RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"Sons of the Air," F. Warne & Co., London & New York, 1929, Book Cover

"Sons of the Air," Title Page

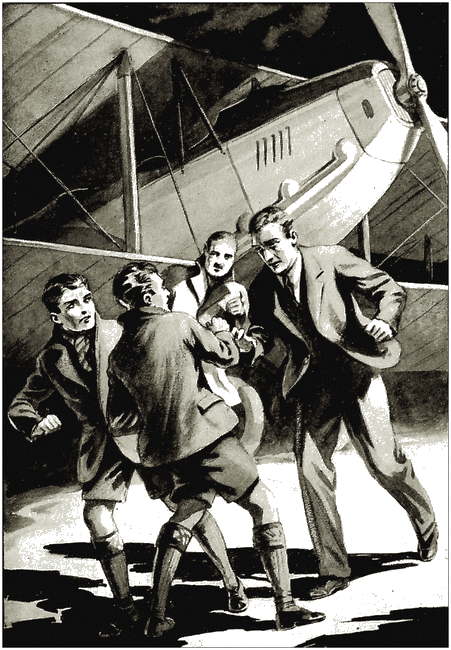

Frontispiece.

Jack found himself swinging like a great pendulum at the end of his rope.

"YES, my little lads, you're doing very nicely," said Curtis Clinton, with a smile on his pleasant sun-burned face, as he gazed down into the clear pool where hundreds of tiny trout darted about. He scattered a little food for the baby fish, then went up to the head of the pool where a tiny spring of ice- cold, crystal-clear water bubbled up from a small crevice in the limestone.

This spring was Curt's most cherished possession, for without it the trout farm which gave him his living could not have existed. There was never a day when he did not inspect it, and it was a fad of his to keep a thermometer in it to see that the temperature did not change. He had never known a change of more than four degrees—from thirty-eight degrees to forty-two. As he lifted the thermometer he noticed a flicker of white in the dark mouth of the spring. Something rose spinning in the rush of the water, and as it came to the surface he picked it out. He could hardly believe his eyes when he found it to be a small fragment of newspaper.

"Of all the rum things!" he gasped, as he turned and, carrying the paper very carefully, took it back to his little bungalow, which stood further down the slope close above his biggest pond. There he laid it flat on a sheet of blotting paper which drew the water from it, and taking this outside pinned it on a board in the strong spring sunlight.

In a very few minutes it had dried sufficiently for the print to become visible, and, getting a magnifying glass from the house, he scanned it eagerly. The first word he made out was Tiedende in large letters, and this he saw was part of the title.

"Dutch!" he exclaimed. "Well, if this doesn't beat cock- fighting. Will some one kindly tell me what a piece of a Dutch newspaper is doing in my spring? And here's the date too, May 3rd. Why, it's only about three weeks old." He frowned thoughtfully. "Well," he said at last, "the whole country is full of underground streams. This paper must have fallen into one of them through a cleft and come through goodness knows how many miles of dark rock pipes until it came out through my spring. But Dutch—why Dutch?"

His musings were sharply interrupted by a hoarse shout.

"Mr. Clinton, them there boys o' yours is up to some new devilment. Flying like kites. You better come an' see."

Curt, bolting round the corner of the house, almost ran into a man hurrying in the opposite direction.

"Flying, Agar!" he exclaimed. "What do you mean?"

Agar, a grizzled old fellow who had a small farm a little way down the valley, grinned till his parchment-like face was a mass of wrinkles.

"It's true, sir. I seed 'em from my place. They got something like a big kite, and one on 'em was right up in the air in it. I'll lay it's that there Jack Milner—him and Kip Carter."

But Curt was gone. Rushing round to the shed, he got out his motor bicycle, sprang into the saddle, kicked off, and the next moment was roaring down the rough road at a perilous pace. Agar watched him.

"Looks to me as if he's as like to break his neck as any on 'em," he observed. "Gosh, but I wouldn't be master o' them there Scouts for something! Young demons, specially that there Jack!"

Old Agar was a little prejudiced, for in point of fact the boys of the Pipit Patrol, of which Curt was Scoutmaster, were as nice a set of lads as any in all that wild countryside. As Curt often said, there was not an ounce of real harm in any of them. The only reason why they sometimes got into trouble was that they were healthy, open-air lads with a craving for adventure and a wild desire to be always trying something new.

"Of course, it's Jack," said Curt to himself, as he sent his machine crackling up the steep slope which ran at right angles from the valley road.

As he reached the top he came into view of the village of Garth lying in a hollow below, and of a great bare fell stretching steeply up to the right. On a ledge high up the hillside three boys were standing holding a fourth who lay spread on a kind of framework beneath a kind of tiny biplane.

"A glider!" gasped Curt. "How in sense did they get hold of a thing like that?"

He pulled up, left his bicycle leaning against the bank, scrambled through the hedge and began to run up the steep with long springy strides. He was still too far away for even his loudest shout to reach the boys, and his only chance of stopping them was to get near enough before Jack took off.

It was no good, for long before he was within hailing distance there came the gust of wind for which the youthful pilot had been waiting. Curt saw him signal with one hand to the others, saw them run forward down the slope holding the glider which tugged like a kite. Then they let go, and Curt's heart was in his mouth as he saw the glider swoop upwards and outwards exactly like a rising kite.

"He'll be killed," he gasped in horror. "He can't possibly know how to control the thing."

Yet somehow the boy pilot did manage to control the machine. He worked his ailerons with surprising skill and kept on a level keel as the glider, with the fresh spring wind under her planes, soared onwards.

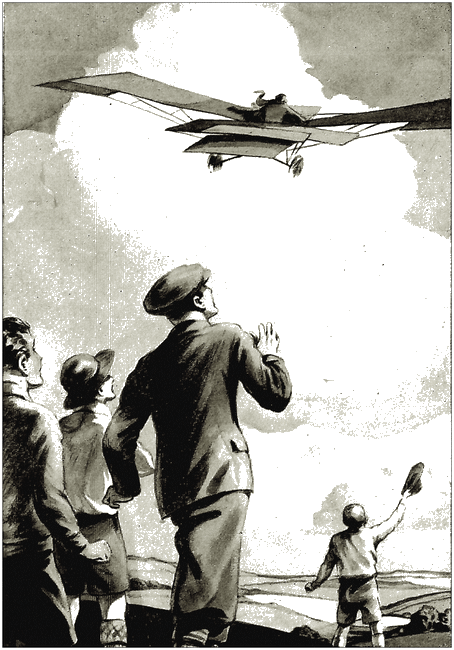

Somehow the boy pilot did manage to control the machine.

A freckled-faced boy with bright blue eyes was the first to hear Curt coming, and turned to meet him.

"Isn't it fine, sir?" he cried, with glowing face. "And Jack's promised that I shall have next turn."

"Next turn, you lunatic! There won't be any next turn. We shall be lucky if we ever see Jack alive again."

Kip Carter's face dropped.

"W-why, what's the matter?" he gasped.

"Matter, Kip! Mean that you don't understand how confoundedly dangerous it is? There are only about a dozen men in England who have ever handled gliders successfully. Jack knows nothing, and if the wind tilts him he's done. He'll come down like a stone."

"I—I never thought of that," said Kip in dismay, but he spoke to empty air, for his Scoutmaster was already plunging down the hill in pursuit of Jack.

"He's in an awful paddy," said Kip to Butter Briggs, a solid- looking youth who was gazing round-eyed at the glider. "We'd better go on after him."

A fresh gust caught the glider and tilted it so sharply that Curt's heart was in his mouth again. But Jack, who seemed to have no sense of fear, got her back on even keel. He was about fifty feet up, hovering in the wind stream like a hawk, and Curt, looking up from below, saw his face shining with delight.

"What an airman he'll make!" was the thought that flashed through his mind. "My word, what an airman!" Then he stopped. "Jack!" he shouted. "Can you hear me?"

"Fine, sir," replied Jack.

"I wish you'd come down, Jack. We've got to go to Fandle this afternoon. Can you manage it?"

"I think so, sir."

"You'll have to be careful," said Curt, speaking in quiet, distinct tones. "The wind is gusty, and it won't do for you to side-slip. Keep her head a little down and head for the leasowe."

"Prickly sort of place to come down, sir," grinned Jack, but he did as he was bid.

The leasowe was a rough field further down the slope, covered with clumps of brier and blackberry bushes. It was exactly because these were there to break a possible fall that Curt had ordered Jack to make for the spot. He knew that otherwise there was nothing for the boy to do but fly right across the valley. Then when he got to the dead area where the wind was cut off by the opposite hill he would drop like a stone. It was impossible to come back to the starting point, for a glider depends entirely for its flying power on the wind striking upwards on the cambered surfaces of its planes, and the moment it turns with the wind it is bound to fall.

