RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"With Beatty in Jutland," William Collins, London, 1930

"With Beatty in Jutland," William Collins, London, 1930

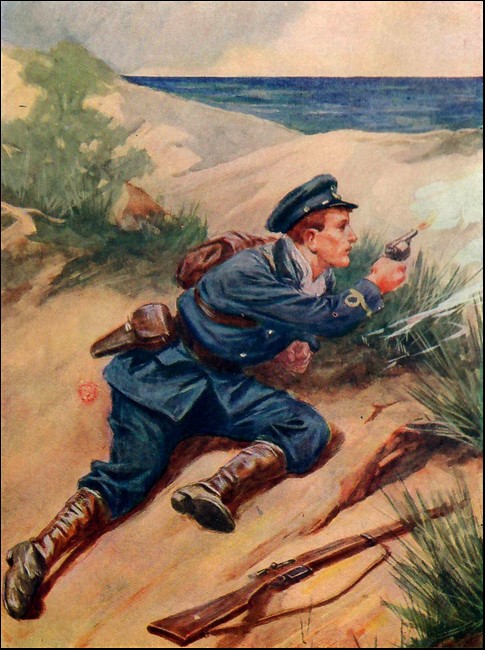

Rodney fired straight into the bush in front.

GUN in hand, Sub-lieutenant Rodney Sterne tramped across the marsh towards Flatsea Creek. The frozen rushes crackled under his feet, the east wind, straight off the North Sea, bit like cold steel, and now and then a few flakes of hard frozen snow came whirling out of the gray canopy above, stinging his face like fine shot.

But Rodney cared for none of these things. Why should he? He was twenty, fit as any man in the British Navy; the blood ran warm in his veins, and this was his first day of a week's long-promised leave. He reached the sea wall, clambered up it, and stood, face to the wind, staring out across the gray waves of the North Sea. He shook his fist at them humorously.

"Blow all you like," he said, with a grin, "you won't get me for another week, so don't think it."

He dropped down quietly on to the saltings, the stretch of muddy marsh ground between the dyke and low water mark, and almost at once a teal rose from a little pool, and went off like a bullet from a gun. Quick as it went, Rodney was quicker. His twelve-bore spoke and the duck dropped with a thud on to the frozen mud.

"Not so bad!" remarked Rodney cheerfully, as he strode forward to pick up the dead bird, but before he had gone ten steps he was brought up short by a loud shout from the dyke above him.

"What the blazes are you doing; What do you mean by it, you infernal poacher?"

Rodney glanced up. A large, heavily-built, hook-nosed man was standing on the top of the sea wall. He had a gun over his shoulder, and was shaking his fist angrily in Rodney's direction.

"Looney!" was Rodney's only comment, and going forward again, picked up his bird, and transferred it to his game-bag.

Heavy boots came trampling through the half-frozen slush behind him. Turning, he confronted the large man who, by the expression on his great, square-jowled face, and the gleam in his small, pale blue eyes, was evidently in a wicked temper.

"Didn't you hear me?" he demanded hoarsely.

"Of course I heard you," replied Rodney, inspecting the other with a cold stare which seemed to add fuel to his fury. "Any one who was not stone deaf could have heard you the other side of the creek. Now, if you're quite done making this horrid noise, perhaps you'll be good enough to go away and play. I'm out to shoot, not to listen to vocal exercises."

The stout man gasped for breath. When he recovered it sufficiently to speak, he burst out again, "You impudent young blackguard! What do you mean by talking to me like this? I'll run you in. I'll have you jailed as a common poacher."

Rodney shook his head pityingly.

"I don't know whether you're mad or drunk," he said, "but you must be one or the other. This is my own land I'm shooting upon—or rather my father's." The other's face changed.

"Who are you?" he asked.

"I am Lieutenant Rodney Sterne, son of Jasper Sterne of Flatsea Holme."

"Where is Mr. Sterne?"

"I don't know that it is any business of yours, but he is in London, and will be back this afternoon."

"When did you come home?"

"You're very fond of questions," said Rodney looking the stranger very straight in the face. "If you must know, I came home last night."

"Then I suppose you haven't seen your father?"

"Not yet."

"That explains your ignorance of the state of things," said the other. "Mr. Sterne has leased Flatsea Island to me, and with it all the shooting and sporting rights."

Rodney stared as though he could not believe his ears.

"Leased the Island," he gasped.

"Yes. The business was only completed last week, and that is no doubt the reason that you have heard nothing about it. My name is Mandell," added the big man in a more conciliatory tone.

Rodney thought he liked the man's civility even less than his boorish rudeness. But he was so flabbergasted at the idea of his father letting the island pass out of his hands that he could hardly think of anything else. Flatsea that had belonged to the Sternes for four hundred years without a break—and to lease it to a stranger! And such a person as Mandell! Why, it was beyond belief. In a few moments, however, he managed to pull himself together.

"I know nothing of this," he said curtly. "I can but apologise for crossing your land with a gun. At the same time, I would point out that these saltings are free to every one. As you no doubt know, the land between high and low tide mark is Crown property, and free to fowlers."

"Not in all cases," answered Mandell. "In some manors there is a special grant of the fore-shore rights to the holder. I have been through the original Flatsea grant, and have discovered that all rights belong to the grantee. Since I hold the lease, they have passed to me, and I am within my rights in stopping all shooting along the shore."

Rodney bit his lip.

"We have never stopped them in four hundred years," he answered.

"Possibly not, but that makes no difference. It is my intention to turn the whole island into a sanctuary for wild fowl, and I regret that I cannot permit even you to shoot here."

"In that case I can, of course, say nothing," said Rodney. "I shall not transgress again." He turned as he spoke and walked quickly away with his gun over his shoulder. His lips were set tightly and all the joy had gone out of his heart.

Mandell watched him go, and a sinister smile twisted his mouth. "No, he'll not trouble me again," he muttered. And then—"Bah!—what fools these English are!"

Reaching home, Rodney went into the smoking-room, flung himself down in a chair, and picked up a paper, but he could not read. His mind was too full of what he had just heard. Never in all the centuries that the Sternes had lived at Flatsea Holme had they parted with an acre of land. There were farms, of course, farther inland, which were held by tenants, but the marsh and the island were part of the demesne, and he and his brother Wilfrid, now in France, had shot over them since they were big enough to carry a gun. The idea of leasing it was almost as incredible as if his father had leased the old gray manor house itself.

The whole thing bothered him terribly. There did not seem any reason for such a proceeding, and if his father had had such an idea in his mind, why had he not let his son know? More puzzling than all was the fact that it had been let to such an obvious cad as Mandell.

Well, there was nothing to do but wait till his father returned. That would be by the train arriving at Ipswich at half-past three. So after luncheon Rodney took the old car, which was the only vehicle they owned, and drove away across the flat, frozen roads to the county town.

The train was punctual, and Rodney met his father as he stepped out of his compartment. He got another shock, for Mr. Sterne looked years older than when his son had last seen him. He had gone very gray, his shoulders were bent, and his face had many new lines.

But his eyes lit up as they fell on his stalwart son, and he gave him both hands, and greeted him cordially.

"I only wish I had been at home to meet you, Rodney," he said. "But I did not get your wire until after I had reached London, and I had business which simply had to be settled at once. Let us get started, and then I will tell you all about it."

It was not until they were out of the town that Mr. Sterne spoke again.

"I suppose you've heard, Rodney?" he said wistfully.

"About Mandell, you mean? Yes, I met the gentleman this morning, and he warned me off the marsh." To save his life, Rodney could not quite keep the bitterness out of his voice.

"My dear Rodney, I can't tell you how sorry I am," replied the elder man. "I would not have had such a thing happen for worlds, if I could have helped it. But it was a choice between that and letting the house itself."

Rodney stared.

"I won't worry you with a lot of business," continued his father. "Here it is in a few words. A large amount of my money was in Rumanian oil. The war has cut off all my income from that investment. I have been left with hardly enough to carry on, and then came a sudden demand for payment of the mortgage which I raised five years ago for the new farm buildings.

"I was at my wit's end when this man Mandell wrote, offering to buy the whole place."

"To buy the place!" exclaimed Rodney.

"Yes. He offered me fifty thousand pounds." Rodney's eyes widened.

"The man's mad!" he exclaimed.

