RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

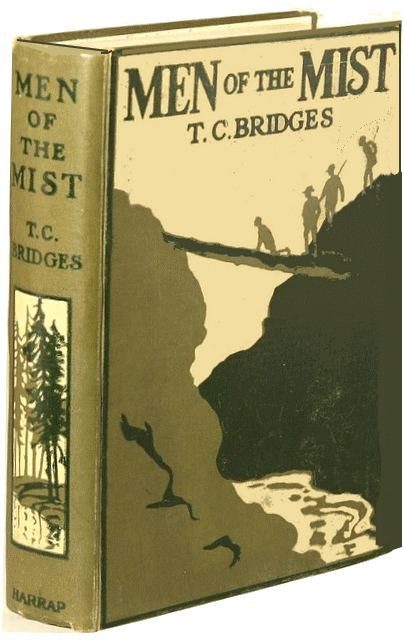

"Men of the Mist," George G. Harrap & Co., London, 1923

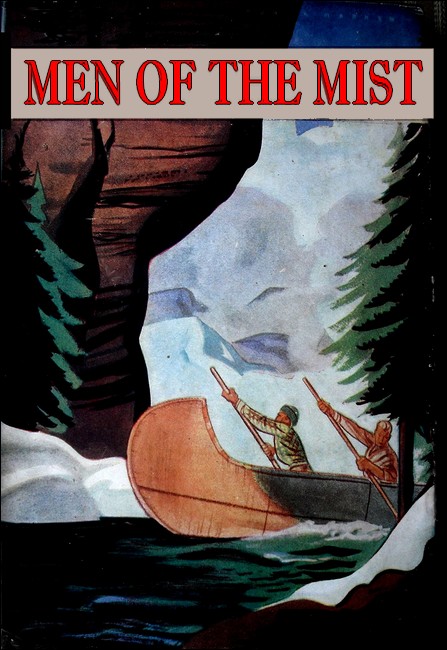

"Men of the Mist," Collins, London, 1947 Reprint

Frontispiece.

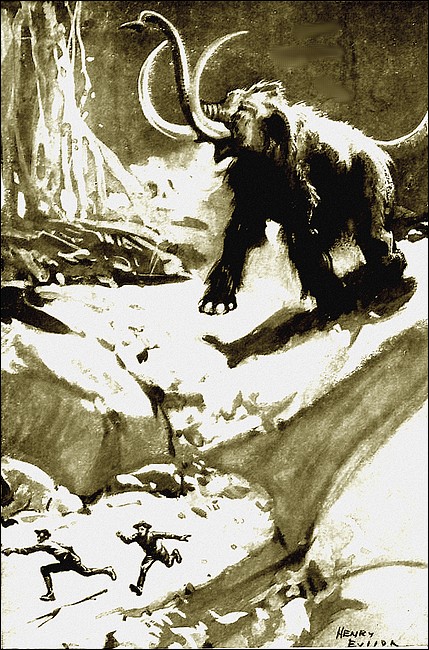

The giant came at a shambling gallop.

TEA at Wasperton School was nothing but thick hunks of bread and margarine and an evil-looking black mixture served in huge metal teapots. The food was so bad that the boys could hardly eat it, but they dared not complain, not, at any rate, so long as they were under the hard eyes of their master, Mr Silas Crayshaw. For his eyes were no less hard than his cane—and never a day passed but some of them felt the sting of that.

Among the forty or so boys who sat at the two long tables were a couple who somehow looked different from the rest. In spite of their shabby clothes and patched boots, there was an air of breeding about Clem and Billy Ballard.

As Clem took his place beside his brother, Stiles, the grimy old school porter, came along and dropped a letter by his plate. Clem glanced at the address, and slipped the letter into his pocket. Pendred, a big, sullen-looking youth who sat opposite, laughed unpleasantly. "Scared to open it, I suppose?" he remarked. "Don't want us to see the broad arrow on the paper."

Clem went oddly white, but Billy's eyes flashed and the colour rose hotly in his cheeks. Clem caught him by the arm. "Sit still, Billy. Don't pay any attention to him," he said coolly. "It's from Uncle Grimston," he added in a whisper.

Just then Mr Crayshaw came in, and Pendred subsided. He was not going to risk a cut from the master's cane.

The meal went on in absolute silence, and the moment it was over the two Ballards hurried out. "Let's go down to the quarry," said Clem, and Billy, merely nodding, dropped into step.

Wasperton was near the big manufacturing town of Marchester, and the whole countryside was foul with soot and smoke. The two boys walked down a grimy lane, turned into a bare-looking field, and passing through some gorse and a clump of half-dead trees reached the edge of an old stone quarry, at the bottom of which was a deep pool of sullen greenish water. There they plumped themselves down on the grass. "What's he say?" asked Billy.

Clem tore open the envelope, and had hardly begun to read before he stopped with a gasp.

"What's the matter?" demanded Billy sharply.

"He—he—can't have us back, Billy! We—we've got to spend the holidays here!"

"What! Here at Wasperton?"

"Yes. That's what he says," Clem answered, with his grey eyes fixed upon the fatal sheet.

"Oh, he can't! He can't mean it!" groaned Billy.

"It's plain enough," said Clem bitterly. "He says he can't have us knocking about the place."

"He always hated us," said Billy fiercely.

Clem shrugged his shoulders. "Well, he's kept us since Mother's death. I suppose we ought to be grateful."

"What's the good of his keeping us?" cried Billy, "I'd sooner work as an errand-boy in a shop than go on like this. The school is a pig of a place; we don't learn anything, there are no decent games, and I hate the very sight of it, and of Crayshaw too."

In his excitement Billy sprang to his feet and went stamping up and down. "And the chaps jeering at us about Father!" he went on. "As if it was his fault or ours that they sent him to prison."

"Steady, Billy!" said Clem. "It's no good getting excited."

"But I can't help it!" retorted Billy. "It isn't fair. Everything's gone wrong since they tried Father for taking money which you and I know he never touched. And now to keep us in this place all the holidays! It's the limit, and I'm not going to stand it!"

"Look out!" cried Clem suddenly and leapt to his feet. He was just too late, for Billy had gone too near the edge, and with a deep crunching sound a great piece of turf had broken off and slipped down, carrying Billy with it.

