RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"The Golden Key," Boys' Friend Library, #376, Apr 1917

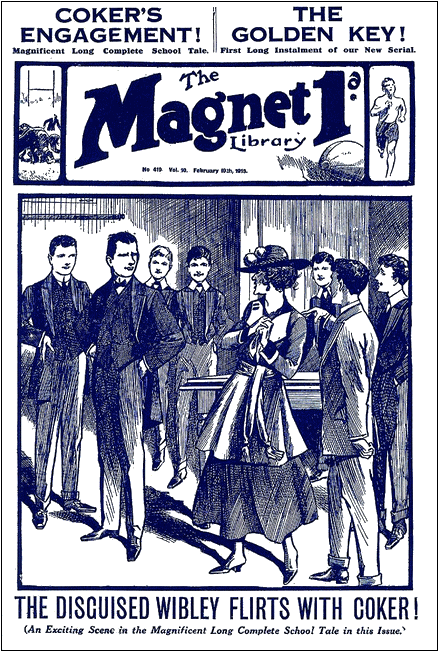

The Magnet Library, #419, Feb 19, 1916, with first part of "The Golden Key"

"NOTHING but catfish!" growled Dick Daunt, as he jerked the hook out of the mouth of another of the black, slimy, hideous-looking fish, and, knocking its head against the gunwale, flung it overboard.

"Say, I guess that must be about the forty-seventh you've caught, Dick," responded the other occupant of the boat—a lean young American, with a face as clean-cut as a Red Indian's, and a complexion so burnt by wind and sun that it resembled well- tanned saddle-leather. "Ain't it about time we got the hook up and shifted?"

"What's the use?" retorted Dick, whose rather thin face bore an expression of weariness and disgust such as Dudley Drew had rarely seen upon his partner's features. "It's the same everywhere else in this beastly creek. The only thing is to get out to sea and try for sheep's head or crevalle."

Drew looked doubtful.

"I reckon we'll have to pull a mighty long way," he answered. "There isn't a mite of wind."

"Oh. I'll pull!" said Dick. "We've simply got to have some fish for supper. 'Pon my Sam, I can't look a tin of bully-beef in the face any longer!"

Drew's reply was to begin pulling up the anchor.

As soon as he got it home the tide took hold of the clumsy boat and began to set her up on the creek. Dick got a grip of the oars, and, turning her, set to pulling the other way.

The water was like brown glass and although it was late October, the sun beat down mercilessly. If there was any breeze, the lofty walls of cypress and cabbage-palmetto which rose on either side cut it off. Perspiration streamed down Dick's face as he wielded the heavy oars.

Dudley shifted up on to the thwart behind him.

"You give me one of 'em," he said quietly; and though Dick objected, he insisted. Under the double drive the boat moved much more rapidly.

Presently the creek widened, and the trees grew thinner. A number of them, torn from their roots or broken short off, lay in the water.

"Say, but that hurricane has played thunder down here!" observed Dudley.

"I wouldn't have minded that if it had left our place alone," said Dick Daunt bitterly. "It makes me fairly sick to look at the wreck it's made of everything! I was round again this morning and counted. There are only thirty-seven cocoa-palms left out of the whole three hundred; and as for the orange-trees, it will be all of three years before we get a crop again."

"It's pretty bad," assented the other gravely.

"What I want to know," continued Dick, "is what we are going to do about it? You know jolly well, Dudley, that it will cost us a matter of three hundred dollars to replant and put things to rights. Then we've got to live for the next three years until we get a crop. And we haven't more than sixty dollars between us. What's to be done?"

"I reckon that's just what I've been saying to myself ever since the day it happened, Dick. We're up against it. That's a sure thing."

"But see here," he continued, "this isn't any time to be chewing the rag. After supper we'll have it out, and if you've a mind to let go and set to some fresh job—why, I'm not going to do any kicking."

Dick was silent. He realised that Dudley was right. Also he felt somewhat ashamed. It was true that he had put money into the neat little place which lay near the shore of Lemon Bay, but it was Dudley who had made it. Four years' hard work under the tropic sun the young American had put into the place. He, Dick, had only been on it a year. He knew how Dudley loved it, and fully realised what a wrench it would be for him to give it up. What business had he got to grouse when Dudley took it all so quietly?

By this time the boat had crossed the bar, and was out on the placid surface of Lemon Bay There was hardly a ripple on the mirror-like blue. It was difficult to believe that only four days earlier this same pond-like sea had been thundering on the white beach in breakers as high as houses, while the foam-flakes had been driven hundreds of yards inland through the forest.

A sudden tremendous splash made him start, and he was just in time to see something resembling a six-foot bar of silver rise out of the sea, hang poised an instant in mid-air, and disappear again with a sullen plunge.

"Tarpon!" he shouted. "Great luck, Dudley! Mullet must be in the bay."

"That's so!" replied Dudley quietly. "I guess we'll anchor right here and try our luck."

He flung over the anchor, and the boat swung to it with her bow pointing seawards.

Her crew hastily baited the hand-lines and flung them out; and inside two minutes were pulling in bright-scaled mullet as fast as they could handle the lines. The fish averaged about a pound in weight, and were in splendid condition.

The shining pile grew rapidly.

"We'll have plenty to take over to Port Lemon," said Dick. "Old Ladd, the storekeeper, ought to give us a good trade in exchange for these."

At this moment there came a tremendous jerk at Dudley's line. He pulled hard; then, all of a sudden, the line went slack, and when he hauled it in hook, snood, and all were gone.

"Blame the luck!" he exclaimed, in a tone of deep annoyance. "It's a shark! I guess that's finished our sport this journey."

"No; by Jove, I'm not going to stick that!" returned Dick emphatically. "The shark-line's aboard, and if we bait with one of the bigger fish the chances are we'll have the beggar!"

"And be towed all around the bay!" returned Dudley drily.

"Never mind! The mullet will come again. Besides, I want a shark. We're in need of some oil for our boots and harness."

As he spoke he was baiting a thing the size of a meat-hook. There was three foot of steel chain attached to it, and to that again a long coil of stout line.

In a minute or two all was ready, and he threw it out. Dudley had got in his mullet-line. It is no use fishing when sharks are about.

Five minutes or more passed slowly; then the shark-line began to move slowly and jerkily over the gunwale. Dick watched the line with eager eyes. Dudley was quietly raising the anchor.

Foot by foot it stole away, then suddenly began to run out rapidly. Dick, who had risen to his feet, got tight hold of the line with both hands and gave a fierce jerk.

"Got him!" he roared triumphantly, and, springing forward, made the line fast with a couple of turns around a cleat in the bow.

Instantly the line was taut as a fiddle-string, and the boat, pulled by the unseen monster below, began to forge rapidly ahead.

"A big one!" said Dudley briefly, as he slipped into the stern sheets and took the tiller.

The pace of the boat increased. She was heading straight out to sea. A great black triangular fin showed up on the surface and went cutting through the water at a furious rate.

For nearly half an hour this went on, and still the great brute showed no signs of tiring. Dudley glanced back towards the shore, now quite three miles away.

"Looks like we were bound for Cuba," he observed, in his dry way.

Almost as he spoke the shark turned southwards, parallel with the coast.

"Don't worry!" Dick replied. "He's going to give us a free ride to Port Lemon."

Another ten minutes and the pace slackened perceptible. Dick began to haul on the line; but this started his shark-ship up afresh, and he spurted hard for nearly a mile.

Then he slacked up again.

"Mighty nigh time to lance him," said Dudley.

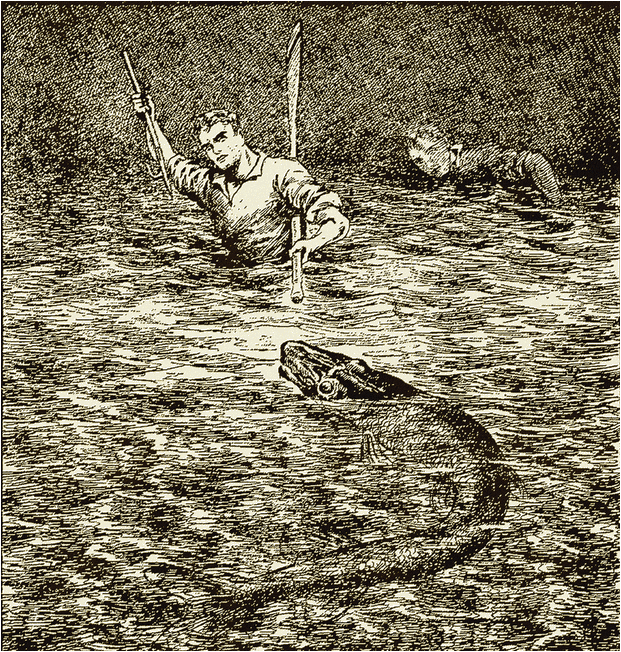

Dick nodded, and picked up from the bottom of the boat a stout six-foot length of bamboo armed at the end with a sharp steel point.

The shark had almost stopped, and was beating the surface with his tail. Dudley took the oars, and pulled quietly up alongside.

Dick was ready. The lance-head flashed in the sunlight as it clove the air, and, aimed to perfection, was buried deep in the steel-gray body.

A sheet of spray flew over them, the boat rocked in the waves caused by the monster's struggles, and the blue water turned pink with blood.

"That was a mighty good lance, Dick." said Dudley. "I don't reckon we'll have a lot more trouble."

But a shark takes a lot of killing. The wound seemed to galvanise the huge brute into fresh energy, and off he went again at the rate of knots, and now heading straight back towards the coast.

But the spurt did not last very long, and presently Dick was able to get his lance to work again. This time he finished the job, and the long torpedo-shaped body floated motionless on the surface.

"Told you he'd take us in again." said Dick, with a laugh, and pointing to the shore, not half a mile away. "We'll beach him, chop out his liver, then slip along to Port Lemon. We can sell or swap our mullet, and get back in time to catch some more for supper."

"Seems a pretty slick programme!" drawled Dudley. "But I'm right with you."

The tide helped them in; they beached the boat, and, hauling the shark ashore, set to work with the big flinching-knife which they always carried.

