RGL e-Book CoverŠ

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book CoverŠ

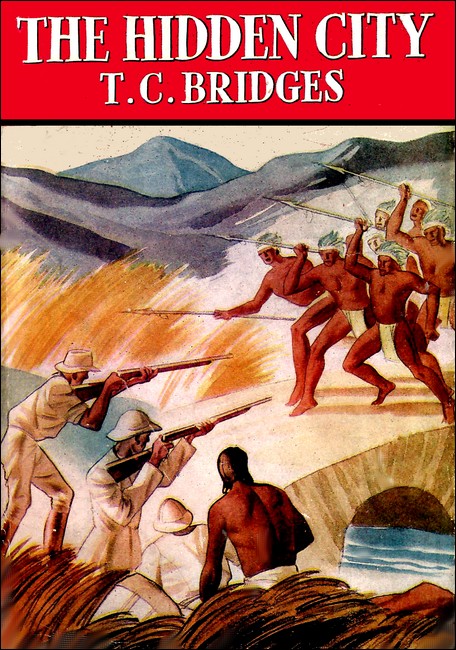

Dust Jacket of "The Hidden City," William Collins, London, 1923

Cover of "The Hidden City," William Collins, London, 1923

Title page of "The Hidden City"

FROM a chance meeting In the cosmopolitan capital of Bolivia between two young friends, an expedition is planned to find the lost city of the Incas, a city famous in legend for its abounding riches and dangers! Amyas Clayton had the map; it had been left to him by his father. Joe Cobb had the determination to succeed; but neither of them had enough money for such a hazardous undertaking. Whilst discussing their difficulties a Spanish half-breed steals up on them, and after confessing that he has overheard all, offers to finance the expedition in return for a share in the venture. Joe distrusts him from the start, but as there is no alternative the deal is made. Thus the trek begins and the reader's pulse will race to the thrills, adventure, treachery and dangers which confront the searchers. Do they ever reach the lost city? Could any white man hope to escape the anger of the Incas once their path is crossed? T.C. Bridges holds the answer in what is perhaps his most exciting story.

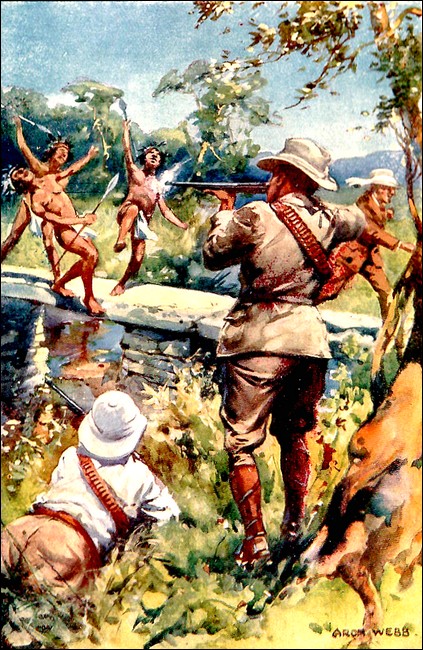

Frontispiece.

Two charges of shot knocked them off the bridge.

"first">THOUGH burnt nearly as brown as an Indian, the tall, good-looking youngster who walked slowly along the baking street of the city of La Paz was clearly English. His curly brown hair and dark blue eyes gave him an appearance different altogether from the black-haired Spaniards who glanced at him curiously as he passed.

For his part, young Amyas Clayton hardly noticed the Spaniards. He was evidently deep in thought, and by the look on his face not very cheerful thoughts, either.

So wrapped up was he that he never noticed a boy who was approaching from the opposite direction and who, though as different from Amyas as chalk from cheese, was just as unmistakably British.

The new-comer was short and square as Amyas was tall and slim. His eyes were gray and set rather wide apart, while his hair was so fair it was nearly white, and contrasted in the oddest way with his saddle-brown face and neck.

If Amyas failed to see the fair-haired boy, the latter at any rate had his eyes about him. He saw Amyas and pulled up short with a sharp exclamation of surprise.

The sound roused Amyas out of his trance and he, looking up, spotted the other.

'Joe!' he exclaimed. 'Joe Cobb!'

Joe strode up and seized Amyas by the hand.

'Joe it is, old son, and mighty pleased to see you.'

'I'll bet you're not half so glad as I am,' answered Amyas earnestly. 'If there's one chap I've been longing to see, it's you. I'd have written, only I hadn't a notion where you were.'

'I've been up at the silver mines at Bolivar. But the climate is beastly, and I'm fed up. I came down to see if your father had a job for me.'

Amyas drew a quick breath.

'Dad's dead,' he said simply.

Joe Cobb started back and stood staring at his friend.

'Dead?' he said at last. 'Mr Clayton dead?'

'His horse shied and went over the edge of the pass above the Rio Blanco,' Amyas answered quietly. 'It was a fortnight ago to- day.'

'My dear chap,' said Joe gently. 'I am sorry.'

'I knew you would be, Joe,' answered Amyas equally quietly. 'But Joe, we can't talk out here and I have a lot to say to you. Will you come to my rooms?'

'The house, you mean?'

Amyas shook his head.

'No,' he answered. 'I have had to give up the house. I am in rooms at the other end of the town.'

Joe Cobb stared hard at his friend. Now he noticed the pinched look of him, and drew his own conclusions.

'See here,' he said. 'I've had no dinner yet, and I'm beastly hungry. Let's go in there,' pointing to a nearby restaurant. 'We'll have a feed, if it's nothing but frijoles, and we can talk as we eat.'

Without waiting for Amyas's answer, he led the way straight into the place.

La Paz is the capital of Bolivia, and has some quite good shops and restaurants. Joe did the ordering and presently the pair were sitting down to quite a decent meal. Joe shrewdly noticed that Amyas was even hungrier than himself, and waited until the second course was brought before he began to ask questions.

'How's the business?' he asked.

Amyas shrugged his shoulders.

'Gone up,' he said. 'No, Joe, I don't believe for a moment dad knew how bad things were. You know he was always hopeful. But after he was gone, I found the books full of bad debts. To make a long story short, when I had settled up I found that I had just a hundred dollars left. My capital at present is eighty-seven dollars. That was one reason why I wanted to find you.'

'What—to get work up at Bolivar?'

'No.' Amyas lowered his voice. 'I wanted you to join me.'

Joe's surprise was plain, but he did not speak.

'Probably you think I'm crazy,' went on Amyas. 'Very likely you'll think I'm crazier still before I've finished.'

Joe's gray eyes widened a little.

'I'll tell you that when you have finished,' he answered. 'Go ahead. I want to know.'

'All right. Listen now. You remember that time when dad went with Captain Lee on an expedition down into the Hot Lands?'

'Yes, rather. Must have been a wonderful trip. But he was always a bit mysterious about it.'

'He had reason to be. He got on the track of something pretty big when he was down there. I never knew what it was until I went through his papers after his death. Then I found this.'

From his pocket Amyas took an envelope, and from this a sheet of common browny-white wrapping paper, which he unfolded and passed across to his friend.

Joe stared at it, frowning slightly.

'Seems to be a map,' he said presently.

'It is a map—or rather a chart drawn partly from his own observation, and partly from information given him by an old Indian cacique. Dad, you know, was a bit of a doctor. The old chap's daughter had been bitten by a coral snake. Dad cured her. In return the old Indian, whose name was Capac, told him the route to this place.'

As he spoke, Amyas put his finger on a spot upon the map.

'And what is the place?' demanded Joe.

Amyas glanced round. They were sitting at a table close to the side of the room and cut off from other tables by a large palm. There did not seem to be any one else within earshot.

'That,' he said in a low voice, 'is the lost city of the Incas.'

Joe drew a long breath.

'How do you know?'

'From this letter which dad wrote at the time and left in his desk. It is directed to me and on it he wrote, "Not to be opened until after my death." Read it.'

He passed the letter across, and Joe read it. He nodded.

'Yes,' he said. 'Your father evidently believed in it. But one thing puzzles me. Why didn't he go after it himself? Every one knows that it must be about the richest place in all the world.'

'Because of the dangers of the journey,' answered Amyas promptly. 'It's a fearful climate, a terrible country, and the natives are hostile to all strangers. As you know yourself, the Bolivian Government has sent one expedition after another down there to search for the Lost City, and not a man has ever come back alive.'

'And yet you think we could do it?

'I don't know. All I do know is that I'm game to chance it. We know the way. That's more than any of the others did.'

Joe nodded. 'That's true. At least, if the map can be trusted.'

He paused and thought awhile. 'All right, Amyas,' he said presently. 'It's a bid for fortune. A gamble of our lives against comfort for so long as we live, and everything that makes life worth while. I'm like you. There's no one to worry if I go under. My life is all I've got to risk, and I'm game to risk it. I'm your man.'

