RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Cover of "Mountains of the Moon," F. Warne & Co., London & New York, 1935

Title page of "Mountains of the Moon," F. Warne & Co., London & New York, 1935

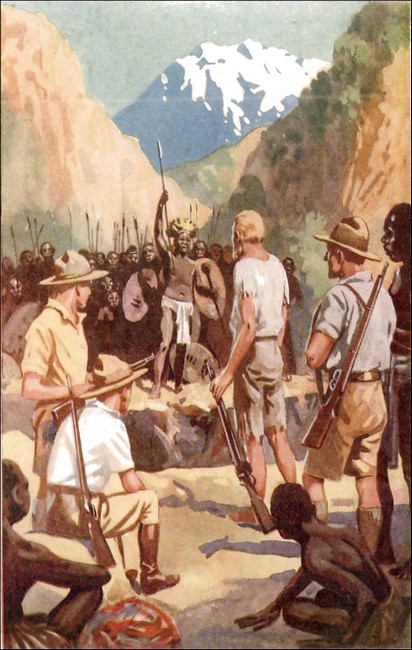

Frontispiece.

He gave a roar of anger, then up shot his broad-bladed spear.

JIM WITHERS pulled up short and stood listening.

"Hear that, Bart?" he asked.

Bart Bryson, who had hardly said a word since Jim joined him at the head of the lane, looked vaguely at the younger boy.

"Hear what?" he asked.

Jim stared hard at his friend.

"What's the matter with you, Bart? I never saw you like this before. What's wrong?"

"Everything," Bart answered. Then all of a sudden he seemed to wake up. His sturdy figure straightened, his grey eyes became alive. "Yes, I hear it," he said sharply, and the words were barely out of his mouth before a hare springing through a gap in the hedge on the right landed in the lane.

The little creature was covered with mud, she was almost exhausted, and her large, liquid eyes were full of fear. Instead of bolting away at sight of the two boys she came straight towards them, and cowered at their feet.

"Well, I never!" began Jim.

But it was Bart who stooped like a flash and picked up the hare. Only just in time, for next instant two greyhounds burst through the hedge and stopped, evidently wondering what had become of their quarry. Greyhounds are gaze hounds. They hunt by sight and not, like foxhounds, by scent, and as Bart had already hidden the hare under the skirt of his loose jacket, the dogs were puzzled.

"Well, I'm blessed!" exclaimed Jim. "I never saw anything like that before."

"You'll see something else pretty soon," said Bart. "This sounds like the chap who owns the dogs."

Sure enough, someone came crashing through the hedge and leapt down into the muddy lane. He was a tall boy, taller than Bart and probably a year older, and would have been quite good looking had it not been for his conceited expression. His hair was black as ink, he had very dark eyes, and his skin was darker than that of an average Englishman. Behind him was a stubby little fellow who looked like a groom or kennel boy. The new arrival glanced at his dogs, then turned to Bart.

"Where's that hare?" he demanded. All of a sudden he spotted what Bart was holding so carefully under his coat. "You mean to say you've picked it up!" he exclaimed! "Of all the cheek! Put it down at once."

Bart had quite lost his dull look. His face was slightly flushed, and his lips were very firm.

"I haven't the least intention of putting it down," he answered, "at least not till you and your dogs have gone back where you belong."

The other looked as if he could not believe his ears. His face flushed darkly.

"You cheeky young cub!" he cried. "Drop that hare this minute, or take the consequences."

The little groom man slipped up close to Bart.

"Let him have it, sir," he whispered urgently. "He's Mr. Jet Norcross, and a terror when he's upset."

Bart smiled. "He's going to be very badly upset if he doesn't keep his temper and clear out," he remarked. "Jim, take the hare and keep those dogs off it."

As Jim took the hare from Bart one of the dogs bounded forward and snapped at it, but Jim gave the beast a cut with his ash- plant which sent it snarling back.

"You dare hit my dog!" shouted Master Jet and sprang at Jim.

But Bart stepped quickly between and deftly thrusting out a foot tripped Jet who came down heavily on hands and knees in the mud.

He was up in a flash, and rushed at Bart, hitting wildly. Instead of dodging, Bart bent right down, caught the other round the knees, then hoisted with all his might. The natural result was that Jet left the ground, flew like a rocket over Bart's shoulder, and landed with a crash in the hedge at the side of the lane. The bushes saved him from being really hurt, but as it happened he struck a particularly thorny patch, and stuck fast.

Jim grinned broadly, Bart looked on calmly, but as for the little man he turned white and shaky.

"Run afore he gets out, sir," he begged of Bart. "He'll jest about kill you when he gets free."

Bart's answer was to take Jet by the legs and drag him out. The moment he was clear Jet rounded on Bart like a tiger. The thorns had not improved his smart tweeds, and he had a long bleeding scratch down one cheek, but to do him justice he was still full of fight, and he rushed at Bart again, hitting out with both hands. This time Bart stood his ground, and fending off the windmill blows awaited his chance, then sent in one straight left. His fist caught Jet on the point of the chin, and Jet sat down in the mud and this time stayed there.

"Sorry," said Bart quietly, "but you would have it."

Jet sat in the road and glared. He was too shaken to do much else. Bart turned to the little man.

"He'll be all right in a minute," he said; "then you can take him home. Come on, Jim."

"Rum bird that!" observed Jim as they went away.

"Bit of a spoilt beauty," agreed Bart. Then his pleasant face hardened. "But it was a rotten business hunting a hare like that, especially a doe. The chances are she's got young 'uns up on the down. I vote we go up there and turn her loose."

"We'd better be sharp about it," said Jim softly, "for here's more trouble if I'm not mistaken."

Bart looked up. "This old boy on horseback, you mean," he answered. "It does look rather as if he was waiting for us."

The old boy, as Bart had called him, was a thin-faced, yet very dignified old gentleman mounted on a quiet cob, and it occurred to Bart that he had probably seen the whole business. And so he had, for as the boys came alongside he spoke.

"May I ask your name?" he said to Bart.

"I am Bart Bryson, sir," replied Bart.

"Son of the explorer?"

"Yes, sir."

The other nodded. "My name is Clinton. I am uncle of that youngster whom you left sitting in the lane." He paused and looked hard at Bart. "Will you come up to Morden with me?" he asked.

Bart did not hesitate. "Very good, sir," he answered quietly, and turned to Jim "Take the hare up on the down, Jim, and turn her loose. And you might tell Dad that I am paying Mr. Clinton a visit."

Mr. Clinton did not say a word as he led the way to the iron gates of a drive and through them into a small park and so to a fine old house standing among splendid trees. At the door a groom came and took his horse, and Bart followed his leader up the steps into a fine hall with polished parquet floor and great stained-glass windows. They went through this into a small cosy room with a log fire burning in an open grate, and bookcases reaching almost to the ceiling.

"Sit down," said Mr. Clinton, and Bart obeyed, wondering what was going to happen, and not feeling very happy.

Mr. Clinton took the chair opposite, and sat looking at Bart for so long as to make him quite uncomfortable.

"So you thrashed Jet?" he said at last.

"I had to," said Bart simply.

"Oh, don't think I am complaining! I am very glad you did beat him. Do you think you could do it again?"

Bart gasped. He had quite thought he was in for trouble, and this answer of Mr. Clinton's was so surprising he could hardly believe his senses. Mr. Clinton smiled, and it was such a nice smile that Bart began to feel better.

"I really mean it," said his host. "I want to know if you could thrash Jet again."

Bart laughed. "Why, of course I could, sir. He doesn't know the first thing about boxing."

"Will you come and live here and do it then?" asked the other.

"No, sir," said Bart promptly. "Of course I won't."

Mr. Clinton nodded. "I thought you'd say that, and of course I didn't quite mean it. Bart, listen. Jet Norcross is my sister's son; she married a man who was half Spanish, and they lived in South America. Jet's father died when he was only six, and his mother spoilt him badly. She was very well off, and there was a big house with lots of servants and every luxury.

"She died last year and left the boy to me, and frankly I cannot do anything with him. I sent him to school, but he lost his temper and struck a master and was back on my hands in a month. Then I got a tutor for him, and the tutor stayed three days and left with a black eye and fifty pounds compensation money in his pocket. Jet runs wild, and no one has the least control over him. With that blazing Spanish temper of his, he will get into dreadful trouble one of these days, and I am at my wits' ends. When I saw you hammer him just now I thought that I had at last found someone who could handle him. What do you say, Bryson?"

Bart shook his head. "I'm sorry, sir, but it's a bit out of my line."

