RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on the cover of "La Domenica del Corriere," 7 Aug 1927

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on the cover of "La Domenica del Corriere," 7 Aug 1927

"Sons Of The Sea," C. Arthur Pearson, London, 1914

"Sons Of The Sea," C. Arthur Pearson, London, 1914

"Sons Of The Sea," C. Arthur Pearson, London, 1914

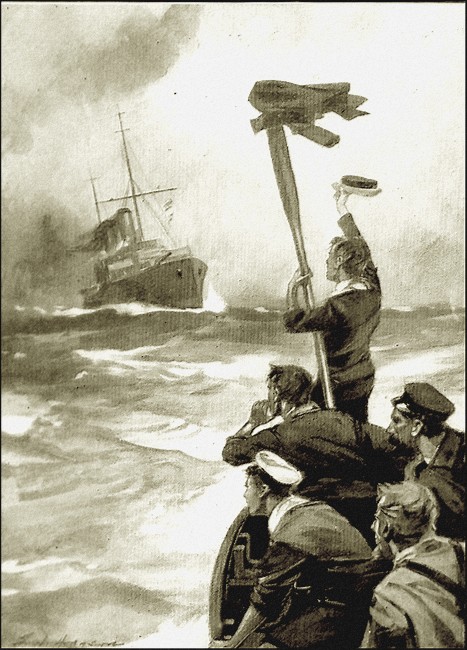

Soon she was near enough for them to see

the white feather of foam sprouting under

the keen stem of the long yacht-like craft.

"HULLO, what's that?"

Roddy Kynaston, a sturdy, brown-faced boy of sixteen, started to his feet.

"A couple of guillemots quarrelling over a herring," suggested his companion, without moving.

"I thought I heard a shout," said Roddy doubtfully.

Arnold Gillam laughed.

"My dear Roddy, don't be absurd. Pendarg Head is a trifle of four hundred feet high, and no boat comes near those beastly reefs at the bottom. Unless some chap's cruising round in a balloon, I don't see where a shout could come from."

"Must have been gulls then, I suppose. But it didn't sound like it. I'll just have a squint over the edge."

Pendarg Head is one of the highest cliffs on the Welsh coast. It is not everyone who could follow Roddy's example and gaze down calmly from its tremendous crest into the waves which break upon its rugged base.

"See anything?" asked Arnold presently.

"Not a thing except gulls and a couple of ravens. And yet—By Jove, there it is again!" he exclaimed sharply. "Didn't you hear it?"

"I really believe I did," answered Arnold in a startled tone. "It sounded like someone shouting for help."

"It was, too," and curving one hand over his mouth, Roddy sent a piercing call echoing downwards.

"Help! Help!" came back the answer.

This time there could be no mistake about the cry. It was the voice of someone in distress.

"Where are you?" shouted back Roddy.

"Here; about half-way down. Can you see?"

The voice was so far away that it came to their ears like a whisper. But they both heard it clearly enough.

"Can you see him, Roddy?" asked Arnold.

"No, but the voice comes from over there to the left. Nearer the headland."

"Phew, the worst place of all! How on earth shall we get at him? Ask him if he can hang on."

"Can you hang on till we fetch help?" shouted Roddy, sounding each word very clearly and distinctly.

"Be quick. I can't hold on much longer."

Roddy turned to Arnold.

"What can we do? The tide's up. We can't reach the beach. And there's no rope nearer than the village."

"Yes, there is," replied Arnold quickly. "There's one at Davies' farm. They use it for getting sea-birds' eggs. You stay here, and I'll fetch it." With that he darted off.

Roddy hurried along the edge of the cliff in the direction of the Point, and reaching the very end went down on hands and knees and crept to the edge.

"Where are you?" he shouted again.

At once the reply came back, faint but distinct:

"Here, just below you."

Roddy stared downwards. The cliff was broken by hundreds of projecting ledges, by deep fissures and crannies. His glance roved across these, down, down for hundreds of feet.

Then suddenly he caught sight of the figure of a boy about his own age clinging like a limpet to the bare face of the perpendicular rock.

It was nearly three hundred feet below him, and more than a hundred above the fringe of black rocks which showed their ugly heads among the breakers.

"Hang on," Roddy shouted encouragingly. "They're bringing ropes from the farm. We'll have you up in no time."

"I've got good hold for my hands. It's my feet are slipping," came up the thin, small voice from the depths.

It seemed to Roddy an hour before help arrived. Really it was barely ten minutes before Arnold Gillam, followed by Davies, the farmer, and another man, came running across the open down.

"My goodness, but it's a bad place!" exclaimed Davies, as he came panting up alongside Roddy. There was dismay on his face as he looked over the edge, and caught sight of the boy clinging against the cliff face half-way between sea and sky. "We shall never be able to reach him," he added despairingly.

"Because of the overhang, you mean?" answered Roddy quickly.

"That's it. The rope will hang too far out for him to reach."

"Then someone will have to go down after him," answered Roddy.

"That's no use," said Davies, shaking his head. "He could never reach him."

"Yes, he could. See that gap to the left? If you let me down there, I feel sure I could climb across the face of the cliff, and carry the rope to him."

"Roddy, it's madness," declared Arnold. "No man alive could do it."

"It's the only way," said Roddy stubbornly. "It's either that, or leaving the chap to hang there till his grip goes."

"The young gentleman is right," remarked the farmer. "But it's no use pretending that it's not dangerous."

Arnold looked at Roddy. He was about to protest again, but the words died on his lips. The expression on his chum's face showed him that argument was useless.

Without delay Davies drove an iron bar which he carried firmly into the turf a little way back from the landward end of the fissure which Roddy had pointed out. Meanwhile the man with him fixed a heavy leather belt around Roddy's body, and to it attached one end of the rope.

"Have you a knife?" asked Davies.

Roddy pointed to his sheath knife in his belt. Davies nodded. Then, all being ready, Davies put a turn of the rope round the crowbar, and Roddy walked over the cliff backwards.

Roddy had a good head for heights, and did not suffer from giddiness. So long as he was in the fissure he got on well enough. But below came a sheer face smooth as a wall. Here there was nothing for it but to be lowered perpendicularly. Once over the edge, he found himself spinning like a joint on a spit, and the motion made him horribly dizzy.

It was a huge relief when at last he reached a ledge, and found himself at the top of the lower and more sloping portion of the cliff.

He looked round. The boy whom he was trying to save was still a goodish way below, and at least thirty yards to his right.

The poor fellow was clinging with both hands to a little shelf of rock which stuck out from a big, smooth bulge in the face of the limestone. How he had ever got there was a puzzle.

Roddy had a good look at the cliff, and made up his mind that it would not be difficult to get within ten or fifteen yards of the other. But then came a space where the rock looked smooth as a cement wall. How he was to cross it he had not the faintest idea.

Still, it had to be done, and looking at it made it no easier. He signalled to let out rope again, and, shouting encouragingly to the boy below, started clambering towards him.

After a few moments of active scrambling, he reached a point about fifty feet above the other, and the same distance to the left.

Suddenly the rope tightened behind him and he heard a shout from above. Listening carefully, he made out Arnold's voice giving him the startling information that they had come to the end of the rope.

"The man's gone back for more," shouted Arnold. "He'll be here in a few minutes."

"How much longer can you hold on?" called Roddy to the boy below.

"Not long, I'm afraid," gasped the other weakly. "I'm getting cramped in my fingers."

Roddy gave one quick glance at the white, strained face below him, then without hesitation freed himself by unbuckling his belt, and scrambled away downwards.

In a very short time he had gained a spot level with the other, but about twenty feet to one side of him. And those twenty feet were smooth rock without hand or foothold.

It was a situation fit to daunt anyone, but Roddy was not yet at the end of his resources.

"Hold on," he shouted cheerfully. "I'm coming."

Pulling his knife from its sheath, he started cutting stops in the rock, but he had only time to make them just deep enough to bear his weight.

From below came up the angry growl of the surf boating among the knife-edged rocks. Roddy's heart throbbed as he clung and cut and cut again.

Once the rock gave under his foot, and he swung out a hundred and fifty feet above the abyss, clinging by the fingers of one hand only. Luckily for him, he managed to find a little projection on which his other foot could rest until he was able to cut a fresh step.

The knife blade wore away rapidly. But the steel was good, and did not break. What troubled him most was the dizziness caused by his tremendous exertions. Nothing but the sight of the other boy watching him with agonised eyes could have kept him to the terrific task.

Foot by foot Roddy won his way across the gap.

"Keep higher," murmured the other boy weakly.

Roddy looked, and saw the advice was good. He must aim for the top of the bulge, to the face of which the other was clinging. His next two niches were cut in an upward direction. Then, to his joy, he noticed a Little fissure running horizontally across the smooth face. It was only a tiny crack, but it was enough to get his toes into.