Amyas put out his hand. Joe took and gripped it. And so the bargain was sealed.

Joe studied the map again for a minute or two, then folded it up and restored it to Amyas.

'Now what about ways and means?' he asked briskly. 'We shall need a good canoe, at least four Indians, and enough stores for three or four months.'

'I've got my eighty-seven dollars,' said Amyas quickly.

'And I've got no more than fifty,' said Joe. 'And for a job like this a hundred and thirty-seven dollars is about as much use as a hundred and thirty-seven pence.'

Amyas's face went blank. 'I—I thought—' he began.

Joe, whose head was as sound as his square, solid body, cut him short.

'You'll have to get some one with money to back us,' he said. 'Do that, and I'll chip in and we'll carry the job through somehow.'

There was a rustle as some one brushed against the long leathery leaves of the palm behind them, and suddenly a man was standing beside their table. A tall, sparely built man of perhaps thirty-five, and in his way decidedly handsome. By his dark face and blue-black hair he was clearly of Spanish descent, yet the dark marks at the base of his nails and a slight discoloration of the whites of his eyes told of a touch of Indian blood.

For the rest he was dressed in correct white drill, and had a prosperous appearance. He bowed to the boys.

'Pardon me, seņores,' he said, speaking in excellent Spanish. 'I have been sitting at the next table, and quite unwittingly heard something of what you said. After that I am free to confess that I listened. If you will accept me as partner, I am willing to put up whatever money is necessary for this expedition. My name is Luiz Visega, and I can offer you any references you please as to my financial standing.'

TO say that the two boys were startled is putting it mildly. Neither of them had had the least idea that there was any one within listening distance and at first both were angry.

'How much have you heard?' demanded Amyas curtly.

'I heard you speak of the Lost City,' replied Visega quietly.

He shrugged his shoulders. 'You can hardly blame me for listening,' he went on with a smile. 'Every one in La Paz talks of the Lost City of the Incas.'

'Do you believe in it?' asked Joe Cobb.

'I should be foolish if I said I did not. Surely we all know that, after the Conquest, a number of the Incas disappeared into the unknown central country, and took with them great treasures of gold and silver and precious stones. I do not think that there is any one in Bolivia who does not believe that this hoard remains hidden in the depths of the wilderness. The proof of my own belief is that I am ready to risk my money in the search.'

Amyas and Joe exchanged glances. Then Joe spoke to Visega.

'My friend and I would like to discuss the matter,' he said. 'If you will kindly wait for us a few minutes we will let you hear our decision.'

Visega bowed again.

'By all means, senores. Permit me to withdraw.'

He moved away to the other side of the room, sat down and ordered coffee. The boys stayed where they were.

'What do you think, Joe?' asked Amyas anxiously. 'Is it good enough?'

'To go partners with that Dago? No, I don't think so. We want a white man.'

'And where are we to find one?' asked Amyas sharply.

'Blessed if I know,' said Joe.

'No more do I. And if we did find one willing to take the chances, probably he wouldn't have any money.'

'I bar travelling with Dagoes,' said Joe. 'And that fellow is not even a pukka Spaniard. I believe he's a Brazilian mestizo.'

'I'll allow that, Joe. But he's willing to put up the dollars. That's the main thing. There's another point to be considered. We are two to one. If he did play the fool, surely we could handle him between us.'

Joe looked thoughtful. 'There's something in what you say, Amyas. And I suppose it's something to get ahead without delay. If you're satisfied to take on the fellow, I shan't say "no."'

'Right!' replied Amyas, with evident relief. 'Then we'll get him over.'

'One minute,' said Joe, catching Amyas by the arm. 'He's not to see the map. Remember that.'

'I shouldn't think of showing it to him,' replied Amyas. 'By the bye, I suppose he will come in on regular shares?'

'That's only fair since he finds the money. Fetch him along then, and tell him our terms.'

Amyas brought Visega across, and for the next half-hour the three sat together, discussing the terms. Rather to the surprise of the two boys, Visega made no trouble about the conditions which they laid down. He professed to be perfectly willing to leave the guidance of the expedition to the two boys, and said he would be content with a third share of the profits.

Joe who was always businesslike called to the waiter for pen and ink and paper, and wrote out an agreement which all three signed.

At last Visega rose.

'The sooner we start, the better,' he said. 'I will set to work this very day. I know where to lay my hands on the men we shall need. I will engage them at once. And I will send a trusted man to Tucumanes to find a boat suitable for our purpose, and to lay in the stores which we shall require.'

Bowing once more, he left them.

Joe watched him go.

'Too civil by half,' he growled. 'I can't stick these coffee and milk gentlemen.'

'The trouble with you, Joe, is that you're a jolly sight too full of British prejudices,' said Amyas, with a laugh. 'After all, you can't deny that Visega is quite businesslike. The average Dago would have said 'Maņana,' and would have taken as much starting as a rabbit under a rock.'

'Well, we've made our beds and we must lie in them,' replied Joe. 'I've had my say, and I'm not going to grouse any more. Let's go back to your diggings, and see what we've got in the way of guns and grub.'

All the rest of that day and the next the two were busy. They put their cash together and bought clothes and good boots for the journey. They also purchased mosquito nets, and some necessary drugs, such as quinine. Each had a rifle, and they laid in a good store of cartridges.

On the second day after their meeting with Visega, they had a message from him, saying that all was prepared, and that he would be ready to start the next morning.

'Some hustler!' remarked Joe, in surprise. 'I never thought the fellow would be ready as soon as this.'

They sent word they would be ready, and spent the rest of the day packing up. At dawn next morning they met Visega. He had six mules ready, three to carry themselves and three more for the packs. They slipped out of the town almost before it was light, and if any one watched them go they no doubt thought that they were on a prospecting expedition. The Andes in that part of Bolivia are full of metals of different kinds.

La Paz lies very high, and the nights are always cold. But when the sun got well up the temperature rose, and that night they camped five thousand feet below their starting point in a much milder climate.

Their first destination was a place called Tucumanes, which lies on the Mojos River. This is a tributary of the Rio Grande, which in its turn runs into the great Madeira, one of the three main branches of the gigantic Amazon.

Most of the Bolivian rivers run towards the north-west, but the Mojos was an exception in that it ran to the south of west.

It took them four days' steady riding to make the landing on the Mojos, and here they found that, true to his promise, Visega had a boat ready, with six Indian boatmen. The boat was flat- bottomed and double-ended, a very necessary precaution in a river like this, swift, full of shoals and with ugly rapids here and there.

By this time they were out of the mountains, and in a climate that was almost tropical. It was exquisite country. The river ran through open, park-like forest, full of birds and monkeys.

It was dusk when they reached Tucumanes. Visega took up his quarter at the rancho from which the place gained its name, but the boys preferred their tent in the open.

They cooked their own supper and ate it by the firelight.

Supper over, Amyas stretched himself out comfortably on his blanket. 'Well, Joe,' he said, 'Visega has been as good as his word. The boat's here all right and so are the men.'

Joe looked up.

'And Visega—do you like him any better, Amyas?' he asked quietly.

Amyas considered a little.

'Can't say I do,' he confessed at last. 'But, after all, what does it matter, so long as he sticks to his agreement?'

'It matters a whole lot,' replied Joe, speaking very decidedly. 'Remember, this is the pushing off place. After this, we are clean off the map. For weeks and months to come we've got to pig it together—all in the same boat or all in the same tent. That's where the shoe is going to pinch, and that's how the rows are going to start. I tell you, old son, you and I will have to make up our minds to swallow a whole lot. We shall have to bite on the bullet, and keep still tongues. Visega's ways are not our ways.'

'Nor ours his, I dare say,' replied Amyas, a little sharply. 'Don't croak, Joe. I know we're in for a tough time. Let's hope it won't be made any worse by quarrels.'

'Not between you and me, anyhow,' said Joe, and quietly as he spoke Amyas knew he meant it.

'And now I'm going to turn in,' he ended. 'We must be up at four.'

SIX paddles rising and falling steadily drove the long narrow bateau down the sluggish current of the Mojos. It was a week since the party had left Tucumanes, and they were now in the heart of a tropic forest where white men were not seen once a year.

The blazing afternoon sun burnt fiercely on the bare shoulders of the Indians who wielded the paddles, and their brown skins glistened with sweat.

They had been travelling hard, with only one short break, since earliest dawn, and the men were deadly tired. One, a small man, who was nearest to the stern, was flagging badly. His worn muscles were stiffening. It was only by a great effort that he made his strokes.

Presently he missed one completely, and the boat swerved badly.

'Pull harder, dog!'

As the curt order left Visega's lips, he lifted the raw hide whip which he carried, and brought the cutting lash with cruel force across the shoulders of the offender. A thin red line streaked the man's bare skin, and drops of blood oozed from the cut flesh. With a groan he fell forward, the paddle slipping from his nerveless grasp.

