|

The

Burning of |

Table of Contents

Front Matter

The Emperor's Plan

The Hatching of a Plot

In the Circus

A New Ally

A Great Fire

Baffled

Flight

Pudens

An Imperial Musician

A Great Bribe

A Scapegoat

The Edict

In Hiding

The Persecution

What the Temple Servant Saw

What the Soldiers Thought

In the Prison

Surrender

Epicharis Acts

The Plot Thickens

Betrayed

Vacillation

A Last Chance

The Death of a Philosopher

The Fate of Subrius

A Place of Refuge

Meeting Again

Front Matter

|

|

PREFATORY NOTE

THE Claudia of this story may be

identified with the British princess whose marriage to a certain Pudens is

celebrated by Martial in a pleasant little epigram, and, possibly, with the

Claudia whose name occurs among the greetings of

THE EMPEROR'S PLAN

[1] THE reigning successor of the great

Augustus, the master of some forty legions, the ruler of the Roman world, was

in council. But his council was unlike as possible to the assembly which one

might have thought he would have gathered together to deliberate on matters

that concerned the happiness, it might almost be said,

of mankind. Here were no veteran generals who had guarded the frontiers of the

Empire, and seen the barbarians of the East and of the West recoil before the

victorious eagles of Rome; no Governor of provinces, skilled in the arts of

peace; no financiers, practised in increasing the amount of the revenue without

aggravating the burdens that the tax-payers consciously felt; no philosophers

to contribute their theoretical wisdom; no men of business to give their master

the benefit of their practical advice. Nero had such men at his call, but he

preferred, and not perhaps without reason, to confide his schemes to very

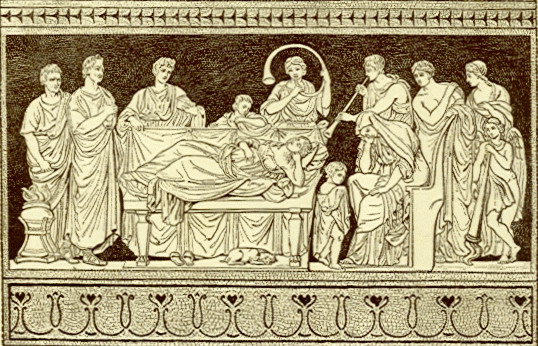

different advisers. [2] There were three persons in the Imperial Chamber; or

four, if we are to reckon the page, a lad of singular beauty of form and

feature, but a deaf mute, who stood by the Emperor's couch, clad in a

gold-edged scarlet tunic, and holding an ivory-handled fan of peacock's

feathers, which he waved with a gentle motion.

Let me begin my description

of the Imperial Cabinet, for such it really was, with a portrait of Nero

himself.

The Emperor showed to

considerable advantage in the position which he happened to be occupying at the

time. The chief defects of his figure, the corpulence which his excessive

indulgence in the pleasures of the table had already, in spite of his youth, (Footnote: Nero was now (A.D. 64) twenty-seven years of

age.) increased to serious proportions, and the unsightly thinness of his lower

limbs, were not brought into prominence. His face, as far as beauty was

concerned, was not unworthy of an Emperor, but as the biographer of the Cæsars

says, it was "handsome rather than attractive." The features were

regular and even beautiful in their outlines, but they wanted, as indeed it

could not be but that they should want, the grace and charm in which the beauty

of the man's nature shines forth. The complexion, originally fair, was flushed

with intemperance. There were signs here and there of what would soon become

disfiguring blotches. The large [3] eyes that in childhood and boyhood had been

singularly clear and limpid were now somewhat dull and dim. The hair was of the

yellow hue that was particularly pleasing to an Italian eye, accustomed, for

the most part, to black and the darker shades of brown. Nero was particularly

proud of its color, so much so indeed, that, greatly to the disgust of more

old-fashioned Romans, he wore it in braids. On the whole his appearance, though

not without a certain comeliness and even dignity, was forbidding and sinister.

No one that saw him could give him credit for any kindness of heart or even

good nature. His cheeks were heavy, his chin square, his

lips curiously thin. Not less repulsive was the short bull neck. At the moment

of which I am writing his face wore as pleasing an expression as it was capable

of assuming. He was in high spirits and full of a pleased excitement. We shall

soon see the cause that had so exhilarated him.

Next to the Emperor, by

right of precedence, must naturally come the Empress,

for it was to this rank that the adventuress Poppæa had now succeeded in

raising herself. Her first husband had been one of the two commanders of the

Prætorian Guard; her second, Consul and afterwards Governor of a great

province, destined indeed himself to occupy for a few months the Imperial

throne; her third was the heir of Augustus and Tiberius, the last of the Julian

Cæsars. Older than the Emperor, for she had [4] borne a child to her first

husband more than twelve years before, she still preserved the freshness of

early youth. Something of this, perhaps, was due to the extreme care which she

devoted to her appearance, (Footnote: It is said

that she daily bathed in asses' milk) but more to the expression of innocence

and modesty which some strange freak of nature—for never surely did a woman's

look more utterly belie her disposition—had given to her countenance. To look at

her certainly at that moment, with her golden hair falling in artless ringlets

over a forehead smooth as a child's, her delicately arched lips, parted in a

smile that just showed a glimpse of pearly teeth, her cheeks just tinged with a

faint wild-rose blush, her large, limpid eyes, with just a touch of wonder in

their depths, eyes that did not seem to harbour an evil thought, any one might

have thought her as good as she was beautiful. Yet she was profligate,

unscrupulous, and cruel. Her vices had always been calculating, and when a

career had been opened to her ambition she let nothing stand in her way. Nero's

mother had perished because she barred the adventuress' road to a throne, and

Nero's wife soon shared the fate of his mother.

The third member of the

Council was, if it is possible to imagine it, worse than the other two. Nero

began his reign amidst the high hopes of his subjects, and for a few weeks, at

least, did not disappoint them, and Josephus speaks of Poppæa as a

"pious" woman; [5] but we hear nothing about Tigellinus that is not

absolutely vile. Born in poverty and obscurity, he had made his way to the bad

eminence in which we find him by the worst of arts. A man of mature age, for by

this time he must have numbered at least fifty years, he used his greater

experience to make the young Emperor even worse than his natural tendencies,

and all the evil influences of despotic power, would have made him. And he was

what Nero, to do him justice, never was, fiercely resentful of sarcasm and

ridicule. Nero suffered the most savage lampoons on his character to be

published with impunity, but no one satirized Tigellinus without suffering for

his audacity.

The scene of the Council

was a pleasant room in the Emperor's seaside villa at Antium. This villa was a

favourite residence with him. He had himself been born in it. Here he had

welcomed with delight, extravagant, indeed, but yet not wholly beyond our

sympathies, the birth of the daughter whom Poppæa had borne to him in the

preceding year; here he had mourned, extravagantly again, but not without some

real feeling, for the little one's death. It was at Antium, far from the wild

excitement of

The subject which now engaged

his attention, and the attention of his advisers, was one that seemed of a

harmless and even a laudable kind. It was nothing less than a magnificent plan

for the rebuilding of [6]

"Augustus," he

said, after enjoying for a time his companions' unfeigned surprise, "said

that he found a city of brick and left a city of marble. I mean to be able to

boast that I left a new city altogether. Indeed, I feel that nothing short of

this is worthy of me, and I thank the gods that have left for me so magnificent

an opportunity."

"And this vacant

space," asked Tigellinus, after [7] various details had been explained by

the Emperor: "What do you mean, Sire, to do with this?"

A huge blank had been left

in the middle of the map, covering nearly the whole of the

"That is meant to be

occupied by my palace and park," said the Emperor.

The Prime Minister, if one

may so describe him, could not restrain an involuntary gesture of surprise.

Nero's face darkened with

the scowl that never failed to show itself at even the slightest opposition to

his will.

"Think you,

then," he cried in an angry tone, "that it is too large? The Master

of Rome cannot be lodged too well."

