First Printed 1966

Copyright © 1966 J.G. Bennett

Coombe Springs Press Edition 1976

Claymont Communications Edition 1985

ISBN 0-934254-09-5

Claymont Communications

Box 112

Charles Town, W.Va.

25414

PREFACE

This third volume of The Dramatic Universe is to appear at the same

time as the fourth and last volume of a work which has been one of my

main interests for more than a third of a century.

It has been very hard to bring the work to a stop so that the results

could be published. This is in part due to a temperamental inability to

let well alone, but also and more significantly to a characteristic of the

period in which we live. This characteristic is discussed in the last chap-

ter of the work, where I refer to the explosion of progress that is coming

in every field, and that has gone out of man's control. When this work

was started thirty-five years ago, many notions that I had received from

Gurdjieff and other traditional sources about the nature of man and the

universe appeared to be unsupported speculations. The progress of

science and of psychology in the intervening period has made many of

these notions commonplaces of present-day thought.

There are still, however, a great number that are far ahead of our

time, but the human mind is catching up with its arrears of understand-

ing man and his world, and I hope that this work may help to provide a

framework for lines of thought that at present appear to be unconnected

and yet which by their very nature ought to be built into a coherent

structure. In former times philosophers, and to an even greater degree

theologians, could write about God, man and the universe in a more or

less stationary climate of thought as to the natural order. Man was the

summit of creation, the earth was the centre of the universe. Man had

a single indivisible soul, right and wrong were clearly defined unchange-

able realities. For the philosophers God either existed or did not exist,

but there was no middle path between faith and unbelief. We have passed

through a period when all absolute notions have broken down and the

world is now driving forward with a new dynamism of thought and

action that makes the facts of today the myths of tomorrow, and also

sometimes the myths of yesterday the accepted realities of the present.

In the world of science this explosive situation is creating an almost

insoluble problem of communication. One attempt to meet this is by

the publication of progress reports in the different scientific disciplines.

These have the advantage of being explicitly ephemeral and subject to

revision the following year. If I could have done the same with the

Dramatic Universe—that is, the study of man, the world and God—

my task would have been much easier. This present book has been

written and re-written often enough to have made a whole series of

progress reports on our researches into these themes. These researches

during the last twenty years have been conducted at Coombe Springs

at the Institute for the Comparative Study of History, Philosophy and

the Sciences, which has provided a meeting point for people interested

in all three sides of the problem, that is, the problem of man and his

nature, the problem of the universe and the natural order and scientific

progress, and the problem of the ultimate purpose of our existence which

is the heart of theology. Thanks to many fortunate circumstances, we

have had access to traditional sources which show that in the past men

have understood better some of the questions that we are still struggling

with, though they formulated both their questions and their under-

standing in terms that we find hard to follow. We have also been

fortunate in our connections with the world of science, especially of the

physical sciences, where the human mind has discovered the limitations

of its ability to apprehend the reality of the natural world.

The new discipline of Systematics briefly described in the second

volume has now flourished into a thriving field of research affecting

education, the integration of natural sciences, history, art and politics.

The present state of our understanding of this discipline is reported in

the first chapter of this volume. Had this book been published twelve

months earlier, the chapter would have been very different, and no

doubt twelve months hence we shall have found improvements and

new applications.

In the following chapter the Systematics of Value has been developed.

Comparing this with the Systematics of Factual Categories of Volume I,

it can be seen that the foundations were already there twenty years ago,

but a great deal of progress has been made.

Passing on to the fifteenth part of the work, we have three chapters

on man. The first is an attempt to set up a general anthropology applic-

able to all phases of human life. This is a most necessary undertaking,

though almost impossibly difficult of achievement. Partial anthropologies,

such as are being used in various specialized fields, can lead to absurd

misunderstandings. This Chapter, number 39, is from my point of

view one of the most unsatisfactory of the whole book, because it

attempts to compress into thirty or forty pages what needs a volume to

itself if it is to be adequately presented. Moreover, new discoveries

constantly being made require rather a series of progress reports than

the static form of a treatise.

Chapter 40 on the Life Cycle of a Man presents fewer difficulties

because it is based upon the actual experience of many decades of study

of the process of transformation from conception to death, and in this

field we have a great deal of material and it has been carefully sifted and

tested against experience.

The last chapter of this volume is again tentative and more theoretical

than practical, because it deals with the ideal structure of human society

according to systematic principles and what we can learn from history

and the experience of the modern world.

The decision to divide the end of this work into two volumes was

taken because of the inordinate length of the historical section. It should,

however, be clear that the chapters on history are really the key to

understanding the whole work, so that in a sense this third volume is a

preparation for the last volume which seeks to answer the question posed

at the beginning of the book; for what purpose do we men exist on the

earth, and how are we to fulfil it?

In reading again what I have written, I am aware of the heavy demand

it makes upon the reader's willingness to take a great deal of trouble to

work out ideas that are presented summarily and often without the

illustrations and examples that are needed to show how they work in

practice. Many sections are little more than precis of original versions

far too long to be included. I have been obliged to eliminate hundreds of

references to authorities and quotations that might have helped to con-

vince the reader that we are on the right lines.

The only—but I hope valid—excuse that I can offer is that the under-

taking is far beyond the scope of a single work by a single author. I

firmly believe that the undertaking is necessary and that it will have to

be carried through by those more competent to do so than myself. With

the prodigious transformations of human experience of the twentieth

century, we must needs recast all our views, beliefs and even our forms

of thought regarding man, the universe and God. No single notion,

theory or expression that has reached us from earlier centuries will stand

without revision. And the revision must be total and totally coherent.

It cannot be made piecemeal because every part of our experience is

relevant to every other part. We are living in an age of change un-

precedented in human history by its rapidity. For the first time since

man appeared on the earth, the entire environment of human existence

is changing out of recognition within a single lifetime. The static and

absolute world picture of earlier centuries is useless in such a situation

and must be replaced by dynamic and relative notions that can adapt to

the changing world. All our ideas without exception and all our modes of

thought and even our methods of enquiry and communication must be

thrown into the fire and only those that come through will serve the

needs of mankind. Even these will have to be fused into a new unity. In

the present work, I have set myself to show that an unified world picture

can be constructed that embraces all human experience and all human

knowledge as it presents itself to us in the second half of the twentieth

century. The picture must, of necessity, be defective; but this is not so

important as the demonstration that some sort of total picture is possible.

The possibility turns largely upon discarding views of space, time and

matter, of life, evolution and consciousness, of causality and purpose and

of a 'Knowable Universe' or an 'Absolute Reality' that have been held

for centuries and are still held though less tenaciously by most philoso-

phers, scientists and theologians. In place of these views, I offer the

notions of a six-dimensional physical universe, of the triadic nature of

all experience, of systematics generally, and of the Universe itself as

uncertain and hazardous by the very fact that it exists at all. I believe

that these notions are consistent with all that we discover in our human

experience both private and collective and that even if much is still

speculative and unverifiable, the progress of human understanding will

show that some such view of the world will have to be adopted if we are

to achieve the harmony of science, including anthropology, history in-

cluding human origins, philosophy including ontology and religion in-

cluding the unification of all creeds and practices. Nothing less than such

an all-embracing harmony can satisfy the soul of man.

In my faltering attempts to accomplish so vast a task, I have been

helped above all by my own students and collaborators at the Institute

for the Comparative Study of History, Philosophy and the Sciences. I

must single out Mr. Anthony Blake, who has made himself more

familiar with the undertaking than I would dare claim to be myself.

Mrs. Dee Chalmers and Mr. John Bristow have worked hard to bring

order into the confused presentation of palaeontology, archaeology and

history. The Research Fellows of the Institute, headed by Mr. Anthony

Hodgson, have taken part in innumerable discussions and conducted

many seminars that have helped to clarify one or another theme, speci-

ally those bearing upon Systematics. The many diagrams have been

drawn by Mr Ian McCoig, the Hon. Secretary of the Institute. I am

deeply indebted to him for nearly eight months' work done in his scanty

spare time. Mrs. Joan Edwards has typed, corrected and retyped the

entire work at least ten times in fifteen years: her persistence and skill

place me greatly in her debt. Finally, I must express once again my

appreciation of the patience and forebearance of my publishers who have

borne with me for twenty years since we first signed the contract for

the publication of this work. During these twenty years, the patience of

angels might have been exhausted: but I have never had a word from

them save of encouragement and support. They and I are well aware

that such an undertaking as this makes money for no one and that one

does not expect recognition in one's own lifetime. If some of the notions

developed prove fruitful and contribute to the great reconstruction of

human thinking that is bound to come during the next century, I shall

have accomplished all that I could hope.

We have tried to mitigate the difficulties of the reader by dividing the

subject matter into parts, chapters, sections, and sub-sections, and pro-

viding an extended Table of Contents. We have also made use of bold

type to draw attention to neologisms or words used with a special

meaning. Italics are used for emphasis, for words and phrases in other

languages than English. Quotation marks are used for extracts from

other writings, for direct speech and also to indicate that a word is

treated as a symbol rather than as a linguistic element.

