|

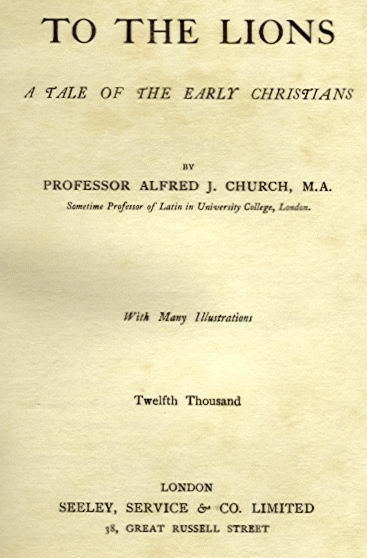

To the Lions by Alfred J. Church |

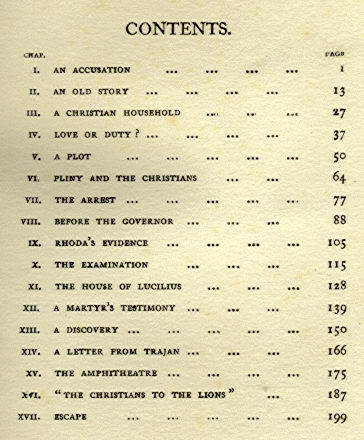

Table of Contents

An Accusation

An Old Story

A

Christian Household

Love or Duty?

A Plot

Pliny and the Christians

The Arrest

Before

the Governor

Rhoda's Evidence

The Examination

The

House of Lucilius

A

Martyr's Testimony

A Discovery

A

Letter from Trajan

The Amphitheatre

"The Christians to the

Lions"

Escape

Front Matter

|

|

Back Matter

AN ACCUSATION

[1] THE time is the early morning of an April day in the year

of Our Lord 112. So early is it that the dawn has scarcely yet begun to show in

the eastern sky. The place is a burial-ground in the outskirts of Nicæa, one of the chief towns of the Roman

Such was

a Christian church in the early part of the second century.

It must

not be supposed that even this simple building had been erected for its own use

by the Christian community. Even if it could have found the means to do so, it

would not have ventured so to attract public attention. For the Christian faith

was not one of the religions which were sanctioned by the State; and it existed

only by sufferance, or rather, we might even say, by stealth.

This

meeting-house of the Christians of Nicæa was

really the club-house of the wool-combers of that city. The wool-combers' guild

or company had, for some reason, passed to other places. Old [3] members had

died, and few or no new members had been admitted. Much of its property had

been lost by the dishonesty of a treasurer. Finally the few surviving members

had been glad to let the building to persons who were acting for the Christian

community. No questions were asked as to the purpose for which it was to be

used; but, as two or three out of the half-dozen of surviving wool-combers were

Christians, it was well understood what this purpose was. It would have been,

by the way, more exact to say "a burial club." This was the object

for which it had been founded. Its social meetings had been funeral feasts;

hence its situation in the near neighbourhood of a cemetery. This made it

particularly suitable for meetings of the Christians. Assemblies held before

dawn—for this was the custom—and close to a burial-ground, would be little

likely to be observed.

The

congregation may have numbered one hundred persons, of whom at least two-thirds

were men. There was a division between the sexes—that is to say,

the men occupied all the seats (benches of the plainest kind) on one side of

the building, and the front half of those on the other. It was easy to see

that, with a very few exceptions, they were of humble rank. Many, indeed, were

slaves. These wore frocks reaching [4] down to the knees, cut square at the

neck, and for the convenience of leaving the working arm free, having one

sleeve only. These frocks were made of coarse black or brown serge, trimmed at

the bottom with sheepskin. Two or three were sailors, clad in garments so

coarse as almost to look like mats. Among the few worshippers of superior

station was an aged man, who wore a dress then rarely seen, the Roman toga. The

narrow purple stripe with which it was edged, and the gold ring which he wore

on the forefinger of his left hand, showed that he was a knight. His order

included, as is well known, the chief capitalists of

The only

other member of the congregation whom it was necessary to mention was an

elderly man who sat immediately behind Antistius. His

dress, [5] of plain but good material, showed that he belonged to the middle

class. His name was Caius Verus.

The

semicircular end of the building was reserved for the clergy, of whom three

were present. They wore the usual dress of the free citizen of the time, a

sleeved tunic, with a cape over the shoulders that reached to the waist. The

only thing that distinguished them from the congregation was that their dress

was wholly white. One of the three was an old man; his two colleagues were

middle-aged. The three sat facing the people, with a plain table used for the

Holy Supper in front of them. On either side of the apse, as we may call it, on

the line which divided it from the main body of the building, were two reading

desks. On each a volume was laid. One of these volumes contained the Old

Testament, in the Greek version of the Septuagint, the other the New.

The

minister left his seat behind the Table, and advanced to address the people. It

was evident that his agitation was great; indeed, it was some time before he

could command his voice sufficiently to speak.

"Brothers

and sisters," he said, "I have a grave and lamentable matter to lay before you. Serious charges have been brought against

our brother [6] Verus—for brother I will yet call

him. It has been alleged against him that he has gambled, and that he has

sacrificed to idols. Caius Verus,"

he went on, "answer as one who stands in the presence of God and His

angels. Do you know the house of the merchant Sosicles?"

Verus stood up in his place. Whatever he may have felt

about the truth of the charges and the likelihood of their being proved, he did

not lose his confident air. He had stood not once or twice only in his life in

positions of greater peril than this, and he would not allow himself to be

terrified now.

"I

know it," said the accused, "as far as a man may know a house which

he enters only for purposes of business. I have had dealings with Sosicles on account of the Church, as the brethren know. He

is a heathen, but a man of substance and credit; and the moneys of the Church

have increased in his hand."

"It

is true," said the minister; "and I have often wished that it could

be otherwise. But the holy Apostle Paul tells us that if we would have no

dealings with such men, we must needs go out of the

world. But you affirm that you have not companied with him as with a

friend?"

"I

affirm it."

"Cleon, come forth!" said the minister to a [7] young

man who was sitting on one of the back benches.

Cleon was a slave from the highlands of Phrygia—not a

Greek, but with the tinge of Greek manners, which had reached by this time to

all but the most inaccessible parts of Lesser Asia. He was a new-comer. Verus scanned his face narrowly, but apparently without any

result.

"Tell

your story," said the minister; "and speak without any fear of

man."

Cleon went on in somewhat broken Greek. It is a month since

I came into the possession of the merchant Sosicles.

He bought me of the heir of the widow Areté, of

Self-possessed

as he was, the accused could not quite hide the dismay with which he listened

to this narrative. He had not noticed the new cup-bearer at Sosicles'

entertainment. He had often heard his host say that he would have no Christian

slaves: they were troublesome, and made difficulties about doing what they were

told. Accordingly, he had made sure that he was safe. He would gladly have

escaped saying the idolatrous words. His Christian belief, without being

sincere, was yet strong enough to make him shrink from committing so manifest

an offence against it. Of love for Christ he had nothing; but he certainly

feared Him a great deal more [10] than he feared Hermes. Still, when he came to

balance his scruples against the present loss of breaking with his host, they

were found the lighter of the two. So he had come to speak the words; but he

had followed them up with a sentence muttered under his breath: "Who, for

all that, is a false demon." With this he had salved his conscience, which

by this time had come to heal of its wounds with a dangerous ease.

Now he

rapidly reviewed his position, and thought that he saw a way of escape. He

spoke with an appearance of moderation and candour that did credit to his power

of acting.