"Billy! Billy!" cried Clem in horror. When he reached the edge he fully expected to see his brother plunged into the depths of the pool thirty feet below, and his relief may be imagined when he caught sight of him clinging to a narrow ledge only a yard or so down. In a flash he had flung himself on his face, and reaching down caught hold of Billy. "Hang on!" he cried. "Hang on, Billy! I'll get you up!"

But when he tried to do so he found that it was out of the question. The weight was too much for him to lift, and Billy could get no foothold. With a sinking feeling of horror, Clem realized that unless he kept quite still he himself would be pulled over the edge, and both would plunge to destruction in that noisome green water so far below.

"Help!" he shouted at the top of his voice. "Help!"

Clods of earth fell away beneath him. Another slip threatened. Billy looked up at him with agonized eyes. "Let me go, Clem!" he said. "Let me go! I shall only drag you down."

But Clem's teeth set hard. "No!" he answered curtly. "Hang on!"

More earth fell. Clem was slipping. Another moment and it would have been all over, when he felt a tremendously powerful grip on his legs. "Hang on, sonny!" came a cool, deep voice. "I reckon I can pull ye both up if ye'll hold still."

Such a pull! It was like that of a steam-crane. Clem's muscles cracked, but he held on, and next minute he and Billy were both safe on firm ground.

"There, that's all right," said his rescuer, as calmly as ever, and Clem, recovering a little, looked up into the face of a man of middle height, square built, and evidently of immense strength. His features were blunt, and tanned to the colour of an old saddle, but his eyes, of a singularly clear blue, held that curiously far-seeing look peculiar to men who spend their time entirely in the open air. He was dressed in a ready-made blue serge suit much too tight across his immensely broad chest.

"Thanks awfully," gasped Clem. "You saved us both. I say, you are strong!"

The other smiled, and it was a very pleasant smile which lit up his whole face.

"Glad I came along in time, sonny. But you're all right now. Well, I guess I'll be going. Good evening."

But Clem caught his arm. "Please tell us your name," he begged.

The big man smiled again. "Bart, I'm called—Hart Condon. And what's yours?"

"Ours is Ballard," replied Clem. "I'm Clem, and this is my brother Billy."

Condon's blue eyes widened. Clem almost thought he saw him start slightly. But all he said was, "I'm mighty glad to have met you. You're from the school, I reckon?"

"Yes," replied Clem. "I say, you come from America, don't you?"

"That's so, son. Say, I'll walk up as far as you're going."

So the three walked back together, but Clem had no chance to pursue his inquiries, for Condon did most of the talking. He asked many questions about the school, and by the time they reached the gates had got the boys to tell him practically all about it and about themselves. They had told him how their father had been put in prison for a theft he had never committed, how their mother had died of grief, and how their uncle, Mr Robert Grimston, a hard, mean man, had taken charge of them, and put them at this wretched school, where they had now been for two years.

"But your dad escaped, didn't he?" asked Condon.

"Yes. But how did you know?" asked Clem quickly.

"Guess I read it in the newspaper," was the reply.

"Yes," said Clem. "He got away more than eighteen months ago, and they never caught him. They say he's gone to Australia. I do hope he's safe there."

"Mighty good place to get to, I reckon," said Condon. Then he stopped, and offered his hand first to Clem, then to Billy. "I reckon we'll meet again some time," he said, and, turning in his quick, quiet way, was gone.

"What a topping chap!" said Billy to Clem.

Clem nodded. "A real good sort," he agreed, "and he came just in the nick of time."

Billy nodded gravely. "I only hope Crayshaw doesn't hear of this. He'll stop us going down to the quarry, and it's the only place we can get to ourselves."

"Why should he hear?" asked Clem.

"Look at your clothes," responded Billy.

Just then a cracked bell began to ring.

"There's the bell for school!" exclaimed Clem. "We must hurry."

All the boys sat together in the large classroom for evening preparation. Every one was very quiet, for Mr Gorton, the assistant master, was at the desk, and every one knew that his cane was as handy as Mr Crayshaw's. The silence was broken only by the scratching of steel pens and the rustle of the pages of dog's-eared books.

And so the minutes dragged on until the hands of the big clock pointed to a quarter past eight. Only a quarter of an hour now, and then came bedtime.

The sound of the door opening made every one look up, and in came Stiles, the dingy old manservant, and went up to Mr Gorton.

He gave a slip of paper to the master, and Mr Gorton glanced at it. His big voice boomed out. "Ballard senior and Ballard junior."

"Yes, sir," answered the two boys, standing up.

"You are both to go to Mr Crayshaw's room."

As the two left their seats Billy glanced at Clem. "What's he want?" he whispered to his brother.

"Probably he's heard from Uncle too," was Clem's answer. "Or else Pendred has sneaked about our going down to the quarry. He's always spying on us?"

MR CRAYSHAW'S study was a large, untidy room which reeked of tobacco, and Mr Crayshaw himself was a tall, bony man who wore a tail-coat which had once been black but now was green, and a sort of fez cap on his bald head. He had bushy eyebrows and deep-set eyes. As Clem and Billy came in he was sitting at his desk. He looked up and stared at them.

"What's the matter with your clothes, Ballard senior?" he demanded.

Clem held himself very straight. "I had a fall, sir," he answered quietly.

Mr Crayshaw grunted. "Fighting, I suppose, but you need not be afraid," he said. "Though no doubt you richly deserve it, you will not get a caning this time." He picked up a sheet of paper and adjusted his spectacles. "I have a letter here from your uncle," he went on. "It seems he wishes to take you away from the school."

"Take us away!" echoed Clem, hardly able to believe his ears.

"Yes," snapped the master. "In my opinion a very foolish proceeding, but since he has sent a cheque in advance for next term's fees I have no choice but to let you go."

He went on talking, but the boys hardly heard. The one fact they realized was that they were to leave Wasperton, and this alone seemed too good to be true. It was also utterly amazing, for the letter telling them they could not come home for the holidays had only just arrived.

"You will pack your things to-night." were the next words Clem caught. "You are to leave in the morning." He glared at the boys as though they had done him some injury, but it is quite certain that neither Clem nor Billy took the faintest notice of his expression.

The master turned again to his desk and picked up an envelope. "I am to give you this," he added, handing it to Clem. "It contains your tickets and money for your journey. You are not to open it until you arrive at the station to-morrow morning, where you will catch the eight-thirty train. You quite understand?"