J. G. BENNETT

June 1966

|

CONTENTS PREFACE V FOURTH BOOK: SYSTEMATICS OF HUMAN PART FOURTEEN: SYSTEMS Our growing knowledge of the complexity of the world— 14.37.2. Structures and Systems 7 Structures do not belong to the domain of knowledge but of 14.37.3. The Properties of Systems 12 The progression from abstract to concrete of systems — 14.37.4. The Monad 14 The universe as a total organized complexity—undifferentia- |

|

14.37.5. The Dyad 18 The two ways of defining the monad reveal an ambiguity— 14.37.6. The Triad 23 The dyadic nature of force—the transition to dynamism— 14.37.7. The Tetrad 29 The tetrad is concerned with order—flexibility—activities 14.37.7.1. The Aristotelian Tetrad 35 The dyad of matter and form—for change, a third factor |

|

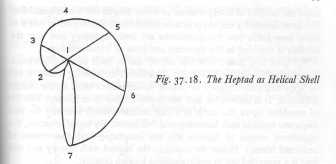

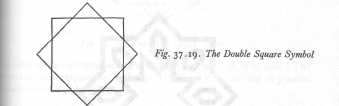

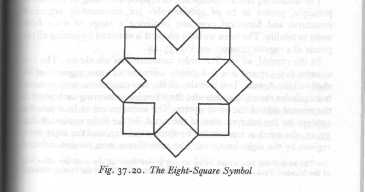

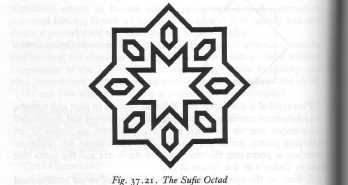

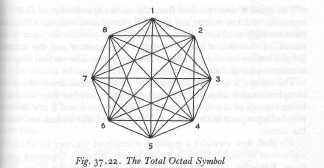

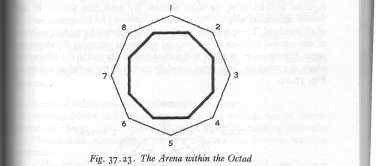

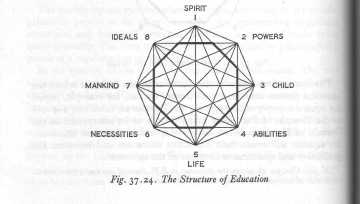

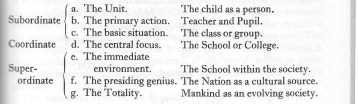

14.37.8. The Pentad 37 The significance of structures is found beyond the tetrad — 14.37.9. The Hexad 44 Situating the structure —eternal and hyparchic elements — 14.37.10. The Heptad 50 Different kinds of change—distinct from kinds of entity 14.37.11. The Octad 57 The symbol from South-West Asia—various forms—notions |

|

contains the atomic and total aspect of the structure—con- 14.37.12. The Ennead 63 Beyond the octad, systems take into account the essential 14.37.13. The Dodecad 72 Integration beyond the ennead—the decad and integrative Chapter 38. values 76 Values are apprehended by an act of judgement—diversity |

|

in Aristotle—the dyad of universal and particular in the 14.38.2. The First Tetrad—Natural Values 82 The ground of value-experience is the sense of uncertainty 14.38.2.1. CONTINGENCY 83 The indifference of Fact—experience—meaning stems 14.38.2.2. CONFLICT 85 The masculine dilemma before contingency—conflict is 14.38.2.3. CONCERN 86 Mutual acceptance—the participation mystique—mutual |

|

14.38.2.4. JOY 87 14.38.3. The Second Tetrad—Personal Values 89 Their purposive character links the natural and the uni- 14.38.3.1. HOPE 90 14.38.3.2. NEED 91 14.38.3.3. DISCRIMINATION 93 The more intelligent and conscious use of the powers—a 14.38.3.4. SERENITY 94 Santosh, the second term of the Hindu triad—the beatitude |

|

14.38.3.5. THE TRANSFORMATION OF The eight values form a progressive series—the four stages 14.38.4. The Third Tetrad—Universal Values 97 The universal values are the inspiration of the Universal 14.38.4.1. TRANSCENDENCE 98 Its meaning in the philosophical systems of Scholastics, 14.38.4.2. HOLINESS 99 The sense of awe before Creation—the mysterium tremen- 14.38.4.3. LOVE 1OO The relatedness which embraces Holiness—Love is never 14.38.4.4. FULFILMENT 101 The consummation of the significance of Creation—futurity |

|

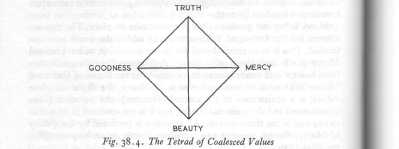

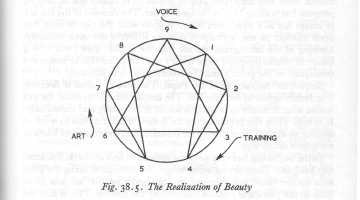

archie—the Sufic Baqa after Fana—in the progression of 14.38.5. The Harmony of Value 103 The general tetrad for the totality of value-activity—the 14.38.5.1. BEAUTY 103 The triad of Transcendence, Contingency and Finality 14.38.5.2. GOODNESS 105 The compendium of virtues—the triad of Holiness, Conflict 14.38.5.3. MERCY 106 Goodness lacks dynamism—the triad of Love, Concern and 14.38.5.4. TRUTH 107 The triad of Joy, Serenity and Fulfilment—the perfect 14.38.6. The Realization of a Value 108 The training of a professional singer as an example of |

|

method—frustrations—stage three—tasks of right singing PART FIFTEEN: SYSTEMATICS AND ANTHROPOLOGY 15.39.1. The Complexity of Human Nature 117 Man is essentially complex—anthropology must take into 15.39.2. Man and His Worlds 119 We should consider all of man's affiliations—first project for 15.39.2.1. THE WORLD OF ENERGIES 122 Man's physical body works through energies which operate |

|

15.39.2.2. THE WORLD OF MATERIAL The body as a material thing—the dyadic character of things 15.39.2.3. LIFE 123 Life is both free and dependent—its universality—our place 15.39.2.4. THE WORLD OF SELVES 124 Intelligence is the common characteristic of all forms of self- 15.39.2.5. MOTIVES 125 The World of values gives rise to our motivations—we have a 15.39.2.6. HISTORY 125 The importance of selective memory—our stake in the I5.39.2.7. THE NON-RATIONAL WORLD 126 The irreducible non-rational element in our experience— 15.39.3. THE Ambiguity of Human Nature 127 The dyad of man's involvement both in Fact and Value — 15.39.4. Man as Triad 130 Function, Being and Will as distinct but inseparable aspects |

|

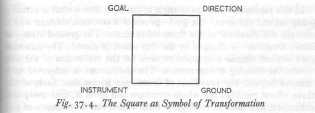

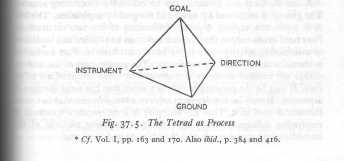

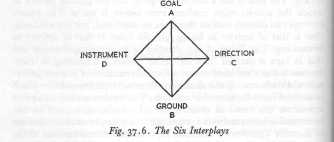

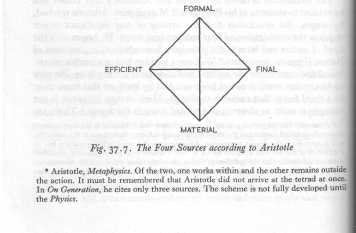

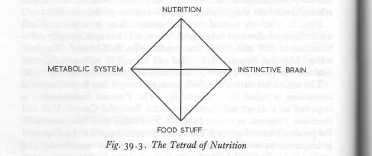

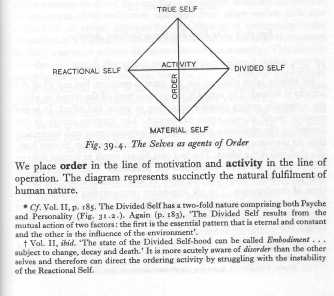

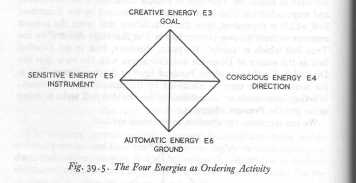

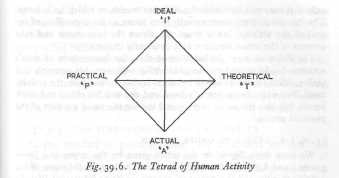

15.39.4.1. THE ELEMENT OF BEING 130 Experience as a present moment—characteristics—mind is 15.39.4.2. THE ELEMENT OF FUNCTION 132 Functions can be independent of mind—material, vital and 15.39.4.3. THE ELEMENT OF WILL 134 Everything has a fragment of Will—the many 'I's' in Man — 15.39.5. Man as Ordering Agent 135 Ordering in life, activity and mind—the tetrad—the activity 15.39.5.1. the four sources of The sources as Actual, Ideal, Theoretical and Practical — 15.39.5.2. LEVELS OF ORDER IN MAN 140 Three levels of the tetrad—the importance of the separation of |

