RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"The Land of Silence," C. Arthur Pearson Ltd., London, 1921

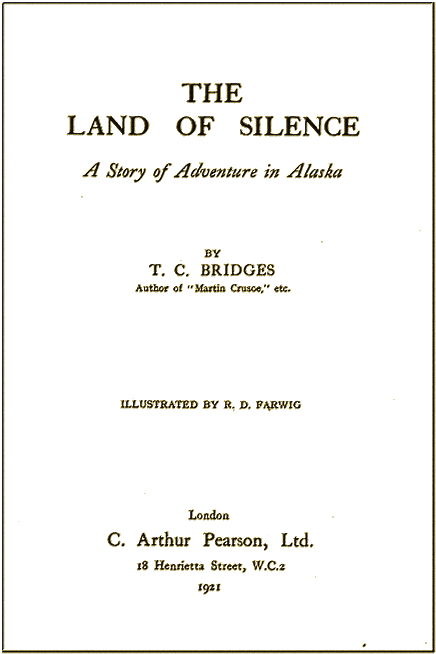

Title page of "The Land of Silence,"

C. Arthur Pearson Ltd., London, 1921

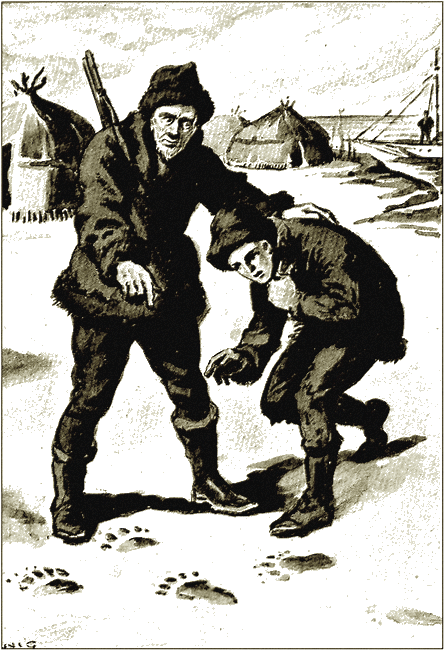

Frontispiece.

"Look at that!" Bart gasped. "Them's a bear's prints."

ACROSS a cold grey sea, under a leaden sky, a small but stoutly-built sail-boat beat into a stiff sou'-westerly gale. Away to the east the huge snow-capped mountains which lie in the bight of the great Alaskan Bay towered grimly among the driving mists; from the west the waves rolled up out of the North Pacific with no land to check their force for thousands of miles.

In all that vast waste of stormy sea and sky, the boat seemed to be the only sign of human life; yet by the anxious look on the faces of the two boys who formed her crew, it seemed clear that they feared something even worse than the dull rage of the gathering storm.

A great, hissing wave lifted the boat like a toy on to the crest of its towering mass, and the youngster who held the tiller glanced back over his shoulder.

"I see her, Tod," he said sharply.

Tod Clancy, lean, ragged, black almost as a Siwash, nodded.

"I saw her five minutes ago, Harry," he answered in a fierce undertone. "I knew Manby would never let us get away."

Harry Brand, who was as gaunt and tattered as his companion, tightened his lips.

"I've a mind to put her round and run for it."

"No use," replied Tod quietly. "He'd catch us just the same. Besides, the Pixie 'ud never stand it. She'd be pooped and swamped in five minutes."

"That's true," said Harry curtly. "Though, 'pon my soul, I'd almost as soon be under the sea as in the hands of that brute."

"It's our gold he's after," exclaimed Tod.

"I know that," answered Harry bitterly. "He's got the claim; he's got a million of his own; he's got everything in the world that he needs; yet he's chasing us to steal from us the poor hundred ounces of gold that we've sweated a whole long summer to gain."

"He'd say it was his, and that we had stolen it," said Tod, with a twisted smile. "He's great on law and justice, is Mr. James Manby. Let her off a bit!" he added sharply. "There's a squall coming."

For the next few minutes it took them both all they knew to keep the Pixie above water. The freezing spray dashed over them, and when the squall had passed Tod was still baling hard.

"We'll have to get another reef in," said Tod.

"And lose our last chance?" snapped Harry.

"We haven't got a chance, Harry," returned Tod. "Not a dog's chance. And you know it."

Harry shrugged his shoulders.

"Oh, I know it right enough. What's sail against steam, especially in these wicked Arctic seas?" He glanced back again over his shoulder. "Yes, the Night Hawk is coming hand over fist. She'll catch us in another quarter of an hour."

"In that case we may as well run in under the land," said Tod. "I doubt if she'll stand up to another of these squalls."

Harry looked round dully.

"All right," was his heavy reply, as he let her off a few points, and she went scudding in towards the tall black cliffs.

The steam yacht that was chasing them was a long, low vessel of four or five hundred tons, and by the way she ripped through the smoking seas had evidently plenty of engine power. As the Pixie turned, so did she, and as she was cutting across the arc of a circle she gained very rapidly.

The Pixie was hardly in smoother water before the yacht was within hailing distance.

"Heave to!" came a shout.

A big man, fat as well as tall, was standing on the bridge, with a speaking-trumpet to his mouth. His voice came loud and harsh above the seethe of the surf and the cold cry of the bitter wind.

"Heave to, or I'll run you down," he added fiercely.

He did not wait for an answer, but the yacht came rushing up alongside the boat, nearly swamping her and taking all the wind out of her sails.

"These are the thieves who have bolted with my gold," said the stout man to another who stood beside him. The latter wore a dark blue uniform and evidently was skipper of the Night Hawk.

"Yes, Mr. Manby," agreed the latter. "What do you propose to do with them? Are we to take them aboard?"

"Take them aboard?" snapped Manby. "No! Send two men over into the boat. Make the young thieves hand over the gold and everything else they've got. Then turn 'em adrift."

The captain gave an order, and at once two big fellows went over into the boat. They were both armed.

The boys, chilled to the bone and utterly worn out, were in no shape to make any resistance. The men flung open the stern locker, seized the small but heavy packet of gold dust and flung it up into the yacht. Then they began to collect the small store of coffee, sugar, flour, and bacon, which was all the boys had for their long voyage southwards to civilization.

Harry stood up stiff and straight.

"Mr. Manby," he began with a sort of suppressed fierceness, "you may have some legal claim to the gold, for it certainly was won from the claim which for some reason or other you have sworn was yours. You have no right whatever to our other property."

"Right—you talk to me of rights!" retorted Manby, scowling down at Harry. "You have none. You have stolen my gold, and if I claimed my rights you would both be doing five years in the penitentiary. Thank your stars that I leave you your liberty."

"What's the good of liberty if we're to starve to death?" answered Harry doggedly.

"That's your look out," said Manby with an ugly laugh.

"Got everything, men? That's right. Now cast off, and leave those brats to their fate."

Harry sprang to his feet.

"Tod, we can't be left like this," he cried in despair.

He made a spring to try to reach the deck of the Night Hawk, but one of the men struck him heavily in the chest, knocking him down into the bottom of the boat, where he lay half- stunned.

By the time he had scrambled to his feet Manby's yacht was fifty yards away, ploughing along in a southerly direction. He and Tod were left tossing on the bleak waves in the Pixie.

JUST how they reached the shore, the two boys hardly knew, but an hour later the Pixie lay at the inner end of a long, narrow fiord, at the head of which a swift river broke into the sea.

Close to the mouth of the river was a little natural harbour, and here the Pixie and her crew were safe from any wind that blew.

Not that this was much comfort to her crew, for the two boys were so chilled, so worn-out, so utterly disheartened, that they simply sat still, not attempting to help themselves.

Tod was the first to move.

"Buck up, Harry," he said hoarsely.

Harry gave a bitter laugh.

"What's the use? We've got no grub. We can't get any. We may as well chuck it now as later."

"That's no way to talk," Tod answered. "'Where there's life, there's hope' is a good old motto. Anyhow, if we have to die, let's die warm. I see some drift-wood on the beach, and we've still got matches."

He clambered out of the boat, and began to collect the wood which lay at high-tide mark. Harry, ashamed of his fit of despair, followed stiffly.

Tod cut shavings with his knife from a piece of resinous pine, and a welcome flame glowed in the heart of the pile. Soon there was a roaring blaze, and the warmth set the sluggish blood flowing in the veins of the castaways.

"There ought to be some mussels," said Tod presently.

He got up and began searching among the rocks, and presently came back with a hat full of the shellfish. These they roasted in the ashes and ate as best they might. It was a poor sort of meal, but better than nothing.

Tod flung the shells away and turned to his chum.

"Harry, we've got to make up our minds what to do."

Harry shrugged his thin shoulders.

"Haven't I been racking my brain the last hour? Honestly, Tod, I can't see any way out. Even if the weather were good, and the wind right, it would take us a week to reach Sanuk, and that's the nearest place where we can get grub and blankets. How are we to do it without food? We can't live on mussels even if we could carry enough."

"That's true. But what about running out to sea and trying to meet one of the steamers coming down from the North?"

"Out of the question, Tod. Their track lies hundreds of miles west. Remember we are right up in the bight, and they come round the Horn of Alaska, nearly 800 miles away."

