring of Fire? That oral history project you were working on?”

“Sure, sir,” replied Jabe. My tape’s almost gone, though.“

“Have you got footage of Eddie and Larry? Hans?”

Jabe nodded.

“Good. Can you put something together? By noon tomorrow?”

Janice Ambler was starting to panic. It was ten minutes till noon and Jabe still hadn’t shown up. Janice’s mentor had worked at a TV station in the early days of live television and had told her often of what it took to play the live programming produced in New York for a west coast audience three hours behind. The shows were broadcast over phone lines, projected, and filmed with a kintescope. The film was rushed to the lab, developed, and rushed back to the studio by motorcycle courier. Janice wondered if her old friend had felt what she was feeling now—and, if so, how he had avoided getting ulcers.

Pacing in front of the high school’s front door, Janice heard Jabe before she saw him. A farmer driving his horse cart into Grantville had given him a ride. Prudentia Gentileschi was with him. Jabe handed Janice the tape. The tirade she’d been working up evaporated in a second as soon as she saw the young man; he’d obviously been working through the night.

“Sorry to cut it so close, Ms. Ambler. Had to make sure this one was as perfect as I could make it.”

“Jabe, no offense, but you look like hell. Hello, Prudentia.”

Prudentia inclined her head in acknowledgement. “What Jabe won’t tell you, Signora Ambler, is that sunrise came as quite a surprise. And then he had to watch the finished product at least twice more to make further changes. An artist indeed.”

“Yeah, look, I’ve got to get this into the studio and then get Frank on the air. You two are welcome to watch if you want.” Jabe and Prudentia followed Janice to the studio.

Frank Jackson looked like he hadn’t gotten a moment’s sleep, either. But he refused more than minimal makeup. Jabe thought it was too bad more up-time politicians hadn’t had the sense to know that there was a time to look unphotogenic. Jabe thought that if they had, politicians would have been a lot more respected up-time than they actually were.

Janice double-checked the patch to the VOA radio transmitter, then motioned to Frank. He looked into the camera.

“I have been asked to read the following statement on behalf President Michael Stearns, as well as Emperor Gustav II Adolph of the Confederated Principalities of Europe:

“On October 7, 1633, forces of the United States Navy and United States Air Force, charged with defending the port of Wismar, engaged a Danish naval force intent on capturing that strategic port. Through the bravery of the defenders, the Danes were turned back, suffering significant losses.

“We suffered our own significant losses. Lieutenants Edward Cantrell and Lawrence Wild of the United States Navy were killed defending Wismar, as was Able Seaman Bjorn Svedberg of the Swedish Royal Navy. Air Force Captain Hans Richter continued to press the attack, and was seriously wounded. Rather than attempt to save himself, Captain Richter destroyed the Danish warship Lossen by crashing his aircraft into the ship.”

Frank paused for a moment to collect himself. He continued:

“President Stearns has said that out of the sacrifice of these four young men, a new order is being born in Europe. The Distinguished Flying Cross is being awarded to Captain Richter and the Navy Cross and Silver Star for Lieutenants Wild and Cantrell, and Seaman Svedberg. The President had told me that he also intends to ask the legislature to approve a new Congressional Medal of Honor. If it’s approved, he will ask that it be awarded to Captain Richter.

“President Stearns has also asked me to announce that he will be resigning as President of the New United States to accept the office of prime minister in a new nation to be called the United States of Europe. I will be resigning as Vice President to better serve as a staff officer under General Lennart Torstensson. Both these resignations will become effective as soon as arrangements for the new USE are finalized. Thuringia and Franconia will become a province of the USE, assuming that’s approved by the population in a special election. Ed Piazza will become Acting President until those elections are held.”

A baffled almost-smile crossed Frank’s face. “I know a lot of things are up in the air, folks, but we’ll keep you informed.”

Frank shuffled his papers. He looked into the camera, eyes bright with tears. “There’s nothing worse than having to sacrifice our young people to war. Especially fine young men from our own town like Hans Richter, Eddie Cantrell, and Larry Wild. But in the years to come, they will be remembered as heroes by those who find they have choices, when they didn’t have any before. They didn’t die for nothing, folks. I can promise you that much.”

When Pieter Paul Rubens entered the Brussels’ home of fellow diplomat Alessandro Scaglia he was surprised to find his friend and patron, Nicolaas Rockox of Antwerp, deep in conversation with the abate.

“Nicolaas,” said Rubens, clasping his friend’s arm as Rockox and Scaglia rose to greet him, “I didn’t know you were acquainted with Alessandro.”

Scaglia smiled and motioned for Rubens to take a seat next to him. “We do share an affinity for Flemish painters. Don’t we, Nicolaas?”

Rockox laughed. “Indeed we do. And since Pieter has been much occupied with the cardinal-infante’s diplomatic missions, we have had to look for new artists to patronize, haven’t we?”

“Actually Pieter,” said Scaglia, “Nicolaas is assisting me in the purchase of a house in the Keizerstraat in Antwerp and decided to visit when he learned that Anthony Van Dyck had returned from London. You know I’ve always been partial to Van Dyck’s work.”

Scaglia sat back in his chair and his eyes sharpened. “But that is why Nicolaas is here. A more interesting question I think is why are you here, Pieter? Is that abominable siege of Amsterdam over yet?”

Rubens sighed.

When the cardinal-infante had become the governor-general of the Spanish Netherlands both he and Scaglia had offered their services to the young Spanish nobleman. Like Rubens, Scaglia had extensive diplomatic contacts throughout Europe. Unlike Rubens, however, Scaglia was acknowledged as one of Europe’s premier spymasters. Originally from Savoy, Scaglia had settled in Brussels when the pro-French duke Vittorio Amedeo I had ascended to the Savoy throne. Because the duke had not wished to offend Alessandro’s elder brother, Augusto Manfredo, count of Verrua, Scaglia had been permitted to retain control of all three of his commendatory abbeys and pensions held in Savoy. Those, plus the abbey of Mandanici in Sicily that had been granted by the Spanish in 1631 as a gift for his services, had allowed him to maintain a sumptuous lifestyle in one of the best houses in Brussels.