Curt was in an agony as he followed just below the tossing, quivering glider. He was not the sort ever to make favourites among his boys, but now he had to acknowledge to himself that red-haired, cheeky, cheery Jack Milner was the one of them all whom he could least easily spare. It seemed to him too that he was the one whom his country could least spare, for a boy like Jack would make a splendid man.

A sharp puff caught the glider and lifted her several yards, and for a moment it seemed as if she were clean out of control. Beads of cold sweat started on Curt's forehead as he waited for what seemed the inevitable crash. But again Jack cleverly got control, and again he forced her nose down.

"Got a bit of a bump that time, sir," he called cheerily. "But the wind's all right now, and I'm doing fine."

"Keep down," begged Curt. "If you go too far you'll get into calm air and stall."

"All right," Jack answered. "Coming down now, sir."

Down he came as easily and smoothly as any old hand.

"The boy's a marvel," said Curt to himself, and the words were hardly out of his mouth before the crash came.

The breeze at this lower level seemed to fail completely, the glider stalled, her nose came up, then she turned right over and dropped—dropped straight into the centre of one of those clumps of bramble on the near edge of the leasowe.

Curt felt sick as he heard the crash of the crumpling framework, and he ran madly towards the spot.

As he reached it Jack came crawling out from among the ruins. A large bleeding scratch ran all down one cheek, but that was not what was making his lips quiver.

"Oh, sir, I've broken it badly!" he cried in despair.

"Broken it, you lunatic!" answered Curt. "What does that matter if you haven't broken yourself? Don't you understand that you've had about as narrow an escape from death as any chap ever had?"

Jack's eyes grew round as billiard balls as he looked at Curt.

"I—I didn't know that, sir," he stammered. "I hadn't thought—"

"I don't suppose it would have mattered if you had known it," returned the Scoutmaster; "but don't do it again, Jack. You've taken ten years off my life in these last ten minutes."

"I'm awfully sorry, sir," said Jack, and Curt saw that he meant it.

At this moment the hoarse hoot of a klaxon came echoing across the hillside from the distant road. All Jack's gloom vanished.

"It's Mr. Trask, sir. He's come to take us to Fandle. Isn't it jolly good of him?"

DICKY TRASK lay back in the deep driving seat of his great car.

"Hullo, you chaps!" he said in his odd squeaky voice. "Thought I'd drop round and run you up. It's the dooce and all of a walk over the fell."

"It's uncommon good of you, Dicky," said Curt. "Jack, you come in front with me; the rest of you pile in behind. And mind the paint, or Mr. Trask will never give you a lift again."

They all piled in, and Dicky sent the big car rolling noiselessly up the long slope.

"What the dickens were you chaps doing?" enquired Dicky, glancing round lazily. "Looked to me as if you'd got some sort of a big kite up, but I was too far off to see what happened except that it came down."

Curt told him of Jack's exploit, and Dicky whistled softly.

"Great snakes, Curt, but you do keep a menagerie! Jack, ain't you ashamed of scaring the hair off your kind teacher?"

"I didn't think of it that way, sir," replied Jack seriously.

Dicky glanced at the boy.

"Make a proper old bus driver, wouldn't he, Curt?" he observed thoughtfully, and after that devoted his attention to driving the car at a very high rate of speed along the rough and narrow hill road.

It was not the Pipit's first visit to Fandle Fell Aerodrome, for owing to the kindness of Dicky Trask, who was by far the richest and therefore in a sense the most important member of the Flying Club, they had a sort of general invitation to be present at Meets, where they made themselves useful, and in return got a good deal of useful teaching from the mechanics and an occasional flip from a member. All of them, but more particularly Jack Milner and Kip Carter, were mad on flying, and not one, except, perhaps, Butter Briggs, but would make a good pilot. Butter was just as keen as the rest, but he was a bit slow in the uptake. That was the only thing against him.

"Topping afternoon, eh?" remarked Dicky, as he pulled up by the big shed. "Ought to be quite good topside. Want a flip, Jack?"

Jack Milner's eyes glowed with delight. "Oh, thank you, sir!" he cried.

"All right. I'll be ready in two shakes," replied Dicky.

He stepped leisurely out of his car and walked slowly over to the little Club House.

"You lucky brute!" growled Kip Carter, digging Jack in the ribs with his elbow. "You've had one go already to-day."

"You shall have the flip, if you like, Kip," said Jack, who was the most generous soul alive. "I mean it, Kip."

Kip's freckled face flushed a little.

"Rot! You go of course. Perhaps some one else will take me up."

Dicky's idea of "two shakes" ran to something more like ten minutes before he came out in pilot's cap and goggles thrust up over his eyes, and walked slowly across to his plane which his mechanic, Joe Worthy, was warming up for him. She was a lean and shapely Moth with a bright yellow body and silver wings. She had two seats set tandem fashion in two separate cockpits, and was fitted with dual control. Dicky found this convenient because on a long flight he could hand over to Joe whenever he felt like it.

He panted a little as he hoisted himself up on to the lower wing and flung his leg over into the after cockpit.

"You're getting much too fat, Dicky," said Curt reproachfully. "You ought to take up golf or something energetic."

"Don't you call flying energetic?" retorted Dicky. "Come on, Jack."

Jack slipped into his place like an eel and snuggled down comfortably. At once the engine accelerated to a roar, the little plane rolled off over the hard ground, and within fifty yards was in the air.

"Like it, Jack?" asked Dicky through the 'phone.

"It—it's almost too jolly, sir," stammered Jack. "It—it makes you feel like an eagle must feel."

"Swooping," chuckled Dicky, as he cut out and let the machine sweep into a deep volplane. Then up again to corkscrew in circles to a height of a thousand feet. He gave the boy a good twenty minutes, came down, then, seeing the longing look in Kip's blue eyes, took him for a short spin. "And now we'll have tea," he said.

The big car never travelled without an elaborate tea basket, and Joe already had the kettle boiling. All six, the two men and four boys, stretched themselves on the turf and drank tea from white enamel cups and ate most delicious sandwiches and large pieces of rich cake. Meanwhile they watched two other planes stunting over the ground.

"I say, Dicky," said Curt presently, "a rum thing happened to- day."

"You have all the luck," returned Dicky. "Nothing rum ever happens to me. But get on with it."

Curt told him about the piece of newspaper which had bubbled up out of the spring.

"And it was a bit of a Dutch paper," he ended.

"Gosh! You're not suggesting that your spring started in Holland and came all the way under the North Sea?" said Dicky.

"No, you duffer. The paper must have been dropped into some pot hole up on the Fells."

Dicky grinned. "If the War was still on we'd have to start the Patrol hunting for German spies," he chuckled. "As it is—..."

"I found a Dutch paper at home, sir," put in Jack Milner suddenly.

Every one looked at Jack, and there was an awkward silence. Jack seemed to sense something wrong, and a puzzled look crossed his face. Curt spoke quickly.

"You did not notice the date, I suppose, Jack?"

"No, sir, but I'll find out if you want to know."

"It doesn't really matter," said Curt quickly, and changed the subject.

The sun was getting low, the other planes were down and back in the hangar, the wide field lay quiet in the evening sunlight, and the tall firs opposite flung long black shadows across it. Dicky sat up.

"Time to be shifting," he said. "Curt, come and spend the night at my place."

"Nothing doing," said Curt. "Got my fishlings to feed."

"Can't that old blighter, Agar, do it?"

"He could, but he won't know."

"He'll know all right. See here! Joe shall take these kids home and go round and tell Agar to give worms to your trout. You and I will fly back to Scarth."

Curt hesitated. He was fond of Dicky, and it was a pleasant change to eat a meal he had not cooked himself.

"Don't think up any more objections," said Dicky, with a grin. "You're coming, and that's flat."

Curt smiled. "All right. If you're going to make up my mind for me, I've nothing more to say."

Dicky called up Joe and gave him his instructions, which Joe received with a perfectly wooden face. All he said was:

"You better go on at once, sir. Looks to me like there might be wind up above afore long."

"Your name ought to be Jonah, not Joe," retorted Dicky. "Come on, Curt. Is there plenty of petrol, Joe?"

"She were filled this afternoon, sir. I put in fourteen gallon. You ought to have enough to take her to London, let alone to Scarth."

Dicky waddled over to the plane, and Curt following thought, not for the first time, that his friend was getting far too fat. Dicky Trask was now little more than thirty, but he weighed nearly fourteen stone, and he was only five foot seven. As every one knew, he had done excellent work in the War, where he had gained fame and an M.C. as a member of "Cottrell's Circus," but after that he had come in for his big place and a pot of money, and now the only things he seemed to care for were flying and motoring.