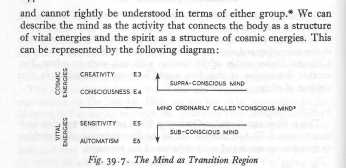

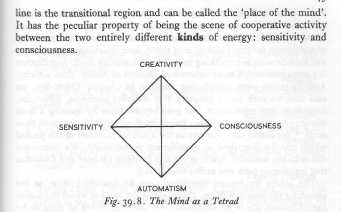

|

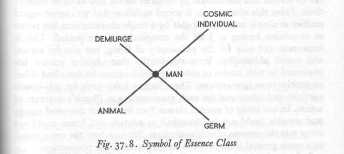

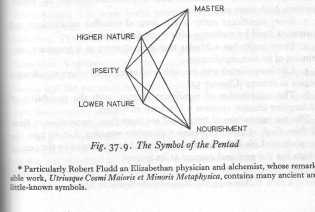

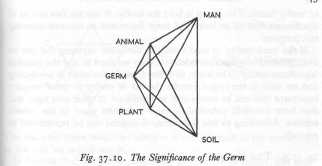

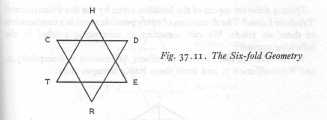

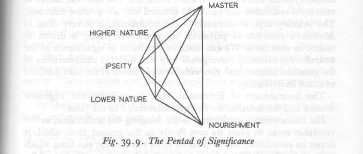

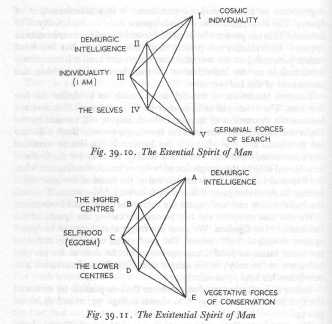

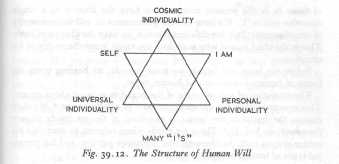

15.39.5.3. THE structure of HUMAN ACTIVITY 141 The region practical-theoretical—rules for right action— 15.39.5.4. THE MIND AS ORDERING ACTIVITY 143 Test of the scheme—mind is an activity involving vital and 15.39.6. The Human Spirit 145 The localization of significance—significance as an attribute 15.39.6.1. THE NOURISHMENT 148 The nourishment of essential man is given by the germinal 15.39.6.2. THE HIGHER AND LOWER NATURES 149 Demiurgic Intelligence and the functional powers as the 15.39.6.3. THE MASTER 149 The Master of essential man is the Cosmic Individuality— 15.39.6.4. IPSEITY 151 The longing of man is different from that of plants and |

|

turn this need into destructive egoism—the Ipseity of 15.39.7. Will as Coalescent Agent 155 Will as the principle of relatedness—essential and existential 15.39.7.1. MAN AS A PERSON 158 15.39.7.2. MAN AS A MEMBER OF SOCIETY 158 The feelings are the driving force—manifestation in sensa- 15.39.7.3. MAN AS GOVERNOR 159 15.39.7.4. MAN AS FREE AGENT 159 15.39.7.5. MAN AS CREATOR 159 15.39.7.6. MAN AS EVOLVING SELF 160 The concentration of energy—personal evolution—coale- 15.39.8. A Structural Anthropology 160 The scheme for a total anthropology summarized. |

|

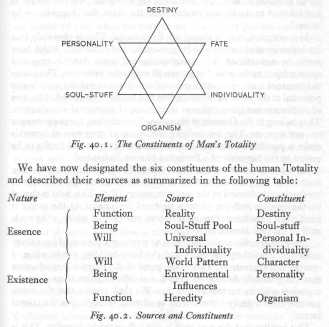

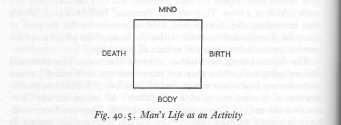

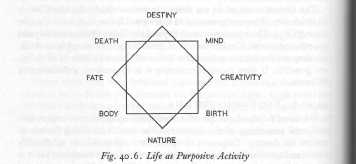

Chapter 40. the human life cycle 164 Between the coalescence of diverse elements at conception and 15.40.2. The Sources of Man's Totality 165 A man's life is dramatic—the 'Totality' of a man—at con- 15.40.2.1. ESSENTIAL FUNCTION 166 The pattern of action to be fulfilled—individual destiny and 15.4O.2.2. ESSENTIAL BEING 167 The soul-stuff at conception—it is drawn in as a complex 15.4O.2.3. ESSENTIAL WILL 167 The self-limitations of the Supreme Will—Personal In- 15.40.2.4. EXISTENTIAL FUNCTION 168 15.40.2.5. EXISTENTIAL BEING 168 I5.4O.2.6. EXISTENTIAL WILL 168 Fate arising from the World Pattern—hexad and table of the 15.40.3. Conception, Gestation and Birth 169 At any moment a man is only a fragment of his totality—the |

|

factors in children resulting from the state of the parents — 15.40.4. The Formative Years 176 The preliminary to soul formation is the development of |

|

15.40.4.1. EXISTENTIAL FUNCTION— Balanced development of the powers—health—graded 15.40.4.2. EXISTENTIAL BEING— Nothing more than what is required for life —skills of com- 15.40.4.3. EXISTENTIAL WILL 183 The right development of the four selves—avoidance of 15.40.4.4. THE ESSENTIAL NATURE 184 No direct intervention is necessary and could be harmful — 15.40.5. The Meaning and Nature of The three-fold task of man—the care of the organism—the |

|

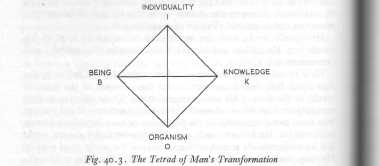

of Life—the nature of 'his' identity—blindness to egoism- 15.40.5.1. THE ORGANISM 190 The field of transformation—the limited development of the 15.40.5.2. KNOWLEDGE 191 The transition from external knowledge to the supreme 15.40.5.3. BEING 191 The two main components of the soul-stuff give rise to two 15.4O.5.4. INDIVIDUALITY 197 Will cannot change itself—it manifests in relationship — |

|

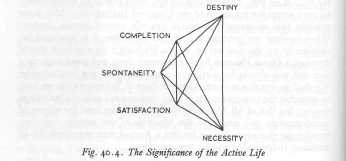

the unpleasant manifestations of others—self-naughting and 15.40.6. The Active Life 207 The pattern of significant life on reaching responsible age — 15.40.6.1. NECESSITY 208 15.40.6.2. SATISFACTION 209 15.4O.6.3. SPONTANEITY 210 The freedom of 'I' and its many forms —humour —purity 15.40.6.4. COMPLETION 210 15.4O.6.5. DESTINY 211 Some task concerned with the conscious Evolution of 15.4O.6.6. THE STAGES OF LIFE 211 Between 24 and 32 a man gets to know the world—33 to 40 |

|

15.40.7. OLD Age 212 After the grand climacteric the influence of Fate diminishes 15.40.8. Death and Beyond 216 The first and second deaths —the significance of death 15.40.8.1. LOST SOULS 220 15.40.8.2. NULL-SOULS 220 15.40.8.3. HALF-SOULS 220 During life, they have not worked on themselves —there 15.40.8.4. PURGATORY 222 With any organization of consciousness the Individuality |

|

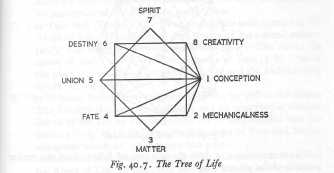

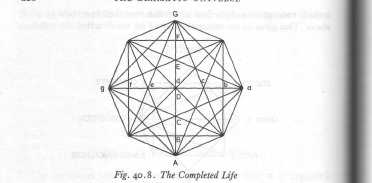

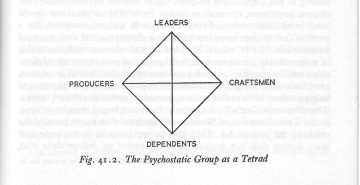

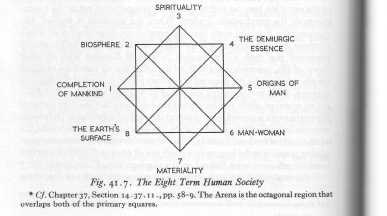

15.40.8.5. HARMONY 224 15.40.9. The Completed Life 225 The octad enables us to grasp the complete picture—the 15.40.9.1. THE SEVENFOLDNESS OF 15.40.9.2. THE CYCLE OF LIFE 227 15.40.9.3. THE CYCLE OF THE PERSON 228 The spectrum from the Material Self to the Cosmic In- Chapter 41. human societies 230 The organized complexity of experience—limitations of 15.41.2. The Idea of a Total Society of Mankind 233 Until recently there has been no conception of a total society 15.41.3. The Psychostatic Group 235 The tetrad of four sub-groups—the motivational terms — |

