RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Secret of the Baltic,"

Collins & Co., London, 1920

Title Page, "The Secret of the Baltic"

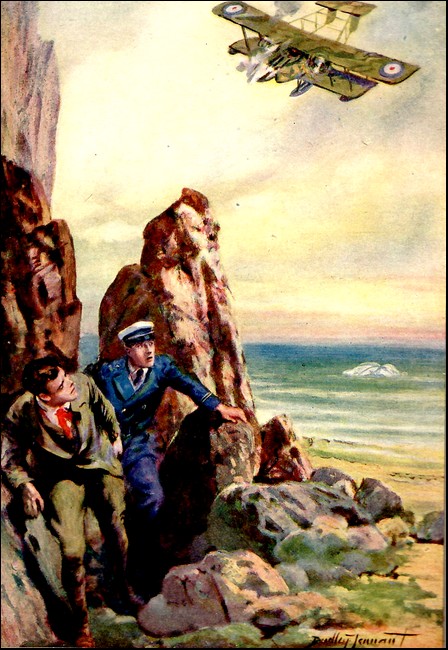

Frontispiece: "Close call!' gasped Anson.

'GOOD place for the trial, don't you think, Guy?'

Guy Hallam glanced down at the little gray North Sea waves that creamed and gurgled at the foot of the bare rocks; then his glance wandered across the bleak stretches of Yorkshire moorland running inland to the sky line.

He nodded.

'Couldn't be better, Wally. There's nothing to damage except a few gulls and crows, or perhaps—' He stopped suddenly and frowned slightly.

'Cratch, you mean?' said Wallace Ingram sharply. 'You are thinking of that beggar, Cratch, Guy?'

'I was,' confessed Guy. 'Fact is, I've been thinking a whole lot about the swab.'

'Serve him right if he is here,' said Wallace, with a viciousness quite startling in such a cheery, chubby-faced youngster. 'Serve him right if he is in the very centre of the pressure area. If he is, it's the last time he'll do any spying. That's one thing sure.'

Guy Hallam chuckled rather grimly. 'Yes, there won't be much left of him. And, like you, I couldn't find it in my heart to be sorry. Though we have no proof, it's a sure thing that Cratch is up to no good. He'd never have settled in a place like this if it hadn't been to spy on your father. Well, he'll have to take his chance. I don't see the flag up yet, Wally.'

'No, but dad won't be long, now. Shall we signal him?'

'There's no hurry. We may just as well wait until he is ready. I don't suppose he thinks we are here yet.'

'He can't get it into his head that you can plug along as fast as you do, Guy,' said Wallace, with a laugh. 'For a chap with a game leg you're a holy wonder. Why, it takes me all I know to keep up with you.'

Guy did not smile. His lameness, caused by an accident in a fire at school when he had risked his life to save another boy, was a terribly sore point with him. Although at eighteen he was taller, stronger, deeper in the chest and broader in the shoulders than most grown men, yet that damaged leg and the slight limp resulting from it had cut him off from the chance of wearing His Majesty's uniform. That was why he had turned all his thoughts and brains to chemistry and was now helping Wallace's father to perfect his inventions—inventions which, if properly used, would, so Mr Ingram hoped, do more to smash Germany than a dozen army corps or a fleet of battleships.

Young Wallace saw that he had put his foot in it, and very sensibly changed the subject.

'I do hope the War Office will take up dad's ideas,' he said.

Guy shook his head. 'It's going to be a tough job,' he answered. 'An unknown man always has the hardest kind of work to get any one big to take interest in a new invention. And neonite is so amazingly new and startling that no one would ever believe what it can do unless they saw it in action.'

'And the gun is just as wonderful,' said Wallace. 'Dad says that, if he had the money, he could make one that would shoot from Paris to Cologne.'

'And so he could,' declared Guy, 'or to Berlin either. It's only a question of sufficient power. Given the power, there is no limit. You could copy Jules Verne and shoot a projectile from the earth to the moon.'

'I suppose you could,' agreed Wallace. He turned and glanced towards the low, gray-walled, slate-roofed house that stood against the hill-side a mile away across the bay.

'Hallo!' he exclaimed. 'There's the flag. Dad's ready. Shall I signal, Guy?'

'Yes. No. Wait a jiffy. What the mischief is that?'

He pointed upwards as he spoke, and Wallace, looking up into the sky, saw an object floating at an enormous height above them. It was long and thin, and showed a delicate silver-gray against the pale blue summer sky. It was still over the sea, but was moving towards them at a brisk pace. Clearly a strong easterly current of air was setting up above, though below the light breeze was northerly.

'It's a balloon,' exclaimed Wallace. 'A sausage.'

'That's what I thought,' Guy answered. 'One of those observation balloons they use on the Front. She must have broken loose. But how on earth she has come right up here so far north is a puzzle to me.'

'It is a bit startling,' replied Wallace, still staring upwards. For the moment both of them had clean forgotten the trial of the neonite. 'I wonder if there's any one in her.'

'Hardly likely,' said Guy. 'Observers have parachutes, you know. Then if anything goes wrong, they can jump overboard and land.'

There was silence for a few moments, while the balloon came steadily nearer. As she approached she grew larger.

'She's coming lower, Guy,' said Wallace. 'That looks as if there was some one in her, letting out the gas.'

'You're right,' replied Guy. 'You're right, Wally. There is some one in the car. I can see him moving.'

'What's he doing?' exclaimed Wallace. 'What on earth is he about? Look! Look!' he continued, in a tone of horror. 'He's throwing himself out.'

'It's all right,' Guy answered. 'He's got a parachute.'

'It hasn't opened. He's dropping,' gasped the younger of the two. 'Guy, it's ghastly! He'll be smashed to pulp.'

'It's all right, I tell you, Wally. There, it's opening now. See, like an umbrella. He knows what he's about.'

Wallace drew a long breath of relief. After dropping like a plummet for several hundred feet the parachute had at last opened, and now the man from the balloon was dropping quite slowly, swaying slightly from one side to the other as he came. The balloon, meantime, relieved of his weight, had soared upwards again until it was a mere speck in the sky.

The boys hardly noticed it. Their eyes were glued upon the parachute. It was now beneath the easterly current, and in the lower drift of air.

'I say, Guy,' said Wallace anxiously. 'I don't believe he'll ever reach the land. He'll drop into the sea.'

'Just what I was afraid of,' answered Guy. 'But don't worry, we'll have him out.'

As he spoke he was over the edge of the bluff, and clambering down towards the sea.

Wallace was following, but Guy stopped him.

'No, stay where you are,' he called. 'And signal to your father to hold up the explosion till we give the word.'

Guy might be lame, but precious few sound men could have beaten him in a race down that bluff. Though not very high, it was steep, and the rocks were sharp and ugly. Fortunately the tide was low, and there was a narrow strip of shingle lying bare at the foot of the cliff. Reaching this, Guy looked up.

There was the parachute not a hundred feet up, fluttering downwards quite slowly and gently. And the man who sat in the loop wore the uniform of a British naval officer.

'Thank goodness, he won't fall very far out,' said Guy, measuring the distance with his eyes. Then, flinging off coat and waistcoat, he plunged into the water.

He timed it so well that, as the dangling sailor touched the water, he was exactly beneath. The sailor had already got clear of the loop and was hanging on to the rope by his hands.

Looking up, Guy caught a glimpse of a face brown almost as old saddle leather, but pinched with cold and perhaps hunger, gray eyes reddened with wind and fatigue, and a chin of the type which is generally described as being 'like the toe of a boot.'

'I say, this is awfully good of you,' said the stranger hoarsely, as he dropped almost into Guy's arms. 'But I can swim all right.'

'Dare say you can,' responded Guy dryly. 'But not in Galleon Gap. Currents here are no joke, I can tell you. Let yourself float. I'll tow you in. Then I'll get the parachute.'

'Blow the parachute,' said the other. 'Let it go. It's only a Hun one anyhow. Jove, I'm not sorry you came out! I don't mind owning I'm pretty near done.'

Guy did not answer. He had his work cut out. The tide, still ebbing, sucked him treacherously away from the shore. He was forced to fight with all his strength and cunning, and as for the stranger, he would not have had a dog's chance alone.

'My only aunt, but you're some swimmer!' gasped the other, as Guy found his feet and dragged him ashore. 'Ugh, isn't the water cold?'

'I've been up topside the last twelve hours and more,' he added apologetically. 'And not even a pea-jacket to keep the chill out.'

'Twelve hours! I should jolly well think you had had enough of it,' answered Guy. 'But you'll be all right now. Do you feel up to climbing the rocks, or shall we go round by the path?'

'The path, I think, if you don't mind,' said the other, trying to smile, but making rather a poor attempt at it. Guy saw he could hardly stand, and made no bones about getting an arm round him and helping him along.

