|

The Crown of Pine by Alfred J. Church |

Table of Contents

The First of the Wheat Ships

In

the Jews' Quarter

Archias

of Corinth

A Bread Riot

A

Desparate Defence

Seneca

In the Circus, and Afterwards

The Proclamation

An Exiled Nation

The

Imperial Pass

The

Gallinarian Wood

Eastward Bound

Corinth

A Young Champion

Paul of Tarsus

A Secret

Jew and Greek

Cleonice

Plots

A Drug

An Antidote

Fresh Plots

Among the Hills

Before

the Archon

A Dilemma

Cleonice to the Rescue

The Release

Under

Cover of the Law

The Games

The Casket

Rewards and Punishments

Back to Rome

Front Matter

PREFACE

[7] I HAVE transferred to the Isthmian Games, of which we know

very little, some details of the proceedings at the great festival of

|

A. J.

C. |

IGTHAM,

August, 1905.

NOTE

The

story of Thekla has come down to us in a document entitled The Acts of Paul

and Thekla. As we have it now it is probably much changed from its original

form and contains many interpolations. It rests, however, there is very little

reason to doubt, on a basis of fact, and may be supposed to date from the

beginning of the second century, if not from an earlier time. It is not likely

that a later writer would have been acquainted with some curious details which

are to be found in the narrative. Queen Tryphæna was a real personage,

the widow of a certain King Polemo, and was related to Claudius through the

family of Marcus Antonius, the colleague and afterwards the rival of Augustus.

This marks the date of the scene in the amphitheatre as having happened in the

reign of Caligula or Claudius. No other

of the Emperors were related to her.

THE FIRST OF THE WHEAT SHIPS

[13] THE time is an hour or so after sunrise on the fifteenth

of May in the year 50 of our era; the place is one of the piers of the Emperor

Claudius's new harbour at

"Your

eyes are better than mine, Raphael," says the elder of the two to his

companion. "Can you make her out?"

"Scarcely

yet, father," replied the young man. He had scarcely spoken, however, when

the passing of a cloud let a brilliant ray of sunshine fall on the vessel's

bow. "There, there," cried Raphael ben Manasseh—this was the young

man's name—"I can distinguish The Twin Brothers."

"Accursed

idols!" growled Manasseh, spitting on the ground as he spoke.

Raphael

shrugged his shoulders, casting at the same time an apprehensive glance around

him.

[14]

"Don't you think, father," he said in a deprecatory voice, "that

it might make a little awkwardness, if any people happened to be near? And if

we charter these people's ships, might we not put up with their ways?"

"Well,

well, you youngsters are all for compromise and peace. I often wish that I was

well away from this land of abomination. Dear

"Business

very slack there, I take it," murmured Raphael. "I doubt whether one

could find a hundred shekels in the whole place? But see, sir," he went

on, "they are lowering a boat; a good thing too, or we might be loitering

here till

While

father and son are waiting, with what patience they can summon, the arrival of

the boat, we may explain the situation. The ship, which bears the name and sign

of The Twin Brothers, to become famous afterwards for carrying a very

distinguished passenger, (Footnote: "We departed in a ship

of Alexandria which had wintered in the island, whose sign was Castor and

Pollux," says the writer of the Acts, after describing St. Paul's stay in

the island of Melita (Malta). The Greek has Dioscuri, literally "Lads of

Zeus," The Twin Brothers, whose names in their Latinized form were Castor

and Pollux. It was a common sign of ships, which were supposed to be under the

special protection of the two demigods; so Horace, praying that the ship which

is carrying Virgil to Greece may have a prosperous voyage, says—"May those

twin stars, fair Helen's brothers, guide thy course, O ship, with ray

serene.") was the first of the great [15] fleet

of wheat ships which would be making the passage between

|

|

The boat

had now reached the pier. It carried two men in the stern. One of them who held

the rudder lines was the captain, who was also a part owner. He was a thick-set

man of middle age, a Corsican by birth, who might have sat for the portrait of

one of the brigands of his native island. Just then, however, he was on his

best behaviour. Manasseh was his very good friend and partner, who had lent him

the money at the quite moderate interest of ten percent to enable him to take

up a share in The Twin Brothers. He stood up in the stern [17] and

respectfully saluted the great man on the shore, a politeness which the Jew

returned with as much courtesy as he could bring himself to show to a heathen

dog. The other passenger, who was no less a person than the

supercargo, climbed up the steps of the pier. Manasseh and Raphael

greeted him warmly; he was, in fact, a near kinsman, a nephew of the elder and

cousin of the younger man. His name was Eleazar.

"Welcome,

nephew," said Manasseh. "You have had a good voyage,

that I can tell from your having come in such excellent time. And you

are well—to that your blooming looks bear witness. And you bring good

news?"

"That,

my dear uncle, depends upon how you take them," replied Eleazar,

"but—"

And he

looked round on the little crowd which had by this time gathered on the pier.

Then as now a very little incident sufficed to bring a crowd together at the

seaside. This particular occasion, too, as some of the bystanders were aware,

was one of special importance. The seafaring men had recognised The Twin

Brothers, and knew that she was the first comer of the wheat ships, and

they had also a shrewd idea that a meagre time might be at hand.

"You

are quite right, my dear Eleazar," said the old man, interpreting

correctly his nephew's [18] look; "this is too public a place for

discussing business. We can find a convenient room at the inn, if you know our

countryman Jonah's place by the

"Thanks,

uncle," said Eleazar, "I am too used to the sea to feel quite like

that; still, I do vastly enjoy my first bite and sup when I get on shore."

The

party soon reached the tavern, a building with a humble exterior, which, in

accordance with the universal Jewish custom, belied the comfort, not to say the

luxury, of the interior.

"What

do you say to a flask of

Raphael

made a wry face. "My dear father,

"Would

you drink these Gentile abominations?" growled the old man.

"Surely,

sir, there is nothing in the law that forbids it."

Manasseh

could hardly say that there was, and Raphael was served with his flask of

Falernian, his cousin admiring his courage, but caring little for the matter in

dispute.

"And

now to business," said Manasseh. "How about the

wheat, Eleazar?"

[19]

"A very short harvest, and poor in quality."

As he

spoke he drew out of his pocket a little sample bag such as dealers carry now,

and have doubtless carried from time immemorial, and poured out the contents

upon the table. Manasseh and Raphael carefully examined the grain. They were

not long in coming to a conclusion.

"As

poor a sample as I have ever seen," remarked the younger man.

"Well,"

said the father, "I can hardly go so far as that.

I can remember a long time, you see; but it is very poor. And this, you say, is

a fair sample."

"Yes,"

replied Eleazar, "quite a fair sample; some of the grain from

"And

the price?" asked the older man.

"Well,"

said the other, "the price is a very serious matter. It is pretty high

now; but no one can say what it will rise to. Let me tell you what I have done.

Early last month I bought a million medimni, to be delivered before the end of

May, at a hundred and twenty-five sesterces the medimnus. (Footnote: An Egyptian

medimnus equalled three bushels. These and other measures differed as much as

our own used to do. A hundred and twenty-five sesterces may be reckoned at £1.

This would be equivalent to about fifty-four shillings the quarter, nearly

double the price at which it is standing at the present moment in

Manasseh

and his son looked very grave. They had hoped for a rise and, as has been seen,

stood to win considerably by it; the supercargo's bargain meant a gain of at

least £250,000—but (Footnote: I use now, and shall use

hereafter, English equivalents for quantities and prices.) there might easily

be too much of a good thing. The State had a way of interfering when prices

rose above all bearing, and private interest went to

the walls. And nowhere was this more likely to happen than at

"You

have done quite right," said Manasseh after a pause; "and I should

not have complained if you had bought five times the quantity. But I must

confess that I don't like the prospect. The Treasury is in a very poor way.

