RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an Australian recruitment poster (1915)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an Australian recruitment poster (1915)

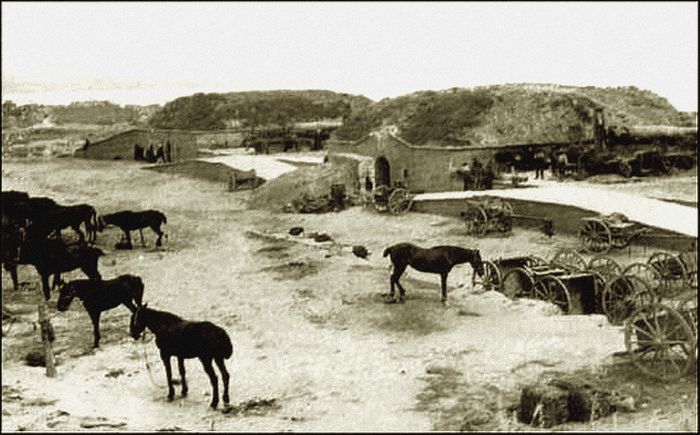

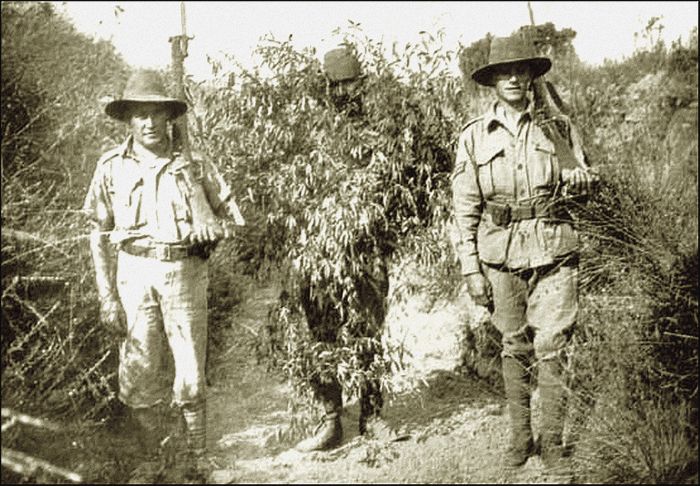

Our splendid Indian troops stood ready at

Alexandria to embark for the Dardanelles.

'FUN!' said Ken Carrington, as he leaned over the rail of the transport, Cardigan Castle, and watched the phosphorescent waters of the Aegean foaming white through the darkness against her tall side. 'Fun!' he repeated rather grimly. 'You won't think it so funny when you find yourself crawling up a cliff with quick-firers barking at you from behind every rock, and a strand of barbed wire to cut each five yards, to say nothing of snipers socking lead at you the whole time. No, Dave, I'll lay, whatever you think, you won't consider it funny.'

Dave Burney, the tall young Australian who was standing beside Ken Carrington, turned his head slowly towards the other.

'You talk as if you'd seen fighting,' he remarked in his soft but pleasant drawl.

Ken paused a moment before replying.

'I have,' he said quietly.

Burney straightened his long body with unusual suddenness.

'The mischief, you have! My word, Ken, you're a queer chap. Here you and I have been training together these six months, and you've never said a word of it to me or any of the rest of the crowd.'

'Come to that, I don't quite know why I have now,' answered Ken Carrington dryly.

Burney wisely made no reply, and after a few moments the other spoke again.

'You see, Dave, it wasn't anything to be proud of, so far as I'm concerned, and it brings back the most rotten time I ever had. So it isn't much wonder I don't talk about it.'

'Don't say anything now unless you want to,' said Burney, with the quiet courtesy which was part of him.

'But I do want to. And I'd a jolly sight sooner tell you than any one else. That is, if you don't mind listening.'

'I'd like to hear,' said Burney simply. 'It's always been a bit of a puzzle to me how a chap like you came to be a Tommy in this outfit. With your education, you ought to be an officer in some home regiment.'

'That's all rot,' returned Ken quickly. 'I'd a jolly sight sooner be in with this crowd than any I know of. And as for a commission, that's a thing which it seems to me a chap ought to win instead of getting it as a gift.

'But I'm gassing. I was going to tell you how it was that I'd seen fighting. My father was in the British Navy. He rose to the rank of Captain, and then had an offer from the Turkish Government of a place in the Naval Arsenal at Constantinople.'

'From the Turks!' said Burney in evident surprise.

'Yes. Lots of our people were in Turkey in those days. It was a British officer, Admiral Gamble, who managed all the Turkish naval affairs. That was before the Germans got their claws into the wretched country.'

'I've heard of Admiral Gamble,' put in Burney. 'Well, what happened then?'

'My father took the job, and did jolly well until the Germans started their games. Finally they got hold of everything, and five years ago Admiral Gamble gave up. So did my father, but he had bought land in Turkey and had a lot of friends there, so he did not go back to England.

'It was that same year, 1910, that he found coal on his land, and applied for a concession to work it. The Turks liked him. They'd have given it him like a shot. But the Germans got behind his back, and did him down. The end was that they refused to let him work his coal.

'Of course he was awfully sick, but not half so sick as when a German named Henkel came along and offered to buy him out at about half the price he had originally paid for the place.

'Father had a pretty hot temper, there was a flaming row, and Henkel went off, vowing vengeance.

'He got it, too. A couple of years later, came the big row in the Balkans, and the war had hardly started before dad was arrested as a spy.'

'Henkel did that?' put in Burney.

'Henkel did it;' young Carrington's voice was very grim. 'Pretty thoroughly too, as I heard afterwards. They took him to Constantinople, and—and I've never seen him since.'

There was silence for some moments while the big ship ploughed steadily north-eastwards through the night.

'And you?' said Burney at last.

'I—I'd have shared the same fate if it hadn't been for old Othman Pasha. He was a pal of ours, as white a man as you want to meet, and he got me away and over the border into Greece. It was in Thrace that I saw fighting. I came right through it, and got mixed up in two pretty stiff skirmishes.'

'My word, you've seen something!' said Burney. 'And—and, by Jove, I suppose you understand the language.'

'Yes,' said Carrington quietly. 'I know the language and the people. And you can take it from me that the Turks are not as black as they're painted. It's Enver Bey and his crazy crowd who have rushed them into this business. Three-quarters of 'em hate the war, and infinitely prefer the Britisher to the Deutscher.'

'And how do you come to be in with us?' asked Burney.

'I joined up in Egypt,' Carrington answered. 'I went there two years ago and got a job in the irrigation department. I've been there ever since.'

Again there was a pause.

'And what about Henkel?' asked Burney. 'Have you ever heard of him since?'

'Not a word. But'—Ken's voice dropped a tone—'I mean to. If he's alive I'll find him, and—'

He stopped abruptly, and suddenly gripped Burney's arm.

'There's some one listening,' he whispered. 'I heard some one behind that boat. No, stay where you are. If we both move, he'll smell a rat.'

'Well, good-night, Dave,' he said aloud. 'I must be getting below.'

Turning, he walked away in the direction opposite to that of the boat, but as soon as he thought he was out of sight in the darkness, he turned swiftly across the deck and made a wide circle.

He heard a rustle, and was just in time to see a dark figure dart forward, the feet evidently shod in rubber soles which moved soundlessly over the deck.

He dashed in pursuit, but it was too late. Being war time, the decks were of course in darkness, and the man, whoever he was, disappeared—probably down the forward hatch.

Ken came back to Burney.

'No good,' he said vexedly. 'The beggar was too quick for me.'

'Then there was some one there?'

'You bet. I saw him bolt.'

'Any notion who it was?'

Ken hesitated a moment.

'I'm not sure,' he answered in a low voice, 'but I've got my suspicions. I think it was Kemp.'

'What—that steward?'

'Yes, the chap who looks after the baths.'

'My word, I wouldn't wonder,' said Burney thoughtfully. 'He's an ugly looking varmint. But why should he be spying on you?'

'Haven't a notion. But I've spotted him watching me more than once since we left Alexandria. I'm going to keep my eye on him pretty closely the rest of the way.'

'Not much time left, old son. They say we'll be in Mudros Bay to-morrow morning.'

'Yes, I heard that. Which reminds me. I'm going down to get a warm bath. It may be the last chance for some time to come.'

This time Ken Carrington said good-night in earnest, and went below.

It was early for turning in, and nearly all of the troops aboard were still on the mess deck. Ken got his things from his bag and went down the passage to the bathroom. The Cardigan Castle had been a swagger liner until she was impounded by Government to act as troopship, and she was provided with splendid bathrooms.

Carrington opened the door quietly, and was feeling for the switch of the electric, when he noticed, to his great surprise, that a port hole opposite was open.

Needless to say, this was absolutely forbidden. In war time a ship shows no lights at all, and it is a fixed rule that everything below must be kept closed and curtained.

Before he could recover from his first surprise he got a second shock. A tiny pencil of light—just a single beam, no more than a few inches in diameter—struck through the darkness and formed a small luminous circle upon the white-painted wall above his head.

It only lasted an instant, then a dark figure rose between him and the open port, and instantly the beam was intercepted, and all was dark as before.

Through the gloom he vaguely saw the arm of the man who stood in front of the port raised to a level with his head, while his hand moved rapidly.

Instantly he knew what was happening. This man was signalling. Carrington had heard of the German signalling lamp which, by means of ingeniously arranged lenses, throws one tiny ray which can be caught and flung back by a specially constructed mirror. That was what was happening before his very eyes. A glow of rage sent the blood boiling through his veins, and forgetting all about the switch he sprang forward.

As ill luck had it, there was a wooden grating in the middle of the cement floor. In the darkness, he failed to see this, and catching his toe, stumbled and fell with a crash on hands and knees.

He heard a terrified yelp, and the man made a dash past him for the door.

