RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old Florida travel poster

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old Florida travel poster

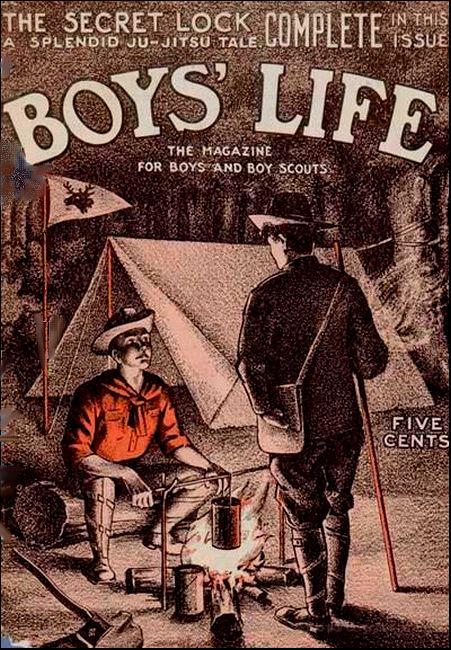

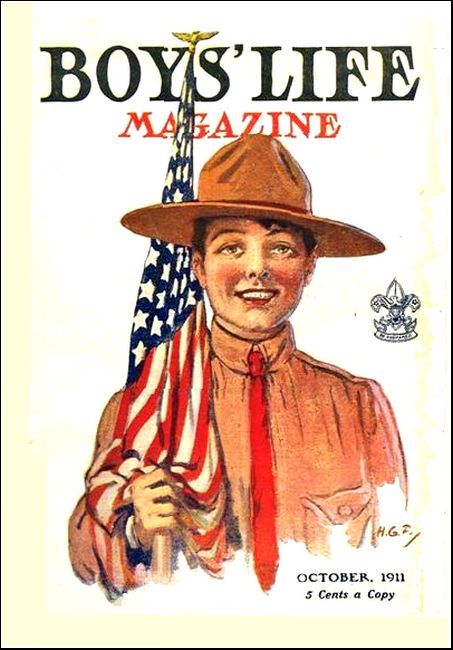

Boys' Life, August 1911, with "Snake Island"

THE breeze blew strong, and the catboat, lying over until the crisp wavelets curled over her lee gunwale, smoked across the sun-lit waters of the gulf. She was sailed with great precision by a brown-faced, square-built boy of about sixteen, who held the sheet in one hand and steered with the other. The rest of the crew consisted of a taller and thinner, but wiry- looking youngster of about the same age who sat amidships, facing his companion, and you might go far before finding a more sturdy capable looking pair.

"That's Turtle Key, Bob," said Tom Carson, the brown-faced boy, pointing dead ahead to where a dull green line lay across the horizon.

"I hope it is," Bob Wickes replied. "If it ain't, it means landing after dark or else spending another night at sea. But this is a rotten chart, and there are about seventeen different keys in a bunch about here, all looking as like one another as so many peas."

"Lindall said that Turtle Key was oval in shape and had an opening in the reef on the west side," said Tom. "If I'm right, the opening will be dead ahead."

"They're all oval, they've all got reefs, and there are no fewer than five with openings on the west," retorted Bob gloomily.

"Don't croak," laughed Tom. "We'll try this one first, anyhow."

The breeze stiffened. The light, flat craft, driven by her enormous sail, seemed to leap from wave top to wave top, and the low green line became more distinct each instant.

"Ha, there's the break in the reef," cried Tom, and letting her off a point or two he drove down towards it at smashing speed. In another twenty minutes the cat-boat flew through a narrow opening edged on each side by tumbling breakers, and speeding across a smooth lagoon was brought up sharp and anchored within a hundred yards of the shore. Tom got the sail down, Rob put the dinghy over the side, and in a very few minutes they had landed on a beach as white as snow and as hard as a billiard table. Spider crabs scuttled in every direction, and the strong breeze rustled harshly in the fronds of the saw palmettos which covered the interior of the island.

The boys walked along the beach, looking for a path through the scrub. Lindall the old pearler upon whose business they had come, had told them where to find the track.

All of a sudden a dog barked, and a large, ugly, yellow hound came running out of the scrub. At sight of the boys the brute stood still, growling angrily, showing a formidable mouth full of white teeth.

"My word, there's some one on the island!" exclaimed Tom, pulling up short.

"It can't be Turtle Key then," added Bob. "Lindall said it was uninhabited because there was no water on it. But here he comes. Great Scott, what an ugly-looking beggar!"

The man who followed the dog out of the scrub merited Bob's opinion. He was very tall, and stooped badly. His face was the sickly yellow of the true clay-eating "cracker," or white native of the Keys, and he had a wide mouth ornamented with half a dozen decayed stumps of teeth. His nose was broken and twisted to one side, he had no eye-brows, and his tow-colored hair fell over the collar of his ragged shirt. This shirt and a pair of old jean trousers were the only clothes he wore, but he carried a heavy double-barrelled ten-bore.

He scowled when he saw the boys, and shouted angrily: "What be you doing here?"

"May I inquire if you own this island?" replied Tom very politely.

"I don't know as I do," the man answered gruffly.

"Then I presume that we have as good a right here as yourself," answered Tom in his most stately manner.

"I didn't mean no offence, stranger," said the other changing his tone. "Fact is, I ain't seen any one fer so long I gets queer. My name's be Rawlins, an' I'm a-digging phosphate. What may your business be?"

"Is this Turtle Key?" demanded Tom.

"Turtle Key?" repeated Mr. Rawlins. "No, it ain't. It's Shark Island—that's what it's called. Turtle Key lays 'bout twelve miles west o' this."

"Then we need not trouble you further," said Tom. "Our business lies on Turtle Key, so we will wish you good-day."

