RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old travel poster (ca. 1930)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old travel poster (ca. 1930)

"The Lone Hand," F. Warne & Co., London & New York, 1934

"The Lone Hand," F. Warne & Co., London & New York, 1934

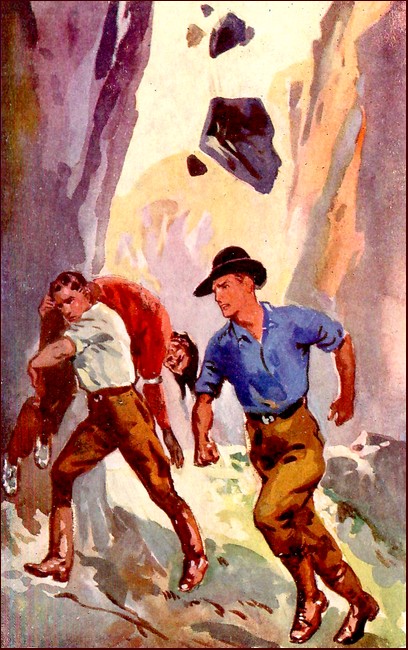

Rob swung the wizened figure of the Indian over his shoulder.

ROB MACLAINE stopped at the door of the barely furnished dining-room in the little South American hotel and gazed in dismay at his father; for Angus Maclaine, who sat by his untasted breakfast, with a letter before him, looked ten years older than when he and his son had parted on the evening before. His grim face was carved with deep lines, actually his hair seemed to have gone greyer.

"What's the matter?" Rob asked sharply. "What's wrong, dad? You've had bad news."

Angus Maclaine looked up from his letter. His weather-beaten face looked like granite.

"Aye, the news is bad," he answered curtly. "I will have to go up the line at once."

A dozen questions trembled on Rob's tongue, but he did not voice them. He had seen nothing of his father for the past four years, during which time he had been at school in Scotland. The two were almost strangers. Somehow he felt that he had best keep silence, so he sat down quietly to his corn cakes and coffee.

Rob was barely sixteen but with his broad shoulders, level blue eyes, firm lips and strong chin looked at least two years older. He had only just arrived in the South American State of San Lucar to join his father who was contractor for the new railway crossing the mountains between the towns of Peralta and Orono.

After a hurried breakfast the two set out for the station, and within less than half an hour were travelling in a train composed of one coach and a small locomotive, up the new line. The driver was Tex Rayson, a smart young American.

Mr. Maclaine sat silent and Rob, seeing that he did not wish to speak, went out on to the railed platform at the back of the coach.

The sight was marvellous. The new line went curving up through the foothills of a range of giant mountains, the snow-capped peaks of which glistened like sugar loaves against the intense blue of the Western sky. Everything was new to Rob, the vast bare slopes, the deep canyons with their roaring torrents like threads of wool in the depths, the big pepper plantations, the flocks of brown sheep, the natives, with their comical hats, driving trains of pack mules. For the time he almost forgot his father's troubles in the interest of it all.

The line being brand new it was impossible to go fast. The speed rarely exceeded twenty miles an hour and did not average more than fifteen. Midday found them running down into a broad valley at the bottom of which stood the small town of Magdalena.

The weather had changed. Huge thunder clouds darkened the sky, and up in the mountains it was plain that a furious storm was raging. Then all in a moment the rain was upon them, falling in sheets that blotted out everything beyond a radius of a few yards, and driving Rob back into the carriage.

Next minute he noticed that the train was moving faster than it yet had. The speed increased; Mr. Maclaine jumped up.

"What's Rayson doing?" he demanded sharply. "It's not safe to go at this pace."

"I believe she's running away," said Rob sharply.

His father leaned out of the window.

"Rayson! Rayson!" he roared at the top of his voice. "Brake her! Stop her!"

The words were hardly out of his mouth before there was a bump which flung Rob clean off his feet. In falling he made a grab at the back of one of the fixed seats, and pulled himself up. As he did so he saw the whole fore-end of the carriage lift upwards, then tilt sideways. He was conscious of a fearful crash, a stunning shock—then all was blackness.

ROB felt water splashing on his face. He opened his eyes to find himself lying flat on his back on very wet ground. From above him a stream of water was pouring on his face. His head was ringing like a bell, and for the moment he could not imagine where he was or what had happened. Presently he recognized the thing which overhung him as the roof of the carriage. The side was gone, broken clean out. Then recollection came back with a rush, and he was on his feet in an instant. He was giddy, bruised and still half stunned, but he did not give one thought to himself.

"Dad! Dad! Where are you?" he shouted as he went staggering through the wreckage.

He had not far to look. Ten steps brought him to his father. Like himself, Mr. Maclaine had been flung out through the broken side of the train and lay on the wet clay at the edge of the permanent way in the pouring rain. But he had not got off as easily as his son, and Rob felt a spasm of fear as he saw his father's closed eyes and the blood on his face. He looked round to see if anyone else had escaped, and at that moment Tex Rayson appeared from the direction of the ditched engine. Tex looked white and shaken, but otherwise not much the worse.

"Gee, but I'm glad to see you on your legs," he said to Rob. "My fireman's finished, and I reckoned I was the only one left. How about the boss?"

"I don't know," Rob answered. "I'm afraid he's badly hurt. Can't we get him out of the rain?"

"You bet. We'll lift him back close under the carriage."

"Wait. I'll get cushions," said Rob who was rapidly pulling himself together.

As they moved Mr. Maclaine he stirred and groaned.

"There's life in him yet," said Tex encouragingly. "But say, looks to me as if his leg was broke."

There was no doubt about it. Mr. Maclaine's left leg was broken above the ankle. Rob spoke up at once.

"Stay with him, Rayson, and I'll go down to the village and find a doctor."

Tex shook his head.

"Guess I'd better do that. If he comes round it'll be better for him to have you around. And see here, you take this." As he spoke he handed a small automatic to Rob. "Kin you use it?"

"Yes, I can use it, but what do I use it on?" demanded Rob, surprised.

"I don't know yet, but the same chap as monkeyed with my brakes."

"Monkeyed with your brakes?" repeated Rob.

"You don't reckon I'd let my train run away with me?" returned Tex with scorn. "Someone had sure been at them brakes before we started. But I got no time to talk now. Sit tight. I won't he long."

He vanished in the grey rain-mist, and Rob and his father were left alone. Some time passed, the rain fell less heavily, and Rob was looking out anxiously to see if help was coming when he was startled by the sound of his father's voice.

"Rob!"

He turned sharply. His father's eyes were open, and though his face was pinched with pain he looked almost himself.

"Rob, you're not hurt?"

"No, dad, I'm all right. Tex Rayson has gone to Magdalena for help. How do you feel?"

"My leg is broken. There's not much else wrong, but that's enough. Did Tex tell you how it happened?"

"He—he said someone had interfered with his brakes."

"I thought it. I ought to have suspected it before we started and had everything overhauled. Well, they have done for us now. Rob, this finishes everything."

The bitterness in his voice fairly frightened his son.

"Ruined us?"

"Yes. This broken leg puts me on my back for at least six weeks. That means that we lose the contract on the time limit."

"But I thought you told me yesterday that everything was going smoothly, and that once the bridge across the Salado River was built trains could run at once."

Mr. Maclaine groaned.

"That's the trouble—the bridge. Suarez has managed to hang me up. But I forgot. You don't understand the situation."

"You haven't told me," said Rob simply.

"It's this way. Suarez is the man who wanted the contract, but I underbid him. He swore to get even, but I did not see how he could harm me. In fact I have hardly given him a second thought. I was a fool to underrate him.

"Now listen. There is only one place where the bridge can be built to cross the Salado; a place so easy that an ordinary steel bridge has been ordered for it, to cost no more than ten thousand dollars. Suarez has realized this and has bought the land at this point. According to the law of this republic of San Lucar, land cannot be commandeered for railway purposes; the company or contractor has to compensate. So Suarez, who has a pull with the Government, is asking a hundred thousand dollars for this land of his. I cannot pay it, I would not if I could. But, as you see, Rob, he has the whip hand of me."

"I see, dad. But even if you were not hurt, what could you do?"

"I don't know. But, something." His lips lightened. "I have been in tight places, but never been beaten yet. And now—" He groaned again, and was silent.

"What about your managing engineer?" asked Rob. "Clandon, I mean."