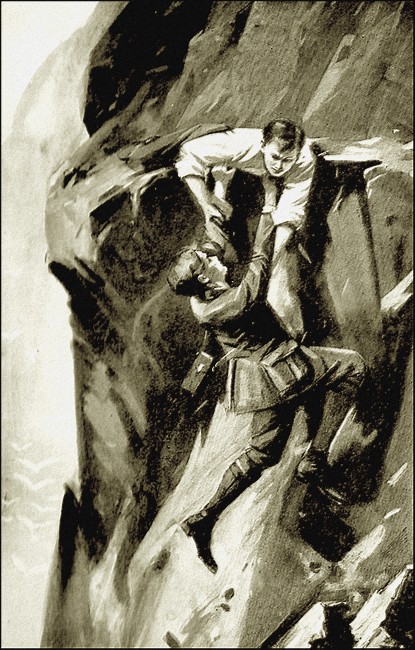

In another minute he had scrambled safely on to the upper side of the bulging rock, directly above the other lad.

This rock was wider than it had looked, and there was room enough to lie flat upon it. The worst of it was that it sloped at a very awkward angle. Roddy felt by no means sure that he would be able to bear the other's weight without slipping forward.

But there was no time to waste. He lay down on his face, flattening himself as tightly as possible against the rock.

Then he stretched out both hands.

"Now," he said. "Steady's the word."

"Now," said Roddy, "steady's the word."

He caught the other by the wrists and pulled. For Home seconds it was an open question whether he would lift the other, or whether both together would slide outwards, and drop helplessly into the abyss.

But pluck and hard training told, and inch by inch the other came up until he got his knees over the edge, and scrambled into comparative safety. Then, as he dropped beside Roddy, from above came a wild burst of cheering which echoed along the cliffs and sent the sea-birds wheeling in startled clouds.

For some minutes the two lay on their narrow, sloping refuge, both too utterly done to move or speak. Roddy was the first to pull round.

"Are you all right?" he asked hoarsely.

"Yes, thanks. I say, it was awfully decent of you to come down after me. I'm hanged if I'd have cared to tackle that last bit."

"That's all right," said Roddy hastily. He had the true British dislike to being thanked. "But what in the name of goodness brought you in such a place?"

"Photographing," was the reply, as the rescued lad sat up and touched a small camera slung over his neck. "It was a raven's nest. A late one with young in it. It's just above us. I got the photo all right, and was coming down again when I slipped. If I hadn't collared hold of that edge I should have gone right over," he added, with a slight shudder.

Roddy nodded.

"It's a beast of a place," he said sagely. "Strikes me the sooner we're out of it the better. But the rope's over so far above, and I'm not keen on crossing that smooth bit again."

"No need to. We can go down the same way I came up. It's not bad. The only thing is we shall have to wait till the tide's out before we can get home."

Ten minutes later, they fetched up on a ledge about fifty foot above high-water mark—a ledge so broad that there was room to lie down at full length in comfort. Roddy promptly stretched himself out, and the other followed his example.

Roddy glanced at his companion. He was as tall as himself, but lean, and almost skinny. Yet in spite of his lack of weight, he looked as tough as steel wire.

"Mind telling me what your name is?" asked Roddy.

"Denny—Drake Denny. What's yours?"

"Roderick Kynaston. I'm new to these parts."

"Oh, you're the son of the new doctor at Portglask?"

"Yes, we've only been here a few months."

"Thought I hadn't soon you before. Father and I live at Llintyre, two miles the other way. I wish you'd come and see him."

"I'd like to," said Roddy. "I suppose you've been there a long time?"

"Ever since dad retired. He was in the merchant service—skipper of one of the big Blue Star boats. He had a bad fall about ten years ago, and had to have one leg taken off. So the directors gave him a pension, and we've got a little place by the sea. Dad can't live out of sight of the sea."

The two sat and yarned in the sunshine. Roddy took a great fancy to his new acquaintance, and told him all about his ambitions for starting a patrol of Sea Scouts at Portglask.

Young Denny was much interested, and time passed so quickly that they were both surprised when, looking down, they saw a strip of wet shingle baring at the foot of the cliffs.

"Good business!" exclaimed Roddy. "Let's get down."

"All right. But don't hurry. It'll be another hour before we can get round the Point."

Drake was right, and it was nearly sunset before they scrambled over the wet rocks at the end of the Point, and reached Portglask beach.

"Hullo, look at the crowd!" said Drake, pointing to about fifty fishermen and boys who were gathered on the sands.

At the same moment the crowd caught sight of the boys, and a hearty cheer went up.

Headed by Arnold Gillam, they came running up and surrounded Roddy and Drake, shaking their hands and congratulating them.

"What's up, Arnold?" asked Roddy, looking very red and confused.

Young Gillam laughed.

"Why, you old duffer, don't you realise that you're a blooming hero?"

"Don't talk rot, Arnold."

"It's not rot at all. You did a jolly plucky thing, and one that appeals to all the chaps here. Buck up, and be civil, for here's your chance to work your Scout scheme. There's old Morgan, who told you that his son hadn't time to play silly games like scouting. But I guess he'll let you rope Joe in if you tell him that it was scouting taught you how to climb rocks."

"Do you really think so?" asked Roddy doubtfully.

"Of course I do, you old duffer. I'll ask him myself if you like."

"Do—that's a good chap, and give Denny and me a chance to clear out."

"HERE'S the house," remarked Drake Denny, as he and Roddy rounded a corner of the coast road.

"What—that? Why, it's a boat!"

Young Denny burst out laughing.

"You've hit it at once, old chap. It's an old ship turned keel up. It looks a bit rum from here, but I can tell you it's jolly snug inside."

The old ship stood in a patch of garden gay with sweet-peas, roses, and hollyhocks. As the boys came up through the garden the door opened, and Captain Denny himself stumped out. He was shorter than his son, but immensely broad. His thick hair was quite grey, and so were his bushy whiskers. His face was the colour of well-tanned saddle leather, and his grey eyes had a merry gleam.

"That you, Drake?" he cried in a voice which sounded like a small peal of thunder. "And this is Kynaston, I'll be bound. Come in, my lad. If I'd been able to walk as well as I once could, I shouldn't have waited this long before thanking you for saving my boy's life. No, don't blush. It was a plucky bit of work, and a clever one. I'll say that much, and then I'll not mention it again. Now come in, and I'll show you over my shanty."

As Drake had said, the place was as snug as could be inside, and full of all sorts of handy little dodges of its owner's invention.

All the furniture was from old ships. The bedrooms were fitted with bunks, the fire-places were ship's stoves. Even the range in the kitchen was an old ship's galley. The walls were covered with curiosities brought by the captain from all parts of the world.

Roddy was simply delighted.

"Tea, ahoy!" roared the skipper, when they got back to the sitting-room, and Maggie, his old housekeeper, brought in a piled-up tray.

There were Welsh scald cakes, which are the best bread in the world, fresh eggs from the captain's own poultry-yard, Welsh butter, which is as good as Devonshire, a great bowl of red and yellow raspberries, and home-made jam of several different kinds.

"You're the boy that's keen about Scouts," said the captain in his deep voice, as he passed his guest a cup of tea brimming with yellow cream.

Roddy only wanted starting. He did not stop until he had explained all his ambitions.

Captain Denny nodded gravely.

"Sea Scouts, eh! And a very good notion, too. And how many boys have you got as a start?"

"Four, sir. Drake here, Arnold Gillam, young Joe Morgan, and myself."

"There are two or three other chaps would join, if we could once got started," put in Drake eagerly. "But we've got no head-quarters yet."

"What sort of quarters do ye want?" asked the captain.

"A hut first, with a signal pole and some charts," answered Roddy. "And then, if we can run to it, an old boat of some sort which we could moor up the creek."

"Strikes me the boat would be easier managed than the hut," said the skipper.

"Why—how?" asked Roddy, his eyes shining.

"What about that old barge that's been lying on the mud up the Glaslyn these three years past?" demanded Captain Denny, turning to his son.

"The very thing," cried Drake. "I wonder who owns it?"

"Jones, of Glynavon," said the captain. "I know him well. I'll ask him."

"Would you?" begged Roddy breathlessly.

"Aye, of course I will."

"But he'll want a lot for her," said Roddy, his face falling.

"Bah, she's only worth her price as firewood! Five pounds would buy two like her."

"I've got two pounds in the savings bank," said Roddy.

"And I've three," added Drake.

"Don't draw it till I tell you," said the captain. "I'll do the bargaining."

He was as good as his word. Two days later Drake Denny turned up at Roddy's home in high feather.

"The barge is ours. Dad's got it for us!" he announced.

"You don't mean it? How much have we to pay?"

"Not a penny! Jones gave it to dad, and he's given it to us."

"Whoop, what luck! I say, this is fine. Let's go and see it."

"Just what I was going to suggest. Come on."

The Glaslyn was a small river that ran into the top of Portglask Harbour. It was only navigable for about three miles, and the barge lay some two miles up it. The tide was out when the boys reached the spot, and they had to take off their shoes and stockings and wade through deep and slimy black mud.

"I'm afraid she's pretty rotten," said Drake, as they climbed aboard.

"Her deck's sound enough, anyhow," replied Roddy, as he stamped on the weather-worn timbers. "So long as she's watertight she'll serve our purpose. Up with the hatch."

