RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a detail from a public domain wallpaper

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a detail from a public domain wallpaper

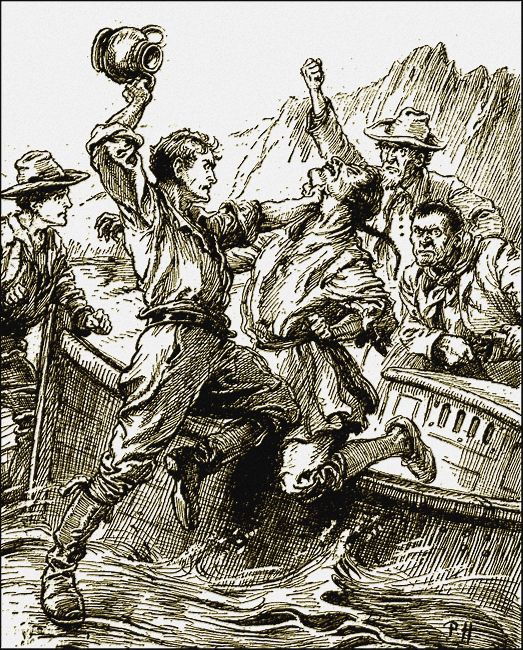

The Fight at the Ring Rock

MALCOLM HART pulled in his line hand over hand. The bait was untouched. He turned to his companion, a square-built young Englishman of about seventeen.

"Say, Joe, this is real funny. There's not a fish biting."

"Nothing funny about it at all, Malcolm," replied Joe Chester, with a grin. "If I was a fish I'm blessed if I'd take the trouble to bite on a night like this. I'd go to the bottom and wait till it was cooler."

"It surely is hot," allowed Hart, who hailed from the rocky coast of Massachusetts. "Not a breath moving, and the air like lead. Do you reckon there's a storm working up?"

"I would if the glass wasn't so steady. She hasn't moved all day. Still, I'm not saying I wouldn't get back to harbour if there was breeze enough."

Malcolm shrugged his shoulders.

"It don't look to me as if we'll get a breeze this side of Christmas. Well, I've done fishing for this night. I'm going below to brew a cup of tea, and then I reckon I'll turn in."

He spoke in rather a depressed tone. Joe Chester turned and laid a hand on his shoulder.

"Buck up, old son! Even if we ain't getting any fish, this is a bit better than sweating among the sugar canes up at Soledad."

Malcolm shivered slightly.

"I'm an ungrateful swab, Joe. You're just about right, and I ought to kick myself good and hard for letting myself drop into the dumps. I reckon it's just the heat and a sort of disappointment that those darned crevalle won't bite."

"That, or a touch of liver," replied Joe in his genial way. "Come on down for that cup of tea. The sharpie's hook is safe in the mud, and the tea'll do us both good."

So the two went below, where they did things with an oil stove and a kettle, and where, in spite of the breathless heat, Malcolm Hart soon recovered his spirits.

The pair were the greatest chums imaginable, and that in spite of the fact that, six months earlier, neither had known of the other's existence. At that time Joe Chester, deluded by a lying advertisement in an English paper, had come out to the West Indian island of San Lucar to make a fortune by growing sisal hemp.

The gentleman who had inserted this advertisement was one Ezra Morse, and a more unpleasant and unscrupulous scamp never trod the rich volcanic soil of San Lucar. His cleverly baited traps were set to catch unwise youngsters whose parents would pay a stiff premium for the pleasure of letting their sons do all the hard and dirty work on his plantation. He housed them vilely, fed them worse, and if they showed signs of rebellion used his bitter tongue and hard fists to cow them into submission.

Some of the pupils kicked; but what could they do? Few had money of their own. Most had been shipped out as "hard cases" or "won't works." They couldn't get away. The end in almost every case was that they knuckled under and became slaves.

But in the end the slave driver, whose name was Mr. Ezra Morse, and who had begun life in Indiana, caught a tartar. Joe Chester was no remittance man. He was a solid young Britisher, with fists as good as Morse's own and a taste for adventure.

When he arrived at Soledad it took him less than twenty-four hours to realise the actual state of affairs. Indeed, if he had not realised the facts for himself, he had Malcolm Hart to put him wise. Hart was his chum from the first. He had never knuckled down like the others, but, not having a red cent to bless himself with, was simply lying low and waiting his chance.

