RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

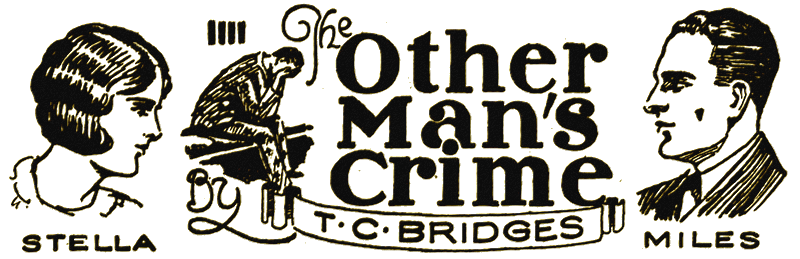

ONE of the beat stories from the powerful pen of Mr. T.C. Bridges is the new serial, "The Other Man's Crime," which is to begin next Friday in the "Queensland Times." Mr. Bridges is well-known as the author of such stories as "The Stolen Masterpiece," "The Gold Magnet," "The Price of Liberty," and others; but in "The Other Man's Crime" the author has excelled himself.

The principal characters in this powerful drama are Miles Hedley, part owner of a gold mine, who sacrifices his liberty to finance it; Maurice Tavener, his rich cousin, whose money buys off justice for a time, but not finally; Stella Drake, the beautiful daughter of Miles's partner, a girl of character and courage who rescues Miles from prison to fetter him as her lover; Jay Scorson, an intrepid young airman, who carries out a daring rescue; and Hester Redmire, daughter of Tavener's gamekeeper, whose jealousy discloses the truth.

Readers are promised a story full of absorbing interest.

Headpiece from The Evening News, Rockhampton, Qld, 4 Jan 1932.

"FIVE thousand pounds," repeated Maurice Tavener. A slow smile crossed his face as he glanced at his cousin who sat beside him in Maurice's magnificent two-seater Rolls, "Bit of an optimist, aren't you, Miles?"

"Why do you say that?" asked Miles Hedley.

"Because I think it," retorted Maurice. "And because it's quite plain that my opinion is shared by others. By your own account you've tried everywhere for the money without success."

"I've tried the firms to whom I had introductions," corrected Miles in his light tones.

"And none of them would shell out," said Maurice.

"That's true," Miles's voice was bitter. "They re all asleep, these London firms. They don't know a good thing when they see it. They'll kick themselves when someone else with a little more enterprise scoops a fortune." Maurice pursed his lips.

"What proof have you that there's a fortune is your mine, Miles?"

"I have the ore samples. I have Drake's sworn statement as to the vein and the formation. I can't see what more anyone wants."

Maurice turned the car off the main road to a steep-sided Devonshire lane. It was narrow and rough, so he slackened speed.

"My dear fellow," he said, in a slightly patronising tone, "London is full of men with ore samples and sworn statements by mining engineers, and to this case your report is nullified by the fact that Drake is joint owner with you to this new prospect."

"The report is signed by Juan Sanchez," interrupted Miles. "He's an expert."

"He may be in Bolivia, but his very name is enough to queer him in England. Frankly, I'm not a bit surprised at your failure to raise the money you want."

Miles's heart sank like lead. He had hoped to interest Maurice in this gold mine, which he and his partner, John Drake, had found in Bolivia. The ore was amazingly rich, but they two had no money to work the mine, to hire the necessary labour, or to buy machinery. He and Drake had scraped together their very last two hundred pounds to take Miles to England to raise capital, but a fortnight's hard work in London had gone for absolutely nothing. Maurice Tavener, his cousin, was a very rich man, and when he had asked him down to stay at Foxenholt for a week-end Miles had jumped at the chance. Now, however, his bright prospects were fading, for Maurice seemed as sceptical as the heads of those city firms whom Miles had already tried in vain to interest.

The car drew in through a drive gate, and Miles decided to wait for a better opportunity before putting his request to Maurice. Then, as the house came into sight, he cried out with delight.

"Like it?" asked Maurice gratified.

"It's perfect," vowed Miles, as he gazed at the long range of low buildings, all of reddish stone and roofed with beautifully weathered thatch, which stood on the hill-side, fronted by a gay garden, and backed by some really fine timber. "But fancy calling that a fishing lodge!" he jeered.

"That's all it is compared with Gaynes," said Maurice. "I only come here for the fishing. There's not a darned thing to do, except fish, and if the water isn't right that's a dull job."

"But you can have as many people to stay as you want."

Maurice pursed his lips. "My pals don't care about the country. I've only one man staying at present. Chap called Vedder. Rather a rum bird, but he's about the best poker player in England, and the luckiest," he added, with a grimace. "You'll meet him at dinner, and—" as he stopped the car—"remember this, Miles, he's got a rum temper, so don't irritate him."

Miles laughed.

"Don't worry," he said. "Trouble's the last thing I'm looking for."

Inside the house was as perfect as out. The front door led into a square hall roofed with wonderful old oak beams. Sporting trophies decorated the walls, and though it was late spring a fire of apple logs burned in an open hearth.

"Tea, cocktail, or whisky and soda?" questioned Maurice as he pointed to two low tables on one of which a silver tea equipage was laid out, while the other held a large assortment of decanters and glasses.

"Tea for me," said Miles.

"Then help yourself, old man," said Maurice as he picked up the whisky decanter and poured out a drink so stiff that Miles's eyes widened. It was years since Miles had last seen his cousin and he realised that these years had not improved him. Maurice was a tall, powerfully-built man, but, though not yet thirty, he was already running to fat. His face was a little puffy, his hands were too white, and though his manner was entirely genial, there was a smouldering something in his dark eyes, which told Miles that his temper, if roused might be extremely ugly. Too much money, too little to do. An old story, and Miles repressed a sigh as he thought how unevenly this world's gifts are divided.

"What's the matter, Miles?" chaffed Maurice. "You're looking as solemn as an owl. It's the tea, I expect. You want a man's drink."

"I'll have one—after dinner." replied Miles smiling. "But a cup of decent tea is a treat and these tea-cakes—I haven't tasted anything so good for years."

"What do you live on, out in Bolivia?" asked Maurice.

"Beef mainly, but its stringy stuff, and the bread is mostly maize. Still it's a fine country. You ought to come and see it, Maurice."

"Me! Good Lord, man. I'd die."

"You wouldn't. You'd get jolly fit climbing those mountains. And I could show you our mine."

"Still harping on your blessed mine," said Maurice "You'd much better chuck it and settle in England." He glanced at his cousin's lean, well-knit frame, and his brown face with steady eyes and strong jaw. "A chap like you could get a job easy enough."

"My job is in Bolivia," replied Miles quietly. "Even if it wasn't I couldn't let Drake down and—Stella."

"Who's Stella?" demanded Maurice. "Mrs. Drake?"

"Miss," corrected Miles. "His daughter." Maurice's eyebrows rose.

"A girl. I begin to see."

"There's nothing to see," said Miles. "Not the way you mean. Stella is like my sister, but she and her father are relying on me to raise the money for working the mine." He paused but Maurice did not speak. Still he seemed interested, and Miles made up his mind that the time was as good as any to make his request. "Maurice," he went on. "Its a good show. The vein is rich and we have proved it for the whole length of our claim. There is a fortune in it if we have the capital to work it. Do you feel inclined to advance the necessary five thousand?"

Maurice's face hardened at once. "What security have you to offer?" he asked.

"A mortgage on the whole property."

"And what is the claim worth as it stands? For how much could you sell it?"

"Sanchez offered us two thousand," Miles answered. "That was all he could raise. He freely admitted it was worth more. As I tell you, the ore is extraordinarily rich."

"So you want five thousand pounds on security for which the top price is two thousand. It's not good enough, Miles."

Miles refused to be discouraged.

"Won't you gamble, Maurice? We will give you a quarter share for five thousand pounds, and I am not exaggerating when I say that there is a million in it."

"You mean you think there is a million?" said Maurice curtly. "I know gold mines. I've been bitten before now. The vein which shows rich on the surface pinches out, or the shaft fills with water or you can't get labour. No, Miles, my expenses are very heavy, and I haven't five thousand pounds to chuck away. As I said before, it's not good enough."

Miles sat perfectly still. His one idea was not to show how heavy the blow was that Maurice had dealt him. It was only now that he realized how completely he had been banking on his cousin's assistance, and his refusal to help had knocked the last prop from under him. There was not another soul to whom he could turn for help, and the feeling of failure was bitter indeed. It was bad enough for himself, yet it was not of himself that he was thinking, but of sturdy old, hard-working John Drake, and of his daughter, Stella. As in a dream he heard Maurice speaking again.