Visega caught the paddle as it floated past, and lifted it back into the canoe. Then up went his whip for a second time.

Next Visega, in the stern, sat Amyas Clayton. Joe Cobb was in the bow.

Any one who had been watching Amyas when Visega first struck the Indian, would have noticed that he bit his lip, and that it was with evident difficulty that he had refrained from interfering. Now, suddenly his self-restraint slipped away, out shot his hand, and he seized Visega's arm.

'Steady!' he said sharply. 'Pablo is doing his best.'

Visega paused, and stared at Amyas. His eyes, black as jet, had a curious gleam.

'Are these Indians yours or mine, Seņor Clayton?' he asked. He did not raise his voice in the slightest, yet there was something so sinister in his tone and appearance that it made Amyas think of a deadly snake ready to strike.

But the boy held his ground.

'The men are in your employ,' he answered curtly. 'Still, I do not see that that fact gives you the right to flog them as you have been doing. You can take it from me that Cobb and I are not going to sit still and watch it, anyhow. What do you say, Joe?'

'I say that we've had quite enough of it,' said Joe stolidly.

Visega looked from one boy to the other. His eyes were deadly. But he lowered his whip.

'Very good,' he said. 'Since you Englishmen are so tender- hearted I will respect your prejudices.'

Very quietly he handed back the paddle to Pablo, who took it and set once more to his monotonous work. The ominous silence was broken only by the rise and fall of the dripping blades.

Every stroke took the little party farther and farther from civilization, deeper and deeper into the heart of the unknown. Already they were beyond surveyed country, and getting close to that vast tract of unexplored territory which lies between the tremendous swamp of Matto Grosso and the wild lands of Chiquitos.

The sun was dropping behind the distant crests of the towering Andes, the dimness of evening was falling over the thick forest that lined the banks of the stream, and the night chorus of frogs and crickets was breaking out on either side.

There was a little welcome coolness in the sultry air as the boat was beached, and the tired Indians carried its contents to the top of the steeply sloping bank.

The sound of axes fell through the still air, and presently the gloom was illuminated by the red glow of a camp fire. The two boys had their own tent. They pitched it a little apart from the rest, and both set to work to cut palmetto leaves to make their beds. They knew enough of camp life to be aware that ten minutes' labour of this kind makes all the difference between a good night's sleep and a bad one.

'Visega's in a filthy temper, Joe,' said Amyas, in a low voice.

Joe lifted a big bundle of rustling fronds.

'Small wonder, after the way you dressed him down,' he answered dryly.

Amyas started. 'What, didn't you agree with me?'

'Perfectly. You were absolutely right, Amyas.'

'What do you mean then?'

'Nothing against you, old son. Still I did make a remark about our being up against trouble, as much as a week ago.'

'I know you did,' said Amyas quickly. 'And you were right. But, Joe, I'd have stood anything myself. Only I couldn't stick the way he treats those Indians.'

'Of course you couldn't. And if you hadn't spoken up, I expect I should. Well, it's no use worrying. The fat's in the fire now all right, for a fellow like Visega can't bear being called down in front of his men. The fellow hates you like poison, Amyas. He's as dangerous as a pit viper. You'll have to keep your eyes skinned.'

'I'm doing that,' said Amyas, rather wearily. 'But I begin to wish I'd taken your advice in the beginning and turned Visega down at once.'

'It's too late to think of that,' Joe answered. 'We must just carry on. If the fellow plays up, I shan't make any bones about knocking him over the head and tying him up. Like you, I'm fed up with him.'

'Hush!' whispered Amyas. 'Here he is.'

The tall slim figure of the Brazilian was beside them, although neither had seen him come. Amyas had a flash of wonder as to how much he might have heard.

'Supper is ready, seņores,' he said. 'And I dare say you are ready for it.'

His voice was soft and quiet, he was actually smiling. Amyas glanced up at him sharply. He could not understand his sudden change of tone.

Visega understood the look. 'You are thinking that I owe you an apology, Seņor Clayton,' he said courteously. 'You are right. I do. I had no business to speak to you as I did. My only excuse is that I was worn out with the heat and the flies, and that my temper got the better of me.'

'It was not the way you spoke,' returned Amyas coldly. 'It was the way in which you treat those Indians.

Visega shrugged his shoulders.

'You do not understand,' he said plaintively. 'It is so difficult to make you English understand. You are accustomed to having white men under you, but these peons cannot be treated like white men. Words are useless. You must use blows. Blows are the only argument they understand. You must remember, please, it is what they and their fathers have been accustomed to for generations.'

'We haven't anyhow,' broke in Joe Cobb bluntly. 'And if we are going to travel together, you'll have to stop it, Seņor.'

Visega smiled indulgently. 'Very well,' he said. 'So long as we travel together, I will respect your wishes. But I warn you beforehand that we shall not get half the work out of the men.'

'We'll chance that,' said Joe curtly, and pushing through the bushes made his way to where the camp fire glowed red on the bank above the river. The other two followed, and took their seats close by the fire.

Supper cooked by one of the Indians was plain, but good. Broiled fish fresh from the river composed the main dish, and were eaten with flat cakes of maize meal baked on a flat stone. There was coffee without milk, but with plenty of sugar.

While they ate Visega talked away in quite friendly fashion, and Amyas chatted, too. Joe Cobb, however, was very silent. But Joe was never a very talkative person.

Supper over, the two boys went to their tent. They were tired with the long day's journey, and it was necessary to start again at earliest dawn. The great thing was to get on as fast as possible. No one could tell what difficulties they might run against later on, and the questions of provisions had always to be remembered. There was country between them and their destination where there was neither fish nor game.

'You were a bit rough on Visega, Joe,' remarked Amyas, as he made his preparations for the night.

'And you were a sight too civil,' retorted Joe.

'Why do you say that? He'd apologised.'

Joe snorted.

'He did say he was sorry,' insisted Amyas.

'Fat lot of sorrow he feels. He's only humbugging us. But let it go at that. I'm as sleepy as a boiled owl.'

'So am I,' yawned Amyas. 'Can't keep my eyes open. Good-night, Joe.'

There was no reply. Joe was already asleep. Amyas stretched himself on his comfortable bed of leaves, and in less time than it takes to tell it, had followed his chum's example.

* * * * *

What roused Amyas was the sun shining full in his face through the open flap of the tent. His head was aching oddly, and he felt dull and stupid. He lay still for some minutes trying to think, yet not feeling equal to it. Then all of a sudden he realised that it must be very late, and he sat up with a jerk.

'Lazy beggars!' he said, apostrophising the Indians. 'We ought to have been off ever so long ago. Joe, I say! Joe!'

Joe, lying close beside him, stirred and opened his eyes.

'Hallo!' he said thickly. 'What's the matter? He raised his hand to his forehead, and rose slowly to a sitting position. 'I say, I've got a thick head,' he continued. 'Must have had a touch of the sun yesterday.'

'So have I,' said Amyas. 'My head feels like a lump of lead, and I've got a poisonous taste in my mouth. And look at the sun. It's an hour up at least.'

As he spoke he scrambled to his feet, but for a moment stood swaying dizzily.

'What's the matter with me?' he asked hoarsely. 'I feel rotten.'

Joe's answer was to jump up much more quickly than Amyas and plunge headlong through the slight screen of bush which separated their tent from that of Visega.

Amyas following him more slowly, heard Joe give vent to a hoarse cry.

'What's wrong?' he cried in alarm. His first impression was that Joe must have been struck by one of those horrible water vipers which infest parts of these low-lying jungles.

Joe turned, and Amyas saw that his friend's face was oddly white under its tan, while his eyes held an expression which Amyas had never before seen in them.

'They're gone,' said Joe hoarsely.

'Gone!' repeated Amyas blankly. 'Who's gone?'

'Visega—the Indians—every one!'

Amyas brushed past Joe, and stepped out into the open by the river bank. He stared about him. There was the site of Visega's tent; there was the ashes of last night's fire. But that was all. The boat, too, was gone. The only living things besides Joe and himself were a couple of green parrots and a little gray monkey swinging from a branch high overhead.

He turned and faced Joe.

'What's it mean?' he asked.

'Doped,' Joe answered in one word.

Amyas's blue eyes blazed.

'The blackguard!' he cried. 'The utter sweep! Yes, that's it, Joe. There's not a doubt about it. Visega put a sleeping draught into our coffee last night, and slipped off before we woke. By this time he is miles away.'

He paused. 'But what did he do it for?' he went on in a puzzled tone. 'What could he hope to gain by it. He can't find the treasure alone. He hasn't got the map.'

'You'd best make sure,' cut in Joe curtly.

Amyas thrust his hand hastily into the breast pocket of his drill jacket. He drew it out empty. He gasped with dismay.

