RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Bush Boys," The Sheldon Press, London, 1930

"The Bush Boys," The Sheldon Press, London, 1930

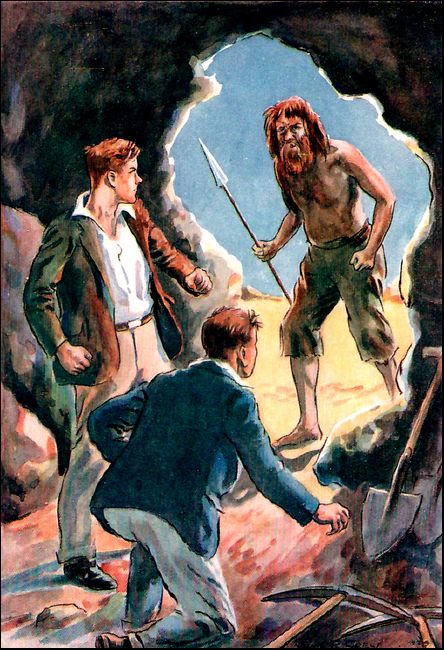

There was an ugly-looking spear in his right hand.

"ANY sign of Dad yet, Tad?" asked Bob Warburton, as he and Tad Kimber strolled up the wide sandy street of the little Australian township of Warragoola. The two were cousins and tremendous pals.

"The coach isn't in yet," Tad answered. "It won't be long now, though."

"I shall be jolly glad to see him," said Bob. "It seems more like a year than a month since he went to Brisbane. I do hope he has finished up that business of his all right. He was a bit worried when he went away."

Tad was not listening. He was pointing to a great swelling mound of yellow which rose above the high wooden fence surrounding the fair-ground. "Look at that, Bob?" he exclaimed. "What is it?"

"That? Why, I do believe it is a balloon. It is, too. And—and it's going up."

The two boys stood gazing as the balloon began to rise. Presently the whole great gas bag was visible against the rich blue of the Australian sky. Then the car came into sight.

"People in it!" gasped Tad.

"Yes, but it is held by a rope," added Bob. "I know. It is what they call a captive balloon. I say, Tad, I do wish we could go up."

A burst of jeering laughter made them both swing round. A tall boy, a year or two older than either of the cousins, and very smartly got up in pale grey flannels, was staring at them with a scornful expression on his sallow face.

"What's the matter with you?" demanded Bob. "What are you laughing at?"

"I'm laughing at you," explained the other. "Do you mean to tell me you have never seen a balloon before?"

A flush rose to Bob's sun-tanned cheeks. "No," he answered. "How should we? We've lived on a range all our lives."

"Do you mean to say you've never been to Brisbane or Sydney?" sneered the other.

"No!" Bob answered curtly.

"Well, I'm jiggered. There are some freaks up in these parts."

Tad cut in. "You're right," he said with a grin, and staring full in the tall boy's face.

An ugly expression came into the eyes of the boy in grey. He flushed angrily. "What d'you mean by that?" he demanded.

Bob explained. "Tad means that you are just as big a freak to us as we seem to be to you. And I dare say if you came out on our range there are others would tell you the same. Can you ride a brumbie or rope a bullock?"

The other looked a little embarrassed. "I'll soon learn. My father—he's the Hon. James Coppin—has just bought a big range up in these parts. A place called Warburton Downs."

"Warburton Downs?" repeated Bob. "What on earth are you talking about? That's my dad's place."

The other's eyes narrowed. "I know what I'm talking about if you don't," he retorted rudely. "Warburton Downs belongs to my father, not yours."

"He's clean crazy," said Bob shortly. "Come on, Tad."

The boy in grey grew furious. "I'll teach you to call me crazy," he shouted, and suddenly hit out at Bob. Bob dodged swiftly, yet even so, got a glancing blow on the jaw which staggered him. But only for an instant. Then he shot forward quick as light; there were two sharp smacks, and the long youth lay flat on his back in the dusty street.

"Look out, Bob!" shrieked Tad, and Bob jumped nimbly aside just in time to escape a vicious cut from the stick of a big, over-dressed man with a red face.

"You little reptile!" he roared. "What the blazes do you mean by assaulting my son?"

"He hit Bob first," cried Tad.

"It's a lie," shouted the other, aiming another blow at Bob. Again Bob dodged, then, instead of bolting, sprang in, seized the stick, and with a quick twist, wrenched it out of the big man's hand.

"It is perfectly true," he said in a tone which made the bully stare. "Ask him," he added, pointing to the boy.

The boy in grey had picked himself up and was standing with his handkerchief to his bleeding nose. Now he suddenly jumped at Bob and tried to snatch the stick from him. But Bob was too quick, and all the other got was a sharp prod full in his stomach.

He shrieked with rage and pain, and his father, crimson with anger, rushed at Bob, and pinning him against the wooden fence, got hold of him by the collar and started to punch him furiously.

But for Tad, it would have gone hard with Bob, but Tad had all his wits about him. Stooping suddenly, he caught the big man by one leg and jerked with all his might.

The big man, who was not expecting any such manoeuvre, lost his balance, toppled over and came down with a tremendous crash on the boarded side-walk.

Tad caught Bob by the arm. "Bunk!" he said briefly.

Bob hesitated. "Is he hurt?" he asked.

"It's you who'll be hurt if you stay here," retorted Tad, and Bob, seeing that his big enemy was already clambering to his feet, waited no longer, but followed Tad down the street.

"There's the coach coming," said Tad, pulling up as they rounded a corner, but keen as Bob had been to see his father, he did not even look at the sun-blistered old vehicle that came rocking over the plain, pulled by the four half-broken horses.

"What did that fellow mean?" he asked sharply of Tad.

"What fellow? Oh, the chap in the swell suit. Talking through his hat, I reckon," he grinned. "You're not taking any notice of what he said, are you. Bob?"

"N-no," replied Bob, but his tone was oddly uncertain.

Tad did not notice. "Come on," he cried. "Let's get to the hotel before the coach stops. It'll be jolly to see Uncle Robert again." He dashed off, and Bob followed.

"Hulloa, young Bob," called the driver cheerily to the boys as he pulled up his sweating team. "It's all right. I've brought your dad along." He bent down. "But he's not real well," he added in a lower tone. "You got to make him go slow for a bit."

"I'll see to that, Dempsey," said Bob, and ran to meet his father, who was just getting out of the coach.

"Bob, old chap," said Mr. Warburton.

Bob paused an instant. "Dad!" he exclaimed in a shocked voice. "Why—why, you are ill!"

"I'm not quite so fit as I might be," answered Mr. Warburton. "But don't worry yourself, lad. Come in. You too, Tad. I have to talk to you both."

Inside the hotel sitting-room Mr. Warburton sank wearily on a chair. "It's been a trying journey," he said feebly, "and—and I have bad news."

"Never mind the news, dad," said Bob, trying to pull himself together, yet so shocked at his father's appearance that he felt quite stupid. Mr. Warburton looked ten years older than when his son had seen him just a month earlier. His hair had gone quite grey and his eyes seemed to have fallen right back into his head. "Never mind the news," Bob repeated. "We must get you to bed!"

"Nonsense, Bob. I'm not really ill. It's worry. Sit down and listen to me, for I have to tell you at once, and I shall feel better when it's off my mind."

"I think I know already what it is," said Bob quietly. "You have had to sell the range."

Mr. Warburton's eyes widened. "How—how on earth did you know?" he asked hoarsely.

"I—we met a chap called Coppin. He said his father had bought Warburton Downs."

Mr. Warburton gave a sort of groan.

"We didn't believe him," broke in Tad. "We had a row, and Bob knocked him down. Then his father came up and interfered, so I tripped him and we hooked it. But, uncle, whatever made you sell the range?"

Mr. Warburton shook his head. "I did not sell it. These people proved their title to it, and the Court at Brisbane awarded it to them."

"Proved their title!" repeated Bob in a dazed voice. "I don't understand."

"How could you? You knew nothing of it. Nor did I until a month ago. That is why I went to Brisbane—to fight the case. Listen, Bob. The range came to me from my uncle, Joseph Warburton, and he had it from his father, Jabez, who was the first settler in these parts. But Jabez had a partner named Lemuel Coppin, who was grandfather to this Coppin. And it seems that the title was in his name.

"Now, according to my belief, Lemuel Coppin was a convict on licence, and therefore could not hold land. But this James Coppin has raked up old records to prove that his grandfather was not a convict, but a free settler. And now the Court has allowed his claim. So here are we, left landless."

"But the stock," said Bob quickly.

"I have sold nearly all the stock to fight the case."

"I see. You were quite right, dad." Bob paused. "I believe the whole business is a swindle," he added curtly. "These Coppins are a rotten lot. But never mind. Tad and I can work. We will soon start again, and if you'll promise not to worry, you can be jolly sure we won't."

