RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"Tons of Gold,"

Hutchinson & Co., London, 1935

Title Page, "Tons of Gold"

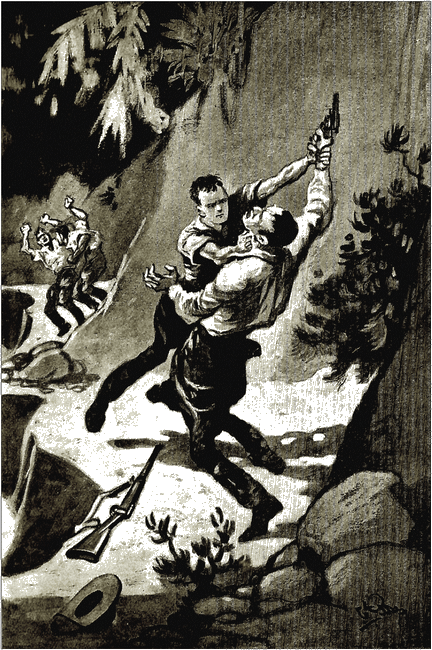

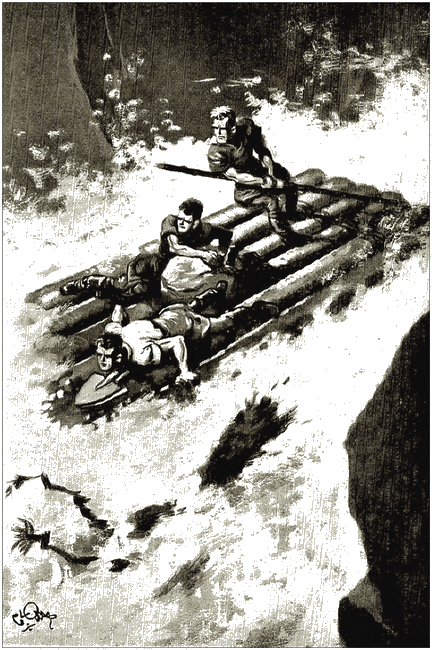

Frontispiece: Bruce force his arm up.

"Up the hill keep climbing—climbing,

Hard am de road, weary de feet."

YOUNG Peter Carr's voice rang out cheerfully in the old negro melody as he tramped up the steep, rocky bush path. Though his round fourteen-year-old face was brown as a berry and his bare legs and arms burnt to an even darker hue by the fierce sun of New Guinea, no one could ever have mistaken him for anything but an English boy. He wore shorts and a flannel shirt and carried a light shot gun on his shoulder.

"Shut up, you ass!" A face appeared over the top of a boulder a little way up the steep slope. A face so like Peter's that there was no doubt about the relationship between the two. "Shut up, can't you? There's a brush turkey just ahead."

A brush turkey! Peter was all eagerness, for he and his brother Bruce had shot so much over the bush around their father's plantation that weeks, and the mere thought of such a prize made their mouths water.

"I saw him run into that patch of bush," explained Bruce as Peter joined him. "But I expect you've scared him a mile with your beastly noise.

"Don't worry," said Peter cheerfully. "We'll have him all right. That patch of brush is only about fifty yards wide. I'll go round and drive the beggar and you shoot him as he crosses the path."

"All right," said Bruce mollified. It was really rather decent of Peter to act as beater. Peter at once slipped away round to the far side of the patch of brush, and Bruce took his stand on the path. These brush turkeys do not fly much, but they run like rabbits and you need to be pretty nippy to kill one crossing a narrow opening.

Five minutes passed. Bruce could hear Peter tap-tapping his way through the thick thorny brush. He stood tense, his gun ready and his eyes fixed on the rocky path which ran straight and steep up towards the top of the ridge above.

A sudden flap of heavy wings. The turkey, instead of running as usual, had risen out of the scrub. Bruce could see its heavy body against the dull green of the trees beyond, and its short wings beating furiously. Up went his gun to his shoulder, his finger was on the trigger, yet he never fired. He stood as if struck to stone, staring at the figure that had suddenly appeared right in the line of fire at the head of the ridge less than fifty yards away.

"What's the matter? Why didn't you shoot?" Peter's voice was sharp with disappointment.

"Couldn't. Someone coming."

"Someone coming!" Peter's tone had changed to one of amazement. "A native?"

"No, a white man." By this time Bruce was hurrying forward. "Quickly, Peter. There's something wrong." Judging by the looks of the newcomer, there was something very wrong indeed for he was reeling and stumbling as he came down the slope. He was a tall man of fifty or so, thin to gauntness. His unshaven face was ghastly in its yellow pallor. His clothes were rags, and he had no gun. A small but heavy looking bundle hung on his back.

Peter burst out of the scrub and the two brothers raced towards the newcomer. He pulled up as he saw them. He was swaying on his feet and the two sturdy boys caught hold of him, one on each side.

"What's the matter?" Bruce asked.

"Done," said the man hoarsely. He was panting and sweat matted his hair and ran down his face. "Niggers after me." He paused and looked back. "No good. Save yourselves. They're bound to get me."

"Don't talk rot." Bruce's voice was curt. "We've both got guns, and anyhow I can't see any natives."

"They're in the bushes—stalking me. Followed me two days. They're Oroko's men."

"My hat!" gasped Peter. "That's bad. I never knew 'em come down so far as this. They must want you badly."

"You bet they want me," said the tall man grimly. "I've had to kill seven of 'em including Oroko's own brother." Peter turned to Bruce.

"Too far to get him to our place," he said swiftly. "What about the cave?"

"That's the ticket," agreed Bruce. He turned to the stranger. "We've a cave close by. Not a quarter mile. If you can get that far you'll be all right." The tall man braced himself.

"I'll have a darn good try anyhow. I'd hate to let those swine crow over me after dodging 'em all this time."

"Give me your bundle," said Bruce. The tall man handed it over without question, and Bruce was amazed at its extraordinary weight. As he slung it over his shoulder Peter who had been looking back along the path suddenly flung up his gun and blazed off both barrels. As the shot tore through the foliage a high pitched shriek ran out.

"Tickled him up anyhow," the boy remarked coolly as he thrust fresh cartridges into the breech. "That'll check 'em a minute and next time I'll give 'em buckshot. Bruce, you take him on while I act as rearguard."

Bruce strode back down the path and the tall man, relieved of his heavy pack, managed to follow. Just below the scrub, Bruce turned sharp to the right across a patch of fairly open ground which rose steeply to a ridge of rock. There was a rustle in the scrub and suddenly a spear came whizzing through the air. It fell short, but even before it fell Peter's gun roared again and the report was followed by a piercing yell.

"Buckshot that time," said Peter. Whatever it was, it seemed to discourage the natives, for nothing more was seen or heard of them until the three fugitives had reached a tunnel-like opening which dipped into the very bottom of the limestone cliff. The tall man hesitated and looked back.

"It's all right," Bruce assured him. "They can't get in here so long as we have cartridges."

"But afterwards," said the tall man grimly. "These fellows won't give up very easy."

"Time to think of that when we're inside," Bruce answered and led the way up a short slope into a good-sized rock chamber. The tall man dropped on a slab of rock and drew a long sighing breath. Peter went off to a corner where a tiny drip of water filled a clear pool, dipped an old beef tin in it and brought it across.

"My word, but that's good," declared the tall man as he drank. "I suppose you chaps haven't anything to eat?" Peter fished a packet wrapped in newspaper from his haversack.

"Just a sandwich," he said, "but it's better than nothing."

"I should just about think it was," replied the other as he bit into it hungrily. "Anyway it's my first mouthful for two days and nights." Peter looked at him admiringly. "You must be pretty tough to have stuck it."

"I'm glad I did," said the other. "It's something to see white faces again before I go out."

"You're not going out," said Peter sharply.

"I'm booked," said the tall man quietly. Then he calmly changed the subject. "You're Tudor Carr's boys."

"Do you know dad?" asked Peter in surprise.

"Well. My name is Cosby Dane." Peter's eyes widened.

"Cosby Dane. Then, of course I've heard of you often. I say, it was you who were with dad in the Solomons." Before the other could answer Bruce, who had been in the tunnel, called out:

"They're coming, Peter."

"I knew they would," said Dane. "What's more, they'll stick like leeches. And I've no gun. I chucked it away after I'd used up all my cartridges. Now I've simply got you lads into a peck of trouble."

"Don't worry about us, sir," said Peter. "As soon as you're rested we'll shift." Dane looked hard at the boy.

"I'd like to know where you mean to shift. By this time they're all round the entrance and even your guns won't save you from their spears."

"That's all right," said Peter calmly. "We know this cave pretty well, and there's a back entrance as well as a front."

"Strikes me I've fallen on my feet," said Dane with a smile that changed his face wonderfully.