"That's what I thought. It is more than double the value of Flatsea and everything in it. But I told him it was not for sale. Then he offered me five hundred a year for the island and the marsh, if I would give him a five years' lease. What was I to do? I had but forty-eight hours to decide. There was no time to communicate with you or with Wilfred. And anything seemed better than letting the house."

Rodney nodded.

"You were quite right, father," he said quickly. "Don't say anything more about it. After all, five years will soon pass, and long before then we shall have the Huns whipped to the wide, and your Rumanian shares paying hand over fist. Just don't worry any more."

It was a moment or two before Mr. Sterne answered. "You're a good fellow, Rodney," he said, rather huskily. "I am very proud of you, my boy."

"And now," he added presently, "let's think what we can do for the rest of your leave. We must make the most of these six days that are left."

As he was speaking, Rodney had turned the car into the drive under the leafless trees. He got out to close the gate, and just then a telegraph boy came hurrying towards him.

"Telegram for you, sir," he said.

Rodney tore open the buff envelope. His face fell as he read the message, and he turned to his father.

"No use making plans, father," he said ruefully. "I have to re-join at once."

"What!—to-night?" exclaimed his father, in dismay.

"No, but I must get off first thing in the morning. 'Alicon' is in Harwich, and if you'll let me take the car I can get there in a couple of hours."

"Of course you shall have it," declared his father, "but, my dear lad, this is a sad blow. I was so hoping to have you with me for a bit."

Rodney got into the car again and took the wheel. But sorry as he was for his father's disappointment, he was not so sorry for himself. "I couldn't have stuck it," he said to himself. "I couldn't have stood seeing that blighter Mandell bossing around the island as if he owned it."

"HALLO, Totts," said Rodney, as he stepped aboard H.M.S. "Alicon" next morning. "What's up? Have the blighters come out at last? Is the High Canal Fleet at sea?"

Lieutenant Hugh Tottenham turned at sound of the eager voice.

"That you, Sterne? Jove, you haven't wasted much time! But no—no such luck! Dicky Trask has got a tummy-ache and has retired to hospital for the doctors to make up their minds whether they're going to amputate his appendix. That's why we had to call you back in such a hurry.

"I'm sorry, old son," he went on sympathetically. "It's poor luck losing your bit of leave this way."

"Oh, it's all in the day's work," replied Rodney, shrugging his shoulders. "But I hope poor Dicky isn't very bad."

"Don't think there's much the matter with him. I'm going to run over and inquire some time to-day."

"What—aren't we sailing?"

"Hope not. No orders yet, anyhow. Anything's better than the North Sea in an easterly gale."

"Captain's coming aboard, sir," said a quartermaster, stepping up to Tottenham.

Tottenham started slightly.

"By Jove, Sterne," he said eagerly, "that looks like business. He told me he was going to be ashore all day."

The gangway was manned, and a few moments later the smart sailor-like figure of Captain Chesney came quickly up the ladder.

"Ah, you're back, Sterne," he said, with an approving glance at Rodney. "That's lucky."

Rodney burned to ask questions, but a very junior second-lieutenant does not question his skipper.

"Come into my cabin, you two," continued Chesney.

"Something up," whispered Tottenham to Rodney, as the two followed the captain below.

Chesney closed the door of the cabin behind them, and smiled a little as he glanced at the two keen faces.

"Any news, sir?" ventured Tottenham.

"I don't know about news, Tottenham, but I can tell you this much. We sail in an hour, and our orders are to join the rest of our flotilla at a certain spot."

"Then—then—they're out, sir?" exclaimed Tottenham, almost stammering in his eagerness.

"That I don't know," replied Chesney, with decision. "I have no information whatever on the subject. Now send Walthew to me, and carry on."

For the next hour all was hurry and bustle. Liberty men were being brought off in a hurry, and boat loads of soft tack, green stuff and fresh meat being got aboard with a rush. But with that wonderful smartness which is characteristic of the British Navy, everything was stowed neatly away, and at the end of the appointed hour "Alicon" was steaming swiftly out of the harbour mouth, her sharp bows cutting the gray swells and flinging up a feather of foam which gradually increased in height as the revolutions quickened and the smart ship gained speed.

She was one of the new fast cruisers of 3000 tons, good for thirty knots, and carrying two of the latest type six-inch guns and eight four-inch as well.

Tottenham and Rodney shared the watch, and as they stood together behind the canvas dodger on the lofty bridge they divided their time between vain efforts to keep warm and talk.

"The owner's got something up his sleeve," observed Tottenham. "I'll lay the watchers have sent news of some sort.

"Another raid on?" suggested Rodney.

"Shouldn't wonder. And yet I don't know. There's no fog, and those beggars think twice before they venture out in clear weather."

"May be fog the other side for all we know," said Rodney. "The wind's dropped a lot since yesterday."

Tottenham nodded.

"That's so. But the beggars will bunk back if they run into clear weather. They're scared stiff of being caught by the battle cruisers."

Rodney chuckled.

"They are that. Gad, I'd give something to see David get on to them. I'll lay he'd teach 'em a thing or two."

"Phew, isn't it cold?" he added, as he swung his arms vigorously across his chest in an effort to restore circulation.

Tottenham shivered. "There's nothing made yet in the way of clothes that will keep out an east wind on the North Sea," he replied. "I've got two vests on and a sweater, and they're about as much use as brown paper."

There was silence a while. "Alicon" was not running straight out into the North Sea. Her course had been changed, and she was travelling almost due north, parallel with the coast.

"We shall pass your place, shan't we?" said Tottenham, after a while.

"Looks like it," replied Rodney, straining his eyes in the direction of the land. "Yes, by Jove, see that tower? That's our village church. And that's the island and the old lighthouse. You can't see the house because of the trees."

Tottenham and he stared hard at the low coast line from which they were separated by hardly two miles of sea. The wind had fallen light, and the clouds had broken. A pale gleam of wintry sun brightened the steel gray surface of the water.

Just then faint chimes came to their ears.

"What's that?" asked Tottenham. "It's not Sunday, is it?"

"No," replied Rodney with a smile. "It's not Sunday, but it's our church bells, all the same. They chime the hours and play a little tune at each hour. Extraordinary how clearly one can hear them! Listen—there's that flat note. One bell is slightly cracked, and we have never had the money to put in a new one."

### Verse

'All like bells of sweet St. Mary's

On far English ground,'

quoted Tottenham. "Know where that comes from, Sterne?"

"You bet. Adam Lindsay Gordon. The finest poet Australia ever has produced."

The sound of the chimes faded in the distance as "Alicon" drove past at nearly the speed of a train, and the talk turned to other things. But Rodney was fated to remember with uncommon clearness the sound of those bells pealing across the cold sea, and Tottenham's apt quotation.

The rest of the day passed quietly enough, and that night they rendezvoused with the first squadron of light cruisers, and, a little later, picked up the first squadron of battle cruisers which loomed gigantic through the darkness.

Then they turned almost due east, and drove onwards through the night.

Next day was Sunday, January 24th. Rodney had had the middle watch—that is from midnight till four in the morning—and when he came on deck again after a couple of hours' sleep in his clothes, he thought he had seldom seen a more unpleasant morning.

"Rotten, isn't it, old son?" said Totts, appearing in his oilskins, and glancing round at the lowering sky and heaving leaden sea. "War's an over-rated amusement. Who'd sell a farm and go to sea?"

"I wouldn't mind so much if I thought there was anything doing," replied Rodney; "but we haven't had a word of news, and I'm fairly sure that, if those swabs ever did poke their heads out, they've bunked again behind their minefields."

"Looks like it," said Tottenham morosely.

The light increased slowly, but there was no sign of sun. It was a typical North Sea morning, dull and bitterly cold. Still, there was no fog, and the rest of the fleet were clearly visible, steaming in a widely extended line. Of the battle cruisers, the giant "Lion," Admiral Beatty's flag ship, was nearest to "Alicon." Beyond her they could see "Tiger," "Princess Royal," sister ships to "Lion," and farther away and somewhat astern, the smaller and slower, but still enormously powerful ships, "Australia" and "Indomitable."

It was past seven, and the two on the bridge were beginning to think longingly of breakfast when a distant but unmistakable boom smote upon their ears.

"A gun!" cried Tottenham, and hastily put his glasses to his eyes.

Almost before Rodney could follow his example and get his binoculars focused, two more heavy reports came dully across the waste of heaving waters, then the light cruiser, "Aurora," which headed their line, suddenly opened fire from her six-inch guns.