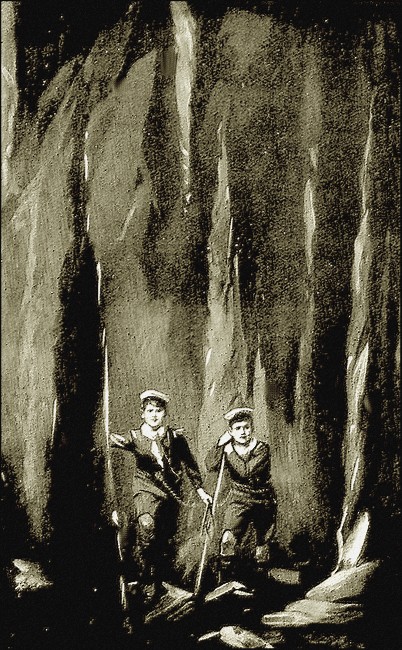

With some difficulty they prised up the main hatch, and peered down into the big, dark space below.

"Its all right," said Roddy. "There's hardly any water in her. And, by Jove, there's room enough for a troop, let alone a patrol. Now let's try the cabin."

The barge was a big, sea-going craft, and her cabin was much larger than that of the ordinary canal lighter. It was fairly dry, too, and in capital repair.

"This is great," declared Roddy. "Look, her stove is still here, and all right, barring rust. That'll save us at least a sovereign. You must have some sort of fire-place on your guardship, or you can't use it in winter."

Drake did not answer. He was looking round with a puzzled expression on his face.

"What's up?" said Roddy.

"Tobacco. Don't you smell it?"

"Come to think of it, I do."

"Someone's been smoking here quite lately."

"A tramp, probably," said Roddy carelessly.

"Just the sort of place for a tramp to shelter on a wet night."

"We haven't had a wet night lately. And the smell seems fresh."

"Well, don't worry about that. We've got lots to think about. How about moorings? We ought to set her down nearer to Portglask."

"That's a fact. Let me see. Sir Richard Ferguson is Lord of the Manor. We'll have to get his leave. As soon as we get home, I'll ask dad to write to him."

"Do. And then we shall want a boat as tender. That's going to cost something, unless anyone happens to make us a present."

"We ought to be able to pick up an old dinghy pretty cheap, and tinker her up ourselves," said Drake. "We must save our money for fitting up the hulk."

"That's it. We shall want davits and winches, and a flagstaff. Then we must paint her, and make a bigger cabin, and—"

"Steady on," broke in Drake, with a laugh. "We're not millionaires yet, and all that'll cost a pot of money."

"Oh, I know we must go slow to begin with. But I mean to do all that and more before I'm through. And we must all pile in and help. Which reminds me. The first thing is to clean her thoroughly. You and I can do that. Will you be able to come and give a hand to-morrow?"

"Yes, rather. I'll bring some soft soap and scrubbing brushes."

"All right. I'll get hold of a mop and a broom. And we'd better bring some grub, too. It'll be an all-day job."

"It'll take the best part of two days," said Drake, looking round at the thick grime which covered the planking. "We'd best sleep aboard. We shall be snug enough if we bring a couple of blankets."

"A very good notion," agreed Roddy. "We'll do that."

They spent most of the rest of the day overhauling their new possession. The bottom was pretty rotten, but they felt sure that she would keep afloat long enough to get her safe on the mud farther down the river. And then, as Roddy said, they would lay her bottom with cement and gravel, and make a fixture of her, with a gang plank from the shore.

They went home full of excitement, and breakfast was not over next morning at Roddy's home before Drake turned up, carrying a big bundle of soft soap and brushes with which Maggie had provided him.

Roddy's father took them and their loads up to the barge in his dogcart, before starting on his morning round, and they were soon at work, scrubbing away for all they were worth like a couple of housemaids.

First they cleaned out the cabin, then they set about the decks. The barge had been used to carry coal, and the black dust lay thick in every crevice. It was no joke trying to get it out.

By nightfall they wore both pretty well fagged out, and after a wash and a hearty supper rolled themselves in their blankets and turned in.

RODDY was deep in dreamless sleep when he was roused by a hand

on his arm. He started up sharply.

"'Sh!" whispered Drake. "There's someone aboard."

"Someone aboard?" repeated Roddy in a low voice.

"Yes. I've just heard a man's feet on the deck. Listen, there's another."

"I hear. And a boat, too. The tide's up, and she's bumping against the side. Who in sense can it be?"

"Haven't a notion," answered Drake, as he rose softly to his feet. "But we shall know soon enough. They're coming across to the cabin door."

Roddy sprang towards the door, with, as Drake thought, the idea of securing it. He himself had no wish for the intruders to find their way in until they were ready to receive them, and, if necessary, defend themselves against an attack.

"No use, Roddy. There's no lock," said Drake. "And it opens outwards."

"I know. I'm not going to try to bar them out, as if I was afraid of them. I'm going to see what they're after."

He flung open the door, at the same time flashing his electric torch, which he pulled from his pocket.

A rough-looking man, who had been just about to enter the cabin, started back in surprise.

"What do you want here?" demanded Roddy.

"Ho, I like that," answered the other, recovering himself. "I like that. Seems as how it's me should be asking that question instead of you, my lad."

"You are mistaken," said Roddy politely. "This barge is our property, and you are trespassing."

The man burst into a hoarse laugh as he turned to his companion.

"That's good. Listen to that, Joe. The nipper says as how the old barge is his. What d'ye think of that for a bit of cheek?"

A second man, a tough-looking customer wearing a ragged blue jersey and sea-boots, stepped up into the circle of light.

"Says it's his, does he, Sam?" he exclaimed harshly. "And where does he think he got it from?"

"It was given us by the owner, Mr. Jones, of Glynavon," answered Roddy.

The man called Sam laughed again.

Then he stepped nearer to the two boys, and with a scowl on his face remarked:

"You've been fooled, my lad. 'Tisn't his to give. The old craft belongs to Joe and me. So the sooner you clear out the better, if you don't want to be chucked out."

The man spoke with such cool assurance that for the moment Roddy was staggered. He glanced doubtfully at Drake Denny.

But the latter was not at all dismayed.

"That's all nonsense," he said shortly. "My father knows Mr. Jones well, and I'm jolly sure that Mr. Jones wouldn't give him anything that wasn't his to give."

"Well, he has this time," answered the man. "This old craft belongs to Joe and me, and you two'll just have to shift out of it."

"Have you any proof that it's yours?" demanded Drake.

"Proof, is it?" said Sam. "D'ye think I carries my certificate of sale around with me in my pocket? The barge was my brother's for ten year and more, and he left it to me. Didn't he, Joe?" turning to his companion.

"In course he did," replied Joe in a queer, hoarse voice. "And, see here, we haven't got time to stand here yarning all night. These younkers have got to get out of it, and the sooner they does it the better."

"It's no use trying to bluff us in that fashion," said Drake steadily. "You haven't given us any kind of proof that the barge is yours. And unless you can do that, it's you and not we who must shift."

Joe's eyes glittered nastily. He took a sudden step forward. But Sam put his arm out.

"Steady on, Joe. It's no use having a fuss, and I'm sure these young gents don't want it any more than you and me. See here, mister," he said, addressing himself to Drake, "there's just a little misunderstanding. You thinks as you own the old barge, and we two has the same sort of notion as regards ourselves. Now I know you'll just go home quietly. Joe and me'll put you ashore in the boat, and to-morrow we'll see Mr. Jones, and have the thing thrashed out proper."

Drake stared him full in the face.

"Why are you so precious anxious to have the barge to yourselves to-night?" he asked shrewdly.

"'Cause it's ours, and we wants to sleep here," answered Sam.

"H'm, funny place to come to sleep in at one in the morning," retorted Drake. "Especially as there are no mattresses or any other sleeping kit."

"Here, this'll do. We've had enough of this," exclaimed Joe angrily. "As I said afore, we've got something better to do than stand here all night arguing with you two nippers. Are you going out, or are you not? Give us a straight answer to a straight question."

"You've had it already," said Drake stiffly. "But you can have it again if you want it. No!"

Joe's answer was to jump at the boy, fling his big arms round him, and try to drag him out of the cabin. At the same moment Sam tried to serve Roddy in the same fashion.

But Roddy was ready for him. Quick as a flash, he jumped to one side, and thrust out his left leg, hooking Sam neatly under the knee and bringing him down on all fours with a crash that shook the whole cabin.

Then he dashed after Joe.

Drake was making a good fight of it, but he was so small and light that he could not do much against his big opponent, and Joe had already dragged him out of the cabin on to the deck.

All this time the only light had been Roddy's electric torch. Seeing he would need both hands to tackle Joe, he thrust this hastily into his pocket.

Outside it was pretty dark. Not pitch dark, for the stars were twinkling, but there was no moon. Anyhow, Joe didn't see him coming, and Roddy had him by the collar of his coat before he knew what was happening, and at the same time kicked his heels from under him.

Uttering an exclamation not generally used in polite society, Joe sat down suddenly on the deck with a bump that must have knocked most of the wind out of his heavy carcase, and Drake, whom he still clutched tightly, sat on top of him.

Roddy seized hold of his chum, jerked him out of the man's arms, and dragged him to his feet.

Quite what to do next Roddy hardly knew, but Drake had all his wits about him.