"Then we must try to get back up the Copper River to one of the settlements."

Harry shook his head.

"The current is far too strong for us to work the boat up it, and as for going afoot, it would take months. Just remember that winter will be on us in less than a month."

"It doesn't seem too likely that we shall be here to see it," returned Tod grimly. "But I'm not going to give up tamely, old man."

"Nor am I," replied Harry. "If it's only to get even with Manby, I'm going to make a struggle. I vote we load up with the shellfish, and start south in the morning. We'll have to stick to the coast, and spend the nights ashore. There's always the chance of finding Indians."

"Good," exclaimed Tod. "That's settled. Now let's fix up for the night."

They got the sail up from the boat to form a shelter. They needed it, for a cold rain was falling. Manby had taken their blankets and bedding as well as their food. They would have to keep the fire going all night or perish with cold. Though it was only the first week in September, the weather was bitter. They were but a few score miles from the vast glaciers of St. Elias, with their frontage of three hundred miles of gigantic ice cliffs.

Weary as they were, the boys got little sleep that night. The gale grew worse. It shrieked among the tall cliffs overhead. Outside the surf was one continuous thunder. And big as the fire was, it failed to keep them warm.

Morning found them stiff and aching, and cruelly hungry.

Harry looked out across the raging foam.

"No moving for us till this is over," he said.

Tod did not answer. He was wrenching mussels off the rocks.

It blew for three days. By the third evening the boys were very nearly done for. You cannot stand exposure of this kind on a diet of mussels and cold water. Harry's cheeks were sunken; Tod was suffering agonies from colic. They had only just strength left to gather wood for the fire.

Towards dusk Harry got up to fetch fresh wood. Tod saw him stumble as he walked. He dragged his feet like an old man.

Tod's own pluck was run down.

"We're done," he murmured. "There's no chance. We haven't strength left even to set the sail."

He broke off short, for Harry had suddenly scrambled on to a rock, and was waving his hat frantically.

"What's up?" cried Tod breathlessly.

"A boat—a boat coming out of the river, and a man in it," shouted back Harry.

Tod staggered to his feet, and together the two watched in quivering excitement as the boat came nearer. It was only a canoe, such as the Siwash Indians use. But the man in it was white. He had already spotted Harry, and was paddling towards him. A few minutes later the canoe grounded, and he rose and stepped out.

A huge man he was, well over six feet, and broad and deep- chested, yet gaunt and bearded, and looking as if he had travelled hard and far.

"Helloa, kids!" he cried, speaking with a strong American accent. "Guess you're weather-bound, eh?"

Harry took a step towards him, and suddenly collapsed and fell flat on the beach.

The big man picked him up as easily as he would have lifted a baby.

"Gee!" he exclaimed. "Plumb starved. That's too bad."

"We've been here three days," put in Tod hoarsely. "No blankets. Living on mussels."

"Sit you down," said the big man curtly, as he lifted Harry into the shelter of the sail. "There, give him a sup o' this, and have a drop yourself. Do as I say. I'll fix you."

He handed Tod a battered flask, then turned to his canoe. He was back in a minute with a huge bundle on his shoulders. He opened it, and Tod nearly fainted when he saw a fat side of bacon, a sack of flour, a bag of sugar, another of coffee, cooking pots, and all sorts of equipment.

The speed with which the stranger got a meal ready was magical. Inside twenty minutes the boys, revived with a dram of spirits apiece, were tucking into fried bacon, hot sweet coffee, and biscuits.

They could feel life flowing back into their veins with every mouthful, while their host fed them like children, and smiled gravely as he did so.

At last they were satisfied, and began to try to thank their new friend.

"Shucks! You'd do as much for me," he retorted. "Cut out all that stuff, and come down to bed rock. My name's Bart Kinder. What's yours?"

"I'm Harry Brand," said Harry, "and this is Tod Clancy. We've been up the Copper, digging all summer. Then a fellow came along, and said we'd been working his claim. Cut up rough, and ordered us to give up our dust, and clear. We did clear, but we took the dust with us. He chased us, caught us out at sea, took everything we had, and turned us loose. That's our story."

"Took your grub and blankets too!" exclaimed Kinder. "Gol durned if I ever heard such a thing. He ought to be shot. Say, there's only one feller alive as could do such a cur's trick, and that's James Manby."

"You've struck it in once," said Tod.

Bart Kinder's kindly face hardened.

"The skunk! I've been up against Manby myself, so I knows. That's his living—to find claims as isn't properly registered, and buy in the titles. Some day someone's a-going to lynch him."

"It won't be us," said Harry. "He's gone south in his yacht."

"But he'll come back, and that's when we'll square accounts, I fancy," replied Bart. He paused. "Say," he went on, "it's luck for me, meeting up with you folk."

"The boot's on the other foot," Harry laughed.

"Luck for both of us then," returned Bart. "This ain't no weather for an ocean trip in a canoe."

Tod stared.

"You don't mean you were going out to sea in that thing?" he exclaimed.

Bart shrugged his great shoulders.

"Needs must!" he said. "I didn't have no choice. But I'd a sight sooner sail in a tight little craft like that 'un o' yours."

"You mean you'll come south with us?" asked Harry eagerly.

Bart shook his head.

"It's not south I'm bound for, mates. It's west."

The boys stared one at another. The same thought occurred to both.

Bart's grey eyes twinkled.

"No, I'm not looney, lads. It isn't Japan I'm aiming at. It's the Horn of Alaska."

Bart's eyes widened.

"The great peninsula. But—man alive—what a place to go to, with winter on us in a month!"

"Furs is best in winter," said Bart quietly. "And furs is what I'm after. Specially bears. See here, fellers, I got a good grub stake—enough for the three of us. Can't we do a trade? Your boat and your help—my grub and blankets, and a half share of the pelts. How does it strike you?"

Harry's sunken eyes sparkled.

"I'm your man," he cried.

"You bet your life," added Tod.

Bart nodded. There was a satisfied look on his face.

"Fine!" he said. "I guess this here gale is most blown out. To-morrow the three of us leaves for the country of the biggest bears, the queerest natives, and the most almighty volcanoes in this here continent."

TRY starving on mussels for three days. Spend three nights crouching on bare rocks with nothing but a sail between you and a bitter gale. Then get a square meal and wrap yourself in a couple of blankets, and see how you'll sleep.

The sun was an hour up next morning before Bart Kimber had the heart to rouse Harry and Tod, and when he did so, breakfast was ready, the canoe was cached, the Pixie was loaded, and everything ready for a start.

"The gale's gone and the sun's a-shining like glory," was his greeting, as the boys jumped up.

"And we've been snoring like pigs while you've done all the work," replied Harry reproachfully.

"Guess you needed all the sleep you could get," said Bart. "We got a right hard trip before us."

"I don't care what it is so long as there's grub like this every day," remarked Tod cheerfully, as he fell on the sizzling bacon.

"Eat hearty," said Bart. "There's plenty more where that came from."

"You've certainly got a fine grub stake," laughed Harry, looking at the pile of cargo in the Pixie.

"We'll need it," Bart told him. "You see, I reckoned to have a couple o' Siwash or Stick Injuns. And I knowed I'd got to feed 'em. But I'd a sight rather have you two lads. That's why I said 'twas luck a-meeting you."

The two boys were hungry as wolves, and the breakfast they put away was a caution. But they did not take long about it, and very soon the sails were up, and the Pixie, with the tide in her favour, was racing down the fiord.

Outside they found a crisp, southerly breeze blowing, before which they reached away rapidly in a westerly direction.

The view was magnificent. Inland the gigantic peaks of McKinley, Elias, and a host of other mountains towered like sugar-cones against the pale blue sky. The coast was a mass of broken cliffs, and cragged islets.

"I'm a-going to make right across for Kodiak Island," Bart told them. "But I'm not a-going to land there. I reckon to coast round the eastern end into Shelikoff Straits, pick a good spot, lay up the boat for the winter, then strike right inland."

"Ever been there before," asked Harry.

"Yes; I been there one winter, and I tell you I got furs all right. But I shipped 'em down to Porte and in the old Abraham Lincoln. And durned if she didn't pile herself up jest above Sitka, and I lost every blamed fur."

"Bad luck!" said Tod.

Bart shrugged his shoulders.

"Jest luck. But, say, boys, we'll do better this trip. And let me tell you, furs is worth more'n gold right now. That there war over to Europe sent the prices a-soaring, and they've not come down yet. Ef we have a good winter, we'd ought to have enough to buy ourselves a farm apiece." He broke off short. "What's up?" he demanded.

"There's a steamer following us," said Tod breathlessly. "A yacht, too, by the look of her."

"It's the Night Hawk!" exclaimed Harry.

"What—that there poison skunk, Manby?" snapped Bart. "I thought you said as how he'd gone south?"

"I thought he had," Harry answered. "But I suppose that gale caught him, and that he's been weather-bound all this time. Now he's spotted us again."

"I'd have thought he'd done us harm enough already," said Tod bitterly.