Tigellinus felt that it

would be safer not to criticise any further. Poppæa, who, to do her justice,

was never wanting in courage, now took up the discussion. The objection that

she had to make was in keeping with a curious trait in her character.

"Pious" she certainly was not, though Josephus saw fit so to describe

her, but she was unquestionably superstitious. The terrors of an unseen world,

though they did not keep her back from vice and crime, were still real to her.

She did not stick at murder; but nothing would have induced her to pass by a

temple without a proper reverence. This feeling quickened her insight into an

aspect of the matter which her companion had failed to observe.

[8] "You will buy the

houses which you will have to pull down?" she said.

"Certainly," the

Emperor replied; "that will be an easy matter."

"But there are

buildings which it will not be easy to buy."

The scowl showed itself

again on Nero's face.

"Who will refuse to

sell when I want to buy?" he cried. "And besides, you may be sure

that I shall not stint the price."

"True, Sire, but there

are the temples, the chapels; they cannot be bought and sold as if they were

private houses."

Nero started up from his

couch, and paced the room several times. He could not refuse to see the

difficulty. Holy places were not to be bought and pulled down as if they were

nothing but so many bricks and stones.

"What say you,

Tigellinus?" he cried after a few minutes of silence. "Cannot the

Emperor do what he will? Cannot the priests or the augurs, or some one smooth

the way? Speak, man!" he went on impatiently, as the minister did not

answer at once.

"The gods forbid that

I should presume to limit your power!" said Tigellinus. "But yet—may

I speak freely?"

"Freely!" cried

Nero; "of course. When did I ever resent the truth?"

Tigellinus repressed a

smile. His own rise was certainly not due to speaking the truth. He went on:—

[9] "One sacred

building, or two, or even three, might be dealt with when some great

improvement was in question. That has been done before, and might be done

again, but when it comes to a matter of fifty or sixty, or even a hundred,—very

likely there are more, for they stand very thick in the old city,—the affair

becomes serious. I don't say it would be impossible, but there would be delay,

possibly a very long delay. The people feel very strongly on these things. Some

of these temples are held in extraordinary reverence, places that you, Sire,

may very likely have never heard of, but which are visited by hundreds daily.

To sweep them away in any peremptory fashion would be dangerous. There would

have to be ceremonies, expiations, and all the thousand things which the

priests invent."

"Well," exclaimed

the Emperor after a pause, "what is to be done?"

"Sire," replied

Tigellinus, "cannot you modify your plan? Much might be done without this

wholesale destruction."

"Modify it!"

thundered the Emperor. "Certainly not. It shall

be all or nothing. Do you think that I am going to take all this trouble, and

accomplish, after all, nothing more than what any ?dile

could have done?"

He threw himself down on

the couch and buried his face in the cushions. The Empress and the Minister

watched and waited in serious disquiet. There [10] was no knowing what wild

resolve he might take. That he had set his heart to no common degree on this

new scheme was evident. In all his life he had never given so much serious

thought to any subject as he had to this, and disappointment would probably

result in some dangerous outburst. After about half an hour had passed, he

started up.

"I have it," he

cried; "it shall be done,—the plan, the whole plan."

"Sire, will you deign

to tell us what inspiration the gods have given you?" said Tigellinus.

"All in good

time," said the Emperor. "When I want your help I will tell you what

it is needful for you to know. But now it is time for my harp practice. You

will dine with us, Tigellinus, and for pity's sake bring some one who can give

us some amusement. Antium is delightful in the daytime, but the

evenings! . . ."

"Madam," said

Tigellinus, when the Emperor had left the room, "have you any idea what he

is thinking of?"

"I have absolutely

none," replied Poppæa; "but I fear it may be something very strange.

I noticed a dangerous light in his eyes. It has been there often lately. Do you

think," she went on in a low voice, "there is any danger of his going

mad? You know about his uncle Caius." (Footnote:

The fourth Emperor, commonly called Caligula.)

"Don't trouble

yourself with such fears," replied [11] Tigellinus. "It is not

likely. His mother had the coolest head of any woman that I have ever seen; and

his father, whatever he was, was certainly not mad. And now, if you will excuse

me, I have some business to attend to."

He saluted the Empress and

withdrew. Poppæa, little reassured by his words, remained buried in

thought,—thought that was full of disquietude and alarm. She had gained all,

and even more than all, that she had aimed at. She shared Nero's throne, not in

name only, but in fact. But how dangerous was the height to which she had

climbed! A single false step might precipitate her into an abyss which she

shuddered to think of. He had spared no one, however near and dear to him. If

his mood should change, would he spare her? And his mood might change. At

present he loved her as ardently, she thought, as ever. But—for she watched him

closely, as a keeper watches a wild beast—she could not help seeing that he was

growing more and more restless and irritable. Once he had even lifted his hand

against her. It was only a gesture, and checked almost in its beginning, but

she could not forget it. "Oh!" she moaned to herself,—for, wicked as

she was, she was a woman after all,—"Oh, if only my little darling had

lived! Nero loved her so, and she would have softened him. But it was not to

be! Why did I allow them to do all these foolish idolatries? And yet, how could

I stop it? Still, I am sure that God [12] was angry with me about them, and

took the child away from me. And now there are these new troubles. I will send

another offering to

Poor creature! the thought of a sacrifice of justice and mercy never

entered into her soul.

THE HATCHING OF A PLOT

[13] ON the very day of the meeting

described in my last chapter, a party of six friends was gathered together in

the dining-room—I should rather say one of the dining-rooms—of a country house

at Tibur. The view commanded by the window of the apartment was singularly

lovely. Immediately below, the hillside, richly wooded with elm and chestnut,

and here and there a towering pine, sloped down to the lower course of the

river Anio. Beyond the river were meadow-lands, green with the unfailing

moisture of the soil, and orchards in which the rich fruit was already

gathering a golden hue. The magnificent falls of the river were in full view,

but not so near as to make the roar of the descending water inconveniently

loud. At the moment, the almost level rays of the setting sun illumined with a

golden light that was indescribably beautiful the cloud of spray that rose from

the pool in which the falling waters were received. It was an effect that was

commonly watched with intense interest by visitors to the villa, for, indeed,

it was just one of the beauties of nature which a Roman knew how to appre- [14]

ciate. Landscape, especially of the wilder sort, he did not care about; but the

loveliness of a foreground, the greenery of a rich meadow, the deep shade of a

wood, the clear water bubbling from a spring or leaping from a rock, these he

could admire to the utmost. But on the present occasion the attention of the guests

had been otherwise occupied. They had been listening to a recitation from their

host. To listen to a recitation was often a price which guests paid for their

entertainment, and paid somewhat unwillingly and even ungraciously. Rich dishes

and costly wines, the rarest of flowers, and the most precious of perfumes were

not very cheaply purchased by two hours of boredom from some dull oration or

yet duller poem. There was no such feeling among the guests who were now

assembled in this

|

"Italian

fields of death, the blood-stained wave That swept

Sicilian shores, and that dark day That reddened |

(Footnote: A free translation of the last two lines of

C. VIII. Hesperi? clades et

flebilis unda Pachyni, Et Mutina, et Leucas puros fecere Philippos.) It was

followed by a round of genuine, even enthusiastic applause. When the applause

had subsided there was an interval of silence that was scarcely less

complimentary to the poet. This was broken at last by a remark from Licinius, a

young soldier who had lately been serving against the Parthians under the great

Corbulo, for many years the indefatigable and invincible guardian of the

Eastern frontier of the Empire.

"Lucan," he said,

"would you object to repeat a [16] few lines which occurred in your

description of the sacrifices on either side before the beginning of the

battle? We heard how all the omens were manifestly unfavourable to Pompey, and

then there followed something that struck me very much about the prayers and

vows of Cæsar."