"Wait!" said Mr. Clinton. "Don't make up your mind in a hurry. Jet comes in for a very large fortune when he is twenty-one, and I too am a rich man. I may say that money is no object, and that I should be prepared to pay you very well if you would come and live here with him and act as bear-leader."

"It wouldn't be a bit of good, sir. If you'd take advice from a youngster like me the only thing would be to send him abroad—into the wilds, I mean."

"Then take him into the wilds. Who better than you, for I believe you have already been in Africa with your father?"

Bart hesitated, and the other saw it.

"Remember, money is no object," he urged.

"Do you really mean that, sir? Would you go as high as £2,000?"

Mr. Clinton looked surprised for a moment.

"That's a large sum, but yes, I would."

"May I explain, sir?"

"Do," said Mr. Clinton cordially.

"It's this way, sir. My father has had bad news. His partner, Mr. Mark Murdoch, has disappeared."

"Disappeared?"

"Yes, in Africa. He and all his boys—carriers, you know—were on their way to a place where Mr. Murdoch had heard of a quantity of ivory, but they never reached it, and Dad believes that they have been taken prisoners by a tribe up in the hills."

"What hills?"

"Ruwenzori, sir."

"I know. Just north of the Equator. Yes, there's some bad country there—and bad niggers."

"You know it, Mr. Clinton?"

"No, but I have been in Uganda, and I know something of Africa." He paused and gazed at Bart. "Do you mean that you want to take Jet out there?" he asked.

Bart hesitated. "I know it's rather a large order, sir, but after what you said, it seemed—well—a sort of chance."

"Is your father going?"

"He's mad to go, but can't afford it. He had put up every penny, he had to pay for the expedition, and now I don't think he has enough left for our fares to Mombasa, let alone the expense of carriers and an expedition up country."

Mr. Clinton did not answer, and Bart went on quickly: "But of course it's absurd to think of your putting up so much money, sir. It was only—"

The other cut him short. "Not at all, Bryson. £2,000 would be a cheap price to make a man of my nephew, and I would pay it gladly. And if you could not do it in Africa you could not do it anywhere. I was thinking of the one hitch in the matter."

"What's that, sir?"

"Getting Jet to go. I can't force him to accompany you."

"Ask him, sir, and if you don't succeed, I'll have a try."

Mr. Clinton looked doubtful. "I'm afraid he will turn it down, Bryson, but I will do my best. No, don't go yet. You must have some tea first."

BART reached Morden sharp at ten the next morning and found Mr. Clinton waiting for him.

"What luck, sir?" he asked.

"I hardly know, Bryson. At any rate Jet has promised he would see you. Have you said anything to your father?"

"Not a word, sir. It would be such a terrible disappointment to him if it didn't come off."

"Quite so. I think you were wise. Ah, here is Jet."

Young Norcross came across the hall. He was wearing riding breeches and gaiters and looked so big and powerful that Bart rather wondered how he had come to throw him so easily the day before.

"Hullo!" said Jet. "Your name's Bryson, isn't it. Uncle says you've got some stunt on that I'm to hear about. I'm game to talk it over. Come on."

He was civil as pie, but Bart caught a queer glimmer in his dark eyes and wondered what was working in his mind. Bart had not knocked about Africa for nothing. He knew men better perhaps than any boy of his age in England, yet whatever suspicions he had, he was not going to show them.

"Right," he said, and went with Jet.

Outside the front door, Jet spoke again.

"Do you ride?" he asked.

"I have ridden," Bart answered.

"Good business!" Jet's tone was quite friendly, but all the same Bart sensed trouble. "I've got a mount for you, and we'll just go for a tootle round, and you can tell me all about this game."

He led the way to the stable yard where two grooms were holding two saddled horses. One was a nice-looking bay, the other a blaze-faced chestnut.

"That's my tat," said Jet pointing to the bay. "The other's for you. Pedro he's called. Fine beast, ain't he?"

Bart looked at the horse. He was standing quietly enough, but his ears were laid back, and his eyes showed a deal too much white to be healthy. It did not take Bart five seconds to realise that the beast was vicious.

"Like him?" asked Jet.

"Not a bit," replied Bart.

Jet grinned. "He is a bit of a handful," he admitted. "But see here, Bryson, I'm not going off on a trip with any chap who can't handle a horse. If you ride Pedro and stick on for five minutes I'll come to Africa with you. If you can't it's a washout. Now what about it?"

Bart did not hesitate. The stake was too big.

"I'll take you on," he said promptly.

Jet grinned again, showing all his very white teeth, as he watched Bart go up to the chestnut.

"Can you ride, sir?" asked the groom in an anxious whisper. "This here horse is a proper terror."

"I can stick on a bit anyhow," Bart answered. "Has he any special tricks?"

"Bolting, sir. He bucks a bit too, but it's bolting you got to watch for. Hold him well on the curb for his mouth's like iron."

"Thanks," said Bart as he swung into the saddle. He felt the horse's quarters heave upwards. "Now for it!" he said to himself.

Up went Pedro, head down, back arched, tail tucked tight between his legs—up, then down again with all four feet close together, giving Bart a jar that made his teeth rattle. Up again, and down again until Bart felt as if his bones were coming unstuck. Bart had not been boasting when he had told the groom that he could stick on, and both the men watched him as he sat well back, his knees tight against the saddle, clinging with his heels to the mad brute's sides.

Six times Pedro bucked, then finding he could not get rid of his rider in this fashion changed his tactics, and swinging like a flash made a bolt for his stable.

"Hold him, sir," roared the groom.

But Bart had already tightened his grip on the reins and using all his strength managed to pull the horse's head round. Pedro reared, but Bart snatching off his cap struck him with it over the head. He squealed with rage but came down and started kicking like a crazy thing. His heels missed Jet's horse by a matter of inches, and Jet quickly pulled round.

"Come on," he said, and led the way out of the yard.

Pedro followed in a series of wild bounds, but this was nothing after his bucking, and Bart's spirits rose. He felt he was past the worst of it. Quite three minutes must have passed, and if he could stay on for two more he had won the day.

Jet glanced at him as he came alongside, and Bart fancied there was a scared look in his queer dark eyes.

"You ain't doing so badly," he said with a half sneer, "but the five minutes are not up yet."

He kicked his bay as he spoke, and the creature sprang forward down the drive. Instantly Pedro made a bound which almost unseated Bart, then with a sudden snatch caught the bit between his powerful teeth and was away. He passed Jet's mount like a flash and went straight down the drive, scattering the gravel under his iron-shod hoofs.

With his feet firm in the stirrups, Bart leaned back, throwing every ounce of strength in his body into an effort to stop the mad brute. He might as well have tried to stop a locomotive, for Pedro had the bit hard gripped between his teeth.

"Nothing for it but to sit tight," said Bart to himself. "I only hope we don't meet anything."

A gardener saw the great horse racing down the drive and pluckily ran forward shouting. But before he could reach him, Pedro was past and the next moment had swept out of the gate into the road, where he swerved and went straight down it.

A car was coming up, and the driver hastily turned into the side of the road and clapped on his brakes. As Pedro tore past Bart had just time to see that it was his father at the wheel, and to catch the look of horror on his face.

"All right, Dad!" he yelled. "Don't worry."

But whether his father heard or not he could not say. Pedro swung round a curve, and here was fresh trouble: a huge lorry lumbering up the centre of the road. The only chance to pass in safety was to get Pedro on the footpath, and leaning forward Bart took hold of the near rein and pulled with all his might.

The result was startling. Pedro swung sharp to the left, and the gaping lorry-man had a vision of the great horse and his rider poised in mid air over the hedge. The unexpected leap lost Bart one of his stirrups, but clutching the horse's mane, he managed somehow to stay in the saddle, and as Pedro raced across a wide pasture he caught his stirrup again. Bart's eyes were shining with excitement.

"I've won," he cried aloud. "The five minutes must be up. Steady now, Pedro!"

But the chestnut was still fresh as paint, and Bart's light weight nothing to his mighty muscles. He rushed on at the same tremendous speed. It seemed only a moment before they reached the far side of the field. The hedge was big, but Pedro did not hesitate. This time Bart was ready, and he actually enjoyed Pedro's sailing leap. The horse landed safely and galloped on.

The field was plough, and Bart hoped the heavy going would tire his mad mount, but not a bit of it. Pedro did not check for a moment, and took a third hedge with the same effortless ease. The ground fell away in a long slope, and the horse went faster than ever. Bart knew that the river Ravy ran through the bottom of the valley. He could see its sunlit surface gleaming among the trees in the distance.

"That ought to stop him if anything will," said Bart to himself.