"A scrap, by thunder!" exclaimed Rodney. "That's a German of sorts, Totts. See, over there, just on the sky line!"

Tottenham did not answer. He was shouting rapid orders. In a moment the whole ship was alive. The skipper came running up on to the bridge.

"What is she?" he asked sharply of Rodney.

"German cruiser, sir. Three funnels, but that's all we can tell at present. She's under the lee of her own smoke. The 'Aurora' has engaged her."

There was no need for the latter part of the explanation. "Aurora's" guns were already hard at it. The thuds of her long six-inchers made the air quiver.

"At last!" muttered Chesney, and then he took charge. The engines quickened to their full power; the long, light vessel quivered under their drive, and she began to forge through the water at tremendous speed.

There was no need to "clear" for action. Ever since August, 1914, every ship of the British Navy had lived, stripped and ready for all emergencies. In a moment or two every man in "Alicon" was at his station, and waiting tensely for the order to fire.

Rodney was in charge of one of the two six-inch. Beside him stood his chief gunner, Abel Telford, a man with the chest of an ox and fists like legs of mutton.

He was staring eagerly at the German. They were near enough now to see her hull and the constant flashes from her guns.

"Ah!" the big man drew a long breath. "Got her that time, sir. Did you see that shell get home, sir?"

Rodney nodded, then lowered his glasses. "She's turned," he said. "She's running."

"Ay, falling back on her supports, sir. There's more of 'em out on the sky line. D'ye see, sir?"

"I do. Battle cruisers, by the look of them."

"The same as shelled Scarborough and Yarmouth, I'll be bound," said Telford. "Send as we get a smack at the baby-killers this day."

By this time the whole British fleet was steaming at top speed in pursuit of the enemy. But it was only too clear that the Germans had no notion whatever of seeking battle. One and all they were legging it for all they were worth, seeking the protection of their own harbours or mine-fields. In spite of the superior speed of the British vessels, it was plain that it must be some time before the Germans would be within range, and the skipper gave orders that breakfast was to be served at once.

Rodney could hardly tear himself away from the fascinating sight of the German smoke clouds on the horizon, but he knew that the day might be a long one and that it was important to stoke while time permitted. He fled down to the ward room, stowed away a large quantity of fried bacon, toast and marmalade, topped off with a big cup of coffee, and was on deck again inside ten minutes.

"Alicon" quivered like a reed as her powerful engines forced her through the water. A pillow of foam stood out on either side of her sharp prow, while aft rolled a huge wave that always curled, yet never broke.

"Gaining, sir," said Telford, as Rodney came up to his gun. "You can see their hulls now. Won't be so long before we're in range."

The light cruisers were now steaming along on the quarter of the battle cruisers. They could have passed them, for "Alicon" at least was quite two knots faster than the giants which towered on the port beam. But there was no object in doing so. Lightly armoured craft such as "Aurora" or "Alicon" would be at the mercy of the big German guns if they came to anything like close quarters.

Yard by yard and mile by mile, the British fleet diminished the distance between themselves and the flying Germans, but more than an hour passed before a spurt of flame burst from the fore turret of "Lion," and with a mighty roar a huge 13.5 shell hurtled out in the direction of the enemy.

"That's started it!" cried Rodney, with gleaming eyes. "The admiral has fired his first shot."

Telford grinned contentedly.

"Now we shan't be long, sir," he observed, but his voice was drowned by the thunderous roar of a full salvo from "Tiger." Four of her great guns had spoken simultaneously, and nearly three tons of steel went screaming through the sky.

WITH his glasses focused on the German ships, Rodney watched eagerly for the effect of the first salvo. Action had been opened at a distance of nearly nine miles, and prodigious as was the force which had driven forth the great shells from the muzzles of the monster guns, it took them fifteen seconds, a whole quarter of a minute, to cover this distance.

To Rodney and the other watchers the interval seemed endless, but at last—at long last—he saw two white splashes shoot up, seemingly right under the side of one of the far distant enemy ships. And almost at the same instant two other splashes rose just beyond her.

"Oh, fine!" he cried, carried quite out of himself by such splendid markmanship. "Straddled her, Telford!"

"Then they'll get her next time, sir," declared Telford confidently.

The splash, anxiously awaited by the fire control officers, gives them means of judging whether their shots fall short of or beyond the enemy. The order is passed at once down into the turrets, the sights are altered, the runs relaid, and once more a salvo flies forth, searching hungrily for the foe.

As Telford had predicted, the second salvo was not wasted. A flash of reddish flame gleamed against the distant hull, and a growl of triumph arose from the throats of the watchers aboard "Alicon."

"That's give 'em something to think about," said Telford, grinning delightedly. "What d'ye think she is, sir—that there German?"

"'Blucher,' by the look of her. Can't tell for certain at this distance, but she's last of the line, and I know she's not as fast as their newer cruisers."

"She's got it again, sir!" exclaimed another of the men. "Right amidships that one was."

The din now became terrific. "Princess Royal" and "New Zealand" had begun to talk. Nor were the Germans idle. Every moment a fountain of water would rise somewhere close to one of our big ships. But the Germans were still so far away that the reports of their guns were hardly audible, and it was difficult to believe that each of those spouts of foam was caused by an eleven-inch shell which, if it got home in the right place, would be sufficient to sink even one of those proud monsters that raced so furiously across the sea.

"Great Scott, look at that!" exclaimed Rodney suddenly, pointing to two trawlers which lay right between the opposing fleets. They were doing their best to get out of the way, but the breeze was now dead light, and they were only crawling along at about three knots an hour.

"Dutchmen, sir," said Telford. "Pore beggars, I'll lay the wits is pretty well scared out of them. Ah, see that!" as a German shell plunged into the sea within a hundred yards of the nearest, flinging up the water higher than the trawler's mainmast. "Glad I ain't in their shoes," he added, with a chuckle.

But the trawler's danger lasted a few moments only. The fleet, now travelling at about thirty-three land miles an hour, swept past them, and left them unscathed, rocking in the foaming wake.

"'Blucher's' getting it hot," observed Rodney presently. "Looks to me as if she was afire aft."

"So she is, sir," Telford declared. "And that there one ahead of her—'Lion's' hit her more'n once."

"That's either 'Moltke' or 'Seydlitz,'" Rodney told him. "Yes, she's getting it hot. The worst of it is that every minute brings them close to their own mine-fields."

"Why can't the beggars turn and fight?" growled the big gunner.

"'Cos they know what 'ud happen to them if they did," rejoined one of the other men. "Sneakin' out in a fog and shelling lodging-houses—that's about all they're fit for."

But in spite of this man's sneer, the Germans were antagonists by no means to be despised. They were shooting hard and fast, and more than one shell had got home upon the Dreadnought cruisers that led the line.

"Alicon" had not been touched, for she, with her consorts, had been ordered to keep well away to starboard of the battle cruisers. Their work was to come later.

By this time it was about half-past ten, and the running fight had been in progress for fully two hours. All the Germans, excepting the leading ship of their line, the big "Derfflinger" had been pounded pretty severely, and a fire had been observed aboard the "Seydlitz." As for "Blucher," she was now beginning to lag a little, and over and over again the huge seventeen hundred pound shells from "Lion" and "Tiger" hulled her with deadly effect.

Suddenly a simultaneous shout arose from every throat aboard the "Alicon." "Blucher" was seen to swerve sharply out of the line, and, evidently beyond control, steam straight towards the British fleet. Huge clouds of black smoke were rising from her funnels and her upper works were blazing like a bonfire.

"She's done! She's done!" cried Telford.

"Don't be too sure," said Rodney quietly. "See, they've got her under control again.

"All the same," he added, "I believe she's a beaten ship."

"Maybe we'll get our chance now, sir," said Telford earnestly. "Ah, 'Indomitable's' after her!"

He was right. "Indomitable," which, owing to her slower speed, had so far been unable to take any part in the battle, had turned to port, and was driving hard to catch up the crippled "Blucher." At the same moment the German destroyers and light cruisers which had, hitherto, kept well away to the port side of their larger consorts, turned to starboard, apparently with the intention of making an attack.

Signals fluttered from "Lion," and this time a ringing cheer came from "Alicon's" men. It was the order to engage.

"Our show at last," breathed Rodney, as "Alicon" changed course, and followed "Indomitable" at top speed.