Well practised as he was in this kind of work, it took Dick only a very short time to rip the great carcass open, and the huge liver, reeking with oil, was taken out and lifted into the boat.

"Wonder if he's got anything else inside him?" said Dick.

"I reckon not. He's hardly large enough to be a man-eater," answered Dudley.

"I'll just have a look. It won't take a minute," Dick said, as he stooped and inserted the knife again.

The skin, harsh as sandpaper, ripped with a grating sound, and then the knife rang on something hard and resonant.

"Hallo!" exclaimed Dick. "Here's treasure trove!"

And thrusting in his hand, he drew out a bottle.

Dudley laughed.

"Say, Dick, he must have been kind of hungry to go lunching on empty bottles."

"It isn't empty," declared Dick, as he held up his find. "It's corked."

"Corked, is it? Let's hope it's ginger-pop inside! I could do with a little liquid refreshment. Here's a corkscrew."

But Dick had already solved the problem of opening the bottle by knocking off its head with the back of the flinching- knife.

"Empty," he said. Then, with a start; "No, by Jove! There's a paper inside!"

"The mischief, you say? Have it out, Dick! Here's the start of a dime novel. Strange manuscript found in the stomach of a tiger- shark!"

"It's manuscript, all right!" Dick's voice betrayed more than a little excitement. "It's a letter."

"It's manuscript, all right!" Dick's voice betrayed

more than a little excitement. "It's a letter."

"A letter! Read it right out, Dick!"

The sheet which Dick had taken from the bottle was coarse, whity-brown paper, the kind used in country stores for wrapping parcels, it was rolled in a cylinder, and Dick smoothed it out carefully.

"Wait a jiffy! How does it go? Ah, this is the right way up! My aunt, what a fist! Looks as if a spider had fallen in the ink- pot, and tried to dry himself on the paper afterwards. All right; don't got impatient! I've got it:

"To anyone who picks up this bottle,—I, Matthew Snell, having lost my boat in the great storm of October 16th, am marooned, and in danger of starving on an unnamed island in the Keys. I will richly reward any person who will bring me food and take me off. The island lies, so far as I have judged the distance, sixty-three miles south-east by south of Cape Saturn. It can be known, when sighted, by the two small peaks on the north-west, the northerly hill being bare of trees.

"Signed this seventeenth day of October.

"Matthew Snell."

For several seconds after Dick had finished this remarkable

screed, the two young fellows stood staring at one another in

complete silence.

Dudley was the first to speak.

"Some tourist chap wrote that for a joke, I reckon, and tossed it overboard from a steamer."

But Dick seemed hardly to hear. His brows were creased, his lips tightly closed. He appeared to be trying to remember something.

"Snell," he muttered—"Matthew Snell." And then suddenly: "By Jove, I've got it! That's the very chap that Ladd told me of somewhere about three months ago."

"Ladd! What's he know of him?"

"He and I were having a yarn that night we got caught in a breeze, and had to stay the night at Port Lemon. Yes; I remember it all now. He told me that an old man named Snell had been in only the day before, and bought a lot of stuff. He'd been in half a dozen times or so during the past two years. Came in a rubbly old sailing-boat, and always got about the same lot of stuff. And the rum thing about it was, he always paid in gold-dust."

"Gold-dust!" exclaimed Dudley, roused for once! "Gold-dust! Say, he's crazy! There isn't no gold-dust in Florida, or any of the Keys, either."

"THAT'S what he said, anyhow," returned Dick obstinately "And if you don't believe me, you'd better ask him!"

"We'll do that, right now!" answered Dudley emphatically. "We're only two miles from Port Lemon, and I guess we'll have the truth out of old man Ladd before we're an hour older."

A little breeze had sprung up, just enough to fill the sail, and with this on the beam, they made good time to Port Lemon, where they tied up at the long timber-built pier, and went ashore, each carrying a string of fish.

The place was only a village, just a few frame houses dumped down in a clearing of a dozen acres behind the broad, white beach. The boys were pretty well known in the place, and several men shouted greetings from the verandahs, and more than one asked them to stop.

But, eager to see Ladd; they excused themselves, and hurried on to Ladd's store. This was a great barn of a place, with long counters running up each side, and behind them shelves fixed against the match-boarded walls, and loaded with every sort of goods, from tinned tongues to teapots, and from women's hats to men's boots.

"Hallo, boys!" came a great booming voice, and Ladd himself stepped forward to greet them.

Ladd was little more than five feet tall, and looked as broad as he was high. He had a huge red face, a long red beard, and a thick crop of the most flaming red hair that ever was seen. He was so fat that he waddled rather than walked, and, in spite of his fat, was always fit and always cheerful.

"Hallo, boys! I been reckoning I'd see you pretty soon. Got some fish for me? Them's fine mullet! where did ye get 'em?"

"Opposite our place," Dick answered. "Got a shark, too!"

"Did ye now? Waal, you lay them fish down over in the ice-box here, and ye can have two dollars' worth of trade for 'em. Guess that storm served you pretty bad, didn't it? You'll be wanting some new stuff up along your place. What kin I do for you?"

"Give us five minutes in your office," cut in Dudley. "Dick, here, has something to ask you."

Ladd looked a little surprised.

"Secrets—eh? Waal, there ain't a lot o' folk here this minute"—looking round the empty store—"and it's cooler here than in the office. What's the matter with having it out here?"

"All right. It won't take long," said Dick. "Do you remember telling me about an old chap called Matthew Snell?"

"Matt Snell! You bet I do! Thet old scarecrow as comes in from the Keys in a boat that looks like it might hev been made out o' the wreck o' the Ark!"

"And paid for his grub in gold-dust?" questioned Dick.

"That's so. Though where he got it beats me. I guess he's the first man as has found dust anywheres nearer than Cuba. They do say there's gold over there, but as for them Keys, I never heard tell of any gold except Spanish treasure and such like."

"But it was dusk?" put in Dick.

"You can bet your life on that, son! I been West, and I know dust when I handles it. And that was a mighty good sample. About twenty-two carat, as I sold it."

Dick glanced at Dudley. He was staring at Ladd with a look of the keenest interest.

"But say," went on Ladd. "What's the trouble? What makes you two fellers so interested all of a sudden?"

Again Dick looked at Dudley, and Dudley nodded.

"Don't you tell if you don't want to," said Ladd.

"But I do want to," replied Dick. "Only I'll ask you to keep dark about it for the present."

"Oh, I'll do that! I'll be mum as an oyster," asserted Ladd, with a fat chuckle.

"Then read this," said Dick, handing him the letter.

Ladd did so, and for once his big face assumed a solemn expression.

"Gee, but this sounds like business!" he remarked. "Where did ye get it?"

"Out of the shark," Dick told him.

"And what are ye going to do about it?"

"Take a trip across," answered Dick briefly.

Ladd nodded.

"I guess it's worth it. Reckon your boat's big enough?"

"Yes; if the weather holds up."

"It's likely to be fine quite a spell ofter that storm."

"But I reckon we shall want some stores, Mr. Ladd," put in Dudley. "That storm's pretty near broke us."

"I'll go you," said Ladd. "If you gets the reward the old feller shouts about—why, you can square up. If you don't—why, that'll be all right. I guess I've had right smart profit out of Matt Snell the times he's been dealing along with me."

"Thanks! That's awfully good of you!" answered Dick warmly. "We'll get off."

Dudley nudged him, and he pulled up short, and looked round in surprise.

Then he saw the reason why Dudley had checked him.

It was not a pretty reason. The man who had just entered the store was the human image of a turkey-buzzard. He had the same small head at the end of a long, scaly-looking neck, and he carried it forward just as does that unclean scavenger of the tropics. His thin, hooked nose was extraordinarily like a buzzard's bill. His skull was bare as a billiard-ball, and a long fringe of dirty-looking hair hung down over his greasy coat- collar. To make the resemblance more complete, he had just the same shuffling walk as the bird which he so faithfully copied.

He was Ezra Cray, Yankee by birth, but with only one Yankee trait in his character. That was meanness. As Ladd had often said: "That feller Cray is so cussed mean, I wonder he don't steal the clothes off of his own back."

"How d'ye, Ladd?" he remarked in a harsh, croaking voice.

"And what do you want?" demanded Ladd, openly hostile.

"I wants some stores when you got time to attend to me," snarled Cray, with an attempt at sarcasm.

"Hev you got the money to pay for 'em?" inquired Ladd.

For answer, Cray took a wad of greasy five-dollar bills out of his pocket, and slammed them down on the counter.

"I got the money if you got the goods!" he snapped.

Dick cut in:

"Then we'll be getting home, Mr. Ladd. Thanks for what you've told us. We'll be round first thing in the morning for the stuff."

"Right, boys!" said Ladd cheerfully. "I guess we can fix it up all right. Good-night to you!"

"That chap Cray gives me creeps!" remarked Dick, as they clambered into their boat again.

"In fact, he's a reptile," allowed Dudley; "the worst around these parts."

"They say he's in with that moonlighting crowd up the creek," said Dick. "Those chaps that run the distillery up in life swamps."

"That's what Sheriff Anderson says, anyway," replied Dudley; "and I reckon he knows."

"Say, Dick," he continued, "you fixed up mighty quick to go to this island."

Dick stared.

"Didn't you want to go?"

"You bet. But it means leaving our place to look after itself for maybe a week. You can't count on getting help round this time of year."

"What is there left to look after?" asked Dick, frowning.

"Mighty little," replied Dudley, with a sigh. "All the same, this business is pretty much of a gamble."

"Just so. And if it turns up trumps, and we find the old boy, that reward he offers may just set us on our legs again. A handful or two of that dust will go a long way to repairing the damage. And we might be able to buy a bigger boat, and work the fishing properly this winter."

Dudley nodded.

"That's so. All right, Dick. We'll get to it, then."

Get to it they did. That night they overhauled the boat, rove some new running tackle, mended a hole in the ancient mainsail, and got their gear together. Before daylight next morning they were afloat again, and at six were back at Port Lemon.

Rarely as it was, Ladd was waiting for them. He put a thick finger to his lips, and beckoned them inside the score.

