Eneko Lopez was not the sort of man to let mere discomfort of the body come between him and his God. Or between him and the work he believed God intended him to do. The Basque ignored exhaustion and hunger. He existed on inner fires anyway, and the fires of his spirit burned hot and bright. Some of that showed in the eagle eyes looking intently at the chalice on the altar. The low-burned candles and the fact that several of the other priests had fainted from exhaustion, cold or hunger, bore mute testimony to the fact that the ceremony had gone on for many hours. Without looking away from the chalice upon which their energies were focused, Eneko could pick up the voices of his companions, still joined in prayer. There was Diego's baritone; Father Pierre's deeper bass; Francis's gravelly Frankish; the voices of a brotherhood united in faith against the darkness.

At last the wine in the chalice stirred. The surface became misty, and an image began to form. Craggy-edged, foam-fringed. A mountain . . .

The air in the chapel became scented with myrtle and lemon-blossom. Then came a sound, the wistful, ethereal notes of panpipes. There was something inhuman about that playing, although Eneko could not precisely put his finger on it. It was a melancholy tune, poignant, old; music of rocks and streams, music that seemed as old as the mountains themselves.

There was a thump. Yet another priest in the invocation circle had fallen, and the circle was broken again.

So was the vision. Eneko sighed, and began to lead the others in the dismissal of the wards.

"My knees are numb," said Father Francis, rubbing them. "The floors in Roman chapels are somehow harder than the ones in Aquitaine ever were."

"Or Venetian floors," said Pierre, shaking his head. "Only your knees numb? I think I am without blood or warmth from the chest down."

"We came close," Eneko said glumly. "I still have no idea where the vision is pointing to, though."

Father Pierre rubbed his cold hands. "You are certain this is where Chernobog is turning his attentions next?"

"Certain as can be, under the circumstances. Chernobog—or some other demonic creature. Great magical forces leave such traces."