"We're in luck, sir," said Telford. "There's only 'Aurora' and us and three destroyers on the job. Admiral's keeping of the rest behind."

"To guard him against submarines," replied Rodney. "We shall be running into 'em thick, before long. We're not fifty miles off Heligoland."

"Wish it was five hundred," growled Telford. "Might give us some sort o' show to mop up the blighters."

Rodney hardly heard what Telford was saying. His eyes were fixed upon what was happening in front. Several of the German torpedo craft had shot in between them and the wounded "Blucher," and were pouring out clouds of black smoke to act as a screen. The rest seemed to be dodging away again.

He turned and glanced back at the big British ships, and at the very moment he did so, saw a great column of water shoot up under the port bow of "Lion."

A sharp exclamation escaped him.

"Good Heavens, she's struck a mine!"

"By the living jingo, so she has, sir!" cried Telford, in a horrified tone.

For the moment "Blucher" was forgotten, and all eyes were turned upon "Lion." She was still steaming, but her speed had dropped to less than half what it had been, and she had an ugly list to port. Destroyers were rushing up to give assistance and for the moment it certainly seemed that she was done for.

"What rotten luck!" said Rodney bitterly.

It was in truth the worst of luck. Though the case was not as bad as "Alicon's" people had thought at first, that German shell which struck "Lion" on the water line altered the whole fortunes of the battle of the Dogger. "Tiger" and the other cruisers still kept up the chase of the enemy, but had "Lion" been able to continue, the chances are that neither "Seydlitz" nor "Moltke," sorely battered as they were already, would ever have seen port again.

"They re taking the admiral off, sir," said Telford. "He's boarding 'Attack.'"

"Good name, too," replied Rodney. "And see, 'Lion's' flying the signal, 'Engage enemy more closely.' Well, let's hope we get our smack at them before they get out of our reach."

It looked as though Rodney's hopes would be realised. The seeming attack by German destroyers had been but a feint. They were now drawing off again, and "Blucher" was visible again through the thinning smoke. Her bows were still turned towards the port she was never destined to see again; but now "Indomitable" was in range and pounding her heavily with her twelve-inch shells.

"Look at her, sir!" said Telford, in a half-awed tone. "She's a blooming fiery furnace."

It was true. The great cruiser was burning furiously fore and aft, and had a heavy list to port. And still "Indomitable" pelted her with her tremendous missiles. Hardly one missed. The red flashes burst against the German's armoured sides, the shells swept her upper works. One of her turrets had been blown bodily over the side, and of her eight big guns only two were firing.

Suddenly, through the drifting clouds of smoke, appeared an enemy cruiser coming almost due north, and at the same moment a shell screamed over "Alicon's" funnels.

"Crikey, here's one got the pluck to tackle us!" cried Telford.

"Don't talk! Let 'em have it!" barked Rodney, but Telford was already sighting his long gun, and, next moment, with an ear-splitting crack, "Alicon's" first contribution to the battle went screaming through the air.

Another shell and another followed. The British matelots, rejoicing that their turn had come at last, served the guns like furies.

"Ah, that's got her!" cried Rodney. "Good for you, Telford!"

Telford's second shot had struck the forward funnel of the German and scattered it into scrap iron. The fragments had swept the deck like shrapnel, and thrown one of her gun crews into confusion. Worse—so far as they were concerned—the smoke from the broken funnel poured like a black fog over the whole afterdeck, blinding and suffocating the gun layers.

"Ah, she's turning, she's running!" cried one of the men as the German swerved and, turning eight points, went off at full speed.

But she had a sting in her tail. As she turned, her two after-guns came into play, and Rodney felt the whole fabric of the long, slim "Alicon" quiver as a five-inch shell, passing through her thin plating aft, burst with a shattering explosion between decks.

"Alicon" swerved like a wounded duck and began steaming round in a wide circle.

"STEERING gear cut!" muttered Rodney. "Gad, if the German comes for us now, we're done."

"Not she, sir! She's got her bellyful," said Telford. Next moment the engines were slowed, and the cruiser moved quietly on the slow swells, while an engineer-lieutenant with half a dozen tiffies toiled frantically to repair the damage.

The work was done within an incredibly short time, and five minutes later the engines were again revolving at full speed, and "Alicon" was under complete control. But the delay, short as it had been, had cut her people out of their share in the last phase of the long drawn out action.

"Look at her! Look at 'Blucher'!" came a shout, and Rodney looked up in time to see a sight which he never afterwards forgot.

The great German cruiser had received her deathblow in the shape of a torpedo fired by one of our light cruisers. She had heeled right over, and was slowly sinking.

Blazing furiously from bow to stern, she was now a veritable furnace. Her decks were actually red hot, and clouds of steam arose as the mass of almost molten metal dropped slowly lower into the cold gray waves.

As for her wretched crew, such of them as had survived the terrific bombardment to which she had been subjected, they were literally between the devil and the deep sea. Their choice lay between being roasted or drowned. Swarming like flies on her rail, they could be seen flinging themselves off into the water, now by ones and twos, now by dozens at a time. The dull-coloured swells were covered with black dots which were the heads of struggling swimmers.

Even Telford was moved to pity.

"Pore devils!" Rodney heard him mutter.

"Our next job'll be picking of 'em up," remarked one of the gun crew. He was right. Almost as he spoke, "Alicon's" engines stopped again, and the boatswains' whistles trilled.

A bluejacket came running up to Rodney.

"You're wanted, sir," he told him.

There was no need to say more. Rodney ran forward to his cutter, and in a trice she was manned and over the side, and pulling like mad across the heaving swells towards the fast-sinking German cruiser.

Before she reached her the end came. "Blucher" rolled right over so that her starboard side was level with the water. A score or more survivors were seen actually standing upright on the steaming surface of a battered armour plate.

Then with a final convulsive heave, like some great wounded sea monster in its last agony, her bow rose slightly, and she slid backwards under the water. A cloud of smoke arose, and for a moment or two the sea boiled furiously, while out of the vortex were flung up all kinds of miscellaneous rubbish, broken boats, odds and ends of half-burnt timber, cinders, oil, and among them not a few poor human remains which, only a couple of hours previously, had been living, breathing men.

Rodney, holding the tiller lines and facing her, saw the whole horrible business. Not that he had much time to think of its horror, for almost at once they were among the poor perishing wretches, and dragging them in one after another.

Some had ghastly wounds, some were horribly burnt and scorched. All, by their lined faces and sunken eyes, bore signs of having been through such an awful ordeal as few men have ever been called upon to endure.

The British matelots, all their anger forgotten at sight of such suffering, did what they could for the poor wretches.

"There's a chap over there a-holding on to a table, sir," said the coxswain, a smart young fellow called Hearne. He pointed as he spoke to a head that bobbed above a wave at some distance.

"Give way, men! Give way!" Rodney ordered and the boat sped away towards the man. She was within a few lengths of him when Rodney saw him let go and disappear.

"Pull!" he shouted; "Pull!"

A hand, the fingers clutching wildly at empty air, was just vanishing beneath the water as the boat shot up to the spot, Rodney made a grab, but missed it by a matter of inches. He was so near that he could actually see the hand glimmering faintly just below the dull surface.

The idea of a still living man going slowly down to his end in that freezing sea was too much for Rodney. Like a flash he sprang to his feet.

"Stand by!" he said, and before any one could stop him had dived overboard.

Rodney had learned to swim at an age when most boys can barely walk. His father had seen to that. He was almost as much at home in the water as on land, and in spite of the bitter chill, went straight down, head foremost, into the depths. His groping lingers met the man's arm, closed on it, and turning like an otter, he struck upwards.

At the same instant the German, in the blind agony of drowning, clutched him round the neck with the other arm.

Rodney struggled desperately to clear himself from the throttling grip, but he might as well have tried to tear himself loose from the tentacle of an octopus. He kicked out frantically in an effort to rise. It was no use. Instead, the man's weight was dragging him down.

The pressure on his lungs was deadly. He felt that in another moment he would open his mouth. And then, just at the last moment, something struck him sharply between the shoulders.

With a last desperate effort, he managed to turn and grasp it. It was an oar blade, and instantly he and his almost unconscious charge were dragged back to the surface and hauled by strong arms aboard the boat.

"Close call, sir!" said Hearne sympathetically, as he rolled Rodney in a spare oilskin. "Them Huns is never safe to meddle with."

"Very smart of you to reach the oar down, Hearne," gasped Rodney.

