RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

"Tros of Samothrace," Appleton-Century, New York, September 1934

This saga is a composite work containing stories originally published in Adventure magazine under the following titles:

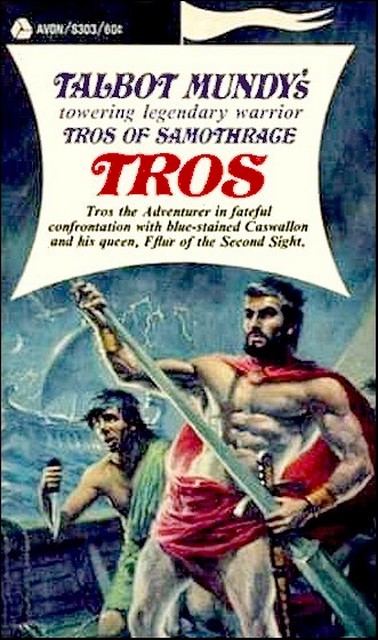

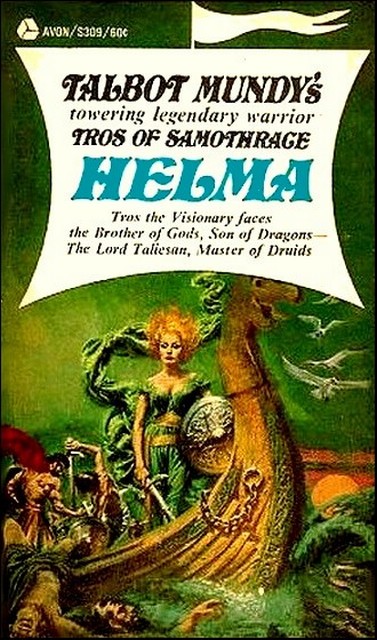

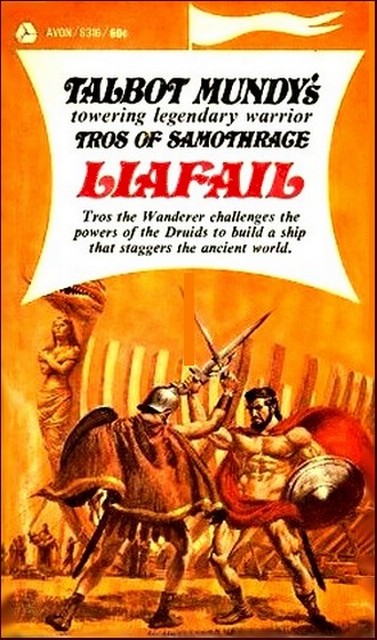

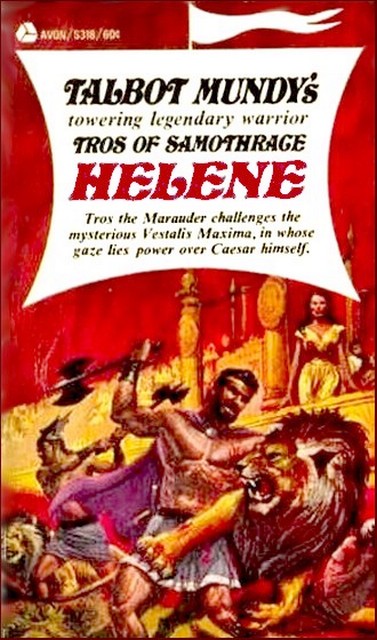

The saga was also published in 1967 by Avon in four paperback volumes with the titles:

Click here to see cover

images

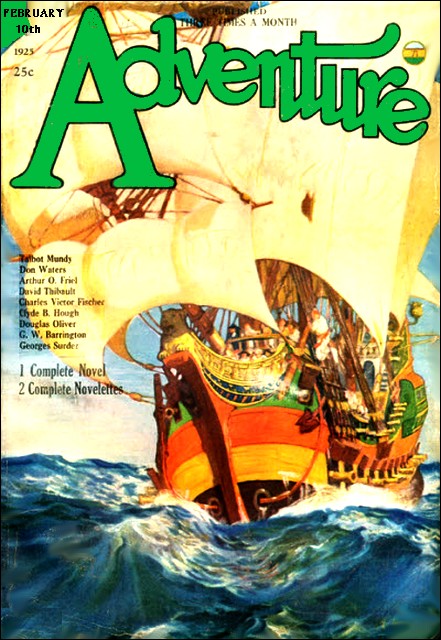

Adventure, February 10, 1925, with first part of "Tros of Samothrace"

Arthur S. Hoffman, chief editor of Adventure from 1912 to 1927, wrote the following article for the magazine's "Camp Fire" section as an afterword to the first part of "Tros of Samothrace." The article contains, and is written around, a letter from Talbot Mundy in which the author describes his views of Julius Caesar as a man and a leader, and speculates on the nature of the Samothracian Mysteries.

Thanks and credit for making the text of this article available to RGL readers go to Matthew Whitehaven, who donated a copy from his personal archive for inclusion in this new edition of the book.

When Talbot Mundy first began talking to me about the Tros stories (there are to be others) and about Caesar and his times I began cussing myself for having done what I very particularly hold in contempt—I'd been swallowing whole some other fellow's collecting and interpretation of facts and the whole conception resulting therefrom. All of us are naturally inclined to do this; that is why our civilization shows so many stupidities. But a minority struggle against this lazy, sheep-like habit and try to think for themselves as best they can. I'd flattered myself I was among those who tried—and then Talbot Mundy came along and made me see what a stupid sheep I'd been.

Since school I haven't studied history (except for a few years that of ancient Ireland) or even done more than desultory reading—for example, learning from Hugh Pendexter's stories more than I'd ever known of the history of our own country, and from others of our fiction writers more of the history of various countries. I'd had to translate Caesar's Commentaries and to absorb more or less history as she is taught. It was impressed upon me that Caesar was a great man, an heroic figure. His Commentaries I accepted as true word for word. Did not other historians accept and build upon them? Were they not everywhere perpetuated in the schools without ever a question raised as to their complete trustworthiness.

In later years, of course, I learned that historians, instead of being infallible, were merely human beings grubbing among scattered bits of facts and trying to build out of them a complete conception of something on which they generally had no first hand information whatever. Also, that if one them made a mistake, many of those after him were likely to swallow the mistake and perpetuate it, and, on the other hand, that the historian of today, having at hand added bits of facts, is likely to consider the historian of yesterday very much out of date and not to be trusted too much in his deductions. In other words, any historian, including him of today, is, by the historian's own test, not a final authority but merely a more or less skilful guesser at the whole truth from what small bits of it he manages to collect.

Yet I had been swallowing whole, without question, all the historians had been handing me. To be sure, Shaw years ago had merrily slapped most of the historians in the face and presented a comparatively new conception of Julius Caesar, but by that time I'd reached the stage where I didn't accept other people's say-so so easily. Like a true sheep, I relapsed pretty well into my old conception of a very heroic Caesar and a very wonderful and rather admirable Roman Empire.

Then Mr. Mundy, after much delving into books, arose and challenged the whole works and I awoke to contempt for myself. I didn't mean I just scrapped all my old conceptions and accepted his, but I realized that I, at least, had nothing with which to support the old ideas against the new. Maybe Mr. Mundy is all or partly wrong. I don't know. Let's hear the other side in rebuttal. There are plenty of historians, both professional and amateur, among us who gather at Camp-Fire. Let's hear from them.

One thing seems clear to me. If historians have accepted the Commentaries as completely as Mr. Mundy says, then I'm "off them" and for the same reason as Mr. Mundy—I hesitate to swallow whole the account of himself and his doings that an ambitious man wrote or had written to be read by the voters and politicians he must win to him in order to realize his ambitions. Let's hear Mr. Mundy's case:

I have followed Caesar's Commentaries as closely as possible in writing this story, but as Caesar, by his own showing, was a liar, a brute, a treacherous humbug and a conceited ass, as well as the ablest military expert in the world at that time; and as there is plenty of information from ancient British, Welsh and Irish sources to refute much of what he writes, I have not been to much trouble to make him out a hero.

In the first place, I don't believe he wrote his Commentaries. His secretary did. Most of it is in the third person, but here and there the first person creeps in, showing where Caesar edited the copy, which was afterward, no doubt, transcribed by a slave who did not dare to do any editing.

The statement is frequently made that Caesar must be accurate because all other Roman historians agree with him. But they all copied from him, so that argument doesn't stand. No man who does his own press-agenting is entitled to be accepted on his own bare word, and as Caesar was quite an extraordinary criminal along every line but one (he does not seem to have been a drunkard) he is even less entitled to be believed than are most press agents. He was an epileptic, whose fits increased in violence as he grew older, and he was addicted to every form of vice (except drunkenness) then known. He habitually used the plunder of conquered cities for the purpose of bribing the Roman senate; he cut off the right hands of fifty thousand Gauls on one occasion, as a mere act of retaliation; he broke his word as often, and as treacherously, as he saw fit; and he was so vain that he ordered himself deified and caused his image to be set in Roman temples, with a special set of priests to burn incense before it.

