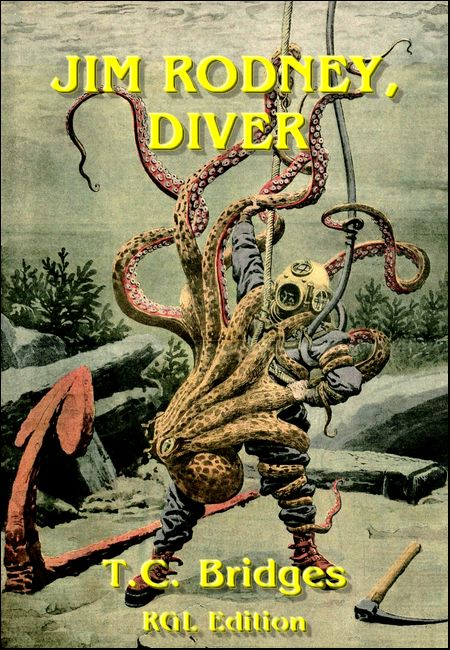

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old French newspaper illustration

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old French newspaper illustration

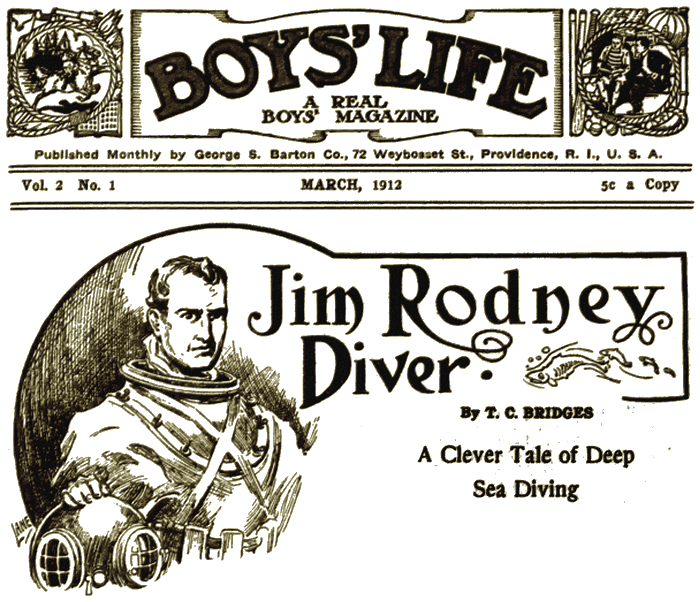

Boy's Life, March 1912, with "Jim Rodney, Diver

HIS work takes the diver to every seaport in the world, and one day in May, 1905, James Rodney, diver, found himself at a loose end in the Peruvian town of Callao.

"Ten years since I was last here," he said to himself as he walked rapidly up the Calla San Sebastian. "Wonder if dear old Nixon will recognize me? Ah, here's the house. Looks just the same as ever."

He knocked at a solid-looking door set deep in a white wall, and a boy of about seventeen opened it and looked at him with frightened, yet defiant eyes.

"Harvey Nixon in?" inquired Rodney. "Tell him his old friend, Jim Rodney, would like to see him."

"Are you Mr. Rodney?" exclaimed the boy, a gleam of hope flashing in his eyes.

"Ay; but what's the matter, lad?"

"Didn't you know? Haven't you heard?"

"Heard what?"

"Father's in prison," answered the boy bitterly.

Jim Rodney stared blankly.

"Good heavens! Why?"

"They say it was he took the pearls—the Magdalena pearls," answered the boy miserably.

"I've only just arrived," replied Rodney "I've heard nothing at all. Let me come in. You must be Joe Nixon, aren't you?"

"Yes, I'm Joe," replied the boy, leading the way in and closing the door. "I'm awfully glad you've come. Father's talked of you lots of times, and was always so pleased when he heard from you."

"Your father was a very good friend to me when I was stranded here years ago," said the diver gravely. "Now, tell me what's wrong, for if there's anything I can do for him, I shall do it."

"You know father has been working for the past two years for the jewelers, Martinez & Campos," began the boy. "He knows how to clean and restore pearls as no one else does, and nearly all the pearls the firm buys pass through his hands."

"Yes, I know," put in Rodney. "He wrote me."