'Chuck that!' said the other quickly. 'Hang it all, man, you can't help me. You've hurt yourself. You are limping.'

'I've been limping these four years,' replied Guy, rather grimly. 'There's nothing to make a song about.'

'I—I'm sorry,' said the other hastily. 'I say, I haven't introduced myself. I'm Anson—Dick Anson.'

'Guy Hallam, I'm called,' replied Guy, more genially. 'And I'm living at that house across the bay. It's just as well you dropped where you did. There isn't another house for miles except—'

'Hallo!' he broke off. 'What's young Wallace kicking up such a shindy about?'

'That youngster at the top of the cliff,' said Anson. 'There's something up. What's he pointing at?'

He turned as he spoke and looked upwards, in the direction in which Wallace Ingram was pointing.

'A plane!' he exclaimed, and his voice was suddenly sharp. 'Look out, Hallam! They're after me, I do believe. We'd better take cover.'

'What's the matter?' asked Guy, in surprise. 'She's one of ours. Look at her marks.'

'Then what is she doing here?' demanded Anson. Guy was surprised to see how anxious—almost scared—the young sailor seemed to be. He was still more amazed to see him break away and fling himself down behind a rock.

'Get in here,' cried Anson sharply. 'Lie down beside me. Quick! I tell you she's a Hun.'

Guy stood staring up at the plane. 'She can't be,' he remonstrated. 'Look at her red white and blue circles.'

Anson sprang up again, caught Guy by the arm, and with a strength Guy did not suspect he possessed, dragged him down behind the rock.

'Camouflage, I tell you,' he said roughly. 'She's a Hun, and she's after me. See! She's coming straight down.'

She certainly was. Her pilot had cut out the engine, and in perfect silence she was sweeping downwards in a long steep glide. She was a very large seaplane. Her double planes were quite a hundred feet from tip to tip, and her fuselage appeared to be armoured. She had two tractors, and between their spinning blades Guy caught sight of the black muzzle of a machine gun. She bore a sinister resemblance to a gigantic bird of prey swooping down out of the blue.

'After you!' echoed Guy. Then, before he could say anything more, the silence was split by the sharp rattle of the machine gun, and a storm of bullets lashed the cliff side all around them. Splinters of rock flew in every direction, and the dust was blinding.

The burst was over in a matter of seconds, but it lasted long enough for Guy to be certain that, if Anson had not forced him to take cover, he would have been riddled like a sieve. Next instant the twin engines roared again, and the plane, circling, zoomed upwards, preparatory to a second dive and fire burst. Guy raised himself a little and stared up at her.

'Get down!' shouted Anson in Guy's ear. 'Lie low, I tell you. Hang it all, man, don't you realise by this time that I know what I'm talking about? I tell you they'd sell their souls to get me. I'm the only man in England who knows their big secret.'

Guy only half heard.

'But Wallace!' he cried, in desperate anxiety. 'Heavens, man, the brutes will get Wallace!'

Anson caught Guy by the arm and held him tightly. 'You can't help him,' he answered harshly. They'd have you long before you could get to the top. Keep down, I tell you. The boy will be all right. Ten to one he's taken cover like ourselves.'

Half frantic as he was on Wallace's account, Guy had to own that Anson was right. The big plane was already round again.

Quite clearly, her crew knew exactly where Anson was hiding, and were manoeuvring to get their gun to bear on him.

But this was difficult. The rock behind which he and Guy were sheltering was part of the cliff itself, a sort of spur sticking out close by the path. They two were in a narrowish crack or crevice between it and the steep slope behind.

The worst of it was that the rock itself was small, so that there was barely room for the two to crouch side by side. It was distinctly on the cards that their enemies might get them by a quick burst fired sideways as they came down on the left handed glide.

Anson saw this before Guy.

'Watch out!' he cried sharply. 'The moment you hear their engine stop follow me round the rock. Remember your life depends on your quickness.'

The words were hardly out of his mouth before the roar of the twin engines ceased abruptly. Instantly Anson made a jump for the path side of the rock, and Guy was after him like a rabbit.

Only just in time. Next second a fresh storm of lead scourged the rock and the cliff face all round. A splinter stung Guy's leg through his stocking, another cut Anson's ear, making it bleed. Then the plane was down, nearly touching the little gray waves of the Bay.

'Close call!' gasped Anson. 'Now look out. They'll try the other side.'

The big biplane spun like a live thing, banking so steeply that her wings for an instant were almost at right angles with the sea. Guy got a glimpse of her crew. They were two in number, the pilot and the man at the gun. Fur-coated, hooded, and goggled as they were, they were both unmistakably German.

Only a glimpse. There was no time for more, for back she came, zooming up so close to the cliff face that the roar of her engines nearly deafened Guy.

Anson leaped back to his old position, Guy followed, and for a third time they were pelted with a deadly hail.

'Mucked it again!' cried Guy, as the plane went hurtling up out of sight over the rim of the cliff.

'But it can't last, Hallam,' answered Anson, between set teeth. 'It can't last. They're bound to have us sooner or later. If they can't get us this way, they'll land and come after us. I've stumbled on Germany's biggest secret. I'm the only Englishman who knows it, and they know that as well as I do. Cost what it may, they have to get me, and in a case like this their own lives count for nothing.'

The roar of the engines ceased, and he broke off short.

'Look out! They're coming again. And I don't know which way this time.'

Guy did not know either. What he did know was that, if he and Anson made any mistake and jumped to the wrong side of the rock, their lives would pay the penalty.

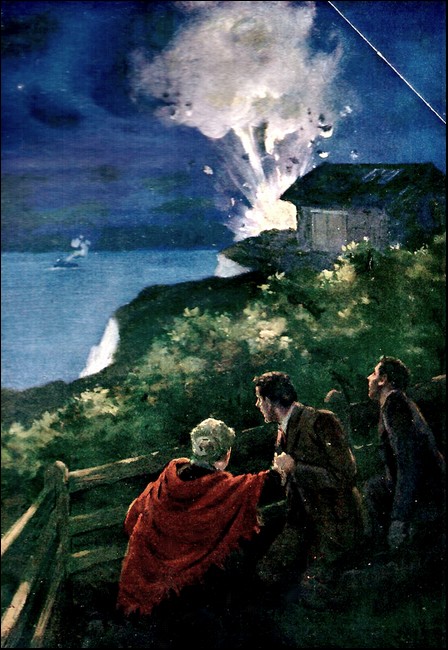

Then, before he could speak or even think again, there came a shock which made the very cliff tremble. The solid rock seemed to lift and fall again. On the heels of this followed a short, dull roar of sound—dull, yet with a curiously stunning effect.

Guy found himself flat on his back. He was half deaf and curiously confused. All he was conscious of was a sudden blast of wind that came sweeping off the sea with such force that sand and small pebbles flew inwards in showers, while the water itself was veined and streaked with foam.

He was roused by Anson's voice.

'W—what was it?' gasped the sailor. 'An—an earthquake?'

Suddenly Guy understood. He scrambled to his feet.

'The neonite!' he shouted. 'Good for Wally! He's given the signal and set it off.'

'Keep down, you idiot!' roared Anson. 'The plane!'

'Plane!' retorted Guy. 'Plane be blowed! Do you think that any plane that ever flew could stick up in this sort of thing? I'll lay anything you like she's flat as a pancake. Come and see.'

IN spite of his lameness, Guy beat Anson to the top of the cliff path. The first thing he saw was Wallace flat on his back on the turf.

'Wally!' he cried in dismay, as he ran towards him. 'Are you hurt? Did they hit you?'

But Wallace was already scrambling to his feet.

'Hit me? The Huns, you mean? Not they. I don't believe the beggars ever saw me. But you—you and the other chap. Do you mean to say they never touched you?'

'The rock saved us, Wally. But they'd have got us next time if it hadn't been for the neonite. I suppose you touched it off?'

'You bet, I did. Gosh, didn't it make things hum? It was the wind of it bowled me over.

'But where's the plane?' he went on, staring all round.

'Can't see her,' said Anson, coming up. 'Can't see a sign of her, so she's bound to be down. That whirlwind would have crashed any plane that ever flew.'

'Whirlwind!' cried Wally, whose eyes were sparkling with excitement. 'Whirlwind, you call it. That was dad's neonite. His new implosive.'

Anson stared. 'I don't know what the mischief you're talking about, youngster,' he answered. 'I never heard of an 'implosive.' But you can tell me later. What we've got to do now is to find that plane—and find her jolly quick. Because she's crashed, it don't follow that her crew are killed. And kindly remember they're armed and we are not.'

'Come on, then,' said Wallace eagerly. 'The chances are they are in one of those gullies. The gust came off the sea, so it must have carried them inland.'

He was running forward, but Anson caught him.

'Steady! Go slow!' he said sharply. 'Just bear in mind that they may start potting at us any moment. We must scatter, and take all the cover we can find.'