There was another hedge in front, a low one this time. It was not until he reached it that Bart realised what was beyond, and then it was too late to do anything, for as Pedro jumped Bart saw beneath him a long, steep, grassy bank dropping to the railway which ran at the bottom of the cutting. It looked all odds that Pedro would land on his head and roll all the way down smashing the life out of Bart as he went.

But the horse was clever as a cat, and somehow saved both himself and his rider. He came down with all four feet bunched together and slid down the bank on his haunches. Bart hoped to check him at the bottom, but the horse, badly frightened by his adventure, no sooner felt firm ground under his feet than he darted off as hard as ever. There was only a single line of rails, and Pedro raced along between them. Bart could do nothing except pray they would not meet a train. Next instant a distant whistle reached his ears.

The sound came from behind him, and Bart glancing back saw smoke barely half a mile away. He looked at the banks on either side, but they were far too steep to climb. His only hope was to get clear of the cutting before the train caught them, and he drove his heels in and beat Pedro's flanks with his hat and shouted to him to go faster.

Pedro seemed almost to fly, but even so the train gained. The cutting walls grew higher, and all of a sudden Bart realised that the cutting ended in the black mouth of a tunnel. His blood ran cold at the sight, but he had no choice.

"Let's pray it's not a long one," was his thought, as he and his horse shot into the gloom.

The whistle came again, closer, louder. The driver was whistling for the tunnel, and Bart heard the roar and hammer of the wheels on the rails.

A false step, a stumble, and nothing could save him. Seconds seemed like hours. Would the tunnel never end? Bart did not dare to look back, but he knew the train could not be more than fifty yards behind him. Then a pale glimmer showed ahead, and light gleamed on the dripping brickwork of the tunnel walls. A moment later a pointsman at work near the mouth saw the horse and rider dash out of the dark arch, with the train almost at their heels.

The line beyond the tunnel was cut in the face of a steep bank dropping to the Ravy. On the left the hill rose sharply; to the right was a drop of five or six feet down to the swirling eddies of the stream.

Bart saw one chance only and took it. Seizing the off rein, he jerked it with all his remaining strength, and with one tremendous bound Pedro left the line. As the train roared by the startled passengers saw a great chestnut horse with a boy on his back sail through the air and vanish with a tremendous splash in the rushing waters of the river. Then before they were out of sight of the spot those who had their heads out of the windows saw horse and rider rise again, the boy clinging to the horse's mane, the horse swimming strongly for the far bank.

Pedro swam almost as well as he galloped. He reached the far side, and as he did so Bart slipped off, got hold of a bush, and hauled himself out. Pedro took longer to struggle up the steep clay bank so that when he reached the top Bart was waiting for him and caught him by the bridle. The icy plunge had cooled the terror, and he stood quiet as a sheep while Bart hoisted himself into the saddle.

"Get on home," said Bart, giving him a dig in the ribs, and the chestnut cantered off like a lady's hack.

The pair had hardly reached the road before Bart saw one of the Morden grooms riding towards him at a gallop.

"My word, but I'm glad to see you, sir," gasped the man as he pulled up. "Mr. Clinton, he's in a terrible way. But for any sake, where've you been, sir—in the river?"

"There, among other places," smiled Bart. "Where's Mr. Norcross?"

"Somewheres out looking for you. Why, here he comes!"

Jet came riding hard up a side lane. There was not much colour in his face, and he had lost all his usual uppishness.

"By Jove, I'm glad to see you, Bryson," he exclaimed, and there was no doubt he really meant it. "I don't mind telling you I got a nasty turn when I saw you go down the embankment on to the line."

"Oh, you saw that, did you?" replied Bart. "Then you know I stayed on for full five minutes."

"You did that all right. By gum, but you can ride!" he added, with a sort of unwilling admiration. "But you're soaked, and so's the gee. What happened?"

Bart told him as they rode back. As they came up to the house Bart saw his father with Mr. Clinton in the porch. Mr. Bryson, a lean, hard-bitten man of forty, came striding down the steps.

"What fool's game have you been playing, Bart?" he demanded sharply. "Haven't I enough troubles on my hands without your adding to them?"

Bart was so dismayed that he could not answer, but Mr. Clinton came to his rescue.

"Don't blame your son, Mr. Bryson. If I am not much mistaken, the whole business is the fault of my nephew. Jet, was it you who put young Bryson up on Pedro?"

Jet scowled. "I wanted to see if he could ride," he answered sulkily.

"I suppose you never considered the chances of his breaking his neck," said Mr. Bryson sharply.

"He needn't have ridden the horse if he didn't want to," retorted Jet.

Bart cut in quickly. "Dad, I had a jolly good reason for riding that horse, and anyhow neither of us is any the worse. Please don't say anything more about it—at least until we get home."

Mr. Bryson gave his son a quick, sharp look, and saw at once that there was something more behind all this than he understood.

"Right," he said curtly. "And now you'd best come home with me at once and change."

"He is not going to drive home in those wet things," said Mr. Clinton. "Jet, you can give him a change."

"Oh, I can find him some duds!" said Jet carelessly. "Come on, Bryson."

He led the way up to a luxurious bathroom, and came back in a minute with an armful of clothes.

"Here you are," he said.

"Wait a minute," said Bart. "Does what you said go?"

Jet flung up his head. "Of course it does. Do you think a gentleman breaks his word?"

"A gentleman doesn't," returned Bart drily, as he stripped off his soaking shirt.

Jet flushed darkly. "What do you mean by that, you young cub?"

"Just what I said," replied Bart. "But since you're sticking to your promise there's no need to get excited."

Jet stood looking at Bart, and his expression was not pleasant.

"See here, Bryson, I've let myself in for this trip with you, but don't fancy because I'm coming that you're going to boss me."

Bart laughed. "My good ass, I haven't a notion of doing anything of the kind. The boss of the show is my Dad, and you and I have both got to take his orders."

Jet scowled. "I don't take orders from anyone," he said angrily. "I'm my own boss."

"That's just where you're all wrong," laughed Bart.

"What do you mean?"

"Why, that no fellow is his own boss until he can keep his temper," returned Bart.

Jet bit his lip. "I've a jolly good mind to paste you one for that," he exclaimed.

Bart laughed again. "I wouldn't if I were you. You don't know the first thing about boxing, and you'd only get a real hammering. But what's the use of quarrelling? You and I have got to be together for quite a time, and it'll be a lot jollier if we make up our minds to get on decently. What do you say? Will you shake on it?"

Jet looked oddly at Bart for a moment. Then he smiled crookedly.

"Perhaps you're right," he said, and took the offered hand.

Half an hour later Bart and his father drove away from Morden. Jet and Bickell, the odd little man who acted as his body servant, watched them go. Bickell ventured a question.

"Be you really going with them, sir?"

Jet laughed. "Yes, I'm going," he said.

"To Afriky, sir?"

"Yes, to Africa. Like to come, Bickell?"

"What, me, sir? All among them swamps and niggers and lions. Not if I knows it." He paused. "And you won't like it either, sir."

Jet laughed again. "One can always come home," he said. His lips tightened. "I shan't go a yard further than I feel like going, Bickell, but you can keep your mouth shut about that."

LANTERN in hand, Bart Bryson thrust his head into the tent where Jet Norcross was sleeping.

"Jet—I say, Jet!"

The other stirred; his heavy eyelids rose.

"What's the matter?" he demanded drowsily. "Can't you let a fellow sleep?"

"Sleep!" repeated Bart. "It's a trance you must have been in. Mean to say you haven't heard the row?"

"Haven't heard a thing. I tell you I was asleep."

"You'd best wake up then. The river's rising like a tide. It'll be over this bank in less than half an hour. We're shifting to higher ground the other side. Most of 'em are gone already."

Jet sat up, thrust his mosquito net aside, and flung his legs over the side of the cot.

"What a beast of a country!" he said bitterly. "Can't even get a night's sleep. Last night the hyenas kept me awake till dawn, and the night before that brute of a lion roused us all. I'm fed up."

"Better be fed up than drowned," replied Bart. "You'd best hurry, Jet, for the river's alive with crocs, and they'll be out over the bank in a precious short time. Besides the stream's getting stronger every minute, and we shall have our work cut out to cross. Here—Forty and I will shove your things together while you dress. Come on, Forty."

An immense negro stepped out of the gloom into the circle of light. He had a flat nose, a huge mouth, and his face was black as a coal. Yet in spite of his ugliness Forty, a Kroo boy from the coast, was the best servant that Mr. Bryson had ever had, a simple, faithful soul, with the heart of a lion and muscles of steel. His huge, capable hands had packed all Jet's belongings before that sulky gentleman had finished dressing; then he and Bart folded up the tent, and the three, heavily laden, made their way cautiously down the river bank.