"I guessed what had happened, sir. And it was a lucky shot I made, for I couldn't see neither of you."

"Mighty lucky," agreed Rodney. "Are there any more to pick up?"

"Can't see no more, sir. And there's a fog a-coming on. I reckon we'd best get back to the ship."

"Right! Carry on, men."

The boat was at least a mile from "Alicon," and "Alicon" herself was fast disappearing from view in the thin mist which was beginning to drift, like pall smoke, across the sea. The men, who were hungry and tired, set to pulling with a will, when all of a sudden the sharp crack of a twelve-pounder smacked out with startling violence.

Before they could tell where the sound came from, there followed a startling roar, and not fifty yards from the boat the sea boiled and rose in a towering fountain of foam.

"Great Scott, they're at it again!" exclaimed Rodney, and, flinging off the oilskin, sprang up. "The German cruisers must have turned."

"No, sir," replied Hearne quickly, "that's an airship, not a sea-ship."

As he spoke he pointed upwards, and Rodney found himself staring up at the vast yellow belly of a gigantic Zeppelin, which, having sunk down through the cloud veil above, had just dropped a huge bomb.

"Well, if that ain't the limit!" growled one of the oilier blue-jackets in the boat—"bombing of the boats as is picking up their chaps!"

Next instant down came another bomb, even closer than the first. It seemed to sink ten feet before it exploded, and the charge must have been an enormous one, for the sea opened like a crater, and the wave that was flung up nearly swamped the boat.

"Port, men! Port! Pull hard! She's coming right over us," cried Rodney.

The men pulled with savage energy, and lucky for them that they did, for the third bomb dropped almost on the very spot they had just left.

"Gosh, that's a squeak!" muttered Hearne.

"Keep her going, men!" cried Rodney. "Keep her going. If we can get into that fog bank over there, we're safe."

The huge air-ship had changed course, and seemed to be pursuing them. Her vast bulk appeared to shut out half the sky. The roar of her powerful motor engines was like the clatter of a dozen aeroplanes at once. Not a soul in the boat but fully believed that his last minute had come.

The British bluejackets stuck to their task, and pulled for the fog bank with dogged, desperate energy, but the German prisoners, of whom they had eight in all, were terrified out of their lives. Some screamed aloud, some prayed for mercy.

"Getting a taste of your own culture!" growled Hearne, as his oar blade hit into the flank of a wave. "Funny ye don't seem to like your own medicine!"

Still another bomb came whizzing down from above, to set the North Sea boiling again. But this was by no means so good a shot as the last, and before the next could arrive the boat had driven into the comfortable shelter of the fog patch, and the Zepp was lost to view.

Rodney called a halt, and the panting men rested on their oars.

"Wonder 'ow much them bombs costs, Bill," inquired one bluejacket of his neighbour.

"Don't know, Jock, but they ain't made for nothing."

"Shameful waste, I call it," said Jock. "Think o' all that there stuff being wasted on the blooming waves. I wish I 'ad the money in my trouser pockets."

The whirr and clatter of the Zeppelin engines grew fainter. Somewhere out of the fog the twelve-pounder rang again with its vicious bark.

"One of our destroyers a-trying to fetch 'er down," remarked Jock, "but it ain't no good. They can't get the elevation."

Rodney looked round anxiously. There was now no longer the least sign of "Alicon," nor, for that matter, of any other ship. And, with his boat-load of prisoners, several of whom were wounded, he was naturally anxious to get aboard as soon as possible.

"I reckon she lies to the sou-west of us," said Hearne.

Rodney nodded. "That's the direction we'd better keep. Give way, men."

"Put the oily on again, sir. It's mortal cold," said Hearne.

Rodney did so. He was chilled to the very bone, for water and air alike were very little above freezing point.

They pulled on, but the fog had grown thicker, and its clammy wreaths enveloped them. They were like men groping in the dark. For the next ten minutes they plugged along steadily, but still no sign of the ship.

All of a sudden the beat of engines came to their ears.

"There she is," said Hearne, "coming to look for us."

The sound increased, then without the slightest warning a lean black bow came charging out of the fog straight upon them.

"Port!" yelled Rodney; "port, all!"

It was too late. True, they escaped the full rush of that charging mass of steel, but the wash caught them. The boat was swamped in an instant, and every mother's son aboard her left struggling in the chill waves.

"HE'S coming round. Get that cocoa ready. The poor beggar's as cold as stone."

The words came faintly, as if from a great distance, to Rodney's ears. His brain was still so muzzy and confused that he could not in the least remember what had happened, and had not the faintest notion where he was.

He tried to open his eyes, but they felt as though leaden weights lay upon the lids. At last, however, he succeeded in doing so, and found himself lying in a narrow bunk in a very tiny cabin. The fabric beneath him throbbed and quivered under the drive of enormously powerful machinery, and he could hear the hiss of parted water just outside the thin steel plating under the small port hole which lighted the cabin.

Next he realised that a slim-built, smooth-shaven young man was standing beside his bunk. By the red velvet band between the gold lace stripes on his cuff he realised that he was a doctor.

"Hallo!" said the latter cheerfully, "you've been a nice time coming round. 'Pon my Sam, for a bit I thought you were a goner!"

"Not me!" replied Rodney, and even to himself his voice sounded strangely weak and hoarse. "But I say, where am I? What's happened? And—and"—as recollection began to come back to his clouded brain—"what about my men?"

"Keep the catechism a minute, old chap," replied the doctor. "Here, Purley, give us that mug."

An orderly stepped in from the flat outside, and handed the doctor a big enamelled metal mug of some steaming stuff.

"Just get this down," said the latter to Rodney, "Then I'll do my best to satisfy your curiosity."

It was cocoa blazing hot, and laced with a tot of navy rum. To Rodney it was food and drink both, and he swallowed it to the last drop.

"Topping!" he said, as he handed the mug back. "Jove, I wanted something like that."

"I should rather think you did," replied the doctor. "'Gad, you're looking better already! Now then, I'll try to set your mind at rest. My name's Lancing, and this is the destroyer 'Deva.' Your chaps are all right. We picked 'em all up, and two of your prisoners. The others. I'm sorry to say, never showed up at all."

Rodney drew a long breath.

"Thanks be, my chaps are all right. Any chance of getting back to our ship?"

Lancing shook his head.

"Not for the present, I'm afraid. The chances are we're fifty miles from her by now. We're on a special job."

Rodney's eyes opened widely.

"East or west?"

"East. Fact is, David signalled us to follow up as near as we can, and try to find out whether the other three big Germans get home; also there's a lame duck we're chivying."

"Phew! What a game! Where are you now?"

Lancing shrugged his shoulders.

"Ask the owner. I don't know. All I can tell you is we're ripping along through the thickest kind of a North Sea fog, and we can't be a terrible long way off Heligoland."

"But we must be right in among the mine-fields, man!"

Lancing unbuttoned his jacket, and pointed to his life-saving waistcoat. "That's what I thought, so I took the precaution of putting on my floater," he replied quite cheerfully. "Still, I'm not worrying a lot. Our skipper knows his job as well as the next man."

"Let me see, who's got 'Deva'—Ballard, isn't it?"

Lancing nodded. "And a top hole chap, too," he declared.

"Must be, or he wouldn't have been given a job like this," replied Rodney. "I say, can I have another go of that cocoa?"

"Rather! Like some grub, too?"

"I should. I haven't had a feed since breakfast."

"You poor beggar! I'll send you something in. Now, I must go and have a squint at my other patients. And I say, if I were you, Sterne, I'd take a calk+ while I had the chance. It's likely to be a busy night."

(*calk=nap.)

He hurried off, leaving Rodney feeling a hundred per cent, better. Lancing's very presence was a tonic. He was none of your staid, elderly ship's doctors—nothing but a cheery, young medical student, one of scores who had hastened to put his services at the disposal of their country, and young enough to enjoy every minute of his difficult and often dangerous duties.

Presently Purley came in with a tray on which was a scratch but satisfying meal of sardines, bread and butter, marmalade and cocoa. Rodney ate enormously, then with a satisfied sigh dropped back on the pillow, and without another thought to the dangers that surrounded him, was almost instantly asleep.