The cliff top was covered with boulders and clumps of gorse. There was plenty of cover, and even Wallace was enough impressed by Anson's earnestness not to expose himself unduly. Keeping about thirty yards apart, the three worked steadily back from the edge of the cliff.

Guy's heart was beating more quickly than usual as he crawled through the gorse and heather. Things had been happening so quickly he had hardly had time to think. Now all of a sudden it struck him that the whole business was like some crazy dream. A quarter of an hour earlier, he and Wallace had been peacefully waiting to give the signal to the house to explode the neonite. Now they and Anson were tracking real Huns through the familiar Yorkshire heather.

All of a sudden he found himself on the edge of a gully. It was a deep wash cut in the black peaty soil, that ran curving down towards the sea. It was about forty feet wide and perhaps ten deep. He pulled up, and keeping his body well under cover peered cautiously over.

His heart gave a great jump. A little way up, the gully was blocked by an amazing tangle of tattered yellow wings mixed with broken spars, wire rigging, and all sorts of wreckage.

Whipping out his handkerchief he held it up, and let it flutter in the breeze.

Next moment Anson was beside him, while Wallace came hurrying recklessly from behind.

'She's crashed all right,' said Anson rather grimly, as he stared at the mass of wreckage. 'Ten to one both the fellows are dead. Still, it's as well to be on the safe side. Follow me, but don't expose yourselves.'

Anson spoke as one accustomed to be obeyed, but Guy took no offence. He realised that the sailor knew exactly what he was about.

Presently Anson came to a stop behind a tall gorse bush which grew on the bank of the gully just above the wreck of the plane. For quite half a minute he lay perfectly still, watching the wreckage, while the others crouched close behind him, both more excited than they had ever been before in their lives.

At last he turned. 'Right O!' he said. 'They're either dead or stunned. Anyhow, there's no movement.' He turned to Wallace.

'Better stay where you are, youngster,' he continued kindly. 'A crash is always an ugly sight. It'll spoil your dinner and your dreams. You come on, Hallam.'

Anson slipped quietly over the edge of the gully and disappeared under one of the big upper planes, which lay like a roof across the rift in the ground. Guy, keen as mustard, followed close.

The plane had pancaked—that is, gone down flat, and in under the shadow of the wing was the fuselage. The wheels were wrenched off, the boat-shaped body itself was twisted out of shape, and in among the bent rods and torn fragments of the under planes Guy glimpsed two figures. One who lay clear was on his face in the bottom of the dyke. His body was doubled up, one leg twisted beneath him in an unnatural position. The other was still in the wrecked fuselage. He was leaning forward, with his head resting on his outstretched arms.

Anson turned to Guy.

'Keep a stiff lip, Hallam,' he said warningly. 'This isn't going to be pretty.'

Guy's answer was to fling out both arms and push Anson violently aside. At the same time he himself dropped. Next instant the vicious crack of an automatic sent echoes rattling along the gully, the bullet ripping through the air exactly where Anson's body had been a second earlier.

Guy saw a large stone exactly under his hands. Without the smallest hesitation he seized it, straightened himself and flung it, all with the same movement.

There was a thud, a yell of pain, and the pistol barked once more, but harmlessly. Guy's stone had caught the treacherous German clean in the centre of the chest, doubling him up and knocking the wind out of him.

Before the fellow could recover or fire again, Guy was on him and, catching him by the throat with both hands, forced him back, till his head was jammed hard against the farther edge of the fuselage.

'Steady! Don't kill him,' came Anson's voice in his ear. 'Yes, I know he deserves it, but he'll be more useful alive. All right, I've got his gun. Hang on to him while I tie his hands.'

With sailor-like smartness, Anson secured the German's wrists with his own handkerchief.

'Now he's harmless,' he said. 'I say, Hallam,' he added with a grin, 'he'd never take a prize in a beauty show, would he?'

Anson was right. The Hun, scowling balefully up at them, was satanically ugly. He was quite short, but had the chest and shoulders of a giant, while his arms were as long as those of the original Black Dwarf. His head was bald as a coot's, and the smooth skull was shaped like a dome. He had a great hooked nose, a gash of a mouth, and small, deep-set, pale blue eyes.

Yet in spite of it all, he was a Prussian. You had only to glance at him to see it. Haughtiness, intolerance, and downright cruelty were written large all over him.

Anson looked at the other man.

'Dead as mutton,' he pronounced. 'Now then, Hallam,' he went on briskly. 'Let's get this chap to your house and shut him up. We musn't run any chances. He's a jolly sight too valuable to lose.'

'Come out of it,' he said curtly to the German.

The German was furious.

'Beggarly Englishman!' he stormed. 'You dare to speak to me in such a way! I am an officer and of noble birth. I demand to be treated with due respect.'

'You may be the Lord High Panjandrum himself,' retorted Anson. 'All I know about you is that you're a treacherous hound. You'd best make up your mind at once that there are not going to be any first-class carriages or motor-cars for you. So just put your best foot forward and come along.'

'I am the Baron von Fromach,' foamed the other, but Anson cut him short by dragging him out of his seat. Guy took him by the other arm, and between them they lugged him up the bank and started him in the direction of the house.

Once they got him going he went steadily but sullenly ahead.

'Keep an eye on him, Hallam,' said Anson in Guy's ear. 'He comes from the Secret City, and it's worth anything you like to me if we can get him to own up. My story is so wild and woolly that I have my doubts as to whether any one is going to believe it unless I can get some backing.'

'The Secret City?' repeated Guy. 'What in the world is the Secret City?'

'The newest Hun dodge for smashing us, my son,' replied Anson gravely. 'I'll tell you all about it as soon as we reach the house. It'll be a big relief to get it off my chest. All the way across, as I was drifting in that infernal sausage, I was wondering what the mischief would happen if I was done in before I could get the news to England.'

'You've been there?' questioned Guy, eagerly.

Anson nodded. 'I've seen it,' he answered. 'But don't talk about it now. That beggar's ears are as keen as a hare's, and for all the sulky look of him, he's listening for all he's worth.

'Hallo!' he broke off. 'What's the youngster want?'

Wallace had slipped up alongside.

'I saw something move up on the hill there,' he said in a low voice.

Guy stared towards the top of the ridge.

'Can't see anything,' he answered. 'Are you sure, Wallace?'

'Dead certain. I caught a flash of something in the sun. It's my belief some one is watching us through glasses.'

'It's Cratch,' said Guy, frowning.

'Who is Cratch?' asked Anson.

'A fellow who lives in an old farmhouse near here. Pretends to be on a fishing holiday,' Guy answered. 'But Wallace and I are pretty certain he's a spy. We've spotted him watching us more than once. He's after Mr Ingram's neonite.'

'Is neonite this stuff you call the implosive?' asked Anson.

'Yes. It's the biggest thing yet. Well, you saw what it did. But I mustn't tell even you. Mr Ingram himself will do that.'

Anson nodded, and they trudged on in silence until they reached the house. Mr Ingram himself came to meet them. He was a man of fifty, with clean cut features and bright, luminous eyes. His hair was almost white, and his long delicate fingers were stained with chemicals.

'What's this? What has happened?' he asked quickly, as he stared first at the German, then at Anson.

It was Anson who answered.

'I am Sub-lieutenant Dick Anson, sir, late of H.M. Submarine Q2. This is my prisoner, a German named von Fromach. I will ask you first to find some secure lodging for him. After that I shall be glad to tell you my story.'

'Very good. Guy, we can put him in the old magazine. That will be safest.'

'The very place, dad!' exclaimed young Wallace eagerly. 'Here we are,' he continued, pointing to a small square stone building standing behind the slate-roofed laboratory.

Anson looked in. The place was stoutly built. It had no window, only a skylight, and the door was heavy and solid.

'Yes, he ought to be safe here,' he said.

Von Fromach apparently did not share Anson's opinion. He was furious.

'I demand to be housed in proper quarters,' he said haughtily. 'This place is not fit for a dog.'

'I should be sorry to compare a decent dog with you,' said Anson dryly, and catching his man by the shoulders shoved him forcibly inside the magazine and slammed the door on him. Mr Ingram locked it and, putting the key in his pocket, led the way to the house.

'Dinner is just ready, Mr Anson,' he said courteously. 'I dare say you won't be sorry for some food.'

Anson smiled rather wanly.

'You are right, sir,' he answered. 'When I tell you that the last meal I ate was aboard Q2 in the Baltic nearly two days ago, you can imagine whether I am hungry or not.'

'CERTAINLY I will tell you all about neonite,' said Mr Ingram. 'But not yet. We must have your story first. It is not mere curiosity on our part. As you have said yourself, you are the only Englishman who knows this great secret of Germany, and it seems to me that the sooner you share your knowledge with some responsible person, the better for our country.'