"Sorry, Miles," he said, "but you see how it is. You'll have to chuck this wild-cat scheme, and get a job in England. Secretary or land agent. I'll see if any of my pals can help you."

"Thanks," said Miles quietly, "but I'm going back to Bolivia on Monday."

Before Maurice could reply the door banged open. "Your fishing is rotten, Maurice," said a harsh voice. "I've a damned good mind to pack and drive back to London to-night."

THE speaker was as tall as Miles himself, that is half an inch over six feet. He was sandy-haired, thin-lipped, with greenish eyes, and so sour a look that Miles took an instant dislike to him. He wore a rough tweed suit with brogues and waders, and had a creel on his back.

"Water like gin," he went on angrily. "You might as well try to catch trout in the road."

Knowing Maurice's temper, Miles fully expected him to flare up. Instead Maurice laughed.

"I didn't make this weather," he answered. "Have a drink, James, and you'll feel better. Oh, and let me introduce you to my cousin, Miles Hedley."

James Vedder gave Miles a curt nod, which was returned equally briefly. He poured himself out three fingers of Scotch, dashed it with soda and swallowed it. Miles got up.

"What time is dinner?" he asked.

"Eight," Maurice told him.

"And it's not five yet," said Miles. "If you can lend me a rod I'd like to see if I can still throw a fly."

"You're on," said Maurice, "Come into the gun room, and I'll find you all you want. You mustn't mind James," he added as they left the hall. "I told you he had a rum temper."

"He has," agreed Miles drily. Inside ten minutes, Miles, fitted up with rod, landing net, and waders, was walking down to the Strane, the pretty trout stream which ran at the bottom of the hill. As Vedder had said, the water was low and clear, but a little breeze was blowing up stream, and fish were rising in the flat pools. Miles had not cast a fly for years, but most of his boyhood had been spent in Devonshire, and casting is a trick you never lose any more than skating or swimming. After a very few minutes he found his old skill coming back and his fly falling lightly on the ripples. There was plenty of cover along the banks and taking every advantage of this Miles was soon fast in a brisk half-pounder, which he presently netted and transferred to his creel. In the next pool he got a second fish, and when it was time to hurry back to dress for dinner he had nine really nice trout in his creel. He was feeling happier, too, for there is nothing like fishing to take one's mind off one's troubles. After getting quickly into dinner jacket and white shirt he ran down to find Maurice admiring the trout which had been laid out on a dish on a table in the hall. Vedder came down a minute later, and Maurice turned to him with a laugh.

"What about these, James?" he asked. "Here's one man can catch fish if you can't."

Vedder looked at the fish and looked at Miles. "What did you get these with," he asked, "a worm?"

Miles was a man who usually had a good control of his temper, but the insult was so gross, so utterly uncalled for that he went hot all over.

"What a nasty mind you must have, Vedder," he said coldly.

An unpleasant glare showed in Vedder's greenish eyes.

"What exactly do you mean by that?" he demanded, and his voice was dangerous.

"What I said. It takes a nasty mind to think of such a thing."

Maurice stepped between, and only just in time.

"Shut up, James," he ordered harshly, "You dry up, too, Miles."

"I'm sorry, Maurice," said Miles, "but really, you know it was a bit thick."

"It was," allowed Maurice. "James owes you an apology." Vedder hesitated. He was still scowling.

"I'm sorry," he said at last, but with a very ill grace, and just then Jarman, the butler, came in to announce dinner.

The meal, like everything else Maurice's household, was perfect of its kind, yet, in spite of the good food and wine, it was not a success. James Vedder was still sulking, and Miles was wondering how Maurice could put up with such an ill-conditioned brute. Of the three Maurice was the only one who made any real effort to keep up a conversation, and he found it difficult. Miles was glad when the meal was over and they were able to go into the hall for coffee and cigars. The trout had been removed, but Vedder was still sulking and Miles grew sick of it at last and strolled out of the open front door to watch the glory of the afterglow. Presently Maurice followed out.

"Miles," he said, "you play cards, don't you?"

"Bridge and piquet," replied Miles. "Not much else."

"What about poker?"

"Oh, I've played poker, of course."

"Then will you make a game?" Miles laughed a little bitterly.

"My dear fellow, I have just enough money left to pay my fare back to La Paz." For the first time since they had met, Miles saw Maurice flush and look embarrassed.

"I—I didn't know it was as bad as that." He paused and seemed to be searching for words. At last he went on. "See here, Miles, I have my reasons for wanting to keep on the right side of Vedder, and he is keen on a game. If you'll chip in I'll take it as a favour, and if you'll allow me I'll be responsible for any losses you may incur." Miles's first impulse was to refuse, then he remembered that he was his cousin's guest, and he saw, too, that Maurice was very seriously in earnest. He shrugged.

"If you put it that way, Maurice," he said briefly. "My only stipulation is that you take my gains as well as my losses."

"It's awfully good of you," said Maurice gratefully, and pulled a bundle of notes from his pocket. "These ought to see you through. We're going to play in the smoking-room."

The smoking-room was small, but extremely comfortable, and a poker table was set out with cards and chips. A small fire burned in the hearth and shaded electrics lit the room. On a side table was a full array of decanters, siphons and glasses, cigars and cigarettes. Vedder was waiting when the other two came in, and Miles saw the gambler's fire burning in the man's green eyes. He wondered more than ever what hold this unpleasant person had over his cousin. Vedder shuffled the cards with practised fingers.

"What's the limit?" he asked.

"The usual, I suppose," Maurice answered. "Five pounds and five shillings to come in."

"Suits me," said Vedder briefly, but Miles felt uncomfortable. He had never sat in any game where the limit was more than five shillings; but since he had agreed to play, and since he had Maurice's money in his pocket, he felt he could make no objection. Each man started by the purchase of one hundred pounds worth of chips, and the game began. Poker is a simple game, with none of the demand on skill and memory of bridge. The main point is to gauge the style of your adversaries' play and bet your Cards accordingly. At first things went very quietly, and for half an hour the biggest hand held by anyone was three kings. Miles held that against two pairs, aces high, and took fifteen pounds off Vedder. By degrees things warmed up, but the luck remained with Miles, and the pile of chips in his trough steadily increased. Most of his winning was at Vedder's expense, and at the end of an hour Vedder had to buy a second hundred pounds worth of chips. Maurice neither lost, nor won. His cards were not too good, but he played them well. Then the luck shifted and Maurice began to hold the hands. Nothing he could do was wrong, and Miles, who had the true card sense, lay low, but Vedder tried to back the luck, with consequences disastrous to his pocket. Soon he had to shell out a third hundred, and the scowl on his unpleasant face grew permanent.

A jack pot was opened by Vedder, who drew two cards only. Miles had a pair of tens and drew a third. Maurice also drew three cards and the betting began with a five pound chip from Vedder. Miles raised him and Maurice raised again.

"Five better," said Vedder briefly, and Miles dropped out.

"Another five," said Maurice, and Vedder simply pushed up two more chips. To and fro went the betting in absolute silence until both troughs were empty, and the heap in the centre represented nearly two hundred pounds.

"I'll take another hundred pounds worth and bet you the lot," snapped Vedder.

"Suits me," said Maurice. "You want a show down?"

Vedder nodded.

"Beat those if you can," he said, sneeringly, as he laid down four nines.

"I can just do that," replied Maurice, as he showed four knaves. Vedder sprang to his feet.

"You dirty swindler!" he shouted. "I discarded a knave." Maurice's florid face went oddly white as he, too, rose from his chair.

"You lie!" he answered curtly.

Vedder's arm shot out, but Maurice dodged the blow, and springing forward planted his fist on Vedder's jaw. The whole weight of his heavy body was behind the blow.

Vedder's hands flew up, he staggered back, and fell with a crash across the hearth rug.

"The dirty liar!" panted Maurice. "A sharper and blackmailer like him to accuse me of swindling! But this finishes it."

"It has finished it!" said Miles, who was leaning over the fallen man. "Vedder is dead, Maurice!"

MAURICE stood gazing at Miles. "Rot!" he said scornfully. "He's only stunned!"

"He is dead!" repeated Miles. "His head, struck the corner of the kerb and his neck is broken." His steady voice terrified Maurice, who stepped quickly across, dropped on his knees beside Vedder, then putting his right arm under his shoulders, lifted him. Vedder's head flopped horribly to one side, and Maurice dropped him with a gasp. His face, as he looked up at Miles, was a mask of terror.