"Won't you come up to my shack and hev a cup of coffee, lads?" begged the man with seeming cordiality.

"Thank you, we are in a hurry," said Tom, whom the very look of their new acquaintance revolted. "Come, Bob, let's get on."

Twenty minutes later the cat-boat had beaten through the reef and was speeding westwards again.

"Rummiest-looking place I ever saw," observed Bob gloomily.

"You can't see much of it," grinned Tom "It's about as near dark as they make it in these latitudes."

"Don't try to be funny. You know what I mean. It's all grass weeds instead of decent palmettos, and it's got the oddest smell about it."

"I allow it's a bit different from most of the keys," said Tom more seriously, "and it smells musky. Either alligators or snakes. I don't know which. You'd better be careful where you're walking."

"Ouch!" roared Bob at that moment, as he jumped three feet into the air. "I stepped on one. Ugh, the brute! I felt it slime under my foot."

"Only a black snake," comforted Tom. "It would have struck you if it had been a rattler or a copperhead. Look, there's a bit of rising ground in front. We'll pitch camp there and cut some of that scrub to boil our kettle."

"Right you are. It's no fun wandering about this forsaken show in the dark. We'll get to work gaily in the morning, and if we can find the pearls without trouble we ought to be half way home again by this time to-morrow."

While the boys are pitching camp, a word as to the errand that brought them cruising along among the sandy keys off Cape Florida. Tom Carson was the son of a Northerner who had been ruined by the cyclone which destroyed Galveston, and who had taken to pineapple planting at Key West. Bob was an orphan, also from the North, and Tom's great friend. Now, old John Lindall, a famous pearler, had been wrecked on Turtle Key on his way home from a successful expedition, and had buried his "take" in a bottle in a marked spot, as he did not wish to risk the gems being stolen by the nigger sponge fishers who took him off. Arrived back at Key West the old man had had a fall and broken his leg. He knew that the boys were dependable, also that they were badly off, and he offered them a hundred dollars apiece, and the use of his cat boat to fetch the pearls from his cache on Turtle Key.

After they had pitched their tent and cooked their bacon and coffee, Tom carefully collected a pile of ashes and strewed them in a narrow circle round the tent.

"What's that for?" asked Bob in surprise.

"To keep off your creepy friends," said Tom "Snakes won't cross a line of dry ash."

Bob gave a grunt of relief, and in a very short time the two were sleeping the sleep of the tired and well-fed.

Tom fancied that he had been asleep just five minutes when he was roused by Bob digging him violently in the ribs.

"What's up?" he muttered drowsily. "It ain't light yet."

"There's a beastly smell of smoke," answered Bob.

"Bless you and your smells. First musk, then smoke! Do you think we've landed on a volcano?" inquired Tom sarcastically. He sat up. "By Jove, you're right. The scrub's afire."

He was out of the tent in a jiffy, and Bob followed. Dawn was just breaking in the east, but the glow of sunrise was obliterated by a much bigger glare in the west. The tall grass was afire from shore to shore, and bone-dry from six weeks' drought, was burning furiously. As they watched, huge tongues of flame shot up, crackling loudly, and driven by the dawn breeze came rushing along as fast as a man could run.

"Strike the tent," shouted Tom "We've got to skip for it. I'll gather the rest up."

It was done in record time, and with his load slung anyhow over his shoulder, Tom led the way. But he was hardly outside the ring of ashes when with a yell he bounded back, almost knocking down Bob, who was close at his heels.

"What's up?" exclaimed the latter.

"The grass is stiff with snakes!" gasped Tom. "I missed a rattler by a foot. Great Scott, look at them!"

As he spoke the tall brown grass bent and waved as if a gale had struck it, and a perfect army of snakes big and little and of all sorts and kinds came whizzing past. It was a most strange and appalling sight. There were great diamond-back rattlers, cotton-mouth moccasins, upland moccasins, spreading adder king snakes, white oak snakes, grass snakes, black snakes, coach whips—all sweeping by in a mad race to escape the pursuing flames. The place was literally alive with them. No human being could have moved six steps without treading on some deadly reptile whose bite would mean a death of horrible agony.

For a moment the boys were too amazed to move. They stood stock still, staring out at the battalions of writhing serpents, all headed one way and all traveling at amazing speed. They glided over and under one another, all unheeding, and the sound of their passage was like the wind in a dead jungle.

Bob spoke first. "Nice mess this. The fire will be on us in about three minutes."

It was true. It was coming up at terrific speed. Already sparks whirled along high over head, and gusts of fiercely heated air beat upon their faces.

"Between the devil and the deep sea," put in Tom, whose spirits never deserted him.

"Only wish we were in the sea," groaned Bob. "I'm frizzling. What the mischief are we to do, Tom?"

Tom Carson was naturally a resourceful youth, and life on the edge of the Everglades had made him the more so. He whipped out a box of matches and grabbed a handful of the dry grass from inside their safety ring of ashes. In an instant he had lit the bundle, and as it flared up he scattered it in front of them. At once the thick stuff to leeward was blazing.

"Are you mad, Tom? You'll roast us," gasped Tom.

"Better roast than burn," said Tom significantly. "Down on your face. Bob, and pull the canvas over you."

He suited the action to the word. Flinging himself flat on the ground, he pulled his chum down beside him and drew the thick canvas of the tent over them both.

The next two minutes seemed like two hours. Waves of burning air passed over the boys. On all sides was a crackling inferno of fire. They gasped pitifully, their lungs filling with hot, choking smoke. The fire coming up from windward was terribly near and sparks fell like rain, setting the canvas smouldering in a score of places.

But Tom's manoeuvre had saved them. Suddenly he jerked Bob's arm, "Come on!" he cried. "Leave the tent. It's done for."