"No use. A good servant, but no earthly use as a master. He has no initiative."

Rob sat quite still. He was frowning slightly, thinking hard. At last he spoke.

"Then it's up to me, dad."

"You?" Mr. Maclaine raised himself slightly and stared hard at his son. "What do you think you can do—a boy of sixteen, with no knowledge of the country or the conditions, against a glib-tongued, conscienceless scoundrel like Suarez?"

"I don't know, dad, but at any rate I can try," replied Rob quietly.

There was silence again while the contractor's keen grey eyes dwelt upon his son's face. Rob's level gaze did not falter. Then quite suddenly his father spoke again.

"Then, by thunder, you shall try!" he said curtly.

Before Rob could reply there was a shout in the distance, and up the hill came Tex Rayson and four men carrying a stretcher.

"I got a room at the posada for the boss," said the engine driver cheerily. "And a chap's gone for the doctor. Guess we'll have everything fixed up all right in a brace of shakes."

IT was night before Rob arrived at the rail head. Tex Rayson had driven him up on a construction engine. Joseph Clandon, the engineer in charge, met him, and the two walked together up to the camp. On the way Rob told Clandon of the accident. Clandon, who was a thin, dark, spectacled man, looked horrified.

"Mr. Maclaine's leg broken! Good Heavens, what a misfortune!" he exclaimed. "Things were had enough before, but this finishes it."

Rob's nerves had been pretty badly tried during the day. Clandon's outcry nearly finished them, and he had to bite his lip to keep himself from bursting out, but he managed to answer quietly.

"Why do you say that?" he asked. "Surely you and I can tackle the situation."

"You and I!" repeated Clandon. "What can you and I do against this cunning devil, Suarez? lie owns the Tablada, and he won't sell for less than a hundred thousand dollars. If your father can't pay it, why, there's an end of everything. There's no other place for us to build the bridge."

"If there's no other place, then somehow we must get the land from this man Suarez at a reasonable price," answered Rob.

"How?" demanded Clandon.

"I don't know. But see here, I'm tired out. Suppose we leave the discussion until the morning. We shall both feel fresher then."

Clandon shrugged his thin shoulders.

"You can discuss it all you like, or any time you like. Nothing will make any difference," he said despondently.

Rob did not answer. He realized very clearly that Clandon was a broken reed, and that, whatever was to be done, he would have to do it himself. The two walked in silence to the camp where Rob ate his supper and turned in at once.

Rob was always an early riser. The sun was not up when he woke, and he got up at once, had a dip in the small river which ran close to the camp, and, after dressing, walked off to have a look round. The peons, native labourers, who were cooking their breakfasts over fires in the open, stared at the tall young Englishman, but of Clandon Rob saw nothing. Apparently the engineer was still asleep.

"Can't think why Dad ever employed a chap like that," said Rob bitterly, but he did not realize the difficulty of getting good men in this remote part of the world. He was just leaving the clearing when he heard a voice.

"Hulloa, Rob, is that you?"

Rob started and swung round, to see a boy coming quickly after him, a boy of about his own age, but shorter, very squarely built, with a round, freckled face, and hair so fair it was almost white. There was something familiar about the look of him, yet for the moment Rob could not place him.

"You're a nice chap. Why, you don't even remember me," said the square boy, with a cheery grin.

The grin did it.

"Ned—Ned Blunt!" cried Rob, stretching out both his hands.

"Ned it is," answered the other, grinning more widely than ever as he took Rob's hands in his hard brown ones and wrung them heartily.

"My dear chap, I'm jolly glad to see you," said Rob cordially. "But will you tell me how in the name of sense you come to be here at the ends of the earth?"

"My uncle has a coffee plantation on the Salado, and when I left St. Levan's I came out here to learn the business."

"But I thought you were going to be an engineer?"

"Funds wouldn't run to it. But I don't mind telling you I spend all my spare time up here in the railway camp. I got word you were coming. That's why I'm here so early."

"I'm most frightfully glad to see you," said Rob. "I suppose you've heard that Dad is hurt, and that I'm here on my own."

"Yes, I've heard. And I don't mind telling you that you're up against it, Rob."

"Goodness, don't I know it? That fellow Clandon's been rubbing it in."

"Clandon," said Ned scornfully. "He's about as much use as a sick headache. It'll take a man to bluff Suarez."

"Do you think there's any chance, Ned," asked Rob.

"Of course there's a chance," replied Ned sturdily. "A white man can always beat a dago."

"Ned, I could hug you for that," said Rob. "It's the first word of encouragement I've had. Do you know Suarez?"

"Of course I know him—the slimmest, sneakiest skunk in San Lucar."

"Sounds cheerful, but I've got to meet him."

"You shall. But first you'd better get some idea of the lie of the land. I can put you wise to that if you'll come with me."

"I'll be awfully grateful," said Rob, and Ned nodded and led the way.

The raw red gash of a new cutting took them through a stretch of scrubby land. Then it stopped, and Ned led Rob through some trees until they came to a strong wooden fence enclosing a grove of sickly-looking orange trees.

"That's Suarez's land," said Ned. "Worth fifty dollars an acre, and he's asking five thousand. Now we'll follow round the fence to the edge of the cliff."

They did so, and found themselves on the rim of a high bluff About a hundred feet below was a flat savannah, or plain of grass, through which wound a river. Rob looked up and down and at once got the hang of it all.

From the point where they stood to the opposite cliffs was a distance of seven or eight hundred yards, a tremendous gap to bridge, for it meant building up huge piles. But to the left—that is, opposite Suarez's orange grove—a long point of rock ran out, a sort of natural buttress, which approached the far cliffs to within less than a hundred yards. Round the point of this buttress the river ran deep and narrow, with but a strip of shore on either side.

"Do you get it, Rob?" asked Ned.

"Absolutely. That buttress is the key to the whole situation. If we can run the line along the top of it, a single span bridge will do the trick, but if we have to build here, why, the cost will be gigantic."

Ned nodded.

"That's it, and the only alternative would be to make a big cutting and carry the line at a low level across the savannah."

Rob shrugged his shoulders.

"That would cost as much as the bridge. More, I expect, for this rock looks as hard as they make it. Besides, the cutting could never be done in the time."

For a few moments both were silent. Then Ned spoke.

"I don't suppose Suarez is about yet. How would it be if we slipped over into his land and had a look at the buttress?"

"Right you are," Rob answered, and turned to the left.

The fence was easy enough to climb, and the two made their way through the stunted orange trees towards the point of rock. This was even broader and bigger than Rob had supposed. It was ideal for carrying the line. They walked to the end, and Rob was standing gazing down into the river beneath when Ned nudged him.

"We've done it this time, Rob. Here's Suarez."

Rob swung round, and as he did so their enemy himself emerged from the trees. He was a man of middle height and olive complexion, very well dressed in European style; but a crimson necktie added a touch of colour to his suit of greenish tropical tweed. He was perhaps forty years old, handsome, but in a distinctly sinister fashion. His eyes were black as jet and hard as glass. Before Rob could find words Suarez spoke.

"Good morning, gentlemen," he said smoothly. "Perhaps you are not aware that you are trespassing."

Rob felt a perfect fool, yet managed to collect his wits.

"I am afraid that I am aware of that fact," he answered, "but I was tempted to inspect this curious freak of nature."

Suarez nodded.

"Curious—and convenient," he said.

"Yes," said Rob coolly. "Convenient for building our railway."

"Just so. And if your father will pay my price he is welcome to it."

"But your price—forgive me for saying so—is too high," said Rob.

Suarez shrugged his shoulders.

"A man has a right to put his own price on his own property, Mr. Maclaine. My price is one hundred thousand dollars. To use your English expression, your father can take it or leave it."

"He will certainly leave it at that price."

Suarez shrugged again.

"That is his own business," he said quietly, and all the time his hard eyes were searching Rob. "But since you are here, pray spend as much time as you please in inspection. There is a way down. My peon, Pedro, shall show you."

"Thank you. I shall be glad of the opportunity," replied Rob politely.

Suarez gave a call, and a wizened little old Indian came up. Suarez spoke to him in Spanish, and Pedro led the way to the top of a sort of natural stairway that led to the plain below. The two boys followed him down it.

"You kept your temper top-hole, Rob," said Ned.

"I was boiling inside," replied Rob. "But it's no use getting woolly, and I'm glad of the chance of making a proper inspection."