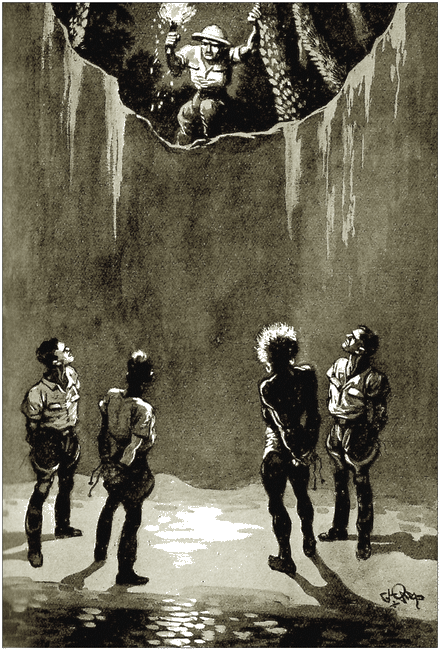

"I'm feeling a lot better, thanks to your sandwich. Lead on." Peter called to Bruce, then led the way back through the cave. There was another passage behind which took them into a second chamber larger than the first, and lighted by a hole in the centre of the roof.

"But we can't get out there," said Dane, for the opening was ten or twelve feet above their heads.

"We've a better way than that," Peter told him, and keeping round the right-hand wall of the inner cave proceeded to scramble on to a ledge. Bruce followed and between them the brothers helped Dane up. From this they gained a second ledge and just above, hidden by a jut of rock, was a narrow hole in the wall.

"I say, I hope you can get through, Mr. Dane," said Bruce in sudden alarm. "It's pretty small."

"I can try anyhow," replied Dane. "Luckily, if I'm long, I'm thin." Peter went first. Dane followed and Bruce waited. The opening was not much bigger than a fox's earth and Dane had a hard time squeezing through. But with Peter's help he managed it and presently the three were out on top of the ridge which was covered with big stones, among which grew a sort of low brush with greyish leaves. Dane sat on the ground. He was breathing hard and his lips were blue.

"We're safe for a minute," he said, "but those beggars will certainly trail us if we start down off the ridge."

"We didn't think of starting just yet," said Bruce. "It wouldn't be any fun having Oroko's men on our trail." Dane looked puzzled.

"How are you going to stop 'em?"

"We thought we might box them up. We can if they come into the cave." Dane gave a low chuckle.

"You're lads after my own heart," he said. "All right. I'm game to sit here from now till to-morrow. Rest is the one thing I need most."

Bruce began operations by stopping the hole through which they had come, then he and Peter moved over to the central opening and watched. An hour passed, nothing happened, the sun was getting low and a little coolness came into the sultry air. The boys were growing anxious, not on their own account, but on that of their father. If they did not come home he would probably start to look for them, and how could they warn him of his danger?

"We shall have to sneak off?" said Bruce in Peter's ear, and just then came a rustle from below. Peter nudged Bruce.

"They're there," he whispered. "Get to it, Bruce."

THE two stole away towards the edge of the low cliff above the outer cave mouth. Bending double, they were quite hidden by the close growing bushes. Just above the mouth lay a pile of big stones. The odd thing was that the boys themselves had had nothing to do with piling those stones which looked as if they had been there for centuries. Yet there was no doubt that the people who originally piled them had done so for the very purpose for which the boys were now going to use them—that is to block the mouth of the cave.

And these stones were so cleverly stacked that it was only necessary to lever out one or two at the bottom for the whole lot to topple over. But before doing this it was necessary to see if any of Oroko's men were in sight beneath, so Peter went down on his stomach and wriggled to the edge.

"Three of 'em," he told Bruce as he came back.

"Only three," said Bruce in a relieved tone.

"All right. You keep your gun on 'em while I start the rock pile." He crept round and got to work.

The three Papuans, big fuzzy-headed brutes, black as sin, and ugly as apes, were standing a little back from the mouth of the cave. If they had looked up they couldn't have helped seeing Bruce, but they never thought of doing so. Their eyes were fixed on the opening like terriers waiting for a rabbit to bolt. Quite calmly Bruce drew out the first stone and so accurately balanced was the pile that he felt the whole thing quiver and hastily drew back. As he did so he made just noise enough for the quick-eared savages to hear him.

Instantly two of them drew back their arms to launch their throwing spears, but Peter's gun barked and two charges of fine shot set them dancing and yelling. Next instant over went the whole rock pile, falling with a tremendous roar. This was too much for the nerves of the niggers who bolted as hard as their legs would carry them.

"Topping!" said Peter gleefully as he noticed how neatly the rocks had blocked the opening. "I wonder how many are inside."

"The more the merrier," said Bruce. "Now let's get home. They won't be so full of beans after a few hours in the dark. Hulloa, here's Mr. Dane."

"You're a couple of young wonders," said Dane with deep approval in his sunken eyes. "You may have done a better day's work than you know. Now we might as well get home. Your dad will be getting anxious."

Tudor Carr was anxious. They met him a mile from the house. But his anxiety was changed to amazement when he saw Cosby Dane and heard about his rescue. By this time Cosby was nearly done, and as soon as they got him to the house Mr. Carr gave him hot coffee laced with brandy. Meantime Paloa, their head boy, a big fellow whose fuzzy hair was whitened with lime and who wore a ring in his nose, got ready a hot bath.

Half an hour later when Cosby Dane came down to supper, clean shaven and dressed in a suit of their father's white drill, they hardly knew him. From a ragged tramp he had turned into a remarkably handsome man. With his deep-set grey eyes, hawk nose and grizzled hair he was a very striking looking person.

"You've got my bag, Bruce?" he asked as they sat down to table.

"Quite safe, sir," replied Bruce. "It's in dad's strong box." The other nodded.

"A good place for it. Do you know what's in it?"

"Lead by the heft of it," laughed Bruce.

"Better than lead, my lad. It's gold." Bruce gasped.

"But it weighs all of forty pounds."

"Just about, I reckon. Good stuff, too. Worth all of six pounds an ounce."

"Great Scott! Cosby! Where did you get it?" asked Mr. Carr.

"In Gloom Gorge," replied the other briefly. Mr. Carr leaned forward. "I've heard of that place, but I thought no one could get into it. Crowder, who told me, said it was simply a crack in the mountains walled in with precipices a quarter of a mile high."

"Not a bad description," allowed Dane. "But we found a way down and I'm hardly exaggerating when I say the bottom is paved with gold. I could have brought half a ton if I'd had any means of carrying it."

"Paved with gold," repeated Mr. Carr whose thin face had gone suddenly tense. "Do you really mean it, or are you pulling our legs?"

"I mean it, every word, Tudor. There must be a huge lode of virgin gold somewhere in those mountains and the river has been washing it down for ages; wherever you can find a pool shallow enough to pan, you get dust and nuggets in such quantities as I have never seen. And I was in the Klondike in Ninety-nine."

"A little of that gold would go a long way with us, Cosby," said Mr. Carr, and he spoke very earnestly. "This plantation has hardly begun to pay yet, and I badly want to send these boys of mine to a decent school. They're good chaps, as you can see for yourself, but at their age they have no business to be running wild in the bush. If you'll tell me how to get to this Gorge I should feel like trying my luck there." Cosby Dane raised his thin hand.

"Don't dream of it, Tudor. No amount of gold will pay for a man's life and that's the cost of such a trip. It's Poison Country up there, and though I have come out of it alive, I am done for. I shall not live to enjoy the little fortune that I have brought out."

"Come now," began Mr. Carr, but Dane stopped him. "I'm telling you the literal truth. I am so full of fever that I know I cannot live long. I doubt if I shall last another month."

Mr. Carr looked at his friend with troubled eyes and noticed the leaden colour of his skin and his terrible thinness.

"I hope you're wrong, Cosby, but it doesn't follow that everyone is equally liable to these fever germs."

"If there were no fever at all the odds are all against anyone getting that gold," Dane said gravely. "The whole journey is perilous to the last degree. The natives are treacherous and hostile. Even now I can't understand how I passed them. Then travelling through that bush is next to impossible. The country is the worst I ever crossed. It is like a flight of stairs, each step of which is a sheer precipice varying between fifty and five hundred feet in height. The lower ground is infested with snakes, in the upper part it is nearly always raining or else thick mist hangs over the dripping forest. If I had known what I was going to face before I started, all the gold in New Guinea would not have tempted me to try so mad an enterprise."

"It sounds pretty bad," said Mr. Carr doubtfully.

"It couldn't be worse," was the reply. "To that I give you my word. As it is, I have lost my two faithful boys. One was taken by a croc, the other killed by a poisoned spear. No gold is worth such a risk."

Mr. Carr sighed. It was true, what he had said, that he wanted money sadly for the education of his boys. The coco-nut plantation would not be in full bearing for another four or five years and by that time it would be too late to send Bruce and Peter to school. Yet from what Cosby Dane had said it was hopeless to think of the gold in Gloom Gorge. Cosby changed the subject.

"What are we going to do about these niggers?" he asked.

"I've sent a boy in a canoe up the coast to Lanok, with a note to Cleave, the Police Commissioner. He'll attend to them," said Mr. Carr.

"He'll let them loose, I'm afraid," said Dane regretfully.