|

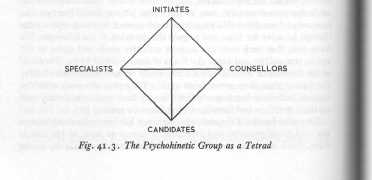

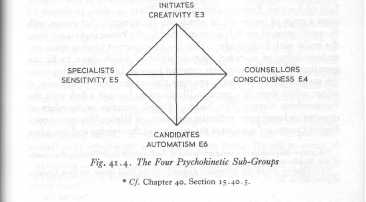

15.41.3.1. DEPENDENTS 236 Those who cannot care for themselves—lack of care results 15.41.3.2. PRODUCERS 237 Those concerned with action in the material world—auto- 15.41.3.3. CRAFTSMEN 239 The organization of external activity requires educated 15.41.3.4. LEADERS 240 Those with initiative—possibilities of entering the Psycho- 15.41.4. The Psychokinetic Group 242 Transition to the Psychokinetic Group when the inner |

|

15.41.4.1. CANDIDATES 245 15.41.4.1.1. OBJECTIVE MORALITY 247 The gradually refined consensus on right and wrong action 15.41.4.1.2. ACCELERATED TRANSFORMATION 248 Special disciplines and methods believed to accelerate ful- 15.41.4.1.3. THE FUNCTIONAL APPROACH 248 Ways of life corresponding to the dominant level of self- 15.41.4.1.4. THE BEING APPROACH 249 The aim of soul formation —awareness of sinfulness and 15.41.4.1.5. THE WILL APPROACH 250 Action based on understanding—Work —danger of lack of 15.41.4.1.6. GUIDANCE 252 Summary of characteristics of Candidates—the complexity |

|

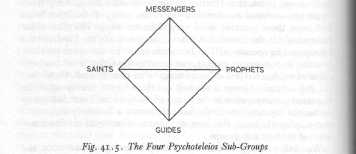

15.41.4.2. specialists 253 The need for Psychokinetic Specialists — Specialists are not 15.41.4.3. COUNSELLORS 256 Concern with objective needs of the work —freedom from 15.41.4.4. INITIATES 258 They are free of egoism but not yet Individuals —distinc- 15.41.4.5. CO-OPERATION IN THE The need for an integrated activity of the four sub-groups — 15.41.5. The Psychoteleios Group 262 Each group has a different kind of unity —the Psychoteleios |

|

communication, powers and unity — Psychostatic man and 15.41.5.1. GUIDES 266 They can act rightly in all situations—their significance 15.41.5.2. SAINTS 268 They belong to World XII—the miraculous—the Saint is 15.41.5.3. PROPHETS 269 Infusion of the Universal Individuality into a human soul — 15.41.5.4. MESSENGERS 272 Representations of the Cosmic Individuality —expressions |

|

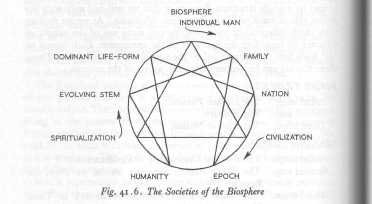

15.41.6. Societies as Energy Concentrations 274 Societies as apparatuses for the transformation of energies 15.41.7. The Biosphere as Symbiosis 276 Human society participates in the Biospheric symbiosis — 15.41.7.1. THE FAMILY 279 The basis and extent of family society—it is the natural 15.41.7.2. NATIONAL SOCIETIES 280 The bonds of a nation arise from those of the family—the 15.41.7.3. CIVILIZATIONS 281 Their embrace and mode of existence is quite different to 15.41.7.4. EPOCHS 283 Their existential and essential environments —stages in the 15.41.7.5. HUMANITY 283 The human totality of a major cycle of transformation — |

|

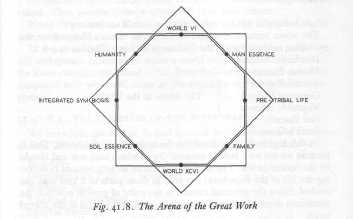

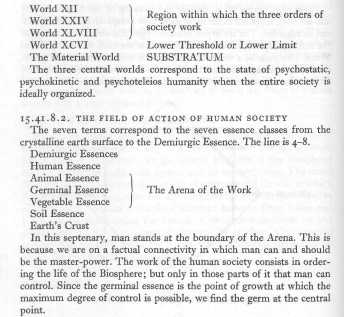

I5.41.7.6. SPIRITUALIZATION 284 Notions of Chapter 35 — the society of psychoteleios men and 15.41.7.7. EVOLVING STEM 284 15.41.7.8. DOMINANT LIFE-FORM OF The essential significance of the Biosphere—man's lack of 15.41.8. The Completed Structure 286 The Octad—the Arena of the Great Work—interpretation 15.41.8.1. HUMANITY AND THE WILL 287 15.41.8.2. THE FIELD OF ACTION OF 15.41.8.3. DEVELOPMENT OF HUMANITY 288 15.41.8.4. THE SOCIETIES OF THE BIOSPHERE 289 15.41.8.5. CONCLUSION 289 The relevance of the scheme to history—the dramatic in- Glossary 291 |

FOURTH BOOK

SYSTEMATICS OF HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Part Fourteen

SYSTEMS

Chapter Thirty-seven

THE STRUCTURE OF THE WORLD

14.37.1. Organized Complexity

An outstanding characteristic of our time is the rapid growth of our

knowledge of the world we live in. The more we learn, the more we

become aware of its endless complexity. A drop of water contains a

million, million atoms and each of these atoms is an intricate array of

sub-atomic particles and waves. The Milky Way, which to the naked

eye consists of a few thousand stars, reveals itself to the modern tele-

scope as more than a hundred thousand million stars as great as our

sun, clouds of dust and atoms beyond all counting, and electro-magnetic

and radiation fields of extreme complexity. The proteins and nucleic

acids which build our bodies are molecules of such marvellous intricate

patterns as to make notions of an earlier generation of chemists appear

like kindergarten stuff. The greater the complexity, the stronger also

the evidence that this world is no chaos of atoms in random motion,

but a highly organized, integrated structure. We have grown out of the

atomism of the nineteenth century, without half realizing the implica-

tions of our new mental horizons.

For more than a hundred generations, speculations about the nature

of Reality and the scientific, practical and social activity of mankind have

been dominated by the conviction that truth must be simple; and that,

when seen, it cannot fail to be accepted. Thus, the Greeks saw that the

sphere was the simplest figure and concluded that it must be the most

perfect and hence that the heavenly bodies must move in spheres. For

nearly twenty centuries, this assumption paralysed astronomy until

Kepler demonstrated that the less 'simple' elliptical orbit was nearer the

truth. Celestial Mechanics by the time of Laplace had already lost all

its hoped-for simplicity; but the belief in simplicity was far too deeply

rooted to be abandoned and, in the principle of stationary action,

mathematicians of the early nineteenth century believed that they had

found a simple and ultimate law that governs all free motions and could

apply to all that exists. Today, the laws of motion—renamed General

Field Theory — are seen to be so complicated and are formulated in

such abstruse terms that only a handful of mathematicians profess to

understand them.

The early Greek philosophers pictured the atoms as simple, homo-

geneous, indestructible particles differing only in shape and size. Belief

in the simplicity of the atoms gave way as late as the present century.

Now, we have a profusion of sub-atomic particles, waves and quanta and

quite unintelligible notions that prevail only because they have proved

useful in practice. Complexity has routed simplicity and truth in physics

is anything in the world but self-evident.

Aristotle set up a system of nature which offered a simple account of

all that was known about the world. Today sciences have so proliferated

that no one even knows the main outlines of all of them—let alone their

detailed and evergrowing content.

One might have expected that scientists and philosophers everywhere

would, by now, have agreed to replace the doctrine of simplicity, by one

of the limitless diversity and complexity of the natural order. The reason

why this has not happened is probably two-fold. On the one hand, it

looks like a confession of failure, an admission that the task of under-

standing the world is beyond us. On the other hand, general laws are

being discovered that seem to hold promise of bringing all the diversity

into some kind of universal order which, if not simple, will at least be

within the power of man to grasp. Such modes of thought are relics of

the past and fail to take account of the truly overwhelming complexity

of the world we are beginning to explore. The confidence that we feel

in the scientific method is no longer based upon well-established

universal laws—note that almost every such law that a hundred years

ago appeared secure forever has since proved seriously defective—but

rather upon the unexpressed conviction that, behind the bewildering

diversity and complexity of phenomena, there is an organized structure

that holds them all together.

This conviction is shared by tens of thousands of scientists who

would indignantly repudiate any interest in understanding the world as a

whole. Scientists not only specialize, but take pride in narrowing their

field of research in order to deal with it successfully. The method has

produced such marvellous results that it seems to justify the philo-

sophical outlook that rejects as 'metaphysics' the search for total

explanations; and yet the method itself could not succeed if there were

not an organized structure that connects each specialized part to the

whole and also to every other part, and, especially, to the scientist

himself.