"Suarez was mighty civil," said Ned. "But I saw him watching you. I've a notion he doesn't like you."

"Don't suppose he does. He hates Dad. But here we are at the bottom. Let's go round the end of the Point."

They walked on, Rob carefully examining the rock and the lie of the land generally. They were under the end of the Point, which here overhung slightly, when a rumbling sound from above made Ned look up. Next moment he had seized Rob and shoved him roughly into a crevice at the base of the cliff.

"Look out!" he yelled. "A big slide. My word, the whole cliff is falling down."

His words were drowned by the roar of a huge mass of falling rock, which came thundering straight down upon them.

There was no chance to bolt, nothing for it but to squeeze tight as limpets against the face of the cliff while the mass of loose stuff came crashing past and over them. The noise was deafening, the dust blinding, and as for Rob Maclaine he had so fully expected to be killed that he could hardly believe his senses when the roar passed and he found himself choked, blinded, yet quite unhurt, standing in the little niche at the base of the cliff into which Ned had forced him.

"Phew!" he gasped. "That was a close call. I thought our number was up that time, Ned. It was only your quickness that saved us. I'm awfully obliged to you."

"Never mind that now, old chap," said Ned swiftly. "Thing is to get out of this, and sharp, too. There'll be more down in a minute."

"I didn't think the rock looked so rotten."

"Rock, man! It's not the rock. It's Suarez." Rob gasped again.

"The swine! Do you mean he tried to murder us?"

"And jolly near pulled it off, too. Come on."

"The sooner the better," said Rob, then stopped short. "But Pedro. I'd clean forgotten him. Where is he?"

He glanced round. The grassy savannah in front of them was littered with great masses of raw, fresh fallen rock, and suddenly among them Rob caught sight of Pedro. The peon lay on his face pinned down by a huge stone which, however, did not lie full upon him, but which in its fall had caught against another mass against which it was precariously balanced.

"There he is!" Rob cried sharply, and sprang forward.

"Look out, man!" snapped Ned warningly. "Come back, you ass. You can't help the poor brute, and you're putting yourself at Suarez's mercy."

"Can't help that," retorted Rob. "Can't leave the wretched man to die like this."

As he spoke he had reached the rock which pinned Pedro, and was using all his strength to try to shift it. Ned saw that it was too much for him.

"He's right," he growled. "But it's suicide all the same."

With that, he ran forward, and adding his strength to Rob's, the two between them swung the great ragged fragment aside, and managed lo release Pedro. Rob stooped, got his arms around the Indian and lifted him. As for Ned, he had turned and was gazing with scared eyes up at the top of the cliff.

"See anything?" asked Rob quickly.

"No. The beggar's a deal too cute to show himself." Then an instant later: "Watch out! Here's more coming," he shouted.

With a great effort of strength Rob swung the wizened figure of the Indian over his shoulder, and scurried back under shelter of the overhang, before he had reached it there came the whistle of a falling object and a stone the size of a man's head struck the very spot where Pedro had been lying and hitting one of the other stones burst like a shell, scattering them all with its fragments. Rob's face was grim and set.

"So that's your game, Mr. Suarez," he said between set teeth. "Very good. You've warned me now, and it will be my own fault if you catch me napping a second time."

"Bit early to talk of second times. We're not out of the wood yet, old son," grumbled Ned.

"We're fairly safe here," replied Rob. "The cliff overhangs quite a bit. Anyhow, Suarez can't see us. And I don't think he'll try the same trick again. The day's getting on, there are people about, and someone might spot him."

"That's true," agreed Ned. "What about the Indian? Is he finished?"

Rob turned to the man whom he had laid on the grass close under the foot of the cliff.

"Why, his eyes are open!" he said in surprise as he bent over him. "Are you badly hurt, Pedro?"

"I am bruised, Señor, and the breath is out of my body," replied the Indian speaking in Spanish. "But praise to the Saints, and thanks to your brave help, I am not otherwise hurt."

"That's uncommon lucky," smiled Rob. "I suppose you know where the rocks came from?"

Pedro's dark eyes narrowed.

"I know, Señor," he answered. "It was that robber dog, Suarez. Always I have hated him, though my poverty forced me to work for him. But no more. Rather will I starve than ever again do a hand's turn for that man."

"You shan't starve if I can help it," said Rob kindly. "And now I wonder if it would be safe for us to try to get back to camp. I badly want some breakfast."

Pedro rose stiffly to his feet and looked round. Suddenly he pointed across the valley to where a man riding a mule was crossing the opposite flat.

"It is safe, Señor," he said quietly. "Suarez will not risk a watcher of his attempts at murder."

"Pedro is right," said Ned. "Let's push on."

The Indian went with them back to the camp, where they found Clandon sitting in his tent at breakfast.

"Not a word to him or anybody," whispered Rob to his companions; then, sending Pedro to get some food with the men, he took Ned into the tent.

"You have been looking round, Mr. Maclaine?" said Clandon.

"I have. Mr. Blunt and I have been up on the Tablada."

Clandon started slightly.

"Did you see Suarez?"

"Yes, and had a talk with him."

"Then no doubt you realize that it will be impossible to deal with him?"

"I realize that his terms are absurd," replied Rob quietly. "As for paying a hundred thousand dollars, that is out of the question. But I should like to know, Mr. Clandon, why the right of way was not arranged for before work began?"

Clandon shrugged his shoulders.

"It was. At least we thought it was. I understood that the Tablada belonged to the Indian Pedro who was quite willing to sell. It was only a few weeks ago that Suarez cropped up with proof that Pedro's title was bad, and that he had pre-empted the land from the State."

Rob nodded.

"Ah, now I begin to understand. And is it worth while for us to go into this matter of the title?"

"None whatever," Clandon answered with more decision than he usually showed. "Even if we could prove that Suarez's title is bad it would take months—years perhaps. The Courts here are the slowest in the world, and Suarez has friends in high quarters. Jose Frias, the Prime Minister, is his brother-in-law."

"Then we must find some other way out of our troubles," said Rob.

Clandon made a despairing gesture.

"There is no other way," he declared. "I have surveyed the country for miles around, and I tell you plainly that it is out of the question. If we cannot carry the line across the Tablada we may as well throw up the whole business."

Rob rose.

"We won't do that," he said with quiet decision.

"NED, are you busy?"

Rob had taken Ned into his tent and the two sat together, glad of the shelter from the now blazing sun. Ned grinned.

"Busy! I shouldn't be here if I was. Just at this time of year there's hardly one day's work a week on the plantation. It's only when we are picking that we're really busy."

"Then you can stay with me a bit?"

"Nothing I'd like better. A little excitement of this kind is the breath of life to me. Besides, you know it's very jolly to see you again."

"Right, oh! Then write a line to your uncle to say where you are, and I'll send it by one of our men."

Ned nodded, and taking up a pencil and pad of paper wrote the note which Rob at once sent off.

When the messenger had gone Ned turned to Rob.

"And now what are you going to do, old son?"

"Have a look round," replied Rob. "The first thing is to get wise to the lie of the land."

"Afraid that won't help you much. You may take it from me that Clandon is right when he says that the only place where you can push the line across is the Tablada."

"You may both be right, but I've got to be sure, Ned."

"By all means make sure. I'll come with you. I know the country pretty well."

"That's just what I want. Hulloa—who's this?" A lean figure appeared at the entrance to the tent.

"It is Pedro Ruiz, Señor," answered the Indian in his soft Spanish.

"Come in, Pedro. Anything I can do for you?"

"Señor, you have done too much for me already. It is time that I did something in return for your great kindness. I have come to beg you to accept this little token of my gratitude."

As he spoke he took something from the pocket of his shabby coat and laid it on the camp table in front of Rob.

Rob picked it up. It was a little figure of a naked man about six inches long, beautifully done in some dull, heavy, bronzy metal.

"But this is exquisite," said Rob quickly. "It's mighty fine work," declared Ned. "I guess the British Museum would give quite a lot for that, Rob."

Rob looked uncomfortable.

"Pedro," he said gently, "I wish you would not offer me anything so valuable as this. If you were to sell it—"

Pedro drew himself up.

"Señor, this was the work of my ancestors. It would not be fitting that I should sell it. But to you I give it gladly."

Rob saw that he would bitterly offend the old man if he pressed his point.

"Then I accept it with gratitude, Pedro, and I will always keep it."

