RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

An RGL First Edition

RGL e-Book Cover©

"DON'T, Stan! Don't do that; it makes me shiver!"

Standish Prynne, who was sitting on the outer ledge of the turret window, swinging his legs over fifty feet of empty space, looked round at his sister with an air of faint surprise.

"Sorry, Bee! What's up?"

"Don't sit like that," urged Bee. "Suppose you fell?"

"Why on earth should I fall?" asked Standish, opening his brown eves very wide. "All the same, if it worries you—"

And, with the utmost good nature, he turned and brought his legs back on to the turret stairs.

"What's made you so funky all of a sudden, Bee?" he demanded, looking shrewdly at his pretty sister. "You aren't, usually. Why, if it comes to that, you've got as good a head as I."

"Oh, I don't know!" Bee answered. "I—I just hate the idea of your going to school this term. And—and this is our last day together."

Stan's mouth opened as well as his eyes.

"But, my dear old thing, I thought you were pleased. Besides, where's the odds? 'Tisn't as if I were going away altogether. I shall be here all the time."

As he spoke he waved a hand through the window towards the school buildings, which lay almost beneath the ruined tower. They were, indeed, the modern part of the old stronghold of Storr Royal, the whole of which was owned by Mr. Franklyn Prynne, father of Standish and Beatrice.

"Sometimes I think it would be better if you really were going away altogether!" declared Bee, with unexpected vehemence. "I shall be seeing you in the distance every day, and we shall never have a word together. I think it's unkind of Dad to make you sleep in a dormitory and feed in hall."

Stan held up a hand.

"Steady, old girl!" he said gently. "You mustn't talk like that, you know. After all, Dad knows best, and he told me himself that the real reason why I was not to be a home boarder was simply so that the other chaps couldn't say I was being favoured, or anything like that. But I'm to come home to supper every Sunday evening, and then we can have jolly good talks, you and I. Besides, there are the holidays to look forward to."

But Bee was not to be comforted.

"What's the good of seeing you once a week?" she wailed. "I think it's perfectly horrid!"

Stan saw that she was really upset, so, like the sensible boy that he was, did not try to argue with her. He and Bee were Mr. Prynne's only children, and there was but a year between them. Stan was thirteen and Bee twelve, and the two had always been tremendous chums. Now that his father had decided that Stan was to become a member of the school all this was going to be changed. It would be well enough for Stan himself, for he, of course, would find friends in the school; but Bee was bound to be very lonely.

While these thoughts passed through his head Stan was gazing idly out through the narrow ivy-clad window, and suddenly he saw something which made him start up sharply.

"There's a boy there in the courtyard, Bee!" he exclaimed. "The first arrival!"

Bee was not a bit pleased.

"What's he come so early for?" she demanded. "It's hardly three yet. None of the boys come till the five o'clock train."

"Well, that's one, anyhow," Stan answered. "I—I believe it's Delmar, isn't it?"

Bee looked at the boy. He was dark, rather squarely built, and—well, almost too well dressed. Yet his clothes were good and fitted him perfectly.

"Yes, it's Adnan Delmar," agreed Bee. "He's a horrid boy, I think!"

Stan stared at her.

"Why do you say that?"

"Oh, I don't know! But I don't like him; he's too sleek and pussy-catty. He's always smirking and looking superior. If I were you, Stan, I wouldn't have anything to do with him."

"I thought he was all right," said Stan, rather blankly. "But, hulloa, he must have seen me! He's coming this way."

Bee pulled him quickly aside.

"I don't believe he's seen you at all; the ivy hides us up here. Wait and let's see what he's after."

"Why should he be after anything?" asked Stan, rather aggrieved.

"If he isn't, what's he coming here for? You know the ruins are out of bounds."

"So they are; I'd forgotten that. What a sell. Bee! I shan't be able to come here any more in term time."

"I know," said Bee. "It's horrid! But look at Delmar; he's coming straight here. And watch the way he's looking about. He's trying to make sure that no one is watching him."

Truth to say, there wasn't much doubt about it. The ruinous part of the buildings was on the north side of the great courtyard of Storr Royal, and separated from the newer part by a high iron-fence. After looking carefully round, Delmar had reached the gate opening through the fence, opened it, and slipped through. In a moment he was hidden from the sight of the two watchers above.

Stan and Bee looked at one another.

"This is a queer business," said Stan, in a low voice. "What does he want in the ruins?"

"And why did he come back before any of the other boys?" questioned Bee. "I think we ought to tell Dad."

"No; that would be sneaking," replied Stan quickly. "That would never do. Tell you what; I'm going down to scout around and find what he really is up to."

STORR ROYAL was nearly eight hundred years old, and the ancient castle still stood grand and massive on the higher ground to the north of the new buildings.

Even these were not new, having been built in the days of Queen Anne. Prynnes had lived there from time immemorial, but the present Mr. Franklyn Prynne, the father of Stan and Bee, had belonged to a younger branch of the family, and had never for a moment expected to inherit the great family place.

But for the war he never would have done so, but three cousins had been killed one after another, and in 1918 he found himself head of the family, and master of this magnificent pile of buildings.

Mr. Franklyn Prynne had been a schoolmaster all his life, and had very little money of his own, and the family money had been left away to the wife and daughters of the late owner. So he could not possibly afford to live in the huge house, and he could not sell it because the law of entail forbade.

So he hit upon the great idea of turning the place into a private school, and, having borrowed a considerable sum of money, Mr. Prynne carried out his plan.

He had held a post at a big public school, and, being a popular man and well known, he soon found plenty of pupils, and within two years had nearly sixty boys.

The newer part of the buildings had been turned into class- rooms and dormitories, and Mr. Prynne and his family lived in the dower house, which was, a few hundred yards away. As for the immense mass of ivy-clad ruins, with their great keep, broken staircases, and maze of cellars and dungeons below, these he had thought best to put out of bounds. It was too dangerous to allow the boys to climb about in. During the first term, and before the rule had been made, one boy had been badly hurt by a falling stone, so now there were severe penalties for any boy who trespassed in the ruins.

The thought of these penalties was in Stan's mind as he went quickly but quietly down the steep, winding staircase, followed closely by Bee.

Arrived at the bottom, he stopped and listened. After a moment he turned to his sister.

"I think I hear him," he whispered. "I believe he's gone down into the cellars. Yes, I saw the ivy move. Bee, you stay here and let me go and find him."

"Stay here!" replied Bee indignantly. "No. I'm going, too."

In the centre of the old castle was an old yard. It was deep in nettles, and great piles of rubble half blocked it. Stan stood at the door of the keep for a moment, then hurried across the yard to an opening opposite. Here was an ancient iron-studded door of huge thickness, and so covered with long trails of dark ivy that it was almost hidden.

It stood just ajar, and Stan nodded and slipped through, followed by Bee. A flight of massive stone steps descended into the darkness, but Stan did not hesitate: he went straight down.

The steps led down into an underground chamber with a vaulted roof. A little light leaked in from a narrow slit high overhead. The place reeked of damp, and the air felt chill and heavy.

Here Stan stopped again and listened.

"Can't hear him," he whispered. "But this is the way he went. I'm certain of it."

"He's gone on farther, then," replied Bee, in an equally low voice. "There are a lot of cellars beyond."

"I know. Beastly places. I don't believe even Dad's been through half of them. You'd much better go back, Bee."

"I'm not going to," vowed Bee. The words were hardly out of her mouth before there came a grating sound—then a clang.

"Oh, what's that?" cried Bee, starting.

"The door. Someone has shut the door," snapped Stan, and, spinning round, he ran like a flash back up the steps.

Bee, following hot-foot, found him with his shoulders against the closed door.

"It's no good," he panted. "It's bolted from outside."

"And—and we're locked in," gasped Bee.

"We're locked in," repeated Stan. "Then it's Delmar has done it," declared Bee, speaking with absolute certainty.

"But he went ahead of us."

"He didn't. He hid in the ivy, and waited till we were inside."

"Then he must have known we were after him."

"He knew all right. Either he saw us at the window or heard us coming down the keep stairs."

"I shouldn't wonder if you're right," said Stan, disconsolately. "But what are we going to do now? We might shout till we were black in the face, but no one would hear."

"Perhaps there's some other way out," suggested Bee hopefully.

"If there is I don't know it," answered Stan grimly. "Still, if we don't want to stay here for good, we'd best go and look for it."