What had especially attracted the cardinal-infante’s attention, however, was the abate’s antipathy for Richelieu. Throughout the 1620s, Scaglia had worked hard to develop extensive diplomatic contacts in France and England for Duke Carlo Emmanuele I of Savoy. He had built an excellent working relationship with the duke of Buckingham in England and with many nobles of the French court, particularly those supporting the Protestant duc de Rohan and the queen mother, Marie de Medici. With the deaths of Buckingham in 1628 and Carlo Emmanuelle I in 1630, however, Scaglia had found himself out of favor, especially when he continued to push for the support of French Protestants as a counterweight to Richelieu’s growing political power.

Like Scaglia, the cardinal-infante was apprehensive about French intentions regarding the League of Ostend and had encouraged Scaglia to maintain and broaden his contacts with the French exile community in Brussels and elsewhere. Scaglia had further cemented his relationship with the infante when his spies had uncovered a plot by leading Walloon noblemen, including the duke of Aerschot, to disconnect the Spanish Netherlands from the direct control of Spain and create a neutral territory at peace with the United Provinces. While several of the plotters had been arrested, others, including the duke, had not. That fact had intrigued both Scaglia and Rubens. It was clear to both of them that the cardinal-infante was interested in far more than being a simple creature of his older brother, the king of Spain.

Rubens waved his hand in dismissal. “Unfortunately not, Alessandro. The siege continues. The cordon is somewhat looser than it has been because the infante has had to send additional troops to Haarlem and Utrecht to put down riots and unrest by Counter-Remonstrants. The Arminians seem to be content enough with the infante’s light-handed rule, but the anti-Catholic fanatics are not and continue to campaign against him.”

A difficult knot to cut,“ mused Scaglia. “If he does not respond with force he emboldens the rebels, and if he uses too much force he makes them into martyrs for the cause.”

“Precisely,” said Rubens. “In this situation, maintaining adequate troop strength is a must—which brings me to the reason why I’m in Brussels.”

Rubens took two manuscripts out of his valise and handed one to Scaglia and another to Rockox. For several minutes the men read with little comment beyond a mild exclamation or two.

When Scaglia was done he looked over at Rubens and smiled. “So let me guess. You have promised the infante that the wonderful mechanics and men of science of the Spanish Netherlands can make this elixir, this . . .” He glanced down at the manuscript again and pronounced the final word slowly and carefully. “Chlo-ram-phe-ni-col. Am I right?”

Rubens nodded. Scaglia looked over at Rockox. “Well Nicolaas, what do you think? The Acontians?”

“Perhaps,” said Rockox dubiously. “But even then . . .” He shrugged. “There are too many unknowns here to say for sure. We need an expert’s opinion.”

Rubens cocked an eyebrow at Scaglia. “Acontians?”

The suggestion caught him by surprise. The Acontians were followers of Jacobus Acontius, an Italian Protestant from the last century who’d settled in England. He’d written Satanae Stratagemata in 1565 calling for the renunciation of violence in religious affairs. The Acontian society was established to further his ideas on religious tolerance and science. Rubens thought of them as similar to the Baconians; more tolerant and less dogmatic, yet more secretive. They were particularly strong in England and the Low Countries.

He knew who they were, of course, but he wouldn’t have thought of them as being possibly helpful in this situation.

Rockox suddenly sat forward in his chair. “Ah, I remember now! I believe I know someone who can help us. He would never admit his Acontian connections, but I know he has been very interested in the new science coming from Grantville. And he lives close by, in Vilvorde.”

“Vilvorde?” said Scaglia. “Hmmm, is this the man who did the experiment with the tree?”

Rockox nodded. “Yes, Johann Baptista von Helmont. His wife, Margaret van Ranst, is a distant cousin of mine.”

Scaglia glanced out the window, noting the position of the sun.

“Let’s pay him a visit, shall we? Vilvorde is less than four miles away and it’s time for my afternoon carriage ride anyway.”

Rubens smiled. Perhaps this wasn’t such an impossible fool’s errand after all. Together the three men rose and walked towards the front door.

Ernst Frohlich looked at the man sitting across the table from him. He was nondescript, clean shaven, and dressed in contemporary clothing, but his accented German identified him as one of the now famous “up-timers” from Grantville. The fact that the man had requested to meet him anonymously in a public house in Meiningen late at night in the middle of winter both puzzled and intrigued Frolich. Meiningen was quite some distance from Grantville, and separated from it by the entire Thuringenwald, to boot.

Still, the offer in the letter of a guilder and free meal for an hour of his time insured that he was there in the pub that evening. As a locksmith, he was used to traveling at the whims of customers to install locks in houses, estates and stores after they had closed for the day. He was no stranger to working by lamp light far into the night.

“So, may I ask what this meeting is about?”

The man looked around the room to insure that they were alone. It was late on a Tuesday night, and most of the other patrons had either left or were too drunk to pay much attention to the two men.

“Let me start by saying that I was told that you are a man of discretion, and I was assured that you could be counted on to keep any matters we discuss tonight strictly confidential. That is all that you need to do to earn the guilder I promised. For my part I can tell you that nothing that we will be discussing is in any way illegal. Do you agree to those terms?”

Ernst hesitated only for a moment and then nodded. The up-timer placed a heavy silver coin on the table and slid it over to him.

“Very well. I need an honest opinion from you.” He reached into a pouch on his belt and withdrew a small metal object. He placed it next to the guilder on the table. “Can you make something like this?”

Ernst picked up the object and turned it over in his hands. He brought it closer to the candle on the table to look at the details. The metal work was exquisite. Not extremely ornate, but all of the parts fit together tightly. The clamp at one end was spring loaded, and there was a small amount of filigree work. All of the surfaces were polished to a silver gleam. There were a few places where this silver layer had worn through, and yellow brass was showing. Whatever it was, it had obviously come from whatever future world these people had come from. He sighed and handed it back reluctantly.

