See Also @ Hermetic.com: The Temple of Solomon the King Part I · Part II · Part III · Part IV · Part V · Part VI · Part VII · Part VIII · Part IX

THE TEMPLE OF SOLOMON

THE KING

IV.

THE HERMIT

WITH the seventh stage in the Mystical Progress of Frater P. we arrive at a sudden and definite turning-point.

During the last two years he had grown strong in the Magic of the West. After having studied a host of mystical systems he had entered the Order of the Golden Dawn, and it had been a nursery to him. In it he had learnt to play with the elements and the elemental forces; but now having arrived at years of adolescence, he put away childish things, and stepped out into the world to teach himself what no school could teach him,—the Arcanum that pupil and master are one!

He had become a 6○ = 5□, and it now rested with him, and him alone, to climb yet another ridge of the Great Mountain and become a 7○ = 4□, an Exempt Adept in the Second Order, Master over the Ruach and King over the Seven Worlds.

By destroying those who had usurped control of the Order of the Golden

Dawn, he not only broke a link with the darkening past, but forged so might an

one with the gleaming future, that soon he was destined to weld it to the all

encircling chain of the Great Brotherhood.

All these great deeds did he do, as we shall see. he tamed the bulls with

ease,—the White and the Black. He ploughed the double field,—the East

and the West. He sowed the dragons’ teeth,—the Armies of Doubt; and among

them did he cast he stone of Zoroaster given to him by Medea, Queen of

Enchantments, so that immediately they turned their weapons one against the

other, and perished. And then lastly, on the mystic cup of Iacchus he lulled

to sleep the Dragon of the illusions of life, and taking down the Golden

Fleece accomplished the Great Work. Then once again did he set {44} sail, and

sped past Circe, through Scylla and Carybdis; beyond the singing sisters of

Sicily, back to the fair plains of Thessaly and the wooded slopes of Olympus.

And one day shall it come to pass that he will return to that far distant land

where hung that Fleece of Gold, the Fleece he brought to the Children of Men

so that they might weave from it a little garment of comfort; and there on

that Self-same Tree shall he hand himself, and others shall crucify him; so

that in that Winter which draweth nigh, he who is to come may find yet another

garment to cover the hideous nakedness of man, the Robe that hath no Seam.

And those who shall receive, though they cast lots for it, yet shall they not

rend it, for it is woven from the top throughout.

For unto you is paradise opened, the tree of life is planted, the time to

come is prepared, plenteousness is made ready, a city is bilded, the rest is

allowed, yea, perfect goodness and wisdom. The root of evil is sealed up from

you, weakness and the moth is hid from you, and corruption is fled unto hell

to be forgotten: sorrows are passed, and in the end is shewed the treasure of

immortality.1

Yea! the Treasure of Immortality. In his own words let us now describe

this sudden change.

{45}

In Mexico: even as I did receive it from him who is reincarnated in me: and

this work is to the best of my knowledge a synthesis of what the Gods have

given unto me, as far as is possible without violating my obligations unto the

Chiefs of the R. R. et A. C. Now did I deem it well that I should rest awhile

before resuming my labours in the Great Work, seeing that he, who sleepeth

never, shall fall by the wayside, and also remembering the twofold sign: the

Power of Horus: and the Power of Hoor-pa-Kraat.3

Now, the year being yet young, One D. A. came unto me, and spake.

And he spake not any more (as had been his wont) in guise of a skeptic and

indifferent man: but indeed with the very voice and power of a Great Guru, or

of one definitely sent from such a Brother of the Great White Lodge.

Yea! though he spake unto me words all of disapproval, did I give thanks

and grace to God that he had deemed my folly worthy to attract his wisdom.

And, after days, did my Guru not leave me in my state of humiliation, and,

as I may say, despair: but spake words of comfort saying: "Is it not written

that if thine Eye be single thy whole body shall be full of Light?" Adding:

"In thee is no power of mental concentration and control of thought: and

without this thou mayst achieve nothing."

Under his direction, therefore, I began to apply myself unto the practice

of Raja-yoga, at the same time avoiding all, even the smallest, consideration

of things occult, as also he bade me.

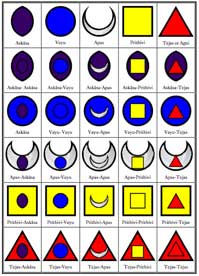

Thus, at the beginning, I did meditate twice daily, three mediations

morning and evening, upon such simple objects as—a white triangle; a red

cross; Isis; the simple Tatwas; a wand; and the like. I remained after some

three weeks for 59 ½ minutes at one time, wherein my thought wandered 25

times. Now I began also to consider more complex things: my little Rose

Cross;4 the {46} complex Tatwas; the Golden Dan Symbol, and so on. also I

began the exercise of the pendulum and other simple regular motions.

Wherefore to-day of Venus, the 22nd of February 1901, I being in the City of

Guadalajara, in the Hotel Cosmopolita, I do begin to set down all that I

accomplish in this work:

And may the Peace of God, which passeth all understanding, keep my heart

and mind through Christ Jesus our Lord.

We must now digress in order to five some account of the Eastern theories

of the Universe and the mind. Their study will clarify our view of Frater P’s

progress.

The reader is advised to study Chapter VII of Captain J. F. C. Fuller’s

"Star in the West" in connection with this exposition.

{47}

DIRECT experience is the key to Yoga; direct experience of that Soul (Âtman) or Essence (Purusha) which acting upon Energy (Prâna), and Substance (Âkâsa)

differentiates a plant from a stone, an animal from a plant, a man from an

animal, a man from a man, and man from God, yet which ultimately is the

underlying Equilibrium of all things; for as the Bhaga-vad-Gâta says:

"Equilibrium is called Yoga."

Chemically the various groups in the organic and inorganic worlds are

similar in structure and composition. One piece of limestone is very much

like another, and so also are the actual bodies of any two man, but not so

their minds. There-fore, should we wish to discover and understand that Power

which differentiates, and yet ultimately balances all appearances, which are

derived by the apparently unconscious object and received by the apparently

conscious subject, we must look for it in the workings of man’s brain.5 {48}

This is but a theory, but a theory worth working upon until a better be

derived from truer facts. Adopting it, the transfigured-realist gazes at it

with wonder and then casts Theory overboard, and loads his ship with Law;

postulates that every cause has its effect; and,. when his ship begins to

sink, refuses to jettison his wretched cargo, or even to man the pumps of

Doubt, because the final result is declared by his philosophy to be

unknowable.

If any one cause be unknowable, be it first or last, then all causes are

unknowable. The will to create is denied, the will to annihilate is denied,

and finally the will to act is denied. Propositions perhaps true to the

Master, but certainly not so to the disciple. Because Titian was a great

artist and Rodin is a great sculptor, that is no reason why we should abolish

art schools and set an embargo on clay.

If the will to act is but a mirage of the mind, then equally so is the will

to differentiate or select. If this be true, and the chain of Cause and

Effect is eternal, how is it then that Cause A produces effect B, and Cause B

effect C, and Cause A + B + C effect X. Where originates this power of

production? It is said there is no change, the medium remaining alike

throughout. Burt we say there is a change—a change of form,6 and not only

a change, but a distinct birth and a distinct death of form. What creates

this form? Sense perception. what will destroy this form, and reveal to us

that which lies behind it? {49} Presumably cessation of sense perception.

How can we prove our theory? By cutting away every perception, every thought-

form as it is born, until nothing thinkable is left, not even the thought of

the unknowable.

The man of science will often say "I do not know, I really do not know

where these bricks came form, or how they were made, or who made them; but

here they are; let us build a house and live in it." Now this indeed is a

very sensible view to take, and the result is we have some very fine houses

built by these excellent bricklayers; but strange to say, this is the

fatalist’s point of view, and a fatalistic science is indeed a cruel kind of

oxymoron. As a matter of fact he is nothing of the kind; for, when he has

exhausted his supply of bricks, he starts to look about for others, and when

others cannot be found, he takes one of the old ones and picking it to pieces

tries to discover of what it is made so that he may make more.