"I

have a fault to confess, but it is not the grievous sin of which Cleon accuses me. It is true that I was at Sosicles' banquet. I repent me of having concealed this

from the brethren. But it is not true that I spoke the blasphemous words. What

I said was a colourable imitation of them, intended to appease the unreasonable

rage of a tipsy man. Who knows what trouble might have arisen—not to me only,

but to the whole community—if I had angered him? As for the dice-playing, I

played, indeed; but I played to humour him. I so contrived it that he won back

the greater part of what he had lost. If I gained anything, I gave the whole of

it to the poor. As [11] for the bag of money which Cleon saw me carry away, it was given to me in

payment of an account. These things I confess, because I would not hide any

thing from my brethren, and desire to make any amends that they may judge to be

fitting. Yet there is something that I would urge. Does not the holy Apostle

command that an accusation be not believed against an elder except from two or

three witnesses? If I am not an elder, yet the Church has put me in a place of

trust. Were I standing on my trial before the

unbeliever, would he condemn me on the testimony of a single slave?"

"Take

heed what you say," interrupted the minister.

"In this house there is neither bond nor free."

"It

is so," said Verus. "I spoke after the

fashion of the world. But who is this young man? Is he not a stranger, known to

you only by a letter which he brought from the elders of

He

looked round on the congregation as he spoke, and saw that his appeal had not

been without its effect. It was true that, as the minister had said, all in

that house were equal; but the difference between slave and free man was too

[12] deeply ingrained into human nature in those days to be easily forgotten.

And no one felt it more than the slaves themselves. It was they who would have

been most shocked to see a respectable merchant found guilty on the single

evidence of one of their own class. A murmur of approval ran round the

congregation; and when the minister put the question, though some did not vote

either way, the general voice was for acquittal.

Before

the minister could speak, the old knight rose in his place.

AN OLD STORY

[13] VERUS

bent on the old man the same closely scrutinising look with which he had

regarded the slave. Again he failed, it seemed, to

connect the face with any recollections in his mind. There was, as we shall

see, a dark past in his life which he was most unwilling to have dragged into

the light. But he had no reason to associate Antistius

with it, and nothing more than a vague sense of distrust haunted him, but he

felt that if the old man had anything to say against him, he would be a far

more formidable witness than the young Phrygian slave.

"You

have been in

"Yes,"

he answered; "but not for some years past."

"Nor

I," went on the old man; "nor do I want ever

to see it again. She is the mother of [14] harlots, drunken with the blood of

the saints, and with the blood of the martyrs of Jesus! But when I left it

last, seventeen years ago, I carried away with me a memorial of a deed that I

shall never forget, nor you either, if there is any

thing human in you."

The

speaker produced from the folds of his toga a small packet wrapped in a cover

of silk. Unwrapping it with reverent care, he brought

out a handkerchief stained nearly all over of a dull brownish red.

"Know

you this?" he said to Verus.

"Why

do you ask me? What have I to do with it?" answered the man, with a certain insolence in his tone. The majority in his favour

made him confident.

"Yet

you should know it, for it is a blood that was shed by your hands, though the

blow was dealt by the axes of Cæsar. If seventeen

years are enough to make you forget the martyr Flavius, yet there are those who

remember him."

It is

impossible to describe the effect which these words produced. In those days of

peril, next to his love for his God and Saviour, the strongest emotion in a

Christian's heart was his reverence for the martyrs. They were the champions

who had fought and fallen for his faith, for all that he held dearest and most

precious. He [15] could not, he thought, reverence too much their patience and

their courage. Were these not the virtues which he might at any hour be himself called on to exercise.

This

reverence had, of course, its meaner counterpart in a base and cowardly nature

such as Verus'. The man had not belief enough to make

him honest and pure; but he had enough to give him many moments of agonizing

fear. It was such a fear that overpowered him now. Any wrongdoer might tremble

when thus confronted with the visible, palpable relic of a crime which he

believed to be unknown or forgotten. But this was no ordinary wickedness. The

betrayer of a martyr was looked upon with a horror equal to the reverence which

attached itself to his victim.

Nor was

it only the scorn and hatred of his fellow-men that he had to dread. There were

awful stories on the men's lips of informers and traitors who had been

overtaken by a vengeance more terrible than any that human hands could inflict;

and these crowded upon the wretched creature's recollection. His face could not

have shown a more overpowering fear had the pit itself opened before him. The

staring eyes, the forehead and cheeks turned to a ghastly paleness and dabbled

with cold drops of sweat, proved a [16] terror that in itself was almost

punishment enough.

But the

criminal was almost forgotten in the thrill of admiring awe that went through

the whole assembly. With one impulse men and women surged up to the place where

the old knight was standing with the venerable relic in his hand. To see it

close, if it might be to press their lips to it, was their one desire. The old

man was nearly swept off his feet by the rush. The minister stepped forward,

and took him within the sanctuary at the end of the meeting-house. The habit of

reverence kept the people from pressing beyond the line which separated it from

the body of the building, and they were partially satisfied when the

handkerchief was held up for their gaze.

When

silence and quiet had been restored, Antistius told

his story.

"I

went to

"When

I reached

" 'But', he said, 'my good cousin, the Emperor, has considered

me. Happily he has been my colleague, and he has taken a hundred duties off my

hands, which would have been a grievous burden on me.' And then he went to tell

me of some [18] troubles which had arisen in the Church. A certain Verus had the charge of the pensions paid to the widows,

and of other funds devoted to the service of the poor, and he had embezzled a

large part of them. 'You see,' he went on, 'we are helpless. We cannot appeal

to the courts, as we have no standing before them; in fact, our witnesses would

not dare to come forward. For a man to own himself a Christian would be certain

death; and though one is ready for death if it comes, we must not go to meet

it. So, whether we will or no, we must deal gently with this Verus.' And he did deal gently with him. Of course, he had

to be dismissed; but he was not even asked to repay what he had taken—Flavius

positively paid the whole of the deficiency out of his own pocket. And he spoke

in the kindest way, I know, to the wretch, hoped that it would be a lesson to

him, begged him to be an honest man in the future, and even offered to lend him

money to start in business with.

"And

yet the fellow laid an information against him with

the Emperor! It would not have been enough to charge him with being a Christian;

he was accused of witchcraft, and of laying plots against the Emperor's life.

He used to mention Domitian's name in his prayers,

for he was his kinsman as well as his emperor, and they got some [19] wretched

slave to swear that he heard him mutter incantations and curses. And Domitian, who was mad with fear—as he

well might be, considering all the innocent blood that he had

shed—believed it.

"I

shall never forget what I saw in the senate-house that day. It was the last day

of the year, and Flavius was to resign his office. There sat Domitian with that dreadful face, a face of the colour of

blood, with such a savage scowl as I never saw before or since. Flavius took

the oath that he had done the duties of his office with good faith, and then

came down from his chair of office.

"In

the common course of things the senate would have been adjourned at once. But

that day the Emperor stood up. What a shudder ran through the assembly! Every

one saw that the tale of victims for that year was not yet told. The question was, whose name was to be added? Domitian

called on Regulus, a wretch who had grown gray in the trade of the informer. He rose in his place. 'I

accuse Flavius Clemens, ex-consul, of treason,' he said. Why should I weary

you, my brethren, with the wretched tale? To name a man in those days was to

condemn him. I have [20] heard it said by men who have crossed the deserts of

the South that if a beast drops sick or weary on the road, in a moment the

vultures are seen flocking to it from every quarter of the sky. Before, not one

could be seen; but scarce is the dying beast stretched on the sand, but the air

is black with their wings. So it was then. One day a man might seem not to have

an enemy; let him be accused, and on the morrow they might be numbered by

scores.