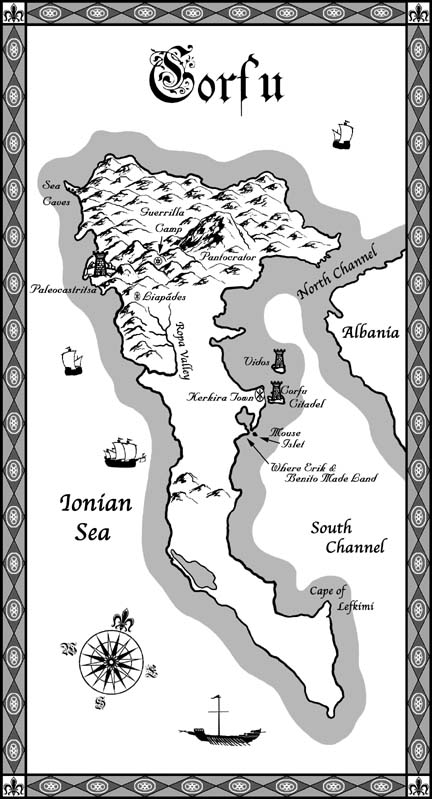

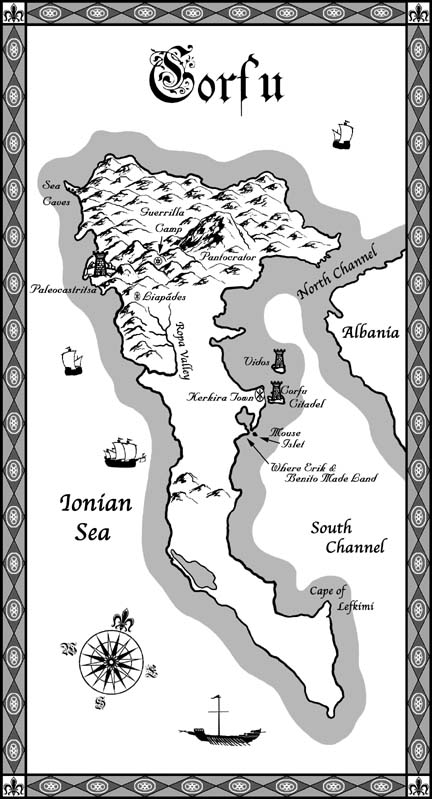

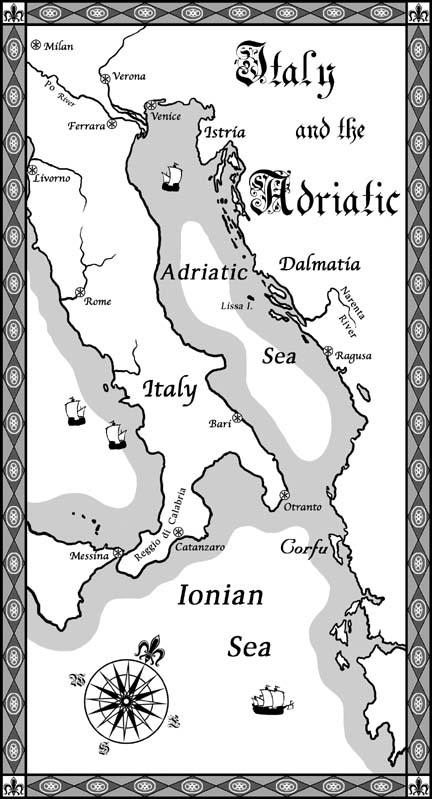

"But where is it?" asked Diego, rubbing his back wearily. "Somewhere in the Mediterranean, an island, that much is clear. Probably in the vicinity of Greece or the Balkans. But which? There are a multitude."

Eneko shrugged. "I don't know. But it is an old place, full of crude and elemental powers, a repository of great strength, and . . ."

"And what?"

"And it does not love us," Eneko said, with a kind of grim certainty.

"It did not feel evil," commented Francis. "I would have thought an ally of Chernobog must be corrupted and polluted by the blackness."

"Francis, the enemy of my enemy is not always my friend, even if we have common cause."

"We should ally, Eneko," said Francis firmly. "Or at least not waste our strength against each other. After all, we face a common enemy."

Eneko shrugged again. "Perhaps. But it is not always that simple or that wise. Well, let us talk to the Grand Metropolitan and tell him what little we know."

Count Kazimierz Mindaug, chief adviser and counselor to Grand Duke Jagiellon of Lithuania, scratched himself. Lice were one of the smaller hazards and discomforts of his position. To be honest, he scarcely noticed them. The Grand Duke tended to make other problems pale into insignificance.

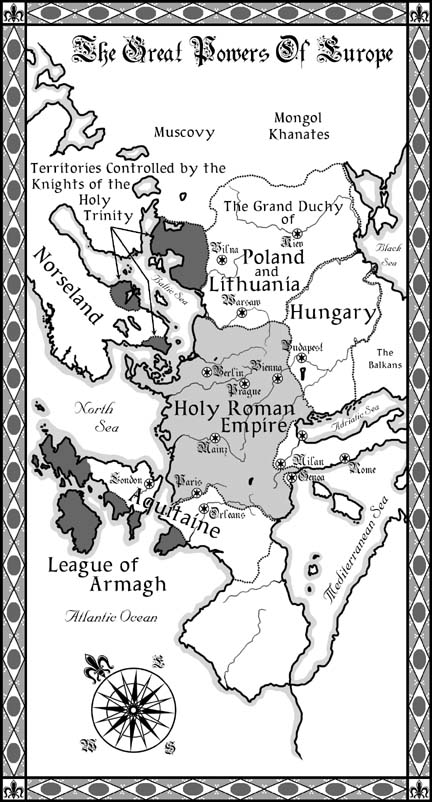

"If a direct attack on Venice is out of the question now, given our recent defeat there," he said, calmly, "then why don't we just hamstring them? We can paralyze their trade. The Mediterranean can still be ours. We can still draw the enemy into a war on a second front."

The terrible scar on Jagiellon's forehead pulsed; it looked like an ugly, purple worm half-embedded in his skin. A throbbing worm. "The Holy Roman Emperor looks for our hand in everything now, since the disaster in Venice. Charles Fredrik would ally openly with the accursed Venetians. Their combined fleets would crush our own, even in the Black Sea."