This fine [21] new harbour has cost an enormous sum of money; so have the

drainage works and the aqueducts and the markets. And then for every pound

honestly spent another pound has been stolen. Those two scoundrels of freedmen,

Pallas and Narcissus, must have at least two million apiece. These are the

lions, and there are whole herds of jackals and wolves that are fed to the

full. Every farthing comes out of the Treasury. Now what I want to know is

this—how is the corn that is given away every week to be paid for? We are under

contract to supply a hundred thousand bushels every month. We have guarded

against a rise in price, but not against such a rise as this. The Treasury

won't—in fact, it can't—pay the price that we ought to

ask. I see trouble ahead."

It is

needless to repeat the subsequent conversation. The practical conclusion

arrived at was to buy up all the wheat that could be got, before the impending

scarcity became a matter of public knowledge. There would have to be large concessions

in the way of prices; but this would hurt them the less, the stronger they

could make their position or holding. It was arranged that Eleazar should enjoy

the hospitality of his uncle's house as long as he remained in

IN THE JEWS' QUARTER

[23] MANASSEH and Raphael had granaries, with an office and

a permanent staff, at

Eleazar

was bound for the other end of the Quarter, a region of shops and factories. He

had no difficulty in finding the place of which he was in search. It was a

factory where the hair of the goats that roamed over the hills of Rough Cilicia

(Footnote:

"Lucius

Cilnius Aquila of

"I

commend to you and to my sister, your most honoured

consort, the bearer of this epistle, Eleazar ben Nathaniel, an inhabitant of

this city, a young man zealous of all good things, and filled with a most

laudable desire to increase his knowledge of such matters as concern the

spiritual life. I am assured that he is altogether faithful and trustworthy.

Nevertheless there are certain things, which, especially in these days, it is

better not to write with paper and ink, but to communicate by word of mouth.

For this reason I leave the young man himself to set forth to you that which is

in his mind. Farewell."

As

[26]

"All my brother's friends are mine," he cried. "And when did you

see my dear brother last? Was he quite well?"

"Quite

well when I saw him, and that was just a fortnight

since. He gave me this the night before I sailed, and I landed this very

morning at

"You

bring good news," said

Eleazar

explained that he was his uncle's guest.

"Ah,"

said

"Yes,

with pleasure," replied Eleazar. "I excused myself from the meal at

my uncle's, because I did not know when I should be free."

"Come,

then," said

[27]

"A friend of our dear Lucius, my Priscilla," said

When the

lady rose from her place to greet him, Eleazar thought that he had never seen a

nobler looking woman. That she was not a countrywoman of his own he felt sure.

At least he had never seen a Hebrew lady with so commanding a figure, with such

a wealth of golden hair, and a complexion of such dazzling brightness. And,

indeed, Priscilla was no countrywoman of his. He was but seldom at

The

young Jew—I may say at once that he was

The one

characteristic Roman worship was that of the Deified Augustus, with whom were associated other princes of the Imperial house.

Pomponia had not broken with the ordinary observances of private and public

religion. At home she hung the usual garland on the family Lar, and saw that

the usual offerings of food were placed before the image; in public, she

attended such festivals as public opinion, now grown very lax in such matters,

made obligatory. But these [31] devotions were perfunctory; her real thoughts

in this province of her life were very different. What she heard from the Jew

gave to these thoughts a definite shape. Little, of course, was said at the

first interview.

It was a

momentous event, therefore, for themselves and for others when the two natives

of Cabira happened to meet in the streets at

At this

point Pomponia had a sudden impulse to intervene. Why should not her young

friend find one who would be at once husband, protector and teacher, in

ARCHIAS OF CORINTH

[40] THE conversation that followed the introduction was

profoundly interesting. Eleazar had much to say about his friends at Alexandria,

about the other Aquila with whom he had been for some years on terms of

intimacy, and many others, not a few of whom turned out, as so often happens,

to be mutual acquaintances. Much was said about an eminent native of the city

who had lately passed away, the great philosopher Philo.

When he

was compelled to depart, for the talk was prolonged far into the night, and he

was bound to present himself without more delay at his uncle's house,

[43]

"Don't go," said

"I

hope not, sir," replied the newcomer with a courteous inclination of his

head. "In fact, I may say that I expect that it will be speedily

settled."

The

stranger was a Greek who numbered between fifty and sixty years, evidently a

gentleman, and if one might judge from his face and general bearing, a man of

intelligence, refinement and culture. He was a native of Corinth, a member of

what was beyond question the most distinguished family in the city, that of

Archias, the founder of Syracuse. Archias was the name that he himself bore,

and he claimed to be twenty-second in direct descent from the first of the

race. This took back his pedigree over nearly eight hundred years; but the

family was really much older than this. His ancestor was the first of his race

in the sense that he brought into it the glory of having led with success the

most distinguished colony that ever went forth from

He now

began to explain the business which had brought him to

"I

have the honour," he said, "to be the chief magistrate, or archon,

as we are accustomed to call it, of the city of

"This

all seems reasonable enough," remarked

There is

no need to report the conversation any further. Archias produced his paper of

particulars, as also, by way of credentials, a letter of introduction from

Gallio. When the matter had been fully gone into, it was arranged that

A BREAD RIOT

[47] IT is not to be supposed that so important an event as a

rise in the price of wheat would long remain unknown in

"What

is the good of telling us that

This

oration was received with shouts of applause, and an imprudently candid

bystander who ventured to observe that a common calamity would have to be put

up with by all was hustled and kicked and generally given to understand that

his opinions were highly unpatriotic.

The

system in use for managing the distribution of bread without disturbance or

delay was that every tribe—the tribes numbered a few over thirty—resorted to a

depôt of its own. Each man or woman entitled to share in the public

bounty was provided with a ticket, and a tribe, [49] which in earlier times had

been an important political body, was now practically nothing more than a

corporation of such ticket-holders. These corporations again had an informal

arrangement of their own by which the distribution was made easier. As each must

have numbered several thousand persons, there might easily have been no little

discomfort and even danger in obtaining the allowance. To guard against this a

certain order was established. The older ticket-holders had precedence; and it

was a practice for one man to act for others. He would go attended by two or

three porters, and would so be able to carry away the allowances of a

considerable number of ticket-holders. On the whole the matter was managed in a

quiet and orderly manner; at the same time there were no small possibilities of

disturbance. In a time of excitement voluntary arrangements of this kind are

likely to become ineffective.

The time

of distribution was at hand. At a signal given by the sound of a bugle, the

doors of the depôt were thrown open, and the business began. It should be

explained that the doors were approached by a flight of broad steps, up which

each ticket-holder had to pass. As a matter of fact there were many buttery

hatches, at which a considerable number of ticket-holders [50] could be served

at once. Passages were made by which those who had received their allowance

could retire without interfering with fresh applicants. Not many minutes had

elapsed before the first corners had been served and had made their way back to

their fellows; a few minutes more and the whole multitude was in a state of

excitement, which became greater when one of the loaves distributed was raised

on the top of a long pole, and so made visible far and wide. No one who saw it

could doubt for a moment that the size had been materially reduced. This was

not all. It soon became generally known that the quality of the article had

been reduced as well as the quantity. The colour and smell of the bread showed

clearly enough that a good deal of grain other than wheat had been used in

making it. The worst fears of the crowd were realized. It was evident enough

that the authorities had the intention of putting off the pensioners of the

public bakeries with a smaller quantity than they had been accustomed to receive,

and that the diminished ration was also of a less palatable quality. A

Southerner, in whose diet bread is an even more important thing than it is to a

dweller in the north, is particularly sensitive as to its quality.