"Flavius,

as I have said, was the gentlest, kindest, most

blameless of men. But had he been the worst criminal in

"You

will say, perhaps, 'But he could not bear witness

against his master!' Ah! my friends, they had a device

to meet that difficulty. They sold him first, and, mark you, without his

master's consent, to the State. Then he could give evidence, and the law not be broken. Then this villain Verus

came forward. He told the same story, and with this addition, that he had been

bribed to keep the secret, and he brought out the letter in which Flavius had

offered him the money, as I have told you. Kind as ever, the Consul had written

thus: 'We will bury this matter in [21] silence.

Meanwhile you shall not want means for your future support. Flaccus

the banker shall pay you 100,000 sesterces [about

£1,000].'

"Then

senator after senator rose and repeated something that they had heard him say,

or had heard said of him—for no evidence was refused in that court. At last one

Opimius stood up. 'Lord Cæsar,'

he said, 'and Conscript Fathers, of the chief of the crimes of Flavius no

mention has been made. I accuse him of the detestable superstition of the

Christians.'

" 'Answer for yourself,' said the Emperor, turning to

the accused.

"He

stood up. Commonly, I was told, he was a faltering speaker, but that day his

words came clear and without hindrance. We know, my brethren, Who was speaking by his lips. He spoke briefly and

disdainfully of the other charges, utterly breaking down the evidence, as any

other court on earth but that would have held. Then he went on, 'But as to what

Opimius has called "the detestable superstition

of the Christians," I confess it, affirming at the same time that this

same superstition has made me more loyal to all duties, public or private, of a

citizen of Rome. I appeal to Cæsar, who hath

known me from my boyhood, as one kinsman knows another, and who, being aware of

my belief, conferred upon [22] me this dignity of the Consulship, which is next

only to his own majesty. I appeal to Cæsar

whether this be not so.'

"He

turned to Domitian as he spoke. That unchanging flush

upon the tyrant's face fortified him, as I have heard it said, against shame.

But he kept his eyes fixed upon the ground, and for a while he was silent. Then

he said, 'I leave the case of Flavius Clemens to the judgment of the fathers.'

"You

will ask, 'Did no one rise to speak for him?' I did see one half-rise from his

seat. They told me afterwards that it was one Cornelius Tacitus,

a famous writer, but his friends that were sitting by caught his gown and

dragged him back, and he was silent. And indeed, speech would have served no

purpose but to involve him in the ruin of the accused.

"Then

the Emperor spoke again, 'We postpone this matter till to-morrow.' Then turning

to the lictors—

" 'Lictors,' he said,

'conduct Flavius Clemens to his home. See that you have him ready to produce

when he shall be required of you.'

"This,

you will understand, was what was counted mercy in those days. A man not

condemned was allowed the opportunity of putting an end to his own life. That

saved his property for [23] his family. In the evening I went to Flavius's

house. He was surrounded by kinsfolk and friends. With one voice they were

urging him to kill himself. Even his wife—she was not a Christian, you should

know—joined her entreaties to theirs. Perhaps she thought of the money, and it

was hard to choose beggary instead of wealth; certainly she thought of the

disgrace. Were she and her children to be the widow and orphans of a criminal

or an ex-consul?

"He

never wavered for an instant. 'When my Lord offers me

the crown of martyrdom,' he said, 'shall I put it from me?' That was his one

answer; and though before he had been always yielding and weak of will, he did

not flinch a hair's-breadth from this purpose.

"That

night, I was told, he slept as calmly as a child. The next day he was taken

again to the Senate, and condemned. But I heard that at least half of the

senators had the grace to absent themselves. One favour the Emperor granted to

him, as a kinsman; he might choose the manner and place of his death. He chose

death by beheading, and the third milestone on the road to

"What

answer you to these charges?" said the minister to Verus.

He said

nothing; and his silence itself was a confession.

Still it

would have ill become the Church to act in haste. Antistius

was asked to give proofs of the identity of the Verus

who was present that day with the Verus who had

brought about the death of Clemens. The old man told how his suspicions had

been first aroused; how a number of circumstances, trifling in themselves had turned this suspicion into certainly. And he

then indicated, though only in outline, his discoveries—that Verus had been following again the same dishonest practices

that had brought him into disgrace at

The

accused was still silent.

Then the

minister addressed him:—"Verus, you have heard

what has been witnessed against you. We do not repent that you were acquitted

of the first charges. Be they true or no—and what we have since heard inclines

us to believe them—they were not rightly proved. God forbid that the Church

should be less scrupulous of [25] justice than the tribunals of the unbeliever;

but to the accusations of Antistius you yourself

oppose no denial. Therefore hear the sentence of the Church.

"I

have thought whether, after the example of the holy Apostle Paul, I should

deliver you over to Satan for the destruction of the flesh. I do not doubt

either of my power or of your guilt; yet I shrink from such severity. Therefore

I simply sever you from the Communion of the Church. Repent of your sin, for

God gives you, in His mercy, a place for repentance. Make restitution for aught

in which you have wronged your brethren, or them that are without. And now

depart!"

The

congregation left a wide space, as if to avoid even the chance of touching the

garment of the guilty man, as he hurried, with his head bent downwards to the

door.

When he

had gone, the minister addressed the congregation.

"Brothers

and sisters," he said, "I cannot doubt but that we shall be soon

called to resist unto blood. There are signs that grow plainer every day, that

the rulers of this world are gathering themselves together against Christ and

His Church. It was but yesterday that I received certain news of that of which

we had before heard rumours, to [26] wit, that the holy Ignatius of Antioch

suffered at Rome, being thrown to the wild beasts by command of the Emperor.

But the fury that begins at

Some

words of advice about smaller matters connected with the management of the

Church affairs followed this address. He then pronounced a blessing, and the

congregation dispersed.

A CHRISTIAN HOUSEHOLD

[27] WE will follow one party of worshipers to their own

home, a farmhouse lying about a mile further from the city than the chapel

which has just been described. This party consists of four persons, a husband

and wife, and two daughters.

The head

of this little family is a man who may perhaps count seventy summers. But

though seventy years commonly mean much more in the East than they do in our

more temperate climate, he shows few signs of age, beyond the white hair,

itself long and abundant, which may be seen under his broad-brimmed hat. His

tread is firm, his figure erect, his cheek ruddy with health, his eyes full of

fire; yet he had seen much service, of one kind or another, during these

threescore years and ten. Bion, for that was the

veteran's name, was a Syrian by birth. He had followed Antiochus, son of the

tributary king who ruled part of [28]

Of

course this effort failed. If success had been possible in this way the Romans

would have achieved it long before. Scarcely a third of the Syrian contingent

came back alive from the forlorn hope to which they had been led. Bion was one of the survivors, but he was desperately

wounded, and had not recovered in time to take part in the final assault. He

did not lose, indeed, either pay or promotion. Before he was five-and-twenty he

was commander-in-chief of the army which the Syrian king was permitted to

maintain.

This was

a sufficiently dignified post, and his pay, coming as it did from what was

notoriously the best furnished treasury in

Again

his reckless valour brought him promotion; and his promotion brought him

enemies. An arrow which certainly could not have come from any but his own men,

missed him only by a hair's-breadth; two nights afterwards, the cords of his

tent were cut, and he narrowly escaped the dagger which was driven several

times through the canvas before he could extricate himself from the ruins; and

it was nothing but a vague feeling of suspicion, for which he could not

account, that kept him from draining a wine-cup which had been poisoned for his

benefit. These were hints that it was well to take. He left the camp without

saying a word to any one, and made the best of his way out of

The

difficulty was where to go. The world in those days consisted of

And now came the strange incident that was to change the course of Bion's future life. The two were watching the road that ran

from

The

rider dismounted with an agility which no one would have expected from so old a

man, followed him, and caught him by the cloak. "Listen to me, my

son," he said. "Four years since, I left you in the charge of Polydorus of Smyrna. At the end of two years, when I had

finished my visiting of the churches of

"Then

I went out to seek you. For if I had trusted it to an

unfaithful steward, I should have myself to answer for it to my Lord.