"I know what you mean," replied the poet; "I will repeat them with pleasure. They run thus:—

|

" 'But

what dark thrones, what Furies of the pit, Cæsar, didst

thou invoke? The wicked hand That waged with

pitiless sword such impious war Not to the

heavens was lifted, but to Gods That rule the

nether world and Powers that veil Their maddening presence in Eternal night.' " |

"Exactly so,"

said Licinius. "Those were the lines I meant. But will you recite this in

public? How will Nero, who, after all, is the heir of Cæsar, and enjoys the

harvests reaped at Mutina, and

"He is not likely to

hear it. In fact, he has forbidden me to recite. He does not like rivals,"

he added with an air of indescribable scorn.

"Indeed," said

the young soldier; "then you have seen reason to change your opinions. I

remember having the great pleasure of hearing you read your first book. I was

just about to start to join my legion. It must have been about two years ago. I

can't exactly recollect the lines, but you mentioned, [17] I remember, Munda,

and Mutina, and

|

" 'Yet

great the debt our Roman fortunes owe To civil strife,

if this its end, to make Great Nero lord of men. . . .' " |

The other guests grew hot

and cold at the more than military frankness with which their companion taxed

their host with inconsistency. The inconsistency was notorious enough; but now

that the poet had abandoned his flatteries and definitely ranged himself with

the opposition, what need to recall it?

Lucan could not restrain

the blush that rose to his cheek, but he was ready with his answer.

"The Nero of to-day is

not the Nero of three years ago, for it was then that I wrote those

lines."

"Yet even then," whispered

another of the guests to his neighbour, "he had murdered his brother and

his mother."

A somewhat awkward silence

followed. Subrius, a tribune of the Prætorians, broke it by addressing himself

to Licinius.

"Licinius," he

cried, "tell our friends what you were describing to me the other

day."

"You mean," said

Licinius, "the ceremony of Tiridates' submission?"

"Exactly,"

replied Subrius.

"Well," resumed

the other, "it was certainly a sight that was well worth seeing. A more

magnifi- [18] cent army than the Parthian's never was. How the King could have

given in without fighting I cannot imagine, except that Corbulo fairly

frightened him. I could hardly have believed that there were so many

horse-soldiers in the world. But there they were, squadron after squadron,

lancers, and archers, and swordsmen, each tribe with its own device, a serpent,

or an eagle, or a star, or the crescent moon, till the eye could hardly reach

to the last of them. The legions were ranged on the three sides of a hollow square,

with a platform in the centre, and on the platform an image of the Emperor,

seated on a throne of gold."

"A truly Egyptian

deity!" muttered the poet to himself.

"King Tiridates,"

the soldier went on, "after sacrificing, came up, and kneeling on one knee,

laid his crown at the feet of the statue."

"Noble sight

again!" whispered Lucan to his neighbour. "A man

bowing down before a beast."

"And

Corbulo?" asked one of the guests, Lateranus by name, who had not hitherto

spoken.

"How did he bear himself on this occasion?"

"As modestly as the

humblest centurion in the army," replied Licinius.

"Yes, it was a

glorious triumph for

He paused, and looked with

a meaning glance at Lateranus.

[19] Lateranus, who was

sitting by the side of Lucan (indeed, it was to him that the poet had whispered

his irreverent comments on the ceremony by the

"Will you excuse

me?" he said to the host, and walking to the door opened it, examined the

passage hat led to it, locked another door at the further end, and then

returned to his place.

"Walls have

ears," he said, "but these, as far as I can judge, are deaf. We can

all keep a secret, my friends?" he went on, looking round at the company.

"To the death, if need

be," cried Lucan.

The four other guests murmured

assent.

"We may very likely be

called upon to make good our words. If any one is of a doubtful mind, let him

draw back in time."

"Go on; we are all

resolved," was the unanimous answer of the company.

Did there seem nothing

strange to you when our friend Licinius told us of the Parthian king laying his

crown at the feet of Nero's statue? What has Nero done that he should receive

such gifts? Our armies defend with their bodies the frontiers of

"The man and the sword

will not be wanting when the proper time shall come," said Subrius the

Prætorian in a tone of grim resolve. "But

"Why not restore the

Republic?" cried Lucan. "We have a Senate,

we have Consuls, and all the old machinery of the Government of freedom. The

great Augustus left these things, it would seem, of

set purpose, against the day when they might be wanted again."

"The Republic is

impossible," cried Subrius; "even [21] more impossible than it was a

hundred years ago. What is the Senate but an assembly of worn-out nobles and

cowardly and time-serving capitalists? I know there are exceptions; one of them

is here to-night," he went on with a bow to Lateranus; "and there is

Thrasea, who, I know, will make one of us, as soon as he knows what we are

meditating. But the Senate as a whole is incapable. And the people, where is

that to be found? Certainly not in this mob that cares for nothing but its dole

of bread, its gladiators, and its chariot-races. No; the Republic is a dream.

"What say you of

Corbulo, Licinius?" asked Sulpicius Asper, a captain of the Prætorians,

who had hitherto taken no part in the conversation. "His record is not

altogether spotless. But he is a great soldier, and one might conjure with his

name. And then his presence is magnificent, and the people love a stately

figure. Do you think that the thought has ever crossed his mind?"

"Corbulo,"

replied Licinius, "is a soldier, and nothing but a soldier. And he is

absolutely devoted to the Emperor. I remember how ill he took it when some one

at his table said something that sounded like censure. 'Silence!' he thundered.

'Emperors and gods are above praise and dispraise.' I verily believe that if

Nero bade him kill himself he would plunge his sword into his breast without a

murmur. [22] No, it is idle to think of Corbulo. In fact he is one of the great

difficulties that we should have to reckon with. Happily he is far off, and the

business will be done before he hears of it."

"There is Verginius on

the

"An

able man, none abler, if he will only consent."

"And

Sulpicius Galba in

"He is half

worn-out," said Lateranus; "but he has the advantage of being one of

the best born men in

"Why not a

philosopher?" asked Lucan after a pause. "Plato thought that

philosophers were the fittest men to rule the world."

"Are you thinking of

your uncle Seneca?" asked Lateranus. "For my part I think that it

would be a pity to take him away from his books; and to speak the truth, if I

may do so without offence, Seneca, though he is beyond doubt one of the

greatest ornaments of Rome, has not played the part of an Emperor's teacher (Footnote: Seneca, in conjuction with Burrus, commander

of the Prætorians, was tutor to Nero for many years.) with

such success that we could hope very much from him, were he Emperor

himself."

"There are, and indeed

must be, objections to every name," said Licinius after a pause. "The

soldiers will take it ill if the dignity should go to a civilian; and if the

choice falls on a soldier, then all the other [23] soldiers will be jealous.

Tell me, Subrius, would you Prætorians be content if the legions were to choose

an Emperor?"

Subrius shrugged his

shoulders.

"As for the armies of

the East," Licinius went on, "I know how fiercely they would resent

dictation from the West! Our friend Asper here, who, if I remember right, has

been aide-de-camp to Verginius, knows whether the German legions would be more

disposed to submit to a mandate from the

Asper could do nothing

better than imitate the action of his superior officer.

Licinius went on: "I

am a soldier myself, and can therefore speak more freely on this subject. We

have to choose between evils. Jealousy between one great army and another can

scarcely fail to end in war. The general discontent of all the armies, if a

civilian succeeds to the throne, will be less acute, and therefore less dangerous.

What say you to Calpurnius Piso?"

"At least," cried

Lucan, "he has the merit of not being a philosopher."

There was a general laugh

at this sally. Piso was a noted bon vivant and

man of fashion, and generally as unlike a philosopher in his habits and ways of

life as could be conceived.

"Exactly so,"

said Licinius, undisturbed by the remark; "and this, strange as it may

seem, is one of [24] the qualities which commend him to those who look at

things as they are, and not as they ought to be. This is not the time for

Consuls who leave their ploughs to put on the robes of office. The age is not

equal to such simple virtues. It wants magnificence; it demands that its heroes

should be well-dressed and drive fine horses and keep up a splendid establishment.

It is not averse to a reputation for luxury. Piso has such a reputation, and I

must own that it does not do him injustice. But he is a man of honour, and he

has some solid and many showy qualities. He has noble birth; a pedigree that

shows an ancestor who fought at Cann? is more than

respectable. He is eloquent, he is wealthy, but can give with a liberal hand as

well as spend, and he has the gift of winning hearts. And then he is bold. We

may look long, my friends, before we find a better man than Piso."