It was

not long before the excitement began [51] to vent itself in the usual acts of

violence. Of course the first thing was to make an attack on the bread

depôts. The authorities had foreseen the probability of such a result,

and had made preparations accordingly. Each depôt had its garrison of

soldiers. They had been kept out of sight as long as it was possible to

dispense with their services, but were now instructed to show themselves. The mob were for the most part unarmed, though

some of the most turbulent spirits had provided themselves with bludgeons and

even more formidable weapons, and at sight of the armed men it drew back. The

excitement had not yet become so intense as to make it

ready for so unequal a conflict. Then there was a diversion; for Narcissus, one

of the wealthy freedmen who shared the real though not the ostensible

management of public affairs, was seen to pass in his gorgeous chariot close to

the outskirts of the crowd. "See the scoundrel who battens on the hunger

of the people," was the cry raised by the multitude in a hundred different

ways, and an ugly rush was made in the direction of the equipage. But Narcissus

was perfectly well aware of his unpopularity, and had made special preparations

that day to protect himself against any manifestations

of hostility. A strong escort of Praetorian cavalry was in [52] attendance.

They were riding at a considerable distance behind the carriage, so that an

uninformed spectator might have supposed that their presence was accidental.

But the officer in command was clearly on the watch for what might happen, and

as soon as he saw the movement of the crowd he gave the order to his men to

close up. Instantly the troopers put their horses to the gallop, and before the

foremost rioters could come up, they had formed themselves in a close body on

each side of the equipage. The crowd, baulked of their vengeance, could do

nothing but give vent to a storm of shrill cries of rage and angry

exclamations. These were redoubled when Narcissus was seen to salute the crowd

with an ironical courtesy. Nothing more was possible; in a few minutes he was

safe within the strongly guarded walls of the

But the

crowd was not going to be so easily mocked and eluded. The rioters were not

rash enough to venture on a collision with the Praetorian cavalry, nor to break their heads against the stone walls of the

public bakeries. But there were other bakers who would furnish an easier prey.

Some of the creatures, thoughtless or malignant, who are always at hand to

suggest some kind of mischief to an excited crowd, raised a cry of "Down

with the bakers," and a rush was [53] made to the nearest establishments.

Some had been prudent enough to shut up their shops and remove all their wares;

others had sought and obtained the protection of the city-guards; but many were

quite unprepared for the outbreak. They were not in the least to blame, as far

as the ticket-holders were concerned. Possibly they had raised the price upon

their private customers before they had felt the pinch themselves, and while they

were still using the stock bought at the old prices—bakers and other tradesmen

were not above doing such things in ancient Rome, as they are not above doing

them in modern London. Possibly also they had charged these same customers with

an increase which more than made up for the market rise—this is probably a

practice as old as the baking business itself. But they were not in the least

responsible for the small loaves, largely made up with rye-flour, which had

been issued from the public depôts. Their innocence did not protect them.

The crowd had a bread grievance on their minds, and were not at all particular

on whom they vented it. Shop after shop was wrecked,

most of the spoil being as usual trampled under foot and generally wasted. The

plunderers were not hungry, but angry. Then it occurred to them that spoiling

bread shops and bakeries with a [54] blazing June sun overhead—it was almost

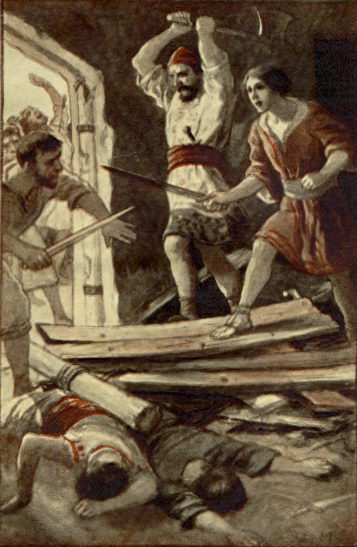

A DESPERATE DEFENCE

[56] MANASSEH, the dealer and speculator in wheat, had other

irons in the fire. He had a jeweller's shop on the Esquiline Hill, a quarter

which, since the building of Maecenas' great villa, had become fashionable; and

he united with the business of a jeweller two occupations which could be

conveniently carried on in the same premises, banking and money-lending. The

combination was, as may be supposed, productive of handsome profits, though not

without considerable risks. A fashionable lady would spend a couple of hours or

so in looking through Manasseh's stores, replenished almost day by day by

consignments from compatriots settled in all the great markets of the East and

the West. Not long after would come a visit from her husband, who would find

himself at a loss how to settle the account. Manasseh was as ready to lend the

money as he was to supply the jewels for which the money was to be paid. His

prices [57] were high, as they had a right to be where everything sold was of

the very best quality and indisputably genuine, and he charged about fifteen

per cent on his loans; so he made handsome profits in both ways. Sometimes, of

course, things did not turn out well. There were "sharks swimming

about" in the Roman streets as there are in the

It was

now, however, to undergo one of the shocks which defy the acutest speculation,

and against which no precautions can guard, an outbreak of popular violence.

The rioters were pausing to take breath after sacking some half-dozen wine shops

when some one cried, "How about the Jews?" The name was like a spark

of fire dropped upon a heap of brushwood. It kindled an instantaneous fire. The

Jews have never been liked by the people among whom they have settled. Their

virtues and their vices have combined to make them unpopular. They are frugal,

industrious and sober. It is only right that these qualities should have their

reward; [58] that men who possess them should get better places, earn better

wages, save more money, provide themselves with more comfortable homes than

their neighbours who spend up to the last farthing of their earnings, and lose

at least a tenth part of their working time in riotous excesses. But those who

fall behind in the race of life do not feel amiably towards those who pass

them, nor is their animosity lessened by the consciousness that their defeat is

the result of their own folly. A more reasonable cause of the popular dislike

of the Jew was to be found in the hardness and sharp dealing of which some of

the race were actually guilty and of which all were accused. However it came

about, and whether it was deserved or undeserved, the unpopularity of the Jews

was an unquestionable fact. The suggestion of the name had accordingly an

immediate effect. In a few minutes there was a general cry of "Down with

the Jews." It is probable that very few in the crowd had suffered anything

at their hands, and that of these few scarcely one had got anything more than

he amply deserved. But such cries may be uttered without any reason. The mass

of the rioters had a vague feeling that things were in a bad way, and that they

might improve if something were done. The leaders of the crowd had much [59]

clearer ideas of what they wanted and of how it might be got. The Jews were

excellent people to plunder. The booty would be great, the resistance probably

weak, and the chances of impunity considerable. Jewish plaintiffs were not

popular in the courts, and magistrates had been known to dismiss their

complaints even when they were supported by unimpeachable testimony.

The

crowd was prepared to act, but it still wanted a leader. "Down with the

Jews" was quite to its mind, but where was the work to begin? The crowd

was not long left in doubt. A stout rioter, who had been very busy in

plundering the wine shops, and showed sufficient proof of his zeal, was ready

with a suggestion. The fellow had been a porter, and had been employed by

Manasseh, who was unreasonable enough to expect an equivalent in work for what

he paid in wages.