"He's poison clear through," declared Bart. "He didn't ever mean you fellers to get away. Yes, he's a-following us. That's a sure thing. Say," he added sharply, "there isn't no reason fer him to see you. Get you down under the fore coaming. Hide yourselves. He's got no call to interfere with me, and, by gum, if he does, he'll find himself up against trouble."

The boys hesitated.

"Get you down," repeated Bart. "I mean it. You leave this job to me."

Rather unwillingly the two obeyed. The opening was blocked with a pile of dunnage, leaving them only a tiny space for air. There they crouched together, while Bart sailed the boat.

"She's a-coming up all right," said Bart presently. "Gee, but she can shift."

"They say she's the fastest thing in Alaskan waters," replied Harry. "Manby had her built specially at San Francisco."

"He can afford it," added Tod.

There was silence a while, but soon the boys, though they could not see her, could hear the beat of the Night Hawk's powerful engines.

"Lie low," said Bart warningly. "She's mighty close."

The sound of the engines grew louder. Harry's heart was beating hard.

"If there's trouble, we'll fight for it," he whispered in Tod's ear.

"You bet!" was Tod's answer.

"Ahoy, there!" came a voice through a speaking-trumpet. "Is that the Pixie?"

"That's her name," answered Bart. "Who are you, and what do you want?"

"This is the Night Hawk—Mr. James Manby," was the reply. "Mr. Manby wishes to know where you got the boat you are sailing."

"What's that to do with him?" returned Bart truculently.

"This. The Pixie was lately in the possession of two gold thieves whom Mr. Manby has been pursuing."

"Two gold thieves," repeated Bart sarcastically. "Do you mean them two poor kids as I found starving on the beach, and as sold me their boat for a square meal?"

"They sold you the boat, did they? Where are they now?"

"If you wants to know, you'd best go back up Bear River Inlet," retorted Bart.

"We don't want any of your lip, my man," snapped the other, who was at last beginning to lose his temper.

"My man!" mimicked Bart. "Thanks be, I'm not your man, nor anybody else's but my own. And ef you've quite finished asking questions, mebbe you'll get out o' my way, and let me shift along where I'm a-going."

There was a pause. Harry and Tod listened breathlessly. They fully expected that Manby's crew would try to board the Pixie. If they did, well, this time it would be no tame surrender, but a fight to a finish. The voice came again, high- pitched and angry.

"If I wasn't busy I'd come aboard and teach you manners," snapped Manby's skipper.

"Come along, any two of you," invited Bart. "Come on, and I'll teach you a lesson in minding your own business."

In reply the other snarled some words which the boys could not catch. Then, to their intense relief, the engine beats quickened again.

"It's all right," said Bart presently. "She's a-moving. But don't you go for to shift just yet. I reckon they'll watch us till we're plumb over the skyline."

"What luck they didn't come aboard!" said Harry.

"That's why I asked 'em," grinned Bart. "I knowed that 'ud put 'em off it quicker'n anything. I wasn't too civil to 'em either."

"You certainly were not," chuckled Harry. "But I see now that you did exactly right. I wonder if they'll go and hunt us up Bear River."

"They won't get fur up," prophesied Bart. "And say, boys, it's in my mind as the next time there's any hunting done, it's going to be us who'll be the hunters, not Manby."

"Why do you say that?" asked Harry.

"I haven't got no real reason. I just feels it in my bones," replied Bart, with a quiet smile.

The wind freshened, and Bart's attention was occupied with handling the boat. She tore through the water at a great rate.

A quarter of an hour later Bart spoke again:

"Guess you can come out now. The yacht's hull down and it's all hunky."

"THAT'S Kodiak Island," said Bart, jerking a thumb in the direction of a distant blur of land, "whar the big bears come from. But, bless you, there's jest as big over on the mainland, and lots o' other stuff besides."

"The other stuff seems to mean some whopping big mountains," said Harry, as he pointed to a great cone of snowy whiteness which lay ahead.

"Volcano, too," added Tod. "I say, what's that queer noise like distant thunder?"

"That's old Bogoslav a-talking to himself," said Bart. "He's always a-working. You can't see him from here, but there isn't no place you can't hear him. And the funny thing is that the sound of him seems to make the silence all the worse, specially in the winter time or when the fog comes down."

"A lot of fog, isn't there?" asked Harry.

"That's so—specially in calm weather. Ye see, the warm Japan current strikes right in along this coast and hits the cold land. That's what makes all the smoke."

"No fog to-day anyhow," said Tod. "And topping weather."

"Aye, it's the Injun summer," Bart told him. "And a mighty good job fer us. But we won't get more'n two or three weeks of it, and we got to use every minute."

"Getting into winter quarters?" questioned Harry.

"That's it, and stocking 'em up with grub. I reckon to lay in a ton or so of salmon, as well as deer and bear meat."

Running before a fine sailing breeze, the Pixie rapidly approached the land. Long beaches of jet-black sand faced the sea, backed by low bluffs. Behind them the land sloped very gently upwards, but the mountains were a long way inland.

"Do we run right in?" asked Harry.

"No, Harry. Thar's a village I'm a-making for. Tassusak, they calls it. Jest a little Siwash settlement. It lays a piece inland, but we can see it from the coast."

"What do you want with Indians, Bart?"

"Carriers," replied Bart. "How do you reckon we're a-going to get our stuff inland else?"

"Are we going far inland?"

"A right smart way. It's all tundra back o' the beach. We got to cross that and make our quarters in the woods."

"What about the Pixie?" asked Harry.

"Thar's a creek by Tassusak whar we can lay her up fer the winter."

"You seem to have thought of everything," said Tod Clancy, with a laugh.

"I guess I got to," replied Bart, rather dryly. "This isn't no pleasure picnic, believe me."

It had been dawn when they sighted the long black beaches of the great peninsula. It was eleven in the forenoon when they sighted Tassusak, and about an hour later they were working up the mouth of the river towards the village.

"Don't think much of your village, Bart," said Harry. "Looks to me as if a parcel of kids had been trying to set up a Scout camp and made a horrid hash of it."

"They're dug-outs," Bart answered. "Jest dug-outs with roofs of poles and turf. I'll allow these here Injuns aren't no great shakes as architects."

The tide was turning. The wind was light, and they moved very slowly. Bart stood up and stared in the direction of the village. There was a puzzled look on his bearded face.

"What's the matter, Bart?" asked Harry.

"That's jest what I wants to know. Where's the Injuns? I don't see a sign of one high or low, and, speaking in general, every mother's son on 'em ought to be down by the water's edge a- waiting fer us."

"Perhaps they're out hunting."

"Aye, the bucks might be out arter caribou or a-netting salmon, but what about the squaws and the kids? You mark my words, lads, there's something wrong up here."

"Do they ever get raided by other tribes?"

"Not as I knows of. The Stick Injuns is quarrelsome sometimes, but they don't come down to the coast."

"We'd best land and find out," suggested Tod.

"I guess we had, but we'll take our guns along. And one of us'll stay by the boat."

They were now opposite the village, which was nothing more than a score or so of skin or turf huts on the bank above the creek. They anchored close in, and, leaving Tod in charge of the boat, Bart and Harry scrambled ashore through deep and sticky mud. They climbed the bank, and, reaching the top, found themselves within a few yards of the nearest hut.

But the place was silent as a tomb. Not a voice was to be heard, no barking of dogs, not a curl of smoke arose.

"This is plumb onaccountable," growled Bart. "I can't see no reason fer it. These folk were all here two year ago. Wonder if it were smallpox hit 'em and wiped 'em out? I've heard tell of such things. You wait here and I'll have a look into this here hut."

His tall figure seemed to dive underground, and he disappeared into the hut. He was out again in a minute or so, and now he was frowning with perplexity.

"This beats all," he said. "Everything's there like the folk had slept there last night. I'll vow, anyhow, they haven't been gone more'n a few hours. I can't make nothing of it."

"Let's hunt round," suggested Harry. "There may be some old man or woman left in one of the huts."

"That's so. Come right along."

They started. Two more huts were drawn blank. Moving across to a third, Bart pulled up short, and stood staring fixedly down at the ground.

"Gee, boy, look at that!" he gasped.

Harry looked. In the soft ground were marks. They were the prints of feet. At first he fancied that they were of human feet, but a moment's inspection showed that this was out of the question. They were too big and too deep. Also the toe-prints showed marks of claws.

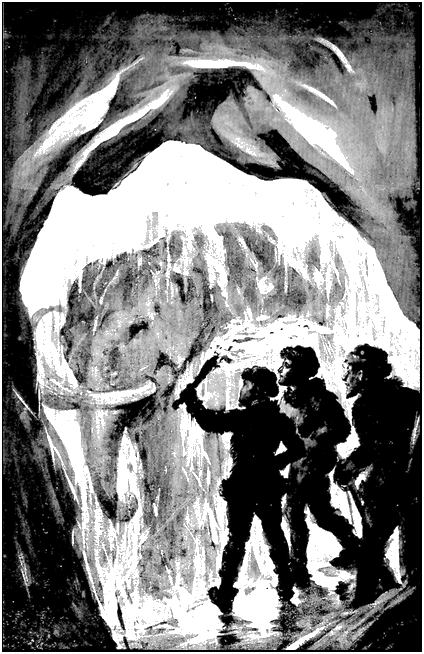

"A bear!" he said sharply.