STAN struck a match and held it up. The thin glimmer shone upon a low roof, stained with lichen and patches of damp, and upon a floor of cracked and broken pavement. It showed a vaulted passage running on, apparently, endlessly ahead, and to left and right arched entrances to other tunnels. The place was silent as a tomb, and the foul air held a heavy, sour smell.

The match suddenly went out, leaving them in a darkness that could be felt.

"Strike another match, Stan," said his sister.

"Sorry, Bee. That's the last."

Bee shivered.

"What shall we do?"

"Keep going, old thing," replied Stan with a cheerfulness he was far from feeling. They had now been wandering underground for nearly half an hour; and Stan had a horrid suspicion that they had got into one of the secret passages which were said to run from the castle all the way to Priest's Cove, under the sea cliffs. But the fact was that he had not the faintest idea where they were. These passages turned and twisted so that he had lost all sense of direction. They were hopelessly lost, and there was no use in pretending they weren't.

Bee was very plucky. She did not cry, but Stan knew that she was horribly frightened. He was scared enough himself.

But there was nothing to do but go ahead, and Stan groped along with one hand on the wall, the other holding Bee, and shuffling his feet for fear of falling into some pit.

Bee stopped.

"What is it?" asked Stan.

"Light, Stan. It isn't quite so dark, I'm sure."

Stan drew a quick breath.

"You're right, Bee. But where does it come from?"

"From in front. Let's go on."

Another fifty steps, then there was no longer any doubt. A grey gleam penetrated the blackness, coming from high overhead.

"It's a window," cried Stan.

"But it's so dreadfully high. We can never get to it," answered Bee.

"I'll get there," said Stan confidently. "There are steps."

Steps there were, or, rather, what had once been steps. Now they were nothing but ruins, indeed little more than a mere slope of rubble, which rattled and slipped under Stan's feet as he climbed.

Bee held her breath as great stones came clanking down. Each instant she expected to see Stan follow them. But Stan clawed his way like a cat, and in spite of several narrow escapes managed at last to reach the window.

Clinging to a rusty iron bar, he turned.

"It's all right, Bee. We must have come right back somehow. This window looks out on the school."

"Can you get out?"

"Too big a drop, I'm afraid. It's twenty feet to the ground. But wait. I see a chap. I'll hail him."

He shouted, and there was a short pause.

"It's all right, Bee," said Stan. "He's bringing a rope."

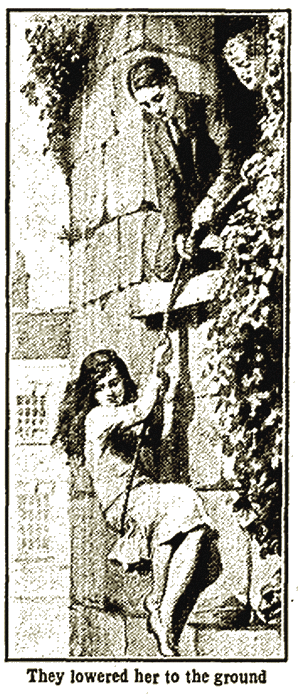

Four or five minutes passed, then Bee heard something hit the window with a swish, and saw Stan catch the loose end of a rope which had evidently been flung up from outside.

"Good shot!" said Stan. "Now wait a jiff, will you? I've got to pull my sister up from inside."

He pulled the rope through and flung an end to Bee, and with its help she came up the broken stairs fairly easily. She found herself looking down through the narrow window on to the school courtyard. Exactly beneath the window stood a boy she had never seen before— a tall, lean boy, whose face was just the colour of an old saddle. He had high cheekbones like an Indian, a straight nose, and a chin like the toe of a boot. His eyes were narrow and very bright, his hair dead black and smoothly parted.

"Well done, kid!" he said, as he saw Bee at the window. "But, say, you can't get down by yourself. You wait, and I'll come right up and give you a hand."

As he spoke he sprang into the ivy and began climbing upwards like a monkey.

"Stop!" cried Bee, horrified. "You'll break your neck."

He paid no attention, but came straight up, and presently stepped lightly into the deep embrasure of the window.

"Guess Hank Harker's neck ain't easily broke," he remarked coolly.

"You're American," said Bee.

"Well, that ain't no crime that I'm aware of," replied the other, with a grin. "But say now, how in sense did you chaps get up here?"

"We'll tell you that afterwards," said Bee, secretly delighted at being classed as a "chap."

"Let's get down first. If Father finds us here he will be pretty cross."

"Why, you must be schoolteacher's kids," said Hank, with his cheery grin. "Here, missy, you get into the bight of this loop, and your brother and I'll lower you."

Hank was extraordinarily quick in all he did, and it seemed no time before all three were safe once more on firm ground.

Hank at once claimed Bee's promise, and Bee was just beginning to tell how she and Stan had been trapped when who should come strolling quietly up but Adnan Delmar himself.

Bee turned on him like a shot.

"Here's the boy who did it," she exclaimed.

Delmar's dark eyebrows rose slightly. He shrugged his shoulders.

"Really, Miss Beatrice, I haven't a notion what you are talking about," he answered.

"We saw you going into the ruins. Stan and I both saw you. We came down from the keep to see what you were doing."

Delmar laughed.

"Why, I have only just arrived," he said. "I came in with Penson and Clarke about ten minutes ago. I've never been near the ruins."

YOUNG Delmar spoke with such complete assurance that his three listeners were left gasping, and for the moment not one of them could find a word to say.

Bee was the first to recover.

"But I saw you," she declared.

"We both saw you come across the quadrangle," said Stan, "and go straight through the gate into the ruins."

Hank caught Stan by the arm.

"Shut right up!" he whispered. "Here's your Dad."

Sure enough, Mr. Prynne himself was coming quickly past. He stopped.

"Ah, so you're back, Delmar," he said. "And you, Harker—I'm glad to see that you have arrived safely. You must come to see me later. Standish, take Harker and show him round. You and he are in the same dormitory. Bee, dear, you had better come with me. It's tea-time."

Bee paused. She was very upset, and for a moment it looked as if she were going to tackle Delmar again. But she caught a quick glance from her brother, and went off with her father, without a word.

Delmar turned and strolled away, leaving Hank and Stan together.

The two looked at one another.

"What's his game?" asked Hank.

"Ask me another. I haven't a notion."

Hank turned, and looked at the great mass of ivy-clad ruin towering against the blue September sky.

"It's a dinky old place," he said admiringly. "I'd like to go over it myself."

"It's out of bounds," Stan told him. "But some day I'll get my father to show you over."

"That's fine," said Hank, as he picked up his rope and coiled it. "Say, come around to the box-room while I put this rope away."

"It's a fine rope," said Stan, examining it. "So light and yet so strong."

"You bet. It's the one my old dad used for roping steers out in Montana."

"Is that your State?"

"It was. Dad's dead, you see."

"I'm sorry," said Stan quietly.

"It's tough," replied Hank. "He and I were good pals. But I've got Mother still, so that's something.

"She's English," he went on. "So now that the ranch is sold she's come back to her folk over here."

While they talked they had reached the big shed where the play-boxes were kept. As Hank put his rope away, Delmar came up. His box was next to Hank's. He opened it and took out a big, rich-looking plum-cake.

"Have some?" he said, as he began to cut it.

"Thanks, no," replied Hank curtly, and in the same breath Stan also declined.

"The chap's got cheek for ten," remarked Hank, as he and Stan walked off together. "He'll bear watching, Prynne."

Before night Stan had decided that Hank was one of the best, and he was pleased to find that Hank evidently returned his liking. Other boys chaffed Hank about his American way of speaking, but Hank took it all with good humour, and gave as good as he got.

As for Stan himself he felt a little strange at first, but he had the advantage of knowing a lot of the boys already, and he soon settled down.

After breakfast next morning the new boys went to Mr. Prynne to be examined for their places in the school, and Stan was delighted to find that he and Hank were in the same form, the Third.

This was Saturday, but regular lessons would not begin till the following Monday. Mr. Prynne, however, had no idea of allowing his boys to wander round at a loose end, and a notice was put up by Burton, captain of the school, that there would be a paper-chase that afternoon, and that all boys were expected to run.

"This is going to be a heap of fun," said Hank as, dressed in shorts and singlet, he joined the hounds at the starting point. "Say, Prynne," he went on, as he looked round, "where's that Delmar fellow? Ain't he running?"

"Not he," replied Stan. "He told Burton he'd got a bad ankle, and was excused."

Hank grinned, and just then the signal was given to start.

The trail of torn paper ran inland, then circled widely towards the coast. About three miles from the school the trail forked and there was a check. Hank grew impatient.