But now, thanks to our Father and His Christ, I have found it again. And you,

my son, will surely not take it from me."

[32]

This good shepherd, who had thus sought and found his wandering sheep upon the

hills, was the Apostle St. John. The persuasiveness of this constraining love

was such as no one could resist. Before he had finished his appeal the young

man was sobbing at his feet. The three returned to

The

Apostle was a man of no small influence in

Meanwhile

Bion had been listening with a heart disposed to

conviction to the instructions of [33]

No more

devout and earnest soul was to be found among the converts than Bion. The fiery temper which he shared with the teacher who

had brought him to Christ was tamed rather than broken. He had found, too,

during his sojourn at

One of

the most trusted lay-helpers of the Church was a devout centurion, who had

served under Titus at the siege of

But Bion found in Manilius' house a

more powerful attraction than friendship. This was the centurion's adopted

daughter, Rhoda. Manilius had found her, then a girl

of some seven years old, in a burning house on that terrible day when the

Anxiety

for his child mastered the Jew's hatred of foreigners. In broken Latin he

besought Manilius to be good to his daughter. It was

a strange responsibility for a lazy and somewhat reckless soldier, but it

seemed to sober him in an instant. He found his Tribune, and obtained

permission to take his young charge to the camp. From thence she was

transferred as soon as possible to the house of a merchant of his acquaintance at

Cæsarea.

No spoil

that he could have carried off from the sack of

When the

rewards for services in the great siege were distributed, he received a

permanent appointment at

Rhoda

was now a beautiful young woman of two-and-twenty; but no suitor had hitherto

touched her heart. Bion, in the full strength of his

matured manhood, for he was now close upon the borders of forty, with the

double romance of his strange conversion and his old life of adventure, took it

by storm. The lovers were married on the day after his baptism, and took

possession of the Bithynian farm before the end of the year.

|

|

Rhoda's

story has been given in the story of her husband. She was a woman of a

character gentle yet firm, who never seemed to assert herself, whom a casual observer

might even suppose to be of a yielding temper, but who was absolutely

inflexible when any question of right or wrong, or of the faith which she clung

to with a passionate earnestness of conviction was concerned.

The two

girls, Rhoda and Cleoné, were singularly alike

in figure and face, and singularly different in character. They were twins, and

they had all the mutual affection, one might almost say, the identity of

feeling, which is sometimes seen, a sight as beautiful as it is strange, in

those who are so related. Rhoda was the elder, [36] and the ruling spirit of

the two. This superior strength of will might be traced by a shrewd observer in

the girl's face. To a casual glance the sisters seemed so

exactly alike as to defy distinction. But those who knew them well never

confounded them together. The dark chestnut hair and violet eyes, rare beauties

under that Southern sky, the delicately rounded cheeks, with their wild-rose

tinge of colour, the line of forehead and exquisitely chiselled nose, modified

by the faintest curve from the severely straight classical outline, were to be

seen in both. But Rhoda's lips were firmly compressed; Cleoné's

were parted in a faint smile; and the gaze of Rhoda's eyes had a directness

which her sister's never showed. Rhoda's nature was of the stuff of which

saints are made; Cleoné's was rather that

which gives peace and sunshine to happy homes. Hitherto the quiet in which the

two lives had been passed had given little to occasion anything like a

divergence of will. In the small questions that occurred in daily affairs Cleoné had followed without hesitation the lead of

her sister. A time was now at hand which was to apply to their affection and to

Rhoda's influence a severe test.

LOVE OR DUTY?

[37] THE two sisters, Rhoda and Cleoné,

did not lack admirers. Maidens so fair and gracious would have attracted

suitors even had they been portionless. But it was

well known that they would bring handsome dowries with them, for Bion's farm had prospered under his hands, while Bion's wife had inherited the savings which her adopting

father, the centurion Manilius, had made from his pay

and prize-money.

But

Rhoda's admirers found it impossible to get beyond admiration. In those early

days of Christianity there were no vows of celibacy for men or women; though,

indeed, the feelings and thoughts that led to them were rapidly growing up. Yet

no cloistered nun of after times could have been more absolutely shut out from

all thoughts of love and marriage than this daughter of a Bithynian farmer. She

did not affect any- [38] thing like seclusion, or seek to stand aloof from the

business and even the little pleasures of daily life. She took her part in the

work of the farm. No fingers milked the cows or made the butter more deftly

than hers. In the harvest field she would follow the reapers, and bind the

sheaves more untiringly and more skillfully than any,

except Cleoné. When the vintage came round,

and the purple and amber grapes were plucked by the women for the men to tread

in the vats, no one filled her baskets more quickly than Rhoda. And if a weakly

calf, or lamb, or an early brood of chickens, hatched before the frosts were

fairly gone, wanted care, there was no one who could give it so efficiently and

tenderly as Rhoda. In fact, it was her vocation from her cradle to serve

others. Every good woman has such a vocation in her degree, but some embrace it

with a devotion that leaves no room for any personal ties. Rhoda was one of

these rare souls; and the boldest lover soon found that she was not for him,

and, indeed, had no care for any earthly suit. She never needed to repulse an

admirer. A very short time sufficed to show that she was absolutely

unapproachable; and she went untroubled on her way, followed by something of

the awe which might be felt for an angel come down from heaven.

[39] It

was natural, of course, that her first thought should be to serve the community

of believers to which she belonged. And there was a way in which this desire

could be fulfilled. The early church had the practice, lately revived among

ourselves, of calling devout women to the office of deaconess, and of thus

making a regular use of their zeal. The need of such helpers in the ministry

was especially great when the Greek habits of life prevailed, and women were in

a large measure secluded from society. They wanted helpers and advisers of

their own sex who might go where men would not have been admitted. Such a

helper the

Next to

her own feeling of devotion, Rhoda's strongest desire was to make her sister a

sharer in her work. Nothing could have made her draw back, but the thought of

not having Cleoné by her side was

inexpressibly painful to her, and she banished it with all the force of her

resolute will. Her best and truest course would have been to recognise the

difference between her sister and herself, of which, indeed, she could not fail

to have some knowledge, to acknowledge that Cleoné

was made for the duties of happiness and home, and to crush down all the

feelings and wishes in her heart that helped to hide this from her. But, in

common with many great natures, she had, to use a common phrase, the defects of

her good qualities. She said to herself, "I am called to serve my Lord;

this service is the highest aim in life, the most perfect happiness that I can

enjoy, [41] and what can I do better for the sister who is like a part of my

soul than to bring her to share in it? Shall I not be doing well if I can bring

two hearts instead of one to Him?"

Cleoné would have yielded with scarcely a struggle to the

strong will of her sister—for she was in her way not less devout—if it had not

been for another influence. She had found among her suitors one to whose

affections her own went out in answer.

Clitus was a Greek, an Athenian by birth, who had come to

Clitus turned away in profound discontent. Then it occurred

to him, "Can I find what I want elsewhere? There is Bion

the Golden-Mouth lecturing at

In the

afternoon of the day following the assem- [45] bly described in the first chapter, the young Roman had

found his way to the farm by help of one of the excuses which lovers are never

at a loss to invent. Possibly it was not an accident that his coming was timed

for an hour at which Rhoda would be busy with some errand of mercy, for Rhoda

viewed the young man as a formidable opponent, and, for all her unworldliness, was clever enough to prevent any private

interview between him and her sister. The elder Rhoda was busy with her

household cares; Cleoné was helping her father

in the vineyard. He was pruning—a delicate task, which he was unwilling to

trust to any hands but his own; she followed him along the rows, tying up to

their supports the shoots which were left to bear the vintage of the year. It

was here that Clitus found her, and as Bion was inclined to favour his suit, no place could have

suited him better. If we listen awhile to their talk, we shall see how matters

stood between them. Clitus was in

high spirits.

|

|

"Give

me joy, Cleoné," he said; "the

letter from the Emperor arrived this morning, and it grants the Governor's

request. I am to have the Roman citizenship; and now everything is open to

me."