"Say, boys," he said, in a low voice, "I'm afeared you're in for a heap o' trouble. That there fellow Cray is on the job."

"CRAY on the job?" said Dick sharply. "You don't mean to say you've told him?"

"Me tell! What d'ye take me for?" retorted Ladd, his red beard fairly bristling.

"Sorry! I ought not to have said that. But you say Cray is on the game. How can that be? I vow he didn't overhear us yesterday."

"I don't reckon he did. And how in thunder he got wise beats me like it does you. All I knows is that the skunk was in here arter you left, buying stuff for a cruise, and paying for it in good money."

"He may be on a trip after turtles," suggested Dick.

"You wait, young feller. Bernard J. Ladd may be fat, but he ain't a fool. I sorter suspicioned something, and arter he left I slipped out around the back and follered him down to the beach. He was a-loading the stuff on that big centre-board o' his, and along with him was that all-fired rascal Seth Weekes."

"The moonlighter?" exclaimed Dick.

"That's right; the boss o' that gang. I got down behind another boat, and 'twas dark by then, so they didn't see me, and I got a chance to listen. Wasn't much as I could hear, for they talked mighty quiet, but I'm a Dutchman if I didn't hear Snell's name spoke, and more'n once, too."

"The mischief!" mattered Dick. "What's to be done?"

"Done!" repeated Ladd. "Why, get to it, boys! They ain't started yet. I been watching, and there ain't a soul been down to the boat this morning. I reckon they're waiting for some more o' their dod-gasted crowd from up the swamps there. Now, I got all the stuff ready for you, and all you got to do is tote it down. Then you turns round as if you was a-going right home again, and so soon as you're round the point you makes away for this here island."

The two boys exchanged glances.

"He's right." said Dick.

"That's so," replied Dudley quietly. "And even if they do get off soon, we ought to outsail them. In this light breeze we can do a sight better than they can."

"That's right," declared Ladd. "Now here's your stuff, all done up in sacks. Go straight on down to the beach leisurely like. Don't hurry. Act just like you was going home. And say," he went on quickly, "you got a gun along?"

"Yes. I've got my forty-four repeater," said Dudley, "and Dick here has his scatter-gun."

"That's all hunky. Likely you'll need 'em before you're through. You mind this. The law don't run on them Keys—at least, not anything to signify—and it's the chap as gets the drop first as comes out top dog."

He stooped and lifted a sack on to the counter, and then a second. They were heavy, too—each a good load for a man.

"Guess you'll find all you need in there, boys. Good luck to you, and pockets full of dust!"

He gave them each a grip that was like a bear's, and they marched off down to their boat.

The morning breeze was right off the land, and as soon as they were half a mile out they began to feel it. The cat-boat lay over, and a slim feather of foam began to curl up on either side, under her prow.

Dudley looked back.

"We've stolen a march on them, Dick. There's not a soul around on the beach yet."

Hour after hour the breeze held. By nine the coast of Florida was hull down, and they were driving steadily south-eastwards over the wrinkled swells of the Gulf of Mexico. Neither knew much about navigation, but they had a compass, and, in any case, were able to set a course by the sun.

So the long afternoon wore on, and still there was no sign of land.

Dick looked at the sun.

"It will be down in an hour," he said, rather gloomily, "and there's not a ghost of a sign of the island."

Dudley got up, and, standing in the bows, clinging to the forestay, stared round the horizon. At last he turned to the other.

"I believe I can see something. I don't know what it is, but it looks mighty like land. Over there!"

He pointed as he spoke, and Dick slightly altered his course. Within another quarter of an hour Dudley was able to say definitely that it was land of some sort.

Their spirits rose, and they held on, close-hauled as possible.

But now—as almost always happens at sunset in tropical seas—the wind began to fall, and soon the cat-boat was bumping heavily in the smooth swell, her sails slatting aimlessly against the mast.

"It's all right," said Dudley, still cheerful. "We'll get the night breeze after a bit. Then we'll make it. And now I reckon it's 'most supper-time."

Tinned tongue, more biscuits, and a can of fruit in syrup did them no end of good, and as they ate they watched the sun, a huge globe of crimson, dip slowly behind the placid sea.

But it was another hour before the night breeze began to blow, and now it was nearly dark.

Then came a real misfortune. Slowly but steadily a bank of cloud began to rise, and behind its great, grey veil the stars vanished, leaving them lost upon a pitch-dark sea. The breeze began to stiffen again, and Dick, at least, became very anxious indeed.

"We'll have to get a reef in, Dudley," said Dick at last, after a squall which had nearly buried the low-sided craft.

At that very moment Dudley gave a shout:

"Watch out, Dick! Breakers just ahead!"

Dick flung her over on the other tack with lightning speed.

"Gee whiz! But that was close!" exclaimed Dudley, pointing to a tumble of white foam roaring on rocks hardly a biscuit's throw to starboard. "I guess this is the island, all right."

The wind had steadied a little, but the thunder of the surf was terrifying.

"I believe I'll drop the peak," said Dick. "But goodness only knows how we'll ever make a landing."

"Breakers to port!" was Dudley's alarming reply. "Put her over, quick, Dick!"

Dick obeyed like a flash. Only just in time, for now leaping crests were visible through the gloom about fifty yards on the port-side.

"We're right in the middle of it!" growled Dick.

Yet, in spite of the imminent peril on both sides, his hand was steady as steel on the tiller. Given somewhat to grousing at small misfortunes or discomforts, Dick Daunt could always be relied on in a really tight place.

Dudley was standing up, staring out ahead.

"We're sure in the middle of all kinds of reefs, Dick. Keep her as she goes. Seems there's some sort of a channel ahead."

A moment later he had to shout to Dick to luff again. And now all around the waves were breaking white. The boat had run into a very tangle of reefs. It seemed out of the question to ever extricate her.

Ten minutes passed. They seemed like ten hours. Then came a triumphant shout from Dudley.

"We're through. Dick! We're through, old son!"

Dick heaved a deep sigh.

"And where's your blessed island?" he grunted.

The words were hardly out of his mouth before the cat-boat took ground with a shock that sent Dudley sprawling.

He picked himself up.

"You've found it all right," he said drily.

Dick had the sail down in half no time.

"It's only sand!" he gasped.

"Yes; and I guess that's the beach right ahead," answered Dudley. "We haven't a lot to kick about after all."

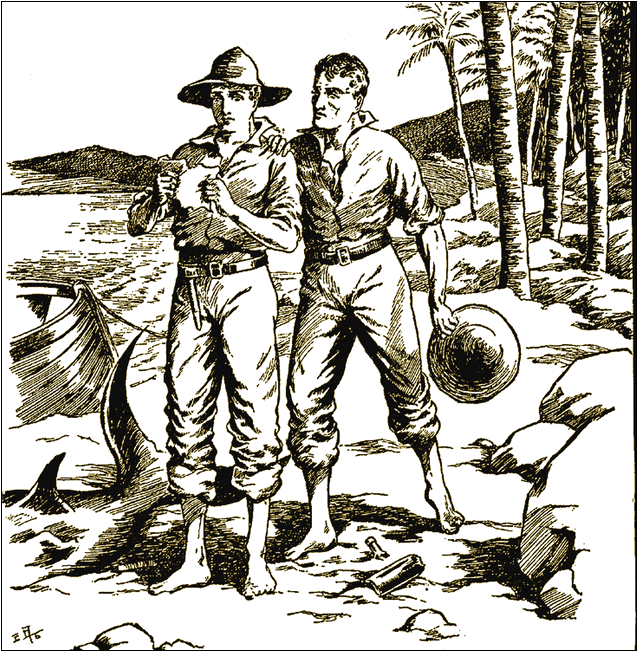

As he spoke he jumped out into the water. Dick followed his example, and together they pulled the boat up. The tide was falling, and they soon had her high and dry. They anchored her firmly, carrying the hook a good way up the beach, then dropped down under her lee. They were both pretty well played out.

"We don't even know whether this is the right island!" grunted Dick, as he wrung the water out of his trousers, which he had pulled off for that purpose.

"I'm willing to gamble it's the right one," laughed Dudley. "But we can't be sure till morning. Meantime, I reckon we'd better roll up in our blankets and take a snooze."

The advice was good, and within a very few minutes they both were stretched on the sand sound asleep. They were dog-tired, and neither moved until the sun, blazing full in their faces, roused them to the fact that the day was nearly an hour old.

Dudley was first on his feet.

"There are the two hills, Dick!" he exclaimed, with a touch of excitement such as he seldom showed. "We're all right!"

"That's a good-job," Dick answered, sitting up and rubbing his eyes. "Don't see the old man, I suppose?"

"Not a sign of him. But I guess he wouldn't be looking for us here. Great Scott! Look at the reefs we came through!"

"Bother the reefs!" said Dick. "I saw enough of 'em last night. What I want to see now is my breakfast!"

"It won't be long," smiled Dudley, who was already collecting driftwood for a fire.

Hot coffee and fried flying fish tasted delicious, and having finished their meal, they unloaded their stores, and cached them in the sandbanks behind the beach, covering them over carefully lest Cray's party might arrive.

"What about the boat?" asked Dick.

"We can't cache her; that's one thing sure," said Dudley. "I guess she'll be all right where she is. Cray won't try in through those reefs, even if he does come along. Anyhow, we ought to see his crowd from the hill if they're anywhere on the horizon."

Dick nodded.

"Right you are! Now for the old man. We'd best go up the hill first, hadn't we?"