"Let's try this way," he said to Stan. "Looks to me like the right one."

Without waiting for a reply he started off, and Stan, though not feeling at all sure that he was right, followed.

Presently the trail failed completely. They could not find a scrap of paper.

"It don't matter," said Hank. "If we get up on top of that bluff there, I guess we can see the hares."

The hillside was steep, and when they did reach the top there was not only no trail but no sign of either hares or hounds. The two boys found themselves quite alone on the summit of a great cliff overlooking the sea.

"Now we've done it," said Stan. "Pshaw! What's the odds?" answered Hank. "Let the other fellows catch the hares. You and I can jog back along the top of the cliffs. The view's fine!"

Hank was right. The view was magnificent. A strong breeze was blowing and long breakers were bursting against the foot of the cliff, sending up great spouts of foam.

The pair went on easily side by side, and when within about a mile of the school came upon a small bay running deep into the land.

"Priest's Cove," said Stan. "Great place for smugglers in the old days."

"Guess there are some there still," replied Hank, peering over the edge of the cliff, and pointing to two figures on the strip of sand below.

Stan looked, and started.

"One of them's Delmar!" he exclaimed.

"You're right! Delmar it is, but he ain't got his school cap on. And who's the cove in the rat-catcher's kit he's so thick with?"

DELMAR it was—Delmar wearing a tweed cap, and deep in conversation with a very queer-looking man. As Stan and Hank watched they saw the pair move off side by side across the strip of sand towards the cliff, which they began to climb.

"Delmar's ankle must have got well mighty quick," said Hank, drily.

"But what on earth are they after?" asked Stan, eagerly.

"Nothing good, I'll be bound. I reckon it's up to us to find out," replied Hank.

"Come on, then. I know the way down."

"No hurry, son. We don't want them to see us."

Flinging themselves down, they waited. Delmar and his queer companion clambered from ledge to ledge until they were about fifty feet above the beach. Then all of a sudden they disappeared.

"It's a cave! They've gone into a cave!" said Stan.

"That's about the size of it. I told you they were smugglers."

"Nonsense! That's all done with a hundred years ago."

"Well, they didn't climb all that way for nothing. But now's our chance to get down to the beach."

Stan led the way, and ten minutes later the two had reached the strip of beach at the foot of the cliffs. The tide was coming in, and the waves were breaking heavily upon the yellow sand.

Hank drew Stan behind a big rock, and had hardly done so before Delmar and his friend appeared again on the ledge opposite, and began to climb downwards.

"They haven't got any loot!" whispered Hank, staring hard at them.

"And they're looking pretty cross," added Stan.

"It's a queer go," said Hank thoughtfully. "Soon as they've gone, we'll go and squint around a bit."

To reach the path Delmar and his queer friend came right past the rock where the others were hiding. Delmar was frowning, and the other's face wore an ugly scowl. Delmar's companion was short but very broad, and had a low forehead and a crooked nose. He had not shaved for a day or two, and his chin and cheeks were covered with a blue stubble.

The minute they were out of sight, Stan and Hank started for the cave.

"We'll have to hurry," Stan said. "The tide's coming in fast, and it'll be all across the beach in less than an hour."

The climb was easy enough, and it was not long before the two stood at the entrance of a low, black tunnel, running straight into the heart of the cliff. The mouth was cunningly hidden by a big rock, perched on the ledge outside.

"A smuggler's cave all right!" said Stan, as he led the way in.

They went straight on until the light began to fail. Luckily Hank had matches, and, lighting one, they went on.

Suddenly the tunnel divided into two. One branch went straight on; the other curved away to the right.

"Straight on, I guess," said Hank examining the floor. "Here's their footmarks in the dust."

On they went, the tunnel sloping steadily upwards.

"This isn't a cave," said Hank. "It's a reg'lar tunnel, like a mine."

"They did mine tin here in the old days," replied Stan. "I wonder if there is tin here?"

Hank pulled up short.

"If there is we'll never know it," he said, drily. "For here's where we stop."

He struck a fresh match and held it up, and Stan gave a low whistle. The roof was down, and the whole passage choked with a mass of fallen rock.

"That's what made Delmar and Company so cross," grinned Hank. "Well, we'd better follow their example and get back."

There was nothing else for it, so back they went. Reaching the branch tunnel Hank stopped again.

"Let's have a peep at this," he said.

"All right. But hurry," said Stan. The roof here was higher, and, unlike the other, this was a natural tunnel. A few steps led them into a real cave, with a lofty, vaulted roof. The floor was rough and uneven, and very wet.

"Go slow, Hank," said Stan, warningly. "I can hear the waves plainly. There must be a hole somewhere, leading down to the sea."

"You're right. There's a wind, too. There goes my match!"

They pulled up and stood in the darkness, while Hank lit another match. This was difficult, for a strong draught blew through the place, while below, and seemingly quite close, the waves boomed with a deep, hoarse note, which had an unpleasantly threatening sound.

"This is a pig of a place," said Stan uncomfortably. "Let's get out of it."

"Just a jiff," answered Hank. "We're close to the end."

Shielding his match in both hands, he went on towards the end of the cave. Stan followed, but unwillingly.

Suddenly Hank pulled up again.

"You were right, son. Here's a hole, and don't you forget it!"

Stan drew a quick breath. He was standing on the very edge of a circular shaft, about ten feet across, which dropped sheer into utter darkness. It was like a rock pipe, and the sides were polished almost as smooth as glass. From the black depths beneath came a hoarse, angry rumbling, mixed with a strange hissing sound.

"A real ugly place," said Hank. "And see! The pipe goes right up through the roof of the cave."

"Thanks. I've seen all I want," said Stan. "And if we don't get back at once, we shan't get back at all today."

The words were hardly out of his mouth before there came a blast of air from the depths of the pit which not only blew the match out, but nearly blew them off their feet. Then, with a deep roar, a great body of water came spouting upwards. Stan felt it strike him like a wave, and bear him backwards. He was conscious of a yell from Hank. Then the wave was over his head and roaring in his ears. It had seized him, and was dragging him irresistibly towards the mouth of that terrible pit.

STAN'S outstretched hands groped wildly for something to hold on to, something to stop him from being dragged down into the roaring pit.

There was nothing, and he gave up hope.

Through the black, spray-filled gloom a glare of light cut like a knife, and a strong arm seized Stan around the body and plucked him back. The wave washed away, and sank down into the pit, gurgling and sobbing hideously.

"You young idiot, what possessed you to risk your life in such a place?" came a deep, strong voice.

Breathless, half-drowned, and half-blinded, Stan heard the words but could not at first answer.

"Where—where's Hank?" he panted, when at last he found his voice.

"Don't you worry. I'm all right," came Hank's reply, and Hank himself stepped into the light of the electric torch.

"What possessed you two young lunatics to venture into a place like this?" demanded the owner of the torch, whom Stan now recognised as Mr. Lacey, one of the assistant masters at the school.

"I didn't know there was any special danger, sir," answered Stan.

"You didn't know you were in the Blow Hole?"

"No, sir. I remember now I have heard that there was a Blow Hole in Priest's Cove, but I never saw it, and didn't know where it was. I'm tremendously grateful to you, sir."

"Be grateful to the good Providence that brought me here this afternoon," said Mr. Lacey gravely. "If I had not happened to come down here to take some photographs, and had not noticed you entering the cave, you would be beyond help this moment. But let us get away. It is all we shall do."

He was right. They were knee deep in salt water before they reached the path, and it was with feelings of very real gratitude that Stan found himself once more safe on top of the cliff.

Here Mr. Lacey stopped.

"What made you two get into that cave?" he enquired.

"We—Dr—we were just exploring, sir," replied Stan lamely.

"You knew of the cave before?"

"No, sir."

"Then how did you find the mouth? It is quite hidden from below. It can't be seen until you reach it."

Stan was fairly cornered.

"We saw a man come out, sir," he replied.

"Ah, I thought as much! And what was this man like?"

"He was short and rather broad, and had a crooked nose."

Mr. Lacey gave a low whistle.

"Caffyn," he said, half to himself. "Must have been Caffyn. Now, what was he doing there, I wonder."

He turned to the boys.

"Keep clear of that man, both of you. He is a bad lot. I shall not say anything to your father, Prynne. But I shall trust you not to run any foolish risks of this kind in the future. And as for the cave, it's out of bounds."

Stan did not sleep too well that night, and in his dreams lurid pictures of that dark sea cave with its roaring foam spout kept rising before his eyes. He was glad that the next day was Sunday, with an hour extra in bed and the prospect of seeing Bee again!