But the door was closed. Carrington had shut it behind him. Before the fellow could get it open, Ken was on his feet again, and had flung himself on the signaller.

Ken flung himself on the signaller.

With a snarl like that of a trapped cat, the man wrenched one arm free.

'Take that!' he hissed, and next instant Ken felt the sting of steel grazing his left shoulder. The sharp pain maddened him, and his grip tightened so fiercely that he heard the breath whistle from his opponent's lungs.

At the same time he flung all his weight forward, and the other, thrown off his balance, went over backwards and came with a hollow crash against the door.

The two fell to the floor together, and rolled over, fighting like wild cats.

Ken's adversary was smaller than he, but he seemed amazingly strong and active. He wriggled like an eel, all the time making frantic efforts to get his right hand free, and use his knife again.

But Ken, aware of his danger, managed to get hold of the fellow's wrist with his own left hand, and held it in a grip which the other, struggle as he might, could not break. At the same time, Ken was doing all he knew to get his knee on his enemy's chest.

It was the darkness that foiled him—this and the eel-like struggles of his adversary. At last, in desperation, he let go with his right hand, and drove his fist at the other's head. He missed his face, but hit him somewhere, for he heard his skull rap on the floor, while the knife flew out of his hand, and tinkled away across the cement floor.

Ken felt a thrill of triumph as he heaved himself up, and getting his knees on his adversary's chest, seized him with both hands by the throat.

Before he could tighten his grip came a tremendous shock, and he was flung off the other as if by a giant's hand. As he rolled across the floor, followed a crash as though the very heavens were falling. The whole ship seemed to lift beneath him, at the same time stopping short as though she had hit a cliff.

For an instant there was dead silence. Then from the decks above came shouts and a pounding of feet. Half stunned, Ken struggled to his feet, and staggered towards the door. As he did so, he heard the click of the latch, and before he could reach it, it was banged in his face.

Groping in the darkness, he found the handle. He turned it, but the door would not open. In a flash the truth blazed upon him. He was locked in. The spy had locked the door on the outside. He was a helpless prisoner in a torpedoed and probably sinking ship.

KEN'S head whirled. For the moment he was unable to collect his ideas. He stood, grasping the door handle, listening to the thunder of feet overhead and the shouted orders which came dimly to his ears.

He heard distinctly the creaking of winches, and knew that the boats were being lowered. His worst suspicions were true; the ship was actually sinking.

This lasted only a few seconds. Ken Carrington was not the sort to yield weakly to panic. He pulled himself together, and felt for the switch.

It clicked over, but nothing happened. The shock of the explosion had evidently thrown the dynamo out of gear. Then he remembered the little electric torch which he always carried, and in an instant had it out of his pocket, and switched it on.

He flashed the little beam across the floor, and its light fell upon the wooden grating over which he had stumbled in his first rush at the enemy signaller. This lay alongside the bath. It was about six feet long and made of four heavy slats nailed on a framework.

It took Ken just about five seconds to lay down his lamp and heave up the grating.

Short as the time had been since the first shock of the torpedo, the ship was already beginning to list heavily. The floor of the bathroom now sloped upwards steeply to the door.

The grating was very heavy, but in his excitement Ken swung it up as though it had been no more than a feather. Balancing it, he charged straight at the door.

The end of the grating struck the woodwork with a loud crash, but the result was not what Ken had hoped. Hinges and lock remained firm. One panel, however, was cracked and splintered.

He retreated again to make another attempt. But the list was growing heavier every moment. It was all he could do to keep his feet. Ugly, sucking noises down below told him that the water was rushing in torrents into the hold of the doomed ship.

There was no question of making a second charge. Balancing himself as best he could opposite the door, he pounded frantically at the cracked panel, and at the third blow it broke away, leaving a jagged hole.

But this was not large enough for him to put his head through—let alone his body. His one chance was that the key might still be in the lock.

Small blame to him that his heart was going like a trip-hammer as he dropped the useless grating and snatched up his lamp.

The list was now so heavy that he had to cling to the door, as he thrust his arm through the gap.

A gasp of relief escaped his lips as his fingers closed on the key. It turned, but even then the door would not open. It was wedged.

Ken made a last desperate effort, and managed to force it open. As he clawed his way through into the passage, the sea water came bursting up through the floor of the bathroom behind him.

Somehow he managed to scramble along the passage, and up the companion to the mess deck. There was not a soul in sight, and the ship now lay over at such an angle that every moment it seemed as though she must capsize.

Up another ladder. He was forced to go on hands and feet, clinging like a squirrel. Then he was on the boat deck, in a glare of white light flung on the sinking ship by the searchlight of a British cruiser which had rushed up to the rescue.

The sea seemed thick with boats pulling steadily away, and in every direction the searchlights of the escorting destroyers wheeled and flashed, as they rushed in circles, hunting for the submarine which had struck the blow.

But the Cardigan Castle was empty and deserted. With that marvellous speed which only perfect discipline ensures, every soul had already been got away into the boats. So far as he could see, Ken was left alone on the fast sinking ship.

Even so, he was not ungrateful. If he had to perish, it was far better to drown in the open than to come to his end like a trapped rat down below.

'Ken! Ken!'

Some one came rushing up into the searchlight's glare.

It was Dave Burney.

'I've been hunting the ship out for you,' exclaimed Dave breathlessly.

'I got locked in the bathroom,' Ken answered quickly. 'No time to explain now. Tell you afterwards. I say, old man, it was jolly good of you to wait for me, but I'm afraid you've overdone it. All the boats are away.'

'Hang the boats! Here—put this on. Sharp, for she won't last more'n a couple of minutes.'

As he spoke, he flung Ken one of the life-saving waistcoats which are now used instead of the old-fashioned lifebelts.

'It's all right,' he added, as he saw Ken glance at him sharply. 'I've got one, too.'

Ken did not waste a moment in slipping on the queer garment, and blowing it up.

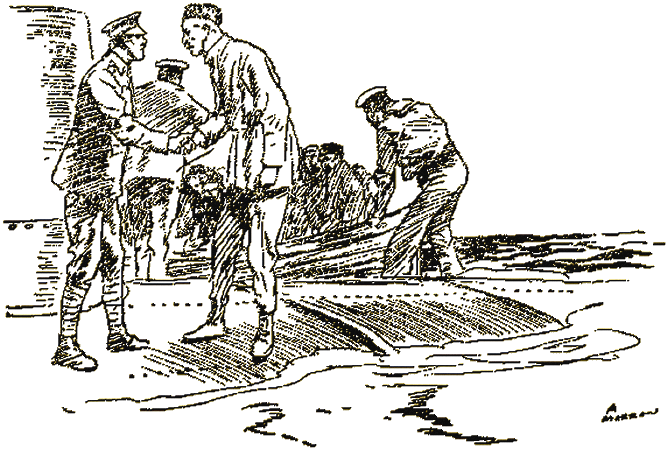

'This way,' said Dave, as he scrambled up the steep deck to the weather rail. Ken followed, and they had barely reached the rail when the big liner rolled slowly over on to her side.

Dave sprang out on to her steel side which was now perfectly level.

'Hurry!' he shouted. 'She'll pull us down if we're not clear before she sinks.'

He sprang out into the water. Ken followed his example, and the two paddled vigorously away. Luckily for them, the ship did not sink at once. She lay upon her beam ends for four or five minutes, and gave them time to get to a safe distance. They were perhaps forty yards away when there came a loud, hissing, gurgling sound.

He sprang into the water.

'She's going!' cried Ken. Turning, he saw her stern tilt slowly upwards. Then, with hardly a sound, the fine ship slid slowly downwards, and a minute later there was no sign of her except a great eddy in which swung a tangled mass of timber, lifebelts, canvas chairs, and all sorts of floating objects from the decks.

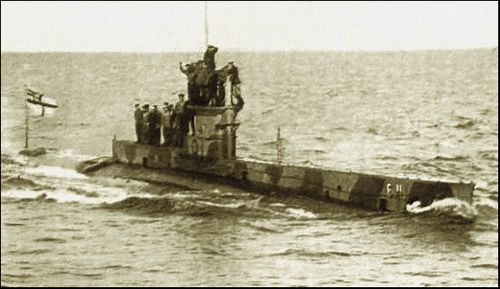

'The brutes!' growled Dave. 'This means that the Turks have got submarines.'

'I doubt it. That was probably the work of an Austrian or German craft. Well, thank goodness, they only got the ship and not the men.'

'Ay, we'll get our own back for this before we're through,' growled Dave. 'My word, but it's cold! Hope they're not going to be long picking us up.'

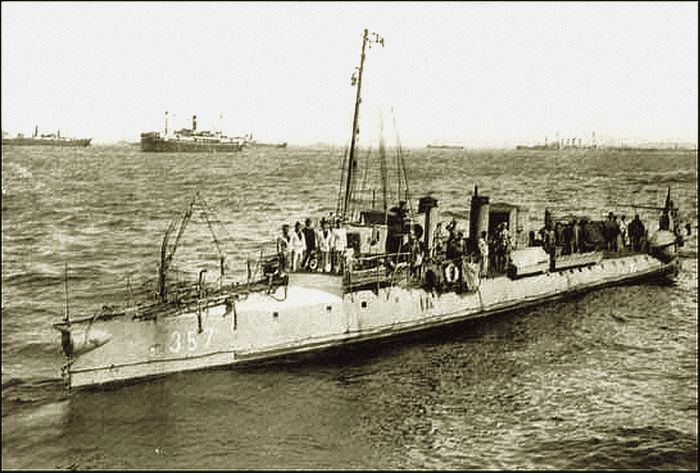

'No. Here comes a boat,' Ken answered, as the searchlight showed a boat pulling hard towards them. A couple of minutes later they were hauled aboard, and in a very short time found themselves on the British destroyer 'Teaser.'

'Any more of you in the water?' asked her commander, Lieutenant Carey, a keen, hard-bitten young man of about twenty-eight.

