“Eight words the Wiccan Rede fulfill: An ye harm none, do what ye will.”

The Wican Rede has many ancestors: The earliest progenitors are probably Hippocrates, St. Augustine and the utterance of Jesus in the Lord’s Prayer. In the Hippocratic oath1 we find “Harm None;” or as it is sometimes translated “First do no harm.” In the Lord’s Prayer we have the first surviving ancient appearance of the word Θελημα2 as “thy will.” St. Augustine’s Sermon on St. John’s first epistle has the dictum “Love and do as ye will,”3 which is amazingly close to the phrases familiar to Thelemites.

Rabelais is commonly given credit for the initial formulation of the libertarian ethical maxim of thelema, being the sole rule of his fictional Abbey of Thelema: “fay çe que vouldras", variously translated from archaic French as “do what thou wilt,” “do what you please,” “do as you wish,” etc.4 Aleister Crowley expanded this idea5 into the modern religion of Thelema from its reference in his (or Aiwass’s6 depending on your point of view) holy text The Book of the Law,7 which has not only “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” but also “There is no law beyond Do what thou wilt.” This is often asserted to be the root of the Wican rede because Gardner borrowed so much from Crowley and The Book of the Law in his formulation of the rituals of Gardnerian Wica. Strangely on Gardner’s O.T.O. charter8 (signed by Crowley as Baphomet), Gardner miscopies this phrase as “Do what thou wilt shall be the law.” There is even “There is no law in Cocaigne save, Do that which seems good to you.” from the satire on Crowley’s Gnostic Mass in chapter 22 of James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen.9

As influential as all these sources may be, Gerald Gardner tells us quite clearly what the direct predecessor actually is:

[Witches] are inclined to the morality of the legendary Good King Pausol, "Do what you like so long as you harm no one". But they believe a certain law to be important, "You must not use magic for anything which will cause harm to anyone, and if, to prevent a greater wrong being done, you must discommode someone, you must do it only in a way which will abate the harm.

(Gerald B. Gardner. Witchcraft Today p. 127)10

King Pausol is not, in fact, legendary per se but the literary creation of the French novelist by Pierre Louÿs (1870-1925). Pierre Louÿs was the author of a number of popular turn-of-the-century fabulist erotic novels.11 King Pausol or Pausole in the French is from his novel Les Aventures du roi Pausole: Pausole (souverain paillard et débonnaire), (1901, reprinted in 1925 and numerous times since), or the Adventures of King Pausole (the bawdy and good natured sovereign).12

His style was heavily influenced by Rabelais which probably accounts for the inclusion of the maxims that eventually became the Wican rede, as The Adventures of King Pausole borrows many themes and ideas from Gargantua and Pantegruel; the variant of the thelemic dictum being but one among many.

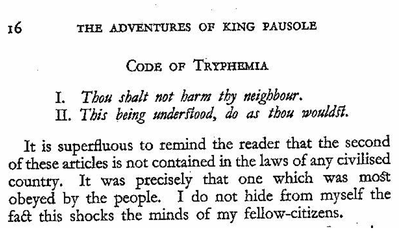

The novel takes place in fantastic kingdom of Tryphême, which has a simple code:

- — Ne nuis pas à ton voisin.

- — Ceci bien comprix, fais ce qu’il te plaît.

The Lumley has this as

- Thou shalt not harm thy neighbor

- This being understood, do as you wouldst.

but my poor French would indicate that in the second maxim “wouldest” is a bit weak for “plaît” and that it should probably be rendered something like: "This being understood, do as you please" or ". . . do as you like."

King Pausole applies this to his own life and has a variety of sexual relations with the 366 wives (one for each day with an extra for leap year) in his harem. The conflict in the story comes when a handsome young stranger arrives in the Kingdom and Pausole is faced with applying this principle to his beautiful daughter Aline when she and the handsome stranger fall in love. It all works out well in the end, of course, and the story is a comedy of erotic errors wherein old King Pausole must learn the hard way that the great Code of Tryphême has no value if it is not a true and universal law.

From the standpoint of Wican ethics it is clear that Gerald Gardner came across this story in his wide and varied exposure to culture, but it is far from clear exactly how this exposure happened. The text exists in a number of English translations:13 Pierre Louÿs: The Adventures of King Pausole. London : The Fortune Press, 1919. Collected works of Pierre Louÿs. New York : Liveright, Inc, 1932 (illust. H. G. Spanner). New York : Shakespeare House, 1951. New York: Liveright, 1952; though none of these are found in Gardner’s extant library list.

The book was also used as the basis of an Operetta: Les Aventures du roi Pausole (1930) by the Swiss composer Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) and the French librettist Arthur Willemetz (1887-1964).14 Gardner could certainly have seen a performance given the time frame. Several recent recordings are available, and the operetta is popular enough to rate modern performances.15 It is unclear how much French Gardner knew and the Bracelin/Shah biography doesn’t provide much help, but it was common for male Brits to have passable schoolboy fluency in the language, as witnessed by decent translations from that language by Gardner’s near contemporaries Crowley, Mathers, Wescott and Waite. Arthur Honegger was a lesser-known modern classical composer, associated with Schoenberg and Stravinsky (both of whom were also heavily influenced by pagan themes). Willemetz16 was a famous librettist of the French comedic theatre, especially the infamous Moulin Rogue and a popular biography by his daughter is available.