“No. I cannot. I have no idea how to coat the brass with the other metal. I am sorry.”

The other man frowned. Then he pushed the thing back towards Ernst. “I am not worried about the plating. I am interested to know if you could do the rest of it.”

“Yes. It is fairly straightforward. It is only made of a few pieces. If you just want one made out of brass, I could do it in a few days.”

“Good. That is what I wanted to know. My next question is would you like to learn how to plate the brass like that?”

“Of course!” he said instantly. Over the past two years, the rumors of what these “Americans” could do had virtually flown across Thuringia and Franconia. Their metal work was renowned. To learn some of their techniques would give Ernst’s shop a decided advantage over several of his competitors, if only in novelty value. “But now I have a few questions for you. Who are you, and what exactly is that thing”

The man leaned back and smiled. “You can call me Mr. Smith for right now. And that ’thing’ is half of a small fortune if everything works out right.”

“If it is worth a fortune, then why are we meeting secretly in a pub? Your people are supposed to be such wizards with making things. Why aren’t they making these?” He eyed Mr. Smith suspiciously. “And most importantly, why me? And why do you want someone in Meiningen? I would think somewhere closer to

Grantville . . .“

The up-timer shook his head. “As I said, I was told that you are a man of discretion. One of your former clients assured me that you were both skilled, and exceedingly honest. I needed someone that I could trust with this project. The reasons I don’t want to do it in Grantville—or anywhere nearby—are simple. First, everybody there has other projects that are considered more important. Second, nobody else so far as I know has thought of it yet. And third—this explains why I came to Meiningen—I don’t want anyone in Grantville knowing what I’m doing. Not till I’m ready to start selling the product.”

He leaned forward again. “If you look here”—he pointed to some stamped numbers underneath the clamp, barely visible in the flickering light—“it says 1912. That is when this was patented in the United States. That was almost ninety years before the Ring of Fire hit us. And the original models go back maybe twenty years before that. By the time we got here, this was old technology. Almost nobody used it anymore.”

Ernst thought about that while he sipped his ale. He put the tankard down. “So I make you one of these things, and you can show me how to coat the metal? How is that worth a fortune?”

“No. You make several hundred of these things, I pay you for them and I show you how to plate them. Plating is the process. We can use gold instead of nickel to plate them. It is easier for me to get my hands on, and it will last longer.”

“I still don’t see how this is a fortune. I would be more than happy to make these for you, though to do hundreds would take some time, and you would have to pay some of the costs up front. I can’t afford to have my shop only making these for you, and neglecting our other customers.” He paused and looked back at the metal tool. “And you never answered my question. What is it?”

“It is called a ’safety razor.’ It allows you to shave without having that six inch blade waving around your throat.”

Mr. Smith picked up the razor and inserted a small, square blade into the clamp. He then held out his forearm and proceeded to shave the hair off a patch of it with remarkable ease.

“The reason I picked your shop to do this is because you have the ability to make these, I don’t. I am not a metal worker. You are small enough that you should be able to keep this a secret until we are ready to hit the market.”

“We?” Ernst asked, startled.

“Yes, we. In addition to payment for the handles, and the information on plating, I am prepared to offer you a quarter of the ownership of the business. Another quarter of the business is owned by the sword maker who is currently making the blades for these.”

Ernst thought about that while he finished the ale. A quarter of a business for staying quiet. And he would be paid for the razor handles. It was an intriguing proposition.

“So why all of the secrecy?”

“It is simple. As you can see, this is not a complicated device. Any competent smith could make one. The key to this market is name recognition. You want people to always think of your name when they think of a product. In our century, advertising was a fine art. It was done on a scale that has never been attempted here and now. People spent lifetimes coming up with ways to get the customers to remember the company names. To draw them into buying something that they didn’t really need, but felt that they could not live without. Safety razors took the market by storm when they came out. One of the first men to sell them sold less than a hundred of them the first year. And maybe a few hundred blades. Within a few years, he was selling hundreds of thousands of razors, and a proportionate number of blades. He had found a need in the marketplace, found a product, and made sure that his was the name people thought of when they went to buy a razor. There were literally hundreds of other companies that sprang up within a matter of years that copied his idea and tried to take the market away from him. That razor there was made by one of his competitors. But his company had the advantage of name recognition. And better marketing plans. A hundred years later Gillette, the man’s company, was still around. Almost none of his competitors were.”

He paused and looked around the mostly deserted inn. “The razors have to look good, and must be designed to last. That one there is at least eighty years old.”

Ernst picked up the safety razor from the table and again examined it critically. He carefully removed the blade. It was rectangular, made of blued steel. Incredibly thin, it was sharpened on one side. He drew it across his thumb, and gasped as it drew a tiny drop of blood. He stared at the up-timer. “You expect me to believe that this is over eighty years old? Impossible!”

Mr. Smith smiled “The blade is new. It is a copy of the original blades, made by the man who already owns a quarter of the business. But the handle is over eighty years old. I have been using it myself for several years now. And it belonged to my grandfather before that. He bought it used as a young man, and used it for several years before moving on to a better, more modern design. As you can see, there is only a little wear for how much it has been used. But the blades only last about a week. There is where we make the money. People will have to come to us to get replacement blades. We can make them cheaper than their local blacksmith, because we will have a shop that is doing nothing but turning out these blades as fast as they can. Again, I am not a metal worker. But I do have some knowledge on how some of the original up-time things were made, and I have spent the last year doing research and experimenting. We can gold plate the handles and make them last for many years. As long as they last, the customers will keep coming back for blades. It is just the way people are. They won’t want to spend the money to buy a different razor if the one they have still works.”

“I will want something legal in writing. If this is as big as you say it will be, I want something that spells out exactly what you have proposed.”

