1902 Encyclopedia > Architecture > Ancient Egyptian Architecture: Tombs

Ancient Egyptian Architecture (cont.)

Tombs

The great reverence paid by the Egyptians to the bodies of their ancestors, and their careful preservation of them by embalmment, necessitated a great number and vast extent of tombs. Some of these, erected long after the building of pyramids had ceased, are built up above ground; others are caves cut in the side of rocks; others are passages tunnelled under the ground to the great extent.

The tombs above the ground have been most part destroyed. But some very interesting ones are found near the Great Pyramid. They are of well-squared stones, in the form of truncated pyramids; the tops are level, and they show no appearance of anything having been built above them. But there must have been a covering of some kind, as pits, leading to sepulchral chambers beneath, are cut down directly from the surface level.

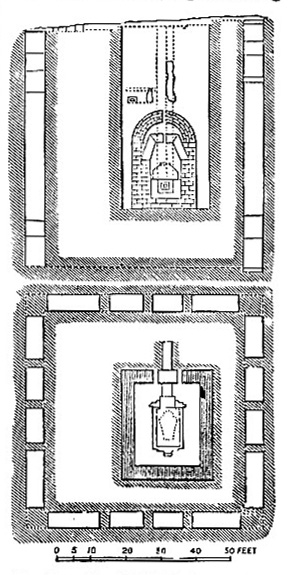

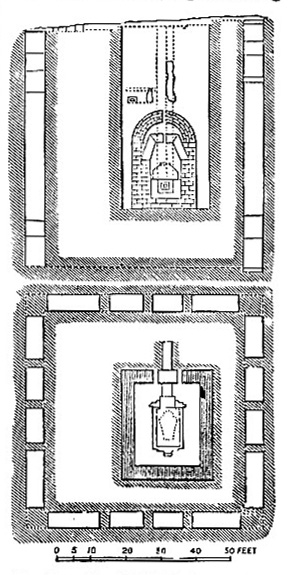

Fig. 21 -- Campbell's Tomb; section looking west.

From Vyse.

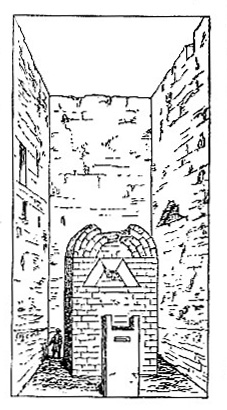

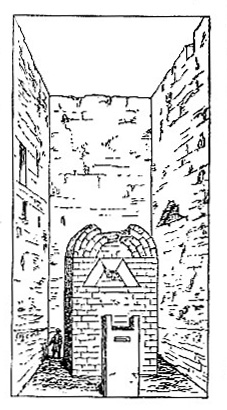

Fig. 22 -- Building in Campbell's Tomb.

From Vyse.

The most curious tomb at Ghizeh [Giza] is known as Campbell’s, of the supposed date of about 660 B.C. it is an open excavation, 53 feet 6 inches deep, 30 feet by 26 feet 3 inches on plan with niches, &c., leading out of it. in these were found four sarcophagi, one of which, of basalt, is in British Museum. This excavation is supposed, from some indication left of a springing stone, to have been covered by an arch. If so, this would be the oldest known stone arch of a large size. In fact, it is difficult to imagine any other way in which this large excavation could have been covered. But the special object actually found was a tomb built up in the centre of excavation, a good masonry, covered by three stones as struts, over which was a perfectly formed voussoired arch. This arch was destroyed not long ago by Egyptian Government, in order to build a mill. Outside the whole excavation was deep trench 5 feet 4 inches wide, and 73 feet deep, from which branch out a number of chambers. The excavation was probably as we have already described.

Even more interesting are the tombs at Beni Hassan and Thebes. There is a little attempt at architectural decoration in these, except the facades and some columns cut in the rock inside; but they are filled with most interesting painting, representing even the minutest incident of private life. A model of one was exhibited in London by Belzoni; and there is a valuable series built up, and painted in facsmile in Vatican at Rome.

It appears that as soon as a king succeeded to the throne, the excavation of his tomb commenced, and proceeded year by year till his death. Canina has given plans and sections of several of royal tombs, extending from 250 to 400 feet direct into the solid rock.

Several of these tombs at Beni Hassan have external facades high up in the cliff, consisting each of two columns in antis, to which we have again to refer when treating of the origins of Grecian Doric. Others, as at Ghizeh and Sakkara, have their entrances level with or below the ground, and without external decoration; whilst others, as at Thebes, have their entrances high up in the face of the cliffs, and not only without ornament of any kind, but closed up as if for purposes of concealment.

But each, no matter of what size or description, had one or more chambers or corridors, in the floor of some one or other which was sunk a deep pit. Leading out of this pit, again, were other chambers, in one which was deposited the sarcophagus. When this was done the pit was filled up so as to render the concealment of the place of sepulture as complete as possible. One of the grandest at Thebes is that of a priest, otherwise unknown to fame, which comprises a series of halls, passages, and chambers, at various levels, branching off in one place three different ways. In all, it is 863 feet long, and the part actually excavated occupies an area of 23,000 feet.

Many of the paintings already alluded to are often simply executed in colour, but others are emphasised by being sculptured also in slight intaglio. These came into use, it would seem, about 14th century B.C., the earlier work being relief. The stone was usually prepared for painting by being covered with a very thin fine stucco. Even the fine granites were so covered sometimes, and the woodwork also. Imitations of costly woods, &c., are found even at this early.

Read the rest of this article:

Architecture - Table of Contents

|