As a general he was lucky, daring, skilful—undoubtedly a genius. As an admiral, he was fool enough to anchor his own feet off an open shore, where, according to his own account, a storm destroyed it. (In this story I have described what may have happened.) And he was idiot enough to repeat the mistake a year later, losing his fleet a second time.

He pretends his expeditions to Britain were successful. But a successful general does not usually sneak away by night. On his second invasion of Britain he actually raided as far as Lunden (London) but it is very doubtful whether he actually ever saw the place, and it is quite certain that he cleared out of Britain again as fast as possible, contenting himself with taking hostages and some plunder to make a show in his triumphal procession through the streets of Rome. And whatever Caesar wrote about those expeditions, what his men had to say about them can be surmised fairly accurately from the fact that Rome left Britain severely alone for several generations.

Caesar reports that the Britons were barbarians, but there is plenty of evidence to the contrary. They were probably the waning tag-end of a high civilization; which would mean that they had several distinct layers of society, including an aristocratic caste—that they had punctilious manners, and a keen and probably quixotic sense of chivalry. For instance, Caesar's account that they fought nearly naked is offset by the fact that they thought it cowardly not to expose their bodies to the enemy. Their horsemanship, their skill in making bronze wheels and weapons, and their wickerwork chariots can hardly be called symptoms of barbarism.

The Britons were certainly mixed; their aristocrats were fair-haired and very white-skinned; but there were dark-haired, dark-skinned folk among them, as well as rufous Northmen, the descendants of North Sea rovers. They can not have been ignorant of the world, because for centuries prior to Caesar's time there had been a great deal of oversea trade in tin. They used gold, and in such quantities that it must have been obtained from oversea. They were skilful in the use of wool. And they were near enough to Gaul to be in constant touch with it; moreover, they spoke practically the same language as the Gauls.

The Samothracians Mysteries have baffled most historians and, down to this day, nothing whatever is known of their actual teaching. Of course, all the Mysteries were secret; and at all times any initiate, of whatever degree, who attempted to reveal the secrets, or who did reveal any of them even unintentionally, was drastically punished. At certain periods, when the teaching had grown less spiritual, such offenders were killed.

Samothrace has no harbors and no safe anchorage, which may account for the fact that it has never been really practically occupied by any foreign power, although it is quite close to the coast of Greece. The ruins of the ancient temples remain today. It is probably true that the Samothracian Mysteries were the highest and the most universally respected, and that their Hierophants sent out from time to time emissaries, whose duty was to purify the lesser Mysteries in different parts of the world and to reinstruct the teachers. At any rate it is quite certain that all the Mysteries were based on the theory of universal brotherhood (any Free and Accepted Mason will understand at once what is meant by that) and that they had secret signs and passwords in common, by means of which any initiate could make himself known to another, even if he could not speak the other's language. The Mysteries extended to the far East, and travel to the East, for the purpose of studying the Mysteries was much more common that is frequently supposed.

Caesar loathed the Druids (who were an order—and a very high one—of the Mysteries) because his own private character and life were much too rotten to permit his being a candidate for initiation. In all ages the first requirement for initiation has been clean living and honesty. He admits in his Commentaries that he burned the Druids alive in wicker cages, and he accuses the Druids of having done the same thing to their victims; but Caesar's bare word is not worth the paper it is written on. His motive is obvious. Any any one who knows anything at all about the Mysteries—especially any Free and Advanced Mason—knows without any doubt whatever that no initiate of any genuine Mystery would go so far as to consider human sacrifice or any form of preventable cruelty.

Kissing was a general custom among the Britons. Men kissed each other. The hostess always kissed the guest. It was a sign of good faith and hospitality, the latter being almost a religion. Whoever had been kissed could not be treated as an enemy while under the same roof.

The spelling and pronunciation of common names presents the usual problem. Gwenhwyfar, of course, is the early form of Guinevere, but how it was pronounced is not easy to say. Fflur was known as Flora to the Romans, and the accounts of her beauty had much to do with Caesar's second invasion of Britain, for he never could resist the temptation to ravish another man's wife if her good lucks attracted his attention. (But I will tell that in another story.)

To me there seems no greater absurdity than to take Caesar's Commentaries at their face value and to believe on his bare word that the Britons (or the Gauls) were savages. It is impossible that they can have been so. The Romans were savages, in every proper—if not commonly accepted—meaning of the word. The only superiority they possessed was discipline—but the Zulus under Tchaka also had discipline. The Romans, in Caesar's time at any rate, had no art of their own worth mentioning, no standard of honor that they observed (although they were very fond of prating about honor, and of imputing dishonor to other people), no morals worth mentioning, no religion they believed in, and no reasonable concept of liberty. They were militarists, and they lived by plundering other people. They were unspeakably corrupt and vicious. A Roman legion was a machine that very soon got out of hand unless kept hard at work and fed with loot, including women. They were disgraceful sailors, using brute force where a real seaman would use brains, and losing whole fleets, in consequence, with astonishing regularity. They were cruel and vulgar, their so-called appreciation of art being exactly that of our modern nouveaux-riches; whatever was said to be excellent they bought or stole and removed to Rome, which was a stinking slum even by standards of the times, infested by imported slaves and licentious politicians.

But they did understand discipline, and they enforced it, when they could, with an iron hand. That enabled them to build roads, and it partly explains their success as law-makers. But Rome was a destroyer, a disease, a curse to the earth. The example that she set, of military conquest and imperialism, has tainted the world's history ever since. It is to Rome and her so-called "classics" that we owe nine-tenths of the false philosophy and mercenary imperialism that has brought the world to its present state of perplexity and distress, long generations having had their schooling at the feet of Rome's historians and even our laws being largely based on Rome's ideas of discipline combined with greed.

Rome rooted out and destroyed the Mysteries and gave us in their place no spiritual guidance but a stark materialism, the justification of war, and a world-hero—Caius Julius Caesar, the epileptic liar, who, by own confession, slew at least three million men and gave their women to be slaves or worse, solely to further his own ambition. Sic transit gloria Romae! —Talbot Mundy

The last paragraph gives this little brain a mighty lot to think about. Is it the Roman Empire we are to thank for much of our present-day materialism? I wonder what our world would be like now if some other people or peoples had brought to the front another kind of civilization and standard? After all it is the moral standard, the mental point of view, that endures. The Roman Empire has rotted into mere history that we argue about. But, after all these centuries, is its moral and social standard gripping and guiding us today? What will our own moral and social standard do to the future of the world?

These Mysteries of Samothrace and elsewhere—what if Rome had not crushed them out? Or did she? Are they and their teachings still among us, our backs turned to them or out feet ground on them as backs and feet were in Rome's day?

After a thousand or two years we are not quite so material as Talbot Mundy paints the Romans, but still, considering us as a whole, isn't materialism our controlling influence? The magnificent Roman Empire is rotted, gone, wiped out. The world has pretty well employed itself in proving that materialistic nations can not endure. Some time will it get tired and start developing the other kind so that they in turn can have their trial? Will our nation ever do that, or will it just go on doing what the Roman Empire did and become what the Roman Empires is—a thing wiped from the physical earth but sending its curse of materialism down the centuries?

We're not a materialistic nation? Well, if we've gone so far we don't even know we're materialistic, we're in worse shape than I thought.

(Source: The Camp-Fire, Adventure, February 10, 1925)

These then are your liberties that ye inherit. If ye inherit

sheep and oxen, ye protect those from the wolves. Ye know there are wolves,

aye, and thieves also. Ye do not make yourselves ridiculous by saying neither

wolf nor thief would rob you, but each to his own. Nevertheless, ye resent my

warning. But I tell you, Liberty is alertness; those are one; they are the

same thing. Your liberties are an offense to the slave, and to the enslaver

also. Look ye to your liberties! Be watchful, and be ready to defend them.

Envy, greed, conceit and ignorance, believing they are Virtue, see in

undefended Liberty their opportunity to prove that violence is the grace of

manhood.

—from The Sayings of the Druid Taliesan

TOWARD sunset of a golden summer evening in a clearing in a dense oak forest five men and a woman sat beside a huge flat rock that lay half buried in the earth and tilted at an angle toward where the North Star would presently appear.

At the southern end of the clearing was a large house built of mud and wattle with a heavy thatched roof; it was surrounded by a fence of untrimmed branches, and within the enclosure there were about a dozen men and women attending a fire in the open air, cooking, and carrying water.