Out in the hot blackness the river sucked and swirled with strange noises as the flood, caused by some fierce storm a hundred miles away up in the hills, rose swiftly, and then the deep gong-like bellow of a bull crocodile split the night.

"Here we are," said Bart as he got hold of a rope and pulled up a canoe. "Slip the things in, Forty. Go easy, Jet. There are too many snakes along the bank to be healthy."

"Where are all the others?" demanded Jet.

"Gone across. It's about a mile upstream."

They got in, Bart and Forty took the paddles, and they pushed out.

"She run berra quick," said Forty as he dug in his paddle.

"It's filthily dark," growled Jet.

"Yes, I hope they'll show us a light," said Bart. "Pity we couldn't have waited an hour. The moon will be up then."

A crash, and a shower of warm spray flew over them.

"What's that?" cried Jet in alarm.

"A croc," Bart told him. "Paddle, Forty. We'll be all right once we're away from the bank."

A moment later the dim outline of the black forest trees on the bank had faded, and the rough dug-out was driving against the full force of the flood. Its silent power was terrific, and now and then huge logs and trees torn from the broken banks loomed up. Bart knew that if one hit their canoe it meant disaster, but he said nothing.

On they drove. They could see nothing except the water that glimmered darkly around them; they could not tell what progress they were making or whether they were making any progress at all.

"These mosquitoes are simply awful," grumbled Jet.

Bart's lip curled, but he made no answer. He had a notion there would be something worse than mosquitoes to put up with before long. Forty spoke.

"Whar dat light, baas? I no see him."

"I don't expect they've had time to light a fire yet," Bart told him. "But we must be near the other side."

"I see dem trees," said Forty.

As he spoke the canoe was caught in a whirlpool which spun her round in spite of Forty's efforts. For a moment it was touch and go; then they were shot clear to find themselves close under a bank crowned with tall trees.

"Let's land," said Jet sharply. "If we get caught in another of those beastly spins we shall all be drowned."

"I tink him right, baas," said Forty. "We stop here till moon him rise."

"Right," said Bart. "Jet, hold the lantern so as we can see to land."

The light of the lantern was reflected from a pair of narrow green eyes set close together. Forty struck with his paddle, and six feet of deadly green mamba writhed with broken back. Forty shovelled the poisonous brute into the water and stepped ashore.

"Water, him still rise," he said. "We make tie dem canoe pretty strong."

They tied her with a long rope to a tree well up the bank, then taking their guns, mosquito nets, and blankets, went cautiously up the slope. Came a crash in the bushes, and a beast ugly as a bad dream rushed across in front, its red eyes and long white tusks gleaming in the lantern light.

"What's that?" cried Jet.

"Only a wart-hog," said Bart. Then as the light showed more shadows in the bush beyond he stopped. "Forty, this place is full of beasts."

"I tink dem drove here by de ribber, baas," said Forty.

A shattering roar crashed through the gloom. "A lion!" gasped Jet, cocking his rifle.

Bart pulled up. "It's a lion all right, and there are buffalo close by. What are we going to do, Forty?"

"Climb dem tree," Forty remarked briefly. "Den we be safe."

It was not a particularly pleasant suggestion, but for once Jet made no objection. They chose a huge mapoli, a tree not unlike an English elm, and swung themselves up. Thirty feet above the ground they found a thick limb running straight out on which they could all sit with some comfort.

Beneath in the gloom they could hear the sound of many moving things, uneasy stampings, now and then a muffled bellow. But they could see nothing. Above them, too, were rustlings which told of monkeys in the higher branches. The mosquitoes were cruel, but they wrapped their nets around their heads, and this saved them.

At last the moon rose above the trees. It looked double its usual size and was the colour of copper. Its light fell upon banks of white mist which drifted over endless stretches of swirling water. Forty looked all round, then turned to Bart.

"I tink dem ribber, he go round behind us, baas," he remarked.

Bart whistled softly. "You mean we're on an island?" He looked again. "You're right, Forty, and it won't even be an island very long. The water's coming up so fast it will be all over it before morning."

Jet who had been nodding roused.

"Then for goodness' sake let's get off the beastly place," he snapped.

"Nothing doing, I'm afraid, Jet," Bart answered. "Look down."

Jet looked down. A multitude of eyes shone luminous in the darkness around the foot of their tree. Jet shivered.

"Nice mess you've got us into," he said angrily.

Bubbling and gurgling the flood crept up, and as the land space lessened the beasts crowded closer. The moon was high now, and looking down the refugees could see great hairy buffalo, antelope with long straight horns, bearded hartebeest and many other creatures crowded in a surging mass. Around and among them prowled two lions. The strange thing was that the lions made no attempt to attack the other creatures, but now and then growled and at intervals roared terribly. From a tree near by a leopard coughed and snarled, while always overhead the branches rustled where a multitude of monkeys moved restlessly.

Pungent scents rose from the packed mass below. There was a reek of civet, mixed with the odour of crushed acacia and other plants. The terrible part of it was the agonized screams which rose now and then as some unfortunate animal was seized by a crocodile and dragged struggling beneath the yellow swirls of the ever rising flood. The river was full of the hideous brutes gathered to their terrible feast, and the moonlight showed their scaly forms floating like logs all around the ever lessening island.

"Looks like a second edition of Noah's flood," said Bart at last.

Jet smacked viciously at a mosquito.

"And it's your fault, you idiot!" he snapped. "If you'd only roused me earlier we could have gone with the rest."

Bart laughed. "You are the limit, Jet. It was jolly lucky for you that I remembered you at all."

"That was your job, wasn't it?" returned Jet sourly. "You brought me out to this horrible country."

"What him mean, baas—horrible country?" asked Forty. "I tink dem country him lib in much more horribler dan dis. I go dere one time wid big ship, and dere ain't no sun, no warm in de air. All de people dey wears macletoshes and umblebrellas. Ugh, dat's de horriblest country!"

In spite of his extremely uncomfortable and rather dangerous position Bart laughed again.

"At any rate there are no lions there, Forty, except in cages," he said. "And we don't have floods like this."

Jet was not at all amused. "Are we going to get out of this alive?" he demanded.

"Oh, I have hopes!" Bart told him. "But I'm afraid we'll have to wait till daylight. There's rather too much of a menagerie below there to risk going down for the present."

Bart spoke lightly, but he did not feel as cheerful as he pretended to be. The water rose and rose, and there was no saying when the crest of the flood would pass. And even as he looked down at the strange congregation of beasts below, there came a rending roar and a great tree, its roots sapped by the swirling waters, fell over into the flood. Screams that were almost human arose as its terrified occupants, monkeys and baboons, found themselves dropping into the jaws of the terrible crocodiles, but luckily for them the tree swam high above the flooded river and most of the poor creatures seemed to be still safe in the branches.

"Is that what's going to happen to us?" asked Jet harshly.

Bart grew a little impatient. "You're a cheerful sort of johnny for a job like this," he retorted. "Do buck up, man! You might remember that you're getting a sight that precious few people have ever seen."

"Personally I prefer the Zoo," sneered Jet, and Bart, seeing it was hopeless, remained silent.

Time passed, and still the flood rose, though more slowly. The buffalo were grouped around the tree which, big as it was, shook under the pushing of their ton-weight bodies. Now and then one of them would lower its head and drive furiously at something creeping, half seen, over the soggy ground.

"Dem crocs, dey try get dem buffalo," muttered Forty.

"Strikes me the buffalo are getting them," replied Bart grimly as he saw a scaly length writhing, with its pale lower side uppermost. "Brutes! If I had the cartridges I'd shoot 'em."

But cartridges are precious in Central Africa, and not to be wasted on crocodiles. Bart leaned back against the trunk of the tree. He was deadly sleepy but dared not doze off for fear of falling. He found some chocolate in his pocket and divided it. The lantern burned out, and the only light was that of the moon.

"Water, him fall," said Forty at last, and Bart seeing he was right gave a sigh of relief.

He could see the canoe riding safely at the end of her rope, and hoped that, when dawn came, they would be able to get off in safety. But he was troubled about his father, for he knew he would be desperately anxious. He hoped that he and the native "boys" were safe on high ground, but it was impossible to say where they were.

Jet said never a word, but by this time Bart was accustomed to his sulky fits. He had had plenty of experience of them during the six weeks that they had been travelling up from the coast.

The night seemed endless, but at last a greyness crept up from the East, and Bart's spirits rose as he realised the dawn was at hand. As the light increased it showed the huge flood rolling past yellow with mud and carrying with it trees, dead animals, all sorts of rubbish. And though the water was falling the rising ground on which their tree stood was still an island so that the creatures penned there could not get away. Bart looked down at the huge hairy backs of the buffaloes, beasts more dangerous to the hunter than the lion himself.