The girl

could not refuse her sympathies to his manifest delight; but her mind was

somewhat sad, [46] and it was with a forced gaiety that she answered,

"Well, my lord—for you will soon be one of the lords of us poor

provincials—how shall we speak to you? What Roman name shall you be pleased to

adopt? Shall you be a Julius Cæsar or a Tullius Cicero?"

"To

you, Cleoné," said the young man, "I

shall always be Clitus, the name under which I had

the happiness to know you. But, seriously, the Governor is kind enough to let

me take his own family name, and I shall be Quintus Cæcilius."

"And

when do you leave us for

"Leave

you? for

"But

the career—in this poor place there is nothing to satisfy you. You said that

all things were now open to you, and where are 'all things' to be found, but at

"You

misunderstand me—you wrong me, Cleoné. I have

no such ambition as you seem to think. I desire nothing better than to spend

the rest of my days here, if I can but find here the thing that I want. I did

but mean that no road by which I may find it well to travel will be shut to me

when I am a citizen of

The girl

was silent. She had seen from the first, with a woman's quick apprehension of

such things, that there was a serious purpose in the young Greek's manner, and

she had tried, as women will try, even when they are not face to face with such

perplexities as were troubling poor Cleoné, to

put off the crisis.

Clitus went on: "I am to have the government business

as a notary in the province. The Governor promises that other things will

follow. But I am afraid this does not interest you."

"I

am sure," answered the girl, "we all feel the greatest interest in

you."

"But

you, Cleoné, you!" cried the young man,

and he caught her hand in his as he spoke. "You know that this is my

ambition: to have something which I can ask you to share. I came to tell you

that it seems to be within my reach, and you ask me when I am going to

Poor Cleoné was in a sad strait. The struggle between

love and duty is often a hard one; but at least the issue is clear, and a loyal

heart crushes down its pain, and chooses the better course. But

here there seemed to be love on both sides, and [48] duty on both sides.

Which was she to choose? She knew that Clitus loved

her, and though she had never looked quite closely and steadfastly into her own

heart, she felt that she loved him. And he was worthy, too. Any woman might be

proud of him. Why should she not do as her mother had done before her, and give

herself to a good man who loved her? There was love and there was duty here.

But then, on the other side, there was the Church, its claim upon her, the work

that lay ready for her hand—and Rhoda, who was her second self, from whom she

had never had a thought apart, whose love had been the better half of her life

ever since she could remember anything. It was a sore perplexity in which she

was entangled.

She

stood silent. But her silence was eloquent. Clitus,

though he was no confident lover, saw that it was not her indifference that he

had to fear. If he had been no more to her than other men, she could easily

have found words—kind, doubtless, but plain and decisive enough—in which to bid

him go. She had even left her hand in his. She was scarcely conscious of it, so

full was her mind of the struggle; but consciousness would have come quickly

enough if his touch had been repugnant to her.

At last

she spoke: "Oh, Clitus, this is not a [49] time

for such things as you talk of. Remember what the elder said the other day.

There is danger at hand, and we must be ready to meet it. Would it be right to

hamper ourselves with things of this world? Does not the holy Apostle Paul tell

that they who marry——"

She

paused, blushing crimson when she remembered that her lover, though his meaning

was plain enough, had not gone as far as speaking of marriage.

"Ah!

if you were only my wife," cried Clitus, "I should fear nothing.

"Has

he not said," she went on, "that they who marry shall have trouble in

the flesh? And, when I might be comforting and strengthening others, to have to

think of myself! O, Clitus, I feel that I am called

to other things. Rhoda and I are not as other women; she tells me so, and she

is always right. I could not go against her."

Perhaps

it was as well that just at that moment, Bion, who

had finished his work for the time among the vines, advanced with outstretched

hands to greet the guest. It was a relief to both to have the interruption.

A PLOT

[50] ON the evening of the day when Clitus

and Cleoné held their conversation among the

vines, as described in the last chapter, another conversation, which was to

have no little influence on their fate, was going on. The place was a

wine-shop, kept by a certain Theron, in the outskirts

of Nicæa, and not far from the Christian

meeting-house. Theron's customers were, for the most

part, of the artisan class. But he kept a room reserved for his few patrons

that were of a higher rank. In this room three persons were sitting at a

citron-wood table, one of the innkeeper's most cherished possessions, which

only favoured customers were permitted to see uncovered. A flagon, which could

not have held less than two gallons stood in the middle of the table. It was

about half full of the potent wine from

One of

the three is already known to us. This is Verus, the

unworthy member whose banishment from the Christian community has been

described. The second, to whom, it may be observed, his companions pay a

certain respect, is an elderly man, in the ordinary dress of a well-to-do

merchant. There is a certain air of intelligence in his face. But the keen,

hungry look of the eyes, the pinched nose, the thin, bloodless lips, tightly

closed, but sometimes parting in a smile that never reaches the eyes, give it a

sinister look. Lucilius—for this was his name—was a

man of good birth and education, but he had given up all his thoughts to

money-making, and the tyrant passion had set the mark of his servitude on his

face.

The

third is a professional soothsayer or fortune-teller. The fortune-teller of

to-day commonly exercises his art by means of a pack of cards, while he

sometimes consults a tattered book of dreams, or even professes to gather his

knowledge of the future from the motions of the planets. Cards were not then

invented; dream-interpreting and star-reading were not held in very great

repute. Our soothsayer practised the curious art of discovering the future by

the signs that might be discerned in the entrails of animals. My [52] readers

would think it tedious were I to give them the details of this system. Let it

suffice to say that the liver was held to carry most meaning in its appearance.

If the proper top to it were wanting, something terrible was sure to happen.

There were lines of life in it, and lines of wealth. Each of the four

"fibres" into which it was divided had its own province. From this

you could discern perils by water, from that perils by

fire; a third warned you of losses in business, a fourth gave you hopes of a

legacy. This was the art, then, which the third of the three guests professed.

He called himself Arruns, but this was not his real

name. Arruns is Etruscan, whilst the man was a

Sicilian, who, after trying almost everything for a livelihood, had settled

down as an haruspex in

Nicæa. But the Etruscans were famous over all

the Roman world as the inventors of the soothsaying art, and professors of it

found an Etruscan name as useful as singers sometimes find one that is borrowed

from Italy, or French teachers a supposed birthplace in Paris. Arruns, if he had little of the Etruscan about him in his

language, which was Latin of the rudest kind, spoken in a broad Greek accent,

had at least the corpulence for which the foretellers of the future [53] were

proverbial. His small dull eyes, sometimes lit up with a little spark of greed

or cunning, his thick sensual lips, and heavy bloated cheeks, flushed with

habitual potations, showed how the animal predominated in him.

He was

now holding forth on his grievances in a loud, harsh voice, which he did not

forget to refresh with frequent draughts of Tmolian

wine.

"It

is monstrous, this neglect of the gods! It must bring a curse upon the country.

There will be nothing left sacred soon. Who can suppose that if men do not care

for the gods, they will go on caring for each other? Children will not honour

their parents, nor parents love their children. The

sanctity of marriage, the rights of property, everything will disappear, if

these atheists are suffered to go unpunished, while they spread abroad their

pernicious doctrines."

"Your

zeal does you credit," interrupted Lucilius,

with a slight cynical smile. "But we all know that Arruns

is careful of all that concerns the sacredness of the home."

Arruns was a notoriously ill-conducted fellow, whose life

was a scandal to the better behaved, not to say the more pious of the heathen.