On the third day after Joe's arrival came the inevitable explosion. Joe, after a hard morning's work, came in to find maize meal porridge and bananas for dinner—nothing else.

He kicked. Morse abused him vilely, went for him, and got the shock of his misspent life when he found himself flat on the floor, with more stars buzzing before his eyes than could be seen even in a West Indian sky.

He got up, using horrible language, and Joe knocked him down again. This time his head hit the corner of the table, and he did not rise again.

"Time for us to be moving," said Joe to Malcolm. "Pack your kit and let's shift."

Even Whelan, Morse's big, ugly overseer, did not attempt to interfere, and the two went off together down to Casa Blanca, the coast town where Joe drew some money, and, by Hart's advice, bought a small sharpie, secondhand, and the two set up as fishermen.

On this particularly sultry night the two had been together for about three months, and were making a fair living. There were plenty of fish, as a rule. The trouble was the market, was so poor. They both saw plainly that they would never make a fortune at the game. Still, it was not a bad life.

So far Morse had not troubled them, but they both were very well aware that the fellow had not forgiven them, and was only waiting his chance to get even.

Soon after supper Malcolm turned in—that is, he brought his blankets on deck and went to sleep. Joe imitated his example in so far that he, too, lay down. But the heat was so great that he could not get to sleep. It was not only the heat. There was a peculiar oppression in the air, and at last he got up and went below to the barometer that hung in the tiny cabin. It was still steady, so, feeling somewhat relieved, he lay down again.

It seemed to him that he had barely closed his eyes before he was roused by a thud which jarred the whole boat.

"W-what!" he heard Hart gasp. "Are we ashore?"

"Feels uncommon like it," replied Joe, scrambling to his feet. "Must have gone adrift. No, thank goodness, she's still afloat," he continued in a tone of great relief. "I can feel her move.

"Bring a lantern, Malcolm. It's black as the Pit."

Malcolm was in the very act of plunging below for the hurricane lamp when the sharpie heaved again. It was a most extraordinary motion, and the shock so heavy that both he and Joe were flung down on the deck.

Next moment came a roar like thunder; only it could not be thunder, for there was no lightning. It was followed by a deep, prolonged crash—or, rather, a series of crashes—which seemed to come from the direction of the land.

"Great ghost! It sounds like the end of all things!" said Malcolm in an awed voice. "Must be a tornado."

But Joe had sprung forward, and was hauling frantically at the anchor chain.

"Quick, Malcolm! Give me a hand! It's an earthquake! That was the cliffs falling! We'll get the wave in a minute!"

Suddenly alive to the urgency of the danger, Malcolm jumped to Joe's help. It was too late. Out of the gloom came a heavy, rushing sound like that of a flooded torrent breaking loose down a mountain valley.

"Look out!" roared Joe. "Hang on!"

The words were hardly out of his mouth before they saw, towering over their heads, a great wall of ebony blackness topped with phosphorescent foam.

It was a most unpleasant sight, especially as Joe quite made up his mind that it was the last he was ever likely to observe in this life, a belief which he held for a long, long time as he lay flat on the deck, clinging to a ring bolt, while half the Caribbean Sea appeared to roar in thunder over his head.

He was so surprised when it passed and he found himself above water and still alive that it was some seconds before his brain could grasp anything else. Then he remembered Malcolm, and yelled for him.

To his great relief, he heard a hoarse answer:

"Here I am, Joe! But she's gone in! She's sinking!"

THERE was no doubt about that fact. With the hatch wide open, the sharpie was practically full of water, and her decks were already level with the sea. The next wave—and there were probably more to come—and down she would go.

Joe scrambled wildly aft. Next moment Malcolm heard him sing out that the dinghy was still there and that he wanted help to launch her.

The dinghy was one of those collapsible affairs, and by an amazing stroke of luck had not been washed away. Groping in the Egyptian blackness, the two of them somehow got the lashings off her, opened her out, and just as another great surge came rolling up, tumbled in and got her head to it.

If the wave had been as big as the first she must have been swamped. Luckily, it was a minor edition, and they rode it out in safety, and so they did with two or three smaller successors. But as for the sharpie, the second wave did for her, and down she went, carrying with her practically every single thing that her owners possessed.

"Poor luck, old son," observed Malcolm in a serious tone.

"Poor luck!" echoed Joe. "Malcolm, you're an ungrateful beggar. If ever two chaps ought to have been drowned it was our two selves. And here we are safe in a boat, with the beach only a mile away."