Across the clearing from a lane that led between enormous oaks, some cattle, driven by a few armed men clothed in little other than skins dawdled along a winding cow-path toward the opening in the fence. There was a smell of wood smoke and a hush that was entirely separate from the noise made by the cattle, the soft sigh of wind in the trees, the evensong of birds and the sound of voices. Expectancy was in the air.

The five men who sat by the rock were talking with interruptions, two of them being foreigners, who used one of the dialects of southern Gaul; and that was intelligible to one of the Britons who was a druid, and to the woman, who seemed to understand it perfectly, but not to the other men, to whom the druid had to keep interpreting.

"Speak slowly, Tros, speak slowly," urged the druid; but the big man, although he spoke the Gaulish perfectly, had a way of pounding his left palm with his right fist and interjecting Greek phrases for added emphasis, making his meaning even more incomprehensible.

He looked a giant compared to the others although he was not much taller than they. His clothing was magnificent, but travel-stained. His black hair, hanging nearly to his shoulders, was bound by a heavy gold band across his forehead. A cloak of purple cloth, embroidered around the edges with gold thread, partly concealed a yellow tunic edged with gold and purple.

He wore a long sword with a purple scabbard, suspended from a leather belt that was heavily adorned with golden studs. His forearm was a Titan's, and the muscles on his calves were like the roots of trees; but it was his face that held attention: Force, under control with immense stores in reserve; youth unconquerable, yet peculiarly aged before its time; cunning of the sort that is entirely separate from cowardice; imagination undivorced from concrete fact; an iron will and great good humor, that looked capable of blazing into wrath—all were written in the contours of forehead, nose and jaw. His leonine, amberous eyes contained a hint of red, and the breadth between them accentuated the massive strength of the forehead; they were eyes that seemed afraid of nothing, and incredulous of much; not intolerant, but certainly not easy to persuade.

His jaw had been shaved recently, to permit attention to a wound that had now nearly healed, leaving a deep indentation in the chin, and the black re- growing beard, silky in texture, so darkened the bronze skin that except for his size, he might almost have passed for an Iberian.

"Conops will tell you," he said, laying a huge hand on the shoulder of the man beside him, "how well I know this Caius Julius Caesar. Conops, too, has had a taste of him. I have seen Caesar's butchery. I know how he behaves to druids and to kings and to women and to all who oppose him, if he once has power. To obtain power—hah!—he pretends sometimes to be magnanimous. To keep it—"

Tros made a gesture with his right fist, showed his teeth in a grin of disgust and turned to the other Samothracian* beside him. "Is he or is he not cruel, Conops? Does he keep Rome's promises? Are Rome's or his worth that?" He snapped his fingers.

[* Samothrace—an island in Greece, in the northern Aegean Sea. The name of the island means Thracian Samos ... Samothrace was part of the Athenian Empire in the 5th century BCE, and then passed successively through Macedonian, Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman rule before being returned to Greek rule in 1913 following the Balkan War. Excerpted from Wikipedia. ]

Conops grinned and laid a forefinger on the place where his right eye had been. Conops was a short man, of about the same age as Tros, possibly five-and-twenty, and of the same swarthy complexion; but he bore no other resemblance to his big companion. One bright-blue eye peered out from an impudent face, crowned with a knotted red kerchief. His nose was up-turned, as if it had been smashed in childhood. He had small brass earrings, similar in pattern to the heavy golden ones that Tros wore, and he was dressed in a smock of faded Tyrian blue, with a long knife tucked into a red sash at his waist. His thin, strong, bare legs looked as active as a cat's.

"Caesar is as cruel as a fish!" he answered, nodding. "And he lies worse than a long-shore Alexandrian with a female slave for hire."

The druid had to interpret that remark, speaking in soft undertones from a habit of having his way without much argument. He was a broad-faced young man with a musical voice, a quiet smile and big brown eyes, dressed in a blue-dyed woolen robe that reached nearly to his heels—one of the bardic druids of the second rank.

It was the woman who spoke next, interrupting the druid's explanation, with her eyes on Tros. She seemed to gloat over his strength and yet to be more than half-suspicious of him, holding her husband by the arm and resting chin and elbow on her knee as she leaned forward to watch the big man's face. She was dressed in a marvelously worked tunic of soft leather, whose pricked-in, barbaric pattern had been stained with blue woad. Chestnut hair, beautifully cared for, hung to her waist; her brown eyes were as eager as a dog's; and though she was young and comely, and had not yet borne a child, she looked too panther-like to be attractive to a man who had known gentler women.

"You say he is cruel, this Caesar. Is that because he punished you for disobedience—or did you steal his woman?" she demanded. Tros laughed —a heavy, scornful laugh from deep down near his stomach.

"No need to steal! Caius Julius Caesar gives women away when he has amused himself," he answered. "He cares for none unless some other man desires her; and when he has spoiled her, he uses her as a reward for his lieutenants. On the march his soldiers cry out to the rulers of the towns to hide their wives away, saying they bring the maker of cuckolds with them. Such is Caesar; a self-worshiper, a brainy rascal, the meanest cynic and the boldest thief alive. But he is lucky as well as clever, have no doubt of that."

The druid interpreted, while the woman kept her eyes on Tros.

"Is he handsomer than you? Are you jealous of him? Did he steal your wife?" she asked; and Tros laughed again, meeting the woman's gaze with a calmness that seemed to irritate her.

"I have no wife, and no wife ever had me," he answered. "When I meet the woman who can turn my head, my heart shall be the judge of her, Gwenhwyfar."*

[* Gwenhwyfar—Welsh form of the name Guinevere. Annotator. ]

"Are you a druid? Are you a priest of some sort?" the woman asked. Her glowing eyes examined the pattern of the gold embroidery that edged his cloak.

Tros smiled and looked straight at the druid instead of at her. Conops drew in his breath, as if he was aware of danger.

"He is from Samothrace," the druid remarked. "You do not know what that means, Gwenhwyfar. It is a mystery."

The woman looked dissatisfied and rather scornful. She lapsed into silence, laying both elbows on her knees and her chin in both hands to stare at Tros even more intently. Her husband took up the conversation. He was a middle-sized active-looking man with a long moustache, dressed in wolf-skin with the fur side outward over breeches and a smock of knitted wool.

An amber necklace and a beautifully worked gold bracelet on his right wrist signified chieftainship of some sort. He carried his head with an air of authority that was increased by the care with which his reddish hair had been arranged to fall over his shoulders; but there was a suggestion of cunning and of weakness and cupidity at the corners of his eyes and mouth. The skin of his body had been stained blue, and the color had faded until the natural weathered white showed through it; the resulting blend was barbarously beautiful.

"The Romans who come to our shore now and then have things they like to trade with us for other things that we can easily supply. They are not good traders. We have much the best of it," he remarked.

Tros understood him without the druid's aid, laughed and thumped his right fist on his knee; but instead of speaking he paused and signed to them all to listen. There came one long howl, and then a wolf-pack chorus from the forest.

"This wolf smelt, and that wolf saw; then came the pack! What if ye let down the fence?" he said then. "It is good that ye have a sea around this island. I tell you, the wolves of the Tiber are less merciful than those, and more in number and more ingenious and more rapacious. Those wolves glut themselves; they steal a cow, maybe, but when they have a bellyful they go; and a full wolf falls prey to the hunter. But where Romans gain a foothold they remain, and there is no end to their devouring. I saw Caesar cut off the right hands of thirty thousand Gauls because they disobeyed him. I say, I saw it."

"Perhaps they broke a promise," said the woman, tossing her head to throw the hair out of her eyes. "Commius* the Gaul, whom Caesar sent to talk with us, says the Romans bring peace and affluence and that they keep their promises."

[* Commius—king of the Belgic nation of the Atrebates, initially in Gaul, then in Britain, in the 1st century BCE. For more information, see the Wikipedia article Commius. ]

"Affluence for Commius, aye, and for the Romans!" Tros answered. "Caesar made Commius king of the Atrebates. But do you know what happened to the Atrebates first? How many men were crucified? How many women sold into slavery? How many girls dishonored? Aye, there is always peace where Rome keeps wolf's promises. Those are the only sort she ever keeps! Commius is king of a tribe that has no remaining fighting men nor virgins, and that toils from dawn to dark to pay the tribute money that Caesar shall send to Rome—and for what? To bribe the Roman senators! And why? Because he plans to make himself the ruler of the world!"

"How do you know?" asked the woman, when the druid began to interpret that long speech. She motioned to the druid to be still—her ear was growing more accustomed to the Samothracian's strange pronunciation.