How long he slept he had no idea, but suddenly he found himself sitting bolt upright, with the sound of a heavy report in his ears. Like a flash he was on his foot. It was nearly dark, but there was light enough to see his uniform, thoroughly dried, lying close at hand. Flinging off his borrowed pyjamas, he fairly hurled himself into his own things, and raced for the deck. As his feet clattered up the narrow iron ladder came a sudden burst of heavy firing, and as he thrust his head above the hatch a heavy shell screamed close above the deck, while a second shore away the top of the foremost funnel.

Less than a mile away, a shadowy bulk against the dim evening sky, was a good-sized cruiser. She seemed to be steaming at full speed, but it was clear that she was badly crippled, for "Deva" was catching her up hand over fist. Flashes of fire darted from her dark sides, but the light was bad, and the shooting worse. Besides, the destroyer was running on a zig-zag course which made her all the more difficult a target.

Rodney dashed to the bridge.

"Anything I can do, sir?" he asked of Ballard.

The skipper, a square-built man of about thirty, with a strong jaw and heavy eyebrows, gave him a quick glance.

"Oh, you're Lieutenant Sterne. Not for the moment, thanks. Come on up here, if you like."

Rodney was delighted. He hurried up on to the narrow bridge, which shook like a reed under the tremendous drive of the great nest of engines housed under the throbbing steel deck. "Deva" was doing all of thirty knots, and the wind of her rush nearly took the cap from Rodney's head. Every funnel showed a crimson cap of flame, and a storm of fine cinders beat down from them like fiery rain.

"A cripple," said Ballard briefly. "She's 'Stargard,' I believe. Our job is to finish her—that is," he added with a quiet smile, "if she doesn't finish us first."

The latter event seemed by no means improbable, for the German, if crippled, had plenty of guns left in commission. They were the five point ones, which all the German light cruisers carry, and one shell in the right place would be quite sufficient to finish the destroyer. Her steel sides were little thicker than a biscuit tin, and offered no resistance to anything much heavier than a rifle bullet.

Almost as Ballard spoke, a shell tore past them so close that the wind of it made Rodney stagger. It shore away part of the canvas dodger, and cut the steel rails of the bridge like a giant knife.

"Close call," smiled Ballard. He was the coolest man Rodney had ever met.

Another shell, a moment later, carried away the whole of their aerial, including the mast, and then a third just grazed the deck aft, cleaving a deep groove, but luckily failing to explode. But "Deva" herself seemed to bear a charmed life. The water all around her was churned into white foam by the hail of flying projectiles, yet not one got her in any vital spot. Meantime, with every minute that passed, she was lessening the distance between herself and "Stargard."

Rodney noticed the little groups that stood by the two deck torpedo tubes. He saw that Ballard, cool as he was, was eagerly reckoning the distance at which he would let go.

The moment came.

"Shut down!" he shouted to his torpedo gunners. Then he telegraphed an order to the engine-room, and at once the destroyer slightly slackened speed.

"Let go!" came the order.

From the bow tube of "Deva" a long, gleaming cigar-shaped object leaped, and vanished among the gray waves. Ballard did not wait to see whether the tin fish reached its mark. Sharp and curt came his orders to the men at the deck tubes, and one after another the torpedoes, driven by their heavy charges of compressed air, flashed out over the side, and sped away on their mission.

The third and last was hardly in the sea before the sky was split by a stunning explosion. A geyser of white water leaped against the cruiser's quarter. She quivered like a wounded beast, and almost instantly began to heel over.

"Done the trick!" remarked Ballard, as cool as ever. "That was the bow one. Not bad, eh, Sterne?"

Before Rodney could answer there was a rending crash almost under their feet, and "Deva," struck full amidships by the very last shell fired by the sinking cruiser, reeled and swerved. From below came a horrible grinding sound, then a cloud of white steam eddied up through the ventilators.

"Done for us, too, seemingly," continued Ballard, in his even voice. "Go below, Sterne, will you, and report damages. It's going to be a bit awkward if we can't steam, for there's no one to depend on but ourselves. To the best of my belief, we aren't ten miles off the Schleswig coast."

The steam was like a fog as Rodney clawed his way down into the depths. Some one was groaning down in the smother, and as he dropped into the alley-way below, he saw Lancing busily at work giving first aid to a badly-scalded stoker.

"What's the damage, Lancing?" asked Rodney quickly.

"What isn't?" replied Lancing coolly. "By the look of things, that last shell chewed everything up. It's killed three poor chaps, too, and there's two more besides this one badly scalded. But ask Renwick. He'll be able to tell you more about it."

Renwick, the engineer-lieutenant, Rodney found in the engine-room, working like a Trojan to stop the escape of steam. He was black as a nigger, and streaming with perspiration.

"Commander Ballard sent me to inquire the damage, Mr. Renwick," said Rodney.

Renwick, wrench in hand, looked up.

"Hardly sized it up myself yet, but it's pretty bad. Still, I believe we can get steam on her again in an hour or so. Not more than ten knots though, if that. That infernal shell has knocked half my engines into scrap iron."

Rodney thanked him, and hurrying on deck again, made his report. Ballard looked thoughtful, but only for a few moments. Then his face cleared.

"Ten knots. That'll be all right. We've got the night before us, and with luck we'll manage to sneak back to some sort of safety before daylight."

At this moment a big quartermaster came hurrying on to the bridge. His brown face was very grave.

"That shell has started a plate, sir," he said. "She's leaking badly."

"How much?" snapped Ballard.

"There's three foot of water in her already, and the pumps are useless. She won't float three hours."

ONCE more under her own steam, "Deva" wallowed through the dark water. But it was clear to all aboard that her fate was sealed, and that never again would she see her home port. Although the pumps were working once more, they could not cope with the steady inrush of salt water, and already the sea was invading the floor of the engine-room.

Ballard had set her course due north.

"I'm trying for Danish waters," he told his officers and Rodney. "It won't be much fun, being interned, but anything's better than a German prison, and that's all we've got to hope for if we land upon the Schleswig coast.

"Anyhow," he added, with an attempt at cheerfulness, "we've got one little job to our credit. 'Stargard' is off the German navy list."

Silence fell on the little group on the bridge. They were all too anxious to talk. And still the poor lame duck, with her engines clattering and groaning, struggled on her course.

Rodney was the first to speak.

"I believe I hear breakers," he said.

"Not unlikely," Ballard replied. "I can't tell exactly where we are, but probably off the island of Sylt."

"That means we've got a longish way to go yet," observed Walters, Ballard's second in command.

There was a rattle of feet on the bridge ladder, and through the gloom appeared Renwick's muscular figure.

"I have to report, sir, that there are six inches of water over the engine-room floor, and that, at the rate it is rising, the fires will be extinguished within another quarter of an hour."

Ballard muttered something under his breath. He paused a moment as if thinking deeply, then spoke sharply.

"I leave it to you, gentlemen. Shall we carry on till she sinks, or shall we drive her ashore and take our chances."

"I'm for the beach, sir," Walters answered unhesitatingly.

"And a German prison?" said Ballard.

"Not necessarily, sir. We might end better than that."

"Fighting, you mean?" said Rodney.

"Invading Germany. Just so," replied Walters, with a grin.

"I'm on," said Renwick grimly. "Well take a few Huns to Hades with us before we snuff out."

Ballard gave a satisfied chuckle.

"I quite agree with you, gentlemen." He turned to the quartermaster at the wheel.

"Port your helm," he ordered.

"Deva" swung slowly round at right angles to her former course, and ploughed heavily in the direction of the land. Ballard gave orders for all hands to be mustered on deck, and in a very few moments all, with the exception of the stokehold crew, who were still toiling below, were lined up.

Ballard addressed them.

"Men, our ship is sinking under us, and we have no chance of making a Danish port. Nor, as you probably know, is there the least chance of our being picked up by any of our own people. So our choice is between the Devil and the Deep Sea. Personally, I prefer the Devil, in other words the enemy, but any that prefer cold water are welcome to stay aboard."

There was a burst of laughter.

"The Devil for us, sir," came the response from threescore throats at once.

"I thought you'd say so," said Ballard. "So I have already headed straight for the German coast. To the best of my belief, we shall land upon Sylt, which is an island off the coast of Schleswig. Now then, all of you get your arms and rations. Full marching kit. Don't waste time. There's no saying how long the ship will last."

"She won't last long, and that's a fact," growled Renwick, and it was clear to all that he spoke no more than the truth. The sluggish way in which she moved was plain proof that she was very near her end.