"That's the way to talk, Bob." A gleam of real pleasure showed in Mr. Warburton's eyes. "While I have a boy like you I should be foolish to worry about anything else." Then his face changed. "All the same, Bob, it is a bit of a blow to lose everything at my age. And especially a place like the Downs, where I have lived all my life."

"It's rotten, dad," agreed Bob. "But I won't believe we've lost it for good. We'll get it back some day." Mr. Warburton shook his head. "Don't go building on that, Bob. There's not a chance of it."

"All right," said Bob quietly. "Then the sooner we start fresh, the better. And now I want you to go to bed."

"I won't go to bed. I'll rest here and have some tea presently. We will stay here to-night, and to-morrow "—his face twitched—"to-morrow we'll move."

"What—aren't we going back to the Downs at all?"

"No, Bob," said his father heavily. "Mrs. Carter will send our clothes and luggage. I could not bear to see the place again now it is no longer mine."

"Right you are," said Bob. "But if you won't go to bed, lie down on the couch for a bit. You badly need a nap."

His father agreed, and inside five minutes was sleeping soundly. "Absolutely played out," whispered Bob. "Tad, you and I will go out and stroll a bit and come back for tea."

"THIS is a rotten business, Bob," said Tad, as the two boys walked up the street in the hot sunshine. Tad, short, stocky with a round face and carroty hair, was usually the most cheerful soul, full of jokes and fun, and Bob had never before heard him speak so solemnly.

"Yes, Tad," he said. "It's no use trying to pretend that it is anything else. I've hardly realised it yet. And the worst of it is that it's a swindle."

"How do you know it's a swindle?"

"I don't know. I just feel it."

"I'm with you, Bob. Those Coppins are a bad lot, and I believe that fat man would do anything for money." He thought a while. "Can't we do anything?" he asked.

"There's one thing we've jolly well got to do—keep dad cheerful."

"Of course, but it's going to be a job, Bob. What I mean is, can't we do anything about those Coppins?"

"I don't know. We must try and find out something about them."

"Let's follow them. They were going to the Show when we met them."

"Right! I've got some money. We'll go in." Admission to the fairground was only a shilling, and the two boys found themselves in the crowded enclosure with cattle, horses, sheep, and pigs in pens all round. They walked about for some time, but could see nothing of the Coppins. They bought a packet of ginger nuts and some chocolate at a stall, and presently found themselves close to the balloon. Bob stopped and stared at the notice:

ASCENTS EVERY HALF-HOUR.

SPLENDID VIEW OF THE FAIR GROUND, THE TOWNSHIP

OF WARRAGOOLA AND THE SURROUNDING COUNTRY.

TICKETS FOR THE ASCENT 5s. EACH.

"Come along, young fellers," said a man in charge. "Just going up. See here. The folk here ain't half doing their duty. They're scared, or something. I'll let you have a chance at half price."

Bob hesitated.

"Come on, Bob," said Tad. "It's a big chance. Tell you what," he added in a lower tone, "we can have a last look at the Downs."

That settled it. Bob produced the five shillings, and he and Tad got into the car, which was a basket about five feet across and three feet deep. Sand-bags hung over the side. Also, there hung there a coiled rope with an anchor. Above was the great spherical bag of yellow canvas. It looked huge, and was, in fact, fifty feet in diameter. Canvas pockets lined the inner walls of the basket. Bob noticed that one held a pair of powerful field-glasses. The balloon itself was held down to a small traction engine by a hempen cable which was rolled upon a steel drum.

The man in charge was trying to beat up more passengers, but they seemed shy of venturing. Bob and Tad, busy examining the car and the balloon, paid no attention to anything else, until suddenly someone scrambled over the side into the car. Then they both looked round.

"You!" said Bob in a distinctly hostile tone as he recognised the boy in grey. The latter glared back.

"Yes, it's me," he retorted, "and if you don't like it, you had better get out. I've paid my money, and you don't get me to move."

"Don't worry, Bob," said Tad. "Come to that, we've got something better to look at than him."

Jed Coppin snorted, but made no other reply, and at that moment the drum began to clank. "We're off," cried Tad, and sure enough the balloon was rising slowly, tugging at the great rope which held it. Bob and Tad promptly forgot all about their unwelcome companion, and Jed Coppin himself, in spite of his boast about all he had seen, was almost equally interested.

Up and up crawled the big balloon, to the clanking music of the drum. The people below seemed to get smaller and the fairground appeared to flatten out as the balloon rose.

"How high does she go?" asked Tad.

"Five hundred feet," replied Bob. "I say, Tad, look! We can see the range quite plainly."

"And the house and the dam," added Tad.

"Is that Warburton Downs?" questioned Jed Coppin.

Bob swung round on him. "Yes, that's the place you've swindled us out of," he said bitterly.

Jed's sallow face reddened. "Don't you dare talk like that, or I'll throw you out," he snarled.

Bob's fists clenched, but Tad caught hold of him. "Wait till we get down," he advised. "No use fighting up here. Besides, we want to see all we can."

Bob subsided. Tad had got out the field-glasses and was focussing them. By this time the balloon was nearly at her full height—so far, that is, as the rope allowed her to go. She tugged and strained at the cord and lay over at a considerable angle. While it was still enough down below, up here there was quite a stiff breeze.

"Look at that chap below," said Tad suddenly. "What's the matter with him? Why is he chucking his arms about like that?"

"Only giving the signal to haul us down," answered Bob.

"But why? We haven't stopped going up yet."

The words were hardly out of his mouth before the answer came. A violent gust of wind coming from the east caught the balloon and flung her sideways with such force that all three boys were forced to cling to the ropes to save themselves from being thrown out. Then, just as it seemed as though the great gas-bag would be torn to pieces by the gale, there was a crack like the report of a field gun, and the balloon leaped skywards.

"Oh, what's happened?" shrieked Jed Coppin.

Tad leaned towards him. "The rope's busted," he explained. "The rope's broke, and now you're going to see something you never saw before."

JED COPPIN'S sallow face went lemon yellow, he dropped back limply on to the sand-bags in the bottom of the basket and lay gasping like a stranded fish.

Tad craned over the edge. "Look at them, Bob, they're running like rabbits." Sure enough, there was fearful excitement below. People were rushing this way and that and pointing upwards, their upturned faces looked like white dots against the dark background of the crowd. Their shouts came up thinly through the wind.

"They can't do anything to help us," remarked Bob, who was taking it very coolly.

"Of course they can't," said Tad. "I say, she's going up like smoke. Everything's getting smaller and smaller down below."

"I know, and it's getting jolly cool," responded Bob. "I say, Tad, what happens if she goes too high? Does she bust?"

Jed heard, and a howl of terror escaped him. "Let me out," he shrieked. "I won't stay up here."

"There's nothing to stop you getting out," remarked Tad politely. "But it's a long way down—about three quarters of a mile, I should think."

Jed subsided again, moaning, and Tad turned to Bob again. "Bob, isn't there some way of letting the thing down? She's travelling like one o'clock. We're a mile and more from the fairground already."

"Funny!" said Bob, frowning. "I can't feel her move."

"Of course you can't, because she's just like a bubble. She goes with the wind, so of course you can't feel the wind," said Tad sagely. "But what about getting her down?"

"I don't know," said Bob doubtfully. "I believe I've read that there's some way of letting out the gas."

"Then we'd jolly well better do it, or we shall have to walk about half-way across Australia."

"Wait—let me think," said Bob. "Yes, I remember. There are two cords, one for the valve and one they call the rip cord. The valve cord's white and the rip cord is red."

"I can only see one cord," said Tad, "and that's red. Shall I pull it."

"For heaven's sake don't," said Bob hastily. "That rips the whole bag open and we should come down like a stone. The white is the one to pull, for that lets the gas out slowly. Where the dickens is it?" The two boys stared upwards, and suddenly Tad pointed. "There it is—right inside the bag."

Bob whistled softly. "It must have switched up there when that gust caught us. What about it? Shall I try and climb up and get hold of it?"

Tad shook his head. "Too big a job, Bob. I couldn't do it and I don't believe you could."

"I don't believe so either," agreed Bob, quite honestly.

Jed woke up again. "You've got to do it," he cried. "I can't stay up here. I—I've got to get back."

"Then why don't you do it yourself?" retorted Tad. "Go on!" He stirred him with his foot as he spoke.

"Me!" shrieked Jed. "Me climb up there! You're crazy."

Tad fixed him with an unfriendly eye. "About an hour ago you were laughing at us and bucking about all you'd done and seen. Here's your chance to make good. Get to it."

Jed flung his arms around one of the sand-bags and clung like a limpet in the bottom of the car. "I can't. I won't," he shrieked. "I've got no head for heights."

"Nor for anything else," snapped Tad. He turned again to Bob and whispered in his ear. "Rather a joke taking this blighter away into the bush," he said. "It'll give him and this unpleasant father of his a jolly good lesson."

"I'm not wasting any pity on them," said Bob drily. "It's dad I'm thinking of. He'll be awfully worried."