Tros paused, frowning, grinding his teeth with a forward movement of his iron jaw. Then he spoke, looking straight at the woman:

"I am from the isle of Samothrace, that never had a king, nor ever bowed to foreign yoke. My father is a prince of Samothrace, and he understands what that means." He glanced at the druid. "My father had a ship —a good ship, well manned with a crew of freemen—small, because there are no harbors in the isle of Samothrace and we must beach our ships, but seaworthy and built of Euxine* timber, with fastenings of bronze. We had a purple sail; and that, the Romans said, was insolence.

[* Euxine (Euxeinos Pontos = "Hospitable sea") —Greek name for the Black Sea. For more information, see the Wikipedia article Black Sea. ]

"The Keepers of the Mysteries of Samothrace despatched my father in his ship to many lands, of which Gaul was one, for purposes which druids understand. Caesar hates druids because the druids have secrets that they keep from him.

"He denounced my father as a pirate, although Pompey,* the other tribune, who made war on pirates, paid my father homage and gave him a parchment with the Roman safe-conduct written on it. My name, as my father's son, was also on the parchment, as were the names of every member of the crew. I was second in command of that good ship. Conops was one of the crew; we two and my father are all who are left."

[* Pompey (the Great)—Gnaeus or Cnaeus Pompeius Magnus (September 29, 106 BCE—September 29, 48 BCE)— a distinguished military and political leader of the late Roman republic. Hailing from an Italian provincial background, he went on to establish a place for himself in the ranks of Roman nobility, earning the cognomen of Magnus (the Great) for his military exploits against pirates in the Mediterranean Sea after the dictatorship of Lucius Cornelius Sulla ... Pompey was a rival and an ally of Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gaius Julius Caesar. The three politicians would dominate the Roman republic through a political alliance called the First Triumvirate. After the death of Crassus, Pompey and Caesar would dispute the leadership of the entire Roman state amongst themselves. Excerpted from Wikipedia, q.v. ]

Tros paused, met Conops' one bright eye, nodded reminiscently, and waited while the druid translated what he had just said into the British tongue. The druid spoke carefully, avoiding further reference to the Mysteries. But the woman hardly listened to him; she had understood.

"Our business was wholly peaceful," Tros continued. "We carried succor to the Gauls, not in the form of weapons or appliances, but in the form of secret counsel to the druids whom Caesar persecuted, giving them encouragement, advising them to bide their time and to depend on such resources as were no business of Caesar's.

"And first, because Caesar mistrusted us, he made us give up our weapons. Soon after, on a pretext, he sent for that parchment that Pompey had given my father; and he failed to return it. Then he sent men to burn our ship, for the sake of the bronze that was in her; and the excuse he gave was that our purple sail was a defiance of the Roman Eagles. Thereafter he made us all prisoners; and at that time Conops had two eyes."

Gwenhwyfar glanced sharply at Conops, made a half contemptuous movement of her lips and threw the hair back on her shoulders.

"All of the crew, except myself and Conops, were flogged to death by Caesar's orders in my father's presence," Tros went on. "They were accused of being spies. Caesar himself affects to take no pleasure in such scenes, and he stayed in his tent until the cruelty was over. Nor did I witness it, for I also was in Caesar's tent, he questioning me as to my father's secrets.

"But I pretended to know nothing of them. And Conops did not see the flogging, because they had put his eye out, by Caesar's order, for a punishment, and for the time being they had forgotten him. When the last man was dead, my father was brought before Caesar and the two beheld each other face to face, my father standing and Caesar seated with his scarlet cloak over his shoulders, smiling with mean lips that look more cruel than a wolf's except when he is smiling at a compliment or flattering a woman. And because my father knows all these coasts, and Caesar does not know them but, nevertheless, intends to invade this island—"

The druid interrupted.

"How does he know it is an island?" he asked. "Very few, except we and some of the chiefs, know that."

"My father, who has sailed around it, told him so in an unguarded moment."

"He should not have told," said the druid.

"True, he should not have told," Tros agreed. "But there are those who told Caesar that Britain is a vast continent, rich in pearls and precious stones; he plans to get enough pearls to make a breastplate for the statue of the Venus Genetrix)* in Rome.

[* Venus Genetrix (Latin "Mother Venus")— Venus in her role as the ancestress of the Roman people, a goddess of motherhood and domesticity. A festival was held in her honor on September 26. As Venus was regarded as the mother of the Julian gens in particular, Julius Caesar dedicated a temple to her in Rome. Excerpted from Wikipedia, q.v. ]

"So my father, hoping to discourage him, said that Britain is only an island, of no wealth at all, inhabited by useless people, whose women are ugly and whose men are for the most part deformed from starvation and sickness. But Caesar did not believe him, having other information and being ambitious to possess pearls."

"We have pearls," said the woman, tossing her head again, pulling down the front of her garment to show a big pearl at her breast.

The druid frowned:

"Speak on, Tros. You were in the tent. Your father stood and confronted Caesar. What then?"

"Caesar, intending to invade this island of Britain, ordered that I should be flogged and crucified, saying: 'For your son looks strong, and he will die more painfully if he is flogged, because the flies will torture him. Let us see whether he will not talk, after they have tied him to the tree.'"

"What then?" asked the druid, with a strange expression in his eyes.

"Yes, what then?" said the woman, leaning farther forward to watch Tros's face. There was a half smile on her lips.

"My father offered himself in place of me," said Tros.

"And you agreed to it!" said the woman, nodding, seeming to confirm her own suspicion, and yet dissatisfied.

Tros laughed at her.

"Gwenhwyfar, I am not thy lover!" he retorted, and the woman glared. "I said to Caesar, I would die by any means rather than be the cause of my father's death; and I swore to him to his face, as I stood between the men who held me, that if my father should die first, at his hands, he must slay me, too, and swiftly.

"Caesar understood that threat. He lapsed into thought awhile, crossing one knee over the other, in order to appear at ease. But he was not at ease, and I knew then that he did not wish to slay either my father or me, having another use for us. So I said nothing."

"Most men usually say too much," the druid commented.

"And presently Caesar dismissed us, commanding that we should be confined in one hut together," Tros went on. "And for a long while my father and I said nothing, for fear the guard without might listen. But in the night we lay on the dirt floor with our heads together, whispering, and my father said:

"'Death is but a little matter and soon over with, for even torture must come to an end; but a man's life should be lived to its conclusion, and it may be we can yet serve the purpose for which we came to Gaul. Remember this, my son,' said he, 'that whereas force may not prevail, a man may gain his end by seeming to yield, as a ship yields to the sea. And that is good, provided the ship does not yield too much and be swamped.'

"Thereafter we whispered far into the night. And in the morning when Caesar sent for us we stood before him in silence, he considering our faces and our strength. My father is a stronger man than I.

"There were the ropes on the floor of the tent, with which they were ready to bind us; and there were knotted cords for the flogging; and two executioners, who stood outside the tent—they were Numidians*— black men with very evil faces. And when he had considered us a long time Caesar said:

"'It is no pleasure to me to hand men of good birth over to the executioners.'

[* Numidia—an ancient African Berber kingdom and later a Roman province on the northern coast of Africa between the province of Africa (where Tunisia is now) and the province of Mauretania (which is now the western part of Algeria's coastal area). What was Numidia then is now the eastern part of Algeria's coast... Excerpted from Wikipedia, q.v. ]

"He lied. There is nothing he loves better, for he craves the power of life and death, and the nobler his victim the more subtly he enjoys it. But we kept silence. Then he rearranged the wreath that he wears on his head to hide the baldness, and drew the ends of his scarlet cloak over his knees and smiled; for through the tent door he observed a woman they were bringing to him. He became in a hurry to have our business over with.

"It may be that the sight of the woman softened him, for she was very beautiful and very much afraid; or it may be that he knew all along what demand he would make. He made a gesture of magnanimity and said:

"'I would that I might spare you; for you seem to me to be worthy men; but the affairs of the senate and the Roman people have precedence over my personal feelings, which all men will assure you are humane. If, out of respect for your good birth and courageous bearing—for I reckon courage chiefest of the virtues—I should not oblige you to reveal the druids' secrets, I would expect you in return to render Rome a service. Thereafter, you may both go free. What say you?'

"And my father answered: 'We would not reveal the druids' secrets, even if we knew them; nor are we afraid to die.'

"And Caesar smiled. 'Brave men,' he said, 'are more likely than cowards to perform their promises. I am sending Caius Volusenus* with a ship to the coast of Britain to discover harbors and the like, and to bring back information. If he can, he is to persuade the Britons not to oppose my landing; but if he can not, he is to discover the easiest place where troops can be disembarked. It would give me a very welcome opportunity to exercise my magnanimity, which I keep ever uppermost in mind, if both of you would give your promises to me to go with Caius Volusenus, to assist him with all your knowledge of navigation; and to return with him. Otherwise, I must not keep the executioners waiting any longer.'