Young Anson nodded. After a change of clothes, a bath, a shave, and a good meal, he looked very different from the worn, red-eyed, haggard person who had arrived at Claston a little more than an hour earlier. He was once more the spruce, keen-faced naval officer.

'You're right, Mr Ingram,' he answered. 'And I don't mind telling you that I shall be precious glad to get the story off my chest. If that beauty, von Fromach, had managed to pip me just now, I firmly believe we should have lost the war.

'Sounds a bit boastful,' he continued, with a smile, 'but when you have heard my yarn I rather fancy you will be inclined to agree with me.'

He paused a moment.

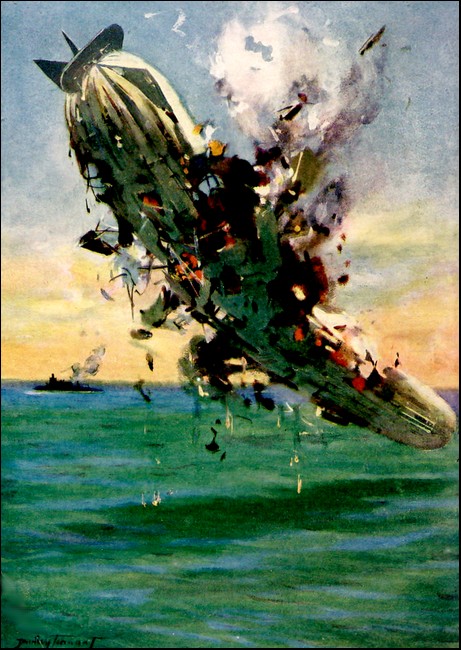

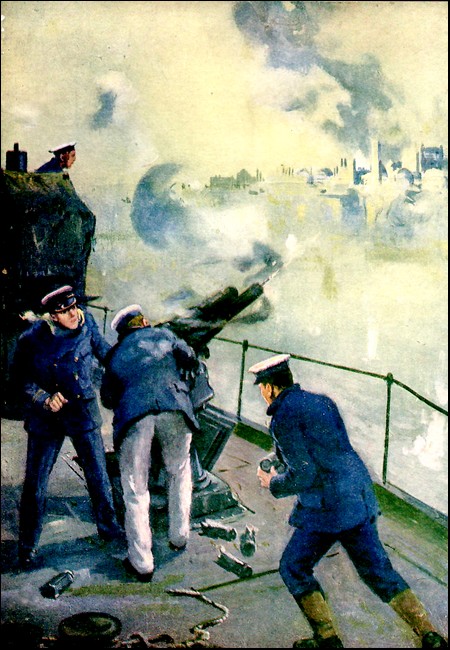

'Well, you know my name,' he said, 'and I think I told Hallam here that I'm a submarine man. I am, or was, second in command of one of our new class, Q2, and our job has been in the Baltic. I needn't bother you with the story of how we got in. It's enough to say that we succeeded where better men have failed, and that we had good luck all through.

'We strafed three big ships loaded with stuff from Scandinavia for Hun ports, and then as they were hot after us, we nipped up north a bit, in among those islands which lie between Sweden and Russia. They used to be Russian, but Fritz has bagged the best of them.

'Here we got the shock of our lives.

'One morning we found the temperature dropping in the most uncanny fashion. It wasn't the air only. It was the water as well. From a fine sunny morning as warm as an English May day, we ran, within a couple of hours, into a temperature that wasn't much above freezing point, and a dense fog.

'Harman—my skipper, you know—couldn't make head or tail of it.

'"Is this August or is it November?" he asked me.

'"It was August this morning," I told him. "Now we've either dropped three months in as many hours, or else we're running into ice. I've seen this sort of thing in the north Atlantic when there was a big berg floating down from the Arctic."

'"So have I," said Harman. "But there are no icebergs in the Baltic at any time. And the last of the floe ice melts in May."

'"I'll bet you there is ice, all the same," I declared. He got quite cross about it, and we were arguing pretty warmly when all of a sudden there was a crunch, and blessed if we hadn't run into a thin sheet of ice which seemed to cover the whole sea ahead.

'That finished the argument, but it only added to our perplexity. Mind you, it takes a lot of cold to freeze salt water, and even so far north as the Upper Baltic you don't get frost in August.

'Harman vowed he was going to investigate, so we backed out and began to coast around the edge of the ice. Soon we found that we were cruising in a circle, but the fog was still so thick that we had not the faintest idea what there was in the centre of the circle.

'We might never have known, only for a breeze that sprang up quite suddenly out of the east. It lifted the fog, and what should we see in the centre of the ice but a small island! It had low cliffs all around it, and from somewhere inside the rim of rocks smoke was rising.

'"What do you make of that, Anson?" asked Harman.

'"Some of Fritz's devilry," I said, for by this time I had my glasses bearing. "There's a factory chimney up there in the middle of the island."

'He wouldn't have it at first, but when he had taken a good look through my glasses he was forced to confess that I was right.

'The next thing was what to do about it. We simply couldn't leave without making a shot to find out what was up. We decided to hang about until night, then dive under the ice and see if we couldn't make a landing somewhere.

'There wasn't much risk of being spotted. You see the ice out there in the middle of a warmish sea kept a regular steady fog going, and it was only when a strong puff of wind came along that we could even get a glimpse of the island.

'So there we stayed, and mighty cold it was.'

Young Wallace Ingram suddenly cut in.

'But I say, Mr Anson, what made the ice? I suppose it was some dodge of the Germans.'

'You bet it was,' replied Anson. 'We realised that at once, and I ought to have told you so. Somehow they have got on to the secret of producing intense cold. It's an idea that scientific people have been after for years, and I believe the thing has been done on a small scale by an Italian chemist. You can see for yourself what a tremendous pull it would give them both at sea and on land.'

'That is only too plain,' said Mr Ingram gravely. 'They could close any strait or harbour at will, while on land they could harden muddy ground so as to move artillery over it, or—if they can control the Cold Ray—they could actually freeze our forces in their trenches, and then advance over them at their leisure.'

'They can control the Ray all right,' said Anson, with a grim tightening of his lips. 'Listen and I'll tell you.

'When night came we dived. We had spotted a little patch of open water close under the cliffs, and that is what we made for. As a matter of fact, it didn't matter much about reaching it, for the ice was nowhere more than six inches thick, so that we could have broken it without much trouble.

'Harman, of course, had to stay by the ship, so he sent me off with a man called Harington, who was our coxswain. A big hefty fellow, yet quick on his feet as a cat.

'We went ashore in the dinghy, and landed on a ledge at the foot of the cliffs. There was no one about. I suppose they thought that the fog was protection enough. Anyhow, we found no one to interfere with us.

'The next thing was to climb the cliffs. They were not high, but they were most infernally steep, and in that cold the climb was anything but a joke. If it hadn't been for John Harington I should never have managed it.

'To cut a long story short, we did get to the top all right in the long run, and the two of us crept over the rim of the cliffs like a pair of scouts coming out of a front line trench into No Man's Land.

'The reason we were so jolly careful was that the fog had lifted a bit, and we had spotted a couple of sausage balloons against the night sky overhead. I suppose they always let them up when the fog is not as thick as usual.

'The ground along the cliff top was rough and rocky, which was just as well for us, for I tell you we needed all the cover we could find. If it had been dark climbing up the cliffs, it was light enough once we reached the summit. The whole interior of the island was a blaze of light.'

Anson paused a moment. His three listeners sat absolutely silent, waiting eagerly for him to continue.

'I must explain a bit,' he went on. 'This island—it's called Rosel Island, I believe, is a most curious shape. It's almost circular, and though there are these low cliffs all around, the centre is a great hollow, a sort of shallow basin which looks as if it ought to be full of water, but isn't. This hollow is about a mile across, and in the centre is a town. It's more than a town; it's a regular city, quite hidden from the sea by its rim of rocks, but as complete a place as you can possibly imagine, and wonderfully laid out.

'So far as I could see, the whole of the centre was one great factory. The chimney which we had seen from the sea rose from an immense power plant which was part of this factory. All around were workmen's houses, very neatly built. We could spot a large house, which is probably the Governor's, a school, a church, and other public buildings. From the size of the place there must be four or five thousand people in it—perhaps more.

'Near the chimney is a tower, a huge structure of steel girders, but not quite so high as the chimney, and on top of this is a thing which looks rather like an enormous photographic camera. This, I fancy, is the apparatus they use for producing the Cold Ray.

'I don't know how long we lay there, staring at the scene below. I remember noticing the people moving about in the streets, and all dressed as though they were bound for an Arctic expedition, and I can recall, as plainly as if I heard it now, the steady beat of machinery and the hum of dynamos. I could see, too, that opposite us was a break in the island wall, with a narrow opening into a small but deep harbour. Deep it must have been, for the three or four ships that lay there against the quay were all large ones.

'We were both so absolutely wonder-struck with all we saw that neither of us said a word, and it was not until I found that my teeth were chattering with the cold that I broke the silence.