"Not till he's scared 'em pretty thoroughly," replied the other with a smile. "John Cleave is a good man." They went out on the veranda which was screened with wire gauze against mosquitoes and sat and chatted, but Dane tired and they took him to his room and made him comfortable.

"It's just Heaven to lie in a civilised bed once more," he told them gratefully. "But for your boys, Tudor, I should be providing a feast this minute for Oroko's ruffians. Believe me, I shan't forget what I owe you."

"Do you think he's as bad as he believes he is?" Peter asked his father as he bade him good night a little later. Mr. Carr shook his head.

"He's pretty bad, Peter. I don't like that blue look about his lips. It means that his heart is affected. But we'll take good care of him, and I hope he'll pull through."

Next morning Cosby Dane came down to breakfast, but he could not eat. He only drank a little coffee. An hour later he was shivering in a violent chill. They put him to bed again, piled blankets on him and gave him quinine and hot drinks, but they could not break the attack, and presently the lever fit followed and the poor fellow lay raving in delirium. The boys took turns to watch him and from his broken words they learned nearly everything of his terrible journey to and from Gloom Gorge.

Late in the afternoon the fever left him, but he was too weak to move.

The boys hovered about unhappily. They were dreadfully anxious.

"I hope to goodness he'll pull through, Peter," said Bruce. "It would be too rotten if he died after all he's been through."

"He's not going to die," vowed Peter.

"If we'd only got a doctor," sighed Bruce.

"Dad's as good as a doctor," Peter told his brother. "There isn't much he doesn't know about fevers."

"He's pretty good, I know," allowed Bruce. The afternoon dragged on. Now and then they heard voices coming faintly through the open window, but could not make out words. The sun was down and it was nearly time for supper when at last their father came out of the room where Cosby Dane lay.

"How—how is he?" asked Peter anxiously.

"Better. I think he'll pull through."

"Hurray!" Mr. Carr raised his hand.

"Quietly, Peter. He's asleep. Come into the other room. I have something to say to you." They followed him and he closed the door.

"I have a message for you from Cosby Dane. Even if he recovers, his heart is so weak that he will have to live quietly and he has decided to stay here with us."

"Good!" exclaimed both boys together.

"Wait. That is not what I have to tell you. He insists that his gold shall be used to give you schooling."

"What a brick!" said Peter.

"You're right, Peter. He is a brick. Now the question is to find a good school. There is no need to send you back to England, for there are capital schools in Sydney."

"But do you know of any, Dad?" asked Bruce.

"No, but I can find out. My brother, your Uncle Ralph, lives in Sydney. I haven't heard from him for years, but he's a good chap. I shall send him the gold and a letter asking him to find you a school and as soon as we hear you shall both go."

"WILL you sign the receipt for this, sir," asked the Express Company's messenger, who had just brought a small but heavy box into the handsome Sydney office of Mr. Ralph Carr. The tall young man who was seated at the desk with a cigarette between his lips rose and brushed a few specks of ash from the lapel of his well-cut coat.

"Give it to me," he said in a languid voice, and taking the paper signed it with the name 'Paul Bassett.' The other took the paper and left the room, and Paul went across to the chair on which the box lay and examined the label.

"What the deuce is it?" he said with a slight frown. "Lanok. I wonder where that is." He stooped and lifted the box and a surprised expression came into his sleepy blue eyes. Queer eyes they were, with a sort of smoky look in them.

"Heavy as lead," he remarked. Then he shrugged his shoulders. "Another of those heathen gods that old Ralph collects, I suppose," he said. "Well, it will have to wait until he comes back. I'm not going to unpack the beastly thing." He went back to his desk and picking up a slim steel knife, began to slit open the pile of letters that had come by the morning post. Some went straight into the wastepaper basket, some were filed, some set aside to answer. Presently he picked up an envelope so soiled and crumpled that it looked as if it had been kept in somebody's pocket for a week.

"What a filthy mess," said the elegant Paul with disgust, then suddenly those odd eyes of his gleamed. "Post mark, Lanok," he murmured. "Perhaps this explains the ton o' lead." He unfolded a closely-written sheet of thin paper, and as he read it all the sleepiness went out of his eyes and you could see that Master Paul Bassett had quite another side to his character than the indolent pose he usually showed to the world. He read the letter twice, then dropped it and sat staring straight in front of him.

"This is a nice mix-up," he said in a low, angry voice. "So Ralph has a brother alive and two nephews, and he's never said a word to me about them. And Tudor wants to send his boys here to school." He sat frowning, drumming with the tips of his beautifully manicured fingers on the table and thinking deeply. Paul Bassett had come into Ralph Carr's service five years earlier as clerk, and had made himself so useful to the wealthy bachelor that he had become his confidential secretary. But Paul, who was a pushful young man with a great idea of Number One, had no idea of remaining in any subordinate position. His idea was to get Ralph to adopt him and in the end to succeed to the great fortune which he had recently made by clever speculation.

This letter from Tudor threatened to upset his applecart, for Paul was shrewd enough to see that the arrival of two nephews would be quite enough to change all his prospects. Presently he got up and went across to the chair on which the box lay. He opened it carefully and gasped when he saw the mass of rough virgin gold in flakes and nuggets that filled it. He had never before seen gold in the rough, and the sight of it affected him oddly.

"So it's good goods," he said to himself slowly. "And when Ralph sees it he will be tremendously impressed, and I'll lay he'll send off for these confounded boys to come by the next boat." He was silent again, and by the lines on his forehead, thinking hard. At last he spoke. "Why should he see it," he asked himself. "After all, there's no reason why he should see it—or the letter." He gave a low chuckle. "I know how to fix it and I've plenty of time, for Ralph won't be back till tomorrow night." He turned to the desk again, took up a pencil and a pad and wrote as follows:

Dear Sir,

Your letter of March 15th last has reached this office to-day together with the box of gold consigned by s.s. 'Auckland.' I regret to have to inform you that your brother, the late Mr. Ralph Carr, died in June of last year. This office is now in other hands. Under the circumstances I have no choice but to return to you the box of gold, addressed to your brother, and express my regret that I am not able to be of further service to you.

Yours faithfully,

Humphrey Hedworth.

He slipped a sheet of paper into the typewriter and was about to make a fair copy of this precious effusion when another idea came to him and he scowled more angrily than before.

"This is no good," he muttered. "If Tudor Carr gets the gold back, next thing will be he'll come down to Sydney himself to look for a school for his brats. Then the fat will be in the fire, for he's bound to hear that Ralph is still alive. I've got to fix it so that the gold never reaches him." He thought again for a little, then his lips curved in an unpleasant grin.

"I've got it," he said. "Salter's my man." He locked away the rough draft of the letter, took up his stick, hat and gloves, and left the office, locking the door behind him. Outside he took a taxi and ordered the man to drive him to the docks. Here he paid off the driver and made his way down the crowded wharves until he came opposite a slovenly-looking schooner whose dirty decks matched her scarred sides. A very black native was leaning on the rail smoking an even blacker pipe, and Paul hailed him.

"Hi, your fellow marster aboard?"

"Him oboard," was the reply, and Paul crossed the gangway and went down the narrow hatch into a long, low-roofed, extremely-dirty cabin.

The man who rose to meet him was about as like a rat as it is possible for a human being to be. His nose was sharp, his keen little eyes were rimmed with red, and he carried his head poked forwards. A small, bristly moustache stuck out on each side of his mouth and his teeth were long and yellow. This was Captain Stephen Salter of the schooner Kiwi. He thrust out a dirty hand.

"Blimey if it ain't Mister Bassett," he said in a high-pitched whine. "Pleased to see yer, Mister Bassett, an' wot brings yer down 'ere ter see yer old friend?"

Paul repressed a shudder of disgust.

"You're sailing for Thursday Island, aren't you, Captain?"

"Aye. You wanting a trip?"

"No, but I've a parcel to send to a place a bit further on—a little port called Lanok in New Guinea."

"I knows it, but it's a goodish way. I'll need ter be pyde fer a trip like that."

"The pay is good," said Paul. "Listen now." He lowered his voice to a whisper, and spoke for some minutes. Salter's thin lips twisted in a grin.

"If you ain't a oner, Mister Bassett! I sees. The letter's ter get there, but the parcel, that don't." He chuckled and the sound made Paul shiver—there was something so ugly and evil about the laugh.

"AYE, I'll do it," resumed Steve Salter. "I kin do it, but"—he held up a dirty forefinger—"we got ter be careful."

"Of course we've got to be careful," replied Paul impatiently, "but there's no risk to speak of."

Salter nodded. "Not fer you, maybe, fer no one ain't a going to suspect you, but I gotter think of myself."

"All you have to think of is that you've a lump of luck coming for next to nothing," retorted Paul. "You'd better come back with me now, and get the box and the letter." Salter shook his head.

"Not me, mister. I ain't a coming ashore agin afore I sails. I'm safer aboard here—see?" he added significantly.

"I suppose you mean you have creditors ashore, who might make it hot for you," said Paul rather scornfully.