What is small-pox? Really, my friend, I do not know where it came from, or

what it is, or how it originated; when a man catches it he either dies or

recovers, please go away and don’t ask me ridiculous questions! Now this

indeed would not be considered a very sensible view to adopt. And why?

Simply because small-pox no longer happens to be believed in as a malignant

devil, but is, at least partially, known an understood. Similarly, when we

have gained as much knowledge of the First Cause as we have of small-pox, we

shall no longer believe in a Benevolent God or otherwise, but shall, at least

partially, know and understand Him as He is or is-not. "I can’t learn this!"

is the groan of a schoolboy and not the exclamation of a sage. No doctor who

is worth his salt will say: "I can’t tackle this disease"; he says: "I will

tackle {50} this disease." So also with the Unknowable, God, à priori, First

Cause, etc., etc., this metaphysical sickness can be cured. Not certainly in

the same manner as small-pox can be; for physicians have a scientific language

wherein to express their ideas and thoughts, whilst a mystic too often has

not; but by a series of exercises, or a system of symbolic teaching, which

will gradually lead the sufferer from the material to the spiritual, and not

leave him gazing and wondering at it, as he would at a star in the night.

A fourth dimensional being, outside a few mathematical symbols, would be

unable to explain to a third dimensional being a fourth dimensional world,

simply because he would be addressing him in a fourth dimensional language.

Likewise, in a less degree, would a doctor be unable to explain the theory of

inoculation to a savage, but it is quite conceivable that he might be able to

teach him how to vaccinate himself or another; which would be after all the

chief point gained.

Similarly the Yogi says: I have arrived at a state of Superconsciousness

(Samâdhi) and you, my friend, are not only blind, deaf and dumb, and a savage,

but the son of a pig into the bargain. You are totally immersed in Darkness

(Tamas); a child of ignorance (Avidyâ), and the offspring of illusion (Mâyâ);

as mad, insane and idiotic as those unfortunates you lock up in your asylums

to convince you, as one of you yourselves has very justly remarked, that you

are not all raving mad. For you consider not only one thing, which you insult

by calling God, but all things, to be real; and anything which has the

slightest odour of reality about it you pronounce an illusion. But, as my

brother the Magician has told you, "he {51} who denies anything asserts

something," now let me disclose to you this "Something," so hat you may find

behind the pairs of opposites what this something is in itself and not in its

appearance.

It has been pointed out in a past chapter how that in the West symbol has

been added to symbol, and how that in the East symbol has been subtracted from

symbol. How in the West the Magician has said: "As all came from God so must

all proceed to God," the motion being a forward one, and acceleration of the

one already existing. Now let us analyze what is meant by the worlds of the

yogi when he says: "As all came from god so must all return to God," the

motion being, as it will be at once seen, a backward one, a slowing down of

the one which already exists, until finally is reached that goal from which we

originally set out by a cessation of thinking, a weakening of the vibrations

of illusion until they cease to exist in Equilibrium.7 {52}

BEFORE we enter upon the theory and practice of Yoga, it is essential that the

reader should possess some slight knowledge of the Vedânta philosophy; and

though the following in no way pretends to be an exhaustive account of the

same, yet it is hoped that it will prove a sufficient guide to lead the seeker

from the Western realms of Magic and action to the Eastern lands of Yoga and

renunciation.

To begin with, the root-thought of all philosophy and religion, both

Eastern and Western, is that the universe is only an appearance, and not a

reality, or, as Deussen has it:

The entire external universe, with its infinite ramifications in space and

time, as also the involved and intricate sum of our inner perceptions, is all

merely the form under which the essential reality presents itself to a

consciousness such as ours, but is not the form in which it may subsist

outside of our consciousness and independent of it; that, in other words, the

sum total of external and internal experience always an only tells us how

things are constituted for us, and for our intellectual capacities, not how

they are in themselves and apart from intelligences such as ours.8

Here is the whole of the World’s philosophy in a hundred words; the undying

question which has perplexed the mind of man from the dim twilight of the

Vedas to the sweltering noon-tide of present-day Scepticism, what is the "Ding

an sich"; what is the αὐτὸ καθ αὑτό;

what is the Âtman?

That the thing which we perceive and experience is not {53} the "thing in

itself" is very certain, for it is only what "WE see." Yet nevertheless we

renounce this as being absurd, or not renouncing it, at least do not live up

to our assertion; for, we name that which is a reality to a child, and a

deceit or illusion to a man, an apparition or a shadow. Thus, little by

little, we beget a new reality upon the old reality, a new falsehood upon the

old falsehood, namely, that the thing we see is "an illusion" and is not "a

reality," seldom considering that the true difference between the one and the

other is but the difference of name. Then after a little do we begin to

believe in "the illusion" as firmly and concretely as we once believed in "the

reality," seldom considering that all belief is illusionary, and that

knowledge is only true as long as it remains unknown.9

Now Knowledge is identification, not with the inner or outer of a thing,

but with that which cannot be explained by either, and which is the essence of

the thing in itself,10 and which the Upanishads name the Âtman.

Identification with this Âtman (Emerson’s "Oversoul") is therefore the end of

Religion and Philosophy alike.

"Verily he who has seen, heard, comprehended and known the Âtman, by him is

this entire universe known."11 Because there is but one Âtman and not many

Âtmans. {54}

The first veil against which we must warn the aspirant is the entanglement

of language, of words and of names. The merest tyro will answer, "of course

you need not explain to me that, if I call a thing ‘A’ or ‘B,’ it makes no

difference to that thing in itself." And yet not only the tyro, but many of

the astutest philosophers have fallen into this snare, and not only once but

an hundred times; the reason being that they have not remained silent12 about

that which can only be "known" and not "believed in," and that which can never

be names without begetting a duality (an untruth), and consequently a whole

world of illusions. It is the crucifixion of every world-be Saviour, this

teaching of a truth under the symbol of a lie, this would-be explanation to

the multitude of the unexplainable, this passing off on the canaille the

strumpet of language (the Consciously Known) in the place of the Virgin of the

World (the Consciously Unknown).13

No philosophy has ever grasped this terrible limitation so firmly as the

Vedânta. "All experimental knowledge, the four Vedas and the whole series of

empirical science, as they are enumerated in Chândogya, 7. 1. 2-3, are ’nâma

eva,’ ’mere name.’"14 As the Rig Veda says, "they call him Indra, Mitra,

Varuna, Agni, and he is heavenly nobly-winged Garutmân. To what is one, sages

give many a title: they call it Agni, Tama, Mâtirisvan."15 {55}

Thus we find that "duality" in the East is synonymous with "a mere matter

of words,"16 and further, that, when anything is (or can be) describe by a

word or a name, the knowledge concerning it is Avidyâ, "ignorance."

No sooner are the eyes of a man opened17 than he sees "good and evil," and

becomes a prey to the illusions he has set out to conquer. He gets something

apart from himself, and whether it be Religion, Science, or Philosophy it

matters not; for in the vacuum which he thereby creates, between him and it,

burns the fever that he will never subdue until he has annihilated both.18

God, Immortality, Freedom, are appearances and not realities, they are Mâyâ

and not Âtman; Space, Time and Causality19 are appearances and not realities,

they also are Mâyâ and not Âtman. All that is not Âtman is Mâyâ, and Mâyâ is ignorance, and ignorance is sin.

Now the philosophical fall of the Âtman produces the Macrocosm and the

Microcosm, God and not-God—the Universe, or the power which asserts a

separateness, an individuality, {56} a self-consciousness—I am! This is

explained in Brihadâranyaka, 1. 4. 1. as follows:

"In the beginning the Âtman alone in the form of a man20 was this universe.

He gazed around; he saw nothing there but himself. Thereupon he cried out at

the beginning: ’It is I.’ Thence originated the name I. Therefore to-day,

when anyone is summoned, he answers first ’It is I’; and then only he names

the other name which he bears."21

This Consciousness of "I" is the second veil which man meets on his upward

journey, and, unless he avoid it and escape from its hidden meshes, which are

a thousandfold more dangerous than the entanglements of the veil of words, he

will never arrive at that higher consciousness, that superconsciousness

(Samâdhi), which will consume him back into the Âtman from which he came.