Clem was almost breathless, but somehow managed to get out, "Yes, sir. Thank you, sir."

"Then good night, and good-bye, for I shall not see you in the morning. I only hope that you will both benefit by the useful tuition which you have received in my establishment."

He extended a large, cold hand, which the two boys shook in turn; then somehow they found themselves in the passage outside the study door. They were both gasping like fish out of water. Billy turned to Clem. "I—I say, Clem, it's a dream, I suppose. It can't be real," he said hoarsely.

Clem held up the envelope. "This is real, Billy. No, it's true. It's really true."

"B-but where are we going—back to Uncle Grimston's?"

Clem shook his head. "There wouldn't be all this mystery about it if we were," he answered. "Besides, his letter to me said he didn't want us at his house for the holidays."

"Then where?" demanded Billy.

"What does it matter? Anything will be better than Wasperton. Come on. Let's pack."

It was a job that did not take long, for one small box easily held all their worldly goods.

"And we don't even know how to label it," said Billy, when it was done.

"We shall know in the morning," Clem answered. "Now we'd better turn in."

Luckily for them, the rest of the dormitory were already in bed, and, barring a sneer or two from Pendred, they were not molested. But neither of them slept much that night. They were far too excited. Stiles called them at half-past six, and they slipped out like mice. The other boys were still asleep, and Clem and Billy were not sorry. But not until they were in a cab and on their way to the station were they able to believe that they were actually clear of Wasperton.

It was barely eight when they arrived, and except for a solitary porter there was not a soul on the platform. Billy seized Clem by the arm and dragged him into the deserted waiting- room. "The envelope, Clem—we can open it now," he said sharply.

Clem's fingers were not quite steady as he tore open the envelope. It contained a sheet of paper, two tickets, and five pounds in Treasury notes. "The tickets—where are they for?" demanded Billy.

Clem held them up. "Lime Street Station, Liverpool," he read.

The two boys stared at one another, but neither spoke. Then Clem unfolded the sheet of paper. On it were typed these words: "Your passages are booked for New York on the Pocahontas, sailing at 4 p.m. on Wednesday afternoon. You will be met at Liverpool. The password for which you will be asked is 'Potlatch.'"

There was no signature to this startling message, no address, no date. Clem and Billy stared at one another in mute amazement. "The Pocahontas—New York!" Clem muttered at last.

Suddenly Billy snatched off his cap, flung it in the air, and gave a whoop which made the solitary porter drop a large parcel he was carrying and turn quite pale. "Hurray!" he shouted. "No more Uncle Grimston! No more Wasperton! Three cheers for America!"

The porter came up quickly. "Here, I say, young feller!" he said, in a scandalized tone. "If you wants to make a noise like that you better go out on the road and do it. This here's the private property of the railway, and lunatics like you ain't allowed here."

Billy turned a beaming face on the man. "I can't help it, porter. I'm not loony—only happy. So'd you be if you'd just got away from a place like Wasperton, and especially if you'd been there for nearly two years."

The porter's expression changed and became quite sympathetic. "Oh, you're from Wasperton, are you? Yes, I shouldn't wonder if you was glad to clear out. They do say as it's a sort o' 'Dotheboys Hall,' like Dickens wrote about." He paused. "I say, you bain't running away, be you?" he asked quickly.

"No, indeed!" replied Billy. "We're going to friends in America. See, here are our tickets to Liverpool."

The porter inspected the tickets and nodded. "They're all right. Now you'll go right through to Crewe and change there, and you'll get to Liverpool just after one o'clock. That'll give you plenty of time to get some dinner afore you goes aboard. Tell you what, I knows the guard aboard this train. I'll tip him a word to look after you."

"That's frightfully good of you," said Billy gratefully, and the good fellow stood chatting with them until passengers began to arrive and he had to get busy. But he did not forget his promise, and when the train came in introduced them to the guard, who put them in a carriage near his van, and was kindness itself.

It is quite safe to wager that two happier passengers than the young Ballards were not carried by any train in England that morning, and when they were swept away from the grimy surroundings of Marchester, and through the lovely hills of North Wales, their delight was beyond words.

Billy was constantly sticking his head out of the window to admire one thing or another, but in between he and Clem talked things over again and again. But the more they discussed the matter the worse puzzled they became. "It's no use troubling our heads," said Billy at last. "The paper says that some one is going to meet us at Liverpool. Whoever it is, we can ask him where we are going."

The train pulled into the big junction at Crewe, and the kindly guard saw the boys and their box across into the other train, and shook hands with them and wished them luck. Then they were off again, the express racing north for Liverpool.

It seemed a very short time before they reached the huge Lime Street Station, and there they stood on the platform beside their box, waiting alone in the midst of hurrying crowds, and, to say the truth, feeling a little lonely.

"Is your name Ballard?" Clem glanced up quickly, to see a quietly dressed, middle-aged man who looked like a lawyer standing beside him.

"Yes, sir," he answered.

"And the word?"

For a moment Clem wondered what was meant—but only for a moment. "Potlatch," he answered.

The other smiled slightly, and motioned to a porter to take the box. He led the way to a waiting taxicab, and they drove off.

Billy was the first to speak. "Where are we going, sir?" he asked.

"To get some dinner," was the reply.

Something in their new acquaintance's tone checked further questions, and presently the taxi pulled up at a small, quiet- looking hotel. Here the box was taken out and left in the hall, the taxi-man paid and dismissed, and all three went into the coffee-room, where dinner was quickly set before them. It was a plain enough meal, but there was excellent roast beef with Yorkshire pudding and baked potatoes, and an apple tart with custard.

To the boys, accustomed to the greasy, ill-cooked fare at Wasperton, it was delicious, and both had two hearty helpings of each course. Their new friend hardly spoke except to ask them about their journey, and somehow neither cared to question him. The minute the meal was over he got up and looked at his watch.

"Now we have some shopping to do," he said, "and since we have not much time we must hurry."

He walked them off briskly, and took them into a big department store, where he spoke to a shopwalker. They were at once escorted to a lift and whirled to an upper floor, where they found themselves in the tailoring department. Piles of ready-made garments of all sorts were on the shelves.