[* Gaius Volusenus Quadratus—a Roman tribune under Julius Caesar. In 55 BCE Volusenus was sent out by Caesar in a single warship to undertake a week-long survey of the coast of south eastern Britain prior to Caesar's invasion. He probably examined the Kent coast between Hythe and Sandwich. When Caesar set off with his troops however he arrived at Dover and saw that landing would impossible. Instead he traveled north and beached his ships near Walmer. Volusenus failed to find the great natural harbor at Richborough, used by Claudius in his later invasion ... There is no record of Caesar's reaction to Volusenus' apparent intelligence failings ... Excerpted from Wikipedia, q.v. ]

"I looked into my father's eyes, and he into mine, and we nodded. My father said to Caesar:

"'We will go with Caius Volusenus and will return with him, on the condition of your guarantee that we may go free afterward. But we must be allowed to travel with proper dignity, as free men, with our weapons. Unless you will agree to that, you may as well command your executioners, for we will not yield.'

"And at that, Caesar smiled again, for he appreciates dignity—more especially if he can subtly submit it to an outrage.

"'I have your promise then?' he asked; and we both said, 'Yes.'

"Whereat he answered:'I am pleased. However, I will send but one of you. The other shall remain with me as hostage. You observe, I have not put you under oath, out of respect for your religion, which you have told me is very sacred and forbids the custom we Romans observe of swearing on the altar of the gods.'

"But he lied—he lied. Caesar cares nothing for religion.

"'The son shall make the journey and the father shall remain,' he said to us, 'since I perceive that each loves the other. Should the son not keep his promise, then the father shall be put to certain trying inconveniences in the infliction of which, I regret to say, my executioners have a large experience.'

"He would have dismissed us there and then, but I remembered Conops, who alone of all our crew was living, and I was minded to save Conops. Also I knew that my father would wish that, and at any cost, although we dared not speak to each other in Caesar's presence. So I answered:

"'So be it, Caesar. But the promise on your part is that I shall go with dignity, and thereto I shall need a servant.'

"'I will give you a Gaul,' said he.

"'I have no use for Gauls,' I answered.'They are treacherous. And at that he nodded.'But there is one of our men,' said I, 'who escaped your well-known clemency and still endures life. Mercifully, your lieutenants have deprived him of an eye, so he is not much use, but I prefer him, knowing he will not betray me to the Britons.'

"Caesar was displeased with that speech, but he was eager they should bring the woman to him, so he gave assent. But he forbade me to speak with my father again until I should return from Britain, and they took my father away and placed him in close confinement.

"A little later they brought Conops to me, sick and starved; but the centurion* who had charge of prisoners said to me that if I would promise to bring him back six fine pearls from Britain, he for his part would see to it that my father should be well treated in my absence. So I promised to do what might be done. I said neither yes nor no."

[* centurion (Latin: "centurio")—a professional officer of the Roman army. In the Roman infantry, centurions commanded a centuria (century) of between 60 and 160 men, depending on force strength and whether or not the unit was part of the First Cohort. In the Roman legions' tactical organization, the centurions ranked above the optios and below the Tribuni Angusticlavii—the aristocratic senior officers of the Equestrian Class, subordinate to the legion commander, the Legatus Legionis. In comparison to a modern military organization, they would be roughly equivalent to an Infantry company commander, with the army rank of Captain, with senior centurions roughly equivalent to Majors. Wikipedia . ]

"We have pearls," said the woman, looking darkly at Tros, tossing her hair again.

"Nevertheless," Tros answered, "to give pearls to a Roman is to arouse greed less easy to assuage than fire!"

"You said Caesar will make himself master of the world. What made you say that?" asked the woman.

"I will tell that presently, Gwenhwyfar—when Caswallon* and the other druids come," he answered.

[* By the Romans called Cassivellaunus. Author's footnote. Cassivellaunus was a historical British chieftain who led the defence against Julius Caesar's second expedition to Britain in 54 BCE. He also appears in British legend as Cassibelanus, one of Geoffrey of Monmouth's kings of Britain, and in the Mabinogion and Welsh Triads as Caswallawn, son of Beli Mawr ... Excerpted from Wikipedia, q.v.]

Listen to me before ye fill your bellies in the places habit

has accustomed you to think are safe. Aye, and while ye fill your bellies,

ponder. Hospitality and generosity and peace, ye all agree are graces. Are

they not your measures of a man's nobility? Ye measure well. But to ignorant

men, to whom might is right, I tell you gentleness seems only an opportunity.

If ye are slaves of things and places, appetites and habits, rather than

masters of them, surely the despoiler shall inflict upon you a more degrading

slavery. Your things and places he will seize. Your appetites and habits he

will mock, asserting that they justify humiliation that his violence imposes

on you. Be ye, each one, master of himself, or ye shall have worse

masters.

—from The Sayings of the Druid Taliesan

THE long British twilight had deepened until the trees around the clearing were a whispering wall of gloom, and a few pale stars shone overhead. The wolves howled again, making the cattle shift restlessly within the fence, and a dozen dogs bayed angrily. But the five who sat by the rock in the midst of the clearing made no move, except to glance expectantly toward the end of the glade.

And presently there began to be a crimson glow behind the trees. A chant, barbaric, weird and wonderful, without drumbeat or accompaniment, repeating and repeating one refrain, swelled through the trees as the crimson glow grew nearer.

Tros rose to his feet, but the druid and the others remained seated, the woman watching Tros as if she contemplated springing at him, although whether for the purpose of killing him, or not, was not so evident. Conops watched her equally intently.

It looked as if the forest was on fire, until men bearing torches appeared in the mouth of the glade, and a long procession wound its way solemnly and slowly toward the rock. The others stood up then and grouped themselves behind Tros and the druid, the druid throwing back his head and chanting a response to the refrain, as if it were question and answer. The woman took her husband's hand, but he appeared hardly to notice it; he was more intent on watching the approaching druids, his expression a mixture of challenge and dissatisfaction. He began to look extremely dignified.

There were a dozen druids, clad in long robes, flanked and followed by torchbearers dressed in wolf-skin and knitted breeches. They were led by an old man whose white beard fell nearly to his waist. Five of the other druids were in white robes, and bearded, but the rest were clean-shaven and in blue; all wore their hair long and over their shoulders, and no druid had any weapon other than a sickle, tucked into a girdle at the waist. The torchbearers were armed with swords and spears; there were fifty of them, and nearly as many women, who joined in the refrain, but the old High Druid's voice boomed above all, mellow, resonant and musical.

The procession was solemn and the chant religious; yet there was hardly any ceremony when they came to a stand near the rock and the old druid strode out in front of the others, alone. The chant ceased then, and for a moment there was utter silence. Then the druid who had been acting as interpreter took Tros's right hand and led him toward the old man, moving so as to keep Tros's hand concealed from those behind. The old man held out his own right hand, the younger druid lifting the end of Tros's cloak so as to conceal what happened.

A moment later Tros stepped back and saluted with the graceful Mediterranean gesture of the hand palm outward, and there the ceremony ceased.

The old druid sat down on a stone beside the rock; his fellow druids found places near him in an irregular semicircle; the crowd stood, shaking their torches at intervals to keep them burning, the glare and the smoke making splotches of crimson and black against the trees.

The younger druid spoke then in rapid undertones, apparently rehearsing to the older man the conversation that had preceded his arrival. Then Tros, with his left hand at his back and his right thrown outward in a splendid gesture that made Gwenhwyfar's eyes blaze, broke silence, speaking very loud:

"My father, I know nothing of the stars, beyond such lore as seamen use; but they who do know say that Caesar's star is in ascension, and that nightly in the sky there gleam the omens of increasing war."

The High Druid nodded gravely. The chief let go his wife's hand, irritated because she seemed able to understand all that was said, whereas he could not. The younger druid whispered to him. It was growing very dark now, and scores of shadowy figures were gathering in the zone of torchlight from the direction of the forest. There was a low murmur, and an occasional clank of weapons. Tros, conscious of the increasing audience, raised his voice:

"They who sent me hither say this isle is sacred. Caesar, whose camp- fires ye may see each night beyond the narrow sea that separates your cliffs from Gaul, is the relentless enemy of the druids and of all who keep the ancient secret.

"Ye have heard—ye must have heard—how Caesar has stamped out the old religion from end to end of Gaul, as his armies have laid waste the corn and destroyed walled towns. Caesar understands that where the Wisdom dwells, freedom persists and grows again, however many times its fields are reaped. Caesar does not love freedom.

"In Gaul there is no druid now who dares to show himself. Where Caesar found them, he has thrown their tortured carcasses to feed the dogs and crows. And for excuse, he says the druids make human sacrifice, averring that they burn their living victims in cages made of withes.