As the fall of the Âtman arises from the cry "It is I," so does the fall of

the Self-consciousness of the universe-man arise through that Self-

consciousness crying "I am it," thereby identifying the shadow with the

substance; from this fall arises the first veil we had occasion to mention,

the veil of duality, of words, of belief.

This duality we find even in the texts of the oldest Upanishads, such as in

Brihadâranjaka, 3. 4. 1. "It is thy soul, {57} which is within all." And

also again in the same Upanishad (I. 4. 10.), "He who worships another

divinity (than the Âtman), and says ’it is one and I am another’ is not wise,

but he is like a house-dog of the gods." And house-dogs shall we remain so

long as we cling to a belief in a knowing subject and an known object, or in

the worship of anything, even of the Âtman itself, as long as it remains apart

from ourselves. Such a delemma as this does not take long to induce one of

those periods of "spiritual dryness," one of those "dark nights of the soul"

so familiar to all mystics and even to mere students of mysticism. And such a

night seems to have closed around Yâjñavalkhya when he exclaimed:

After death there is no consciousness. For where there is as it were a

duality, there one sees the other, smells, hears, addresses, comprehends, and

knows the other; but when everything has become to him his own self, how

should he smell, see, hear, address, understand, or know anyone at all? How

should he know him, through whom he knows all this, how should he know the

knower?22

Thus does the Supreme Âtman become unknowable, on account of the individual

Âtman23 remaining unknown; and further, will remain unknowable as long as consciousness of a separate Supremacy exists in the heart of the individual.

Directly the seeker realizes this, a new reality is born, and the clouds of

night roll back and melt away before the light of a breaking dawn, brilliant

beyond all that have preceded it. Destroy this consciousness, and the

Unknowable may become the Known, or at least the Unknown, in the sense of the

undiscovered. Thus we find the old Vedantist presupposing an Âtman and a

σύμβολον of it, so that he might better transmute

{58} the unknown individual soul into the known, and the unknowable Supreme

Soul into the unknown, and the, from the knowable through the known to the

knower, get back to the Âtman and Equilibrium—Zero.

All knowledge he asserts to be Mâyâ, and only by paradoxes is the Truth

revealed.

These dark nights of Scepticism descent upon all systems just as they

descend upon all individuals, at no stated times, but as a reaction after much

hard work; and usually they are forerunners of a new and higher realization of

another unknown land to explore. Thus again and again do we find them rising

and dissolving like some strange mist over the realms of the Vedânta. To

disperse them we must consume them in that same fire which has consumed all we

held dear; we must turn our engines of war about and destroy our sick and

wounded, so that those who are strong and whole may press on the faster to

victory.

As early as the days of the Rig Veda, before the beginning was, there was

"neither not-being nor yet being." This thought again and again rumbles

through the realms of philosophy, souring the milk of man’s understanding with

its bitter scepticism.

All these are vain attempts to obscure the devotee’s mind into believing in

that Origin he could in no way understand, by piling up symbols of extravagant

vastness. all, as with the Qabalists, was based on Zero, all, same one thing,

and this one thing saved the mind of man from the fearful palsy of doubt which

had shaken to ruin his brave certainties, his audacious hopes and his

invincible resolutions. Man, slowly through all his doubts, began to realize

that if indeed all were Mâyâ, a matter of words, he at least existed. "I am,"

he cried, no longer, "I am it."26

And with the Îsâ Upanishad he whispered:

Abandoning this limbo of Causality, just as the Buddhist did at a later

date, he tackled the practical problem "What am I? To hell with God!"

The self is the basis for the validity of proof, and therefore is

constituted also before the validity of proof. And because it is thus formed

it is impossible to call it in question. For we many call a thing in question

which comes up to us from without, but not our own essential being. For if a

man calls it in question yet is it his own essential being.

An integral part is here revealed in each of us which is a reality, perhaps

the only reality it is given us to know, and {60} one we possess irrespective

our our not being able to understand it. We have a soul, a veritable living

Âtman, irrespective of all codes, sciences, theories, sects and laws. What

then is this Âtman, and how can we understand it, that is to say, see it

solely, or identify all with it?

The necessity of doing this is pointed out in Chândogya, 8. 1. 6.

He who departs from this world without having known the soul or those true

desires, his part in all worlds is a life of constraint; but he who departs

from this world after having known the soul and those true desires, his part

in all worlds is a life of freedom.

In the Brihadâranjaka,27 king Janaka asks Yâjñavalkhya, "what serves man

for light?" That sage answers:

The sun serves him for light. When however the sun has set?—the moon.

And when he also has set?—fire. And when this also is extinguished? ---

the voice. And when this also is silenced? Then is he himself his own

light.28

This passage occurs again and again in the same form, and in paraphrase, as

we read through the Upanishads. In Kâthaka 5. 15 we find:

And again in Maitrâyana, 6. 24.

When the darkness is pierced through, then is reached that which is not

affected by darkness; and he who has thus pierced through that which is so

affected, he has beheld like a glittering circle of sparks Brahman bright as

the sun, endowed with all might, beyond the reach of darkness, that shines in

yonder sun as in the moon, the fire and the lightning.

Thus the Âtman little by little came to be known and no longer believed in;

yet at first it appears that those who realized it kept their methods to

themselves, and simply explained to their followers its greatness and

splendour by parable and fable, such as we find in Brihadâranyaka, 2. 1. 19.

That is his real form, in which he is exalted above desire, and is free

from evil and fear. For just as one who dallies with a beloved wife has no

consciousness of outer or inner, so the spirit also dallying with the self,

whose essence is knowledge, has no consciousness of inner or outer. That is

his real form, wherein desire is quenched, and he is himself his own desire,

separate from desire and from distress. Then the father is no longer father,

the mother no longer mother, the worlds no longer worlds, the gods no longer

gods, the Vedas no longer Vedas. ... This is his supreme goal.

As theory alone cannot for ever satisfy man’s mind in the solution of the

life-riddle, so also when once the seeker has become the seer, when once

actual living men have attained and become Adepts, their methods of attainment

cannot for long remain entirely hidden.30 And either from their teachings

directly, or from those of their disciples, we find in India {62} sprouting up

from the roots of the older Upanishads two great systems of practical

philosophy:

The first seeks, by artificial means, to suppress desire. The second by

scientific experiments to annihilate the consciousness of plurality.

In the natural course of events the Sannyâsa precedes the Yoga, for it

consists in casting off from oneself home, possessions, family and all that

engenders and stimulates desire; whilst the Yoga consists in withdrawing the

organs of sense from the objects of sense, and by concentrating them on the

Inner Self, Higher Self, Augoeides, Âtman, or Adonai, shake itself free from

the illusions of Mâyâ—the world of plurality, and secure union with this

Inner Self or Âtman. {63}

ACCORDING to the Shiva Sanhita there are two doctrines found in the Vedas: the

doctrines of "Karma Kânda" (sacrificial works, etc.) and of "Jana Kânda"

(science and knowledge). "Karma Kânda" is twofold—good and evil, and

according to how we live "there are many enjoyments in heaven," and "in hell

there are many sufferings." Having once realized the truth of "Karma Kânda"

the Yogi renounces the works of virtue and vice, and engages in "Jnana Kânda"

--- knowledge.

In the Shiva Sanhita we read:31

In the proper season, various creatures are born to enjoy the consequences

of their karma.32 As though mistake mother-of-pearl is taken for silver, so

through the error of one’s own karma man mistakes Brahma for the universe.

Being too much and deeply engaged in the manifested world, the delusion

arises about that which is manifested—the subject. There is no other

cause (of this delusion). Verily, verily, I tell you the truth.

If the practiser of Yoga wishes to cross the ocean of the world, he should

renounce all the fruits of his works, having preformed all the duties of his

âshrama.33

"Jnana Kânda" is the application of science to "Karma Kânda," the works of

good and evil, that is to say of Duality. {64} Little by little it eats away

the former, as strong acid would eat away a piece of steel, and ultimately

when the last atom has been destroyed it ceases to exist as a science, or as a

method, and becomes the Aim, i.e., Knowledge. This is most beautifully

described in the above-mentioned work as follows:

34. That Intelligence which incites the functions into the paths of virtue

and vice "am I." All this universe, moveable and immovable, is from me; all

things are seen through me; all are absorbed into me;34 because there exists

nothing but spirit, and "I am that spirit." There exists nothing else.