"I want two suits for each of these boys," said their guide, "one of plain blue serge, the other of rough tweed, thick and warm."

He knew exactly what he wanted, and got it. Thence he moved to another department, where he bought flannel shirts, underclothes, socks, collars, and ties. The third place they went to was the boot department, where each was provided with two pairs of new boots and a pair of slippers.

Then Clem and Billy were hurried to a dressing-room, where the blue serge suits were ready, together with complete changes of everything, including boots. "Ten minutes to change," said their friend briefly. "Meantime I will get each of you a travelling bag, an overcoat, and a cap."

When Billy stood up in his new clothes and saw himself in the glass he shook his head. "I don't know myself," he said slowly. "Nor you either, Clem," he added. "I'm sure we shall wake up presently and find it's all a dream. It's much too good to be true."

As he spoke the door opened, and in came their lawyer-like friend. "No," he said, "it's real enough." He looked at them, and there was approval in his eyes. "You do me credit," he said briefly. "Your things are all packed. I will take you to the ship."

An hour later Clem and Billy stood at the rail, waving to their friend on the wharf, while the big ship, in tow of a tug, began to move slowly down the river.

ON the eighth morning after leaving England Clem and Billy came on deck to see the huge statue of Liberty towering in front of them, and beyond it the tremendous skyscrapers of New York outlined against a clear blue sky. They had enjoyed every minute of the voyage, but they were still as much in the dark as ever as to where they were going.

On the pier they found waiting for them a man from one of the great travelling agencies. He was an American, very brisk and cheerful. The Customs officials did not worry them much, and almost before they knew it they were driving through the roaring traffic of the capital of the New World to the great Erie Station.

"It's a real shame that there ain't time to show you boys something of this little old town," said their guide, "but my directions is to ship you right through to Seattle quick as you can go."

"Where's Seattle?" inquired Billy.

"A long way from here," replied the other with a grin. "You got to go clean across from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and that's a week in the train. Wal, here's the depot (station you calls it in England), and here's your tickets. I reckon some one will meet you at the other end."

"Who will meet us? Where are we going?" demanded Billy eagerly. The guide looked at him oddly. "If you don't know, I'm sure I don't," was all he said, and once more the boys found themselves starting off on a new journey without the faintest idea of their real destination.

Everything was new to them—the great steel carriages, so immensely larger than English ones, the big day coach, the 'sleeper' with its chairs and tables, the clanging of the engine bell, the negro porters, the boys who brought round newspapers, books, and candy.

Their tickets, they found, included sleeping accommodation, and the conductor had evidently been tipped to look after them. Whoever was paying for their journey was plainly not stinting money.

Over and over again the boys discussed the question of who could be their unknown benefactor. They were both quite certain that it was not their uncle Mr Grimston. Billy had suggested that it was possible they were going right across the Pacific to Australia to join their father, but Clem, older and wiser, had pointed out how unlikely it was that their father could have made money enough in less than two years to pay for all this. In any case, as he said, it would have been far cheaper for them to go by sea all the way. Clem's own idea was that it might be their father's brother, Lionel Ballard, who had sent for them. Neither he nor Billy had ever seen this uncle, who had left England many years earlier. All they knew was that their father had sometimes spoken of him.

On the sixteenth day after leaving England they reached Seattle, where they were again met by an agent of the same travel company, taken to a quiet little hotel, and ordered to remain until called for. They stayed there a week, living well and enjoying themselves immensely.

Then one evening they were just going to bed when there was a knock at their door, and in walked a broadly-built man with very clear blue eyes. Clem, who was in the act of pulling his boots off, sat quite still and stared, but Billy leapt to his feet. "Mr Condon!" he cried in utter amazement.

"Not Mister—just Bart," was the quiet answer, as Bart Condon shook hands gravely, first with Clem, then with Billy. He looked them over. "Well, to be sure, you have come on a whole lot! I reckon you're each seven or eight pound heavier than when I last seed you. You been weighed lately?"

"Weighed!" cried Billy. "We had something else to think of. How in the world did you come here?"

"Steamboat and train—same as you," replied Bart calmly. "Well, well, I'm mighty glad you're both looking so spry. How do you like this town?"

"The town's all right," said Billy, "and we're all right. But it's you we want to hear about. Did you know we were coming here?"

The blue-eyed man's expression did not change in the slightest. "Why, I won't go for to say I didn't," he replied.

Clem stood up. "Was it you took us away from Wasperton?" he demanded.

Bart shook his head. "No, sonny, it warn't me. But say now, I reckon you'd better get right to bed. The steamer leaves at seven to-morrow morning. Now good night to ye. I'll see as you're called bright and early."

He was as good as his word, and early next morning he and the two boys left Seattle aboard a small coasting steamer called the John P. Wilkes, and, working out of Elliot Bay, steamed north across Puget Sound, and so out into the Pacific.

The boys were wild with excitement, for now, for the first time since leaving England, they began to feel that they were getting out of touch with civilization.

Not that Bart told them a word of where they were bound. He would talk about anything except that. It was their fellow- passengers who made them feel it. They were nearly all men, and men of a sort which Clem and Billy had never seen before. There were Americans, English, Swedes, Norwegians, and a few French and Italians. There were also men whose dusky faces and sloe-black eyes showed that they had more than a touch of Indian blood in their veins. Almost all these men were big-muscled, deep-chested fellows dressed in thick flannel shirts and jean trousers, and wearing knee-boots, and handkerchiefs knotted round their necks in place of collars.

"Gold-miners, I believe," whispered Billy to Clem. "I say, do you think we can be going to the diggings?"

"The ship is bound for Dyea, in Alaska," replied Clem. "The purser told me. I say, Billy, look at those two who have just passed up the deck. Did you ever see anything like them?"

"Yes, I have. It was in a cinema," replied Billy as he watched them.

They were worth watching too, if only because they looked so rough and strange. One was a great big man with tow-coloured hair, hard, pale blue eyes, and a face that looked as if it had been carved out of stone; his companion was smaller, with a swarthy skin, a thick black moustache curled at the ends, and hair black as jet and clustering in tight ringlets all over his head.

By degrees the mixed company settled down, and by evening every one had found his place. The weather was very fine, and the ship ploughed steadily northward over a sea so calm that the brilliant stars were reflected in its placid surface. Supper over, Clem and Billy found the deck so crowded that they went aft and perched themselves on top of the emergency wheel-house. Here they sat silent, watching the sky and the sea.