"Good God!" he muttered. "What an awful thing!"

"It's bad," said Miles, soberly, "but, after all, it was an accident, and one he brought upon himself. I can testify to that, Maurice." Maurice shook his head hopelessly.

"They'll never believe that," he said hoarsely. "The whole business will come out."

"You mean there was something between you and him?" questioned Miles.

"Yes," Maurice's voice trembled with horror. "He—he knew something about me—something I did before I came into my money. He's been living on me ever since. It's bound to come out at inquest, and—and they'll never believe it was an accident." He was so terribly upset that Miles felt really sorry for him, but at the same time he realised that something must be done at once.

"Brace up!" he said kindly. "I'll do my best for you. Let me give you a drink." He poured out a stiff whisky and Maurice drank it mechanically, but it had no effect upon him whatever. Miles went on:—

"The police must be informed, Maurice. Shall I telephone for you?"

"No—no!" Maurice was frantic with terror. Miles tried to reason with him.

"See here, Maurice. The business has got to come out sooner or later, and the longer the delay the more fishy it will look. If we get a doctor as soon as possible and explain matters to him, then he will send for the police. Surely you need not be too alarmed. At the worst they can only call it manslaughter, and with my evidence it shouldn't be that. The jury will probably return it as an accident, and that will be the end of it." Maurice listened but he was not convinced.

"No!" he repeated desperately. "If you knew what I know you'd be as sure as I am that they'd hang me or at least give me a long sentence." He looked at the body and shivered. "Can't we hide that, and say he left in a huff?" Miles began to lose patience.

"Do you think I'd lend myself to such a crazy scheme? The chances are that someone in the house has heard the crash of his fall. In any case it would be bound to come out sooner or later, and then they'd have us both for murder. Do let me telephone at once." He started for the door but Maurice caught him by the arm. "Listen, Miles. You wanted me to lend you five thousand to-day." Miles stared. He began to think excitement had driven the other out of his mind.

"What has that to do with it?" he demanded. Maurice went on eagerly.

"I'll give you the money. I'll give you double that sum if—if you'll take the blame." Miles shook him off.

"You're crazy," he said scornfully. "Are you trying to bribe me to say I killed Vedder?"

"Yes," replied Maurice between clenched teeth. "That's exactly what I am trying to do. I'm offering you double the money you asked for if you will say that you knocked Vedder down—in fact, to take my place. It will be enough to start your mine, and, if you are right about the richness of the ore, to give you and your friends a fortune. What's more, I'll get you the best counsel that money can buy to defend you, and if there is any real trouble—I mean if you get a sentence—I'll give you two thousand pounds a year for as long as you are in prison." He stopped and stood looking at Miles with the sort of expression on his face that a man might wear while waiting to see if the judge before whom he stood would, or would not, don the black cap.

MILES stood silent, frowning heavily. His first impulse was to turn down Maurice's mad suggestion with the scorn it seemed to deserve, but as his cousin went on speaking he began to hesitate. Ten thousand pounds! The sum was double that which he had been trying so hard and so uselessly to raise. It would be sufficient not only to start the mine, but to keep John Drake and Stella in comfort until the production stage was reached. The homely, rugged face of John rose before him, then Stella's, with her wide, blue Devon eyes, and he realised how hard it would be to go back to them empty-handed, and tell them of his failure. And failure meant the end of all things, for there was no money to be had in Bolivia.

Ten thousand pounds! He could picture their joy when they received the cheque and the furious energy with which John would start developing the mine. The vein itself was all right. Miles was definitely certain that there was a fortune in it—several fortunes. At the very worst they could hardly give him more than twelve months' imprisonment. It seemed more probable that he would get off altogether. But even if he had to go to prison there was no great disgrace about such a sentence, and certainly in South America no one would think any the worse of him. Maurice, still watching him with the same intense eagerness, saw his hesitation, and spoke again.

"I will give the cheque now—this minute—if you agree, Miles." A surge of anger seized Miles.

"What good is a cheque that can be stopped by wire before it is paid?" he asked, with such sudden bitterness that Maurice recoiled and his cheeks went dull red.

"You—you couldn't think I'd do a thing like that, Miles."

"No, I don't suppose you would, but I'm not taking any chances. Remember you turned me down cold when I asked you for the loan of five thousand."

"I'll do anything you suggest—give you any written promise you please," said Maurice, with intense earnestness. Miles looked at him.

"I haven't consented yet," he reminded the other drily.

"But you will, Miles," Maurice begged. "You can't refuse. Think! For you it means nothing, or next to nothing—just a temporary inconvenience; but for me—well, I have told you that it might be a hanging matter." Miles frowned again.

"I think you are exaggerating. Yet perhaps you know best. If I can be sure of my ten thousand I feel inclined to earn it. But I'm not going to trust you simply because you are my cousin. Listen to me. You are going to write a confession which will be sent in a sealed envelope to my solicitor, with a letter from me that it is not to be returned to you until my trial is over." Maurice bit his lip.

"You're making it pretty hard," he said. "Suppose that confession gets into somebody else's hands?"

"How can it?" snapped Miles. "You can read my letter which goes with it." Maurice considered a moment.

"I agree," he said.

"All right. Then these are my other conditions. The cheque goes with the letter, and you give me another cheque for one thousand for my defence. You will also give me your word not to mention this compact of ours to a living soul—and most especially not to the Drakes."

"I'll do that," said Maurice firmly.

"Then the sooner you start the better," said Miles, "for the longer Vedder's body lies there the worse it's going to be for me."

"I'll get some paper and my cheque book," said Maurice, and went out quickly, whilst Miles stood looking down at Vedder's body sprawled limply on the hearth rug. Even in death the wretched man's face was as repulsive as ever, and Miles could feel no regret at his untimely end. He had not much time for thought, for Maurice came back quickly with writing materials and two fountain pens. Miles took his and a pad of paper without a word and sat down at once to write. Maurice did the same, and for some minutes there was no sound but the rapid scratching of pens on paper.

"Will that do?" said Maurice presently. He spoke in a low, unsteady voice, and Miles realized that the strain was telling on him. Miles read the letter and nodded.

"That's all right," he said briefly, "and here is mine, to Bartlett." Maurice agreed to this and wrote the two cheques. These and the two letters—Maurice's in a sealed envelope—were put together in one large envelope, and this Miles addressed to Bartlett.

"It must be posted at once," said Miles, "it won't do for it to be found on me. I believe they search a prisoner," he added with a ghost of a smile.

"There's a pillar-box at the drive gate," Maurice told him. "You'll like to put it in yourself."

"Yes, but I had better ring up the doctor and the police before I do so," said Miles. "I suppose it will be some little time before they can arrive?"

"Half an hour at least," Maurice answered. "The nearest police station is Taviton, nearly four miles away, and Helmore, the doctor, also lives in Taviton. The 'phone is in the next room."

Miles nodded and went to it. His hand was perfectly steady as he lifted the receiver and asked for the number Maurice gave him. Nearly two minutes elapsed before he got a reply.

"Yes, Sergeant Tooker speaking. Who is it?"

"Mr. Miles Hedley speaking from Foxenholt," replied Miles quietly. "I have to tell you that I have accidentally killed a fellow guest and ask you to come out here at once."

"Killed him!" Miles heard plainly the gasp of amazement which accompanied the words. Then the speaker seemed to realise that it was not part of his duty to give way to his feelings.

"Very good, sir," he said in a calmer voice. "I will come out at once."

Miles hung up. "I'll take the letters now," he said, "and you can call up Helmore." Maurice gazed at him with wonder in his eyes.

"By God, you take it quietly," he said.

Miles's lip curled slightly, but he made no reply. Going out through the hall, he took his hat from the rack, and, unlocking the front door, walked quickly down the drive. It was a heavenly night with a big moon only two or three days past the full, throwing the black shadows of the great beeches across the turf. Rabbits gambolled amid the shadows, and in the distance a brown owl hooted. But to Miles the whole landscape seemed somehow unreal. It resembled a set scene in a theatre. His mind was wrapped up in the tremendous decision he had just taken. He reached the box, slipped the letter into it and walked rapidly back. As he entered the house he heard the hum of a motor engine in the distance. A slight shiver ran through him.

"The die is cast," he said, half aloud, as he hung up his hat and dropped into a chair to await the officers of the law.