In the main field of practical application of the results of science,

that is in industrial technology, the importance of organization and

structure is self-evident. In the most advanced industrial countries,

more and more attention is being paid to the theory of structures and

less and less to the search for universal laws. The same is true in the

field of economics and politics. The processes of modern life are bring-

ing about changes that are practical and realistic, rather than theoretical

and philosophical. One consequence of this is that our modes of thought

and expression lag behind our practical activity. We act structurally,

but we continue to think and to speak analytically and even atomically.

One of the tasks we set ourselves in Vol. I, was to seek for modes of

expression that would enable us to see and think in terms of wholeness

and structure rather than of atoms and laws. We saw that this meant

going beyond the dualistic language and logic that are our Indo-

European heritage. The notion of multi-term systems enabled us to

attempt a reformation of language, and in this we were helped by the

realization that it was necessary to break through the limitations of time

and space. In the present volume, we must carry our task further in

order to make a synthesis of the notions given by the several systems

separately. In doing so, we shall find structures common to man and

the world and finally interpret them in history. Man is an organized

complex, so is the world and so is its self-realization in history.

14.37.2. Structures and Systems

It is no accident that recognition of the importance of structure has

come, not by way of speculative philosophy or logical reasoning, but

by the pressure of practical needs. We apprehend structures far more by

the power of understanding than by knowledge. Knowledge is confined

to Fact.*

The Domain of Fact does not include transformation, which belongs

to the Domain of Harmony. In this sense, knowing and understanding

are powers that belong to quite different regions of experience and this

suggests the surprising, but correct, conclusion that structures are not

objects of knowledge, and that their true place is in the Domain of

Harmony. We do not know structures, but we know because of struc-

tures.

Facts, that are no more than facts, are atomic and unrelated except

by general laws. That is how the world was studied until the middle of

the present century. Darwin's Origin of Species (1859) and Clark

Maxwell's Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism (1873) were magnificent

swan-songs of a dying age of science when it had seemed possible to

[* Cf. Vol. I., p. 63, and chapter 5. Vol. II, pp. 21-23: 'What we know as Fact is the

process of the universe governed by laws.']

explain the whole by the part and to account for the facts, without

regard to the purposive action that makes them possible.

We are now in the midst of a mental revolution, and as with all

revolutions, its true significance escapes those most deeply involved.

We are being forced to look at every kind of problem in a new way;

that is, in terms of structures rather than of general laws. Scientists

and philosophers are not alone in fighting a rearguard action against the

revolution. In every department of human life, the ancient strongholds

are being surrendered reluctantly and usually after they have ceased to

matter. Men pay lip service to doctrines of 'integration', 'unification',

'oecumenism' and to the proposition that excessive specialization has

become a menace to society; but, in practice, the changes come before

the people concerned consent and usually before they realize what is

happening.

We are thus in a stage of confusion due to the inadequacy of our

modes of thought. We continue to think in terms of atomic concepts

linked by logical implications and empirical laws. This approach can

never lead to the understanding of structures whose significance lies

in their organized complexity, not in their susceptibility to destructive

analysis into elements and laws. We have seen in the earlier chapters,

that understanding is the subjective aspect of will and knowledge is

the subjective aspect of function.* We can 'know' structures only in

their functional properties; whereas we 'understand' them in their

working. This working is very much more than actualization in time,

for it concerns what things are and not simply how they change.

Structures link Fact and Value, and they are consequently always

interesting. The elements of structures in isolation or connected by

general laws are only shadows of reality and there is always a step to be

made in order to pass from knowing about them to becoming aware of

the structures in themselves. The problems of knowledge—how we

know, what we know, what knowing is—all arise because of the in-

herent incompleteness of any possible knowledge. No such problems

arise in understanding structures. This is not to suggest that under-

standing is easier than knowing; but that the difficulties in the way of

understanding are of an altogether different kind. We understand by a

mental act that is synthetic and creative; whereas we know by an act

that is analytic and automatic. These mental acts must be projected

into the mind and the mind must be able to experience them sensitively

[* Cf. Vol. I, pp. 62-4. Knowledge was defined as the ordering of function. Ordering

is an operation performed upon the data whereas understanding is a transformation

within the data.]

as images and consciously as judgments.* Some degree of understanding

must always be present for effectual action in the world. It follows that

understanding understanding is of great practical importance; but there

has been little research into the nature of understanding and into the

possibility of developing it, until the growth of complex organizations

has in recent years forced it upon the attention of practical men. It

continues to be neglected by philosophers.

The need for more understanding is not confined to organization

theory and systems engineering. It lies at the root of our central problem

of elucidating the nature and destiny of man. We have not neglected the

task in the earlier volumes of the present work. The first indications of a

technique of understanding came with the notion of multi-term

systems introduced in Vol. I and developed further in Vol. II.+ The

theory of eternal patterns is a projection in analytical terms of a way of

looking at complex structures that cannot be reduced to functional

terms.++

A common characteristic of these varied techniques is the recognition

that structure is a primary element of experience and not something that

is added by the mind. In this respect, it can be said that the techniques

of understanding call for a drastic revision of the usual modes of

thought that treat being and understanding as independent or at least

as separable from one another.

In the study of structures, we cannot separate what we understand

from what we are, nor can we separate what a thing is from the way it is

known. Since no human mind has a synthetic and creative power great

enough to reproduce as a mental image the total organized complexity

of the world presented to us from moment to moment we need a

means of simplifying the task. This is provided by Systematics.

Systematics is the study of structures as simplified totalities. Analytics

breaks structures down into their simplest elements and looks for the

connections between these elements. Systematics takes the connections

is primary and the elements as secondary.§ This is a very difficult

* The four energies involved; automatic, sensitive, conscious and creative are de-

scribed in Vol. II, Chapter 32 and in greater detail in J. G. Bennett's Energies, Material,

Vital and Cosmic, London, 1962. The 'mind' of man is discussed in Chapter 39 below

and the history of mind is the main theme of Chapters 45-48.

+ Cf. Vol. I, Chapter I, pp. 26-28, and Vol. II, Introduction, pp. 3-10.

++ Cf. Vol. I, p. 10, the connection between Knowing and Being and also the

notion of the organism, p. 381.

§ This discipline has been developed in recent years by the author and his co-workers

at the Institute for the Comparative Study of History, Philosophy and the Sciences.

The quarterly journal SYSTEMATICS, which began publication in 1963, is devoted

to this discipline and its practical applications.]

mental exercise for people trained in analytical thinking; but it is

beginning to make its way into several fields. We shall in the present

chapter, develop the systematic approach as far as is needed for our

subsequent studies.

For convenience, we shall state some of our earlier conclusions.*

1. A system is a set of independent but mutually relevant terms.

The relevance of the terms requires them to be compatible. No one

term of a system can be understood without reference to all the others.

2. The order of a system is given by the number of terms. A system

of the first order, or one-term system, is called a monad. Second,

third, fourth, etc. order systems are called dyads, triads, tetrads, etc.

3. In systems, there are no fixed meanings attributable to the terms,

which depend upon the structure of the system as a whole, so the various

connectivities are common to all systems of the same order.

4. Every system exemplifies modes of connectedness that are typical

of the number of terms. Thus there are zero connectivities in a monad,

one in a dyad, three in a triad, six in a tetrad, ten in a pentad, fifteen in

a hexad and 1/2n (n— 1) in an n-term system. If the connectivities are

distinguished according to direction, the number is doubled. All the

connectivities are significant and must be taken into account if the

structure represented by the system is to be understood.

5. Each order of system is associated with a particular mode of

experiencing the world, called the Systemic Attribute.

The Monad gives totality—without distinction of parts, hence

universality as the systemic attribute.

The Dyad gives difference without degrees, hence complementar-

ity

The Triad gives relatedness without relativity and hence dynamism

as distinct from force.

The Tetrad gives structured activity and combines relativity and

order, and hence activity as distinct from potential.

The Pentad gives significance both inner and outer: hence also

potentiality as distinct from actual occurrences. Here entities make

their first appearance in the scheme of understanding.

The Hexad gives structure capable of transformation without loss of

identity, hence recurrence and the character of events and so the his-

torical character of experience. The systemic attribute is called

coalescence.

The Heptad gives completeness combined with distinctions of

quality: hence transformation.

[* Most of the references are to Vol. II Introduction.]

The Octad gives the property whereby a structure can be understood

in and for itself without reference to other structures, hence completed-

ness.

The higher systems have further complexities and attributes.

6. The mutual relevance of all the terms of a system requires that

they should be of the same logical type and make contributions to the

systemic attribute of one and the same kind. This we shall indicate by

a common designation. Thus the terms of a dyad will be called its

poles, those of a triad, its impulses, those of a tetrad its sources and

so on.

7. The independence of the terms of a system requires that each

should have a distinctive character. An important part of the study of

systems consists in identifying the term characters of systems of a

given order. The general characters common to all systems are to be

further specified in respect of the particular system under review.