'No, sir, I think not,' Ken answered. 'I believe every one else got off in the boats.'

'Yes, I don't think our German friends have much to boast of,' said the other with a smile. 'We can build fresh ships all right, and so far as I know they haven't got a single man. But you fellows look perished. Down with you to the engine-room. Coxswain, get out some lammies for them, and see they have cocoa.'

'Ay, ay, sir,' answered the coxswain.

But Ken paused.

'I have a report to make before I go below, sir.'

The commander looked a little surprised.

'All right. But quick about it. You'll be a hospital case if you stick about in those wet togs much longer.'

Ken wasted no time in telling what he had seen in the bathroom of the Cardigan Castle, just before she was sunk.

Commander Carey listened with interest.

'Who was this fellow?' he demanded.

'I never saw his face, sir, but by his voice I am pretty sure he was Kemp, a steward.'

'Hm, it was rotten bad management, allowing a fellow like that to be aboard a transport,' growled Carey. 'Very well, Carrington, I shall report the matter at once by wireless, and if he is aboard any of the other ships, you may be sure he'll be attended to. And I congratulate you on getting out alive. Now go below and get a warm and a change. I'll land you and your friend in Mudros Bay if I can, and if I have other orders I'll tranship you.'

Feeling very shivery and tired, Ken was escorted below to the genial warmth of the engine-room, where he found Dave already changed, and engaged in putting away a great mugful of hot Navy cocoa.

The coxswain, big Tom Tingle, fished him out a suit of lammies, the warm gray woollen garments which are the regular cold weather wear of the British Navy, and, as soon as he had got into them, put a mug of steaming cocoa into his hands.

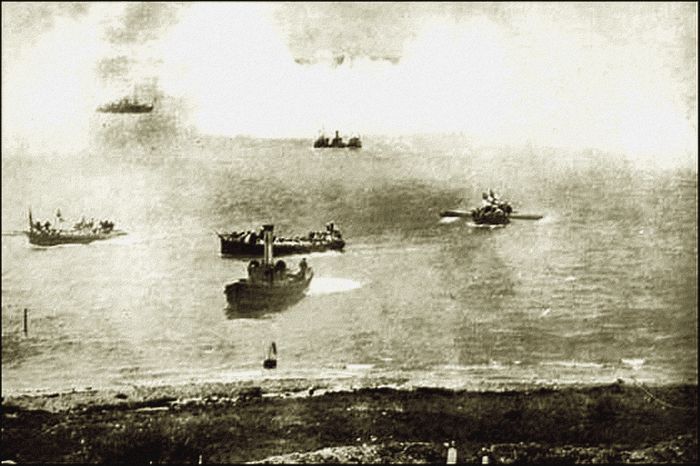

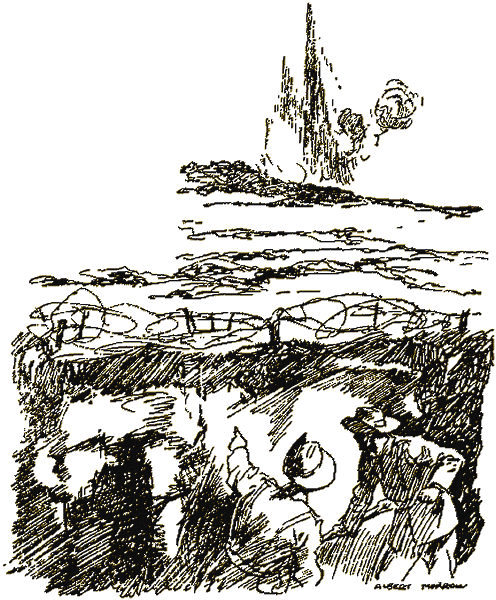

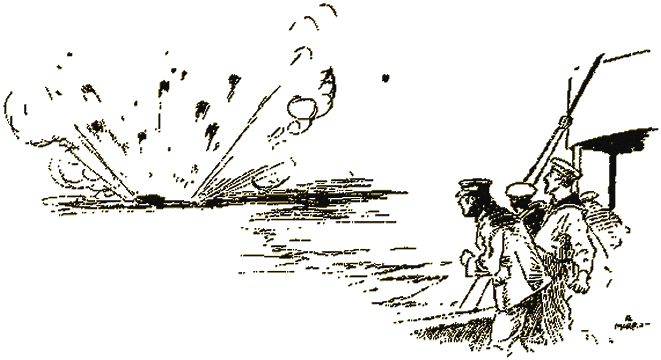

A friendly salute in passing.

The landing party at Sari Bair reached the

beach covered by the fire of their own guns.

'Prime stuff, ain't it, Ken?' said Dave, and Ken, as he felt the grateful warmth creeping through his chilled frame, nodded. Then he and Dave were given a couple of blankets apiece, and with the beat of the powerful engines as a lullaby were soon sleeping soundly.

When they awoke, the gray dawn light was stealing through the hatch overhead, and the smart little ship lay at anchor, rocking peacefully to the lift of a gentle swell.

'Rouse out, you chaps,' came Tingle's voice. 'Rouse out, if you want some breakfast. The old man's going to put you aboard the Charnwood to finish your voyage. You'll find some of your pals in her, I reckon.'

'Did they get the submarine?' was Ken's first question.

Tingle's honest face darkened.

'No, by gosh. She slipped away in the dark, and never a one of us set eyes on her. What are ye to do with a thing like that? It's like trying to tackle a shark with a shot gun.'

'Here's your khaki,' he continued, 'dry and warm. Shift as sharp as ye can. The old man, he don't wait for nobody.'

Ken and Dave changed in quick order, and as soon as they had finished were conducted for'ard for breakfast. Biscuit, butter out of a tin, sardines, and cocoa. War fare, but all the best of its kind, and the boys did justice to it.

The 'old man'—that is, Commander Carey—was on the bridge when they came on deck. He greeted them kindly, and Ken ventured to ask if anything had been heard of Kemp.

'Not a word,' was the answer. 'He's not been picked up, so far as any one knows. Probably he's food for the fishes by this time. Well, good-bye to you. Wish you luck.'

'Thank you, sir,' said Ken and Dave together. Then they were over the side into the collapsible, and were pulled straight across to the wall-sided Charnwood which lay at anchor less than half a mile away.

Mudros Bay, which is a great inlet in the south of the island of Lemnos, was alive with craft of all sorts. Warships and transports by the dozen, British and French, were lying at anchor in every direction, and in and out among them, across the brilliant, sunlit waters, dashed picket boats and all sorts of small craft.

'My word, this looks like business!' said Dave, as he glanced round at the busy scene.

'It does,' agreed Ken. 'Last time I was here, there were two tramps and an old Turkish gunboat. Not a darned thing else.'

A couple of minutes later they were alongside the big 'Charnwood,' to be greeted with shouts of delight from a number of their Australian comrades who were leaning over the side.

They said good-bye to the destroyer men who had ferried them across, and climbed the ladder to the deck, where they were immediately surrounded and smacked on the back, and generally congratulated. The two were very popular with the whole of their battalion, and their comrades were unfeignedly glad to find that they had not lost the number of their mess.

Pushing through the throng, they went aft to report themselves to their commanding officer, Colonel Conway. He had, of course, already heard of Ken's adventure with the spy in the bathroom, but took him aside to get further particulars.

'No, nothing has been heard of him,' he said. 'I do not think it possible that he can have been picked up.

'And yet,' he added, 'that's odd, for he must have had plenty of time to get on deck, and, so far as we can learn, we have not lost a man.'

'Do you think the submarine could have picked him up, sir?'

'Not a chance of it. She went under the very moment she had fired her torpedo. If she had not, the destroyers would have got her.'

'I ought to have got Kemp, sir,' said Ken, rather ruefully.

'You did your best, Carrington,' the other answered kindly. 'And you are to be congratulated that Kemp did not get you.'

Ken went back to join his friends forward, and answer a score of questions as to the struggle in the bathroom. By the remarks of his companions who had, one and all, lost everything they possessed, except what they stood up in, it was clear that Kemp, if still alive, would stand a pretty thin chance should any of these lusty Australians set eyes on him again.

There was no shore leave. No orders were out yet, but the rumour was everywhere that they were to sail that very day.

Presently a tug came alongside with fresh provisions. She also brought a quantity of rifles and ammunition to replace those lost in the sunken Cardigan Castle. Spare uniforms, overcoats, and other kit were also put aboard, and shared up among the shipwrecked troops.

'The old country's waked up this time,' said Dave to Ken, as he tried the sights of a new rifle. 'There's stuff ashore here for an army corps, they tell me. It's no slouch of a job to fit us all out fresh in a few hours. They'd never have done it in the Boer War.'

'My dear chap, the Boer War was child's play compared with this. Willy has set the whole world ablaze. All the same, I agree with you that England is getting her eyes open at last. But it's a pity the people at home didn't realise first off that forcing the Dardanelles was almost as important as keeping the Germans out of Calais. If they'd sent us here two months ago instead of fooling round trying to get warships through the Straits, the job would have been done by now. As it is, they've given the Turks a chance to fortify all the landing places, and I'll bet they've done it too.'

'What sort of landing places are they?' asked Dave.

'Just beaches—little bays with cliffs behind them. And the cliffs are covered with scrub, and so are the hills inland. Ideal ground for the defence, and rotten to attack.'

'You talk as if you'd been there?'

The speaker was a big, good-looking young New Zealander, with a face burnt almost saddle colour by wind and sun. His dark blue eyes gleamed with a merry, devil-may-care expression which took Ken's fancy at once.

'Yes, I've been there,' Ken answered modestly, and was at once surrounded by a crowd all eager for any information he could give. Luckily for him, at that very minute some one shouted.

'We're off, boys. There's the signal to weigh anchor.'