'Then I turned to Harington.

'"We shall freeze if we stay here," I told him. "We had better shove on and get a closer view."

'Harington agreed. I could tell by his voice that he was as thunderstruck as I was myself. So he and I crawled on, taking all the cover we could find as we went.

'We didn't get far. Fritz don't take any chances. Next thing we knew, we were up against a barbed wire fence—seven strands, and probably electrified. I don't know whether he put it up to keep his own people in or other folk out. Anyhow, since we had no gloves or pliers, it put the hat on any further progress on our part. There was nothing for it but to go back and report. In a way I was not sorry, for it was getting colder all the time. That camera machine seemed to have swung round in our direction, and I tell you the temperature wasn't far off zero.

'So we turned, and were working back again to the edge of the cliff when Harington, who was a bit to the left of me, suddenly pulled up short. He didn't say a word, but pointed.

'A little to his left was a hole in the rock, the mouth of a pit some six feet square, and out of this rose a wire. It was of fine steel no thicker than a piano wire, and it rose straight up till lost in the darkness overhead. I could only see it by the faint gleam of light reflected upon it.

'What sort of infernal device this might be I had not the foggiest notion, but of course I had to see, so I crept up and peeped over.

'I tell you, I pulled back as quickly as a scared rabbit. I was looking right down upon the back of a large Hun who was squatting at the bottom of the pit. He was wrapped in a big sheepskin coat, and was sitting alongside a sort of windlass from the drum of which ran the wire I have spoken of.'

Anson paused a moment again, and took a sip from his cup of coffee.

'What was it—a balloon?' broke in Guy Hallam.

'Exactly. As I suspected then, and made certain of the fact later, the whole island is surrounded by a barrage consisting of small balloons sent up to a great height, and held by steel wire of great tensile strength. This barrage is an improvement on our own 'Apron' scheme, and completely protects the island from aeroplane attacks.'

'It is quite evident that the Germans are taking every precaution to guard this Secret City of theirs,' said John Ingram, frowning.

'That's what struck me,' replied young Anson. 'It means that they think a lot of whatever they have there, whether it's the Cold Ray or something even more diabolical.'

'Did you scupper the Hun?' demanded Wallace Ingram.

'No,' said Anson. 'I should dearly have liked to, but I had no right to take risks. I signalled to Harington, and we left the fellow and made off.

'If climbing the cliffs was bad, getting down was worse, and we were jolly glad when we reached the beach in safety. By this time the cold was something awful, and my one idea was to get back aboard Q2 and warm up a bit.

'The dinghy lay where we had left it, but the bit of open water was gone. It was all ice—thick ice, too. Rowing was out of the question.

'There was nothing for it but to walk across the ice and try to find the submarine. It was a dark night, we could not see ten yards ahead, and we had no notion whether the ice would bear. That walk was an absolute nightmare.

'But there was worse to come. When we reached the spot where we had left Q2, she was gone. There was not a sign of her.'

Anson paused again.

'What had happened to her?' asked Wallace breathlessly.

'I don't know. Even now, I have not the faintest notion. We had heard nothing, seen nothing. And you can bet your life Harman would never have deserted us. He is not that sort. Whether the Huns had spotted her and used some infernal dodge to destroy her, I can't say. I can't see what they could have done. It's true they had increased the cold, and it's just possible that Harman was forced to submerge to save Q2 from being frozen in.

'At any rate, our ship was gone, and Harington and I were left there alone on the ice, stiff with cold, and in about as tight a fix as I, for one, ever want to be in.

'There was nothing for it but to get back to land. My first idea was to tow the dinghy out over the ice and launch her and get away. But, as Harington reminded me, the outer edge of the ice sheet which was beyond the main power of the Cold Ray would not bear us. The only alternative seemed to be to wait under the cliffs till morning. But that wouldn't work either. They'd only spot us from their observation balloons, and then it would be the nearest wall and a firing party. Fritz was not likely to let any one live who had stumbled on his big secret.

'I said as much to Harington, and it was my mention of the sausage that put an idea into my head. It struck me that they would hardly keep the old thing up all night, and that by this time they had probably hauled her down. Why shouldn't we see if we could surprise her, steal her, and get away in her?'

'Of course, it was a crazy notion, but we were absolutely up against it, and even if we failed we could finish up in style. We both had automatics.

'Harington, stout fellow, jumped at it, so once more we climbed those chilly cliffs, and went groping along the top in that bitter, freezing fog.'

'LUCKILY for me,' said Anson, 'I have a good bump of locality, and I had spotted exactly where the sausage was moored. The thing I was scared of was that she might be inside the barbed wire, but luck was good to us, and presently we spotted the outline of the big bag lying above a sort of rock emplacement, quite close to the edge of the cliff.

'Beneath was the petrol winding engine for letting her up or down.

'We knew, of course, that there would be at least one sentry with her, but we hoped not more than one. Since it was out of the question to use our pistols, I picked up a useful chunk of rock, and Harington did the same.

'Then we started.

'In our excitement we had forgotten for the moment all about the balloon barrage, and we had the narrowest sort of escape from blundering into one of the pits. Luckily for us, there was another shut-eye sentry in this place, and we got away without disturbing him. A few minutes later we were crouching side by side on the edge of the sausage emplacement.

'Fritz had done the job with his usual thoroughness. He had carved out a young quarry for the big balloon to lie in when the weather was stormy. You've seen the balloon itself, so you can judge how big the pit was. In the fog and the darkness we could not tell whether there was one man there or a dozen, and we had to make a circle of the whole place on hands and knees to find out.

'Suddenly Harington touched me on the arm and pointed. There was a little lean-to hut against the edge of the pit, and right beneath us. He didn't speak, but we both knew that this was where the guard must be sheltering.

'The worst of it was that we could not see inside, or tell how many men there were. There was nothing for it but to go down into the pit and chance it.

'I don't mind telling you that my heart was in my mouth as I slid over. Harington followed, and, big as he was, a mouse could not have made less noise.

'Then I peered round the corner.

'There were two men there—big, hulking chaps. One was dozing, but the other wide awake as you please. He looked a giant in his great sheepskin coat.

'It was no use waiting. I laid my stone down, pulled my pistol, and in two steps had the muzzle jammed against the side of his head.

'His mouth opened like a fish when it is pulled out of water, and his eyes goggled. Before he could recover himself or shout, or even move, Harington was behind him and had him by the throat. I saw he was safe, and so dropped instantly on the fellow who was asleep.

'Before he was awake I had my handkerchief in his mouth, and when he started to kick I simply choked him into submission.

'After that it was plain sailing. We tied the pair up like mummies, gagged and left them, then turned our attention to the sausage.

'Alone, I could not have managed it, but luckily Harington had had some experience of balloons, and he understood how to release her. Even so, it took some time, and we were in a deadly fright that some one might hear us.

'The moment we got the fastenings loose up she went like a rocket. Before we could get our breath we were clear of the fog cloud that shrouded the Secret City, and, high as we had risen, in air that was much warmer than it had been down within the radius of that fearful Cold Ray.

'I simply lay back and gasped with relief. We had been three hours on that abominable island, and it was like heaven to get away. Yet when I came to think of it, our position was pretty desperate.

'There we swung, a mile above the Baltic, without food or drink or even an overcoat between us. What was worse, we were absolutely at the mercy of the wind. As I have told you, the breeze was easterly, but who could tell when it would change? At this time of year the wind is generally westerly, and if it did turn and come from that quarter it would carry us either into Russia or Germany.

'Even if it remained easterly, it seemed to me that we had either to descend in Sweden or Norway, or else be carried out and dropped in the North Sea. Into the bargain, it seemed certain that before long the balloon would be missed and chased.

'However, it was not a bit of use worrying, so we simply sat tight. The breeze was very light, and it was a long time before we lost sight of the big white patch of fog and ice that we had left behind us.

'It faded away at last, and we drifted over a number of other islands. We could spot them by their lights set in queer patterns on the face of the dark sea.

'Then we sighted more lights, and I made up my mind we were over Sweden.

'Dawn came at last, and found us both stiff with cold. Looking down, I saw mountains below, and told Harington that we must be over Norway.

'He suggested that we had better try to land, but the whole country below was a tangle of woods and rocks and lakes. I told him that it was hopeless. We should only smash up the balloon and ourselves, too.

'He agreed that this was pretty likely, but pointed out that there were two parachutes in the car, and that we might descend in those.

'I thought it over, and finally told him that he could try it if he liked, but that I fancied it would be best for one of us to stick to the balloon. My notion was that, once over the North Sea, I should be certain to spot some of our fleet, and could easily drop and be picked up. You understand, of course, that the one thing I was after was to get the news of my find to headquarters.