"Caesar, who has slain his hecatombs, who mutilates and butchers men, women, children, openly in the name of Rome, but secretly for his own ambition; Caesar, who has put to death more druids than ye have slain wolves in all Britain, says that the druids burn human sacrifices. Ye know whether Caesar lies or not."

He paused. The ensuing silence was broken by the whispering of men and women who translated his words into the local dialect. Some of the druids moved among the crowd, assisting. Tros gave them time, watching the face of the chief and of his wife Gwenhwyfar, until the murmur died down into silence. Then he resumed:

"They who sent me into Gaul, are They who keep the Seed from which your druids' wisdom springs. But he who sent me to this isle is Caesar. They who sent me into Gaul are They who never bowed a knee to conqueror and never by stealth or violence subdued a nation to their will. But he who sent me hither knows no other law than violence; no other peace than that imposed by him; no other object than his own ambition.

"He has subdued the north of Gaul; he frets in idleness and plays with women, because there are no more Gauls to conquer before winter sets in. He has sent me hither to bid you let him land on your coast with an army. The excuse he offers you, is that he wishes to befriend you.

"The excuse he sends to Rome, where his nominal masters spend the extorted tribute money wrung by him from Gauls to buy his own preferment, is that you Britons have been sending assistance to the Gauls, wherefore he intends to punish you. And the excuse he gives to his army is, that here is plunder —here are virgins, cattle, clothing, precious metals and the pearls with which he hopes to make a breastplate for the Venus Genetrix.

"Caesar holds my father hostage against my return. I came in Caesar's ship, whose captain, Caius Volusenus, ordered me to show him harbors where a fleet of ships might anchor safely, threatening me that, unless I show them to him, he will swear away my father's life on my return; for Caius Volusenus hopes for Caesar's good-will, and he knows the only way it may be had.

"But I told Caius Volusenus that I know no harbors. I persuaded him to beach his ship on the open shore, a two days' journey from this place. And there, where we landed with fifty men, we were attacked by Britons, of whom one wounded me, although I had not as much as drawn my sword.

"Your Britons drove the Romans back into the ship, which put to sea again, anchoring out of bowshot; but I, with my man Conops, remained prisoner in the Britons' hands—and a druid came, and staunched my wound.

"So I spoke with the druid—he is here—behold him— he will confirm my words. And a Roman was allowed to come from the ship and to take back a message to Caius Volusenus, that I am to be allowed to speak with certain chiefs and thereafter that I may return to the ship; but that none from the ship meanwhile may set foot on the shore.

"And in that message it was said that I am to have full opportunity to deliver to you Caesar's words, and to obtain your consent, if ye will give it, to his landing with an army before the winter storms set in.

"Thus Caius Volusenus waits. And yonder on the coast of Gaul waits Caesar. My father waits with shackles on his wrists. And I, who bring you Caesar's message, and who love my father, and who myself am young, with all my strength in me, so that death can not tempt, and life seems good and full of splendor—I say to you: Defy this Caesar!"

He would have said more, but a horn sounded near the edge of the trees and another twenty men strode into the clearing, headed by a Gaul who rode beside a Briton in a British chariot. The horses were half frantic from the torchlight and fear of wolves, but their heads were held by men in wolf-skin who kept them to the track by main strength. Conops plucked at the skirt of Tros's tunic:

"Commius!" he whispered, and Tros growled an answer under his breath.

The two men in the chariot stood upright with the dignity of kings, and as they drew near, with the torchlight shining on their faces, Tros watched them narrowly. But Conops kept his one bright eye on Gwenhwyfar, for she, with strange, nervous twitching of the hands, was watching Tros as intently as he eyed the stranger. Her breast was heaving.

The man pointed out as Commius was a strongly built, black-bearded veteran, who stood half a head shorter than the Briton in the chariot beside him. He was dressed in a Roman toga, but with a tunic of unbleached Gaulish wool beneath. His eyes were bold and crafty, his head proud and erect, his smile assuring. Somewhere there was a trace of weakness in his face, but it was indefinable, suggestive of lack of honor rather than physical cowardice, and, at that, not superficial. His beard came up high on his cheek-bones and his black hair low on a broad and thoughtful forehead.

"Britomaris!" cried the driver of the chariot, and he was a chief beyond shadow of doubt, with his skin stained blue and his wolfskins fastened by a golden brooch—a shaggy-headed, proud-eyed man with whipcord muscles and a bold smile half-hidden under a heavy brown moustache.

The husband of Gwenhwyfar stood up, dignified enough but irresolute, his smoldering eyes sulky and his right hand pushing at his wife to make her keep behind him. She stood staring over his shoulder, whispering between her teeth into his ear. The chief who drove the horses spoke again, and the tone of his loud voice verged on the sarcastic:

"O Britomaris, this is Commius, who comes from Gaul to tell us about Caesar. He brings gifts."

At the mention of gifts, Britomaris would have stepped up to the chariot, but his wife prevented, tugging at him, whispering; but none noticed that except Tros, Conops and the druids.

At a signal from the other chief a man in wolf-skins took up the presents from the chariot and brought them—a cloak of red cloth, a pair of Roman sandals and three strings of brass beads threaded on a copper wire.

It was cheap stuff of lower quality than the trade goods that occasional Roman merchants brought to British shores. Britomaris touched the gifts without any display of satisfaction. He hardly glanced at them, perhaps because his wife was whispering.

"Who is here?" asked Commius, looking straight at Tros.

At that Conops took a swift stride closer to his master, laying a hand on the hilt of his long knife. Gwenhwyfar laughed, and Britomaris nudged her angrily.

"I am one who knows Commius the Gaul!" said Tros, returning stare for stare. "I am another who runs Caesar's errands, although Caesar never offered me a puppet kingdom. Thou and I, O Commius, have eaten leavings from the same trough. Shall we try to persuade free men that it is a good thing to be slaves?"

The chief who had brought Commius laughed aloud, for he understood the Gaulish, and he also seemed to understand the meaning of Gwenhwyfar's glance at Britomaris. Commius, his grave eyes missing nothing of the scene, stepped down from the chariot and, followed by a dozen men with torches, walked straight up to Tros.

His face looked deathly white in the torch glare, but whether or not he was angry it was difficult to guess, because he smiled with thin lips and had his features wholly in control. Tros smiled back at him, good nature uppermost, but an immense suspicion in reserve.

Gwenhwyfar, clinging to her man's arm, listened with eager eyes and parted lips. Conops drew his knife clandestinely and hid it in a tunic fold.

"I know the terms on which Caesar sent you. I know who is hostage for you in Caesar's camp," said Commius; and Tros, looking down at him, for he was taller by a full hand's breadth, laid a heavy right hand on his shoulder.

"Commius," he said, "it may be well to yield to Caesar for the sake of temporary peace—to give a breathing spell to Gaul—to save thine own neck, that the Gauls may have a leader when the time comes. For this Caesar who seems invincible, will hardly live forever; and the Gauls in their day of defeat have need of you as surely as they will need your leadership when Caesar's bolt is shot. That day will come. But is it the part of a man, to tempt these islanders to share your fate?"

"Tros, you are rash!" said Commius, speaking through his teeth. "I am the friend of Caesar."

"I am the friend of all the world, and that is a higher friendship," Tros answered. "Though I were the friend of Caesar, I would nonetheless hold Caesar less than the whole world. But I speak of this isle and its people. Neither you nor I are Britons. Shall we play the man toward these folk, or shall we ruin them?"

The crowd was pressing closer, and the chief in his chariot urged the horses forward so that he might overhear; their white heads tossed in the torchlight like fierce apparitions from another world.

"If I dared trust you," Commius said, his black eyes searching Tros's face.

"Do the Gauls trust you?" asked Tros. "Are you a king among the Gauls? You may need friends from Britain when the day comes."*

[* Caesar made Commius king of the Atrebates, half of which tribe lived in Britain and half in Gaul. There is no historic record, however, of the British Atrebates having accepted Commius as king.]

"You intend to betray me to Caesar!" said Commius, and at that Tros threw back his shock of hair and laughed, his eyes in the torchlight showing more red than amber.

"If that is all your wisdom, I waste breath," he answered. Commius was about to speak when another voice broke on the stillness, and all eyes turned toward the rock. The old High Druid had climbed to its summit and stood leaning on a staff, his long beard whiter than stone against the darkness and ruffled in the faint wind—a splendid figure, dignity upholding age.

"O Caswallon, and you, O Britomaris, and ye sons of the isle, hear my words!" he began.

And as the crowd surged for a moment, turning to face the rock and listen, Gwenhwyfar wife of Britomaris came and tugged at Tros's sleeve. He thought it was Conops, and waited, not moving his head, expecting a whispered warning; but the woman tugged again and he looked down into her glowing eyes. She pointed toward the house at the far end of the clearing.