THERE was nothing very formidable about the two men who presently entered the house. Sergeant Tooker was big, well over six feet, and heavily built, a fine example, so Miles thought, of the country constable who, by long and steady work, has gained promotion. The other, whose name was French, was a rather beefy and stolid fellow, much younger than his chief. Since the servants had long ago gone to bed it was Maurice who opened the door, and it was to him that Tooker addressed himself.

"Is this a fact, sir—that there's been someone killed?"

"Unfortunately it is quite true, sergeant," replied Maurice gravely. "A terrible accident."

"And this is the gentleman who rang me up?" turning to Miles.

"I am Miles Hedley," replied Miles steadily. "And the fact is as I stated. Mr. Vedder and I had a quarrel over a game of cards. He accused me of cheating. I knocked him down. He fell against the raised fender, and broke his neck."

"He tried to strike you first, remember that, Miles," said Maurice quickly.

"I take it you were present, sir," said Tooker to Maurice.

"Yes, we three were playing together when the quarrel occurred."

"And this other gentleman—you are sure he is dead?"

"Quite certain," said Miles. "I have seen too many dead men to have any doubt on that score."

"Is the doctor here?" questioned Tooker.

"Not yet. We have telephoned for Dr. Helmore, but he has not arrived."

"He's coming now, sir," said French, speaking for the first time. Tooker listened a moment.

"That's right," he agreed, and in a moment they all heard the car coming up the drive. Dr. Helmore was a complete contrast to the two big policemen, a short, wiry Celt, with black hair beginning to grizzle, and grey-green eyes.

"Good evening, Tavener," he said briskly. "What's the matter. Some one hurt?"

"Dead," said Maurice heavily. "It's Vedder."

"Bad—bad," said the doctor, in his quick, clipped voice. "Tell me."

Miles did the telling. His story was the same he had already told to Tooker. Helmore nodded.

"We'd better be sure," he said, and made straight for the card room. It was plain he knew his way about the house. He bent over Vedder, put an arm round him and with unexpected strength raised him. The man's head lolled back in the same dreadfully unnatural way as when Miles had lifted him, and Helmore laid the body back.

"Quite right, Tavener. Your diagnosis is correct. Cervical vertebrae dislocated, and death must have been instantaneous." He turned to Miles: "It was you who hit him?"

"Yes," agreed Miles quietly.

"But it was self-defence. Vedder hit him first," said Maurice sharply. He turned to Tooker. "What happens now? What do you do?"

"I must take Mr. Hedley into custody, sir," Tooker answered quietly.

"What—take him to prison! Surely he can remain here. I can offer bail to any amount."

"We should have to go before a Justice in the matter of bail," explained Tooker. "And in a case like this he would not grant it. But don't worry yourself, Mr. Tavener. We shall make Mr. Hedley quite comfortable, and the inquest will be to-morrow; then if, as seems likely, the jury return 'justifiable homicide,' he will be released at once." Maurice looked anxiously at Miles, but Miles showed no sign of emotion.

"You know best, Sergeant," he said. "I will pack a bag and come with you at once."

"Very good," said Tooker, "but I must ask you to let Constable French accompany you while you pack." Miles's lips tightened. He was beginning to realise the seriousness of the plight in which he found himself. But he made no objection and French went with him upstairs. A few minutes later he was in the car with Tooker and French, driving to Taviton, and the rest of the night he spent in a small, bare, but very clean cell at the police station.

Next morning his breakfast was brought in from outside and at eleven he was driven back to Foxenholt for the inquest. Mr. Shenstone, the Coroner, was already at the house and a jury had been collected. Shenstone was a little, stiff, elderly man, the jury were farmers and tradesmen about half and half, a rather stolid looking lot. Since there was no hotel or public house anywhere near Foxenholt, the inquest was held in a billiards room. There was an arrangement by which the big billiards table could be lowered into a hollow beneath the flooring and its place was taken by a smaller table at the head of which the coroner sat. A couple of reporters were the only strangers present.

Maurice was the first to give evidence. He looked as if he had not slept, and was nervous and shaky, yet he gave his evidence pretty clearly. He described exactly what had happened with, of course, the exception that he put Miles in his own place. He emphasised the fact that Vedder had not only accused Miles of cheating, but had been the first to attack. Mr. Shenstone listened keenly.

"Was there any justification for Mr. Vedder's accusation?" he asked.

"None whatever," replied Maurice. "Mr. Hedley won the hand with four knaves, and Vedder's declaration that he had discarded a knave was nonsense. I can only imagine that he discarded a king and thought it was a knave."

"That is possible, of course," agreed the coroner. "You examined the pack?"

"The pack is before you, sir," said Maurice.

Shenstone ran through it. "There are certainly only four knaves," he agreed with a dry smile. "Yet from your account Mr. Vedder seems to have made the accusation in good faith."

Maurice shrugged. "He was a quick-tempered—I may say a bad tempered man."

"How long had you known him, Mr. Tavener?" Maurice coloured slightly.

"Four—nearly five years. We met first in London and he has stayed with me several times."

"But he and Mr. Hedley had not met before?"

"No. My cousin, Mr. Hedley, arrived here only yesterday afternoon, and has been in England no more than a fortnight."

"At what hour did they first meet?"

"At tea, about half-past four, when Mr. Vedder came in from fishing."

"Was there any disagreement between them at that time?"

"None. I simply introduced them. Miles—that is Mr. Hedley, had tea, and Mr. Vedder had a whisky and soda. They hardly spoke."

"What happened between tea and dinner?"

"Mr. Hedley went fishing. He returned just in time to dress for dinner."

"You all three met at dinner?"

"We met in the hall before dinner was announced."

"Was there any discussion then between Mr. Hedley and Mr. Vedder?"

Maurice looked suddenly uncomfortable. "There was," he answered. "Mr. Hedley had caught some trout, and Mr. Vedder suggested that he had taken them with a worm. Mr. Hedley was annoyed, but—" he paused—"after all, that was nothing."

THE Coroner's sharp little eyes were fixed on Maurice. "Oh, so there was some disagreement between the two, previous to the game of cards."

"It was a mere nothing," said Maurice doggedly.

"Thank you," said Mr. Shenstone. "That will do, Mr. Tavener. I will now call your butler, Mr. Jarman."

Jarman was one of those thick-set, rather pompous men, an excellent butler, but with a great love of the sound of his own voice. He gave formal evidence of Miles's arrival, then the Coroner began asking questions. "Mr. Jarman, where were you just before dinner was announced?"

"In the dining room, sir, putting the last touches to the table."

"Was the door open or closed?"

"Just ajar."

"Then you were able to hear what was going on in the hall?"

"I could not help hearing it, sir."

"Can you repeat the conversation?"

Miles saw Maurice try to catch his butler's eye, but Jarman's were fixed on the Coroner's face. "I remember the gist of it, sir. Mr. Tavener was chaffing Mr. Vedder about his ill-success at fishing. 'Here's one man who can catch fish if you can't?' he said. Mr. Vedder then asked Mr. Hedley what he had caught the trout with—whether it was a worm, and Mr. Hedley was annoyed, and said something about Mr. Vedder having a nasty mind. Mr. Vedder asked what he meant by that, and Mr. Hedley answered 'Just what I said. It take's a nasty mind to think of such a thing.' I don't know just what happened then, but I heard Mr. Tavener say sharply: 'Shut up James, and you dry up, too, Miles.'"

By this time all the jurymen were craning forward listening with an eagerness which none of them shown hitherto. The reporters were scribbling rapidly. As for Shenstone, his face had gone hard and sharp.

"So Mr. Tavener had to interfere between them?" he asked.

"It seemed so, sir," agreed Jarman, "but, of course, I couldn't see what happened."

"So there was a quarrel before dinner," said Shenstone slowly. "A pretty violent quarrel, too. It would seem that Mr. Hedley and the deceased man nearly came to blows."

"But what was it all about, sir?" questioned one of the jurymen in a puzzled tone. "Why shouldn't Mr. Hedley catch fish with a worm?"

A dry smile crossed the Coroner's face. "It is not supposed to be sportsmanlike to catch trout with a worm, Mr. Tuck," he explained. "Now I will take the doctor's evidence," he continued, "and after that the jury will retire and consider their verdict."

Maurice's face was like thunder and Miles could fancy what he would say to Jarman when he next had chance, but the damage was done, and it was too late for repentance. He was right about the damage, for the jury, after a brief consultation, gave their verdict that the deceased had met his death at the hands of Miles Hedley, but without malice aforethought.

"Which," said the Coroner, in his dry way, "is equivalent to a verdict of manslaughter."