'Yes,' he groaned. 'He has got the map.'

There was complete silence for a moment. Even the level-headed Joe had nothing to say. But presently he pulled himself together.

'No use grousing,' he said. 'The damage is done. Let's see what the swab has left us.'

He began to search, and Amyas helped him.

It was useless. The Brazilian had left nothing behind. There was not so much as a slice of bacon, a pound of flour, or a spoonful of coffee. Every atom of the stores had been carried away.

'He seems to have done the job pretty thoroughly,' remarked Joe in his driest tone. 'He's even taken our rifles.

'Steady, Amyas!' he went on. 'No good getting in a bait. Lets see what we have got. There's our tent anyhow.'

Amyas pulled himself together. 'Yes,' he said quite quietly 'there's the tent, our blankets and mosquito net. We've got our watches, a compass, and our hunting knives. And here are two tins of matches. But the guns are gone.'

Joe put his hand into his pocket and pulled out a small automatic pistol. 'I've still got something to shoot with,' he remarked.

Amyas's face brightened a little.

'What luck! Where did you get that?'

'I've carried it all the time, old chap. You see I never did trust Visega.'

The gray monkey still sat on his bough. Joe raised the pistol fired quickly, and the animal shot through the head came tumbling down, stone dead.

'There's our breakfast anyhow,' said Joe.

AMYAS finished his portion of roast monkey, and flung the bone away.

'What do you think, Joe?' he asked. 'Is there any chance of catching up with Visega if we chase him?'

Joe shook his head.

'Not a dog's chance,' he answered. 'Even if we had a light canoe, I doubt if we could do it, for you may be quite sure he is shoving on for all he is worth. As for travelling along the bank of the river, I doubt if we can average a mile an hour. You can just put any idea of chasing the blighter out of your head altogether.'

'Then what's to be done? Are we to chuck it all and go back again?'

'That's just what I'm trying to make up my mind about. I fancy we are all of two hundred miles from our starting point. Even if we averaged ten miles a day, it would take us three weeks. And that's conditional on our not being mopped up by Indians or anacondas on our way.'

The two sat silent a while. Amyas was frowning slightly. He seemed to be thinking hard. At last he looked up.

'Joe, I had a good look at the map yesterday, and I remember there was a hill marked close to the river on this side and not very far away. Beyond, the ground was marked "open." What do you say to trying to find that hill? From the top we might be able to see where we are.'

'But we know that already,' replied Joe.

'In a way we do. What I was thinking was that there might be Indians in the open country, and if we could get a canoe out of them and perhaps some dried meat we might carry on even now. I do hate the idea of leaving that coffee coloured sweep to carry on and bag our treasure.'

Joe nodded. 'Same here, old son. It sounds a bit thin to me, but I'm game. Carry on.'

Without another word he got up and began to make up their goods into two equal packs.

Another ten minutes, and they had left the site of the deserted camp and plunged into the heart of the tropical forest.

It was thick as a hedge, and even where the undergrowth was not so close their way was barred by long tough lianas or creepers. These were tough as rope and varied from the thickness of string up to that of a ship's cable. The ground beneath was damp and rotten, and the pair were forced to keep their eyes open for snakes. The heat was terrific, and the worst of it was that down in these leaf-walled depths there was not a breath of air moving. To add to their troubles, clouds of insects hung around their heads and bit and stung venomously.

They didn't talk much. They needed all their breath for getting on. But both did a good deal of thinking, and both could not help but realise the desperate nature of their position and how extremely unlikely it was that either of them would survive many days of this sort of thing.

For three long hours they struggled onwards, then when the sun had already passed its meridian stopped by a little spring, drank some water, and ate the remains of their cold monkey. Amyas longed for a little salt, but Joe's chief desire—though he kept it to himself—was for a bit of bread.

'Don't see anything of your hill yet,' said Joe.

'I don't suppose we shall see it at all until we get to it,' replied Amyas. 'The trees cut off everything.'

He was right. They saw no hill, but about three o'clock found that the ground was beginning to slope upwards. Even though they had little to hope from climbing the hill, the rise put fresh heart into them and they quickened their pace.

Up and up they went, and as the slope grew steeper the jungle became less dense, and the walking so much the easier.

Still they climbed. They came to an open glade, and a couple of small deer dashed away.

Joe watched them regretfully. 'We could have done with one of those for supper,' he remarked.

Amyas did not answer. It seemed to him that supper was highly unlikely to materialise at all. There would be no monkeys at this height.

The forest opened out more and more, and not only that, but the air became decidedly cooler, and the insects were less of a plague. Then all of a sudden the woods broke away altogether and they found themselves on grass almost like that of an English park, and quite close to the ridge of the hill.

Tired as they were, both started at a trot.

Amyas, with his long legs, gained a little. Joe, a little behind, saw his friend suddenly pull up sharp, and stand stock- still. He ran forward, and reaching Amyas found him standing on the brink of a slope so steep it was almost a precipice.

Below—more than five hundred feet below—was a great bowl-shaped valley miles across. It was beautiful open ground with clumps of splendid trees scattered over it. Here and there pools of water shone red in the glow of the setting sun.

'Phew, this is the jumping-off place,' said Joe.

'It looks good to me,' replied Amyas cheerfully. 'Lots of game, and there are probably fish in those pools. I've got a line and some hooks in my pocket. Let's scramble down and see if we can get some for supper.'

But Joe stood still. 'Wait a bit,' he said. 'We climbed up here to get a view. Let's see all we can before we go on down.'

'I'd almost forgotten,' said Amyas quickly. 'Yes, we must get our bearings. There's the river.'

As he spoke he pointed to the right—that is to the south, where the river, like a golden snake, coiled in wild curves through the forest. From this height they could see miles and miles of it until it vanished far away to the east in the blue haze.

But the country was not all forest. In the distance it opened out into a vast llano or plain, bare except for small clumps of low-growing trees.

'The map was right,' said Amyas. 'There's the open country. I say, Joe, that won't be so bad to travel through.'

Joe did not answer. He had taken the field-glasses from their case and was focusing them on the distance. For quite a minute he stared through them, then handed them to Amyas.

'See anything?' he said. 'There by the last curve but one in the river.'

Again there was silence for some moments. Then Amyas gave a sharp exclamation.

'It's the boat!' he exclaimed. 'It's Visega.'

'Either that or an Indian canoe,' Joe answered quietly. 'The chances are that it's Visega.'

Amyas raised the glasses again. 'I can't be sure,' he said excitedly. 'They're too far off. I can't be certain.'

'Does it matter?' asked Joe quietly. 'Unless we had wings we could not catch them. Go slow, Amyas. It's not a mite of use to get cross.'

Amyas did not reply. But from the look on his face it was plain to Joe that he was very much upset. And Joe himself was sorry that he had called his chum's attention to the boat at all.

'Let's go down into your valley, old chap,' said Joe. 'As you said just now, it looks good to me.'

'All right,' replied Amyas flatly, and without another word followed Joe down the slope.

The hill-side was so steep that in places they had to scramble and swing from ledge to ledge. So far as Joe could see, the whole valley was surrounded by the same sort of cliffs. It seemed to him that the valley was probably the crater of some enormously ancient volcano.

But he did not worry his head much about this. What was much more interesting was that the place was full of game. Also, he thought he could see some durian trees in the distance. Durian or jack-fruit is excellent, and if there was fruit on the trees they would not starve.

It took them little more than half an hour to reach the floor of the valley, and though the sun was dropping behind the rim of the cliffs there was still nearly an hour of daylight before them.

Amyas had his eye on the nearest pool, but Joe was looking about him carefully.

'What's up?' asked Amyas.

'It struck me this was good country for Indians,' said Joe.

'And you're looking for signs?'

'I am, but I'm glad to say I don't see any.'

'I didn't know we were in the bad Indian country yet,' said Amyas.

'I wouldn't trust any of 'em,' replied Joe darkly. 'But I think we're all right here. Now let's see about supper.'

'There ought to be fish in that pond,' said Amyas eagerly. He was getting over the shock of seeing the boat. Though he had not Joe Cobb's stolid self-possession, there was pluck and to spare in Amyas's make up.

They went across to the pond. It was about half an acre in extent, shallow and so clear you could see the bottom for twenty yards out from the bank.

'There are fish,' exclaimed Amyas. 'Sun-perch. Whackers!'

True enough, the pond swarmed with fish. They were big, flat chaps, the size of a dinner plate, with large silvery scales. A sort of bream, most probably.'

Joe shook his head. 'It's too clear. They'll never take a bait.'

'Let's try, anyhow,' said Amyas, getting out his line.

Joe kicked over a rotten log and found some big white grubs. Amyas baited and threw out. But the result proved Joe right. The fish wouldn't look at the bait.