Instantly all was excitement; the cable began to clank home, smoke poured from the funnels, and in a very short time the whole fleet of transports was moving in a long line out of the harbour, escorted by a bevy of busy, black destroyers.

As the Charnwood passed into her place, the men lined the sides and cheered for all they were worth.

'What day is this?' said Ken to Dave, as the big transport passed out of the mouth of the bay.

'Friday, the twenty-third,' was the answer.

'Twenty-third of April,' said Ken. 'St. George's Day. Then I tell you what, Dave, this is going to be a Sunday job.'

'You mean we'll be landed on Sunday?'

Ken nodded.

'That's about it,' he answered.

'HALLO, what's up?' asked Dave Burney. 'We're off again.'

It was the night of Saturday the 24th of April. For the greater part of the day the Charnwood had been lying off Cape Helles, which is the southernmost point of the Gallipoli Peninsula, while the people listened to the thunder of guns, and watched the shrapnel bursting in white puffs over the scrub-clad heights of the land.

Now, about midnight, she had got quietly under way, and was steaming steadily in a nor'-westerly direction.

'What's up?' Dave repeated in a puzzled tone. 'This ain't the way to Constantinople.'

'Don't you be too sure of that, sonny,' remarked Roy Horan, the big New Zealander who was standing with the two chums at the starboard rail. 'We ain't going home anyhow. I'll lay old man Hamilton's got something up his sleeve.'

'That's what I'm asking,' said Dave. 'What's the general up to? So far as I can see, there are only three other transports going our way. The rest are staying right here. What's your notion, Ken?'

'I don't know any more than you chaps,' Ken answered. 'But I'll give you my opinion for what it's worth. I think we're going to do a sort of flank attack. The main landing will probably be down here at the Point. Then when the Turks are busy, trying to hold 'em up, we shall be slipped in somewhere up the coast so as to create a sort of diversion.'

'What—and miss all the fun!' exclaimed Dave in a tone of intense disgust.

'You won't miss anything to signify,' Ken answered dryly. 'There are more than a hundred thousand Turks planted on the Peninsula, and you can bet anything you've got left from the wreck that there isn't one yard of beach that isn't trenched and guarded.'

'Where do ye think we'll land?' asked Horan eagerly.

Ken shrugged his shoulders. 'Haven't a notion,' he said. 'There are a lot of small bays up the west coast. Probably we shall nip into some little cove not very far up. There's a big ridge called Achi Baba which runs right across the Peninsula about four miles north. It'll be somewhere behind that, I expect. But mind you, this is all guess work. I don't know any more than you do.'

'You know the country anyhow,' said Horan. 'And that's worth a bit. See here, Carrington, if we can manage it, let's all three stick together. We ought to see some fun—what?'

Ken laughed. 'I'm sure I'm agreeable. But you see we're not in the same regiment. You're New Zealand, Dave and I are Australians. Still, I dare say we shall all be pretty much bunched when it comes to the fighting.'

Dave, who had been peering out into the night, turned to the others at this moment.

'Yes, there are only four transports altogether in our lot, and so far as I can make out three battleships and four destroyers taking care of us.'

'Now, you men, come below and turn in,' broke in a voice.

It was their sergeant, O'Brien, who had come up behind them.

'Oh, I say, sergeant, can't we stay and look at the pretty scenery?' said Roy Horan plaintively.

'No, ye can't,' was the gruff retort. 'Orders are that all the men are to turn in and take what rest they can. Faith, it's mighty little slape any of ye will get, once you're ashore. Go down now and ate your suppers and rest. I'm thinking ye'll be taking tay with the Turks before you're a dale older.'

'Are we going to land, sergeant?' asked Horan eagerly.

'Am I your general?' retorted O'Brien. 'Get along wid ye, and if ye want to know what it is we're going to do, faith ye'd best go and ask the colonel.'

Orders were orders. The three obediently went below, and, although at first he was too excited to sleep, Ken soon dropped off, and never moved until he felt a hand shaking him by the shoulder.

'Up wid ye, lad,' said O'Brien's voice in his ear, and like a shot Ken was out of his blanket and on his feet.

The screw had ceased to revolve. The ship lay quiet, rocking ever so lightly in the small swell. There was not a light to be seen anywhere, yet all was bustle, and the very air seemed charged with a curious thrill of excitement.

According to orders, Ken had lain down, fully dressed, with all his kit ready beside him. Within a very few moments he was equipped and ready. Then he and his companions were ordered down to the lower deck where the electrics were still burning, and there hot coffee and bread and butter were served out. Also each man received rations for twenty-four hours.

Officers passed among the men, scrutinising their equipment with keen eyes, and presently Colonel Conway himself came along.

He glanced round and his eyes kindled as they rested on the ranks of long, lean colonials.

'Men,' he said, and though he hardly raised his voice it carried to the very ends of the big flat. 'You know as well as I do what you have been training for during the past six months. The day you have been waiting for has come. See that you make the most of it. Speed and silence—these are the qualities required of you to-night. The boats are waiting.'

Ken repressed with difficulty a violent desire to cheer. Next moment came a low-voiced order from his company commander, and he found himself one of a long line hurrying up the companion to the deck.

There was no moon, but the stars were bright, and it was not too dark to see the cliffs that seemed to rise abruptly out of the sea, about half a mile away to the eastward. They, like the ships, were dark and silent.

Without one unnecessary word, the troops dropped quietly down the ladder into the waiting boats, and presently were being pulled rapidly inshore. Boat after boat came stealing out of the gloom, all loaded down to the gunwales with fighting men, yet all moving with a silence that was positively uncanny. The oars were carefully muffled and no one spoke aloud.

Dave sat next to Ken, but Horan was not with them. He had been ordered into another boat with his company.

Dave put his mouth close to Ken's ear.

'Don't believe there's a Turk in the country,' he muttered. 'Looks to me as peaceful as a picnic.'

'Looks are precious deceitful sometimes,' Ken whispered back. 'For all you or I know, that brush is stiff with the enemy.'

'Then why don't they fire at us?'

'A fat lot of good that would be in this light. No, Dave, they know their job as well as we do, and perhaps better. I shall be pleasantly surprised if we're allowed to land without opposition.'

But the boat neared the shore, and still there was no sign from those silent cliffs and thickets. As soon as her bow grated on the shingle, the men were out of her, wading knee deep to the shore. They were as eager as terriers. The only anxiety of their officers was lest they should get out of hand and start before the order to advance was given.

Boat after boat glided up, and men by scores formed up at high tide mark.

'Told you we'd fooled 'em,' whispered Dave. 'This is going to be one o' your bloodless victories.'

The words were hardly out of his mouth before there was a loud hissing sound, and right out of the centre of the precipitous slope facing them something like a gigantic rocket shot high into the air and burst into a brilliant white flame.

It lit up the whole beach like day, throwing up the long lines of troops in brilliant relief. Next instant there was a crash of musketry, and rifles spat fire and lead from a long semicircle behind the spot from which the star shell had risen.

The man next but one to Ken threw up his arms and dropped without a sound. A score of others fell.

'Gee, but you were right, Ken!' muttered Dave. 'Fix bayonets!' Colonel Conway's voice rang like a trumpet above the crackle of the firing.

Instantly came the clang of steel as the bayonets slipped into their sockets. Men were falling fast, but the rest stood straining forward like greyhounds on a leash.

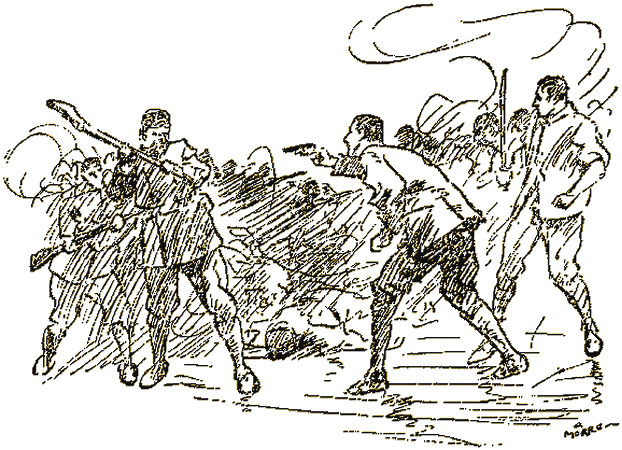

'Not a shot, mind you. Give 'em the steel. At the double. Advance!'

Almost before the words were out of his mouth the whole line rushed forward. A second star shell hissed skywards, but before it broke the men had reached the base of the cliff. Its white glare showed the long-legged athletes from the sheep ranges and cattle runs sprinting up the steep hill-side.

The enemy rifles rattled in one long, terrible roll. Men dropped by dozens and scores. Some fell where they lay, others rolled helplessly back down the steep slope to the beach. But those left never paused or hesitated. They scrambled desperately upwards through the pelting storm of lead, guided by the flashes from the muzzles of the Turkish rifles.

Ken was conscious of nothing but a fierce desire to get to close quarters, and he and Dave Burney went up side by side at the very top of their speed.

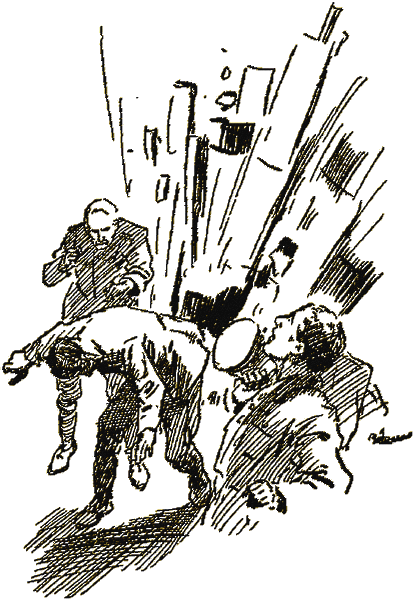

Before they knew it, a dark hollow loomed before them. A rifle snapped almost in Ken's face—so close that he felt the scorch of the powder. Without an instant's hesitation he drove his bayonet at a dark figure beneath him, at the same time springing down into the trench. The whole weight of his body was behind his thrust, and the Turk, spitted like a fowl, fell dead beneath him.