Count Mindaug nodded his head. "True. But what if our hand was not shown? What if those who at least appear to oppose us, took action against Venice and her interests?"

The Grand Duke's inhuman eyes glowed for just a moment, as the idea caught his interest. Then he shook his head. "The Emperor will still see our hand in anything."

Count Mindaug smiled, revealing filed teeth. "Of course he will. But he cannot act against his allies. He cannot be seen to be partisan, not in a matter that appears to be a mere squabble between Venice and her commercial rivals, especially when those rivals are parties with whom the Empire has either a treaty or a very uneasy relationship."

Jagiellon raised his heavy brows. "Ah. Aquitaine," he said. "I have hopes of the Norse; my plans move apace there. But it will take a little while before their fleets ravage the north. But Aquitaine, even with Genoa's assistance, cannot bottle up the Venetian fleet."

Mindaug flashed those filed teeth again. "But they could blockade the pillars of Hercules. And if the Aragonese join them, and perhaps the Barbary pirates too . . . they will easily prevent the Venetian Atlantic fleet from returning. And let us not forget that you now hold Byzantium's emperor in thrall."

Jagiellon shook his head. "It is not thralldom yet. Let us just say we know of certain vices which even the Greeks will not tolerate. We wield a certain amount of influence, yes."

"Enough to send him to attempt to regain some of his lost territory?" asked Mindaug, shrewdly.

After a moment, Jagiellon nodded. "Probably. The Golden Horn or Negroponte?"

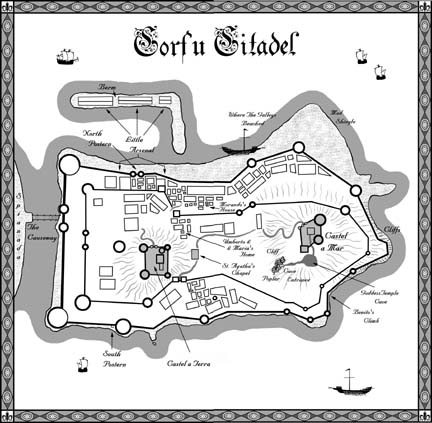

Mindaug smiled, shark-like. "Neither, my Lord. Well, not directly. If Byzantium reduces the ability of the Venetian fleet to extract vengeance on Constantinople, and on their shipping, then the Golden Horn, Negroponte, and even Zante are theirs for the taking. Even the jewel, Crete. But while the Venetians have the freedom of the Mediterranean, Alexius dares not seize Venetian property. And one island is the key to the Adriatic. To bottling the Venetians into a little corner. Corfu. The Byzantines attack and capture Corfu in alliance with Emeric of Hungary. Corfu is the key to the Adriatic. With it captured . . . Venice's traders die."

The scar on Jagiellon's head pulsed again. "Corfu," he mused, speaking the syllables slowly. "But Emeric is not a thrall of mine, not yet. He seeks to challenge me. I will devour him, in time."

Jagiellon's metal eyes looked pointedly at the count. "And anyone else who tries to become my rival, rather than my ally."

Cold sweat beaded under Count Mindaug's heavy robes. Of course he had ambitions. To be part of this court you had to have them. It was a dog-eat-dog environment. But he knew just how well Grand Duke Jagiellon defended his position. He knew—or at least he thought he knew—just what Jagiellon had ventured into, and what had happened to him.

Kazimierz Mindaug was no mean sorcerer himself. You had to be to survive in the quest for power in Lithuania. He had experimented with dangerous rites—very dangerous—but there were some things he had held back from. Jagiellon, he guessed, had not. A demon now lurked behind those metallic, all-black eyes. The arrogant prince who had thought to summon and use Chernobog was now the demon's slave. The prey had swallowed the predator.

The Count cleared his throat, trying to ease the nervousness. "Our spies have reported that Emeric has been on secret expeditions down in the southern Balkans, beginning in the spring. It is a certainty that he must be looking at expansion there. A judicious hint or two to the Byzantines, and he would not even smell our hand. Corfu would offer him a safe staging post for attacks on the hinterland."