"How the mischief are we going to get out of this, Forty?" he asked.

Forty looked doubtful. "I tink we wait, baas."

The sun rose, a great ball of splendour making the wide waters shine like gold, and out in the very centre of the vast expanse Bart saw a canoe.

"Hullo!" he said sharply. "They're looking for us."

Forty gazed at the canoe, shading his eyes with his great hand from the glare. He shook his head.

"Dat ain't none ob our boys, baas. Dat stranger boy. And him hurt so he no can paddle."

"By gum, you're right, Forty! A broken arm, by the look of him. And see, he's spotted us. He's signalling. We've got to save him."

Jet woke up. "Don't be silly. How can you save him? Why, we can't get out ourselves, with all those brutes waiting for us below."

"You stay here, Jet. Forty and I will tackle the job."

"Stay here alone!" Jet's voice rose to a shriek. "You're crazy. You jolly well stay where you are."

But Bart had swung himself to a lower branch, and Forty was following. Jet grabbed at Bart, missed him, and nearly fell out of the tree. He scrambled back raving with fury. Bart looked up.

"Keep quiet, you idiot! You'll start these beasts up if you make such a row."

He and Forty dropped quietly to the ground. They had their guns ready, but the buffalo made no motion to attack. The great beasts were sullen but frightened. The lions were not visible. All the same it was an ugly minute until the pair reached the canoe which, thanks to the long rope, had floated safely.

By the time they got afloat the other canoe was opposite, and they had the current to help them in chasing her. Now that there was light, it was easy to avoid the floating logs and spinning whirlpools, and in a very few minutes they were alongside.

Forty leaned over and picked the other out of his canoe as easily as if he had been a baby. The poor creature was little more than skin and bone. Then leaving the other canoe to drift where it would, they started back. The native talked eagerly, but in his own language, and Forty between strokes translated.

"Him name Imbono," he explained. "Him say him looking for Baas Bryson."

"You don't mean he has news of Mr. Murdoch?" cried Bart.

"Dat's it, baas. Him come from Baas Murdoch. But it berry bad news."

BART drew his breath quickly.

"Bad news? Tell me, quick."

With a tremendous stroke of his paddle Forty sent the canoe clear of a sucking eddy.

"Him say, baas, dat Kasoro, him got Baas Murdoch."

"Who is Kasoro?"

"Him big Chief. Berry bad man. Him lib in dem hills." He nodded in an easterly direction.

"The Mountains of the Moon," said Bart sharply. "Are the prisoners alive?"

"Dey lib, but dey in tight hole. Dey work for Kasoro, and he no let dem go."

Bart frowned. "If they're in the same state as this poor beggar it's a bad job," he said. "See here, Forty. We must get the news to Dad as quickly as we can. This chap wants food and medicine, and it's no use taking him to the island."

"Dat's true, baas. We go right up him ribber, and find Baas Bryson."

"But we can't leave Baas Norcross in the tree."

"Me tink do him good," returned Forty with a twinkle in his small eyes.

Bart looked doubtful, but just then the crack of a signal shot came ringing across the flood, and another canoe came into sight. Bart gave a shout.

"That's one of ours anyhow, Forty," and Forty nodded.

"Sure ting, dat one ob ours."

The canoe, a big one with four natives paddling and Mr. Bryson himself in the stern, came quickly to meet them, and Mr. Bryson's face showed how glad he was to see his son. Bart explained quickly what had happened, and the other nodded.

"Yes, it was the only thing you could do," he said briefly. "Where's Norcross?" Bart pointed.

"Right. You and Forty take the boy you've picked up to the camp. You'll see the smoke. I'll fetch Norcross. Take care of that nigger. He's our only chance of finding Murdoch."

He gave fresh orders to his boys, and his big canoe drove towards the island, while Bart and Forty struggled upstream against the tremendous weight of the current. They were both thankful when they caught sight of a plume of grey smoke rising among the trees on the left bank, and they came ashore to find camp pitched under a great banyan on high, dry ground, and a rich smell of cooking in the still, morning air.

Imbono, the rescued boy, was so nearly done that Forty had to carry him up to the camp. But a platter of hot meal porridge with sugar and condensed milk made all the difference, and by the time that Mr. Bryson got back with Jet, Imbono was sitting up and looking wonderfully better.

The man's arm was not broken, but his wrist was badly strained and swollen. Mr. Bryson tied it up, and Imbono's eyes shone with gratitude. Then he began to talk, and since Mr. Bryson understood his dialect there was no need for an interpreter. When he had finished Mr. Bryson explained things to the others.

"I've heard of this Kasoro," he said. "He's a pretty bad egg by all accounts, and head of a very tough crowd. They managed to surround Murdoch's party by night and took the lot as prisoners to their village somewhere up in the hills to the west of Ruwenzori where Kasoro is holding them for ransom. It seems he sent this fellow Imbono down country to meet us and tell us what ransom he demands."

Jet broke in rudely. "I never heard such rot. How could he possibly know we were coming? They don't run to telegraphs in the bush, do they?" he added with a sneer.

"Exactly what they do have, Norcross," replied Mr. Bryson quietly. "News can cross the whole of this continent in a few hours."

Jet looked so surprised that Bart almost laughed.

"It's true, Jet," he said. "They do it with drums. They've got a regular Morse code, and news travels almost as quickly here as in England. I wouldn't wonder if Kasoro knows just where we are, and what we're after, and how many there are of us."

"Then it's worse than I thought," growled Jet. "Next thing, I suppose, this beggar Kasoro will be scooping us in."

"You need not worry your head on that score," Mr. Bryson told him. "Hill men don't come out of the hills any more than river men go into the mountains. In fact, all African natives stick pretty closely to their own territory. We're safe enough from Kasoro for some time to come."

"In that case I'll get some breakfast," said Jet. "And then I'm going to have a jolly good sleep. I'm nearly dead after spending the night perched in that beastly tree."

Mr. Bryson watched him go. "You don't seem to be making much progress in that direction, Bart," he said drily.

"Not a lot, Dad," allowed Bart, "but never mind Jet. I want to hear what sort of ransom this fellow Kasoro is after."

"One we can never pay him," returned his father curtly. "He demands twenty rifles, twenty boxes of cartridges, and ten cases of gin."

Bart's face fell. "No, of course not," he agreed. "Then what are we going to do, Dad? We've got to get Mr. Murdoch out somehow."

"Of course. I must think it over. Meantime you'd best follow Norcross's example. Get some breakfast and some sleep. We can't shift from here until the flood has run down."

Bart did not know how tired he was until he stretched himself on the cot which Forty had made ready for him. He was asleep in a minute and did not rouse until late in the afternoon. Then he found the rest of the camp awake and very cheerful. They had all been travelling hard since they left the river steamer at Pindi, and a good rest was just what they had needed. He himself felt wonderfully fresh and also very hungry, and he went towards the fire from which came a savoury smell of grilling antelope steak. He, his father, and Jet sat down to an excellent supper, and the native boys too rejoiced in plenty of fresh meat.

Jet was more cheerful than usual.

"I suppose we'll be going back now," he remarked.

Bart stared. "What on earth do you mean, Jet?"

"Just what I say," replied Jet. "Forty tells me that this chap Kasoro is much too strong for us to attack, and that it's against the law to give him the rifles and gin he wants, so what else is there to do except go back?"

"And leave Mr. Murdoch to slave on Kasoro's yam plantation? Is that your idea?" asked Bart softly.

"It's rotten for him of course," agreed Jet, "but we can't do any good by helping him dig yams, can we?"

"We're not going to do that, Jet. We're going to get him out."

"You mean you're going on!" cried Jet.

"Of course we are going on. You didn't think we'd sneak back home with our tails between our legs, did you?"

"You're mad," retorted Jet, and turned to Bart's father. "Tell him he doesn't know what he's talking about, Mr. Bryson."

"I can't do that, Norcross," said Mr. Bryson, "for of course Bart is perfectly right. We are going on towards the hills as soon as the flood runs down."

Jet's face went angry red. "If you think I'm going to dig yams for a nigger king, Mr. Bryson, all I can say is you're quite wrong. I'm going home."

Mr. Bryson was quite unmoved. "Very well, Norcross. We can spare a canoe, and it shall be made ready for you. But I regret I cannot spare a man, so I am afraid that you will have to make the journey alone. But no doubt you will manage your own camping and cooking."

Jet sprang to his feet. "Me travel alone! You're crazy. I'm not going to do anything of the sort."

"Then perhaps you had better come with us," said Mr. Bryson quietly. "You need not be afraid. I shall not ask you to do any fighting."