Pedro nodded.

"Then, Señor, it will bring you good luck. Yes, and fortune also, for the figure is that of the Gilded Man."

He bowed and was gone. Ned picked up the image.

"That's what it is, Rob. It's the Gilded Man who was a sort of hereditary High Priest of the people in this part. And I say, Rob, d'ye know what it's made of?"

"Bronze, isn't it?"

"Not a bit of it. It's solid gold."

Rob whistled softly.

"Where do you suppose it came from?"

Ned shook his head.

"Hard to say, but probably out of one of the old Inca Treasure Caves."

"What! I thought they had all been rifled by the Spanish long ago."

"Not a bit of it. The Incas hid their stuff a jolly sight too well for that, and the Indians, their descendants, know how to keep their mouths shut. Slabs of the old soft Inca gold are constantly cropping up in the towns about here. The shopkeepers know they come from the old hoards, but nothing will ever induce an Indian to show a white man where they are to be found."

"H'm, I wish we could find one," said Rob. "It would be mighty useful just about now." He stood up and shook himself. "If you're ready let's go," he said. "I want to cover a lot of ground to-day."

"Wait! Surely you're going to take a gun."

"What for—to shoot Suarez?"

"No, you old idiot. But when you've been here as long as I have you'll know better than to go messing about in the woods without a gun."

"What game is there?"

"Jaguars, pigs, deer, to say nothing of snakes."

"I'll take your word for it," said Rob as he took a rifle from its case, and stuffed a handful of cartridges into his pocket.

"Which way are you going?" asked Ned.

"West—down the river," was the answer.

Five minutes after the two had left the camp the jungle swallowed them up, and in another five, but for Ned, Rob would have been hopelessly lost.

"I'd no notion it was so thick," said Rob as he stopped and taking off his broad-brimmed felt hat swept the perspiration from his streaming forehead. "Why, one can't see ten steps in any direction."

"Nothing to what it is down in the swamps," grinned Ned. "There you're lucky if you can see ten inches."

"But what are we to do?" asked Rob as he gazed helplessly at the amazing tangle of trunks and creepers and foliage of all sorts which surrounded them on every side. "Surveying is out of the question, and it would take an army to cut down the stuff."

"That's all right. We shall find it more open further on," said Ned.

"Thank goodness for that. This stuff suffocates me," was Rob's answer as he plunged forward.

Before he had gone two steps, Ned had seized and jerked him back. At the same time something flashed past his head with a vibrant hum, and he saw Ned strike at it fiercely with a branch he carried.

"What's the matter?" asked Rob in a confused tone.

"You'd have known what was the matter fast enough if that fever wasp had got you."

"Fever wasp?" questioned Rob in amazement.

"Yes. Nastiest insect they keep here, except perhaps the Boma ant. If that thing had stung you, you'd have been laid up for a week. Gives you fever."

Rob looked unhappy.

"And the Boma ant—what's that?"

"Inch-and-a-half long, black as your boot, with a sting in its tail like a scorpion. Get stung by one and the chances are you'll be clean off your head with pain inside five minutes."

Rob shivered in spite of the heat.

"Are there any more horrors of the same sort in these woods?"

"Heaps, but I'm not going to tell you just now, for I don't want to discourage you. Anyhow, you'll find out soon enough. Meantime let me lead the way. Knowing what to look out for, I shan't be so likely to walk into trouble."

Rob was only too glad to let Ned take the lead, and the latter conducted him carefully in and out among the giant trunks of jackaranda and ceiba and many other trees, each of which, if planted alone in any English park, would have brought sightseers from all over the country. At last it got a little lighter, and quite suddenly they stepped out from the steamy hot-house atmosphere of the thick forest into the full blaze of tropical sunshine. In front was a wide shallow valley covered with coarse grass and dotted with clumps of huge trees. Rob started forward eagerly.

"Is that a brook down the bottom?" he asked eagerly.

"Yes, but I believe the bed's pretty nearly dry. Still, you may find enough water for a drink."

"Drink, man!" retorted Rob. "It's not a drink I'm looking for, but if that's a brook, why, it must run into the Salado, and that's exactly what I've been looking for!"

"How do you mean?"

"Man, can't you see? We could make a loop and run a line down into the valley, cross the Salado by a temporary bridge and probably find some way of climbing the cliffs opposite."

"I see," said Ned, "but I'm afraid it's no use, old chap. There's no opening in the cliffs. This little brook drops into a swallow hole a little way further on, and I suppose makes its way underground to the Salado."

There was such disappointment on Rob's face that Ned felt very sorry for him, but in a very short time he had pulled himself together.

"That's bad luck," he said quietly. "But if you don't mind, Ned, I'd like to walk down to the end of the valley and see what the cliffs are like."

"Right you are, but you won't see much to encourage you."

Crossing the savannah, they came to a belt of heavy timber bordering the stream. As Ned had said, this was nearly dry, but the bed was covered in with a most amazing jungle of tall grasses and flowering reeds. The branches of the trees overhanging this narrow swamp were gorgeous with many coloured orchids, and small greenish monkeys swung and chattered in their tops.

"Keep a bit clear of the thick stuff, Rob," said Ned.

"Why, what's the matter?"

"Snakes," was the brief reply.

Rob did not look happy. He hated snakes.

For a time he kept his eyes wide open, watching for any movement in the grass, but there was none, and presently he became so interested in the lie of the land that he forgot Ned's warning, for the valley seemed to contradict all the ordinary laws of nature. For a mile or so it sloped gently towards the Salado; then instead of breaking down into the plain of the big river, its lower end was barred by a huge rampart of cliff covered with thick timber.

"This is a queer business, Ned," said Rob.

"You mean the lie of the land?"

"Just so. This looks like a regular river valley, and I can't imagine where the river has gone to."

"It's not a bit of use counting on anything out here," said Ned. "It's the craziest country that ever was made."

"The most annoying," growled Rob. "If it wasn't for those confounded cliffs, this would be just the place to run the line down into the plain. Let's go as far as the end, and see if there's a possible chance of cutting a tunnel."

Ned shook his head.

"Not much, I'm afraid, old chap. There's a big breadth of rock between this and the Salado valley. Still, we'll have a look-see."

The two walked on together close beside the swampy stream until they had reached a point about a couple of hundred yards from the cliff face. Then all of a sudden Rob caught a glimpse of something moving among the branches to the right, a great glistening many-coloured coil that moved slowly, with a smooth silkiness impossible to describe, over a huge branch.

"A snake!" he cried, and flung his rifle to his shoulder.

"Don't shoot!" cried Ned, but it was too late. Rob's finger had already pulled the trigger, and the sharp report of the rifle sent echoes crashing through the still heat.

Before he could fire again Ned caught his arm.

"Steady on! It's only a tree boa. Quite harmless. You missed him anyhow, so—"

His voice was cut short by a squeal, a squeal so sharp and angry that Rob instinctively knew that there was something dangerous in the sound. But he was not prepared for the absolute horror which showed on Ned's face.

"Peccaries!" gasped the latter. "And by all that's awful, you've hit one. Run for the rocks. It's our only chance."

As he spoke he jerked him round, and the two set to running hard towards the cliffs.

Next moment the squeal was repeated by a hundred other throats, and there was a sound like the crashing of a squadron of charging cavalry. Rob glanced back over his shoulder to see the brake heave as the herd struck it. Next instant scores of little black pigs came bursting through, but small as they were, they were the fiercest-looking creatures he had ever seen or dreamed of, and their long sharp snouts were armed with razor-sharp white tusks which glittered ominously in the bright sunlight.

And the pace at which they came—it was terrific. Rob saw at once that he and Ned could never reach the cliff before they were caught and ripped to pieces by their terrible pursuers.

Ned saw it, too.

"That tree!" he panted, pointing, and dashed for a big ceiba of which the lowest branches hung within five or six feet of the ground. Rob spurted for all he was worth, and he and Ned reached the tree together, and each made a leap at a branch and hauled themselves up. Rob did not stop until he was nearly a score of feet above the ground, then reaching a huge limb more than a foot through swung his leg over it, and looked down.

Below him the ground was black with a multitude of the savage little pigs which leaped upwards and clashed their tusks till they rattled like castanets. Their small eyes were red with rage, and every bristle on their muscular bodies stood up stiff. The air was full of the harsh, stye-like scent of them.

