RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"Strong-Hand Saxon," C. Arthur Pearson Ltd., London, 1910

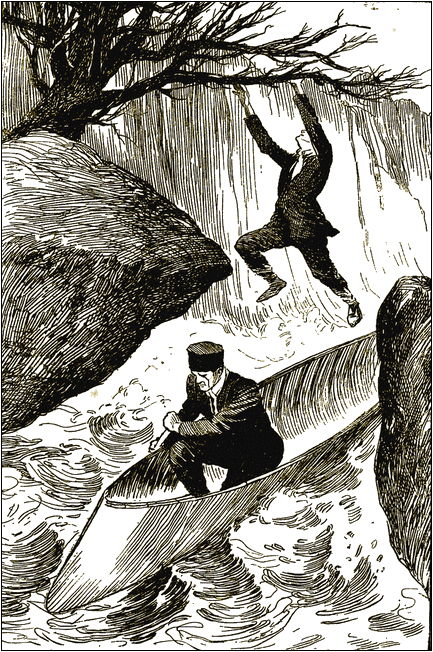

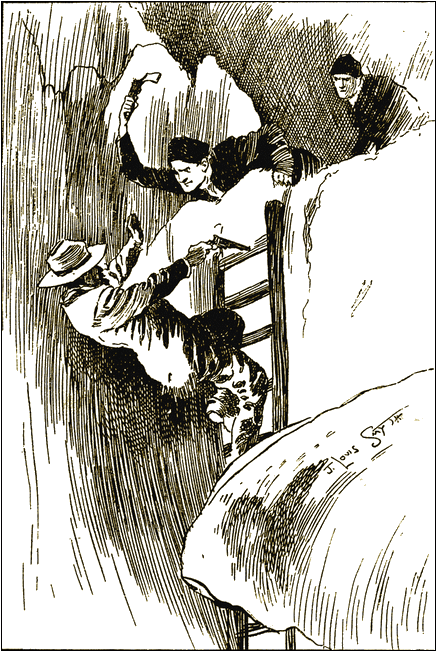

Frontispiece

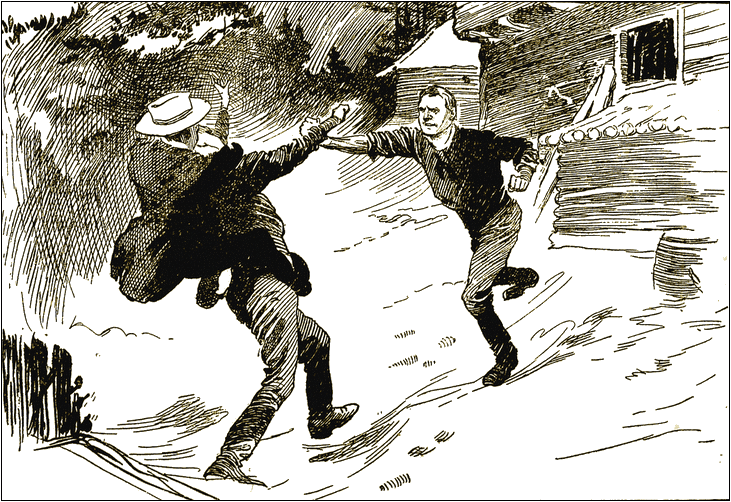

"Jump!" roared Saxon, and Tom made a mad leap upwards.

"BUCK up, Dandy," said Tom Holt, smacking the old plough-horse on his quarter, "we've done a hard day's work, but you'll get the best dinner o' the three. Sweet corn an' good chaff for you, but nothin' but potatoes and salt for me and dad."

Tom broke into a cheery whistle as the farmstead was neared, and the plough-horse stepped out more briskly at the sight of his stable. The boy was sitting sideways on Dandy's broad back, and the chain traces and roller-bar were trailing behind the horse.

"Taters and salt!" repeated Tom, with a chuckle. "I read somewhere in a newspaper that the British farmer lived on the fat of the land and did no more work than he could help. I wish the chap who wrote that'd take Berrymead Farm an' try it."

Tom whistled again. Things were never so black but that he could whistle, and they were often black enough at Berrymead, in all conscience.

The boy knew too well what a struggle it was for his father to keep the farm going. The land was poor, and they had had three bad seasons running. Unable even to pay for labour, Farmer Holt and his seventeen-year-old son did nearly all the work themselves, and bitter toil it was at times.

They would not have had their neighbours know it, but the very beasts in the byre and stables lived better than Holt and his son. Without good corn and fodder the horses could not work, but potatoes, home-made bread, and an occasional rabbit snared in the spinney were all the farmer could allow himself. And even rabbits were scarce at Berrymead.

As for ready money, Holt had had to thresh out new wheat and sell one of his carts to pay the last half-year's rent, a month overdue. It was lucky for John Holt that he had a son whom no work could tire, and who kept up the strength and cheerfulness of a young Hercules, even on potatoes and salt.

"Hullo!" said Tom, as the ramshackle old farmhouse and cattle- yard were neared. "Strangers!"

A high dog-cart stood at the front gate, the horse unattended and hitched rather carelessly to the palings by the reins. Tom recognised the cart—it was one that a jobmaster in the nearest market town let out for hire. But few visitors ever came to Berrymead, and Tom wondered who they could be.

"Not bailiffs, I hope," said the boy to himself. "Poor old dad, he's got trouble enough without that!"

As Dandy's hoofs crunched on the gravel, Farmer Holt himself appeared at the door of the house. He was a strongly built man of fifty, with a simple face, much lined with worry, and kindly grey eyes. He seemed strangely excited—a very rare thing with him.

"Hitch up the old hoss and come in quick, Tom," he said. "I want you."

John Holt dived into the house again, and Tom, wondering what was in the wind, stabled Dandy and went indoors.

In the little parlour stood his father, looking strangely bewildered, and two other men. It was to these that Tom directed his gaze.

One was a lean, sharp-faced man, neatly dressed, with long white hands and a professional look. He had a keen, penetrating glance.

The other man was rougher. He was six feet high, loosely built, and a long black coat hung on him awkwardly. His narrow face was disfigured by a scar reaching from the left eye to the corner of the mouth, which gave him a strangely sinister appearance.

Both men stared at Tom as he entered the room. To the boy it seemed that his appearance was a surprise to them. "This is my son Tom," said John Holt. "Tom, this is Mr. Edward Fulton," pointing to the lawyer-like man; "and he's Mr. Lomax," indicating the other. "They've come all the way from Ameriky to see me and tell me—"

Fulton broke in. His voice had a strong American twang. "Mr. Holt," he said suavely, "this is a private matter of business between us and yourself. Do you think there is need to tell your son anything about it?"

There was a slight sneer in the man's voice, which Tom instinctively resented. But his father replied at once. "I've no secrets from Tom. He looks like a boy, but he's past seventeen, and my partner, as you may say." Tom saw the strangers exchange glances, but his father went on: "Tom, poor Jim's dead—my brother. You remember I told you he went to Canada nigh twenty years ago. It seems he had some land there, and he's left me his heir. These gentlemen have come about it. They want to buy it."

"How much land is there?" asked Tom.

"Something like thirty thousand acres. Seems a terrible lot, don't it? Nigh three times as much as Squire Brand owns."

"But you can't compare it with English land," broke in Fulton hastily. "It's quite wild and undeveloped, and more than five hundred miles from the nearest railway. Anyone would give a thousand acres there for one in England."

"What are they offering, dad?"

"Three hundred pounds."

"I know it doesn't seem much," broke in Fulton; "but I think it's all it's worth. As I tell you, it's beyond the edge of civilisation, a lonely spot, quite undeveloped, and no one could do anything with it without capital. There's no house except a little log shanty, no cultivated ground, no tools or stock, no market near. The winter's long and hard and the summer short and hot."

"Then why do you want it?" inquired Tom bluntly, staring straight in the lawyer's sharp face.

The man smiled. "I don't. It's a client of mine—Mr. Glynne, of Winnipeg, a rich man. There's some timber on the place. That's what he's after; but it'll be probably years before he touches it. It will take a lot of capital to do anything with it."

"It don't seem enough to me," said Tom's father.

"Nor to me, dad," echoed the boy.

The lawyer shrugged his shoulders. "I'd be glad if you'd make up your mind. I may tell you one thing. The taxes are not paid, and in something like a month the place will revert to Government. Maybe it's no business of mine to offer you advice, and it doesn't matter to me one way or the other; but if I did make a suggestion I should urge your accepting Mr. Glynne's offer. This place looks as if it wanted a little money spent on it." His eyes dwelt on the threadbare carpet and shabby furniture. "You could do a deal here with three hundred." He pulled a bundle of papers from his inner pocket, unfolded them, and began spreading them on the table.

Tom spoke up. "I wouldn't take it, dad. What's the good of our wasting money here on land that isn't ours, and with a landlord that won't even mend our roofs for us? I'm sick of this slaving. Let's go to Canada and try our luck. The work can't be harder, and we'll be on our own land, and whatever improvements we make will be ours. Let's try it."

The old man stood by the fireplace, looking from one to another, plainly undecided. The scar-faced man sidled up to him and whispered in his ear: "Ask five hundred. I reckon he might run to that."

The words had a totally different effect upon the farmer from what the other had evidently intended. "No," he said, with sudden decision. "I agree with my boy here. Mr. Fulton, I won't sell that land. I'll go out and live on it."