Jet stood glaring at the other two for some seconds, then suddenly swung away and stalked off to his own tent. Mr. Bryson shook his head.

"We are earning our money, Bart," he remarked.

In spite of his nap during the day Bart was quite ready for another good sleep, and since the water was running down fast and they were to start at dawn he turned in fairly early. It was still dark or rather moonlight when Forty shook him awake.

"Berry bad news, baas," announced the big nigger. "Dem white boy him gone."

Bart shot to his feet. "Baas Norcross gone, Forty?"

"Couldn't be no one else, baas," said Forty soberly.

"How?"

"In a canoe, baas."

"My word, I never thought he had the pluck," said Bart as he pulled on his shoes.

"I never dreamed he'd go off alone like that."

"Him nebber go alone. Him took dat Sam boy."

"Sam—that no-count boy from Kafui?"

"Dat's him, baas. And dey took a canoe and went down dem ribber."

"Does Dad know?"

"He know, baas. I told him first. Here be him."

Mr. Bryson came into the tent.

"This is a nice business, Bart," he said bitterly. "And just when we were hoping to get off."

"It's pretty bad," agreed Bart. "But you leave it to me and Forty, Dad. We'll catch him pretty quickly and follow you."

Mr. Bryson shook his head. "They have at least six hours start. From what I can make out, Norcross left as soon as we were asleep. And you can bet he hasn't wasted any time. They're thirty miles from here this minute."

Bart whistled softly. "That's bad. And they can both paddle a bit if they're pushed. I suppose he bought that boy Sam."

"Bribed him without a doubt," said his father frowning. "'Pon my word, Bart, I'm half inclined to let him go."

Bart shook his head. "Can't do that, Dad. I took the contract to look after him."

"That's a fact," agreed his father, "but it's poor Murdoch I'm thinking of."

"I know." Bart was dressing rapidly as he spoke. "But you can trust the job to Forty and me. You go on to the head of the river, camp there, and get what news you can. We'll paddle all day if we have to and drop on Jet in his camp to-night. We ought to catch you up in—say—four days from now."

"I suppose it's the only thing to do," said the other with a sigh. "All I can say is this: If that fellow tries anything of this kind a second time I'll take a stick to him. Yes, big as he is, I'll beat him."

Bart's eyes twinkled. "I'm afraid that wouldn't work, Dad. It would only make him more sulky. What he wants is a real rough time. Hard work and not too much grub."

"He will get that before we're finished," said Mr. Bryson. "He will get that and more if I'm not much mistaken. Well, push along, my lad. I'll look for you when I see you."

Five minutes later Bart, having swallowed a cup of hot coffee, was paddling downstream with Forty in a small canoe, and when the sun rose the pair were already miles from the camp. Bart was tough as leather, while as for Forty his great muscles were like steel, and he did not seem to know the meaning of fatigue. Hour after hour the paddles rose and fell, and the canoe sped on down the yellow flood between lines of lush green bush. At noon they landed on a sand spit and ate and rested for an hour, then went on again. When dusk came Bart reckoned that they had covered nearly fifty miles.

"We can't be far behind them now," he said to Forty.

"No, baas, not if dey go straight."

"What!" exclaimed Bart anxiously. "You think they would have the sense to hide and dodge us?"

"Sam, him pretty clebber nigger," said Forty. "Him not like berry hard work. I tink him most like hide."

"Why the mischief didn't you say so before?" asked Bart sharply.

"'Cos dere ain't no good place to hide yet, baas," replied Forty calmly. "We come to dat place pretty soon now."

Forty knew the river from its source to its mouth in the giant Niger, and Bart felt easier in his mind. They paddled on through the deepening gloom until, just before it became quite dark, Forty pointed to a creek mouth on the right.

"Dere am de creek, baas," he said.

"But how do you know they have turned up it?"

"I not know, but we find out pretty soon."

"How?"

"Lumbwa's kraal, him be little way up. Him tell us."

"But suppose they are not there?"

"Den we go on," said Forty simply.

It did not take much thought on Bart's part to be certain that Forty's plan was the best. The odds were strong that a boy like this Sam would make for a native village to spend the night in preference to making a lonely camp on the bank where lions or leopards might attack them. Besides, he would be saved all the trouble of cooking, and this would certainly appeal to such a lazy chap and one already tired by a long day's work.

"What sort of man is Lumbwa? Bart asked Forty as they headed for the creek.

"Him pretty good man," allowed Forty, and Bart, feeling more satisfied about Jet's safety, paddled on.

The creek, though narrow compared with the river, was quite fifty yards wide, and the water was deep and open with high banks, so in spite of the darkness they got on at a good pace, and after half an hour's paddling saw lights ahead.

"Dat him kraal," said Forty briefly.

The lights grew stronger, and Bart stopped paddling.

"I say, Forty, they've got some thundering big fires in the village," he said in a puzzled voice. "What does it mean?"

"I tink him mebbe lions," said Forty.

Lions were not particularly plentiful in this country, but there was always the chance that a wandering band of the beasts might have attacked the cattle belonging to the tribe, and this seemed to be the only possible explanation of the huge fires which flung a lurid glow far across the water and made the dark tree trunks stand out like black bars against the crimson flames. As they came nearer they saw that the place was surrounded by a huge hedge of piled up thorns.

"Dem lions pretty bad, baas," remarked Forty. "Dey nebber had boma like dat last time I come here."

But Bart was not listening. He pointed eagerly to the canoes drawn up on the sloping bank below the village.

"They're here, Forty," he said sharply. "There's our canoe."

"Dat right, baas," replied Forty. "Dat Baas Jet's canoe all right." He grinned.

"I 'spect he be mighty cross because you found him."

Bart's lips tightened. "I don't care how cross he is. He's coming back with us to-morrow."

They ran the canoe on the beach and stepped out. As they did so there came a yell of terror from somewhere above, then a gun roared—both barrels—and they heard the shot rattle among the tree trunks.

At sound of the shots Bart pulled up short, but Forty walked quietly on.

"Dey no shooting at us, baas. Mebbe dey fighting dem lions."

"There's something up anyhow," said Bart uneasily as he thrust cartridges into the breech of his rifle. "Where are they all? There's not a soul in sight."

"I 'spect dey in dem houses," replied Forty.

The street was deserted, and it was quite clear that something odd was afoot, for as a rule every soul in the place would have been down at the water's edge to stare at newcomers, more especially at a white man. Bart stopped again.

"Here's Jet!" he said sharply, and as he spoke Jet Norcross, gun in hand, with Sam behind him, came into the street, followed by a crowd of natives carrying spears.

"It's all rot," Jet was saying angrily. "Nothing but a false alarm. Tell 'em, Sam, and tell 'em I'm jolly well going back to bed."

And then he saw Bart, and he too stopped short and stared—glared would be a better word.

"W-what are you doing here?" he stammered. Then he grew angry. "If you think I'm coming back with you you're all washed up."

"I don't think," said Bart. "I know. We're going up river again in the morning."

Jet's dark eyes flashed, and he strode up to Bart in threatening fashion. Bart stood quite still.

"Jet," he said quietly, "if you start a row here these natives will join in, and the chances are we shall both be scuppered. Let's go into your hut and talk it over."

Jet hesitated, but something in Bart's manner made it plain that he was speaking the truth.

"All right," he said with a scowl. "Here's my hut."

"You'll have to wait a few minutes," said Bart, "until I have made my salaams to the Chief. It's considered the worst of bad manners in these parts to speak to anyone in a village until you have greeted the Chief and asked his permission to remain."

"Lumbwa, him lib in dis house," said Forty in Bart's ear. Then in a lower tone. "It all right, baas. I watch dem white boy."

Bart went straight into the large hut which Forty had pointed out. It was built like an enormous beehive, and in the centre was a small, clear fire which gave light enough for Bart to see an immensely stout black man squatting on a skin kaross on the other side. Behind him crouched a couple of women.

"I see you, Chief," said Bart, using the ordinary greeting, and then it occurred to him that probably Lumbwa did not know a word of English. To his great relief, the fat man understood.

"How do you do?" he answered politely, and signed to Bart to sit down. "You come find other white boy?"

"Yes," said Bart. "He got lost, so I came to take him back to camp."

"I mighty glad you come," said Lumbwa in surprisingly good English. "Now you help me kill this thing what eating all my people's cattle."

"A lion?" asked Bart politely.

"It no lion. My people no afraid of lions. This thing worse than all lions in the bush." He lowered his voice and looked round cautiously. "This be chimiset."

He shook like a great jelly, and Bart saw the two women shiver at the dreaded word. It was one that he himself had not heard, yet he knew that he must not betray his ignorance.