His wife had long since left him in disgust, and was supporting herself as a

nurse. His children he had turned out of doors. The shaft did not wound [54]

him very deeply, but he took the hint and became more practical.

"Look

at the temples," he went on; "the court-yards are grass-grown. Day

after day not a worshipper comes near them. To see smoke going from the altars

is as rare as to see snow in summer. And when a man does bring a beast, 'tis

some paltry, half-starved creature: a scabby sheep, or a worn-out bullock from

the plough, which are not good enough for the butcher's knife, let alone the

priest's hatchet. And as often as not, when there is a decent sacrifice, they

do not call me in. They grudge me my ten drachmas—for I have had to cut down

the fee to ten. 'What should a calf or a sheep's liver have to tell us about

the future?' they say. What monstrous impiety! What a flagrant contradiction of

all history! Did not Galba's haruspex,

on the very day of his death, warn him that he was in danger from an intimate

friend? and did not Otho,

who was such a friend, kill him within two hours afterwards?"

"Yes,"

said Lucilius, a little peremptorily, "we know

all about these examples and instances. But go on to your own grievances."

"Well,

to put the matter plainly, it is simple starvation to me. Twice, thrice last

week I had to live on beans and bread. Ten years ago there did not a day pass

without two or three sacrifices. [55] I had my pick of good things—beef,

mutton, lamb, veal, pork, every day; and now I am positively thankful for a

rank piece of goat's flesh, that once I would not have given to my slave. Oh! it is awful; there must be a judgment from the gods on such

impiety."

"One

would hardly think, from your looks, my Arruns,"

said Lucilius, "that things

were quite so bad as you say. But, tell me, what do you suppose to be the cause

of this impious neglect of the gods, and this indifference to the future?"

"The

Christians, of course," said Arruns; "the

Christians."

"But,"

interrupted Lucilius, "they can be scarcely

numerous enough to make much difference, and I am told that they are mostly

poor people, and even slaves; so that they could hardly, in any case, be

clients of yours."

"My

good lord," said Arruns, "it is not so much

the Christians themselves; it is the example they set. People say to

themselves: 'These seem to be very decent, honest sort

of fellows; they never murder or rob; they are very kind to the sick and poor;

we can always be safe in having dealings with them; and they seem to be

tolerably prosperous too. And yet they never go inside a temple, nor offer so

much as a lamb to the gods.' What could be worse than that? They do ten [56]

times more harm than if they were so many murderers and thieves. A good citizen

who neglects the gods is a most mischievous person. There is sure to be a

number of people who imitate him so far. It is the Christians who are at the

bottom of all this trouble."

"But

what do you want me to do?" said Lucilius.

"Grant that what you say is true, still I see no reason for interfering. I

have two or three tenants who are said to be Christians, and they are honest

and industrious fellows who always pay me my rent to the day. Why should I

trouble them?"

"Pardon

me, sir," interrupted Verus, who had as yet

taken no part in the conversation. "Pardon me if I remind you that there

is something more to be said. The association of the Christians is an unlawful

society."

"Of

course it is," cried Lucilius; "we all know

that; though you, my dear Verus, seem to have been a

long time finding it out, if, as I understand, you have been acting as their

treasurer."

"I

have but lately discovered their true character," said Verus.

"When I did, I hastened to leave them."

"Ah!"

said Lucilius, with a sneer, "that must have

been at the very time when they examined your accounts. Do you know that people

have [57] been saying that they, too, made some discoveries?"

Verus, who would have given a great deal to be able to stab

the speaker, forced his features into a sickly smile. "You are pleased to

jest, honourable sir," he said. "But these Christians are not quite

so insignificant or so poor as you think. There is the

old knight, Antistius. No one would suppose that he

was a rich man. He drinks wine that cannot cost more than a denarius

a gallon, and very little of that; but we know what he

gives away in alms. It is not only here that he gives. His money goes to

"And

stick there sometimes, I have heard," retorted the other, whose passion

for saying bitter things was sometimes too strong for his prudence, and even

for his avarice. "But what does that matter to me? What do I care for the

way in which an old fool and his money are parted? It does not concern me if he

feeds all the beggars and cripples in the Empire."

"You

forget sir," returned Verus, "that if Antistius is convicted of belonging to an unlawful

society—and there can be no doubt that the community of Christians is such a

society—his goods [58] are confiscated to the Emperor's purse, and that those

who assist the cause of justice will have their share."

There

was a sudden change in Lucilius's careless,

supercilious manner, though he did his best not to seem too eager.

"Ah!"

he said, "there may be something in that, though I should not particularly

like a business of that kind."

"Don't

suppose, sir," went on Verus, "that there

are not others besides Antistius. There are plenty

who are worth looking after. Bion the farmer is

wealthy, though one would hardly think it. And there are others who are

entangled in this business. You would hardly believe me, if I were to tell you

their names. And then it is not only here, it is all through the province that

you may find them. I have all the threads in my hand, and I could make a very

pretty unravelling if I chose."

"What,

then, do you propose?" asked Lucilius.

"That we should lay information to the Governor."

"Will

he act? He is all for being philosophic and tolerant."

"He

cannot choose but act. The Emperor's orders are stringent. He is very strict

about these secret societies. Did you not hear about the [59] fire-brigade that

the people of

[60] At Verus's suggestion, Theron, the

innkeeper, was called into the council. He, of course, had a very bad opinion

of the Christians. "They are a very poor, mean-spirited lot," he

said; "if they had their way there would not be a tavern open in the

Empire. I never see one of them inside my doors. Sometimes, when I have a late

company here, I have seen them on their way to their meeting-place, one of the guildhouses in the cemetery here. They are a shabby lot,

for the most part—half of them slaves, I should think. I suspect an out-door

man of my own of being one of them. He never drinks, or gambles, or fights. I

always suspect there is something wrong with a young fellow when he goes on

like that. Yes, I should very much like to see the whole business put a stop

to. If it is not, the world will soon be no place for an honest man to live

in."

A plan

of action was agreed upon. A number of memorials were to be presented to the

Governor, praying him to interfere with a certain unlawful society, bearing the

name of Christians, or followers of Jesus, that was accustomed to meet in the neighborhood of Nicæa. Lucilius, Verus, and Arruns were each to send in such a document, and were to

get others sent in by their friends. A number of anonymous memorials in various

hand- [61] writings were also to be prepared. The more there were, the more likely was the Governor to be impressed.

When the

party was separating, Arruns tried to do a little

stroke of business on his own account. "This is an important

undertaking," he said, in his most professional tone, to Lucilius. "Don't you think that it would be well to

consult the gods?"

"My

Arruns," said Lucilius,

who had no idea of spending his money in any such way, "when I make an

offering, I prefer that it should be a thank-offering. When we have done

something, I shall not be ungrateful."

The

soothsayer was not going to let himself be baffled. If

he could get nothing out of the cupidity of Lucilius,

he might be more successful in working on the fears of Verus.

"It

would have an excellent effect, my dear Verus,"

he said, "if people could see some proof of your piety. They know that you

have been mixed up with these Christians, and they don't all know that you have

come out from among them. If there should be anything like a rising of the

people—there was one in

Verus, who, if he had not learnt to believe Christianity,

must have at least learned thoroughly to disbelieve the whole Pagan system,

heard the suggestion with very little fervour, but felt too uneasy about his

position to reject it. He knew that he had compromised himself, and that the

danger which Arruns had pictured was not completely

imaginary.

"There

may be something in what you suggest," he said, after a pause. "Perhaps

a lamb to Jupiter or Apollo——"

"A lamb!" interrupted

Arruns, who was not disposed to be satisfied with so

paltry an offering. "A lamb! The

whole country would cry shame upon you. It ought to be nothing less than a

hecatomb."