Again Tom noticed the two strangers exchange glances. "You mean that definitely, Mr. Holt?" said Fulton.

"I do. We'll be in the workhouse if we stay here at Berrymead another year or two. I'm not too old to try my luck in a new country. We'll sell up our sticks here and raise money enough for our passage, and go to this place my brother's left me. Sunk River you called it, didn't you?"

"Yes, Sunk River. Very good, Mr. Holt. But your passage is my affair. Your brother left the whole matter in my hands." He pulled out a pocket-book, selected a note from it, and handed it to the farmer, who took it wonderingly. "That's for immediate expenses," he said. "Our own passages are booked by the _Arabia_, which sails from Liverpool to-morrow morning. You'll come with us, for as it is it will be hard travelling to get to Sunk River in time to settle those taxes." He looked at his watch. "We've just an hour to catch the train at Granton. Put what you want for the journey in a bag, Mr. Holt, and we'll start at once."

"What about Tom?" inquired his father.

"You'd better leave your son here to look after the farm, and if necessary hold the sale. He can follow you as soon as you are settled."

The man's brisk manner had its effect. John Holt turned and left the room. Tom hesitated a moment, then followed. He found his father in his room hurriedly changing into his well-worn Sunday suit.

"Put them shirts in my bag, Tom," said his father, "We'll have to hurry to catch that train."

"Dad, I wouldn't go alone with those fellows if I were you. You don't know anything about them, and I tell you straight I don't like their looks."

"What—not go, and lose all that land!"

"How do you know what they say is true?"

"Mr. Fulton showed me Jim's will."

"A forgery for all you know, and, if not, why was he so precious anxious to buy the land?"

"But he gave me this money—ten pounds it is. He wouldn't do that if he meant anything wrong. You've got a maggot in your head, Tom. Don't waste time, lad; put them things in. We haven't too much time to get that train."

The old man's jaw was set in the stubborn fashion which Tom knew well. The boy said no more, but all the time that he was rapidly packing the bag he was thinking hard. By the time it was done he had a plan formed in his head, and, lifting the bag, he carried it downstairs and out to the trap, and then, making a round of the house, came in by the back door.

Tom Holt was no fool. He was much older than most youngsters of his years. His mother had died when he was only thirteen, and since then he had sturdily helped his father in every detail of the work and management of the farm. For some time past he had seen quite clearly that Berrymead Farm could not be made to pay. He had told his father so, but the old man, who had spent all his life on the place, had never taken the same view. He had always gone on hoping for better times. So Tom, well aware that the smash must come, had been making his own preparations, and for nearly three years had been hoarding every penny he could lay hands on. He sold rabbit-skins, he spent an odd day mole-catching or loading for shooting parties in Squire Brand's coverts. He denied himself everything. The consequence was that down in the old cider cellar, hidden behind a loose brick in the far wall, was a wash-leather bag holding nearly nine pounds.

"Not much," said Tom to himself as he stole cautiously through the kitchen to the door at the top of the cellar steps, "but enough to pay my passage, I reckon. Dad'll be awful cross when he finds out, but I'm shot if I let him go alone with that pair of beauties. I don't know what they're up to, but there's something fishy about it, I'll swear. It won't take me more than fifteen minutes to run over to Honeywood across the fields. Dick Grainger will lend me his bike, and, as it's all downhill, I ought to manage to catch that train."

He reached the cellar door, which opened out of one end of the kitchen. It creaked a little, but he slipped through, closed it behind him, and made his way cautiously down the worn steps. There was another door at the bottom, and when he opened this he found himself in an underground place floored with clay—damp, dim, and chilly. There was nothing in it but a few mouldy rotten hogsheads. No cider had been made at Berrymead for many years.

As Tom closed the upper cellar door behind him, the door of the parlour, which also led into the kitchen, was pushed gently open, and Fulton came out on tiptoe. "What's he after?" he whispered to Lomax, whose tall figure towered behind him.

"Gone to get a drink, I reckon," answered Lomax. "I wish I had a drop of rye."

"Drink, not likely! Ben, I don't trust that youngster. He smells a rat."

"What kin he do—a kid like that?" demanded Lomax.

"Trip us up if we're not mighty careful. I'm going to see what he's up to. Follow me. Quick, before the old man comes down."

The only light in the cellar leaked through the rusty bars of a heavy iron grating. Tom had to strike a match to find his hoard. The small flame showed him plainly to the two men who had followed down the steps—showed, too, the hole in the wall and the bag of coin which he took from it.

"Young fox!" hissed Fulton. "So that's his little game. He means to follow us. Ben, you've got to stop him. I must hurry back. I hear the old man coming down—"

Tom, on his knees beside the wall, was holding his precious hoard, when a shadow stooped over him. Before he could turn or cry something heavy and hard thudded on his head, and with one sob he fell forward and lay quiet.

Lomax waited one moment, listening intently; then, unscrewing the stick with which he had struck down the boy, he slipped the two sections into a pocket and tiptoed quietly away across the damp clay floor.

IT was about four in the afternoon when Tom had gone to the cellar. The light which leaked through the grating was dim when he struggled slowly back to consciousness. His head felt like lead. He put his hand up, and found his hair was clotted with dried blood.

"What's happened?" muttered the boy, sitting up dazedly. At first he could not remember anything. Then suddenly recollection flashed back, and he sprang up, only to topple over again dizzily. But he was dead game, was Tom. In another minute he was up again and staggering towards the door.

It was locked from the other side.

"The blackguards! They did it. And they've carried off dad." Utterly overcome, Tom sank down on an old cask. He was half mad with rage and grief. Here he was, trapped and helpless, while the scoundrels were carrying off his father, Heaven knew where. In the agony of the thought his own plight was forgotten.

But slowly it grew on him. He was in considerable danger of his life. The cellar was below ground. There was no other way out but the door or the grating, and the door was locked, while the grating, also heavily padlocked and rusted into its stone sockets, was out of reach. Knowing every inch of the place from babyhood, Tom was certain there was no escape. It might be days—even weeks—before anyone came to the house. Even if anyone did come, it was a hundred to one they would not hear him. The disused grating was at the east end of the house, opening into a grass-grown yard. It was extremely unlikely that any casual visitor would go round that way.

"Plenty of time for me to starve," muttered Tom bitterly. "Poor old dad! Think of his being in the hands of brutes who could do a thing like that!"

Tom was not the sort to sit still, and as soon as his head stopped buzzing a little he got out his matchbox, and, cutting some splinters off one of the broken barrels, made a tiny fire, and by its light set to work to try to get out. The door, he knew, was hopeless—an old-fashioned affair of heavy oak, which nothing short of an axe would batter down. He made a pile of the least rotten of the old barrels and painfully climbed up to the grating. It was very nearly dark outside. The tiny patch of visible sky was already set with frosty stars.

Twice the barrels broke down; the third time Tom succeeded in reaching the grating. He shook it, but could not stir it. He forced his hand through and tried the padlock. Rust-coated as it was, the thick metal was still sound.

"I'll put a signal up, anyhow," said Tom, and, pulling off his necktie, he tied it to a barrel-stave and thrust it through the bars.

There was nothing more to be done. He dropped back, and, crouching beside his little fire, set himself to wait for daylight. It grew very cold. It was only March, and the night outside was frosty. Tom dared not use much of his wood, and his teeth chattered; also his head ached abominably. But he hardly thought of these things. It was the idea of his father in the hands of these unscrupulous blackguards that nearly drove him mad.

He dimly heard the old grandfather clock in the kitchen striking seven, and the familiar sound somehow gave him a little comfort. Next minute he started sharply, then sprang up, listening intently. A dim rap-rapping came to his ears. It was someone at the back door. He shouted with all his might.

A pause. Again the tapping.

"They haven't heard!" groaned Tom in despair. Once more he shouted furiously, but he felt it was no use. The enormously thick walls smothered his voice and made him certain that he could not be heard. He seized a barrel-stave and pounded on the door.

The knocking came a third time, then stopped. Tom shouted till his voice failed him, then waited in agonising suspense. All was silent. In the frosty air outside the grating not so much as a leaf stirred. He pressed his ear against the wall, but could hear nothing. Flinging himself down on his face on the floor, for the first time he gave way to utter despair.

"Hulloa! Hulloa! Anyone there?" The voice came down through the grating. Almost believing that he was dreaming, Tom sprang up once more and gave a piercing yell.

"All right, partner. Don't you worry. How in thunder do ye get into this shebang?"

Bewildered and hardly understanding, Tom said: "What?"

"Where's the way in? If you're any thicker than this stick of mine you didn't get down this way. Which is the other way?"

Tom had his wits about him again. "If the back door's locked, break the window next on the left. That lets you into the sitting-room. Through that, and you're in the kitchen. The door opposite leads to the cellar, where I am."

"Right oh! Sit tight. I'll be along in a brace of shakes."

Tom couldn't sit. He stood by the door, positively shivering with excitement. The last three hours had played the mischief with his nerves.

But his new friend did not fail him. Tom faintly heard a tinkle of glass, then a firm step in the kitchen above, and the upper door of the cellar was tried.

"The key's gone, partner. Wait a jiffy. I'll bust it." Another pause, then a crashing blow—another and another. "That chap's got arms," muttered Tom. A panel splintered, and the pieces came rattling down the steps. "That's one done," came the cheery voice again. "Oh, so they've left the key in this one!"