"That is bad," he said gravely. "But surely you are safe enough, for I see you have a fine thorn hedge all around the kraal."

"Chimiset, he no care for hedge," replied Lumbwa quickly. "He come through easy as you come through that door. He come through wall of hut; he come through anything. I show you."

He struggled to his feet, and ordering a man on guard outside to bring a torch, led the way towards the zareba surrounding the village. It was the finest thing of its kind that Bart had ever seen, six feet high and more than that through. A palisade of poles held it in position, and the thorns were packed in such fashion that it did not look as if any living thing could penetrate it. Certainly no lion would tackle such a barrier.

Yet at the bottom of it was a hole, a tunnel burrowed right through the mass of thorns, and the red torchlight showed marks of enormous claws which Bart saw were far bigger than anything a lion could have owned.

"He come through two nights ago and lake a girl," Lumbwa said. "He take her right away. We never see her again."

Bart began to realise that he was up against something very much out of the common. He had heard from his father tales of strange and unknown animals in the African wilds—of the ngoloko, the man ape of the Isarsu Hills, of the nunda, the huge grey cat, big as a tiger, that haunts the forests of Portuguese East Africa, and the irizima, the mystery beast of the Congo swamps. And he himself had seen enough of Africa to know that some of these monsters might really exist, for after all the okapi and the bongo and the pigmy elephant have only recently been discovered.

"He must be very big," he ventured.

"He is bigger than a lion and his mouth is red like coals of fire," said Lumbwa impressively. "He a devil and fear nothing. White boy, kill him with your rifle, and all that Lumbwa has is yours."

Bart of course was anxious to get away as soon as possible, but it came to him that the friendship of this Chief might be very useful in the big adventure that was before him.

"I will try, Chief," he answered, "but first I must sleep, for since morning I have paddled for twelve hours, and my eyes fail for weariness. Tell me, at what time does the monster come?"

"In the dark hour before dawn. Nine times he come, and four oxen he took and three of my people."

"Then rouse me two hours before dawn, Chief. Meantime give me food and a place to rest."

"It is done," said Lumbwa, and done it very soon was.

Bart was led to an empty hut where the best the village could provide was set before him and a bed made for him of boughs and skins. Bart ate fish that was quite good, refused stew which he felt sure was made of monkey, and ended up with some capital bananas.

"And now I've got to go and see Jet," he yawned. "What a nuisance the chap is! And I'm so sleepy."

Just then Forty came in.

"Him white boy, him sleep," he remarked.

"And a jolly good job too," said Bart. "Keep an eye on him, Forty."

"I do better dan dat," replied the big nigger with a twinkle in his eyes. "I hide him canoe. Now you sleep, baas. Mebbe dat ting no come to-night."

"I hope to goodness it won't," Bart answered fervently, and dropping on the bed was asleep in a minute.

BART woke to a noise like nothing on earth—shrieks and yells, beating of drums—a most awful racket. Forty came bounding in.

"Him come, baas."

"I knew it would," said Bart crossly, as he jumped up and pulled on his boots. "What is it, Forty?"

"I tink him all same nandi bear."

Bart whistled. "I've heard of that all right," he said softly, as he picked up his rifle. "Where's Jet, Forty?"

"I tink him asleep," said Forty as he followed. "We no want him anyhow."

The moon was high in the sky, and its white light shone on the bare clay of the one wide street and the little beehive-shaped huts on either side. It shone on the black shiny skins of men running towards the landward side of the thorn fence, and it showed Bart the portly figure of Lumbwa who, armed with an ancient matchlock, marched heavily after them.

"Good stuff!" said Bart to himself. "The old lad's got pluck." He ran after him. "Is it the chimiset, Chief?" he asked.

"It be chimiset," panted Lumbwa. "We kill him this time."

"I'm sure I hope we do," said Bart to himself, but he had his doubts.

At the upper end of the village all was excitement. The men were jabbering and shouting, but Lumbwa got hold of one and questioned him.

"He come another way this time," he explained to Bart. "He try to get into hut, but this man see him and throw fire at him, and he go out again. I show you."

Sure enough, the beast, whatever it was, had driven another hole clean through the thorn zareba and gone straight up to one of the huts. Bart saw where it had started to break through the thick, sun-hardened clay with which the wall was daubed. The man who had seen it and thrown the torch was ashy with fright. But the fire, which seemed to be the only thing the chimiset feared, had driven it off.

Bart pulled himself together and told Lumbwa to gather his men and order them to follow. They were to bring torches and drums. All were very badly frightened, but they obeyed their Chief's orders. Bart, with Forty on one side, Lumbwa on the other, led the way. Bart had his repeating rifle, Forty carried a gun. The gateway, blocked at night with thorns, was opened, and they went out into the bush.

Outside they came upon the tracks of the monster. The huge footprints were nearly four times the size of those made by a lion and showed the marks of three great clawed toes. Bart had never dreamed of such a terrifying spoor, and even Forty was not happy.

"I tink him debbil beast, baas," he said in a low voice, and Bart felt inclined to agree.

There was not much underbrush near the village, and in the sandy soil the tracks were plain as print. They led south towards a low kopje or mound standing above the river and about a mile from the village. The kopje was covered with thick bush, into which the tracks passed and disappeared.

Bart had once seen a hunter go into palm scrub after a wounded lion, but he himself had no idea of going into the place after the chimiset. The scrub was thick as a hedge, and it was impossible to see more than a few feet in any direction. He pulled up.

Suddenly a mongrel dog belonging to Lumbwa darted forward and ran into the scrub. A moment later came the most appalling cry that Bart had ever heard. It was not a roar, but a howl. Bart had heard a rogue elephant trumpet, and that was pretty bad, but it was music compared with this noise which echoed in horrifying fashion through the moonlit bush. Immediately afterwards came one sharp yelp, then a thudding crash as some monstrous form forced its way through the undergrowth.

The men fell back, and it looked as if they were all going to bolt, but old Lumbwa shouted at them, and they stood.

"I tink dis one debbil place," growled Forty. "What we do now?"

Cold chills were coursing down Bart's spine. He heartily agreed with Forty, and felt just as much like running away as any of the natives, but he knew he had to keep his end up, and for a second time managed to pull himself together.

"There's only one thing to do," he said firmly. "We must fire the bush and shoot the thing as it comes out."

"Suppose him come out wrong side?" suggested Forty, and Bart at once saw the sense of the suggestion. He and Forty were the only ones who had guns, for you could hardly count Lumbwa's ancient matchlock.

Lumbwa spoke up. "Wind, he blow to river, he come out that side."

There was not much wind, but as Lumbwa said it was blowing towards the river, so Bart and Forty went round the little hill to the far side. Here Bart found a narrow open space between the thick bush and a low bluff some ten feet high which dropped sheer into the dark, still water.

"We're bound to see him if he comes out here," Bart said. "Give them a shout, Forty."

Forty shouted, and a moment later there came the crackling sound of fire among green leaves: snaps like pistol shots followed by leaping tongues of flame. Then drums were beaten furiously, and there was a chorus of shouts and yells.

"That ought to do the trick," said Bart, and Forty nodded.

There was a very grim expression on the face of the big negro, and Bart wondered if the man was as scared as he was himself. That howl had shaken him up badly—that and the gigantic size of the spoor of the mysterious beast.

The flames rose higher, and great clouds of smoke reddened with the fire beneath rose above the blunt head of the kopje. The drums thundered, and the natives yelled hoarsely. The din was terrific, and Bart felt that no wild thing—not even such a thing as the chimiset—could stand it for very long.

"Him come," said Forty suddenly, and pointed.

Less than fifty yards away the thick brush parted, and out of it the monster pushed its way. In the crimson glow it loomed gigantic, and its appearance was so terrible that for a moment Bart was utterly unable to move.

The chimiset stood little higher than a lion, but its length and bulk were horrifying. Its shape was anything but lion- like, more resembling that of a monstrous hyena, and it was covered all over with coarse hair of a dirty ash colour. Its head was huge, with jaws which looked capable of snapping a man's body in two, and its eyes shone red as burning coals. For a few seconds it stood quite still, swinging its great head from side to side; then it saw Bart and with a blood-curdling snarl turned and came straight at him.

"Shoot, baas! Shoot!" cried Forty, and Bart, flinging his rifle to his shoulder, fired twice in rapid succession.

Both bullets struck the chimiset. He heard them thud home. But for all the effect they had they might have been pellets from a pop gun. The monster came on.

Bart fired and fired, but still the monster came on, and he had a horrible feeling that I was quite useless, and that nothing short of a machine-gun would stop it. The evil glare in its eyes paralysed him, the foul carrion reek of the creature poisoned the air, and he felt as if he were in the grip of some horrible nightmare.