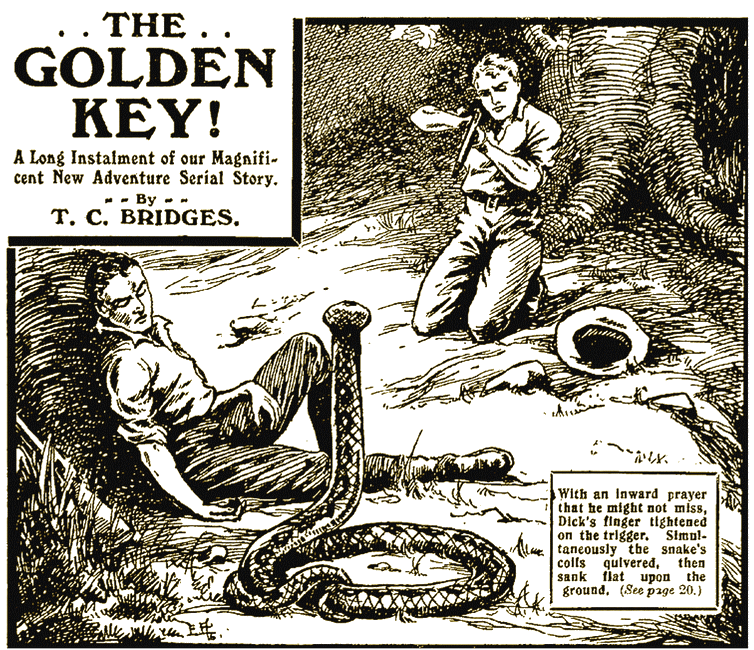

Dudley agreed, and they started. Behind the beach was a belt of thick scrub composed of saw-palmetto and bamboo vine, wicked stuff to force a way through. Also, it was haunted by rattlesnakes, from one of which Dudley had a very narrow escape.

Inland the ground rose and the scrub turned to forest.

"This isn't any coral island," said Dick, as he glanced down at the rich, loamy soil.

"Not it! You don't get hills on the ordinary Keys. I reckon this is the top of some old volcano that got licked up out of the Gulf a few thousand years ago. And say, Dick, there's always metals in this sort of rock."

"Then the gold-dust might have come from here after all," said Dick.

"Not a mite of a reason why it shouldn't. Hallo! A creek! Maybe this is the one he washes the dust out of."

"Let's go up it, then."

They did so, and presently found distinct signs of man's handiwork. A dam had been built across the rivulet, and its course turned. There was a shovel sticking in the ground.

"And here's a path!" exclaimed Dick suddenly.

He turned quickly up it, and Dudley followed. They were both getting really interested. The path wound through the thick trees for a couple of hundred yards, and opened quite suddenly into a small clearing, roughly fenced, where corn and sweet potatoes were growing. In the middle was a small log hut thatched with reeds. The chinks were cemented with clay.

"Got it at lost!" exclaimed Dick, running forward.

The door was open. He went straight in, but the room was empty.

"Mr. Snell!" he cried. "Mr. Snell!"

There was no reply.

"He must be out around somewhere," said Dudley. "Guess we'd better go and look."

"I suppose we had," replied Dick slowly, "Still, it's a bit odd that he's not here or at his diggings."

They started out, and, by Dudley's advice, went first to the top of the nearest hill. From here they got a view of the whole island. It was quite small—only about two miles long by a mile to a mile and a half wide.

Dick scanned the horizon. The sea was empty.

"No sign of Cray's crowd, anyhow," he said with some satisfaction.

"Nor of Snell, either." rejoined Dudley. "I wonder where the old fellow's got to?"

"We'll have a look round, anyway," said Dick, turning.

They searched all day, they covered the whole island, they fired shots, they lit a big fire. At dusk, utterly tired out, they crawled back to the shack.

"This beats all!" said Dudley. "The old boy's vanished into thin air."

IT seemed that Dudley must be right. Old Snell was gone, and as Dudley and Dick together walked slowly back to the little house by the creek they discussed his disappearance in hushed voices.

"He was ill when he wrote that letter and set it afloat," said Dick. "He may have died."

"That's so." replied Dudley. "But if that's the case, where's his body? You'd reckon to find it in the hut, wouldn't you?"

Dick nodded frowningly.

"Yes, I suppose you would. But it's not a sure thing, by any means. He'd have been watching the sea, very likely, and would have been too bad to get back. Or he might have fallen over a cliff or into one of these big ravines which run inland from the sea."

"Yes, I guess that's possible," Dudley answered. "Or he might have been bitten by a snake. Say, Dick, there are more snakes on this island than I've got any use for."

"There'll he worse than snakes when Cray and his crowd land," said Dick grimly. "Which reminds me—we'll have to keep a watch to-night."

Dudley groaned.

"I could sleep a week," he said ruefully. "But you're right, Dick. It's a sure thing we'll have to watch."

"There's always the chance that the beggars came to grief in that blow," Dick suggested hopefully. "Or they may have missed the island altogether, and be messing about out in the Gulf miles away."

"I'd give a bit to knew they had," smiled Dudley. "But it's a case of hope for the best, and expect the worst."

"Well," he added thoughtfully, "whatever comes along, that gold's worth a bit of risk. Gee! but we wouldn't need much more than a clear week of digging to put us on the right side of everything."

"I'm with you there," said Dick heartily. "Whatever happens, we're going to stick to the game until we've got our pockets full."

"Shake on that!" replied Dudley. "I'm with you all the way."

Dusk was falling as they reached the little house. At their first visit, earlier in the day, they had not wasted much time exploring. Now they had a good look round.

"Snell must have been a dodgy old chap," said Dick. "He's got everything here top-hole."

"And I don't reckon he was very near starving, either," replied Dudley, rummaging in a cupboard. "Here's grub for a month!"

He began digging out tinned stuff of all sorts, with various packets of rice, sugar, coffee, and hominy.

"And, say!" he added. "He hasn't been gone a great while. Here's a tin of roast beef opened, and fresh yet."

"Well, I'm blessed!" exclaimed Dick, sniffing the meat. "In this weather that would have gone as high as Haman inside forty- eight hours. You're just about right, Dudley. Snell's been here within the past two days."

"Snell or somebody, with a tin-opener," added Dudley.

"I wish we could find the old chap," said Dick seriously. "It's poor luck his going under just before we turn up to rescue him."

"And, incidentally, to take the little bag of dust," put in Dudley. "Well, see here, Dick, there's lots of stuff here, so there'll be no need to go back to our cache for stores. Let's make a good supper, and toss for who takes first watch."

This seemed good to Dick; and Dudley, who was a top-hole cook, set to work with his pots and pans, while Dick got a roaring fire in the stove. In little more than half an hour all was ready.

There was a great pile of waffles, or flapjacks, hot from the frying-pan, a dish of dry hash made of corned-beef, onions, and potatoes all fried together, and a pot of excellent coffee.

They were both starving hungry after their long tramp, and made short work of the good things. Then they drew straws, and it fell to Dick to take first watch.

Dudley lay down at once, and had hardly stretched himself out before he was asleep. Dick watched him.

"Poor old chap! I'm glad he got first nap," he muttered. "He's absolutely dead beat."

Dick was none too fresh himself, for the previous day and night had taken it out of him pretty severely. He hardly dared sit down for fear of dropping off, so went out and strolled about the place.

It was a wonderful night, clear and calm, but rather dark, as there was no moon. Myriads of fireflies flitted over the brook, making sparks of bluish fire in the gloom. The only sounds were the murmur of the brook and, in the distance, the slow wash of the surf on the cliffs.

Dick kept his rifle handy. He did not know at what moment Ezra Cray and his pack of rascally moonshiners and beachcombers might turn up.

Up and down he tramped, now and then resting for a few minutes on a fallen log, but always listening keenly for any suspicious sound. None came; and at last, by the light of a firefly which he caught and imprisoned, he saw that the hands of his watch were almost together at the top of the dial.

He turned towards the house, and was close to the door, when he pulled up short, listening keenly.

A low, moaning roar had suddenly broken the stillness—a most strange and eerie sound, coming as it did through the calm darkness. It was not quite like anything that he had ever heard before, and, for the life of him, he could not place it.

It rose from a moan to a sort of bellow, then slowly died away.

He went quickly in, roused Dudley, and told him. The two came out together. Three or four minutes passed in absolute silence, then again the extraordinary noise broke forth.

"What do you make of it, Dudley?" Dick asked anxiously.

"I'll be blamed if I know! It's the right-down queerest thing I ever did hear. Only time I ever remember hearing anything like it was when I was over in the Yellowstone Park with my dad, when I was a kid. A geyser broke loose, and shot a great cloud of hot water and steam up into the air."

"A geyser—eh? But we've seen nothing like that on this bit of an island. And if there had been one, we'd surely have heard it before now."

"That's so. It beats me, Jim. Still, it don't seem to be anywhere very near, and it isn't the sort of row that Cray and Co. could make, even if they wanted to."

While they talked the thing came a third time, sounding just as before.

"I believe it's out at sea," said Jim. "It's not unlike a foghorn."

"Foghorn! Great Caesar! It would take six foghorns to make a noise like that! Besides, the night's as clear as a bell. I guess you'd best go and take your sleep, Dick. Noise ain't going to hurt us any, and if anything shows up—why, I'll have you out in about half a shake!"

The advice seemed good to him, and so utterly weary was he that, in spite of the weird trumpeting which still continued at intervals of three or four minutes, his eyes closed, and he was very soon as sound asleep as Dudley had been a few minutes earlier.

When he awoke, the pink flush of dawn was visible through the open shutter, and he jumped up in a hurry.

Dudley was collecting kindling-wood just outside.

"You rotter!" exclaimed Dick. "Why didn't you wake me?"

"That's all right," smiled Dudley. "You haven't had any more than your share."

"What about that noise?" demanded Dick.

"It stopped along about two. Haven't heard it since."

"Wish I knew what it was," said Dick, rather uneasily. "Now you stretch out, Dudley. May as well have another short nap while I get breakfast."

Dudley obeyed, but was quite ready for his meal when Dick roused him. They freshened themselves with a dip in the pool behind the dam, then while they ate their food discussed the business for the day.

"Seems to me we'd better rake in all the gold we can," said Dick, "and be sure of something for our trouble, before Cray and his outfit turn up."

Dudley shook his head.

"No, sir. First thing we've got to do is to fix up some place we can hide in. Pretty sort of idiots we'd look if Cray's crowd dropped on us when we were down there in the middle of the brook! There wouldn't be a dog's chance for a getaway."

Rather reluctantly Dick had to admit that his partner was right. They started out, and first of all climbed the hill and had a look round. But the sea stretched empty to the blue horizon.

"Cray's missed it!" Dick declared cheerfully.

