The Horror Of Glamis

For centuries, Glamis Castle has had a reputation as a place of strange and awful happenings - events that strike terror at the hearts of all who experience them.

Glamis Castle stands in the great vale of Strathmore in Tayside, Scotland. For centuries, the vast fortified house with its battlements and pointed towers - looking very much like the setting for a fairy tale - has been the home of the Earls of Strathmore, whose family secret is reputedly hidden within the very walls of Glamis, famous as one of the most haunted houses on earth.

That there was some form of unpleasantness within the castle's walls is an undoubted historical fact. And that the castle is today the centre of a triangle formed by three biblically named villages - Jericho, Zoar, and Pandanaram - may indicate the terror felt by its minions; for, according to a Scottish National. Trust guidebook, the men who built and named them `had at least some knowledge of the Scriptures and regard for the wrath of God.' That wrath, claim locals, was called down on Glamis for the sins of the first dozen or so lairds. In recent times, however, there is little to suggest that life at the castle has been anything other than pleasant and peaceful, in contrast with what once came to be known as the `horror' of Glamis.

It is the obscure nature of the `horror' that makes accounts of it all the more terrifying. Indeed, no recent Earl has ever spoken of it to an outsider, except in enigmatic terms, and no woman has ever been let in on the secret. It is passed on only to the Strathmore heir on his 21 st birthday.

The historical record of horror at Glamis Castle goes back to 1034, when King Malcolm 11 was cut down by a gang of rebellious subjects armed with claymores, the large broadswords peculiar to Scotland. It was said that every drop of Malcolm's blood seeped from his body into the floorboards, causing a stain that is still pointed out today, in what is called King Malcolm's Room. That the stain was made by Malcolm's blood is disputable, however, for records seem to show that the flooring has since been replaced. Nevertheless, Malcolm's killers added to the death toll of Glamis by trying to escape across a frozen loch: but the ice cracked and they were drowned.

The Lyon family inherited Glamis from King Robert 11, who gave it to his son-in-law, Sir John Lyon, in 1372. Until then, the Lyon family home had been at Forteviot, where a great chalice, the family 'luck', was kept. Tradition held that if the chalice were removed from Forteviot House, a curse would fall on the family. Despite this, Sir John took the cup with him to Glamis. The curse, though, seems to have had a time lapse: Sir John was indeed killed in a duel, but this did not occur until 1383, and the family misfortunes are usually dated from this time.

The 'poisoned' chalice may well have also influenced events 150 years later when James V had Janet Douglas, Lady Glamis, burned at the stake in Edinburgh on a charge of witchcraft. The castle reverted to the Crown; but after the falsity of the charge was proved, Glamis was restored to her son. The spectre of Lady Glamis - the 'Grey Lady' as she is known - is said regularly to walk the long corridors even today.

It was Patrick, the Third Earl of Strathmore, who made the idea of a Glamis 'curse' widespread in the late 17th century: indeed, to many people he seemed the very embodiment of it. A notorious rake and gambler, he was known in both London and Edinburgh, as well as throughout his home territory, for his drunken debauchery. Facts covering his career and his character are festooned with folklore, but he must have been something of an enigma; for despite his wild ways, he was philanthropic towards his tenants at least. The Glamis Book of Records, for instance, details his plans for building a group of lodges on the estate for the use of retired workers. Now known as Kirkwynd Cottages, they were given to the Scottish National Trust by the 16th Earl of Strathmore in 1957.

Two principal stories endure about Patrick. The first is that he was the father of a deformed child who was kept hidden somewhere in the castle, out of sight of prying eyes. The second is that he played cards with the Devil for his soul -and lost.

The first story is fed by a picture of the Third Earl. It shows Patrick seated, wearing a classical bronze breastplate, and pointing with his left hand towards a distant, romanticised vista of Glamis. Standing at his left knee is a small, strange-looking, green-clad child; to the child's left is an upright young man in scarlet doublet and hose. The three main figures are placed centrally, but two greyhounds in the picture are shown staring steadfastly at a figure, positioned at the Earl's right elbow. Like the Earl, this figure wears a classical breastplate, apparently shaped to the muscles of the torso - but if it is a human torso, it is definitely deformed. The left arm is also rather strangely foreshortened. Did the artist paint from life - and if so, does the picture show the real 'horror' of Glamis?

The second story goes like this. Patrick and his friend the Earl of Crawford were playing cards together one Saturday night when a servant reminded them that the Sabbath was approaching. Patrick replied that he would play, Sabbath or no Sabbath, and that the Devil himself might join them for a hand if he so wished. At midnight, accompanied by a roll of thunder, the Devil appeared and told the card-playing Earls that they had forfeited their souls and were therefore doomed to play cards in that room until Judgement Day.