"Quick—the boat!" he whispered, and rushed to the side.

Sure enough, there was the intruders' boat bumping gently alongside.

"Get in, Roddy. I'll cast off," said Drake sharply.

By this time the man Sam had regained his scattered senses and also his feet, and with a howl of rage came out of the cabin like a rabbit bolting before a ferret. It was one more case of "more haste, less speed," for he never saw Joe, who was still sitting in a badly dazed condition just where Roddy had left him. The natural result was that he charged straight into him, and fell over him.

"You silly fool!" he roared. "What are you playing at?"

"Silly fool yourself!" howled Joe. "Take your dirty boot out of my mouth!"

"Where are them dratted boys?" shrieked Sam, picking himself up, and making a blind rush down the deck. "Where are they, Joe?"

Joe came limping after him. Suddenly he must have caught the sound of oars splashing gently, for he gave a shriek of dismay.

"They've got our boat. They've gone!" he wailed.

"We've gone all right," shouted back Drake Denny. "If we can't have the barge, we'll have the boat!"

The men on the barge replied with howls of rage, and wild threats of what would happen to the boys if they did not instantly bring back the boat.

But the only answer they got was a peal of mocking laughter, and in a very few minutes the boat had vanished in the darkness.

"We got out of that pretty well, Drake," said Roddy, as he tugged at his oar.

"Yes, thanks to you, old chap," answered Drake.

"We can share the credit," chuckled Roddy. "It was you thought of the boat. In the excitement I'd clean forgotten it for the moment. But what were those chaps after? Why were they so keen to get rid of us? That old barge can't possibly be worth anything to them."

"No, but there might be something in her that was."

"I never thought of that. You mean they'd got something hidden aboard her?"

"That's my notion," answered Drake. "They may have been doing a little job in the burglary line, or it may have been simply smuggling."

"Then the best thing we can do is to pull back to Portglask, and rout out a policeman," suggested Roddy.

"No need to go so far. We can find a bobby nearer than that. There's Griffith at Newbridge, and that's not a mile away. Let's get off there."

"Good business. If only he's at home, we'll have him there inside half an hour."

But it took some time to wake Griffith. It was the best part of an hour before they got back to the barge with the policeman.

"Pull softly," whispered Drake, as the dark outline of the barge loomed up ahead. "We must catch 'em napping if we can."

Roddy and Drake were both good watermen. They slipped in under the stern of the old craft without a sound, and, first making fast the painter, crawled aboard. Griffith, who was a big, heavy man of forty, followed them equally quietly, and for a minute they all three stood listening in perfect silence.

"I'm afraid the birds are flown," murmured Griffith. "There's only a couple of foot of water on the landward side. They could have got ashore all right."

He stole forward, moving wonderfully softly for so heavy a man.

"Wait," whispered Drake. "I'll have a look through the window. Lend me your lamp, Roddy."

The others waited, and presently the electric torch flashed out.

"No use," said Drake. "They've hooked it—and taken our blankets, too. What a beastly shame!"

He was right. The men had gone, and so had the blankets and the rest of the food which the boys had brought.

Griffith was very much annoyed.

"It would have been worth a bit to me if I'd caught 'em," he said in a disappointed tone. "And most like they've taken what they came after along with them."

"I'm not so sure about that," said Drake, who was standing in the middle of the cabin, sniffing like a terrier at the entrance to a rat-hole. "Roddy, can't you smell something?"

"My word, yes. There's a regular reek of tobacco."

"Tobacco," repeated the policeman eagerly, as he turned the slide of his bull's-eye. "You're just about right, my lad, for I got a whiff of it then. We'll turn this place out, and see what we can find."

All three set to work with a will, and from under the bulkheads they soon dragged out a heavy parcel done up in tarred paper.

"This is a find, and no mistake," said Griffith. "Evan Llewellyn, the coastguard, told me some time ago that there was baccy being brought in as hadn't paid no duty. Said it beat him where they was hiding it."

As he spoke, he ripped the parcel open. Tobacco sure enough. Black twist done up in pound packets. There were fifty of them in the bale, and they found ten bales in all.

"And what are we going to do with it now?" asked Roddy, staring at the piled-up bales.

"Wait till daylight, Mr. Kynaston, then take it down to the Customs at Portglask. There'll be a tidy few shillings coming to you and Mr. Denny here for finding of this stuff."

Griffith was right. The boys were awarded three pounds between them as their reward for the discovery of the smuggled tobacco. Two pounds they put into the funds of the new patrol, and the other they insisted on Griffith taking as his share.

A BIG, new oil-lamp, perfectly trimmed, shed a cheery glow on six boys assembled in the cabin of the old barge. The cabin itself shone like a new pin. The boards were scrubbed to snowy whiteness, The stove was blackleaded till you could see your face in it.

In the middle of the room was a table, a gift from Roddy's father, and home-made benches afforded sitting accommodation.

Drake Denny, an eager look on his thin, dark face, stood up quickly.

"Look here, you chaps," he began.

"That's not the way to begin a speech," put in Arnold Gillam chaffingly. "You should say, 'Ladies and gentlemen.'"

"Dry up, Arnold!" said Roddy. "Let Drake do it his own way."

"I'm not making a speech," retorted Drake. "All I want to tell you is that, as this is the first meeting of the patrol, we've got to elect a Patrol-leader. There's a bit of paper in front of each of you, and the way is for every chap to write down the name of the fellow he thinks will make the best leader on his paper, and then fold it up and pass it in. The chap who gets most votes is leader. Go ahead, now."

Five of the boys began to write at once. The sixth, Dick Harper by name, who was a cousin of Roddy's, and already a member of a land patrol, looked on.

"Now all pass your papers to Dick," said Drake. "Dick, you read them out."

Dick did so. There were four votes for Roddy, and one—this in Roddy's writing—for Drake.

"Roddy, you're Patrol-leader," said Drake. "Come and take the chair."

The others all clapped violently as Roddy moved to the head of the table.

"It's awfully good of you chaps," he said. "I only hope I shall be able to manage the job all right. I'll try, anyhow. Now, we must have a second. Names, please."

The result was four votes for Drake, one for Arnold.

Roddy wrote the names down in a book, with the date, and gave the other three Scouts their numbers. The remaining three were Arnold Gillam, Joe Morgan, and young Guy Griffith, son of the policeman.

"We ought really to have six, or, better still, eight," said Roddy, "but if we buck up we shall soon get some more. Anyhow, we've got a guardship. The next thing is to have a name. What do you say to calling ourselves the Seals?" The others all agreed.

"The County Commissioner has given us leave to wear regular Sea Scout kit. Same as land, only in blue serge, and bluejacket's cap instead of the ordinary Scout hat. Stockings, blue woollen, and long enough to turn up over knees when in boats. My father's given me a copy of 'Sea Scouting for Boys,' and that and the Chief Scout's book are the first two in our library.

"Now we've all got to buck up like anything. The first thing we must do is to get our guardship nearer the harbour. Sir Richard Ferguson has given us leave to berth her at the mouth of the creek, and as soon as there's a big spring tide all hands must chip in to get her down."

"That'll be Wednesday week," said Joe Morgan.

"All right. Wednesday week is the day, then. And the next thing we need is a boat. That's awfully Important."

"I think we've got one, Kynaston," piped up little Guy Griffith.

"Got one?" exclaimed the others.

"Yes, father told me to tell you that the boat those smugglers were using hasn't been claimed, and the chief constable says we may have it."

"Hurrah! that's great!" cried Roddy. "Now we can make some money."

"How?" asked Arnold Gillam.

"Why, sea-fishing, of course. Any of us who have spare time can go out hooking. We'll get a lot of shillings that way for our patrol fund, shan't we, Joe?"

"Aye, we will that," answered Joe, who, being the son of a professional fisherman, knew more about the game than any of the rest of them. "There's a fine lot of whiting in the bay now."

"We'll have some of them before we're much older," said Roddy. "When can we get that boat, Guy?"

"Soon as you like, father says."

"I can go to-morrow," said Roddy. "It's holiday-time with me. Who'll come?"

There was no answer at first. It seemed that everyone was busy.

"If none of the patrol can come," said Dick Harper, "I'm your man, Roddy. I'm not much use, but I can row a bit."

"All right, it's a go. We must start early, for we'll have to get some bait first."

"Come around to our place, and I'll have some mussels ready," said Joe Morgan gruffly. "I picked near a bushel to-day."

Roddy, secretly delighted at the true Scout spirit shown by this offer, gratefully accepted it, and after some further talk about the plans of the new patrol, all the boys scrambled ashore and tramped off to their homes.

Roddy and his cousin were afoot early next morning. They had first to fetch the boat, which was tied up near the Custom-house, then to go round to Morgan's for the bait.

They found Joe swabbing down the deck of his father's smack.

"Morning," he greeted them shortly.

"What d'ye think of the boat, Joe?" asked Roddy.

Joe cast a critical eye over her.

"Not a deal, to tell you the truth. She's old, and she's not got freeboard enough for sea work. But she'll serve if we tinker her up, and give her a lick of paint."

"You mustn't look a gift boat in the bow," laughed Roddy. "The great thing is that she didn't cost us anything."