8. The mutual relevance of terms of a complex system can be found,

to a first approximation, by taking all the terms in pairs. These are called

the first-order connectivities. In a dyad there will be one, in a triad

three, in a tetrad six and in an n-term system 1/2 n (n— 1) first order

connectivities. Connectivities of a higher order can be studied as sub-

systems from the tetrad onwards. This procedure is adopted whenever

circumstances require it.*

These brief descriptions will be amplified later. We must, however,

draw attention here to a defect in the presentation of Systematics in the

earlier volumes. We failed to show the connection between systems and

structures as we now see to be both necessary and possible. We took

the notion of systems to be primary and that of structures derivative.

This was a mistaken view. The organized complexity of the world

resides in the structures that we discover both in our perceptions and in

our mental processes. Whereas in knowing the world, we have to

introduce signs and symbols to connect the mental picture with the

perception; in understanding, the connection is common to the mind

and its objects. The division into elements and laws, or 'things' and their

'behaviour' destroys the structure that must be built up again by a

mental process. When we look at structures with the help of systematic

forms, we retain the coherence and so no 'rebuilding' is needed.

We can describe systems as the forms of structure, but no one

system taken alone can exemplify the organized complexity of real

structures. We usually need to take more than one system into account

[* We shall find an example in the next chapter in the scheme of values where the main

system is a dodecad, but can best be studied as four triads, three tetrads or two hexads.]

in order to gain the insights needed for understanding any existing

structure that we find. According to the aspect of structure that happens

to be relevant to a given purpose, a system of one order may be more

useful than another. It has been found that for purposes of practical

utility, the systems fall naturally in groups of four. The first four from

the monad to the tetrad help us to see how structures work. The

systems from pentad to octad show why they work and how they enter

into the pattern of Reality. The third group from the ennead to the

dodecad is mainly concerned with the harmony of structures: that is,

the conditions that enable them to fulfil their destined purpose.

For many purposes, we can understand what is needed by consider-

ing only the first four systems in a given structure. When we need to

understand what the structure is, why it exists and what it is intended

for, we must take higher systems into account.

Structures that are in process of transformation lead into societies

and communities which are more concrete than structures and usually

too complex to be described in terms of systems alone.*

14.37.3. The Properties of Systems

The series of multi-term systems is a progression such that each

system implies all the earlier ones and requires those that follow. We

cannot understand the triad unless we already grasp the notions of

universality and complementarity and the dynamism of the triad is not

realized without the activity of the tetrad.

The later systems are not only more complex and more highly

organized than the earlier ones; they embody an understanding of

reality that is more comprehensive and practical. The progression is

from abstractness towards concreteness. The monad which defines a

structure, but tells us nothing about it, is more abstract than the dyad

which enables us to see how the polarity of the structure is formed.

Polarity is a less concrete attribute than dynamism. Only with the

pentad do we reach a degree of concreteness that allows us to define an

entity. This, incidentally, illustrates the difference between knowing

and understanding. For knowledge, entities appear to be simple notions.

Things, beings, societies are entities that we know by their names;

but this does not mean that we understand what they are, why they are

or how they are. As we shall see in a later section, the five terms of the

pentad are needed to give substance to the notion of an entity. Again,

we have in all concrete situations uncertainties, hazards and varying

degrees of success in surmounting them. Such situations cannot be

[* This will be elaborated in Chapter 41.]

adequately, that is concretely, investigated without reference to nine-

term systems.

We have, then, a progress from abstract to concrete that is expressed

in the systemic attributes. Not all structures exemplify all stages of the

progression to the same degree. A given structure may exemplify one

attribute strongly and others weakly. Thus we may have a structure

that can be understood very well as an activity (tetrad), but not so well

as a coalescence (hexad). We should call such a structure weak in the

hexad and strong in the tetrad.

The use of the expressions 'weak' and 'strong' is intended to convey

the connection between understanding and will. A structure that fails

to exemplify a system can be regarded as lacking in the will to exemplify

it. An act of decision is needed to bring together the terms of a tetrad

so as to produce and maintain a specific activity. Again, significance is

not a quality that belongs to the experience of one who studies an

activity, nor is it inherent in activity as such. In order to be significant

there must be a decisive concentration of purpose at a central point.

By this decision, the activity acquires meaning in its own right and so

becomes an 'entity'. By another act of will, the entity asserts its own

independent reality and so becomes strong in the hexad.

One other general property of systems remains to be considered. This

we shall refer to as term-adequacy. If the terms of a system cannot be

clearly discerned in a given structure, the required characters will be

lacking and the system in question is then inadequately represented. To

illustrate the point, let us take the three terms: father-mother-child.

It is easy to see that the father adequately represents the affirming im-

pulse, the mother the receptive and the child the reconciling. Compare

this with three terms: man-fish-tree. The terms very inadequately

represent the character of the triad. Only in an insignificant group of

situations, will the three elements exemplify the attribute of dynamism.

If, however, we add a fourth term, man-fish-stream-tree, we can pic-

ture an activity of a man fishing in the shade of a tree that is quite an

adequate tetrad. The motivational terms are represented by man and

fish and the instrumental terms by stream and tree. In this case the

tetrad must be strong in order to exemplify its attribute. The man must

have the will to catch the fish and the fish the will to stay in the water.

We have these three conditions to fulfil in order to have a well-

defined system associated with a structure:

1. The structure must exemplify the systemic attribute.

2. The term characterization must be adequate.

3. The system must be strongly willed.

We shall not further discuss the properties of systems in general, but

proceed to examine each member of the series in turn. In doing so, we

must remember that our purpose is to understand structures and that

systems are means to this end. The study of systems is useful only in so

far as it helps our understanding.

14.37.4. The Monad

We have defined the Universe of Existence as the sum of all possible

situations. In doing so, we imply that it is an organized complexity; for

without organization there would be no meaning to the word 'possible'

and, without complexity there could be no 'situations'. This universe,

as it presents itself to us in our immediate experience, is not separated

into subjective and objective realities, but simply is what it is. We can

express this by saying that the first stage in coming to terms with any

or all experience is to see the Universe as a Monad.

The monad is an undifferentiated diversity. We meet this satte of

affairs whenever we turn our attention to a new situation, large or small.

The monadic character of the universe as a totality, is present in all its

parts. Every such part appears in its immediacy as an undifferentiated

totality of which we know nothing except that it is what it is. But, side

by side with this bare knowledge, we are led on, by the conviction that

it is a structure, to hope to understand it by examining its content more

closely. This combination of confused immediacy and the expectation

of finding an organized structure gives the monad a progressive charac-

ter. It is what it is, but it holds promise of being more than it appears

to be.

This starting point is very important for the development of under-

standing. We shall call it the act of identifying the monad. The act

requires both cognition and judgment, that is Fact and Value, and so

takes us into the Domain of Harmony.* We do not yet know anything

clearly, but we can select a particular region out of the totality to be our

field of study, understanding and action. If the region is primarily

composed of mental images associated with words, we call it an 'uni-

verse of discourse'. If it is a class of objects, we call it a 'population'.

If it is a complex of energies, we call it a 'field'. If it is a situation re-

quiring action, we call it a 'problem'. Common to all of these descrip-

tive names is the property of challenging our capacity for understanding.

We shall use the following terminology:

[* As defined in Vol. II, Chapter 25.]

One-term System: MONAD

Systemic Attribute: UNIVERSALITY

Term Designation: TOTALITY

Term Character: DIVERSITY IN UNITY

The monad, as we understand it, is very different from the entities

of Leibniz' monadology which are simple and closed to one another.

Our monads are parts of the whole universe distinguished from the rest

by acts of attention or determination. Even the total Monad, which is

the Universe of Existence, is not isolated from Non-existence. The

possible and the impossible regions are not rigorously circumscribed, but

interpenetrate and interact at every point. Every situation is indefinitely

outlined and the indefiniteness is inseparable from the character of the

monad. The monad is not defined by a sharp impenetrable boundary—

either material or conceptual. It is unified by its total character.

Consider, as an example, a home: it is not precisely defined in extent,

in activity, in human occupants or material contents. All these are

liable to change and they can do so without 'breaking up the home'

providing the total character of 'homeliness' remains unimpaired. It is

an ill-defined yet structured whole. In appearance it is seen as a dwelling

occupying such a place at such a time, furnished in such a way, with a

family living in it comprised of such and such people. Its identity is not

confined to its own boundary: its influence upon the surrounding world

and its ever-changing activities are equally among the recurrent ele-

ments by which we recognize it and give it a name. But it is not a home

just because it is a collection of material objects and living beings. The

unity in diversity that characterizes it is the 'reality' of the home. To

understand a home we must take this totality into our attention. This

establishes the monad.

The appearance of the monad must be distinguished from the content

of the structure. The home as a structure is more than a monad. It has

a form that comprises several systems and its content depends upon the

degree of coherence and harmony with which the appearances agree

with the form.

It might seem from this that we find the monad through the appear-

ance, and not through the reality, of the structure. In a sense, this is

true and must always be so. The appearance is given to us by a process

that is almost automatic. The recurrent elements which go to comprise

it are there in us and in the situation itself. Almost always, they are our

first contact with the structure. But this does not mean that the monad

is no more than the sum of the appearances. We can use the word

'intuition' to distinguish the perception of structures from 'knowledge'

of appearances. There is a necessary intuitive step involved in establish-

ing any monad. This consists in recognizing the object as a significant

whole that can be understood for what it is and not only for what it

appears to be.