The Count smiled nastily. "After all, the Balkans can distract Charles Fredrik as well as that mess of principalities called Italy. He would be obliged to stop Emeric of Hungary. And if the Hungarians clash with the Holy Roman Empire over Corfu . . . both of our enemies may be weakened, while we remain strong."

Jagiellon smiled. It was not a pleasant sight. There were several rotten stumps in among the huge Lithuanian's teeth. "And Valdosta may be sent there. The younger one if not the elder. I do not allow a quest for vengeance to impede my plans; only a fool concentrates on a personal vendetta when larger affairs are unresolved. But this time I could perhaps combine both. Good. I will send my new errand-boy to Constantinople."

He clapped his meaty hands. A frightened-looking slave appeared almost instantly. "Have the new man sent to me. See that horses are made ready. Captain Tcherklas must also be called. He is to accompany my servant to Odessa. The servant will need five hundred ducats, and will require suitable clothes for the imperial court in Constantinople."

The slave bowed and left at a run. He could not answer. He had no tongue any more. Jagiellon allowed his servants to retain only those portions of themselves as were useful.

"Corfu. It was a powerful place of an old faith, once," said Jagiellon speculatively.

The Count said nothing. That was wisdom. His own plotting was subtle, and the less he even thought about it . . .

The demon Chernobog could pick up thoughts. And if he was correct, then what the Black Brain knew, Jagiellon knew also. And vice versa, of course. There was a chance that events might favor his progress and his ambitions, but if they did not, he needed to keep his hands clean.

Relatively.

"Still, those days are long gone now." Jagiellon nodded to the count. "We will take these steps. We will find old shrines. The stones will have some power. We will rededicate them to our ends."

The slave returned, escorting a blond and once handsome man. Now Caesare Aldanto was gaunt. His fine golden hair hung limp about his face, matted with filth and vomit. He had plainly, by the smell, soiled himself, not just once, but often. And, by those empty eyes, this matter was of no concern to him.

Jagiellon did not seem to notice the smell, as he gave detailed, precise instructions. Caesare was to take himself to Constantinople. Letters of introduction and certain tokens of the emperor's latest pastime, were to be presented to the Emperor Alexius VI. The tokens fetched by the tongueless servant were of such a nature as to make even Mindaug blanch for a moment. Caesare did not even look discomfited when he was told to participate if the emperor so desired. He didn't even blink.

"And you'd better have him cleaned up," said Count Mindaug, when Jagiellon had finished. "He'll be noticed, else, and I doubt he'd get as far as the Greek emperor's flunkies in the condition he's in now, much less the emperor himself. He stinks."

The solid black eyes that now filled Jagiellon's sockets stared at the count. "He does?"

Jagiellon turned to Caesare. "You will see to that also, then."

Caesare nodded. Like his walk, his nod had a slightly jerky, controlled-puppet air about it. But just for a moment a madness showed in those blank eyes, a desperate, sad madness. Then that, too, was gone.

Jagiellon waved dismissively. "Go. See that Emperor Alexius engages in talks on military action with Emeric. Corfu must fall." He turned to the tongueless slave. "Has my new shaman arrived?"

The slave shook his head, fearfully. He was very efficient. Well-educated. Once he had been a prince.

"Very well," Jagiellon rumbled, only a little displeased. "Bring him to me when he appears. And see to this one. Make him fit for an emperor's company."

Count Mindaug scratched again as the servant nodded and hurried out. Lice were a small price to pay for power.

"I've gotten word from the Grand Metropolitan," the Emperor began abruptly, the moment Baron Trolliger sat down in Charles Fredrik's small audience chamber. The chamber was even smaller than the one the Holy Roman Emperor preferred in his palace in Mainz. Here in Rome, which he was visiting incognito, the Emperor had rented a minor and secluded mansion for the duration of his stay.

The servant had ushered Trolliger to a comfortable divan positioned at an angle to the Emperor's own chair. A goblet of wine had been poured for the baron, and was resting on a small table next to him. The Emperor had a goblet in hand already, but Trolliger saw that it was as yet untouched.