"Oh, he'll know we're bound to come down safe some time or other," said Tad comfortingly. "A balloon doesn't stay up very long. The gas leaks, I believe."

"Not much sign of any leak at present," returned Bob. "She's still going up."

Tad looked down, and saw that Bob was right. The balloon was now four or five thousand feet up, and still travelling at a tremendous pace. Warragoola was nothing but a few little dots on the eastern horizon, and even their own house, Warburton Downs, was a long way to the east. Beneath was the last of the big paddocks, an area of over three thousand acres, where cattle, looking like little red and white specks, were grazing. Beyond again were low hills covered with scrub.

"I don't half like the look of it," said Tad at last. "I'm strongly inclined to take a pull on that red cord and chance the consequences."

"It's a long way to fall," said Bob gravely. "I think we'd better hang on. I remember reading that gas contracts with cold, so I expect that, as soon as the sun sets, she'll come down by herself. There are several big places beyond ours, and we shall be all right if we don't get carried beyond the State line."

Tad's eyes widened. "Beyond the State line!" he repeated. "Great snakes, Bob, that's all of two hundred miles. You aren't reckoning we'll go as far as that."

"I hope not," said Bob, "If we did we should be in the soup, for beyond it's nothing but spinifex and granite. But don't worry. We aren't travelling more than thirty or forty miles an hour, and it will be sunset in an hour and a half."

"We'd best sit tight then," Tad said. "I say, Bob, is there any grub aboard? I'm feeling a bit peckish."

Canvas pockets lined the inside of the basket, and Bob began to examine them. His first find was a pair of powerful field-glasses, his next a small kit of tools, which included a couple of wrenches, a screw-driver and gimlet. Then he pulled out a thermos-flask, but this was empty, some enamel iron cups and plates, three knives and three forks and finally a large metal flask. "This has something in it," he said as he shook it. He unscrewed it, smelt it and made a face. "Whisky or something of the sort." He was just going to chuck it over when Tad stopped him. "Hang on to it, you ass. It might be jolly useful if one of us got snake bitten."

"Snakes!" Jed woke up again in a fresh spasm of fright. "Are there any snakes where we're going?"

"Heaps of 'em," said Tad remorselessly. "Carpet snakes that'll squeeze you to death and tiger snakes whose bite kills you in ten minutes."

"Shut up, Tad," said Bob. "You'll scare him into a fit."

"Not much loss," retorted Tad. "Chap who bluffs like he has and then goes to bits the first minute anything's wrong don't deserve any sympathy."

"You leave him alone, anyhow," said Bob with decision, and Tad, though in most things he took the lead, merely grinned and obeyed.

Bob went on examining the pockets. "Nothing else," he said.

"What—no grub!"

"Not a mouthful!"

Tad's face fell. "That's rotten. What the mischief do they mean by sending up a balloon without any grub?"

"They didn't expect it to fly away, you juggins," said Bob. "And anyhow we've still got quite a lot of that chocolate we bought at the stall."

"Good egg!" exclaimed Tad. "I'd forgotten that." He hauled out a stick, and was just going to start on it when Bob stopped him. "Better keep it for brekker, old man. We may come down a jolly long way from the nearest house."

"Perhaps you're right," agreed Tad rather reluctantly. "Well, if we can't eat, let's make ourselves comfortable."

"Comfortable!" said Jed bitterly. "How can you be comfortable in this beastly little basket? And I'm frightfully cold. I shall have a sore throat after this, I'm quite sure."

Tad shrieked with laughter. "Poor dear! Will it catch cold?" he jeered, but Bob gave him a dig with his elbow and told him to dry up.

It was not really cold, but it seemed so in comparison with the baking heat which they had so recently left. The worst of it was that they were all wearing light clothes, and of course had no overcoats or anything of that sort.

"Tell you what," said Tad. "I'm going to cut open one of these sand-bags and use it for an overcoat. It'll do fine."

With his knife he split the top of the bag and set to emptying the fine dry stuff over the rim of the basket. Bob gave a sudden yell. "Stop that!" he shouted. "We're going up like a rocket."

Tad stopped, but the mischief was done. The balloon had jumped at least two thousand feet, and if it had been chilly before, now it was cold in earnest.

"YOU are an ass, Tad," said Bob.

Tad looked injured. "How was I to know I'd upset the balance of the beastly thing like that?" He shivered. "My word, but it's properly cold now!"

"I'm freezing," groaned Jed, his teeth chattering.

"Swing your arms," Tad told him, as he began beating his own arms across his chest. But Jed was too scared and miserable to follow his example, and lay shaking and shivering while the big gas-bag drove on across the Continent. The sun was getting low and the sky was a splendour of scarlet and gold. There is no place to match the car of a balloon from which to see a sunset, but the three occupants of the car were in no mood to appreciate the beauties before them.

"There's a creek below us," said Bob. "I believe it's the Mort."

"The Mort," said Tad, horrified. "We haven't come as far as that already."

"Yes, it's the Mort all right. I can see the Standish hills beyond."

"But that means we've come a hundred miles already!"

"I expect we have. We've been going an awful bat ever since you let that sand out."

"Oh, well, we can't help it," said Tad recklessly. "One good thing, we can't be carried out to sea."

"We could if the wind changed. We might be taken right up into the Gulf of Carpentaria."

"It don't look like changing at present," said Tad, and after that both fell silent.

The sun dropped behind a range of low hills far to the West, and since there is precious little twilight in the Tropics, the country beneath was soon wrapped in dark shadow. As the sky darkened the stars came twinkling out.

"One thing, it ain't getting any colder," said Tad at last.

"No, we've dropped quite a lot."

"How do you know?"

"By the barometer, juggins," said Bob, as he pointed to a small barograph set on one side of the basket. "We're back at about two thousand."

"Is that all she's come down?" grumbled Tad.

"It's quite enough," replied Bob. "We don't want to go bumping into some beastly mountain in the dark."

"I hadn't thought of that," said Tad in some dismay. "My word, we'd better keep a look out. Are there any mountains this way?"

"If I knew what the way was I could tell you," said Bob drily. "So long as we're going due west I don't think there's anything except a few low ranges. All the same, we'll keep an eye lifting."

"All right," said Tad, "we'd better take turns. That beggar Jed's asleep already."

"I'll take first watch," agreed Bob. "You get forty winks."

Tad curled up as best he could, and was asleep in no time, and Bob sat watching. A balloon differs entirely from an aeroplane, in that it floats in perfect silence, and at first this silence was broken only by the noises Jed made while he slept. Sometimes he groaned, then he gnashed his teeth and then he muttered. Tad breathed softly and regularly.

Bob kept careful watch on the ground below. Twice or thrice he saw lights, but by degrees these grew scarcer, and finally vanished altogether. For a time all was silence; then a weird thin barking came up from below, the voice of a pack of dingoes or wild dogs hunting. Bob strained his ears for the bellow of bullocks, but heard nothing of the kind.

It was an eerie experience floating through the dark over the unknown with nothing to tell how fast they were going or in what direction. He did not even know what the time was, for, though he had an old silver watch, it had not a luminous dial, and he did not want to strike matches, for he knew that lights were dangerous under a gas-filled envelope.

Hours seemed to pass, and then all of a sudden he became conscious of a dark mass just ahead. He saw in a moment that it was a range of mountains, and it looked as if the balloon would charge straight into them. Leaping up, he seized the sand-bag which Tad had already partly emptied and poured the rest of the sand over.

Up went the balloon with an incredible leap, and in a moment the mountains had faded into the depths beneath.

The others did not stir, and Bob waited a long time before rousing Tad.

"Gosh, I thought I'd only just gone to sleep," exclaimed Tad.

"I'll bet it's nearer daylight than sunset," replied Bob. "Keep your eyes lifting, Tad. We nearly knocked a mountain down about an hour ago."

"Where are we now, Bob?"

"We haven't got to sea yet, that's all I can tell you. I saw the stars gleaming on something like water just now, but it might have been a salt pan."

"All right. I'll take over. That bag I was sleeping on is the softest."

Bob lay down, closed his eyes, and the next thing he knew Tad was shaking him by the shoulder. "Dawn's coming, Bob, and—and we're in the middle of about a million miles of desert."

Bob sprang up. The stars had dimmed and the grey light of dawn was stealing over the sleeping world. He looked down, and his heart sank within him. Desert! He had seen desert before, but never anything like this. Sand and Spinifex, and here and there a line of mulga scrub marking a dry creek. That and nothing else so far as eye could see.

THE balloon was lower now. It drifted along only seven or eight hundred feet above the dreary waste. The breeze had fallen light, and the balloon was moving quite slowly—not more than twenty miles an hour. Bob looked up at the gas-bag, and saw that it seemed shrunken and wrinkled. A lot of gas must have escaped, or else the cold of the night had contracted it. "She'll come down pretty soon," said Tad.

"If she does it'll be our finish," said Bob grimly. "That sand below will be like an oven an hour after sunrise, and I'll swear there's no water within twenty miles—maybe not within a hundred. Our only chance is to dump some ballast and go up again."