Gutta—this

was the man's name—would never have done a stroke of work if he could have

relied on the State for wine as well as bread. He thought this below the

dignity of a free-born Roman, and resented the interference. He resigned his

situation with all the dignity of one of the masters of the world, and waited

an opportunity of making himself even with his tyrannical [60] employer. And

now, he thought, the opportunity had come.

"There

is that Jew dog, Manasseh. It is he and his gang that have put up the price of wheat.

The furies seize him and his small loaves and his rye bread!"

"Where

shall we find the fellow?" cried a voice from among the crowd.

"In

the Jews' quarter, of course," said another. "I know the place, a big

house close to the river."

There

was a movement in that direction. But the porter shouted, "No! no! there is a better way than

that. The villain has got a shop in the

A

wrangle followed. One party was for the house. The Jew was sure to keep his

best things at home. The other preferred the shop. Everything there, they

argued, will be ready to our hands, while we may spend hours searching the

other place. In this discussion not a little valuable time was lost, perhaps one

should say gained, if we take the point of view of law and order. These were

now to receive the help of an unexpected ally.

The

Corsican captain of The Twin Brothers, who had found the time hang

rather heavy on his hands, had happened to witness the scene at [61] the

bakery, and had followed the mob, with no sort of idea of sharing their

plunder—he was far too respectable for that—but in the hope of finding

amusement and possibly adventure. He was sitting in the wine shop of a

compatriot, whose property he had helped to preserve, when his ears caught the

name of Manasseh. He had the ready intelligence that marks the successful man

of action, and he at once comprehended the situation. He had a shrewd suspicion

that the porter would have his way, and that the Esquiline shop would be the

first object of attack. If he was wrong, and the house by the river was

attacked, the mistake would not matter much. There was less property there that

could be easily plundered, and there would be men to guard it. The shop, on the

other hand, was full of valuables. He arrived at this conclusion after a few

moments' thought, and when he had arrived he acted immediately. He enlisted on

his side two stout lads, sons of the Corsican innkeeper, and hurried with them

to the shop. Manasseh and Raphael were both there. The Jews, as usual, were

admirably served in the way of intelligence. They had suspected for some days

that trouble was brewing; they had had early information of the outbreak;

experience had taught them what direction it would certainly [62] take, and

they knew as well as the porter, and probably better, that the shop in the

|

|

In the rear

the defence was not so successful. The door and the window were, as has been

said, well protected, but there was a side yard, approached by a narrow

passage, which opened out onto the street some distance lower down. The

captain, to whom the locality was quite [65] strange, knew nothing about it;

Manasseh and Raphael had forgotten its existence in the hurry of the moment.

But the porter knew it well, and when the front attack had been so disastrously

repulsed, had bethought himself of making it useful. The movement was for a

time successful. The passage was unguarded, and the assailants, nearly a score

in number, found themselves in the yard without loss. Here, indeed, there was a

brief check. The only communication between the yard and the house was an

opening not unlike a buttery hatch. This was, of course, too small for a man to

pass through, but as the wall round was of timber only, it admitted of being

easily enlarged. Two or three of the assailants set about doing this. While

they were thus engaged, Manasseh struck at one of them with a spear from the

inside, and wounded him severely. In so doing, however, he exposed himself to a

similar thrust from outside, and the opportunity was not lost. He received a

wound in his side, and Raphael himself was touched, though but slightly, as he

dragged the old man away from the opening. Meanwhile the timber, though

sufficiently stout, was giving away under the repeated blows that were dealt on

it. Raphael, though loath to call his stout ally, the Corsican, from a post

where his prowess was, [66] he well knew, sorely needed, felt that he had no

alternative. His father was absolutely helpless, and he was himself, if not

disabled, somewhat crippled. His halloo was immediately answered by the captain

in person. The man, who had the eye of a general, took in the situation at a

glance. He saw that nothing was left but to gain time. It was useless, he felt,

to propose a parley. The rioters knew as well as he did that the guardians of

the peace must come before long, and that when they

came the game was up. No, there was nothing for it but to fight to the last;

but how? and where? Then the thought flashed upon

him—why not the upper room in the front part of the house? This was approached

by a somewhat steep staircase, and a staircase was exactly the place for a

defence when the odds were desperately large. He caught the wounded Jew up in

his arms, and bidding the younger man follow, ran with him at a speed which

would have been deemed impossible in a man so burdened, and got him safely to

his destination. There was a reprieve, but it seemed likely to be but for a

very few minutes. Happily, however, the defensive capabilities of the new

position were not to be tested.

SENECA

[67] AT last, when it was almost too late, the guardians of

order appeared upon the scene. The watch, or, as we should say, the police,

which had the business of keeping the peace in

"Let

them settle their own quarrel," the officer on duty had said with a shrug

of the shoulders; "it is six of one and half a dozen of the other. The Jew

has been trying to cheat the Roman in one way, and the Roman to cheat the Jew

in another; one asks double the right price for the goods, and the other wants

to get them for nothing at all."

A more

urgent message, however, made it evident that something had to be done. A

company therefore was equipped, as speedily as military formalities permitted.

It had just started when a third and still more alarming summons had arrived.

The men were then ordered to go at the double, and, as has been said, arrived

just in time to prevent disaster.

The

centurion in command found himself more interested in the affair than he had

expected to be. In the first place the casualties had been numerous. Five of

the assailants had been killed, and two more so severely wounded that their

recovery was doubtful. The corpses had to be removed and the wounded carried to

their homes, such as they were; the hospital to which they [69] would nowadays

be taken did not then exist. Then there was the fact that the owner of the

place which had been attacked was a person of importance. Almost every one in

The next

thing was to obtain a trustworthy narrative of what had happened, on which to

base the report which the centurion would have to make to his superior officer.

Obviously the Corsican was the right person to tell the story. The centurion

listened to it with unflagging interest, and was not a little pleased to find

that the man was a compatriot and even a remote connexion.

"I

am heartily glad to make your acquaintance," he said; "you ought to

have been a soldier. Not one man in a thousand would have made such a defence;

and your last move was a masterpiece."

"You

are very good," answered the captain, [70] "but I am well content

with my own profession of the sea. I can't help feeling that you soldiers are

too much under command. Now when I am aboard my ship and out of sight of land,

I am as much my own master as any man in the world. Not Caesar himself can

meddle with me there. He has got his ministers and his wife and I know not who

else to reckon with. No, no! I wouldn't change places, no, not with Caesar

himself."

"Well,

well," returned the centurion, "we will talk about this afterwards.

Come back with me to barracks after I have settled this business."

It was

arranged for the present that the shop should be put in charge of an optio,

or deputy centurion, with a guard of five men. Raphael was to put his seal on such

safes and lockers as had especially valuable contents. Future arrangements were

left for further consideration. This done, the party bent their steps in the

direction of the barracks.

But the

surprises of the day were not yet over. As they were passing by the

booksellers' stalls in the Forum—traders were accustomed to congregate in Rome,

as they still do to a certain extent in modern cities—they were attracted by

the appearance of a particularly sumptuous litter that was in waiting in front

of one of the stalls. The litter [71] itself was richly upholstered in gold and

silk; the bearers, eight in number, were stout Bithynians, a race which it had

been the Roman fashion to employ for this purpose for more than a century. The

owner, a man between fifty and sixty years, was examining the contents of the

bookstall, and talking to the shopkeeper, who stood by in an attitude of

profound respect.

"That,"

said the centurion, in a whisper to his companion, "is one of our richest

men—Seneca."

"What!"

replied the captain, "is he back in

"Yes,

since last year," said the centurion; "but let us move out of

earshot." When they were at a safe distance, he went on: "He is in

high favour now: Caesar's wife cannot make too much of him. He teaches her son,

is a sort of tutor to him, you know; works with Burrhus, who is my chief, as I

daresay you know. But do you know him?"