"Too much money," said Curt to himself with a sigh, as he climbed into the front seat of the Moth and adjusted the tube of his telephone. "And such a good chap, too. If I could only get him interested in something. He'd make a splendid Scoutmaster. Why, the boys all adore him. And if he goes on like this he'll simply go to seed and die of fatty degeneration of the heart or something horrid like that. He gets all blue in the face as it is."

"Are you all right, Curt?" came Dicky's voice.

"Snug and comfy, thanks," Curt answered, and then the engine's note deepened, and the long, light machine sped away and soared into the air.

A Moth climbs quickly, and within a very few moments they had reached a height of five hundred feet above the aerodrome; then Dicky headed for Scarth, which lay twenty miles away by road but only fifteen as a plane flies across the hills.

"Topping evening, ain't it?" said Dicky, and "Topping," Curt agreed, with his lips against the mouthpiece of the 'phone.

"I'm going to quirk her up a bit," said Dicky. "Get a mouthful of real cool air, eh, Curt?"

"Right you are, but what about that wind current Joe talked of?"

"Joe ought to have been born a raven," chuckled Dicky. "Time enough to come down when we meet it."

Watching the altimeter (the height meter) in front of him, Curt saw that Dicky was indeed driving upwards. Seven hundred, eight hundred, nine, and then they were past the twelve hundred mark and still rising. Even so, they were not yet above the big hills to the west, but Dicky kept on creeping up, and every moment the air grew cooler.

"Enough, Dicky," said Curt. "Kindly remember I've got no overcoat."

"Right you are, old son! I say, look down. Ain't it topping?"

Curt looked down. The tiny machine was so high above earth that, although her propeller was turning over at seventeen hundred revolutions and she was doing just on seventy miles an hour, she seemed to be floating in the blue immensity. Beneath, the fields were dwarfed to chessboard squares and the houses to the size of toys. A long way off a small black beetle crept down a brown riband. It was Dicky's big car taking her passengers home at forty miles an hour. Away to the east the North Sea lay like a purple bar along the horizon with here and there a trail of smutty smoke showing the progress of some coastwise steamer. The air was wonderfully still, and the Moth travelled on level keel with never a bump or swerve.

Then as he still gazed Curt became aware that the Moth was not the only machine in the air. Another plane was coming in from the direction of the sea, but at such a height that she was almost hidden by the clouds that swam above the three thousand foot level. Curt took a pair of glasses from a pocket and focused them on the stranger.

"What is she?" came Dicky's voice from behind.

"Biggish bus. Too far off to make much of her, but she's coming lower."

"Rum game flying in that direction," observed Dicky in a slightly puzzled tone. "Looks as if she must have come across from the Continent, doesn't it?"

"That's about the size of it," agreed Curt. "See here, Dicky. Keep on your present course, but rise a bit higher as if you were going to cross Tall Fell. That ought to bring us right under her when she turns."

"All right, old son, but what makes you so keen about her?"

Curt hesitated. "I am keen," he admitted. "I've a notion that I've seen her before, and a still bigger notion that there's something funny about her."

Dicky chuckled. "Then this is where we start investigating. What ho! Sleuths of the Air! Sounds all right, doesn't it?"

THE strange plane was dropping. Curt saw her fade to a shadow as she dipped through the film of soft cirrus, then reappeared beneath the clouds. The rays of the low sun struck full upon her, and Curt was able to see that she was a powerful machine many sizes larger than the Moth, but of a make quite unfamiliar to him. Her paint work was dirty, her planes were patched, and her whole appearance was shabby, but by her speed there was evidently nothing wrong with her engine.

"Make anything of her?" asked Dicky.

"Yes," replied Curt. "I've seen her before. She came over my place one morning a month ago at dawn. I remember how puzzled I was, for I could see she had nothing to do with Fandle Fell, and there isn't another aerodrome for miles. She was very high up, and I only spotted her through a gap in the clouds. But I noticed that patched wing, and another thing that struck me was the queer high-pitched note of her engine. Since then I have twice heard that engine, but both times at night."

"The plot thickens," chuckled Dicky. "I wouldn't wonder if it was some gent doing a bit of smuggling, Curt. A pal of mine in the Customs tells me they're doing down the Revenue to the tune of something like two millions a year."

"I've heard that, too. And, come to think of it, this is mighty good country for that game. There's not a coastguard station from Blix Bay to Horn Point."

"All right from that point of view," replied Dicky, "but awkward for landing. There ain't a hundred square yards of level ground anywhere between this and my place."

"That's true," said Curt in a puzzled tone, and again he focused his glasses on the strange plane. "They've spotted us, I fancy," he said presently. "They're moving like smoke."

"Think they can get away from us, eh?" laughed Dicky. "I'll show 'em something."

The roar of the Moth's engine rose a note, and the slim little machine shot forward more swiftly. The pointer on the air-speed dial advanced to ninety and quivered between that and a hundred.

"No use doing that, Dicky," remonstrated Curt. "She's got at least double our power, and she's dropping while we're still climbing. Besides, what's the use? We're not Revenue officers."

"But it's such a joke, putting the wind up them," declared Dicky.

"You're putting the wind up me, Dicky. I'm most poisonously cold."

"All right! I'm a bit chilly myself. I only want to spot where they're going, and then, hey for home and dinner!"

"You'd better turn at once," said Curt earnestly. "I mean it, Dicky."

"Why? What's the trouble? You were keen enough just now."

"I know, and now I'm not. I've got it in my head that the people in that bus wouldn't think twice of scuppering you and me if they thought we were spying on them. No, I'm not scared, but does it strike you that in this little Moth we're about as helpless as a lark under a sparrow hawk?"

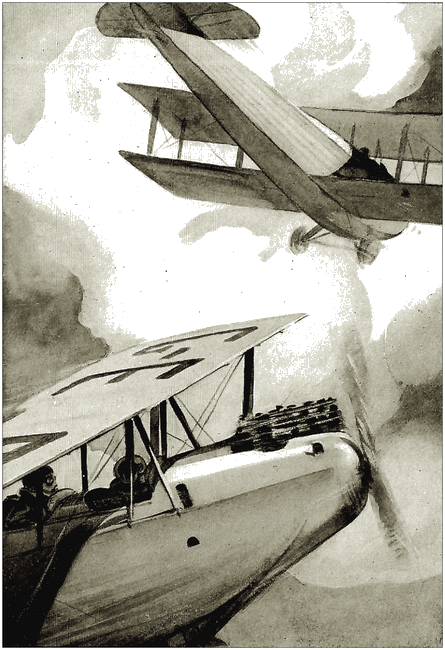

As Curt spoke the bigger plane was almost exactly above them and swooping towards the huge dark ridge of Tall Fell which lay about three miles to the north-west. As Curt peered up he suddenly saw something drop from her.

"Bank, Dicky! Bank!" he yelled, and Dicky flung the little plane over to the left so suddenly that for a moment she lay almost at right angles to the ground, and Curt felt her side-slip in sickening fashion. At the same instant a dark object whizzed past with the speed of a bullet, missing the Moth by barely her own length, and shot out of sight into the tangle of wild hills far below.

"Gosh!" exclaimed Dicky in a tone half of dismay, half of glee. "The beggars tried to bomb us."

"It looked a bit like it," agreed Curt grimly, "but I think it was only meant as a warning."

"Warning or not, I'm jolly well going to follow 'em," said Dicky in such a very different tone that Curt knew it was no use arguing. His only comfort was he was quite certain that the strange plane was travelling far too fast for the Moth to catch her.

In this he was right, for the other plane was moving at something like one hundred and fifty miles an hour, and in less than sixty seconds had streaked across the top of Tall Fell and was lost to sight behind that great mountain mass. Dicky was not more than two minutes behind, yet when the Moth had crossed the bare rock ridge there was no sign of the chase. The air was empty except for a few homeward-bound rooks. The plane had simply vanished.

"Well, I'll be jiggered!" gasped Dicky. "I say, Curt, did we dream the whole blooming business?"

"Not much dream about it," retorted Curt.

"Then she must have crashed," said Dicky, with decision. "It's a certainty no plane could have landed in that muddle of rocks and ravines." He paused. "I'll just cruise round a bit and see if I can spot her remains."

He brought the Moth back to her normal speed and quartered to and fro above the valley. "A muddle of rocks," Dicky had called it, and Curt, looking down, thought the description even less than the truth, for a wilder spot did not exist in all the north country. The desolate hillsides were cut and scarred with deep ravines, and huge boulders fallen from the heights above lay everywhere. The only inhabitants of the desolation were a few sheep looking like white dots as they grazed on the hillsides. There was not a house, not even a shepherd's hut, within many miles.

"See anything?" said Dicky at last.