"Creditors—and worse." Salter drew his finger suggestively across his throat. "No, I ain't going up to your place, even ter get this here lump o' luck you talks about. You gotter bring it yourself. See here, now, you go back and get it and wait till dark. Then take a taxi. I'd change half way and take another if I was you. Come aboard about eight and have a bite o' supper with me. Oh, you don't need to worry," he added quickly. "My cook's slap up and I can give you a proper good feed." Paul hesitated. He did not in the least want to feed in this dirty ship with its unshaven skipper, but on the other hand he could not afford to offend Salter.

"All right," he said at last. "I'll come."

"Good fer you," said Salter heartily. "And I'll put some ginger into that cook o' mine. I'll promise ye won't be disappointed." As Paul returned to the deck a man was coming aboard, a man whom Paul had never seen before. He was short, deep-chested, with a skin so dark he might well have been an Asiatic. But his black hair was curly, not straight, and something about him suggested that he had European blood. He wore a clean suit of white ducks, brown shoes and a broad-rimmed hat of very pale grey felt. Salter introduced him.

"My mate, Joao Suarez," he said. "Ain't a man alive as is better at getting work out of a pack o' lazy niggers." Paul could believe it, for there was a look in Suarez's dark eyes which made Paul shiver inwardly. Little as he liked Steve Salter, he infinitely preferred him to his mate. He gave Suarez a civil word, and went ashore.

Paul knew perfectly well that he was doing a dirty trick and he was not happy. But although his conscience pricked him he had no idea of giving up his plan and as soon as it was dark he took a taxi and started. The gold was in an old suitcase, and the letter in his pocket. Half-way he changed cabs, as Salter had advised, and a little before eight he was aboard the Kiwi.

"You got your bag, I sees," said Salter, and Paul realized that this remark was for the benefit of the crew. They were not to know the value of the contents of the case. "Come right along down. Supper'll be ready most as soon as we are."

He took Paul into his own cabin, and eagerly opened the case. Paul saw the covetous gleam in the man's eyes as he lifted the bag of gold and judged its weight. Then he cut it open and his eyes glowed again as he ran his fingers through the mass of small nuggets and dust.

"Gee, Mr. Bassett, I dunno how you kin make up your mind ter part with this," he remarked with a sharp glance at Paul's face.

"I've told you my reasons," replied Paul curtly.

"I wouldn't say they were bad ones," returned Salter, "but you was right when you said this was a lump o' luck. A few more lumps like this here, and I'd go right back to London town and live like a gent." Paul spoke:

"You'll give me a receipt for this." Salter fixed his beady eyes on Paul's face.

"What yer want a receipt fer?" he asked suspiciously.

"In case there's any trouble. Suppose the owner came down to Sydney, you can see for yourself I must have something to show for all this gold."

"And wot about me?" demanded Salter in a voice that was suddenly surly. "You reckoning to put all the trouble on my shoulders?"

"Don't be foolish. The risk is next to nothing, and anyhow you can say you were robbed or wrecked or something."

"I ain't giving you no receipt," growled Salter.

"Then there's nothing doing, and I shall take the gold back and find some other way of disposing of it." Paul spoke with a sharpness which had its effect on Salter. He picked up some of the gold and handled it as if he coveted it. There was silence for some moments, then Salter looked up again.

"All right," he grumbled. "If you insists I suppose I got to do it." He went to the table, took a sheet of paper from a drawer and a rusty pen from a stand. Then sitting down and squaring his elbows he wrote a few lines, and handed the paper to Paul.

"That do?" he asked. Paul read it.

"That's all right, if you will sign it—and date it."

Salter did as he was requested and Paul folded the paper and placed it in his pocket book. Then Salter shut up the suitcase, locked it, and thrust it into an old iron safe which stood against the wall. This, too, he locked and stood up.

"An' now we'll go and have some supper," he remarked, and led the way into the main cabin. A meal was ready on the table and it looked and smelled better than Paul had expected. There was a joint of roast pork with vegetables, and some quite nice looking fruit, pine-apple, oranges and guavas. Suarez came in looking smart in his white ducks and the three sat down together.

Suarez, Paul gathered, was a half-bred Portuguese and Malay, but he appeared to have been well educated and talked infinitely better than his skipper. He seemed to have knocked about all over the South Seas, and had plenty to say about his travels. He told some wild stories of adventures on the coast of Malaita, that most dangerous of the Solomon Islands, with its steaming jungles, smoking volcanoes, and man-eating savages. Paul was so interested that he sat listening eagerly for more than an hour after supper was finished.

All of a sudden it occurred to him that the schooner was moving. He listened a moment, and made sure that the engine was running. He started up.

"We're moving," he said sharply.

"Don't worry about that, mister," said Salter with a laugh. "We're only changing berth so as to be ready fer the tide at six tomorrer morning." Paul dropped back in his seat. He had no real reason to be uneasy and yet he was. Presently he declared that it was time for him to go, and it seemed to him that he caught a swift glance pass between Salter and Suarez. Panic seized him and leaping up he rushed on deck.

It was a bright night with a moon just past the full rising out of the sea, and the first thing Paul noticed was that the ship was at least five miles out from the wharf where she had been lying and steering straight for the Heads. He heard steps behind him, and turned.

"You swine!" he cried furiously as he saw the grin on Salter's face. Salter laughed.

"Took me fer a sucker, didn't you, but I ain't. If you think I'm going to be lagged fer stealing that there gold you got another guess coming. It's you as has took it." Paul's temper went to the winds, and he flung himself furiously on Salter. A leg swiftly thrust out by the little Cockney tripped him and down he came on the planking of the deck with such a thump as knocked all the senses out of him. When they came back he found himself lying on his back on the bare boards of a bunk in a small, stuffy and very dirty cabin and by the motion of the schooner he knew that she was beyond the Heads and out to sea. He struggled up only to fall back, sick and giddy, and for many hours he lay there so seasick that he hardly cared whether he lived or died.

THE rainy season was nearly over, but the coast lands of New Guinea still reeked with moisture and the hot air was full of the hum of insect life as the three Carrs and old Cosby Dane sat together on the veranda after supper. Out in the darkness a bell bird was sounding its curious call like a clapper striking on a gong of bronze, and in the swampy edges of the creek a great bull alligator bellowed now and then.

Peter spoke.

"I say, Dad, oughtn't we to hear from Uncle Ralph pretty soon. It's jolly near four months since you wrote to him." Mr. Carr knocked out his pipe against the arm of his chair.

"Yes, Peter, it's quite time we heard. His letter may be at Lanok this minute, and I think we'd better send a boy to-morrow to see if it's there." Before anyone else could speak a low growl was heard and Dingo, the big cross-bred Airedale, rose from beside Tudor Carr's chair.

"What's up, old man?" asked his master.

"Must be someone about," said Peter. "Look how he's bristling."

"Funny!" remarked his father in a puzzled voice. "It's no time of day for natives to be about." This was true, for the superstitious Papuan, bold enough in the day, is dreadfully afraid of the dark and if it is necessary to be abroad after nightfall usually goes in company.

For a few moments all sat very quiet, listening. Then Dingo growled again, deep in his throat, and all of a sudden a shadowy figure showed in the starlight in the open ground fronting the house.

"Who's there?" demanded Tudor Carr sharply.

"A friend," came the answer in good English, but with a slightly foreign accent.

"Come into the light," answered Mr. Carr.

"Down, Dingo!" he added, and caught the dog by the collar.

All craned forward to watch the newcomer, who advanced into the light thrown through the open window by the big paraffin lamp in the sitting-room. They saw a stockily-built dark-faced man dressed in what might once have been white ducks but were now mere mud-stained rags. He staggered as he walked and seemed to keep himself upright only by the stout stake he carried.

"Hold Dingo, Peter," said Tudor Carr, for the dog was straining forward and still growling angrily, then getting up he went forward to take a closer look at the strange visitor.

"What's your name and where do you come from?" he asked.

"My name is Suarez. I have a letter for Mr. Carr."

"That's my name. You can give it me." Suarez took a grimy, mud-stained envelope from the pocket of his ragged jacket and handed it over.

"May I sit down," he asked. "I'm nearly done."

Tudor Carr nodded.

"Sit on the steps a minute. If you're all right we'll look after you, but we have to be careful about strangers."

"I can understand that," said the other hoarsely, as he dropped on the steps and sat all in a heap, looking utterly exhausted. Tudor Carr took the letter to the window, opened and read it by the light of the lamp. Peter, watching him, saw his face change and knew that something was badly wrong. But he did not speak. Tudor Carr banded the letter to Cosby Dane and he, too, read it.

"A nice business?" said Tudor Carr. Old Dane frowned.

"A queer business. But where's the gold? Tell that fellow to come up here." Mr. Carr called Suarez up.

"Do you know what is in this letter?" he questioned.

"I can make a pretty good guess at it," was the answer. "Mr. Hedworth, who wrote it, brought it aboard the schooner Kiwi, of which I was the first mate, and asked Captain Salter to take it and a package to Lanok."