"Something is stirring in the Greek isles, or the Balkans," Charles Fredrik continued. "Something dark and foul. So, at least, he's being told by Eneko Lopez. By itself, the Metropolitan might think that was simply Lopez's well-known zeal at work—but his own scryers seem to agree."

"Jagiellon?"

The Emperor's heavy shoulders moved in a shrug. "Impossible to tell. Jagiellon is a likelihood, of course. Any time something dark and foul begins to move, the Grand Duke of Lithuania is probably involved. But he'll be licking his wounds still, I'd think, after the hammering he took in Venice recently—and there's always the King of Hungary to consider."

Baron Trolliger took a sip of his wine; then, rubbed his lips with the back of his hand. When the hand moved away, a slight sneer remained.

"Young Emeric? He's a puppy. A vile and vicious one, to be sure, but a puppy nonetheless. The kind of arrogant too-smart-for-his-own-good king who'll always make overly complex plans that come apart at the seams. And then his subordinates will be blamed for it, which allows the twit to come up with a new grandiose scheme."

"Get blamed—and pay the price," agreed Charles Fredrik. "Still, I think you're dismissing Emeric too lightly. Don't forget that he's got his aunt lurking in the shadows."

Trolliger's sneer shifted into a dark scowl. " 'Aunt'? I think she's his great-great-aunt, actually. If she's that young. There is something purely unnatural about that woman's lifespan—and her youthful beauty, if all reports are to be believed."

"That's my point. Elizabeth, Countess Bartholdy, traffics with very dark powers. Perhaps even the darkest. Do not underestimate her, Hans."

Trolliger inclined his head. "True enough. Still, Your Majesty, I don't see what we can do at the moment. Not with such vague information to go on."

"Neither do I. I simply wanted to alert you, because . . ."

His voice trailed off, and Trolliger winced.

"Venice again," he muttered. "I'd hoped to return with you to Mainz."

Charles Fredrik smiled sympathetically. "The Italians aren't that bad, Hans." A bit hastily—before the baron could respond with the inevitable: yes, they are!—the Emperor added: "The wine's excellent, and so is the climate, as long as you stay out of the malarial areas. And I think you'd do better to set up in Ferrara, anyway."

That mollified Trolliger, a bit. "Ferrara. Ah. Well, yes. Enrico Dell'este is almost as level-headed as a German, so long as he leaves aside any insane Italian vendettas."

The Emperor shrugged. "How many vendettas could he still be nursing? Now that he's handed Sforza the worst defeat in his career, and has his two grandsons back?"

"True enough. And I agree that Ferrara would make a better place from which I could observe whatever developments take place. Venice! That city is a conspirator's madhouse. At least the Duke of Ferrara will see to it that my identity remains a secret."

Trolliger made a last attempt to evade the prospect of miserable months spent in Italy. "Still, perhaps Manfred—"

But the Emperor was already shaking his head, smiling at the baron's effort. "Not a chance, Hans. You know I need to send Manfred and Erik off to deal with this Swedish mess. Besides, what I need here in Italy, for the moment, is an observer."

The baron grimaced. He could hardly argue the point, after all. The notion that rambunctious young Prince Manfred—even restrained by his keeper Erik Hakkonsen—would ever simply act as an "observer" was . . .

Ludicrous.

"I hate Italy," he muttered. "I'd hate it even if it wasn't inhabited by Italians."

Elizabeth, Countess Bartholdy, laughed musically. She looked like a woman who would have a musical laugh; in fact, she looked like a woman who never did, or had, anything without grace, charm, and beauty. Yet somehow, underneath all that beauty, there was . . . something else. Something old, something hungry, something that occasionally looked out of her eyes, and when it did, whoever was facing its regard generally was not seen again.

"My dear Crocell! Jagiellon, or to give it its true name, Chernobog, is an expansionist. And, compared to the power into whose territory I will inveigle him, a young upstart." She smiled, wisely, a little slyly. "Corfu is one of the old magic places. Very old, very wise, very—other."