After dinner he went home, picked up Bee, and he and she went off for a walk. They took their favourite road up through Aphurst Forest, and as they went Stan told Bee about his experiences of the previous day.

Bee listened with shivering interest. Both were so deep in the story that they never noticed two boys standing under a big beech a little way off the road until they were nearly on them.

Bee saw them first.

"There's Delmar now," she whispered, "and another boy with him."

"Yes; it's Dutton," replied Stan. "He's a young cousin of Delmar. Fags for him, and that sort of thing."

"I'm sorry for him," said Bee.

"So am I. But walk straight on and pretend we don't see them."

At that moment Delmar looked up, saw the two, and at once came straight towards them.

"I want to speak to you, Prynne," he said.

The queer thing about Delmar was that no one could ever tell by his voice or face whether he were pleased or angry.

Stan pulled up.

"Go ahead," he said shortly.

"You've been sneaking," Delmar announced.

Stan stiffened.

"I've done nothing of the sort."

"Don't tell lies. I know better. I've seen my friend who was with me yesterday."

"Oh, that chap!" said Stan scornfully. "He doesn't count. But Harker and I kept your name out of it."

"He doesn't count, you say." Delmar spoke slowly and deliberately. "You may find that he counts a good deal more than you imagine."

He paused, and looked hard at Stan.

"You have interfered with me twice already. I'd advise you not to do it again."

The boy's tone put Stan back up thoroughly, but with an effort he kept his temper.

"You may be quite sure I shan't interfere with you as long as you leave me alone and keep clear of the ruins."

"What have the ruins got to do with you?" demanded Delmar.

"They happen to belong to my father," Stan answered quietly.

For once Delmar's self-control seemed to come near breaking.

"Your father!" he said sharply. "Your father had better go slow. If not—"

He pulled himself up short as if he had said too much, and without another word he turned and went back to Dutton.

"WHAT'S up, Stan?" asked Hank Harker as he met his chum in the passage outside their class-room.

Stan's set face relaxed to a smile.

"Not much. I've got to stick in this afternoon instead of playing footer. That young Dutton went and spilt ink all over my sheet of prose, and Mr. Cotter's given it me all to do again. He thought it was my fault."

"Poor luck, son! Have you had it out with Dutton?"

Stan shrugged his shoulders.

"What's the use? Of course, I could lick him, but he wouldn't fight. He'd only blub."

Hank nodded.

"Can I help you any?"

"Afraid not, Hank. Thanks, all the same. You go on up. I'll get through as soon as I can, and follow you to the playing- field."

Stan settled himself to his work in the deserted class-room. In the distance he could hear cheery shouts from the boys watching the match. It was one in which he himself had hoped to play, and he felt very sore that he could not do so.

Time passed. Stan had almost finished his task when he heard a loose board crack in the passage outside. The door was ajar, and the sound came plainly to his ears.

He grinned.

"One of Hank's jokes, I'll bet," he said to himself. "But he won't catch me napping. I'll give him the surprise of his life."

Picking up an old newspaper, he twisted it into a hard roll, then slipped silently out of his place and crept softly to the door.

Another board creaked, but there was no sign of Hank, so, softly pushing the door open, Stan looked out. Much to his surprise it was not Hank, or any other of his friends, but Dutton. And Dutton was stealing on tiptoe up the passage towards the Fourth Form-room.

Dutton reached the door, turned and looked back, and the expression on his fat, tallowy face startled Stan. For Dutton was clearly badly scared and fearfully nervous.

"Something wrong here," muttered Stan as, unseen himself, he watched Dutton creep noiselessly into the Fourth-room. He considered a moment, then followed. Having his indoor shoes on he was able to move as quietly as Dutton.

Dutton had left the door partly open; and Stan, peering round it, saw him standing in the far corner of the room. Opposite were several lockers built into the wall.

One of these Dutton opened, and from it took a metal box which jingled slightly as he moved it. He laid this on a desk, took the key from his pocket, unlocked it, and, taking out some money, slipped it into his own purse.

Stan's throat went dry. The whole thing was clear all at once. For this box, he knew, was the property of Glanfield, who was treasurer of the Fourth Form game fund. This money was the team fund, and Dutton, who had no right in the Fourth-room, for he belonged to the Third, was stealing it.

Stan stepped forward into the room. At the sound Dutton spun round, and his fat, mean face went the colour of tallow. He dropped the box with a clang on the floor, and stood, shaking all over, the picture of guilt and terror.

"You young sweep!" said Stan, striding forward.

Dutton's lips moved, but he made no reply.

"A nice game!" said Stan bitterly. "What do you think Glanfield will say when he knows this?"

Dutton found his tongue.

"Oh, please, you won't tell him?" he begged.

"Would you rather I took you to Mr. Lacey?" asked Stan.

Dutton dropped on a form and burst into tears.

"I shall be expelled!" he cried.

Stan felt beastly.

"You ought to have thought of that before," he said. "What did you do it for?"

Dutton raised his head.

"I—I owe money at the tuckshop. They said they'd tell the Head."

"Why didn't you write home for money?"

"I promised I wouldn't get into debt."

Stan had no reason to like Dutton, but the boy's misery touched his heart.

"If I don't let on, will you promise never to do it again?"

"I will. I promise I will. But—"

"But what?"

"I—I—that is—" He stopped, but his eyes were on the box.

A new suspicion flashed across Stan's mind.

"You don't mean to say that this isn't the first time?" he demanded.

Dutton's silence was as good as a confession.

"Then you can jolly well take your chance!" cried Stan angrily.

"Oh, please—please don't tell!" implored Dutton. "If you only knew how they badgered me! I've been almost crazy."

Stan was silent a moment.

"How much have you taken?" he demanded.

"I—I took seven shillings last Tuesday."

"Put back what you've taken now," ordered Stan. "Then lock the box, and put it back in the locker."

Dutton obeyed.

"Where did you get the key—out of Glanfield's pocket, I suppose?"

"Yes," admitted the other.

"Go and put it back where you found it—at once, before the chaps come down from the field. Then come to the Third-room, and I'll tell you what to do."

The boy scuttled away.

As Stan followed slowly a shadow crossed the window of the classroom, one which looked out on the quadrangle. But Stan, busy with his thoughts, never noticed the dark face which was pressed for a moment against the glass, and then disappeared as suddenly as it had come.

The face was that of Delmar, and could Stan have seen the gleam of gratified malice in Delmar's eyes he would have felt even more worried than he was at the moment.

DUTTON was back in the Third room almost as soon as Stan. He stood looking like a whipped dog.

"I've thought this out," said Stan. "I shall have some money on Saturday, and then I'll give you the seven bob."

"Thanks very much," said Dutton abjectly.

"Wait a minute," snapped Stan. "Don't fancy you're going to bag the key again and sneak the money back. You've got to take the cash to Glanfield and own up."

Dutton almost collapsed.

"I can't," he groaned. "I daren't."

"All right then. I shall tell him myself. We don't keep thieves at this school."

Dutton began to cry, and Stan lost patience.

"Dry up!" he ordered forcibly. "You're getting a chance, and that's more than you deserve. You needn't say where you got the money, and I shall keep my mouth shut. If Glanfield gives you a hammering that's no more than you deserve. But it's better than being expelled."

"Yes," replied Dutton feebly.

"Now clear out. I've got to finish my work."

Dutton did clear, and Stan went back to his interrupted work.

"So much for my birthday half-sov," he said to himself. "And I was meaning to put it towards a new pair of fives gloves. Well, it can't be helped, and if he gives me ten bob there'll be three left. Enough to stand dear old Hank a feed. If only Dutton keeps straight it's worth it. He's had a jolly good scare, and I think it'll do him good."

He finished his job, took it round to Mr. Cotter's room, then went up to the field. The match was over, and the boys, hot and muddy, were coming down.

Hank, racing so as to be first for a bath, waved to Stan as he passed, and Stan turned, thinking he might as well go back. Just then he felt a hand on his shoulder, and, looking round quickly, saw big Burton, the captain of the school football.

"Hallo, young Prynne, why weren't you up today?" he asked.

"Kept in, Burton," answered Stan ruefully.

"Well, you'll please come up on Saturday. I'm trying out the lower boys for the second team. I noticed you the other day in the kids' match, and saw you'd got a turn of speed. I'm choosing your pal Harker, and if you buck up there's no reason why you shouldn't be in."

Stan glowed all over.

"Thanks, Burton; I'll buck up for all I'm worth," he promised.