They struggled to their feet and rushed forward into the bare black space which Tom's fire, now roaring away to leeward, had already filled with the charred remains of snakes. Some were not yet dead, and they had to move cautiously to avoid these dreadful coils of scorched and writhing flesh.

The smoke beat down in blinding clouds, and both boys felt as though they must choke. Their throats were parched and they coughed dreadfully. They followed as closely as possible in the track of the second fire.

At last, just as both felt as though another step was impossible, they came upon a small pool of clear water. It was quite free from snakes. None had lived to reach it. They staggered into it and fell on their hands and knees, lapping up the cool water like two big dogs. There they stayed until the fire behind, meeting the already burnt ground, died out, and the smoke clouds drifted out to sea, where they hung, fog-like, dimming the radiance of the new-risen sun.

Tom stood up and peered about. "The grass didn't catch fire by itself," he said meaningly.

The next moment he dropped down again. "Lie low, Bob. Here he comes, and I'm a Dutchman if it ain't our friend Abe Rawlins!"

"Rawlins!" echoed Rob in amazement. "What's he up to here?"

"No good, you bet. The beggar's got his gun, too."

"And ours in the boat," exclaimed Bob. "Hadn't we better make a bolt for it?"

"Shouldn't wonder," said Tom. "He's bound to find us here. Come on."

If they had had any doubt of the cracker's intentions, these were dissipated at once.

With a yell the man started after them. It was nearly half a mile to the boat, the boys were in no shape to run, and Abe Rawlin's legs were long. He gained rapidly.

Crack! and a charge of buck-shot whistled viciously overhead.

"Down!" roared Tom, and pulled Bob to the ground just in time to save them from a second and better-aimed shot.

"Now, while he's loading again," and Tom pulled his chum up again.

Bob was no sooner up than down again. "I've ricked my ankle," he gasped. "Go on, old chap."

For answer Tom swung him on his back and started running again.

"Drop me, Tom," he heard Bob gasp. "Do drop me! He's going to shoot again."

But instead of the shot there burst forth a yell, a yell so hideous and appalling that almost in spite of himself Tom pulled up and looked round.

Rawlins lay upon the smoking ground, writhing and screaming terribly.

One glance was enough for Tom. "He's been bitten!" he exclaimed sharply, and laying Bob down he ran back.

"I'm bit!" yelled Rawlins. "I'm bit. I'm dying. Whiskey, give me whiskey!"

Tom's first act was to snatch up the man's gun and, blow to pieces a great five-foot half-burnt rattlesnake. Then he put the weapon down out of Rawlin's reach, and turning upon the fellow demanded what he meant by trying to murder them.

But Rawlins only rolled and screamed for whiskey.

Tom took a flask out of his pocket and held it up. "That's whiskey," he said.

The man snatched at it madly.

"No, you don't," said Tom. "First tell we what your little game was. Then I'll give it to you, though you don't deserve it."

Rawlins, his eyes staring, and the sweat dripping from his twisted face, stopped screaming.

"I'll tell you," he cried. "But for any sake, a drop first, or I'll die."

Tom poured a little into the cup and gave it to him. Rawlins swallowed it and hungrily eyed the flask.

"Quick!" said Tom.

Rawlins gasped out the story. He had heard of the pearls from a survivor of the wreck. Suspected they were hidden, had stolen a boat, gone to Turtle Key, the island where they had first seen him, and begun searching. When the boys came he had guessed their errand, directed them to the wrong island, and then followed them, resolved if the snakes had not finished them to do so himself.

"That's all, so help me," he ended, and stretched out his hand for the flask.

"You brute!" said Tom with loathing. "You deserve to be left to die here. But a promise is a promise. Here's the flask, and here's what's more likely to cure you." He took out a little syringe.

"Hold out your arm."

Rawlins, utterly cowed, obeyed, and the boy pricked a vein and forced the contents of the syringe into it.

"That's a solution of permanganate," he said. "Now, tie this handkerchief tight round your leg above the bite, and you'll be all right. Now I'll leave you some water and grub, and you can take your chance."

Before night the boys had revisited the real Turtle Key, secured the pearls, and were well on their way home. Old Lindall was delighted when he heard their story and received his pearls safe. He not only gave them the promised reward, but also presented them with the cat-boat. With this, the enterprising pair went into the coasting trade, a business which later on led them into several curious adventures, as we shall relate.

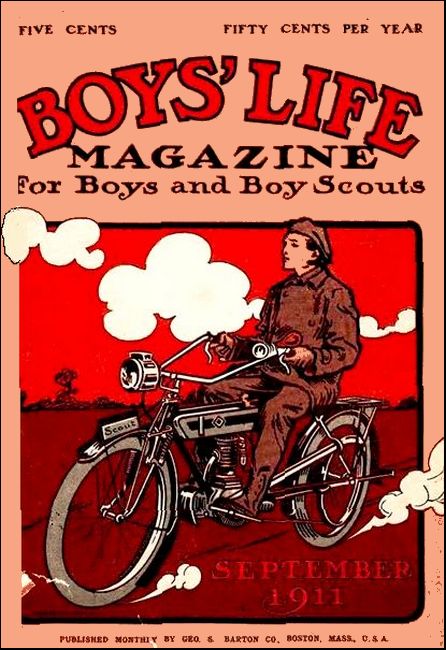

Boys' Life, September 1911, with "The Vampire of the Sea"

"HULLOA, where are the boats!" exclaimed Tom Carson, as the Lindall, lying deep in the water, came tearing under a full press of sail into the Key Blanco lagoon.

"There's no one on shore, either!" added Bob Wilkes, in tones of amazement.

"What in the world is up?" said Tom. "There's been no storm."

"Wouldn't have hurt them if there had," answered the other. "They'd have easily run back into the lagoon."