"A bear, sure enough," agreed Bart. "But a bear that's mighty near as big as a house!"

Harry looked at Bart.

"Is it the bear that's scared the Indians away?" he asked.

"That's jest what I'm asking myself," said Bart. "But it don't seem possible nohow. These here fellers have guns, and I never heard tell of a whole village a-panicking because of a bear. Onless—"

He paused, and a curious expression crossed his big bearded face.

"Unless what?" asked Harry.

"Onless it was a ghost bear," added Bart slowly.

"A ghost bear?" repeated Harry, puzzled. Then he grinned. "How the mischief could a ghost make holes in the ground like that?" he asked, pointing again to the gigantic footprints.

Bart did not laugh.

"You don't get me, youngster. There's funny things happens up in this here North Land. I'm not a-saying there's anything in it, but these here Injuns believe as bears and wolves gets possessed by evil spirits. Then they becomes as cunning as men and ten times as dangerous as any man. The Injuns calls 'em ghost bears, or ghost wolves, and says as bullets can't kill 'em. There's nothing else on sea or land as they're as scared of."

Harry no longer smiled. Though he had been less than six months in the Arctic, the lonely charm of these great silent lands had already sunk into him, and he was not prepared to jeer at any Indian belief, however fantastic it might sound.

"What shall we do?" he asked. "Shall we follow up the tracks?"

"I reckon we got to," replied Bart gravely. "This here's a queer business. I never heard tell of a bear that would walk right through a village in summer weather, though I've knowed 'em do it in the early spring, just arter they come out from the winter sleep. But then they're mighty hungry. At this time o' year their bellies is full, and they haven't got no call to be fooling around where men is." He paused. "Say, you go back to the creek and tell Tod we'll be away maybe till dark, then come back to me. And bring my heavy rifle along."

Harry nodded, and went on his errand. He merely told Tod that they had got on the tracks of a large bear and were going to follow them up. Tod was very curious, but he quite realized that it was up to him to stay and take care of the boat.

WHEN Harry got back he could not see Bart. As he looked round he heard a sound of voices coming from a hut near by. He clambered down into it, and in the half darkness below found Bart talking to an Indian.

The Indian was an old, old man, bent, shrunk, and withered like a mummy. He was very clearly in a state of absolute panic.

Bart turned to Harry.

"I were right, Harry. It's a ghost bear, sure thing. This old chap, Tanana, he's been a-telling me. Seems the beast come here first last spring and took a old woman. Scared 'em all bad. Then he didn't show up again till a week ago, when he come on some chaps camping up on the tundra, catching salmon. Caught 'em at night, and killed one with a blow of his paw, and took him away and ate him. The others shot at him, but didn't do him no harm.

"Next thing, the bear walks into the village here two nights ago and catches a child. Last night he comes again and takes a woman. This broke their nerve, seemingly. Anyways, they've took to their canoes and cleared out to that there island you sees out in the Straits. Old Tanana, he were no use, and couldn't walk, so they either forgot him or left him a-purpose."

"Brutes!" said Harry indignantly.

"Aye, it may seem so to you. But life's hard up here, remember, and it don't do to judge by our standards," replied Bart gravely. "Anyways, I've fixed him up with some grub, and now it's up to you and me to go and hunt this here beast.

"We're not a-going to do any good till we got him," he continued, frowning. "The Injuns won't come back till he's dead, and, as I told you already, we got to have carriers. But it's sure a nuisance. Time's short and winter's a-coming, and we'd ought to be in good quarters afore the snow falls."

"Then the sooner we get him the better," agreed Harry. "He won't go far after he gets some of these under his hide," he added, as he handed over to Bart a couple of handfuls of the heavy .45 bore cartridges which were used in his rifle.

Bart said a word or two to old Tanana, which seemed to comfort him somewhat. Then he climbed up out of the damp and dreary little dug-out, and went back to the spot where they had first found the tracks of the bear.

They were plain as print, and Harry was struck again with wonder at their enormous size. They led out of the village in a northerly direction, and right across the bare, open tundra.

The going was very bad, indeed. The ground was a swamp, and they had to jump from turf to turf. Here and there the bear's huge paws had sunk a foot at least into the soft mud.

"Where can he have gone?" asked Harry presently. "I can't see any cover."

"For a fact, there isn't a lot. Most like he's down under a creek bank somewhere. Anyways, we'll find out. There's four or five hours' daylight still in front of us."

On and on they went. As they reached higher ground the travelling was better. Here the tundra was literally covered with berries. Some were purple, some scarlet. All were bursting with ripeness. You could have picked them by bushels.

"Most bears is satisfied with these and salmon," said Bart. "I never did know of one as took to killing men and women like this here brute."

They had gone some four miles inland when Harry saw in front of him the most extraordinary sight. It was a streak of gorgeous colouring some twenty feet wide lying across in front of them. The colours glowed and glistened as though a rainbow had been dropped from the sky to earth.

"What's that?" he demanded in amazement.

"That?" repeated Bart dryly. "Haven't you never seed salmon afore?"

"Salmon!" exclaimed Harry, and ran forward.

Bart was right. The brook—it was nothing more than a narrow creek—was absolutely packed with salmon. There were so many fish that they were actually crowding one another out of the water. But instead of being plain silver like fresh run fish, or red as English salmon become after they have been a month or two out of salt water, these glowed with the fairy colours of a jeweller's shop.

Harry positively gasped. He could hardly believe his eyes. But Bart took it quite as a matter of course.

"All the creeks is chock full this time o' year," he said. "Now's the time to get 'em afore they begins to get dark and die. But come on, younker. The tracks is fresh, and it's up to us to run that thar ghost bear down afore it's dark."

The tracks led on up the side of the creek, and presently they came upon a couple of dead salmon lying on the bank. Each had been bitten across the back.

"That's his work," said Bart. "He isn't a great ways off. I guess we'd better keep our eyes skinned."

"I hope we shall find him soon," returned Harry. "Looks to me as if fog was coming up."

Bart turned sharp round.

"Fog?" he repeated anxiously. "By gum, you're right, Harry! She's a-working up from the sea. Gee! I don't like the look of it."

Harry looked wonderingly at the big trapper. He could not quite understand why he was so disturbed. He was soon to know.

"I've a mind to go right back," began Bart, as he stared at the low-lying cloud of vapour which was blotting out the blue sea.

"But it won't reach us for ever so long," urged Harry. "And you say the bear can't be far off. We shall never get such a good chance again."

"That's so," allowed Bart. "Wal, I guess we'll follow up a bit farther, but not more'n a mile or so. You've not been in one o' these here fogs yet."

Bart walked on at a rapid pace. The ground was rising more sharply now, and, although there were no trees, there were patches of Arctic willow here and there.

The stream was no longer level with the tundra. It ran between banks which rose ten or a dozen feet above the sluggish water. These banks were of black earth, heavily cut by the spring floods, while here and there deep cracks or crevices ran back some distance into the surrounding country.

Harry noticed that Bart was now moving more cautiously, and that, as the trail of the bear passed around the outer ends of these cracks, he took a quick glance down into each. Putting two and two together, Harry gathered that the monster was probably hiding in one of them.

But the trail went on endlessly. More than once Bart glanced back anxiously at the veil of fog, which was now beginning to drift inland. Bart had become very silent, and was clearly uneasy.

Suddenly he pulled up short. Harry found him standing on the edge of a cleft much wider and deeper than any they had yet seen. Bart was staring fixedly down into the depths of it.

"He's here, Harry," he said in a low voice, and Harry felt a queer thrill as he noticed the huge paw marks clearly marked on the steep slope descending into the ravine.

Bart opened the breech of his rifle, and saw that a cartridge was in position.

"You keep behind me, Harry," he whispered. "Don't you pass me, and don't you try to shoot onless I gives the word. You get me?"

Harry nodded.

The bear's spoor led down the extreme landward end of the ravine. The ravine itself was about two hundred feet long, and at its deepest end, where it opened on the river, its depth was nearly twenty feet. The banks of black, peaty-looking earth were almost perpendicular.

"I don't see him anywhere," whispered back Harry.

"Not likely as you would. He's lying up in some hollow under the bank." He gave Harry a sharp look. "Not scared, eh, lad?"

"No," replied Harry quickly.

Bart nodded.

"Come right along, then," he said, and started down into the ravine.

By this time clouds had hidden the sun, and down at the bottom of the chasm it was very gloomy. Bart walked cautiously. He had his forefinger on the trigger of his rifle.

Harry, moving like a shadow behind, began to realize that his heart was thumping. As a matter of fact, it was the first time he had ever been bear hunting, and this, after all, was not any ordinary bear. The tracks that showed so plainly in the smooth, black peat were plain proof of its gigantic size.

They came to the deepest part of the ravine. In front Harry could see the water of the creek gliding past, black, smooth, and oily. The place was extraordinarily and uncannily silent.

Bart stopped. He did not speak, but pointed to the black mouth of a hole in the bank to the left. The huge footprints led straight into the hole, but they did not emerge again.