'"Very well, sir," he said, "I think I'll try my luck. If I get down safe I'll manage to get word through somehow. And, any way, it'll lighten the balloon a good bit, and give you a better chance of making it."

'With that, over he went.

'The moment he was clear, the balloon shot up between three and four thousand feet. The sudden change of pressure made me so dizzy I could hardly see. Still, I did manage to watch Harington. The parachute had opened all right, but it looked to me as though the poor fellow was dropping straight into a large lake. I never saw him reach the ground. There was a gale blowing at the upper height, and it swept me and the balloon off at a tremendous pace.

'In less than an hour I was clear of the Norse coast and well out over the North Sea. There luck failed me. There was a haze below, a haze just thick enough to cut off my view of any vessels. But the wind, which at that height was north of east, carried me on briskly, and I had hopes. You see, I knew that, if it did not change again, I was bound to hit either the English or Scottish coasts.

'So I did. I was actually within sight of land when I saw that Hun plane after me. They had camouflaged her as British for obvious reasons.

'The rest of my story you know, but I should like to say this, Mr Ingram. I should never have had the chance to tell it if it hadn't been for Hallam here, who pulled me out of the sea, and your son who was smart enough to signal you to set off this extraordinary explosive of yours, just in the nick of time.'

He stopped and lay back in his chair. There was silence for some moments, then Mr Ingram spoke.

'All that I can say, Lieutenant Anson, is that it is a very fortunate thing for England that you have escaped to tell this story, and that the sooner the Admiralty have your news the better. And I will tell you another thing. In my opinion, the matter is so important that I think it should be put into writing at once.'

Anson nodded.

'It would be rather a good egg,' he answered. 'As a matter of fact, I did make a few notes in pencil on my way across. Here they are, and a rough sketch map. If you could get them copied out I'd sign them, and that would be some sort of safeguard.'

Guy jumped up.

'I'll do it,' he said eagerly.

Anson thanked him, and handed over the rather battered pocket book.

'I shall leave the notes in your charge, sir,' he said to Mr Ingram. 'And as for me, I must shove off to town as quickly as possible. What's the best way of getting there?'

Mr Ingram glanced at the clock.

'Just after four,' he said. 'There's a good train from Brocklesby Junction at eight thirty which goes right through.'

'And how far is the junction?' asked Anson.

'Fourteen miles from here. Guy shall drive you over in the car. We have a two-seater, and they allow us just enough petrol for station work. There is no need to hurry. If you start at half-past seven you should have plenty of time.'

'In that case,' replied Anson, with a smile, 'I'm going to claim your promise, Mr Ingram. You said you would tell me about that neonite, you know.'

'You saw what it did,' laughed Mr Ingram.

'I should jolly well think I did. That's just what makes me so keen. But I'll tell you this, if I hadn't seen it I'd never have believed that any explosive could do what that did. I mean, unless you used about ten tons of it.'

'That charge was fifteen pounds,' replied the inventor quietly.

Anson shrugged his shoulders.

'You'll have to tell me now. If you don't, I shall have to say that I can't believe it.'

'Guy and Wallace will back me up,' said Mr Ingram. 'They were with me when I weighed it.'

'That's true, Lieutenant Anson,' said Guy.

Anson turned to Guy.

'You needn't be so beastly formal,' he said quickly. 'Anson is good enough, if you don't mind. One doesn't stand on ceremony with a chap who has saved one's life.'

Guy flushed with pleasure. Mr Ingram cut in.

'Guy might be a lieutenant himself by this time, if the doctors would have passed him,' he said, in his quiet way. 'It's rough on him, for he's as keen as any man can be on the Navy. And as I dare say you have heard, he got that limp in getting another boy out of a burning building.'

'I hadn't heard,' replied Anson. 'And I agree that it's jolly rough on him. But never mind, Hallam, I'm sure you are doing just as good work for your country as if you were in a battleship.

'And now, Mr Ingram,' he continued, turning to the elder man, 'what about the neonite?'

'There is not really much to tell you,' answered the other. 'Years ago I had the idea that, by combining nitrates with one of the rarer elements I could produce an entirely new form of explosive. For the rest, it was merely a matter of experiment. That I have had some success seems to be proved by to-day's achievement.'

'I should rather think you had,' declared Anson with enthusiasm. 'I've had a good bit to do with explosives myself, but the effect of that was absolutely new to me.

What struck me was the amazing displacement of air. Why, a regular gale came in from the sea.'

Mr Ingram nodded.

'That's the secret. The actual result of the firing of neonite is to cause a complete vacuum over the whole area of the explosion. For the moment the ordinary pressure of the atmosphere, which, as you know, amounts to fifteen pounds to the square inch, is absolutely removed. You realise what must happen.'

Anson pursed his lips in a low whistle.

'I should rather think I did. Why every cell in every living thing within that area must burst open. Good Heavens, what a ghastly business!'

'Ghastly is the word for it, my boy,' replied Mr Ingram gravely. 'It means that all animal and vegetable life within the pressure area is instantly and utterly destroyed. I reckon that if a fifteen pound shell full of neonite were exploded in the middle of Trafalgar Square, all life would cease within that space. What is more, every house of which the doors and windows were closed would be burst open and destroyed.'

Anson shook his head.

'It's the most terrible invention I ever heard of,' he said slowly. 'A few score shells would destroy the largest city in the world.' He paused and considered for a few moments. Then his face brightened and his blue eyes gleamed.

'But I tell you this, Mr Ingram. Any nation possessing such a secret could win the war single-handed.'

'That I believe to be true,' replied the inventor. 'And I will confess to you that it is only with the hope of destroying the brutal force of Germany that I am going on with neonite. Without that hope, nothing would induce me to make my secret public.'

'But how can you use it?' asked Anson. 'Is it safe to handle?'

'Perfectly! It can only be fired by a special fuse also of my own invention. You can pound it with a hammer or burn it in a fire with perfect safety.'

'And you can fire it from an ordinary gun?'

'You can. But, as a matter of fact, I have devised a new gun by means of which I can throw large shells to practically any desired distance, and that without any sound that could be heard two hundred yards away.'

Anson's eyes widened. His face showed his amazement.

'It is really very simple,' went on Mr Ingram, smiling. 'The gun I speak of is on the electric principle. Have you ever heard of the Bachellier electric railway?'

'Yes. Bachellier used the repulsion and attraction of certain metals, didn't he? When his car started it rose clear of the rails and ran between guides.'

'That was it. Well, my gun is on similar lines. It is a tube of any desired length made of spools of soft iron and aluminium, and wound with copper wire. No rifling is necessary, for the projectile itself is winged. I have already built a small gun, and I reckon that if I constructed one 300 feet in length and used about 300 horse power, I could get a muzzle velocity of nearly five miles a second.'

Anson could only gasp.

'You work miracles, sir. I can hardly follow you.'

'Well, come and see the gun.'

'And I'll go and get the car ready,' said Guy. 'Oh, and what about von Fromach? I suppose the fellow ought to have something to eat.'

'Yes, we must keep him alive until we can hand him over to the military authorities,' said Mr Ingram. 'He and the remains of his plane are the chief proofs we have of the truth of Anson's story. But don't go alone, Guy. The man is dangerous, and it won't do for any of us to enter his prison without a second person.'

'Very well, sir,' agreed Guy. 'Then I'll get the car ready and wait until you come back.'

Guy took extra pains with the car. So far as he was concerned, he meant to make certain that all would go well with Anson's journey up to London. Young as he was, he realised as clearly as Mr Ingram himself the enormous importance of Anson's discovery. He filled the petrol tank, greased wheels and bearings, and ran the engine to make sure it would start easily.

When he came out of the garage he found that the weather was changing. Gray fog clouds capped the high moors inland, and a thin drizzle had begun to fall.

'Going to be bad for our drive to Brocklesby,' he said, frowning a little. 'We must start early. It won't do to risk fast travelling on those hills in fog.'

As he reached the house Mr Ingram and Wallace came out. Wallace was carrying a tray with some food on it.

'Grub for the Hun,' he explained to Guy. 'If I had my way he'd get bread and water, but dad won't have reprisals, and he's going to get cold meat and cheese.'

'It's more than I should have got if they'd caught me on Rosel Island,' said Anson dryly, as he came out behind the others. 'Just about time for us to start, isn't it, Hallam?'

'The car's ready,' replied Guy. 'And I've got out an overcoat for you.'

Anson looked at Guy.

'Couldn't you come up with me?' he said suddenly.

Guy started. He looked eagerly at Mr Ingram.

Mr Ingram considered a moment.

'It would not be a bad idea. To tell truth, I was thinking of it myself. Your testimony would be useful at the Admiralty, Guy. Can you pack in ten minutes?'

'Five,' said Guy, and bolted indoors.

He rushed to his room, seized a bag, and was flinging things into it when he heard a shout outside.

'Guy! Guy!'

It was Wallace's voice, and the dismay in it startled Guy. Dropping everything, he ran out.