Joe took out his pistol. 'I hate to waste cartridges,' he said, 'but we've got to have some supper.'

Waiting till a fish came cruising close to the surface, he fired. The creature, not hit but stunned, by the impact of the bullet, floated to the top, and Amyas wading in secured him.

At the next shot Joe got two, and with a third cartridge a fourth very large one. They weighed nearly two pounds apiece.

'We shan't starve to-night,' said Joe in his dry way. 'Start a fire, Amyas, while I go and see whether there's any ripe fruit over on those durians.'

Amyas picked a good spot under a tree, lit a fire and cleaned and scaled the fish. He was grilling them over the hot coals when Joe returned, loaded.

'Jack-fruit—and bananas,' he observed.

'Topping!' cried Amyas. 'We shall do well to-night.'

They were half starved after their long day's tramp, and both, tucked in. The bananas in particular were a great treat, and made up for the lack of bread. They cooked some to go with the fish, and ate the riper ones raw. There was no need to stint themselves, for as Joe said there was heaps more where this came from.

At last they were satisfied, and as they were also tired out they unrolled the blankets without a word. Five minutes later they were both sound asleep.

Do ten hours' tramping through a tropical forest, then eat the first decent meal you have had for twenty-four hours. You will sleep as if you had taken a dose of chloral. It is doubtful whether Joe and Amyas did not sleep that night every bit as soundly as on the previous night after the drug which Visega had placed in their coffee.

But this time they were not to be allowed to have their sleep out. It was still pitch dark when Amyas woke to find himself, as he at first thought, in the strangling grip of a nightmare.

But the nightmare did not pass, and presently he realised that a man, a real man and a pretty hefty one, was kneeling on his chest.

IT was much too dark to see what the fellow looked like. All Amyas could tell was that he had very hard knees and a pair of very muscular hands.

At first Amyas struggled wildly. The only result was that the hands shifted to his throat and nearly choked him. So learning that resistance was useless, he lay quiet, and in a trice was turned over and found his hands tied fast, with some sort of fibrous rope, behind his back.

He became conscious that a similar struggle was going on close by, and realised that Joe was also a prisoner.

Presently he and Joe together were hauled out of their little tent into the open. There was no moon, but the stars were like lamps in the tropic sky above. They gave light sufficient to see that their captors, who numbered perhaps a score, were Indians.

Middle-sized men they were, but well built and muscular. They wore feather head-dresses common to almost all South American Indians, and very little else.

One who was evidently their leader gave a sharp command. Two men took hold of Amyas, one on each side, and two of Joe. Others rolled up the tent and blankets. Then the party set out at a sharp walk, making straight down the valley.

The surprise had been so complete that it took Amyas some moments to collect his thoughts. They had only gone a few steps before he heard Joe's voice.

'You all right, Amyas?'

'I'm all right. Who are these fellows?'

'Don't know any more than you?'

'Thought you said there were no Indians about, Joe.'

'I said there was no Indian sign,' returned Joe. 'But it was my fault. I brought 'em.'

'What on earth do you mean?'

'Shooting, you juggins,' replied Joe curtly; 'shooting those fish.'

'Phew, I hadn't thought of that. But it was my fault as much as yours. I ought to have remembered and warned you.'

'It's not a bit of use blaming ourselves or one another,' said Joe in his practical way. 'The mischief is done. What we have to think of is how to get out of it.'

'Got any ideas?' asked Amyas.

'Not one. We can't do anything now. That's one thing sure. We'll have to wait till they untie us.'

'I don't suppose they'll do that until they get us under cover,' said Amyas. 'Wish I knew where they were taking us.'

'We shall know soon enough,' answered Joe. 'I only hope it isn't far. They might have let us have our sleep out.'

At this point the leader of the Indians interfered. He seemed to think his prisoners had talked enough. Though the boys did not understand his language, there was no doubt in their minds as to the meaning of the sharp order he barked out. They went on in silence.

For more than two hours their captors hurried them along at the same sharp pace. If Amyas had not been so bitterly weary and sick at heart he would have enjoyed the beauties of that night march, with the great stars burning in the dark vault above and their reflections gleaming in the many small ponds and lakes which dotted the bottom of the deep valley.

At last Amyas realised that the ground was rising a little, and next he became conscious that straight in front a black line of cliffs cut the night sky. Being unable to consult his compass, he was not sure in what direction they had come, but it was clear they were approaching either the end or one side of the valley.

Still they went on until they were close under the cliffs. These were as high and even steeper than those down which he and Joe had made their way. So far as he could see in the starlight, Amyas thought they must be nearly perpendicular.

The leader of the Indians pulled up, and Amyas saw that a palisade barred the way. It was about eight feet high and made of bamboos woven tightly together.

The man gave a peculiar cry, and at once a gate was opened. A regular guard was at the gate. These men stood silent as bronze statues while the others entered. They did not seem to feel the slightest curiosity as to the prisoners.

Amyas and Joe found themselves in a stockaded village built on a slight rising ground close to, but not quite under the cliffs. The houses were little more than huts. They were dome-shaped, about eight or nine feet high and made, like the palisade, of woven canes plastered with earth.

No one was about; so far as any sign of life went the place might have been absolutely deserted, while a deathly silence brooded over the village.

The boys were marched to an open space in the centre of the village and taken to the door of a hut. The leader signed to them to enter and they did so. He came after them and untied their hands, then left the hut.

At once two men set to work to fasten up the entrance, which they did by lacing stout canes across it. Then they silently faded away and the boys were left to themselves.

'Uncanny sort of show!' remarked Joe.

'They don't waste words. That's one thing sure,' said Amyas.

Joe was groping around in the gloom. 'They've given us a bed anyhow,' he said. 'There's a bunch of grass here against the wall. Let's finish out our sleep. We shall feel more fit to tackle what's before us in the morning.'

Amyas agreed. He was too tired to think. So the pair lay down side by side, and were asleep almost at once.

The sun was well up before they were roused by some one at the entrance. It was an unpleasant looking old woman carrying two wooden bowls of mealie porridge which she thrust through an opening in the barricaded door.

'Thanks, old dear,' said Joe, as he took his portion. 'At any rate they don't mean to starve us,' he went on as he set to work hungrily on the stuff.

'I wish we knew who they are or what they want with us,' said Amyas uneasily.

Joe shrugged his shoulders. 'We shall find out soon enough. The only thing is to sit tight, and take our chance when it comes.'

'What chance have we got against a crowd like this?' demanded Amyas.

'Our chances do look a bit slim,' allowed Joe. 'Still there's one good one left.' Slipping his hand into an inner pocket, he pulled out the little automatic. 'They didn't find this,' he said, with a chuckle. 'They may know about guns, but I rather fancy a toy like this is new to them. If it comes to the worst I can do in a few of the swine.'

Joe's stolid cheerfulness put fresh heart into Amyas, and the two finished their food and felt much the better for it.

So far, no one but the old woman had come near them, and the village remained as quiet as it had been on the previous night. In spite of the brilliant sunshine there was something ominous about the silence that brooded over the place. Not even a child cried or a dog barked.

The boys waited as patiently as they could, but it was nearly eleven before anything happened. Then at last a guard of about a dozen men came towards the hut. They took down the barricade, and their leader motioned to the boys to come out.

It was a relief to get outside the stuffy hut, and both were glad to be in the fresh air. The guard surrounded them and they were led off.

As they passed through the village the street was empty, but they soon learnt the reason. They were led out into an open space between the village and the cliffs, and here at least three hundred people were standing in a broad crescent, facing the cliff.

At the foot of the cliff was a raised platform built of great blocks of reddish stone. The masonry was very ancient, and must have been built by some long forgotten race. Certainly these Indians could never have tackled any such work.

At the back of the platform was a flight of steps carved in the living rock and leading in zigzags right up the cliff. Though the great steps were broken away in many places, and worn by centuries of sun and rain, they formed a most impressive and wonderful stairway. The odd thing was that they did not reach quite to the top of the cliff, but ended some way below it in what appeared to be a cave mouth. The cave or passage was guarded on each side by an ugly-looking stone idol with a large round face, and a sort of frill around his head.

In the middle of the platform, and straight in front of the foot of the stairway was a similar image, only very much larger, and in front of him was a stone table about seven feet long and thirty inches high.

Amyas took all this in at a mere glance. What riveted the attention of Joe and himself was the man who sat in a stone chair at the head or east end of the stone table.

He was an Indian. You could tell that from the copper colour of his skin. For the rest, he did not in any way resemble the remainder of the tribe. In the first place he was a head taller than any of them, and while their faces were hairless he had a magnificent beard. He had a fine face with a perfectly straight nose, but his eyes gave Amyas shivers. They were hard and pitiless as cold steel.

One more point in which he differed from the rest was that he was wearing a long, bright, yellow robe, and had on his head a kind of gold crown with spike-like rays sticking out all round.