The beast was almost upon him, and penned as he was between the thick brush and the sheer bluff, there was no way of avoiding it. Aiming straight between the wide-open slavering jaws, he pulled the trigger for the last time, but only a click answered. The magazine was empty.

A huge hand caught him by the shoulder and thrust him aside into the thorny bush, and Forty's double-barrelled gun flashed and roared. At such close range the charges of shot drove home like bullets. They smashed into the chimiset's head, blinding it completely. Bart saw the creature rear up on its hind legs, and again it howled in the same blood-curdling fashion as when it had killed the dog.

For a moment it towered above them, its mighty bulk dwarfing even the great negro. Forty was feverishly reloading, but there was no need, for suddenly the beast swayed over sideways, and rolling over the edge of the bluff fell with a mighty splash into the deep, dark water beneath.

Bart scrambled up. His throat was dry, and his knees were weak. Forty looked at him solemnly.

"Chimiset, him done," he remarked.

Bart said nothing—merely thrust out his hand, and as Forty took it a broad grin split his black face.

"What was it?"came a sharp, high-pitched voice from behind, and there stood Jet looking very white and shaken, but carrying his rifle.

Bart smiled. "That was your false alarm, Jet."

"Ugh, I never knew such things lived."

"Him don't lib," observed Forty. "Him bery much die."

Jet shivered. "I saw it all," he said in a low voice. "But I couldn't shoot for fear of hitting you. I—I was scared stiff," he confessed.

"And so was I, Jet," agreed Bart. "And you're quite right about not knowing that such things lived, for this is the first chimiset that any white people have killed."

"What do you call it—chimiset?"

"Yes, or nandi bear, but it's really some sort of giant hyena."

"Him Lumbwa come," Forty interrupted. "I tink him pretty pleased."

Lumbwa was pretty pleased. The stout Chief was fairly beaming with joy and relief.

"White boy, I say I mighty glad you come. Now I more glad than before. Now because you so brave and kill chimiset Lumbwa's people all safe. I tell you all I have is yours. I want you ask something so you know Lumbwa keep his word."

"All right, Chief, I'm going to ask something at once," said Bart. "I want your men to get hold of the dead beast. I'd like his skin or at any rate his head."

Lumbwa stepped over to the edge of the bluff and raised the torch he carried so that its smoky flame flung a red glare across the black river. He shook his great head.

"It no good, white boy," he said. "You look."

And Bart looking saw that it was indeed no good, for the dark water was alive with crocodiles which were tearing savagely with their huge curved teeth at the remains of the chimiset.

"Brutes!" snapped Jet as he raised his rifle and fired at the biggest of them. "Did you ever hear such rotten luck? To kill a thing like that and not be able to get even a hair of it!"

"Never mind," said Bart. "It's dead anyhow, and that's the great thing. Now let's get back. I expect we can all do with a bit more sleep."

The return to the village was a triumphal procession, and when they reached the place and the women learned that their terrible enemy was really dead they went mad with joy.

"Dem make worse row dan chimiset," remarked Forty, and Bart had to explain to Lumbwa that he wanted a little more sleep before he could get them to keep quiet.

The sun was high in the sky before he turned out in the morning. Forty brought him cool water from the river and poured it over him, and after he had had a good breakfast he felt fit and fresh.

"Now I must go and have a talk with Lumbwa," he told Forty.

"No need you go; him come to see you, baas," Forty answered, and sure enough here was the fat Chief himself at the door of the hut. "Him bring you presents," added Forty in a lower voice. "You take 'em, baas, or he be sorry."

Lumbwa's presents were a very fine leopard skin, two quills of gold dust worth perhaps a couple of pounds each, and two large and shiny emeralds. These Bart spotted at once to be nothing but green glass, but he accepted them with many thanks; then he got Lumbwa to sit down, and began to tell him of his troubles. The Chief shook his great head.

"Kasoro, he very bad man," he said. "He robber. He kill you all if you go fight him."

"I'm sure he would if he got the chance, Chief," Bart answered. "But we don't want to fight. All we want is to get our friends away from him."

"That very hard. I no think can do," replied the Chief, looking very solemn. Suddenly his face cleared. "I know how I help. I send Aruki along you."

"Does he know the lie of the land?" asked Bart eagerly.

"He no lie. He good man," answered Lumbwa rather sharply.

"I didn't mean that," Bart explained. "I meant, does Aruki know the way to Kasoro's kraal and how we can get near it without being seen?"

Lumbwa nodded. "He know it all. He slave to Kasoro one time."

"That's topping," exclaimed Bart. "We shall be very grateful if you will let him come with us, and we will pay him well."

"You no pay. I pay," said Lumbwa, and Bart thought it best to let it go at that. Lumbwa rose heavily to his feet. "I send him you," he promised as he went away, and a few minutes later Aruki arrived.

He was a wizened little brown man whose back still showed scars of old beatings. But his eyes were bright as a robin's, and he walked lightly as a cat. Bart took to him at once, and so did Forty.

Aruki was not only willing to go with Bart, but eager. Bart saw that he was a wanderer by nature, and that he was bored by living in this lonely village. He had knocked about a lot in the course of a longish life, had acted as porter in several big safaris, and spoke good English.

"I like see him Kasoro's head cut off," he said briskly. "Him very bad man. Him beat me bad till I run away. I show you way."

"Then the sooner we get off the better," said Bart.

Aruki's bright eyes shone. "I ready this minute," he said. "I lib for canoe." He was off like a shot, and Bart turned to Forty. "The next job will be to get Baas Norcross," he said.

Forty winked. "Him come all right, baas. Him got to come."

"Why?" asked Bart.

"No oder ting for him to do. Dat nigger Sam, him gone."

"Sam gone! Where?"

Forty grinned broadly. "You no ask so many questions, baas. I say dat white boy, him come, so you no worry."

Sure enough, Forty was right, and Jet, when he found that his only choice was between staying in Lumbwa's kraal or going back with Bart, chose the latter. But he glared at Bart and would not speak, and Bart felt sure there was fresh trouble brewing.

Not that Bart cared much, for he was so delighted to have got hold of Aruki. Bart was really sorry to part from Lumbwa, and it was quite plain that the stout Chief was equally sorry to lose Bart. He came down to the landing to see the canoe off.

"You come see me again," were his last words. "I not forget you, never."

It was past ten before they got off, but Bart did not mind for in any case they could not do the journey upstream in one day, and with four paddlers the work would not be nearly so hard as it had been on their rapid journey down. Aruki proved to be a capital paddler, and the more Bart saw of him the better he liked him. The little man was much more intelligent than the negroes with whom he had been living, and keen as a ferret.

"I tink him good man," said Forty aside to Bart, and Bart knew that he could not give higher praise.

The flood had run down, and that night they found good camping ground on a high bank. There was no need to hunt, for Lumbwa had filled the canoe with yams, bananas, and fish. So they supped in comfort, slept well, and by dint of starting early reached the camp before sunset.

Mr. Bryson never said much, but this time Bart did get a word of praise.

"Good lad, I knew I could depend on you," said his father, and Bart was as pleased as if he had been given a medal. "And who is this?" asked Mr. Bryson, looking at Aruki.

"The man who is going to show us the way to Kasoro's place, Dad. He's been a slave there himself, and he won't be sorry to get a bit of his own back."

"This is luck indeed," said Mr. Bryson warmly. "Bring him into my tent, and we will talk it out."

Aruki had not boasted when he had said he knew Kasoro's stronghold. He explained that the kraal stood near the head of a valley running up into the Mountains of the Moon. On three sides it was protected by cliffs and in front by a strong stockade.

"No good fight up that way," said Aruki. "Kasoro, he kill you all before you come near."

Mr. Bryson frowned. "Then what the mischief are we to do? Isn't there any way of getting round up the hill above the kraal?"

"Dere one way, baas," replied Aruki, and his wizened little face turned suddenly grave while his voice took quite a new tone. "But it no very nice way."

"I don't care if it's a tight rope," said Mr. Bryson, "so long as we can use it."

A shadow of a smile crossed Aruki's face. "It worse dan tight rope, baas. It tagati."

"Tagati" means bewitched, but Mr. Bryson did not laugh. He knew too much of Africa and of the queer things that happen in the heart of the Dark Continent.

"Tagati," he repeated. "Then would you refuse to go there, Aruki?"

"I no go alone," replied the little brown man, "but I no so scared if white baas go too."

"Good man," said Bart's father. "But we must keep any word of this from our boys. You will be careful not to say anything, Aruki?"

"I be careful," promised Aruki, "but I tink dey find out all right soon as we get dere. It very bad place," he added gravely.