"Well, in March, the Magdalena came in with the finest lot of baroque pearls that were ever seen here. Some of them were over fifty grains weight, and there were two hundred and seventy of them in all. When father brought them here, he locked them up in his safe as usual, meaning to begin work next morning. In the morning I was just coming down when I heard a shout, and there was dad with his face white as a sheet, standing in front of the open safe. The pearls were gone!"

"And you've no idea who took them?" exclaimed Rodney.

"Oh, we know well enough! It was Vibart."

"Vibart! Who is he?"

"An Englishman dad picked up starving here just before Christmas. Good-looking chap, but a regular wrong 'un. Dad was awfully good to him. Gave him money, and found him a job, and let him live in the house. I suspected him at once, and, sure enough, he was gone."

"Where to?" asked Rodney sharply.

"We think he sailed by the San Domingo for San Francisco. She left at seven that morning."

"Didn't you cable to have him slopped?"

"Of course. But we didn't get a reply for a long time, and then look what it says."

He handed Rodney a slip of thin buff paper.

"San Domingo wrecked off Cristobal Island. Total loss. Mate and steward only saved."

"Phew, that's bad! Well, how about these two survivors?"

"They were both brought back here. But the mate's had a knock on the head which has sent him silly, and he can't tell anything, and the steward says there was no one of Vibart's name aboard, nor anyone a bit like him."

"Then how do you know he was aboard?"

"They had one passenger. The steward admits that. He joined the ship just before she sailed, and he had a handbag which he was awfully keen about. He wore a black beard and whiskers, too, just the sort of disguise a clean-shaved chap would go in for."

"Isn't that good enough for the authorities?" inquired Rodney.

"Not it," returned the boy bitterly. "You know how down they are on Americans here. The miserable idiots declare that, even if that was Vibart, he and father were in collusion. As for Martinez & Campos, they are so furious about the loss of their pearls, that they want to take it out of someone—they don't seem to care who."

"Just like those Spanish-Americans!" exclaimed Rodney. "Well, there's only one thing to be done, so far as I can see."

"What's that?" cried Joe Nixon eagerly.

"Examine the wreck."

"I'm afraid that's impossible," said the boy despondently. "They say she struck the cliff-face, and went down in deep water. And even if she can be reached, there's the cost. It would take no end of money. That puts it out of the question."

Rodney looked at the boy sitting there with his head sunk between his shoulders. He thought of his dear old friend stewing in the horrors of the common gaol of Callao among a motley, ill-smelling crowd of negroes, and he took his resolve quickly.

"Joe, I've a nice little sum in the bank—enough to see us through. Will you come with me to Cristobal Island and have a look at that wreck?"

The boy bounded to his feet.

"Do you mean it?" he cried incredulously.

"I generally mean what I say," smiled the diver.

THE dawn broke in molten gold across a sea of polished glass, and against the western horizon Cristobal Island lay like a kneeling camel, its two round backed hills exactly resembling the humps of that desert beast.

"Never saw such a wonderful calm in my life," observed Robartes, the skipper of the small steamer Torch, which Rodney had chartered.

"All the better for our job," returned the diver.

Robartes gazed at the tall, ragged cliffs, which seemed to climb higher and higher out of the sea as the Torch ploughed her way steadily forward across the waveless Pacific. He shook his head.

"That island's the top of a big mountain, Mr. Rodney," be said. "There's more than a mile of water under us at this minute. And they tell me the San Domingo was driven flat on to the face of the cliff there. If that's so, she's far below your reach."

"I've been to thirty fathoms," said Rodney.

Robartes looked at the powerful, square-set figure with a gleam of admiration in his keen eyes.

"There ain't many can say that," he replied. "But as like as not, she'll be lying at three hundred."

"We can but see," answered Rodney simply. "And now for breakfast. I don't mean to waste a minute of this wonderful calm."

"'Twas in this little dent in the cliffs, sir," explained the steward of the San Domingo, as the Torch came slowly up under the rock walls of the island. "The captain steered in there, hoping there was a creek; but there wasn't none, and the poor old barque ran her nose against the rock, and went down under our very feet, so to say. The mate and me got hold of a spar, and was washed up on that bit o' reef over there. That's how we was saved."

Rodney stared hard at the place.

"If there's rock standing up off shore, there'll be more under water," he said. "There's a chance the San Domingo may be within reach."

"I can't get soundings," said Captain Robartes. "We'll have to keep steam up, and cruise up and down. There's no anchorage."

"Right, captain," answered Rodney. "Now, if you'll drop the boat, I'll go close inshore and have a look."