The key turned in the lock, the door swung open, and a man with a candle in his hand stepped down into the cellar—a square-shouldered man of middle height, about thirty, with a clean-shaven, capable face. "Hulloa, partner! Is this where you usually spend your evenings?" he said in a gently bantering tone.

Tom began to explain, but, what between worry and exhaustion and the ugly blow on his head, he became quite unintelligible. The other cut him short. "Come up out of this, boy," he said. "Someone's been using you pretty bad. What you need is a glass of something hot inside and a little cold water out. Then you'll feel heaps better."

Now that the suspense was over Tom felt as weak as a rag. He reeled and almost fell. The other put an arm round him and half led, half carried him up the stairs and put him in the big red- cushioned arm-chair by the kitchen fire. "Now just you sit there and wait till I tell you to move," commanded the new-comer.

"But I can't. I've got to find my dad. They've taken him," protested Tom.

"I reckoned as much," quietly replied this amazing man. "But it ain't going to help him or you either, sonny, to go charging after him this hour of the night. You do as I say, and it'll be all right."

The man had a wonderful way with him. Tom sank back, and leaned his aching head against the cushions. He felt almost content. Quietly, and yet as quickly and deftly as if he had done nothing else all his life, the stranger coaxed the fire into life again, put a kettle on to boil, and while the water was getting hot set the table. He seemed to know by instinct just where everything was to be found. As soon as the kettle began to sing he took out a flask, poured some of its contents into a tumbler, filled it up with water, and gave it to Tom. "Drink that," he said. "It's old Bourbon, none of your 'tangle-foot.'" Tom obeyed, and a grateful warmth ran through his veins.

"Now for that head of yours." He got a bit of sponge and some rag, and with fingers gentle as those of a woman washed and bound up the cut on Tom's head. "Nothing serious," he said consolingly. "You'll be right as rain in the morning."

Next minute he was frying bacon from a cherished flitch which hung on the rack, and which Tom and his father only cut from on Sundays. The savoury smell made Tom realise that he was fearfully hungry. The other made tea in the old brown pot, and toasted bread. "Pull up, boy," he said, "and eat hearty. You need it."

Although Tom felt as if it was wrong for him to be feasting while his father was in the hands of Fulton and Co., yet he made an excellent meal. When it was over the other filled and lit a corn-cob pipe and pushed back his chair. "My name's Saxon," he said, "Walter Saxon, if you want it all. Yours, I reckon, is Holt, though I don't know your front one."

"Tom," said the boy.

"Son to John Holt?"

"Yes—only son."

"So those hoodlums bounced your father and corralled you in the cellar. Ben Lomax was one, I reckon. Who was the other?"

Tom stared. Who was this man who knew so much? "Fulton he called himself."

"Let's hear all about it," said Saxon. He saw the doubtful look on Tom's face, and laughed. "Oh, I ain't one of the gang, though I don't wonder you're suspicious after what they've done to you."

"I'm jolly sure you're not one of them," exclaimed Tom hotly. He had known this man less than an hour, yet felt he would trust him with his life.

"As long as you feel that way, it's all right, sonny; now go ahead and tell me about it."

Tom gave a brief sketch of the events of the afternoon. Saxon listened attentively. "So they took your dad away, and left you in the cellar."

"He didn't even say good-bye," said Tom.

"That wasn't his fault, Tom. I'll lay they filled him up with some yarn about your meeting him at the station. And when they got there they said you'd been delayed, and that he'd miss the boat if he didn't jump in quick."

"So they did take him to Liverpool?"

"I reckon so. It's true enough the _Arabia_ sails early tide to-morrow. We can't catch her, or I'd have had you on the way by now."

Tom stared.

"You want to know where I come in? Here's the facts. Your uncle Jim was my greatest pal. When he died he got me to promise I'd go right away to the Old Country and find his brother John and tell him he was to have Sunk River."

"Then it's true?" gasped Tom. He had quite made up his mind that Fulton's whole story was an elaborate lie.

"About Sunk River? Yes, that's right enough. He left the whole outfit to your father. Didn't speak of you. Didn't ever hear of you, I reckon. You were born since he and your dad quarrelled and Jim left for Canada."

"What do they want with father, then?"

"To get the place out of him, sure."

"Why?"

"Now you've got me, Tom. I can't say. All I know is that Stark's always coveted the place. Of course, it's mighty pretty grazing. The most sheltered ranche in all that country. Beautiful grass, good water, and cliffs all round."

"Who's Stark?"

"The boss of the whole outfit. The biggest, ugliest blackguard in all the North-West. A man that couldn't run straight to save his life, and yet so infernally clever that he's dodged the law for twenty years past."

"Then Fulton and Lomax were sent by him?"

"Aye, and he employs scores more like them. Cattle thieves, moonshiners, fur stealers, shady lawyers—they're all in his net."

"And they're taking dad out to him!" cried Tom.

"Taking him—yes," said Saxon. "But he ain't there yet by a long chalk. We'll be on their trail to-morrow."

"But the _Arabia_ will have sailed."

"The German boat leaves Plymouth to-morrow night. She's a twenty-three knotter. With luck she'll reach New York the same day as the _Arabia_—may even beat her."

"Then we may catch them in New York?"

"That's what I'm hoping to do, sonny."

"You don't think they'll do anything to dad first?"

"Not they. If your father's anything like his brother he'll stick to his word, and I reckon they know it."

"They'll never get him to sell," said Tom proudly. "Dad doesn't change his mind."

Saxon nodded approvingly.

Tom went on: "Supposing we don't catch them at New York, Mr. Saxon?"

"Don't you dare 'mister' me! Call me just Saxon. I'm proud of my name. Reckon it's good enough for everything—Christian name and all. If we should happen to miss them at New York, we'll just have to follow them for all we're worth."

"Where to?"

"West, by Chicago, Winnipeg, and Regina."

"And after that?"

"If we're so blamed unlucky as not to catch them before that, I reckon we'll have to interview friend Stark."

"You mean they'll take dad to him?"

"Bound to."

"And where does Stark hang out?"

Saxon shook his head. "That's one thing I don't know, sonny. But if need be we'll find out. Don't you worry. We'll come out top dogs. Now I reckon it's time to turn in. I've fed the stock. The old horse was whinnying as I came by. I suppose you can get someone to look after things while you're away?"

"The Graingers will do that for me," said Tom, getting up. In another half-hour he was in bed. But it was a long time before he got to sleep, and when he did he had ghastly nightmares of his father tied to a stake, while grim, copper-faced Indians sat round in a ring and sharpened gruesome instruments of torture.

NEW YORK Harbour flashed in brilliant sunshine as the huge liner came gliding through the Narrows and headed for her slip in the East River. Tom Holt, leaning over the rail near the bow, stared across the twinkling water at the great statue of Liberty which towered blackly against the pale spring sky.

Saxon followed his glance and smiled grimly. "Rum lot, these Americans, Tom. Sticking that thing up at the gate of the New World. After all, I suppose they're right, for there's liberty to do any blamed thing you please, from pitch-and-toss to manslaughter, with one only condition."

"What's that?" inquired Tom.

"That you can pay, my lad," replied Saxon rather grimly. "'Money talks' is their pet proverb over here, and you'll find it's true before you've been here a great while."

Tom was silent a minute, thinking hard. Then he looked up. "That's put an idea into my head, Saxon," he said slowly.

"Out with it," smiled Saxon.

"I've been wondering all the time why Stark is so keen about getting hold of Sunk River. I've read that there's lots of gold up in the North-West. Could there be any at Sunk River?"

Saxon shook his head. "Never heard of gold within hundreds of miles of the place. No: I think you'll have to guess again, Tom."

There was silence a minute. Then Tom said irritably: "I wish to goodness they'd hurry up. The _Arabia_ must be berthed by now."

"I expect she is," answered Saxon philosophically. "But you needn't worry, Tom. The Chicago Limited don't leave till 11:50, and Fulton won't go on before that."

"They may go some other way."

"I don't think they will. Fulton's not the fellow to waste time, and it's much the quickest way. They can't go up the lakes from Buffalo by steamer, for the ice is not out yet."

"You think we're likely to catch them at the railway station?"

"I do. But don't call it a station, sonny. It's a depot in this country."

The liner slackened speed still further as she passed through the tangle of traffic at the mouth of the East River. Huge ferries shot at twenty knots across her bows, tugs shrieked and snorted, strings of heavy mud scows blocked the way. Tom was almost dancing with impatience by the time the tug got hold of the ship to swing her into her berth.

The boy's patience had been pretty severely tried. Heavy head winds had cut their speed all the way across, and they had learned from the pilot that the _Arabia_ had beaten them by nearly three hours.

The Customs came as a finishing touch. Indeed, the delay in the draughty shed was so long, that even Saxon began to look serious, and glanced at his watch more than once. Though neither had more than hand-baggage, they had to wait their turn, the names being taken alphabetically. Half-past ten sounded before they were free, and, grabbing Tom tight by the arm, Saxon steered him across the crowded muddy cobbles outside and into a waiting tram-car.

The pace at which that car whizzed through the roaring streets startled Tom. But even so, it was a long way to the Union Depot, and when they reached the entrance to the enormous station, it was barely thirty seconds to train time.

"She starts right on the minute," shouted Saxon, and was off at a tremendous pace. Tom had to run to keep up.

The rush of passengers, the clanging of huge engine-bells, the whizzing of steam nearly deafened Tom. But all the same he kept his eyes open. Next moment he found himself alongside an enormous train, composed entirely of long, heavy corridor cars. "Stay here and keep a sharp look out," Saxon bade him, and darting away down the train, was lost in the crowd.