"There is a great deal

of truth in what you say; more truth than it is pleasant to acknowledge,"

said Lateranus. "But we must weigh this matter seriously. Meanwhile, will

Piso join us?"

"I feel as certain of

it as I could be of any matter not absolutely within my knowledge,"

replied Licinius. "Will you authorize me to sound him? Whether he agree or not, I can guarantee his silence."

Many other matters and men

were discussed; and before the party separated it was arranged that each of the

six friends should choose one person to be enrolled in the undertaking.

IN THE CIRCUS

[25] TWO days after the conversation related

in my last chapter Subrius and Lateranus were deep in consultation in the

library of the latter's mansion on the Esquiline Hill. The subject that

occupied them was, of course, the same that had been started on that occasion.

"Licinius tells

me," said the Prætorian, "that he has spoken to Piso, and that he

caught eagerly at the notion. I must confess that at first I was averse to the

man. It seemed a pity to throw away so magnificent an opportunity. What good

might not an honest, capable man do, if he were put in this place? It is no

flattery, but simple truth, that the Emperor is a Jupiter on earth. But it

seems hopeless to look for the ideal man. That certainly Piso is not. But he is

resolute, and he means well, and he will be popular. He is not the absolute

best, the four-square and faultless man that the philosophers talk about; very

far from it. But then the faultless man would not please the Romans, if I know

them; and to do the Romans, or, for the matter of that, any men, good, you must

please them first."

[26] "And how does the

recruiting go on?" asked Lateranus.

"Excellently

well," said Subrius, "within the limits that are set, that every man

should choose one associate. Asper and Sulpicius have both chosen comrades, and

can answer for their loyalty as for themselves. Lucan has taken Scævinus. I

should hardly have thought that the lazy creature had so much energy in him;

but these sleepy looking fellows sometimes wake up with amazing energy.

Proculus has chosen Senecio, who is one of the Emperor's inner circle of friends."

"Ah!" interrupted

Lateranus, "that sounds dangerous."

"There is no cause for

fear; Senecio, I happen to know, has very good reasons

for being with us, and, of course, he is a most valuable acquisition. When the

hour comes to strike, we shall know how and where to deal the blow. Then there

is Proculus, whom you have chosen. And finally I, I flatter myself, have done

well. Whom think you I have secured?"

"Well, it would be

difficult to guess. Your fellow tribune Statius, perhaps.

I should guess that he is an honest man, who would like to serve a better

master than he has got at present."

"Statius is well

enough, and we shall have him with us sure enough when the time shall come. But

meanwhile I have been doing better things than [27] that. What should you

say," he went on, dropping his voice to a whisper, "if I were to tell

you that it is Fænius Rufus?"

"What, the

Prefect?" asked Lateranus in tones of the liveliest surprise.

"Yes" replied

Subrius; "the Prefect himself."

"That is

admirable!" cried the other. "We not have hoped for anything so good.

But how did you approach him?"

"Oh! that was not so difficult. To tell you the truth, he met me

at least half-way. These things are always in the air. Depend upon it, there are hundreds of people thinking much the same

things that you and I are thinking, though not, perhaps, in quite so definite a

way. And why not? The same causes have been at work in

them as in us, and brought about much the same result."

"True! but we must be first in the field. So we must make

haste."

"There I agree

heartily with you. Delay in such matters is fatal. The secret is sure to leak

out. And with every new man we take into our confidence—and we must add a good

many more to our number—the danger becomes greater. Will you come with me on a

little visit that I am going to pay? I have an acquaintance whom

I should like you to see. He may be useful to us in this matter. I will tell

you about him. In the first place, I would have you know that my friend is a

gladiator."

[28] Lateranus raised his

eyebrows. "A gladiator!" he exclaimed in a doubtful tone. "He

might be useful in certain contingencies. But he would hardly suit our purpose

just now."

"Listen to his

story," said Subrius. "I assure you that it is well worth hearing;

and I shall be much surprised, if, when you have heard it, you don't agree with

me that Fannius, for that is my friend's name, is a very fine fellow. Well, to

begin with, he is a Roman citizen."

"Great Jupiter!"

interrupted Lateranus, "you astonish me more and more. A citizen

gladiator, and yet a fine fellow! I never knew one that was not a

thorough-paced scoundrel."

"Very likely,"

replied the Prætorian calmly. "Yet Fannius you will find to be an

exception to your rule. But to my story. The elder

Fannius rented a farm of mine three or four miles this side of Alba. He might

have made a good living out of it. There was some capital meadow land, a fair

vineyard, and as good a piece of arable as is to be found in the country. His

father had had it before him. In fact, the family were old tenants, and the

rent had never been raised for at least a hundred years. Then there was only

one son, and he was a hard-working young fellow who more than earned his own

keep. The father ought, I am sure, to have laid by money; but he was one of

those weak, good-natured fellows, who seem incapable of keeping a single denarius in their pock- [29] ets. It is only fair to say that

he was always ready to share his purse with a friend. In fact, his practice of

foolishly lending helped him to his ruin as much as anything else. That, and

the wine-cup, and the dice-box were too much for him. About five years ago, a

brother-in-law—his dead wife's brother, you must understand—died suddenly,

leaving an only daughter, with some fifty thousand sesterces for

her fortune, not a bad sum for a girl in her rank of life. He had been living,

if I remember right, at Tarentum, and, knowing nothing about his

brother-in-law's embarrassments, he had naturally made him his daughter's

guardian and trustee. Fannius, who was at his wit's end to know where to find

money, his farm being already mortgaged up to the hilt, accepted the trust only

too willingly. The son, disgusted at seeing extravagance and waste which he

could not stop, had gone away from home, and was serving under Corbulo. Perhaps

if he had been here, he might have been able to put a stop to the business. Well,

to make a long story short, the elder Fannius appropriated the money little by

little. Of course he was always intending to make it good. There was to be a

good harvest, or a good vintage, or, what, I believe, he really trusted in more

than anything else, a great run of luck at the gaming-table. Equally of course

he never got anything of the kind. Then came the

crash. The younger Fannius came back with his discharge from the East, [30] and

found his father lying dead in the house. There can be no doubt he had killed

himself. The son discovered in the old man's desk a letter addressed to himself

in which he told the whole story. The girl was living with an aunt. He had

always continued, somehow or other, to pay the interest on her money. She was

going to be married, and the capital would have to be forthcoming. This, I take

it, was the final blow, and the old man saw no other way of getting out of his

trouble but suicide. Suicide, by the way, is pretty often a way of shoving

one's own trouble on to somebody else's shoulders. Well, the poor fellow came

to me. He had brought home a little pay and prize-money. I forgave him what

rent was due, and bought whatever there was to sell on the farm—not that there

was much of this, I assure you. So he got a little sum of money together,

enough to pay the old man's debts. But then there was the niece's fortune. How

was that to be raised? It was absolutely gone; not a denarius of it left. I would have helped if I could, but I was

positively at the end of my means. Still I could have raised the money, if I

had known what young Fannius was going to do. But he said nothing to me or to

any one else. He went straight to the master of the gladiators' school and

enlisted. You see his strength and skill in arms were all he had to dispose of,

and so, to save his father's honour and his cousin's happiness, he sold them,

and, of course, himself with them. It [31] was indeed selling himself. You

know, I dare say, how the oath runs which a free man takes when he enlists as a

gladiator?"

"No; I do not remember

to have heard it."

"Well, it runs thus:—

" 'I, Caius

Fannius, do take hereby the oath of obedience to Marius, that I will consent to

be burnt, bound, beaten, slain with the sword, or whatever else the said Marius

shall command, and I do most solemnly devote both soul and body to my said

master, as being legally his gladiator.'