"What's that you've got there?" inquired Joe Nixon, a few minutes later, as Rodney lifted a curious implement that looked like a large, deep saucepan, with a glass bottom.

"A water glass," was the answer. And, motioning to the boat's crew to cease pulling, Rodney laid the glass on the water. "Look through it," he said.

Joe did so, then lifted an astonished face.

"It's wonderful! You can see right down. Why, it looks like a gorgeous flower-garden! And I can see the bottom!"

"Yes," answered Rodney quietly. "I was right. There's a ledge running out from the cliff below water. Not more than ten fathoms of water over it, either. But it's narrow. The only question is whether the San Domingo stuck on it as she sank, or recoiled so far as to drop into the deep over the outer edge. If she did, Joe, she's beyond human reach."

"Let me look," begged the boy.

"Move the boat along very slowly at just this distance from the cliff," ordered Rodney.

The rowers obeyed. Joe gazed anxiously through the water-glass.

Suddenly he cried out sharply. Rodney signalled to stop the boat. Joe, trembling with excitement, handed him the water-glass. "Look!" he muttered hoarsely.

Rodney gazed long and earnestly down into the clear depths. At last he raised his head.

"It's the ship, all right, Joe," he said, "and she's within reach."

Joe gave a cry of joy.

"Don't be too sanguine, boy," said Rodney warningly. "Remember, she's been there for weeks. These tropic seas are full of hungry life. There may be no trace of anything human left in the wreck."

As he spoke Rodney was already beginning to fit on his diving-dress.

Joe, deeply interested, watched his friend gradually disappear inside the huge shapeless envelope of india-rubber, helped to screw the monster metal helmet upon his head, to hang the diver's long-bladed two-edged knife in its sheath on the belt, and to adjust the electric lamp which Rodney wore, fastened on his helmet just above its thick plate-glass front.

Another minute, and the diver had stepped overboard, and silently vanished below the calm surface of the sea.

To the boy who had never before seen a diver descend, the whole business was exciting and perilous to the last degree. He gazed, fascinated, into the green depths where strange-shaped, brilliant colored fish flashed to and fro, and weird weeds stretched long, sinuous branches up towards the calm surface.

To Rodney, who had explored the floors of every ocean from the Atlantic to the Pacific, the descent was commonplace enough, yet even he was struck by the amazing life which teemed on this narrow rock-shelf between the tall island cliff and the abysmal depths beyond.

The tropic sunlight filtering down through the warm emerald tide showed a marvellous forest of brilliant-colored weeds, inhabited by teeming life of every kind, from tiny shrimps and crabs to great goggle-eyed, gaudy fish which either flashed away like frightened birds, or else came nosing doubtfully around him, wondering, no doubt, what new monster was invading their marine garden.

A diver descends slowly, so Rodney had plenty of time to notice these things.

"Only hope there are no big sharks," he said to himself. "By Jove, there might be anything down there!"

And, in spite of himself, he shivered slightly as he gazed into the night-like blackness on the seaward side of the shelf.

What depth there was beyond that shelf no one knew. Cristobal Island is merely the top of a long dead volcano which rises almost sheer from the uttermost abysses of the ocean.

Presently Rodney dropped lightly and silently on to the deck of the lost ship. In spite of the depth—more than the height of a five-story building—he could see quite plainly. The water was clear as green glass, and the boat poised high overhead, and the long, snaky air-tube and life-line descending from it were almost as clear as if hung in mid-air.

The San Domingo was an old square rigger of about eight hundred tons. The first glance showed Rodney how terribly she had suffered in the tempest which had finished her. All her masts were gone, only jagged stumps remaining. Her decks were swept clean as the palm of a man's hand, and her bows were simply pulped by the fearful impact on the iron cliff.

She lay across the ledge, bow close under the sheer cliff, stern almost overhanging the unknown depths to the east.

Her hatches were battened tight, and Rodney thought with a shiver of the feelings of the unfortunates who were below when she struck.

"Drowned like rats in a trap," he muttered to himself, as he set to work to force open the cabin hatch.

It was nearly dark down below there in the waterlogged main cabin. Rodney switched on his electric torch and looked round.

"No bodies here, at any rate," he said. "They'll be in the sleeping cabins, poor things!"

Four cabins opened out of the saloon. Two were open, and Rodney passed to the other two. The door of the first was jammed The water-soaked wood had swollen, and it took the diver some minutes to force it.