Wallace met him. Wallace, white-faced and more excited than Guy had ever seen him.

'He's gone!' gasped the boy.

'Who has gone?'

'Von Fromach. He has escaped.'

'How can he possibly have escaped?' demanded Guy. 'The door was locked. There was no way out.'

'The skylight's open. Some one must have helped him.' Guy stared a moment at the other. Then his lips set, and his whole face hardened.

'It's Cratch!' he said, in a hard, level tone.

'AREN'T you going a bit fast, Hallam?' asked Anson, as he stared through the screen at the low banks looming mistily through the fog, on either side of the road.

'I've got to,' Guy answered. 'I've got to crack on if we are to catch that train. We were a good quarter of an hour late in starting.'

'Through that swine of a German,' said Anson angrily. 'D'ye know, Hallam, I'm half inclined to think that we should have done better to put off our trip until the morning. I don't like the idea of Mr Ingram and his son being left alone to hunt for that ugly brute.'

'I told Mr Ingram so,' replied Guy. 'But he wouldn't hear of it. He vowed that he and Wallace could manage all right, and told me that the great thing was to get you up to town as quickly as possible.'

Anson grunted. He did not seem to be convinced.

'A few hours would not have made much difference one way or another,' he said. 'As it is, I'll bet we shall be kept hanging about for hours on the Admiralty doorstep. And then some red-tape-tied big wig will hum and haw, and want a certificate from an inspector in lunacy before he'll believe a word I say.'

Guy did not answer. All his attention was taken up with handling the car. If there is one form of driving more dangerous and difficult than another, it is to keep a car going in a fog on an open road. Where there are hedges or trees the driver has some sort of guide. Here on the open moor there were only the low banks on either side, and sometimes not even these.

The lamps did not help a bit. In fact, they only made things worse by flinging a white glare on the fog in front.

For some minutes they had been coasting at a moderate pace down a long hill. Now Guy took off both brakes, and pressed down the accelerator.

'It's all right,' he said to Anson. 'We're at the bottom now. I may just as well gain all I can by rushing this next hill.'

'But we are not on the up grade yet,' objected Anson.

'We shall be in a minute,' replied Guy.

The words were hardly out of his mouth before there was a crack like a rifle shot, and the light car swerved violently.

Guy cut off gas, and flung on both brakes. Before he could pull up there was a second report as loud as the first. The car stopped abruptly.

'Both front tyres!' groaned Guy. 'What wicked luck! Must be some monkey business, for both covers were nearly new.'

'Don't stop her,' said Anson sharply. 'Shove her along, even if you have to run on the rims.'

'Too late,' Guy answered. 'I've cut out the engine.'

'Wait. I'll wind her up,' snapped Anson, and leaped out.

As he did so something swished through the air and came down with a thud across the back of the seat, on the very spot where Anson had been sitting the instant before.

'Look out, Hallam!' came a quick cry from the young lieutenant, and Guy leaped to his feet just in time to see a figure, dim in the mist and twilight, leaping on to the back of the car.

In spite of his lame leg, Guy was active as a cat. And he had his wits about him. He did not hesitate for even a fraction of a second. Whirling round, he jumped on the seat, and flung himself straight at the attacker.

The latter had put all his force into the blow with which he had meant to out Anson. He had not time to straighten himself before Guy was on him. Guy caught him round the neck with both arms, and threw his whole weight forward.

Caught off his balance, the man staggered backwards and, with Guy on top of him, went clean over into the road.

Falling on top of him, Guy was not hurt, but the force of the fall knocked the wind out of the other, and it was a moment or two before he could recover.

From close by came the sound of heavy breathing and the dull thud of blows. Guy realised that Anson was being attacked, and scrambled up as quickly as he could.

As he did so the man beneath him caught at his foot and nearly pulled him down. Guy turned on him desperately, and drove at his head with his clenched fist.

There was a shriek of pain, and the fellow writhed a moment, then flattened out and lay still.

Guy jumped clear. The fog was thicker than ever, and the dusk was closing in fast. All that Guy could see was dim forms rolling over and over on the grass at the side of the road.

'Anson! Anson!' he cried, as he flung himself towards them.

'Here! Quick!' came Anson's voice, thick and half smothered.

As he came up, Guy saw that there were two men on top of Anson. A third stood by, with something in his hand that looked like a short, thick stick. It came to Guy in a flash that it was a sand-bag such as the first man had used. The fellow was waiting for a chance to bring it down on Anson's head.

But Anson, judging by the way in which the struggling figures on the ground were heaving to and fro, and the savage but low-voiced curses that came hissing from his assailants lips, was putting up a pretty stiff fight.

As quickly as he had tackled number one, Guy went for the man with the sand-bag. But this chap saw him coming, and hit out for all he was worth.

Guy flung up his left arm to protect his head, and the sand-bag struck him over the shoulder, numbing the muscles so that the arm dropped useless by his side.

But the blow did not check him, and his right fist met his opponent's jaw with a force that knocked the fellow clean off his legs, and stretched him gasping and clucking on the wet turf.

Guy wasted no more time on him, but jumped into the fray, and, stooping, got hold of one of Anson's assailants by the collar with his sound arm.

Putting forth all his strength—and Guy had more than many a grown man—he jerked him backwards with all his might, and tore him clear off Anson.

With a snarl of rage the burly brute was scrambling to his feet, but Guy, realising that with his damaged arm he would not stand a dog's chance against him, threw scruples to the winds, and kicked him on the shin with all his force.

The man gave a howl of agony, and staggering back fell over his companion, whom Guy had floored already, and went crashing into the ditch beyond.

Once more Guy turned to Anson's help, but this time it was not needed. Left with only one man to tackle, Anson was quite equal to the occasion. Guy saw him kneeling on the spy's chest and throttling the fellow in a most satisfactory manner.

The man was kicking and struggling like a newly-landed fish, and his struggles were so tremendous that Anson was flung up and down like a pea on a drum. But he hung on like a bull dog, and in a very few seconds Guy heard a nasty choking rattle, and saw Anson's opponent go limp as a wet bootlace.

Panting and almost breathless, Anson struggled to his feet.

'Good for you, Hallam!' he said. 'Jove, you were only just in time. The two were more than I could manage. Where are the others?'

'All outed more or less. I'm not so sure about the last one. He's in the ditch there.'

'We must make sure of him,' said Anson curtly. 'If he gets away he may bring help. Got anything to tackle him with.

'Hallo!' he broke off sharply, 'you're hurt.'

'Nothing much,' said Guy. 'One of them got me a wipe with a sand-bag. I can't use my left arm yet, but I expect it will be all right in a few minutes.'

'Will it?' said Anson grimly. 'I'm not so sure. Here, let me see.'

'Wait, we must see about that fourth man before we do anything else,' returned Guy. 'Where's your pistol?'

'In my hip-pocket. Can you get it out for me?'

'Me? Yes, but what—. Oh, hang it all, Anson, it's you that are hurt!'

'One of those swine got a knife into me somewhere,' Anson answered. 'Right shoulder, I think. But it's nothing to make a song about. I—'

His voice had gone oddly hoarse. He staggered. Guy had just time to fling his sound arm around him and save him from falling.

'I—I'm all right,' muttered Anson, making a violent attempt to pull himself round. Then he collapsed completely, and lay a dead weight in Guy's grasp.

Guy laid him down, and with his sound hand opened Anson's jacket. Waistcoat and shirt both were wet and warm. It was a deep cut, and was bleeding fast.

Taking out a handkerchief, Guy set to tear it into strips to bandage the wound. He found that this was impossible. His left arm was still completely useless, and he could do nothing with one hand.

He groaned with despair. Guy was not a person to be easily discouraged, but never in his life had he felt so completely helpless. The car was useless, and even if it had not been disabled, he could not drive it with one hand. He was alone in the dark and the fog, with Anson apparently bleeding to death before his eyes, and there was nothing he could do to help him.

To make matters worse, one, if not two, of their late opponents were not yet completely outed, and if any fresh attack were made he could do nothing to hold it up.

Stay, though! There was Anson's pistol. Guy managed to lift the young sailor slightly and get out his automatic.

As he did so he distinctly heard a rustle in the long grass close by. He raised the pistol and pointed it in the direction from which the sound had come.

Again the rustle. Guy stood absolutely motionless. The suspense was horrible. He did not know whether to fire or not.

It seemed to him that some one was crawling slowly up the ditch, but strain his eyes as he might, he could get no glimpse of him. He could hardly breathe. If Guy had been alone, he would have made a rush and chanced it. But he had Anson to think of, and Anson's life, he knew, was far more valuable than his own. Anson was the only man in England who knew of the existence of the Secret City, and it was up to him to see that Anson lived to tell his story.