"Anyhow, there's no one here now," growled Tom. "A nice business for us!"

The two boys had good reason to be troubled. They were using the cat-boat which Lindall the pearler had given them to carry stores to a new sponge-fishing settlement on Key Blanco, and had already made three trips with fair profit. This fourth voyage marked the beginning of a new venture. Besides the usual cargo of pork, beans, bacon and sugar, the boys had aboard about two hundred dollars' worth of clothes, tobacco and odds and ends which they hoped to sell at good profit to the negroes, who were busy on the new sponge ground. These goods they had bought on credit, so their dismay may be imagined at finding the boats gone and no one in sight on the beach.

They ran their boats close inshore, got out the dinghy and rowed to the beach. But hut after hut proved empty. The boys were utterly mystified, for a fortnight before there had been quite eighty men on the island.

They reached the last of the palmetto-thatched shacks. Tom pushed aside the canvas curtain at the door. As he did so something sprang past him, nearly knocking him over, and with an eerie scream vanished into the scrub. As they stood staring after this strange apparition a weak voice from within called to them.

There, on a bundle of wire grass, lay a colored man whose features Tom remembered. His face was the color of lead and a great blood-stained bandage was wrapped around his leg.

"Why, Cicero, what's the matter?" exclaimed Tom.

"I'm mighty glad to see you, sah!" said the poor fellow hoarsely. "If you give me some water, I tell you all I know."

He nearly emptied the jug which Tom had brought. "I ain't had nothing to eat or drink since they all went away yesterday," he explained apologetically, and Bob Wilkes with an exclamation of pity hurriedly began to rummage for cornbread and bacon.

When the man had ravenously devoured some food, Tom volunteered to dress his leg. The wound was a ghastly one. It looked as though a rusty spear with jagged edges had been driven through the flesh of the thigh and then torn roughly out.

"What on earth did that?" inquired Tom as he deftly washed and bandaged the great gash.

"De sea debbil, sah," replied Cicero.

"Sea devil!" echoed Tom wonderingly, and glanced at Bob.

"No, I ain't crazy, sah, like dat oder nigger, Sam, dat ran out when you come in. He was wid me when de sea devil got me, an' he went plumb out of his mind. It was dis way, sah. I wasn't sponging, but just fishing in de lagoon. All ob a sudden de fish dey stop biting, an' I look over, tinking dere was a shark. But dere wasn't no shark, only something big and black dat rose up to the top of the water as I looked. De next thing I know, de boat just heave right ober, an' Sam an' me am swimming. Dere was another boat close by, and I strike out and catch hold ob de side. Dey was just hauling me in when dere comes a big splash, and de sea debbil jump at me an' hit me, an' dat's all I know till I find myself in here."

"But that wasn't enough to frighten every one off the island!" exclaimed Tom.

"No, sah, but dey tell me dat sea debbil go for annuder boat dat evening an' pull down Jake Simpson, an' yesterday morning he got Scipio French. Den, last night, de old Obi man tell dem if dey stay de debbil get dem all so dey just up sticks and leave in a hurry."

"It's true, sah, ebbery bit!" declared Cicero.

The boys looked at one another. "This is a rum yarn," said Bob Wilkes.

"Must have been a shark," suggested Bob.

"No shark made that wound," declared Tom "Where's the Obi man, Cicero?"

"Don't know, sah, but he lib on de island, so I 'spec' he's somewhere in de bush."

Almost as he spoke the curtain at the door was pushed aside and a skinny old negro with scant white wool and a seamed, repulsive face stepped into the hut.

Although they had never seen the fellow before, the boys did not need to be told that this was the Obi man. His necklace of alligator's teeth mixed with the fangs and rattles of rattlesnakes was plain proof of his trade. These negroes of the Keys, like their brethren in the dark island of Haiti, are steeped in the blackest superstition, and their Obi men still practise the dread Ju-Ju brought generations ago from the swamps of West Africa.

"What yarn have you been telling these fellows?" demanded Tom.

"I ain't told dem nothing," replied the Obi man meekly enough. "Dey all got scared yesterday an' left."

"I know that," answered Tom drily. "But why?"

"Ain't dat man told you?" pointing to Cicero.

"He talks of a sea devil that's hurt him and killed two men. What is it?"

"I'se mighty sure I can't tell you," answered the Obi man. "I reckon it am a shark ob' some kind. I tell you, I wish some one'd catch it, sah, for none of dem niggers am coming back hyar while dat ting's in de lagoon."

Tom stared hard at the old reprobate, but the wrinkled face never changed. "I mean to catch it, or find out what it is," he said sharply.

"I'se got some pork for bait, sah," said the old man eagerly.

"I've got plenty of bait," said Tom. "And rifles, too," he added significantly. "Now you can get back where you came from. We'll look after Cicero."

When the Obi man had slouched away Bob said to his chum. "You were pretty sharp with that fellow. Do you think it was wise?"

"Quite I don't know what lie's playing at, but he's up to some game—that I'll swear. It's too late to do any fishing to-day, but to-morrow I mean to see this sea-devil."

Next morning turned out scorching. The white beach fairly glowed, and the lagoon was a dazzling mirror of silver. There was no wind to move the cat-boat, so Tom took the dinghy, and, rigging a shark hook to a heavy line, baited it with a chunk of pork. He anchored in four fathoms of water and set to work.

But no shark came in sight. Indeed, the lagoon seemed strangely empty, even of the mullet and sheepshead which usually swam there in shoals.

Almost drowsing in the sleepy heat, Tom was rudely roused by a violent jerk at his line. He pulled. No resistance. He glanced over the side. Then, in spite of the heat, he felt his skin creep. He was gazing down deep through the glass-clear water into two enormous eyes placed about two feet apart near one end of a great black mass.