Mr. Smith grinned. “So does that mean we have a deal?”

“Yes. We do.”

To: Grantville Emergency Committee.

From: John Sterling, Edgar Frost and Francis Kidwell.

Date: May 30, 1631? fifth day after the disaster.

Re: Road options around Schwarza Falls.

Yesterday, May twenty-ninth, the fourth day after the disaster, we went up Buffalo Creek to the power plant to look into how to build a road connection over the border into the lands to what is now the southwest. You asked us to tell you everything, even if we weren’t certain it was important, so pardon us if we ramble a bit.

I. The Situation

The report from the power plant is correct. There’s a real castle up there looking down on us. Don’t imagine a fairy-tale castle. This is a deadly serious looking fortress. There’s also a bit of a village there, or at least half of one. The village and the castle are both named Schwarzburg. We need to make friends with whoever runs the place, because they’re guarding our southwest flank very nicely. And, if their cannon are even mediocre, I doubt there’s much we could do to stop them from wiping out the power plant.

As you come around the bend in Buffalo Creek, about a mile out from Grantville, what you see is a wall of black rock, streaked with red, green and brown. This castle sits on a hill dead center on top of it, right above the power plant. The cliff has a mirror polish on it that reflects the sky when you get close enough. We guess that from the bottom of the Buffalo Creek valley up to the floor of the valley above, it must be three hundred feet. Our ridge tops are about four hundred feet above the valley floor, but the hills of the land we’ve been plunked into are much higher. We guess about twice as high, which means eight hundred feet up from the valley floor. The German hills aren’t as chopped up as ours. They seem a bit rounder, but the valley walls are steep enough.

There’s a stream in the valley we cut into. They call it the Schwarza, and where it flows over the cut edge, there’s quite a waterfall. We’ll call it Schwarza Falls. It’s hard to guess how high it is, because it’s pounding down on what was a steep slope and washing quite a bit of that slope downhill. We figure it’s a clear fall of at least fifteen feet, but then it tumbles down at least two hundred feet before it flows into what used to be Spring Branch.

If it hadn’t been for the fact that the Schwarza valley is offset a bit from Buffalo Creek valley, there’d be no hope of getting a road up that cliff. As things stand, though, the Schwarza had a loop to the northeast that got lopped off by the disaster. (We’re starting to call it the “Ring of Fire,” by the way, since that seems a pretty good description of the disaster—“RoF” for short.) The ridge to the north of Buffalo Creek just manages to come up to that part of the Schwarza’s stream bed. Also, just southwest of Schwarza Falls, there’s a little knob on our side that just goes up to the level of the rooftops of some houses nearby. It’s all that’s left of the ridge that divided Spring Branch from Buffalo Creek.

One thing is real clear. That little village at the top of the falls is in big trouble. Half the place is gone. Calling it a village may be too generous; it was a cluster of houses and barns built beside a bridge across the Schwarza. In a few places, the ground collapsed as far back as thirty feet from the edge, taking houses and barns if they happened to be there. There’s quite a mound of muck and rubble along the face of the cliff below those places. There’s one barn, though, that’s standing right on the edge and hasn’t moved an inch.

The cut-off chunk of the Schwarza northeast of the castle must have dumped its entire contents and a good part of its riverbed over the cliff in one great gush. There’s a flow of debris from there down along what used to be Spring Branch Creek. It looks like what was left of Spring Branch Road inside the ring of fire was pretty well buried or washed out within a few minutes on Sunday. The culvert over Spring Branch Creek on the main road looks like it survived that first gush, but it was never intended to take the flow of the Schwarza river, so the road is acting like a dam. The water was over the road when we got there. It’s a few inches deep and running fast, but the road is pretty flat so the overflow is spread over quite a distance. It’s eating at the road, and we think it’ll wash it out unless we dig up the culvert and put in a proper bridge.

We waded across and took a hike up what’s left of the ridge that divided Buffalo Creek from Spring Branch. It’s the steep but direct route into what’s left of the lower Schwarzburg village. They were watching us the whole time, and there’s no doubt that they were as nervous about us as we were about them. By the time we got up the hill, a guy named Franz was there to meet us, with two others who stayed back a bit and whose names we didn’t get. Franz seemed to be an officer in the guard of the castle. As near as we could make out, his boss is the graf of Schwarzburg and a town named Rudolstadt.

Franz turned out to be a decent fellow and pretty quick witted, but he had some big pistols in his belt and a sword. We were careful not to put our hands anywhere near our holsters those first few minutes. We’d better send someone official to Schwarzburg quickly, someone who knows German!

We read Franz the message you wrote for us in German about wanting to open the road connections across the border of the “ring.” After we gave him the letters you gave us, we tried to have a conversation. I wish we knew more German, but the stuff you gave us helped a lot. With lots of mistakes, hand gestures and an occasional picture on a notepad, we managed to get by.

He told us that the Ring of Fire destroyed the road from Schwarzburg to Rudolstadt where, as near as we could make out, his boss lives most of the time. It also destroyed the road to the town of Saalfeld. As a result, it seems that we’re in agreement about trying to open up a road connection.

The bridge across the Schwarza at Schwarzburg is right at the lip of the falls. It’s in serious danger of collapse because of all the dirt that’s been washed away from the foundations. If the bridge goes, the farmhouses that are left on the southeast side of the Schwarza will be cut off, so they’re already working on a temporary wooden bridge upstream from the old one. Timber is one thing they have plenty of. The roads here are mostly grass and packed dirt, with cobblestones only where erosion is likely to be a problem.

Northeast from the falls about two hundred yards, the road is almost cut off with half of it slumped away. It looks like it was right on the riverbank there, at the southeast end of the loop of river that the Ring of Fire sliced off. Beyond that, to the northwest, the road is in good shape, with stone retaining walls in places as it takes a long switchback up the slope to the castle gate.