"Not a sign," replied Curt.

"It's rum, Curt," said Dicky in an unusually solemn tone; "beastly rum. I don't like it. I don't mind telling you, old man, that it's shaken me up a whole lot."

"There's some explanation, of course," said Curt. "And sooner or later we'll find it. But it's getting late, and clouds are gathering over the sunset. Let's push on for your place."

There was no answer, and Curt wondered a little, for Dicky was always ready to talk. The plane flew on steadily, but she was heading north-west and Scarth lay a good many miles to the south- west.

"You're off your course, Dicky," said Curt. "Pull her round."

Still no answer, and Curt, raising himself from his deep seat, turned round to see what was the matter. He saw Dicky lying back in his seat with his eyes closed. His face had a nasty leaden look.

"Dicky!" cried Curt. "Dicky! Wake up!"

Dicky did not stir, and Curt saw that he was in some sort of fit and quite unconscious. Curt Clinton was a young man, strong and healthy, and he had at least his full share of natural pluck, yet as he realised the state of things drops of chill sweat stood out on his forehead, and there was a cold sinking sensation at the pit of his stomach.

It was impossible for him to reach Dicky or do anything for him, for the two cockpits of a Moth are completely separated, and there is only just room for one person in each. Dicky might be dying for all he knew, and in any case he was in urgent need of a doctor. But the awful part of it was that Curt himself had never before piloted a plane single-handed, and now the whole responsibility of getting the Moth to Scarth and of landing there in safety was on his shoulders.

The plane flew on steadily, and Curt saw that Dicky had set the tail trim. He might have done that some time before so that he could take his hands off the joy stick, or he might have done it at the moment he felt himself taken ill. So long as it remained set the plane would go on flying. She would fly until the last of her petrol was gone; then—well, then she would slide down into whatever was below—probably the sea—and— Curt shook himself.

"Steady, you ass!" he said to himself. "You know what to do. Now it's up to you to do it."

He got back into his seat, took hold of the joy stick, and very quietly and cautiously moved it over to the right.

THE little plane came round sweetly and flew on even keel in a south-westerly direction. She was fitted with a full set of instruments in both cockpits, and glancing at the altimeter Curt saw that it registered 2,400. Up at this height it was very chilly, and Curt decided that the sooner he came down a little the better, but thought it would be well to wait until he was clear of the rocky heights of Tall Fell. The Moth was still travelling all out, and he ventured to push back the throttle a very little. He got her back to seventy, which was about her normal cruising speed, and carried on.

In a very few minutes he found himself over the western slope of the hills and saw before him a great range of rolling country with the Irish Sea faintly visible on the horizon. So far so good, but he saw something else which was not so pleasant. The line of dark cloud which he had noticed earlier was rising fast and had already hidden the low sun. The bad weather which Joe Worthy had prophesied was working up fast, and again Curt felt that nasty chill of fear as he wondered what would happen if the gale caught him before he could land.

He drew a long breath and steadied himself. After all, he could not be many miles from Farndon, and at the pace the Moth was travelling he ought to be over it in ten or twelve minutes. The next thing was to make out exactly where it lay, and he leaned over the edge of the cockpit to get a sight of it.

Like all Scoutmasters, Curt had taken a course of map reading, but he had not realised how entirely different everything looks from the air, and he got another nasty shock when he found that he could not tell where he was. He looked about for landmarks and spotted the branch line of the L.M.S. railway running to Witherleigh. Farndon was only four miles from the station of Witherleigh, so that gave him a guide of sorts, and he decided to make for the railway, then turn and fly along it.

Now that he was over the western rim of the hills he could safely come down a bit, so he pushed the control stick over. He pushed it a trifle too far, with the result that the Moth put her head down and the wind whistled in her wires while her speed leaped to over ninety. In panic he pulled it back, and the Moth, responding like a thoroughbred, leaped steeply skywards again.

"Hang it all!" growled Curt. "Any one would think she was alive. But it's my own fault."

He tried again and this time with better success, and the little plane lost height more steadily. At a thousand feet Curt levelled her out and found himself almost above the railway. A train looking no bigger than a toy crawled beneath, headed for Witherleigh. Curt turned in the same direction, but although his speed indicator hovered between sixty and seventy he found that he was moving very little faster than the train.

For a while this puzzled him, for he knew that the train was not doing much more than thirty, but presently he got wise to the reason. The wind had reached him already, and was blowing between thirty and forty miles an hour, so that, although his airspeed indicator was nearly seventy, his speed over the ground was only about half that.

"Nice sort of gale to land in!" he muttered uneasily.

He glanced back over his shoulder at poor Dicky and saw that he was still lying back with his eyes closed and quite unconscious. His lips tightened.

"I've jolly well got to get him home whatever happens," he said, and pushed the throttle almost wide open.

At once he found himself driving ahead of the train, and in less than five minutes saw the little town of Witherleigh below him. He had not much difficulty in spotting the road leading to Farndon, and he turned the plane so as to keep above it. This brought the plane broadside on to the wind, and at once he found himself being blown away to the east. He had to keep his rudder right over so as to counteract the drive of the wind.

The gale was getting stronger every minute. He could tell that by the drift of the smoke from the chimneys beneath, and the way in which the trees were bending. Every now and then the plane bumped like a car taking the arch of a bridge. He was feeling more confident about handling the plane in the air, but the idea of landing terrified him. He tried to remember all he had been told, all that Dicky had done at other times when they had been up together. And then he caught sight of the grey slate roof of Dicky's house and headed straight towards it.

The landing field was at the back of the house with a belt of trees between it and the gardens. He was almost on it before he realized how close it was, and he shut off his engine in a hurry and started planing down into the wind. All of a sudden he found he was much too high and was driving right into the trees on the far side of the field. In panic he switched on again and circled back.

The wind was stronger than ever, and the moment the plane came broadside to it she was driven away from the field. Curt's jaw hardened. He was not going to be beaten, and this time he brought her round in a wide curve, at the same time coming lower. Clouds now covered the sky, and already big drops of rain were hitting the plane with the force of bullets, but Curt carried on steadily and found himself over the north-east corner of the field and about two hundred feet up.

"Now or never!" he said aloud and shut off.

The little plane quivered as she drove down into the teeth of the blast, but she kept wonderfully steady. The ground seemed to shoot up to meet her, and as he watched it Curt's heart was in his mouth. He pulled over the stick just the least trifle, and the angle became less steep. Then almost before he knew it there was a bump, a jump, a second bump, and the Moth's wheels were running over the hard turf.

"My word, Mr. Richard, but you did that fine!" It was Joe Worthy running up to the plane. Then Joe stopped short, and his eyes grew round as marbles. "Why, whatever's the matter with Mr. Richard?"

"He was taken bad when we were up over Tall Fell," said Curt hoarsely. "The sooner we get him to bed the better."

"T-then who brought the plane in?" demanded Joe.

GRIZZLE-HAIRED Dr. Burton came into the dining room where Curt was just finishing the nice little dinner which had been made ready for him, and Curt jumped up.

"How is he, Doctor?" he asked anxiously.

"Better than he deserves," replied the Doctor dryly. "But don't tell him so, Clinton. We've got our chance now, and I've been putting the wind up him pretty thoroughly."

Curt nodded. "I see what you mean, Doctor."

"I thought you would, my boy," answered the other. "You know as well as I that Trask has been neglecting his health most shockingly for years past. I've talked to him again and again, but he only grins in that don't-care-a-curse fashion of his, and tells me not to croak. Now he's had just the sort of seizure I expected, but luckily not as severe as it might have been. I'm going to keep him in bed on strict diet for a week, and after that he's got to get at least two stone off in the next couple of months. I've told him that if he doesn't he'll finish up in less than a year." He chuckled. "Of course, this is utterly unprofessional, and I've no business to talk like this, but, you see, I'm depending on you, Clinton, to help me out—sort of taking you into partnership. You're fond of Trask, I know."

"I should rather think I was," declared Curt. "Dicky's got a heart of gold, Doctor. I've tried just as hard as you to pull him round. I'll go the limit to help you."

"Good man!" said the other, smiling. "And you are a good man, Clinton. If you were not, you would never have got that plane down as you did. You needn't blush, for I know what I'm talking about. I've been up in bad weather myself during the War." He got up. "I must be pushing home. Trask's asleep, so leave him alone to-night. But to-morrow you can talk to him. And mind you talk straight," he added, with a chuckle, as he shook hands and went off.

Dicky seemed almost himself the next morning when Curt went into his room, but he was making wry faces over the tea, dry toast and fruit which was on the tray at his bedside.

"No bacon and eggs, no butter, no marmalade!" he growled. "Hang it all, Curt, you and old Burton are going to starve me to death!"