Harry nodded.

Bart took a small electric torch from his pocket and handed it to Harry. Harry understood, and, switching it on, directed its rays into the interior of the low-roofed passage.

Bart stooped down. He was quite still for some seconds. Then he straightened his tall figure again.

"Can't see nothing," he whispered.

"No more can I," replied Harry.

"Hold the light, I'm a-going in."

It was close quarters for Bart's giant frame. He had to bend nearly double. Harry waited till he was well inside, then followed. The clear white light of the torch flung Bart's shadow gigantic on the sticky clay floor of the cave. The place had a curious sour smell, which caught Harry's throat. His heart was pounding so that he could almost hear it. But he was steady enough, all the same.

Bart went step by step. It was clear that he fully expected the bear to attack. Yet there was no sound—no sign of the monster.

"A ghost bear," the Indian had called the creature. Harry began to wonder if it really had the power of making itself invisible.

Twenty feet in, and the cave bent sharply to the right. Bart peered cautiously round the curve and Harry heard him give vent to a sort of explosive gasp.

"Fooled us!" he exclaimed angrily.

"The beggar's fooled us, Harry."

Harry put his head round the corner, and at once understood. The cave had a second entrance which opened on the creek. The bear had simply walked out of it and vanished.

When Bart and Harry got out they found a regular path leading at a steep slope up the bank of the creek. It was deeply scored by the huge claws of the monster.

They followed it to the top, and found themselves back on the open tundra.

Bart looked round.

"Thar's the fog a-coming," he grumbled. "A nice job we'll have a-getting back through it."

Harry was not listening, but staring fixedly across the tundra.

"What's that?" he asked sharply, pointing as he spoke.

Bart looked.

"By gum!" he murmured. "It's old Mister Bear!"

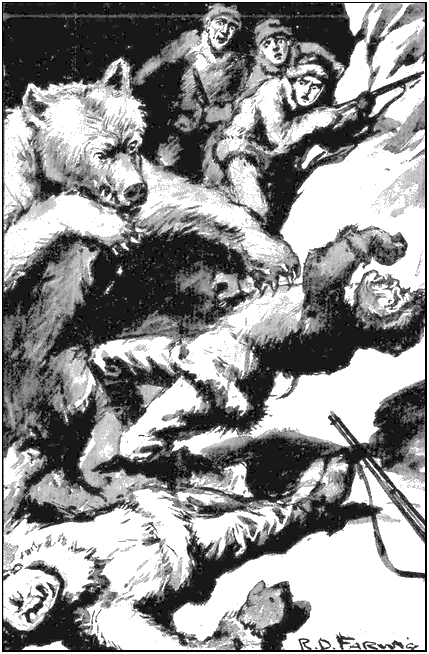

ALREADY the fog wreaths were spreading thinly over the desolate land, and in the queer half light the form of the ghost bear loomed gigantic, like some monster of the early ages of the earth. He stood on a little knoll somewhat back from the creek, and the lower part of his shaggy form was hidden by a tiny thicket of dwarf willow. Yet they could see him plainly enough, and a terrifying sight he was.

"Gee, he's some bear!" Harry heard Bart murmur in his beard, as he raised his rifle and took quick but careful aim at the giant beast.

The bear had been looking straight at his human foes, but as Bart put the rifle lo his shoulder, he swung swiftly sideways, and started off.

Bart's forefinger tightened on the trigger, and the crash of the report went echoing away across the waste.

"Hit him!" cried Harry, as the great beast was seen to flinch. He gave a hoarse growl, and swung sideways.

"Scratched him; no more!" snapped Bart, who was evidently deeply annoyed.

The bear was now hidden behind the knoll, and Bart, snapping another cartridge into the breech, ran forward.

Before he could get a fresh sight of the bear, a thick roll of fog came swirling down, and hid him completely.

Bart's face, as he turned to Harry, wore a very serious expression.

"We've done it now," he said curtly.

"Lost him, you mean?"

"Aye; but he's not lost us, son. And a b'ar don't forgive very easy, not arter he's been tickled up like that."

"You mean he'll go for us?" asked Harry.

"Lay for us, most like," replied Bart grimly.

Harry pursed his lips in a dismayed whistle. Then his face cleared a little.

"But we can still track him," he suggested.

"Aye; but what's to prevent his making a circle and coming round behind us?"

"Good gracious, Bart! You don't mean he's cunning enough for that?"

"You don't know b'ars yet," said Bart briefly. He looked at the fast thickening fog. "We've got to get back, Harry, unless we wants to spend the night here in the open."

"What are we to do? Follow our own tracks back?"

Bart shook his head.

"Not safe, son. I guess we'll have to keep along close to the creek. That guards one side for us."

"All right; you know best," agreed Harry.

The creek wound in and out, and its banks in many places were so marshy as to be positively dangerous. And the feeling that that monstrous brute might be tracking them all this time hardly bore thinking about. Whenever Harry let his thoughts dwell upon it, he had a feeling as if ice-cold water were trickling down his spine.

Bart said little, but kept his rifle ready all the time, and now and then he stopped and looked round and listened. But they neither heard nor saw anything. All was swirling mist and silence.

The only sound that broke the utter stillness was the far-off thundering of the great fire mountain Bogoslav, which sounded like very distant cannonading, and which, as Bart had said, seemed only to make the hush of this great, silent land still more impressive.

The tramp seemed endless. Since sea and sky alike were shrouded from view, Harry could not tell where they were. He was only grateful that the daylight lasted. In darkness it would have been simply out of the question to travel across these endless morasses.

They had been walking for about an hour and a half, when Bart stopped short in his tracks, and stood as if frozen. He had faced half round to the left, and was staring at something which Harry at first could not see.

The fog thinned a little for a moment, and Harry caught a glimpse of something which, at first sight, appeared to be no more than a clump of bush. But as he watched it, he distinctly saw it move.

A thrill shot through every vein. It was the bear.

Harry saw Bart raise his rifle, watched him take careful aim. He waited, breathless, and though it was really only a matter of seconds, it seemed like minutes before the trigger fell.

With the sharp report came a deep, grunting roar. The bear reared upwards, waving its great paws in the air. Then over it went, to fall with a heavy thud.

"Got him! Splendid!" cried Harry, in delight, and as Bart ran forward, he followed.

By the time they reached the spot, the great beast was motionless.

"This is great!" cried Harry again. "Dead as a door-nail. Now our troubles are over at last."

Bart had taken one look at the bear. Now he turned to Harry, and there was a strange expression on his face.

"Don't you be too sure, young 'un. If you asks me, they've only just begun."

"What do you mean?" demanded Harry. "You've got the bear all right."

"A bear," corrected Bart. "Not the bear. This here aren't the original varmint we been after. Look for yourself. It's all o' three sizes smaller."

Harry gasped.

"You're right. I see it now. It's not the ghost bear at all."

Bart stood looking down at the dead creature. His bullet had struck it behind the shoulder, and gone clean through its heart. If not the original ghost bear, even so, it was big enough, in all conscience.

After gazing at it for a moment or two, Bart took his hunting knife out of its sheath, stooped down, and set to work to take off the pelt.

"I say, Bart, won't that take a long time—skinning it, I mean?" asked Harry. "It's getting jolly near dark."

"Can't help that, Harry," replied Bart. "We got to take the hide back to Tassusak. The Indians will think it's the ghost bear all right, and we shall manage to get what porters we want."

IT was getting late in the afternoon on the sixth day after the adventure with the ghost bear when Bart Kinder, striding along with the two boys at the head of a string of a dozen heavily loaded Indians, pulled up, and turning, signed to the carriers to take a spell.

"Getting near, Bart, aren't we?" asked Tod.

"Mighty near. You see them two hills just ahead? The place I'm a-making for is a valley way down between 'em. I never been down there, but I've seed the place from up above, and set it away in my mind as the best winter quarters in this here country. There's timber and shelter and water, and it looked to me like there was game and fur for the taking. I reckon to camp close up this end to-night, and in the morning we'll push on and pick a place to build our shack."

"We've done jolly well so far," said Harry. "The weather's been simply topping, and we haven't seen a sign of that bear."

"Don't you go for to crow till you're out o' the wood, or, at any rate, safe in quarters," growled Bart.

Harry looked at him in surprise.

"But we're clear out of that brute's country, aren't we? Why, we're fifty miles inland."

"Shucks! What's fifty miles to a b'ar?" retorted Bart. "Specially a feller like that, as has got a sore back from my bullet, and a grudge as nothing won't satisfy but blood."

Harry did not answer, but presently, when they went on again, he moved close to Tod.

"Bart's loony about that bear," he whispered. "Surely he doesn't think a bear is going to follow us all over Alaska."

Tod shook his head.

"Don't ask me, Harry. I know nothing about bears. But I've a notion Bart does, and I'd hate to throw any doubt on what he tells us."

Harry grunted.

"If it's true, all I hope is that the beast doesn't show up before to-morrow. These Indians will run like hares if they get a glimpse of him. And it would take us three a month of Sundays to cart all this stuff even one day's journey."

"No use looking for trouble," replied Tod, shrugging his shoulders. "We've done jolly well so far. Let's hope we get through all right. I believe we shall."