"Aye, that's true," answered Joe, as he handed over a tin bucket full of mussels. "Here's your bait. If I was you, I'd try Doublehead Rock first. Tight lines."

"Seems a good sort," observed Dick, as they pulled away.

"Joe's one of the best," agreed Roddy. "He doesn't say much, but he knows a lot. He's fit for three badges already—'Boatman,' 'Watchman,' and 'Sea-Fisherman.' And he'd probably pass for 'Pilot,' too. There's not another chap of his age in Portglask that's as good a hand in a boat."

"Where's this Doublehead Rock he told us about?"

"A good way out. You'll see it when we're clear of the harbour."

They pulled on in silence for nearly an hour, then Roddy turned and pointed.

"See those two blunt-headed rocks sticking up out of the water? That's Doublehead Rock. Our mark's about two cables to the southward."

"That's Dutch to me," said Dick. "What's a cable?"

"A hundred fathoms," laughed Roddy. "Two hundred yards. The tenth part of a nautical mile."

"I see—roughly a quarter of a land mile south. You'll have to instruct me. I don't know the first thing about this game."

In a few minutes more Roddy gave orders to ship oars. Getting his cross-bearings, he manoeuvred the boat until he had her exactly on the mark, and then proceeded to anchor.

The anchor was nothing but a big stone with a few fathoms of stout cord attached. It went over with a loud splash, and, as soon as he had made sure it was holding, he set to work to get the lines out.

Roddy was all there when it came to sea-fishing, and his tackle was a cut above that used by the ordinary professional hand-liner. He used what is called the "sid-strap" tackle. The line ended in a boat-shaped lead, to which were attached two lengths of gimp, each fitted with a swivel and a number three hook.

"Let your line out till the lead touches the bottom," he told Dick. "When you feel two or three sharp little jerks give a good pull and haul up at once."

Before Roddy had finished baiting his own line, Dick gave a triumphant shout.

"I've got one!"

"Quick, yank him in, then."

Dick wasted no time, and a few seconds later he brought over the side a short, thick fish, gaudily tinted in scarlet and deep blue.

"That's not a whiting," said Dick, as he eyed his capture with some surprise.

"No, it's a wrasse, or rock fish," replied Roddy. "They live down at the bottom, and never come to the top. Look at its air bladder, all swollen out. That's because of the difference in pressure."

"Is he any use?"

"Not much. But try a little farther astern. The whiting'll be on the ridge of the reef. Ha, I've got one!"

Up it came, kicking and struggling, a nice fish, rather over a pound in weight, and at the next try Roddy hooked two at once. But Dick could not get one at all. He caught another wrasse, and then a quaint-looking, sharp-beaked gar-fish, but not a single whiting.

Roddy explained that this often happens, and that it shows the importance of getting exactly on the proper mark. Presently he lifted the anchor, and let the boat drop down with the tide about twice her own length. Then the fun began in earnest, and both were soon hauling in fish almost as fast as they could bait their hooks, and often two at a time.

Before long the whole of the bottom of the boat was covered with fish, and Roddy was in high feather.

"If they keep on biting like this," he said, "we'll have all of ten bobs' worth by evening."

They were so busy that they lost count of time. Their hands became sore with hauling the lines, and the mussels in the can grew rapidly lower.

Dick got cramped with sitting so long in one position. He stood up to get the kinks out of his legs.

"I say, Roddy," he said suddenly. "It's getting a bit dark, isn't it?"

Roddy looked up, and gave a low whistle.

"Phew, but there's a fog coming on, and the wind's shifting. Dick, we'll have to chuck it, and get back. It's not good enough to be caught out here in a bad fog."

"What a beastly nuisance!" growled Dick. "Just when the fish are going like this."

"It is poor luck, but it can't be helped. Can you get up the anchor while I haul in my line?"

Dick stepped forward and began to pull up the big stone. Just then a small steamer loomed up through the fast-thickening smother. She was heading straight for them.

"Buck up, Dick," cried Roddy, as he sprang to the oars. "There's a steamer close on us."

"Ahoy, there!" he shouted at the top of his voice. "Don't run us down."

The look-out in the steamer's bows saw the boat, and the course of the vessel was changed in plenty of time. But she came ploughing along almost within her own length of the mark, and her bow wave caught the boat just as Dick was lifting the big anchor stone on board.

Dick, having his back to the steamer, did not see the wave, and Roddy's warning cry was just too late. The sudden heave upset Dick's balance, he stumbled backwards, and, catching the backs of his knees against the forward thwart, took a heavy fall.

"Hurt, old chap?" asked Roddy anxiously.

"Got a nasty crack on the funny-bone," answered Dick, rubbing his elbow ruefully; "but it's nothing. I'm quite fit to pull."

"I'll pull," said Roddy. "You sit still a bit."

But Dick insisted on taking an oar, and getting their course by Roddy's little pocket-compass, they began to row back towards the harbour.

Presently Roddy looked back over his shoulder.

"I say, Dick, there's a good deal of water in the boat."

"Just what I was thinking. She must be leaking pretty badly."

"Then she's only just started. She was quite dry when we finished fishing."

"I wonder if I did any damage when I came that cropper. I'm afraid I dropped that anchor stone pretty heavily."

"Did you, by Jove? That would account for it. Wait; I'll get past you and have a look."

He shipped his oars and stepped forward.

Dick heard a dismayed exclamation.

"Is it bad?" he asked anxiously.

"I'm afraid it is, Dick. The stone's knocked a regular hole in her, and the water's coming in like billy-oh!"

"I'm awfully sorry. What's to be done?"

"Plug it as best we can, and pull in for all we're worth. Let's have your handkerchief."

He made the best job of it he could with two handkerchiefs and some old rags which they found in the stern locker. Then they set to work to pull in earnest.

But in a very short time the water was over the bottom boards, and meantime the fog had closed down like a wall. They could see absolutely nothing beyond a radius of some fifty yards.

"Dick, you'll have to bale while I pull," said Roddy. He tried to speak cheerfully, but he was really anxious. The boat was a crazy old thing at best, and it was quite clear that a plank was sprung.

Dick passed his oar over to Roddy, picked up the tin pannikin, and set to work. Roddy, with one eye on the compass, pulled for all he was worth. But the water-logged boat moved heavily, and, in spite of Dick's best efforts, she kept on sinking lower.

"I say, Roddy," said Dick after a bit. "We're in rather a hole, aren't we?"

"'Fraid we are, old chap," replied Roddy quietly. "You can swim a bit, can't you?"

"I've done a couple of hundred yards. That's about all. How far out are we?"

"Can't tell exactly, but all of two miles."

"Any chance of being picked up?" asked Dick, baling hard.

"Plenty, if it wasn't for this wretched fog. As it is, it would be sheer luck if anyone saw us."

"How about trying to pull back to that Doublehead Rock?"

"No use. Even if we could find it, it's covered at high tide. There's nothing for it but to plug along back. If she sinks we must just hang on to her, and keep afloat as long as we can."

Before another ten minutes had passed it was quite plain to both the boys that she was going to sink. The water was up to the thwarts, and every ripple threatened to break over the gunwale. Steaming with perspiration and breathing hard, they both stuck manfully to their work, hoping against hope that something might heave in sight through the dense wall of fog which hung round them like a blanket.

"It's no use, Roddy," said Dick despairingly. "She's going."

The words were hardly out of his mouth before a small wave lapped over the gunwale, and she sank away gently beneath their feet, leaving her crew swimming.

A boat, of course, does not sink like a ship. There is more than enough wood about her to float the small amount of metal used in her construction.

"Hang on to her, Dick," cried Roddy. "Get your arm over her side. I'll go the other side, and balance you. Are you all right?"

"I'm all right," said Dick. "It's not so cold, either."

"No, and luckily it's still early in the afternoon. We ought to be picked up before night."

"Poor luck losing all our fish," said Dick, as he watched their big catch floating away down the tide.

"Never mind. We'll do as well another day," answered Roddy, with a cheerfulness he was far from feeling.

He kept on talking, doing his best to keep up his own and Dick's spirits. But secretly he was very anxious. At present they were drifting towards the shore, but he knew the tide was very near the turn, and then they would be carried out to sea. And with this fog, the chances were all against their being seen.

Time passed. Dick's teeth began to chatter. Roddy himself was chilled to the bone. A feeling of despair began to creep over him. It was horrible to hang on like this, and to feel that it was impossible to do anything to help himself or Dick.

"Roddy," said Dick at last, speaking very quietly. "I'm afraid I can't hang on much longer."

"You must, Dick," said Roddy urgently. "Kick a bit. That'll warm you up. We're bound to sight something before long. The fishing boats will be coming in before night. They'll—"

He broke off sharply with a shout of triumph.

"Hurrah, there's one now! See it?"

"Yes, I see something," answered Dick hoarsely.

"Shout! Shout for all you're worth," said Roddy.

"Ahoy, there, ahoy! Help!" They both shouted at the pitch of their voices.

There was no answer.

"I don't believe it's a boat at all," said Roddy, as the drift of the tide carried them slowly nearer to the dark, formless object which loomed vaguely through the fog. "No, by Jove, I know what it is! A buoy!"