35. As in innumerable cups full of water, many reflections of the sun are

seen, but the substance is the same; similarly individuals, like cups, are

innumerable, but the vivifying spirit like the sun is one.

49. All this universe, moveable or immoveable, has come out of

Intelligence. Renouncing everything else, take shelter of it.

50. As space pervades a jar both in and out, similarly within and beyond

this ever-changing universe there exists one universal Spirit.

58. Since from knowledge of that Cause of the universe, ignorance is

destroyed, therefore the Spirit is Knowledge; and this Knowledge is

everlasting.

59. That Spirit from which this manifold universe existing in time takes

its origin is one, and unthinkable.

62. Having renounced all false desires and chains, the Sanny?si and Yogi

see certainly in their own spirit the universal Spirit.

63. Having seen the Spirit that brings forth happiness in their own spirit,

they forget this universe, and enjoy the ineffable bliss of Samâdhi.35

As in the West there are various systems of Magic, so in the East are there

various systems of yoga, each of which purports to lead the aspirant from the

realm of Mâyâ to that of Truth in Samâdhi. The most important of these are:

The two chief of these six methods according to the Bhagavad-Gâta are: Yoga

by Sâñkhya (Raja Yoga), and Yoga by Action (Karma Yoga). But the difference

between these two is to be found in their form rather than in their substance;

for, as Krishna himself says:

Renunciation (Raja Yoga) and Yoga by action (Karma Yoga) both lead to the

highest bliss; of the two, Yoga by action is verily better than renunciation

by action ... Children, not Sages, speak of the Sâñkhya and the Yoga as

different; he who is duly established in one obtaineth the fruits of both.

That place which is gained by the Sâñkhyas is reached by the Yogis also. He

seeth, who seeth that the Sâñkhya and the Yoga are one.37

Or, in other words, he who understand the equilibrium of action and

renunciation (of addition and subtraction) is as he who perceives that in

truth the circle is the line, the end the beginning.

To show how extraordinarily closely allied are the methods of Yoga to those

of Magic, we will quote the following three verses from the Bhagavid-Gâta,

which, with advantage, the reader may compare with the citations already made

from the works of Abramelin and Eliphas Levi.

When the mind, bewildered by the Scriptures (Shruti), shall stand

immovable, fixed in contemplation (Samâdhi), then shalt thou attain to Yoga.38

Whatsoever thou doest, whatsoever thou eatest, whatsoever thou offerest,

{66} whatsoever thou givest, whatsoever thou dost of austerity, O Kaunteya, do

thou that as an offering unto Me.

On Me fix thy mind; be devoted to Me; sacrifice to Me; prostrate thyself

before Me; harmonized thus in the SELF (Âtman), thou shalt come unto Me,

having Me as thy supreme goal.39

These last two verses are taken from "The Yoga of the Kingly Science and

the Kingly Secret"; and if put into slightly different language might easily

be mistaken for a passage out of "the Book of the Sacred Magic."

Not so, however, the first, which is taken from "The Yoga by the Sâñkhya,"

and which is reminiscent of the Quietism of Molinos and Madam de Guyon rather

than of the operations of a ceremonial magician. And it was just this Quietism

that P. as yet had never fully experienced; and he, realizing this, it came

about that when once the key of Yoga was proffered him, he preferred to open

the door of Renunciation and close that of Action, and to abandon the Western

methods by the means of which he had already advanced so far rather than to

continue in them. This in itself was the first great Sacrifice which he made

upon the path of Renunciation—to abandon all that he had as yet attained

to, to cut himself off from the world, and like an Hermit in a desolate land

seek salvation by himself, through himself and of Himself. Ultimately, as we

shall see, he renounced even this disownment, for which he now sacrificed all,

and, by an unification of both, welded the East to the West, the two halves of

that perfect whole which had been lying apart since that night wherein the

breath of God moved upon the face of the waters and the limbs of a living

world struggled from out the Chaos of Ancient Night. {67}

DIRECT experience is the end of Yoga. How can this direct experience be

gained? And the answer is: by Concentration or Will. Swami Vivekânanda on

this point writes:

Those who really want to be Yogis must give up, once for all, this nibbling

at things. Take up one idea. Make that one idea your life; dream of it;

think of it; live on that idea. Let the brain, the body, muscles, nerves,

every part of your body, be full of that idea, and just leave every other idea

alone. This is the way to success, and this is the way great spiritual giants

are produced. others are mere talking machines. ... To succeed, you must have

tremendous perseverance, tremendous will. "I will drink the ocean," says the

persevering soul. "At my will mountains will crumble up." Have that sort of

energy, that sort of will, work hard, and you will reach the goal.40

"O Keshara," cries Arjuna, "enjoin in me this terrible action!" This will

TO WILL.

To turn the mind inwards, as it were, ad stop it wandering outwardly, and

then to concentrate all its powers upon itself, are the methods adopted by the

Yogi in opening the closed Eye which sleeps in the hear to every one of us,

and to create this will TO WILL. By doing so he ultimately comes face to face

with something which is indestructible, on account of it being uncreatable,

and which knows no dissatisfaction. {68}

Every child is aware that the mind possesses a power known as the

reflective faculty. We hear ourselves talk; and we stand apart and see

ourselves work and think. we stand aside from ourselves and anxiously or

fearlessly watch and criticize our lives. There are two persons in us,—

the thinker (or the worker) and the seer. The unwinding of the hoodwink from

the eyes of the seer, for in most men the seer in, like a mummy, wrapped in

the countless rags of thought, is what Yoga purposes to do: in other words to

accomplish no less a task than the mastering of the forces of the Universe,

the surrender of the gross vibrations of the external world to the finer

vibrations of the internal, and then to become one with the subtle Vibrator

—the Seer Himself.

We have mentioned the six chief systems of yoga, and now before entering

upon what for us at present must be the two most important of them,—

namely, Hatha Yoga and Raja Yoga, we intend, as briefly as possible, to

explain the remaining four, and also the necessary conditions under which all

methods of Yoga should be practised.

GNANA YOGA. Union through Knowledge.

Gana Yoga is that Yoga which commences with a study of the impermanent

wisdom of this world and ends with the knowledge of the permanent wisdom of

the Âtman. Its first stage is Viveka, the discernment of the real from the

unreal. Its second Vairâgya, indifference to the knowledge of the world, its

sorrows and joys. Its third Mukti, release, and unity with the Âtman.

In the fourth discourse of the Bhagavad Gîta we find Gana Yoga praised as

follows: {69}

Better than the sacrifice of any objects is the sacrifice of wisdom, O

Paratapa. All actions in their entirety, O Pârtha, culminate in wisdom.

As the burning fire reduces fuel to ashes, O Arjuna, so doth the fire of

wisdom reduce all actions to ashes.

Verily there is nothing so pure in this world as wisdom; he that is

perfected in Yoga finds it in the Âtman in due season.41

KARMA YOGA. Union through Work.

Very closely allied to Gana Yoga is Karma Yoga, Yoga through work, which

may seem only a means towards the former. But this is not so, for not only

must the aspirant commune with the Âtman through the knowledge or wisdom he

attains, but also through the work which aids him to attain it.

A good example of Karma Yoga is quoted from Chuang-Tzu by Flagg in his work

on Yoga. It is as follows:

Prince Hui’s cook was cutting up a bullock. Every blow of his hand, every

heave of his shoulders, every tread of his foot, every thrust of his knee,

every whshh of rent flesh, every chhk of the chopper, was in perfect harmony,

--- rhythmical like the dance of the mulberry grove, simultaneous like the

chords of Ching Shou." "Well done," cried the Prince; "yours is skill

indeed." "Sir," replied the cook, "I have always devoted myself to Tao (which

here means the same as Yoga). "It is better than skill." When I first began to

cut up bullocks I saw before me simply whole bullocks. After three years’

practice I saw no more whole animals. And now I work with my mind and not

with my eye. when my senses bid me stop, but my mind urges me on, I fall

back upon eternal 70 principles. I follow such openings or cavities as there

may be, according to the natural constitution of the animal. A good cook

changes his chopper once a year, because he cuts. An ordinary cook once a

month—because he hacks. But I have had this chopper nineteen years, and

although I have cut up many thousand bullocks, its edge is as if fresh from

the whetstone.42

MANTRA YOGA. Union through Speech.