He drove his bayonet at a dark figure.

With an effort he dragged the blade loose. Only just in time, for a burly man in a fez was swinging at his head with a rifle butt. Ken ducked under his arm, turned smartly and bayoneted him in the side.

The whole trench was full of struggling men. The Turks fought well, but good men as they are, they were no match for the long, lean six footers who were upon them. Inside three minutes it was all over. Most of the Turks were dead, the few survivors were prisoners.

'Lively while it lasted,' panted Dave's voice at Ken's elbow.

'You, Dave. Are you all right?'

'Lost my hat and my wind. Nothing else missing so far as I know. Are you chipped?'

'Not a touch. But keep your head down. This is only the first act. There's another trench above this one.'

During the struggle in the trench the firing had ceased entirely, but now that it was over a pestilence of bullets began to pour again from higher up the slope, and Ken's warning was useful—to say the least of it.

'What comes next?' asked Dave, as the two crouched together against the rubbly wall of the trench.

'Get our second wind and tackle the next trench,' said Ken briefly.

His prophecy was correct. A couple of minutes later the order was passed down to advance again.

In grim silence the men sprang out of their shelter and dashed forward. There were no more star shells, but from up above began the ugly knocking of a quick-firer. It sounded like a giant running a stick along an endless row of palings, and the bullets squirted like water from a hose through the thinning ranks of the Colonials.

It was worse than the first charge, for not only was the slope steeper, but the face of the hill was covered with low, tough scrub, the tangled roots of which caught the men's feet as they ran, and brought many down. The result was that the line was no longer level. Some got far ahead of the others.

Among the leaders were Ken and Dave, who struggled along, side by side, still untouched amid the pelting storm of lead.

But although the ranks were sadly thinned, the attackers were not to be denied. In a living torrent, they poured into the second trench.

There followed a grim five minutes. The Turks who were in considerable force, made a strong effort to hold their ground, shortening their bayonets and stabbing upwards at the attackers. It was useless. The Australians and New Zealanders, savage at the loss of so many of their comrades, fought like furies. Ken had a glimpse of a giant next him, literally pitchforking a Turk out of the trench, lifting him like a gaffed salmon on the end of his bayonet.

It was soon over, but this time there were very few prisoners. Almost every man in the trench, with the exception of about a dozen who had bolted at the first onset, was killed.

'That's settled it,' said Dave gleefully, as he plunged his bayonet into the earth to clean it from the ugly stains which darkened the steel.

'That's begun it,' corrected Ken.

'What do you mean?'

'That we've got to hold what we've won. You don't suppose the Turks are going to leave us in peaceful possession, do you?'

'I—I thought we'd finished this little lot,' said Dave rather ruefully.

'My dear chap, I've told you already that Enver Bey has at least a hundred thousand men on the Peninsula. By this time the news of our landing has been telephoned all over the shop, and reinforcements are coming up full tilt. There'll be a couple of battalions or more on the top of the cliff in an hour or two's time.'

'Then why don't we shove along and take up our position on the top?'

'We're not strong enough yet. We must wait for reinforcements. If I'm not mistaken the next orders will be to dig ourselves in.'

'But we are dug in. We hold the trench.'

'Fat lot of use that is in its present condition. All the earthworks are on the seaward side. We have little or no protection on the land side.

'Ah, I thought so,' he continued, as the voice of Sergeant O'Brien made itself heard.

'Dig, lads! dig! Make yourselves some head cover. They'll be turning guns on us an' blowing blazes out of us as soon as the day dawns.'

Blown and weary as they were, the men set to work at once with their entrenching spades. It was in Egypt they had learnt the art of trench-making, but they found this rocky clay very different stuff to shift from desert sand.

The order came none too soon, for in a very few minutes snipers got to work again. There were scores of them. Every little patch of scrub held its sharpshooter, and although the darkness was still against accurate shooting there were many casualties.

'They're enfilading us,' said Ken. 'They've got men posted up on the cliff to the left who can fire right down this trench. It's going to be awkward when daylight comes.'

It was awkward enough already. The Red Cross men were kept busy, staggering away downhill with stretchers laden with the wounded. There was no possibility of returning the enemy's fire, and in the darkness the ships could not help. All the Colonials could do was to crouch as low as possible, flattening themselves against the landward wall of the trench.

'Those snipers are the very deuce, sergeant.'

The voice was that of Colonel Conway, who was making his way down the trench, to see how his men were faring.

'They are that, sorr,' replied O'Brien. ''Tis them over on the bluff to the left as is doing the damage. I'm thinking they've got the ranges beforehand.

As he spoke a man went down within five yards of where he stood. He was shot clean through the head.

'It's Standish,' said Ken. And then, on the spur of the moment,—

'Sergeant, couldn't some of us go and clear them out?'

There was a moment's pause broken only by the intermittent crackle of firing from above.

'Who was that spoke?' demanded Colonel Conway.

'I, sir,' answered Ken, saluting. 'Carrington.'

'Aren't you the man who knows this country?'

'I have been in the Peninsula before, sir.'

'Hm, and do you think you could find those snipers?'

'I do, sir.' Ken spoke very quietly, but inwardly he was trembling with eagerness. Was it possible that his impulsive remark was going to be taken up in earnest?

The colonel spoke in a whisper to O'Brien, and the sergeant answered. Then he turned to Ken.

'You may pick three men and try it. You'll have to stalk them, of course. If you can't reach them come back. No one will think any the worse of you if you fail.'

'Thank you, sir,' said Ken, his heart almost bursting with gratitude. His chance had come, and he meant to make the most of it.

'DAVE, will you come?' said Ken.

'Will a terrier hunt rats?' was Dave's answer.

'And I want Roy Horan, sergeant, if he's alive. He's a New Zealander.'

'Pass the word for Horan,' said the sergeant, and the whisper went rapidly down the long trench.

'Who'll be the fourth?' Ken asked of Dave.

'Take Dick Norton. He's a Queensland ex-trooper. He's been in with the black trackers, and moves like a dingo.'

'The very man,' said Ken. 'Where is he?'

Norton, as it happened, was only a few yards away. He came up eagerly, a slim, dark man with keen gray eyes and a nose like a hawk's beak.

A moment later, and Roy Horan's giant form came slipping rapidly up to the little group, and Ken at once explained what was wanted.

'Carrington, you're an angel in khaki,' said Horan rejoicingly. 'I'm your debtor for life.'

'Which same will not be a long one if ye don't kape that big body o'yours under cover,' said O'Brien dryly, as a bullet, striking the parapet, spattered earth all over them.

'Have ye revolvers?' he asked of Ken.

None of them had, but these were at once provided, together with plenty of ammunition.

'Ye'd best lave your rifles,' said O'Brien. ''Tis a creeping, crawling job before ye, and the lighter ye go, the better. At close quarters the pistols will do the job better than anything else ye can carry. Now get along wid ye. The sky's lightening over Asia yonder, and 'tis small chance ye'll have if the dawn catches ye.'

'Lucky beggars!' growled a big Tasmanian, as they passed him on their way to the north end of the trench. All their comrades were consumed with envy, but like the good fellows they were, they only wished them luck.

A few moments later they had all four crawled out of the trench, and bending double were making steadily uphill towards the spot from which the enfilading fire proceeded.

'We'll go straight,' whispered Ken. 'Less risk, really, for they'll be shooting over our heads.'

There was plenty of cover, for the whole of the steep hillside was dotted with thick bunches of dense scrub. Barring a chance shot from up above, there was not much risk for the present. That would come later, when they reached the nest of snipers. For the present the great thing was to keep their heads down and escape observation.

Nearer and nearer they came to the spot whence the flashes darted thickest, and all the time the bullets whirred over their heads. At last Ken was able to see through the gloom a low parapet of earth which was evidently the front of a regular rifle pit.

He stopped and beckoned to the others to do the same.

'There must be at least half a dozen of them,' he whispered, 'and very likely more. You chaps wait here under this bush while I go forward. No, you needn't grouse, Dave. I'm not going to do you out of your share. All I want is to make out which side it will be best to make our attack. I'll be back in a minute.'

He crept forward, and as he did so there was a sudden lull in the firing. For a moment he feared that the men in the pit had spotted him or his companions, and he flattened himself breathlessly on the ground.

Next moment he heard a voice. Some one in the rifle pit was speaking.

'I would that they would hasten with that ammunition,' said the man speaking in the Anatolian dialect, which Ken could understand fairly well. 'Allah, but these infidels take lead as though it were no more than water!'

'They are brave men, Achmet,' answered another, 'but even so they will not stand when Mahmoud brings up the guns. Then, as the German says, we shall sweep them back into the sea from which they came.'

'Guns!' muttered Ken. 'This is news.' He lay still and listened eagerly.

'Does the German himself bring the guns?' asked the first speaker.

'He does, brother. They are two of the best which were sent from Constantinople to Maidos. Most like, they are already in position on the heights above us, ready to rain their shrapnel upon the unbelievers.'

Ken had heard enough. This was news which the colonel must learn at once. Snipers were bad enough, but if the two German 77-millimetre field-pieces were got into position, the trench would be untenable. He waited only long enough to get the lie of the land around the rifle pit, then crept quietly back to his companions.

It took him just about thirty seconds to tell them what he had heard.

'And one of you must go back and tell the colonel,' he added.

There was silence. Not unnaturally no one volunteered.

'It's up to you, Norton,' said Ken.

'Why not rush the pit first?' suggested Norton, 'then we could all go back together.'

'Or all stay here,' answered Ken. 'No, I'm frightfully sorry, Norton, but you're the best scout of the lot of us, and the most likely to get back safely. You must go and tell the colonel.'