Miles's heart dropped a beat. What would happen now? He had not long to wait for here was Tooker's hand on his shoulder.

"Are you arresting me?" asked Miles in a low voice.

"I have to, Mr. Hedley."

"Can't I have bail?"

"Not in a case like this. But luckily the Assizes come on within a fortnight, and"—with a smile—"we shall try to make you comfortable."

That night Miles slept in Exeter gaol. He was treated as a first-class prisoner, allowed to wear his own clothes, to receive visitors, and to write letters. His first letter was to Bartlett, his solicitor, asking him to secure the best counsel available; his first visitor was Maurice. Maurice was looking anything but fit. His cheeks were blotchy, his eyes bloodshot. Miles saw at once that he had been drinking a great deal more than was good for him.

"That fool, Jarman!" he burst out. "Who'd have dreamed that he'd been listening?"

"We ought to have thought of it," replied Miles calmly.

"Even if he had, he ought to have known better than to talk. He'll think twice before he does anything of the kind again," Maurice went on viciously. "The very first thing I did after the house was cleared was to sack him without a character." Miles gave a sharp exclamation.

"Good God, Maurice, you weren't such a fool as that!"

"What do you mean?" demanded Maurice, in a startled tone.

"Mean? Do you forget that he is the principal witness for the prosecution? Now you can take your oath he will make the case as black as ever he can against me."

The change in Maurice's expression would have been laughable if Miles had felt in the least like laughing.

"I—I never thought of that," he gasped. "I—I'll try to put it right."

"Don't try to bribe him," warned Miles firmly. "That would put the lid on it."

Maurice went away very subdued, but once more the damage was beyond repair. Jarman had got his back up thoroughly. In a very starchy letter he refused to come back to Foxenholt or to have anything further to do with Maurice. Maurice sent the man's letter to Miles, who smiled wryly when he had read it. "Seems to me I'm in the soup," he said to himself with a smile. Yet neither he nor Maurice had the least idea of the tangled nature of the coil in which they had wrapped themselves.

MAURICE took the stopper out of the whiskey decanter and started to pour out another drink, then checked himself abruptly.

"No," he said angrily. "I've had enough. After all there's nothing to worry about, now that Vedder's out of the way. And I can't help what happens to Miles. I've paid all he asked, and it's up to him to stand the racket."

He put the stopper back in the decanter, and picked up a newspaper. But he could not read and presently dropped it and sat, staring out of the open window. It was a heavenly summer night, and the warm air was rich with the scent of stocks blooming in the border below. From the valley beneath the garden came the pleasant murmur of the little river splashing among its boulders. A brown owl hooted in the distance.

Maurice lay back in his chair. "I wish this infernal trial was over. When it is I'll go abroad. I'm fed up with England. As for this place, I'll sell it. I can't live here after what's happened." He thought of Vedder again, and shivered, then grew angry again. "He got what was coming to him," he said aloud. "I'm well out of it."

"I should say you are." The voice startled Maurice so badly, that for the moment he could hardly breathe. He sat rigid with eyes fixed on the man who had suddenly appeared outside the window. The sill was low, and the light of the electric lamp on the table behind Maurice showed the visitor plainly. Not a burglar nor a tramp, but a man well dressed in excellently cut brown tweeds and wearing a brown felt hat. His shirt and soft collar were blue, his tie was a foulard that matched the suit, a dark silk handkerchief showed in his breast pocket, and a handsome signet ring was on the little finger of the strong brown hand which rested on the sill. He wore an eye-glass in his right eye.

All these details impressed themselves on Maurice's subconscious self, but more than anything else the man's face. Good looking in a hard style, with dark skin, dark, cynical eyes and well shaped features, but what struck Maurice more than anything else was the man's entirely self-contained and self-sufficient manner.

"I must apologise," said the newcomer. "I didn't mean to startle you. I came to call but it took longer to walk from the station than I had expected, and when I rang I got no reply. So, seeing your light, I walked round to the window, and was just in time to hear the remark which I answered." The length of this speech gave Maurice time to pull himself together, but he was still frightened and therefore angry.

"Who are you?" he demanded harshly.

"My name is Cullen—Clement Cullen. You must have heard of me from our mutual friend, Vedder." Mention of Vedder gave Maurice a fresh scare.

"No," he said, "Vedder never mentioned you."

"Careless of him," said Cullen cooly. "And now, unfortunately, he is no longer here to introduce me. May I come in?" Maurice hesitated, but Cullen took silence for consent, and, swinging one leg over the sill, stepped lightly into the room. Now that he was in the full light Maurice saw that he was rather a small man, yet amazingly compact and well built, and in every way intensely sure of himself. He dropped into a chair opposite Maurice, crossed one leg over the other, showing neat brown shoes and silk socks, then took out a thin gold cigarette case, selected a cigarette and lit it. He did everything with the same leisurely air of being very much at his ease.

Maurice roused to his duties as host. "Have a drink?" he suggested, pushing the decanter across. Cullen helped himself, filling up with soda and lifted his glass.

"Here's to our better acquaintance," he said, and drank. Maurice who was racking his brain to imagine what his midnight visitor was after, waited for Cullen to speak, but the man sat silent, smoking and watching Maurice with a cynical twinkle in his dark, deep-set eyes until Maurice was driven to speak.

"So you are a friend of poor Vedder?" he asked at last.

"Next to you, probably his best friend," Cullen answered, and Maurice felt even more uncomfortable than before.

"Curious, he never spoke of you," he retorted.

"Jim was never one to waste words," replied Cullen calmly. "Money was the only thing he wasted." He paused. "I don't wonder you think you are well out of it, Mr. Tavener." Maurice's heart gave a thump that made him feel as though he were choking, but he made a great effort to pull himself together.

"He certainly won a lot of money from me at one time and another," he said, with a poor attempt at a smile.

"So you are not wasting many regrets on his untimely end?" suggested Cullen softly. "In fact, as you said, you are well out of it." Maurice started up.

"I'll thank you not to twist my remarks in that fashion. I was not referring to Vedder." A mocking smile crossed Cullen's thin lips.

"My mistake. Then I presume it was your cousin of whom you were speaking." If Cullen's object had been to make Maurice lose his temper he was perfectly successful, for Maurice went right up in the air.

"You can keep your presumptions to yourself, you infernal eavesdropper," he snarled. "And the sooner you get out of this the better." Cullen smiled again.

"Come now," he said, in the sort of tone you might use to a fractious child. "There's no need to get cross because I try to pull your leg. Light up and let's get down to business." Maurice glared at him.

"I have no business to talk with you."

"You have. Indeed you have. You see I happen to be Vedder's executor." There was something so significant in the man's words and manner that Maurice felt a cold chill run down his spine. But he tried to keep a hold on himself.

"Then let's hear what you've got to say," he growled. "But if you are executor why weren't you at the inquest?" Cullen showed no resentment at Maurice's rudeness.

"I was waiting to see which way the cat jumped," he remarked softly.

Maurice stared.

"What the deuce are you talking about?"

"Which way the verdict went," explained Cullen patiently.

"Which way could it go, except the way it did?" demanded Maurice.

"The truth might have come out," suggested Cullen gently.

MAURICE stiffened. "The truth." he repeated. "Speak plainly, curse you, and don't go beating about the bush. What are you trying to say?"

"Merely that your story was a bit thin," Cullen answered. "And that I would like to hear the truth of the business." Maurice felt the blood leave his face, but he struggled desperately to keep calm.

"You're crazy," he retorted with a sneer. "You read the evidence at the inquest." Cullen shook his head slowly.

"You're not going to tell me that Hedley did the killing, Tavener, for if you do I shall tell you straight I don't believe you."

Now that the words were out Maurice had the feeling that all the time he had expected this, yet that did not make the hearing any easier. The truth came upon him with a rush. This man knew his secret—that ugly secret on which Vedder had traded for so long—and meant to blackmail him just as Vedder had done. As this conviction forced itself upon him a fury of rage possessed him. In a flash he was on his feet and his big hands shot out, grasping at Cullen's throat.

Quick as he was, Cullen was quicker. With one motion he was out of his chair and behind it and Maurice gasped as he found himself looking straight into the wicked muzzle of an automatic pistol.

"You think you might as well hang for two sheep as one lamb, eh, Tavener?" remarked Cullen. His voice was as level as ever and his eyeglass remained firmly fixed in his right eye. He showed absolutely no sign of excitement. He smiled again, and how Maurice hated that thin-lipped smile! There was a hint of contempt in it which maddened him.