When he turned the light inwards its rays fell at once upon what had once been a man. Rodney shivered, and two lines of an old song flashed back into his memory:

"And dreadful the sights that the diver must see

Walking alone in the depths of the sea."

The less said of Rodney's job of searching that horror the better. It was entirely unrecognizable as a man, but the clothes were there. And the clothes were those of a landsman, not of a sailor. Rodney found a large pocketbook with letters in it. Alas! they were mere pulp; not one line of writing legible.

There was nothing else in the clothes except a little silver money, a knife, and some keys. Rodney took the keys and set to examining the rest of the cabin. But it was not until he turned up the mattress in the bunk that he found anything. The water had rotted the mattress so that it fell to pieces when it was lifted, and out from among the hair which floated in every direction fell something heavy and hard. It was a silver watch. On the outside of the case was a monogram "E.V."

"Edward Vibart!" exclaimed Rodney. "Thank heaven, I'm on the right track. This is the man. Now, if I can only find the pearls, Harvey Nixon is saved. Evidently he hid his watch in the mattress that no one might find it, and so identify him. Surely the pearls are in the same place!"

It was an awkward job to search that mattress. The loose hair floated up all round the diver, making it very difficult to see. He had nearly pulled the whole thing to pieces when his heart gave a jump. His bare fingers had met upon something in the shape of an oval package.

Lifting it into the lamp-ray, he gave a sharp exclamation of delight. It was a large envelope of yellow oiled silk, and when he pinched it he could feel the pearls plainly within it.

"Got 'em at last!" he exclaimed, with intense relief. "Poor, dear old Nixon! He'll be all right now. And Joe, too. How delighted the boy will be!"

With nimble fingers he secured the package tightly to his belt, and turned quickly to leave the cabin with its gruesome contents.

He was barely outside when he started back with a shudder of sickening horror.

A long, thin, rope-like tentacle, pale in color and speckled with dark spots was writhing towards him. It had entered by the broken bows, and, passing up through the fo'c's'le, entered the saloon through the forward cabin.

It flashed towards him with a deadly certainty, and before he could regain the cabin door its tip had fastened on his arm with a grip of death.

JIM RODNEY needed no telling what this ghastly thing was. He had seen the octopus before, had once been clutched by a small one when engaged in mending a seawall on the Australian coast.

He had had trouble enough to get free of that, a creature not ten foot from tip to tip of its tentacles.

But this! Never in his wildest dreams had he imagined such a nightmare horror. This one tentacle alone was at least forty feet long. What could its owner be like?

His blood ran cold as he pictured the bloated monster crouching like a titanic spider in the sea tangle under the black overhang of the cliff.

Out flashed his knife, and with one fierce cut he had slashed through the leathery tip. It shrank back like a wounded snake, and Jim made a dash to reach the deck when he might be hauled up to safety.

Before he was a yard beyond the door another of the living cables came coiling through the dark green gloom, and with paralyzing certainty gripped the right arm, in which he held his knife. Another of the awful things was vaguely swinging overhead, groping along the cabin ceiling.

Swiftly changing his knife to his left hand, Jim Rodney fiercely cut away the second tentacle and bolted back to the shelter of the dead man's cabin. He realized that there and there only he would have the slightest chance of successfully battling with the many-armed monster.

In the main cabin his chances were nothing. Once the awful brute got a fair grip he would be plucked away instantly and presently swallowed alive between the beak-like jaws of this horror of the deep.

He gained the doorway just as the third tentacle fell upon him, and clasping him round the left leg nearly pulled him off his feet. Clutching the doorpost with one arm, he freed himself once more by a swift slash of his razor-edged blade.

Surely the brute would retire now that it had lost the tips of three of its tentacles!

But no. A squid is a very low organism, almost incapable of feeling pain. It was sending in more and more of its sucker-like arms to see what this creature was that was causing it so much trouble. The main cabin was full of the horrible living ropes, coiling and uncoiling like monstrous sea-snakes.

Jim could not shut the door. If he did so he would crush his air-pipe and cut off his supply of air. As it was, his one link with the upper world was in deadly peril of being crushed or broken. Jim Rodney was a very brave man, but the sight before him made him almost sick with horror.

Another of the writhing things passed in through the door and wrapped itself round his waist. He sawed at it furiously, but his knife was getting blunted. Before he could quite sever it, the thick stump of one of the tentacles which he had already cut flashed in and fixed its cup-like suckers across one shoulder.