This type of Yoga consists in repeating a name or a sentence or verse over

and over again until the speaker and the word spoken become one in perfect

concentration. Usually speaking it is used as an adjunct to some other

practice, under one or more of the other Yoga methods. Thus the devotee to

the God Shiva will repeat his name over and over again until at length the

great God opens his Eye and the world is destroyed.

Some of the most famous mantras are:

"Aum mani padme Hum."

"Aum Shivaya Vashi."

"Aum Tat Sat Aum."

"Namo Shivaya namaha Aum."

The pranava AUM43 plays an important part throughout the whole of Indian

Yoga, and especially is it considered sacred by the Mantra-Yogi, who is

continually using it. To pronounce it properly the "A" is from the throat,

the "U" in the middle, and the "M" at the lips. This typifies the whole

course of breath. {71}

It is the best support, the bow off which the soul as the arrow flies to

Brahman, the arrow which is shot from the body as bow in order to pierce the

darkness, the upper fuel with which the body as the lower fuel is kindled by

the fire of the vision of God, the net with which the fish of Prâna is drawn

out, and sacrificed in the fire of the Âtman, the ship on which a man voyages

over the ether of the heart, the chariot which bears him to the world of

Brahman.44

At the end of the "Shiva Sanhita" there are some twenty verses dealing with

the Mantra. And as in so many other Hindu books, a considerable amount of

mystery is woven around these sacred utterances. We read:

190. In the four-petalled Muladhara lotus is the seed of speech, brilliant

as lightning.

191. In the heart is the seed of love, beautiful as the Bandhuk flower.

In the space between the two eyebrows is the seed of Shakti, brilliant as tens

of millions of moons. These three seeds should be kept secret.45

These three Mantras can only be learnt from a Guru, and are not given in

the above book. By repeating them a various number of times certain results

happen. Such as: after eighteen lacs, the body will rise from the ground and

remain suspended in the air; after an hundred lacs, "the great yogi is

absorbed in the Para-Brahman.46

BHAKTA YOGA. Union by love.

In Bhakta Yoga the aspirant usually devotes himself to some special deity,

every action of his life being done in honour and glory of this deity, and, as

Vivekânanda tells us, "he has not to suppress any single one of his emotions,

he only strives to intensify them and direct them to god." Thus, if he

devoted himself to Shiva, he must reflect in his life to his utmost the life

of Shiva; if to Shakti the life of Shakti, unto the seer and the seen become

one in he mystic union of attainment. {72}

Of Bhakta Yoga the "Nârada Sûtra" says:

58. Love (Bhakti) is easier than other methods.

59. Being self-evident it does not depend on other truths.

60. And from being of the nature of peace and supreme bliss.47

This exquisite little Sûtra commences:

1. will now explain Love.

2. Its nature is extreme devotion to some one.

3. Love is immortal.

4. Obtaining it man becomes perfect, becomes immortal, becomes satisfied.

5. And obtaining it he desires nothing, grieves not, hates not, does not

delight, makes no effort.

6. Knowing it he become intoxicated, transfixed, and rejoices in the Self

(Âtman).

This is further explained at the end of Swâtmârâm Swâmi’s "Hatha-Yoga."

Bhakti really means the constant perception of the form of the Lord by the

Antahkarana. There are nine kinds of Bahktis enumerated. hearing his

histories and relating them, remembering him, worshipping his feet, offering

flowers to him, bowing to him (in soul), behaving as his servant, becoming his

companion and offering up one’s Âtman to him. ... Thus, Bhakti, in its most

transcendental aspect, is included in Sampradnyâta Samâdhi.48 {73}

The Gnana Yoga P., as the student, had already long prctised in his study of

the Holy Qabalah; so also had he Karma Yoga by his acts of service whilst a

Neophyte in the Order of the Golden Dawn; but now at the suggestion of D. A.

he betook himself to practice of Hatha and Raja Yoga.

Hatha Yoga and Raja Yoga are so intimately connected, that instead of

forming two separate methods, they rather form the first half and second half

of one and the same.

Before discussing either the Hatha or Raja Yogas, it will be necessary to

explain the conditions under which Yoga should be performed. These conditions

being the conventional ones, each individual should by practice discover those

more particularly suited to himself.

i. The Guru.

Before commencing any Yoga practice, according to every Hindu book upon

this subject, it is first necessary to find a Guru,49 to teacher, to whom the

disciple (Chela) must entirely devote himself: as the "Shiva Sanhita" says:

11. Only the knowledge imparted by a Guru is powerful and useful; otherwise

it becomes fruitless, weak and very painful.

12. He who attains knowledge by pleasing his Guru with every attention,

readily obtains success therein.

13. There is not the least doubt that Guru is father, Guru is mother, and

Guru is God even: and as such, he should be served by all, with their thought,

word and deed.50

ii. Place. Solitude and Silence.

The place where Yoga is performed should be a beautiful and pleasant place,

according to the Shiva Sanhita.51 In the {74} Kshurikâ Upanishad, 2. 21, it

states that "a noiseless place" should be chosen; and in S’vetâs’vatara, 2.

10:

Let the place be pure, and free also from boulders and sand,

Free from fire, smoke, and pools of water,

Here where nothing distracts the mind or offends the eye,

In a hollow protected from the wind a man should compose himself.

The dwelling of a Yogi is described as follows:

The practiser of Hathayoga should live alone in a small Matha or monastery

situated in a place free from rocks, water and fire; of the extent of a bow’s

length, and in a fertile country ruled over by a virtuous king, where he will

not be disturbed.

The Mata should have a very small door, and should be without any windows;

it should be level and without any holes; it should be neither too high nor

too long. It should be very clean, being daily smeared over with cow-dung,

and should be free from all insects. Outside it should be a small corridor

with a raised seat and a well, and the whole should be surrounded by a wall.

...52

iii. Time.

The hours in which Yoga should be performed vary with the instructions of

the Guru, but usually they should be four times a day, at sunrise, mid-day,

sunset and mid-night.

iv. Food.

According to the "Hatha-Yoga Pradipika": "Moderate {75} diet is defined to

mean taking pleasant and sweet food, leaving one fourth of the stomach free,

and offering up the act to Shiva."53

Things that have been once cooked and have since grown cold should be

avoided, also foods containing an excess of salt and sourness. Wheat, rice,

barley, butter, sugar, honey and beans may be eaten, and pure water and milk

drunk. The Yogi should partake of one meal a day, usually a little after

noon. "Yoga should not be practised immediately after a meal, nor when one is

very hungry; before beginning the practice, some milk and butter should be

taken."54

v. Physical considerations.

The aspirant to Yoga should study his body as well as his mind, and should

cultivate regular habits. He should strictly adhere to the rules of health

and sanitation. He should rise an hour before sunrise, and bathe himself

twice daily, in the morning and thee evening, with cold water (if he can do so

without harm to his health). His dress should be warm so that he is not

distracted by the changes of weather.

vi. Moral considerations.

The yogi should practise kindness to all creatures, he should abandon

enmity towards any person, "pride, duplicity, and crookedness" ... and the

"companionship of women."55 Further, in Chapter 5 of the "Shiva Sanhaita" the

hindrances {76} of Enjoyment, Religion and Knowledge are expounded at some

considerable length. Above all the Yogi "should work like a master and not

like a slave."56

HATHA YOGA. Union by Courage.

It matters not what attainment the aspirant seeks to gain, or what goal he

has in view, the one thing above all others which is necessary is a healthy

body, and a body which is under control. It is hopeless to attempt to obtain

stability of mind in one whose body is ever leaping from land to water like a

frog; with such, any sudden influx of illumination may bring with it not

enlightenment but mania; there fore it is that all the great masters have set

the task of courage before that of endeavour.57 He who dares to will, will

will to know, and knowing will keep silence;58 for even to such as have

entered the Supreme Order, there is not way found whereby they may break the

stillness and communicate to those who have not ceased to hear.59 The

guardian of the Temple is Adonai, he alone holds the key of the Portal, seek

it of Him, for there is none other that can open for thee the door.