"What brutes, Ned!" said Rob, looking across at his friend who was perched opposite and a few feet away. "It's a jolly good thing we're safe out of their reach."

"We're out of their reach," said Ned, "but as to our being safe, that's a very different matter."

"How do you mean? We've only got to wait till they go away."

Ned laughed.

"And how long do you reckon that will be?" he asked.

"Oh, I don't know! A hour or two, I suppose."

"Say a week or two, son, and you'll be nearer the mark."

Rob stared.

"You're rotting, Ned."

"Wish I was. No, it's straight goods, Rob. These black demons are the only sort of beast that never gives up, and never knows when it's beat. Even if you had your rifle which I see you haven't, you might sit up here and shoot 'em one by one as long as your cartridges lasted. They'd draw off a bit, but they'd never go."

Rob knew Ned was speaking the truth, and his heart sank lower and lower till it felt as if it had reached his boots.

"But they must get hungry and thirsty," he objected.

"There's plenty of grass," said Ned, "and plenty of water. And if there wasn't some would stay and watch while the others went to feed."

"What awful brutes!" groaned Rob.

"You've said it. They're the worst ever."

"But isn't there a chance of anyone coming to look for us?"

"A mighty slim one. We're three miles from the camp, and no one knows which way we went. And even if they did, it's all odds they'd simply be chased up another tree."

"Then what in sense are we going to do about it?" demanded Rob in despair.

"Sit tight. There's nothing else for it," said Ned grimly.

Sit tight they did, first making themselves as comfortable as possible. The peccaries gave up their raging and jumping, and began to graze around, but Rob noticed that they never went far away from the tree, and if he or Ned so much as moved half a dozen would come rushing back in a flash. Time wore on, the heat grew terrible, and though the boys were protected from the full blaze of the sun by the heavy foliage of the great ceiba, they began to grow terribly thirsty. Rob looked longingly at the water of the brook gleaming among the tall rushes only a few yards away.

"Ned," he said, "there's a branch the far side of the tree which almost overhangs the brook. If one of us crawled across he could drop a hat down at the end of a string and dip up some water."

Ned considered. Then he nodded.

"It's just on the cards," he agreed, "but you've got to remember that the peccaries will be right on top of that hat before you can say knife."

"I doubt if they'd reach the spot," said Rob. "It's pretty boggy. Have you any string?"

Ned felt in his pockets.

"Yes, here's a coil. Plenty for what you want. Going to try it?"

Rob nodded and started. The moment he began to move the peccaries moved, too. Squealing and snorting, they followed beneath him as he climbed. They leaped up three or four feet into the air, falling back heavily into the tangled herbage.

The climb was easy enough except for the tangle of creepers which matted everything. They were so thick that they soon hid Ned from him. He had to go far out in order to reach a point over the one open pool, and the branch, though big, sagged unpleasantly.

Presently he saw that the peccaries had been obliged to stop. Some of them were up to their bellies in black slime from which rose a nasty sour reek.

"You brutes!" he growled. "I wish I could drown the lot of you."

At last he was exactly over the pool. It was only a few feet across and surrounded by a wall of tall rushes and water plants. He noticed that the trunk of a big dead tree lay across one end of the pool almost hidden in the coarse growth.

Getting a good grip with his legs, he took off his hat and was beginning to tie the string to it when from beneath came a sound so startling that he as near as possible lost his balance. It was exactly like the escape of steam from a small boiler. He looked down, and what he saw was so monstrous and utterly incredible that for the moment he sat frozen, unable to believe his senses.

The trunk—the dead tree trunk—had come to life, revealing itself as a serpent of such appalling dimensions as seemed only to belong to the realm of nightmare. Why, the thing was forty feet long, and as thick as Rob's own body! Its head, the size of a five-gallon keg, had just risen from the reeds, and this appalling sound was its hiss of rage at being disturbed from its noonday siesta. Rob found himself looking right down into its eyes which were yellow as gold, and full of a cold, yet deadly menace.

For a moment the breath left his lungs, and he felt as if turned to stone. He gave himself up for lost. The great serpent's head shot upwards; beneath, he saw the thick reeds flatten under the crushing weight of its writhing coils. Then, just as he was expecting the terrible head to dart against him and the huge curved fangs to fix themselves in his body, suddenly the head swept down and passed beneath him. Then came a squealing scream, and he caught a glimpse of a peccary struck and flung back among its fellows as if hit by a battering ram.

It was enough. In an instant its companions made a combined rush, and some at least got near enough to the serpent to fix their teeth in its scaly hide.

What followed was a battle such as few human eyes have ever seen and fewer spectators lived to speak of. Reeds crashed, mud and water flew, the vast coils of the serpent spun and wheeled, and its monstrous head darted this way and that with incredible speed and force. One blow was enough for each peccary that was struck. It was like hitting rats with a loaded club, for not one survived the lightning stroke of the great anaconda. Yet the rest, absolutely regardless of life, kept leaping in, snapping at the coils, making their tusks meet in the thick hide of the monster. Some were flung yards, some crushed into the mire under the weight of the writhing coils.

As for Rob, he sat as if frozen. His eyes were glued upon this terrible combat, and to save his life he could not remove them. A hand grasping him by the shoulder was the next thing he knew of, and here was Ned alongside him.

"Can't you hear me, you idiot?" he cried quite angrily. "I've been shouting to you to come on."

"I never heard you," Rob told him.

"You hear me now. Come—sharp, or it will be too late."

"Mean to say we can escape?" said Rob, but Ned did not answer.

He had turned and was scrambling like a lamplighter right across the branches. Rob wasted no time, and in a few moments the two were back on their original perch, on the side of the ceiba further from the swamp.

Ned glanced back. Not much was to be seen, In it from the frightful crashings, hissings and squealings it was evident that the battle was still in full swing. Then Ned looked upwards.

"Not one of the little brutes in sight," he said swiftly. "Come along, Rob. This is our chance. But for Heaven's sake don't make a sound."

As he spoke he dropped lightly to the ground, and Rob quickly followed him. Ned made straight for the cliff, and Rob ran beside him. Rob thought he heard something behind him, and glanced back over his shoulder just in time to see about half a dozen of the wicked little pigs come charging in pursuit.

"They're after us, Ned," he gasped.

"I know! Run!" was all Ned said.

Run they did. No one ever knows quite how fast he can travel until he is forced to run for his life, and as Rob said afterwards, the pace at which they did that hundred odd yards must have been near to record. Anyhow they reached the cliffs well ahead of their ugly little pursuers, and flinging themselves at the steep ascent went scrambling upwards. The rocks were broken and covered with shrubs and creepers which gave them good hand hold, and up they went from ledge to ledge at top speed. Nor did they stop until they were a good fifty feet above the level of the valley, where they found themselves on a broad ledge with a sheer scarp of rock above it. Ned turned and looked back.

"Safe for the minute," he said, pointing to the peccaries which were surging and squealing at the foot of the cliff.

Some had got up a few feet, but it was quite evident that they could get no further.

"But I'm not sure that it isn't out of the frying pan into the fire," he added.

"What do you mean, Ned?"

"Use your eyes, Rob. We can't climb any higher, and we're still a deuce of a long way from the top of the cliff. And there's no water—or shade."

ROB did not answer at once. He was carefully inspecting the face of the cliff. At last he pointed to the left.

"I think I see a way up, Ned. If we move along this ledge as far as it goes, I think there's another we can reach. Then do you see that dark line in the distance? It looks to me like a sort of crevasse or perhaps what mountaineers call a 'chimney.' And it seems to lead right up. Shall we try it?"

"I'm game," replied Ned briefly. "You lead. You know more about this kind of climbing than I do."

This was true, for Rob Maclaine had done a deal of climbing in the fells of Cumberland and in the Scottish mountains.

"But go slow," added Ned warningly. "There may be snakes anywhere along these ledges."

"No more pythons, I hope," said Rob with a shudder.

"No. Cascavels—rattlesnakes they call them in North America."

Sure enough they had not gone far before there came a warning hum, and one of these ugly reptiles raised its flat head threateningly. Rob picked up a big stone and crushed it, and kicked the writhing coils over the edge. The snake fell among the peccaries who were following below, and they instantly tore it to ribands.

"A warning to us," remarked Ned dryly, but Rob did not reply.