Tom stared about. No one in the least resembling his father or Stark's two accomplices came in sight.

"Take your seats," came a shout. The train was actually moving when Saxon came rushing back. "In you get," he cried; "they must be aboard." Before Tom quite knew what was happening he was in the train which was gliding rapidly out of the station.

"We've got no tickets," he gasped.

"Get 'em on the train," replied Saxon. "Come along. We've got to go through every car." Tom followed his friend through the whole length of the train, from the first Pullman sleeper to the last baggage car. Their search was unsuccessful. Of all the two hundred or more passengers not one was the least like those they were looking for.

When they had passed through the last car, Tom turned to Saxon in alarm. "We must go back," he exclaimed.

Saxon shook his head. "She don't stop till she gets to Buffalo. No, Tom, I think we'd best go through to Regina. We're dead sure to catch them there, for that's where they'll leave the train, whichever way they've come."

"But why aren't they in this train?" asked Tom miserably. He was horribly disappointed.

"I can't tell for certain," said Saxon. "Fulton may have had business to keep him in New York, or—and I'm beginning to fear it's likely—he had a wire from one of Stark's spies to say I'd gone to England. In that case he naturally suspected that I was hot on his heels and stayed behind on purpose to dodge me."

"I felt so sure we should find dad in New York," said Tom.

"I know. But we'll find him all right, lad; be sure of that." And Tom, glancing at the strong, resolute face of his friend, took comfort.

Presently Saxon got up to speak to the conductor. A bald- headed, thick-set man, with a beaky nose and heavy black eyebrows and moustache, came down the car. Tom noticed he limped a little. He sat down opposite Tom and in regular American fashion began at once to ask questions.

"You're English, I guess," he said.

"I am," said Tom.

"What do you think of this country?"

"I've only been in it about an hour, so I haven't had much time to think about it," answered Tom, amused in spite of himself.

"Gosh, that's pretty slick work! You came by the _Arabia_, I guess. Fine boat, ain't she?"

"No; by the _Fürst Bismarck_. She got in after the _Arabia_."

"Sakes! I wonder you caught the train. You must have been in an almighty hurry."

"I was," said Tom shortly. But the other was not discouraged.

"Going West?" he asked.

"Yes."

"California, maybe?"

"No; to Canada."

The other laughed. "You want to stay British," he said. "Wal, every man to his taste. The States is good enough for me. Hev a cigar?" and he pulled out a case of big black weeds.

Tom assured him he did not smoke, and just then Saxon came back. The American offered him his case, but Saxon refused. The man asked more questions, but he got so little out of Saxon that he grew discouraged, and at last got up and went off to the dining-car.

"You didn't tell that man anything?" asked Saxon. Tom thought he spoke rather anxiously.

"Not much," answered Tom, in surprise. "Only that we came by the _Fürst Bismarck_, and that we were going to Canada. Was that wrong?"

"The less you say to anyone the better," said Saxon emphatically. "But never mind. There's no harm done. Come and have some lunch."

All day the train roared westwards across the great State of New York. When night came they were skirting Lake Ontario, and Tom had glimpses of a vast expanse of hummocky ice and desolate snow-lined shores shining coldly under an Arctic moon. He was surprised at such cold so late in the year. "It's a sight harder than I ever saw it at Berrymead," he told Saxon.

"You'll see it harder yet, my boy. It's black winter still in the North-West. The ice won't go out for a couple of weeks yet."

It was all very new and wonderful to the boy, and, in spite of his worries, he took keen interest in everything, and asked no end of questions. Saxon was glad to see it, and encouraged him. He was getting fond of this lad. "There's real good stuff in him," he said to himself. "He's developing every day."

Tom met a number of new dishes at dinner. Clam broth, quails on toast, pumpkin pie, and salted almonds. He made a capital meal. At ten o'clock the negro car porters came along and set to work letting down the bunks. Tom and Saxon had a "section" between them. Tom took the upper berth and Saxon the lower. Tom found it so awkward to undress in the cramped space behind the leather curtain that he gave it up as a bad job and merely took off his coat, waistcoat, collar, and boots.

The bunk was most comfortable, with a capital spring mattress, but Tom found he could not sleep. He lay hour after hour while the train thundered across the flat lands beside the Great Lakes. Like all American trains, the car was overheated, and what between that and the salt clam broth he had had at dinner, Tom felt his throat getting absolutely parched. At last, in despair, he got up and, sliding quietly down out of his berth, made his way through the vestibule at the end of the car to the anteroom where the big filter stood. He filled a cup to the brim with ice- cold water, and drank eagerly. Then he sat down to cool off.

"That's a heap better," he said to himself after a while. "Now I believe I'm cool enough to get forty winks."

The swing door opened noiselessly, and Tom's stockinged feet made no sound on the thick carpet of the car. As he moved silently up the narrow corridor between the heavy leather curtains which hung down on either side, he suddenly became aware that someone else was afoot. Not one of the coloured porters, but a white man was stealing very cautiously along in front of him.

"What on earth is he up to?" wondered Tom, and some instinct made him stop and crouch close between the ends of the curtains.

"Hanged if it isn't the same chap who came and yarned to me this morning!" he muttered. "I could tell him anywhere by his limp."

The man was tiptoeing along absolutely noiselessly. Heavy silk shades were pulled over the electric globes in the car roof, but there was plenty of light for Tom to see that the American was taking the utmost precaution to make no sound. Also that he had something gripped tight in his right hand. He was fully dressed, and a close-fitting fur cap covered his bald head. "Why, he's stopping opposite our section," Tom muttered again. "That looks fishy. 'Pon my soul I believe he's going to try to pick Saxon's pocket." He almost chuckled. "Silly ass! Saxon sleeps with one eye open. He'll give him beans. If not—well, I'm here," and Tom braced himself up for a rush.

With one hand on the heavy curtain, the man stopped and looked sharply up and down the car. With an ugly shock of surprise, Tom noticed that the black moustache had vanished; so had the bushy eyebrows. His little, deep-set eyes glittered keenly in the lamp- light.

Apparently satisfied that all was well, the man pulled the curtain aside with his left hand. Quick as lightning up went his right; something long and bright flashed before Tom's eyes, and before the boy could so much as move, was driven downwards with tremendous force into the very centre of Saxon's bunk.

"He's stabbed him," groaned poor Tom, then, recovering himself, he gave a yell which roused half the train, and made a furious dash at the murderer. The latter turned with a snarl, hesitated just a second; then, as curtains were flung aside and bare legs swung out over the edges of the bunks, he turned and ran with amazing swiftness up the car. The door stuck a trifle. The man wrenched it open. But it delayed him just long enough for Tom to catch up. As it slid back the boy jumped fair and square upon the murderer's shoulders, and man and boy together rolled headlong through the opening, and out on to the rear platform.

The car was the last of the train, and the platform was surrounded by a three-foot iron rail with a padlocked gate at the side. It was snowing fast, and the platform was thick with the clinging flakes.

Tom was no chicken. His muscles were hard with years of outdoor work. And he had the other at a disadvantage. Even so he could not hold him; the fellow's strength was simply amazing. He grasped the rail with both hands, and, with an enormous exertion of muscle, hoisted himself up, Tom still clinging on his back.

Some old Berserk strain which had slumbered through the centuries in Tom's ancestors awoke. He saw red. Yet, even in his fighting fury he knew exactly what the ruffian was trying to do—that he meant to heave him clear over the rail on to the snow-clad track that spun beneath them in the glare of the tail lamps.

Tom shifted the grip of his right arm, bringing it tight under the other's chin, and at the same time made a desperate effort to kick the other's legs away from under him. So, for a furious moment, they struggled together on the swaying platform while the long train thundered westward through the bitter night and the driving snow. Tom was dimly conscious of loud shouts, of men packed in the doorway, trying to force their way through. Next moment the train went swinging round a curve. The lurch swung Tom and his enemy heavily against the gate at the side of the platform. With a snapping crack the padlock gave; the gate flew open and instantly they were gone. Horrified faces stared blankly at the empty platform with its trodden snow.

If Tom Holt and the bald-headed man had fallen on the rails, ten to one they would both have been killed on the spot.

As it was, the swing of the train whirling round the sharp curve flung them both clear of the metals, and they plunged headlong into the deep drift which filled the ditch at the edge of a low embankment.

The shock tore them apart, and Tom found himself floundering, gasping, deep buried in the icy powder.

"He shan't escape," was the boy's one idea, as he struggled to free himself from the clinging snow.

At last he got his head up, only to see Saxon's assailant plunging away at right angles to the line, making for the thick brush which lay at the far side of the railway clearing.

With a wild yell of rage, Tom dashed after him.

The snow was still falling thickly. The bald-headed man had a long start. For one moment Tom saw him, an uncouth black shadow through the mist of flying snowflakes. Then he was gone. At the same moment the boy put his foot into a deep hole and went sprawling on his face. His head struck a stump hidden by the snow, and he lay, stunned.

When he came to himself he was flat on his back on a cushioned seat in the smoking-car.

"He's all right," said somebody; "nothing worse than a crack on the head."

"Thank Heaven for that, doctor. I thought the brute had knifed him."

Tom started violently and sprang to a sitting position. The voice was Saxon's!