We didn’t go into the castle, but we did go up to the square by the gate where there’s a bit of an upper village. The castle sits along the crest of a knife-edge ridge with the Schwarza river wrapped around the west, south and east sides. You couldn’t ask for a better defensive position, but it’s not all that big. The castle must be a quarter mile long but the ridge isn’t very wide anywhere.

II. Road Proposals

Franz, the officer, must have been thinking about the problem of getting a road down from Schwarzburg, because he took us to the jumping off point where a new road could connect. He pointed out the route he thought would work before we left to walk down that way. We agree with him, so we’ll describe that route and forget the others.

Be aware, we’re not engineers, just three guys who’ve had plenty of experience building and maintaining roads. We’re confident that we can do this job, and do it well, but under the laws of West Virginia, we aren’t really qualified. It would be nice if there was a civil engineer to help with this project.

The road would turn north just east of the old Spring Branch road and traverse up the east side of the Spring Branch valley. This would almost follow the power company right of way once the power line gets on the same side of the creek. Then, the road would turn broadly around the head of the valley to meet the northwest end of the abandoned riverbed of the Schwarza. The climb up out of the riverbed would be short, and we’d meet the road up from the lower village about a quarter mile northwest of the waterfall.

We figure this would be about four thousand feet of road climbing three hundred feet, so the grade should be under eight percent. On the walk down, we flagged the path we followed while using a pocket clinometer to try to keep our path at seven percent. That brought us out a bit on the high side, but those flags should make charting the path back up pretty straightforward.

We figure that a crew with a medium dozer and a couple of chainsaws could carve a temporary one-lane road up to Schwarzburg along the Spring Branch route in about a day. That’s about two hours at half a mile an hour for the first pass of the dozer to cut the roadbed, or about two hours, and then three more passes to shape the crown at a mile an hour, make that three hours. That’s five hours of an eight hour day, but it’s fair to budget the whole day to allow for the unexpected. There’s some decent timber along the way we ought to try to salvage while we’re at it.

There’s so little watershed above our proposed route that a temporary road like that could last a few years, we think. But with another day of work to put in about five culverts, we could make a road there that would last. We think at least two of the old culverts along Spring Branch Road can be recovered with a winch and some digging, so someone should inventory culverts we can salvage from elsewhere.

With three days work and several truckloads of crushed rock, we could make the new road meet county standards for unimproved roads, which is something none of the roads we saw up on top manage to do. Two days of this would be to widen the road to two lanes, and one day would be to put down the rock and grade it nicely. If we put in the culverts soon enough, the road widening can wait until the traffic demands it.

We noticed that the power plant has a Caterpillar D6. They use it for pushing coal around. We asked about it at the front gate, and the guard there phoned the plant manager, Bill Porter. The upshot is, the power plant is willing to loan the dozer to the county for a day’s work. They think that anything we can do to get the folks in that castle on our side would definitely be a good idea.

III. Defense

Finally, you asked us to say something about defending our new borders. If the folks who run Schwarza castle fail to block invaders, or if they decide to attack us, we could defend this end of the valley from the ridge northeast of Spring Branch. That would let us look down on our new road from about two hundred yards and we’d look across at the steeper slope down from the lower village from a distance of about four hundred yards. The castle would have an altitude advantage on us, but the ridge would offer cover and we could dig bunkers into the ridge top. You might want to put a jeep trail up to there from the valley behind the ridge.

The other defensive position would be on the ridge top across Buffalo Creek southeast of the power plant. This would look straight down our new road from a range of six to twelve hundred yards. Again, a bunker would be handy, but the castle hasn’t got a good shot at this position because the chopped off hillside southeast of the castle is in the way. The big threat here is from snipers sitting right on the edge of that hillside, but the ground slopes down steeply to that cliff edge, enough so they wouldn’t be able to hide behind the terrain. It looks steep enough that they’d have to worry about sliding right over the edge if they slipped.

John Sterling has the most military experience of any of us. He says he’d put mostly snipers on the ridge above Spring Branch, along with a few mortars or RPG launchers, and he’d put the light artillery on the south. Do we have any weapons heavier than hunting rifles? All in all, we agree that we’d much rather defend Grantville from Schwarzburg Castle. Seen from Schwarzburg, it looks like the cliffs do a good job of blocking all access to Grantville for over a mile in either direction, perhaps more. The castle is the strong point that covers both paths into the valley.

IV. Other

Franz told us that there were people in some of those houses that went over the edge. We had trouble communicating about this, but I get the feeling there might be ten bodies somewhere at the bottom of the cliff. We said that he was welcome to send people down to try to find the bodies, and we said that we would try to get people to help.

To be delivered to Ludwig Guenther, Graf of Schwarzburg Rudolstadt, or in his absence, to the head of the guard at Rudolstadt:

Your humble servant, Franz Saalfelder, officer of the guard at Schloss Schwarzburg, begs to report again on the strange events of these last few days.

I do not know that you received my first report of the events of Sunday, the fifteenth day of May, but the scout sent from Rudolstadt on that day arrived here on Tuesday, having worked his way to Schwarzburg along a very difficult route. God willing, he will have completed his circuit and returned to Rudolstadt by now with even more to report.

Sunday, the fifteenth day of May, at around noon, the very earth seemed to shake with the roar of thunder. The guards on the east-facing battlements were blinded for a moment by a wall of light that seemed brighter than the sun but as brief as a lightning flash. Fortunately, your humble servant was not looking that way at the moment, but the roar was horrible even indoors.

What devilment it was I cannot say. At first, I was sure that the very pits of Hell had opened, for all of the land to the north and east of Schwarzburg had disappeared. Where the valley of the Schwarza and the road to Rudolstadt had been, there was nothing but a pit, hundreds of feet deep, with a strange country on the bottom. Half of the houses and barns beside the Schwarza were gone in an instant, and some of the flat land beside the river fell over the edge shortly after, taking another house and two barns.