All of a sudden they heard voices close by, and peeping over, saw two men standing and leaning over the stern, apparently watching the gleaming wake. They were the very same couple whom they had noticed earlier in the day.

Next moment the taller of these men spoke. "I take it, then, as you have some real information this time, Craze," he said in a low yet harsh voice.

"You can be very sure of that, Gurney," answered the other. "Surely you know me better than to think I should come all this distance on a wild-goose chase. I have it on good authority that the man whom they call 'the Big Britisher' is the one we want. There is a reward of a thousand dollars offered by the police for his capture."

"A thousand dollars!" repeated the tall man in a scornful tone. "You surely are not going to tell me that we are taking this trip for a thousand dollars! Why, that would barely pay our expenses!"

"I am telling you nothing of the sort," replied the black- haired man sharply. "There's ten times that money—maybe twenty—if we play our cards right."

"What do you mean, Craze?" questioned Gurney.

Craze leaned nearer, and spoke in a lower tone, yet the two boys were close enough to hear what he said. "Gold, Gurney. My information is that this man, who is a fugitive from justice, has struck it rich up there in the ranges. And once the police have him, what is to hinder us from restaking his claim?"

Gurney whistled softly. "That's a different story. Right you are, Craze. I'm backing you all the way through."

"What a beastly shame!" whispered Billy in his brother's ear.

But Clem pinched his arm hard. "Keep quiet, Billy," he answered in an equally low tone. "We must get to the bottom of this."

There was a pause during which nothing could be heard but the steady beat of the engine, the throb of the screw, and the rush of the broken water in the wake of the ship. Billy had dropped back close alongside Clem, and the two lay motionless, almost breathless.

The silence had lasted so long that Clem was beginning to be afraid that the men were not going to talk any more, when at last Gurney took his pipe from his mouth and spoke again. "What's this English chap's name, Craze? Know anything about him?"

"Not a lot," was Craze's reply, yet to the listening boys the words did not strike true. "I did hear as his name was Bandon, and that he ain't been up there a very long time. But he's got right in with the Injuns, and he's making a pile of dollars out o' skins and dust."

"And how do you reckon to track him down?"

"My information is as he's settled in a valley up in the Mammoth Range."

Gurney whistled again. "Gee, but that's a long way inland!"

"That's so," agreed Craze. "It's across the Liard River. But I reckon it's worth it."

Gurney nodded. "If it's as good as you say, it's worth a bit of trouble. But see here, Craze, do you reckon you can find the trail?"

Craze chuckled softly. "I got a guide," he said.

"What—one of the Indians?"

"No, he ain't an Injun. He's a white man. And—" he lowered his voice so that only the faintest possible whisper reached Clem's straining ears—"he's right here on this ship this minute."

Gurney started slightly. "Who is he?" he asked eagerly.

Before Craze could answer a sound of footsteps was heard, coming rapidly along the deck toward the stern, and Bart Condon's deep voice broke the silence. "You Clem, you Billy! Where be you?" Clem caught hold of Billy's arm, and the two crouched closer than ever on the top of the deckhouse.

Bart called again, but as there was no answer, went away. But when Clem ventured again to look down over the edge of his perch Gurney and Craze had vanished. "Bad luck!" he growled in Billy's ear. "Just a moment more, and we should have heard who the guide was."

"It is bad luck," agreed Billy, "but I say, Clem, we've heard quite a lot as it is. And I say, isn't it rum that this 'Bandon' they talk about is a man who has got away from the police, just like Dad?"

"Yes, it is funny," agreed Clem thoughtfully. "Only perhaps he isn't innocent as Dad was."

"I don't care whether he is or not," replied Billy quickly. "Anyhow, he's made friends with the Indians, so he can't be a bad sort. And whatever he's done, I don't see why these pigs of fellows should rob him."

"No. I'm jolly well with you there, Billy," agreed Clem. "We'd better go and find Bart, and tell him what we've heard. Anyhow, he's looking for us."

They slipped away quietly, and soon found Bart leaning over the rail, just by the companion.

"Say, boys," he remarked in his slow drawl, "hev you plumb forgotten as it's supper-time, or ain't you hungry?"

Clem looked round to make sure no one was listening. "We had something to make us forget it, Bart," he answered, then told what he and Billy had heard. Bart listened without a word, merely nodding his head once or twice. When Clem had finished he nodded again. "I reckon I can tell you who the guide is as they spoke of," he said quietly. "His name is Condon—Bart Condon."

Clem and Billy gazed at him in speechless amazement. Bart raised his head, and they saw the shadow of a smile on his broad, pleasant face. "Only he ain't going to act, sonny," he continued. He was silent for some moments, then chuckled softly. "I knowed there was something funny doing as soon as I seed them two galoots aboard. But I hardly reckoned as they knowed as much as they seems to. Wal, boys, I'm mighty glad you heard what you did, for it gives me a chance to euchre them two beauties. But I'll hev to do a right smart bit of thinking if we're to get ahead."

Billy burst out. "Do you mean that those two men were going to track us wherever we are going?"

"That's jest exactly what I do mean, sonny," answered Bart deliberately. "But that's enough talk for this time. Come right down to supper. And don't worry. I'll fix them. Yes, I'll fix them proper!"

"MY goodness, Clem, look at those mountains!" exclaimed Billy.

It was eight days since they had left Seattle, and the John P. Wilkes was still nosing her way up through the maze of islands which border the coast of British Columbia and Southern Alaska. On this morning the two boys had come up early, to find a calm sea, a blue sky, and outlined against the east a most magnificent array of snow-clad peaks. "I suppose we shall have to climb over those one of these days," replied Clem.

"Maybe sooner than you think, my lads," came Bart's quiet voice behind them.

Both boys turned sharply, but Bart gave them a warning look. "You come along down with me," he said softly, and they followed him below to the cabin they all three shared. Bart closed the door carefully. "You pack your duds, boys," he said.

"What!" gasped Billy. "Are we going ashore?"

"That's so, but there's no need to shout about it."

"I'm sorry," said Billy penitently. "But when?"

"When I do," replied Bart quietly. "You watch me, and for the Lord's sake don't let on to a soul aboard."