'That's the cacique,' said Joe to Amyas. 'Fine-looking bird; isn't he?'

'Can't say I like the look of him,' returned Amyas. 'But I wouldn't mind having that head-dress of his.'

'No more would I. It's solid gold by the look of it.'

'And those are the rays of the sun sticking out all round if I'm not mistaken,' said Amyas.

Joe started the least little bit and Amyas, watching him, saw a queer look cross his face.

'What's the matter?' he demanded.

'Nothing. That is, I didn't notice it before, but, of course, you are right. He's a priest of the sun.'

'Does that make any difference?'

'A lot—to us,' replied Joe grimly. 'This is the autumn solstice, and the big festival of the sun worshippers.'

Amyas's quick brain caught Joe's meaning.

'I see,' he said quietly. 'We are to be the sacrifice.'

'It looks too much like it to be healthy,' replied Joe, with equal calm.

THE Incas of old worshipped the sun, and the cult has descended to many of the wild tribes who are descended not from the Incas themselves, but from the Indians whom they conquered.

And from the moment that Amyas realised that the golden crown worn by the chief was meant to represent the suns rays, neither he nor Joe had the faintest doubt but that they had fallen into the hands of one of these tribes.

As Joe said, the prospect was not a healthy one. Twice a year, in spring and autumn, the Indians offer sacrifice to the Sun God. Usually it is an animal, a llama or perhaps a goat. They rarely sacrifice one of their own people because, from various reasons, the tribes are falling off in numbers, consequently human beings are too valuable to spare. If a tribe gets below its proper numbers, the nearest swoops down on it, kills the men, and steal the women and children.

But when prisoners are taken, then comes the opportunity for a real big show. The boys had no longer the faintest doubt but that they were to figure as the principal characters on this occasion.

The people stood perfectly silent; as for the bearded chief, the idol itself was not more still and grim. He sat in his stone chair as if he was part of it.

Amyas moved restlessly.

'Steady, old son!' said Joe in his quietest tone. 'Don't make a fuss until they try to tie us. Then I'll get my gun to work, and you collar a spear from the first man down. We'll make a good end of it anyhow.'

Joe's calmness steadied Amyas.

'All right, Joe,' he answered, with a smile. 'We'll give 'em a sacrifice or two to go on with.'

The silence lasted for some minutes, and it was really a relief to Amyas when the priest at last rose, and after staring up at the sun for several seconds said something in a deep voice.

At his words the guards round the boys began to move forward. They did not lay hands on Joe or Amyas but simply moved them forward towards the platform in the centre of a hollow square.

'All right, Amyas,' said Joe in a low voice. 'The farther we are from the main bunch, the better. With any luck, we'll get his Nibbs himself.'

Broad, shallow steps led up to the platform. The boys went up them, and with their guards still around them, approached the altar. As they neared the great flat-topped block of stone, Amyas saw that its surface was coloured rusty red. There was no need to ask the cause of the tint.

The scene was distinctly impressive. The wide platform with its huge stone god seemed dwarfed by the towering cliffs behind. The sun, now very near the meridian, beat down hotly on the wide valley and on the silent actors in this strange and horrible ceremonial.

As he came up Amyas looked again at the priest. Never in his life had he seen such an utterly impassive face. Except for the cold, pitiless eyes of the man, it was hard to believe that he was human.

Without changing a muscle of his face, the priest began to speak. His voice was as big as himself. It tolled like a great bell, echoing back from the cliff.

'Wish I knew just what he was talking about,' said Joe.

He spoke to Amyas, but kept his eyes on the priest's face. 'I'll lay it's nothing nice, but I hardly like to plug him until I'm sure he means to slay us.'

'Yes, you'd better wait a bit,' answered Amyas.

The priest went on with his speech. It sounded like some sort of invocation. The boys stood perfectly still, but every nerve and muscle was tense. They were both ready for instant action.

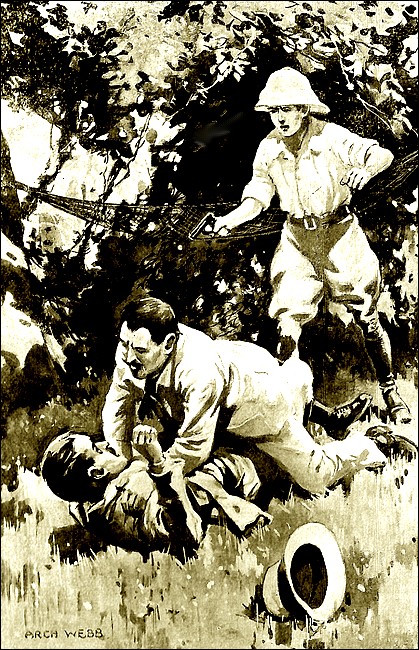

The priest suddenly raised both his great arms above his head. It was evidently a signal. As he did so Amyas and Joe were both seized from behind.

They had not known their guards were so close, but though taken by surprise they fought like wild cats.

Amyas lashed out with one heel, and one of the men holding him collapsed with a groan. At the same moment he heard Joe's pistol crack twice in rapid succession.

The second man who held him flung all his weight forward and bore him to the ground. Amyas struggled frantically, but the Indian was too strong for him, and he was flung forward on his face. He felt the man's sinewy fingers biting into the back of his neck.

Another crack, the Indian's grip loosened, and he fell across Amyas. In a flash Amyas scrambled from under him and sprang to his feet.

Another Indian was in the act of leaping at him, Amyas did not wait for him. He dashed in to meet him, and his fist caught the fellow right in the centre of his fierce face, and sent him crashing back on the pavement.

Remembering what Joe had said, he stooped swiftly and snatched up the man's spear.

'This way!' he heard Joe cry. 'Here, beside me!'

Joe was standing on the altar itself. Three dead Indians lay at its foot. Springing across their bodies Amyas reached Joe's side and, spear in hand, faced their enemies. His blood leaped in his veins. For the first time in his life he was fighting mad and ready to tackle the whole tribe, single-handed.

For their part, the Indians had drawn back. Joe's pistol, of which they had known nothing and which was evidently a new weapon to them, had scared them badly. For all that, they had not bolted, and those who had formed the guard stood no more than a score of paces away. They had the High Priest among them, and they glared sullenly at the two white boys.

'Let 'em have it, Joe,' cried Amyas. 'Shoot a few more, then let's go for them.'

'Don't be an ass,' snapped Joe. 'They'd swamp us in two ticks.' He glanced round as he spoke. 'If we could only get on to that stairway!' he muttered.

'We've got to do something pretty quick,' said Amyas. 'Those chaps behind are forming up. We'll get a volley of spears or arrows before you can say knife.'

He was right. The main body in the background were moving.

The men had separated out from the women, and nearly all of them had bows and arrows. Amyas saw them fitting the arrows to their strings.

One of them gave a shout, and at once the guard near the altar began to draw back, but still keeping their faces towards the boys.

'I told you so,' said Amyas swiftly. 'The guards are moving so as to give the others room to shoot. Now's our chance.'

'You're right. Bunk!' said Joe, and turning leaped off the altar and raced for the foot of the stairway.

Amyas followed.

The silence was broken by a roar from the priest. His mighty voice rolled like thunder.

Click! clack! The arrows whistled through the air, and struck the stone pavement all around the boys. And suddenly Amyas saw Joe falter and fall.

An arrow was through the calf of his leg.

'Go on, Amyas.' cried plucky Joe. 'Here's the pistol.'

Amyas snatched it from him, swung round, and protecting Joe with his own body began firing rapidly.

But the Indians were some way off. Three only fell. The rest then swept on in a dense mass.

The hammer clicked, the magazine was empty. Amyas dropped the useless weapon, snatched up the spear and went for the Indians like a bull at a gate.

The first man that met him went down, with the spear straight through him, the point sticking out six inches beyond his back. In his fall, he wrenched the weapon from Amyas's hands. Next instant the pack were on him, and he was down underneath an avalanche of naked, greasy bodies.

Something hit him heavily on the head and for the time he knew no more.

* * * * *

When Amyas came to his senses again he realised that there would be no more fighting. He was tied hand and foot, trussed up like a chicken ready for market.

He opened his eyes and found himself lying flat on his back on the altar stone. Joe, tied up like himself, was beside him.

Above them towered the priest, his huge arms upraised towards the sky and his great voice booming out in a sort of sing-song monotone.

Joe saw that Amyas's eyes were open.

'How are you, old chap?' he asked, and there was a tone in his voice which Amyas had never heard before.

'I'm all right, Joe. I say, we nearly did it, didn't we?'

'Near as a touch. If it hadn't been for that nick in my leg, we could have. I say Amyas, you ought to have left me and cleared.'