But Malcolm was not to be comforted.

"Life's cheap. We've lost everything else we'd got. Looks like we'll have to go back to work for Morse. And as for the beach, it might be a million miles away for all we can see of it."

"The water's calm, anyhow, and the 'trembloe' is over. Buck up! We'll find the shore all right."

"You'll be clever if you do," retorted Malcolm. "There's a fog coming on to improve matters."

It was true. A thick mist, like steam from a kettle, was rolling up off the surface of the sea. Joe put his hand down into the water.

"Small wonder," he said dryly. "It's cold as ice—or near it. The earthquake has turned the sea upside down and put the bottom layer on top. At least, that's the way I see it."

"I reckon that's about the size of it," answered Malcolm, his teeth suddenly beginning to chatter. "Gee, but it is cold! Let's have the sculls for a bit. We'll have to keep pulling if we don't want to freeze."

Pull they did, taking the sculls in turn. But the mist was thick as a London fog, and they had not the faintest notion of their whereabouts. For all they knew to the contrary, they might be rowing straight out to sea.

How long this sort of thing went on they had no means of judging. Malcolm spoke at last.

"It's getting warmer, Joe. Feel it?"

"Yes; I've been noticing it. Cold water is sinking and the warm rising again. Wish we could see something."

"Must be near dawn. Doesn't seem to me quite so dark," said Malcolm. He paused, straining his eyes through the mist. "Look over there, Joe!" he continued presently. "Isn't that land?"

"Can't say," replied Joe, who was rowing; "but it does seem a bit blacker than the rest of our surroundings. Anyway, we'll have a look."

Turning the little boat, he pulled towards the dark blot that was all they could distinguish through the surrounding gloom.

"It's land all right!" exclaimed Malcolm presently. "The island, I suppose—or what's left of it. Go slow, Joe. We don't want to bump into it."

Joe slackened his pace, and the boat drew slowly nearer to what they could now see was a low ridge of bare rock. The sea, now perfectly calm, made faint sucking sounds as the slow swells broke into the hollows and crannies of the reef.

A sickly yellow dawn was just beginning to break through the heavy fog wreaths.

"It's an ugly looking morning," said Malcolm.

"And an ugly looking coast," added Joe. "I'd like to know where the mischief we've got to."

The mist rose a little. The rock in front showed bare, black as coal, and dripping wet.

"It don't look like any part o' San Lucar I ever saw," growled Malcolm.

"I don't believe it is the island at all," remarked Joe. "Looks to me like we've struck some little key off the coast."

"Well, here's some sort of opening," said Malcolm. "Shove along in and let's see where we're at."

Joe sculled in through a break in the gloomy looking reef. The fog seemed to be breaking. The light grew stronger, and suddenly Joe cried out sharply:

"Look at that!"

"What in blazes—" gasped the other. "Great Scott, Joe, it's Noah's own ark, I believe."

Right in front, dim through the seething vapours, lay a ship, but such a ship as neither had ever before set eyes on. With her towering bow, lofty poop, and queer high sides narrowing upwards to the dock, she was not like anything that had floated for two hundred years. She lay broadside on to them, and the stumps of three masts were visible. Like the rocks, she was black and sodden.

"I reckon she's a ghost ship, Joe," said Malcolm in a voice of awe.

"Rot! She's an old wreck."

"A wreck! Gee! but she's one of those old galleons the Spaniards used to sail. She's just like a picture of one in the Salem museum. How'd she ever stick together all these years?"

"I don't know; but, anyway, we've found her, and if she'll float we'll jolly well take her to port. Man, a craft like that'll be worth thousands to some of those curiosity hunters."

Joe spoke in his calmest, most practical tones, but, all the same, neither he nor Malcolm felt easy as they pulled towards the weird old craft. Neither would have been really surprised if a man in a steel helmet and leather jerkin had put his head over the rail and hailed them.

As they came alongside the dinghy touched something. Joe stuck an oar down.

"Rock!" he muttered. "Jove! she's hard and fast!"

All of a sudden he gave a sort of shout.

"It's all right, Malcolm. I've got it. It's the earthquake. Don't you see?"

"Blamed if I do," answered the other.

"It's plain as pie. The bottom of the sea has lifted and brought her up with it. Now do you understand?"

Malcolm heaved a sigh of relief.

"She ain't a ghost, then, anyhow. Shove alongside, Joe, and let's see what port she hails from."