"The young man had no

difficulty in making good terms for himself. He was the most famous swordsman

of his tribe. Indeed, I don't know that he had his match in the whole Field of

Mars. He got his fifty thousand sesterces, paid the money over just in

time to prevent the truth coming out, and thus cheerfully put his neck under

this yoke. What do you say to that? Have I made good my words?"

"To the full,"

cried Lateranus enthusiastically. "He is a hero; nothing less."

The two friends had by this

time arrived at their destination, "the gladiators' school," as it

was called, kept by a certain Thraso. Subrius inquired at one of the doors

whether he could see Fannius, the Samnite—for it was in this particular corps

of gladiators, distinguished by their high-crested helmet and oblong shield,

that the young man was enrolled.

"He has just sat down

to the

[32] "Then we will not

disturb him, but will wait till he has finished," replied Subrius.

"Would you like to see

the boys at their exercises, sir?" asked the man, an old Prætorian, who

had served under Subrius when the latter was a centurion. "They have their

meal earlier, and are at work now."

"Certainly," said

Subrius, and the doorkeeper called an attendant, who conducted the two friends

to the training-room of the boys.

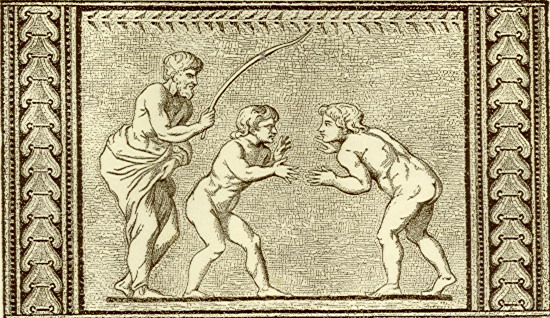

It was a curious spectacle

that met their eyes. The room into which they were ushered was of considerable

size and was occupied at this time by some sixty lads, ranging in age from ten

to sixteen, who were practising various games or exercises under the eyes of

some half-a-dozen instructors. Some were leaping over the bar, either unaided

or with the help of a pole; others were lunging with blunt swords at lay

figures; others, again, were practising with javelins at a mark. With every

group there stood a trainer who explained how the thing was to be done, and

either praised or blamed the performance. Every unfavourable comment, it might

have been noticed, was always emphasized by the application of a whip. Did the

competitor fail to clear the bar at a certain height, fixed according to his

age and stature, did he strike the lay figure outside a certain line which was

supposed to mark the vital parts, did his javelin miss the mark by a certain

distance, the whip descended [33] with an unfailing certainty on the unlucky

competitor's shoulders. Even the vanquished of two wrestlers, whose obstinate

struggle excited a keen interest in the visitors, met with the common lot,

though he had shown very considerable skill, and had indeed been vanquished

only by the superior weight and strength of his adversary.

|

|

From the boys' apartment

the friends went in to see the wild beasts.

The show of these creatures

was indeed magnificent, and, in fact, unheard of sums had been expended on

obtaining them. The Emperor was determined to outdo all his predecessors in the

variety and splendour of his exhibitions. Nor were his extravagances wholly

unreasonable. A ruler who was not a soldier, who could not, therefore,

entertain the Roman populace with the gorgeous display of a triumph, had now to

fall back upon other ways of at once keeping them in good humour and impressing

them with a sense of his greatness. The whole world, so to speak, had been

ransacked to make the collection complete. Twenty lions, magnificent specimens

most of them, had been brought from

"I am told, sir,"

said the doorkeeper, "that they cost, one with another, fifty thousand sesterces apiece. [34] It is the taking them alive, you see,

that makes it so expensive. And the pits, too, which are one way of doing this,

often break their bones. So they are mostly netted; and netting a lion is nasty

work. That fellow there"—he pointed as he spoke to a particularly powerful

male—"killed, they tell me, four men before they got him into the

cage."

Next to the lions were the

tigers. They, it seemed, had been even more costly than their neighbours, for

they had come considerably further. Secured among the

The man was particularly

communicative about the elephants. An Indian, he said, had been hired to bring

over a troop of performing animals of this kind, and their cleverness and

docility were almost beyond belief.

"One of them," he

told Subrius and his compan- [35] ion," can write his name with his trunk

in Greek characters on the sand. Another has got, the keeper tells me, as far

as writing a whole verse. A third can add and subtract. This last, having

failed one day in his task, and being docked of part of his food, was found

studying his lesson by himself in his house. You smile, sir," he said,

seeing that Lateranus could not keep his countenance. "I only tell you

what the keeper told me, but I can almost believe anything after what I have

seen myself. And then their agility, sir, is something marvellous, even

incredible. Who would think that these big creatures, which look so clumsy, can

walk on a tight-rope. Yet that I have seen with my own

eyes. And the man promises a more wonderful display than that. We are to have

four elephants walking on the tight-rope and carrying between them a litter

with a sick companion in it." At this the friends laughed outright.

"Clemens," said

Subrius, "what traveller's tales (Footnote:

Pliny the elder relates in his Natural History

these stories and others still more wonderful about the sagacity and

agility of elephants. He seems to speak of his own knowledge. Born A.D. 23, he

writes about events which happened at the very time to which my story refers.) are these?"

"I can only say,"

returned the man, "that my head is all in a whirl from what I have seen

with my own eyes and heard during the last few days."

"Fannius will have

finished by this time," said [36] Subrius, when they had completed the

round of the cages. "Lead the way, Clemens."

It was a singular sight

that presented itself to the two friends as they stood surveying the scene at

the door of the room in which the gladiators had been taking their meal. It was

a large chamber, not less than a hundred feet in length by

about half as many in breadth. The number of gladiators was about

eighty, but as this was one of the afternoons on which the men were accustomed

to receive their relatives and friends, there must have been present nearly

four times as many persons. Some of the better known men were surrounded by

little circles of admirers, who listened to everything that they had to say

with a devotion at least equal to that with which the

students of philosophy or literature were accustomed to hang upon the lips of

their teachers. The gladiators bragged of what they had done or were about to do, or, putting themselves into attitudes, rehearsed a

favourite stroke, or explained one of those infallible ways to victory which

seem so often, somehow or other, to end in defeat. Others sat in sullen and

stupid silence, others were already asleep, somnolence being, as Aristotle had

long before remarked, a special characteristic of the athletic habit of body.

The men were of various types and races, but the faces were, almost without

exception, marked by strong passions and low intelligence.

"On the whole,"

said Lateranus, after watching [37] the scene for a few minutes, "I prefer

the brutes that do not pretend to be men. Lions and tigers are far nobler

animals than these wretches; and as for elephants, whether or no we believe our

friend Clemens' marvellous stories about them, it would be an insult even to

compare them, so gentle, so teachable, so sagacious as they are, with these

savages."

"True in a general

way," said the Prætorian, "yet even here Terence's dictum (Footnote: "Homo sum; nihil humani a me alienum

puto." "I am a man; I think nothing that concerns mankind beyond my

sympathies.") could be applied. Even here there

is something of human interest. Look at that stout fellow there."

Lateranus turned his eyes

in the direction to which his companion pointed. The "stout fellow"

was a gigantic negro.

"Good Heavens!"

cried Lateranus in astonishment, for a pure-blood negro

was still a somewhat uncommon sight in

"No," replied the

Prætorian, who had a soldier's appreciation of an athletic frame. "If so, they have trained it very well. I warrant he

will be an awkward adversary for any one whom the lot may match with him when

the day shall come."

"May be," said

the other; "but what a face! what lips! what a nose! what hair! To think

that nature should ever have created anything so hideous!"

[38] "But see,"

cried Subrius, "there is one person at least who seems not to have found

our black friend so very unsightly."

And, indeed, at the moment

there came up to the negro a pretty little woman whose

fair complexion and diminutive stature exhibited a curious contrast to his

ebony hue and gigantic proportions. To judge from the blue colour of her eyes

and the reddish gold of her hair, she was a

"See," cried

Lateranus, "Hector, Andromache, and Astyanax over again! Only Hector seems

to have borrowed for the time the complexion of Memnon!"