The boats—they were only collapsibles—and the life-rafts were all ready, and the men drawn up on deck, each with his rifle and a hundred rounds of ammunition. A hefty-looking lot they were, even in that dim light, and well able to account for twice their number of Huns.

"You were right about those breakers, Sterne," said Ballard presently. "I hear them plainly now."

"I believe I can see them, sir," said Walters, peering out into the gloom to the eastward. "Yes, there's a line of white over there on the port bow."

As he spoke, came a sudden hiss of steam which gushed up through the main hatch and the engine-room gratings, and next moment the stokehold crew came tumbling up on deck.

"That's the finish," muttered Ballard. "The water's reached the furnaces."

The engines stopped, the screws ceased revolving, but the way she still held carried "Deva" forward.

"Tide's setting in, too," said Walters. "There's still a chance we may beach her."

"I'll give her another five minutes before I get the boats over," said Ballard quietly, and taking out his watch glanced at it by the shaded light of the binnacle lamp.

Slowly, very slowly, the broken craft surged forward. The breakers were now plainly visible as a line of white through the gloom. Their sullen roar sounded clearer every moment. Three minutes passed, four—then with a low, grating sound "Deva" took the ground, and driving her nose deep into sand, remained hard and fast.

"So far so good," said Ballard quietly. "Now the only question is shall we wait for dawn before landing? What do you think Walters?"

"No, sir. Much better get ashore at once," answered Walters earnestly. "Then we get a chance of a surprise attack."

"But I doubt if there's anything to attack except sand hills, and if there is, how are we to find it?" replied the commander. "Let's hear your opinion, Sterne."

"I'm inclined to split the difference, sir," said Rodney. "I believe, like Mr. Walters, that we ought to be ashore before light, but the night is young yet, and we are safe enough where we are. I should suggest that the men have a watch below and a good feed, and that we land about two hours before dawn."

"I thoroughly agree with you," replied Ballard decidedly. "We can't do better. Mr. Walters, be good enough to give orders to that effect."

Walters agreed cheerfully, and the men turned in, all standing. Barring the few necessary for the watch, everybody aboard the stranded craft got a sleep. At three they were roused out, and as there was no object in saving any of the stores aboard "Deva," the breakfast that was served was lavish.

Just before four began the process of landing the crew. The spot where they had gone aground was evidently a very desolate one, for there was not a light visible anywhere along the coast. All the same, orders were given that no more noise than was necessary was to be made. The men were specially warned against talking or laughing.

Ballard called Rodney.

"Mr. Sterne, I shall be obliged if you will go ashore with the first party. It will mean three, if not four journeys to get the whole crew ashore. I shall send Mr. Walters with the second lot. Myself, I have certain arrangements to make before I come ashore."

He did not specify what these were. There was no need to, for Rodney knew perfectly well without being told.

"Take your men with you," Ballard added. "And keep all well together, and close to the beach. If you are attacked, you must, of course, defend yourselves, but I hope it will not be necessary to fire any shots until the whole ship's complement are ashore."

"Very good, sir," Rodney answered, and proceeded to carry out his orders with all speed.

It was ticklish work getting through the breakers in the small collapsible boats, but luckily the breeze was dead light, and the sea very nearly calm. And the distance between the ship and the beach was only about five hundred yards. Twenty minutes after receiving his orders, Rodney had his own men from the "Alicon" and about fifteen of "Deva's" safe on the beach, and had sent the boats back to the destroyer.

"Regular blooming desert, this, sir," remarked Hearne, as he glanced at the desolate surroundings. The night was clear, and the cold winter starlight gleamed faintly on a barren landscape. As far as they could see, there was nothing but sand and marram grass. Inland, there rose against the dark sky a line of tall, rounded dunes.

"You're right, Hearne," replied Rodney, who, in happier times, had yachted along this coast. "It's all bare sand hills for miles. But there's a fair-sized town on the island—Westerland they call it. I don't know whether we are north or south of it."

"And how far may we be from Denmark, sir?" asked one of the men.

"Not more than thirty miles. The nearest point is Manö Island."

"How far are we from Germany? That's more to the point, sir," said Hearne, with a smile.

"From the mainland, you mean. Oh, seven or eight miles. There's a widish channel between Sylt and Friesland."

"And is there any troops on this here island, sir?" inquired the other man.

Rodney shrugged his shoulders. "I haven't a notion. But they are sure to have some. I believe they are always in a stew about our invading them."

"I reckon we've obliged 'em at last," said one man. "Let's 'ope they'll be grateful. But there—there ain't no thankfulness in a 'Un."

The others chuckled, and Rodney had to check them and order silence.

Within a few minutes more the second contingent came ashore, and just as the stars were beginning to dim before the light of a new day, Ballard, with the last of his men, reached the beach. His face, in the pale dawn, was set and grim. Rodney understood his feelings. It is bitter for any man to lose his ship.

"All well?" he asked of Rodney.

"All well, sir. No sign of the enemy."

"Very good. Then the sooner we move on, the better, for something will shortly occur which is calculated to rouse the attention of any Germans who may be in the neighbourhood."

Rodney asked no questions. As before, he perfectly understood. Low-voiced orders were issued, and turning due north, the eighty-odd British bluejackets marched rapidly up the beach.

They had gone no more than a mile when the stillness of the dawn was broken by a tremendous explosion, and with one accord the whole column halted and looked round. They were in time to see "Deva" rise skyward in a cloud of fragments which strewed the gray waters far and wide. A great umbrella-shaped plume of smoke rose to a vast height, and moved slowly away to the westward.

"Pore old barky!" Rodney heard a man near him mutter. But no one else spoke. They knew that they had literally burned their boats behind them, and that from now on their fate depended entirely upon their own rifles and cutlasses.

Without waiting for orders, they tramped on again. Rodney found himself next to Ballard.

"Couldn't chance her falling into enemy hands, Sterne," said the latter briefly. Then after a moment's pause.

"Do you by any chance know the coast?"

"I've yachted here, sir—about three years ago."

"Then, tell me, isn't there a village somewhere on the north end of the island?"

"Yes, a little place called Elbogen."

"I thought so. My notion is to try to rush it. There ought to be craft of some sort in the harbour. If we could seize boats enough to carry us there would be just a chance of making Manö Island."

"Very good idea, sir. The only trouble is that they wouldn't be anything but sailing craft, and there's mighty little breeze at present."

Ballard shrugged his broad shoulders. "We'll have to take our chances of that. The wind may come up after sunrise."

"Still," he added, "this is only a suggestion. We may never reach Elbogen at all. That explosion must have waked the whole island, and whatever forces they have here are probably on their way already to see what's up."

Before Rodney could reply, the sharp crack of a rifle came from the waste of sand dunes to the right, and a bullet very badly aimed sang viciously overhead, and plopped into the sea quite fifty yards from shore.

"They've arrived a little earlier than I expected," remarked Ballard calmly. Then raising his voice, "This way, men."

He led them inland towards the dunes and they followed at a run.

The unseen rifle spoke again and one of the leading men flung up his hands, and dropped flat on his face.

A COMRADE stooped over the fallen man.

"Done for, pore beggar! Right through the head," he said.

"Leave him, then. We may be able to bury him later," said Ballard quickly. "Forward, all of you. At the double! We must get shelter till we can see where this firing comes from."

Bullets were singing spitefully overhead as the line of bluejackets followed their skipper. He headed for a gully between two of the rounded dunes which fringed the beach. Thicker and thicker came the shots, but the firing was wild, and they reached the shelter of the gully without losing another man.

Ballard did not pause.

"This is a death-trap," he said quickly to Rodney, who was close beside him. "We must find higher ground."

The gully rose sharply. In a few minutes they reached a sort of saddle, with the rounded tops of sand hills on either side. Ballard turned sharply to the left, and scrambled up through the soft, sliding sand.

"Dig yourselves in here, men. Scratch any sort of shelter. So long as they haven't got field-guns we'll be safe enough here for the moment."

The bluejackets flung themselves down under shelter of the crown of the steep dune, and began scratching away, like terriers digging out rabbits. The sand was so soft that it was only a few moments before they had sunk into it. The hill lent itself to defence, for on their side it was crescent-shaped, the curves of the crescent protecting their flanks.

"Now, we've got to find out where those Hun riflemen are posted," said Ballard.

"Let me, sir," said Rodney eagerly. "I've done a bit of stalking wild fowl in my time. I ought to be able to stalk a Hun."