The book was also made into a film directed by Alexis Granowsky (released 1933) featuring the Swiss born Austrian actor Emil Jannings (1884-1950, Oscar for best actor in The Way of All Flesh, 1927 and The Last Command 1928):17 released variously under the titles Die Abenteuer des Königs Pausole (Germany), König Pausole (Austria), King Pausole (Great Britain) and The Merry Monarch (USA). Again it is quite possible if not probable that Gardner saw the British release of this very popular film. It is available on video18 though it may be silent; appearing on the cusp of the transition to talkies and featuring actors and a director who made their names in the silent era.

The only remaining question is who converted the code of Tryphême into the rhymed version that is so familiar to pagans worldwide. John J. Coughlin19 in his excellent study of the genesis of the Wican rede shows fairly convincingly that Doreen Valiente, with her talent for poetic composition, is the probable author. He also argues soundly that the Thompson/Porter assertion of a traditional family witchcraft source for the rede is not only unsupported but almost certainly untrue. The other possibility is that Gardner was following his formula for composing spells:

“Always in rhyme they are, there is something queer about rhyme. I have tried, and the same seem to lose their power if you miss the rhyme. Also in rhyme, the words seem to say themselves. You do not have to pause and think: “What comes next?” Doing this takes away much of your intent.”

(Gerald B. Gardner. 1957. The Weschcke Letters)20

For more on the history of the Wican rede the interested reader may refer to works cited in the notes to this essay, but particularly in following sources.

John J. Coughlin The Evolution of Wiccan Ethics. (2001). <http://www.waningmoon.com/ethics/>

John J. Coughlin, David R. Jones et al “The Wiccan Rede A Historical Journey (Essay).” (4 August through 6 August 2001). Usenet Newsgroup: Alt.Pagan. <http://groups.google.com/groups?hl=en&group=alt.pagan>

Justine Glass. Witchcraft the Sixth Sense. Los Angles: Wilshire, 1978.

Shea Thomas. The Wiccan Rede Project. (29 February 200). <http://pagan.drak.net/sheathomas/>.

Doreen Valiente. Witchcraft for Tomorrow. Blaine, WA: Phoenix Publishing, 1985.

Next part we continue with our series on Wican ethics with an examination of another of the influences on Wican ethics referred to by Gardner in his Witchcraft for Tomorrow, Ellen Wheeler Wilcox: Poet, Freethinker and Rosicrucian.

1 S. Thomas. The Doctor’s Rede. (2000). <http://pagan.drak.net/sheathomas/doctor.html>

2 It is interesting that though examples of declensions of the word Θελημα, exist throughout classical Greek the earliest extant example of this precise form (with one doubtful reading of Aristotle) is in the Koine Greek version of Jesus instruction on prayer commonly referred to as the Lord’s Prayer: N.T. Matthew 6 and Luke 11. For a comparison of the English and Greek see <http://members.aol.com/GrkOrthdx1/gcfrme20.htm>

3 David P. Steelman. Augustine Day by Day. (2001). <http://artsci.villanova.edu/dsteelman/augustine/days/0524.html>

4 Elaborated in Tim Maroney. And Brad McCormick Rabelais’ Abbey of Thélème (23 September 2001). <http://www.users.cloud9.net/~bradmcc/theleme.html>, for full texts of Rabelais Gangantua and Pantegruel: English <http://encyclopediaindex.com/b/ggpnt10.htm> and French <http://abu.cnam.fr/cgi-bin/donner_html?gargantua2>.

5 Crowley paid tribute to Rabelais’ prophetic contribution by including him as a Saint in his Gnostic Mass <http://www.otohq.org/oto/l15.html>.

6 One of the more humorous anecdotes in this regard is the one where a student once asked Crowley: “who was really the author of The Book of the Law.” To which Crowley is reported to have replied: “Of course I was.”

7 For the most accurate version now available and a linked view of the MS. <http://www.otohq.org/oto/l220.html>.

8 For a detailed view of this document, now in the possession of E.G.C. Bishop Tau Allen Greenfield, see <http://www.geraldgardner.com/index/charter.shtml>.

9 James Branch Cabell. Jurgen: a Comedy of Justice. New York: R.M. McBride & Company, 1922, c1919. <http://docsouth.unc.edu/cabell/menu.html>

10 Gerald B. Gardner. Witchcraft Today. London: Rider, 1954.

11 Synopses of several of his works <http://www.queerreads.com/page0229.htm>.

12 Louÿs, Pierre. Les Aventures Du Roi Pausole. Paris: Albin Michel, 1948.

13 Louÿs, Pierre. The Adventures of King Pausole. trans. Charles H. Lumley, illus. Beresford Egan. New York: William Godwin, 1933.

14 <http://www.france.diplomatie.fr/culture/france/musique/composit/honegger.html>.

15 <http://www.alsapresse.com/jdj/98/01/17/ST/page_1.html>.

16 <http://www.multimania.com/musicom/auteurs_auteurs_willemetz.html>.

17 <http://homepages.about.com/unofficialoscars/oscars/actors/jannings.html>.

18 <http://us.imdb.com/Title?0272729>.

19 Op cit. <http://www.waningmoon.com/ethics/rede.shtml>.

20 As quoted in Aidan Kelly’s Inventing Witchcraft pt. 4 p. 31