"But we are forgetting

our friend Fannius," said Subrius. "Where is he? Ah! there I see

him," he exclaimed, after scanning for a minute or so the motley crowd

which so thronged the room as to make it difficult to distinguish any one

person. "And he, too, seems to have an Andromache. I thought he [39] was

an obstinate bachelor. But in that matter there are no surprises for a wise

man."

Fannius was just at that

moment bidding farewell to two women. About the elder of the two there was

nothing remarkable. She was a stout, elderly, commonplace person, respectably

dressed in a style that seemed to indicate the wife of a small tradesman or

well-to-do mechanic. The younger woman was a handsome, even distinguished

looking girl of one and twenty or thereabouts. Her features were Greek, though

not, perhaps, of the finest type. A deep brunette in complexion, she had soft,

velvety brown eyes that seemed to speak of a mixture of Syrian blood. This,

too, had given an arch to her finely chiselled nose, and a certain fulness,

which was yet remote from the suspicion of anything coarse, to her crimson

lips. Perhaps her mouth was her most remarkable feature. Any one who could read

physiognomies would have noticed at once the firmness of its lines. The chin,

just a little squarer than an Apelles, seeking absolutely ideal features for

his Aphrodite, would perhaps have approved, but still delicately moulded,

harmonized with the mouth. So did the resolute pose of her figure, and the

erect, vigorous carriage of the head. She was dressed in much the same manner

as the elder woman, naturally with a little more style, but with no pretension

to rank. Yet at the moment when the two friends observed the group she was

reaching her hand to [40] Fannius with the air of a princess, and the gladiator

was kissing it with all the devotion of a subject. The next moment she dropped

a heavy veil over her face and turned away.

The gladiator stood looking

at her as she moved away, so lost in thought that he did not notice the

approach of Subrius and his companion.

"Well, Fannius,"

cried the Prætorian, slapping him heartily on the shoulder, "shall we find

you, too, keeping festival on the Kalends of March?" (Footnote: The first day of March, when husbands and

wives joined in praying to Juno Lucina for the happiness and continuance of

their married life. Horace begins a well-known ode by supposing M?cenas to wonder what he, a bachelor, is doing with his

festal preparations on the first of March ("Martius C?lebs quid agam

Kalendis," etc., c. III. 8), and accounts for it by saying that the day

was the anniversary of a wonderful escape that he had had from being killed by

the fall of a tree.)

Fannius turned round and saluted.

The Prætorian, after formally returning the salute, warmly clasped his odd

acquaintance by the hand, a token of friendship which made the gladiator, who

remembered only too acutely the degradation of his position, blush with

pleasure.

"You are pleased to

jest, noble Subrius, about the worshipful goddess. What has a poor gladiator,

who cannot call his life his own for more than a few hours to do with marriage?

And Epicharis, though Venus knows I love her as my own soul, has her thought on

very different matters."

[41] "Well, well,

never despair!" returned the Tribune. "Venus will touch the haughty

fair some day with her whip. But, Fannius, when are you coming to see me? It

seems an age since we had a talk together. My friend here, too, who is to be Consul

next year, wishes to make your acquaintance."

"I am not my own

master, you know; but if I can get leave, I will come

to-night."

"So be

it; at the eleventh (Footnote: This would be

something more than an hour before sunset. The Roman day, whatever its length,

was divided into twelve hours. An hour in July would be, therefore, rather more

than sixty minutes.) hour I shall expect you."

A NEW ALLY

[42] "LATERANUS," said the Prætorian to his

friend, as they sat together after dinner, "did you notice the face of the

girl who was taking leave of our friend Fannius when we first espied him this

afternoon?"

"Yes, indeed, I

did," said the Consul elect; "it was a face that no one could help

noticing, and having once seen, could hardly forget."

"That is exactly as it

struck me; and I am sure that I have seen it before; and not so very long ago. But where? That puzzles me. Now and then I seem to have it,

but then it slips away again. Depend upon it, she is no ordinary woman. Very

beautiful she is, but somehow it is not the beauty, but the resolute strength

of her face that impresses one. And what did the man mean when he said that she

'thought about other things.' I have a sort of presentiment that she will help

us."

"You surprise

me," said Lateranus. "And yet—"

At this point he was

interrupted by the appearance of a slave who announced the arrival of the

expected guest.

[43] For some time the

conversation was general, Fannius taking his part in it with an ease and

readiness that surprised Lateranus, and even exceeded the expectations of his

old friend and landlord. It naturally turned, before very long, on the details

of life in the "gladiators' school." Fannius explained that he had

only a few more weeks to serve. After the next show, which was to take place in

September, he would be entitled to his discharge. He had been extraordinarily

successful in his profession, and the "golden youth" of

"Very good,"

replied Subrius. "The gods forbid that there should arise any need for my

services, but, if there should, you may be sure that I will not fail in my duty

as your friend."

"Many thanks,

sir," said Fannius, producing some papers from his pocket. "These are

acknowledgments from Cassius, the banker, of deposits which I have made with

him. Thras has charge of what I possess in coin, and will have instructions to

hand it over to you. And here is the paper of directions. Will you please to

read it? Is it quite plain?"

"Perfectly so,"

answered the Tribune. "But there is one question which I must take the

liberty of asking. You mention a certain Epicharis. Who is she? Where am I to

look for her?"

"She lives with her

aunt by marriage. Galla is the aunt's name, and she cultivates a little farm on

this side of Gabii. Any one there will direct you to it. She is the young woman

whom you saw speaking to me this afternoon."

"I guessed as

much," said Subrius, "and I have been

puzzling myself ever since trying to make sure whether I had seen her

before."

"That you might very

easily have done," replied [45] the gladiator. "She was much with the

Empress Octavia. Indeed, she was her foster-sister."

"Ah!" cried Subrius;

"that accounts for it. Now I remember all about it. I was on guard in the

Palace with my cohort on the day when the Empress Octavia was sent away to

"Yes, yes," said

Fannius, "you are right; she was with the Empress then; indeed, she

remained with her till her death. Oh! sir, it is a

piteous story that she tells. But perhaps I had better not speak about those

things."

"Speak on without

fear," replied the Prætorian. "I am one of the Emperor's soldiers,

and my friend here has received the honour of the Consulship from him; but we

have not therefore ceased to be Romans and men. Whatever you may tell us will be safely kept—"

The speaker paused, and

then added in a deliberate and meaning tone, "As long as it may be necessary

to keep it."

[46] The gladiator cast a

quick glance at him, and resumed. "Well, Epicharis was with her mistress

from the unlucky day when she was carried across the threshold of her husband's

house, (Footnote: Octavia was married to Nero in

53 A.D.) down to the very end. They were both children then, only twelve years

of age, and the poor Empress was really never anything else. But Epicharis soon

learnt to be a woman. From almost the first she had to protect her mistress.

Nero never loved his wife. Epicharis says she was too good for him, or, indeed,

for almost any man; that she ought to have had a philosopher or a priest for

her husband."

"I don't know that

philosophers or priests are better than other men," interrupted Subrius;

"but go on."

"Well, as I said, Nero

never loved her, but, for a time, he was decently civil to her. Then her

brother died, was—"

"Was poisoned, you

were going to say," said Subrius. "That is no secret. Everybody in

"Epicharis tells me

that the Empress never shed a tear. She had learnt to hide her feelings, as

children do when they are afraid of their elders. Then the Empress-mother came

by her end. As long as she was alive the wife's lot was tolerable. But after

that—oh! gentlemen, I could not bring myself to say a

tenth of the things that I have heard. They [47] are too dreadful. The poorest,

unhappiest woman had not so much to bear. I used to think when I was a boy that

the fine ladies who lived in great houses, and were dressed in gay silks, and

rode about in soft cushioned carriages, must be happy; but now that I have had

a look at what goes on behind palace walls, I don't think so any more. Then

came what you saw, sir, on the palace stairs. It is no wonder that the poor

Empress should look miserable after what she had gone through in those days,

seeing, for instance, her slave-girls tortured in the hope that something might

be wrung out of them against her. Epicharis herself they did not touch; she was

free, you see; but they threatened her. I warrant they got nothing by that. She

has a tongue, and knows how to use it. She let that monster Tigellinus know

what she thought of him, and his master too. She has

told me that she saw the Emperor wince once and again at the answers she made.