The boy stared in blank and utter amazement. Had he dreamt the whole thing, or was he dreaming now? Only a few minutes ago he had distinctly seen a long knife plunged apparently into Saxon's heart, yet here was his friend standing beside him as well as he had ever been in his life.

At Tom's puzzled expression, Saxon burst into a hearty laugh. "It's all right, sonny. He didn't get me that time."

"B-but I saw him!" stammered Tom.

"You saw him rip thunder out of one of the company's superfine down pillows," answered Saxon. "I reckon I'll have to pay for it. But I got his knife, anyhow," and he produced a murderous-looking bowie with a nine-inch blade.

"I heard you crawl out," explained Saxon. "I've a way of sleeping with one eye more or less open. I reckoned there'd be trouble of some kind before morning, and that was his chance. So I just fixed up the pillows to look as much like your humble servant as possible, and slipped up into your bunk. Sure enough, he'd been waiting. Made me want to howl to see him crawling along with that big knife of his, and when he jabbed the pillow I nearly burst."

"Wish I'd known," put in Tom ruefully. "I thought he'd done for you."

"I hadn't an idea you were watching," said Saxon more gravely. "And you didn't give me half a chance to stop you. You were after him like a bull after a red rag, and before I could do a thing you were both over the end rail."

"It was a mighty brave act, young man," said the doctor, who had been standing by.

"It was that," agreed Saxon heartily. "I'm proud of you, Tom."

Tom flushed with pleasure. Praise from Saxon was praise indeed. "Only wish he hadn't got away," he said regretfully.

"No fault of yours that he did," returned Saxon emphatically. "We couldn't hold the train or we'd have chased him. But," and he smiled grimly, "it isn't exactly a pleasant night to be out alone in the woods. Ike Foxley will be sorry for himself before morning."

"Foxley—is that his name?" exclaimed Tom.

"That's it. I recognised him when he was trying to pump you this morning. Now, if you're all right we'd best turn in again. We're not due in Chicago till eight o'clock, and if this snow goes on we'll be a bit late."

Saxon was right. At breakfast the conductor told them that they would not reach Chicago till past ten.

Tom was miserable. "We shall lose the connection," he groaned, and Saxon could hardly get him to eat a mouthful of the excellent chops and buckwheat cakes and maple syrup.

"When you've been out here a bit longer," said the elder man kindly, "you'll know it's not a mite of use worrying about anything—let alone trains."

They were no sooner out of the heated train and standing on the bitter, draughty platform of the great Chicago station than a sharp-faced boy in a blue uniform came hurrying up, shouting:

"Anyone o' the name o' Holt?"

"My name's Holt," said Tom.

"What initial?" asked the lad, looking keenly at Tom.

"T," said Tom.

"Thet's all hunky," said the boy. And shoving a letter into Tom's hand he was lost in the hurrying crowd.

Tom tore it open. Saxon saw his face change as he read it. Without a word he handed it over.

"To Thomas Holt," it ran. "Take warning. It'll be best for you and your dad, too, if you go right home again. No harm's meant to the old man, and he'll be shipped safe back if he's reasonable. You go further than Chicago and neither he nor you'll ever see England again."

There was no signature, no date, no heading, no postmark on the envelope.

Tom looked anxiously at Saxon.

"Scared, Tom?" inquired the latter.

"Only for dad," replied the boy.

"Want to go back?"

"Not me," said Tom stoutly.

Saxon smiled. "That's all right. We leave for Regina by the three-thirty. Come on. We'll get some kit here. It'll save time when we get to Regina."

"HERE'S where we hit the trail," said Saxon, as they stood on the wooden platform of Regina station and watched the great Canadian Pacific express roll heavily westward across the vast white expanse of prairie.

"It's hard to think it's the beginning of April," said Tom, as he gazed wonderingly at the snow-covered roofs and the fur-clad people who hurried out to the waiting sleighs.

"Suppose it is for you," smiled Saxon; "but the snow won't last much longer, and when it goes it goes in a hurry. That's why we've got to make tracks as fast as we can. You can travel twice as quickly on runners as on wheels."

"I'm ready as soon as you are," said Tom simply.

"We leave to-morrow morning," said Saxon, as he gave the baggage-man the checks for the luggage. "Send these to the Elgin Hotel," he told him. "Come on, Tom."

The hotel was a small one in the back street. "Came here to be quiet," explained Saxon. "Where's Mr. Bates?" he asked the waiter.

"He left some time ago," answered the waiter. "Mr. Vyner's the new owner."

Saxon looked annoyed. "I'm sorry," he whispered to Tom. "Bates was a good fellow. I don't know Vyner. But as we're here, I'll stay. It's only for a night. Now I must leave you. I'm off to get news from a man I know. He'll very likely be able to tell me whether Fulton and Lomax have reached here yet."

"But they couldn't!" exclaimed Tom.

"It's just possible. They might have come by Buffalo and Toronto. You stay here," he went on. "And make yourself comfortable. Supper's at seven, but I shall hardly be back before nine. I must see about ponies for the trip."

"Shall I wait for you?"

"No, have your supper at seven and turn in early. You've a precious tough day before you to-morrow. And—mind—not a word to anyone."

Tom promised, and Saxon hurried away. Left to himself, Tom unpacked the furs and blankets which they had bought in Chicago and set them ready for an early start. Then a bell clanged noisily through the wooden walls and he went down to supper.

There were only two other men besides himself in the dining- room. One was a little wizened chap with a thin face and a peaked nose, the other a burly bear of a man with huge hands and heavy features.

They sat at a table by themselves, and Tom, who was hungry, paid more attention to a juicy steak and fried potatoes than he did to his neighbours.

A sound of loud voices made him turn. The two men had evidently quarrelled. What about Tom had no idea, but the big man was abusing the little one like a pickpocket.

The latter was badly frightened. He shrank back, his miserable little face yellow with fear.

"Brute!" growled Tom. He was the sort who always takes the part of the under dog. He half rose from his chair, then remembering Saxon's warning, changed his mind and called the waiter. "What's the matter? Why don't you stop it?" he asked.

"I daren't," said the man. "That big feller—Snell's his name—he's a holy terror. He's always quarrelling with someone, and when he comes in here we don't get no other customers."

"You must be a fool to let him in," said Tom contemptuously.

"Dirty, sneaking cur!" roared the big man. And Tom saw his huge leg-o'-mutton fist suddenly descend upon the little chap and send him and his chair sprawling on the floor.

Every drop of blood in Tom's body boiled. He was across the room in two jumps. "Why don't you hit a man your own size?" he cried furiously.

"Keep your meddling nose to yourself, or you'll get it knocked off," growled the big fellow insolently.

The small man picked himself up and crept behind Tom. "I didn't do nothing to him," he whined. "Don't see why he went fer to hit me."

"All right, he shan't touch you again," said Tom reassuringly.

"Who's a-going to stop me?" sneered Snell.

"I'll try," answered Tom quietly.

"I'd take on three like you," jeered the other.

Tom was tingling to be at the brute. But again the thought flashed upon him of Saxon's warning.

Snell saw his hesitation. "Doggone ef the Britisher ain't climbed down already," he laughed. "Thet's always the way with the scum they sends out here from the Old Country."

Tom threw prudence to the winds.

"If you won't give your word to leave this man alone I'll do my best to teach you," he exclaimed hotly.

"Come and do it then," returned the brute with a cruel laugh.

At this moment the waiter came running in with the hotel keeper. "Gentlemen, gentlemen, I can't have this in a respectable house!" cried the latter.

"Skeered of the police, eh? All right; Britisher, come outside. There's plenty o' moon to see by."

"Not in my yard!" cried the hotel keeper. "You mustn't make a disturbance there."

"Anything to oblige," said Snell. "That there house next door's empty, ain't it, Mister Vyner?"

"Yes, it's empty," answered the proprietor eagerly.

"We'll go along there, then."

"Don't go, sir," begged the wizened man of Tom. "He'll half kid you."

Snell gave a jeering laugh. "I'll attend to you later, Wiley," he said threateningly.

Torn cut him short. "Come on!" he cried.

Snell led the way. There was a board fence round the hotel backyard. Snell clambered clumsily over it. Tom followed, and, much to his surprise, the little man came too.

"I'll second you," whispered the wizened little chap. And Tom almost laughed at the confident way he said it. One blow of Snell's ponderous fist would pulverize the poor little chap.

The night was all white moonlight and bitterly cold. In the deserted yard the untrodden snow lay hard and smooth. There was no mark of footsteps, and the black windows stared emptily out on the deserted place.

Tom kept a wary eye on his enemy. He had heard of American methods from Saxon—the kicking, biting and gouging. He did not mean to be caught unawares.

But Snell squared up in proper fighting style. Tom, glancing at the man, felt that his chances were slim enough. This was a fighter. A great, hairy, primeval brute. He was bull-necked, thick-lipped, and his short, coarse hair seemed to bristle on his round bullet head.

His eyes were narrow, cunning, deep-set, thatched with thick eyebrows, his nose was blunt, and his jaw heavy. His hands were huge, and even through his coat Tom saw the gnarled muscles of his upper arms rise and writhe.

But Tom himself was no chicken, and the past three weeks had given him confidence in himself. With the instinct of a born fighter, he saw that he had one pull over his enemy. He was far more active. Those short, thick legs were no match for his own long, clean ones. "I'll have to keep away," he thought. "Keep away till he's blown. And the snow's all in my favour."

With a quick motion he flung off his coat and stood lightly poised before the other.

Snell paused a moment, eyeing the boy fiercely. Then he came on with a rush.