"Well," went on Cullen with a slight drawl. "You've told me all I wanted to know. I never believed for a minute that Hedley killed Jim, but I wanted to be sure." He paused, but his pistol did not waver the smallest fraction of an inch. "Now that I am sure, and now that you know you can't kill me, too, suppose you sit down again." Maurice sat down. He was breathing hard and his face was the colour of lead. Cullen moved his own chair so that it was opposite Maurice's and seated himself comfortably, but he still held the pistol on his lap.

"Better take a drink," he suggested. "You look as if you needed it." Maurice's hands shook so that he spilled the whisky, but he drank greedily and his face became a more normal colour. Cullen watched him with interest.

"How did you do it?" he asked. "I wouldn't have placed you as a killer."

"It was an accident," said Maurice hoarsely. "We quarrelled over cards. He accused me of cheating. I hit him, and he fell against the fender and broke his neck." Cullen nodded.

"And then you bribed Hedley to take the blame. What did you give him?"

"Ten thousand," snarled Maurice. Cullen's eyebrows lifted slightly.

"He socked you good and proper," he remarked. "Wanted it for the Bolivia business, I suppose?" Maurice started.

"What do you know about the Bolivia business?" he demanded. Cullen smiled.

"If you'd known as much as I know, Tavener, you wouldn't have turned down Hedley's offer."

"You mean it's as good as he says?"

"Better," was the curt reply. For some moments the silence was broken only by the ticking of the clock and the sound of the river floating up from the valley. Maurice was trying to collect his scattered thoughts, but was so upset that he found it difficult to think at all clearly. The only thing that was clear was that Cullen was completely master of the situation. Though he had not said it in so many words, Maurice did not doubt that the man shared Vedder's knowledge of his secret—a very nasty secret—and that he meant to make every use of it. It seemed that he would be a worse taskmaster than Vedder himself. Maurice racked his brain for any way out, but could see none.

Cullen pinched out his cigarette and flung the stub out of the window, then turned his eyes upon Maurice. There was a mocking light in them.

"Wishing, that you could get rid of me, eh, Tavener?" he remarked, reading Maurice's thoughts so accurately that Maurice could not repress a start. Cullen smiled again, but the smile was only on his lips.

"Don't look so worried. I'm going to put you in the way of doing it." He paused and Maurice stared at him. He could not imagine what was coming.

"I want that mine," said Cullen slowly.

"Want the mine," repeated Maurice. "You're crazy. Hedley has already sent the money to his partner, and Drake—"

"I'm not worrying about Drake," cut in Cullen. "So long as Hedley is out of the way I can handle Drake. And once Sanchez and I have got the show into our own hands we shan't need to bother you any more." He paused again and fixed his eyes on Maurice. "But I have to be sure that Hedley won't come butting in."

"You can't be sure," Maurice told him. "I've told you already the whole thing was an accident. His lawyer says it's all odds he'll get off."

"He mustn't get off. I want to see him sent up for two years at least. If he gets a two years' sentence it means they'll keep him inside for 18 months. That's the shortest time Sanchez and I need to get hold of the mine at Pasarpa."

"I can't help you," retorted Maurice. "I'm not the judge."

"No," said the other slowly. "You're not the judge, but you're a witness. Now listen to one and I'll tell you how the case can be swung against Hedley." Leaning forward a little but still dangling the pistol in his strong hands, he began to talk. He spoke in a perfectly level voice without showing the slightest sign of emotion, and Maurice listened. Maurice was not particularly scrupulous, yet Cullen's plan was so cold-blooded, so utterly callous that every decent instinct left in his listener rose and protested.

"It's simple as pie." Cullen ended. "No risk to anyone, yet it damns Hedley's case all ends up." Maurice stiffened.

"Simple, you say, simply damnable. You can count me out of any such plan, Cullen. Cullen shrugged slightly. Nothing in his looks showed that Maurice's decision mattered to him one way or the other.

"Just as you like," he said. "If you prefer to pay that's your look out. Only I shall want more than Vedder, and there's Gomez, too. He'll need his bit." Maurice's big fists tightened. He longed to hurl himself this mocking brute, but that ominous pistol checked him. "I'll take a thousand on account," Cullen went on.

"You'll take yourself off this minute." roared Maurice in a fury, but Cullen merely looked at him with a sort of pitying contempt.

"Blow off steam all you like," he said, "but for your own sake you'd better not make too much row about it, or you'll rouse your servants." He took another cigarette from his case, tapped it on his finger nail, and lit it. It may have been that he was playing to the gallery, but Maurice did not think so. He felt that he was up against a man cruel and remorseless as Fate, and as was only natural the stronger won. Quite suddenly Maurice collapsed. "I'll do it," he said with a groan. "It's—it's rotten, but I can't help myself."

MILES had a queer feeling of unreality as he stood in the dock in the gloomy court at Exeter Castle. It was a dull day, and the only spot of colour in the whole crowded place was the crimson robe of Mr. Justice Colyton. A rather grim-looking old gentleman, Miles thought, and then his glance strayed to the face of his counsel. Bartlett had briefed Stark, one of the best of criminal counsel, but only two days earlier Stark had gone down with flu and Miles was not greatly impressed with the look of his junior, Alan Beddoes.

Yet Miles was not particularly anxious, for Bartlett had assured him that the verdict could not possibly go against him. Indeed, the solicitor had held out hope that the Grand Jury would throw out the case. A Grand Jury, he had explained, generally throw out one case simply in order to justify their existence, and Miles seemed the most likely on the list. But on this particular occasion the Grand Jury had chosen another case to throw out, and had returned a true bill in that of the Crown against Hedley.

The witnesses were, of course, the same as at the inquest, and the first to be called was Dr. Helmore, who gave formal evidence as to the cause of Vedder s death, and stated that the breaking of his neck had undoubtedly been caused by the fall, not the blow. He admitted, however, that the blow must have been a very heavy one. Then Maurice was called, and came forward. He looked terribly shaky when he got up into the box, and he answered the first question in so low a voice that the judge ordered him, rather sharply, to speak up. Walmsley, counsel for the prosecution, examined him pretty sharply, and made a point of the fact that Vedder had been acting in good faith, when he had made his accusation of cheating. He also questioned Maurice closely as to the details of the struggle. Maurice got so hot and confused that Miles began to wonder, rather grimly, if he was going to break down completely, and own up to the truth. But somehow he survived the ordeal and got safely out of the box. Miles put his agitation down to the fact that he knew he was lying, and thought no more of it. The one thing that puzzled him was the way in which Maurice avoided looking in his—Miles's direction. Time and again Miles tried to catch his eye, but in vain, and when his evidence was finished Miles was surprised to see his cousin leave the Court.

The next, indeed, the only other witness, was Jarman. Jarman was most correctly garbed in dark blue serge with a stiff white collar, and carried a pair of yellow gloves. He looked stouter and more pompous than ever. He was clearly conscious of the fact that he had the centre of the stage, and inclined to make the most of it. Miles watched him intently, for he realised that on his evidence, much more than Maurice's, the verdict would depend. Walmsley made him repeat his account of the quarrel he had overheard between Miles and Vedder over the matter of the trout.

"The quarrel, as far as you could hear, was a sharp one?" said Walmsley.

"Quite sharp, sir. Mr. Tavener had to interfere between them."

"When the three gentlemen came in to dinner, were they on good terms again?"

"Far from it," replied Jarman. "Mr. Vedder was scowling, Mr. Hedley was silent, and Mr. Tavener was uneasy."

"And after dinner what happened?"

"Mr. Hedley went out on the verandah. He and Mr. Vedder had not said a word to one another all dinner time."

"Then it seemed to you that there was still bad blood between them?"

"That was my impression, sir."

Miles's counsel opened his mouth as if to protest, but seemed to think better of it. Miles, himself, glanced at the jury and saw that they were listening eagerly. He felt that matters were not going any too well, but he was by no means prepared for what was to follow.

"I understand, Mr. Jarman," said Walmsley, "that you are no longer in the service of Mr. Tavener?"

"That is correct, sir." Jarman's heavy voice was suddenly bitter. "I was discharged."

"Did Mr. Tavener give any reason for discharging you?"

"Yes, sir. He was angry with me for mentioning at the inquest the quarrel about which I have just told you." The judge leaned forward and a rustle from the jury box was evidence of the interest of its occupants.

"But this is intimidation!" said Walmsley, in his deep-throated voice.

"There's more than that," said Jarman harshly, and putting his hand into the inner pocket of his coat, drew out an envelope.