Then Octavia was sent away. It was a great relief to go; to be away from the

dreadful palace. She ran about the gardens and grounds of the villa,—it was to

Burrus' house near Misenum, you will remember, she was sent,—and made friends

with the little children; in fact, she was happier than she had ever been in

her life before. 'Now that I am out of their way, and do not interfere with

their plans, they will let me alone, and, perhaps, forget me.' This is what she

would say to Epicharis. 'I am sure that I don't want to marry [48] again, and

you had better follow my example, dear sister,'—she would often call Epicharis

'sister.' 'Husbands seem very strange creatures, so difficult to please, and

always imagining such strange things about one. You and I will live together

for the rest of our lives, and take care of the poor people. It really is much

nicer than

"No," said

Subrius; "he had wronged her far too deeply ever to be able to forgive."

"Just so,"

observed Lateranus; "and if he could have done it there was Poppæa, and a

woman never spares a rival, especially a rival who is better than herself.

Besides he dared not let his divorced wife live. You see she was the daughter of

Claudius, and her husband, supposing that she had married again, would have

been dangerously near the throne. And then the people loved her; that was even

more against her than anything else."

[49] "That is exactly

what Epicharis thought, so she has often told me. After a few days came news

that there had been great disturbances in Rome; that the people had stood up

like one man in the Circus, and shouted out to the Emperor, 'Give us back

Octavia!' and that Nero had annulled the divorce. Some of the poor woman's

attendants were in high spirits. You see they did not like

"Ah!" said

Subrius, "a lucky fever-fit saved me from being sent on that errand. My

cohort had been detailed for the duty; the sealed orders, which I [50] was not

to open till I reached the villa, had been handed to me; and then at the last

moment, when I was racking my brain, thinking how I could possibly get off,

there fortunately came this attack. I never had

thought before that I should be positively glad to have the ague."

"Well, sir, from what

Epicharis has told me, you were spared one of the most pitiable sights that

human eyes ever saw. Octavia was sitting in the garden when the Tribune came up

and saluted her. She gave him her hand to kiss. 'I suppose you have come to

take me back to

"Well,"

interrupted the Prætorian, "it must have been something to make that brute

Severus—for he was on duty in my place, I remember—shed a tear."

" ' Madam,' said the Tribune, 'you

mistake. We have come on another business. You are not to return to

"They told us in

[52] "Epicharis tells

a very different story. When the Empress saw the soldiers, she said in a very

cheerful voice—you see she had not the least idea that her life was in danger,

and Epicharis had never had the heart to tell her,—'Well, gentlemen, what is

you business this time? Where are you going to take me now? I must confess that

I liked Misenum better than this.' 'Madam,' said the Centurion in command 'with

your permission I will explain my business when I get to the house, if you will

be pleased to return thither.' He said this, you see, to gain time. On the way

back he contrived to whisper into Epicharis' ear what his errand really was.

She knew it already well enough, you may be sure. 'You must break it to her,'

he said. That was an awful thing for the poor girl to do. She is not of the

tearful sort,—you know; but she sobbed and wept as if her heart would break,

when she told me the story. The Empress went up to her bed-chamber to make some

little change in her dress. As she was sitting before the glass, Epicharis came

and put her arms round her neck. The Empress turned round a little surprised.

You see she would often kiss and embrace her foster-sister, but it was always

she that began the caress and the other that returned it. 'What ails you,

darling?' she said, for Epicharis' eyes were full of tears. 'O dearest lady, I

cannot help crying when I think that we shall have to part!' 'Surely,' said the

Empress, 'they are not going to be so cruel as to take you [53] away from me. I

will write to the Emperor about it; he can't refuse me this little favour.' 'O

lady,' said Epicharis, who was in despair what to say,—how could one break a

thing of this sort?—he will grant you nothing, not even another day.' 'What do

you mean?' said Octavia, for she did not yet understand. 'O lady,' she cried,

'these soldiers are come—' and she put into her look the meaning that she could

not put into words. 'What!' cried the poor woman, her voice rising into a

shrill scream, 'do you mean that they are come to kill me?' and she started up

from her chair. Epicharis has told me that the sight of her face, ghastly pale,

with the eyes wide open with fear, haunts her night and day. 'Oh, I cannot die!

I cannot die!' she cried out. 'I am so young. Can't you hide me somewhere?' 'O

dearest lady!' said Epicharis, 'I would die to save you. But there is no way.

Only we can die together.' Then she took out of her robe two poniards, which

she always carried about in case they should be wanted in this way. 'Let me

show you. Strike just as you see me strike. After all it hurts very little, and

it will all be over in a moment.' 'No, no, no!' screamed the unhappy lady,

'take the dreadful things away. I cannot bear to look at them. I will go and

beg the soldiers to have mercy.' And she flew out of the room to where the

Centurion was standing with his men in the hall. She threw herself at the man's

feet—it was a most pitiable thing to see, Epicharis said when she told me [54]

the story—and begged for mercy. Poor thing, she clung to life, though the gods

know she had had very little to make her love it. The Centurion was unmoved,—as

for some of the common soldiers, they were half disposed to rebel,—and said

nothing but, 'Madam, I have my orders.' 'But the Emperor must have forgotten,'

she cried out; 'I am not Empress now, I am only a poor widow, and almost his

sister.' Then again, 'Oh, why does Agrippina let him do it?' seeming to forget

in her terror that Agrippina was dead. After this had gone on for some time,

the officer said to one of his men, 'Bind her, and put a gag in her mouth.'

Epicharis saw one or two of the men put their hands to their swords when they

heard the order given. But it was useless to think of resisting or disobeying.

They bound her hand and foot, and gagged her, and then carried her into the

house. They had brought a slave with them who knew some thing about surgery.

This man opened the great artery in each arm, but somehow the blood did not

flow. 'It is fairly frozen with fear,' Epicharis heard him say to the

Centurion. Then the two whispered together, and after a while the men carried

the poor woman into the bath-room. Epicharis was not allowed to go with her;

but she heard that she was suffocated with the hot steam, and that, as far as

any one knew, she never came to herself again. That, anyhow, is something to be

thankful for."

"They told a story in

"No," replied

Fannius; "she never knew what became of the body. She was never allowed to

see it; it was burnt that night, she was told."

"And so this is the

true story of Octavia," said Subrius after a pause. "You remember,

Lateranus, there was a great thanksgiving for the Emperor's deliverance from

dangerous enemies, and the enemy was this poor girl. Why don't the gods, if

they indeed exist (which I sometimes doubt), rain down their thunderbolts upon

those who mock them with these blasphemous pretences?"

"Verily," cried

Lateranus, "if they had been so minded

The gladiator looked with a

continually increasing astonishment on the two men who used language of such

unaccustomed freedom. Subrius thought it time to make another step in advance.

"As you have taken us

into your confidence," he said, "about the contents of your will, you

will not mind my asking you a question about these matters."

"Certainly not,"

answered the man. "You need not be afraid of offending me."

"If things go well

with you, as there is every hope [56] of their doing, and you get your

discharge all right, what do you look forward to?"

The gladiator shifted his

position two or three times uneasily, and made what seemed an attempt to speak,

but did not succeed in uttering a word.

"If Epicharis does not

become your legatee, as I sincerely hope she may not, is she to have no

interest in your money?"

"Ah, sir, she will

make no promises, or rather, she talks so wildly that she might as well say nothing

all."

"What do you

mean?"

"I may trust you,

gentlemen, for I am putting her life as well as my own in your hands?"

"Speak on boldly.

Surely we have both of us said enough this evening to bring our necks into

danger, if you chose to inform against us. We are all sailing in the same

ship."