"I expect you're right," said Tad, and Bob noticed with dismay that his cousin's voice had gone dull and lifeless. Surely Tad was not losing heart! Then he remembered the strain of all those hours of lonely watching, and understood.

"See those hills," he said briskly, pointing to a low range of granite on the horizon. "We'll let her go as she is until we get nearer to them, then if there's water we might be able to drop down and get some."

"Good enough," agreed Tad. "I say, what about a bite of chocolate? I'm as empty as a drum."

"Just a bit," agreed Bob. "But we'd better only have a bit apiece. It'll make us fearfully thirsty."

"Give me a piece," said Jed, so suddenly that both the others started. They had thought Jed was asleep.

"All right," said Bob, as he broke one stick into three and divided it.

Jed munched his hungrily. Then Tad, who had been staring at him, spoke suddenly. "Haven't you got anything with you—any grub, I mean?"

Jed's sallow face reddened. "No," he began—"at least only a few bits of toffee."

"Fork it out," ordered Tad curtly.

"I—I won't. Why should I? I bought it."

"And I bought that chocolate which you're eating," replied Tad with deadly calmness. "Fork it out, you blighter."

Jed glared at Tad. He looked as if he would go for him. Bob cut in. "Hand it over at once, Coppin," he ordered, and this time Jed obeyed. His pockets were simply bulging with sweets. He had half a pound of toffee, three sticks of almond rock and a big bag of mixed chocolates rather squashed, but still quite good.

"Well, if you aren't the limit," said Tad bitterly. "All that stuff stowed away, yet you'd bag ours as well. Aren't you ashamed of yourself?"

"No," snarled Jed. "You got me into this fix. I don't see why I should help you out of it."

"I got you into it!" Tad's eyes blazed, his fists tightened. Jed scrambled to his feet. Another moment and the two would have been at one another hammer and tongs, when a sharp cry from Bob interrupted them. "Look! People running. A girl and natives."

Forgetting everything else, the other two turned and hung over the side of the basket. "The girl's white!" exclaimed Tad in extreme astonishment.

"And—and she's running away from those black men," gasped Jed.

"That's about the size of it," said Bob sharply. "And look at the beggars. They've all got waddies and spears. My word, they're going to kill her."

It looked indeed as if he was right. The girl, who seemed to be quite young, was running hard across the desert. They could see that her legs were bare and that she had neither shoes nor stockings. She was running at a most amazing pace, simply scooting across the sand, chased by eight big blacks all armed. Fast as she went, the blacks were gaining, and it was plainly only a matter of a few minutes before they caught her.

Bob felt his throat go dry, and Tad shook all over. Even Jed went quite white.

"And we can't do a thing," groaned Tad.

"We can," cried Bob. "We must." And without another word he seized the red cord and jerked it.

There was a harsh splitting sound, and as the gas began to whistle out of the torn envelope the balloon began to drop. She was only a few hundred feet up, and luckily there was hardly any wind at all. More luckily still, the pull which Bob had given had not been hard enough to rip the fabric right across.

Even so, the balloon fell pretty fast, the basket swinging from side to side so that the three in it had to cling to the ropes.

Jed screamed with terror, but Tad was quite steady. "Hang on to the ropes," he said to Bob. "It'll take the jar off a bit."

Bob seemed hardly to hear. His eyes were fixed on the girl, who was still running hard, and now almost beneath the balloon. But the blacks were gaining. "They'll get her," he gasped. "They'll get her before we get down." All of a sudden he stooped, grabbed a sand-bag and lifting it with both hands flung it with all his force at the blacks.

The odd thing was that the natives had never even seen the balloon. Their whole attention had been so fixed on the girl that they had none left for anything else. The bag dropped right in front of the first, caught his ankles, and he came a lovely header. The others looked up, saw the balloon dropping out of the skies on lop of them, and, screaming like lost souls, turned and ran for their lives. The leader, the one who had fallen, picked himself up, gave one dreadful yell and followed. If he had been running fast before it was nothing to what he did now.

"Hurray!" roared Tad. "Good for you, Bob!"

"Chuck out some more sand," said Bob swiftly, as he seized another bag and dumped it. The pace of the fall checked, the balloon dropped gently to the ground and Bob and Tad jumped out. "Where's the girl?" asked Bob, looking round. But there was no sign of her. She seemed to have vanished like a ghost.

There the two stood alone in the centre of a huge waste of sand, rock and spinifex with a huge red sun just climbing over the bare hills to the east.

"WHERE'S that girl?" asked Bob in a very puzzled voice.

Tad was already searching, and suddenly he swooped down on a patch of prickly spinifex. "Here she is," he said. "My word, but she's a rum-looking lady."

The girl had dropped and hidden just like a wild animal, but now, finding that she was discovered, had risen to her feet and stood gazing at the boys with her eyes wide open and her lips parted. She was still panting from her terrible race, and Bob saw that she was badly frightened.

She was the strangest-looking object, for the only clothes she wore on her poor skinny little body were a short skirt of opossum fur, and an upper garment that seemed to be made out of a piece of sacking. No shoes, no hat, and her skin, though she was undoubtedly white, was burnt to a rich red by sun and wind.

"Who are you?" asked Tad. "Where do you come from?"

Her lips moved, but she did not speak. She reminded Bob of a trapped rabbit. "Go slow with her, Tad," he said in a low voice. "She's simply a white savage, and you can see she's scared stiff."

"You tackle her, Bob," replied Tad. "We've got to find out where we are, and she's the only person who can tell us. We shall be absolutely in the soup if we're stranded here without water."

"All right," said Bob, and taking a stick of chocolate from his pocket he broke it in two and offered half to the girl. The other piece he put in his own mouth. She stared at him, then very slowly followed his example. The moment her teeth met in the chocolate her whole face changed. A look of amazed delight showed in her eyes, and gobbling up the delicious mouthful, she stretched her hand for more.

Bob smiled. "Give you some more if you'll find us water," he said.

"Ain't you got no water?" The girl's voice was a sort of cockney whine, different from anything Bob or Tad had ever heard. "Funny blokes you be ter come 'ere without water."

"We didn't mean to come," Bob explained. "The balloon broke away."

"Wot's a berloon?" asked the girl, who seemed to be getting over her fright.

Bob pointed to the wreck of the balloon. "That. It is a gas-bag. Floats in the air. We've come hundreds of miles in it since yesterday."

"Floats in the air," repeated the girl. "Is that strite?"

"Quite straight," smiled Bob.

"I sye, you do talk funny," said the girl, showing while teeth in a smile. Then she turned grave again. "But yer'd better get in and fly awye agin quick as yer can. Ef yer don't Blyne'll get yer."

"Who's Blyne?"

The girl shivered. "Him wot I'm runnin' away from."

"You were running from blacks," said Bob.

"Them blackfellers took arter me arter I left their camp. I wish yer'd killed 'em," she added fiercely.

"We pretty nearly scared them to death," said Bob. "But I say, what about the camp? Where is it? And you haven't told me who this chap Blyne is that you were running away from."

The girl looked at him sharply. "'E's a dirty dog, 'e is," she said, and shivered again.

"Is he there now?"

"Aye, 'e's there right enuff, an' puttin' Saul and all through it proper."

"Who's Saul?"

"My dad."

"You weren't running away from him?"

"No, I told yer I were runnin' from Blyne."

"But where to?"

"Anywheres so as ter get awye." A sullen look crossed her face, and she said no more.

"This is a queer sort of business," said Tad to Bob.

"I should jolly well think it was. But we've something to go on. There's a camp somewhere near, and the girl's father lives there and a man called Blyne—I expect it's Blayne—is there, and raising Cain with them."

Tad nodded. "See here, Bob, where there's a camp there must be water, and we've got to find water. I'm thirsty as blazes already, and in less than two hours we shall all be pretty near crazy if we don't get a drink. We've got to chance Blayne and get to the camp."

"That's about the size of it," agreed Bob. "I'll try and get her to take us to the camp."

He tackled the girl again. "I say, what's your name?"

"Tib," she answered.

"That's rather a nice name," said Bob tactfully. "Well, see here, Tib, we've got to have water. And so have you. Won't you take us to your camp?"

Tib shrank away. "I won't. Blyne'll kill me."

"Not if we are with you," said Bob stoutly. "We'll tackle Blayne."

"You ain't skeered of 'im?"

"Not a bit," vowed Bob.

"'E'll put yer to work, 'e will."

"We'll chance that," laughed Bob, and oddly enough the laugh did the trick, for poor little Tib had a sort of reeling that anyone who could laugh at the dreaded Blayne could not really be afraid of him. "I'll take yer to the creek," she said simply. "Then I'll 'ide until yer 'as killed Blyne."

Bob gasped. He couldn't help it. The deadly simplicity of Tib's words proved more plainly than anything what he and Tad were up against.