A curious dank, sour smell pervaded the ancient craft as the boys scrambled on to her slippery deck. Strange weeds and stranger shells and sea growths covered her. But in spite of her long submersion her timbers were still sound.

Joe peered down the black chasm of the hatch.

"Let's go below, Malcolm."

"Let's," echoed Malcolm eagerly. The spirit of adventure was on them both. The doings of the night had prepared them for anything. "Come on, sonny. There was gold in some of these galleons, I've read."

Joe laughed, but inwardly he was keen as the other.

The air below was thick and heavy and hot as a vapour bath. They groped in darkness till Joe remembered his electric, and found, to his delight, it would still work.

They made their way into the main cabin. The walls reeked with slime, and there were inches of soft ooze on the floor. Something cracked under Joe's foot. He kicked it out.

"Ugh!" he muttered, "it's a bone—a man's leg bone."

The furniture had mostly crumbled away.

The locks were still there, but the iron had rusted to a shell. With a kick of his boot Joe burst open the door of a solid cupboard.

"Copper pots," he said. "That looks to be all."

Malcolm stretched out a hand and picked up one of the salt-blackened vessels. It was of a shape such as neither had ever seen before.

"It's wonderful heavy, Joe," he said.

Joe took it from him. His eyes suddenly gleamed.

"It's a sight too heavy for copper," he exclaimed, and taking out his knife, opened it and scratched the side of the tall, vase-like vessel.

The steel cut right into it, and a yellow gleam appeared.

The two stared at one another with startled eyes and parted lips. Joe was the first to speak.

"It's gold, Malcolm," he said in an awed voice. "Solid gold."

Malcolm swiftly picked up another.

"So's this," he said. "Say, Joe, I guess I was about right. With this little lot up our sleeves we won't need to worry about the sharpie."

Joe nodded. He was his practical self again at once.

"Collar all you can carry. We've got to get away with this stuff as quick as we can. As soon as it's light there'll be others after it."

"You bet there will," answered Malcolm. "It's us for the tall timber as fast as we can shin out."

There were seven of the gold "pots." Joe took four and Malcolm three, and it was all they could do to carry them. They weighed on an average twenty pounds apiece. Yet the pace at which those two reached the deck again was something of a record.

The sight that met them was startling. The fog had lifted; it was not gone, but they could see a quarter of a mile in all directions.

And what they saw was this—a ragged reef of bare rocks forming a rough circle around the old galleon, a ring perhaps half a mile in diameter, but with several gaps in it. Of the mainland there was no sign at all.

"Gee! where's the island?" gasped Malcolm.

"Not far away. I'll be bound," Joe answered quietly. "We'll see it when the fog lifts."

He stared round.

"There, I see it!" he exclaimed. "Spot it? Over there! We're all right, Malcolm. Even if the fog shuts down again we know our direction."

He slipped over the side into the dinghy.

"Hand the stuff down, Malcolm," he said.

But Malcolm was staring across in the direction of the mainland.

"There's a boat coming, Joe. A launch, by the look of her. Say, someone else has set their optics on this old barky."

"Don't wait," replied Joe urgently. "We must be away before they see us."

"You're dead right there, partner," said Malcolm, hastily handing down the spoil.

Joe stowed it carefully, and Malcolm dropped over the side. By this time the launch was near enough for them to hear the chug of her engine.

"We'll pull the other way and hide behind the reef," said Joe in a quick whisper.

He set to pulling for all he was worth, making for the nearest opening. But the launch naturally travelled three times as fast as he could pull, and suddenly they heard a shout behind them.

Malcolm gave a queer little gasp.

"Joe, if that ain't Morse, I'll eat him."

"Morse! What would he be doing here?"

"Ask me another. Anyways, it's him."

"Stop, you!"

There was no doubt about it. The voice, harsh and angry, was that of the pupil farmer, and even Joe felt his heart beats quicken. How the man came there he could not guess, but there he was, and all the cards in his favour.

Joe pulled till his sinews cracked, and just then the luck seemed to turn. The fog dropped again, white, wet and warm, like steam from a kettle.

"Go it, Joe," whispered Malcolm. "We'll do 'em down."

Now it was so thick that Joe could no longer see the opening. He was obliged to slacken up. Just as well he did, for next minute the dinghy's bow shot up on a smooth shelf of rock, and she remained hard aground.