"Starve you to life, you mean," retorted Curt.

"You'd better remember, Dicky, that you had a pretty close call yesterday evening."

Dicky looked at his friend, and there was an expression in his eyes which Curt had never seen.

"I know that, old chap," he answered gravely. "A close call in more ways than one. What I want to know is how you managed to bring the plane down as you did in the teeth of that gale."

Curt laughed. "I don't know, Dicky," he confessed. "I was scared stiff."

"I should think you were. I know how scared I was the first time I had to land alone. And that was in fine weather and after a good many hours of flying with a pilot." He stopped, then went on again. "Curt, old man, I want to do something for you. No, don't interrupt. I'm not going to insult you by offering you a present. But you'd take one for your Patrol, wouldn't you?"

"I'm a hog as far as my Patrol is concerned, Dicky. I'd take a present for them all right."

"Will you take the Moth, then?"

Curt's eyes widened, and he stared silently at Dicky.

"I mean it, Curt. I know how keen you are about teaching those kids to fly, and there are one or two of 'em who will make top- hole pilots."

"Jack Milner, you mean."

"That's one, and young Carter's another. All right, Curt; then they shall have the little bus, or rather I'll make it over to you for them. And I'll pay the exes, and Joe shall act as instructor until you can take on the job. That suit you?"

"Dicky, it's awfully good of you," replied Curt earnestly. "But it's too much."

"Rats! I'm a rich man, Curt, and have no one to spend my money on except myself. It'll make me feel a little less of a selfish pig if I do something for those lads. Now that's all fixed, and I've got something else to talk about. What became of that plane with the patched wing?"

Curt shook his head. "Haven't a notion, Dicky. She seemed to vanish into thin air. And after you fainted I never gave her another thought. I was too busy."

"I should think you were," replied Dicky gravely. "It was a rum business though, and gave me a bit of a shock. She must have crashed."

"Surely we'd have seen something of her remains if she had," said Curt. "Dropping on those rocks, she'd surely have taken fire."

"Seems likely," agreed Dicky. "One thing's certain. She couldn't have landed down in that cleft, and I'm pretty sure she couldn't have got over the opposite ridge before we sighted her. Tell you what. As soon as I'm fit we must go and make a search."

"Right you are! Only we'll have to go afoot, Dicky."

"I know you and Burton are planning to finish me," groaned Dicky.

But Curt only laughed. "It'll do you piles of good," he answered. "I'll lay you won't know yourself before we've finished with you. And now I must go, Dicky. I've got my troutlets to see to."

"All right. Joe shall drive you home. And see here, you'd better try to find a field somewhere round your place for an aerodrome, and then we'll see about a hangar. So long, old man!"

The big car whirled Curt home in half an hour, and he set to his day's work in the highest spirits. It seemed almost too good to be true that the Patrol was to have a plane of its own. At dinnertime the sandy-haired Kip Carter came to look at the trout. Kip was mad on fish and fishing, and would give up his whole dinner-time to run over to Curt's place and have a look round. Curt gave him orders to collect the whole Patrol that evening.

"We meet in the Hut at seven," he said. "Tell them it's very special."

"What's it about, sir?" asked Kip eagerly.

Curt smiled. "You'll hear when the rest do," he said.

But Kip saw at once that there was something up and hurried off in a great state of excitement.

That evening, when Curt reached the Hut, every single member of the Patrol was already there. The place was crowded, and Curt felt a little thrill as he saw a dozen pairs of eager eyes fixed upon him. What Kip had told them he did not know, but any one could see that the whole lot were almost breathless.

"I've a bit of news for you, boys," Curt said quietly. "I know you are all keen about flying, and I am sure you will be pleased to hear that an aeroplane has been presented to the Patrol."

If Curt had expected a wild cheer he was disappointed. No one said a word, but the whole lot stood still as mice gazing at him, and Curt realized that the thing was too big for them, and that they simply could not believe it. Jack Milner was the first to get his breath.

"An aeroplane, sir?" he said in a sort of hoarse whisper. "It—it couldn't be, sir."

Curt smiled. "But it could, and it is. Mr. Trask has given us his Moth. He has done more than that, for he is going to pay the rent of a field for an aerodrome and to lend us Joe Worthy as instructor."

A sort of gasp came from a dozen young throats at once; then Jack found his voice.

"Three cheers for Mr. Trask! With a will, chaps!"

No one would ever have believed that twelve boys could have made such a row. It was heard in the village nearly half a mile away. And when they had shouted themselves hoarse for Dicky, Jack spoke up again.

"And three for Mr. Clinton! I don't know how he got it, but I'm jolly sure he did get it for us."

Curt could not help feeling pleased at the way they took this up. Then they all crowded round, full of questions, and for a good hour they talked of nothing else but the best field for the aerodrome. Most of them were for Martin's Meadow which lay a little way down the dale from the village, but Jack very wisely pointed out that there they would be between two high hills so that the wind would probably be very tricky.

"You are right, Jack," said Curt. "We shall do better if we can get land higher up the dale on the slope where it is more open. I think it will be cheaper, too."

"Yes, but will Farmer Crosby let us have it, sir?" put in Nibby Gale. "He doesn't like aeroplanes. He says they scare his sheep."

"He's silly!" said Kip Carter. "The sheep won't think twice of it after a week."

"That's true enough, Kip," agreed Curt. "I'll go and see him to-morrow. We must get the land and build our hangar before we have the plane. That's one thing sure. And now I'm going home. You walking my way, Jack?"

JACK MILNER lived with his brother Bill at an old farmhouse called Tarnside, which stood above a small tarn further up the glen where Curt had his trout farm. Bill was eight years older than Jack. Both their parents had been dead for some years, and an elderly widow, Mrs. Dent, kept house for them.

The farm was small and the land poor, and good for little except grazing a flock of sheep. People in Garth wondered how Bill Milner carried on, how he kept himself and his brother and paid Mrs. Dent's wages, let alone keeping up the house which was a fine old building. But Bill was not the man that they could ask questions of that sort, so their curiosity was not satisfied.

Jack was in tremendous spirits as he walked with Curt across the fell through the dusk of the May evening.

"Seems too good to be true, sir," he said. "I can't believe that we're really going to have the plane for our own. What made Mr. Trask give it to us?"

"He fainted in the plane when we were over Tall Fell last night, Jack, so he is not going to fly any more at present."

"Fainted in the plane!" repeated Jack. "Then how in the world did you get down, sir?"

"I brought her home, Jack."

Jack stopped short and gazed at his Scoutmaster.

"But you've never flown, sir!" he exclaimed.

"I've handled the controls once or twice," Curt told him.

"But not coming down. And—and in all that wind. Why, it was perfectly wonderful! Ah, now I see why Mr. Trask gave us the plane!"

Curt laughed. "Well, you needn't blab, Jack. And I don't mind telling you that, when I found Mr. Trask was unconscious, I was so frightened I could hardly move."

Jack nodded. "I should jolly well think you were, sir. I'd have been paralysed. But whatever made you go all that way round over Tall Fell?"

"We followed a strange plane that came down from a great height. A fairly big plane and pretty fast. She had a patched wing. The odd thing was that she flew over the top of Tall Fell only just ahead of us, and when we crossed the ridge there simply wasn't a sign of her. Mr. Trask thought she'd crashed, and I believe that is what upset him."

Jack frowned. "I've seen that plane, sir," he said slowly. "At least I've seen one like what you describe. She had a patched wing and looked awfully weather-beaten, but she certainly could move. I spotted her one evening about a month ago just before dark. She was flying due east and very high. Her engine had a queer note, different from any other machine I ever heard."

"That's the one without a doubt. I saw her myself some weeks ago—at least I just caught a glimpse of her between two clouds. But I, too, noticed the odd sound of her engine. It's a funny business, Jack."

"Very funny, sir," said Jack gravely. "But do you think the plane did crash?"

"I don't. I feel sure we should have seen the bits. Besides, as I told Mr. Trask, she'd almost certainly have caught fire. We did not see a thing."

"Rummiest thing I ever heard," said Jack slowly, and then they came to Curt's gate. "Will you come in for a bit, Jack?" Curt asked.

"No, thank you, sir. I've a job of work to do in the garden to-morrow, and that means I must be up early. Good-night, sir."

"A real good lad," said Curt to himself as he went in. He sighed. "Well, if there is anything wrong, it's quite certain he doesn't know anything about it. But I don't trust that long Dutchman."

Jack walked quickly on to Tarnside. Mrs. Dent had already gone to bed, and Bill was not at home. But Bill was so often out late that Jack thought nothing of this. He ate the bread and butter that Mrs. Dent had left out for him, drank a glass of milk and turned in.