Jed, who had been standing listening in a dazed sort of way, spoke. "Who is this Blayne?" he asked. "You know as much as we do," Tad answered.

"B-but he must be an awful brute," faltered Jed.

"Certainly sounds like it," agreed Tad drily. "But the three of us together ought to be able to handle him."

"I—I think I'd better stay here," said Jed.

"Just as you like," said Tad. "But there's no water, and you'll be dead of thirst before night. You'll find it a lot easier to be killed than to die of thirst."

"Shut up, Tad," said Bob sharply. "It's all right, Jed. Tib will take us to the water, and after that we'll have a squint round before we tackle this Blayne person. Come on, Tib."

"Wait a jiffy," said Tad. "We want the glasses and things from the balloon." He took the things out of the pockets of the basket—the tools, the thermos, the cups and plates, knives, forks and finally the flask, and divided them into three lots. Each took one, and they started off.

Though the sun was not half an hour up it was hot, and getting hotter every minute, and Jed soon began to lag. Tib looked back at him. "'E ain't no good," she said scornfully. "Wot did yer bring 'im for?"

Jed got very red, but he was too blown and his mouth was too dry to resent openly Tib's remark.

Tib led towards the low range of granite hills. Bob saw that she was very scared. So was he, for that matter, but not for the same reason. It was the natives he was thinking of, for he knew well enough what brutes the blacks are, and that if the tribe was anywhere near, his life and those of this three companions were not worth a brass farthing. Tad, too, was not happy, and kept looking round. "If we'd only got a gun I should feel a lot more comfortable," he whispered to Bob.

It was only about a mile to the hills, but the sand was deep and soft and hot enough to scorch right through their boots, and when they reached the hills the bare rock radiated heat like a furnace. Jed stopped, and stood gasping like a stranded fish. "I can't go any further," he groaned.

"Don't talk rot," said Bob sharply. "Suck a sweet and you'll be all right. Tib, where's the water?"

"It ain't far. Jest over the rynge."

"Her feet must be solid leather," said Tad enviously as he followed her. But Bob had to help Jed.

The range was only a couple of hundred feet high, yet Bob was precious thankful when they approached the top. Tib had got there first, but as she reached the summit she bent double and, dropping behind a large boulder, signed to the others to keep back.

Presently she came down to them.

"I can't see Blyne," she told them, "but you gotter keep right arter me. An' tell 'im"—pointing to Jed—"as 'e's got ter go keerful."

Bob and Tad crawled up behind the rock and peeped out. "My word, there's water all right," exclaimed Tad joyfully.

"Water! I should think there was," replied Bob. "A regular big creek. We're in luck, Tad."

Tad grunted. "Don't know so much about that. Some rum-looking customers over there." He pointed to a clearing in the thick brush that bordered the creek—a clearing in which stood about a dozen bark-built huts. They were just like native gunyahs, only larger and more solidly built. From the clearing a rough trail ran back to the foot of the hill. The path seemed to end in the rock, for it did not go up the hill. And down this path were walking five men, each carrying a heavy load on his back.

"Yes, they do look a bit queer," agreed Bob.

"Regular white savages. But what in sense are they carrying?"

"Stones, I believe," said Tad. "And I say, look at that boat! They're loading it."

Sure enough a large flat-bottomed boat lay alongside the creek bank. It was half full of rocks, which two men who looked like Malays were stowing.

Tad looked at Bob, and Bob saw he was frowning in puzzled fashion. "I wish I knew what we'd struck," he said slowly. "It's something almighty odd, Bob."

But Bob was looking at Tib, whose small face was twisted with rage. She shook her dirty little fist in the direction of the Malays, and under her breath muttered something about "yaller devils."

"WHO are those yellow chaps?" Bob asked her.

"Them's Blyne's chaps," she answered fiercely. "Miking slyves of our folk."

"Now we're getting it," said Bob aside to Tad. "Those chaps loading the boat are Malays. Blayne's their boss."

"That's about the size of it," agreed Tad. "But see here, Bob, I can't stick this sun much longer. Let's shin down the hill and get to the creek. Then we can hide up among the trees and plan what's best to do."

"Good egg!" agreed Bob. "But we'll have to be jolly careful not to be seen."

"That'll be all right," said Tad. "See that rift. If we go back we can crawl down the bottom of it without those chaps being the wiser."

Bob pointed out the rift to Tib, and she agreed that it would be the best way. So they went back a bit in a southerly direction to reach it, and started down. If it had been hot on the way up, the rift was a furnace. Exposed to the full blaze of the sun, the rock was hot enough to blister the skin. Jed collapsed, and the other two had to drag him along. It was like heaven to get into the shade of the trees, and when they reached the creek they all plunged straight into the water, clothes and all.

"Here's your chocolate, Tib," said Bob as he came out dripping. "We'd better all have a piece," he went on, plumping himself down in the shade. They sat and munched in silence for some minutes. Everything was very quiet, and the only sound was the harsh voices of the Malays, who were still busy with the boat about a quarter of a mile downstream. Jed had hardly finished his chocolate before he fell back and went sound asleep. He was quite done in.

"Tib," said Bob presently, "where does this fellow Blayne come from?"

"Ow do I know? 'E come up the billabong in 'is boat."

"Then the creek runs into some river, and most likely he came from the coast," said Tad shrewdly.

Bob tried again. "How long have you lived here, Tib?"

Tib's eyes widened. "I ain't never lived nowheres else."

"And Saul—how long has he been here?"

"I dunno. Always, I reckon."

"Does he ever go away?" Bob went on.

"'E goes 'unting. But none of us don't go far, 'cos o' the blackfellers. Sam, 'e went too far, an' they speared 'im."

"Nice sort of country," remarked Tad, with a slight shiver.

Bob went on questioning Tib, but he got very little out of her. The poor little thing was just a savage. She had never heard of reading or writing. She did not even know the name of the country she lived in. Yet she told Bob that she and her people had been quite happy until the coming of Blayne. With fish from the creek and game from the wood they had always had plenty to eat, and the blackfellers were afraid of them and dared not attack them unless they could catch one alone. She did not know how long it was since Blayne had first arrived, but Bob gathered it was about a year, and she was very vague as to why this man had enslaved her people. But oh, how she hated him! Her blue eyes fairly flashed when she spoke of him, and she begged Bob not to waste any time in killing him.

Bob stuck to his questioning. "Does Blayne stay here all the time?" he asked.

"No, 'e goes off with the boat. But 'e always comes back," she added, with a shudder. "And them yaller men—they're fair devils."

"Do they stay?"

"No, they goes, too."

"Then why don't your people go off?"

"Where 'ud they go?" Tib asked.

"Down the billabong," suggested Bob.

"We ain't got no boat," Tib answered.

"And they can't build one," said Tad to Bob. "Looks to me as if they were pretty well fixed here."

Bob shrugged his shoulders. "That's about the size of it. But the rum thing is how they ever got here in the first place."

"It's a queer business anyway you look at it," said Tad. "What I want to know is where we come in. What are we going to do?"

"Lie low until Blayne's hooked it," said Bob. "Since he's loading his boat he'll probably be off pretty soon, then we can go and have a look-see."

"That sounds good to me," agreed Tad. "Meantime, what price a snooze? I'm dead sleepy."

"Carried," grinned Tad, as he stretched himself comfortably in the shade.

Bob was as weary as Tad, and had hardly closed his eyes before he was sound asleep.

Jed was the first of the three to wake. He was very stiff, sore and hungry. He dug Bob in the ribs, and Bob sat up. "What's the matter with you?" he asked rather crossly.

"Give me some chocolate," demanded Jed.

Bob paid no attention. He was looking all round. "Where's Tib?" he demanded sharply. He shook Tad. "Tad, Tib's gone."

Tad was up in a second, and looking about. "Here's her track," he said. "I say, Bob, she's gone back to the village."

"What—with Blayne about? Not likely!"

"Perhaps Blayne's gone," said Tad. "We've been asleep for hours."

Bob looked very uneasy. "We'll have to find out. Come on."

"You haven't given me any chocolate," whined Jed. "I'm hungry."

Bob flung him a stick. "Hide among the trees while you eat it," he ordered.

"You're not going to leave me?" cried Jed in a fright.

"Don't make such a row," Bob told him. "And stick where you are, or I'll know the reason why."

Jed scowled, but Bob's tone scared him, and he slunk away into the trees. The other two went on, Tad following the tracks of Tib's bare feet. "I say, Bob," Tad whispered. "I suppose that girl hasn't been playing a game with us?"

Bob shook his head. "She's square, Tad. I believe she's scouting to see if Blayne has gone."

Tad grunted. "I'm sure I hope you're right, and that we're not running slap into trouble."

They reached the edge of the clearing and dropped to the ground. "The boat's gone," Bob whispered.

"You're right," said Tad. "But where are Tib's people? I can't see a soul."