"A buoy!" echoed Dick, deeply disappointed. "That's no use to us."

"It is. It's a gas buoy. It must be the Gannet. My goodness, what a way we've drifted! It's a big thing, with a cage on top. If we can reach it, we'll be all right. We'll be out of the water, anyhow."

"The tide's taking us to it, isn't it?" asked Dick.

Roddy waited a moment before replying.

"No. We shall pass on the outside. Dick, we've got to leave the boat, and swim for it."

"I can't do it, Roddy," groaned Dick.

"Nonsense. I'll tow you. Take an oar, and put it under your arm. Now then."

As he spoke, he let go the boat, swam round, and caught hold of his cousin. Then he struck out hard for the buoy.

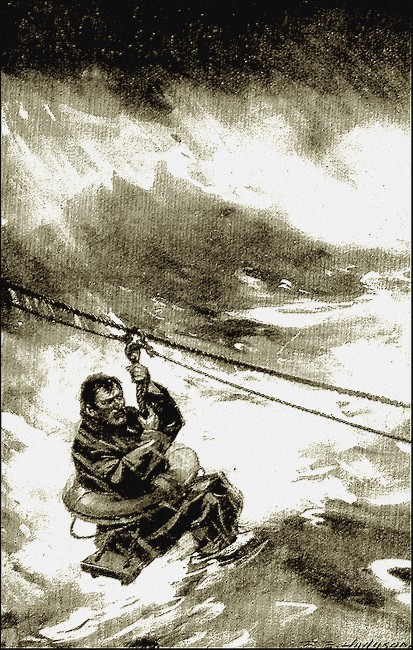

The buoy was only about fifty yards away, but that distance had to be made against the ebb, which was now running strong. Roddy was already numbed with cold, and, though Dick did his best to swim, almost all his weight was on Roddy.

It was the toughest job that Roddy had ever tackled, and if it had not been that both their lives depended on his reaching the buoy, he would never have done it. And even when he did reach it his troubles were not at an end, for there seemed to be absolutely nothing to get hold of.

Swimming round it, he found a ring bolt in the side, and this gave them both something to hang on to while they had time to get their breath back.

Then Roddy managed to climb on to the flat top and get a grip on the iron cage, after which it was comparatively easy to pull Dick up alongside him.

The buoy was what is called a can buoy. It was painted in black and red chequers. On top was an iron cage, and above this rose a pillar, carrying at the top a small gas lamp fed by gas contained within the buoy. On one side of the cage was a plate with the name "GANNET" in big white letters. The buoy was anchored over the end of the Gannet shoal, which lay on the port side of the entrance to Portglask Bay.

"Now then, Dick, off with your things," said Roddy. "Take 'em off and squeeze the water out. Then we've got to do some exercises to get warm."

It was colder than ever, standing there on the chill iron top of the buoy without a stitch on. But a quarter of an hour of arm-swinging, kicking, and deep breathing got their blood running once more, and when they put on their clothes again they both felt considerably better.

But they were fearfully hungry, the fog was as thick as ever, and, to make matters worse, a chilly wind had sprung up, and quite a sea was beginning to run.

The boys judged that it was nearly sunset, when, at last, they caught sight of a dark patch in the smother, some distance to the northwards.

They shouted for all they were worth.

But a thick grey fog blew down, and hid the vessel from their straining eyes.

"It's no use, Roddy," said Dick despondently. "They haven't seen us."

RODDY felt almost desperate. Dusk was falling fast, the breeze was hardening, there was every prospect of a dirty night. He knew very well that, if they two were left to spend the night on the buoy, the chances of their ever seeing daylight again were of the slimmest.

He shouted again with all his might.

Still there was no answer. He had given up hope, when, as if by magic, the fog suddenly broke and lifted, and showed a large trawler beating out close-hauled against the sou'-westerly breeze.

"Shout, Dick—shout for all you're worth," cried Roddy.

Dick needed no urging, and his voice and Roddy's went ringing across the heaving water.

"Hurrah, they've heard us," said Roddy in tones of deepest relief. "Look, they're heaving to."

Sure enough, the trawler's steersman had thrown her head up into the wind, and she lay with sails flapping while her crow lifted a heavy, stumpy-looking boat over the side, and two of them pulled off towards the buoy.

"What in thunder are you kids doing here?" inquired the man who was pulling stroke, a great, fair-haired giant, with a thunderous voice which reminded Roddy of Captain Denny's.

"Went out fishing, and our boat sprang a leak and sank," explained Roddy briefly, as he and Dick tumbled quickly into the boat. "I say, I'm glad you saw us. I thought we were in for a night on that buoy."

"Reckon you wouldn't have stayed there very long," returned the big man, with a glance around. "There's weather brewing, and I'd a sight sooner be aboard the Nelly Gray than hanging on to this here old iron tank."

"Now, then, Barton, aren't ye ever going to start pulling?" asked the other man, who was a narrow-shouldered person with a long, thin face, and a voice as harsh as an ungreased pulley.

"All right, Preece. Don't excite yourself," answered Barton good-naturedly, as he dipped his oar.

His strength matched his size, and the heavy boat fairly hissed through the fast-rising waves. In less than ten minutes from the time they had first been sighted, the boys were climbing aboard the trawler.

Roddy had just time to notice that the Nelly Gray was an oldish boat, but big and very strongly built, and heavily canvassed, when a short, square man, with small, sharp eyes and bristling side-whiskers bore down upon them.

"Now then, hurry up," he said harshly. "Get the boat in. We've wasted enough time already."

He turned on the boys.

"What fool game have you two been playing?" he demanded.

His tone was almost offensive, and Roddy flushed a little, but explained quietly what had happened.

"Lost your boat, eh?" said the skipper. "That comes of boys going fishing as ought to be at school. Well, this isn't no tourist yacht. You lads'll have to work your passage."

"Can't you put us ashore, captain?" asked Dick bluntly.

The question roused the skipper to sudden anger.

"What—turn back and run into Portglask again, and lose the tide?" he shouted. "You're not asking anything, are you? What d'ye think I'm here for—fun?"

"My cousin didn't mean to annoy you," said Roddy, keeping tight hold of his temper. "It's only that he knows our friends will be anxious."

"Then they shouldn't ha' let you go out without your nurse," sneered the other. "It'll serve 'em right if they got a good scare. Go you down to the galley and help the cook with supper."

Roddy saw that Dick was very angry. He took him by the arm.

"Come on, Dick," he said in a low voice. "It's no use butting against that fellow," he explained, as they dropped down the steep little companion ladder into the cuddy. "A skipper's a king at sea, even if he only commands a trawler. This is rough on the governor and the mater, but, after all, it's better than if we were still hanging on to that gas-buoy. We shall probably put in at Milford to-morrow, and then we can send a wire to say we're safe."

In the galley a thin, unhappy-looking man was peeling potatoes. Roddy explained that he and Dick had been sent down to help, and the cook, who had evidently not yet recovered from a spree ashore, seemed glad to let them take the work off his hands.

Roddy, who had knocked about a lot in North Sea trawlers, gave Dick the potatoes to peel, and set to work with the rest of the cooking.

Everything was in a fearful mess. The galley-stove was covered with rust, and of the pots and pans the less said the better.

The first thing Roddy did was to start a regular clean up. The cook, after showing him where the stores were kept, had cleared out.

"Don't fancy the cooking's up to much in this hooker, Dick," said Roddy. "I'll spread myself to-night, and see if I can't give the crew something a cut above the usual."

"You'd better hurry up, then," replied Dick, who was feeling squeamish. "She's moving a lot already. And by the sound of it, the wind's getting up."

"Then we'll try a dry hash," said Roddy, as he put a frying-pan on. "That won't take long. A nigger cook showed me on the old Ida out of Hull. And you step on deck, Dick, and get a breath of air. It's the stuffiness down here that's playing old Harry with you."

Dick, who was looking very pasty-faced, took his advice and went off.

Roddy quickly cut up the potatoes and onions, and put them into the frying-pan with some fat. Then he sliced up a big chunk of salt pork into thin wafers, and mixed it in with the bubbling vegetables. He kept the fire hot and clear, and turned the mass constantly with the blade of a knife.

It was no easy job, for the sea was getting up all the time, and the Nelly Gray was pitching heavily. Overhead, he could hear the wind shrieking in the rigging, while from hoarse shoutings and tramplings he judged that all hands were shortening sail.

Suddenly Dick plunged below again.

"I say, Roddy," he said in a low voice. "Who do you think's aboard this craft?"

His tone made Roddy turn sharply.

"Sam," went on Dick. "Sam—one of those chaps who tackled you and Drake Denny on the barge."

"How do you know? You never saw him."

"No, but I heard him talking to Preece. He told Preece that he'd spotted you, and that he jolly well meant to get even for the trick you played him that night, when you and Drake slipped away from the barge in his boat."

Roddy looked thoughtful.

"That's a bit awkward," he said. "They certainly seem to have a queer gang aboard this hooker. But it's no use worrying. After all, I don't see what he can do to hurt us. There won't be trouble to-night, anyhow. They'll all be much too busy. We're in for some weather, or I'm a Dutchman."