"This reached me this morning. I'd like you to read what it says, sir." A police officer passed the envelope to Walmsley who took out the contents and exhibited first a bundle of Treasury notes, then a sheet of plain paper on which were some lines of typewritten matter. Walmsley counted the notes.

"Twenty-five pounds," he said. "Is that correct, Mr. Jarman?"

"That's it, sir, and now please read what's written."

The court had suddenly become amazingly still. Everyone was on the tiptoe of excitement as Walmsley addressed the judge.

"Shall I read this, my lord, or will you prefer to do so?"

"Read it, please, Mr. Walmsley," said the judge, and Walmsley bowed and obeyed.

"Enclosed are 25 pounds. If you have the good sense to keep your mouth shut about you know what, another 25 will reach you from the same source after the acquittal of Mr. Miles Hedley. From one who wishes well to both you and Mr. Hedley." Walmsley paused and looked at the judge.

"There's no address, my lord, no date, no signature." Mr. Justice Colyton's face, stern at any time, took on an expression that made it look as if cast in steel.

"I have never heard a more scandalous attempt to pervert the course of justice," he declared in a voice that matched his expression. "Every effort must be made to arrest and punish the person who has attempted to bribe this witness. And I will add here and now that Mr. Jarman has taken a very proper course in handing the letter to the court." Jarman beamed. You could almost imagine he was purring. But Miles, glancing at the dismayed face of Beddoes, felt his heart sink like lead. He realised instantly the effect these disclosures must have upon the jury, and how hopelessly they would prejudice the case against him.

BEDDOES'S speech for the defence was not his brightest effort. He was young and nervous. Jarman's evidence had upset him, and he did not speak like a counsel convinced of his client's innocence. Miles could see that the jury were not impressed, and the look on Bartlett's face did not improve his spirits, for the solicitor was clearly unhappy.

Beddoes talked, of course, of the provocation his client had received at the hands of Vedder, but he talked all round his point instead of going straight to it. His speech was much too long, and before it was finished the jury were clearly getting impatient. As for Mr. Justice Colyton, he sat with lips tightly compressed and an expression on his face which could only be described as grim. The one person in the court who looked thoroughly pleased was Jarman, and Miles could gladly have punched the complacent smile off his smug face, if that had been in any way possible.

Miles was thankful when Beddoes at last sat down. It was then Walmsley's turn to have the last word, but it was pretty good proof of his opinion of things that he contented himself with a few sarcastic sentences and was not on his feet for more than five minutes. It was not, however, until Colyton began to sum up that Miles realised how thoroughly Jarman had upset his apple cart. The judge seemed to be under the impression that Miles was responsible for the attempt to corrupt the court and treated him accordingly.

"Here," he said, "is a man who though English by birth, has lived for years in a country where law and order as we know it, hardly exist, and where human life is held with deplorable cheapness. The evidence goes to show that a serious quarrel took place between the prisoner and the deceased over a comparatively trivial matter, and that this happened some hours before the final tragedy. Maurice Tavener is the prisoner's cousin and may therefore be considered to have some bias in his favour, yet his evidence proves that the deceased was clearly under the impression that there was something wrong about the particular hand of cards over which the final quarrel took place. Nor does he deny that the accused struck Vedder with considerable violence." He paused a moment, sipped his glass of water, then fixed his eyes on Miles and went on again.

"The bare-faced attempt to corrupt the only witness for the prosecution, the butler, Jarman, seems to prove that friends of the accused greatly feared evidence. As I have already said, this abominable, but fortunately unsuccessful attempt, to interfere with the course of justice will be strictly inquired into and the offender, whoever he is, will be severely punished." He paused and his stern glance crossed to the jury box.

"Gentlemen of the jury, it is not possible to say that there was any premeditation in this killing, and it is your duty to remember that, according to the evidence of Maurice Tavener. Vedder struck the first blow. Yet a life has been sacrificed—and it may seem to you—wantonly sacrificed. You will now retire and consider your verdict." As the jury trooped out Miles looked again at Bartlett and saw a look of absolute consternation on his face.

"That's put the hat on it," he said to himself. "I'm going to earn Maurice's ten thousand." Then the warders took him below.

He had not long to wait, for in less than a quarter of an hour, he was summoned back to the dock, to listen to the verdict.

The foreman of the jury, a long, thin man with a skinny neck and a ready-made black tie, cleared his throat and announced that the jury were unanimous in finding Miles Hedley guilty of manslaughter.

Miles saw the judge nod. "A very correct verdict," he said in his cold, clear voice. "And under the circumstances I consider that the cause of justice will be served by a sentence which will make the prisoner realise that here in England he cannot act as in the wilds of South America. Miles Hedley, you will serve seven years' penal servitude."

Miles felt himself go rigid, his hands tightened on the rail of the dock. He wanted to speak—to protest against the injustice of such a savage sentence, but there was no time. Before he could find his voice the hand of his warder fell upon his arm and he found himself once more descending the stairs leading down to the cells below. A moment later the heavy door closed and he was left to himself.

He sat quite still, in a curiously dazed state. Seven years' penal servitude, and at the very worst he had not believed it possible that he would get more than twelve months' imprisonment. Seven years—no, not that much, for by perfect conduct he might win a remission of one-third of his sentence, yet even so, more than five years of his life were to be blotted out. He would spend them in a convict prison, mixing with the very dregs of humanity, a cypher, ordered here and there by his keepers. As the full realisation of his terrible plight forced itself upon him his head dropped forward and he buried his face in his hands.

BOLIVIA is a country of violent contrasts, for while part of it lies at such a height that its climate is absolutely arctic, its lower portions are purely tropical. In Pedral, the home town of Señor Juan Sanchez, which lies on the Eastern slopes of the Andes, at a height of about four thousand feet, the afternoon was decidedly warm and Sanchez himself, who had recently finished a large meal of stewed goat flesh, Lima beans and frijoles, was seated in a cane chair with his stout legs propped on an up-ended packing-case, smoking an evil-looking black cigar.

His plump hands were folded across his comfortable stomach, and the lids were beginning to close over his round black eyes when steps on the verandah outside aroused him. Not the shuffling steps of his fat wife, but quick, firm steps, which made him sit up sharply. A rap on the door, then without waiting for an answer, the newcomer was inside the large untidy room.

"You, Señor Cullen!" exclaimed Sanchez, scrambling to his feet in such a hurry that the packing-case fell over with a crash. "Bios, how you startled me! I believed you to be seven thousand miles away, in England."

"So I was less than a month ago," replied Cullen coolly. In spite of the heat and the long journey, Cullen was smart as usual. He wore a suit of pale grey flannels with tan shoes and a white felt hat, and his face and hair looked as if he had just left the barber's shop. His gold-rimmed eyeglass dangled at the end of a wide black riband.

"A month," repeated Sanchez, pushing a chair forward. "Caramba, but you must have travelled quickly."

"I did," drawled Cullen, as he seated himself, and lighted a cigarette. "Mail boat to Buenos Ayres, then train across to Africa and so over the mountains to Potosi. I rather think I have beaten the record. I hope I have at any rate."

"But what was the reason of such haste, Señor?"

"I was trying to beat the post," was the reply. "Tell me, has the European mail been delivered here during the past 48 hours?"

"No, Señor, but it is expected soon."

"I don't care how soon it's expected so long as it is not here yet," said Cullen, as he got up. "Have you two good mules, Sanchez?"

"I can procure them speedily," was the reply.

"Then do it. I'll explain as we ride."

Sanchez stumped out, shouting as he went, to Dolores, his fat wife, to bring a cool drink for the English señor, and ten minutes later returned with the mules. Cullen swung easily to the saddle. Sanchez scrambled panting to the back of his mule, and they started up a rough, narrow road which led into the mountains above the town.

"Pasarpa—that's where we are going," Cullen told Sanchez, and briefly explained the situation. "Hedley's safe in quod—prison," he said.

"Hedley in prison!" cried Sanchez in great excitement. "But what fortune!"

"No fortune about it," retorted the other. "I put him there. And don't interrupt until I have finished. The trouble is that Hedley got money for the mine before he was jugged, and sent the draft straight out to Drake. Once Drake gets the cash there is, of course, no chance of his selling, but it struck me that, if I could get here before Hedley's letter reached him, tell him that Hedley had failed, and make him a fair offer, he'd probably part."

"But, of course, you are right." Sanchez fairly gabbled in his eagerness. "If you have the money he will sell of a surety."

"I've got the money, all right," said Cullen drily. "I'm prepared to offer five thousand pounds, English."