"Hang the luck!" he growled; but Malcolm had an inspiration.

"'Vast pulling, Joe. We'll get out and carry her over the reef. That'll puzzle them."

He was out as he spoke.

"Snakes!" he muttered. "Why, the water's hot!"

It was, and so was the reef beyond, up which they tugged the dinghy. Somewhere out in the bubbling mist behind the launch was chugging about like a hound at fault. It was so thick the boys could not see ten yards in any direction.

They dragged the dinghy up a steepish slope of smooth rock, the surface of which was almost hot enough to blister the skin.

Quite suddenly they arrived at the top of it, and Joe only just stopped in time to save going over a sheer drop of twenty feet into the sea beyond.

"Now we've torn it," observed Malcolm. "If the fog lifts we'll be in trouble right up to the neck."

Joe paid no attention. He was hunting for a way down, but could not find one. And just then, of course, up rolled the fog like a curtain off the front of a stage, and there was the launch not a hundred yards away.

There were four men in it. Morse was in the stern, his bully, Whelan, beside him. The other two were yellow men, whose looks were sufficient to hang them on sight.

Morse saw his late pupils as quickly as they saw him, and his laugh was as ugly a sound as either Joe or Malcolm had ever heard.

"Luck, Whelan!" he said in his harsh voice. "Luck's no word for it. No, don't shoot. We'll have a little sport with these two peaches afore we puts 'em through it."

"Lie down, Malcolm," whispered Joe. "Wait till they get near. Then, if they come at us, heave one of those mugs at them."

"Mighty expensive ammunition," groaned Malcolm. "But what you say goes, Joe."

"Sit tight," said Joe calmly. "They may not reach us."

Malcolm was just wondering what Joe meant when the launch, gliding rapidly up, went aground with a spluttering crash on the very ledge where the dinghy had shot up.

The shock flung every mother's son aboard her on their faces.

"Now!" cried Joe, and was down the slope and aboard before Morse and Co. had, any of them, recovered their legs.

Joe had one of the big gold vases in his fist, and a gold vase weighing the best part of twenty pounds is a most efficient weapon at close quarters.

One of the yellow men felt it first, and he never felt anything else afterwards. Then Joe saw Whelan pulling his pistol, and hurled the great vase full in his face. It was a neat shot, and Whelan fell backwards right on top of Morse.

Malcolm was aboard by this time, and was met by half-breed number two, who tried to hit him with a belaying pin. Malcolm ducked neatly. The belaying pin took his hat off, but did no other damage, and next instant its owner landed in the water with a resounding splash.

By this time Morse was up, and if the sea had not been already near boiling point, his language would certainly have raised it the necessary number of degrees. He was quick at the draw, and he got a shot off before Joe could close. But luck was against him. The bullet merely cut Joe's sleeve, and before Morse could pull trigger a second time Joe had him by the throat.

"You murdering blackguard!" roared Joe, for once fairly roused, and shook him till his teeth rattled. "Take his pistol, Malcolm."

Malcolm did so.

"Now, you brute," growled Joe, "what brought you here? Quick, or over the side you go."

"It wasn't you I was after," snarled Morse. "It was the ship. One of the niggers out fishing saw her, and came in with the news. Scared silly he was. Said she was a ghost ship. I knew better. She's the old Santa Rosa, wrecked here in 1698. Full of treasure, they say."

"See here," he went on in a cunning whine, "you've killed two of my chaps, and you'll get into trouble for that with the police ashore. But I'm willing to keep my mouth shut. Give me one of them gold pots, and put me safe ashore, and you won't hear nothing more about it."

Joe laughed out.

"No, you don't, Morse. You don't get round us like that. We'll do our own informing, thank you. For the present it's here you'll go ashore and wait till we've finished up.

"Step lively, please," he continued. "Malcolm, there, doesn't like you one bit, and there's always the chance he might let your gun off suddenly."

Morse raved, swore, threatened, but Joe was adamant. They drove him on to the reef and landed Whelan with him. Then, as the launch was beyond help, they got their dinghy into the water again, loaded up their gold, and pulled away towards the shore.

Malcolm glanced back at the reef, which was fading rapidly in the mist.

"Guess we got our own back, eh, Joe? And, say, the mail steamer's due to-night. What about a run north to little old New York?"

"That'll do for a start," replied Joe, smiling peacefully. "But first I think we'll go and clean out Soledad. Morse won't be back before night, if then."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.