How then are monads to be recognized? In many cases, evident

wholeness is a sufficient indication. The example of a home suggests

others of the same kind. Coherent structures whether natural or man-

made can be monads—though sometimes they are so weak in content

as to give little material for understanding. A man and every other living

organism is a monad. So are celestial bodies such as planets, solar

systems, galaxies, up to and including the Universe as a whole. All these

examples have in common the property of being aggregates of matter

and energy—in other words, they 'exist' in the ordinary sense of the

word. As we extended* the concept of energy to include vital and

cosmic energies, and as matter can always be regarded as a state of

energy we can accept as monads intangible, yet existing, wholes such as

mental constructions, theories, modes of thought, providing these are

found actually present in the form of patterns of energy and activity

interacting with the rest of the world. An idea cannot be a monad unless

it is associated with some situation actually existing in time and

space.

An alternative test for monads is to look for the possibility of an act

of understanding. If we hold that only structures can be understood (not

recurrent elements) and if we must always approach understanding

through the monad, we are forced to conclude that nothing can be

understood unless it exists. This does not agree with the ordinary use

of language, for we speak of understanding abstract ideas, theories,

states of mind, without necessarily implying that they 'exist' somewhere.

On careful reflection, we can satisfy ourselves that to grasp the meaning

of an abstract idea does not amount to an act of understanding. We begin

to understand only when we can see this idea in a concrete situation—

in other words when it becomes a monad.

To understand is an act of the will. It cannot be made in the void,

out of contact with things as they are. It cannot even be made in the

semi-void of recurrent elements where we are in contact only with the

appearances of things. This is one reason why we have to distinguish

systems from generalizations that can be studied and known in the

abstract. In grasping a monad, an act is required that goes beyond

knowing. This act makes a connection between two real structures—

[* Cf., Vol. II, Chapter 32.]

one is the understanding monad with the will to understand and the

other is the presented monad with its will to be understood. The act,

and nothing else, cuts through the barrier of subjectivism which

prevents us from knowing whether anything exists or has existed

except our own momentary state of mind. The distinction we have made

between knowing and understanding is so alien to views that are held

without question, that its importance can easily be disregarded. In

metaphysics, it has been customary for centuries to distinguish between

epistemology, the study of knowing, and ontology, the study of being.

This division leaves out of account the study of willing, and it totally

disregards the obvious fact of experience that our degree of connected-

ness or relatedness with other objects depends upon an act of will, and

not upon the interpretation of recurrent elements that gives us know-

ledge of or about them—or, upon our intuitions of being.

The study of Systematics is, therefore, as much a training of the will

as of the powers of perception and thought. It does not add to our

knowledge, but it develops our power of understanding. It starts with

the act, already discussed, of selecting the field or establishing the

monad. This act takes us into the Domain of Harmony where Fact and

Value lose their distinctive character in order to become a 'new

reality'.

The indefiniteness of the monad is relative. It can be made to con-

verge towards definition in two ways. One is to prescribe its content and

the other to specify what it excludes. One method says: 'this, and this

and this. . . .' The other says: 'Not that, nor that, nor that. . . .' Neither

method selects the monad itself: for this is done by fixing attention

upon its specific character, as we did just now in describing the monad

"home'. The selection of the monad is primary; enumeration of contents

and exclusions are secondary. The method of enumeration tends to

reduce the monad to the status of fact. That of exclusion tends to make

it the object of a value judgment. Nevertheless, both methods are

necessary in order to see what is relevant to the situation we seek to

understand. We can usually distinguish relevant from irrelevant ele-

ments in terms of scale. For example, in establishing the monad of the

human body we should take account of the limbs and organs and func-

tions that are relevant for the body as a whole. We should not break

these down into processes, tissues, cells, chemical complexes, atoms,

fields, for these subordinate constituents belong to subordinate monads.

Even so, the task can seldom be accomplished satisfactorily. The

alternative method consists in examining the points of contact between

the monad and its environment. This is called 'seeing it in its various

worlds'.* Returning to the example of the human body, we can say that

it belongs to the worlds of material objects, of living organisms, of

sentient beings, of man, of space and time and a few others. All these

worlds contribute something to the significance of the monad and to the

possibility of understanding it.

These two methods lead to an inner and outer approximation of the

monad. They can give us nothing to work on unless we recognize the

character that unifies the situation.

Any situation to which we direct our attention is a monad, but some

exemplify the systemic attribute of universality more strongly than

others. The strongest monads are those whose complex organization is

unmistakable. Such outstanding structures are often called cosmoses.

In this sense, we refer to man as a microcosm+ and the universe as the

macrocosm. The adequacy of a monad turns upon the combination of

diversity and unity. Neither alone give the true character of the one-

term system. It will be evident that the identification of monads that are

both strong and adequate is an important step towards understanding

ourselves and the world.

14.37.5. The Dyad

The two ways of developing the monad disclose an ambiguity.

Although ideally they might lead to the same result, in practice this

can never happen for it would be impossible to carry either procedure

far enough. Since understanding is a matter of the will and therefore

nothing if not practical, we have to conclude that no monad can ever be

completely established. The difficulty is not one of approximation, as,

for example, we can know the square root of two in numerical terms to

any degree of accuracy we wish. The two procedures converge but do

not coincide except at the limit when everything has been taken into

account. Hence, the aphorism: 'To understand anything one must

know everything'. For practical purposes, we arrive at two opposite

views of the situation according to whether we are looking inward or

outward. Knowledge of what A is not is usually very different from

knowledge of what A is.

The ambiguity lies, not in the limitation of our power to grasp any

given situation, but in the very nature of things. The word universality

[* This technique is applied in some detail to the anthropological monad Man in

chapter 39 below.

+ Cf. Hallam Hist. Lit. quoted N.E.D. 'The doctrine of a constant analogy between

universal nature, or the macrocosm, and that of man or the microcosm.' Cf. also

Disraeli Vivian Grey 'the microcosm of a public school'.]

which we take as the attribute of the monad, and interpret as unity in

diversity, conceals a contradiction. Every monad is a contradiction,

for it presents itself with a claim to self-sufficiency and yet depends

upon everything other than itself in order to be itself.

If we go back a stage, and consider the nature of structures, we find

that the contradiction is at the very root of understanding. Every

structure has a two-fold nature: one nature makes it what it is and the

other what it does. What it is, that is the content, is its own affair;

but what it does concerns everything around it. There is no end to the

repercussions of the smallest act—even the splitting of an atom. Every

monad—being the form of a structure—bears within it the two-fold

significance of its source. It is infinite in its external connectedness, and

it is also infinite in its internal diversity. The two infinities are not the

same. They even contradict one another. The inner significance comes

from separation from the rest of the world and the outer from contact

with it. This can easily be seen in any actual monad: for example, a

home. We even go so far as to say that there are always two homes: the

mother's which draws in and the father's which reaches out. And yet

both homes are the same home—that is the same monad.

Such considerations point to the suggestion that understanding

cannot stop at grasping the monad: it must go on to face the dyad. By

definition, a dyad is a two-term system, such that each term is distinct

from and yet requires, and even pre-supposes, the other. Its character

is well expressed in one of Gurdjieff's favourite sayings: 'Every stick

has two ends.' The contradiction inherent in the dyad is the foundation

of Hegel's Logic, though he did not seem to recognize that the con-

tradiction is not removed by the dialectic without destroying the situa-

tion we are trying to understand.

The word complementarity admirably expresses the character of

the dyad. The two ends of a stick are complementary: one to hold and

one to take the weight. The two aspects of a home are complementary.

When we transfer complementarity from structures like sticks and

homes to systems, we have to find ways of describing the two terms of

the dyad in such a way as to bring out the connection between contra-

diction and complementarity without restricting it to the notions of

'inner' and 'outer' which are not sufficiently general.

It would seem that the most obvious complementaries—male and

female—are also the most appropriate. Man-woman is the dyad that

emerges from the monad, man. The ancient wisdom of China called the

two principles Yang and Yin; and, upon this dyad, based a technique

for understanding that has been in use for at least three thousand years.

This is contained in the so-called Book of Changes, the I Ching. For

the sake of generality, however, we will adopt more neutral terms.

The terminology of the Dyad will be as follows:

Two-term System: DYAD

Systemic Attribute: COMPLEMENTARITY

Term Designation: POLES

Term Characters: POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE

Connectivity of terms: FORCE

From time to time, the two terms of the dyad have been interpreted

subjectively as right and wrong, good and evil. This has been the cause

of much confusion. There are certainly distinctions that justify the use

of the words good and evil, but they do not form a dyad. Good and evil

are not complementary, that is necessary to one another, in spite of the

widespread belief that this is so. One consequence of this Manichaean

error can be seen in the societies that have been based on it, namely,

the relegation of women to an inferior place as the 'evil' side of human

nature. This is a typical example of the mistake of confusing knowledge

with understanding. The dyad can neither be broken into two parts

nor can its contradiction be resolved. If we break a stick in two, we still

have two ends in each part. Even if—following a modern fashion—we

try to ignore the fact that men and women are male and female, they do

not cease to be complementary to one another. This is apparent in those

professions such as education, where it is the fashion to obliterate

the distinction between male and female teachers.