We cannot say for certain how many people were lost when the pit opened, but it cannot have been less than ten. It is fortunate that it was a Sunday and many had yet to leave the castle where they had attended chapel services that morning. Those who hurried home to fix their Sunday dinners were the victims, while the lazy who stayed to talk were saved. Fortunately, most of the refugees fleeing the mercenaries who have lately been a plague on the Saale valley have been moving on up the Schwarza into the well protected villages beyond Schwarzburg. Some of the survivors from the lower village want to go down into the pit to look for bodies so that they can have a proper burial. We can see wreckage of some of the houses that slid over the edge of the pit just after the pit opened. There may be bodies among the wreckage.

The scout you sent followed the north and west rim of the pit on his travels from Rudolstadt to Schwarzburg. He tells me that it is not entirely a pit because in some places the mountains of the strange new land within overtop our valleys. Of more import, the pit appears to be a near perfect circle, several miles in size, reaching from the edge of the valley of the Saale all the way to Schwarzburg. God willing, you will have heard his report by the time I write this.

Our chaplain cannot say whether this strange occurrence is the work of the Devil or not. His advice appears as sound as it is trite, to hope for the best while preparing for the worst. We have posted guards to report on what is within. Day and night, I have been called to the battlements or to the very edge of the pit to witness the strangest of events.

The land within the pit is occupied. There are houses of strange construction there. The strangest is a great brick building not far from the edge below Schwarzburg. At first, I thought the building was a fortress, for it is great enough to be one. Now, I believe it to be some kind of mill or forge, for they have a great pile of what looks like charcoal outside the building, and there are great smokestacks, although there is now no great amount of smoke. Immediately after the blast and blinding flash that created the pit, this fortress or mill was emitting a loud roar of noise that went on and on, loud enough to block out all else, and horrible. Great clouds of white smoke or steam rose from the mill and ceased when the noise ceased. Since then, it has been quiet, except for an occasional puff of steam and an occasional strange noise.

There are roads within the pit that look finer than any road I have ever seen. They are wide enough everywhere for two wagons to pass, smooth and well drained, with broad ditches to each side to carry away the rainwater. What is most terrifying is that they have wagons that appear to move as if by magic, sometimes faster than a horse can gallop and with nothing to pull them along. Watching from the castle and from the edge of the pit, we can see that the people within are not pleased. To them, they are within a great stone wall with few escapes, and we have seen groups of them looking up and pointing in our direction from the great mill. Their roads once went beyond the walls of the pit, perhaps. There are lines of strange towers leading away from the great mill to the north and south that support ropes made of wire. Where the Schwarza pours over the wall into the pit, it has created a new river that is flowing over one of their roads and will soon destroy it. The same new river also threatens to topple one of the strange towers.

There are two places near Schwarzburg where the hills within the pit come up to the level of the ground outside. One is just south of the bridge across the Schwarza below the castle, and one is to the northwest where the road used to turn east along the north bank of the Schwarza. We sent scouts into the pit that way with orders to stay hidden and to leave no sign of their passage. They report that there is a town several miles into the land where two valleys meet and that there are also smaller villages. There are even churches, or at least buildings that look like churches, with steeples surmounted by the symbol of the cross. This gives our chaplain some comfort.

The scouts reported many strange things. They have found twisted wire fences that must be many miles long, with sharp barbs of cut wire twisted onto the fence wire. The quality of the wire was very good, but in many places, they report that it was rusted, as if nobody ever took the time to care for it. All of the houses they spied out were very strange, constructed more of sawn wood or brick than of stone and plaster, and well painted. At night, many of the houses are lit up like daylight, with lights brighter than hundreds of candles. Even barns that are old and run-down have too many windows glazed with large panes of the most perfect glass anyone has ever seen. The towns, and even some houses outside the towns, have hellishly bright lanterns mounted on poles overhead so that people can move about at night just as freely as they do in the daylight.

Today, Thursday the nineteenth of May, three men from within the pit came up the hill. We met them at the bridge over the Schwarza, and I must report now what we learned in talking with them, or in trying to talk, for it was difficult.

These men were dressed most outlandishly. Even from the castle, even when they had not yet begun to climb, that much was evident. Each man wore a yellow helmet and an orange vest; the orange color was unnaturally bright. As they came closer, it was apparent that they wore blue pantaloons, cut very close and exceedingly well made but well worn and with the color faded. Under their orange vests, they wore well cut shirts, and each man wore a belt from which hung several things. All three men wore what must have been pistols, very small ones, but arms, nonetheless.

After we tried to talk, one of the men let me try on his helmet. It was very light compared to what I expected, not metal, but something much lighter and yet harder than leather. The helmet did not rest on the head, but was supported away from the head on a clever network of straps. I feel that a blow to the helmet would not be felt directly, not with those straps in place.

They also saw that I was curious about the implements on their belts. One of them showed me a most remarkable knife. It was small enough to fit into the palm of my hand, but it could be unfolded to reveal a knife blade, a file, a pair of pincers, and several other kinds of picks and implements, perhaps ten in all. Not only the blades, but the handle itself had the look of the finest silver, and yet it was as hard as the finest steel.

They speak English, it seems, and a little French, very little. Unfortunately, we have no English speakers in our garrison. They came prepared knowing that we spoke German, with a message written in German that they read to us and with a remarkable letter that they gave to us, which we include with this message. There are many things we would have spoken of if we had been better able to communicate.

Their message confirmed that the town in the middle of the pit is called Grantville. My spies had reported signs within that said “Welcome to Grantville” on the roads outside the town, so this was not entirely new to me. I remain puzzled why an unprotected town would post signs saying welcome, if indeed that is what the signs say.

At first I thought the name Grantville sounded French, but their message explained that they are from a land called West Virginia in the United States of America, that they came from hundreds of years in the future, and that they have no idea how or why they are here. The message also confirmed my guess that their appearance in the pit has caused a crisis. They say they are governed by the Grantville Emergency Committee, clearly not a proper government and certainly not the government of this West Virginia or United States.