Tom dodged. As he did so something sprang monkey-like upon his back, a pair of thin arms wrapped themselves tightly round his neck, and at the same moment Snell's ponderous fist caught him square on the forehead, and down he went like a log in the snow.

Tom dodged. As he did so something sprang monkey-like upon his back.

Voices came dimly to Tom's ears.

"See if the sleigh's here yet, Wiley."

A door opened and shut. There was a moment's pause. Then came Wiley's whining tones. "No, it ain't there yet."

"There ain't no hurry, anyway." It was Snell speaking. "Thet Saxon ain't a-coming back till nine."

Tom opened his eyes. His head was ringing abominably, and he could feel blood trickling down his face. He tried to put his hand up, but found he could not. He was tied hard and fast with one rope round his body and arms, and another round his ankles. A cork gag was firmly fixed between his teeth.

He was lying flat on his back on the bare floor of a dirty, unfurnished room. But there was fire in a small stove, and Snell and Wiley sat at their ease, one each side of it, on a couple of empty packing-cases.

"Hello, the tenderfoot's woke up! Hed a good snooze, stranger?" observed Snell with a sarcastic grin.

Tom had never felt more like murder in his life. But as it was sheerly impossible for him to move, he contented himself with glaring at his enemy.

"Don't look pleased, do he," remarked Snell. "Ungrateful dog, Wiley, seein' as how we've took so much trouble play-acting fer his amusement. Quite a pantomime, warn't it, Wiley?"

"Hee-hee!" laughed the ugly, wizened imp, chuckling horribly. "No, he don't seem best pleased, not so pleased as Stark'll be, hey, Snell?"

"I reckon it ought to be a smart bit in our pockets," grinned Snell. "We did the trick proper. Say, I was skeered Saxon might hear ye, Wiley, when you was listening outside o' the door in the hotel."

"They don't hear me very easy," answered the little wizened man. "I ain't heavy, like you, to make the boards creak. And I didn't have no boots on either."

"You was skeered just the same," jeered Snell.

"So'd you be if ye thought as Saxon was going to get hold of ye," retorted Wiley.

"Saxon won't trouble us much longer, I reckon," growled the bully. "Stark's a match fer him."

Tom quivered all over with excitement. What did the fellow mean? What new plot was afoot now?

The men went on, quite regardless of their helpless prisoner.

"You reckon Vyner's got his story right?" inquired Wiley.

"He ain't got a thing to do but tell the truth. Say the kid had a row with a chap, and they went into the next yard to settle it, and he ain't seed Holt since. Saxon's no fool. He'll reckon as Foxley has come in by the evening train and got on his track, and he'll take his gun and go out to Foxley's place. Ef he reckons to drive, Vyner's got the sleigh man fixed, and ef he walks I reckon the trap's jest as good."

Wiley gave his horrid, dry chuckle. "Say, Snell, Stark's a dandy, ain't he?"

"He is that," admitted Snell. "He's the only one o' the bunch as has the wits to get ahead o' Strong-hand Saxon."

Tom felt he would go mad if he had to lie here much longer and listen helplessly to these scoundrels' plots.

"They'll kidnap Saxon just as they have me," he groaned to himself. "And I can't move a finger to warn him. What an idiotic fool I've been! Shall I ever learn any sense?"

Presently Wiley spoke again. "This here game must be costing Stark a pretty penny."

"That's so," answered the other. "But I reckon he means to make about a thousand per cent on all he spends. That's about his usual profit."

"Sunk River's a mighty fine place. There ain't any such grazing in the Nor'-West, an' you can grow fine crops there too," said Wiley thoughtfully; "but seems to me it ain't wuth such a terrible lot of money."

"You kin bet your boots it's wuth about ten times as much as you think it is, ef Stark wants it so bad," returned Snell emphatically.

"He's safe for it now, anyway," grinned Wiley. "Old man Holt'll sign anything, let alone a bill o' sale, when he sees we've got the kid here to rights."

A jingle of bells came faintly from outside. Wiley jumped up. "Here's the sleigh. Let's get along. We ain't got any too much time."

Snell stooped and picked up Tom as easily as if the strapping young farmer's son had been a child. "Reckon you wishes you hadn't left England, don't ye," he asked jeeringly.

"Hold on a minute!" exclaimed Wiley. "Lemme see ef the coast's clear."

A moment later he was back. "All right," he said. Snell slung Tom over his shoulder, carried him out of the empty house into the deserted street, where a pair-horse sleigh was waiting. He flung the boy roughly into the bottom of it and covered him over, head and all, with a buffalo robe. Tom heard him exchange a word with the driver, who apparently walked away. Then Snell and Wiley got in, Snell took the reins, and the horses started off at a sharp trot.

Tom, lying helpless in the bottom of the sleigh, heard the runners hiss across the hard packed snow. He was bumped up and down and half suffocated with the thick rug which covered his head.

He was horribly frightened. Where were they going? What was happening? Was the terrible Stark actually in Regina, and were these ruffians using himself as a bait to deliver Saxon into Stark's hands? In spite of the bitter cold, the perspiration dripped from the boy's forehead, and he shook all over like a man in an ague.

But the fit only lasted a minute. With a powerful effort Tom pulled himself together. "Nice chap, I am," he thought bitterly, "chucking it like this! What would Saxon think of me? If only I had my hands loose! One thing's in my favour, at any rate. They can't see me under this rug."

He at once began writhing and wriggling in a silent, desperate effort to get his arms free.

The rope was in two turns round his body, and so tight that already both hands were swollen and numb. To move them was absolute agony, but Tom set his teeth and pulled for all he was worth.

The right arm, he found, was hopeless, but the left he could move a little.

The coarse rope tore his shirt and cut deep into his flesh.

Snell felt him moving. "Lie still, can't ye?" he growled, and kicked him savagely in the ribs.

"I'll make you pay for that, you brute," said Tom to himself, grinding his teeth in helpless rage. He lay quiet for a moment, then began again.

The rope was giving. He was sure of it. Another minute and a throb of exultation shot through him as he realised that his left arm was free. He slipped his hand across to his right waistcoat pocket, and a thrill of delight shot through him as he found that his knife had not been taken from him.

But his triumph was short-lived. Snell had felt him moving again. "Lift that robe, Wiley, and see what the cub's a-doing of," he cried angrily.

Tom heard. He felt Wiley lift the fur, and went quite mad with the same desperate rage that had seized him when he had seen Foxley stab Saxon in the train.

As Wiley lifted the rug Tom's free left arm shot up, he snatched the whip from Snell's unsuspecting hand, and with all his strength sent the lash curling across the flanks of the near- side horse.

The horse, a powerful bay, sprang forward with a jerk that nearly broke the traces. There was a howl of rage from Snell and a scream of abject terror from Wiley.

"Hold him, ye fool!" roared Snell with a savage oath, and pulling furiously at the reins.

But before Wiley could interfere out flew the lash again and cracked across the quarters of the off-horse. Terrified already, the poor brute gave a wild kick which sent the splash-board flying in splinters, then dashed away at full speed.

Snell, reviling horribly, tugged with all the strength of his powerful arms. But the horses had the bits in their teeth, and were pulling the light sleigh by the reins alone, as they galloped madly down the long, straight, moonlit road. It was as complete a runaway as ever was seen.

Of the three in the sleigh the only one who was not frightened out of his wits was Tom. He was beyond it. His one feeling was sheer exultation that, whatever happened, these two treacherous blackguards were in as bad a hole as he was. "If I'm killed, so will they be," he thought triumphantly.

Snell kept howling to Wiley to hammer Tom over the head, to kill him, do anything to him. But the wizened man was far too scared. He was literally paralysed with terror, and crouched in his seat with his legs drawn up, his eyes goggling, and gripping the side and back of the sleigh with both his skinny hands.

The sleigh swung and bumped like a feather at the heels of the maddened horses. The powdery snow flew in clouds. The runners fairly screamed over the icy road. The few passers-by stopped and turned and stared at this startling apparition which whizzed past with the speed of light, but not one attempted to stop the frantic horses.

Snell, in his desperate efforts to pull up the runaways, merely made things worse. He pulled so hard every now and then that the front of the sleigh hammered into their heels, driving the poor brutes clean crazy. But even if Tom could have spoken he wouldn't have told the man what he was doing wrong. This stolid farmer's son had turned into a different being. His lips were tight set, his eyes glowing with the light of battle. He had wedged his feet against the splashboard, his back against the seat, and so keeping himself partly steady had managed to open his knife, and was sawing away at the rope, which still held his right arm.

Snell saw what he was doing, and roared again and again to Wiley to stop him. But Wiley was perfectly helpless, and Snell himself was far too busy hanging on to the reins to do anything else. Tom saw it, and even in their desperate plight chuckled with savage glee.

Tom cut himself badly, but he cared not a jot. Another moment and the rope fell away. Both hands were free. Slash, slash, and he had his feet loose. But Wiley was plucking up courage. He rushed at Tom. The boy seized the whip lying at the bottom of the sleigh and made one desperate slash at the miserable wretch. He put all his energy into that slash. Wiley gave vent to one piercing, craven yell, then toppled headlong from the sleigh.

The miserable little reptile went bounding over and over in the snow, and next moment was a mere black dot in the distance on the white, moonlit expanse.

"Hope I've killed him," growled Tom remorselessly. Then, knife in hand, he turned on Snell.