He was right, for there was not a sign of any living thing in or about the huts. The sun was low in the west, and the shadow of the range lay across the clearing. The place was deathly still, the only sign of life being a couple of crows sitting solemnly on a dead tree opposite.

Outside the huts were the ashes of cooking fires, but the ashes were cold and no smoke rose.

"Tad," said Bob, "I believe Blayne's collared the lot, and Tib, too."

"Then it's a healthy lookout for us," replied Tad. "Shall I go and have a squint, Bob?"

Bob hesitated. "Tell you what," he said. "Suppose we go up the trail to the hill first. They may be there."

"Try it, anyhow," agreed Tad. "But we'd best keep to the trees, and not show ourselves till we have to."

Bob nodded, and they stole away up through the thick timber alongside the trail. The trail was wide and well beaten, but as deserted as the rest, and when they reached the end all they could see was a good-sized hole in the rock.

"No one in there," said Bob. "Let's go and have a look."

The hole was about eight feet high and ran into the cliff face a matter of twelve or fourteen feet. The inner surface seemed to have been freshly cut, and a couple of rough pickaxes, a crowbar and two shovels were lying on the floor. But what caught the eyes of both boys was a broad yellow streak about eight inches wide, which ran slanting all across the newly cut rock face. Tad stared at it, then looked oddly at Bob. "Bob," he said in a hoarse whisper. "That's gold."

Bob laughed. "Gold! Don't be silly."

"Then what else is it?"

"Copper," said Bob.

Tad picked up the crowbar and drove the point against the yellow vein. It sunk in almost as though the stuff was cheese. He gouged out a piece as big as an egg and handed it to Bob. "Does brass weigh like that?" he asked.

Bob examined the lump of metal and his eyes widened. "I do believe you're right," he said at last. "But who ever heard of a vein like this? Why—why there must be millions here, Tad."

"A regular jeweller's shop," agreed Tad. "I say, Bob, this explains the whole business."

Bob nodded. "Blayne, you mean. Yes, of course. The beggar is using forced labour to get out the gold, and he and his Malays are taking it down to the coast. What a brute!" He paused and thought a moment. "Tad, we've got to stop this."

"If it's not too late already," said Tad grimly. "It looks to me as if Blayne had collared the lot this time, or else—"

"Look out!" yelled Bob, seizing Tad and shoving him violently aside. Just in time, for, with a vicious hum, something hurtled past them and struck the rock behind with such force that it broke and fell in pieces to the ground.

"A BOOMERANG," gasped Tad.

"Keep down," ordered Bob. "The next ain't likely to miss."

"But he hasn't another," said Tad. "There he is, Bob. My word, a regular white savage!"

Tad was right. The man who had thrown the boomerang was standing in the full blaze of sunshine some thirty paces outside the mine mouth, and he might have been a blackfellow, only that his skin was tawny and his hair straight and yellow instead of black and kinky. His clothes were even more scanty than Tib's, for all he wore was a pair of loose trousers made of sacking, coming a little below his knees. His skin was burned the colour of an old saddle, and though not a big man, his muscles were thick and corded. Half his face was covered with hair, from which his blue eyes looked out with an expression half scared, half savage.

"A rum-looking customer," agreed Bob. "Must be one of Tib's people."

"Question is what he takes us for," said Tad. "Hi, you!" he shouted. "No need to chuck boomerangs at us. We ain't doing any harm."

The man scowled. "'Oo are yer?" he demanded. "What yer doin' there?" As he spoke he lifted his left leg, and quick as a flash there was an ugly-looking spear in his right hand. It seemed like a conjuring trick, but both the boys knew the native dodge of carrying a spear between the toes.

"Tib'll tell you," said Tad quickly.

"Tib ain't 'ere," said the man sourly. "What yer done with 'er?"

As he spoke he raised his spear.

"Look out," said Bob sharply, but Tad stood up and stretched out his arms. "No need for that spear," he said coolly. "We have no arms. We found Tib out in the desert with blackfellows after her. We saved her and she brought us here."

"Thet's a lie," was the rough answer. "Wimmen ain't allowed 'ere."

He whistled, and next moment three more men like himself came running up the trail. All were armed with spears and boomerangs. "Come out Dr that," ordered the first man.

"Strikes me we're in the soup," said Bob. "What Are we going to do, Tad?"

"Just what he says. There's nothing else for it," replied Tad and stepped out. "Hold your hands up, Bob. It's our only chance." Bob followed. He did not feel happy, and small blame to him, for these four fellows were about as ugly a looking lot as he had ever seen. He wondered vaguely what would happen to the wretched Jed if he and Tad were scuppered.

Tad walked out bold as brass. "Here we are," he said. "What are you going to do with us?"

"Kill yer, I reckon," replied the man. "Ef we don't, Blyne will."

Tad grinned. "Why not kill Blayne instead?"

If Tad had dropped a bomb the men could hardly have been worse scared. They stood and gaped. Tad followed up his advantage. "I mean it," he said sharply. "See here, you chaps. Tib's told me how Blayne's been treating you. And now I've seen that"—pointing to the gold—"I know the reason why. Why do you stick it? You're white men, aren't you? Why do you let this fellow make slaves of you."

The blue-eyed man stared at Tad in a dazed way. "You're loony," he said thickly. "'E'd shoot us, like 'e shot Seth."

"Why do you let him shoot you?" demanded Tad. "Can't you make a fort of some sort?"

"Fort—wot's that?" demanded the man suspiciously. Before Tad could answer one of the others spoke up. "Tike 'em ter Bastable, Saul," he said. "Bastable'll know wot ter do with 'em."

"Right," said Tad cheerfully. "Let's go to Bastable."

He and Bob were marched off down the track to the village, and taken to the biggest hut, where a huge gaunt old man sat on a rough wooden stool. His thick hair and beard were white as snow, his face was a mass of wrinkles, but his eyes were still clear and blue under their shaggy brows. "My word, what a man he must have been when he was young!" was the thought that passed through Tad's head as he looked at the splendid old giant, then, walking straight up to him, put out his hand. Bastable stared a moment, then took the offered hand in his huge old fist. "'Ulloa, cully," he said genially, "where'd you spring from?"

"From a balloon, Mr. Bastable," replied Tad with a smile. "Bob here and I went up in a balloon and it broke loose and carried us right out over the desert. Then we saw Tib being chased by some niggers, so we came down, and scared 'em stiff. They hooked it, and Tib brought us along here."

"Wot's Dr berloon?" demanded Saul suspiciously.

"A gas-bag as floats in the air," explained Bastable. "I've seed 'em in my young days afore I come out to this 'ere dratted never-never land."

"Floats in the air?" repeated Saul, scowling.

"Yus," said Bastable, "but 'ow'd you know anything about it, you pore ignorant beggar?"

"'E's tellin' yer lies, granfer," growled Saul. "We found 'em in the gold 'ole. An' Tib, she ain't 'ere."

"Oh, ain't she?" retorted the old chap briskly. "She was 'ere jest a minute afore you come in, an' told me about these 'ere lads. Saved 'er life, they did, jest as this one sez."

Saul looked rather blank. "Then wot was they doin' in the gold 'ole?" he demanded. "An' see here, granfer, this one, 'e sez we'd orter kill Blyne."

"Aye, an' 'e's right, too. Yer'd hev done it long ago if yer'd been men."

Saul flushed angrily. "An' be killed like Seth was," he snarled.

Tad cut in. "Who is this Blayne, Mr. Bastable?"

"'E's a dirty dog," said the old man fiercely. "I dunno 'ow 'e got 'ere, but 'e come up the billabong in a boat about a year agone. First off 'e pretended to be friendly like, but that were all a plant, and next thing we knowed 'e'd got these 'ere Malays round us with their guns. My grandson, Seth 'e wasn't takin' it lying down, and 'e put it acrost one o' them Malays. Blyne shot 'im dead." The old man's blue eyes flashed, and his great fists clenched. "Arter that wot could we do? We 'adn't no guns. 'E took all the gold we 'ad, our cookin'-pots an' everything, an' 'e told us 'e'd be back for more in three months, and if we didn't 'ave enough 'e'd shoot another of us. Since then we been nothing but dirty slyves. S'welp me, I'd as soon be back on the chain gang as live like this."

"He was here to-day," said Tad quickly.

"'E's been 'ere three days. 'E thrashed Tib acos she checked 'im. That's wot she run for."

"The brute!" snapped Tad. "I say, can't we do anything?"

"'Ave you got any guns along?"

"No such luck," said Tad sadly.

"Then it ain't a bit o' use," said old Bastable with decision. "The best thing as you kin do is ter get into that there berloon o' yours an' skip out sharp."

Tad laughed. "The balloon's bust, but even if she wasn't you wouldn't catch us clearing out, Mr. Bastable. We're here to help you if we can, and I'm willing to bet that if we put our heads together we can bust up this Blayne person."

A smile deepened the million wrinkles on old Bastable's brown face. "Thet's the way ter talk, son. I likes to hear yer. We'll 'ave a proper pow-wow arter supper. Set ye down. Grub'll be ready soon."