The eyes stared steadily upwards. They were deep green and filled with a hideous unwinking malignity. Gradually Tom made out the outline of the creature to which they belonged. It was lying flat upon the sea bottom and seemed to be nearly as wide as it was long. It reminded the boy of a huge skate he had once seen on a fishmonger's slab, but who ever heard of a skate the size of a large carpet? This thing was eighteen or twenty feet in length and had, besides, a long tail which curved away behind it.

It was black as ink, and two curious twisted horns grew one on each side of its triangular head. A more fearsome-looking monster was never imagined in a nightmare.

This was the creature which had sucked in Tom's bait, and then, aware in some uncanny fashion, that all was not well, had spat it out again. Now it lay and watched the occupant of the little boat floating above it, and the boy felt that the evil beast was planning mischief.

What was he to do? Even if he hooked it he would be helpless. The dinghy would be upset or swamped by the sea-devil's titanic struggles. Certainly he had a lance in the boat, but how could he reach the beast lying so far below him? If only he were in the cat-boat he would be on more level terms. He stood up and shouted to Bob, and saw the latter pull up anchor and get a sweep. But he was half a mile away, and it must be a long time before Bob could bring it up.

He glanced down again The green eyes still glared upwards, but surely their owner was growing larger! Ah, the monster was rising slowly upwards with its huge, bat-like fins.

A chill that was nearly fear crept over the boy—for he suddenly remembered that the creature had deliberately upset Cicero's boat. Was it about to try the same trick? If so, he was at its mercy, for the dinghy was still anchored. There was no time to pull the anchor up. He cut the rope, and with a rapid stroke or two of the oars, drove the boat forward.

The sea-devil saw this manoeuvre and quickened its pace, rising like a great dark cloud. Tom pulled in his oars and snatched up his lance. This was six feet long, and had fifty yards of fine strong line attached to it, and its steel head was keen and deeply barbed.

Next instant the sea-devil broke water two boat's length astern and made a furious rush at the dinghy, Tom caught one glance of a huge shovel-shaped nose with a vast cavern of mouth yawning open below it, and with all his strength drove the lance forwards and downwards. He felt the keen point sink far into yielding flesh, but the wound never stopped the sea-beast's rush. With a grinding crunch the jaws met in the stern of the little craft, cutting a wide gap in the light planking.

Instinctively Tom jumped to the bows and so lifted the stern out of the water. At the same moment the sea-devil swerved and dived, and Tom, seizing an oar, swung the broken stern round just in time to avoid an upset. Even then he did not cut the line, and in another moment the wrecked boat was being towed stern foremost at tremendous speed across the still surface of the lagoon.

Tom heard a shout from Bob, but dared not look around. He had made the line fast round a cleat, but it took him all his time to steer. The devil headed straight for an opening in the reef. Evidently it had got more than it had bargained for, and fancied that it would be safer in the open seas.

Calm though it was, there is always a swell on these coral reefs. Even here, it was all that Tom could do to keep the water from rushing through the broken stern and swamping his little craft. Once outside, nothing could save him from filling and sinking. But the opening was still a long way off. He would not cut till obliged to. The beast might turn before it reached the opening, or Bob might manage to come to his help. He cast a glance over his shoulder. Ah, a catspaw was ruffling the mirror-like surface. Bob had seen it and was getting the sail up.

The sea-devil, swimming a few feet below the surface, tore along with the speed of a motor-launch. Already Tom could hear the dull boom of the surf, and see the foam breaking over the jagged coral teeth of the reef. The brute made straight for the channel.

Still Tom set his teeth and refused to cut the line. The dinghy rose to the send of a swell and the water gushed into her, dashing over Tom's feet. He snatched his knife from the sheath. Too late! At that moment the sea-devil, now actually in the channel, dived headlong. Before Tom could slash the line, the boat was dragged clean under, leaving its occupant struggling in the sea.

The water was tepid, but for a second Tom felt the cold chill of fear. His enemy must be almost exactly under him. He struck out madly for a solitary pinnacle of rock a few yards away. It was nearly high tide, and most of the reef was under water. It seemed a year before he clutched the sharp, ragged coral. It was so small and low that each long, slow swell broke over it, but Tom was never more grateful than when he scrambled upon it. As he gained his feet there was a tremendous commotion in the sea, and the great fish broached and flung itself high into the air, coming down with a crash which sent the water leaping in clouds of spray. Something hissed through the air not a yard from Tom's head. It was the snake-like tail of the monster, and now for the first time the boy realized the nature of the brute with which he was at grips. It was the manta ray, the largest, rarest ray that swims. No sea creature is more dreaded both for its cunning and ferocity, and it is doubly armed, for, besides its shark-like teeth, it has in its tail a great barbed poisoned spike. It was this gruesome weapon which had given Cicero his dreadful wound.

The ray had missed its aim once; it would not do so a second time. The cat-boat, though coming up fast, was still two hundred yards away. Tom glanced round despairingly. He could do nothing but stand there and await his fate. He had nothing but his knife, and what use was that against this whirling sinewy flail with its horrible poisoned barb?

The ray had dived. Tom stared down into the blue, breaking water, each instant expecting to see the great black hulk rush upwards once more. Instead, the boat, which had been dragged clean out of sight, rose, and as it came to the surface it rolled over. Tom saw that the harpoon line was twisted completely round it, and this gave him a gleam of hope, for he knew it must hamper his enemy.

Evidently the ray knew this, too, for next instant it was on the surface and attacking the boat with a mad fury awful to witness. The frail timbers cracked like cardboard in its awful jaws, and the spray flew in sheets.

In a brief period the boat was a litter of fragments and the sea devil, with a final leap which showed its white underside gleaming in the sun, drove these in every direction. In its fury it had broken the shaft of the spear, but the barb was still deep in its ugly head.