"A

hecatomb!" cried Verus, "what are you

talking about? Am I the Emperor, that you should suggest such a thing?"

"Well,"

returned the other, "a hecatomb [63] might, perhaps, be a little

ostentatious for a man in your position. But I assure you that nothing less

than a 'swine, sheep, and bull' sacrifice would be acceptable. It must be

something a little out of the common, for yours is not a common case."

"Well,

let it be so," said Verus, "only it must be

done cheaply. No gilding of the bulls horns or expensive flowers; I really

cannot afford it."

"Leave

it to me," answered Arruns. "I will spare

your pocket."

With

this they separated, the soothsayer chuckling over his success, and the

prospect of a plenty which he had not enjoyed for some months, Verus ruefully calculating how many gold pieces the three

animals, with the ornaments and the temple fees, would cost him.

PLINY AND THE CHRISTIANS

[64] CAIUS

PLINIUS CAECILIUS SECUNDUS, commonly

known to posterity as the Younger Pliny, has just finished his day's work as Proprætor—that is to say, Governor—of the Roman

The room

shows evident signs of the occupation of a man of culture. Though it is his

official apartment, and he has his study elsewhere, it has something of the

look of a library. A little bookcase, elegantly made

of ivory and ebony, stands [65] close to his official chair. Half a dozen

rolls—for such were the volumes of those days—are within reach of his hand. He

can refresh himself with a few minutes' reading of on or other of them, when

the tedium of his official duties becomes more than he can bear; using a

writer's privilege, we can see that Homer is one of the six, and Virgil

another. The wall facing him is covered with a huge map of the province; and

most of the available space elsewhere is occupied with documents, plans of

public buildings, and other matters relating to the details of government; but

room has been found for busts of eminent writers, for some tasteful little

pieces of Corinthian ware, and for two or three statuettes of Parian marble. At a table in the corner a secretary is busy

with his pen; but were we to look over his shoulder we should see that he is

not occupied with the answer to a petition or with a report to the Emperor, but

with the fair copy of a poem which the Governor has found time to dictate to

him in the course of the day.

Pliny

has just risen from his seat, after swallowing a

cordial which his body physician has concocted for him, when the soldier who

kept the door announced a visitor—"Cornelius Tacitus,

for his Excellency the Governor." Pliny received the [66] new-comer, who,

indeed, had been his guest for several days, with enthusiasm.

"You

were never more welcome, my Tacitus," he cried.

"Either I am in worse trim for business than usual, or the business of the

day has been extraordinarily tiresome. In the first place, everything that they

do here seems to be blundered over. In one town they build an aqueduct at the

cost of I don't know how many millions of sesterces, and one of the arches tumbles down. Then, in Nicæa here, they have been spending millions more on

a theatre, and, lo and behold ! the

walls begin to sink and crack, for the wise people have laid the foundation in

a marsh. Then everybody seems to want something. The number of people, for

instance, who want to be made Roman citizens is beyond

belief. If

The

Governor handed to his friend two or three small parchment rolls, which he took

from a greater number that were lying upon a table. As

Tacitus read them, his look became grave, and even

troubled.

"What

am I to do in this matter?" said the Governor, after a short pause.

"For the last two or three days these things have been positively crowding

in upon me. You don't see there more than half that I have had. They all run in

the same style: I could fancy that a good many are in the same handwriting.

'The most excellent Governor is hereby informed that there is a secret society,

calling itself by the name of Christus, that holds

illegal meetings in the neighbourhood of this city; that the members thereof

are guilty of many offences against the majesty of the Emperor, as well as of

impiety to the gods;' and then there follows a long list of names of these same

members. Some of these names I recognize, and, curiously enough, there is not

one against which I know any harm. Can you tell me anything about this secret

society which calls itself by the name of Christus?"

"Yes,"

answered Tacitus; "it is more than fifty years

ago since I first heard of them, and I have always watched them with a good

deal of interest since. It was in the eleventh year of Nero—you could only have

been an infant then, but it was the time when more than half of

"I

remember it," interrupted Pliny, "though I was only three years old;

but one does not forget [68] being woke up in the middle of the night because

the house was on fire, as I was."

Tacitus went on: "Well, I shall never forget that

dreadful time. The fire was bad enough, but the horrors that followed were

worse. People, you know, began to whisper that the Emperor himself had had the

city set on fire, because he wanted to build it again on a better plan. Whether

he did it or not, he was capable of it; and it is certain that he behaved as if

he were delighted with what had happened, looking on at the fire, for instance,

and singing some silly verses of his own about the burning of

"But,"

said the Governor, "have you ever made out that there is anything wicked

or harmful in this superstition of theirs? I have heard strange stories of

their doings: that they mix the blood of children with their sacrifices,

that they indulge in disgraceful licence, and so forth. Do you believe

that there is anything in these reports?"

"To

speak frankly," replied Tacitus, "I do not.

On the contrary, I believe that they are a singularly innocent and harmless set

of people; that they neither murder nor steal; and that if all the world were

like them our guards and soldiers would have very little to do."

"Yet," said Plinius, "you seem

to speak of them in a somewhat hostile tone. If they are so blameless

they cannot fail to be good citizens."

"No,

this is precisely what they are not," was Tacitus'

answer after a few moments' pause. "I [70] take it that obedience is the

foundation of our commonwealth, obedience to the Emperor now, as it once was to

the Senate and people. No man must set his own will or his own belief above

obedience. If he does, he takes away the foundation. Tell one of these

Christians to throw a pinch of incense on an alter,

and he will refuse. Not the Emperor himself could make him do it. The pinch of

incense may be nothing. Neither the State nor any single soul in it may be one

whit the worse for its not being thrown; but it is an intolerable thing that

any citizen should take it upon himself to say whether he will or will not do

it. Depend upon it, my dear Pliny, these Christians, though they never trouble

our courts, civil or criminal, are very dangerous people,

and either the Empire must put them down, or they will put the Empire

down."

"What,

then, would you have me do?" asked the Governor.

"Act

with energy; arrest these people; stamp the whole thing out."

"But

it is too horrible. It is—if you will allow me to say it—it is even absurd.

Here are thieves and cut-throats without number at large; profligates who spend

their whole lives in doing mischief, and villains of every kind. Yet a Governor

is to leave these hawks and kites to [71] themselves, and pounce

down upon a flock of innocent doves. Forgive me if I say, my dear Tacitus, that I never saw you so little like a

philosopher."

"There

are times," replied Tacitus, "when one has

to think, not about philosophy, but about policy. Look at the Emperor. You know

what manner of man he is. He is not a madman, like Nero; he is not a monster,

like Domitian, who was so fond of killing that he

could not spare even the flies. But Nero and Domitian

were not so stern with the Christians as he is. 'Obey

me,' he says, 'or suffer for it. If I let you choose

your own way, the Empire falls to pieces.' Yes, my dear Pliny, distasteful as

it must be to be a man of your sensibility, you must act."

"I

shall consult the Emperor," said the Governor, who felt himself hard

pressed by his friend's arguments.

"Certainly,"

said Tacitus; "it would be well to do so. I

understand that he wishes to be consulted about everything; though how he

contrives to get through his business is beyond my understanding. But meanwhile

act. You need not do any thing final, but Trajan, if

I know him, would be much displeased if he were to find that you had done

nothing."

"What

would you advise, then?"

[72]

"Send a guard of soldiers, and arrest the whole company at one of their

meetings. It would be easy to learn the place and the time. These societies have

always some one among them to betray their secrets; though, indeed, this can

hardly be a secret. You need not keep them all in custody. Probably many will

be slaves. I hear that the slaves everywhere are deeply infected with the

superstition. You can let them go, and make their masters answerable for them.