"And where is the package?" Suarez shrugged his shoulders.

"At the bottom of the sea, with the schooner."

"What?" cried Tudor Carr. "Wrecked!"

"Yes," was Suarez's quiet answer. "We ran on Dutch Shoal two nights ago in a thunder squall. The sea knocked the schooner to bits and so far as I know I am the only one who got ashore." For nearly a minute there was a dead silence broken only by a rumbling growl from Dingo. Peter had to hold the dog firmly. Dane was the first to speak.

"Bad luck, Tudor. And worse luck still that your brother is dead." Tudor Carr sighed heavily.

"It's a bad—bad business, Cosby. I don't know what we shall do."

"The first thing to do is to buck up," was Cosby Dane's answer. "The gold's gone. That can't be helped, and I'm sorry, for the boys' sake. But, after all, they're fit and well and so are you, and sooner or later your plantation will pay, and all will be well. The second thing, if I may remind you, is to give Mr. Suarez some food and a bath. He looks as if he needed them both."

"You are very kind, Señor," said Suarez. "I am indeed in need of food, for I have eaten nothing except some guavas since I got ashore." Tudor Carr roused to a sense of his duties as host. "Bruce, call Paloa and tell him to make some coffee and put some supper on the table." He turned to Suarez. "Come with me," he said, and Suarez followed him into the house. Bruce came back to where Peter and Cosby Dane were sitting.

"This is a bad job," he said gravely.

"Rotten," agreed Peter. "Dad's frightfully upset."

"That's the worst part of it," said Cosby Dane. "He's been so set on getting you boys away to school that the loss of this gold is a nasty shock to him."

"But, after all, you're right, sir," said Peter. "So long as we're fit we can always get along all right."

"We shall have a job to persuade dad of that," said Bruce uncomfortably. "He takes things like this so hard. And it's rotten," he added angrily. "It makes me sick to think of losing all that gold that cost you such a lot of getting, Mr. Dane."

"It's a sight worse for those poor folk in the Kiwi," said Cosby Dane in his quiet way.

"That's true," said Bruce thoughtfully. "All right, Mr. Dane, I'll try not to grouse any more." Dingo growled again as Mr. Carr and Suarez came into the dining-room. Suarez was wearing a suit belonging to Mr. Carr and had had a wash. He looked almost smart, but Dingo did not seem to like him any better. The native boy, Paloa, brought in a tray and Suarez began to eat hungrily. While he ate Mr. Carr questioned him about the wreck.

Suarez said he had managed to get hold of a floating hatch cover when the schooner broke up and had drifted ashore on it. He had had a bad time clambering through the mangrove swamp that lined the shore and had had a very narrow escape from an alligator.

"I was very grateful when I saw your light, sir," he added. When he had finished his meal he asked if he might turn in. "I'm so sleepy I can hardly keep my eyes open," he confessed, and Mr. Carr took him to the spare bedroom. Then he came back and joined the others on the veranda.

Bruce was right. His father was terribly upset about the loss of the gold. He blamed himself bitterly for sending it instead of taking it to Sydney, and nothing that the rest could say seemed to comfort him.

"You nearly gave your life for it, Cosby," he said, "and now I've let it all go. I can't ever forgive myself."

"Worrying won't do you any good," said Dane in his calm way. "There's a lot of truth in that old proverb about spilt milk."

Bruce and Peter shared a room. Later, when they were undressing they talked.

"What do you think of this fellow, Suarez, Peter?" Bruce asked.

"Not a lot," replied Peter frankly. "He's some sort of half breed, and dad's always said they're no good. And Dingo simply hates him."

"I noticed that," agreed Bruce. "We'll have to keep the dog tied up until Suarez leaves, or he'll go for him." He pulled the mosquito net aside and got into his cot.

"I don't know what we shall do about dad," he added.

"There's only one thing to do, said Peter.

"What's that?" demanded his brother.

"Get some more gold." Bruce stared.

"How?"

"There's more where that came from," said Peter coolly.

"You're crazy," retorted Bruce. "We couldn't get it."

"I don't see why not. We know it came from Gloom Gorge. Cosby has told us the way so often I believe I could find it blindfold. Why shouldn't we go and have a shy at it?" Bruce sat on his cot gazing at his brother with a worried expression on his good-looking face.

"That's true enough so far as it goes, Peter, but what about the fever and the floods and the niggers? If the trip nearly killed Cosby what earthly chance should we have of getting through?" Peter was not at all dismayed.

"We're a lot younger than Cosby; we're pretty nearly fever proof. We know New Guinea about as well as any chaps can—well enough, anyhow, not to run ourselves into trouble. Honestly, Bruce, I can't see why we shouldn't do it all right." Bruce sat frowning and Peter watched him in silence. Outside an owl hooted and somewhere in the house a board creaked. At last Bruce spoke.

"Dad would never let us," he said.

"Of course he wouldn't, but why should he know? You and I have often been out and away shooting for two of three days at a time."

"But not alone," said Bruce.

"No. Dad's made us take Kinabula with us, but why shouldn't he come on this trip?" Bruce grunted and Peter went on.

"It's not so awfully far. We go up the river as far as Split Rock, That takes a day. Then we take the left hand branch and carry on as far as the rapids. We portage round them, then about three days paddling brings us right to the foot of the big hills. After that it's only a matter of going straight north. You can't miss Gloom Gorge, Cosby says, for it's about twenty miles long." He stopped again and watched his brother. Bruce drew a long breath.

"I'm game," he said at last.

"I knew you were," said Peter with warm approval. Suddenly he stiffened. "There's that board creaking again," he said in a low voice, and tiptoeing to the door in his bare feet opened it. He listened awhile, then closed it and came back.

"All right," he said. "Dad's in bed and so's Cosby, and I can hear that Suarez chap snoring. But we shall have to be jolly careful that no one gets wind of this plan or Dad will put the hat on it."

"When did you think of starting?" asked Bruce. Though the elder by more than a year, Bruce always deferred to his younger brother when there was any big decision to be made.

"The sooner the better. The rains are just about over. We might push off about Monday next." Bruce nodded, but he was still frowning.

"We shall want a lot of stores for a trip like that. We may be away a month or more. How are we going to get them?"

"Buy 'em," said Peter coolly. "We've got about ten quid between us that we've saved up. We'll take the boat to-morrow or next day and go over to Lanok. Grimball at the Store will let us have all we want and we can trust him to keep his mouth shut."

"We shall want shovels and pans," said Bruce.

"We can get the lot and leave them hidden in the little cave."

"There's Kinabula to think of," remarked Bruce. "We don't know whether he'll come or not."

"What a chap you are for making objections!" grinned Peter. "Kinny will simply jump at the chance. He comes from the mountains and he's always been longing to get back there. Now if you're quite satisfied I vote we turn in. We shall have plenty to do in the next few days."

"Don't know how I'm going to sleep with that blighter snoring next door," grumbled Bruce. "He's worse than a pig."

But Peter did not answer, and in spite of the noise which came through the thin boards from the next room, Bruce was soon sound asleep.

AS the boys dressed next morning Peter had a bright idea. "This fellow Suarez will want to go in Lanok. It's the only place he can get a ship, ain't it?"

"I suppose so," said Bruce, "but what about it?"

"Don't be thick. Can't you see what a topping excuse it gives us for a trip to Lanok?" Bruce whistled softly.

"You're right. But suppose he doesn't want to go?"

"Then we must wait until to-morrow. All the same, I don't think he'll stay here long." Peter was right for at breakfast Suarez began to inquire what chance there was of getting away.

"I have lost everything," he said in his soft purring voice. "I shall have to start afresh, and the sooner I do so the better."

"We can send you to Lanok," said Tudor Carr.

"It is some ten miles up the coast."

"I shall be very grateful," replied the half-breed, and then Peter struck in. "Dad, Bruce and I can take him. There's a fair breeze and if we start soon we can get back by night."

"Very well," said their father. "You can go. But you'll be careful." Suarez was full of thanks, and when he was in the boat proved to be a good sailor. Peter tried to get him to talk of the wreck of the Kiwi, but instead of that he told the boys stories he had told the unfortunate Paul Bassett a few weeks earlier, but the boys of course did not know that, and they were much interested. All the same when they reached Lanok and their unbidden guest bade them a polite adieu they both breathed a sigh of relief.

"Something rum about that chap," Peter said, and Bruce agreed. Then they dismissed him from their minds and started to look for Kinabula. They found him in his little house close to the beach. It was no palm leaf shack, but "a proper house" as its owner called it, built of sawn boards and roofed with shingles. True, it only had one room, but that room was furnished with a real stove, a kettle, a frying-pan and a white man's cot, and was decorated with an ancient picture of King Edward in full uniform and a coloured almanack of the year 1906.

Kinabula himself came out to welcome his visitors. He was a Papuan, black as coal and with a great mop of hair bleached with lime. But he wore white man's trousers and shirt and these were wonderfully clean and tidy. Kinabula had been in the native police and had retired with a small pension. Though past forty, which is old for a native, he was a fine built man and still very strong and active, a great hunter, and very fond of the two English boys.