"Thither I go," she whispered. "If you are as wise as you seem fearless, you will follow."

"I would hear this druid," Tros answered, smiling as he saw the point of Conops' knife within a half inch of the woman's ribs.

"He will talk until dawn!"

"Nonetheless, I will hear him."

"You will hear what is more important if you follow me," she answered; and at that, she left him, stepping back so quickly that the point of Conops' long knife pricked her and she struck him angrily, then vanished like a shadow.

Tros strode slowly after her, with Conops at his heels, but when he reached the gloom beyond the outskirts of the crowd he paused.

"Am I followed?" he asked.

"Nay, master. They are like the fish around a dead man. One could gather all of them within a net. Do we escape?"

"I know what the druid will say," Tros answered. "I could say it myself. What that woman has to say to me, I know not. Though it may be she has set an ambush."

Conops chuckled.

"Aye! The kind of ambush they set for sailormen on the wharfsides of Saguntum! A long drink, and then—"

He whistled a few bars of the love song of the Levantine ports:

Oh, what is in the wind that fills

The red sail straining at the mast?

Oh, what beneath the purple hills

That overlean the Cydnus, thrills

The sailor seeing land at last

Oh, Chloe and—"

"Be still!" commanded Tros. "If there were no more risk than that, my father would be free tomorrow! Which way went the woman?"

Conops pointed, speaking his mind as usual:

"That Briton who came in the chariot—Caswallon—fills my eye. But I would not trust Commius the Gaul; he has a dark look."

"He is anxious for his Gauls, as I am anxious for my father," Tros answered. "He hates Caesar, and he likes me; but for the sake of his Gauls he would stop at nothing. He would bring Caesar to this island, just to give the Atrebates time to gather strength at Caesar's rear. Nay, he may not be trusted."

"Master, will you trust these Britons?" Conops asked him, suddenly, from behind, as he followed close in his steps along a track that wound among half-rotted tree stumps toward the cattle fence. Tros turned and faced him.

"It is better that the Britons should trust me," he answered.

"But to what end, master?"

"There are two ends to everything in this world, even to a ship," said Tros darkly; "two ends to Caesar's trail, and two ways of living life: on land and water. Make sure we are not followed."

The dogs barked fiercely as they approached the fence, and Conops grew nervous, pulling at his master's cloak.

"Nay, it is a good sign," said Tros. "If it were a trap they would have quieted the dogs."

He turned again to make sure no one was following. The torchlight shone on the High Druid's long white robe and whiter beard, and on a sea of faces that watched him breathlessly. The old man was talking like a waterfall. They were too far away now for his words to reach them, but judging by his gestures he was very angry and was in no mood to be brief.

"On guard!" warned Conops suddenly as they started toward the fence again, but Tros made no move to reach for his sword.

It was the woman Gwenhwyfar, waiting in a shadow. She stepped out into the firelight that shone through a gap in the fence and signed to Tros to follow her, leading around to the rear of the house, where a door, sheltered by a rough porch, opened toward the forest.

She led the way in, and they found themselves in a room whose floor was made of mud and cow dung trampled hard. There was a fire in the midst, and a hole in the roof to let the smoke out. She spoke to a hag dressed in ragged skins, who stirred the fire to provide light and then vanished through an inner door.

The firelight shone on smooth mud walls, adzed beams, two benches and a table.

"Your home?" asked Tros, puzzled, and Gwenhwyfar laughed.

"I am a chief's wife; I am wife of Britomaris," she answered. "Our serfs, who mind the cattle, live in this place."

"Where then is your home?" asked Tros.

She pointed toward the north.

"When Caswallon comes, we leave home," she answered. "The power to use our house is his, but we are not his serfs."

Gwenhwyfar's attitude suggested secrecy. She seemed to wish Tros to speak first, as if she would prefer to answer questions rather than to force the conversation. She looked extremely beautiful in the firelight; the color had risen to her cheeks and her eyes shone like jewels, brighter than the gleaming ornaments on her hair and arms and breast.

"Why do you fear Caswallon?" Tros asked her suddenly.

"I? I am not afraid!" she answered. "Britomaris fears him, but not I! Why should I be afraid? Caswallon is a strong chief, a better man than Britomaris; and I hate him! He—how strong is Caesar?" she demanded.

Tros studied her a moment. He gave her no answer. She sat down on one of the benches, signing to him and Conops to be seated on the other.

"You said Caesar will make himself master of the world," she remarked after a minute, stretching her skin-clad legs toward the blaze. She was not looking at Tros now but at the fire. "Why did you say that?"

Suddenly she met his eyes, and glanced away again. Conops went and sat down on the floor on the far side of the fire.

Beware the ambitious woman! All things and all men are her

means to an end. All treacheries are hers. All reasons justify her. Though

her end is ruin, shall that lighten your humiliation—ye whom she uses

as means to that end that she contemptuously seeks?

—from The Sayings of the Druid Taliesan

TROS made no answer for a long time, but stared first at the fire and then at Gwenhwyfar.

"Send that man away," she suggested, nodding toward Conops; but Tros scratched his chin and smiled.

"I prefer to be well served," he answered. "How can he keep secrets unless he knows them? Nay, nay, Gwenhwyfar; two men with three eyes are as good again as one man with but two; and even so, the two are not too many when another's wife bears watching! Speak on."

Her eyes lighted up with challenge as she tossed her head. But she laughed and came to the point at once, looking straight and hard at him.

"Commius spoke to me of Caesar. He said he is Caesar's deputy. He urged me to go with him and visit Caesar. Britomaris is a weak chief; he has no will; he hates Caswallon and yet bows to him. Caesar is strong."

"I am not Caesar's deputy, whatever Commius may be," said Tros. "But this I tell you, and you may as well remember it, Gwenhwyfar: A thousand women have listened to Caesar's wooing, and I have been witness of the fate of some. There was a woman of the Gauls, a great chief's daughter, who offered herself to him to save her people. Caesar passed her on to one of his lieutenants, and thereafter sold her into slavery."

"Perhaps she did not please him," Gwenhwyfar answered. And then, since Tros waited in silence, "I have pearls."

"You have also my advice regarding them," said Tros.

Gwenhwyfar waited a full minute, thinking, as if appraising him. She nodded, three times, slowly.

"You, who have lost all except your manhood and the clothes you wear!" she said at last, and her voice was bold and stirring, "what is your ambition?"

"To possess a ship," he answered, so promptly that he startled her.

"A ship? Is that all?"

"Aye, and enough. A man is master on his own poop. A swift ship, a crew well chosen, and a man may laugh at Caesars."

"And yet—you say, you had a ship? And a crew well chosen?"

Tros did not answer. His brows fell heavily and half concealed eyes that shone red in the firelight.

"Better be Caesar's ward, and rule a kingdom, than wife of a petty chief who dares not disobey Caswallon," Gwenhwyfar said, looking her proudest. "Caswallon might have had me to wife, but he chose Fflur. There was nothing left for me but Britomaris. If he were a strong man I could have loved him. He is weak.

"He likes to barter wolf-skins on the shore with the Roman and Tyrian traders. He pays tribute to Caswallon. He does not even dare to build a town and fortify it, least Caswallon should take offense.

"He obeys the druids, as a child obeys its nurse, in part because he is afraid of them, but also because it is the easiest thing to do. He is not a man, such as Caswallon might have been—such as you are."

She paused, with parted lips, looking full and straight at Tros. Conops tapped the dirt floor rhythmically with the handle of his knife. A man in the next room began singing about old mead and the new moon.

"It is a ship, not a woman that I seek," said Tros, and her expression hardened.

But she tried again:

"You might have a hundred ships."

"I will be better satisfied with one."

She began to look baffled; eyes and lips hinted anger that she found it difficult to hold in check.

"Is that your price?" she asked. "A ship?"

"Woman!" said Tros after a minute's silence, laying his great right fist on his knee, "you and I have no ground that we can meet on. You would sell your freedom. I would die for mine."

"Yet you live!" she retorted. "Did you come to Britain of your free will? Where is your freedom? You are Caesar's messenger!"

She got up suddenly and sat down on the bench beside him, he not retreating an inch. Not even his expression changed, but his shoulders were rigid and his hands were pressing very firmly on his knees.

"Do you not understand?" she asked.

"I understand," he answered.

Suddenly she flared up, her eyes blazing and her voice trembling. She did not speak loud, but with a slow distinctness that made each word like an arrow speeding to the mark.

"Am I not fair?" she asked, and he nodded.