Usually the interval between Jack's getting into bed and getting to sleep was about two minutes, but this night he found to his surprise that he could not sleep. His mind was so full of the new plane and of the idea that at last he was really going to learn to fly that he simply could not get off. He lay quite still for a long time with his eyes shut. He tried all the old dodges of counting imaginary sheep and of making his mind quite blank, but it was not a bit of use, so at last he gave it up as a bad job and got out of bed and went across, barefooted, to the dressing table. He meant to find a matchbox, light a candle and read for a while. He had found the box, was just going to strike a match when he stopped short, for a gruff voice said in a very low tone:

"Dat brat, is he asleep, Meelner?"

At once Bill Milner replied:

"Of course he's asleep ages ago. But don't talk of my brother as a brat, Browle, or you and I will fall out."

"I don't mean no harm," returned the other sulkily.

Then Jack heard the house door open softly, and it seemed to him that two people came in. He frowned.

"What's Browle doing here at this time of night?" he muttered angrily. "I'll bet he's up to no good. Wanted to know if I was asleep, eh? Well, I'm not, and I'm precious well going to find out why he wanted me to be asleep."

Jack's bedroom was on the first floor and had two windows, one opening over the front of the house, and the other facing the tarn. They were both wide open, but thin white muslin curtains hung over them. The night was fine and very still, and that was why Jack had heard Browle so plainly.

Jack went to his door, opened it cautiously, and listened, but all he could hear was a faint murmur of voices. Browle and Bill seemed to be discussing something in the sitting-room, but with the door shut. Jack waited so long that he was almost giving up and going back to bed when at last the door below opened and he heard the two men go out into the passage which led right through the house from the front to the back.

They walked very quietly out at the back of the house, and Jack, wondering what was afoot, pulled the curtain a wee bit aside and waited. It was not mere idle curiosity on Jack's part, or any desire to spy on Bill. He was very fond of his big brother, but he had no use for the fellow who called himself Browle, and he had more than a notion that Browle had some hold over Bill. At any rate Browle had been at the house off and on for some months past, and ever since his first arrival Bill had seemed worried and silent.

Though there was no moon the spring night was beautifully clear, and the stars gave Jack light enough to see the two figures move softly down the grassy slope towards the little tarn. They vanished under the bank and were gone for some little time. When they appeared again each was carrying a heavy load. It was much too dark for Jack to see what these loads were, but he could tell they were heavy by the slow pace of the men and the way they stooped under them.

They came in again by the back, and Jack flitted across to his bedroom door which he had left open, and listened. Presently he heard a faint thud, after which there was silence for a long time. Then came the thud again, and once more a sound of low voices.

All of a sudden Jack heard footsteps on the stairs. Some one was coming up, and closing the door Jack scuttled back to bed. In his hurry he ran right into a chair, and he and it together fell with a fearful clatter on the bare boards of the floor.

JACK scrambled up in a desperate hurry, but almost before he was on his feet the door opened and his brother Bill came in, carrying a lighted candle.

"What are you up to, Jack?" he demanded sharply.

Jack hesitated. He hated the idea that Bill should think he had been spying, and it was on the tip of his tongue to make an excuse and say he had heard something and got out of bed and bumped into a chair. But Jack hated telling lies, and, besides, he was very fond of Bill. He decided to make a clean breast of it.

"I wasn't asleep, Bill," he confessed. "I was wondering what you and Browle were up to."

Bill's face grew stern. "You mean you were watching us, Jack?"

"Yes," replied Jack, plump and plain.

Bill looked at his brother, and Jack felt horribly uncomfortable.

"How much did you see?" Bill demanded.

"I saw you and Browle bringing some packages up from the tarn."

Bill bit his lip. "It's some stuff Browle wants me to keep for him. Nothing to do with you. And see here, Jack, you'll keep your mouth shut about it."

Jack flushed. "That's a rotten thing to say, Bill," he answered sharply.

"Sorry," said Bill quickly. "Of course I know you'd never blab. B-but I wanted you to understand that this is awfully important. If even a word leaked out I might get into a peck of trouble."

Jack looked straight at his brother.

"Then why do you do it, Bill?"

"I—I—the fact is I've got to," replied Bill. "See here, Jack, I can't explain, even to you. You've just got to trust me, and carry on. And now—now you'd better get to bed. It's frightfully late."

"All right," said Jack quietly. "Good-night, Bill."

"Good-night, old chap." And without waiting even to see Jack into bed Bill pushed off.

Jack slipped back into bed, but it was a long time before he got to sleep. The fact was, he was a good deal worried. It was not like Bill to keep things from him, and he felt sure that something was seriously wrong. It looked as if this fellow Browle had some kind of hold over Bill. Jack remembered how he had disliked Browle from the very first minute he had met him some months before. Boys are like dogs. They take instinctive likes and dislikes, and though they cannot explain them there is generally very good grounds for them. The very sight of the long shambling fellow always put Jack's back up, and he felt certain that Browle had a bad influence on Bill. And then quite suddenly Jack fell sound asleep, and for the time Browle and his mysterious doings passed out of his mind.

Jack had meant to be up at six to do his job in the garden, but it was past seven when he awoke, and he had barely time to tub and dress and feed the chickens before it was breakfast time. Bill was not down, and Mrs. Dent said that he was still asleep. Jack was secretly rather glad, for he did not want to have to talk to Bill just then, and he hurried through his breakfast, snatched up his bag and started off to eight o'clock school. Some of the Patrol went to the school at Garth, but he and Kip Carter and one or two other boys were day boys at a small Grammar School kept by a master named Hoyle.

Jack hurried along at a brisk pace and was near the bend in the road above Curt Clinton's little trout farm when a tall figure swung round the bend, coming in the opposite direction, and Jack's lips tightened as he recognized Browle's ungainly figure. Browle was a very big man, but very badly built. He had a large body, long, thin legs, and a great head with a crop of coarse, tow-coloured hair. He was all out of proportion. Another point that did not improve his looks was a permanent scowl. Jack had often wondered if the man could ever look pleased or happy.

Jack walked on briskly, keeping well to his side of the road. He did not even glance again at Browle. Jack was a downright sort of chap, and had no idea of pretending to be friendly with this unpleasant person. Though he refused to look at Browle, he had a feeling the man had his eyes fixed on him, and as he came opposite to him Browle suddenly strode across the road and caught Jack by the arm.

"So I was not good enough for you to speak to?" he snarled.

He spoke fair English but with a queer thick pronunciation. Jack looked him straight in the face.

"Why should I speak to you?" he asked calmly.

"Why shouldn't you?" retorted Browle with a very ugly look in his small greenish-grey eyes. "Was not I your brother's friend?"

"I hope not," said Jack, with a touch of scorn.

Browle's thin lips tightened. "You so impudent brat!" he growled.

"My brother told you not to call me that," said Jack, and then as he felt Browle stiffen he realized what a blunder he had made. "So you was awake!" cried Browle. "You heard. What did you hear?"

He looked so savage that Jack began to be a bit scared.

"Tell me what you heard, or I will make you."

As he spoke he shook Jack savagely. Jack was a bit scared. This was a lonely spot, and he did not know what this long brute would do to him. It seemed to him that the sooner he was out of it and away the better. He let himself go quite limp; then, the moment Browle was off his guard, turned and butted him with all his force in the middle of the stomach.

"Ow!" gasped Browle, as he sat down hard in the road.

But Jack did not wait to give first aid. He ran. Browle was up again in a flash, and now he was really angry.

"Stop!" he bellowed. "Stop, or I will cut the heart out of you!"

He said other things which would not look well in cold print—things which made Jack shiver, but rather with disgust than fright. Jack did not stop. He ran for all he was worth. But the thudding sound of Browle's heavy boots on the road grew nearer and nearer. Browle's legs were considerably longer than Jack's, and he gained fast.

Jack began to be really frightened, for he was sure that if Browle did catch him he would damage him badly. Curt Clinton's gate was still a long way off, but that was the nearest turn, and the road ran between high banks.

Browle stopped shouting. He needed all his breath for running. Those long legs of his, thin as they were, carried him over the ground at a great pace, and Jack realized that he could not reach the gate before being caught. In sheer desperation he swung sharply to the right, jumped with all his might at the steep, grassy bank, flung himself flat on it and went scrambling up like a cat.

Browle grabbed at him, and his long arm just missed the boy. It was so close that his grasping fingers actually touched the heel of Jack's boot. Then Browle went back a step or two and made a rush at the bank.

Jack heard his hissing breath just behind him, but did not dare look back. The bank was nearly twenty feet high, and Jack knew that his only chance was to reach the hedge at the top and squeeze through before Browle reached him. He did not think there was much chance of doing so.