The climb was not easy, and the heat was frightful. Also the two were so thirsty that their mouths were like parchment and their tongues like dry sticks. But Rob proved himself right as regards the ledges, and he patiently worked from one to another towards the dark line which he had spotted zigzagging across the face of the cliff. The bushes and creepers so nearly hid it that Rob had felt very doubtful about its real nature, therefore, when he and Ned did at last reach it he was all the more pleased to find that it was just what he had hoped—a deep crevice seaming the cliff almost from top to bottom. Swinging round the edge, he climbed into it, and Ned followed him.

"Phew!" said Ned, mopping the perspiration which streamed down his brown face. "It's something to be out of the sun, anyhow. But what about it? Does this lead to the top?"

Rob did not answer at once. He was looking about, and there was a puzzled frown on his face as he stared at the rocks on either side.

"What's the matter?" demanded Ned. "What are you looking at?"

"I don't quite know, but this is a precious queer formation."

"Everything's queer in this rum country," agreed Ned. "But what strikes you as specially odd?"

"The strata are quite different on the opposite sides of this crevice."

"That's Dutch to me. Does it mean anything?"

"Do you mind if we climb down a bit?" said Rob.

"Down!" repeated Ned in surprise. "I thought we wanted to get to the top."

"So we do, but I badly want to see what this crack is like lower down."

Ned shrugged his shoulders.

"Anything you like, but I don't know how long I'm going to stick it without a drink."

"You may get a drink sooner than you think," replied Rob quietly, and set about clambering down the crack. It was easy enough, for the rock was sound, and there were plenty of footholds.

Rob did not speak, and Ned, realizing that his friend was really after something, asked no questions, so some five minutes passed during which they reached a point not more than twenty or thirty feet above the valley floor. Rob swung out of sight around a big jutting slab, and next moment Ned, following, heard him give a sharp cry.

"A snake?" he cried, springing forward.

"No—a cave!" was the quick answer.

"A cave!" repeated Ned, who was both relieved and disappointed. "Well, why not? There are heaps of caves in these cliffs."

"Ah, but not like this," replied Rob, pointing into a deep narrow crack which cut straight into the cliff.

He laughed.

"Don't look so puzzled. This is what I was looking and hoping for. See here, Ned, if I am fight—and I think I am—this is the old river bed."

Ned merely shook his head.

"It's this way," explained Rob. "Once this valley was lower than it is now and instead of that tiny brook a decent river came down it. Then one day, a few hundred years ago, there was an earthquake and the cliffs on either side of the valley toppled over and blocked it. This is the point where they met."

"But where's your river?" demanded Ned.

"Dried up, perhaps, for the climate here is changing and getting drier. Or it may be running underground."

Ned nodded.

"I see, but what good is all this to you?"

"I can't tell until I have explored the cave. Let's go a little way in. I've a torch."

He led the way and Ned followed. The entrance was so narrow that it took some squeezing to get through, but almost at once the cave broadened out to a breadth of ten or twelve feet and a height of twenty.

The torchlight showed it sloping gently into the heart of the cliff. Rob was now quivering with excitement.

"It's all right, Ned," he cried, his voice echoing hollowly down the cavern. "It's all right. We've got that ugly beggar Suarez on toast. Here's our tunnel practically made!"

"What, you mean you can run the line through it?"

"I do indeed. Of course it depends on whether it goes right through or not. Are you game to come on a bit?"

Ned shrugged his shoulders.

"It's a drink I'm thinking about."

"Me, too, but here's the place to find water if we are to find it at all."

"Then I'm your man," replied Ned hoarsely. The cave grew higher and wider, so high indeed that the small beam of Rob's electric torch failed to reach the roof. In spite of his sufferings from thirst Rob's spirits rose. This was tremendous luck, for if the tunnel continued on this scale it would be a comparatively simple matter to run the line through it and so down into the valley of the Salado. The only question would be whether he could find a way of carrying it up the scarp on the far side. But he had not much doubt about this, for he knew that the cliffs on that side were not so high as these, or so steep. The air grew cooler and damper and suddenly Ned's hand fell on Rob's arm.

"Water—do you hear it?" he said sharply.

Sure enough, from out of the gloom came the welcome tinkle of dripping water. Rob swung his torch, and presently the light fell on a tiny rock pool into which a little spring was bubbling from the side of the tunnel.

Both made for it at once, and flinging themselves down cupped their hands and drank greedily. The water was clear as glass, and cold as if it had been iced. At last Ned rose to his feet.

"I say, that was the best ever. I feel like new," he said.

"So do I," agreed Rob. "Now what are we to do? This torch won't last for ever, and I haven't another battery. Do we go back or push on?"

Ned's usually merry face turned grave.

"I suppose we ought to go back, but the trouble is the peccaries, Rob. We don't want to run into them again."

"We certainly don't," agreed Rob. "Then shall we push on and trust to getting out the far side into the valley?"

"Bit chancy, isn't it? We don't know if there's any opening."

"Of course we don't, but it looks as if there ought to be. Got any matches?"

"A few."

"Then I tell you what. Let's go back and make some torches from the shrubs on the cliff face. Then we'll have another shy at exploring the cave."

"That sounds good," agreed Ned. "Come on."

It did not take long to get back, and luckily Ned knew just what wood to use. With their knives they cut good bundles, lashed them together with creepers, and before they returned into the cave had a good look down the valley, but now there were no longer any peccaries in sight.

"Still, you can't trust them," said Ned. "They may be hidden up in the tall grass, and since we've dropped our rifles under the ceiba we mustn't take chances. Let's see if we can get through this cave of yours."

The torches flung a fine glare on the rugged roof and sides of the tunnel as the two marched through it. They passed the spring and pushed on for some distance.

"A regular, ready-made tunnel," said Rob with great satisfaction.

"Two, if you ask me," returned Ned who was a little ahead and pointed as he spoke to a great opening on the right of the main cave, an opening quite as large as the tunnel itself.

Rob whistled softly, then went nearer and held his torch into the opening.

"This is the real cave," he said, but the words were hardly out of his mouth before a number of large dark creatures came flitting out of it. They came at tremendous speed but in absolute and uncanny silence. In an instant they were all round the boys.

"Bats!" cried Ned, beating at them. "Look out, Rob. They'll put your torch out."

The warning was too late. These hideous creatures of the darkness swirled like great moths upon the lights, and almost instantly had extinguished both torches, leaving the two boys in darkness so intense that it might almost be felt. Rob cried out sharply, for one of the horrid things had caught its claws in his shirt and was beating him with its leathery wings. He tore it off and flung it from him.

"Light up! Light up again," he said to Ned.

"What's the use?" was the answer. "The moment I strike a light, they'll be on us again, and there are hundreds of them. And I've only got four matches left."

"And my torch is burnt out," groaned Rob. "What on earth are we going to do, Ned?"

Ned considered a moment before replying.

"The only thing is to turn and crawl back the way we came, Rob."

"I'm not too sure of the direction," said Rob. "Still, if you think it's the only thing to do I'm game."

"I'm sure it's the only thing to do," Ned answered. "I daren't risk the last of our matches with all these brutes of bats flying about."

"Next time we come we'll have something better than torches," Rob murmured as he started.

Moving in a cave without light is about the most nerve-racking job in the world, to say nothing of being the most difficult and dangerous. It is true that, on their way in, the boys had not seen any pits or dangerous holes in the floor, but that was not to say that there were none, and anyhow there were plenty of loose boulders great and small. In the darkness these seemed to have multiplied themselves a dozen times over, and every few moments Rob, who led the way, kept bumping into one or other of them. Then the only thing was to crawl round it, and this of course put him off the straight. At last he stopped.

"Ned, I haven't a notion which way we're going," he said.

"I think we're all right, Rob," was the answer. "We're going up the slope. That's the main thing. Keep on."

They kept on. Rob's eyeballs fairly ached in the vain effort to catch a glimpse of light. At last he did see something, or fancied he did. He stopped again.

"Ned, what's that?" he whispered sharply.

"What's what?"

"Those two green lights. Ned, they're eyes." He felt Ned start back.

"Yes, I see them," he whispered back. "You're right. They're eyes right enough. And a panther, I believe."

"A panther! What shall we do?"

"Chance the bats and light up again. If we don't the brute will have us. Keep still, Rob, I have the matches."