Snell gave a beast-like howl of fear and rage. But even now he did not drop the reins. Tom saw that the man's face was purple with exertion, that the great veins were standing out knotted and swollen on his forehead, while in spite of the cruel frost the sweat streamed down his cheeks. Knife in right hand, left grasping firmly the back of the seat, Tom stood over Snell like an avenging angel. His mind was working like lightning.

What was he to do? Unless he took the reins a smash was certain. If he took them he was at Snell's mercy.

He made his decision like lightning.

In front of a sleigh is a raised metal fork through which the reins pass.

Tom pointed to it with his knife. "Hang your reins over that fork," he sternly ordered.

Snell only snarled.

"Hang your reins over the fork," roared Tom again. "Quick, if you don't want this into you." And he brandished the knife over the man's shoulder.

With a mad howl of fury Snell suddenly hurled the reins far out on to the backs of the madly galloping horses, and turned on Tom like a wild beast.

THE crisp snow crackled under the feet of Saxon's pony as he trotted sharply back towards the town, and the strong moonlight threw his shadow black as ink on the pure white surface.

Not a cloud sullied the steel-like glitter of the stars, not a breath of air stirred the sombre foliage of the firs and hemlocks that bordered the track.

But Saxon never gave a thought to the beauties of the night. "Wonder if I did right to leave the lad," he muttered to himself, as he dug his heels into his sturdy mount and pressed it to a sharper canter. "He's a good boy, Tom. Plucky, too. I like him first-rate. Well, one can't expect a tenderfoot to learn everything all at once. If Stark don't get us both first, Tom Holt'll grow into a man that Canada will be proud of."

Suddenly he reined in his pony sharply, and horse and man stood like a bronze statue. Sounds carry far in the clear stillness of a great frost, and Saxon's quick ear had caught the thud of galloping hoofs and the shriek of sleigh-runners hurtling over hard-frozen snow.

"A runaway, for a dollar!" he muttered sharply. "Coming this way, too. Mighty queer at this time o' night. Get up, pony!"

His whip cracked across the pony's flanks, and the strong little beast sprang into a gallop.

The trees broke away on either side of the trail, and Saxon was on the steep bank of a frozen creek. Exactly opposite, and coming straight towards him, a pair of horses galloped madly, dragging at their heels a swinging, bounding sleigh.

"Great ghost, there'll be a smash!" exclaimed Saxon horrified, and next moment he had forced his pony down the steep bank. Its iron-shod heels rang an instant on the hollow ice, then, picking his spot, with a wild scramble he was up the far side and galloping hard towards the runaways.

Saxon went straight for their heads. Every trick of the plainsman was his, and he knew he was taking heavy chances. But he had to, or else the sleigh and its occupants would go clean over the creek bank, a drop of at least twenty feet. At the mad pace they were travelling, horses, men, and all would certainly be killed.

As he had hoped, the runaways swerved a trifle. At the same moment Saxon saw that the reins were hanging loose on the backs of the horses. Whirling his pony round on its hind legs, he forced it hard against the near side horse, and, leaning over, seized the dangling reins.

He knew too much to try to stop the mad beasts at once. If he had, he would simply have been whisked clean over his pony's head. Guiding his own animal by pressure of his knees, he gradually threw his weight on the reins, and steered the runaways in a wide circle to the left.

For a moment they galloped with unabated speed, then, breaking through the untrodden surface of a drift, they checked, and though they still struggled frantically, the steady pressure began to tell. Presently they stood still with hanging heads and heaving sides, while the steam rose in thick clouds into the windless, frosty air.

As the sleigh came to a standstill, one of the two occupants suddenly sprang out, and ran at full speed towards the thick belt of trees to the left.

"Stop him!" roared the other, and never in his life had Saxon been more startled than to recognise Tom Holt's voice.

But he wasted no time in questions. He flung the reins to Tom. "Stay with the horses, whatever happens!" he cried, and swung his panting pony after the running man.

The snow was deep on this side of the clearing, and Saxon's pony, breaking through the crust, plunged in up to the girths. Snell reached the trees fifty yards ahead of Saxon, and vanished instantly among the ink-black shadows of the gloomy forest.

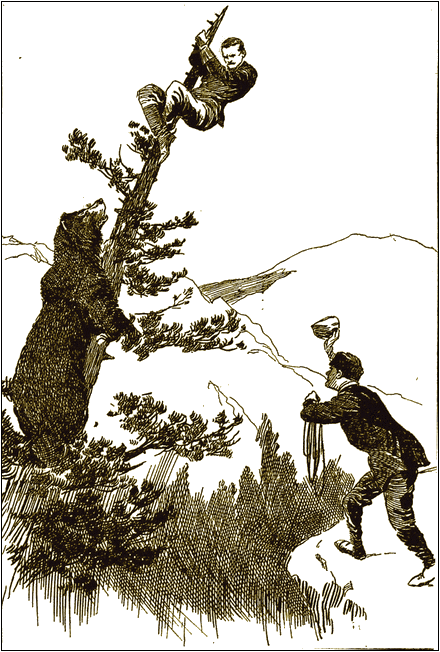

Tom, watching the chase with quivering interest, saw Saxon rein his pony on to its very haunches and dismount with a spring on the off-side. As he did so, a whip-like crack rang from the forest, and the poor pony, rearing wildly, fell over almost on top of Saxon, gave one quiver, and lay still.

As it fell, so did Saxon, and lay motionless in the snow.

For a moment Tom was within an ace of dropping the reins and rushing to the rescue.

"Stay with the horses, whatever happens," that was what Saxon had said, and Tom set his teeth and determined not to blunder a third time.

He quite believed that Saxon was either killed or badly hurt, and it was one of the worst minutes he had ever spent. He could have yelled with relief as he saw Saxon's left foot rise above the snow and wag twice to and fro. He knew it was a signal to himself.

Next moment a figure emerged from the black shadow of the trees and came cautiously towards where Saxon lay.

It was Snell.

In his right hand was something which glinted in the moonlight. Tom could not make out whether it was a knife or a pistol.

Saxon lay like one dead. Snell's bulky form, head forward, shoulders stooped, crept across the snow like some monstrous ape.

Nearer and nearer. Still Saxon did not move the fraction of an inch. Snell gained courage, straightened up, walked more rapidly.

"Thinks he's dead," said Tom to himself with beating heart.

Snell was within ten yards of the dead pony, when Saxon's right arm shot forward as if driven by a spring, a pistol cracked, and Snell, with a hideous howl of pain and dismay, dropped his weapon and blundered over backwards.

"Hurrah!" shouted Tom, unable to control himself any longer.

Still Saxon did not move. It was Snell who got up, and, groaning horribly, began staggering away back towards the trees.

Saxon let him go, and it was not until at least five minutes after Snell had reached the trees that Saxon rose to his feet, dusted the snow from his clothes, and stretched himself leisurely. Then he turned to Tom. "Tie those horses up and come over here," he said.

The horses were quiet enough now. Tom led them to a dead stump and hitched them.

"Why did you wait so long after Snell was gone?" was his first eager question.

Saxon smiled. "Just what I'm going to show you, lad. A first lesson in woodcraft. Come with me."

He followed Snell's first track towards the woods. It went only a little way in, and stopped behind a large log. "What does that tell you?" he asked Tom.

"Looks as if he had laid down there."

"Exactly; he was blown with his run, and dropped in the first shelter he came to. Does that tell you anything else?"

Tom looked puzzled. "The shot which killed your pony came almost at once," he said. "How could Snell have shot from here?"

There was a gleam in Saxon's kindly eyes. "Go over there, Tom. Examine the snow, and see if it tells you anything."

"There's another track here!" cried Tom next moment excitedly. "Longer and narrower than Snell's."

"Good lad! Have you any notion whose tracks they are?"

"Not Stark's!" exclaimed Tom.

"Yes, Stark's," answered Saxon. "I'd know those large, firm prints anywhere. Snell could not possibly have fired that shot. Not only because he was behind the log there, and probably couldn't see me, but he was much too blown to shoot straight. I owe the loss of my pony to Stark."

"Then why did Snell come out after you—not Stark?"

"Stark knows me," answered Saxon, laughing. "He thought I might be foxing, and sent Snell instead. Snell has a bullet through his right shoulder, but I only wish it was through Stark's instead."

"And where's Stark?" cried Tom.

"Gone."

"Where?"

Saxon shrugged his broad shoulders. "I could follow his tracks," he said. "But we haven't time. We must get back to the town at once. On the way, perhaps you'll be good enough to tell me how you come to be gallivanting in the woods here instead of asleep in your bed at the Elgin."

Tom looked rather sheepish, but told exactly what had happened.

When he had finished Saxon gave a dry chuckle. "Say, sonny, they get a rise out of you every time, don't they?"

Tom hung his head.

"Never mind, lad," said Saxon encouragingly. "You'll learn. I don't blame you at all, and you've come out top dog, that's the main thing."

"What are we to do now?" inquired Tom.

"Pick up that skinny rascal if we can find the pieces, and then go and put the fear of Heaven into Vyner," said Saxon, whipping up the horses.

But Wiley was gone, and Saxon would not wait to look for him. The face of the waiter at the Elgin was a study when Saxon and Tom entered. He spun round and tried to bolt. Saxon made one jump, seized him by the collar, kicked his legs from under him, and flung him into a corner.

"Lie there!" he growled, and the wretched man, shaking all over, lay still as a whipped dog.