He heard a scratching, sliding noise, a thud, and then a fresh outburst of oaths. He grabbed a branch hanging from the hedge, hauled himself up and looked round to see Browle sitting in the road. The man's face was purple with fury, and his language matched his face. Jack pulled himself up, wriggled through a hole in the hedge, stood up and drew a long breath. He was starting away across the field when a fresh voice cut in above Browle's.

"If you want to use language like that, I'll thank you to do it somewhere else."

Jack turned and looking back through the hedge saw Curt Clinton standing over Browle. His lip was curled, and there was a look of utter disgust on his clean-cut face. Browle got to his feet in a hurry.

"What business was it of yours?" he demanded insolently. "This was a high road, and I say what I like."

"Say any more and see what happens," returned Curt crisply.

Browle was some inches taller than Curt, and this gave him a sense of superiority. He did say something more—nasty words said in his nastiest tone. They were hardly out of his mouth before Curt went into action. A man who has for some years been training Scouts and Rovers is not apt to be a weakling, and Curt, though not big, was tough as shoe leather and in perfect training. One punch did it, and for a third time within a few minutes Browle found himself flat in the dust, but this time his nose was bleeding, and he was not in a hurry to get up.

"I prosecute you for this," he threatened.

Curt took a card from his pocket and dropped it in front of the other.

"Do!" he begged. "There is my name and address. Good morning."

He must have known that Jack was there, but he never even glanced up the bank. Swinging round, he walked back to his own place, and Jack, chuckling under his breath, trotted quickly off to school.

JACK was not feeling happy about Bill, but his spirits were raised by hearing, when he reached school, that they were to have a half-holiday that afternoon. Mr. Hoyle was rather given to making half-holidays at odd times when the weather was fine. During the five minutes' break at eleven o'clock Jack caught Kip Carter.

"I say, Kip, let's go and see old Crosscut this afternoon."

"About the field, you mean?"

"Of course."

"All right, but it's not a bit of good," replied Kip despondently. "The old chap will never let us have an inch of his land for anything—let alone flying."

"Oh, I don't know! He's jolly fond of money, and Mr. Clinton says that we can offer a good rent."

Kip shook his head.

"I feel it in my bones that he will turn us down. But of course we've got to try. And we ought to stand as good a chance as any. He's rather fond of you, Jack."

Jack looked doubtful. "Bessie was," he said, "but not the old man."

"Yes, but the old man was frightfully fond of Bessie."

Jack frowned. "Funny way he had of showing it. Turned her down cold when she married that chap Martin."

"I know, but that's just the sort of thing he would do. He's the old-fashioned sort that think they own their children. But I'm pretty sure that he's just as fond of her as ever."

The bell rang, and they had to break off and hurry back into their class-room. But as soon as school was over and they had eaten their luncheon, the two boys set out for Cold Fell, Hiram Crosby's farm. It was a well-built but bleak-looking house standing some way up the dale above the village. Since his daughter's marriage to an artist named Martin, the old man had lived here all alone except for an elderly housekeeper. The boys found her at home, but Mr. Crosby, she told them, was out. She thought he had gone up Langdale after some strayed sheep.

"We'd better go and find him," said Jack, and he and Kip went on.

Langdale was one of the many small valleys rising out of the big dale. It was narrow and steep-sided and ended in a tremendous rock face more than two hundred feet high.

"There he is," said Kip, pointing to a figure which, dwarfed by its immense surroundings, looked no bigger than a pigmy. It stood at the bottom of a crag looking up. "What's he after?"

"A sheep," replied Jack. "Look! The silly creature has got stuck right up on the face of the crag."

"Gummy, but you've got eyes, Jack," said Kip. "I couldn't see it till you pointed it out. I say, some one's going to have a job getting that down."

Jack grinned. "Our job, Kip. Our good turn. I say, we're in luck."

Kip looked doubtful. "You mean that if we can get that ewe down we can ask the old lad about the field. Well, by Jove, if we get her down we certainly deserve something. But I tell you straight, I don't believe we can."

"Oh, bosh!" said Jack lightly. "Come on."

Old Crosby—"Crosscut" they called him in the dale—turned to meet the boys. He was a big man and a powerful one, though now so old that his hair was almost white. He wore the queer old-fashioned chin whiskers, while his long stubborn upper lip was clean shaven. His frosty blue eyes were still clear as a boy's.

"What be you lads doing up here?" he asked in a voice harsh as the grating of a saw.

"We saw you, and we saw the sheep," said Jack diplomatically. "Can we help you?"

"I don't reckon as any one can help the dratted brute," returned the old chap. "She've got herself into the worst place on the whole crag. Now she's scared to turn round, and she'll stay there till she starves."

"We can't let her do that," said Jack quickly. He had forgotten all about the bargain he had suggested to Kip, and now all his thoughts were for the luckless sheep. "You've got rope at the house, haven't you, Mr. Crosby?"

"Aye, I've rope in plenty, but how'll that help?"

"We can get to the top of the crag by going round," said Jack. "Then you and Kip hold the rope, and I'll go down."

Old Crosscut stared at Jack. "You're crazy, boy. I ain't going to have you break your neck."

"I shan't break my neck," laughed Jack. "Come on, and let's try."

The farmer still looked doubtful, but the ewe was a good one, and he hated to lose her, so he allowed himself to be persuaded. They went back to the farm, got the rope, and after a stiff climb up a very steep slope, reached the breezy head of Langdale Crag. Jack crept to the giddy edge, lay flat on his face and peered over.

"I can't see her, Mr. Crosby. There's a rock in the way. But I know where she is, for I marked the place by a mountain ash growing half-way down the face. Here's where we start."

"I don't seem to like it," said the farmer, frowning. "What be that there brother of yours going to say if you breaks your neck?"

"Kip will be witness you warned me," replied Jack. "Ram the bar in and let's get to it."

Crosby had brought an iron bar and a mallet. He pounded the bar firmly into the ground a little way back from the edge, then made a sling at the end of the rope. Jack sat in the sling and carried a stout stick to keep himself from bumping against the face of the cliff. Luckily there was not much wind, and what there was blew from the west. It is a dangerous business, crag- climbing in a wind.

Jack was no green hand at cliff-climbing, and his head was steady as the crag itself. All the same he had never before been over such a height as this, and it took him a moment or two to get accustomed to it.

"Are you all right?" sang out Kip as the rope began to pay out, and Jack replied:

"All right."

Down he went, swinging a little and spinning rather badly. He could stop this so long as he could reach the crag face with his stick, but sometimes he could not do this, and then the spinning made him dizzy. Foot by foot and yard by yard he descended until he saw the rowan bush just below and a little to his left, growing on a ledge, but plainly as he saw the bush he could see nothing of the ewe.

He gave the signal cord two jerks to show that he was nearly far enough, and they lowered more slowly. He almost bumped the ledge, fended off, swung over, and there was the ewe right under the ledge and—hopelessly out of reach. The ledge projected quite six feet, and the ewe had worked herself up right underneath it. He could see the track which she had followed, and he wondered how on earth she had followed it without falling.

But there she was, standing on a little jut of rock not much bigger than a chair seat.

"Hopeless!" he said aloud, and then she turned and looked full at him, and the expression in her poor frightened eyes made him feel sick with pity.

He signalled to stop, and there he hung, dangling like a spider at the end of its web, wondering how in the world he was going to help the poor creature. He studied every yard of the crag face and at last made up his mind that there was just one way of doing it. It was so risky it made his flesh crawl, but his mind was made up, and he vowed he would take any chance rather than fail.

JACK signalled to be pulled up a little, then by swinging to and fro caught the rowan bush and drew himself on to the broad ledge where it grew. He got out of his sling, and the first thing he did was to fasten the rope to the rowan so as to make sure it would not swing out of reach. He had brought a coil of loose rope with him, and one end of this he fastened firmly round a projecting spur of rock on the northern edge of the ledge—that is, his right as he faced the cliff.

He flung the loose end over and, holding it, started to climb down. For quite six feet the rock was sheer and smooth as the side of a house, and he had to depend entirely on the rope. What was worse, he knew that he would have to swarm up that thin swinging cord when it was time to return. Exactly below a rock jutted out like a shelf, and he breathed a sigh of relief when he felt its firm surface beneath his boot soles. From this a jump would bring him to a second shelf, only just behind the ewe.

A very little jump, not more than five feet, but it is not nice to jump even five feet when there is more than a hundred feet of empty space yawning below and when the landing-place is no bigger than the top of a small writing table. But there was no help for it, and Jack hardened his heart and jumped—jumped so vigorously that he very nearly pitched over the far side of his little landing-place. He steadied himself, drew a long breath, and saw that at last he was within reach of the ewe. She was facing away from him, and the next job was to get a rope round her so that she could be hauled up.