Now Tom's turn was coming, but even as the ray, with a lightning-like twist, drove towards him, a heavy report rang out and a charge of buckshot whistled through the air, sending pellets of foam flying all round the ray. Bob had taken the risk of hitting Tom, and fired. Some shot got home, for the ray dived again. But the danger was not over. A few buckshot would not stop this mad beast. Ah! here it came again, making the water boil as it dashed along the surface.

"Jump, Tom!" came a shout. The voice was only a few yards away. Tom jumped with all his might. Alas! the distance was too great. His outstretched hands just touched the side of the boat and he went under.

At imminent risk of wrecking himself on the reef. Bob threw the boat up between the ray and Tom. There followed a terrific crash. With a shock which stopped the boat's way and made her quiver in every plank, the monster's serpent-like tail smacked upon the gunwale. At the same instant Bob drove a lance with all his force into the very centre of the huge black mass.

The keen steel reached the monster's vitals. The ray vanished from sight, and Bob, hastily fending off from the reef, turned and pulled his chum in over the stern.

But the ray was not dead yet. Tom was hardly in the boat, before the great fish broached again. Its whole ponderous form rose six feet into the air, falling back with a crash like that of a cannon shot. Bob snatched up the gun and emptied the other barrel into it as it fell. Then the giant went into its death flurry. Round and round it spun, flinging up blood-stained waves which broke clean over the cat-boat, while the boys watched in awe-stricken silence.

At last its gigantic strength failed, it lay quiet on the surface, and presently began to sink.

"Quick, Bob, a rope!" exclaimed Tom.

Bob handed him a coil of line, Tom made a noose, and, flinging it over the tail of their dead enemy, they presently towed the monstrous carcase back across the lagoon and beached it.

"Now for the Obi man," said Tom with a chuckle, and they fetched him from his hut in the bush.

The knees of the miserable old scamp quaked when he set eyes on the dead ray, but it was not until Tom, who by now had a shrewd suspicion of the real state of things, threatened to throw him into the sea, that he confessed.

He had been bribed by Abe Rawlins, a blackguardly beach-comber, whom the boys had previously encountered, to frighten away the negro sponge-fishers. The Obi man had seen his chance in the panic started by the ray, and taken it. Of course, he had hoped that the beast would easily finish the boys if they dared to attack it.

Tom and Bob tied him fast, threw him into the boat, and left for the neighboring Key, where the sponge-fishers had taken refuge. They soon persuaded the latter to return to work, and having sold their cargo at prices even better than they had dared to anticipate, they loaded up with sponges and sailed away for Key West. As for the Obi man, they left him where they had found him. His reputation was so completely gone that the negroes who had formerly hung on his every word now jeered at him, and he hardly dared show his face in the settlement.

Boys' Life, October 1911, with "The Wreck of the Lugger"

"I DON'T like it," said Tom Carson, glancing back over his shoulder and shifting the tiller so as to bring the laboring cat-boat a little closer to the wind.

"It doesn't look nice," admitted his friend, Bob Wilkes, who had just finished taking a third reef in the big mainsail.

Certainly the look of the sky to windward was alarming. After a still, sultry morning during which the "Lindall" had lain becalmed beneath a blazing sun, heavy clouds had risen, ringing the horizon in every direction, and the wind had begun to blow from the northwest in short, hard puffs. Now, about three in the afternoon, a leaden haze had hidden the sun, and out of the north was rising a mass of cloud so dense and black it seemed as though night were falling. It was already blowing half a gale and a queer, irregular sea was running. The gulf had lost all its usual brilliance and sparkle, and the waves were as dull and yellow as the sky. It was September, perhaps the worst month in the year for storms in this region. Both the boys had an uneasy idea that a cyclone was brewing, but neither of them liked to say so, for if they were caught in a storm of this character both knew that the fate of cat-boat, cargo, and crew was sealed as certainly as though they were drifting over the brink of Niagara.

Bob dived into the cabin and brought up a ragged chart. He had to hold it tightly to his knees, or the wind would have whipped it away.

"There's a key not far to the east," he said.

"Which one?"

"It hasn't a name. Looks like a lot of sandbanks."

"Sure to be. But, I say, Bob, I believe we'd better run for it."

"Right, old chap."

Tom at once let the boat's head off, and with the wind almost astern the sturdy little craft fairly flew over the short waves.

Both boys knew well the heavy risk they were taking. It was no joke sailing a boat even of light draft into an unknown lagoon in weather like this. But anything was better than to be caught in such a gale as seemed brewing.

On they tore, straining their eyes through the gathering gloom for a sight of land. These gulf keys are most of them very low, and hard to distinguish under a loom of cloud.

Suddenly Bob gave a shout, "Boat ahoy!"

"Tom, there's a small boat dead ahead. See?"

"I see. One man in it. He's waving something. In trouble, evidently; we shall have to pick him up. Look here, I daren't throw her up in the sea. I'm going to run as close as I can, and you'll have to grab his painter and make fast. Then we'll get him aboard over the stern."

It was ticklish work, for the wind was hardening every minute and the sea rising. Tom steered magnificently; Bob bellowed directions to the man in the boat. He understood, and flung a rope, which Bob caught cleverly and made fast. It tightened with a jerk, and as her way was checked a sea pooped the "Lindall," drenching her deck.

"Quick, haul him aboard!" shouted Tom.

Bob obeyed, dragging the fellow over the stern and instantly slashing the rope.

"My boat!" howled the rescued man.

"Sit down, you idiot," ordered Torn. "Be jolly thankful you're safe. Do you think we can tow a boat in this sea?"