Rob's heart was thumping hard as he listened to Ned fumbling for his matches. Little as he had seen of this strange country, yet he knew enough to recognize the terrible nature of the danger which confronted them. There are seven sorts of panther or jaguar in the South American forests, and the largest exceed in size the great Bengal tiger. He kept his gaze fixed on those lambent green orbs which glared at him out of the surrounding blackness.

He heard the scratch of the match, and the flame, tiny as it was, nearly blinded him. Ned touched the match to the resinous sticks composing the torch, and by good luck they caught at once, sending up a hot red flame. As the light leaped up, both heard a low ugly snarl, and caught a glimpse of a huge tawny beast which leaped from the summit of a flat, table-shaped rock not twenty yards in front, and flashed away up the cave with almost incredible speed.

"Phew, but he's a big one!" gasped Ned. "The sort they call pintado."

"Where's he gone?"

"Haven't a notion, but anyhow he won't face the torch. I say, we seem to have got away from the bats."

"I expect they were only in that branch cave," said Rob, and looked round.

Then he gave a short laugh.

"What's the matter?" asked Ned.

"Matter. Only that we've turned right round and gone the wrong way."

Ned whistled softly.

"So we have. What do you want to do about it?"

Rob did not hesitate.

"Go right back. I'm not following that pintado, not without a rifle anyhow. I'd sooner face the peccaries."

There were no more bats, and the torch lasted well. Both breathed more freely when they stepped out again into daylight through the narrow opening of the cave.

"What about it?" said Ned with his engaging smile. "Have you done enough exploring for one day?"

"You bet," returned Rob emphatically. "We're due for camp and grub. The only problem is the peccaries."

"None in sight anyhow," replied Ned. "I think, if we slip quietly into the woods to the west of the glade, they probably won't spot us. It's that or climbing the cliff."

"I vote we chance it," said Rob.

Chance it they did, and gained the trees with out seeing a sign of the savage little black beasts. Ned guided his friend safely through the recesses of the forest, and in less than an hour they were out in the open again, and within sight of the camp.

"My word, I feel as if I could eat an ox," said Ned.

"You'll get a piece of one out of a tin," laughed Rob, and sure enough that was exactly what the camp cook provided—a large and very excellent tinned ox tongue. They practically finished it between them, and had put away a big dish of fruit and a large pot of tea into the bargain when Clandon came in, looking even more dispirited than usual.

"That fellow Suarez has been here," he said.

"What for?" demanded Rob.

"He was after that Indian, Pedro, his servant."

"Of all the cheek!" exploded Rob. "I hope you sent him off with a flea in his ear."

"I—I told him it wasn't any business of ours," said Clandon weakly.

"On the contrary, it's very much our business. Pedro is under our protection. I have promised him work."

"We have got as many men as we need," objected Clandon. "More—now that we are hung up."

"We shan't be hung up any longer," said Rob confidently. "But where is Pedro?"

"I don't know. He was not to be found."

Rob stared at Clandon.

"You don't mean to say you let that brute look for him?"

"I didn't want any more unpleasantness," was Clandon's feeble answer.

There was such a flash in Rob's eyes that for a moment Ned thought he was going to explode. But Rob had inherited plenty of self-control from his strong-willed father, and he checked himself.

"Please understand, Mr. Clandon," he said formally, "that this man Suarez is in future not to be allowed in or about our camp. And now I will tell you what I have done to-day and how I propose to proceed with the work."

Before he could say more the mosquito net which hung across the flap of the tent was lifted and Pedro came swiftly in.

"Señor, save me!" he begged, running towards Rob.

"What from?" began Rob, and the words were hardly out of his mouth before another figure stood in the entrance. It was Suarez dandily dressed as usual, his white teeth showing in an unpleasant grin. Rob shot to his feet.

"What do you want here?" he asked, and though he did not raise his voice in the least, there was no mistaking the fact that he was intensely angry.

"My peon, Señor Maclaine," replied Suarez, pointing to Pedro. "The man is in my debt, and the law gives me the right to claim his services in exchange.

"The law gives you no right to trespass on my property," answered Rob with admirable coolness. "I will ask you to leave at once."

The quiet tone in which Rob spoke deceived Suarez. The man knew that he could handle Clandon, so took it for granted that he could bluff this boy.

"When you hand over my servant I shall leave. Not before," he answered coolly, and actually stepped forward in the direction of Pedro who was cowering behind Rob.

What happened next was almost too quick for eye to follow. Before Suarez had the faintest idea what was happening, Rob had him by the collar of his dandy drill jacket, and spinning him round ran him out of the tent just as a professional chucker-out puts a rowdy customer out of a public-house.

The camp was surrounded by barbed wire. Rob ran Suarez straight down towards the nearest opening and through it; then letting go he administered one lusty kick, a kick which fairly lifted the dago, and deposited him on hands and knees in the grit and gravel of the gateway.

Suarez rose slowly to his feet, and his face was livid and his lips twitched as he faced the young Englishman. His hand shot to his knife, but he saw Ned, rifle in hand, standing close behind Rob, and thought better of it.

"I will kill you for that," he said slowly, and so fiercely that the words seemed to grate in his throat. "I will kill you," he repeated. "Not now, but later—and slowly."

"MUCH obliged, Ned," said Rob as they watched Suarez out of sight. "He'd have knifed me if it hadn't been for your rifle."

"Sweet creature!" remarked Ned with a dry smile as Suarez's white jacket finally faded into the gloom. "Wonder what he'll do next."

"It isn't what he'll do; it's what we are going to do," returned Rob.

"Oh, I know what you're going to do, old chap, and that's get on with the job, but I want you to remember that I know these dagoes a bit better than you. That chap means mischief, and he's cunning as well as revengeful. I'll ask you as a personal favour to go armed and to keep your eyes very wide open."

"Anything to please you, Ned," smiled Rob. "Now I've got to go and talk to Clandon."

Clandon, as usual, threw cold water on Rob's suggestion, but Rob's enthusiasm was proof against that sort of thing. And presently Clandon submitted to the stronger personality, and agreed that the new plan might be worth trying, always supposing that they could find a way to carry the line up the opposite side of the valley of the Salado. It was agreed that this should be surveyed the very next morning, and if it proved feasible, that work on the loop should begin at once.

They all turned in early, Pedro being given a bunk in the workmen's tent.

Very early next morning Rob, with Ned and Clandon, went down the valley, and very soon discovered a spot where a ravine or "barranca" made it possible to run the line up the southern cliffs. In very good spirits they returned in time for midday dinner.

Rob's first task was to write to his father, explaining fully what he intended to do. As soon as he had sent the letter off he collected his men and marched them off to the cave. Clandon with some helpers were left to survey and mark out the loop line which would carry the line to the new tunnel.

By Ned's advice, a number of the men were armed, but the peccaries seemed to have moved off. The boys ventured back to the big ceiba to recover their rifles which they had dropped there. They found no fewer than fourteen dead peccaries on the field of battle, while beyond the reeds and tall grass were crushed as if a steam roller had been over them, but of the monstrous serpent itself there was no other trace.

The peons looked a little scared when they saw the narrow mouth of the tunnel. Most of these natives are more or less frightened of meddling with caves, but Rob made them a little speech in his best Spanish, and promised them extra pay if they would run the job through in time, and since the tall young Englishman was already popular with them, they soon got over their nervousness, and promised to do their best.

The very first thing Rob did was to set the drillers at work and put in blasting charges on either side of the long narrow crack in the cliff. When these were fired they brought down enormous masses of rock, letting air and light into the more open space beyond.

Next, well armed and provided with acetylene flares, Rob and Ned, accompanied by a couple of gangers, set out to explore the tunnel to the far end. As before, the bats came swooping upon them, but a few charges of small shot brought them down by the score, and soon put an end to that trouble. They pushed on again, keeping a sharp look out for the panther, but apparently the shooting had scared him, and they saw nothing of him.

Then suddenly Rob gave a sharp exclamation and pointed to a dim ray of light which showed in front.

"She's open right through," he cried. "Did you ever know such luck?"

Sure enough, there was an opening out on the river side. It was very narrow and veiled by a perfect mat of creepers, but these were very soon chopped away, and then the sunlight streamed in.

"Jove, what luck!" cried Rob, quite carried away by excitement. "It's a tunnel practically ready made."

"Yes, you've certainly struck it lucky, Rob," agreed Ned more gravely. "I really think it ought to pan out all right. What's more, the roof seems fairly sound, which is a very big asset. If it wasn't for that wretched dago, I should be feeling fairly happy."