Their strange clothing and tools certainly suggest that they are not from our world, but their letter is dated Wednesday the twenty eighth of May, 1631. From this, I gather that they are using the Catholic calendar of Pope Gregory and that they have already communicated with someone on the outside of the pit.

The men’s names were John Sterling, Edgar Frost and Francis Kidwell. They printed their names in Roman letters on a piece of paper that they gave to me and that I enclose with this message. Each of the men had a small book of blank sheets of paper cleverly bound with a spiral piece of wire, and each man had a pen of some strange kind that did not need an inkpot. They used them freely, drawing pictures when they did not know the words.

These men were well educated, able to read fluently even when they were reading German, a language they obviously spoke very poorly. I am being generous; they spoke almost no proper German but only some words. All three were also able to write quickly and well. This is why it took me a while to understand that they were not military men, nor were they ambassadors. Rather, they saw themselves as simple laborers, charged with but one job, that of finding the best way to build a road from the bottom of the pit up to the road at Schwarzburg. Of course, that is what their message said, but appearances can deceive and then deceive again.

I asked these men about the dead who had fallen into the pit, and this was a difficult question, both because of the language and because, I think, it was outside their authority. They said that we were welcome to send a burial party into the pit to recover the bodies, and they said that they would try to send help. I believe that they were sincerely troubled by the deaths.

Without being able to ask your leave, but knowing how important it would be to reestablish the road from Schwartzburg to Rudolstadt, we gave them permission to survey a route for connecting our roads to theirs. They will certainly not be using any new road without our leave, because Schwarzburg castle is perfectly placed to guard any road they can build. Their message did say that the road would be open to us, and that we would be welcome to use it to travel through Grantville to reach places to the north and east.

We had already been discussing the problem of a road into the pit among the guards, since we are worried about how to get food supplies up to Schwarzburg. The farmland in the Schwarza valley cannot feed the normal population of the valley, and even though most of the refugees have brought several weeks of provisions, we will face problems if we cannot reopen the roads. Bringing food in over the hills from Hildburghausen could double the cost of cartage, and it would be even more expensive to pay for cartage around the pit from Rudolstadt.

I hope I have not abused your trust! I showed these men the path into the pit that we thought would work. In showing this, I was careful to walk ahead to assure that there were no footprints visible, since our spies had crossed into the pit very near the point where I took them.

I watched the men walk back down into the pit, and I was surprised to see that they took a longer path, swinging broadly around the little valley that comes up from the pit to meet our land. They seem intent on building a road much longer than the road I would have thought of, but at a far more gentle slope. One of them had a hand-held instrument of some kind that he would occasionally use to look backward or forward along the path they were marking, while another of them would occasionally tie a strip of orange ribbon to a tree or sapling to mark the path.

I humbly beg your forgiveness if I have erred in carrying out my duties in these trying times. I will send a horseman with this letter Friday morning, with instructions to travel quickly around the pit to the north, then east to the Schaalbach road into Rudolstadt. Your scout assures me that this route should be safe, although it comes close to the pit at Rottenbach and even closer in parts of the Schaalbach valley. Until we learn that passage through Grantville is truly safe, I believe this is the best route available.

Your humble and devoted servant, Franz Saalfelder.

To: Grantville Emergency Committee.

From: Mark O’Reilly.

Date: Saturday May 31, 1631.

Re: Visit to Schwarzburg.

At the town meeting, you asked everyone with military experience to notify the emergency committee, and you asked everyone who knew German to notify the committee. I put in my name for both, but I never imagined that Rebecca Abrabanel would come visiting on Friday afternoon to test my German and then send me out immediately on a job. I feel that I’m in way over my head, but I guess we all are.

Ms. Abrabanel showed me a memo that some guys from the road department had just written. She asked me to read it, and then she asked me what I thought we should do. I told her we ought to send someone who knows German, someone who this officer of the guard named Franz could relate to as an equal, so that we can cut a deal with him. Then I understood it was me and I tried to back out.

Ms. Abrabanel explained that I was the best she could find on short notice. The job needed someone who spoke German, even bad German like mine. It had to be someone who had military training, and my Guard training would do. You don’t send a general to make a field agreement with a captain, you send another captain, and you back him up with a couple of privates, and in this case, with a burial detail to help the Germans.

So this morning, I went up to the power plant with Pete McDougal and Ron Koch, who have mine safety experience, and Brick Bozarth and Miles Drahuta, who have UMWA training in mine rescue. We took the equipment McDougal and Koch recommended, and we ended up using most of it. We worked all day, and I’m tired. But Ms. Abrabanel said she wanted this report as soon as possible, so I’m trying to get it down on paper before I quit for the night. Thank God for computers. I wonder how long they’ll last.

I. Rescue and Recovery

We found a small crew of Germans working through some wreckage at the bottom of the new Schwarza Falls. Conditions were very unsafe because the falls are cutting into the ground very quickly at the base. The Schwarzburg castle chaplain was there, Pastor Hermann Decker. I did my best to explain that we were there to help and asked what we could do.

There was one problem. These people don’t usually speak the High German I learned in school. They have a regional dialect, so between that and my rusty German there were many places where we stumbled. It was a good thing I had my old English-German dictionary along, because there were lots of words that gave me trouble. Even Ron’s native twentieth-century German wasn’t much help.

They had already taken out four bodies. They were concentrating on the areas where wreckage showed among the rocks, sand and gravel that had come over the edge after the Ring of Fire.

The horrible thing was, if we’d known to rush out there last Sunday, right after the Ring of Fire, we’d have probably saved some lives. Some of what went over the edge fell hundreds of feet, but other stuff flowed down the slope after only a short drop. We didn’t know, of course, but all of us would rather have saved people’s lives than just dig up the dead.