For a time it looked as though Tod's hopes would be justified. The going was good, for they were now on high ground, far beyond the tundra bordering the coast. The weather was perfect, still and cloudless—a regular Indian summer.

The red sun was just dropping behind the tall peaks of the west when the party reached the spot for which Bart had been aiming, and the boys both pulled up short, with exclamations of wonder and delight.

They stood upon the upper edge of a tremendous slope, which dropped away for more than a thousand feet into an immense valley. To right and left rose splendid mountains, that to the east so high that its lofty peak was capped with everlasting snow. In the crimson light of the sunset this peak glowed like coral against the evening sky.

Beneath, the valley was heavily wooded with black pine. In the distance a river gleamed among the dark trees, and in open spaces caribou—which are really wild reindeer—grazed.

Bart watched the boys with a smile on his big, bearded face.

"Some valley, eh, boys?" he remarked.

"Great!" replied Harry. "Beats anything I could ever have imagined. It's perfectly wonderful, after all that bare, desolate country we've crossed."

"So perfectly sheltered, too," added Tod. "I should think we could laugh at blizzards once we're down there."

"Wal, I wouldn't say that," was Bart's quiet answer. "You kids haven't seen a real Arctic winter yet. But anyways, there's good cover, and I guess we can make ourselves snug enough down there. Come right along," he added. "I reckon to camp on the edge of them woods."

They moved on quickly. The Indians, Harry noticed, were not quite happy. Their stolid faces wore a slightly uneasy expression. He mentioned this to Bart.

"Nothing to worry about," replied the big man, with a smile. "Fact is, I don't suppose as any of 'em have ever seed trees afore. These here Siwash stick mighty close to the coast. This country's all new and strange to 'em."

"Are there any Indians inland?" inquired Harry.

"You bet. Stick Injuns, they calls 'em, jest because they lives in among the trees. But there isn't a lot of 'em, and what there is is peaceful enough onless they gets stirred up by bad whites and 'hootch.'"

"What's 'hootch'?" inquired Tod.

"Whisky," replied Bart curtly. "Good spirits is all right in their proper place, but as fer me, I'd hang the feller that sells his firewater to the Injun."

As they talked they were moving steadily down the slope, and just as the sun finally vanished behind the western mountain, reached the first group of trees.

Bart stopped and looked round.

"This here's good enough," he said. "Guess we'll camp right here."

The Indians had downed their packs and were preparing to light a fire when there was a crash in the timber beneath them, and Harry saw a huge antlered animal gallop swiftly across a glade below, and vanish in the woods beyond.

Before he could speak, Bart had snatched up his rifle and started off.

"A moose," he said briefly, as the boys joined him. "Aye, the Alaskan moose is the biggest deer in the world. Runs up to sixteen hundred in weight. Give us meat for a month if we can get that one. You keep well behind," he warned them.

Next minute they were in thick forest. There was no sign of the moose, but Bart kept on rapidly. He was following fast on its trail.

On and on they went, the tracks leading them up the right-hand or eastern slope. Luckily the Alaskan twilight is long, and there was still light left to shoot when they at last sighted the splendid creature standing quietly under a tree on the far side of a small glade.

Bart raised a warning hand. The boys stood like statues as he put his rifle to his shoulder. A moment of breathless suspense, then, as the rifle cracked, the moose sprang a yard into the air, and fell with a crash.

"Great shot!" exclaimed Tod, and all three ran forward together.

"Fat as butter," said Bart. "But, see here, kids. We haven't got light left to butcher it to-night. We'll have to sling the carcass fer the night, and cut it up in the morning. Harry, you go right along back to camp, and fetch three o' the carriers and a length o' rope. This here beast weighs nigh on three-quarters of a ton, and it's a-going to take six of us to sling it."

Harry nodded, and ran off. The distance to the camp was the best part of a mile, and it was very nearly dark when he reached it.

To his astonishment there was no fire burning, but when he had come near enough to see the stores lying on the ground, he got a worse shock still.

The Indians were gone.

He shouted. There was no reply.

"What on earth has become of them?" he murmured, and set himself to walk round and try to find their tracks.

It was too dark. He could not make out the footprints.

"This beats everything," he said half aloud.

The sound of his voice was echoed by a deep, hoarse, and most terrifying growl. Looking round, he saw a pair of eyes, pools of green fire, moving towards him from out of the thicket on to the lower edge of the glade.

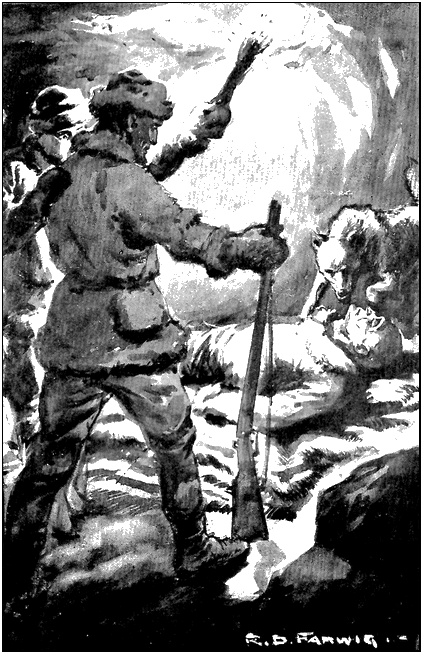

HARRY had not his gun. It was somewhere among the pile of stores. Where, he could not say exactly, and there was not light enough to see.

Nor was there time to search.

The bear—it was undoubtedly a bear—was charging out upon him.

For a moment Harry felt the cold fingers of despair clutching his heart; the next he was racing for the nearest tree.

He could not pick his tree, but, by the mercy of Providence, the one he reached had branches fairly near to the ground. He made a leap, caught the lowest, and swung himself up.

He was barely astride it when the bear reached the foot of the tree, and rearing its huge body to its full height, struck at him with a paw as thick as his own leg, and armed with chisel-like claws, each about five inches long.

Harry drew his legs up just in time to escape the tremendous blow, and the paw struck the trunk with a force that made the solid timber quiver, and ripped a yard of bark clean away.

The brute uttered a horrifying growl, which sent Harry scuttling upwards like a squirrel.

Now the grizzly—and the Kodiak bear belongs to the grizzly family—is not much of a tree climber, so Harry hoped and believed that he was safe for the moment.

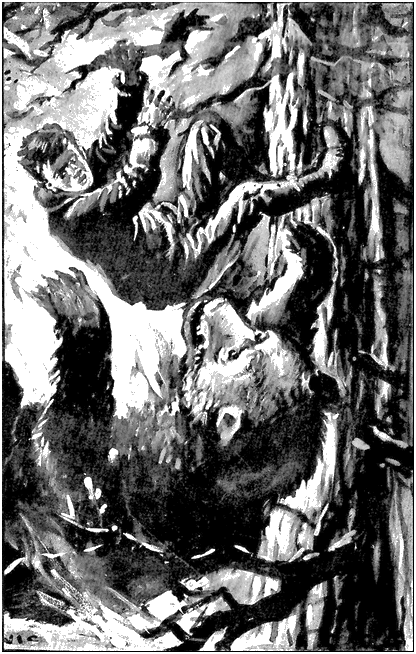

Imagine his horror when he felt the whole tree begin to shake, and looking down saw his fearful enemy start clawing up the trunk!

Its weight was so enormous that the tree, though a pine of very respectable size, shook like a sapling in a gale of wind.

Harry wasted no time, but went up like a lamplighter, and soon gained a perch some thirty feet above the ground. Here the branches were only just thick enough to bear his weight, and into the bargain were so dense that he could hardly force his way through them.

He paused and looked down. The monstrous bear was still working its ponderous way upward. Harry could see the green gleam of its vicious eyes between the close-growing branches. As it came higher, the tree bent and swayed in terrifying fashion.

Harry took a long breath and shouted at the very top of his voice. In the quiet night sounds carry a long way, and he had some hope that Bart and Tod might hear and come to the rescue.

But even if they did hear, the question was whether they would be in time. It would take them at least a quarter of an hour to arrive at the camp.

Again his heart sank as he felt that long before that the bear was bound to reach him and tear him down.

Up came the bear. Slowly, it is true, for the brute seemed to have doubts as to the strength of the branches. Several indeed cracked away under its vast weight with snapping sounds, like pistol shots. Harry realized that he must do something to stop it, otherwise his fate was sealed.

In times of extreme danger the mind works quickly. Harry remembered that, if he had no gun, at least he had a knife. It was one of those large Swedish sheath-knives, which all woodsmen carry.

He drew it quickly, and started clearing away the small branches all around him, so as to get free play for his arm. By the time he had done this the bear was only a few feet below. He could smell the harsh reek of it, its hot breath hissed up through the cold night air.

And now that he could see it at close quarters, and appreciate its enormous size, he had no longer any doubt but that it was the Ghost Bear itself and no other.

The monster paused, and the tree stopped swaying. Its glowing eyes were fixed upon Harry. Suddenly up shot that terrible paw.