Now to dare much is to will a little, so it comes about that though Hatha

Yoga is the physical Yoga which teaches the aspirant how to control his body,

yet is it also Raja Yoga {77} which teach him how to control his mind. Little

by little, as the body comes under control, does the mind assert its sway over

the body; and little by little, as the mind asserts its sway, does it come

gradually, little by little under the rule of the Âtman, until ultimately the

Âtman, Augoeides, Higher Self or Adonai fills the Space which was once

occupied solely by the body and mind of the aspirant. Therefore though the

death of the body as it were is the resurrection of the Higher Self

accomplished, and the pinnacles of that Temple, whose foundations are laid

deep in the black earth, are lost among the starry Palaces of God.

In the "Hatha-Yoga Pradipika" we read that "there can be no Raja Yoga

without Hatha Yoga, and vice versa, that to those who wander in the darkness

of the conflicting Sects unable to obtain Raja Yoga, the most merciful

Swâtmârâma Yogi offers the light of Hathavidya."60

In the practice of this mystic union which is brought about by the Hatha

Yoga and the Raja Yoga exercises the conditions necessary are:

As regards the first two of the above stages we need not deal with them at

any length. Strictly speaking, they come under the heading of Karma and Gnana

Yoga, and as it were form the Evangelicism of Yoga—the "Thou shalt" and

"Thou shalt not." They vary according to definition and sect.61 However, one

point must be explained, and this is, that it must be remembered that most

works on Yoga are written either by men like Patanjali, to whom continence,

truthfulness, etc., are simple illusions of mind; or by charlatans, who

imagine that, by displaying to the reader a mass of middle-class "virtues,"

their works will be given so exalted a flavour that they themselves will pass

as great ascetics who have out-soared the bestial passions of life, whilst in

fact they are running harems in Boulogne or making indecent proposals to

flower-girls in South Audley Street. These latter ones generally trade under

the exalted names of The Mahatmas; who, {79} coming straight from the Shâm

Bazzaar, retail their wretched bă k băk to their sheep-headed followers as the

eternal word of Brahman—"The shower from the Highest!" And, not

infrequently, end in silent meditation within the illusive walls of Wormwood

Scrubbs.

The East like the West, has for long lain under the spell of that potent

but Middle-class Magician—St. Shamefaced sex; and the whole of its

literature swings between the two extremes of Paederasty and Brahmach?rya.

Even the great science of Yoga has not remained unpolluted by his breath, so

that in many cases to avoid shipwreck upon Scylla the Yogi has lost his life

in the eddying whirlpools of Charybdis.

The Yogis claim that the energies of the human body are stored up in the

brain, and the highest of these energies they call "Ojas." they also claim

that that part of the human energy which is expressed in sexual passion, when

checked, easily becomes changed into Ojas; and so it is that they invariably

insist in their disciples gathering up the sexual energy and converting it

into Ojas. Thus we read:

It is only the chaste man and woman who can make the Ojas rise and become

stored in the brain, and this is why chastity has always been considered the

highest virtue. ... That is why in all the religious orders in the world that

have produced spiritual giants, you will always find this intense chastity

insisted upon. ...62 If people practise Raja-Yoga and at the same time lead

an impure life, how can they expect to become Yogis?63 {80}

This argument would appear at first sight to be self-contradictory, and

therefore fallacious, for, if to obtain Ojas is so important, how then can it

be right to destroy a healthy passion which is the chief means of supplying it

with the renewed energy necessary to maintain it? The Yogi’s answer is simple

enough: Seeing that the extinction of the first would mean the ultimate death

of the second the various Mudra exercises wee introduced so that this healthy

passion might not only be preserved, but cultivated in the most rapid manner

possible, without loss of vitality resulting from the practices adopted.

Equilibrium is above all things necessary, and even in these early stages, the

mind of the aspirant should be entirely free from the obsession of either

ungratified or over-gratified appetites. Neither Lust nor Chastity should

solely occupy him; for as Krishna says:

Verily Yoga is not for him who eateth too much, nor who abstaineth to

excess, nor who is too much addicted to sleep, nor even to wakefulness, O

Arjuna.

Yoga killeth out all pain for him who is regulated in eating and amusement,

regulated in performing actions, regulated in sleeping and waking.64

This balancing of what is vulgarly known as Virtue and Vice,65 and which

the Yogi Philosophy does not always appreciate, is illustrated still more

forcibly in that illuminating work "Konx om Pax," in which Mr. Crowley writes:

As above so beneath! said Hermes the thrice greatest. The laws of the

physical world are precisely paralleled by those of the moral and intellectual

sphere. To the prostitute I prescribe a course of training by which she shall

{81} comprehend the holiness of sex. Chastity forms part of that training,

and I should hope to see her one day a happy wife and mother. To the prude

equally I prescribe a course of training by which she shall comprehend the

holiness of sex. Unchastity forms part of that training, and I should hope to

see her one day a happy wife and mother.

To the bigot I commend a course of Thomas Henry Huxley; to the infidel a

practical study of ceremonial magic. Then, when the bigot has knowledge of

the infidel faith, each may follow without prejudice his natural inclination;

for he will no longer plunge into his former excesses.

So also she who was a prostitute from native passion may indulge with

safety in the pleasure of love; and she who was by nature cold may enjoy a

virginity in no wise marred by her disciplinary course of unchastity. But the

one will understand and love the other.66

Once and for all do not forget that nothing in this world is permanently

good or evil; and, so long as it appears to be so, then remember that the

fault is the seer’s and not in the thing seen, and that the seer is still in

an unbalanced state. Never forget Blake’s words:

"Those who restrain desire do so because theirs is weak enough to be

restrained; and the restrainer or reason usurps its place and governs the

unwilling."67 Do not restrain your desires, but equilibrate them, for: "He

who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence."68 Verily: "Arise, and drink

your bliss, for everything that lives is holy."69

The six acts of purifying the body by Hatha-Yoga are Dhauti, Basti, Neti,

Trataka, Nauli and Kapâlabhâti,70 each of {82} which is described at length by

Swâtmârân Swami. But the two most important exercise which all must undergo,

should success be desired, are those of A’sana and Prânâyâma. The first

consists of physical exercises which will gain for him who practises them

control over the muscles of the body, and the second over the breath.

The A’sanas, or Positions.

According to the "Pradipika" and the "Shiva Sanhita," there are 84 A’sanas;

but Goraksha says there are as many A’sana as there are varieties of beings,

and that Shiva has counted eighty-four lacs of them.71 The four most

important are: Siddhâsana, Padmâsana, Ugrâsana and Svastikâsana, which are

described in the Shiva Sanhita as follows:72

The Siddhâsana. By "pressing with care by the (left) heel the yoni,73 the

other heel the Yogi should place on the lingam; he should fix his gaze upwards

on the space between the two eyebrows ... and restrain his senses."

The Padmâsana. By crossing the legs "carefully place the feet on the

opposite thighs (the left on the right thing and vice versâ," cross both hands

and place them similarly on the thighs; fix the sight on the tip of the nose."

The Ugrâsana. "Stretch out both the legs and keep them apart; firmly take

hold of the head by the hands, and place it on the knees."

The Svastikâsana. "Place the soles of the feet completely under the

thighs, keep the body straight and at ease."

For the beginner that posture which continues for the {83} greatest length

of time comfortable is the correct one to adopt; but the head, neck and chest

should always be held erect, the aspirant should in fact adopt what the drill-

book calls "the first position of a soldier," and never allow the body in any

way to collapse. The "Bhagavad-Gâta" upon this point says:

In a pure place, established in a fixed seat of his own, neither very much

raised nor very low ... in a secret place by himself. ... There ... he should

practise Yoga for the purification of the self. Holding the body, head and

neck erect, immovably steady, looking fixedly at the point of the nose and

unwandering gaze.

When these posture have been in some way mastered, the aspirant must

combine with them the exercises of Prânâyâma, which will by degrees purify the

Nâdi or nerve-centres.