Another story tells - with curious precision - of a grey-bearded man, shackled and left to starve in 1486. And a later one, probably also dating from before Patrick's time, is gruesome in the extreme. A party of Ogilvies from a neighbouring district came to Glamis and begged protection from their enemies, the Lindsays, who were pursuing them. The Earl of Strathmore led them into a chamber, deep in the castle, and left them there to starve. Unlike the unfortunate grey-bearded man, however, they had each other to eat and began to turn cannibal - some, according to legend, even gnawing the flesh from their own arms.

One or other of these tales may account for a skeletally thin spectre, known as Jack the Runner; and the ghost of a black pageboy, also seen in the castle, seems to date from the 17th or 18th century, when young slaves were imported from the West Indies. A white lady is also said to haunt the castle clock tower, while the grey-bearded man of 1486 appeared, at least once, to two guests simultaneously, one of whom was the wife of the Archbishop of York at the turn of the 20th century. She told how, during her stay at the castle, one of the guests came down to breakfast and mentioned casually that she had been awakened by the banging and hammering of carpenters. A brief silence followed her remarks, and then Lord Strathmore spoke, assuring her that there were no workmen in the castle. According to another story, as a young girl, Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother (daughter of the 14th Earl, Claude George Bowes-Lyon), once had to move out of the Blue Room because her sleep was being disturbed by rapping's, thumps, and footsteps.

Fascinating as all these run-of-the-mill ghosts and their distinguished observers are, however, it is the 'horror' that remains the great mystery of Glamis. All the principal rumours - cannibal Ogilvies notwithstanding - involve a deformed child, born to the family and kept in a secret chamber, who lived, according to 19th-century versions of the story, to a very old age. In view of the portrait openly displayed at Glamis, and always supposing that it is the mysterious child who is actually portrayed, subsequent secrecy seems rather pointless. If Patrick himself was prepared to have his 'secret' portrayed in oils, then why should successors have discouraged open discussion of the matter?

Despite such secrecy, at the turn of the 19th century, stories were still flying thick and fast. Claude Bowes-Lyon, the 13th Earl who died in 1904 in his 80th year, seems to have been positively obsessed by the 'horror', and it is around him that most of the 19th-century stories revolved. It was he, for instance, who told an inquisitive friend: 'If you could guess the nature of the secret, you would go down on your knees and thank God it were not yours.' Claude, too, it was who paid the passage of a workman and his family to Australia, after the workman had inadvertently stumbled upon a secret room at Glamis and been overcome with horror. Claude questioned him, swore the man to secrecy, and bundled him off to the colonies shortly afterwards.

In the 1920s, a party of young people staying at Glamis decided to track down the secret chamber by hanging a piece of linen out of every window they could find. When they finished, they saw there were several windows that they had not been able to locate from the inside. When the 14th Earl learned what they had done, he flew into an uncharacteristic fury. Unlike his forbears, however, he broke the embargo on the secret by telling it to his estate factor, Gavin Ralston, who subsequently refused to stay overnight at the castle again.

When the 14th Earl's daughter-in-law, the next Lady Strathmore, asked Ralston the secret, Ralston is said to have replied: 'It is lucky that you do not know and can never know it, for if you did, you would not be a happy woman.' It remains to be seen whether further light will ever be shed on the 'horror' of Glamis.

When lemmings, above, make their suicide leaps into the sea, they are responding to an instinct that in many ways is equivalent to human mass hysteria.

A strong corona around someone's foot, above, suggests good health. But notice the absence of the corona round the big toe. This is said to indicate that the subject is suffering from a headache. Massaging the toe, it is believed, will relieve this.

In general, a tense subject will produce a Kirlian image that is spikey in appearance. The more relaxed subject, however, will generate a softer, more regular corona, as below.

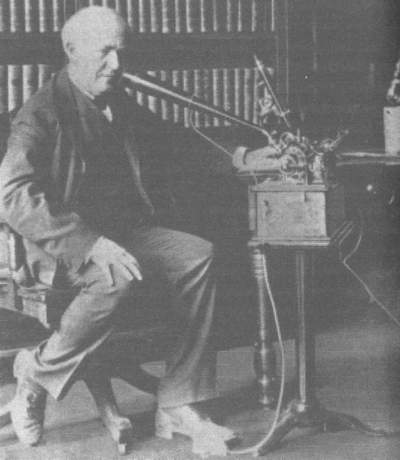

Thomas Alva Edison, above, invented the phonograph and the electric light bulb. In 1920, he also worked on a device that would, he believed, make possible a form of telepathic contact with the dead.