Appendix

The Copper Scroll

The Copper Scroll from cave III is a remarkable document from more than one point of view. First, it is one of the few Qumran discoveries made by the archaeologists themselves and not by the Bedouin. Next, it is the only text engraved on metal, a fact which caused a delay of four years between the actual finding of the Scroll and the revelation of its contents. During the course of the centuries the copper sheets had become so badly oxidized and frail that it was no longer possible to unroll them; they had instead to be divided into longitudinal strips. This was finally achieved in 1956 by Professor H. Wright Baker of Manchester University. In the meantime, however, there was a good deal of speculation as to the nature of the work. What important message had the people of Qumran recorded on such enduring material? The answer, when it came, caused some surprise. This was a list of hidden treasure, the only non-religious composition recovered from Qumran.

So far, at the start of 1962, the official edition of the Copper Scroll has still not made its appearance. Nevertheless, two scholars have anticipated its publication with studies of their own. J.T. Milik was the first, with a French translation of the text (Revue Biblique, 1959, pp. 321-57). This was followed in 1960 by The Treasure of the Copper Scroll, in which J.M. Allegro gives a transcription of the Hebrew (as he reads it) and a copy of the text drawn by an artist. He was not allowed to publish the photographs.

Unfortunately, these two translations differ so vastly that it is difficult to believe that Milik and Allegro were working on the same document, and since there is as yet no means of checking them I have regretfully decided not to discuss the Scroll in any detail in the present book, but to restrict my remarks to the few ascertainable facts and to the principal questions raised by this most baffling document.

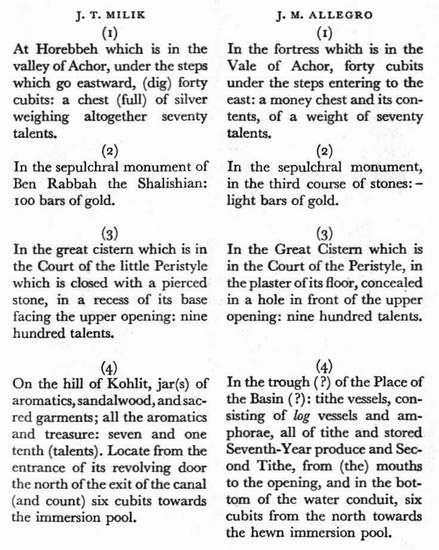

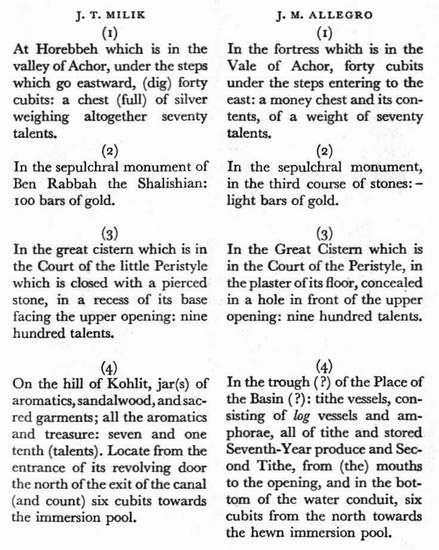

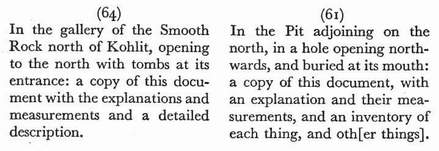

The inscription lists over sixty hiding-places (sixty-four according to Milik, against Allegro's sixty-one) where gold, silver, aromatics, scrolls, etc., are said to have been deposited. These are located as being in, or in the neighbourhood of, tombs, cisterns, canals, underground passages, and so on, most of them in Judaea, but such ancient clues, many of them vanished long ago, are not going to be easy to trace. The following excerpts from the beginning and the end of the Scroll, set out in parallel columns, illustrate both the characteristic flatness of the text and the startling discrepancies between Milik's interpretation and that of Allegro.