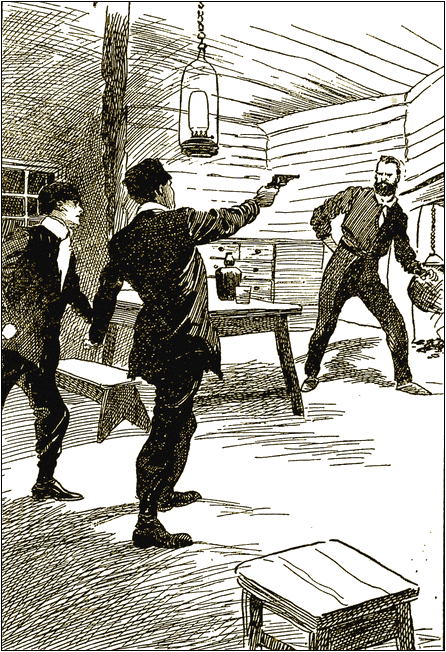

Vyner, hearing the noise, came running in. The moment he saw Saxon he pulled a pistol.

"Ah, would you?" roared the scout, springing on him and sending him, pistol and all, flying across the room with a tremendous backhand blow.

"Help!" howled Vyner, but Saxon had him again, jerked him to his feet, shook him till his teeth rattled, then slammed him into a chair, and stood over him.

"So you're another of Stark's men, are you?" he exclaimed contemptuously. "'Pon my soul, he does choose some beauties. I've a mind to kill you for treating that boy as you have to- night."

Saxon's blue eyes seemed literally to blaze, and he looked so formidable in his rage that Tom, for the first time since he had known Saxon, realised the tremendous personality of the man.

"I didn't want to do it," groaned Vyner in abject fright. "Stark made me."

"That's a lie. Stark bribed you, you mean. Now, tell the truth as you value your skin. When did you see Stark last?"

Vyner hesitated.

"Give me a stick, Tom," said Saxon coolly.

The mere threat was enough. Vyner went green. "This afternoon," he exclaimed hurriedly.

"When did he come to town?"

"Two days ago."

"Where is he going?"

"I don't know. I swear I don't."

"No, he wouldn't tell a thing like you. Now, when were Fulton and Lomax here?"

Vyner hesitated the fraction of a second. But Saxon's face was enough. "Two nights ago."

"Who was with them?"

"An Englishman. Looked like a farmer."

"Aye, now we're getting to it. And they went on next morning?"

"Yes."

"How?"

"In a pair-horse sleigh."

"Whose sleigh did Snell have to-night?"

"One of Stark's."

"That's all right. Tom, get me a rope or a strap."

Tom found a rope, and Saxon tied Vyner up tightly in the chair and gagged him. He treated the waiter in the same way.

"Now, Tom, you take those horses round to the stable, rub 'em down, and feed 'em. They'll be wanted again in an hour."

"Right," said Tom. "I'll have 'em fresh as paint by then."

When Tom brought his horses round again Saxon had hot coffee ready. He also had a number of neatly-corded packages at the door, which he loaded into the sleigh. Among other things was a small hand sleigh and a big parcel of provisions.

Saxon chuckled as he stowed the latter away. "Spoiling the Amalekites, Tom. I've cleared Vyner's larder."

"And what have you done with him?"

"Stowed him in the cellar along with his waiter. Wonder what sort of a story he'll tell the police to-morrow. Put this fur coat on, Tom, and nip in. We've got to be thirty miles from here by daybreak."

SAXON seized Tom by the shoulder and shook him. "Wake up, lad. They're coming."

Broad awake in an instant, Tom flung the thick rug back and sprang up.

The sleigh was at rest on top of a great wave of snow-clad prairie, and a blood-red sun was heaving itself over the eastern forest into a sky shot with splendour indescribable.

A thin breeze whistled out of the north-west, and the cold was intense.

"Where?" cried Tom, straining his eyes in the direction of Saxon's pointing finger.

"See, just under the sun. Six of them, as I live."

Tom's eyes were good, but not trained like Saxon's. It was a minute or more before he was able to distinguish their pursuers, mere tiny specks against the great white sheet of snow.

"Quicker than I thought," said Saxon. "And all mounted."

"But they'll see us," cried Tom.

"I mean them to," was the quiet answer.

Tom was amazed. "We can't tackle six of them in the open," he exclaimed.

"Quite true, lad. We are not going to." And Saxon smiled.

He whipped up the horses, and the sleigh went hissing down the far side of the low hill.

Tom was lost in wonder. He had the deepest faith in his friend. But how, with two tired horses, he was going to keep ahead of half a dozen mounted men was quite beyond him.

Saxon, however, seemed quite calm. He had slightly changed the direction of the sleigh, and was driving diagonally towards a belt of wood to the right—that is, to the north of their line of route.

Long before their pursuers topped the rise the sleigh was among the trees. Now Saxon turned due north, and keeping the horses well up to the traces, they were presently through the wood, which was only a belt less than a mile wide, and on open prairie again.

Now Tom got a fresh shock.

Saxon turned the horses' heads due eastward.

"Are we going back to Regina?" demanded Tom.

"Not just yet, boy. We've got to find your dad first." And Saxon smiled his strange, quiet smile.

The runners grated on frozen grass. Tom saw that Saxon had driven the sleigh on to a patch of bare, wind-swept ground.

"Out you get!" cried Saxon sharply, pulling up the horses. He himself sprang from the sleigh, and, untying the small hand sleigh, or "jumper," which had been fastened to the back of the other, began loading it with a speed which made Tom gasp.

In less than five minutes all their small possessions were on the sleigh. Then Saxon led the horses to the edge of the bare patch, and, setting their heads towards Regina, gave each a sharp cut with the whip.

Surprised beyond words, Tom saw the horses throw up their heads and start at a sharp canter for home.

Saxon walked back to where Tom stood staring. "Feel like breakfast, Tom?" he said coolly.

Tom merely shook his head. He was beyond words. Saxon took the rope of the "jumper," and started at a brisk trot back towards the belt of woods which they had just passed through. Tom blundered through the snow hard at his heels.

Reaching the wood, Saxon made for a clump of undergrowth, plunged into it, scratched the snow away, and sitting down, began to unpack some provisions.

"Cold grub this morning, Tom. But we'll have a fire to-night." Then, seeing that Tom was paying no attention to him, but staring with all his eyes out on to the prairie, he chuckled softly. "Getting the hang of it, eh, lad?" he asked.

Tom looked round. "I think so," he said a little doubtfully.

"Watch, and you'll see the whole circus for yourself. But don't talk loud."

"You may be sure I shan't," returned Tom indignantly.

Saxon had set out bread, butter, cold bacon, and a little tin of brown, baked Boston beans, when the peculiar rustling sound of horses galloping across hard-frozen snow came to their ears, and all of a sudden six mounted men swept into sight barely three hundred yards away.

They were following hard on the track of the sleigh.

Instinctively Tom crouched low in the snow, holding his breath. He could hardly believe that their pursuers could not see them, and it seemed amazing to him that Saxon could go on calmly munching a thick bacon sandwich while danger was so deadly near.

First of the six rode an immensely tall man on a powerful black horse, which he sat magnificently. In that marvellously clear air Tom could actually distinguish his dark face and hawk- like nose.

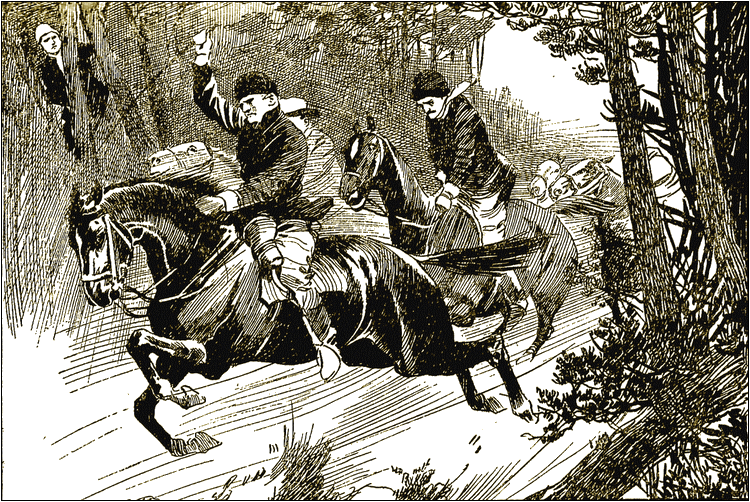

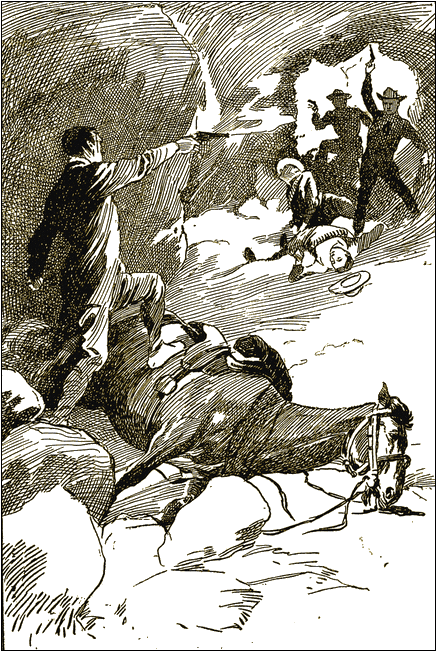

First of the six rode an immensely tall man on a powerful black horse.