Bob nudged Tad. "I say, have you forgotten Jed?" he said. "The beggar will be scared stiff."

Tad nodded. "We'll fetch him and those things from the balloon. They'll come in handy as presents for these folk. Wait till I tell Bastable, then we'll be off."

TIB was waiting outside. "'Ave yer seed Bastable?" she asked eagerly.

"Yes, but you let us in nicely, Tib. Saul wanted to finish us when he found us in your gold hole."

Tib's nose curled scornfully. It was plain she had little respect for her father. "'Im, 'e's skeered o' Blyne. But I were watchin', I wouldn't ha' let 'em hurt you."

"H'm, you didn't stop him chucking a boomerang at us," returned Tad. "But it's all right now. Mr. Bastable has asked us to supper, and we're off to fetch Jed."

"You'd best leave 'im where he be," advised Tib. "'E ain't no good. 'E ain't worth the grub 'e eats."

Tad laughed. "Come on, you bloodthirsty little beggar. We're going to try and reform him."

Tib shook her rough head. "I dunno wot that means," she answered crossly. "I wisht you'd talk plain."

"We'll try," said Tad good-humouredly. "Come along."

But when they reached the place where they had left Jed, Jed was not to be seen.

"What the mischief has become of him?" growled Tad.

"Croc's got 'im, I reckon," suggested Tib. "They gets 'ungry evenings."

"Nonsense!" said Tad sharply. "Jed! Jed! Where are you?"

"Here," came a thin voice from somewhere overhead, and, looking up, there was Jed clinging to a branch twenty feet from the ground. He had lost his hat, his face was scratched and he looked even worse scared than usual.

"What in sense are you doing up there?" demanded Tad.

"You'd better come up quick," said Jed in a terrified voice. "There's an awful beast under that rock. It's an alligator, I think."

"An alligator under a rock! You're crazy," retorted Tad.

"I'm not. It came right at me. It was as long as me or longer, and had the most awful teeth."

"Which rock?" asked Tad, and Jed pointed to a big boulder among the trees. Tad went over to explore. "There's nothing here," he said. "Come down, Jed."

Taking courage from numbers, Jed climbed slowly down. Just as he reached the ground Tib, who had been nosing round the rock like a hunting dog, uttered a shrill scream. "A 'guana!" she cried, and, flinging herself flat, thrust her arms into a hole. "I got 'is tail. Come an' 'elp!"

Tad chucked himself alongside her and reached down. "She's right, Bob," he exclaimed. "It's a whacking big 'guana."

"What's a 'guana?" asked Jed shakily.

"A lizard," Bob explained. "Iguana. Jolly good to eat. Don't be scared. It can't hurt you."

Tad and Tib were pulling like demons, but the beast had dug its claws in and they could not shift it. Bob took a hand, and the three hauled for all they were worth. Jed, still scared, kept well behind and watched.

The combined weight of the three proved too much for Master Iguana, and all of a sudden he let go. Tib, Tad and Bob fell backwards and rolled over one another, and the guana went flying through the air, and hit Jed full in the chest, knocking him flat on his back. Jed and the guana rolled together, Jed yelling as if he were being murdered.

The guana got its legs first and bolted, but Tib was after it like a terrier, and, snatching up a dead branch, caught it a whack across the back that broke its spine and killed it at once.

"Good for you, Tib!" cried Tad. "Now we have got something for supper."

Jed picked himself up, and gazed disgustedly at the huge lizard, with its great head and frilled crest. "You don't mean to say you'd eat that?" he asked in a horrified tone.

Tad laughed as he shouldered the body. "I'll bet you'll be jolly glad of anything half so good before we get home again."

"When are we going to start back?" Jed wanted to know.

"We've a job to do here first," Tad told him briefly. "Come on, if you want some supper."

The cooking fires were re-lighted when the four got back to the village, and the people seemed almost cheerful. Tib explained that the reason why no one had been about when the boys first visited the place was that everyone was so tired with loading Blayne's gold that they had been asleep. Blayne had forced them to work nearly all night carrying ore from the mine to the boat.

"We're in luck," said Tad to Bob. "I mean arriving when we did. Now we've got three months to organise this crowd."

Bob looked doubtful. "Think we can do anything with them?" he asked. "Though their skins are white they're not much better than blackfellows."

"Old Bastable's all right," said Tad. "Don't you worry. We'll settle Blayne's hash."

Old Bastable's blue eyes shone when he saw the iguana. "Proper good vittles," he said, smacking his lips. "'Ang 'im up to a tree, an' then we'll 'ave supper."

Supper was fish from the creek broiled over wood embers and roast wallaby. "We ain't got no bread or cawfee or sugar," Bastable explained. "We 'as to live like blackfellers."

"Don't worry about that," Tad told him. "We've had nothing but a bit of chocolate since yesterday. I'm hungry enough to chew coke. And here are some plates and knives and forks."

Bastable took one of the neat white enamelled plates in his hands and stared at it. "First time as I've seen a plate in fifty years an' more," he said slowly.

"You mean you've been here that long?" exclaimed Tad.

"Aye, lad. Wot year is it now?"

"1925," said Tad.

"An' we come 'ere in 1872. Fifty-three year. It's a long—long time."

He put some fish on the plate and began to eat it with a knife and fork. He was curiously clumsy, yet seemed to enjoy the use of the long-forgotten implements. Hungry as he was, Tad stopped eating to watch him.

Presently the old man went on again: "There was four on us, Joe Goggin an' 'is wife, an' me an' my gal. The gold-fields police was arter us, an' we was drove right out inter the scrub. We didn't dast turn back, but kept on west, driftin' from one water-'ole to another, livin' on wot we could trap or snare. It were a wet year, the wettest ever I remembers. If it 'adn't been we'd 'ave died o' thirst. But the water-'oles was full an' the desert thick with grass an' flowers."

He paused again, and the boys sat waiting breathlessly, until he went on: "At last we struck this 'ere billabong. Goggin's wife were ill, and the rest of us weren't no great shakes, so we reckoned to camp fer a week or two. But it were three months afore Goggin's wife were fit ter walk, an' then it were too late. The water-'oles was dried up, the grass were dead. Goggin sez ter me, 'I've seed worse places, Ned. We might as well stop 'ere.' So 'ere we've been ever since. Joe's dead, 'is wife's dead an' my wife's gone too. I'm the only one as is left."

He looked so old and desolate that Bob felt desperately sorry for him. "But you're not alone, Mr. Bastable," he said gently. "You've got your children and grandchildren."

"Aye, but wot's the use? They're jest savages. No eddication or anything. An' now, as I told ye, they ain't no better'n slaves to that there Blyne."

"That's what we've got to talk about," said Tad promptly. "We are going to do down Master Blayne."

"I wish I knowed 'ow," said Bastable. "It's this 'ere cussed gold. Joe, 'e found it, an' mighty useful it were, fer we 'adn't no metal, and Joe 'e made cookin'-pots an' things outer it."

"Cooking-pots out of gold!" gasped Jed, speaking for the first time.

"It were all it were any use fer," growled Bastable. "We couldn't buy nothing with it."

"Blayne's buying things with it," cut in Tad. "And he'll keep on coming for it as long as there's any left. We've got to stop him."

"'Ow are ye going ter stop 'un?" demanded Bastable. "We ain't got no guns, so we can't fight 'im and 'is dirty Malays. We can't clear out, fer there ain't nowheres to go. What yer going to do about it?"

"Can't we make a fort on the hill and keep him off?" suggested Bob.

"We kin make a fort fast enough, but 'e ain't going to be fool enough to attack it. All Blyne's got ter do is set down an' wait till our water's gone."

"What about laying for him down the creek and chucking rocks into his boat and sinking it?" suggested Tad.

Bastable laughed harshly. "Don't kid yourselves. Blyne's wise ter any game o' that sort. 'E comes in the day-time and 'e keeps a mighty good look out."

Bob spoke again. "What about building boats and clearing out down the creek? Surely we could dodge him that way."

"I've thought Dr that," allowed Bastable. "Trouble is we ain't got no axe nor saws nor tools ter build boats. An' if we 'ad, there ain't no one 'ere 'cept me as could use 'em. And you'd need a lot 'er boats to move the 'ole lot. There's eighteen on us besides you three." He paused. "You got any more notions?"

"Yes," said Tad. "Build a boom across the creek and stop Blayne's boat from getting up."

"A boom—wot's that?" demanded Bastable.

Tad explained that it was a number of logs fastened together and slung across the creek under water so that any boat coming up would stick on it.

Bastable shook his head. "Wouldn't be no use," he said. "Them fellers 'ud get her off, an' then it 'ud only be the worse fer us. Likely they'd shoot one Dr two of us men, an' flog the women."

Tad refused to be discouraged. "If we put spikes on the boom it would knock holes in the boat and sink her. Then if we were ready for them with boomerangs and clubs they wouldn't stand a show because all their guns would be under water."