'Don't talk rot,' answered Amyas impatiently. Then suddenly he laughed. 'What's the good of arguing? We're gone coons this time, Joe. We shall get it where the chicken got the axe as soon as old Mumbo Jumbo has finished his incantations.'

'Wish I'd shot the old swine,' growled Joe. 'Hallo, he's finished. So long, old man.'

'Good-bye, Joe,' replied Amyas calmly. 'The only thing I'm sorry about is that Visega's got that map.'

'I've got a notion it won't do him any good,' said Joe. Then he stopped short. The giant priest had raised his right arm, and in his great gnarled fist he held a knife. It was shaped like a leaf and made not of steel but of burnished copper. The loose sleeve had slipped away from the priest's arm, and Amyas saw the big muscles writhe under the brown skin.

Oddly enough he was not at all afraid. He was only conscious of a hope that he would be the first victim, and not be left alive to see Joe's end.

He closed his eyes and waited.

A WHIRRING, rattling noise was in Amyas's ears. So far as he wished for anything, he wished for the blow to fall.

It did not fall, but the noise grew louder.

He opened his eyes again with an effort, and looked up at the tall priest. To his amazement, the giant's arm had fallen to his side. His jaw, too, had fallen, and somehow his whole face had changed, and instead of looking fiercely down at his victims, he was staring up into the sky, with an expression of terror, or rather awe.

Amyas instinctively looked up also. He gave a convulsive gasp.

'Joe!' he almost screamed, 'an aeroplane!'

An aeroplane it was. Madly impossible as it seemed, there was a good-sized biplane, coming through the air about five hundred feet up, and at a tremendous speed. Even as Amyas set eyes upon her, her pilot cut out, and the plane came swooping like a dropping pigeon towards the village.

Amyas managed to twist his head round to the left. The Indians had seen her, too. Every last one of them except the priest was flat on his face on the ground. There was a sharp tinkle. The knife had slipped out of the priest's hand and fallen to the pavement. Then he himself crumpled up and dropped upon his knees.

'They've got the wind up properly.'

It was Joe who spoke, and his tone was as calm and collected as ever.

'If only we weren't trussed up like this!' groaned Amyas.

'Sit tight, old man. Those chaps in the plane must have seen the whole show. I rather fancy they'll have us out of this before the niggers have got over their scare.'

She's down,' breathed Amyas.

The plane had come to earth on the open savanna just outside the village, and not two hundred yards away from the place of sacrifice.

The next two or three minutes were like hours to Amyas and perhaps to Joe, too. They were perfectly helpless, and from second to second it was on the cards that the priest might recover and complete the sacrifice.

But his scare held. He, of course, and his people were under the full impression that messengers of the Sun were descending from the sky—probably on some dreadful mission of vengeance.

At last—at long last booted feet clattered on the stone platform, and two men came striding rapidly towards the altar. The first was a man of Joe's build, but bigger. He was wearing full flying kit with goggles and a leather cap, and in his right fist was gripped a full-sized army revolver, one of those huge six-chambered weapons that carry a .45 bullet big enough to kill an elephant.

'White boys!' he shouted as he came up. 'I told you so, Professor.'

Whipping out a knife, he set to slashing at the ropes which tied Amyas.

His companion was up almost as quickly as he. The latter was nearly as tall as the priest, but thin as a rail. His face was gaunt and wrinkled, and the hair which showed under his cap was grizzled. But his eyes dark, bright, and snappy were like those of a young man.

'Say, Dick, we didn't come a mite too soon,' he remarked, in a high-pitched voice with a strong American accent, and with that he produced a knife as big as the other man's and had Joe free in a twinkling.

'You're just about right, sir,' said Joe, in his cool way. 'If you'd been about one minute later, we were gone coons.'

The Professor stooped swiftly and picked up the knife which the High Priest had let fall.

'Gee!' he exclaimed. 'A real sacrificial knife of hardened copper. Say, but this is some prize.'

Joe sat up.

'If you're anxious to keep it, sir, we'd better be moving. They're a tough lot, these Indians, and as soon as they get over their scare they're likely to make themselves unpleasant. We shot half a dozen of them, but they didn't panic worth a cent.'

'I guess you're right, young man,' said the tall American. 'And what do you recommend as the best course to pursue?'

'Well, sir, if your plane will carry us, we'd best shift right out of this valley, and quick about it.'

'She'd carry us right enough,' put in the man the professor had called Dick. 'The trouble is we're plumb out of petrol.'

Joe gave a low whistle.

'In that case, we'd best get right up those stairs,' he said.

'But all our stuff is in the old machine,' said Dick. 'You don't reckon to leave it all for these niggers.'

Joe considered a moment.

'No. That would be as good as signing our death warrant. Tell you what. Collar the priest here, tie him up, and we'll hold him as hostage for the behaviour of his people.'

'I reckon that's a right good idea,' said the Professor calmly. 'Get hold of him, Dick.'

Dick took a rope, made a loop in it, and dropped it over the big priest as coolly as if he was trussing a turkey.

'Get up, you murdering son of a gun!' he said, and jerked the giant to his feet. The latter was still too staggered by what he considered the miracle of the aeroplane to offer any resistance.

By this time Amyas was on his legs again, and was quickly examining Joe's wounded leg.

'Don't worry about that,' said Joe. 'It's nothing worth mentioning. Give me an arm and I can get along.'

'It's only a flesh wound, luckily,' said Amyas with relief. 'I'll just put a handkerchief round to stop the bleeding.'

This took but a moment. Then the four, with their prisoner, left the platform and made back towards the aeroplane.

The Indians had by this time recovered a little from their first panic. They were beginning to look about them. Their faces were sullen and angry. Superstition and rage struggled for mastery.

'Ugly looking lot o' swine,' remarked Dick.

'Dangerous, too,' said Amyas. 'The sooner we're away the better.'

'They won't do nothing to us—so long as we've got their high Jim-Jam,' replied Dick.

'I wouldn't trust them,' warned Amyas.

But they reached the aeroplane without interference, and Dick and the Professor began getting the stores out of her. Amyas helped to make them into three packs.

'Rotten to leave her,' said Joe, in his short way.

'Rotten it is,' agreed Dick, whose other name was Selby. 'She's a good little bird. But without petrol she's just junk and nothing else.'

'What on earth brought you here?' asked Amyas as he rolled up some cooking pots.

'The Professor here. He hunts buried cities and them sort of things.'

Amyas started slightly, but said nothing. This was no time for discussion.

They packed with desperate speed. Dick Selby, an extraordinarily competent person, seemed to know exactly what was necessary, and what they could dispense with Amyas was delighted to see two excellent rifles, a good shot gun, and heaps of cartridges. There was a quantity of tinned goods, but most of these they had to leave in order to pack flour, sugar, salt, and coffee.

The priest whom Selby had unceremoniously tied to the plane, stood glaring at them suddenly.

In a wonderfully short time they had three packs ready. Joe was not fit to carry anything. It would be all he could do to travel, unloaded. There was a nasty hole in his leg.

'I guess that'll do,' said Dick Selby, lifting his pack and settling it on his shoulders. 'What's the next move, mister?'

'Straight up those steps. That's the only way out so far as I can see,' replied Amyas.

'They don't reach the top. They end in a cave,' said Selby.

'Which most likely goes right through. Anyhow, it's our only chance,' Amyas told him.

'What do you say, Professor?' asked Selby.

'The cave, I guess,' said the Professor. 'It looks to be a right good chance.'

'We'd best be shifting,' put in Joe. 'These niggers look ugly. They're closing up on us.'

Joe was right. The Indians were recovering their courage, and sneaking sullenly nearer.

'Wait a jiff,' said Selby. 'I'll put the wind up 'em.'

'There's still a quart or two of juice in the tank,' he added, and as he spoke he switched on, then stood back and swung the propeller.

The engine was still hot. At once it began to fire. The rattle and roar of a 250 h.p. engine is loud enough in the air. On the ground there is something terrifying about it. And the wind from the propeller flattened the grass for yards.

'I told you so,' chuckled Selby, as the Indians, terrified, broke and bolted in every direction.

'Right, here's our chance,' remarked the Professor as he shouldered his pack, and picked up the shot gun.

'Once we're on the flight of stairs there, the natives won't have much chance to attack us.'

Leaving the engine crackling and roaring, the four walked steadily away towards the cliff. Amyas had his eyes on the Indians, but the Professor hardly seemed to notice them. All his attention was fixed on the stone platform and altar.

'I'd like mighty well to have had the chance to look over these remains,' he said regretfully. 'I guess they're pre-Inca by the look of them.'

'I reckon you'll find a heap more farther on, Professor,' Selby answered. 'If we don't want a skin full of spears it's up to us to get along sharp.'

'It's arrows we have to fear worse than spears,' said Amyas. 'Hallo, the petrol's run out.'