It was very nearly dark now. But not too dark to see the tall marsh grass that rose like a screen above the ditch. And it was moving. It was surely moving. Guy strained his eyes until they ached. He felt just then that he would have given anything to know whether it really was that fourth man crawling nearer, and whether he had a pistol or not. It struck him as strange that the gang had not used fire-arms, but it was quite likely that they had purposely refrained from doing so. The spot where the car had been held up was on the edge of the moor, and Guy knew there were farm-houses not far away. Unfortunately, he had no idea in which direction.

He glanced down again at Anson. The young sailor lay terribly still. For all Guy knew, he might be dead already, and the idea drove him nearly frantic.

The strain was almost beyond endurance, and Guy was beginning to feel perfectly sick with suspense when suddenly a new sound came dully through the rolling billows of fog.

Guy stiffened, and stood listening breathlessly. Surely it was the distant hum of a motor engine. A moment later, and he was certain that a car was coming from the opposite direction.

His finger tightened on the trigger. Then he paused again. It struck him that this might be the gang's own car bringing them help.

Once more the grass rustled. Guy saw, or thought he saw, something dark behind the waving screen. He waited no longer, but fired straight at it.

With the wicked crack of the automatic came a yell of agony. There was a heavy fall, then silence.

Next moment Guy heard the deep hum slacken. The car was stopping. But it was so near now that he could see the glow of the lamps through the fog. Throwing prudence to the winds, he dashed out into the road and shouted at the top of his voice.

The car stopped.

'Who is it?' came a sharp, commanding voice. 'Stop where you are. I am armed.'

Guy pulled up short.

'Two Englishmen attacked by German spies,' he shouted back.

There was a low-voiced exclamation of surprise, then steps rang clear and sharp on the hard road, and a man came quickly forward.

There was a click, and a flood of white light from a powerful electric torch cut the fog and fell full upon Guy and Anson, and upon the two of the gang who lay insensible on the trampled turf.

'Gad, it's true!' said the man with the torch. 'What luck! What wonderful luck!'

Guy stepped forward to meet him.

'My friend—Lieutenant Anson!' he said. 'Quick! Help him. He is bleeding to death.'

His voice went suddenly hoarse and weak. He staggered. But before he could fall a strong arm saved him, and laid him gently on the grass.

'All right, my lad,' said the stranger. 'Lie still a minute. I'll see to your friend.'

GUY did not actually faint, but for a moment or two he must have been pretty nearly unconscious, for the next thing he was aware of was the sharp taste of spirit in his mouth.

'Swallow it down,' said the voice, and there was a tone in it which comforted Guy mightily. 'It'll do you good. You look as if you had had a pretty rough passage. Is that arm of yours broken?'

'I don't think so, sir. But Anson—what about him?'

'Nothing serious. He has lost a lot of blood, but I have stopped it, and he will be all right. Now sit up and let me look at your arm.'

Guy sat up readily. He was still a little dizzy, but the faintness was passing away. While the stranger examined his arm, Guy examined him. He seemed to be about forty, a square-shouldered, deep-chested, well-built man who looked as if he might have been a retired cavalry officer. He had as keen a pair of eyes as Guy had ever seen in a human face, but apart from these eyes, which were of a curiously steely-blue colour, there was nothing remarkable about him.

'Bones are all right. That's a good job. But you are badly bruised, my boy, and those bruises will lame you for a month if they are not attended to pretty soon. Where do you belong?'

'Claston, sir,' said Guy.

'Are you Mr Ingram's son?'

'No, his assistant, sir. My name is Hallam. But we can't go back. We are on our way to London.'

'London! How do you expect to get there?'

'By train. We were going to Brocklesby to catch the 8.30.'

The other glanced at a wrist watch.

'That leaves in five minutes, Hallam. So I am afraid it is out of the question. Besides, you are neither of you fit to travel! Anson, especially, should be in bed for some days. The best course will be for me to drive you back to Claston. But, first, I must see about these cattle.' He pointed contemptuously to the men on the ground.

'There's a third in the ditch, sir,' said Guy. 'I shot him just as you came up. I had to. I thought he might kill Anson. And Anson—'

Guy cut himself short abruptly. He felt he had been on the verge of saying more than was wise.

The other nodded.

'Quite right. I see there is more in this than meets the eye. I shan't ask for any confidences until you feel inclined to give them. Meantime, sit tight until I make these animals fast. I can leave my chauffeur to guard them and your car, and come back for them after I have taken you home.

'Oh, and my name is Vassall,' he added briefly.

He gave a call, and a second man appeared—a man in chauffeur's uniform; yet to Guy he looked much more like a sailor than anything else.

'Garland, I want you to take charge of these prisoners while I drive these gentlemen back to Claston. Take the flask, my torch, and the first-aid case. Keep the swine alive if you can. If I am not mistaken, they are the very gang we were after. I should like to be sure that they are properly hung later on.'

Vassall's voice rang suddenly grim, and Guy wondered greatly who he was, yet felt certain that he was to be trusted.

Between them, Mr Vassall and Garland lifted Anson into the tonneau, and made him comfortable. Guy got in beside Vassall, and the car, which was a big and powerful one, swept away. Guy noticed with interest that she had some sort of fog-piercing lenses on her headlights. Even in the thickest of the smother her driver did not drop to less than twenty miles an hour.

Vassall kept his word, and did not ask a single question on the way back. Guy, who instinctively felt that he could thoroughly trust this new acquaintance, longed to tell him all about the extraordinary happenings of the day, yet felt that he must not do so without knowing definitely who he was.

As for Anson, he was in no condition to talk at all. Although he had come back to his senses, he was almost too weak to move, and lay quite still in the tonneau where he had been placed.

Within less than fifteen minutes the lights of the lonely house at Claston glowed dimly through the fog, and Vassall drew up at the door.

To Guy's surprise, Mr Ingram himself came out. There was dismay on his face when he saw Guy and Anson.

Guy explained rapidly.

'We were attacked on the road, Mr Ingram. This gentleman, Mr Vassall, came to our rescue and brought us back. There's not much the matter with either of us, only Anson is not fit to travel for a bit.'

'Attacked!' exclaimed Mr Ingram. 'Cratch again, I suppose,' he added bitterly.

'Who is Cratch?' cut in Vassall sharply. 'No—wait! I have no business to ask questions until I have given you some proof of my identity. Let us get these two youngsters to bed, and then I should like a few words with you, Mr Ingram.'

Guy was able to get out of the car by himself, but they had to lift Anson.

'Is it serious? Is he badly hurt?' asked Mr Ingram very anxiously.

'No. I can assure you that the wound is nothing,' replied Vassall. 'I know something of surgery, and you can rely upon what I say. The weakness is simply loss of blood. And, if it's any comfort to you, I can tell you that these boys have outed three of this pernicious gang of spies and traitors.'

'I am delighted to hear it,' said Mr Ingram warmly. 'Now help me upstairs, if you will, with Anson. Afterwards I shall be glad to have a talk.'

They put Anson to bed, and Vassall dressed the ugly cut on his chest with as much skill as any doctor could have shown. Then he made Guy strip, and bathed his damaged shoulder with very hot water. By this time the whole upper part of Guy's arm was badly discoloured and swollen. Vassall put on a dressing and ordered Guy to bed.

Later on Hannah, the housekeeper, brought Guy some supper, and Guy begged her to ask Mr Ingram to come and see him before he went to bed.

'I'll tell him, sir,' replied Hannah, 'but he won't be coming yet a while. He and that gentleman are still talking down below.'

It was late before Mr Ingram did come up, but Guy was still awake, waiting eagerly to hear the news.

The moment he set eyes upon Mr Ingram's face he saw that the news was good. The inventor looked much less anxious than he had a couple of hours earlier.

'We are in luck, Guy,' he said. 'Mr Vassall is a Secret Service man, and is, it seems, on the track of this very gang that held you up to-night. He is extremely pleased with you for securing three prisoners for him.'

'Have you told him?' asked Guy breathlessly.

'Everything. He showed me his credentials, so I had no hesitation in doing so.'

'And what about von Fromach?'

'That is a bad business,' said Mr Ingram, frowning. 'We had to give up the search because of the fog. But Mr Vassall is taking the whole affair in hand, and he is a great deal more likely than we to run down this ruffian.'

'Cratch—will he arrest him?' demanded Guy.

'He has to get proof first, Guy,' replied the other. 'But once he has that, I don't think that Cratch will trouble us much more.'

'Good! I do hope he gets him. And now the only thing I still want to ask you about is our trip to town.'

'As for that, you will have to wait until Anson can travel. But since Mr Vassall feels sure that he will be fit to go in three days, the delay will not be a long one. Now, good-night, Guy. You must get some sleep.'

'Oh, I'll sleep all right, sir,' smiled Guy.

Mr Ingram turned to leave the room, then paused.

'You have done very well to-day, Guy,' he said. 'I am very pleased with you. So, too, is Mr Vassall.'