"Know

him?" replied the captain; "I should think so. I had the taking of

him to

The two

crossed the street again and waited outside the shop. Seneca by this time had

finished his inspection of the book and was negotiating for its purchase with

the shopkeeper. The business was quickly arranged, for he was an excellent

customer, and his ways were well known. To offer a good price and to stick to

it was his plan, and the booksellers had the good sense to fall in with it. He

was about to step into the litter, purchase in hand, when he caught sight of

the captain. He recognised him immediately.

"Well

met, my friend," he cried; "and what brings you to

|

Refits his shattered bark, and braves Once more the vext Icarian waves, |

as Horace has it."

"Yes,

sir," replied the captain, "we are like the politician who is always,

I am told, forswearing public affairs, and always meddling with them again. And

after all we must do something to live. It isn't every one that has all that he

wants without earning it."

"Ah,

you have me there," returned the great man with a smile. "But where

are you now? [74] When I made my journey back from the place you know of, I

asked the captain about you, but he could tell me nothing."

"I

am captain and part owner of a wheat ship, one of the Alexandrian fleet."

"And

it is just what you like, I hope?"

"Well,

it might be better and it might be worse. But I don't complain. You see, I am

not a philosopher."

Seneca

laughed. "My dear friend," he said, "you are a little hard on

me. But you know the wise man is always himself except

when he has a bad cold, and, I think one might add, except when he is seasick.

But I can't wait; I am due at my pupil's in a very short time. But come and

dine with me to-morrow, and bring with you your friend, if he can put up with a

philosopher's fare. Will you do me the honour of introducing him?"

"Caius

Vestinius, a centurion in the watch," said the captain.

"You

will be welcome, sir," said Seneca. "I am delighted to make your acquaintance.

We are not half grateful enough to you gentlemen, whose courage and diligence

enable us to sleep sound in our beds. On the third day, then, at

[75]

With a courteous gesture of farewell he stepped into his litter and was carried

off.

"That

is a very polite person," said Vestinius, as the two resumed their

journey. "But I am scarcely disposed to go. I shall be out of my element

in such grand company."

"Nonsense!"

said the captain. "There is nothing particularly grand about him as far as

I can see. And besides, you must bear me company. It is not for a brave soldier

to desert his friend."

The rest

of the day was spent in jovial fashion, and it was only when Vestinius was

ordered out again on duty that the two friends parted.

IN THE CIRCUS, AND AFTERWARDS

[76] ON the day that followed the events described in the

last chapter, the popular discontent was displayed at the games in the Circus.

Some pains had been taken to make them more imposing and attractive than usual.

The wild beasts exhibited were the finest and rarest varieties; some performing

elephants were to exhibit their choicest feats, carrying a sick comrade, for

instance, in a litter on a tight rope stretched across the arena; some

favourite gladiators were advertised as about to contend. But all these

attractions failed to conciliate the multitude. The Emperor headed the

procession in order to give further éclat

to the show. He was received, however, with sounds suspiciously like a

hiss, and when his ministers passed, a deafening shout of "Bread! bread! Give us our bread!" arose on every side. The

Emperor, who knew, and, indeed, [77] was allowed to know, very little of what

was going on in Rome, was not a little frightened at the demonstration, and for

that reason all the more angry. When he was brought to take an interest in

anything outside his dining-hall and his library—he was as great a glutton of

books as of dainties—he could show himself both capable and energetic. His

ministers were not unprepared for the rare occasions on which their master

asserted himself. They bent before the storm, which would soon, they knew, blow

over, and leave them to follow their usual intrigues in peace.

"What

is this about bread?" cried Claudius.

Narcissus

explained that wheat had risen greatly in price, and that it had been necessary

to diminish the allowance made to the ticket-holders. The explanation did not

explain anything to the imperial mind. If Claudius had ever felt the want of

money, and it is quite possible that he had in the days before he came to the

throne, he had forgotten all about it. His ministers carefully kept all matters

of finance from his knowledge, and he had simply no idea of there being any

limit to what the treasury could or could not do.

"I

don't understand what you mean," he cried. "My Romans must have as

much bread as they want. It is not for the Augustus to [78] chaffer about how

many denarii are to be paid for this wheat that is wanted. I suppose that I

have money enough."

"Certainly,

sire," answered Narcissus, with a low bow. "Everything shall be

arranged according to your Highness' pleasure. But meanwhile will you please to

proceed to your place and give the signal for the Games to commence. Afterwards,

if you will condescend to listen, I will set the whole case before you, and we

shall then have the advantage of your counsel."

The

Games, which it is not necessary to describe, passed over without any untoward

incident, though the populace was obviously in a very bad humour. One or two

unsuccessful and unlucky gladiators received a death sentence which they would

probably have escaped had the masters of their fate been better content with

themselves and the world. The comic business of the spectacles moved very

little laughter, and their splendours very little admiration. But the whole

passed over without any positive outburst, and the authorities felt that they

had at least obtained a reprieve.

It was clear,

however, that no time was to be lost, and a council in

which the situation was to be discussed, and if possible dealt with, was to be

held that very day. The Roman hours for busi- [79] ness were very early, and it

was only a very great emergency that could be held to justify so late an hour

for meeting as the time fixed,

He was a

true father of his country, who was willing to give up anything rather than

that his people should suffer. They were equally complimentary when he

suggested that he should give a public recitation, tickets for which should be

sold at five gold pieces each. This idea was put off, for some sufficiently

plausible reason. Then [80] Narcissus gave his advice, introducing it with the

usual assurance of submission to the superior wisdom of the Emperor. The

substance of what he said was, that in his judgment the difficulty was

temporary, sufficiently serious indeed to demand prompt remedy—he was too

sagacious to minimize a matter about which Claudius, he saw, was very

anxious—but not beyond treatment by temporary measures. There was scarcity, but

it would pass away. Meanwhile those who had wealth ought to put a sufficient

portion of it at the service of the State for immediate uses. "I will

give," he went on, "two million sesterces." (Footnote: About £160,000.)

The sum sounded imposing, but to any one who knew the circumstances of the

case, it was but a small fraction of the wealth which, by means more or less nefarious,

the donor had stolen out of the public revenue. Still it had a magnificent

sound. Pallas, who was supposed to be his equal, if not his superior, in

wealth, followed with the offer of a similar sum. Two other officials

who had had fewer opportunities, though equal desire, for plunder, named

smaller amounts. At this point the Prefect of the Praetorians broke in with a

suggestion of a more radical policy. He praised the munificence of the

freedmen, though he contrived in doing it to convey the idea which we [81] know

to have been perfectly in accord with the truth, that they were but giving back

a part of what they had received or taken. "But," he went on,

"their gifts will only help us for a time; we must remove, if we can, the

cause of the evil. And what is the cause? I say that it is the avarice and

rapacity of the Jews.

One of

the freedmen ventured to say that so far as he had an opportunity of observing

them they seemed sober and industrious.

"Sobriety

and industry," replied the soldier, "are admirable virtues if the man

who possesses them is a patriot. If he is not, they do but make him more

dangerous. These Jews are a turbulent, discontented and disloyal lot. I saw

something of them when I was in command of one of the legions in the time of

Caius Caesar. (Footnote: Commonly known by the name of Caligula.) They

got into a state of furious excitement for some trifle or other, and there was

very nearly a rebellion."