He returned to the school much more cheerful than when he had come up, and was waiting in the Third room for Hank when a small boy named Penson came in with a note.

"This is for you, Prynne," he said.

Stan took it, wondering a little, and opened it.

It ran as follows:

We want to see you about something. Come round to the fives court at once. It's important. No kid about this.

J. Glanfield

R. Webster.

Stan frowned as he read it.

"Dutton must have weakened and owned up," he said to himself.

The fives court lay on the far side of the quadrangle, and at this time of day was rather a lonely spot. Clouds had covered the sky and a fog was drifting up from the sea as Stan walked across.

A narrow entry led into the place, and Glanfield and Webster were already waiting there. Glanfield was a tall, gaunt youth, and not too popular. He was one of Delmar's friends. Webster was sallow and black-haired, and in the same form as Glanfield. Stan noticed at once that they were both looking very grave.

"Just as well you came," said Glanfield significantly.

Stan opened his eyes.

"Why shouldn't I?" he answered. "You wanted to see me."

"I should rather think we did! When I tell you we've found you out, perhaps you won't be quite so cheeky."

Stan simply stared.

"It's no use your playing the giddy hypocrite," said Webster sourly. "I thought you were a rotter, but I didn't think you were a thief."

Stan went rather white.

"Take that back!" he said quickly.

"Take it back!" broke in Glanfield harshly. "If that isn't a little too good. You young sweep, you were seen in the Fourth class-room this afternoon."

In a flash Stan understood, and for a moment his heart seemed to stop beating. It was all clear enough. One of them had seen him through the window. They had discovered that money was missing from the cash-box, and they suspected him of the theft.

He opened his mouth to blurt out hastily the whole truth of the matter. Then suddenly he remembered his promise to Dutton. His lips were sealed—at least until he had first seen Dutton.

"So that hits you?" sneered Glanfield. "You thought we were all up at footer, and that the field was clear for you to sneak our cash. It was just pure luck that Delmar happened to pass and spot you."

"Delmar, was it? I might have known it!" snapped Stan.

Then he paused, and, pulling himself together, mastered his anger.

"It's perfectly true that I was in the Fourth room this afternoon," he said quietly. "But as for my taking your money, I never touched it."

Glanfield's lip curled.

"All I know is that I'm seven bob short, and that Delmar saw you in our class-room this afternoon when you were supposed to be doing an extra lesson in the Third. Another thing, my keys, which I left in my right-hand trouser pocket in the changing room before I went to footer, were in the left-hand pocket when I came down. You'll find that a bit hard to explain away, I fancy."

Stan hesitated. It was, indeed, impossible to explain unless he brought in Dutton, and that he couldn't do until he had seen the boy.

"See here," said Glanfield, a little less roughly. "We don't want to be hard on you. You're a new chap, and son of the Head. Own up, and hand back the money, and Webster and I will keep dark."

Stan looked Glanfield straight in the face.

"I give you my word I never touched the money," he said.

"You stick to that?" cried Webster.

"Of course I stick to it! It's the truth. And you'll have proof of that before you're many days older."

Glanfield reddened.

"Of all the young liars I ever saw, you take the cake!" he exclaimed. "You admit you were in our class-room. The money's gone, and you swear you know nothing about it."

"I didn't say I knew nothing about it. What I said was I did not touch or take your money. Will that satisfy you?"

"No, by Jove, it won't!" retorted Glanfield. "And I'll tell you this. If you don't own up we shall take further steps. Delmar wanted us to do it right off, only I said it was right to give you a show."

Stan's lip curled.

"Delmar would. And now I'll tell you: I'm sick of this, and, so far as I'm concerned, you can tell anyone you please; but if you do it's you that will suffer, not me."

So saying, Stan swung round and walked off, leaving the two Fourth Form boys in a state of rage and puzzlement difficult to describe.

STAN, too, was very angry, and was wishing heartily that he had never had anything to do with the horrid business. But as he had started he meant to go through with it, and the first thing to do was to see Dutton, tell him what had happened, and make him go straight to Glanfield.

He must do it quickly, too, for once the story got out there would be no saving Dutton from the consequences of his folly.

He went straight back to the Third class-room and, standing at the door, looked round.

Hank, drinking cocoa which he had brewed over a gas jet, hailed him gleefully.

"Say, Stan, come right along and have a mug of this."

"Can't just now, Hank. I want Dutton."

"Dutton. What—haven't you heard? The silly juggins has gone and fallen down the dormitory stairs. They've toted him off to the hospital."

Then Hank saw Stan's face, and, getting up quickly, came across.

"What's wrong?" he whispered. "Everything," groaned Stan. "And, the worst of it is, I can't tell even you."

Hank frowned a little, but his mind was quick to grasp things, and like a flash came his next question. "Something to do with Dutton, I reckon?"

"That's it. And if I can't see him tonight it's going to be an awful mix up."

Hank shook his head.

"By all accounts he's pretty badly hurt, and I don't reckon you can see him tonight. But no one knows the rights of it, and won't till the doctor's seen him. See here: I'll go across to hospital and see if I can get any news."

"That's very decent of you," replied Stan gratefully. "See if you can get a word with Mrs. Griffin, the matron, and tell her I want to see him for about two minutes as soon as he's fit to talk."

"Right you are, son. Meantime, you perch yourself, and take a mug of that cocoa."

"Hank's one of the best," thought Stan, as he poured out his cocoa. It was good stuff, hot, thick, and well sugared, and it did Stan good. He found, to his disgust, that he was quite shaken.

In about five minutes Hank was back. The usual twinkle was missing from his grey eyes.

"No use, old lad. Ma Griffin says he's a sight too bad for anyone to see him tonight. He's had a nasty crack on the head. He's got to be kept in the dark, and no one's to speak to him."

Stan said nothing, but the look on his face told Hank a lot.

"Bad as that, is it?" he asked in a low voice. "Well, don't worry, Stan. Guess you and I can see it through."

The two sat and talked until it was time for afternoon school. After that was over came tea. Stan was walking alone across the quadrangle towards the dining-hall when he met a boy called Warne, a member of the Fourth, whom he knew rather well.

"Hulloa, Warne!" he said. Warne did not seem to see him, and Stan thought he had not heard.

"How goes it, Warne?" he said. Warne turned, looked Stan straight in the face, and walked past without a word.

Stan drew a quick breath. In a flash he understood. Glanfield and Delmar had lost no time. They had spread the story through the school, and he was to be sent to Coventry as a thief.

After tea the boys went into big school for an hour's preparation. Then there was a break before bedtime. This time was spent in the class-rooms, and now Stan began to realise the ordeal before him. Delmar and Co. had done their work well. Four- fifths of the form treated him as if he did not exist.

Only Hank, Chester, and two boys called Willoughby and Hume stuck to him.

The next day was terrible. Stan was thankful for the hours spent in school. Outside not a soul but the four mentioned would speak to, or even look at him.

Late in the day Hank got Stan alone. And Hank's usual expression of dry amusement was gone. His face was very grim.

"See here, Stan," he said, "I can't stick this. Why don't you tell those swabs in the Fourth the truth? I reckon you know right well who took that money and are just trying to let him down easy. But it ain't right. It's not fair to you or to the rest of us."

But with Stan a promise was a promise.

"Can't do it, Hank," he said. "I've got to play the game."

THE next day was worse. Stan, too plucky to remain in the seclusion of the Third Form classroom, met black looks on every side, and more than once heard whispers of "thief."

Schoolboys are very like sheep, and when one sets an example the rest follow. It never seemed to occur to any of them to doubt the story which Webster and Delmar had set afloat.

Even in class the boys next Stan sat as far away as they possibly could, and treated him as if he were a leper. He ground his teeth in silent rage, and fought down an insane desire to go for these fellows and pound them well.

His only consolation lay in the fact that Hank stuck to him through it all, and that a few others, such as Chester, Willoughby, and Hume, refused to join the common cause against him.

As for Hank, he really suffered almost as much as Stan, and when evening came was feeling desperate. By this time he had pieced things together, and come to a pretty shrewd idea of the real truth of the matter. From the first he had been sure that Stan was shielding another boy, and, remembering how Stan had inquired for Dutton on the previous day, he had more than a suspicion that Dutton was the real culprit.

It could not, he felt, be Delmar, because Delmar always had heaps of money.

The question was how to use his knowledge. He thought for a while of going to Burton and telling him his suspicions, but on second thoughts decided that this was too much like sneaking. Then, as he racked his brains for some other way out, the thought of Bee flashed into his mind.

"Gee, but I've got it!" he said to himself. "Bee's the one to talk to."