"Don't you get too gay," returned Dudley. "He'll make this place sooner or later if he's still above water. There isn't anything would keep that fellow away where gold's in the question. He'll smell it out like a terrier does a rat.

"I guess we'll go right ahead, and fix ourselves up against a surprise," he continued.

They soon reached the rocky cove where they had beached the boat. Dudley was of the opinion that she was not well enough hidden, and they searched for a safe place.

They found it, too. A little to the west was a queer little inlet, which ran deep into the cliff, with a mouth so narrow and shallow it hardly looked as if there was room to push any sort of a boat in. They waded up the channel, and found inside a regular rock-bound harbour. It was hardly fifty yards across, but the water was deep and clear, and still as a pond.

"Couldn't have been better if it was made for us!" declared Dick, glancing up at the tall and almost perpendicular cliffs, which rose to a height of a hundred feet or more on every side, and the shaggy, hanging creepers at the top. "But we'll have to wait till the tides risen a bit before we can put her in."

"Meantime, I guess we'll hunt for something as good for our own selves," answered Dudley. "Some sort of a cave is what I'm reckoning on."

On both sides of the entrance to the hidden pool the cliffs were broken in the strangest fashion. Great slabs had fallen away, and lay in tumbled masses upon the beach. Dark crannies yawned in every direction. This was the side of the island exposed to the north-westerly gales, which are the worst in this region, and the waves had certainly done terrible work upon the rock-bound shores of Golden Key.

Starting from different points, the two began to climb upwards, and presently met on a ledge some fifty feet up.

"I've struck a place," said Dick.

"Guess I've got one, too," replied Dudley. "Let's see yours first, then we can have a look at mine."

Dick's was a shallow cave with a wide entrance. Dudley's was smaller, and less convenient; but the entrance was narrower and easier to hold against attack. Dick willingly agreed that the latter was the better, and they set to work to carry their stores and ammunition up, and hide them. By the time they had finished this job, there was water enough to get the boat into the cove.

"Good work!" said Dudley, as he swept the perspiration from his forehead with the back of his hand. "Now, I feel kind of happy. Whatever comes along, we've got a right nice place to hide in. It'll take Cray's crooks quite a while to nose out that hidden bay."

"Good name for it," put in Dick, with a laugh. "Hidden Bay, we'll call our harbour, and Crooked Cliff would be about right for this old tangle of rocks."

Dudley nodded, and glanced up at the sun.

"Dinner-time, Dick. And what price washing out a bit of pay- dirt this afternoon?"

DICK stood in the blazing sun, in the middle of the dry creek bed, and stared at something which he held in the palm of his open left hand.

"Talk of little Jack Horner!" he remarked, in a voice which had a note almost of awe.

"Never heard of the gentleman," responded Dudley flippantly, as he came across. "What have you got there?"

Then, as his eyes fell on the object in Jack's hand, he gave a sharp start.

"Holy smoke! Where did you get that?"

"Just picked it out of the last shovelful of gravel, like Jack Horner did out of his Christmas-pie, you ignorant American!" retorted Dick, with a grin.

It was a dull yellow object, the size and nearly the shape of a large hazel-nut, which Dudley took from the other and examined carefully.

"Ten dollars' worth of gold in that," he said, in a voice that was not quite steady. "Either you're in big luck, Dick, or this gravel is as rich as the original Sutter's Creek claim in California."

He stooped swiftly as he spoke, and lifted a second nugget nearly at big as the first, which his quick eyes had detected lying among the disturbed gravel.

"Here's another! Dick, give me a month right here, and we won't either of us need to grow any more oranges or coconuts than we want to eat for the rest of our little lives."

Dick's eyes shone. Small wonder. In all the world there is no experience more exciting than digging for gold and really finding it.

"Then, by Jove," he said, "we'll make the most of the time we have, Dudley."

And, grasping his shovel, he set to work with furious energy.

Dudley knew something about washing gold, Dick nothing at all. But under Dudley's tuition, the young Britisher developed a really marvellous aptitude, and within an hour was whirling his tin pan with a skill quite equal to that of the American boy.

Rich! Rich was no word for it. They had struck a regular treasure hole, and besides occasional nuggets, every pan ran from three or four shillings up to three times that worth of dust.

Snell, Cray—everything else was forgotten, And it seemed no time at all before the quick dusk swooped down, and night put an end to their feverish activity.

They stuck to it till it was too dark to see, then, stiff and aching, limped back to the hut. There they lit the lamp, and turned out the contents of the two old meat cans in which they had been stowing their treasure.

The size of the pile of heavy yellow stuff made them gasp. They stood and stared, gloating over it.

"I reckon we've a pound weight." said Dudley at last. "About three hundred dollars' worth, I'd say."

Dick drew a long breath.

"Sixty quid for five hours' work! Four shillings a minute! My only aunt! You're right, Dudley! If we can only hang on here for a month or two, we'll be able to retire all right."

Then his hard common-sense came to his rescue.

"The sooner we hide this the better. We can't tell what minute Cray's gang may happen along. And it's up to us to feed well and sleep well if we're to carry on at this game again to- morrow."

Dudley nodded.

"That's good goods, Dick. Light the fire while I stow this. I'll bury it under that old log outside."

"That's a good notion. Put it down deep, and cover it up well. Then come and fix up some flap-jacks."

They made an immense supper, then arranged three-hour watches, each promising to wake the other punctually.

This time Dudley took first watch while Dick slept. The three hours passed like so many minutes, and he could hardly believe that he had closed his eyes before Dudley was shaking his shoulder.

"Just on eleven, Dick. And that queer noise has just started up afresh. 'Tisn't as loud as last night, but it comes every four or five minutes, just as before."

"It didn't do us any harm last night," replied Dick, rubbing his eyes. "So I'm not going to worry about it."

As before, the queer moaning went on at intervals for about an hour, then gradually died away. The night passed quietly, and next morning when the two visited the top of Look-out Hill the sea was as bare as it had been twenty-four hours earlier.

"Another day's work for us," said Dudley joyfully. "Come along, Dick! Every minute's worth a dollar!"

Strenuous was no word for the way in which the pair worked that morning. The gravel was as rich as ever, and they picked out no fewer than five nuggets, one of which was twice as big as that which Dick had got the previous evening.

It was long past midday before they broke off for a hurried meal, and by then they had another fourteen or fifteen ounces of dust to cache under the log.

"My word, but I'm stiff!" groaned Dudley, as he got up to put the plates aside. "I'll bet I never worked so hard in all my life before!"

"Nor I, either," replied Dick, going to the door.

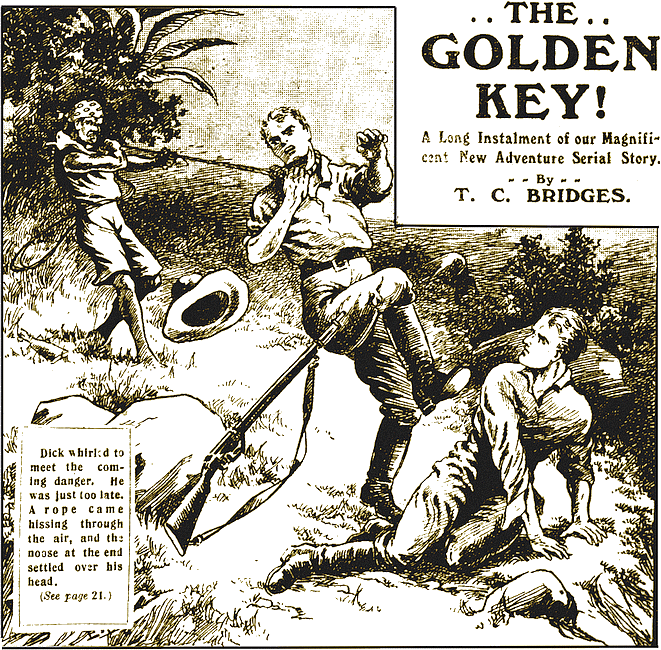

Crack! Phut!

Dick ducked like a dabchick, and leaped back into the house. As he did so a second bullet came ping! through the open door, and buried deep with a heavy thud in the wall opposite.

"The window, Dick!" cried Dudley, as he snatched up his rifle.

Dick slammed the door, picked up his gun, and followed Dudley like a flash through the window.

This put the bulk of the shanty between them and their assailants, and, stiff as they were, they both broke records in crossing the little pitch of open ground behind, and gaining the shelter of the trees.

Dudley was streaking straight away, but Dick overtook him, and caught him by the arm.

"The beach!" he panted. "Crooked Cliff! Here, round to the left!"

He swung in a half-circle, which brought them presently into the very thickest of the scrub. In this running was out of the question, and they were forced to moderate their pace. Presently the ground began to rise, and here Dick stopped.

"Wait a jiffy!" he whispered. "I want to know if they're on our track."

A distant cracking and swishing sound reached their ears.

"You bet they are!" replied Dudley, in an equally low tone. "It's up to us to scoot for all we're worth. Remember, the beach is all open! We want a long lead or they'll drill us as we cross it on our way to the cave!"

Dick nodded, and they were off again, making as little sound as they could. But the brush was thick and close, and tangled in places with long bamboo vines, tough as cord and covered with sharp, crooked thorns.

The sound of pursuit came closer, and—worst of all—came from more directions than one.

"They're spreading out!" muttered Dick. "There must be a lot of 'em. Watch out they don't get a sight of us!"

The brush began to thin again. It was lower, and there was more palmetto. By this they knew that they were getting near to the sea. But although Dick was aware that the general direction was right, he was not by any means certain whether they were going to hit off the break in the cliffs above the beach, and he knew that if they failed to do so they were absolutely enclosed. They would be caught between their enemies and the top of the cliff, and shot down at leisure.

A glance at Dudley's face showed it grim and set as Dick had never before seen it. Clearly he, too, realised how tight a place they were in.

Dwarfed by the strong sea winds, the palmetto became lower. It was hardly high enough to hide their heads. Their pursuers seemed to be gaining. They could be plainly heard, crashing through the harsh fronds of the palmetto, and cursing as they stumbled over the knotted rootstalks which seamed the ground in every direction.