Norton was too good a soldier to argue. With a sigh he turned about and vanished in the gloom.

'And now for the rifle pit,' said Ken. 'We must go up on the right-hand side, and take it from the rear. As I've told you, the fellows holding it are out of cartridges. If we can get in on 'em quietly, before they can use their bayonets, we ought not to have much trouble.'

Ken's heart beat hard as he led the way to the rifle pit. The thought that his colonel had given him a job on his own filled him with pride, and though he was nothing but a private leading two other privates, he felt like a captain with a company behind him.

The critical moment came as they reached the front of the pit, and had to swing off to the right. There was little or no cover, and it was necessary to crawl flat on their stomachs. To make matters worse, the ground was rough and stony, and every time a pebble rolled, Ken's heart was in his mouth.

But the snipers were keeping no sort of watch. Of course none of them had the faintest notion that any enemy was nearer than the trench, quite a couple of hundred yards away. As they snaked along, the attacking party could hear them talking in the low, measured tones peculiar to the Turk.

At last Ken gained his vantage point. He paused and drew his revolver. The others did the same.

Ken sprang to his feet, and with two bounds was in the pit.

There were five men there, and the attack took them utterly by surprise. Before they knew what was happening two were pistolled and one knocked silly by a blow from the butt of Horan's revolver. The two others fought gamely, but they were no match for the three Britishers. In less time than it takes to tell they were both laid out.

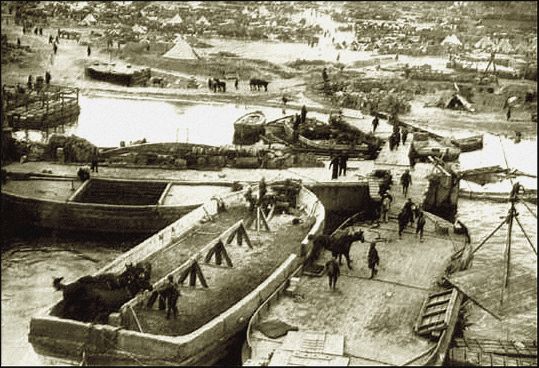

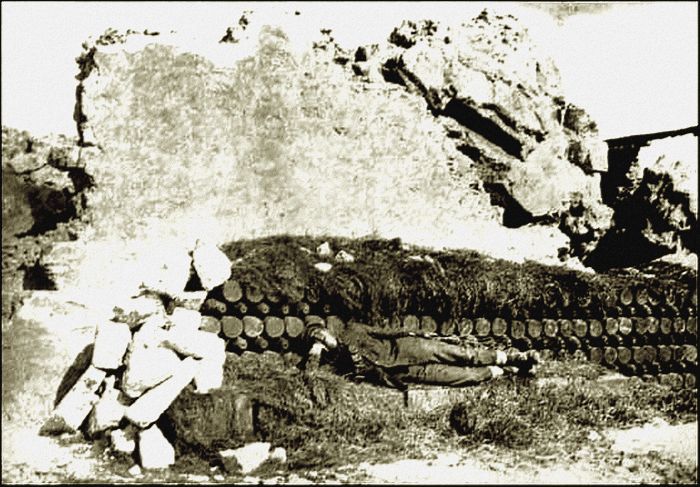

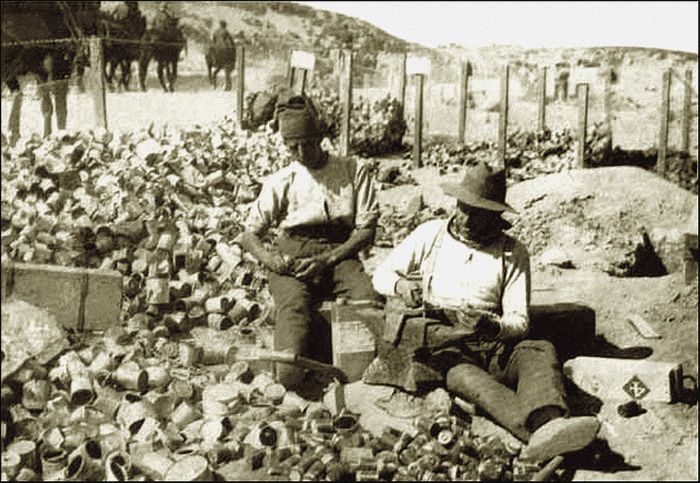

Stores, horses, and munitions were being landed on V. beach.

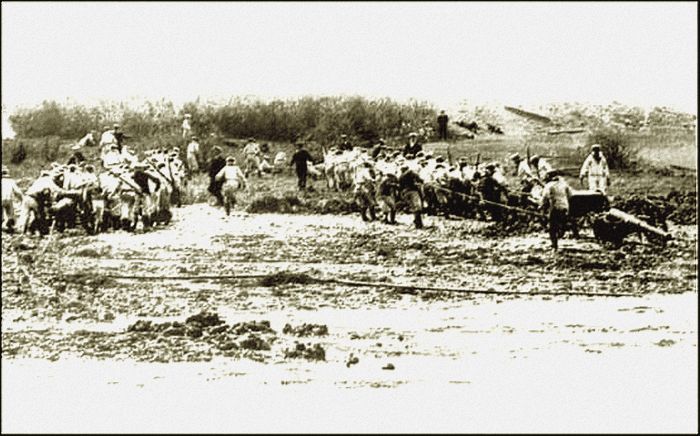

Magnificent work was done by the landing parties in their advance inland.

'Hurrah!' cried Horan gleefully.

'Shut up, you ass!' snapped Ken. 'Do you want to bring every Turk within half a mile down on us. Look out. There's one chap moving. Tie him up, and, Dave, gather their rifles. I must go through their pockets. There's always a chance of useful information.'

'Lively now!' he added. 'They were expecting ammunition, and we shall have visitors in pretty short order.'

'My word, here they are already,' muttered Dave Burney. 'Half a dozen of 'em.'

Ken looked up quickly. A number of figures were just visible, coming along the ridge to the right.

'There are more than half a dozen,' he whispered sharply. 'More like double that number. And that looks like an officer with them.'

'We'd best make ourselves scarce,' suggested Dave quietly.

'Too late for that,' answered Ken. 'They're bound to see us. Besides, if they find the pit empty they'll only put fresh men here, and all the work will be to do again.'

'Let's tackle 'em then,' said Roy Horan recklessly.

'Odds are too long,' replied Ken. He paused a moment, and glanced round.

'I've an idea,' he said swiftly. 'I believe we can fool them. Quick! Take the coats off the dead men, and put them on. Their fezes, too. In this light they'll never know the difference.'

'But if they talk to us?' objected Roy.

'Then I'll talk back. I know the language.'

As he spoke, Ken was swiftly stripping one of the dead Turks of his overcoat. The others did the same, and within an incredibly short time all three were wearing dead men's clothes. The coats sat oddly on their long frames, but fortunately there was as yet very little light, and in the gray gloom they presented a tolerable resemblance to the late tenants of the rifle pit.

They had hardly completed the change when the officer who was leading the party reached the edge of the pit.

'Why are you not firing?' he demanded, and by his harsh guttural voice Ken knew him at once for a German.

'We are out of ammunition,' he answered readily.

'Schweinehund! Do you not know enough to say "Sir" to an officer when he addresses you?'

'Your pardon, sir,' said Ken gruffly. 'The light is so bad, and my eyes sting with the powder smoke.'

'They will sting worse if you do not mend your manners,' retorted the German brutally.

Ken, boiling inwardly, had yet wisdom enough to hang his head and make no reply.

'How many are there of you in the pit?' continued the officer.

'How many are there of you in the pit?'

'Only three, sir,' Ken answered.

'You will retire to higher ground and construct a new pit. This position is required for a mitrailleuse. You understand, blockhead?'

'Yes, sir.'

The officer turned to the men behind him.

'Bring up the gun,' he ordered.

'Come on,' said Ken to Dave in the lowest possible whisper. He climbed quietly out of the hollow as he spoke, and the two others followed.

'Up the hill there—by those bushes,' said the German curtly. 'And be sharp. Ammunition will be brought you. Understand, your work is to command the beach and prevent supplies being brought to those dogs in the trenches.'

'So that's the little game, is it?' said Roy, as the three gained the shelter of a patch of scrub out of sight of the German. 'A quick firer to enfilade the trench, and snipers for the beach. Say, Carrington, can't we do anything to put the hat on that Prussian Johnny's scheme?'

'We've got to,' Ken answered quickly. 'Once they get that quick-firer posted, it's all up with our lads down below. They'll rake the trench from end to end.'

'Let's wait till it's in place, and rush it,' suggested Horan recklessly. 'We ought to be able to wipe out the gun crew before they nobble us.'

'What's the use of that?' retorted Ken. 'It's the gun itself we want to wreck—not the crew. They can easily get a score of men to work the Q.-F., but it would take some time to get another gun. Jove, if I only had just one stick of dynamite.'

'But they had no dynamite, and the outlook seemed extremely gloomy. Worst of all, it was rapidly getting light, and although a mist hung over the sea and the shore, this would no doubt melt away as soon as the sun was well up.

Shots came from a patch of scrub behind and above them, whistling over their heads, and evidently directed at the boats which were bringing ammunition and reinforcements from the ships.

Ken crouched lower, and as he did so some bulky object in the pocket of the Turkish overcoat which he was wearing made itself felt. He slipped his hand in and drew out a black metal globe, about the size of a cricket ball. It had a length of dark cord-like stuff projecting from a hole in it.

It was all he could do to repress a yell of delight.

'What luck!' he muttered. 'Oh, I say, what luck!'

'What the mischief have you got there?' inquired Dave. 'What is it?'

'A bomb. One of the German hand grenades. Quick! See if there are any in your pockets?'

Hastily the others thrust their hands into their pockets and each hand came back with a similar bomb.