The man standing next to her took his eyes away from the thing in the glass jar. "A risky game you're playing, Elizabeth. Chernobog is mighty, and the powers on Corfu are, as you say, very old." His middle-aged face creased into a slight smile. " 'Very old' often means 'weary'—even for such as me. Those ancient powers may not be enough to snare him. The demon's power is nothing to sneer at. And then what?"

She dimpled, exactly like a maiden who had just been given a lapdog puppy. "Corfu is a terrible place for any foreigner to try to practice magic."

Crocell's gaze came back to the thing moving restlessly in the jar. "Hence . . . this. Yes, I can see the logic. It must have been quite a struggle, to get two disparate elementals to breed."

"Indeed it was." She grimaced at the memory, as well as the thing in the jar. "Nor is their offspring here any great pleasure to have around. But when the time comes, it will serve the purpose."

Crocell gave a nod with just enough bow in it to satisfactorily acknowledge her skill. "You will use your nephew as the tool, I assume."

"Emeric is made for the purpose. My great-great-nephew is such a smart boy—and such a careless one."

Crocell shook his head, smiling again, and began walking with a stiff-legged gait toward the entry to the bathhouse. "I leave you to your machinations, Elizabeth. If nothing else, it's always a pleasure for us to watch you at work."

Countess Bartholdy followed. "Are any of you betting in my favor yet?"

Crocell's laugh was low and harsh. "Of course not. Though I will say the odds are improving. Still . . ." He paused at the entryway and looked back, examining her. "No one has ever succeeded in cheating him out of a soul, Elizabeth. Not once, in millennia, though many have tried."

Her dimples appeared again. "I will do it. Watch and see."

Crocell shrugged. "No, you will not. But it hardly matters to me, after all. And now, Countess, if I may be of service?"

He stepped aside and allowed the countess to precede him into the bathhouse.

"Yes, Crocell—and I do thank you again for offering your assistance. I'm having a bit of trouble extracting all of the blood. The veins and arteries empty well enough, but I think . . ."

Her face tight with concentration, Elizabeth studied the corpse of the virgin suspended over the bath. The bath was now half-full with red liquid. A few drops of blood were still dripping off the chin, oozing there from the great gash in the young girl's throat. "I think there's still quite a bit more resting in the internal organs. The liver, especially."

Hearing a sharp sound, she swiveled her head. "Do be a bit careful, would you? Those tiles are expensive."

"Sorry," murmured Crocell, staring down at the flooring he'd cracked. His flesh was denser and heavier than iron, and he always walked clumsily, wearing boots that might look, on close inspection, to be just a bit odd in shape. They were—more so on the inside than the outside. The feet in those boots were not human.

Crocell was helpful, as he always was dealing with such matters. He was the greatest apothecary and alchemist among the Servants, and always enjoyed the intellectual challenge of practicing his craft.

He left, then, laughing when Elizabeth offered to share the bath.

His expression did not match the laugh, however, nor the words that followed. "I have no need for it, Countess, as you well know. I am already immortal."

The last words were said a bit sadly. Long ago, Crocell had paid the price Elizabeth Bartholdy hoped to avoid.

After her bath, the countess retired to her study, with a bowl of the blood—waste not, want not, she always said. There was still another use for it, after all, a use that the bath would actually facilitate. The blood was now as much Elizabeth's as the former owner's, thanks to the magical law of contagion.

She poured it into a flat, shallow basin of black glass, and carefully added the dark liquid from two vials she removed from a rank of others on the shelves. Then she held her hands, palms down, outstretched over the surface of the basin. What she whispered would be familiar to any other magician, so long as he (or she) was not from some tradition outside of the Western Empire. All except for the last name, which would have sent some screaming for her head.

Rather insular of them, she thought.

A mist spread over the surface of the dark liquid. It rose from nothing, but swiftly sank into the surface of the blood. The liquid began to glow from within with a sullen red light. And there, after a moment, came the image of her conspirator.

Count Mindaug's face was creased with worry. "This is dangerous, Elizabeth."

The countess laughed at him. "Don't be silly. Jagiellon is practically a deaf-mute in such matters; he acknowledges no power but his own except as something to devour. He won't overhear us. Besides, I'll be brief. I received a letter from my nephew yesterday. He's clearly decided to launch his project."