The man subsided on the deck. Imagine the surprise of the two boys when they recognized the leathery face, straggling beard and little shifty eyes of Abe Rawlins, the disreputable beachcomber who had got them into serious trouble on two previous occasions.

Abe was equally astonished when he saw who his rescuers were.

"I reckon I'm mighty obliged to you gents," he remarked in a rather shame-faced manner. "Where be you making for, if I may be so bold?"

"Shelter," answered Tom curtly.

"Best run fer the lee of Shadow Island," said Abe.

"Is that this key without a name?" inquired Bob, showing it on the chart.

"I reckon," was the reply. "Yew goes round to the south end, and here's the entrance to the lagoon."

Tom glanced at the man sharply. He would not trust him a yard. But they were literally in the same boat at present. Unless he wanted to throw away his own life, the man dared not mislead them. Tom resolved to trust to his guidance.

In a very few minutes a dark line heaved itself up dead ahead. Under Abe's directions, a wide berth was given to the southern end of the island and the vessel ran up under lee of the land. Presently the cat-boat glided into the narrow month of a fair-sized lagoon and was anchored in perfect safety, while the gale screeched wildly but harmlessly overhead.

"Any one on the island?" demanded Tom.

"Two or three friends of mine a-prospecting for phosphate," answered Rawlins. "I wuz out fishing when this here storm came up. Say, I'll hev to ask yew to put me ashore, gents, seeing as my boat's gone."

"All right," said Tom, shortly. He did not trouble to hide his dislike for the ruffian, and was uneasy at the idea of his gang being on the island.

They took Abe ashore in their collapsible dinghy and then, in spite of his pressing invitations to come up to his camp, returned at once to the cat-boat. By this time it was raining in sheets.

"This is rotten luck, Tom," observed Bob.

"It is. The worst of it is, that fellow saw those cases of rifles we've got aboard. He means to have them. I saw it in his eye."

"HOW many men has he?" inquired Bob.

"Half a dozen at least; that nigger Cicero told me last voyage. And yon saw their boat. It's bigger than this. They'll come down on us in the night."

"Nice joke for us," said Rob ruefully, "I don't feel much like staying awake for two nights, and getting knocked on the head at the end. That's what it means, for with this gale we shan't be able to sail for forty-eight hours."

"We must shift our anchorage after dark," replied Tom.

"Only delaying the evil day," grinned Bob. "How about stowing our cargo ashore?" He stood up and stared round. The wind, now a full gale, was clearing the sky, and it was a little lighter. "Halloa, what's that?" he exclaimed, pointing to the far side of the lagoon, where something big and black loomed through the driving rain.

Tom picked up a pair of glasses.

"It's an old wreck. A good, big ship, by the look of it, and tight as wax on the reef. Bob, I think we'll investigate. That may prove the very place to hide our cargo. And if it's sound, I think we'll sleep there ourselves."

Bob agreed. They got out the sweeps, and worked the cat boat over to the wreck. It was the hull of a brig of about two hundred ton, an old ship by her solid build and bluff bows. She was black with weed and barnacles, and in the half light had a curiously sinister and forbidding appearance. As Tom had said, she was jammed hard and fast on the reef, but with the wind in its present quarter she was safe as a house. Tom scrambled aboard, and presently leant over the side and called to Bob that she was sound and dry.

They spent the next hour shifting their cargo from the cat-boat; this done, they moored their boat safe under lee of the reef, and going aboard the wreck in their dinghy, set to work to make themselves comfortable in the deck-house. They were both tired, and it was pleasant to rest out of the wind and rain.

"Now, Bob," said Tom at last, "it's time for supper. Light the oil stove."

Just as Bob rose to obey, there came a heavy thud from below. Both boys started and stood breathless.

"A door banged!" whispered Bob.

"St!" muttered Tom. "Some one's aboard!"

So it was. Footsteps were heard on the companion ladder. It was a curiously heavy and uneven tread.

The boys stood still as mice. Fortunately they had no light in the deck-house. It was not yet full dark, though the sun had set.

Suddenly a voice broke into song. Such a voice! It was like the bellowing of a bull, yet the notes were true and resonant, like those of an organ. The words were those of an old plantation song:

"Gone are de days when my heart was young and gay.

Gone are my friends from de cotton fields away."

And then the figure emerged on deck.

The boys stood appalled.

It was a negro, black as coal. He was at least six feet six inches in height, and his girth fitted his height. Never had they seen such a man. His body was bare from the waist upwards, and the muscles swelled and rippled under the ebony skin. Round his head was a dirty, blood-stained bandage. His eyes rolled oddly, showing the whites, and he planted his feet carefully, as though the deck were rolling instead of solid as dry land. In his waist-belt he carried a heavy axe.

Suddenly he pulled himself up and sniffed as though he perceived something new to him. His song broke off, and he began muttering queerly. Then he stalked off round the deck, growling like some wild animal.

"He's mad!" whispered Bob, horror-stricken.

Even Tom's face was a little white.

"Not a doubt," he answered in the same low tone. "Let's nip out of this. He may come in, and we shall be cornered."

So, as the negro stamped away towards the bow, the two boys slipped through the deck-house doorway and hid behind the stern end of the erection.

Peering round the corner, they saw the giant stumble over the painter of their dinghy. He stooped swiftly, seized the rope, and without troubling to untie it, snapped it like pack thread. The boys, in dismay, watched their little boat drift away. They could do nothing.

"Nice fix this!" muttered Bob.

Just then the negro swung back and came straight towards them.

Torn pulled Bob back. They heard the heavy steps approach and then stop. An instant's extreme suspense. If he had seen or heard them, what earthly chance would they have? But apparently he had not. The deck-house door was kicked back, and the negro went straight in.

"He'll see our things," muttered Bob. They had stored everything in the deck-house.