Horror lent Jim strength almost superhuman, and he shore the loathsome thing away with a desperate sweep. But instantly two more had hold of him. He snatched at the door-frame, but was plucked away as lightly as though a steel cable had him in its grip.

Still he fought like a fury, carving away with deadly, purposeful energy at the living ropes which encircled him.

But the odds were too great. He felt himself being drawn irresistibly away towards the ghastly death which was awaiting him crouched under the shelter of the cliff.

Curiously enough, in that awful moment Jim Rodney's pity was not for himself. It was all for poor Harvey Nixon, now doomed beyond hope to a long period of imprisonment—a punishment which, under Chilian rule, meant something worse than death.

Now he was quite clear of the doorway. He was being dragged out into the centre of the cabin.

And there, at the end of the open passage, was a sight almost too horrible for description. The sea-devil itself was working its colossal, pallid, shapeless bulk through the great gaping chasm of the broken bows. He could see its enormous, black, unwinking eyes fixed upon him, and the chasm of mouth beneath them opening for its prey.

A surge of madness seized him. He gripped his knife savagely. He would at any rate bury the long blade to the hilt in one of those huge, ghastly, expressionless orbs.

Of a sudden a darkness like a black cloud fell across the cabin skylight, and instantly the curling, snatching arms sank away, and Jim Rodney found himself free.

Panting, exhausted, sweating from every pore with his fearful battle for life, the diver staggered back against the cabin table, utterly unable to conceive what had happened. Before he could even form an idea of what had come to his help and caused the sea-devil to shrink back in panic, the black cloud swooped down upon the ship, and a violent rush of water gushing in through the open bows sent him flying over the table and up against the companion.

With what little breath the last shock had left him, Jim signalled violently to be hauled up, and next moment was swung clear of the wreck and dangling like a dead leaf in the swirl of contending currents.

Now he saw for the first time the nature of his rescuer. It was no less than a sperm whale; a small one, truly, not more than forty feet long, but quite a match for the sea-devil.

And, in spite of his battered condition, Jim could have shouted with triumph at the punishment meted to his gruesome enemy.

With vast jaws agape, the whale had driven straight down upon the octopus and shorn off two or three of the hideous tentacles with one snap. The rest closed round the thick, black body, but with a flirt of its mighty flukes the whale tore itself clear and ripped the whole vast, slimly bulk of its prey loose from its enfeebled hold on the rocks and wreck.

Then down it rushed again, worrying the monster as a terrier worries a rat. Even as he watched with fascinated interest, Jim saw the whole monstrous mass of the devil fish melt, torn and ripped to pieces by those shearing jaws.

Then he was at the surface, and the last thing he knew was being hauled into the boat and toppling over in a dead faint in the bottom.

THE story of Jim Rodney and his single-handed battle with the devil-fish lost nothing in Joe Nixon's telling, and popular interest in Callao was stirred so that on his return Jim was the hero of the hour.

It was not a role he enjoyed playing, and he bent all his energies to the immediate release of Harvey Nixon.

When the jewelers, Martinez & Campos, heard that the pearls had been recovered, Martinez himself at once came to claim them.

Jim simply laughed at him.

"These pearls can't be yours," he said, "because yours were stolen, you say, by Harvey Nixon, and he's in prison for it now. Let him out and I'll talk to you."

Result—Harvey Nixon was free the same day.

Martinez again called at Jim's lodgings.

"I want the pearls now," he said.

"Not so fast," retorted Jim. "The pearls are salvage from an abandoned wreck. They are no longer yours at all."

Martinez's yellow face fell dismally. But Rodney's argument was sound in law. The jeweler could do nothing.

"I don't want to be hard on you," said Jim at last, while Joe Nixon looked on with a delighted grin. "You settle the whole cost of my trip to Cristobal Island, my pay as diver for the three weeks, and give Mr. Nixon a thousand dollars compensation for loss of time and wrongful imprisonment, and the pearls are yours."

The jeweler was furious. But the pearls were worth at least ten thousand dollars. There was nothing for it but to pay up, which he did, though with very ill-grace.

With the money the Nixons moved to Buenos Ayres, where they are doing very well in a small jeweler's shop of their own. Jim Rodney spends an occasional holiday with them. But he always flatly refuses to speak of that nerve-shaking conflict with the Terror of the Deep.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.