Mindaug shook his head. "The idiot."

"Well, yes." Elizabeth's laugh, as always, was silvery. "What else is family good for?"

Mindaug grunted. He was hardly the one to argue the point, since his own fortune had come largely from his two brothers and three sisters. None of whom had lived more than two months after coming into their inheritance.

"He's still an idiot. I'd no more venture onto Corfu than I would . . . well." Politely, he refrained from naming the place where the Hungarian countess would most likely be making her permanent domicile, sooner or later. Elizabeth appreciated the delicacy, although she would dispute the conclusion. "However, it's good for us. I'll keep steering Jagiellon as best I can."

"Splendid. All we have to do for the moment, then, is allow others to stumble forward." Politely, she refrained from commenting on the way Mindaug was scratching himself.

It was a bitter morning. The wind whipped small flurries of snow around the hooves of the magnificent black horse. The rider seemed unaware of the chill, his entire attention focused instead on the distant prospect. From up here, he could see the dark Ionian gulf and the narrow strip of water that separated the green island from the bleak Balkan mountains. Over here, winter was arriving. Over there, it would still be a good few more weeks before the first signs of it began to show.

The rider's eyes narrowed as he studied the crescent of island, taking in every detail from Mount Pantocrator to Corfu Bay.

The shepherd-guide looked warily up at the rider. The rider was paying a lot of money for the shepherd's services. The shepherd was still wondering if he was going to live to collect.

Abruptly the tall rider turned on his guide. "When your tribes raid across there, which way do they follow?"

The shepherd held up his hands. "Lord, we are only poor shepherds, peaceful people."

"Don't lie to me," said the rider.

The shepherd looked uneasily across at the sleeping island. Memories, unpleasant memories, of certain reprisals came back to him. Of a woman he'd once thought to possess . . .

"It is true, Lord. It is not wise to attack the Corfiotes. There are many witches. And their men fight. The Venetians, too, come and burn our villages."

"Fight!" the tall rider snorted. "If things develop as I expect they will in Venice, they'll have to learn to fight or be crushed. Well, I have seen what I have come to see. And now, you will take me to Iskander Beg."

The shepherd shied, his swarthy face paling. "I do not know who you are talking about, lord."

"I have warned you once, do not lie to me. I warn you again. I will not warn you a third time." It was said with a grim certainty. "Take me to Iskander Beg."

The shepherd looked down at the stony earth. At the dry grass where he knew his body might rest in a few moments. "No, King Emeric. You can only kill me. Iskander Beg . . ." He left the sentence hanging. "I will not take you to the Lord of the Mountains. He knows you are here. If he wants to see you, he will see you."

The King of Hungary showed no surprise that the shepherd had known who he was secretly escorting. After all, the thin-browed, broken-nosed face was well known—and feared. Yes, he was a murderous killer. That in itself was nothing unusual in these mountains. But Emeric was also rumored to be a man-witch. That was why this guide had agreed to lead him, Emeric was sure, not simply the money. Emeric would leave these mountains alive.

The King of Hungary turned his horse. "He can choose. He will see me soon enough anyway. He can see me now, or see me later, on my terms."

The shepherd shrugged. "I can show you the way back now."

Across, on the green island, in a rugged glen, the stream cascaded laughingly amid the mossy rocks. In front of the grotto's opening, the piper played a melody on the simple shepherd's pipe. It was a tune as old as the mountain, and only just a little younger than the sea. Poignant and bittersweet, it echoed among the rocks and around the tiny glade between the trees. The sweet young grass was bruised by the dancing of many feet. And among the tufts were sharp-cut little hoof-marks, alongside the barefoot human prints.

Far below a shepherd whistled for his dogs. The piper did not pause in her playing to draw the hood of her cloak over the small horns set among the dark ringlets. This was a holy place. Holy, ancient and enchanted. Neither the shepherd nor his dogs would come up here. Here the old religion and old powers still held sway. The power here was like the olive roots in the mountain groves: just because they were gnarled and ancient did not mean they were weak.

Or friendly.