But if he did, he paid no attention. They heard him fling himself down. Then a grunt of satisfaction, a crunch, and a smacking of lips.

"Our supper," groaned Bob.

"And a good thing, too. Come on?" said Tom. He led the way to the hatch. They hurried down, and passing through the main cabin of the ship, where a pile of dirty rugs showed where the negro had been sleeping, went into the fore-hold. There they hid themselves in pitch darkness amid the musty remains of the rifled cargo.

"He won't find us here," said Tom.

"We can't stick here for ever, though," objected Bob.

"Nothing for it but to wait and see what turns up."

"I only hope the grub will disagree with him," said Bob viciously. He was very hungry and much annoyed.

After an hour's waiting, a burst of deep-toned song proclaimed that the negro had finished his supper. The noise increased. It became a mad roar. There was a thudding that shook the ship.

"He's trying to dance, Tom," said Bob. "He must have enjoyed our supper."

"Yes, and our bottle of brandy," observed Tom drily. "That's what he has got hold of."

Slowly the din subsided. After all had been quiet for an hour or more, the boys crept up on deck. It was blowing as hard as ever, and outside the reef the surf roared fearsomely. It was dark as pitch.

Listening at the deck-house window they heard heavy snores.

"Now's our chance, Bob," said Tom. "We must manage to get our rifles."

He opened the door very cautiously, stepped in on tip toe, and was out in a moment with their two rifles and cartridge belts.

"Shall we tie him?" asked Bob, but Tom said, "Best not try." So, instead, they shut and barred the door, and closed the shutters of the open window, jamming them with a loose spar.

"Now we'd best go below again," advised Tom. "We must get some sleep. I hardly think our friends ashore will pay us a visit tonight."

TOM was wrong. As a matter of precaution, one kept watch while the other slept, and at two in the morning Bob woke his chum, saying he had heard a boat bump against the hull. Tom was up in a second. They loaded their rifles, and waited with beating hearts, at the bottom of the companion.

For some minutes all was still. The only sound was the melancholy whistle of the wind in what remained of the standing rigging, and the hollow boom of the surf on the outer reef.

"Are you sure?" whispered Tom.

"Quite," answered Bob. "There it is again!"

Yes, there was no doubt about it. A slight bump, a rustle, then a sound of gently scuffling feet. Some one was climbing aboard.

"Tom, they'll have our cargo. Hadn't we better get on deck and meet them?"

But Tom, though as plucky a youngster as ever stepped, refused.

"We shouldn't have a ghost of a show, Bob," he said quietly. "They're six to two. Here's my plan. Wait till they're aboard and in the deck-house. Then we'll slip out and bag their boat. If they've left only one man in it, we ought to be able to scrag him. Once we've got the boat, they're helpless. The lagoon's full of sharks, and they won't try to swim."

"I guess not," Bob chuckled gently. "It's a ripping scheme, Tom. You say when."

Another minute and some one was heard tugging at the deck-house door. The boys crawled up the ladder till their heads were level with the deck. Four, five—yes, there were six aboard. One carried a dark lantern, another was trying to open the door. All were armed.

The door seemed to bother them. The man who was pulling the handle suddenly lost his temper.

"I know yew air there, yew two," he snarled. "Open up, or it'll be the worse for yew."

Getting no answer the man put his pistol to the lock and blew it in. And then that rascally lot of beachcombers got the ugliest surprise they had ever had in all their misspent lives. For the giant negro, roused from his tipsy slumbers by the pistol-shot, suddenly sprang to his feet, and seizing the first thing handy, which happened to be a fifty-pound case of rifle cartridges, part of the "Lindall's" cargo, hurled it with frightful force right into the middle of the group.

It struck the man who had fired full in the chest, crushing in his breast bone and hurling him backwards. Before the others had time to realize what had happened, the giant had slipped his arm loose, and with a bellow of fury dashed into the middle of them.

Terrified out of their wits, the gang scattered and fled. The man with the lantern dropped it. It broke on the deck, and the oil flowing out, took fire and flared furiously, casting weird reflections on the wet planking and flying figures. The negro, roaring like a bull, sprang at the nearest man, and with one swing of his keen-edged weapon shore the wretched creature's head clean from his shoulders. A shot rang out and the negro, hit in the head, staggered and fell with a mighty crash.

At this the remaining three gathered courage.

"Kill him!" shrieked one viciously.

Another instant, and a rain of bullets would have pierced the negro's body, but Tom was just in time. He look a snap-shot at the fellow with the pistol just as he was in the act of raising his arm. The bullet caught him in the shoulder, and down he went, with a scream of pain.

"Put up your hands!" roared Tom, as he and Bob sprang on deck.

It was enough. Utterly scared, the remaining pair of ruffians dropped their weapons. Tom kept them covered while Bob went into the deck-house for cord and tied them beyond any possibility of further mischief. One of them was Abe Rawlins.

The man with the wounded shoulder was yelling that he was bleeding to death. But the boys looked first to the negro.

"He saved us," said Tom. "He deserves our help."

They found that the bullet had hit him on the back of the skull, ploughed a deep furrow, and come out. By the light of the expiring oil flames they tied his wound up. Then they dragged him into the deck-house, and lit one of their own lanterns.

There is not much more to tell.

Next morning they marooned Abe and the two remaining members of his gang on the island, taking away their boat. The big negro was sensible again, and so quiet that they could only suppose the wound had in some fashion restored his lost senses. They tended him for two days on the wreck, and then, the gale being over, got him into the boat and proceeded to their destination.

By degrees he entirely recovered. But the odd thing was, he had not the slightest recollection of how he came to be on the wreck, nor of any of the events of his previous life.

The boys never had reason to regret rescuing him, however. Big Ben, as they named him, attached himself to them with a dog-like fidelity and in after times did them yeoman service.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page