It was not often Bart spoke so strongly, and the boys were much impressed. They packed their things, not in portmanteaux, but in bundles, and by Bart's advice left out everything not absolutely necessary. By the time they had finished the ship was steaming up a narrow fiord with high cliffs on either side.

"We stops at the mouth of the Taku River," Bart told them. "Some of the folk'll go ashore, but you jest stay around and watch me. And don't talk, and keep your faces straight. You get me?"

They did, and said so. When they went on deck again Bart locked the cabin door behind them. Presently the John P. Wilkes was slowing down into the mouth of a river, a river of medium breadth, which came down between lofty banks covered with gigantic forest. The great trees, which were mostly evergreen, grew to a height of fully two hundred feet, and beneath them was undergrowth thick as that in a tropical swamp. To the right of the river mouth was a plot of four or five acres, with several rough frame buildings. Some Japs and a few Indians were moving about. There was a landing close to the building with nets hung on it, and boats tied up. Stakes rose from the clear water in long rows.

"This here's the Taku salmon-cannery," Bart told the boys. "Now you jest set around and don't do a thing till I tells you."

Clem and Billy—Billy in particular—were quivering with inward excitement, yet managed to carry out their orders. With much splashing and backing the steamer worked in to the wharf and tied up; a gangway was got out, and a number of cases began to be unloaded. The Japs wheeled them up to the storehouse.

Presently Billy whispered to Clem: "Gurney and Craze are watching us."

"I've noticed that," replied Clem cautiously. Gurney and Craze were close to the gangway, and they hardly took their eyes off Bart and the boys. But as the three latter merely leaned over the rail, lazily watching the deck-hands at work, the two watchers seemed to become less suspicious.

A big man wearing his trousers tucked into high boots came down from the main building and crossed the gangway. He looked round, and his eyes fell on Bart Condon. At once his big, sunburnt face lit up, and he strode across. "Why, Bart, you old son of a gun, be that you? I'm sure glad to see you!" he exclaimed.

Bart stretched out his hand. "Me too, Joe. I thought you'd be along."

"But ain't you coming ashore, Bart?" asked the other, as he wrung his friend's hand.

"Guess not," was the reply. "There ain't a lot of time," replied Bart. He turned to Clem and Billy. "Say, boys, shake hands with my friend Joe Western. He owns this here factory, and some day, when we got more time, maybe we'll stay over with him a piece."

As Bart spoke, Billy, watching him closely, saw one eyelid flicker, saw too that Joe Western seemed to understand something from this lightning wink. At any rate, the big man leaned against the rail, and began to talk salmon and nothing else. The packages were soon ashore; then some cases were brought down from the factory and stowed aboard. The boys began to feel positively ill with excitement, for they could see that in another moment or two the ship was due to leave.

The second officer came down the deck, and stopped opposite them. "We're right off, Mr Western," he said. "Gangway's just coming up. Guess you better get ashore unless you want to come along with us."

"I'd like to mighty well," smiled Western, "but I reckon I've got my job to attend to. Wal, good-bye, Bart."

Bart walked with him to the gangway, the ropes of which two men were already beginning to loosen. "You better be sharp, boss," said one of them to Western.

"So long," said Western loudly. "I'm mighty sorry you all couldn't give me a call this time." Then, with a wonderfully light step, considering how big and heavy a man he was, he sprang lightly across the gangway and on to the wharf.

The gangway was actually being raised, and Clem and Billy were divided between despair and amazement, when suddenly Bart darted forward. "Here, what are you a-doing of?" roared the man who was casting off. "Want to drown yourself, or what?"

"Come on!" hissed Clem to Billy, and before the man could stop them they had both followed Bart, and with flying leaps reached the wharf. They turned to see Gurney and Craze make a dash for the gangway. They were too late. The gangway was already half-way up, the screw was turning, and the steamer beginning to move.

"Fifty dollars if you get us ashore," the boys heard Gurney say sharply to the man in charge of the gangway.

"You better go and ask the skipper," retorted the latter, who was not in the best of tempers. At this moment a man rushed to the rail, and two heavy packages hurtled through the air, to land with heavy thuds on the wharf.

"There's your duds, boys," said Bart calmly. "Take 'em up and carry 'em to the house. We've changed our minds, and are going to stay with Mr Western a piece."

He waved his hand to the infuriated Gurney and Craze. "So long!" he said. "Better luck next time! And, Craze, when you wants a guide, you better fix up first to pay him, see?"

What Craze said cannot be printed, but Bart did not stop to listen. He turned his back and walked straight toward the house.

JOE WESTERN'S quarters were rough, but comfortable. There were plenty of bunks and plenty to eat, and after as good a dinner as they had ever put away the two boys were turned loose to explore. "Only don't you go up in the woods, young fellers," warned Western. "Not onless Bart or me goes with you. You can go out in a boat if you've a mind to, but the woods ain't healthy for tenderfeet."

So Clem and Billy started off exploring, and the first thing they came across was a huge boatload of silvery salmon fresh from the nets being carried up into the factory. Here they were gutted and scaled by Indians, then packed into cans, which were placed in huge cauldrons of boiling water. When the fish was cooked the tins were allowed to cool, then soldered up, and after being labelled were packed in cases ready for shipment.

Afterward Sam, the Japanese in charge of the boats, lent them a canoe, and they went up the river a little way to look at the stake nets. The water was alive with salmon, which were running up the river to spawn. The afternoon seemed to pass like a flash, and it was only when they began to feel hungry that the boys remembered they must get back for supper.

Supper was as good and plentiful as dinner, and when it was over Bart and Joe Western pulled chairs out on the veranda, and Clem and Billy followed.

"Do we start to-morrow, Bart?" questioned Billy.

Bart shook his head slowly. "I reckon not, Billy. Ye see, we got to have carriers, and Joe here can't spare none of his Injuns until the fishing season's over."

Billy's face showed his dismay. "But, Bart, won't Gurney and Craze come back after us?"

Bart nodded. "Ay, they'll come back, but it's going to take them quite a while."

"But, surely, the sooner we get away, the better," said Clem seriously. "If Mr Western would lend us a canoe, we could take our things in it all right, couldn't we?"