"I should rather think we were. It's blowing like anything, and the waves are beginning to break over the deck already. Seems to me we've got out of one hat into another."

"Don't worry," laughed Roddy, as he stirred the contents of the frying-pan. "These trawlers'll stand pretty near as much as a liner. And by the look of her, the Nelly Gray is well-found and well-handled."

"She's all of that," broke in a deep voice, and big Barton poked his head into the little galley. "So you've took on the cook's job, younker. Mebbe you'll make a better job of it than Taffy did. Anyways, you couldn't do no worse."

"Oh, I've learnt to cook a bit," said Roddy modestly.

"Smells all right," observed Barton genially. "Sing out when grub's ready. The glass is tumbling, and we're in for a dirty night."

"I thought as much," returned Roddy. "Everything will be ready in a few minutes."

Barton still lounged by the door, and Roddy ventured on a question.

"Where are you bound?" he asked. "Bristol Channel?"

Barton hesitated slightly. He gave the boy a quick, half-suspicious glance.

"Aye, them's our usual grounds," he answered gruffly.

"You see," explained Roddy, "my cousin and I are keen to get ashore. Our people will be thinking that something's happened to us."

Barton nodded.

"You needn't worry, my lad. Cap'n Ormston'll put you ashore all right to-morrow. But don't you say I told you so. He's a contrary sort of cuss, and you've only got to say one thing for him to do the opposite."

"I'll be careful," said Roddy. "Grub's ready," he added, as he took the pan off the galley stove.

"Sling it along just as it is," continued Barton. "Dishes aren't no sort of use in this here weather."

Three men were in the tiny cabin. Preece was at the table, the cook was lying huddled up on the locker aft, while the third, sure enough, was Sam. Sam favoured Roddy with a scowl, but made no remark, and Roddy took no notice.

"What's this here?" growled Preece, as Roddy, hanging on with one hand in order to keep his balance, put the pan in front of him.

"Dry hash," explained Roddy.

"Dry hash. I never heard tell of it."

"You don't want to hear of it. Your job is to eat it," remarked Barton. "And if you don't want any just shove it over here."

Preece grumbled, but took a good helping. So did Sam and Barton. The cook still slept.

"First chop, my lad," said Barton, looking up with his mouth full. "You don't seem to find anything wrong with it, Preece."

"It might be worse," grudgingly admitted Preece.

Roddy went back to the galley, and fetched the tea.

"Skipper's at the helm," said Barton. "Take him a mug."

Roddy filled a big enamelled iron mug, and swung himself up through the hatch. He knew it was blowing more than a bit, but he was hardly prepared for the sight that mot his eyes.

The Nelly Gray, close-reefed, was beating out into a sou'-wester which was already more than half a gale. All the fog had been swept away, and the pale twilight showed tall, white-crested combers rolling in out of the open sea in endless serried ranks.

There was no land in sight. The gathering darkness had quite hidden the tall Welsh cliffs. The only sign of life in all the wild expanse was a line of twinkling lights passing swiftly southwards, a big Atlantic liner driving at twenty knots down St. George's Channel.

Just aft of the little hatch stood the skipper, gripping the tiller with both hands. The wind roared past him, the spray pattered, in stinging shoots on his steaming oil-skins, and Roddy noticed that he kept an anxious eye on the leech of his big mainsail.

"Your tea, sir," shouted Roddy. He had to shout, for the shriek of the gale made ordinary speech impossible.

Holding the kicking tiller under one arm, the other took the steaming mug, drained it at one long draught, and pitched it back to Roddy.

"Tell 'em to tumble up," he bellowed. "We've got to shorten sail again."

"Right, sir," answered Roddy, and dropped back down the hatch like a jack-in-the-box.

The men below growled, but obeyed, and with much trouble canvas was shortened afresh, and a storm jib set. With sails like sheets of iron, the Nelly Gray staggered on her course.

The gale grew worse, and Preece was called to help the skipper at the tiller. It was dark now, but fortunately the fog had clean gone, and the night was clear.

The wind was pulling round nor'-westerly, and as the sea increased the motion of the trawler became simply terrific. Now she was swung up on the crest of a great wave, then sent sliding down into a hollow so deep that the wall of water behind cut off the wind, and for the moment all was calm.

Roddy went below again to get some food. He found Dick pluckily struggling against spasms of sea-sickness, and made him some hot tea which did him good.

"Wish I could get on deck," whispered Dick. "That fellow Sam has been staring at me and chuckling to himself as if he had some great joke. They're a queer crowd aboard this craft. Barton's the only decent one of the lot."

"They are queer," answered Roddy cautiously. "And I have my suspicions. But don't worry. Barton says the skipper will certainly put us ashore to-morrow."

"Do you really think he will?"

"If my suspicions are right, I'm certain of it. I believe their game is one that they don't want any witnesses of."

"What is it?"

"Poaching," whispered Roddy.

"Poaching?" repeated Dick. "How can you poach at sea?"

"Trawling in prohibited areas—that's what they call it in the charge sheet. But this is no place to talk of it. Come on deck. It's wet, but better than this stuffiness."

On deck it was blowing harder than ever, and now Barton was helping the skipper at the tiller.

The boys got what shelter they could under lee of the companion, and hung on. It was lighter now, for the moon had risen, and shone through the thin wisps of cloud which scurried across the sky.

"Do you mean to say there are places in the sea where you mayn't fish?" said Dick, his mouth close to Roddy's ear.

"Yes, rather. Lots of 'em. Fishguard Bay, for instance, and from Garland Stone to Skomer Island. You can fish there with hook and line, but you mayn't use trawls. There are fishery protection gunboats to see that boats don't break the law, but there are not enough of 'em, and as the fishing is awfully good in such places, why, you'll always find fellows ready to take the risk."

"What happens if they're caught?"

"Big fine, and all their nets confiscated."

Before Dick could speak again, there came a sharp exclamation from Barton at the tiller close behind them.

"See that, skipper?" he shouted.

"No. What?"

"Another trawler, and by the look of her she's in trouble."

Roddy sprang to his foot.

"He's right, Dick. See—over there."

The Nelly Gray rose on top of a towering wave, and as she poised upon its huge crest both boys saw over the starboard bow a trawler rather smaller than the Nelly Gray. Her mainmast was gone, snapped off about six feet above the deck, and she lay in the trough of the sea with the waves breaking over her.

Looking over the starboard bow, the two boy saw a trawler, her mainmast gone.

"It's the Polly," said Barton. "And in a bad way, too—"

"She's signalling for assistance," broke in Roddy, springing across to the tiller.

"What do you know about signals?" demanded the skipper, staring suspiciously at Roddy.

"Enough to know what's flying at her masthead, sir," answered Roddy. "The letters are N.C., meaning 'In distress; want assistance.'"

"She'll have to wait for someone else to help her, then," growled Captain Ormston. "It's as good as suicide to put a boat overside in this gale."

The words sounded heartless, yet Roddy felt that there was real regret behind them.

"Surely we can do something, sir?" he said.

"Who asked you to speak?" cried Ormston angrily. "Think I don't know my job, and want a kid like you to teach me?"

"No, sir," replied Roddy. "But surely you're not going to run past her, and leave the poor fellows to sink?"

"What else can we do?" retorted Ormston. "Nothing short of a lifeboat could live in this sea. P'r'aps you'd like me to run the Nelly Gray alongside of her, and smash both of us?"

"I know you can't do that, but couldn't you run up to windward and lie to, and let the wind take the boat down to her?"

"Who taught you seamanship?" growled Ormston, glaring savagely at Roddy. Yet all the same there was a new note of respect in his tone. "P'r'aps you and t'other kid 'ud like to take on the job yourselves?"

"I'll go, sir," answered Roddy quietly.

"By thunder, so'll I, skipper," roared big Barton. "I don't let myself be shamed by a nipper like that."

"It's as good as death," said Ormston. "And I'll lose my boat as well as you."

"Maybe you'll be in the same fix yourself one o' these days," answered Barton. "Come on, lad. Rouse 'em up below to help us over with the boat."

He gave a hurricane bellow which rose even above the shriek of the gale, and Sam and Preece and the miserable-looking cook came tumbling up in a hurry.

"You chaps help to get the boat out," ordered Ormston. "There's a craft there in need o' help, and Barton here and the boy are going over to 'em."

As he spoke he forced the helm up, and the Nelly Gray, groaning in every timber, wedged her stout nose closer still into the wind, and took a new list which dipped her lee gunwale level with the black waves.

Dick was caught unawares, and tumbled bodily into the swimming scuppers, but Roddy had hold of him like a flash, and dragged him, bruised and soaked, to his feet again.

"I'm coming, too," declared Dick stoutly.

"No, Dick, it would be no use. You'd only be in the way," said Roddy in low, earnest tones. "Honestly, I mean it."

"But I can't let you go alone," begged Dick, near to tears.

"It's got to be, old chap," replied Roddy. "Don't worry. We'll be all right."