"I very glad to see you," he declared, showing his teeth in a broad grin. "You please come in my house."

"And we're jolly glad to see you, Kinny," said Peter shaking hands. "Yes, we'll come in. We've something to tell you."

"Rains finish. You go shooting," suggested the native.

"Something better than shooting, Kinny," said Peter. "You listen." Kinabula listened in silence and when Peter had finished he still sat silent.

"Won't you come?" asked Peter sharply. "Don't you like the trip?"

"Him fine trip," allowed Kinabula, "but him very bad trip. I tink him Oroko kai-kai us if we go."

"Surely we can dodge him, Kinny. You know the country."

"Only way to do it, go past Oroko's place by night," Kinabula told him.

"Well, let's go by night."

"Him very bad go in dark," said the native gravely.

"We've got to chance it," Peter told him urgently. "Dad wants that gold terribly. Will you come, Kinny?" Kinabula still hesitated.

"One way you go better than canoe."

"What do you mean?"

"I mean him sky boat," said the black man waving his hand upwards.

"Aeroplane, oh, I see. Yes, that would be fine, but there's no 'plane at Lanok."

"White marster, Allen, he have sky boat."

"But he's not here. He's over on the Aird, two hundred miles away and we might be a month getting hold of him, and even then he might not be able to come. We can't wait for Allen. I'm sure we can manage by canoe. Say you'll come, Kinny."

"Yes, I come," said the man simply.

"Hurray for you, Kinny," exclaimed Peter, but Kinny held up a warning hand.

"You no hurray till you get back safe, marster."

"He's about right," said Bruce. "I wish we could get hold of Tubby Allen and his 'plane. This isn't going to be any picnic, Peter."

"I know," said Peter quietly. "Well, the next thing is to get the stores. What shall we want, Kinny?" The native, who knew as much about camping in the wilds of New Guinea as any man, began to talk, and Peter jotted down notes in an old pocket-book with a stub of pencil. This took some time and when they had finished they went through it all again to see roughly what it would cost. When at last it was finished Peter got up.

"Now Bruce, we'd better go to Grimball's and buy the stuff." Bruce shook his head.

"Much better let Kinny do it. If dad heard of our buying such a lot he'd smell a rat." Peter grunted.

"You're right, and Kinny will get the stuff cheaper anyhow. Go ahead, Kinny. We'll wait here for you." Kinny took the money and went. The boys drowsed in the heat. It was an hour or more before Kinny came back.

"You got it?" asked Peter.

"I got him, marster." He paused. "Him breed fellow, him from Kiwi, I see him buy stuff at store."

"Getting a new outfit, I suppose," said Bruce carelessly.

"Him get pretty big outfit," said Kinny. "I link him go trip somewhere."

"He's not likely to be going our way," said Peter with a laugh. "Now, Kinny, we'll go and get ourselves some food, and you meet us on Monday next at the mouth of the river."

"I do that," Kinny promised. "I have boat and all stuff."

The last of the big thunderstorms blew over during the week-end, and on Monday as the boys set out the sky was clearer than it had been for weeks. They had had no difficulty in getting their father's permission for a trip up the creek, especially as Kinabula was to be with them. Since the boys did not want Mr. Carr to be alarmed at their long absence Peter had written a note telling of their real intention, and given it to Paloa, ordering him to hand it to his master in a week's time. Bruce also wrote a letter though he did not tell Peter about it. It was addressed to "H. Allen, Esqre," and he sent it to the post office at Lanok by Paloa. In it he described his and Peter's plan and suggested that, if Allen was not too busy he might like to chip in.

"There seems to be gold enough for all of us up in this place we're going to," he ended.

Kinabula was waiting at the mouth of the Loma, but to their surprise the boys saw he had another man with him—a white man.

"Him name Miley," explained Kinabula. "Him say not want wages. Him know how white men wash gold, and him take small share for wages."

"I hope ye don't make no objection, mates," said Miley who spoke in a sort of Cockney drawl which did not in the least appeal to Peter. "I been stranded there in Lanok fer a month past, and I'd be mighty glad fer a chance of going along. I done three years gold digging in North Queensland so I ain't exactly a greenie. If you fellers'll give me a ten per cent rake off on anything you gets that'll be all hunky." Peter looked him up and down.

"I'll have to talk to my brother," he said frankly.

"Right oh!" replied Miley. "I'll step aside. And there won't be any ill-feeling if you says No." He moved away out of earshot, and Peter spoke to Bruce.

"I don't care for the look of the chap," he said.

"He isn't much to look at," agreed Bruce, "but if Kinny vouches for him it ought to be all right, and a fourth man will make all the difference in working up the river. Two can paddle and two can lay off." Peter nodded.

"That's true, but after all, we don't know anything about him, and he looks a pretty hard case."

"Ask Kinny," said Bruce. Peter called up Kinabula and questioned him. The native knew very little about Miley but thought he was good goods.

"All right," said Peter. "Then we take him, but he's got to understand that he does as we say, and that he only takes a tenth of the gold." Miley agreed, and within a few minutes the four were in the boat paddling upstream.

The river was very full with the recent rain and it was real hard work driving against the flood. At times all four had to paddle. Miley did his share, and before the day was half over Peter had to acknowledge he was very glad of his help.

They stopped for dinner on a beach of clean sand. A lovely spot for the steep banks were covered with croton bushes, the leaves of which, holding every tint of green, red and yellow, made a perfect blaze of colour in the glaring sunshine.

"We've done jolly well," said Bruce. "We're a good half-way to Split Rock."

Instead of answering, Peter caught his brother by the arm.

"Look!" he whispered.

"What at?"

"That man. No, it's too late. He's gone."

"Who was it—where was he?" asked Bruce sharply.

"A native. He was watching us from the top of the bluff opposite. I spotted his head poking out among the branches."

"What sort of a chap was he?" asked Bruce anxiously.

"I'm afraid he was one of Oroko's men," replied Peter, and Bruce whistled softly.

"That's torn it. What do we do—go back?"

"GO back!" repeated Peter staring at his brother. "You're not funking it, Bruce?"

"Of course not, you ass, but what chance have we against Oroko's cannibals? There are dozens of 'em, and after what we did to 'em at the cave you can bet they're just thirsting for our blood. I don't mean to go back altogether," he added, "but go downstream a bit and try some other way."

"There's no other way," said Peter, still gazing at the spot where the mop-haired savage had disappeared.

"Well, we can't stay here," returned Bruce. "That's one thing sure, for as soon as that blighter gets word to the rest they'll be all over us. If we don't go back we must go on."

"We'll ask Kinny," said Peter. Kinabula, busy with a small fire on which he was heating some coffee, had not seen the savage. He listened carefully to what Peter told him.

"It no matter if we go up or down," he said. "Them fella niggers come after us."

"Sounds healthy," said Bruce glumly. Miley, who had been dozing, woke up.

"Wot's that yer sye—niggers on our track?"

"Yes," Peter answered. "Oroko's men."

"Oroko—I've heard of him. Cannibal, ain't he?"

"He'll scoff the lot of us if he catches us."

"That's just what we're planning to avoid," said Bruce rather dryly. He thought Miley was scared. "What are we going to do, Kinny?" he asked of the big native.

"We go on," Kinny answered. "Them Oroko fella wait till him altogether dark before they come."

"That doesn't sound very helpful," said Bruce, but Kinny remained calm.

"You no worry marsta. We catch 'em one time."

"All right. You know best," said Bruce. "We'd best shift at once, hadn't we?"

"What use hurry? Belly belong me empty. We no can paddle unless full."

"He's got the rights of it, fellers," said Miley. "Grub afore work. That's my motto." Bruce and Peter were both watching the little Cockney pretty closely, but they had to admit that, if he was scared, fright did not spoil his appetite, and he ate his full share of the bully beef, biscuits and coffee that formed the midday meal. Also he insisted on time for a pipe of tobacco before starting again.

"Ain't no use killing of yourself the first day out," he told the boys. "It only means as you can't sleep, and then you ain't fit fer the next day's job." They took their full hour's rest and then started up river again. The boys noticed that Kinny kept in mid-stream and watched the banks closely, but neither he nor they saw a sign of natives. Bright-plumaged birds and even more brilliant butterflies were the only living things visible along the edges of the broad brown stream that came sweeping down from the distant mountains.

As the sun began to sink Kinny kept a keen lookout for a camping place and finally picked upon a place where a little stream came down into the river through a steep sided ravine. Bruce frowned.

"Don't think much of this, Kinny. If the niggers have followed us we'll be easy victims down at the bottom of this place."

"Orait (all right) Marsta. You no worry," replied the tall native gravely. "We finish them fella altogether."

"I hope we shall," said Bruce, but he looked very doubtful. A fire was lighted, and they proceeded to cook a good supper.

"What about them niggers?" asked Miley of Bruce. "You reckon they follered us?"