'That settles it,' said Ken happily. 'Two for the men, and one for the gun. We've got 'em now—got 'em on toast.'

As he spoke he crept out of the bush, and took a cautious peep in the direction of the rifle pit.

'They're just setting the gun up,' he muttered. 'And the German beggar has gone back the way he came. So far as I can see, there are not more than four or five men with the gun.'

'That's all right,' said Roy Horan in a tone of considerable satisfaction. 'What do we do, Carrington—just wallop these grenades in on top of 'em?'

'No, they're not percussion—worse luck! We've got to light the fuses before we chuck them. That's awkward for two reasons. They may see our matches, and then we've got to be pretty nippy about using them. If we're not, it's we who'll get the bust up—not the Turks.'

'Sounds, interesting,' remarked Roy coolly. 'See here, Carrington, the best thing, so far as I can see, is for us to slip down to our old place, right under the parapet of the pit. That's our only chance of getting to close quarters.'

'A frontal attack,' put in Dave. 'What price our heads if they start shooting off the gun?'

'They probably won't start until they have light enough to see where they're shooting,' returned Ken. 'Horan's notion is all right. Come on.'

'But mind you,' he whispered urgently, 'we must keep one bomb for the gun. You'd best throw yours first, Horan, and as soon as it's gone off, let 'em have it with your pistol. Then, if there are any of 'em left, you whack yours in, Dave.'

He crept away, the others followed, and a few moments later they found themselves crouching close together under the low parapet of the rifle pit. There was light enough for them to see—just above their heads—the ugly gray muzzle of the mitrailleuse peeping out through an embrasure in the earthen bank.

All of a sudden, without the slightest warning, a tongue of flame spat from the muzzle, and with a deafening rattle a hail of bullets sprayed out over their heads, directed at the trench a bare two hundreds yards away.

'Quick!' cried Ken. 'We must stop that,' and with all speed he pulled out his match-box. The crackle of the firing drowned his words, but that did not matter. The others understood.

Ken struck a match, and Roy held out the fuse of his bomb. Luckily there was no wind. The fuse caught and instantly began to hiss and splutter.

With reckless disregard for danger, Roy sprang upon the parapet. Ken had one glimpse of the tall figure towering over him, one hand raised high overhead.

Then the arm flashed forward as Roy dashed the grenade full into the centre of the pit.

There followed a stunning report—a noise so loud that Ken felt as though his very ear-drums were cracked. At the same time Horan staggered back off the parapet, and the quick-firer ceased firing.

'Now, yours, Dave,' said Ken, and without delay Dave lobbed his grenade, the fuse of which Ken had already lighted, into the pit.

But by this time the survivors from the first explosion had pulled themselves together and collected their wits. Before the second grenade could explode, it was hurled back. It went right over Dave's head and rolling down the hill exploded with a deafening roar.

On top of the grenade three burly Turks came leaping out of the pit and fell on Ken and Dave.

Ken just managed to get out his pistol in time, and his first shot finished the leader of the three Turks. But a second man came at him with a clubbed musket, and Ken only saved his skull by a rapid duck.

'Dog!' roared his assailant, as he made another savage swing.

Ken leaped away, and the Turk overbalanced himself with the force of his blow. Before he could recover Ken's heavy revolver barrel crashed upon his skull and felled him like a log.

Ken glanced across at Dave, and saw him kneeling on the chest of the third Turk, his long fingers gripping the man's throat. Just beyond, Roy, recovering slowly from the stunning effect of his own bomb, was scrambling dazedly to his feet.

Farther off, he heard the sound of running feet. It was clear that the sound of the two explosions had aroused the suspicions of some supporting party. Reinforcements were coming up at the double.

If the gun was to be put out of service this would have to be done quickly. Without a moment's delay he sprang over into the pit.

The place was a regular shambles. Ken was amazed at the ruin wrought by the one small bomb. Three men lay dead in the bottom. One had his head almost blown off. Fortunately, perhaps, Ken had no time to dwell on such horrors. With all possible speed he got the remaining bomb out, and with a handkerchief tied it to the breech of the quick-firer.

Then he lighted the fuse, and waiting only long enough to see that it was burning properly, made a wild leap out of the pit.

'It's all right. I've fixed the gun. Come on, you chaps,' he said sharply to the others.

The words were hardly out of his mouth before a flash of flame rose from the pit and the loud report of the last bomb sent the echoes flying along the cliffs. Fragments of the broken gun shot high into the air, the pieces falling in every direction.

'That's done the trick,' said Dave gleefully.

'Don't talk. Come on. There's a big party of Turks coming up. Are you game to run, Horan?'

'You bet. I'm all right now. But those bombs are oners. I never reckoned such a small thing would make such a dust up. Gosh, it nearly blinded me, and my head still rings like a bell.'

Ken did not answer. All his energies were needed to steer a course through the scrub which covered the steep hill-side. The morning mist lay thick and clammy. It was impossible to see more than a few yards ahead, and it would be the easiest thing in the world to miss the way back to the trench, and either go over the steep edge to the beach or get in among the enemy snipers to the left.

'Look out!' cried Roy Horan suddenly, and as he spoke four men rose up out of the thick scrub right in their path. And one of them was a German officer, the very same whom they had encountered twenty minutes earlier.

'Stop!' he snarled. 'Stop, you fools. Where are you going?'

THE officer was armed with a repeating pistol while his men all had rifles. For the moment Ken was filled with wonder as to why they had not at once used their weapons.

Then he remembered. It was their Turkish greatcoats which had saved them. In the dim light the German still took them for Turkish soldiers.

But discovery could only be a matter of a few seconds. Even as he watched, he saw suspicion dawn in the pig-like eyes of the Prussian.

'At 'em!' roared Ken, and without an instant's hesitation flung himself upon the officer.

The man tried to fire, but Ken caught his wrist in time, and closed. The two wrestled furiously together, the German breathing out savage threats in his own language.

He was not tall, but a stocky, powerful man, and it was all Ken could do to hold his own. Vaguely he heard shouts and shots, and knew that Dave and Roy were hotly engaged with the three Turks. But he had no attention to spare for them. All his energies were needed to cope with his own opponent.

Ken's first object was to deprive the other of his pistol, and he forced the man's right arm back with all his strength. Stamping and panting, the two worked gradually back down the slope until they had passed the clump of scrub from behind which the German had appeared.

Ken, though breathing hard, was still cool and collected, while the German, on the other hand, had utterly lost his temper. His big heavy face was a rich plum colour, and the breath whistled through his teeth.

At last Ken gained his first object. His fierce grip upon the German's wrist paralysed the muscles of the man's hand, and the pistol dropped from his nerveless fingers.

Instantly Ken tightened his hold, and tried to back-heel his adversary. Before he could succeed in this manoeuvre, he felt the ground crumbling beneath his feet.

It was too late to do anything to save himself. Next moment the earth gave way and he and the German, locked in one another's arms, went flying through the air.

Followed a crash and a thud, and for some moments Ken lay stunned and breathless, though not actually insensible.

In boxing there is nothing more painful than a blow on the 'mark.' It knocks all the breath out of the body, and for some time the lungs seem paralysed. This was practically what had happened to Ken. He had fallen full on his chest, and though his senses remained clear enough, he simply could not get his breath back.

When at last he succeeded in doing so he felt as weak as a cat, and deadly sick into the bargain. It was some moments before he could even manage to roll off the body of the man beneath him.

He struggled to his feet and found that he was at the bottom of a bluff about twenty feet high. To the right was a sheer drop to the sea. He shivered as he glanced over to the fog-shrouded waves, full eighty feet below. The ledge on which he had landed was only four or five yards wide. A very little more, and he and his enemy together must have gone clean over the cliff.

He turned to the German. The latter lay still enough—so still that at first Ken thought he was dead. But presently he saw that the man was still breathing.

'A hospital case,' muttered Ken in puzzled tones. 'What the mischief am I to do with him?'

'Ken—Ken, where are you?'

The anxious question came from overhead, and glancing up Ken saw Dave Burney's head appearing over the edge of the bluff.

'I'm all right,' he answered. 'What about you?'

'We've nobbled our little lot,' Dave answered with justifiable pride. 'My word, but I'm glad to see you. I thought you'd gone right over into the sea.'

'I wasn't far off it,' said Ken. 'I say, is there any way up to the top again. This is nothing but a ledge?'

'Can't you climb the bluff. It's not so steep a little way to your right?'

'I could, but my German friend isn't exactly in climbing trim. He's rather badly bust up by the look of him.'

'My German friend isn't exactly in climbing trim.'

Dave glanced round.

'It looks to me as if the ledge you're on broadens a good bit to my left. You wait where you are, and Roy and I will come round and give you a hand.'

Dave's head disappeared, and Ken sat down, with his back against the bluff. He had had a bad shake up, and was glad of a few moments' rest. He was quite safe where he was, for the bluff protected him from stray Turkish bullets.

Down below, through the mist, boats were shooting landwards from the transports, bringing more men, stores of all kinds, ammunition, and materials for setting up a wireless installation. He saw that they were under constant fire from the snipers on the cliffs above, and though for the moment the haze protected them, the mist was fast rising. It was going to be precious awkward when the full light came.

In a much shorter time than he had expected, his two companions appeared in sight around the curve of the ledge. In the dawn light he could see that their khaki was torn and covered with stains, while their faces were scratched and bleeding. But both were in splendid spirits.

'My word!' exclaimed Roy. 'This is what you might call a night out with a vengeance.'

'The night's all right,' returned Ken, 'but it's getting a jolly sight too near day to suit me. If we don't get back to our trench before this fog goes we shall be a target for half the Turkish army.'

'It's not far,' said Dave consolingly.

'Far enough, by the time we've carried in this Johnny,' replied Ken, pointing to the German.

Dave looked doubtfully at the corpulent form of the Prussian.