"Duck!" whispered Dudley suddenly, and seizing Dick by the arm, dragged him down. "A nigger!" he said. "I saw a nigger's head above the brush, away over to the right. That ugly beggar Rufe Finn!"

"Over there?" repeated Dick, in dismay. "Then he's between us and the beach. We're done in!"

"There's only one thing for it," said Dudley firmly—"creep the rest of the way. They don't know where we are making, and if they come close we can hear them, and hide up in the thick."

Dick nodded.

"I suppose that's the only thing to do. But if they do happen to tumble across us—"

He did not finish his sentence, for at that moment the very catastrophe he had been fearing almost happened. A pair of legs, cased in rough high-boots, came crashing into view in a tiny open space not more than half a dozen yards away.

Dick and Dudley together dived in right under the nearest bush, and lay quiet as two rabbits in a gorse-clump. For some moments they hardly dared to breathe. Then the crashing, pounding feet passed on, and disappeared.

"That was Bent—Ambrose Bent," whispered Dudley.

"What—the moonshiner?"

"That's him. Great big brute, and ugly as sin."

"Ugly inside and out," added Dick. "Strikes me we're right up against it, old son."

"I could have drilled him all right," said Dudley regretfully.

"Just as well you didn't shoot. You'd only have brought the rest of the bunch on us. There don't seem to be any very close. Let's push on while we can."

They crept forward. The heat down here near the ground was almost intolerable, and the air was full of sand-flies and midges. Also, there was more than a little danger of snakes. But to these trials they hardly gave a second thought. Their enemies—some of them, at least—were now between them and the sea. Both knew that they were in about as tight a place as they well could be.

They could not choose their direction: they had to go wherever the bush was thickest. And they dared not raise their heads in order to see where they were going. It was only by the slight slope of the ground that they could tell that they were slowly approaching the sea.

Dudley stopped.

"I see daylight," he whispered.

Pushing the bushes aside, they found a yard or two of bare rock; beyond it, sheer cliff, with the waves breaking against its foot.

"Missed it!" groaned Dick.

"Yes: the cove's away to the right," said Dudley, peering out. "But, say, Dick, there's one good thing. Not one of 'em is anywhere near us. See there! They are right down on the beach."

"And right between us and where we want to go," added Dick.

"Gee! but they're a tough-looking crowd!" remarked Dudley. "I can see Cripps, plain as plain, just like an old buzzard hopping along. And there's Ambrose Bent and Rufe the nigger, and two more—five in all."

"And likely one or two more back in the scrub," growled Dick, pushing forward a little to get a better view. "Long odds any way you look at it."

"Might have been worse, I reckon," replied Dudley drily. "Say, Dick, they're looking for our boat!"

"I expect they'll look a while before they find it. Tide's high, and they can't get along the foot of the cliff. Just where are we, Dudley?"

"Right above our caves, I guess." He crept out a little further, then came back. "That's it. We're right on top of Crooked Cliff, and there's Hidden Bay over to the left, where the bushes hang over the edge."

"If there was only some way down from the top!" said Dick longingly. "This is no sort of a place to lie out. They're liable to find us any time if they beat the scrub through."

Dudley turned quickly.

"I reckon there is, Dick. Remember that deep little cleft that came down right on to the ledge?"

"Can't say I do."

"Well, I spotted it all right, and I wish I'd only had the horse sense to climb it and see if it was anyways possible."

"We might have a shot at it," said Dick eagerly. "It can't be very far off, either."

"No, the head of it can't be a great way off. But I guess if we're going to try it we've got to do it right now. Those fellows will be right back again as soon as they see there are no tracks on the beach."

Dick's jaw set.

"Right!" he said briefly. "Keep low, Dudley They won't spot us unless they happen to look this way."

"No need to go outside at all," replied Dudley. "Not at first, anyway. Keep right along, inside the palmetto."

It was good advice, and Dick took it. But the scrub was thick as a hedge, and it was terribly slow work wriggling along through the tough, saw-edged stems.

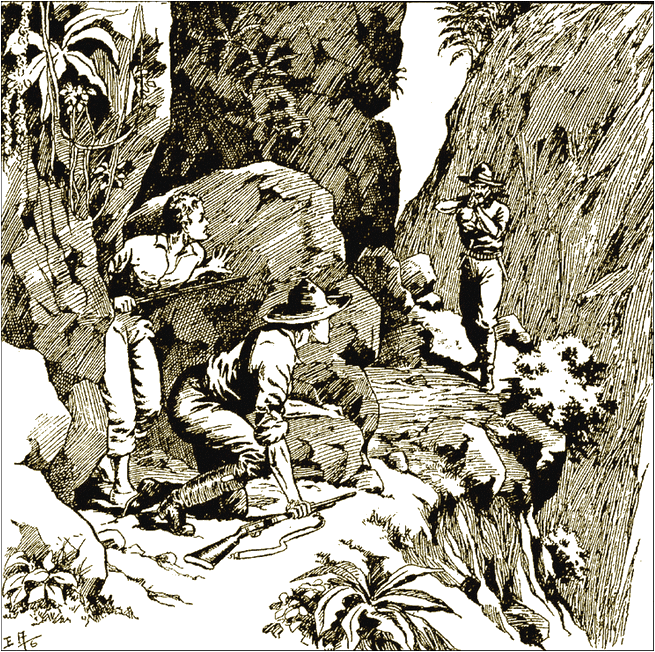

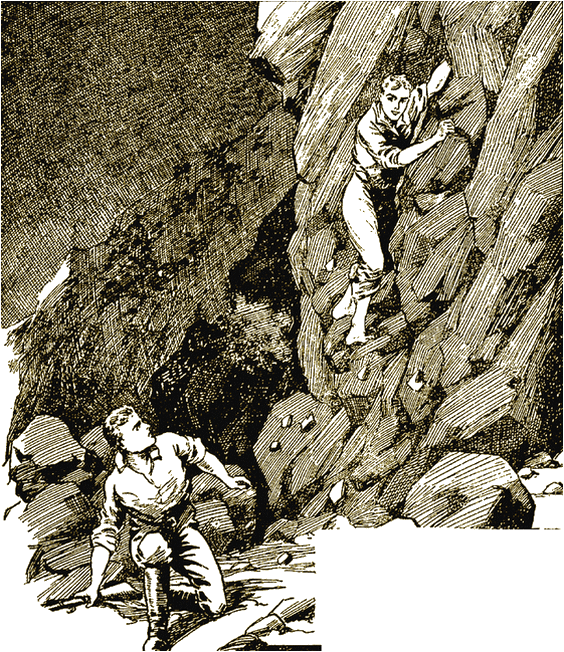

At last Dick, who was leading, came to a sudden stop. He turned to Dudley.

"Here's your cleft," he said.

Dudley came up alongside. Dick's head was over the edge of a wall of sheer rock. It was the cleft all right, but it was between twenty and thirty feet deep, and the bottom one mass of loose boulders, while the cliff-face itself was smooth, and sheer as the wall of a house. A monkey could not have climbed it. Worst of all, it ran inland, as far as they could see, until it grew so narrow that the palmettoes arched over it.

"A nice trap we've run into!" said Dick bitterly.

"GUESS there's nothing for it but to work inland and try and make the end of it," said Dudley.

Dick nodded, and the heart-breaking crawl through the palmetto began all over again.

It seemed endless, and every minute they expected to hear their pursuers crashing on their track. At last Dick ventured to peer out again. He gave a sigh of relief.

"We can make it here, Dudley."

As he spoke he slipped out, and, catching hold of a palmetto- stem which projected over the edge of the narrow ravine, lowered himself slowly. There was a slight rustle and a grating of loose stones.

"All right!" came Dick's voice: and Dudley, looking over, saw him safe at the bottom of the cleft, which here was no more than ten feet deep. Next moment he was beside him.

"Now I guess we've slipped them," said Dudley, with a sigh of relief.

The words were hardly out of his mouth before a rifle rang out. and his soft felt hat went whirling off his head.

For the moment he was confused, but Dick dragged him down behind a boulder big enough to shelter them both.

"It's Wilding!" he hissed in Dudley's ear.

Step by step Wilding decreased the distance separating him from the crouching pair, and all the time the black muzzle of his rifle promised death to the first that stirred. Now he was only twenty yards away, and the boys were forced to almost crush themselves against the ground.

Step by step Wilding decreased the distance separating him from the crouching boys.

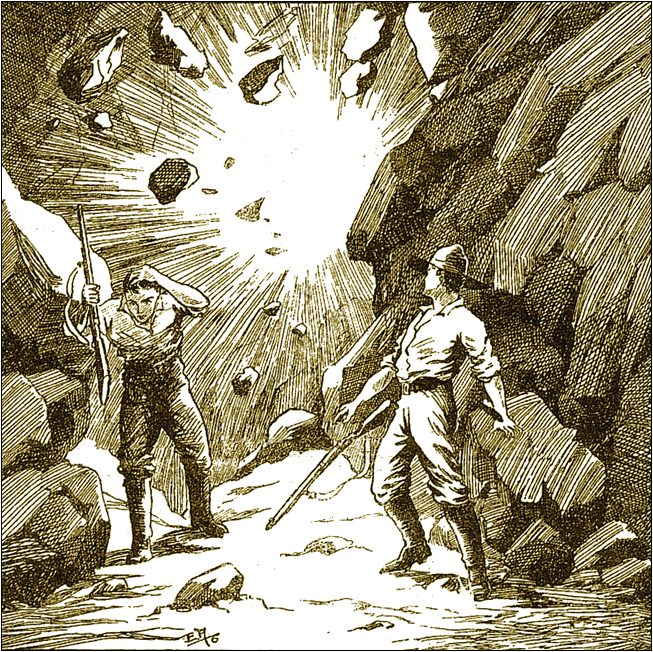

Then, without the slightest warning, there burst out a strange, hooting roar—the selfsame sound that the boys had heard last night and the night before. Only now it sounded infinitely louder than on either of the previous occasions.

Badly startled, Wilding's head jerked round, and for an instant the barrel of his rifle dipped. It was all the chance Dick wanted. Quick as a flash up came his gun, and he fired both barrels almost at once.