Bart nodded again. "Yes, sonny, we can take 'em as fur as the water'll let us. But that ain't where we're bound for. There's two hundred mile and more of mountains to cross after that. And it ain't as if you and Billy could heft a forty-pound pack over country like that."

"We could with practice," vowed Billy.

Joe Western spoke. "Five years' practice, Billy. No less. I guess you'll jest have to settle down to wait a piece. I'm mighty sorry, but it can't be helped."

His tone was so decided that the boys felt it was no use arguing. They got up and moved away toward the river. It was dark now, but the night was beautiful, calm and still, and a wonderful hush brooded over the great forests that sloped so steeply to the swift river.

"Hulloa, here's Sam!" exclaimed Billy. The Japanese, who was sitting in a boat busily sharpening a big three-pronged spear, looked up.

"You like go with me?" he asked in his polite way.

"Rather!" said Billy. "Where are you going?"

"I go hunt dogfish," he answered, lifting the spear. The boys tumbled in in a twinkling, and took the oars; then, under Sam's directions, they pulled out into the middle of the river, stopped, and let the boat drift. Sam pointed downward, and a wonderful sight met their eyes. The water was smooth here and clear as glass, and the depths were alive with huge fish, each about four feet in length. These were outlined in gleaming phosphorescence, and were moving to and fro in the most curious and intricate patterns.

"They dogfish," explained Sam. "They hunt salmon. We hunt them." As he spoke he stood up, raised the spear, and suddenly dashed it down into the water with all his force. Next moment it was nearly wrenched out of his hand, but he held on hard, and up came a writhing monster like a small shark.

"You try," he said to Clem, and Clem eagerly took the spear. He waited, watching his chance, then struck hard, and instantly felt the barbed prongs fasten in a fish.

But he had not in the least realized the weight and strength of the creature. Sam made a snatch at him, but was just too late. Over went Clem, head foremost, and with a tremendous splash disappeared under the cold, swift-running water.

Billy gave a yell of alarm. "Quick, Sam, catch him!" he cried. "He can't swim!"

It was true. There had been no swimming-bath at Wasperton, and neither of the boys had ever had a chance to learn to swim. But it was too late for Sam to catch Clem, who, still grasping his spear, had gone clean under.

The plucky Jap did not hesitate an instant. He simply dived clean over the side and vanished in Clem's wake. Billy, left alone, did not lose his head, but turned the boat in the track of the line of bubbles which he saw rising. Suddenly the water broke, and to his intense relief he saw Sam rise, holding Clem by the back of his shirt.

Billy drove the boat alongside and Sam caught hold of the gunwale. "Help pull him in," panted Sam, who was evidently badly blown by his deep dive.

Billy sprang to obey, but in his haste knocked one oar overboard. He did not wait to recover it, but grabbed hold of Clem, and with a great effort managed to hoist him on board. Then he helped Sam into the boat. "I say, that was fine of you, Sam!" he said gratefully. But Sam, after giving himself one shake like a wet dog, turned his attention to Clem.

Clem had swallowed rather more water than was good for him, but otherwise was little the worse. His trouble was that he had lost his spear, and this he at once began to apologize for.

Sam cut him short. "We get back," he said in his good but curiously clipped English. "We get back quick. Give me oars, please."

"I'm sorry," said Billy, "but one's gone overboard. We shall have to drop down a bit and pick it up."

Sam snatched up the remaining oar, and pushing it out over the stern, set to sculling frantically toward the bank.

Billy was astonished. "Why, what's the matter?" he demanded. "What's the hurry?"

"The tide come," replied the other breathlessly. "Tide come quick."

Neither Billy nor Clem had the faintest idea what Sam was talking about, but they could both of them see that he was very much upset, and desperately anxious about something. Yet the sky was clear, there was no wind, the air was quite warm. They could not make head or tail of it.

Sam sculled with a sort of fierce desperation; but the current was strong, and the boat, a big flat-bottomed affair, was heavy and clumsy, and for every foot she got in toward the bank she drifted three downstream. As there was not another oar in the boat the boys could not help him. All they could do was to wait and wonder what the danger was.

They had not very long to wait. The boat was still quite fifty yards from the bank when suddenly the current which had been sweeping her downstream seemed to be stopped short. It simply ceased to exist, the effect being first as though great lock- gates had been suddenly closed. But before Sam could take any real advantage of this change there came a curious hissing sound out of the soft darkness in the direction of the sea.

In a flash Sam ceased his efforts to reach the bank, and with a mighty swing turned the boat so that her bow faced straight downstream. And still the boys stared blankly.

The hissing grew louder, and suddenly Billy pointed. "The wave!" he cried. "Clem, the wave!"

Clem stared, hardly able to believe his eyes. For there, racing up from the sea, was a wave at least eight feet high and filling the whole river from bank to bank. It was not the least like a storm wave, for it was smooth as glass, but the pace at which it travelled was simply amazing. It came pretty nearly as fast as a horse could gallop. What made it all the more startling and even terrifying was the phosphorescence which tipped this wall of water with a rim of bluish light.

"I know," gasped Billy. "It's a bore—a tidal wave." It was the last thing he said for some time, for next instant the wave was upon them.

The boat rose until it absolutely stood on end, and the boys were forced to clutch at the thwarts to save themselves from being flung out backward. The last thing that Billy and Clem heard was a loud shout from Sam: "Hold to the boat! Hold tight!"

"Hold to the boat! Hold tight!"

Then the heavy craft was literally up-ended. She capsized, and all the boys knew was that they were under water, and ripping through it at a fearful pace.

Half-choked, blinded, chilled to the marrow, Billy hung on like grim death, and just when he felt that he could cling no longer, suddenly found his head above water. "Clem!" he cried hoarsely. "Clem!"

"All right. I'm all right," came Clem's half-strangled reply, and there, to Billy's intense relief, he saw Clem clinging to the opposite side of the boat.

"Where's Sam?" was Billy's next question.

"Don't know. I say, he must have been swept off!"

That was clear enough, for there was no sign of him anywhere.

"Do you think he's drowned?" asked Billy in an awed voice.

"He swims like a fish," said Clem comfortingly. "I expect he'll get ashore. We weren't far off it when the wave caught us."

"And where are we going now?"

"Up to the head of the river by the look of it," said Clem grimly.