Almost before he got the required permission, he had started. He did not go straight up the hill, for he reckoned that it was the summit the enemy would be watching, but worked over to the right. Fortune favoured him, for here the ground was covered with a thin tangle of sea holly and other salt growth, and going flat on his stomach, and creeping snake-fashion he was able to gain the steep ridge of the crescent without being seen.

Below, to the north, stretched a long slope leading down into another gully much wider than the one they had come up. The first thing he noticed was a queer-looking building made apparently of tarred wood, which stood on top of the opposite dune. It seemed too solid and large for a fisherman's shelter, and it was certainly not a lighthouse.

But he had no time to speculate upon its uses, for a second glance showed him a number of men gathered in a small hollow in the side of the big dune below the building. There were, at a rough estimate, nearly a hundred, and their number was constantly growing as fresh men came hurrying down a road which came down the dune from the black-looking building above.

These men were not in the greenish khaki of the regular German army, but wore the gray uniform of the Landwehr or Reserve.

He lay staring at them for a moment or two.

"It's a big force for them to have in a place like this," he muttered in a puzzled tone. "And, by Jove, at the rate they are coming, they'll soon outnumber us two to one."

Fresh men came pouring down from above. He counted thirty-two. Then they ceased, and no more came. An officer was giving orders. Rodney could hear his voice, but the distance was too great to distinguish words. Then he turned, and, making his way back quickly to his own people, reported to Ballard.

"A hundred and fifty, you say!" said Ballard. "That's a lot for a forsaken place like this. But if they're only Landwehr, we ought to be equal to them. Wish I knew what they were going to do."

"I vote we rush them, sir," said Walters eagerly.

"I should have thought you'd read enough about frontal attacks during the land war," replied Ballard dryly. "We should lose half our men charging up that sandy slope. No, I'm inclined to sit tight and wait for them."

"If you'll allow me, sir," said Rodney, "I'll go back up to my spy-hole and watch them. I can give you a signal if they move. With their strength, I should reckon it's they who'll do the attacking."

Ballard nodded. "I shouldn't wonder if you're right. Yes, go ahead. You can semaphore if you see them move."

Rodney slipped hastily back, and crept into his lair among the thin, dry sand growth. He was just in time to see the last of the Germans leaving the hollow. The whole force was coming down the gully towards the beach. Clearly, they meant to work round and outflank the British force.

On the face of it, this seemed a crazy manoeuvre, for it would appear that they rendered themselves liable to a flank attack, or to a hail of bullets from the top of the hill. But this was not really the case, for now Rodney saw that they were using the same road which ran down from the building on top of the dune.

This road ran along the bottom of the gully, but being deeply sunk was as good as a communication trench. Not even the Germans' heads were visible, as they filed along it. As Rodney watched, the last of them dipped into it, and disappeared from sight.

"So they're trying to steal a march on us!" he muttered. "Jove, but it's lucky I spotted them in time!"

Turning quickly, he dropped down behind the crest of the sandy ridge, and hastily semaphored his news to Ballard.

Ballard wasted no time. Low-voiced orders were passed from man to man, and the whole of "Deva's" men went off rapidly towards the left flank of the hill.

"Got 'em, by jingo!" breathed Rodney, and set to running hard to catch up.

On the soft sand, the men moved almost soundlessly, and as they reached the ridge of the dune Rodney saw the leaders drop down and wait for the rest. Within a very few moments the whole force was arranged in a long line just under the crest of the hill.

Rodney ran for all he was worth. He was desperately anxious not to miss the show. But the sand was so soft and deep that at every step he sank over the ankles, and before he could reach his companions Ballard had given the order, and, like one man, the bluejackets sprang over the crest and vanished down the far side.

Rodney reached the top in time to see them racing down the steep slope beyond. Not in a bunch. They were strung out in a wide line, for Ballard, when he gave his orders, had known well enough that they could not hope to take the Germans entirely by surprise. Their scouts on the opposite hill would see to that.

In this he was right. Just as Rodney went leaping down after them a rattle of rifle-fire broke out all along the sunk road below, and bullets came screaming up past him as he ran.

Two of the British force went down—two only! It seemed amazing that the casualties should be so slight, but in a moment Rodney saw the reason. The sunk road was so deep that, while it afforded perfect protection to the men in it from bullets fired from above, it also prevented them from getting the range of the attacking party. Only the tallest men could hope to lift their rifles over the edge of the high perpendicular bank.

The bluejackets threw off all concealment. A roar of defiance arose from eighty throats, and in a human avalanche they poured down into the sunk road on top of the Germans.

There was little shooting. The work was nearly all cold steel, and the keen cutlasses wielded by brawny arms did fearful execution.

When, a moment or two later, Rodney arrived on the scene, the whole deep, narrow road was packed with struggling men, fighting furiously. In that narrow space the Germans had not room to wield their bayonets, and so were at a terrible disadvantage. Besides, they were not first-line troops, but mostly men of forty, fat and not as active as they had been. Fully one-third were already down, and the remainder were no match for their stalwart assailants. Panic was seizing them, and the only ones who kept their heads were their officers who, with hoarse shouts, did their best to rally their failing forces.

"Give it 'em, lads. Let 'em have it!" It was Walters, "Deva's" young lieutenant, and he was just below Rodney. As he shouted, he cut down a man who was driving at him with a bayonet. Next instant a big, square-headed German sergeant made a desperate lunge at him. Walters tried to spring aside, but tripped over the body of the man he had just cut down, and fell. Another moment, and the sergeant would have driven his bayonet into him when Rodney leaped from the bank and, landing square on the German's back, brought him down sprawling.

Even then the fellow struggled desperately, but Rodney quieted him with a rap over the head from his pistol butt, and the German sergeant dropped and lay still enough.

"Thanks," said Walters rapidly. "Do as much for you next time. I say, we've got 'em going."

He did not wait to say more, but dashed off, making for a stout German who was clambering out over the far side of the road, and, catching him by the legs hauled him down.

Next moment Rodney himself was in the thick of it, laying about him with the butt-end of a German rifle which he had snatched up. He floored two men, then a third, an ugly-looking beggar with a broken nose and close-shaven head, came driving at him with a bayonet. Rodney sprang lightly aside, pulled his revolver, and shot the fellow through the head.

"After them, men! Don't let any escape, if you can help it," rang out Ballard's voice above the din. "We don't want them to bring help."

The Germans were breaking. The rush of "Deva's" men had cut their column in two. Half of them were down. Those in front and behind were bolting like rabbits. Rodney saw three in succession scramble over the far bank and go running right up the dune, in the direction of the black house on top. He yelled at them to stop, but they paid no attention, so he fired at the nearest, and brought him down. The other two only scuttled the faster.

Mindful of Ballard's orders, Rodney made a jump, reached the top of the bank, and went after them for all he was worth. He gained, but they had a long start, and the sand was too soft, and the slope too steep for fast going. He pulled up and fired two more shots from his pistol. But he was badly blown, and both missed. Then the hammer snapped, and he realised that the magazine was empty.

There was no time to reload. He must trust to running them down, and off he went again up the dune. The two Germans reached the top thirty yards ahead of him, and he fully expected to see them bolt into the building. But they did not. Turning to the right, they reached the road again and running hard, vanished.

Rodney, too, gained the road. He saw that it curved to the right and led inland. He was already a long way from his friends but in the excitement of the chase he never gave that a thought. His one idea was to stop these beggars from getting away and fetching reinforcements.

Down the slope he went as hard as he could leg it. He was gaining fast and soon was within half a dozen yards of the hindermost of the two Germans. The fellow was flagging. Rodney could hear his breath wheezing and gasping in his throat.

Suddenly the man stumbled, and went flat on his face. Rodney could not stop himself. He tripped over the fallen German, and came down heavily on hands and knees.

At the sound of his fail, number one, a younger, stronger man than the one who had fallen, stopped short and spun round. Rodney, with all the breath knocked out of his body, made a desperate struggle to regain his feet, but before he could do so the other was on him, and swung at his head with the butt of his rifle.

Rodney felt a stunning shock; stars danced before his eyes; then everything disappeared in a whirling darkness.

AN aching head and a throat like dry leather—those were Rodney's first sensations as he struggled slowly back to consciousness. For a time his head felt too heavy to move, and his eyes so painful he dared not open them, and he lay in that sort of stupor which sometimes come after an ugly dream.