The roar of the reports filled the rocky cleft with a deafening bellow, which echoed and rolled like thunder, and two charges of heavy duck-shot, tearing through the air, struck Wilding at point-blank range.

With a yell, he jumped straight up into the air, to pitch, with a sickening thud, right down into the ravine, full on the masses of broken rock which littered the bottom.

For an instant Dick stood staring. His face had gone suddenly white, and he was shaking all over.

"Brace up!" said Dudley sharply. "Brace up, Dick! It was him or us. You had to do it. Run! There'll be more of 'em in two twos."

With an effort Dick pulled himself together, and they started down the ravine. They had to pass close by the shattered body of the man Wilding. It was not a pretty sight, and even Dudley, in spite of his brave words, shuddered as he glanced at the twisted face of the dead man.

As they struggled frantically forward over the heaped-up masses of rocks again came the geyser-like boom and hoot. But this they hardly noticed. They were both too busy in their wild struggle for life.

The slope became steeper. The walls on either side were so lofty that they out off the sunlight. The two moved in a shadowy gloom, so deep that they could hardly see.

Of a sudden they came to a monstrous rock which seemed to bar further progress, for it lay right across the ravine like a huge gate.

"Get on my shoulders, Dudley," said Dick, as he braced himself, with his hands against the rock.

Dudley clambered swiftly up, and stood on Dick's shoulders. He reached up.

"I can make it!" he panted.

Next moment his weight was gone, and Dick, looking up, saw him safe on top of the boulder.

Flinging himself on his face, Dudley stretched down, and Dick, with a leap, caught his outstretched hands. A frantic scramble, and he was beside his friend.

"The sea!" gasped Dudley.

And, sure enough, through the gap at the bottom of the gorge, the blue rollers of the gulf were visible, gleaming in the hot afternoon sun.

The rest of the way, if steep, was comparatively easy, and within another two or three minutes they were on their ledge, and had dashed into their cave.

Both flung themselves down. They were dripping with perspiration and panting with the fearful strain of the past half-hour.

Dudley was the first to recover himself.

"First trick to us, Dick. We've bagged one of them, and got off without a scratch."

"Speak for yourself!" growled Dick. "I haven't a sound inch of skin on my carcass."

Dudley laughed. It did him good to hear Dick joke. He had been afraid of the effect of the killing of Wilding, for he knew that Dick had never before fired a shot in anger. For himself it was different. He had seen rough work in the Far West before coming to Florida.

He struggled to his feet.

"Dick, we've got to get busy," he said. "Cray ain't going to waste any time over getting square. He and Bent'll be mad as hornets when they find Wilding. From now on, it's them or us!"

"It's been that from the first," answered Dick. "The swabs! Plugging at us without a word of warning! I tell you, Dudley," he continued, with a grim quietness that was rather impressive, "it will be shoot on sight from now on! We've got to rid the earth of this crowd, and I'll do it with as little pity as I'd blow out a nest of rattlesnakes!"

"That's right, old son; I'm with you!" agreed Dudley. "But our job now is to make sure they don't get first chance of plugging us. So I guess we'd better get busy, and make some sort of a breastwork. You've got to remember that, when the tide goes down, they can get along the beach just like we could, and then there's always the chance of their rushing us."

Dick nodded.

"You're right, Dudley. The sooner we start in the better."

There was any amount of loose stuff about, and they soon had formidable walls piled across the ledge at points which they could command from the cave-mouth. Anyone trying to reach the cave would have to climb one or the other. In the daytime they would be in plain sight; at night they would certainly make themselves heard by the fall of the small, loose stones which the boys had heaped on top of each barrier.

While they were at work the moaning roar was heard at its usual regular intervals, but after about an hour died away.

Dick and Dudley, however, had become so accustomed to the sound that they hardly paid any further attention to it.

The barriers finished, the two returned to the cave. What with their long morning at gold-digging, the chase, and the strenuous shifting of rocks, they were both pretty well done.

Dick looked round.

"I think we're all right for the present, Dudley."

"Yes, I reckon so. But what about it if they find where we are, and settle down to starve us out?"

"Take them quite a while," responded Dick, glancing at the comfortable-looking pile of tinned stuff and biscuit. "Old Ladd did us pretty well."

"I'm not thinking so much about grub." said Dudley. "Water's the question."

Dick's face fell.

"You're right, Dudley. I never thought of that. Well, we've got a keg full, anyhow. That'll last us till we can think the thing out. After all, we could surely make a sally by night, and fill up at the creek-mouth?"

Dudley shook his head.

"Cray's no fool, Dick. The water question is the very first that he's going to think of. Before he's twenty-four hours older he'll know, like we do, that the creek is the only drinking water on the island, and he'll take his measures accordingly.

"I must say you're jolly encouraging!" growled Dick. "If it's that bad, we'd best take our boat while we can, and sail back to Lemon Bay, and get help."

"I guess that's just exactly what Mr. Ezra Cray's figuring on." drawled Dudley, and pointed as he spoke.

Round the tall cape to the left a large sail-boat with a crew of half a dozen men had just come into sight. As they watched her the sheet was hauled, and she stood in towards the land.

Dick seized his gun.

"They're making right for the mouth of Hidden Bay," he said sharply. "Surely to goodness, they haven't got on the track of our boat already!"

"GUESS we'll have to fight for it, if that's their lay," said Dudley, as he slipped a clip of cartridges into the breech of his rifle. "We can't afford to lose our boat, whatever happens."

Lying flat on the bare rock behind a low breastwork of stone which they had erected before the narrow mouth of the cave, they waited to see what their assailants would do.

"No, they haven't spotted the mouth of the bay," muttered Dick Daunt presently. "See, they're passing it."

"Then what in the name of all that's queer are they after? Another minute and they'll be in range, and we can plug the whole outfit without a chance of their touching us."

As he spoke. Dudley raised his rifle softly and poked the muzzle through a chink in the breastwork.

"I don't believe they know where we are," said Dick.

"They're not such blame fools as all that," returned Dudley. "Old Ezra is about as cute as they make them. You can just bet he's got a very fair notion of our whereabouts."

Another minute dragged by, while the big boat, with the soft breeze filling her mainsail, came steadily towards them. It was deep water very nearly up to the shore, and the reefs which covered the entrance to the cove were a good way off to the right.

Dick raised himself a little.

"Great Scott, look at that!" he gasped.

"What's biting you?" demanded Dudley.

"A white flag! They're waving a towel, or something of the sort."

"Steady, Dudley!" he added quickly, as Dudley raised his head rather rashly. "It may be only a trick."

"I guest not. Looks to me like they want to come to terms with us."

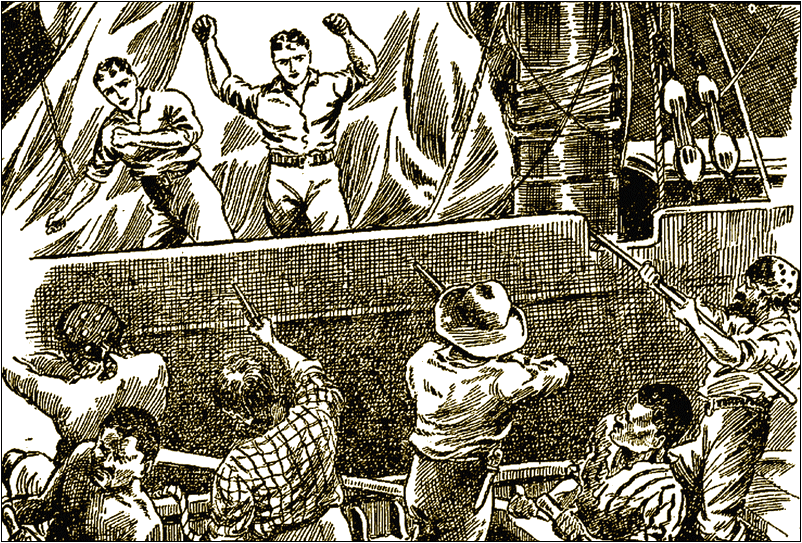

"Hi, yew, Daunt, be yew there?" came a high-pitched hail from the boat.

"You bet I am," returned Dick, poking his gun-barrel into view. "And ready to give you what's coming to you, too."

"None o' that!" came another voice, gruff as a foghorn. "This here's a flag o' truce as we're flying. Don't ye know enough for that?"

"I know you're a pack of cowardly murderers!" retorted Dick uncompromisingly. "You tried to plug us without any sort of warning, and you've about as much right to fly the white flag as a Venezuelan nigger. Haul your wind at once, or you'll get a dose of lead double quick!"

"That's the way to talk to 'em, Dick," said Dudley approvingly. "Ah, they're putting about in a hurry."

"Not so sure of that. Watch out for squalls, old man."

Ezra Cray, who was at the tiller, had certainly put the helm over; but instead of putting his craft on the other tack, he had merely thrown her up into the wind, so that she lay almost motionless, with her leeches quivering.

"You ain't got no call to talk to us like that," he shouted. "No one asked you to come butting in here, and ef you'd both been shot, it wouldn't hev been no more'n you deserved."

"I like your cheek," answered Dick. "We got the message to come to the old man's help."

"The mischief, you did!" snarled Gray. "I guess we 'uns all had it fust, and ef the old feller wuz loony enough to set another bottle adrift, thet ain't nothing to do with us.

"Now, see here," he continued, "you've hed luck in getting where you be, and I'm not saying you ain't safe so long as you stays there. But thet's only fer just so long as your grub lasts out. Then you've got ter starve or put your hands up."

"That's what you think," put in Dick defiantly.

"Oh, you may bluff all you've a mind to, but we knows! We knows as it's only a matter o' time and o' watching you. Now, see here. I ain't a hard man, and no more is Bent, here."

Dick chuckled, but Cray went on unmoved.

"You've shot up one of our fellers, but we don't bear no malice, and we'll make you a free offer. You kin get to your boat, load her up with the grub as you've brought along, and then git out. Give us your word as you won't come back or won't go shooting off your mouth to any o' the folk at Lemon Bay, and we won't interfere with you no more one way or t'other. There, ef that ain't fair, I don't know what is."