The question was how to get at her. After thinking it over he posted her a note asking her to meet him after morning school next day at a place at the bottom of the master's garden, which he knew would be deserted at that hour.

When he arrived at the agreed spot she was waiting. Hank was not troubled with shyness, and wasted not a minute in telling the whole story.

Bee's pretty face went white, and for a moment Hank was scared. He almost thought she was going to faint. But there was no weakness of that sort about Bee. It was sheer anger that had for the moment upset her.

"It's that dreadful boy Adnan Delmar," she burst out.

"I allow he's at the bottom of the trouble, Miss Bee," said Hank, "but 'twasn't he who stole the cash. So far as I can judge, the thief was that pasty-faced chap Dutton."

"Dutton! He's Delmar's cousin. Yes; I expect you're right, Hank. And you say he's in hospital?"

"That's so. Tumbled downstairs and cracked his head. But I doubt whether he's as bad as they think he is."

"Or as he says he is," rejoined Bee quickly. "No, Hank; I shouldn't wonder a bit if he were shamming. I wish I could find out."

"I was sort of thinking you might be able to find out," said Hank. "Doesn't your mother go and visit the boys in hospital?"

"Of course she does! And I've been with her once or twice. Yes, Hank; I think I see my way to manage it. I'll pick some flowers and ask Mother to let me take them to the matron. She's an old dear, and I'll get her to take me round, so that I can put the flowers in the rooms."

"That's fine!" declared Hank. "And you'll get a word with young Dutton if it's any way possible?"

"It's going to be possible," said Bee firmly. "You and I, Hank, are going to clear Stan of this horrible accusation."

"And put the blame where it belongs. Miss Bee."

Bee stamped her foot.

"That's the second time you've called me 'Miss.' You're, not to do it; do you hear?"

"All right, Bee," said Hank, his old irrepressible grin lighting up his queer brown face. "And now I must be scooting back to Stan. So-long. You'll let me know how it works?"

"She's a little topper," he said to himself as he doubled back to the school. As for Bee, she stood where she was a minute, evidently thinking hard, then went in through the lower gate of her father's garden and on to the house.

If Mrs. Prynne were a little astonished at Bee's sudden desire to take flowers to the matron she did not say so. She gave her permission, and Bee went off at once on her errand.

In a very short time she presented herself at the door of Mrs. Griffin's room with a great armful of chrysanthemums.

Mrs. Griffin, stout, elderly, with a kindly face, made her welcome; and Bee, concealing her real eagerness, began to talk about the boys in hospital. It appeared that there were only three—Withers and Marston with colds, and Dutton.

Dutton, Mrs. Griffin told her, was much better. He had certainly had a tumble, and been stunned, but the doctor had said that he was nearly well.

"But he doesn't seem in any hurry to go out," said Mrs. Griffin, smiling significantly.

"I expect he thinks it's more comfortable in here," said Bee.

At this moment the bell rang. Mrs. Griffin got up.

"Another visitor, my dear. Wait here a minute."

She went out, and a moment later Bee heard a voice which made her spring to her feet. It was Adnan Delmar's.

Standing just inside the half-closed door Bee heard him and Mrs. Griffin pass.

"Yes, you can see him, Master Delmar," Mrs. Griffin was saying. "He is very much better."

Bee waited till they had passed; then watched them into Dutton's room. Bee's heart was beating hard. At all costs she must hear the interview between them, for she had an absolute conviction that Delmar had come to talk to Dutton about the stolen money.

The question was how to manage it. She looked round, and suddenly saw a way.

The hospital was a bungalow built on one floor, and at the back of each room French windows opened on to a verandah. Quick as a flash Bee was out of Mrs. Griffin's room, and, closing the window softly behind her, slipped across to the window of Dutton's room. It was a warm day, and the window was open. Crouching down behind it, Bee set herself deliberately to listen.

MRS. GRIFFIN was not in the room. Bee could see that much, and only hoped that she would not come out on the verandah. Anyhow, she had to take that chance. She was ready to take any risk—to do anything—for Stan's sake.

Delmar was standing close beside Dutton's bed.

"It's no use your denying it," he was saying. "You took the money."

"Prynne promised he wouldn't tell!" burst out Dutton.

"He didn't," sneered Delmar.

"The ass kept his mouth shut. Result is every one thinks he took it."

"How do you know I took it?" Dutton asked.

"I spotted the whole business through the class-room window."

Dutton groaned, but said nothing.

"What are you going to do about it?" asked Delmar.

"Do? Own up, I suppose!"

"Then you're a bigger idiot than I took you for," said the other. "Have you thought what will happen if you own up?"

"I shall get the sack, I suppose."

"Yes, and be ruined for life. Now you listen to me. Everyone thinks that young Prynne has taken the money. Let 'em go on thinking it. He can't prove that he didn't, and, if it comes to that, I can prove he did. Your name won't appear at all, and if he tries to put it off on you it will be all the worse for him."

This was too much for Bee. Springing to her feet, she was just about to run into the room when the inner door opened and Mrs. Griffin entered.

"You have been here long enough, Master Delmar," she said. "You must go now, please."

Bee bit her lip. But her chance was gone. She went quickly out through the garden, into the playing-field, and so back home.

"BURTON ought to know better than to put Prynne in the team!"

It was Webster who spoke, and the words came plainly to Stan's ears.

Next moment the whistle blew, and the game began.

It was a fine day, with a brisk easterly, breeze, and the turf was fast and dry. Burton kicked off, and in a moment Stan was in the thick of it.

The seniors were, of course, a bigger lot than the juniors, and on the face of it the match seemed one-sided. But if the juniors were smaller and lighter, they had several very good players, who made up in pace and cleverness for lack of size and weight.

Hank, for one, was clever and quick, and young Chester was like a flash of lightning. As for Stan, he flung himself into the game with reckless joy. For the moment, at any rate, he would forget the miseries of the past few days in the delight of using all his strength and brains.

Chester kicked the ball to him, and, dribbling cleverly, Stan went right through the senior half-backs, and before they realised what was happening was right up to their full-back Cotter, who charged him over.

But not before Stan had cleverly centred to Hank.

It was a fine bit of play, but instead of the roar of applause that should have greeted it there was a deadly silence.

Hank took the shot, but, unluckily, the ball, instead of going into the net, hit the goal-post and bounced off into play.

But it had been so near to a goal that the seniors had had a nasty scare, and after that they were very careful, and for the rest of the half neither side scored.

When the second part of the game began the wind was with the seniors, and they made the most of it. But the juniors worked hard, and managed successfully to defend their goal. About five minutes before time the seniors made a big effort, and rushed the ball down the ground towards the juniors' goal. Their centre- forward made a dash and sent in a red-hot shot.

But Hume, the junior goalkeeper, was ready, and, making a supreme effort, leaped up, and, just touching the ball with the tips of his fingers, turned it out.

The ball dropped behind the line, and the seniors claimed a corner.

As the ball was taken out to the corner flag, Stan, who was about a dozen yards from the side of the net, took a quick glance round. The nearest senior half-back had come close in. It seemed that he expected his wing half to kick high, and trust to the wind carrying the ball into the net.

Next moment the ball was in the air. It did rise; then a cross puff of wind caught it, and it came back. Stan dashed in, met it cleverly as it fell, and headed it neatly over the shoulder of the senior half. Before he could turn Stan was past him. He dodged the full-back, and at once was clear of everyone, with no one between him and the opposite goal but Clandon, the goal- keeper.

Stan's strong point was his speed, and he dashed down the ground with the ball flying in front of him. Losing his head, Clandon dashed out to meet him.

It was just what Stan had been hoping for. A quick swerve, a smart sideways kick, and the ball was safe in the net.

Stan, and Stan alone, had won the match for his side.

"Oh, well played, Prynne! Well played!" came a voice. It was Burton, captain of the seniors.

"Well played! Well played!" echoed Hank and two or three others.

But from the ropes not a sound.

Next moment the whistle blew, and Stan, feeling more miserable than ever he had felt before, was walking off the field.

It was not until he had nearly reached the line that he saw his father standing among the boys.

Mr. Prynne's face was very grave, and as Burton came up the headmaster beckoned to him.

"What does this mean, Burton?" he asked.

Burton was silent.

"Please tell me," said Mr. Prynne quietly.

"There is a ridiculous story, sir, that he has stolen some money."

Mr. Prynne's lips tightened.

"Ridiculous or not, the school seems to believe it," he said. "I want the details."

Burton told him.