'He's not exactly a featherweight, by the look of him. However, here goes.' He stooped as he spoke and took the officer by the shoulders.

'Catch hold of his legs, Roy,' he said to Horan. 'No, Ken,' as Carrington stepped forward, 'you've done your bit. Roy and I will tote your stout prisoner back.'

'First, take off those Turkey carpets you're wearing,' said Ken quickly. 'If you don't, it's our chaps will fill you with lead.'

They all peeled off their Turkish overcoats, then carrying the German they started along the ledge. Rounding the curve, Ken found that the ledge widened and merged in the scrub-clad slope opposite the head of the little bay.

He stopped and glanced round. The Turkish snipers were still busy, and the sharp crack of cordite echoed from scores of different hiding-places along the hills. He and his companions had about one hundred and fifty yards to go before reaching the trench held by their battalions, and the light was growing stronger every moment.

In spite of his anxiety to bring in his prisoner, it seemed clear that the risk was too great. Their only chance of crossing the open in safety was to duck and crawl.

'It's no use,' he said regretfully. 'We'll have to leave this chap behind. We'll all be shot as full of holes as a sieve if we try to carry him.'

'Rats, Carrington!' retorted Roy Horan. 'Go home without our prisoner? Never! Besides, the Turks won't shoot their own officer. Come on, Dave,' he said, and before Ken could say another word the two were off as hard as they could go, carrying their heavy burden.

Ken had many doubts as to the Turks refraining from shooting, for fear of hitting the German. In fact, knowing as he did the feeling which existed between the bullying Prussian and the placid Turk, he rather thought the case would be exactly the opposite.

Whatever the reason, at any rate they had covered nearly half the distance before they began to draw fire. Then bullets began to ping ominously close, and little jets of dust to rise from the dry soil all around them.

Suddenly Ken's hat flew from his head, and as he stooped quickly to recover it, the fat German gave a yell like a stuck pig, and kicked out so convulsively that his bearers incontinently dropped him.

In an instant he was on his feet, and running like a rabbit, at the same time giving vent to a series of sharp yelps like a beaten puppy.

'The blighter! He was shamming!' roared Roy, darting off in pursuit, regardless of the bullets.

'It was a bullet woke him up anyhow,' exclaimed Dave, as he scurried after.

The Prussian was beside himself with pain. He had been shot through one hand, and there is no more agonising injury. He ran blindly, and as it chanced almost in a straight line for the trench.

A score of heads popped up to see what was happening, and when their owners realised the truth a roar of laughter burst out all down the trench.

It was not until the German was on the very edge of the trench that he realised where he was. He spun round to bolt.

But Roy was at his heels.

'No, ye don't, fatty,' said the big New Zealander, and catching the man by the scruff of the neck, gave him a tremendous push which sent him flying over into the trench. Roy sprang down after him, and a moment later, Dave and Ken hurled themselves into cover.

'Is it steeplechasing ye are, or what fool's game is it ye are playing?' demanded Sergeant O'Brien, while the rest shrieked with laughter.

'He—he's my prisoner,' panted Ken. 'And—and, sergeant, did Norton get back?'

'He did. Come along wid ye, and make your report to the colonel.'

Colonel Conway, who had been on foot all night, was taking a few minutes' much needed rest in a rough dug-out. But at sight of Ken, he was on his feet again in a moment.

'I am very glad to see you, Carrington,' he said cordially. 'I had begun to be afraid that you and your companions would not get back. And yet I knew you had succeeded in your enterprise, for the enfilading fire ceased very shortly after you left.'

Standing at attention, Ken gave his report. He made much of the doings of Dave and Roy, but modestly suppressed his own. The colonel, however, was not deceived.

'You have done very well indeed,' he said, with a warmth that brought the colour to Ken's cheeks. 'Your destruction of the machine gun was a particularly plucky and useful piece of work. I shall see that your conduct and that of all your companions is mentioned in the proper quarter. Meantime, you are promoted to corporal.'

Ken's heart was very nearly bursting with pride.

'Thank you, sir,' he said with a gulp, and saluting again turned away.

The colonel stopped him.

'You had better get some food,' he said. 'We shall be moving out of this very shortly.'

'Faith, ye didn't do so badly after all, lad,' said O'Brien. 'Ate quickly now, for I'm thinking 'tis us for the top of the cliff before we're a dale older.'

Bread, bully beef, and a drink of water out of their bottles. That was the simple bill of fare. But Ken's exertions during the night had put a sharp edge on his appetite, and he enjoyed the plain meal.

The fog was fast disappearing under the rays of the newly risen sun, and the firing grew heavier every minute. The hills all round were alive with snipers, but their fire was directed not so much on the trench held by the Australians as on the boats which were landing reinforcements on the beach below.

It was in the boats and on the beach that the casualties were heaviest. The troops that were landed had to run the gauntlet for fully fifty yards before reaching the cover of the scrub on the cliff, and matters were worse still for the bluejackets pulling the empty boats back to the ships. They were potted at without a chance of returning the enemy fire.

But they stuck it out finely, and already all the wounded had been taken off, while reinforcements had reached the upper trench, sufficient in number to make up for the first losses.

'What's the colonel waiting for?' asked Dave. 'Why don't we go on up and smoke out those blighted snipers?'

'It's ammunition, I fancy. And there's a couple of maxims coming up. We shall need those if we have to dig ourselves in under fire.'

'More digging—oh, Christmas!' growled Dave. 'I didn't come here to dig. I could do that in my old dad's garden at home.'

Ken chuckled. 'You'll find the spade'll do as much to win this war as the guns and rifles. There's heaps of trenching in store for us, I can tell you.'

There was some delay about the maxims, and time went on without any order to move. The men began to grumble. It was hard indeed to lie and watch their comrades below being picked off, one after another, by these abominable sharpshooters, without a chance of hitting back.

'Look at that!' growled Roy Horan, pointing to a stalwart bluejacket who had just dropped at his oar as the boat pushed off the beach. 'It's murder! That's what it is. Sheer murder! Why the blazes can't the ships turn loose?'

'Because they've got nothing to fire at. You can't chuck away 6-inch shells on the off chance of killing one sniper. You wait until the Turks appear in force. Then you'll see what naval guns can do.'

'I don't believe the swine will ever appear in force,' said Roy, who had lost all his good humour and was looking absolutely savage. 'It breaks me all up to see our chaps shot down like rabbits without a chance of getting their own back.'

There was worse to come. From somewhere high up among the scrub-clad heights came a dull heavy crash, and almost instantly the clear air above the beach was filled with puffs of gray white smoke which floated like balls of cotton wool.

'The guns! The beggars have got those guns up,' ran a mutter along the trench.

'About time for the ships to get to work,' growled Roy, his big handsome face knitted in a scowl.

'Ay, if they only knew where the guns were,' replied Ken. 'But that's the deuce of it. They can't spot 'em without planes, and there are no planes here yet.'

Crash! A second gun spoke, and another shell burst above the beach. From that time on the firing was continuous. The whole beach was scourged with shrapnel, and landing operations became perilous in the extreme.

The men in the trenches fidgeted and swore beneath their breath. There is nothing more trying to troops than to see their comrades suffering and yet be unable to help them.

'Can't we do something?' muttered Dave, as he saw a boat from one of the ships smashed to matchwood by a blast of shrapnel, and her crew and contents scattered into the sea. 'Can't we do something? It's enough to drive one loony to watch this sort of thing.'

Almost as he spoke there was a sudden flutter of excitement, as an order was passed from man to man down the trench.

They were to advance and take up a new position on the top of the slope.

THERE was no bugle note, no cheer, but at a whistle the men swarmed out of their trench and went uphill as hard as every they could go.

Their appearance was the signal for a tremendous outburst of firing on the part of the Turkish snipers, and a moment later the two 77-millimetre German guns which had been brought from Gaba Tepe changed the direction of their fire from the beach to the advancing troops.

As the Australians went bursting through the scrub, snipers who had crept in close during the night and hidden in the bushes and behind rocks broke like rabbits out of gorse when the terriers are put in.

They were hunted down remorselessly, and not one of them escaped. Those who were not killed outright were taken prisoners.

It was very fine while it lasted, and the men would have given anything to go on. But Colonel Conway knew the risk too well, and as soon as they had gained the summit of the cliff whistle signals from the sergeants stopped them, and the order came to dig themselves in with all speed.

It is one thing to occupy a trench already made, quite another to dig one under fire. There is no question of standing up and wielding the shovel as if one were digging a garden. Men must lie down and scratch and scrape until they get head cover, then gradually open up a narrow ditch into which they sink slowly.

'I didn't enlist as a blooming navvy,' grunted Roy Horan, who had stuck by Ken and Dave. 'Phew, but it's hot as a North Island beach on Christmas Day!'

As he spoke came an earth-shaking thud, and Ken, who was next to Roy, grabbed him by the collar and pulled him down flat on the ground.

Just in time, too, for next instant the earth three yards away in front burst upwards in a fountain of stones and pieces of broken steel. Ken felt a blast of heat and stinging sand across the back of his neck, while the concussion made his head ring.

'What the blazes?' muttered Roy, as he lifted his head and looked round dazedly.

'It was blazes all right,' answered Ken dryly. 'A high explosive shell, my lad. Lucky that it went pretty deep before it burst.'

'And lucky for me that you pulled my head down in time,' answered Roy soberly. 'Thanks, old man. I shan't forget that.'

The next shell burst behind the line, and the third still farther back. Fortunately for the Australians, the German gunners had not got the exact range, or the losses would have been fearful. High explosive of the kind the Germans use will pulverise the parapet of a trench and kill every one within reach.

The ground was hard, the sun hot, but the men dug like beavers, and within an hour had made themselves pretty safe. But there was no letting up. Colonel Conway insisted upon a regular trench of the latest pattern with proper traverses, and deep enough to give plenty of head room. The men grumbled, but some, like Ken, realised that the game was well worth the candle.