"It is true. I ought

not to have doubted. Well, what she says to me is this, 'Avenge my dear

mistress on those who murdered her, and then ask me what you please.' She won't

hear of anything else. I have asked her what I could do, a simple gladiator,

who has not even the power to go hither or thither as he pleases. She has only

one answer, 'Avenge Octavia!' "

"It is not so hopeless as you think. There many who hold that Octavia

should be avenged, aye, and others besides Octavia. We are biding our [57]

time, and there are many things that seem to show that it is not far off. You

will be with us then, Fannius?"

"Certainly," said

the gladiator. "I want to hear nothing more; the fewer names I know, the

better, for then I cannot possibly betray them. Only give me the word, and I

follow. But how about Epicharis?" he went on; "is she to hear

anything?"

"I don't like letting

women into a secret," said Lateranus.

"Nor I," said

Subrius, "as a rule; but if there is any truth in faces, this particular

woman will keep a secret and hold to a purpose better than most of us. Shall we

leave it to Fannius' discretion?"

To this Lateranus agreed.

After some more

conversation the gladiator rose to take his leave. A minute or so afterwards he

returned to the room. "Gentlemen," he said, "there is a great

fire to be seen from a window in the passage, and from what I can see it must

be in the Circus, or, anyhow, very near it."

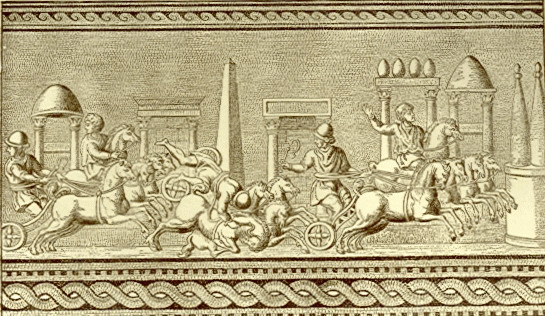

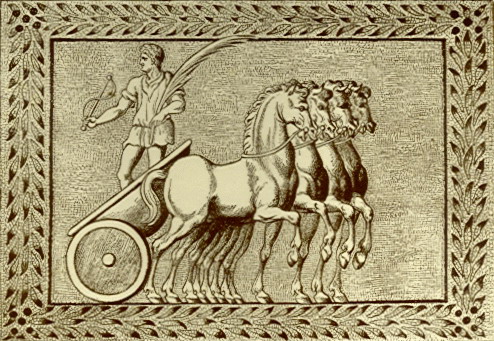

A GREAT FIRE

[58] THE two friends hurried to the window.

At the very moment of their reaching it a great flame shot up into the air. It

was easy to distinguish by its light the outline of the Circus, the white

polished marble of which shone like gold with the reflection of the blaze.

"It can scarcely be

the Circus itself that is on fire," cried Subrius; "the light seems

to fall upon it from without. But the place must be dangerously near to it.

Hurry back, Fannius, as quick as you can. We shall come after you as soon as

possible, and shall look out for you at the Southeastern Gate."

The gladiator ran off at

the top of his speed, and the two friends lost no time in making themselves

ready to follow him. Discarding the dress of ceremony in which they had sat

down to dinner, for indeed, the folds of the toga were not a little

encumbering, they both equipped themselves in something like the costume which

they would have assumed for a hunting expedition, an outer and an inner tunic,

drawers reaching to the knee, leggings and boots. Lateranus was by far the

larger man of [59] the two; but one of his freedmen was able to furnish the

Prætorian with what he wanted.

"Don't let us forget

the hunting-knives," said Lateranus; "we may easily want something

wherewith to defend ourselves, for a big fire draws to it all the villains in

the city."

By this time all

Arrived at the spot, the

friends found that the conflagration was even more extensive and formidable

than they had anticipated. The Circus was still untouched, but it was in

imminent danger. A shop where oil for the Circus lamps had been sold was

burning fiercely, and it was separated from the walls of the great building

only by a narrow passage. As for the shop itself, there was no hope of saving

it; the. flames had got such a mastery over it that

had the Roman appliances for extinguishing fire been ten [60] times more

effective than they were, they could hardly have made any impression upon them.

To keep the adjoining buildings wet with deluges of water was all that could be

done. A more effective expedient would have been, of course, to pull them down.

Subrius, who was a man of unusual energy and resource, actually proposed this

plan of action to the officer in command of the Watch, a body of men who

performed the functions of a fire-brigade. The suggestion was coldly received.

The officer had received, he said, no orders, and could not take upon himself

so much responsibility. And who was to compensate the owners, he asked. And

indeed, the time had hardly come for the application of so extreme a remedy. As

a matter of fact, it is always employed too late. Again and again enormous loss

might be prevented if the vigorous measures which have to be employed at the last

had been taken at the first. No one, indeed, could blame the Prefect of the

Watch for his unwillingness to take upon himself so serious a responsibility,

but the conduct of his subordinates was less excusable. They did nothing, or

next to nothing, in checking the fire. More than this, they refused, and even

repulsed with rudeness, the offers of assistance made by the bystanders. A cordon was formed to keep the spectators at a distance from

the burning houses; for by this time the buildings on either side had caught

fire. This would have been well enough, if it had been desired that the firemen

[61] should work unimpeded by the pressure of a curious mob; but, as far as

could be seen, they did nothing themselves, and suffered nothing to be done by

others.

Subrius and Lateranus,

though they were persons of too much distinction to be exposed to insult, found

themselves unable to do any good. They were chafing under their forced

inaction, when they were accosted by the gladiator.

"Come,

gentlemen," he said; "let us see what can be done. The fire has

broken out in two fresh places, and this time inside the Circus."

"In two places!"

cried Subrius in astonishment. "That is an extraordinary piece of bad

luck. Has the wind carried the flames there?"

"Hardly, sir,"

replied the man, "for the night, you see, is fairly still, and both

places, too, are at the other end of the building."

"It seems that there

is foul play somewhere," said Lateranus. "But come, we seem to be of

no use here."

The three started at full speed

for the scene of the new disaster, Fannius leading the way. One of the fires,

which had broken out in the quarters of the gladiators, had been extinguished

by the united exertions of the corps. The other was spreading in an alarming

way, all the more alarming because it threatened that quarter of the building

in which the wild beasts were kept. The keeper of the Circus, who had, within

the building, an authority independ- [62] ent of the

Prefect of the Watch, exerted himself to the utmost in checking the progress of

the flames, and was zealously seconded by his subordinates; but the buildings

to be saved were unluckily of wood. The chambers and storehouses underneath the

tiers of seats were of this material, and were besides, in many cases, filled

with combustible substances. In a few minutes it became evident that the

quarters of the beasts could not be saved. The creatures seemed themselves to

have become conscious of the danger that threatened them, and the general

confusion and alarm were heightened by the uproar which they made. The shrill

trumpeting of the elephants and the deep roaring of the tigers and lions, with

the various cries of the mixed multitude of smaller creatures, every sound

being accentuated by an unmistakable note of fear, combined to make a din that

was absolutely appalling. The situation, it will be readily understood, was

perplexing in the extreme. The collection was of immense value, and how could

it be removed? For a few of the animals that had recently arrived the movable

cages in which they had been brought to the Circus were still available, for,

as it happened, they had not yet been taken away. Others had of necessity to be

killed; this seemed better than leaving them to perish in the flames, for they

could not be removed, and it was out of the question to let them loose. This

was done, to the immense grief of their keepers, for each beast [63] had its

own special attendant, a man who had been with it from its capture, and who was

commonly able to control its movements. The poor fellows loudly protested that

they would be responsible for the good behaviour of their charges, if they

could be permitted to take them from their cages; but the Circus authorities

could not venture to run the risk. An exception was made in the case of the

elephants. These were released, for they could be trusted with their keepers. A

part of the stock was saved—saved at least from the fire—by a happy thought

that struck one of the officials of the Circus. A part of the arena had been

made available for an exhibition of a kind that was always highly popular at

Throughout the night

Subrius and Lateranus exerted themselves to the utmost, and their efforts were

ably seconded by the gladiator. The day was beginning to break when, utterly

worn out by their labours, they returned to the house. Fannius was permitted by