Then Mr. Prynne saw Stan.

"Stanley," he said in a voice that all could hear, "is it true that you were seen alone in the Fourth Form class-room on Wednesday afternoon?"

Stan was paler than his father.

"It is quite true," he answered.

FOR a second or two Mr. Prynne looked at his son as though he could not believe his ears.

"Is that all you have to say?" he asked at last.

"That is all," replied Stan quietly.

"Go to my study and wait for me," ordered his father.

As Stan turned to obey Hank stepped forward.

"It wasn't Stan, sir," he said sharply.

Mr. Prynne swung round upon the American boy.

"What do you know about it?" he demanded.

"Guess I know he didn't do it," answered Hank curtly.

"Then who did?"

"I don't know—for certain."

"But I do."

It was Bee's voice, and Bee herself, her pretty face flushed and her eyes shining, came suddenly upon the scene. Behind her, with hanging head and face putty-white with terror, followed Dutton.

"What does this mean, Beatrice?" asked her father in a terrible voice.

Bee was not dismayed.

"Dutton, you tell them."

Dutton stood shivering. He opened and shut his mouth like a fish out of water, but no sound came. As for the boys who were looking on, they seemed hardly to breathe.

Mr. Prynne, angry as he was, could not help pitying the boy.

"Tell us what you know, Dutton," he said gently.

At last Dutton found his voice.

"It wasn't Prynne, sir. It was me," he said thickly.

"You mean that you took this money?"

"Yes, sir," answered Dutton, and his voice was suddenly choked by a sob.

"But I don't understand," said Mr. Prynne helplessly. "Stanley, I am told, was seen in the room. Can anyone explain?"

"I think I can, sir," spoke up Burton. "I don't know all the facts, but Prynne was kept in that afternoon, and my impression is that he heard Dutton in the Fourth Form room, and saw him taking the money, and has been trying to shield him."

"Is this true, Dutton?" asked the master.

"Yes, sir," replied Dutton miserably. "He made me put back what I'd taken, and said he'd make up the rest out of some money he would have today. He made me promise I'd go and tell Glanfield, and I was going to when I fell downstairs."

Mr. Prynne drew a long breath of relief. His face cleared like magic. But before he could speak again some boy in the background gave a shout: "Three cheers for Stan Prynne!"

They were given with a will. Stan stood with his eyes on the ground, looking extremely unhappy, but as for Bee, her small face glowed with delight.

Suddenly Glanfield pushed out of the crowd and came to Stan.

"I'm beastly sorry, Prynne," he said. "But I couldn't help it, could I? It all pointed to you."

"That's all right, Glanfield," said Stan; and the boys cheered again as the two shook hands.

Mr. Prynne put his hand on Dutton's shoulder. "Come with me," he said. "You, too, Bee."

And the three slipped quietly away down to the school.

The boys were thronging round Stan. A number had the grace to apologise. Only Delmar and a few of his particular pals and toadies stood aloof.

Hank turned to Delmar. "Guess it's up to you to say you're sorry," he observed briefly.

Delmar looked him full in the face. "When I want lessons from you I'll ask for them," he answered.

"Then maybe you'll get more than you want," retorted Hank.

Then he joined Stan, and all went down to the school together.

"Say, Stan," said Hank, when he had got him to himself, "if it hadn't been for your sister you'd have been properly in the soup."

"How on earth did she come to know anything about it?" asked Stan.

"I told her. But the rest she did herself. She's a topper, Stan."

Stan nodded? "So are you, old chap," he said gratefully. "I shan't forget in a hurry the way you stuck to me."

"Oh, shucks!" jeered Hank. "It didn't take any Sherlock Holmes to see you were taking the blame for some other chap."

Stan started slightly. "I'd almost forgotten Dutton. I say, Hank, I don't want to see that chap, expelled. I must ask Dad what he's going to do."

Hank nodded. "You're the only chap that can. You'd best go right along."

He went, and was away nearly an hour. He never told Hank what happened at that interview, but its success was proved by the fact that Dutton was not expelled. He was not even caned. Mr. Prynne was wise enough to know that his punishment would be no light one. The other boys would see to that. He gave him his chance, and told him plainly that it was up to him to take it.

HANK was in the box-room when Stan came round the corner and saw him. "I've been looking for you everywhere," he exclaimed.

"Well, I guess you've found me," said Hank who was busy coiling that wonderful rope of his. "And what's it all about?"

"Father's given us an extra half-holiday this afternoon."

Hank nodded. "So I heard," he said drily.

"And there's no match. Let's go on the bust."

Hank's answer was to turn solemnly both trouser-pockets inside out. They were quite empty.

Stan put his hand into his and pulled out—a handful of silver.

"Say, what bank have you been burgling?" asked Hank.

"Birthday tips," chuckled Stan, "two of ten bob each. I bought some new fives-balls, and here's the balance. Now, what do you say to a tramp over to Pirley Cove and tea at the tuckshop?"

"I'm right there," replied Hank. "But say, Stan, wish we could ride. I'm plumb tired of walking."

Stan laughed.

"Bring your rope, and we'll catch a couple of the cliff ponies," he said.

"Sounds good to me," said Hank. And just then the dinner-bell rang, and the pair ran.

Dinner over, the two chums set out together. It was a lovely autumn day, with a bright sun and just enough chill in the air to make walking pleasant. Their way led across the broad commons facing the sea, where the late gorse still shone with golden bloom.

Hank was rather silent, but Stan was in great spirits.

"Delmar's taking a back seat nowadays," he said.

"Just shows how cute he is. You notice how cleverly he slipped out of all that business last week. But you keep your eyes skinned, Stan. That chap's got it in for you, and don't you forget it!" Then suddenly he changed the subject. "Say, there are two ponies."

"What about them?" asked Stan, in surprise.

"What's the matter with catching and riding 'em?"

Stan stared. He had quite forgotten his chaffing remarks made before dinner.

Hank was unbuttoning his coat, and, to his amazement, Stan saw that he had his rope wrapped round his body.

"You don't mean you're really going to try to catch those ponies?" he exclaimed, in amazement.

"Won't be much trying about it," said Hank drily. "They'll be as easy as two old sheep."

"But, my dear chap, they're not ours!" objected Stan.

"I'm not going to steal 'em. I only want a loan of 'em," said Hank, as he uncoiled his rope.

Stan saw that the American boy was in earnest, and suddenly the fun and adventure of the whole thing seized him.

"All right," he said; "but I don't believe you can catch one, all the same."

"Watch me," Hank answered, and went forward.

The ponies were shaggy, stocky little beasts belonging, no doubt, to one of the commoners. As Hank approached they both looked up and ceased grazing. Hank stopped dead till they began to eat again.

Then he went on, and, bit by bit, worked up till at last he was within a score of yards of the nearest.

All of a sudden his lasso, which had been hanging in loose coils at his side, leaped into wide circles. The nearest pony heard its hiss, and, kicking up its heels, started away. It was too late. Like a live thing the whizzing rope leaped towards it, and the loop settled squarely round its neck. Hank flung himself right back, and the jerk brought the pony up all standing.

In a flash Hank had reached it and was on its back. Then began a show such as Stan had never seen outside a circus. The pony kicked and bucked, plunging all over the place; but Hank sat as if glued, gripping like wax with the calves of his legs.

It was a gorgeous display of horsemanship.

Finding it impossible to get rid of its rider, the pony bolted. Hank, leaning forward, seized its nose and tried to turn it. But the pony was not taking any.

"Look out, Hank!" shouted Stan. "Look out! He's going straight for the hedge!"

A stiff quick-set bounded the common on the landward side. Stan, running hard, could see a red-tiled roof beyond. He saw the pony reach the hedge, and held his breath, expecting it to stop short and shoot Hank over its head.

Not a bit of it! Sitting tight as ever, Hank rammed in his heels, and up went the pony, soaring over the hedge in splendid style.

Followed a splintering crash, a yell from Hank, a shriek of terror from somebody else, and Stan, flinging himself breathlessly through a gap, saw Hank flat on his back in the middle of a scattered pile of faggots, a girl running like mad towards a small house beyond, and the pony, with the rope trailing behind it, galloping across a potato patch at high speed.

Next instant the pony had jumped the opposite fence and vanished, and Stan was picking Hank out of the sticks.

"Hurt, old chap?" he asked anxiously.

"No!" snapped Hank. "Idiots! Why in sense do they want to stack sticks against a hedge like this? The beastly things brought the pony down, and me too! And now the beggar's gone, and I'm done out of my ride, and my rope too!"