"You've got Suarez on the brain," said Rob with a touch of irritation. "What on earth can that beggar do to hurt us?"

"I don't know," confessed Ned, "but this I do know—that, as soon as he realizes what you're doing here, he'll be up to some monkey trick."

"I shall give orders that he is to be arrested if he is seen anywhere near the works," replied Rob sharply. "And if I catch him I shan't bother about the law. I shall simply put him under lock and key until the job is finished."

Ned made no reply, but his face remained graver than usual.

Next day work began in real earnest. Part of the camp was moved down to the mouth of the tunnel. Clandon, with half the men, began to build the loop to the tunnel mouth; Rob and Ned took charge of the actual tunnelling. They were with their men all day long helping and encouraging them, and Rob in particular was so cheery, so full of enthusiasm, that he got more out of these peons than Clandon had ever done. Pedro worked as well as any, but somehow he always managed to keep close at Rob's elbow. In a hundred little ways he showed his gratitude to the young Englishman who had rescued him from slavery.

A week passed, both ends of the tunnel had been opened out, and big progress made with clearing out the masses of loose boulders and smoothing the floor.

Then one morning, when Rob came out of his tent after breakfast, he got an unpleasant surprise. Not a man had gone to work. They were lounging about in knots, looking scared and talking in low voices. He turned to call Pedro, only to find him at his elbow.

"What's the matter, Pedro?" he asked sharply. The little man looked unhappy.

"They are on strike, Señor. They will not work any more."

"Heavens, why not? Aren't they getting enough pay? Is not the food right?"

"It is not that they quarrel with, Señor," replied the Indian. "It is that they are frightened."

"But what of?"

"Of the ghost, Señor. The ghost in the tunnel."

At this moment Ned came out of the tent.

"Hulloa, what's the trouble?" were his first words.

"They say there's a ghost in the tunnel," Rob answered quickly. "Did you ever hear such rot? But wait. I'll drive them back to it—and quick too."

Ned checked him.

"Steady, old chap. You won't do a bit of good by trying to drive them. They're as superstitious as African negroes, and if you try to force them back to work, likely as not the whole lot will simply clear out."

"Then what are we to do? Every day, almost every hour counts."

"I know that, but it's a case of 'Hasten slowly!' We must investigate. May I talk to Pedro?"

"Do! See if you can get to the bottom of it."

Ned spoke to Pedro and the two talked earnestly for some minutes. Then Ned turned back to Rob.

"It's a man called Gonsalvez who saw the ghost. He was later than the others in the tunnel last night, and the ghost appeared out of the Bat Cavern."

"What sort of a ghost?"

"Something with a perfectly awful name which sounds like Calafguin. It's the old Inca God of Grief, and of course they all think that his appearance means some awful disaster, and are scared stiff. But if you ask me, it's a put up job."

Rob's face hardened.

"You mean it's a trick of Suarez's?"

"You've hit it in one, Rob. That's exactly what I do mean. If you remember, I told you we hadn't done with him yet."

Two red spots showed on Rob's brown cheeks.

"I was a fool. I ought to have set a guard at both ends of the tunnel," he said.

"I don't suppose it would have done a bit of good, Rob. This is a very cunning ruffian we have to deal with."

"Well, what are we to do now, Ned? You know more about this sort of game than I do. I'm in your hands."

"If you ask me, the first thing to do is to explore the Bat Cavern. But you and I will have to do it, alone. We shan't get one of these chaps to come with us."

Rob nodded.

"I'm game. Shall we go at once?"

"The sooner the better. But it may be a big job, and we had better take arms and food."

"Yes, and plenty of lights and a rope. And perhaps I had better send word to Clandon so that he can keep an eye on the chaps while we're away."

"Quite a good notion," agreed Ned. "You write him a line, and I'll get the kit ready."

In less than half an hour all was ready, and the two were away into the tunnel. So far they had been much too busy to dream of exploring the Bat Cavern. All they had done was to put a light there with a net to trap the bats, and in this way they had destroyed a number of the hideous creatures. Apparently they had pretty well finished them off, for barring a few stragglers none appeared, and these were easily beaten down with sticks.

The boys carried a powerful acetylene lamp like a motor-bicycle lamp, but with a larger container. They had also electric torches with spare batteries, food for twenty-four hours with flasks of cold coffee, a long coil of strong rope, and a small axe. Each carried a magazine pistol, with plenty of cartridges.

"Keep your eyes on the floor, Rob," said Ned. "Our friend may have left traces behind him."

Next moment Rob had stooped and picked up something. It was a feather, a small white feather, which he showed to Ned.

"That's it, sure thing," said the latter. "I'll lay it's from his disguise."

"But this is quite near the mouth of the cave, Ned," said Rob. "Seems to me that the chances are he came into the tunnel from the river end, and never went any further than this into the Bat Cave. In that case, what's the good of exploring here?"

"You may be right," Ned answered. "But that's not my notion. I don't believe that Suarez would have risked coming into the tunnel in daylight. My idea is that he sneaked in the previous night, and hid himself in this side cave. And if you ask me, I shouldn't wonder if he's here still."

Rob looked up sharply.

"Ned, you've a head on you," he answered quickly. "I believe you're right. Come on."

They went on. The cave narrowed, but the floor was singularly smooth. Also the air remained perfectly fresh. The two boys proceeded cautiously, swinging the light from side to side. The silence was intense, and each footstep sent strange echoes whispering into the depths. The cave grew still narrower, and presently Ned pointed to the walls.

"Chisel marks," he whispered. "Some of the ancient people have opened this out."

The cave became a passage cut in the solid rock. The chisel marks in the wall were clear as if made yesterday, yet the floor was smoothed and hollowed seemingly by the passage of many feet. Here and there they saw characters carved in little squares on the walls, but the letters belonged to no language of which they knew anything. Ned stooped, and Rob heard him give a little hissing breath. Ned pointed, and in the dust which lay upon the floor Rob distinctly saw footmarks.

"Suarez?" he whispered, and Ned nodded assent.

Rob felt an odd thrill. It seemed to him that at last their enemy was delivered into their hands. He slipped his right hand into his pocket to make sure that his automatic was handy.

The passage curved, and as they rounded the bend they came suddenly upon a flight of broad steps leading down into the gloom. Rob hesitated a moment, but Ned urged him onwards, and the two went slowly down.

They were half-way when a sudden loud noise, a sort of clang, made them both pull up short. Imagine their horror when they saw that half-a-dozen steps had fallen away behind them leaving a gap far too wide to jump, and by its blackness of unfathomable depth. At the same moment a low cruel laugh sent ugly echoes whispering through the depths.

Great as was the shock, Rob recovered in an instant. Drawing his automatic, he raised his lantern, flashing its light back up the flight of stone steps in an effort to locate their treacherous enemy, but there was no sign of him, and again came the jeering laugh.

"No, Señor Maclaine, I may be a fool. I have been a fool, for at first I under-estimated your abilities. I did not credit you with the enterprise to find this outlet for your railway. But I am not fool enough to stand up and let you shoot at me."

He laughed again.

"On the contrary it is I who could shoot you if I so desired. Yes, you make an excellent target for my pistol, standing as you do in the full light of your fine new lantern."

Quick as a flash, Rob switched the slide over the glass, and laying the lantern on the floor, stepped aside. Suarez laughed again.

"A needless precaution, Englishman." His voice grated with malice. "Be assured. I have not the faintest notion of shooting you or your companion. Had I desired to do so, I could have killed you both when you passed me a minute ago." Again he chuckled, and the sound of his laughter made Rob feel as if icy water was trickling down his spine.

"Ha—ha! You never saw me, but walked on into the trap which I had prepared for you, as innocently as two rabbits.

"Such a pretty trap," he went on. "You have lights and a little food. That I know. I would recommend you to explore your prison, for there is much of interest to be seen. The one objection, so far as you are concerned, is that you will never return to report on your discoveries."

Once more his laugh sent echoes grating through the gloom.

"Oh, so you propose to keep us prisoners here?" said Rob, speaking with a coolness which almost startled Ned.

"Precisely, my young friends, and I can assure you that a more perfect prison does not exist in South America. Large, airy, and absolutely sound-proof."

Rob laughed.

"Does it occur to you that our men know where we have gone and that when we fail to return they will come and look for us?" he remarked.

The chuckle that came back was like the mirth of a lost soul.