Again Dick gave vent to a hearty chuckle.

"'Pon my word, you are the bold limit! So we're to slope off with our tails between our legs, and leave you to mop up all the gold and generally raid everything worth having on the island. Is that the idea?"

"Thet's precisely the notion, young feller," answered Ezra. "And think yourselves mighty lucky as we've got sech good, kind hearts."

"Something between an alligator and a shark, eh, Cray?" put in Dudley. "No, my dear, kind-hearted friend, it won't work. I tell you straight, it won't."

"I shouldn't think it would," said Dick, in an undertone. "Even if we accepted their terms, they'd fill us with lead before we'd more than shown ourselves. They're just about as trustworthy as a pack of range wolves."

"Then you means to say ez you won't take these here terms?" shouted Cray, falling into a sudden rage.

"You can take that as said," answered Dick.

"Then, by gosh, you're jest as good as dead!" yelled Clay, in a rage. "You needn't to look for a second chance, even if you comes a-begging on your bended knees."

"Bet you you'll do the praying first," was Dick's final jeer, as Cray let the boat fall off, and she began to move again on the other tack.

The boys watched her as she sailed away.

"Why's he holding her so close to the wind?" muttered Dudley. "She's got hardly any way on her. There's no risk from those rocks."

"There's some dirty business on," answered Dick. "Jove, I've a mind to let 'em have it before they're out of range!"

The words were hardly out of his mouth when, as if at a given signal, all five of Cray's motley crew suddenly ducked down under the high gunwale, and five rifle barrels appeared instead.

The ragged volley sent the echoes crashing along the face of Crooked Cliff, and the bullets shrieked overhead or phutted harmlessly against the breastwork of rocks.

"Just what I was expecting," growled Dick. "Let 'em have it, Dudley! They're out of range of my scatter-gun."

Dudley had not waited for Dick's orders. He was already firing. His rifle, a sound if rather old fashioned Winchester, was of .44 calibre, and a bullet of this size is not only a man- stopper, but will penetrate a considerable thickness of wood and make a very nasty hole in a plank.

And Dudley, instead of snap shooting at the heads which just bobbed up above the gunwale, was firing deliberately at the boat itself, aiming as near the water-line as possible.

The first shot was short, and, striking the water, ricocheted over the boat; but the second hulled her, and at the third again splinters flew white, and there came a howl of dismay or pain from one of the crew.

In a hurry, Cray let her drop off, and she darted ahead at greatly increased speed, while her crew fired as fast as they could pull trigger. But apart from the difficulty of accurate shooting from a moving boat, the boys were safe enough behind their breastwork, and so long as the boat was within range Dudley, caring nothing for the bullets that sang and whizzed overhead, continued to fire carefully-aimed shots at the hull of the fleeing craft.

At last she was out of range, and, not wishing to waste ammunition, he ceased firing.

"Five hits, I reckon, Dick," he said quietly, as he turned to his partner.

"No, six," said Dick. "I counted. One was a bit high, but the rest got her right where she needed it. And I'll lay that more'n one of 'em went through both sides of her.

"Ah, watch 'em!" he continued, with a chuckle. "Bailing like billy-ho! Dudley, I'll bet that it will take 'em the best part of a week to make that old tub seaworthy again."

"Just about that, I guess," answered Dudley, chuckling softly. "Say. Dick, I kind of think that Cray's wishing he hadn't tried that trick—eh!"

"I wish I'd had a rifle too," said Dick regretfully. "If there'd been two of us to shoot, we'd likely have sunk the whole outfit, and got rid of the whole crew of skunks."

Dudley nodded.

"Yes, we ought to have helped ourselves to Wilding's rifle. Only I guess we were both so rattled just then we never thought of it."

"Good notion! We'll go out and fetch it. What do you say?"

"You mean before those fellows can land again?"

"That's the idea. I fancy they'll have to go round to the other bay, and, anyhow, they'll have to go pretty slow. The water must be fairly squirting into the boat, and they'll have to handle her mighty easy."

Dudley glanced again at the big boat, which was now just disappearing around the point of land to their left.

"Right you are Dick! This is our chance while they are out of sight. Let's only hope that none of their crew have been left ashore."

He paused.

"Say, you better let me go alone, and you stay here on guard," he suggested.

But Dick shook his head.

"No, Dudley. We'll slick together, whatever happens. And, anyway, that gorge is no place for one chap to go strolling alone. There's that big boulder to cross, and that's more than a one-man job."

"We'll take a rope to help us over that," said Dudley, and, picking up a coil which lay by the cave mouth, they started.

They wasted no time, but still they were not in such a tearing hurry as before. So the difficulties did not seem so great as they had previously, and, barring a meeting with a rock rattlesnake, a small, dark-coloured, evil-looking brute, which Dick killed by smashing a heavy stone upon it, they had no special adventures on the way.

Wilding's body lay where it had fallen, and Dick shuddered again as he noticed two great, dusky buzzards perched on the ledge overhead, their bare, wrinkled heads almost buried between their hunched-up wing-tips.

"He was a brute, but we can't leave him to those," he said. "We must bury him, Dudley."

"There's a deep crack between those two rocks," replied Dudley. "We can slip his body down there. I don't reckon that buzzards or anything else will get him there."

Dick nodded, and after taking the dead man's rifle and his cartridge-belt, they rolled the body into the cleft, and it dropped out of sight into unknown depths below. This dreadful business finished, they hurried back. The sun was already getting low, and there was still a good deal to be done in the way of making their position impregnable to attack.

"It's a good thing we have this way up inland." observed Dick as they reached the lower end of the gorge again.

"I don't reckon it will be much use to us," replied Dudley, shaking his head. "Ezra knows we've got Wilding, so I guess he knows how we escaped. Most like he'll put a guard somewhere up there ready to drill us if we do go out that way."

"I hadn't thought of that," said Dick slowly. "I expect you're right, old chap. Then in that case he may try to attack us from that side."

"That's so. We'll have to strengthen the breastwork that side."

Reaching the ledge, they slopped and took a cautious survey of the surroundings. But there was no sign of the enemy, and they reached the cave without seeing any.

By this time they were both pretty well done.

"What d'ye say to a mouthful of supper, Dick?" suggested Dudley. "Then we can fix up things."

"Better do it now," said Dick. "Won't be light enough after."

"Just as you say; but I guess I've got to have a drink first. My throat's like sandpaper."

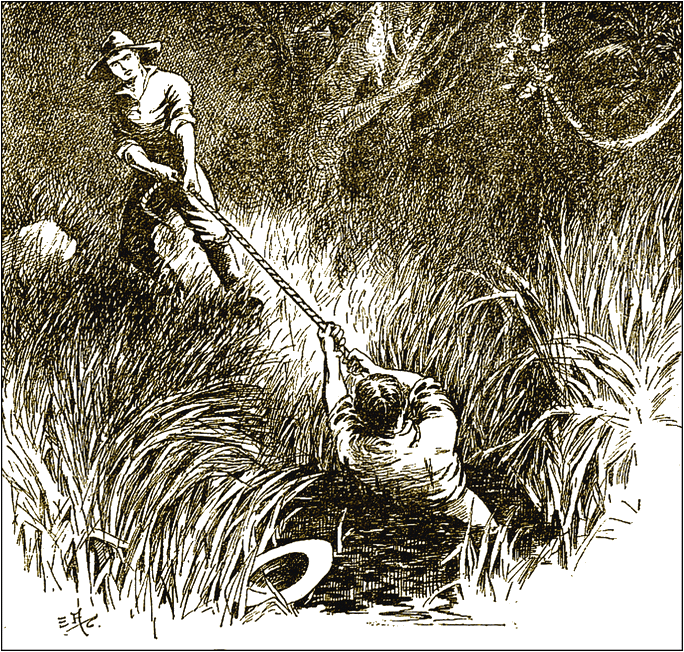

He got up wearily from the rock on which he was sitting, took up the cup, and turned to the five-gallon keg in which they had brought up their drinking-water. His cry of dismay brought Dick to his feet.

"The water—it's gone! There's not a pint left!"

Dick gazed, horrified, at the bullet hole which a chance shot had made in the keg.

DUDLEY was the first to pull himself together.

"Poor luck, Dick! But I guess it's no use crying over spilt milk, or spilt water either!"

"I suppose not. But unless one of us had been potted, they could hardly have hit us harder. There's not a drop of water anywhere up in these rocks, and it's precious unlikely to rain at this time of year. Cray knows that as well at we do, and he'll not run any chances of letting us get to the creek."

"That's so; but, for all that, he can't guard the whole length of the creek with half a dozen men. And the nights are dark now. Seems to me we ought to be able to hit off some place where the creek's not guarded, and fill the keg."

Dick shrugged his shoulders.

"We've got to do it, or die of thirst," he answered quietly. "Well, the first thing is to mend the keg, and the next to get a bit of sleep. We have to be fresh for this business. When do you reckon we'd better go?"

"Soon after midnight. That's the time that Cray's outfit are liable to be most sleepy."

"Right! We'll try it. Meantime, we may as well divvy up the remains of the water, and have some food. We'll have to leave those walls till to-morrow. I'm not expecting any attack for the present. Cray's policy will be to starve us out."

They boiled the remains of the water on their oil-stove, and it gave them just one cup of tea each. Then Dudley had the happy thought of digging out and opening a tin of peaches. These were floating in rich juice, which did as much to quench their thirst almost as the tea. They did not stint themselves, for they knew they would need all their strength and energy before morning, and although neither put the thought into words, yet both knew that if they failed to get the keg filled they would neither of them come back alive.

Dick took first nap, and Dudley, while he watched, carefully plugged the holes in the keg. By dint of beating out a piece of tin flat, and tacking it over the holes, he made a very good job of it.

No one disturbed the quiet of their haunt in Crooked Cliff, and not a sound betrayed the fact that there was a soul beside themselves on the island.

A little before one o'clock they started out. It was a warm, still night, and though there was no moon, it was lighter than they liked. The stars were brilliant, and down in these latitudes they give far more light than even on the brightest of summer nights in England.