"That's what Kinabula thinks," Bruce answered. Miley looked round.

"Then this ain't much of a place to sleep in. They could rush us mighty easy."

"Just what I was thinking, Bruce answered, but Kinny knows what he's about."

"He's a wise bird," agreed Miley, "but me, I ain't going to sleep here, or likely I'll never wake up." Kinny heard.

"You rait," he said. "We no sleep here. We go back up there." He pointed up the gorge. "But we wait till altogether dark before we go. Now you help me, please get wood." There was plenty of timber handy, and under his direction they chopped four logs each about six feet long and laid these close to the fire which had got rather low. Kinabula turned to the others.

"You please go up there," he said pointing up the gorge. "Take guns and sleep-bags. You hide under him big tree and be altogether quiet. I come soon."

"All right," said Bruce. And as they walked away he added: "I wish I knew what the old beggar was after."

The tree which Kinny had pointed out was a banyan which grew on the top of the bank close above the camping place. The banyan has an odd way of dropping suckers to the ground, which take root and so make a thick jungle of stems. It was a hiding-place where a hundred men could easily have been concealed.

"He's making up the fire now," whispered Miley. "Looks like he wanted them niggers to find us."

"He's got some scheme in his woolly head." Peter answered. "Ah, here he comes." Kinabula came up the slope, dragging a thin wire behind him and joined the others. Below, the fire burned with a dull red glow which would last a long time.

"All fixed, Kinny?" asked Peter.

"Him fixed orait altogether. You see them logs?"

"Logs! They look just like people." Kinabula chuckled low in his throat.

"That what I want 'em look like, Marsta. I tink them fool Oroko men." Peter, too, laughed softly.

"I begin to see. A kind of booby trap."

"I no savvy booby trap, but it trap orait," said Kinny.

"I hope it will spring soon," Peter said. "These mosquitoes are pretty bad."

"Lumme, they're biting chunks out o' me," prowled Miley. "There's one on 'em trying to pull my right ear off." He slapped it as he spoke, but Peter said "Hush!" and after that there was silence. No—not silence for the bull frogs croaked, and smaller frogs bleated like lost lambs, and all sorts of queer insects made noises like rattles while night-moving creatures rustled in the brush. An hour passed—two hours. Nothing happened.

"Perhaps we got ahead of them," Peter whispered, but the big native pinched his arm.

"They come now," he answered. Peter never heard them come, yet suddenly the glade was full of savages. They came from the river and in the starlight moved softly as ghosts. Bent double they crept towards the fire, the dull light from which showed their great crops of hair bleached with lime and made their eyes glow red like those of wild beasts. Peter shuddered as he watched, and instinctively began to raise his rifle to his shoulder.

A score of spearheads flashed in the firelight sinewy black arms drew back and as the spears flew in a shower Peter shuddered again, for in every one of those logs which might have been their bodies three or four keen-bladed weapons quivered.

But the sound told the savages that something was wrong. Angry cries broke from them as they ran forward and bent over the logs which Kinabula had dressed up to represent human figures.

"Lumme but they're mad as hornets," muttered Miley. "Sye, but there's going to be all kinds o' trouble when they starts looking fer us."

"There be plenty trouble orait," observed Kinny as he reached for the cord. There followed a roar which sounded as loud as thunder and the fire rose up in a fountain of blazing logs and crimson sparks which made everything for a hundred yards round as bright as day. The roar was followed by the most fearful howls and yells as Oroko's men, scorched, scared and half-blinded, ran madly for their canoes.

"Dynamite," said Miley. "Well, I'll be jiggered."

"Better you be jiggered than kai-kaied," remarked Kinabula, and Miley smote him between the shoulder blades exclaiming:

"You're sure right, old son."

"Now take some sleep," said Kinabula calmly as he rose to his feet. "I no think them debbil-debbils come back this night." He went calmly back to the camping place, coiling the wire behind him as he walked, then he gathered up some burning embers and lit a fresh fire after which he wrapped himself in his blanket and lay calmly down to sleep. Peter looked at the crater which the dynamite had blown in the ground. He picked up a spear which one of their attackers had dropped.

"We shan't come to much harm as long as Kinny's on the job," he said.

"We're safe from Oroko's crowd anyhow," agreed Bruce.

"There's worse than them up in the hills," remarked the Cockney. "And that's as true as my name's Sam Miley."

NEXT morning dawned bright and clear and the only sign of the attack was the spears Oroko's men had left behind them. The party made an early start and after an hour's paddling saw ahead of them a huge crag, the dome-like top of which looked as if it had been split by an axe in the hands of a giant. This was Split Rock.

It did indeed split the river in two or rather it stood between the junction of the two streams that made the river. That to the right was small and swift but the left hand tributary was deep and not too rapid for paddling. They turned up it and kept on steadily for two hours when they began to hear a low droning sound which seemed to come from a great distance.

"That must be the rapid," said Bruce. "What did Mr. Dane call it—soda water, wasn't it?"

"Sounds more like Niagara," said Peter doubtfully, and as they travelled onwards the sound grew steadily till the whole air was full of the pulsing roar. The canoe rounded a bend, shot into a great pool and there in front were the rapids, a huge slide of white water quite straight and about a quarter of a mile long. Miley's eyes widened as he stared at the roaring eddies from which puffs of white foam rose and fell. "I reckon if we ever gets up there Oroko's men ain't a-going to follow us," he remarked dryly.

"How do we tackle it?" Peter asked.

"We gotter portage," Miley told him. "Take everything out of the canoe and carry it up the bank, then trail the canoe up at the end of a rope."

"All right then. Let's start," said Peter. But Kinny would not agree to this.

"Eat first—then pull strong," he said. So they landed and got out a tin of what Kinny called "bull-ma-cow" otherwise bully beef, and made a meal. That finished, everything was taken out of the canoe and made into loads; the canoe itself was pulled up and carefully hidden and they started.

It is not much fun to carry half a hundredweight of stuff up a steep hill in tropical heat, but when you have to carry it through virgin forest and over ground covered with boulders and seamed with deep cracks and crevices, the business becomes real slavery. Over and over again they had to stop and lay down their loads while Kinny used his axe to open a path. It took them more an hour to cover that quarter of a mile and they were all pretty nearly played out when at last they reached the top. Peter was limping. A thorn had run into his foot. Kinny himself pulled it out and Bruce poured some iodine into the wound. Wounds of this sort have a nasty way of getting poisoned in the sweltering heat of New Guinea.

Peter vowed he was all right but Bruce ordered him to stay where he was and watch the goods while the rest went back for the canoe. Bruce did not often put his foot down, but when he did Peter took it as said. Anyhow someone had to stay with the stuff so he sat on a log and watched the huge and gorgeous butterflies fluttering over the edges of the river.

Time passed and he was beginning to expect the others back when something moved in the bushes near-by and suddenly he caught sight of a fine black pig rooting near the edge of a little glade.

Pig-pork! The very thought made Peter's mouth water. He and all of them were sick and tired of tinned beef, and he thought what a triumph it would be if he could kill the pig and have it ready when the others returned. Very softly he picked up his gun which was loaded with buck shot and began to crawl through the bushes. His foot was a bit sore but not enough to prevent his walking.

The pig had moved but he could still glimpse its black, bristly back among the leaves. Yet he dared not shoot until he could get a better sight of it. Yard by yard he crept silently onwards but the pig, too, was moving and do what he would he could not get a clear shot. It was going straight back from the river and presently Peter found himself in a second and larger glade, a beautiful spot surrounded by thick tanamu trees and where the ground was thick with lovely flowers over which huge black and gold swallowtail butterflies hovered.

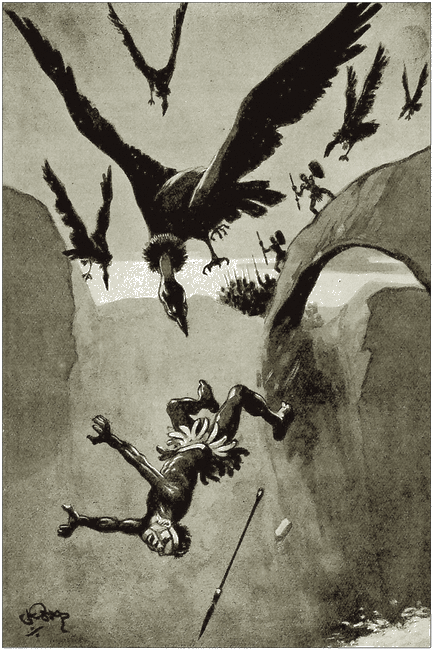

The pig was rooting under a tree at the opposite side of the glade. It was rather a long shot, but Peter was so afraid that the creature would disappear into the far bushes that he decided to risk it. He was in the act of raising his gun when he caught a movement among the trees beyond the glade, something swished through the air and the pig, transfixed by a spear, rolled over, squealed once and died. Peter had just time to drop as a tall, sinewy savage leaped out of the shadows upon the pig and uttering a grunt of satisfaction began to drag the spear out of the dead beast.