These Nâdis, which are usually set down as numbering 72,000,74 ramify from

the heart outwards in the pericardium; the three chief are the Ida, Pingala

and Sushumnâ,75 the last of which is called "the most highly beloved of the

Yogis."

Besides practising Prânâyâma he should also perform one {84} or more of the

Mudras, as laid down in the "Hatha Yoga Pradipika" and the "Shiva Sanhita," so

that he may arouse the sleeping Kundalini, the great goddess, as she is

called, who sleeps coiled up at the mouth of the Sushumnâ. But before we deal

with either of these exercises, it will be necessary to explain the Mystical

Constitution of the human organism and the six Chakkras which constitute the

six stages of the Hindu Tau of Life.

Firstly, we have the Âtman, the Self or Knower, whose being consists in a

trinity in unity of, Sat, Absolute Existence; Chit, Wisdom; Ananda, Bliss.

Secondly, the Anthakârana or the internal instrument, which has five

attributes according to the five elements, thus:

The Atma of Anthakârana has 5 sheaths, called Kos’as.78 {85}

Besides these there are three bodies or Shariras.

According to the Yoga,79 there are two nerve-currents in {86} the spinal

column called respectively Pingala and Ida, and between these is placed the

Sushumnâ, an imaginary tube, at the lower extremity of which is situated the

Kundalini (potential divine energy). Once the Kundalini is awakened it forces

its way up the Sunshumnâ,80 and, as it does so, its progresses is marked by

wonderful visions and the acquisition of hitherto unknown powers.

The Sushumnâ is, as it were, the central pillar of the Tree of Life, and

its six stages are known as the Six Chakkras.81 To these six is added a

seventh; but this one, the Shasr?ra, lies altogether outside the human

organism.

These six Chakkras are:

1. The Mûlâdhara-Chakkra. This Chakkra is situated between the lingam and

the anus at the base of the Spinal Column. It is called the Adhar-Padma, or

fundamental lotus, and it has four petals. "In the pericarp of the Adhar

lotus there is the triangular beautiful yoni, hidden and kept secret in all

the Tantras." In this yoni dwells the goddess Kundalini; she surrounds all

the Nadis, and has three and a half coils. She catches her tail in her own

mouth, and rests in the entrance of the Sushumnâ82 {87}

58. It sleeps there like a serpent, and is luminous by its own light ... it

is the Goddess of speech, and is called the vija (seed).

59. Full of energy, and like burning gold, know this Kundalini to be the

power (Shakti) of Vishnu; it is the mother of the three qualities—Satwa

(good), Rajas (indifference), and Tamas (bad).

60. There, beautiful like the Bandhuk flower, is placed the seed of love;

it is brilliant like burnished gold, and is described in Yoga as eternal.

61. The Sushumnâ also embraces it, and the beautiful seed is there; there

it rests shining brilliantly like the autumnal moon, with the luminosity of

millions of suns, and the coolness of millions of moons. O Goddess! These

three (fire, sun and moon) taken together or collectively are called the vija.

It is also called the great energy.83

In the Mûlâdhara lotus there also dwells a sun between the four petals,

which continuously exudes a poison. This venom (the sun-fluid of mortality)

goes to the right nostril, as the moon-fluid of immortality goes to the left,

by means of the Pingala which rises from the left side of the Ajna lotus.84

The Mûlâdhara is also the seat of the Apâna.

2. The Svadisthâna Chakkra. This Chakkra is situated at the base of the

sexual organ. It has six petals. The colour of this lotus is blood-red, its

presiding adept is called Balakhya and its goddess, Rakini.85

He who daily contemplates on this lotus becomes an object of love and

adoration to all beautiful goddesses. He fearlessly recites the various

Shastras {88} and sciences unknown to him before ... and moves throughout the

universe.86

This Chakkra is the seat of the Sam?na, region about the navel and of the

Apo Tatwa.

3. The Manipûra Chakkra. This Chakkra is situated near the navel, it is

of a golden colour and has ten petals (sometimes twelve), its adept is

Rudrakhya and its goddess Lakini. It is the "solar-plexus" or "city of gems,"

and is so called because it is very brilliant. This Chakkra is the seat of

the Agni Tatwa. Also in the abdomen burns the "fire of digestion of food"

situated in the middle of the sphere of the sun, having ten Kalas (petals)....87

He who enters this Chakkra

Can made gold, etc., see the adepts (clairvoyantly) discover medicines for

diseases, and see hidden treasures.88

4. The Anahata Chakkra. This Chakkra is situated in the heart, it is of a

deep blood red colour, and has twelve petals. It is the seat of Prâna and is

a very pleasant spot; its adept is Pinaki and its goddess is Kakini. This

Chakkra is also the seat of the Vâyu Tatwa.

He who always contemplates on this lotus of the heart is eagerly desired by

the daughters of gods ... has clairaudience, clairvoyance, and can walk in the

air.... He sees the adepts and the goddesses.... 89

5. The Vishuddha Chakkra. This Chakkra is situated in the throat directly

below the larynx, it is of a brilliant gold {89} colour and has sixteen

petals. It is the seat of the Udana and the Âkâsa Tatwa; its presiding adept

is Chhagalanda and its goddess Sakini.

6. The Ajna Chakkra. This Chakkra is situated between the two eyebrows,

in the place of the pineal gland. It is the seat of the Mano Tatwa, and

consists of two petals. Within this lotus are sometimes placed the three

mystical principles of Vindu, Nadi and Shakti.90 "Its presiding adept is

called Sukla-Mahakala (the white great time; also Adhanari—‘Adonai’) its

presiding goddess is called Hakini."91

97. Within that petal, there is the eternal seed, brilliant as he autumnal

moon. The wise anchorite by knowing this is never destroyed.

98. This is the great light held secret in all the Tantras; by

contemplating on this, one obtains the greatest psychic powers, there is no

doubt in it.

99. I am the giver of salvation, I am the third linga in the turya (the

state of ecstasy, also the name of the thousand petalled lotus.92 By

contemplating on This the Yogi becomes certainly like me.93

{Illustration facing page 90 described:

"DIAGRAM 83. The Yogi (showing the Cakkras)."

This is a half tone of a black line vertical rectangle with a white or gray

interior. The lower 3/5’s of the rectangle is occupied by a frontal nude man

exactly as described in the Padmasana Asana described on page 83. He is bald.

The six chakras are depicted as abstract devices at the positions described in

the above text.

Muladhara is placed at the intersection of the crossed ankles, with a bit

of the left ankle showing above and the symbol extending below the ankles: A

dark disk with four petals created by the intersection of to vesicas, one

horizontal and the other vertical. The area of intersection is white, the

petals outside each have a radial rib which stops at the arc of the

intersection of the vesicas. There is an upright equilateral black triangle

in the center of the intersection, small circle with central dot inside that.

Svadisthana is placed at the lower pelvis, shown just above the crossed

ankles. It is not in a circle or disk, but is composed of three intersecting

vesicas forming a curved sided hexagonal shape with "points" to top and

bottom. The intersections of adjacent vesicas form white spaces of three

arcs. The combined intersection of all vesicas forms an area of distinct

color with a dark, vertical and linear hexagram. There is a small white

circle with center point in the midst of this.

Manipura is placed at the center of the abdomen. It is contained in a 20-

pointed white star, outline only and giving the appearance of a ring. Within

this is a black disk. Within the black disk is a figure constructed of five

intersecting vesicas, in a similar fashion to the description for the

Svadisthana but forming a curved sided decagonal shape with "points" to the

top and bottom. Where only two vesicas intersect, the space is dark. Where

three vessicas intersect, the space is light. Where four vesicas intersect,

the space is dark again. Where all five vesicas intersect, there is a

different shade used, and in the midst of this is a vertical ten-pointed star

of lines with a white circle and central dot in the midst.