An instructive demonstration of the irreducibility of the dyad is

found in Hegel's Logic to which reference has already been made.

The dialectic which claims to leave the dyad behind in the act of syn-

thesis does no more than pass from the dyad to the triad leaving the

complementarity of the opposing terms intact. This can be seen in the

dyad Being—Nothing.* This is an authentic dyad and it comes from

the monad by the two methods of centripetal and centrifugal approach.

The monad is the totality of recurrent elements without distinction. It is

true that looked at in one way this is pure being, while in another aspect

it is nothing. It is also true that there is a triad Being—Nothing-

Becoming, but the triad does not resolve the contradiction; it is a step

[* Cf. G. W. F. Hegel Logic translated by Wallace, 2nd. Edition, pp. 158-62. 'If

the opposition in thought is stated in this immediacy as Being to Nothing, the shock of

its nullity is too great not to stimulate the attempt to fix Being and secure it against the

transition into Nothing'. Cf. also pp. 174-9 for Hegel's account of the dyads finite-

infinite and Being-for-self and Being-for-other].

in understanding the nature of reality, and a very important step, but it

is not a step out of the situation presented to us by the very nature of

our experience. We still remain confronted with the contradiction that

the attempt to derive understanding from knowledge leads us both to

pure being and to nothing. We pass through the dyad to come to the

triad, we do not move out of it. The dyad does not supersede the monad,

nor is it superseded by the triad into which it leads. It is always per-

missible to regard any structure we meet as a monad—that is as diversity

in unity—but the better we grasp the universal character of the structure,

the more clearly does its inherent polarity become apparent. The

universe itself is impregnated with the male and female principles.

Let us consider an example where, at first sight, the dyad is by no

means obvious. A tree is a structured whole. We can establish its

monad by the two methods. First method. The tree has such and such

botanical characteristics: it belongs to a family, genus, species and

variety of its kind. It has such and such a shape,colours and appearance

in its environment. It is of such an age and its condition is sound or

diseased. Its height, girth, the depths of its roots can be measured. It

can be represented by pictures, diagrams or by a detailed enumeration

of its parts. Even the number of its leaves can be counted. And this

reminds us to add its seasonal changes, its flowers and fruit and seed.

Combining all these elements in a single act of attention, we establish

the monad for this particular tree. Second method. The tree is a material

object and so part of the world of things. It is a chemical substance. It

is alive and so part of the biosphere. It is a tree among trees and the

forest is the tree-world. For man, it is a source of valuable products

and so it enters into the human world. It is a part of the prodigious

process of energy transformations by which solar energy is captured

and stored up in chemical form through photosynthesis, and so it plays

its part in what Gurdjieff calls the 'common cosmic exchange of sub-

stances.' Once again the monad has emerged and as we blend the two

pictures into one the tree stands out as an object to be understood. But

it also stands out as an ambiguous object. Are we looking at the tree as a

tree or as a manifestation of the forces of nature? Do we see it as it is in

itself or as it is for us? Do we see it as a process of transformation, a

source of experience and activity, a member of the great family of trees,

the mother of a new forest? Or do we picture it as the bearer of life with

limitless potential for participation in all the worlds to which it belongs?

In short, do we think of it as a male nature or a female one? Evidently

both, and both together. The two are distinct and yet inseparable. The

distinction is not artificial and it has nothing to do with sex for the tree

is probably hermaphrodite. It has to do with the indrawing and the

outgoing tendencies inherent in the very fact of its being what it is.

The tree exemplifies the dyad in another way: in the two-fold source

of its life at the leaves and at the roots. It is drawn down into the earth

and it reaches up to the sky. So powerful is the impression of polarity

we receive in looking at a tree that it has become a symbol of the twin

processes of involution and evolution which form the dyad of universal

existence.

It has to be admitted that no description will adequately convey the

notion of complementarity. Among physical scientists it is accepted as

the most straight-forward way of describing the dual nature of light

(photon and wave) or of subatomic electric elements (particle and wave).

There is no suggestion that the principle of complementarity is more

than a way of describing a group of recurrent elements (interference

experiments for instance). It is not usually claimed as a step towards

understanding. Even when it is brought into the philosophy of science,

it tends to be associated with the notion of equivalence used by Einstein

in general relativity theory and with Heisenberg's uncertainty principle.

In our view it is universal and necessary for any practical understanding

of the world.

We should look for strong dyads which clearly and fully exemplify

the systemic attribute. Every pair of terms is, in form, a dyad; but the

vast majority of such pairs are such weak dyads that we cannot gain

much from studying them.

We have distinguished strength and adequacy. This distinction

scarcely applies to the monad, but it is very important for the dyad.

There can be a high degree of complementarity, but a low degree of

adequacy. Two faces of a coin are complementary; neither is effectual

without the other: but it is only in special situations that the term-

character of poles is present. When coins are used as currency, we ignore

the difference of face. Only when we are tossing the coin, or perhaps

looking for its date, do we pay attention to the difference of face. Here

we have the example of a structure that can be treated as a dyad; but

whose term characters are adequate only in a special context. Consider

next another pair: positive and negative electric charges. Here the

adequacy of the terms is obvious. The polarity of the system is complete.

Nevertheless, the pair do not make a strong dyad, because they manifest

complementarity only through bodies under special conditions. The

force of the dyad arises only when charged bodies are separated by a

non-conducting, rigid construction. The pair '+ and — electric charge'

lacks the concreteness of a true dyad. A final example: male and female

of different species such as a cat and a tortoise. The term characters are

polar, but there is no complementarity: the dyad is a very weak one,

for they cannot mate.

In any actual structure, we can find many dyadic elements. Most of

them will be weak or inadequate: but some will be necessary for the

harmony of the structure as a whole. Thus, in all material structures the

dyad stress-strength must be calculated for all relevant elements, in

order to tell whether the structure will be stable. In a dynamic system

the disturbing and restoring forces must be known in order to predict

how the system will behave. The basic distinction in a human society

is that of the active oligarchy and the passive majority. This dyad must

be kept in mind as it influences all other elements of the structure.

Before we leave the dyad, we must emphasize the essentially dyadic

character of our Indo-European languages with their subject-predicate

construction. This attribute is a reflection of the dualistic nature of man

himself at the present stage of his evolution. Our functional mechanisms

are dominated by dyads: active and passive states, pleasant and un-

pleasant sensations, like and dislike, desire and aversion, approval and

disapproval, yes and no in all its forms; these and a score of other dyads

permeate the human psyche and its functions. We do not, however,

readily accept the complementarity of all these dyads. We tacitly assume

that we can have one term without the other and so constantly are led

to expect the impossible.

It is a great step forward, when we learn to accept the comple-

mentarity of dyads and cease to look for its removal by the suppression

or elimination of one of the terms. There is a way beyond the dayd:

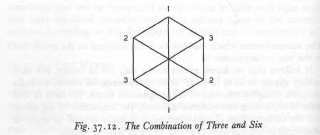

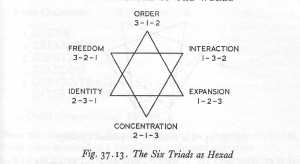

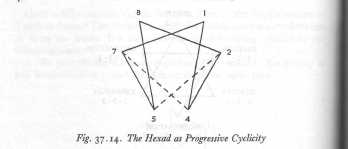

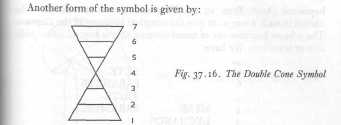

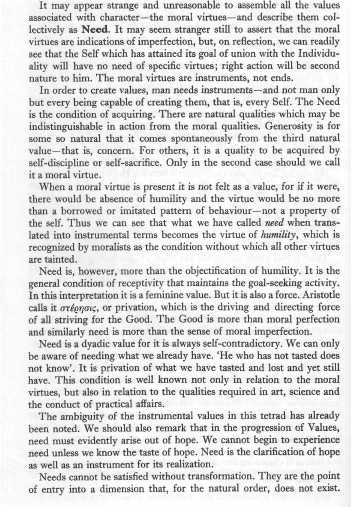

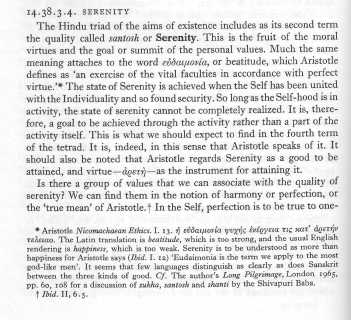

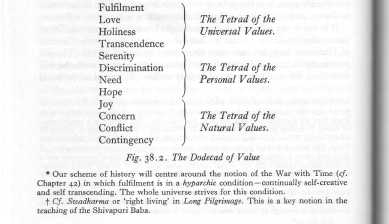

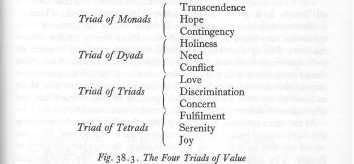

but it is the way of advance towards systems of higher complexity and also