Harry felt a jerk which nearly flung him from his perch. There was a ripping sound. The claws had just grazed the heel of his left boot, and nearly tore it off. But he had his left arm around the trunk, and it would have taken a good deal to loosen his grip.

Before the bear could strike again he made a swift downward slash. He felt the blade strike something. There was a hideous roar. There was light enough to see that he had gashed the bear's forehead. The blood from the wound had partially blinded the great beast. It slipped back, and for a moment Harry fancied was going to drop to the ground.

But not a bit of it. Recovering, the creature began clawing upwards again.

Harry was nearly desperate. The bear was now more savage than ever, and absolutely bent on his destruction. He glanced upwards, but saw that he could go no higher. That was definitely certain.

Like a flash another idea came to him. He had matches in his pocket. Fire—fire was the one thing which no wild animal could face.

Harry's fingers shook so that he could hardly open the box. But somehow he got hold of half a dozen matches, struck them all in a bunch, and flung them fizzing at the bear's head, which just then lurched forward, and the matches fell, not on its face, but on the back of its neck.

There was a little puff of flame as the hair sizzled up, and the great bear flinched and drew back for a moment. Then the matches went out.

Harry was almost in despair, but in spite of the desperate situation he still kept his head. There was something else in his pocket. His electric torch.

He pulled this out, flicked over the catch, and shot the light full into his enemy's eyes.

"Ah, you don't like that!" hissed Harry, as the bear shook its head, trying to escape the keen glare. For a moment Harry had real hopes that the beast was going to give up and clear out.

But again his hopes were doomed to disappointment. The great brute was mad with rage, and set upon revenge. The light now showed, beyond doubt, that it was indeed the Ghost Bear, for apart from its monstrous size, there was the scar of Bart's bullet on its left shoulder.

The idea that the creature had actually tracked them all this way up country filled Harry with a feeling of horror, almost of terror. It seemed incredible that any wild animal could have such a settled purpose of revenge.

Meantime, however, he was not idle, but was using the precious seconds to the best of his ability. Forcing himself upwards as far as he possibly could, he held the torch with one hand, and with the other broke away as many small dry twigs as he could get hold of. His idea was to try to light a bunch of these, and thrust them right into the Ghost Bear's face.

He got the twigs, but then came the question of lighting them. Since he had to keep his hold on the torch, he had not a hand to spare for striking a match.

And the worst of it was that the bear, finding that the light was not actually harming it, was getting over its first scare, and showing signs of making a fresh attack.

There was only one thing to do. Harry jammed the bunch of twigs into a crotch between two branches close in front of him. Still keeping the torch light directed into the bear's eyes, he got hold of his matchbox again, fished out a match, stuck the box sideways between his teeth, and so managed to strike the match.

The bear seemed to sense what he was about, and growled furiously. The reek of its hot breath made Harry feel sick. But he stuck to it, and managed to light his bunch of twigs.

They were dry as tinder, and full of resin. They flared up at once with a hot, scorching flame, so that Harry was forced to draw his head back.

It was at this particular instant that the bear, realizing apparently that this was its last chance, struck out again.

Once more it just missed Harry, but the shock of the blow knocked the blazing twigs out of their insecure hold, and sent them flying in every direction. Some fell on the bear, others were scattered through the branches.

There followed a crackle, a bright blaze, and Harry's heart was in his mouth as he saw that the tree itself had taken fire.

He must be burnt alive or eaten. That was the only choice left. With a yell he flung his torch straight into the bear's face, and followed it by a reckless sweep with his knife.

The blade struck home on the bear's nose, and bit deep into it. With a horrifying snarl the monster let go, and went sliding backwards through the blazing branches. Its claws scored the bark an inch deep all the way down, and it reached the ground with a thud like the dropping of a ton of coal.

Harry, scorched and half-blinded, tried to follow, but half- way down he, too, lost his hold, and came down flop on top of the bear.

Harry lost his hold and came down on top of the bear.

He rolled sideways off its vast furry bulk, and lay more than half stunned and quite helpless on the deep soft carpet of pine needles which covered the ground.

Now he gave himself up for lost. He was vaguely conscious that the bear was recovering, that it was on its feet again. Each instant he expected to feel a blow from its monstrous paw, or see its great jaws opening above him.

Instead, it swung its vast head twice from side to side, then turned and made off quickly down the slope.

Harry heard a shout in the distance; he tried to get up and answer. But everything went black before his eyes; he dropped back and lay still. And that was how Bart and Tod found him when they arrived, breathless with running, under the blazing pine.

Burning branches were falling in showers as they dragged him away. Tod ran for water, and they soon brought him round.

"The bear. It was the Ghost Bear," were his first words as he opened his eyes.

"I knowed it," said Bart briefly. "Seed his tracks. What happened? Did you fire the tree?"

Harry told his story. Bart nodded.

"I guess you had a mighty close call, Harry," he remarked gravely. "It was my fault. I'd ought to have thought of it afore sending you back."

"It was the fault of the Indians," Harry answered. "If they'd only lighted the fire as they were told to, it would have been all right. Where are they?"

"Up a tree, somewhere, I reckon," said Bart dryly. "I'm not a- going to worry about 'em, anyways. Tod, you and me will light a good fire. Then you stay here with Harry, and I'll go and get some o' that there moose meat."

"No, you've no need to worry. Mister Bear isn't a-going to try it on again to-night. He's got his bellyful for one day."

Tod, however, was taking no chances. He kept his rifle handy all the time as he lit the fire, and put the kettle on to boil. Harry, meantime, lay quietly in his blankets. He was not sorry to rest, for he had had a bad shake up.

Bart came back safely with the meat, and told them that he had covered up the carcass with branches and hoped it would be safe till morning. Then he started to roast some of the venison, and when it was cooked both the boys were ready to vow they had never eaten anything better.

They were just finishing when the Indians came creeping back, very scared and very sheepish. Bart, who talked their language, rated them well for their slackness, and told them that it was all their fault.

They did not resent it at all, but huddled near the fire, which they made up into a tremendous blaze. They were all terribly frightened.

IN spite of all he had been through, Harry slept well that night, and by morning was almost himself again. But Bart insisted upon him taking it easy, and left him in charge of the camp, while he himself and Tod and three Indians went to bring in the moose meat.

Since there was far too much to eat while fresh, the Indians were set to work to turn the meat into pemmican. It had to be cut into narrow strips, dried in the sun, then pounded.

Then Bart picked up his rifle.

"Tod," he said, "we're not a-going to have any peace so long as that blamed bear is loose across this valley. I guess we'll go and see if we can't finish the good work as Harry began last night. Savvy?"

It went sorely against the grain with Harry to be left behind. But he had sense enough to know that he was not yet fit for a long tramp. So he stayed to keep an eye on the Indians, while the others marched off on the track of the bear.

Harry noticed that the Indians kept very close to him. He noticed also that they watched him with a queer mixture of wonder and admiration. Though he did not know it, they looked on him as a sort of hero, in that he had come out alive in his battle with the Ghost Bear.

Not that Harry was paying much attention to them. He was listening for shots. In his heart he was hoping intensely that Bart would get the bear. This creature had really terrified him, and he was thinking that, if they failed to kill it, the brute would spoil the whole season for them. Not one of them would dare to go out alone.

The hours dragged by; the sun set, and still he heard nothing. Yet the day had been so still and fine that the sound of a rifle- shot would have carried three or four miles easily.

At last, just as dusk was beginning to close over the great lone land, two sharp reports in quick succession broke the stillness. They were followed by a distant shouting.

Harry sprang to his feet. Forgetting Bart's strict injunction to remain at the camp, he snatched up his rifle, and ran in the direction of the sounds.

The shots had come from the mountainside to the right of the valley, and it was in that direction that Harry ran. But he had not gone far before he pulled up short.

He had suddenly remembered that he had left the camp and the Indians unprotected, and that, too, against Bart's strict orders.

He stood, hesitating a moment, then his lips tightened.

"No, I've got to do what Bart said," he told himself, and walked back.

He had not gone half the distance when there came a shriek from the camp. He began to run again at the top of his pace.

He could not see what was happening, for the trees hid the glade in which the camp was pitched. Desperately anxious, he sprinted on, and burst into the opening just in time to see the Indians racing away up the hill, with the bear—the Ghost Bear itself—slumbering along in pursuit.

Harry was hardly able to believe his eyes. He had felt so certain that it was the bear at which the shots he had first heard had been fired. It seemed beyond belief that the brute should again invade their camp.

He pulled himself together, and, stopping, raised his rifle and fired.

But the bear was moving fast, and he himself was shaky with running. He made a clean miss. He fired a second time, and the bullet kicked up the dust a yard or two behind the great beast, ricochetted, and apparently struck the bear somewhere in the hind-quarters.

Such a wound would be painful, but not dangerous. It was enough, at any rate, to make bruin spin round. It saw Harry and paused.

Harry tried to steady himself for his third shot, but as he was in the very act of pressing the trigger the bear ducked its great head and swung round almost as quickly as a rabbit.

Again Harry's bullet went wide, and before he could fire again the shaggy monster dived in among the trees and vanished.

Harry was furious. So much so that, throwing all caution aside, he raced for the spot where his enemy had disappeared and plunged into the thicket after it.