"My

nephew," said the Emperor, "was, I think, a

little unreasonable. He wanted to set up a statue of himself in their chief

temple, and they objected to it. I cannot but think that they were in the

right."

[82]

"You are very kind, Sire, to say so, but for my part I hold that the dogs

should have felt honoured by the proposal. Who are they to flout at Caesar's

statue?"

"My

friend," said the Emperor, with a dignity which he sometimes knew how to

assume, "you are scarcely an authority on such matters. But what think

you," he went on, turning to Narcissus, "of these Jews?"

"Sire,"

said the freedman, "I do not deny that they are temperate and

hard-working; but this does not necessarily make them good citizens or good

neighbours. The fact is that they push our people out of the best places, and

they make themselves masters. They have always got money at command, and they

lend it. I know something about money lending; I was once in the business

myself, and I still have agents who employ part of my capital in that way. They

tell me that in nine cases out of ten when they have an application for a loan,

they find that a Jew has got a first mortgage on the house, or the

stock-in-trade, or the tools, or whatever it is that the man wants to borrow

on. They always take care to have the best in any matter they meddle

with."

"But

are they extortionate?" asked the Emperor.

"I

can't say that they are, and yet they are [83] unpopular; of that I am quite

certain, though it is difficult to say why. It would certainly please the

people generally if they were banished from

"Banished

from

"I

am sure, Sire," said Narcissus, "there are precedents, but your

Highness is better acquainted with these things than any of us. Was there not

something of the kind done with the Greek professors some two hundred years

ago?"

This

artful appeal to the Emperor's erudition had the effect which it was intended

to have. Claudius mounted his hobby and was fairly carried away.

"Yes,"

said he, "you are right. One hundred and ninety-nine years ago, to be

exact, the Greek philosophers and teachers of rhetoric were banished by the

censors of

By this time the Emperor had talked himself into a complete

forgetfulness of the events of the case, and showed no hesitation in signing

the [84] decree, artfully made ready for the opportunity.

As the

council broke up, Narcissus whispered to Pallas—

"After

all, our millions may not be so badly laid out; there

will be some shipwrecks, I take it, pretty soon; and it will be strange if

there are not some valuables to be picked up on the shore."

THE PROCLAMATION

[85] THE Imperial Chancery was busily employed for many hours

of the night that followed the council described in the preceding chapter, in

multiplying copies of the proclamation by which the decree of banishment was to

be made known throughout the length and breadth of

"IN THE TENTH YEAR OF CLAUDIUS DRUSUS NERO GERMANICUS, AUGUSTUS,

CONSUL FOR THE TENTH TIME.

"THE

EMPEROR BY THE ADVICE OF HIS TRUSTY COUNSELLORS HEREBY DECREES THE BANISHMENT

OF THE PEOPLE KNOWN BY THE NAME OF JEWS. ALL PERSONS BELONGING TO THIS NATION

MUST QUIT THE CITY OF

This was

posted up in all the quarters of the city. It so happened that our two friends

saw it for the first time as they were on the way together to Seneca's house.

Vestinius had been busily employed all the night in command of a detachment

told off to cope with a great fire, and had been asleep all day; the Corsican

had spent the morning at Ostia looking after some necessary repairs to his

ship. This had kept him so busily employed that he had barely time to keep his

appointment in

They had

not walked many yards, however, from the barracks when one of the posters attracted

them.

"By

the Twin Brothers," cried the Corsican, when he had read it, "this is a disaster! It means nothing less than ruin. What

will my employer do? Fourteen days to collect his property and to put it into

shape for carrying away. Why, he could hardly do it in fourteen years. You must

excuse me; I must go and see him at once. And it makes it all the worse that

[87] he is laid up. They told me at his house this morning that he was a little

better, but he certainly cannot be moved for weeks, and who is to manage for

him? It would be a great trouble at any time, his being laid aside, for he is

the only man who knows about his business from end to end; but now, I cannot

conceive what we shall do."

"I

can understand what you mean. But I don't think that it will be of any use for

you to go to him now. On the contrary you cannot do better, in my judgment,

than keep this appointment. Seneca is a great man; he is a power at court; if

there is anything to be done by private influence, he is the man to help you.

You cannot do better, I take it, than to ask his

counsel."

The

Corsican acknowledged the justice of the remark, and made no further difficulty

about fulfilling his engagement with Seneca. It is not necessary to describe

the dinner. If it was not sumptuous for a millionaire it was certainly

elaborate for a philosopher, and the guests, if they desired to share an

entertainment which they might look back to and talk about in years to come,

had no reason to be disappointed. Seneca suited his conversation to his

company, and seemed to have no difficulty in doing so. The [88] sailor found

that he knew all about ships; the centurion discovered that he was practically

at home in all the details of local administration. After dinner, when the

slaves had finished their service and retired, the Corsican put before his host

the case of Manasseh.

"I

don't particularly like this people," he said, "but the old man has

been my very good friend, and I should be sorry to see him wronged. His case is

very hard. It is bad enough at any time to be driven from his home, and now,

when it may cost him his life to be moved, it is downright cruelty."

Seneca,

though he was too familiar with the ways of courts, and had had too plain a lesson

of the need of caution, to be outspoken, was very sympathetic. In the ordinary

course of things he would have been invited to attend the council, and it was a

distinct affront that he had been left out. Whether he would have been able to

resist with success the policy of the freedmen was more than doubtful, and this

in a way reconciled him to the neglect. To the policy itself he was wholly

adverse. He saw clearly enough that the qualities that made the Jews unpopular

went at the same time to make them useful citizens. If they were frugal and

industrious, and keen traders and apt to make a profit out of any business in

[89] which they might engage, so much the better, not for themselves only, but

also for the State. The Commonwealth, he was sure, could not afford to lose men

of energy and resource and keep the indolent and shiftless. What if they did

enrich themselves? they were benefiting the country at

the same time, and this was exactly what the unhelpful and improvident

creatures who resented their superiority were sure never to do. The question of

the moment, however, was what was to be done in this particular case. After

turning the subject over in his mind for a few minutes, he gave the result of

his reflections.

"It

is a very hard case, as you say, this of your friend the Jew, but I think that

I can see my way to helping him. But first tell me,

have you any plan of your own?"

"Well,"

replied the captain, "I thought of suggesting that he should go with me on

my return voyage to

"Yes,"

said Seneca, "he would be that, but

"It

is very unlikely; in fact, the physicians declare that it is impossible."

"Well,

then, we must manage to get leave for him to stay awhile till he can travel

safely. I daresay that I shall be able to interest my pupil in him. He is a

generous lad, though the gods only know what he will become amongst such

surroundings. Put another Cheiron to bring up another Achilles in these days

and in

"Yes,

very rich, though I don't know enough about his affairs to fix any figures. But

I should certainly say that he is rich—yes, very rich."

"Well,

it is not a case of money; you would affront her by offering money. But she is

a [91] woman, and she can never have jewels enough. Could your Manasseh, think

you, gratify her in this respect?"

"Certainly,"

replied the Corsican. "I have a standing commission from him to buy what I

think fit in this way, and I have had some fine things come my way in

"Yes,"

broke in the centurion, "and it is my friend the captain's doing that he

has them now." And he went on to give a brief account of the narrow escape

that the Esquiline shop had had of being plundered of all its treasures.

"Has

he a son?" asked Seneca.

"Yes,"

replied the Corsican, "and a very shrewd young man too, though not to be

compared, in my mind, with his father. His name is Raphael."

"Well,"

said Seneca, "send this Raphael to me. We shall be able, I daresay, to

manage something between us. And when the father is recovered enough, he had

better go to

Shortly

after this the Corsican took his leave, in much better spirits about his patron

than he had had when he came.