"It is a great sum," said Sanchez with a sort of awe.

"A flea-bite compared with what we shall get out of the mine, once it's in our hands. Push on that beast of yours. I don't want to run any risks."

Sanchez stuck in his long-rowelled spurs and the mules broke into a canter. As they rounded the next corner Cullen's beast, which was leading, suddenly stopped and stood trembling.

"What the devil—?" began Cullen, then as a deep, droning sound came echoing down the mountain side he looked quickly upwards. "An aeroplane!" he exclaimed. "And the first I ever saw in this country? Whose is it, Sanchez?"

"An American," said Sanchez sullenly. "Captain Scorson he is called." Cullen glanced shrewdly at his stout companion.

"You don't seem to like the gentleman, Sanchez."

Sanchez spat. "He is no gentleman," he retorted. "He is an American pig."

"What's he been doing to you?" questioned Cullen. "He have insulted me in my own office," shrilled Sanchez. His English, usually quite good, suffered when he grew excited. A ghost of a smile crossed Cullen's thin lips.

"But what's he doing with that 'plane?" he inquired.

"He say he use it for the prospecting," was the answer, "but I think he is a spy."

Cullen said no more but watched the machine till it vanished, like a silver bird, over the mountain top. Then he spurred his mule forward. They crossed the ridge and came down into a small valley. On the slope opposite was the dark opening of a tunnel and below it a mass of rubble. On a ledge to the left stood a neat, little house built of wood. Roses bloomed on the posts of the verandah, and there were beds of stocks and other English flowers growing in front. Seen against the barren hill front, the colour and brightness of the little place was almost startling.

The two rode on rapidly, and as they pulled up at the gate of the bungalow a man came out of the front door. John Drake was of middle age and middle height. He was of a type they call stuggy down in Devonshire, and the muscles of his bare arms were gnarled and powerful. His eyes which showed startlingly blue in a face darkened by years of tropical sun and storm, widened a little at sight of his visitors, but there was no sign of pleasure on his face as he came slowly forward to meet them.

Sanchez introduced Cullen, and Drake asked them in and offered drinks.

"Wonderful what you've done here, Mr. Drake," said Cullen. "It might be a bit of Devonshire."

"You know Devonshire?" asked Drake.

"I left it barely a month ago," smiled Cullen. An eager look crossed John Drake's face. Like all Devonshire men, he loved his country, but all he said was: "You've travelled quickly, Mr. Cullen."

"Yes, I was in a hurry," Cullen agreed. "I'm going to be quite frank, Mr. Drake. While I was in Devonshire I met your partner, Mr. Hedley. He was staying with his cousin, Maurice Tavener, who is a friend of mine. In course of conversation he mentioned that he had been trying to raise money to develop your mine, but had failed to do so. He said that there was nothing left but to sell the property. Details he gave made me believe the mine would be worth floating as a company, and since that is my business, I came straight out with the idea of looking it over and, if it is as good as he says, making you an offer." John Drake's lips tightened.

"Then Tavener has turned him down?"

Cullen nodded. "Maurice has got so much money already, I suppose he does not care to make any more," he said. "Here is a note he wrote me telling me that he did not intend to invest."

Drake read it and handed it back. "Then there is nothing for it but to sell," he said heavily. "But let me tell you, Mr. Cullen, that I do not mean to let it go for a song. Señor Sanchez has offered two thousand pounds, but such a price is absurd. There is a fortune here in this valley for anyone with capital."

"May I see the mine?" asked Cullen, and Drake nodded and led the way. The mouth of the adit was only a few hundred yards from the house. Arrived there, Drake lighted a lantern and led the way into the tunnel, and the others followed. No work was going on, for Drake's money was exhausted and he could not pay for labour. Cullen's examination was brief and business-like, and when it was finished the three returned to the house.

"There is certainly gold there," said Cullen, "but the rock is difficult and a considerable capital will be necessary to develop the mine. However, I am willing to take the risk, and I offer you four thousand pounds, Mr. Drake, for all your rights."

Drake shook his head. "Not enough," he said curtly. Cullen looked at him.

"Five then," he said quietly, "and that is my limit."

Drake hesitated. He realised that Cullen meant what he said and five thousand was enough to give him and Stella and Miles a fresh start. But there was Miles himself to be considered.

"You must wait until the mail arrives from England, Mr. Cullen," he said. "I must know definitely from Hedley to sell." Cullen shook his head.

"I can't wait Mr. Drake. I have another proposition to see at Cochabamba and shall leave here to-night. I must have your decision at once."

A worried look crossed Drake's face. No one knew better than he the difficulty of selling a gold mine in so remote a place as this, and if he refused Cullen's offer he might never get another so good. His lips opened, he was on the point of accepting when the door was flung open and a girl stepped lightly in. She was glowing with excitement. "Daddy, it's come!" she cried as she waved a letter. Then she saw Cullen and stopped abruptly.

"A LETTER from Miles!" exclaimed her father, then he remembered his manners.

"My daughter, Mr. Cullen." Cullen bowed, so did Sanchez, only more deeply, and Stella nodded. Her eyes were as blue as her father's and in some miraculous way she had kept her complexion of roses and cream. Only a freckle or two showed the effect of the southern sun. Her hair was brown with a touch of gold and with her straight nose, firm chin, and level, almost boyish, gaze, she made a most attractive picture.

"What does Miles say?" asked her father eagerly.

"He's got the money." Stella told him. "We're all right, Daddy. No need to worry any more." Drake turned to Cullen.

"You said he had failed."

"So he had up to the time I met him." Whatever Cullen felt of anger or disappointment, not a muscle of his face betrayed it. He smiled and went on. "Of course, I am disappointed, but not too much so, for I dare say the Cochabamba prospect may prove equally suitable for my purpose. Anyhow, I congratulate you on Mr. Hedley's success." He turned to Stella. "I take it, then, that the English mail is in?"

"It has not reached Pedral yet," Stella answered. "I rode down to the railhead at San Juan yesterday. It came in this morning and Captain Scorson brought me back in his 'plane."

Cullen still smiled. "Then I will leave you to your letter," he said politely. "Come, Sanchez." Drake went out with them and saw them off, and they rode in silence until a bend of the trail hid the bungalow, then Cullen spoke.

"Missed it by a minute," he remarked drily. "Another sixty seconds and I'd have had Drake's signature to the bill of sale." Sanchez's fat face was a picture of misery.

"It is terrible," he moaned. Cullen's lip curled.

"No need to make such a song about it. It's only a matter of time. I'll have that mine yet, and"—he grinned evilly—"that blue-eyed chit as well." Sanchez refused to be comforted.

"How can you have the mine now that Drake has the money, for now he will not sell at any price." Cullen grinned again.

"There are more ways of killing a cat than choking it. Land titles are none too sound in this country, and the Alcade at San Juan is my very good friend. A couple of thousand dollars in the right hands, and—" he chuckled again. Then he pulled up his mule, "There's the 'plane," he said, pointing to an open space at the bottom of the valley, where the machine lay. "And Scorson with it. Come on down. Sanchez. I want to have a look at this Yankee friend of yours."

"He is no friend of mine," protested Sanchez. "I do not wish to see him." But Cullen was already riding down the slope and the fat man had to follow.

Jay Scorson, busy cleaning his sparking plugs, looked up as the pair approached. He was tall, lean, sandy-haired, and entirely competent. There was a look of amused contempt in his keen grey eyes as they rested on Sanchez.

"Good morning, sir," said Cullen. "You'll forgive my curiosity, but this is the first 'plane I've seen in these parts." Scorson turned a slow glance on Cullen.

"That so?" he asked quietly. For once Cullen felt an odd and unusual touch of discomfort, but he was accustomed to bluffing it out.

"My name is Cullen," he said. "I am a mining engineer and I have been talking to Mr. Drake, with the idea of purchasing an interest in his prospect here. He won't sell, so I wish to get back to railhead as soon as possible. I was wondering if you were going that way."

Scorson paused before replying, and Cullen wondered irritably what the airman had in his mind. At last Scorson spoke. "I shall be pleased to give you a lift, I am going right back as soon as I can put in these plugs." Cullen thanked him, then turned to Sanchez. "You take back the mules, Sanchez, and I'll let you know about the Cochabamba prospect as soon as I've seen it. Adios."

Sanchez mumbled something and went. It was plain he was only too glad to get away. Scorson replaced his last plug then took a packet from the 'plane. "Guess you'd better wear a 'chute," he said. "Know how to work it?"