Nor should I take much heed of artisans and labourers; but you will keep any

person of consequence that there may be, and, above all, their priests, or

elders, or rulers, or whatever they call them."

The

Governor pressed a handbell that stood on the table

at his elbow, and bade the attendant who answered the summons send for the

centurion on duty.

In the

course of a few minutes this officer appeared.

"Fabius," said Pliny, "you have heard, I suppose,

of certain people that call themselves Christians?"

"Yes,

my lord," answered the centurion, "I have heard of them."

It

required all the composure—one might almost say the stolidity of look—that is

one of the results of a soldier's discipline, to enable [73] Fabius to reply without showing any change of countenance.

He had been for some months a "catechumen"—one, that is, who

was receiving instruction preparatory for baptism. He had been somewhat

inclined of late to draw back. The new faith attracted him as much as ever, but

there were difficulties which it put in his way. Could he hold it and be a

soldier? His teachers differed. The eldest minister, a man of liberal views,

thought that he could. Cornelius, the godly centurion, who was the first-fruits

of the Gentiles, had not been bidden to give up his profession. One of the younger men, whose temper was fiery, almost fanatical,

took the opposite view. The soldier was essentially a man of the world,

and the world was at enmity with the Church. Nor could Fabius

hide from himself the difficulties. Idolatry was everywhere. His arms, for

instance, bore the images of gods; to be present at sacrifice to gods was a

frequent duty; worst of all, he would himself be called upon to sacrifice by

burning incense before the image of the Emperor. All this had made

him hesitate.

|

|

"Do

you know their place of meeting?" asked the Governor.

Fabius assented.

"And the time?"

To

answer readily would have been to betray [74] too intimate a

knowledge of the Christians' proceedings.

"Doubtless,"

my lord," he said, despising himself at the same time for the

prevarication, "I can find it out."

"Then

take a guard on the first occasion that occurs, and arrest in the name of the

Emperor all that you may find assembled."

"It

shall be done, my lord," said Fabius, still

unmoved, and, after saluting, withdrew.

No one

would have recognized the centurion Fabius, with his

almost mechanical rigidity of movement, in the agitated man who, for the next

hour, paced up and down in his chamber. It is to be feared that he wished over

and over again that this disturbing influence had never come into his life.

Here was a conflict of duties such as he had never even dreamed of. Could he

let these men and women whom he knew, some of whom had been so kind to him, who

would have done all they could for him, run blindly into danger? And yet, would

it not be a breach of duty to warn them? The Governor trusted him; the charge

laid upon him was a secret. Could he, as a soldier, betray it? Again and again

he made up his mind, only to unmake it the next moment. At last the struggle

ended, as such struggles often do, in a compromise; and here circumstances [75]

helped him. The meeting would be the next day, he knew; and it was now

afternoon. There would not be time to warn all the members of the community,

even had he known—what he did not know—where they were to be found. But there

was one to whom word must be sent at any cost. This was Rhoda, the daughter of Bion. Fabius had been one of the

many who had been struck by the girl's singular beauty. Like his rivals, he had

seen that her heart had no room for any earthly love. Still, he cherished her

image as one might cherish the vision of an angel. To think of her in the rude

hands of soldiers, or dragged to the common prison, was simply intolerable.

That must be prevented, if it cost him his officer's rank, or even his honour.

No sooner

had he made up his mind to send the girl a warning message, than, as if by the

ordering of some higher Power, an opportunity presented itself to him. He

caught sight of one of Bion's slaves, who was driving

down the street an ass laden with farm produce. To accost the man as he passed

might have raised suspicion. A safer plan would be to waylay him as he

returned, which he would scarcely do before evening was drawing on. And this he

was able to carry out without, as he felt sure, being observed by any one. He

thrust into the hands of the old man—a [76] faithful creature, whom he knew to

be deeply attached to Bion and his family—a letter

thus inscribed:—

"Fabius the Centurion, to Rhoda, daughter of Bion.

"I

implore you that to-morrow you remain at home. This shall be well both for you

and for those whom you love. Farewell."

THE ARREST

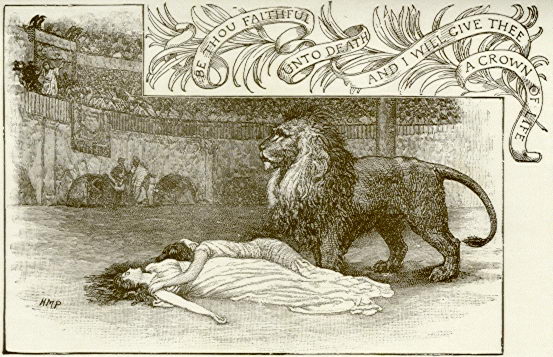

[77] THE centurion's message was

duly delivered to Rhoda, nor, thought it failed in its immediate object, was it

sent wholly in vain. The girl herself never for one moment entertained the

idea of profiting by the warning so as to secure her own safety. She would have

been even capable of suppressing it altogether, if she could have been quite as

sure of others as she was of herself. There was nothing that she felt to be

more desirable that the martyr's crown, and why should she hinder those who

were dear to her from attaining the same glory? But these high-wrought feelings

had not wholly banished common sense. She was perfectly well aware that such

aspirations were beyond the average capacity of her fellow-creatures. She

doubted whether her own sister was equal to them. She was quite sure that some

of her fellow-believers would fail under the fiery trial of martyrdom, and she

shrank from the peril of ex- [78] posing them to it. Nothing could be more

dreadful than that they should fall away and deny their Lord. It would be a

deadly sin in them, and, to say the least, a lifelong remorse to her, if she

should have led them into such temptation. Her mind was soon made up. Her first

step was to find her father, and give him the warning, only keeping back, as

she felt bound to do, the name of her informant. Bion,

whose practical good sense told him that dangers come quickly enough without

one's going to meet them, resolved to keep all his family at home. Under

ordinary circumstances, knowing the temper of his elder daughter, he would have

charged her on his obedience not to venture out. But Rhoda's action in freely

coming to him with the warning that she had received, put him off his guard. He

took it for granted that she would attend to it herself, and, not a little to

her relief, let her go without exacting any promise from her.

The next morning she started earlier than usual for the place of

meeting. Her hope was to see the Elders, communicate what she knew to them, and

leave the matter in their hands. They would know what was best for their

people. If they judged it better that the disciples should hide from the storm

rather than meet it, she would obey their decision, whatever might be her own

disappoint- [79] ment. If, as she hoped, their

counsel should be "to resist unto blood," then she would be there to

share the glorious peril.

One of

the little accidents, as we call them, that so often come in to hinder the

carrying out of great plans, hindered Rhoda from accomplishing her design. She

started at an earlier hour than usual, before there was even a glimmer of

twilight, and instead of being more careful than was her want in picking her

way along the rough lane that led from the farmhouse into the public road, was,

in her haste, more heedless. Before she had gone fifty yards from the house,

she stumbled on a stone, and for some moments felt as if she could not move

another step. Then her resolute spirit came to her help. "To think of the

martyr's crown, and then be daunted by a sprained ankle!" she said to

herself; and she struggled on. But all the courage in the world could not give

her back her usual speed of foot; so that the hour of meeting had already

passed while she was still some distance from the chapel. She was still

crawling along when another of the worshippers, a young slave who had been

detained at home by some work which he could not finish in time, overtook her.

She at once made up her mind that he must act as her messenger, and that the

message must be as brief and emphatic as possible.

[80] The

young man halted when he recognised her figure, saluted her, and asked whether

he could give her any help.

"Leave

me, Dromio", she answered, "leave me to

shift for myself; but run with all the speed you can tell the Elder Anicetus that there is danger."

Dromio waited for no second bidding. He started off at once

at the top of his speed, and as he was vigorous and fleet of foot, he reached

the place of assembly in a very few minutes.

The