Anahata is placed in the center of the thorax. It is not in a circle, but

is composed of six intersecting vesicas forming a curved sided duo-dacagonal

shale of twelve "petals" with points to top and bottom. The outer, mono-

vesical parts are gray, two vesicas intersect in white, three in gray. All

other intersections are in a common space to the center, defined by a circle

and a different shade of gray. Free-standing in the center of this is a ring

of twelve shapes, with radials going outward to cut the space into an inner

ring of twelve five curved-sided and inward pointed irregular pentagons. This

inner ring of twelve petals contains a 12 sided star with points at top and

bottom, defining the divisions of the irregular pentagons. The center is an

approximate white circle with point in center.

Vishuddha is placed at the base of the throat. It is composed of a star

ring of sixteen gray leaves with single radial ribs, one leaf to the top.

Within this is a ring of sixteen white petals with dots in the lower lobe,

petals to top and bottom. The center as for Anahata, but sixteenfold.

Ajna on forehead. This is a more western symbol, two upward curving wings

of seven primary feathers and a more complex array of secondaries, curving to

the outside and coming to two points just above the top of the head. These

join in two white featherlets a semicircular curve at the base, just above the

brows. There is a stylized descending gray dove in the midst, just above the

lower white featherlets. A white light seems to be seen through the backs of

the wings just above the dove. For the meaning of the symbolism of these

"closed" wings, see the footnote below, page {147} in the Equinox.

The upper 2/5’s of the space contains a large circular device, representing

the Shasrara. This looks a bit like the head of a thistle and has 72

elongated spikes emanating outward in a circle to define the outer edge of the

next inward feature, a white ring. The spikes have rounded bottoms with a dot

in the center of each, and there are 72 lines drawn radiating outward between

them, one between each pair. Five of these spikes touch and pass behind the

head. Within the white ring are 13 concentric rings of petals, 11 in the

innermost and the number of petals increasing as the rings go outward. The

second petal ring from the center has 22, the next outward about 44. After

that the number of petals ceases doubling, but increases more slowly.

Theoretically there is a total of 1000 such petals in all, but I didn’t count

them all. In the center there is a white circle with a crescent moon in gray

inside, horns upward—this would be the 1,001st petal.}

The Sushumnâ following the spinal cord on reaching the Brahmarandhra (the

hole of Brahman) the junction of the sutures of the skull, by a modification

goes to the right side of the Ajna lotus, whence it proceeds to the left

nostril, and is called the Varana, Ganges (northward flowing Ganges) or Ida.

By a similar modification in the opposite direction the {90} Sushumnâ goes to

the left side of the Ajna lotus and proceeding to the right nostril is called

the Pingala. Jamuna or Asi. The space between these two, the Ida and

Pingala, is called Varanasi (Benares), the holy city of Shiva.

111. He who secretly always contemplates on the Ajna lotus, at once

destroys all the Karma of his past life, without any opposition.

121. Remaining in the place, when the Yogi meditates deeply, idols appear

to him as mere things imagination, I.e., he perceives the absurdity of

idolatry.94

The Sahasrâra, or thousand-and-one-petaled lotus of the brain, is usually

described as being situated above the head, but sometimes in the opening of

the Brahmarandhra, or at the root of the palate. In its centre there is a

Yoni which has its face looking downwards. In the centre of this Yoni is

placed the mystical moon, which is continually exuding an elixir or dew95 ---

this moon fluid of immortality unceasingly flows through the Ida.

In the untrained, and all such as are not Yogis, "Every particle of this

nectar (the Satravi) that flows from the Ambrosial Moon is swallowed up by the

Sun (in the Mûlâdhara Chakkra)96 and destroyed, this loss causes the body to

become old. If the aspirant can only prevent this flow of nectar by closing

the hole in the palate of his mouth (the Prahmarandra), he will be able to

utilize it to prevent the waste of his body. By (91) drinking it he will fill

his whole body with life, and "even though he is bitten by the serpent

Takshaka, the poison does not spread throughout his body."97

Further the "Hatha Yoga Pradipika" informs us that: "When one has closed

the hole at the root of the palate ... his seminal fluid is not emitted even

through he is embraced by a young and passionate woman."

Now this gives us the Key to the whole of this lunar symbolism, and we find

that the Soma-juice of the Moon, dew, nectar, semen and vital force are but

various names for one and the same substance, and that if the vindu can be

retained in the body it may by certain practices which we will now discuss, be

utilized in not only strengthening but in prolonging this life to an

indefinite period.98 These practices are called the Mudras, they are to be

found fully described in the Tantras, and are made us of as one of the methods

of awakening the sleeping Kundalini.99

There are many of these Mudras, the most important being the Yoni-Mudra,

Maha Mudra, Maha Bandha, Maha Vedha, Khechari, Uddiyana, Mula and Salandhara

Bandha, Viparitakarani, Vajroli and Shakti Chalana.

1. The Yoni Mudra.

With a strong inspiration fix the mind in the Adhar lotus; then engage in

contracting the yoni (the space between the lingam and anus). After which

contemplate that the God of love resides in the Brahma-Yoni, and imagine that

an union takes place between Shiva and Shakti.

A full account of how to practise this Mudra is given in the "Shiva

Sanhita";100 but it is both complicated and difficult to carry out, and if

attempted should most certainly be performed under the instruction of a Guru.

2. Maha Mudra.

Pressing the anus with the left heel and stretching out the right leg, take

hold of the toes with your hand. Then practise the Jalandhara Bandha101 and

draw the breath through the Sushumnâ. Then the Kundalini become straight just

as a coiled snake when struck.... Then the two other Nadis (the Ida and

Pingala) become dead, because the breath goes out of them. Then he should

breathe out very slowly and never quickly.102

3. Maha Bandha.

Pressing the anus with the left ankle place the right foot upon the left

thigh. Having drawn in the breath, place the chin firmly on the breast,

contract the anus and fix the mind on the Sushumnâ Nadi. Having restrained

the breath as long as possible, he should then breathe out slowly. He should

practise first on the left side and then on the right.103

4. Maha Vedha.

As a beautiful and graceful woman is of no value without a husband, so Maha

Mudra and Maha Bandha have no value without Maha Vedha.

The Yogi assuming the Maha Bandha posture, should draw in his breath {93}

with a concentrated mind and stop the upward and downward course of the Prânâ

by Jalandhara Bandha. Resting his body upon his palms placed upon the ground,

he should strike the ground softly with his posteriors. By this the Prânâ,

leaving Ida and Pingala, goes through the Sushumnâ. ... The body assumes a

death-like aspect. Then he should breathe out.104

5. Khechari Mudra.

The Yogi sitting in the Vajrâsana (Siddhâsana) posture, should firmly fix

his gaze upon Ajna, and reversing the tongue backwards, fix it in the hollow

under the epiglottis, placing it with great care on the mouth of the well of

nectar.105

6. Uddiyana Mudra.

The drawing up of the intestines above and below the navel (so that they

rest against the back of the body high up the thorax) is called Uddiyana

Bandha, and is the lion that kills the elephant Death.106

7. Mula Mudra.

Pressing the Yoni with the ankle, contract the anus and draw the Apâna

upwards. This is Mula Bandha.107

8. Jalandhara Mudra.

Contract the throat and press the chin firmly against the breast (four

inches from the heart). This is Jalandhara Bandha. ...108

9. Viparitakarani Mudra.

This consists in making the Sun and Moon assume exactly reverse positions.

The Sun which is below the navel and the Moon which is above the palate change

places. This Mudra {94} must be learnt from the Guru himself, and though, as

we are told in the "Pradipika," a theoretical study of crores of Shastras

cannot throw any light upon it, yet nevertheless in the "Shiva Sanhita" the

difficulty seems to be solved by standing on one’s head.109

10. Shakti Chalana Mudra.

Let the wise Yogi forcibly and firmly draw up the goddess Kundalini

sleeping in the Adhar lotus, by means of the Apana-Vâyu. This is Shakti-

Chalan Mudra. ...110

The "Hatha Yoga Pradipika" is very obscure on this Mudra, it says:

As one forces open a door with a key, so the Yogi should force open the

door of Moksha (Deliverance) by the Kundalini.

Between the Ganges and the Jamuna there sits the young widow inspiring

pity. he should despoil her forcibly, for it leads one to the supreme seat of

Vishnu.

You should awake the sleeping serpent (Kundalini) by taking hold of its

tail....111