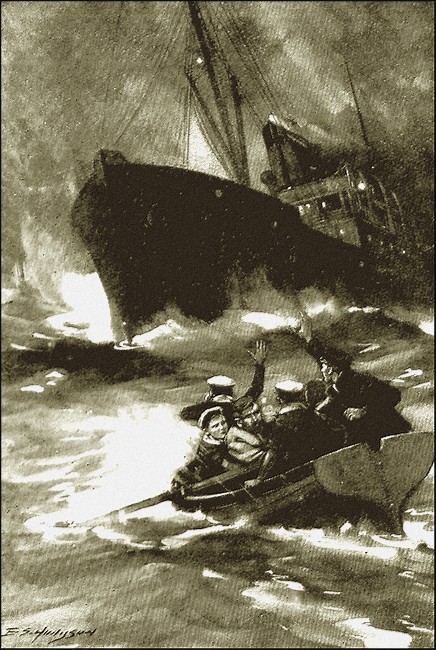

At this moment the clouds blew clear, and the moon shone out brightly over the waste of tossing waters, showing clearly the wrecked Polly and her crew making frantic signs for help to the Nelly Gray.

The latter, by this time, was almost level with her, and gradually clawing up into the weather gauge.

Barton, Preece, Sam, and Roddy were struggling with the boat, and terrible work it was to get her over the bulwarks. They have no davits or lifting tackle on a trawler.

At last they shot her overboard, and big Barton made a plunge and leapt aboard as she sank deep into a black hollow alongside.

She rose again like a cork, and it seemed to Roddy as though she would be smashed to flinders against the Nelly Gray's side. But she was built for rough work, and though she crashed heavily against the side of the trawler, no harm was clone, and, seizing his chance, Roddy followed Barton, and landed safely in the stern of the stout little craft.

Roddy seized the boat-hook, and fended off with all his might as the next wave threatened to grind them to matchwood against the side of the trawler.

The boat was still towing alongside, and threatening to capsize every instant, but Barton let go the painter, and as he did so, he and Roddy both seized their oars.

Next moment they were clear of the Nelly Gray, and racing away before the gale towards the wreck.

If the sea had seemed bad from the deck of the stout trawler, here in the little cockle-shell of a boat it was simply terrifying. They did not seem like waves at all, but rather great, dark hills of rushing water which chased them as though intent upon catching and swamping them.

The two stood facing their work as most deep-sea fishermen do. Indeed, it was necessary, otherwise they could not tell in what direction they were travelling.

Roddy was strong, but never before had he felt so deeply the need for every ounce of strength. For failure to keep the boat's head straight, a single blunder of any kind, could be paid for in one way only—by instant swamping and death.

In spite of the cold wind and the soaking from the flying tops of the breaking waves, great beads of perspiration rolled down his face, and his breath came in panting gasps as he worked his long, heavy oar.

Driven by the wind, the boat fled on towards the Polly.

Time and again it seemed as though nothing could save her from the immense waves, the foaming crests of which glimmered high overhead as they swept up behind her. Yet somehow she escaped, and quickly drew near to the half-wrecked trawler.

Almost before he realised it, Roddy found that they were under the lee of the Polly, which lay like a half-tide rock at the mercy of the pounding waves.

"Catch the rope, lad. I'll keep her up," bellowed big Barton.

A coil of rope, the end of which had been fastened to the stump of the Polly's broken mainmast, came whizzing across the boat. Roddy caught it, and quickly made fast the loose end to a thwart.

At that moment the Polly gave a tremendous roll, and the boat's bow was jerked upwards and forwards. Her stern was drawn down level with the sea, and the top of a wave breaking aboard half filled her.

"Bale! Bale, or she's done for!" roared Barton.

Roddy snatched up a pail and baled like mad, while Barton seized the rope and pulled it in hand over hand.

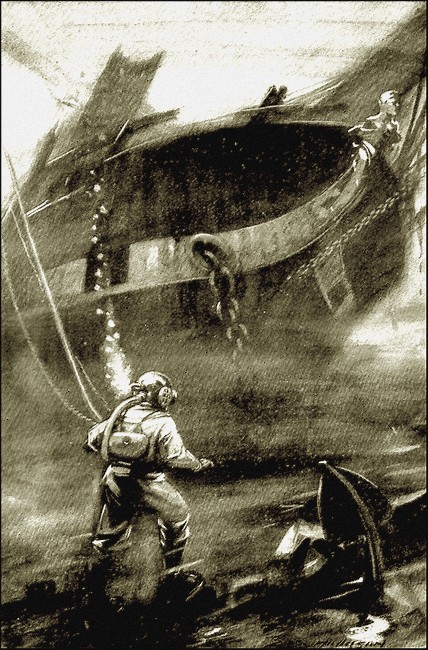

"Look out!" came a yell from one of the Polly's crew. "Fend off, or you'll be stove."

Barton snatched up an oar. He was just too late. Another wave seized the boat and hurled her bodily against the Polly's side.

She struck it with a force that even her stout timbers could not resist. Her side was smashed like an egg.

"Jump—jump!" shouted Barton.

Roddy made a wild leap, and just succeeded in catching hold of the Polly's bulwarks, where he hung until someone aboard seized him and dragged him on to the deck.

Scrambling to his feet, he looked round for Barton, and found him sprawling alongside, still clinging to the rope.

"We've done it now," said the big man as he rose stiffly. "We've done it this time. And 'twas my fault, too."

"SHE'S gone. The boat's sunk," came a despairing voice.

An elderly man with a grizzled beard was clinging to the hatch covering just in front of Roddy. It was he who had dragged the boy on to the deck.

"The boat's sunk, and we'll go, too," he continued in a tone of despair.

"Rouse up there, rouse up!" cried big Barton, pulling himself together. "Never say die till you have to. The Polly's riding high yet; she isn't holed, is she?"

"Not as I knows of," answered the old man. "But what's to do? The mast's gone, our boat's washed overboard, and no craft as ever was built could stand this here pounding. 'Twon't be long afore she bursts apart and founders."

"Why didn't ye try to get her head up to it?" demanded Barton, gasping as the top of a wave caught him, and nearly washed him from his hold. "Man alive, you haven't oven cut away the wreckage yet!"

"There's none to do it, mister, but me and the boy. The skipper and the mate was washed overboard by the sea that took the mast out of her."

"Well, we've got to do something," answered Barton sharply. "We aren't a-going to cling here, and wait for the storm to finish us."

"I'll tell you what," put in Roddy eagerly. "We must rig a sea-anchor, and get her head up to the wind. That'll give us a chance to cut the wreckage away. Then we may be able to get some sort of jury-mast rigged. Come on, Barton."

His confident tone inspired the others, and even the cabin-boy, who had been cowering under the bulwark, revived enough to give a hand.

Barton took command, and all four set fiercely to work.

Desperate work it was, too, for the sea was making a clean breach over the Polly, and every moment it seemed as though she would be rolled right over and turned bottom up. They had to hold on with one hand, and work with the other.

Anything will do for a sea-anchor so long as it will float, and the wreckage provided plenty of material. Roddy, the old man, whose name was Davies, and the boy dragged the stuff to Barton, who lashed it together with odds and ends of rope into a sort of rough triangle.

Getting it overboard was the most perilous job of all, and the boy was as nearly as possible washed over after it. He would have been if Roddy had not seized him just in the nick of time.

The four waited in intense suspense as Barton paid out the riding rope, which was made fast in the bows.

"Hurrah, it holds!" cried Roddy. "She's coming round to it."

So she was. As the rope tightened, the drag of the sea-anchor pulled the Polly round, head to wind.

The relief was amazing. Although the trawler still pitched furiously, the terrific rolling ceased, and the waves no longer broke so savagely over her decks.

"Now for a jury-mast," cried Roddy. "What about the spinnaker boom?"

"Aye, we've got one," said old Davies. "Help me roust it out."

They got the boom up, and then came the job of lashing it to the stump of the broken mast.

With the gale still blowing as hard as ever this was a terrible task, and took the united strength of all four.

Then they had to rig shrouds and a fore-stay, and it was three long hours from the time they had scrambled aboard out of their sinking boat before the work was done and the mast ready for a sail.

Long ago the Nelly Gray had vanished. She had stood by them for nearly half an hour, then her skipper, realising that there was nothing that he could do to help them, had sailed away. Since that they had sighted nothing except the distant lights of a couple of large steamers making their way up Channel.

"Got a spare jib?" asked Roddy of old Davies.

"Aye, we've better than that. There's a mizzen staysail in the locker. If we rig that as a trysail 'twill give her steerage way."

The sail looker, like everything else aboard the battered Polly, was swimming in salt water, but they got the soaked sail out, and managed to hoist it. Small as it was, it steadied her wonderfully, and as her rudder was luckily uninjured, the Polly once more had steerage way. Then at last they were able to cut away the sea-anchor, which had served them so well, and the trawler lay to under her own sail.

"Dawn's breaking," said big Barton hoarsely, as he pointed to a grey streak in the east.

"Praise be for that," answered old Davies, as he clung to the newly rigged shrouds. "Now we'll see where we are."

Slowly the pale light increased, showing up long lines of tall waves, each tipped with a ragged crest of foam, rolling angrily under a lowering sky.

But, strain their eyes as they might, no land was in sight.

Barton turned to the binnacle, but started back with an exclamation of dismay.

"Compass smashed," he said. "And I knows no more where we are than a baby."