AN EXILED NATION

[93] NARCISSUS had prophesied only too truly when he had said

that there would be shipwrecks in

The loss

as usual fell more heavily on the poor than on the rich. Great firms such as

that over which Manasseh presided had taken precautions against such

emergencies. They made a point of having a Gentile partner, who, being exempt

from the action of the decree, took up the character of sole owner. Of course

there was considerable risk of loss. The Gentile partner was not always an

honest man. And there remained the great personal inconvenience, though always

mitigated, as every trouble on earth is mitigated, by the possession of money.

The poorer Jews had no such alleviation of their lot; the small tradesman lost

his capital, the artisan lost his [95] employment. The Jewish race is patient

and tenacious of life beyond all others, with a quite unparalleled power of

recovery; all the same it suffered a great blow, and the misery endured by

individual members of it was past all reckoning. And there were not a few cases

in which others who could have had no share in the

supposed misdeeds of the people suffered along with it.

One

great calamity, however, they could do little or nothing to mitigate, and that

was the calamity which their departure brought on their [96] neighbours. A

Roman poet, who was certainly not harder of heart then the average of his

fellow citizens, counted it among the blessings of a countryman's life that he

had not to feel the pang of pity for the poor. This was a blessing which

That

they could do this was a great consolation to the two. They felt keenly the

breaking up of their life in

THE IMPERIAL PASS

[101] THE bulk of the exiles naturally chose the Ostian route.

Then, as now, it was much cheaper to travel by sea than by land. The wheat

ships, too, offered passages eastward at very cheap rates. They were the most

commodious ships afloat, and they made the return voyage mostly in ballast, for

the exports from

Raphael

had called on Seneca and had made a [102] very favourable impression on the

philosopher. The young Jew was a well educated man, and took a wide outlook on

life; while, at the same time, the peculiarities of his birth and upbringing

had left something highly distinctive on his character and bearing. It was the

first time that Seneca had come in contact with a Jew of the better type, and the

meeting interested him intensely as a student of human nature. Then, again, he

was attracted in his character of a philosopher. Seneca was a Stoic in his

belief, and a Stoic had more things in common with the Jew, as regarded God and

the ordering of the world, than any other kind of thinker. Lastly Seneca was a

great capitalist who had his investments all over the civilized world, and

unless he has been very much belied, was somewhat fond of money, impoverishing

the provinces, it was confidently asserted, by his usury. Anyhow he was greatly

taken by the shrewdness and wide knowledge of the young Jew, in whom he

recognized the acuteness and readiness of an expert in finance.

The

conversation of course speedily turned to the subject which was the cause of Raphael's

visit.

"I

was much concerned," said Seneca, "to hear of your father's

condition. How is he going on?"

[103]

"Wonderfully well, for an old man," replied Raphael, "but the

time is very short, and we are exceedingly anxious."

"I

can receive him here, where he would have every comfort of nursing and

attendance. Any one whom he might desire to bring with him would be welcome.

The authorities would make no objection. In fact the decree of banishment would

be suspended as far as he and his party are concerned. So much I can promise; I

have an assurance from the Empress that it shall be so. I understand, of

course, that he must be waited upon by his own people. His attendants,

therefore, would include any physician that may be in charge of him."

"You

are kindness itself, sir, but unfortunately the difficulty is not removed, and

I am afraid is not removable. You see—well, my father—is

well, shall I say old-fashioned? He keeps rigidly to the Law, and the Law as it

has been expounded and fortified by the ingenuity of generations of

professional interpreters. As for myself I can't hold with these ways. As long

as we were in a country of our own they were all well, we could live as we

pleased, and fix the conditions of life for ourselves. If a stranger did not choose

to conform to them he could keep away. But that is changed. We are scattered

all over the world, [104] and I venture to think it absurd that we should try

to carry all these safeguards and prohibitions with us wherever we may go. The

curious thing—I know, sir, that you are interested in these matters—is that it

is since this dispersion that these rules have been made so detailed and, if I

may say it, impracticable. All this, however, is beside the mark just now. The

fact is that my father would object as strongly to coming under the roof of a

Gentile host, as he would to being attended by a Gentile nurse. And if he were

to consent, which I may frankly say is impossible, then

his attendants would object. No, I am at my wits' end. He must travel, whatever

his condition, for there is simply no place where he can stay. His own house,

or indeed any Jewish house, is impossible, is it not, sir?"

"Yes,"

said Seneca, after a moment's thought, "I don't think that any Jewish house

could be exempted from the operation of the edict."

"And

it must be in a Jewish house that he stays, if he is to stay anywhere. That is

my dilemma, and I don't see any escape from it. He must go, and if he goes, I

very much doubt whether he will live to see Brundisium."

Seneca

reflected. After a pause he said, "Well, as he must go, there is nothing

to be done but to ease his going. Of course there will be a [105] considerable

crush on the Brundisium road during the next ten days. Well, I will get a pass

(Footnote: This pass, or diploma (a Latin or rather a Greek word, meaning a paper,

or parchment, or tablet, folded in two), was a document issued by authority

which entitled the bearer to be assisted on his journey in any way that he

might require, with fresh horses, for instance, or convenient carriages. It

bore the Emperor's seal and was in theory issued by him, but certain great

officials, among them the commander of the Praetorians, had the power of

granting them.) for your father and you and such attendants

as he will absolutely want. I should recommend you to send the others by the

"We

are greatly obliged to you, sir," said Raphael. "This makes our way

as plain as it can be made."

"One

thing more," Seneca went on, as his visitor rose to make his farewells.

"You remember the line—one of the wise utterances of the Pythian

priestess, if I remember right—'Fight thou with silver spears, and rule the

world,' but I dare say that your own wise men have said something of the same

kind."

[106]

"Yes, indeed," replied Raphael with a smile; "as the wise King

has it, 'A man's gift maketh room for him;' and room, I take it, is exactly

what will be pretty scarce on the eastward road."

THE GALLINARIAN WOOD

[107] AMONG the families which were relieved by the kindly

minstrations of

|

|

Marulla

was one of the humble friends to whom Priscilla paid a farewell visit. The

woman's demeanour was certainly embarrassed. She [109] seemed to be always on

the verge of saying something which yet she could not bring herself to utter.

Yet she was even more than usually affectionate. Her habit was to be reserved.

Priscilla knew her to be profoundly grateful for kindnesses received, but the

gratitude was not demonstrative. On this occasion, however, the reserve was

broken down. When Priscilla was about to leave the house, Marulla threw herself

upon the ground, clasped her round the ankles, and passionately kissed her

feet, shaken all the time with dry convulsive sobs. Priscilla left her with an

uneasy sense of unexplained mystery added to the grief which she felt at the

breaking up of a life in which she had felt all the pure pleasure which waits

upon disinterested kindness.

It was

now the eleventh of the fourteen days of grace allowed by the edict of

banishment, and

"Ah!"

said

Happily

the workmen in the tent factory had not been sent off. They had been kept back,

contrary to

"Rufus,"

he said, "is nothing more or less than a scoundrel. He has the reputation

of being in league with the banditti—we have, as I dare say you know, a great

many more of these fellows in these parts than we like. They don't harm us, it

is true, but they destroy the reputation of the road. It is certainly a fact

that several parties that have made the journey under the care of Rufus have

got into trouble. This may have been an accident. If so, Rufus has been very

unlucky, and it is as bad to be unlucky as it is to be wicked. But what is most

suspicious in the present affair is that Rufus has persuaded the party to go

round by way of Liternum. It was an easier road, he said, and with their

invalid to think of, they would not really be losing any time by taking it.