Her eyes softened for a moment, then she went on:

"Caswallon was the first and is the last who shall deny me! I can be a good wife—a very god's wife to a man worth loving! Caesar can conquer Caswallon, but not alone. He will need my help, and yours. Caesar made Commius a king over the Atrebates; and what was Commius before that? Caesar shall make me a queen where Caswallon lords it now! And you—?"

"And Britomaris?" asked Tros, watching her.

"And you?" she said again, answering stare for stare. Her breast was heaving quickly, like a bird's.

"Oh, Tros!" she went on. "Are you a man, or are you timid? Here a kingdom waits for you! Yonder, in Gaul, is Caesar, who can make and unmake kingdoms! Here am I! I am a woman, I am all a woman. I love manhood. I do not love Britomaris."

Conops stirred the fire.

"Do you not see that if you are all a woman you must oppose Caesar?" Tros asked. "Then—let Caesar outrage! Let him slay! He will have done nothing, because your spirit will go free, Gwenhwyfar. Caesar plans an empire of men's bodies, with his own—his epileptic, foul, unchaste and hairless head crowned master of them all! Whoso submits to him is a slave —a living carcass. Hah! Defy him! Scorn him! Resist him to the last breath! The worst he can do then will be to torture a brave body till the braver soul goes free!"

His words thrilled her.

"Well enough," she answered promptly. "I am brave. I can defy Caesar. But I need a braver chief to make the stand with me than Britomaris. If Caswallon had taken me to wife—but he chose Fflur—perhaps it was as well—you are nobler than Caswallon, and—"

"And what?" asked Tros.

She answered slowly:

"A bold man now could conquer Britain. The druids—I know them —the druids would support one who opposed the Romans. They fear for their own power should Caesar gain a foothold. The druids trust you. Why? They do not trust me. Tros—Strike a bargain with the druids. Slay Caswallon. Seize the chieftainship, and raise an army against Caesar!"

"And Britomaris?"

"Challenge him!" she answered. "He would run! I have the right according to our law, to leave a man who runs away."

"Gwenhwyfar!" Tros exclaimed, getting up and standing straight in front of her. "It is Caesar, and not I who has the falling sickness! You and I lack that excuse! Know this: I will neither steal a wife from Britomaris, nor a throne from Caswallon; nor will I impose my will on Britain."

She stood up, too, and faced him, very angry.

"Have you never loved?" she asked, and though her eyes were steady, the gold brooch on her breast was fluttering.

"Loved? Aye, like a man!" he answered. "I have loved the sea since I was old enough to scramble down the cliffs of Samothrace and stand knee deep to watch the waves come in! The sea is no man's master, nor a bed of idleness! The sea holds all adventure and the keys of all the doors of the unknown!

"The sea, Gwenhwyfar, is the image of a man's life. If he flinches, if he fails, it drowns him. Is he lazy, does he fail to mend his ship or steadfastly to be example to his crew, there are rocks, shoals, tides, the pirates, storms. But is he stanch, he sails, until he reaches unknown ports, where the gods trade honesty for the experience he brings! I seek but a ship, Gwenhwyfar. I will carve a destiny that suits me better than a stolen kingdom and a cheated husband's bed!"

She reached out a hand unconsciously and touched his arm:

"Tros," she answered, "Caswallon has some longships hidden in the marshes of the Thames. Take me—take a ship, and—"

"Nay," he answered. "Caswallon owes me nothing. He who owes me a good ship is Caesar!"

"And you think that you can make Caesar pay?" she asked. "Take me to Caesar, Tros; between us we will cheat him of a ship! With you to teach me, I could learn to love the sea."

He stepped back a pace or two, would have stumbled backward against the clay hearth if Conops had not warned him.

"None learns to love," he answered. "Love is a man's nature. He is this, or he is that; none can change him. I am less than half a man, until I feel the deck heave under me and look into a rising gale. You, Gwenhwyfar, you are less than half a woman until you pit your wits against a man who loves to master you; and I find no amusement in such mastery. Make love to Britomaris."

She reddened in the firelight, stood up very proudly, biting her lip. Her eyes glittered, but she managed to control herself; there were no tears.

"Shall I bear a coward's children?" she demanded.

"I know not," said Tros. "You shall not bear mine. I will save you, if I can, from Caesar."

Tears were very near the surface now, but pride, and an emotion that she did her utmost to conceal, aided her to hold them back.

"Forgive me!" she said suddenly.

Her hands dropped, but she raised them again and folded them across her breast.

"Forgive me, Tros! I was mad for a short minute. It is maddening to be a coward's wife. I tempted you, to see how much a man you truly are."

Conops' knife hilt tapped the floor in slow staccato time.

"Kiss me, and say good-by," she coaxed, unclasping her hands again.

"Nay, no good-byes!" he answered, laughing. "We shall meet again. And as for kissing, a wise seaman takes no chances near the rocks, Gwenhwyfar!"

Stung—savage—silent, she gestured with her head toward the door, folding her arms on her breast, and Tros, bowing gravely, strode out into darkness. Conops shut the door swiftly behind them.

"If this isle were in our sea, she would have thrown a knife," said Conops, twitching his shoulder-blades. "Master, you have made an enemy."

"Not so," Tros answered. "I have found one. Better the rocks in sight than shoals unseen, my lad! Let us see now who our friends are."

He strode toward the torchlight, where the old High Druid was still holding forth, swaying back and forward on the summit of the rock as he leaned to hurl his emphasis. More chariots had come and horses' heads were nodding on the outskirts of the crowd—phantoms in the torch-smoke.

Tros kept to the deeper shadows, circling the crowd until he could approach Commius and Caswallon from the rear. He was stared at by new arrivals as he began to work his way toward them, but the Britons had too good manners and too much dignity to interfere with him or block his way.

The women in the crowd stared and smiled, standing on tiptoe, some of them, frankly curious, but neither impudent nor timid. Most of them were big- eyed women with long eyelashes and well-combed braided hair hanging to the waist. Nearly all had golden ornaments; but there were slave women among them, who seemed to belong to another race, dressed in plain wool or even plainer skins.

It was a crowd that, on the whole, was more than vaguely conscious of the past it had sprung from.

Glances cast at Tros were less of admiration than expectancy, to see him exhibit manners less civilized than theirs—the inevitable attitude of islanders steeped in tradition and schooled in the spiritual mysticism of the druids; proud, and yet considerate of the stranger; warlike, because decadence had undermined material security, but chivalrous because chivalry never dies until the consciousness of noble ancestry is dead, and theirs was living.

Commius the Gaul, who, when he was not deliberately controlling his expression, had the hard face and the worried look of a financier, was seated beside Caswallon. The chief was standing in the chariot, his gold-and-amber shoulder-ornaments shining in the torchlight. He smiled when he caught sight of Tros, and with a nudge stirred Commius out of a brown study. Commius, adjusting his expression carefully, got down from the chariot, took Tros's arm, and led him to the chief.

"Tros, son of Perseus, Prince of Samothrace," he announced. Caswallon stretched out a long, white, sleeveless arm, on which strange pagan designs had been drawn in light-blue woad. It was an immensely strong arm, with a heavy golden bracelet on the wrist.

They shook hands and, without letting go, the chieftain pulled Tros up into the chariot. Britomaris, from about a chariot's length away, watched thoughtfully, peering past a woman's shoulder.

The old High Druid was talking too fast for Tros to follow him; he was holding the rapt attention of the greater part of the crowd, and it was less than a minute before Tros was forgotten. The old druid had them by the ears, and their eyes became fixed on his face as if he hypnotized them.

But his eloquence by no means hypnotized himself. His bright old eyes scanned the faces in the torchlight as if he were judging the effect of what he said, and he turned at intervals to face another section of the crowd, signing to the torchmen to distribute their light where he needed it.

Moreover, he changed his tone of voice and his degree of vehemence to suit whichever section of the crowd he happened to be facing. There were groups of dark-haired swarthy men and women, who looked consciously inferior to the taller, white-skinned, reddish-haired breed, or, if not consciously inferior, then aware that the others thought them so. He spoke to them in gentler, more persuasive cadences.

Caswallon watched the druid in silence for a long time; yet he hardly appeared to be listening; he seemed rather to be waiting for a signal. At last he lost patience and whispered to a man in leather sleeveless tunic who leaned on a spear beside the chariot.

The man whispered to one of the younger druids, who approached the pulpit rock from a side that at the moment was in darkness. Climbing, he lay there in shadow, and, watching his opportunity when the old man paused for breath, spoke a dozen words.

The old druid nodded and dismissed him with a gesture. The younger druid worked his way back through the crowd to chariot wheel and whispered to Caswallon.

The man with the spear received another whispered order from the chief, and he repeated it to the others. Without any appearance of concerted action, the torchmen began to edge themselves in both directions toward the far side of the rock, until the near side was almost in total darkness.