Then something else happened. Out of the tree above dropped an object like a thick rope that gleamed in the sunlight with prismatic colours. It was an immense snake and its great head with mouth wide open and three-inch fangs shining white, confronted the black man. Without his spear, he seemed helpless, yet he was not for he had a second weapon, a heavy club curved like a boomerang, and made of hard black iron wood. With great pluck he stood his ground and struck at the python with this weapon.

But the snake was quicker than he—so quick that even Peter, watching breathlessly, could hardly catch the movement. In a flash a coil of the huge reptile was round the man's body and he screamed as it tightened.

That scream roused Peter. He forgot that this man was a black and probably very dangerous cannibal; all he saw or thought of was that here was a fellow-being in desperate danger, and he rushed to the rescue. Placing the muzzle of his gun close against the body of the snake at a point just above the head of the native, he pulled the trigger.

The buckshot tore the great brute's body almost in two, shattering its spine. The fore part fell away from the man, and the whole of the monster dropped to the earth and lay writhing, thrashing fearfully among the long grass. Peter fired again and blew the brute's hideous head to pieces, then turned his attention to the native who lay flat on the ground. He had had a fearful squeeze and for a moment Peter thought he was done for. But his heart still beat and presently he opened his eyes and stared vaguely up into Peter's face. He gasped out some words which Peter, of course, could not understand, and tried to struggle up, but collapsed again, and lay panting. The fact was that the wind had been squeezed out of his lungs so that he could hardly breathe.

Peter did not know what to do, but just then he heard a shout, and here came Kinny running into the glade. His quick eyes took in the pig, the python and the man in a moment. Then he looked round swiftly to see if there was anyone else in sight.

"I was trying to shoot the pig," Peter explained quickly. "This fellow got ahead of me, then the python dropped out of the tree, and tackled the native and I shot him." Kinny nodded.

"Plenty good pig," he observed.

"Yes, but the man. Is he one of Oroko's crowd?" Kinny shook his head.

"Him Purari fella, I think." He spoke to the native who was slowly recovering and the latter, apparently relieved at seeing someone of his own colour, answered. Kinny looked up at Peter.

"Him name Mambare, his Purari man. He say he pretty pleased you kill dem snake." Peter laughed.

"He ought to be. He'd be mincemeat if I hadn't, and what about the pig Kinny?"

"Him say you take pig, but him help eat it." Peter chuckled again.

"That sounds all right. Then he'd better come back to camp with us."

"He help carry pig," agreed Kinny as he drew a big knife and started expertly butchering the animal. This done he cut it up, took half and Mambare the other half, and they went back to the head of the rapid where they found that Bruce and Miley had reloaded the canoe. Miley was delighted at the sight of the pig.

"Roast pork and crackling!" he grinned. "Ain't got no apple sauce, but I reckon we'll make do with guavas. I perposes a vote o' thanks to Mister Peter Carr."

"And I second it," laughed Bruce. "But what are we going to do with the black gentleman?"

"Him say he come along one piece," said Kinabula. "Him know river pretty good."

"And he looks like he can paddle," added Miley. "Boys, we're sure doing fine." They got aboard and paddled away. Tired as they were, they could not afford to waste the few hours before dark. Mambare wielded a good paddle and he certainly knew the river. Twice he saved them from running on rocks, and when dusk came he found them a good camping ground where they lit a big fire and roasted a great joint of pork. Large as it was, the whole thing was finished, and after the rest had rolled in their blankets Mambare was left still gnawing the bones.

NEXT morning Kinny had another talk with Mambare and the boys noticed a serious expression on the face of their black friend.

"What's up, Kinny?" asked Peter.

"Him say 'nother boat come up river," answered Kinny.

"Oroko's men?" asked Peter quickly.

"Him no Oroko; him white man."

"A white man! Who can that be?" asked Bruce, puzzled.

"I not know for sure, but I tink him Suarez."

"But Suarez had no money. He'd lost everything in the wreck," Bruce objected.

"Anyhow he was buying stuff at the store," put in Peter. "Kinny saw him."

"Yes I remember," said Bruce, "but what is he doing up here?"

"Following us," replied Peter sharply. "Bruce, don't you remember how that board creaked outside our room?"

"But he was asleep—snoring?"

"All camouflage, I'll bet. I don't believe he was any more asleep that I am. He listened, and he's after us to find out where the gold came from." Bruce whistled softly.

"I'm beginning to believe you've got the right end of the stick, Peter. But what a mess!"

"Don't worry," said Peter. "Likely as not Oroko will scupper him or scare him back. And in any case there are the rapids between him and us. But what's more likely than anything is that the whole business is a yarn. How can this fellow Mambare know anything about it?" Kinny, who had been listening, cut in.

"Him know all right. Him listen tom-tom." Bruce nodded. He and Peter had been long enough in New Guinea to know the way in which news travels just as it does in Africa and South America by means of native drums. There seemed no doubt that someone was following them, and probably it was Suarez.

"Then it's up to us to beat him to it," Bruce said. "And with Mambare to guide us we ought to do it. Will that nigger come with us up to the Gorge?" Kinny shook his head.

"Him no come hills; him scared."

"What of?"

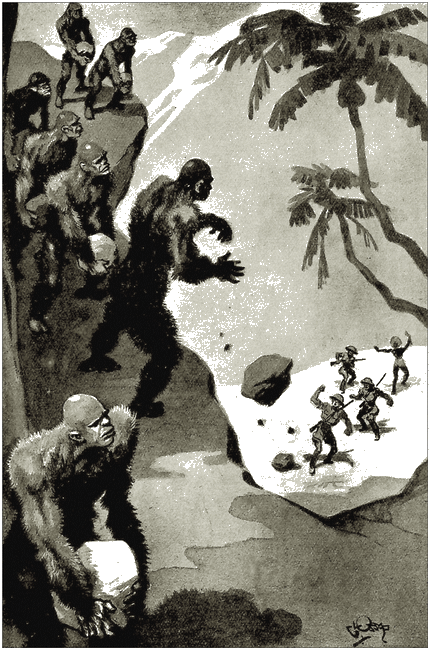

"Him say big fella hairy men live in hills."

"Hairy men?" repeated Peter. "I never heard of them, have you, Kinny?" Kinny looked uncomfortable.

"I think him talk 'em true. I hear 'em altogether big fella live in trees."

"Sounds like apes," said Peter, "but there are none in New Guinea."

"Just a yarn," replied Bruce. "And anyhow it's not apes that are worrying me, but gold thieves."

"We'll beat him to the hills," vowed Peter as he glanced towards the great rampart of mountains which towered against the northern sky.

Another hard day's paddling, and now the river was growing shallower and more swift, but there was still plenty of water. There were more people, too, for they heard drums constantly. It was not altogether pleasant to know that news of their coming was spreading inland to the very foot of the mountains. Late in the afternoon they found themselves opposite a native village which was built close to the bank of the stream. Forty or fifty formidable looking savages stood on the shore, all fully armed, gazing at the white strangers, and Mambare seemed distinctly uneasy. Kinabula whispered to have their guns ready in case of trouble, for that these men were head-hunters. Suddenly Miley spoke.

"What about giving 'em a bit o' music?" he said, and with that pulled out a case containing a mouth organ and set it to his lips.

The strains of "Dixie" rang out through the hot, still air. Rich and full and clear—it was hard to believe that they could come from such a shabby-looking little instrument. The big black men on the bank relaxed. You could see the astonishment on their ugly faces. Even the two who were paddling the canoe checked to listen.

The tune changed. It was "Marching through Georgia." So he sang the chorus "from Atlanta to the Sea." The chorus pealed out magnificently. The natives began to stamp in time to the music.

The little man finished.

"Go on," whispered Bruce.

"I tink we go on," said Kinny dipping his paddle again. Once more Miley struck up. He played "Home Sweet Home," and so sweetly and softly that Peter actually felt the tears coming into his eyes. By the time Miley had finished the canoe was safe around the next bend. Bruce turned to Miley.

"My word, you can play," he exclaimed with heartfelt admiration. "Where did you learn?"

"Taught meself when I were sheep herdin' in New South Wales," replied Miley as he wiped his instrument with a very dirty handkerchief and carefully put it away.

"It's a great gift," said Bruce. "I think you saved us from those natives. I'm glad you came with us." Miley grinned.

"You been a long time making up your mind," he said, and this was so true that Bruce got rather red.

They saw no more villages during the next two days. On the third morning after passing the rapids they were quite close to the mountains which rose like a wall across their path, appallingly steep and massive. They went up, precipice after precipice, in gigantic steps until the summits were lost in cloud.

"Getting near now," said Peter eagerly.

"But all the worst ter come," replied Miley, squinting up at the heights. "Ain't it a pity we can't turn this here canoe into a airyplane? It'ud save us a lot o' shoe leather." For the last hour a roar like that of the rapids, only deeper and louder, had been in their ears. Now they came suddenly upon a terrific cataract where the whole body of the river plunged over a five hundred foot wall of rock into a huge black pool.