Bastable leaned forward, and his blue eyes shone. "By gum, there might be something in that, son. I reckon it 'ud be worth trying."

"Let's try it," said Tad quickly. "We've got three months to work it."

"Aye, there or thereabouts," said old Bastable.

Someone rushed frantically into the hut. It was Tib, and her face was white under its tan and her eyes were big with fright. "Blyne's come back," she cried. "Young Joe, 'e seed 'im coming up the billabong. 'Im an' Lamok and three on 'is men."

THE shock of Tib's news was so great that for a moment no one spoke. They simply stared at her. Tad was the first to recover his wits. "Blayne coming back!" he said sharply. "What for?"

"Mebbe 'e's forgot something," suggested old Bastable. "Or one o' them Malays of 'is may 'ave bin spying round an' got wind o' you boys."

"That's not likely," said Bob. "He—"

Tib broke in. "Didn't I tell yer Blyne was coming? 'E'll be 'ere an' cop the lot o' ye ef ye don't do something better'n jest talking."

"She's right," said old Bastable quickly. "Likely Blyne don't know as you're 'ere, and there ain't no sense letting 'im know. Tib, you tyke 'em up the creek and 'ide 'em somewheres in the bush an' wyte until I sends word as all's clear."

"That's talkin', granfer," said Tib. "I'll 'ide 'em. Come on, you."

She led the way, and the three boys followed her out of the hut. Tib could move like a shadow; Tad and Bob were almost as light on their feet as she, but Jed was clumsy as a cow. It was lucky for them all that it was dark, for otherwise Blayne and his men must have seen the fugitives before they reached the trees. Bob got hold of Jed by one arm, Tad took the other, and they fairly dragged him through the thick bush. He stumbled over roots, and panted like a pig, but somehow they hauled him on until the dark trees dosed round them and they felt it safe to slacken their pace a little.

"Where are we going?" demanded Jed crossly.

"How the mischief do I know?" responded Tad. "Ask Tib. She knows."

Jed did not ask Tib. He was scared of this wild, brown creature with her sharp tongue, and realised that she had very little use for him.

Tib kept on. She seemed to have eyes like a cat, and did not stop until she came to a huge fallen tree. "There's a 'ole underneath," she explained. "Big enough fer all on us if anyone comes. But there ain't no need to git inter it yet." She sat herself down with her back against the log, and the others followed her example.

"I wonder why Blayne came back," said Tad thoughtfully. "I can't believe he knew anything of our arrival."

"'E didn't know nothing about yer," Tib answered. "I'd 'ave knowed if any o' 'is Malays 'ad been 'anging round. It were wot granfer said. 'E'd left something be'ind."

"Then when he's got it he'll clear out and go on down the creek," Bob said.

"I 'opes so, anyways," said Tib. "Any'ow, I'll go ter see as soon as it's light."

"Who's this Lamok you spoke of, Tib?" asked Bob.

"'E's the boss Malay," Tib told him. "'E's worser than Blyne 'isself." She shivered, and Tad patted her on the shoulder. "Don't you worry, Tib," he said. "We'll fix the swine if he comes after us."

"You can't do nothing," Tib told him gloomily. "You ain't got no gun. 'E'd shoot yer soon as look at yer."

Jed put in his oar. "But Blayne is a white man, isn't he?"

"White outside," remarked Tib bitterly. "Inside 'e's blacker 'n a blackfeller."

"Is he English?" asked Jed.

"'Ow do I know? You better arsk 'im," said Tib.

Jed turned to Bob. "Look here, Warburton," he said in a lower voice. "How would it be to go to this man, Blayne, tell him who we are and how we got here, and ask him to take us home? My father would pay him anything he asked."

Bob laughed. "Why, you ass, what do you think money means to a fellow like that when he's digging thousands out of that gold hole? He'd simply collar you and stick you in with the rest of the gang to dig gold for him."

"I don't believe he'd do anything of the sort," insisted Jed. "After all, we're a bit different from these people here."

"Speak for yourself, Coppin," said Tad scornfully. "And anyhow, I never heard a sillier suggestion than yours. Bob's perfectly right, for if Blayne got hold of you he'd make a slave of you with the rest. Our one chance is to lie doggo until Blayne shifts, then we'll have time to look round and fix up some plan for scuppering the blighter."

Jed turned sulky, and shut up. The others talked a little, then fell silent. There was no sound from the camp, and the night was very still. Now and then the queer croaking cry of some night bird came from the distance, now and then there was a rustle up above as a possum moved on its nightly search for food. Occasionally there was a splash from the creek as a fish rose, but for the rest all was quiet.

"Seems all right," said Tad at last. "No one after us, is there, Tib?"

"Not as I knows of," Tib answered.

"Then what about forty winks?" asked Tad.

"I ain't never 'eard of 'im," said Tib, puzzled.

"His other name is Morpheus," laughed Tad. "What I mean, Tib, is whether it's safe to go to sleep."

"Why don't yer say what yer mean?" returned Tib, rather crossly. "Yes, yer can sleep if yer wants to."

"I don't know whether I want to," said Tad, "but it's about the best way of putting in the time." He leaned back against the big log and made himself as comfortable as he could. Bob followed his example, and in a very few minutes the pair were sound asleep. Jed fidgeted a while, then seemed to make up his mind that he might as well do the same, and he, too, became quiet. Tib waited with the quiet patience of a wild creature until Jed began to breathe deeply, then she curled herself up on the warm dry ground and was asleep in a matter of seconds.

Tad was wakened by a small, hard hand which clutched his arm and shook him. "Wike up!" came Tib's voice in his ear. "Wike up, Tad."

"What's the matter?" asked Tad drowsily.

"I'll tell yer wot's the matter," said Tib fiercely. "That there Jed, 'e've gone."

Tad was wide awake in a flash and sat up straight. "Jed gone! By gum, so he is. Bob—Bob, I say, Jed's gone."

Bob roused as quickly as Tad. "Where's he gone?" he demanded.

"I'll lay 'e've gone to Blyne," said Tib, with extraordinary bitterness.

"Nonsense!" exclaimed Bob. "He couldn't have been such a fool."

"'E's worse 'n a fool," Tib declared. "'E said 'e'd pye Blyne ter tike 'im 'ome, and now 'e's gone ter find 'im."

"Then you heard?" said Tad sharply as he sprang to his feet.

"In course I 'eard. I ain't deaf."

"But he'd never find his way," objected Bob.

"I dunno so much about that," said Tib. "'E's only got ter get ter the creek, an' foller down the bank."

"That's true," said Bob. "Come on, Tad, we've got to stop him at any price."

It was all very well to talk of stopping him, but none of them knew how long it was since Jed had left. It was still pitch dark, and no sign of dawn, and they could not even see to follow the tracks.

Tib spoke up. "It ain't no use ter foller 'im. Best thing we can do is ter 'ide ourselves where Blyne can't find us."

"We can't let him go tumbling into Blayne's hands!" said Bob sharply. "You don't know what that brute might do to him."

"'E's only got 'isself ter thank," argued Tib. "If we does go arter 'im, we can't do nothing ter 'elp 'im."

"We've got to try, anyhow," said Bob doggedly. "Come on, Tad."

To his surprise Tad did not move. Bob caught him by the arm. "What's the matter with you, Tad? Aren't you coming?" he asked sharply. "We must rescue the chap."

"How are you going to do it?" Tad asked.

"I don't know."

"No more do I," said Tad. "And I ask you what chance have we got against half a dozen men all armed? We should only be caught like him or shot down."

"You're not funking it, Tad!" said Bob in a scandalised voice.

"Don't be silly," said Tad shortly. "There's no question of funking. How will it help Jed for us to run our heads into the same mess that he's in?"

Bob hesitated. "But we must do something," he argued.

"Of course we must do something, but Tib's jolly well right when she says it's no use to follow Jed. See here, Bob, you've got to remember that old Bastable is depending on us to get him out of this mess, and if we are collared by Blayne we shan't be able to help him or anyone else."

"Yes," said Bob slowly, "you're right about that. All the same it goes against the grain to leave Jed in the hands of these brutes. Why, they may murder him."

"Not likely. They'll be much too keen on getting another pair of hands to dig their gold."

"I daresay you're right," said Bob; "but here's another thing you've got to remember. Blayne's no fool, and of course he'll question Jed as to how he got here."

"And Jed'll give us away," added Tad quickly. "Yes, that's a certainty, so the first thing we have to do is to shift out of here. Where can we hide, Tib?"

"There's caves up in the Range," Tib told him, "but wot's the good? We ain't got no grub, and Blyne'll tike care we don't get no water either."

"Can't we go right up the creek?" suggested Bob.

"'E'll come arter us," said Tib gloomily. "'E's a terror, Blyne is, an' them Malays kin foller a track like blackfellers."

"We're in a pretty mess," growled Bob. "Seems to me our only chance is to slip back to the village, collar some spears or waddies and try to finish Blayne."