Well, I have lived in this country, man and boy, for sixty years, and I never

heard of the road by Liternum being better than any other. But I have heard of

its being a great place for banditti. The forest runs right up to the town, and

the road goes through it for a couple of miles or so. What with the forest and

its thickets and the marshes with their byways and their quagmires it is a very

labyrinth. And the country people are in league with the robbers. It is a poor

[113] country and fever-smitten, and the fishermen and hunters and peasants

find a few gold pieces mighty convenient."

"But

if you knew all this," cried

"My

dear sir," replied the man, "you are asking a little too much of me.

I would not harm a traveller for all the world: I

never did such a thing in my life, and I never will. But I can't set myself

against the whole country-side. As it is, I leave them alone and they leave me

alone. If a traveller asks me a question I give him a true answer, as far as I

know it. If your friends—I call them your friends, because you seem to know

them—had asked my advice I should have given it them fair and square; I should

have said, Keep to the old road, but I should not have said, If you go by Liternum

you will very likely fall among thieves. It would have been as much as my life

is worth to say it. Life at Sinuessa, sir, if you will believe me, is not worth

very much; still I am for holding to it as long as I can. And now, sir, if I

may make bold to advise you, I should say, Hurry on. You have got a strong

party here, and will be more than a match for the robbers. Your friends will

not be very much in advance, and you may very well [114] come up in time, if

they are attacked. Your good lady, of course, will stop here. You may trust me,

sir, to do my best for her; but if you like, leave two or three of your men by

way of a guard."

Priscilla,

as might have been expected, scouted the idea of being left behind. "You

will want every man," she said, "or, anyhow, the more you can put in

the field against these villains, the better your chance. And I, too, may be of

use."

Priscilla

had made the journey so far in a carriage. This was dispensed with for the

present. The innkeeper furnished a rough pony, which she mounted; and the party

started without losing a moment. One thing became evident after some distance

had been traversed. The guide had simply told a lie when he had recommended the

Liternum road as especially good for travelling. It was a by-road and was not

in the perfect condition which was characteristic of the great Roman Viae.

This confirmed the inn-keeper's suspicions. And these suspicions were soon to

be turned into certainty. Between the tenth and eleventh milestone—the whole

distance between Sinuessa and Liternum was fourteen miles—the sound of a horse

urged at full gallop could be plainly heard. The next minute the rider came in

view. He was a young Jew [115] who acted as body-servant to Raphael, and was

known by sight to some of the company.

"Thanks

be to the Lord of hosts!" he cried. "My

master and his father are sore beset. Those villains of guards have sold us. My

master sent me back on the chance of finding some help. As I was riding off,

one of the guards sent an arrow after me. By good luck it did nothing more than

graze my horse's off hind leg. So it was as good as a spur, and he galloped

faster than ever. But another inch would have lamed him. Hurry on, gentlemen;

there is not a moment to lose."

The

captain of the brigands felt, as soon as he caught sight of the well armed and

resolute looking party under

EASTWARD BOUND

[118] THE first care of the newcomers was Manasseh. The effect

of the incident had been to bring him perilously near to his end. Weak as he

was, he was not one to be still while so exciting a drama was being enacted

round him. He was absolutely unable to move from his place; but he sat up in the

litter, poured out invectives on the villains who had betrayed him, and

encouraged his own party to do their best in the way of resistance. Of course

there was a reaction, and when the brief conflict had ended in the flight of

the robbers, he was in a fainting condition. Priscilla had to use all her skill

and all the appliances she had at hand—she was too good a woman ever to leave

herself without some of the most important "first aids," as they were

understood at the time—before she could bring him back to consciousness. His

state was still doubtful, but he had a vigorous constitution, and what was not

less favourable for recovering, an indomitable spirit.

[119] The next question that pressed for solution was the fate of

the brigand captain. Some were for making short work with him. Why, they asked,

should they encumber themselves with a villain who had plotted to cut all their

throats? "Deal him," they cried, "the measure that he would have

dealt to us, a couple of inches of cold steel."

"He

is far too fine a fellow," he said, "to be

made food for crows and ravens. In these times it is not a bad thing to have so

stout a fellow on one's side, and you have got a chance of getting him. Make

him swear by whatever he holds sacred—all these fellows have some oath which

they do not like to forswear—that he will be faithful to you; that will be

better than handing him over to the authorities, who in all probability are

greater scoundrels than he is."

This

advice prevailed;

The

remainder of the journey to Brundisium was completed without any disturbing

incidents. When that place was reached, it became a question what was next to

be done; the usual plan followed by travellers bound eastward was to take the

shortest sea-passage—most landsmen think that the less they have of the sea the

better—to Apollonia, and proceed overland to Corinth. But this necessitated more

than one change of conveyance, and various other inconveniences, which the

condition of Manasseh, who was still hovering between death and life, rendered

peculiarly undesirable.

Raphael

was curiously different from his father, and yet even

less in sympathy with

The

voyage from Brundisium to the entrance of the

It was a

gay scene that met the travellers' eyes. Visitors were flocking to

CORINTH

[124] IT was nearly sunset on the fourth day after leaving

Brundisium when the travellers reached Lechaeum, the western

The

Jewish community was large and wealthy, as it was certain to be in any place

where commerce was in the ascendant. Manasseh had, of course, his

correspondents, who had been warned of his coming, Raphael having taken the

precaution of sending a message by the shorter overland route. A litter was in

attendance, and a physician, whose services however were scarcely needed, the

quiet voyage over the placid waters of the Gulf having been of the greatest

service to the invalid. Archias also had been apprised in the same way of the

intended arrival of

|

|

The

distance between the harbour and the city was a little less than a mile and a

half. The road was level and kept in excellent repair, with a wall strengthened

by towers and redoubts on either side (Footnote: These walls

closely resembled the Long Walls by which

A YOUNG CHAMPION

[129] THE financial business between

"My

dear sir," he exclaimed, "you will excuse me if I say that this

sounds to me very strange. You have just made a very considerable loan to the

city, and this, I imagine, is not your only investment—excuse me if I seem to

show an indiscreet curiosity as to your affairs—so that you obviously have a

sufficient income at your command, and yet you are anxious to take up a not

very interesting handicraft. What does it all mean, if I may be bold enough to

ask the question?"

"I

am following," replied

"Well,"

said Archias, "you surprise me. What would Plato have said to such a

notion? He was against allowing the handicraftsman any share in the government

of his ideal city. You have read the Republic?"

"Yes,"

replied Aquila, "I have read it with the greatest admiration, though I

should not care to live in a state so modelled—nor, I fancy, would any one

else."

"Possibly,"

said the magistrate, "but you will remember what he says:—The really good State does not make the artisan a

citizen. What do you say to that?"

"Well,"

replied the Jew, "I shall not presume to argue the question with the

greatest of the philosphers on first principles. It is not difficult, however,

to make you see our Jewish standpoint. We Jews have always felt that our

position was very precarious. We were a small people in a scrap of territory

which might be set down and fairly lost in the enormous empires on either side.

We might be torn away any day from our place and our belongings. What could be

more reasonable than that every man should be provided with [132] the means of

earning his bread in any extremity to which he might be reduced.

Your Plato, you will remember, acknowledges that a state cannot exist without

the activities which these same artisans practise. This is our justification.

Let us take care, we say, to provide ourselves with something which will make

us useful or even necessary wherever we go. We may have house, land, money