Stan stifled his laughter.

"Just as well," he answered soberly. "You've got to remember this isn't the Wild West, Hank. You've frightened that girl into a fit, and dug up about a row and a half of potatoes. We'd better go and apologise."

He led the way to the house, and they knocked and knocked; but there was no answer. He tried the door, but it was locked.

"No go!" he said at last. "That girl ain't going to trust herself with bandits like us. We'd better go on."

It took Hank some time to recover from his spill. His feelings were hurt. But the tea at Pirley was a remarkably good one, and by degrees he became himself again.

They got back in time for evening call-over, and by next morning had almost forgotten the excitement of the previous day. The two went into breakfast together, and both found letters in their plates.

Stan's was from Bee, who was away on a short visit to an aunt, but was due back next day. He was deep in it when Hank jogged his elbow.

"Stan," he said, "read this!" Stan took the letter, which was badly written on a ruled sheet of cheap paper. It ran as follows:

To Mr. Harker.

Sir, it has cum to my nolledge that you was the gent as rode a pony across mi garden and broke mi pea stix, and frytened mi dorter so they say she'll newer be the same agane. I estermates the dammage done to mi garden and stix as one pound ten shillings, and there's the doktor's bill for Mary as well. You better cum and see me about this job, for if you don't I shall cum and see yore marster. So no more at present from yores truly,

Isac Horton.

"What do you think of it?" asked Hank. Stan frowned.

"I don't half like it," he said. "But how on earth did the fellow get your name?"

"Beats me," replied Hank. "But it's blackmail—no less! Thirty bob for ten cents' worth of pea sticks! Why, it's daylight robbery!"

"All the same, we'd better go," said Stan. "It'll never do to let the business come to my father's ears. He'd make a fuss about roping that pony."

"I guess he would. All serene We'll go right along after dinner and talk real nice to Mr. I. Horton."

IN sharp contrast to the previous lovely day the sky was dull and lowering as Hank and Stan left the school and hurried away towards the coast.

When they came out on the open common above the cliffs Hank slowed down a little.

"Did you see Delmar, Stan?" he asked.

"Delmar? No!"

"He was up at his dormitory window squinting out at us as we left."

Stan frowned. "He's always watching us. I can't think why he bars us so."

"There's more to it than just hating us," answered Hank darkly. "I don't just know what, but I guess we'll find out one of these days."

The pair walked on in silence till in sight of the house and garden which they had invaded so suddenly on the previous afternoon.

"What are we going to say to this fellow Horton?" asked Stan.

"Say—oh, I guess we'll bluff him all right," grinned Hank. "You leave it to me, old son."

He strode up the path and gave a good thump on the door. It opened at once, and Hank stepped back so suddenly that he nearly trod on Stan.

"Gee!" he muttered, and stood staring at the oddest figure he or Stan had ever seen. The man in the doorway was short and very square. His head was covered with a thick thatch of blue-black hair, while his face was almost hidden by whiskers and beard of the same inky hue. He wore blue glasses, from behind which a pair of deep-set eyes were fixed on the boys.

"So you've come?" he growled.

"That's so," replied Hank, recovering himself. "My name's Harker; this is Mr. Prynne. I guess you're Mr. Horton."

"That's my name. Be you come to pay up?"

"Well, we've come to see what we've got to pay for. It's plumb foolishness to talk of thirty shillings for knocking a dozen or two potatoes out of the ground."

"That ain't all. There's the gal and the pony."

"The pony! What's the matter with the pony?"

"You've lamed him."

"Oh rats!" retorted Hank. "There wasn't much lameness about him when he went over that far hedge."

"That's what you say," answered Horton sourly. "Well, you come along round to the stable and see."

"You bet I'll see," said Hank; and he and Stan followed Horton round the house to a row of outbuildings behind.

Horton unlocked a door and stood aside for them to pass. It was very dark inside.

"Where's the pony?" demanded Hank.

"To the left," said Horton. Hank stepped to the left, and Stan after.

The door swung to behind them.

"Steady!" said Hank sharply. "It's dark as—" He broke off short, and, whirling round, leaped for the door. Too late! There was the click of a turned key, a hoarse laugh, followed by the sound of footsteps hurrying away outside.

"The son of a gun!" cried Hank. "He's locked us in."

"But what does it mean?" exclaimed Stan. "Is the man mad?"

"Madness with a method, I reckon," returned Hank drily, as he wrenched vainly at the door.

Finding it fast he wasted no strength on it, but stopped and took a quick glance round.

"What about that window, Stan?" he asked, pointing to a window in the end of the place. It was narrow and so covered with dirt that hardly any light came through it.

"It's barred," said Stan. "Wait, I'll have a squint at it."

Hank struck a match and looked about. The place was not a stable, at all, but a sort of wood and tool shed. A quantity of logs were piled in a corner, and garden tools leaned against the wall.

"Window's no good," came Stan's voice. "Two bars, and they're both firm."

"There's a lot of tools here," said Hank, and picked up a spade.

But the door was too solid and fitted too well for them to break it open. Things looked pretty blue when Stan had a brain wave.

"What about the roof?" he asked. "It's only slates, Hank."

"We can't reach it."

"Yes we can, if we pile those logs."

"Bully for you! That's the trick," cried Hank, and the two set to working like beavers. The walls were no great height, and they soon had a platform high enough to reach the eaves.

Hank climbed up with the spade, forced the blade between the slates, and pulled. With a crack and a crunch the nails gave; a slate went clattering down outside.

"Hurray!" said Stan. "That's the ticket."

Hank wrenched and tore at the slates, and within five minutes had a hole two feet square.

"Give me a boost, Stan," he said. Stan helped him, and in a moment he was up. Straddling the hole, he stooped and hauled up Stan; then there was nothing to do but drop to the ground.

Stan started for the house.

"What do you reckon to do?" enquired Hank.

"Have it out with that swab Horton," replied Stan.

"Guess you won't find him in the house," said Hank drily.

"W-why, what do you mean?"

"I mean that his name isn't Horton, that this isn't his house."

Stan could only stare.

"Mean to say you didn't recognise him?" asked Hank.

Stan shook his head.

"I did, but just too late. I spotted his crooked nose. He's Caffyn."

"THEN it was a plant to get us out of the way?" panted Stan. He and Hank were running side by side back towards the school, and the pace was stiff.

"That's the way it looks to me," Hank answered.

"But what for?"

"Search me—unless they are taking another go at the ruins."

"That's it. I'll bet anything on it. And, being an extra half- holiday, there won't be a soul in the place."

Hank chuckled.

"Looks like we'll be in time to spoil their little game."

"But it's out of bounds, Hank."

"I guess there is one time that bounds don't count," said Hank.

"But if we go through the quad Lodgy will see us."

"The gate porter? Yes, that's so. But he'd see Caffyn, too. Can't we get in any other way?"

"Yes, of course. Through father's garden."

"Then that's Caffyn's game."

"All right," said Stan. "We'll try it."

At the pace they were going it did not take long to get back, and very soon they were at the spot at the back of Mr. Prynne's garden where Hank had met Bee on that day when the two had planned to clear Stan of the charge made against him by Delmar.

Stan opened the gate, and looked round.

"There's no one about," he said. Hank chuckled.

"What's the matter?" asked Stan.

"Only it's a bit comic your being out of bounds in your own dad's garden. But never mind. How do we get up to the ruins?"

"I'll show you. Keep behind these raspberry bushes."

The pair crept through the bushes like two Red Indians. At the top of the bed Hank caught Stan by the arm.

"Steady, Stan!" he said in a low whisper. "I can see Caffyn."

The place where they were hidden was close under the south side of the ruins, the tall, ivy-clad walls of which bounded the garden on the north. Mr. Prynne's house could not be seen because of a row of big plum and pear trees which ran between the kitchen and the flower garden. One of these pear trees, the biggest of the lot, grew quite close to the wall of the ruins, its branches almost touching the thick ivy covering the wall.

It was to this tree that Hank was pointing, and Stan at once saw that there was someone in the pear tree climbing cautiously up.

"I see!" he whispered. "Jolly cute on his part. There's a window just opposite, and not very high up. He's going to get through it. Look here! You go and stand under the tree, and I'll slip along and fetch help. Then we're bound to nab him."

Hank stretched out a long arm and caught hold of Stan.

"No, sir!" he answered curtly. "That won't help any."

"Why not?"

"Because you can only run him in for trespassing. He'll swear he's after birds' nests or something of that sort. What we've got to do is to find out what his real game is." Stan nodded.

"I see; but how?"