He was right. The roar of the engine had died out with startling suddenness. The quiet that settled over the scene was broken by a hoarse yell from the Indians.

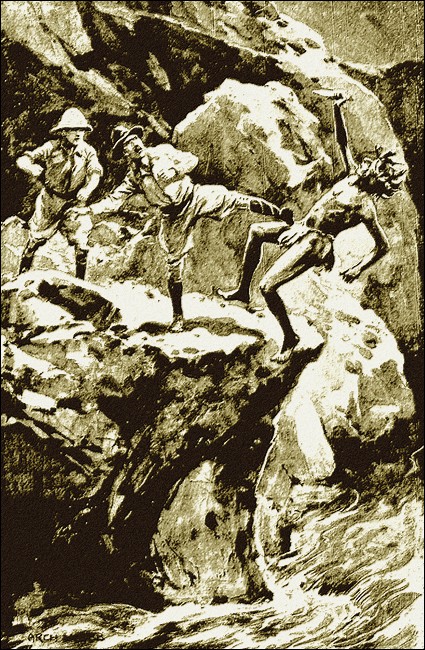

'They're coming,' said Joe, hobbling up the steps as last as his wounded leg allowed.

Coming they were. Gaining courage from the flight of their strange visitants, the whole mob had turned in pursuit. Arrows came whistling through the air, clicking sharply on the cliff face, and on the steps all around the fugitives.

Dick Selby faced round.

'Have to give 'em a volley, Professor. You boys push on a piece.'

Amyas gave Joe an arm, and helped him on up the stone stairs. The steps which were carved in the rock itself were so ancient that they had broken away in many places. Poor Joe was having a bad time getting up them. The wound in his leg, though not serious, was very painful, and the exertion made it bleed again. Crimson drops stained the gray surface of the steps.

Amyas, who was carrying a pack weighing at least fifty pounds, had all he could do to help his chum along. The heat was terrific, and big drops of perspiration streamed down his face.

Selby's rifle cracked, and its whip-like report was followed by the roar of the Professor's double barrel. The latter was loaded with buckshot, which did fearful execution upon the naked bodies of the Indians.

Six dropped, others fell back, wounded.

'That'll do for a bit,' said Selby calmly. 'Won't do to waste too many cartridges on the swine.' As he spoke he slung the rifle back over his shoulder, and taking hold of Joe's other arm began to help him onwards. He was enormously strong, and though his pack was the heaviest of the lot, was almost lifting Joe.

Before the Indians had recovered from the volley the white men were almost out of arrow shot, and more than half-way up to the cave-mouth.

'Doing very nicely, thank you,' said that iron man, Selby, and chuckled a little. 'If that there cave has a hole the other end, I guess we're all right.'

Whatever might be said of the Indians, they were at any rate not lacking in pluck. Almost at once they pressed on again to the foot of the steps. A regular cloud of arrows was discharged. But their targets were more than a hundred feet above them, and though one arrow actually struck Selby's pack and remained sticking in it, it did no harm. And every step took the party farther out of danger.

The dark entrance of the cave was now plainly visible, with its two ugly looking stone guardians. Two minutes more, and the little party reached the narrow platform in front of it, and dived for shelter into its mouth.

'I don't see no way through,' said Selby.

'You could hardly expect to,' replied Amyas. 'If there's a passage it must slope up pretty steeply.'

The Professor cut in.

'I guess we'd better find out, and quick, too. You—I haven't the pleasure of knowing what your name is—'

'Amyas Clayton, sir,' said Amyas. 'This is Joe Cobb.'

The Professor bowed. 'I'm obliged. My name's Perrin—Amos Perrin. Well, Mr Clayton, you lay down that pack, and go right along up the cave, and see how the land lies. Dick, here, and I—I guess we'll stay right here, and see these natives don't come too close.'

'Right!' said Amyas briskly. 'Have you a light of any sort?'

The Professor fished an electric torch out of an inside pocket of his khaki-coloured tunic, and Amyas, with a word of thanks, dived into the black depths of the tunnel.

The other three stretched themselves flat on the platform. They were only too glad of the rest. Joe tightened the bandage on his leg; the other two laid their packs aside and re-loaded their weapons.

At the foot of the stone stairs the Indians surged in a mass. The big priest was with them again. His deep voice boomed out.

'Fixing to attack,' said Professor Perrin dryly.

'They'll be sorry if they do,' remarked Dick Selby. 'We can just everlastingly rake 'em if they start coming upstairs.'

'That's true,' allowed the Professor, 'but you've got to remember, Dick, that we haven't too many cartridges to waste, and we're a mighty long way from the nearest gun store.'

The Indians began spreading out. Clearly they had some plan at the back of their minds. They were forming in a long column. Each man had a spear and a bow and arrows. Some went back into the village. In a little while they returned, carrying bundles of some long, oval objects.

Joe got his glasses out, and focused them.

'Shields,' he remarked. 'They've got sense, those chaps.'

'Old Inca shields,' exclaimed the Professor, in sudden excitement. 'If they're made of hardened copper, as I suspect, they'll be as good as chilled steel. Say, Dick, this begins to look serious.'

Dick did not answer, but he, too, began to look rather grave.

Some time passed. The shields were served out. There were about forty of them, and the priest was evidently picking out the forty best men to wear them. He had a head, that priest, and it was quite clear that he meant to make a good job of it this time. The three who waited on the ledge began to feel anything but happy.

'Only hope Clayton'll find some way out,' said Dick.

Almost as he spoke there was a sound of steps, and Amyas reappeared.

'There is a passage,' he said, 'but it's blocked. Part of the roof has fallen.'

EVEN the stolid Joe looked dismayed.

'Badly blocked?' he asked.

'It's not a big fall, but it would take us some hours to dig through,' said Amyas.

Joe gave a low whistle. 'Look at that!' he said, pointing to the Indians. 'The beggars have got shields and the Professor says they're of hardened copper, and will turn a bullet.'

Before Amyas could reply the giant priest roared out an order, and the forty Indians came charging up the steps.

They climbed like cats. Their speed was amazing. They seemed to flow upwards in a torrent.

Dick Selby put his rifle to his shoulder.

'Dick, you just wait till they're real close,' said the Professor coolly. 'Then aim plumb at the first shield. We'll soon see what they're made of.'

Dick nodded. They had not long to wait. As soon as ever the first of the column was half-way up Selby fired.

His aim was good, and his bullet clanged on the first shield with a sound resembling that of its impact on an iron target.

The force of the blow knocked the shield-holder backwards, but the man behind him caught him; next moment he was coming up again as fast as ever.

'Guess I was right,' said the Professor. 'Real armour plate, that stuff. Try for his legs, Dick.'

Dick fired again. His aim was a little low, the bullet caught the edge of a step, ricochetted and spattered upwards. The man flung up his arms and fell.

But the rest did not wait. They came streaming up over his body. Matters began to look really ugly.

'If we only had some stones!' said Joe quickly. 'We could sweep them away with a big stone. Are there any in the cave, Amyas?'

'I didn't see any. But wait! What about these images? Are they solid rock or are they on pedestals?

He sprang up as he spoke, seized one of the stone gods and threw his weight on it. The thing moved slightly on its pedestal.

'It's all right. We can move it,' he cried. 'Selby, let Joe have your rifle. You give me a hand.'

Solid as Selby looked, he was quick enough to see what Amyas meant.

'Aim low,' he said to Joe as he handed him the rifle. Then he sprang to Amyas's help.

Between them, they toppled the stone god from its pedestal. It fell with a startling crash from its age-long perch, and broke in two upon the platform.

'That's the ticket,' said Selby. 'Roll her over, Clayton.'

Joe's rifle cracked. 'Be quick,' he said sharply. 'They're almost on top of us.'

The Professor let off both barrels of his shot-gun in the face of the column of Indians. Then he, too, sprang to help Amyas and Joe.

Though the statue was broken in two, each piece seemed to weigh a ton. The three toiled and strove to roll the nearest to the edge of the platform, but it was almost beyond their powers.

The rifle in Joe's hands fairly crackled, but the Indians, realising that something was up, were making a frantic rush. Though several were knocked over by the bullets fired at almost point-blank range, the rest leaped across the bodies of their fallen companions and made desperate efforts to reach the platform.

What was worse, those behind had pressed up behind the armoured column and were shooting arrows in showers.

'Hurry!' cried Joe. 'Hurry!'

Dick Selby made an effort which almost cracked his muscles. The upper half of the stone god turned ponderously over.

'Out o' the way, Cobb!' yelled Dick, and Joe rolled away just in time to escape the crashing weight of the mass of stone. Next instant it was over the edge!

For a moment it seemed to hang end-on upon the top step. Then, with a grinding crash, it toppled slowly over. The Indians saw it coming, and for the first time since the beginning of the fight screamed with terror.