Of the three phases, thus logically distinguishable, the first and the third correspond in the main with the receptive and active states or powers of the older psychologists. The second phase, being more difficult to isolate, was long overlooked ; or, at all events, its essential characteristics were not distinctly marked: it was either confounded with (1), which is its cause, or with (3), its effect. But perhaps the most important of all psychological distinctions is that which traverse both the old bipartite and the prevailing tripatite classification, viz., that between the subject, on the one hand, as acting and feeling, and the objects of this activity on the other. Such distinction lurks indeed under such terms as faculty, power consciousness, but they tend to keep it out of sight. With this distinction clearly before us—instead of crediting the subject with an indefinite number of faculties or capacities, we must seek to explain not only reproduction, association, agreement difference, &c., but all varieties of thinking and acting by the laws pertaining to ideas or presentations, leaving to the subject only the one power of variously distributing that attention upon which the intensity of a presentation in part depends. Of this single subjective activity what we call activity in the narrower sense (as, e.g., purpose movement and intellection) is but a special case, although a very important one.

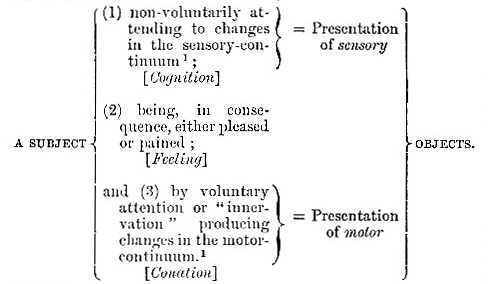

According to this view, then, presentations, attention, feeling, are not to be regarded as three co-ordinate genera, each a distinguishable "state of mind or consciousness," i.e., as being alike included under this one supreme category. There is, as Berkeley long ago urged, no resemblance between activity and an idea; nor is it easy to see anything common to pure feeling and an idea, unless it be that both possess intensity. Classification seems, in fact to be here out of place. Instead, therefore, of the one summum genus, state of mind or consciousness, with its three co-ordinate subdivisions—cognition, emotion, conation—our analysis seems to lead us to recognize three distinct and irreducible facts—attention, feeling, and objects or presentation—as together, in a certain connexion, constituting one concrete state of mind or psychosis. Of such concrete states of mind we may then say there are two forms, more or less distinct, corresponding to the two ways in which attention may be determined and the two classes of objects attended to in each, viz., (1) the sensory or receptive state, when attention in non-voluntarily determined i.e., where feeling follows the act of attention ; and (2) the motor or active state, where feeling precedes the act of attention, which is thus determined voluntarily.

To say that feeling and attention are not presentations will seem to many an extravagant paradox. If all knowledge consists of presentations, it will be said, how come we to know anything of feeling and attention if they are not presented? We know of them indirectly though their effects, not directly in themselves. This is, perhaps, but a more concrete statement of what philosophers have very widely acknowledge in a more abstract form since the days of Kant [Footnote 44-2] —the impossibility of the subjective qua subjective being presented. It is in the main clearly put in the following passage from Hamilton, who, however, has not had the strength of his convictions in all cases :—"The peculiarity of feeling, therefore, is that there is nothing but what is subjectively subjective ; there is no object different from self,—no objectification of any mode of self. We are, indeed, able to constitute our states of pain and pleasure into objects of reflexion, but, in so far as they are objects of reflexion, they are not feeling but only reflex cognitions of feelings." [Footnote 44-3] But this last sentence is not, perhaps, altogether satisfactory. The meaning seems to be that feeling "can only be studied through its reminiscence," which is what Hamilton has said studied through its reminiscence," which is what Hamilton has said elsewhere of the "phaenomena of consciousness" generally. But this is a position hard to reconcile with the other, viz., that feeling and cognition are generally distinct. How can that which was not originally a cognition become such by being reproduced? The statements that feeling is "subjectively subjective," that in it "there is no object different from self," are surely tantamount to saying that it is not presented ; and what is not presented cannot, of course, be re-presented. Instead, therefore, of the position that feeling and attention are known by being made objects of reflexion, it would seem we can only maintain that we know of them by their effects, by the changes, i.e., which they produce in the character all succession of our presentations. [Footnote 44-4] We ought also to bear in mind that the effects of attention and feeling cannot be known without attention and feeling: to whatever stage we advance, therefore, we have always in any given "state of mind" attention and feeling on the one side, and on the other a presentation of objects. Attention and feeling seem thus to be ever present, and not to admit of the continuous differentiation into parts which gives to presentations a certain individuality, and makes their association and reproduction possible.

Footnotes

[44-1] (i.e. footnote 1 located in table above) To cover more complex cases, we might here add the words" or trains of ideas."

[44-2] Compare "Gefühle der Lust and Unlust und der Wille... die gar nicht Erkenntnisse sind" (Kritik der reinen Vernunft, Hartenstein’s ed., p. 76).

[44-3] Lectures on Metaphysics, ii. p. 432.

[44-4] But, while we cannot say that we know what attention and feeling are, inasmuch as they are not presented, neither can we with any propriety maintain that we are ignorant of them, inasmuch as they are by their very nature unpresentable. As Ferrier contends, "we can be ignorant only of what can possibly be known; in other words, there can be ignorance only of that of which there can be knowledge" (Institutes of Metaphysics, § II., Agnoiology, prop. iii. sq.).The antithesis between the objective ad the subjective factors in presentation is wider than that between knowledge and ignorance, which is an antithesis pertaining to the objective side alone.

Read the rest of this article:

Psychology - Table of Contents