Table of differences (side by side) in translation.

This strange document refers, according to Allegro's reckoning, to over three thousand talents of silver, nearly one thousand three hundred talents of gold, sixty-five bars of gold, six hundred and eight pitchers containing silver, and six hundred and nineteen silver and gold vessels. In other words, using the post-biblical value of the talent as a yardstick, the total of precious metal involved would amount to sixty-five tons of silver and twenty-six tons of gold.

But was this treasure a real one, and is the assessment of the talent correct? Who could have possessed such a fortune, and when and by whom was it concealed? These are the questions exercising the minds of scholars, and it will amaze no one to learn that although the Scroll itself is barely known to all but two of them, already three solutions have been advanced.

The first of these, proposed by J.T. Milik, defines the work as fiction and as falling into the category of legends about hidden treasure. He believes that this is indicated by the exaggerated sum of the riches, and maintains that the chief interest of the Scroll lies in the fields of linguistics and topography. He dates it from about A.D. 100, thus ruling out any connexion with the rest of the Qumran documents deposited in the caves not later than A.D. 68.

The remaining two arguments hold that the treasure was indeed real and that it represented either the fortune of the Essene sect, hidden no doubt in A.D. 68 (A. Dupont-Sommer), or that of the Temple of Jerusalem (K. G. Kuhn, Chaim Rabin). J. M. Allegro belongs to the same school of thought, but adds that it was the Zealots who were responsible for concealing the gold and silver and for writing the Scroll. According to him, these Zealots, a fanatical band of Jewish rebels who fought against Rome from A.D. 66 to 70, occupied the Qumran area (already abandoned by the Essenes) in A.D. 68, and unsuccessfully defended it against the Romans in the summer of the same year.

As far as Milik's theory is concerned, it would certainly dispose of the difficulty arising from the colossal quantity of treasure. On the other hand, it is unable to account for two striking characteristics of the Scroll, namely its dry realism, very different from that of ancient legends, and the fact that it is recorded on copper, an expensive material, instead of on leather or papyrus. If the author is right in assuming that the composition was intended as a sort of fairy-story, the present text can only represent a sketch or outline of such a work. But would anyone in their senses have engraved their literary notes on copper?

The contention that the treasure was a real one is, of course, supported by the very arguments which undermine Milik's. The business-like style, and the enduring material on which the catalogue is inscribed, would seem to suggest that the writer was not indulging in some frivolous dream. Again, Dupont-Sommer's allocation of the fortune to the Essenes appears sensible in view of the. fact that the Copper Scroll was found among documents known to derive from Qumran. By comparison, it requires a strong feat of the imagination to accept that it belonged originally to the treasure chambers of the Temple and was placed in hiding, in a hostile environment, in A.D. 68 - before, that is to say, there was any immediate danger to the capital city of Jerusalem. Allegro bypasses part of this objection by presuming that at that time Qumran was no longer unfriendly to the Jerusalem authorities, being by then in the hands of the Zealots. But there is, as yet, no satisfactory explanation as to why the sack of Temple and city should have been foreseen, and provided for, so early.

However, in favour of Kuhn, Rabin, and Allegro, it is feasible to envisage a fortune of this size as belonging to the Temple, whereas, despite Dupont-Sommer's undoubtedly true remarks concerning the apparent compatibility of religious poverty and fat revenues, it is still hard to believe that the Essenes, a relatively small community, should have amassed such disproportionate riches.

So much for the initial skirmishing. No doubt, once the Copper Scroll makes its official debut, even more varied arguments will be stoutly defended and as briskly opposed.

Unfortunately, it seems as though the key to the mystery, 'the copy of this document with the explanations, measurements, and detailed description', may continue to lie in the 'Gallery of the Smooth Rock north of Kohlit'. Or is it in the ' Pit adjoining on the north, in a hole opening northwards'?