McDougal and Koch insisted that the first thing we needed to do was to make the workplace safe, so they improvised a bridge across the foot of the falls using fallen trees and set up safety ropes. I was left to try to explain to the pastor that we were going to use a chainsaw to trim the fallen trees and that it might upset the Germans at first because it was both noisy and strange. Once the bridge was up, Ron went back to work on opening the mine, so we were without him for most of the day.

The Germans were very impressed with the chainsaw, but the simple come-along we used to winch the tree trunks together side by side was just as novel. The come-along and chainsaw helped quite a bit with digging through the building remains that had fallen over the cliff. Those houses were half-timbered, with mortise and tenon joining. Most of the joints snapped, but the timbers were very heavy and some parts of the framework that fell almost flat held together. Being able to quickly cut them apart and pull the pieces away was a real help. By noon, we recovered three more bodies. In the afternoon we recovered two more. If there are more bodies, they are likely to be deeply buried.

Some of the Germans doing the digging obviously knew the victims, because when they found bodies, they knew their names. Some of them broke down pretty badly, and Pastor Decker had his work cut out comforting them.

II. Relations with the Castle

There were observers on the cliff top overhead all the time. We saw them when we arrived in the morning, and made a point of waving to them in a friendly way before we went to meet with their work party below. They watched us pull together the temporary bridge. In midmorning, just before eleven, a delegation came down, a dozen or so. Most of them were there to join in the work, but there was also an officer and two guards.

The officer’s name is Franz Saalfelder, and he’s the same guy our first crew met with last Thursday. I think his last name isn’t really a family name, but that it really means he’s from the town of Saalfeld, the town just to our east. He’s a captain of the house guard in the service of Graf Ludwig Guenther. Graf means count, and he’s the ruler of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt. I suppose you could say that Grantville is now in the county of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt.

One interesting thing I found is that the people in Schwarzburg all seem to refer to the Ring of Fire as “the pit.” They saw the flash and heard the boom, same as we did, but to them, it was like a great pit opened up and there we were at the bottom. As near as I can figure out, the captain had the following subjects on his mind:

First, he is really worried about resupply. The Ring of Fire cut his primary supply line, and getting food in over the hills is going to be very expensive. Down in the Saale Valley they grow grain and vegetables, but up here in the hills the farming they do is mostly livestock. The economy is largely forestry and mining. I’m guessing that the Schwarza valley has always been a food importer.

Second, he is worried about refugees. We aren’t the only ones worried about those raiders in the farmland to the north and east. They’ve driven people from their homes, and some of those have come up the Schwarza valley to the area protected by the castle. The resupply problem would be serious without the refugees, but with them, everything is worse.

And, of course, he’s worried about us. I told him that we were worried about him too, since he has the high ground, but that I thought we were better off cooperating. I told him about the skirmishes we’ve had with the raiders, and said that we would do everything we could do to make sure that they never got through Grantville to him.

That led him to ask about our weapons. He said his scouts had been all the way around the Ring of Fire, or the pit, depending on whose words you use, and that they had heard stories about some of our skirmishes. All I had was a pistol, and I’m no great shot. I gave him a demonstration, then pulled the clip from my gun and let him handle it. He seemed fascinated by the idea of putting the bullet, powder and primer all together in one cartridge and also by the complexity of the pistol mechanism.

The captain was curious about what the power plant was, and I had no good way to explain that. He had already guessed that it was some kind of mill or forge. I told him that it was a mill, but that I didn’t know how to explain what it was that we make there. All I could do is give him a name for it. So, now it is an Electrischemühle. I explained that when he sees bright lights at night, those lights burn the electricity they make there.

One thing the captain let slip may be of importance. The graf is away north, fighting the Catholic armies and trying to keep the Swedes out of his lands, despite the fact that they are officially on his side. So the captain is almost on his own. There is a garrison at Rudolstadt, and he’s managed to reestablish communications with them.

I explained to him that the road crew would get to work Monday with his permission, to build a road up to Schwarzburg. Then I explained that it might alarm the Germans because we would use machines.

III. The Military Threat

I only went up to the castle when we took up bodies. Even then, I wanted to make sure we got the body bags back, so I didn’t see that much. Yes, they have cannon, but how many I can’t say. I saw only one, from a distance. It was tarnished to a brown shade that looked like brass or bronze and it had a barrel perhaps four feet long and a foot around at the breach. I couldn’t see the muzzle or any cannon balls, so I don’t know the caliber. It didn’t seem right to be nosing into things like that, what with the job of getting the body out of the body bag and into a burial shroud.

IV. Church Relations

I don’t know if anyone in Grantville has thought through what’s going to happen between us and the churches of this land. I remember studying in Sunday School about the Reformation and Counter-Reformation and how hard it was for the Church to come to grips with religious diversity.

Pastor Decker didn’t get to this subject right away, but you could tell from the way he asked it that the answers we gave would be important. He asked what religion we were in Grantville, after he’d noted that he understood that we were using the Gregorian calendar, which he thinks of as the Catholic calendar.

I explained that I was Catholic and so is Miles Drahuta, and then I had to ask around. Ron Koch turned out to be Lutheran, Brick Bozarth was Church of Christ, which I had to explain was another Protestant denomination, and Pete McDougal added to the confusion by saying that his wife was Catholic but that he was more of a non-practicing Presbyterian than anything.

The pastor wondered if the fact that more of us were Catholic than any other religion was the reason that Grantville used the Gregorian calendar. I explained that the whole world switched to that calendar long before I was born, not because of religion, but because it worked better than the old one.

The pastor was very confused by the fact that we could work and live together not caring that our neighbors or coworkers had different religions. It took me a while to figure out how to answer him, but I think my answer was good. I told him that we have only to look back on the Thirty Years’ War and all the other wars of religion to see how failure to tolerate religious difference can ruin entire nations.

He asked how could I, a Catholic, justify helping to properly bury Lutherans, when my church had declared that they were certain to burn in Hell. I asked him how could I, as a Christian, refuse to help properly bury another human, as all of us are made in God’s image.