Jack had brought a length of spare rope for this purpose, wrapped round him under his coat, and he got it out. The next thing was to fasten it round the ewe's body. If she got scared and jumped, the odds were that she would take him with her to the foot of the crag. Luckily she was so starved that she had not a kick left in her, but all the same Jack was precious glad when at last he had the rope knotted safely round her poor thin body.

He turned, flung the loose end back across the jut of rock off which he had jumped, then without giving himself time to think, jumped after it. His foot slipped on the smooth surface of the shelf, and if he had not managed to seize the hanging rope, that would have been his finish. His heart beat so hard that for a few moments he felt half suffocated, but he comforted himself by the thought that the worst was over, and set to his next job, which was to fasten the rope attached to the ewe to the end of his own short rope.

Then came the climb back up the sheer face to the big shelf above. Swarming up a rope is never an easy job, but it is worse still when the rope is hanging against a wall, and when Jack at last found himself safe on the wide shelf he was so done that he lay flat on his face for a couple of minutes.

But he knew that Kip would be getting anxious, and he still had a good deal to do. The short rope had to be fastened to the long one, for the ewe must go up first. Very carefully he made it fast, then signalled to Kip to haul slowly. As the rope tightened the poor ewe was hauled, kicking and struggling, from her lonely perch, and Jack had his work cut out to ease the strain. At last he got her safely on the big ledge, and then the two above set to hauling in earnest, and up she went.

Jack watched her to the top and sat and waited until they got her untied. Then came a bumping sound, and down came the rope again with a big stone tied to the end so as to keep it straight. Jack got hold of it, released the stone, fitted himself into the sling and was drawn safely up. The strain had been heavier than he knew, and even old Crosscut noticed how white Jack's face was beneath his tan.

"You sit and rest a piece," he said gruffly. "Then you and Kip can come back to the house and have some tea."

Jack caught a wink from Kip and grinned back. An invitation from old Crosscut was a compliment indeed. He was not the sort to do any entertaining; in fact, most folk vowed he was a regular old miser. Jack was soon all right again, and they tramped back along the ridge through the pleasant spring afternoon. Jack took a chance of whispering to Kip:

"Don't say anything about the field now. Wait till after tea."

"What do you think!" retorted Kip, with another wink. Kip was rather given to winking.

Tea was a good solid meal: excellent home-made crusty bread and home-made butter, a big cake made with dripping but with plenty of currants in it, and a big black pot of strong tea. Nothing stingy about the food, and the boys were sharp set and tucked in.

Old Crosscut did not talk a lot. Yet for him he was almost genial, and he actually smiled when Jack had the good sense to praise the bread and butter. They had tea in the big farmhouse kitchen, and after it was over Jack began to look for his chance of saying something about the flying field. He talked of the Patrol and mentioned that it was Mr. Clinton who had taught him how to climb cliffs.

"Aye," agreed Crosscut, "he's a good man, that. Pity as he's took up with them dratted flying machines."

"But we've got to have them, Mr. Crosby," said Jack gravely. "If it hadn't been for our aeroplanes the Germans would have won the War."

"That's as maybe. I hates the things," retorted the old chap.

Jack's spirits sank, but he would not give up.

"What I want more than anything is to become a pilot," he said.

The farmer laughed. "Well, you got a good head. I reckon you won't get giddy when you flies up."

"But I can't fly unless I am taught, Mr. Crosby."

Old Crosby fixed his sharp eyes on the boy.

"What be you driving at, Jack Milner? I can see as you got something to say to me. For a fact, I've knowed it all the afternoon."

Jack returned the other's gaze.

"That's true, Mr. Crosby," he answered frankly. "The fact is that a small aeroplane has been given to our Patrol, and Kip and I came to ask if you would rent us your lower field to fly from."

The old man frowned. "And have you a-frightening my sheep into fits? No, indeed."

Jack stuck to it. "I give you my word we won't frighten your sheep. We won't fly low over the fells. All our practice will be done over the field itself and down the dale. And indeed, Mr. Crosby, the sheep won't even notice an aeroplane after they've seen it once or twice."

Crosby still frowned, but he seemed to hesitate, and Jack began to hope that he was going to yield. Just then a familiar droning sound came through the open window.

"Why, there's one on 'em now!" exclaimed the farmer, as he jumped up and went to the door.

"Who the mischief is it?" asked Kip quickly, as he and Jack followed. "Can't be the Moth."

"It's not the Moth. The engine's different," replied Jack, as he stepped outside.

He looked up, and there was a plane coming across the fells from the north-west.

"She's not a Moth. She's twice the size," said Kip. "And old, too. Look at that patched wing. Where does she come from, Jack?"

"I don't know. I've never seen her, but I've heard her. I can swear to the note of her engine. She's been over our place more than once by night."

Kip was staring at the plane outlined against the blue of the evening sky.

"He's coming lower," he muttered. "Silly ass! He'll scare the sheep."

Sure enough, the plane was dipping. Next moment she was roaring only a couple of hundred feet across the top of the fell, and at once more than a hundred sheep were racing madly in all directions. Crosby shook his great fist at the plane. Then he turned to the boys, and there was an angry glint in his frosty eyes.

"What did I tell you? The fool has scared pounds off them sheep, and like as not I'll find some with broken legs. Me let you start them things on my ground? No, indeed!"

"HE did it on purpose," said Kip, with savage intensity.

Jack Milner turned and looked at his chum. The two were half- way down the hill on their way back to the hut, and up to this minute neither had said a word.

"Who did?" asked Jack.

"The chap in the plane, of course."

"But who was he?" demanded Jack.

"How do I know? I couldn't see him any more than you could, but I'll vow he came down low on purpose to scare old Crosscut's sheep and put paid to our plan."

"He couldn't," said Jack. "How could he possibly have known what we were doing? Why, it was only yesterday we heard we were going to get the plane."

"Well, it was yesterday," retorted Kip, "and the news was all over the shop this morning. Butter Briggs's mother stopped me on the way to school to ask if it was true. She was in a rare way—said she wouldn't have Butter flying any aeroplanes." He grinned faintly at the idea, but the grin faded, and his weather-tanned face became grim again.

"If you're right, it means that the fellow flying that plane lives somewhere near," said Jack, frowning. "And you know jolly well there isn't any pilot nearer than Mr. Trask's place."

"Yes, there is. There's the aerodrome."

"Great Scott, Kip, you're not saying it was one of the Flying Club! Besides," Jack added, "that plane is not like anything they've got up at Fandle."

"I know that," said Kip, "but all the same I'm certain that chap came low just to scare the sheep. You saw it yourself?"

Jack looked very bothered. "It did seem as if he did it on purpose," he admitted; "but I think it was just mischief, for I don't believe he could possibly have known what we were after."

"And I stick to it he did," said Kip doggedly. "But whether he did or not he's bust up our show all right."

"He's damaged it, not busted it. We can get the lower field all right."

Kip shook his head. "Yes, and we shan't be able to fly more than half the time. The wind's rotten down in that part of the dale."

Jack grew impatient. "We can't help it, Kip. We've done our best, so you may as well stop croaking."

Kip stopped, and no more was said until they were quite close to the Hut, when all of a sudden they heard again a familiar hum.

"He's coming back," cried Kip.

"Bosh, Kip! Don't you know the sound of different planes yet? That's the Moth."

"So it is. What luck! Must be Joe in her, I suppose."

The two watched the Moth come to ground in the field close to the Hut and saw the rest of the Patrol run out. As the two came up Joe Worthy was getting out.

"Master Dick, he said to bring her over," Joe told them. "He wanted to know if you'd got that there field as Mr. Clinton were talking of."

"We haven't," Jack answered. "We've tried, and we'd nearly got old Crosby round when some idiot came flying over low and scared all his sheep and made him as mad as a hornet. It's finished our chances for good."

"Too bad," said Joe. "Who were it?"

"Don't know. A biggish plane with a patched wing. Engine has a queer sort of ringing sound."

"Patched wing, you says?" said Joe eagerly. "Why, that's the one as Master Dick was a-chasing when he got that there fit. Then she didn't crash after all."

"Didn't look as if she had," said Jack glumly. "Kip here vows the pilot did it on purpose, just to score off us."

"How could he?" asked Nibby Gale.

"That's what I said," replied Jack. "The fellow can't belong anywhere about here, or we should have heard of him before now."

"He might," said Kip.

"Well, even if he lived in these parts he couldn't have had a whacking great plane like that lying around without our knowing of it," argued Jack.

Joe Worthy grunted. "Funny business any ways you look at it. I reckon we got to find out what that there plane is, and who the chap is as flies her."

Before any one else could speak again an alarum bell rang loudly in the Hut.

"What's that?" demanded Joe Worthy.