He could see nothing. He stopped and listened, but there was not a sound. It came to him that the cunning beast was almost certainly close by, hidden probably behind a fallen log, and waiting for him to advance.

Prudence is sometimes the better part of valour, and this, Harry felt, was certainly one of those occasions. He retreated slowly, and, gaining the open, shouted to the shivering Indians to come back.

And they, well aware that their only chance of safety was close to the fire, crept up to it.

It was almost dark when Bart and Tod returned. They were carrying part of a caribou which they had killed, and were naturally anxious to know what Harry had been shooting at.

Harry, very much ashamed of himself, made open confession.

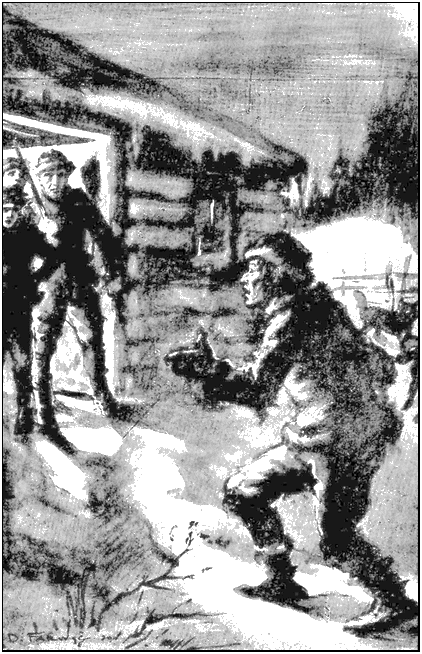

Bart shook his big head gravely.

"This beats all," he began. "That there bear must hev been a- watching the camp all day. He knowed he'd nothing to fear from the Injuns, so jest waited till you'd left to walk in and help himself to that there moose meat."

"It was all my fault," said Harry unhappily. "If I'd stuck to my post, I might have killed him."

"Not you, sonny," replied Bart. "It's as I tell you. Mister Bear, he'd never hev showed his nose so long as you was around. I tell you that feller knows a gun as well as you or I do. See the way he cleared when you began to shoot."

"It's a queer business altogether," put in Tod. "Seems to me that the beast can think almost like a man. He'll have one of those Indians pretty soon, even if he doesn't get one of us."

"That's certain sure," said Bart. "Tell you, boys, we got to get into winter quarters. Inside four walls we're safe enough. I reckon we'll move first thing in the morning, and pick our spot. It's going to be some place without a lot o' trees, too, let me tell you."

The boys agreed, and that evening the fire they made was a caution. There was, however, no sign of their enemy that night, nor in the morning, nor during their march down the valley.

About midday they reached a place of which Bart approved. It was a little rising ground near the river, and there were no thick trees within a couple of hundred yards. All the same, there was a good clump close by fit to split into logs, and that very afternoon they set to work to build.

The cabin Bart planned was the simplest thing possible; merely a one-roomed shack about twenty feet long by sixteen wide. The walls were of logs set by cutting deep notches in the ends, and made without a single nail. Such nails as they had were most precious, and were used only for door and windows.

It was wonderful what Bart could do with an axe. And the pace at which he worked was equally startling. He used the Indians to carry the logs and lift them into position, but he and the boys did all the actual work.

At the end of a week the cabin was finished. The outside was plastered with clay, the roof was thickly covered, first with branches, then with sods of earth, while the floor and fire-place alike were made of clay brought from the river.

The weather held wonderfully, and though there was frost at night, the days were warm and sunny. The best of it was that they saw nothing of their shaggy foe. Bart and the Indians, too, believed that the cunning brute was still watching them; but the boys began to hope that it was discouraged, and had gone off to look for winter quarters.

When the time came for the Indians to leave, they flatly refused to do so unless they were escorted out of the valley. There was no moving them from this decision, so Bart very unwillingly decided to give up a day to this job.

Tod was left in charge of the shack, and Harry went with Bart.

The wretched Indians were simply terrified. They kept as close as possible to the white men. But nothing happened, and just after midday they were clear of the valley, and carrying the presents which Bart had given them, set off rapidly across the open country.

"I'll bet they'll go twenty miles before they camp," said Bart, watching them. "But they needn't worry. That there bear is right here in the valley, and that's where he'll stay all winter."

"But don't bears lie up all through the cold?" asked Harry.

"That's so. They sleeps for about five months. But sleep time isn't come yet. Won't come till the weather gets real cold. No, sir, we got another month's trouble on our hands afore we feel safe like."

MUCH to their relief, they found Tod and the cabin all safe when they got back, and that night Bart told them about his plans for the immediate future.

Until the snow came they were to make every effort to lay in a big stock of meat.

"There's caribou round here all winter," he said, "and Arctic hare, and, mebbe, musk-ox. But we don't want to waste time a- hunting during the frost. We got to be setting of our traps and getting all the furs we can lay our hands on. Tomorrow we'll start out and try and find a bunch o' caribou. And ef we kin get another moose, so much the better."

Next morning they started early, but before leaving the cabin Bart was careful to close and fasten the strong shutter which covered the window. He also put in position two heavy bars which were fixed in slots across the door.

The boys made no remark; they knew the reason for these precautions without being told.

They went north into the depths of the valley, and the first thing they ran into was a big covey of pin-tail grouse. Rather to Harry's horror, Bart fired at them before they rose, killing eight.

Bart saw the look on Harry's face, and laughed rather grimly.

"I knows what you'd like to say, kid. But 'tisn't sport as we're out for. It's not hunting. And there isn't no store jest round the corner where we kin buy fresh cartridges. Just you mind that, both of you, and don't go wasting a shot ef you can help it."

There were plenty of hares hopping about, but these Bart would not let them fire at.

"The prairie chickens is all right, jest for a change of grub," he said, "but ef you boys want hares, you got to go and trap 'em."

Next, an Arctic fox ran across in front, but here again Bart restrained the boys. "His pelt isn't worth a half of what it'll be in six weeks' time," he told them. "And, anyways, a bullet isn't a-going to improve it, not for sale purposes."

It was nearly noon before they got on the track of caribou, and they followed the trail for two hours without seeing horn or hoof.

Bart began to look puzzled.

"It's real odd," he said. "Caribou is generally easy enough to fetch up with. But these hev been travelling fast. Something's scared 'em bad."

"What is it, Bart—the bear?" asked Harry.

Bart shook his head.

"Bear don't chase caribou. They knows better. Besides, where's the tracks?"

For some time they went on in silence. The bright morning had given way to a grey, dull afternoon. A fog was coming up.

"Guess we'll have to give up and go back," growled Bart. "Be too thick to see anything in another hour."

"The tracks seem perfectly fresh," said Tod. "Let's go as far as that next clump of trees."

Bart nodded and they moved on. But the fog rapidly thickened, and by the time they reached the trees it was quite clear that they could do no more shooting that afternoon.

Bart swung round, and took the trail home again. He was clearly worried by their failure to get any game worth having.

"Another day wasted," he grumbled. "And we haven't a lot o' time before the snow comes along."

They had covered about a mile of their homeward way when Bart stopped short and stood listening.

From far away in the fog came a faint snarling, yapping sound. For a moment or two all three stood perfectly silent.

Harry was the first to speak.

"Wolves," he said in a low voice.

"Wolves, I reckon," answered Bart in an equally low tone. "Doggone brutes! That's what's made them caribou so shy."

The cries came nearer. It was not a pleasant sound. There was something hideously wild and savage in the long-drawn howls, which came through the veil of grey vapour covering the whole valley.

"Makes one's blood run cold," whispered Harry to Tod.

"I know," returned Tod. "All I hope is that they'll stick to the caribou, and not start chivvying us."

Bart had stopped again, and there was a curiously puzzled look in his keen eyes.

"What's the matter, Bart?" asked Tod.

Bart shook himself like a big dog.

"Nothing," he answered curtly. "Come right along."

The pace at which he started off was a very rapid one, and gave the boys all they could do to keep up.

Presently the wild howlings diminished in volume. The pack seemed to be circling away again.

"I say, Bart," remarked Harry, "do these wolves ever tackle people?"

"Depends on the wolves," Bart answered shortly.

"How do you mean?"

"Whether they're hungry or not. These here timber-wolves is regular fiends, and in the frost-time there isn't anything as they won't go for."

"But not now. They can get plenty of game still, can't they?"

"Aye, it's too early in the season for them to be dangerous yet," agreed Bart. "But I tell you I hates 'em. There isn't no beast in the woods as I hates like I do a wolf."

He shivered slightly as he spoke—then after a pause went on:

"I laid up three days once in a hole in the rocks with about a hundred of 'em all around me. I was near froze to death and hungry as any wolf o' the lot. Ef it hadn't hev been for my pardner, Mike Cassidy, as come to look for me with two other chaps, I wouldn't be here to-day. I tell you I was all in when they lit a fire and thawed me out."

He fell silent again, and the three walked on for some time without speaking. The howls had died away altogether, and barring the distant murmur of the river the silence was so intense that it was positively oppressive.

Then quite suddenly the cries burst out again, and this time much nearer.