The wave was gone, or rather it was ahead of them, but the boat, and they with it, was travelling up the river with the speed of a steam-launch. Already the lights of the factory were a long way behind.

Presently Clem spoke again. "It's rotten, our not being able to swim," he grumbled.

"I'm jolly well going to learn," said Billy.

Clem did not answer. What he was wondering was whether he and Billy were ever going to have the chance.

ALL this time the boat had been going right up the middle of the river, but now they were coming to a bend, and suddenly she swung to one side. An eddy caught and spun her, and there was a bump which nearly shook the two boys from their hold. "We've struck something," cried Clem.

"I could have told you that," replied Billy dryly. "It's a log, a big dead tree. I've got hold of a branch. I believe I can shove her inshore."

The boat was heavy, and even under the bank the tide rip was strong, but Billy pulled with all his might, and Clem helped. Good feeding had made a wonderful lot of difference to the two, and they were twice the boys they had been a month ago. Gradually the heavy boat yielded to their combined strength, and swinging again, bumped into the bank, ramming her blunt bow deep into the earth. "It's all right, Clem," said Billy cheerfully. "I've got my feet on the bottom. It's firm sand. Come on!"

"Wait," said Clem. "We mustn't let the boat go."

"She won't move. She's jammed. Let's get out of the water. I'm nearly frozen."

They climbed out on to the bank. "It's fine to feel firm ground under one's feet," said Billy, as he stamped about to try and get the blood moving again. Though the night was not cold the water had been cruelly so, and both the boys were fairly numbed.

"And what do we do next?" asked Clem rather glumly, as he looked round at the huge trees towering toward the stars.

"Walk back to the landing quick as ever we can," answered Billy. "We've got to find out whether poor Sam is safe."

"There won't be any very quick moving in this wood," returned Clem. "Did you ever see anything so thick? It's more like a tropical jungle than anything else. I never thought for a minute we'd find anything like this so far north."

"It's different once you get across the coast ranges, Bart says," replied Billy; "but let's try what we can do. If we keep close to the river we can't lose our way. And anyhow, we shall get warm."

Billy never said a truer word, for very soon they were both simply dripping with perspiration. The going was awful, and the darkness made it fifty times worse. Billy had a torch, but the water had got into the battery and spoilt it. Their matches too were soaking, for they had not yet learned the trapper's trick of keeping them dry in a corked bottle. The steep bank was simply littered with fallen tree-trunks, some of enormous size, and all grown over with moss and long grass and bush of every sort, mostly prickly.

Some trunks were still sound, but most were perfectly rotten, so that when they stepped on them they crumbled to tinder and let them down into wet and slime. Add to this that the ground was full of deep cracks and rifts cut by winter storms, and broken by boulders and jutting crags, and you may begin to have some idea of the difficulties confronting the unlucky travellers.

"Don't wonder Joe Western said this brush was no place for tenderfeet," panted Billy as, for about the fifteenth time, he went blundering into a hidden pit. "I say, Clem, we'd better work uphill a little. It looks better than down here by the river."

Clem agreed, and they climbed the steep slope. Here the fallen trees were not quite so thick, but the undergrowth was thicker than ever.

Billy, who was leading, came to a steep place, slipped, and tried to save himself by clutching at a big, wide-leaved plant which stuck out dimly in front of him. Clem heard him give a sharp cry of pain, and caught him as he fell backward. "What's the matter?" he asked anxiously.

"Something bit me," replied Billy, in a voice hoarse with pain. "I—I'm afraid it was a snake."

For a moment Clem was so scared that his mouth went dry and he could not speak. But he quickly pulled himself together. "It can't be a snake, Billy. There are no poisonous snakes up here—not even rattlers. Bart told me so. You've been stung by something."

"It's something pretty poisonous, then," replied Billy, who was holding on tightly to his injured arm. "I say, Clem, it does hurt."

"Come down nearer the river. There's a bit more light there. Let's have a look at it."

Billy was quite sick and shivery with the pain, and Clem had to help him down the steep hillside. They found a little opening, but even there the light was very dim. Still, there was just enough for Clem to see a dark, inflamed patch on Billy's hand and wrist. "It's a sting of some sort," he said. "Like a nettle, Billy, only worse. Come on down to the water's edge and dip it in the water."

Billy did so, and after a bit the cold water took the worst of the pain away. But the arm was swollen and almost useless, and Clem had to help Billy along. So progress became slower than ever, and in the next half-hour they travelled only a few hundred yards.

"If Sam got ashore he'd have been back at the factory long ago," said Billy at last.

"Not if he'd landed in this sort of stuff, Billy," replied Clem, but all the same he was very uneasy. They struggled on a bit farther, then both came to a sudden stop.

"What's that?" whispered Billy sharply, pointing to two dots of green fire which glowed through the darkness a little way up the hill above them.

"A wild beast of some sort," answered Clem, in a voice which he found rather difficult to keep steady.

"A—and we've got no gun," said Billy. "What shall we do?"

"Yell at him," suggested Clem desperately.

The noise which the two boys made between them was enough to scare the hide off almost any inhabitant of the woods. At any rate, the owner of the eyes removed them and itself abruptly, but without the slightest sound of its going.

"I wonder if it was a panther," questioned Billy.

"Just a wild cat, I expect," replied Clem hopefully. "But I say, Billy, let's get down close to the river again. I do hate this wood."

"So do I," agreed Billy, and turned downhill again. When they got well down to the river's edge they found themselves on the top of a steep bluff ten or twelve feet high, which dropped to a beach of sand and shingle. At this time of year, well on in August, the June floods were long past, and the autumn rains had not begun. So the river was at its lowest. At low water there would have been plenty of room to walk along under the bluff, but now the flood tide was beginning to cover the little beaches.

Billy stopped and looked over. "If we got down there on the gravel, we could shove along quite fast," he said.

"We should go an awful purler if we tried to climb down that bluff," Clem objected. "Let's go a little farther and see if there's a way down." Billy agreed, and they pushed on slowly.

A little point of land ran out into the river, and crossing this, they saw below them quite a broad strip of almost level shingle. They saw something else too. A little farther on, a figure was standing on the beach in a queer crouching position, bending over the water and apparently trying to rake something out of the river with one hand. In the dim starlight it appeared to be a short, broadly built man. Billy clutched his brother's arm. "It's Sam," he whispered.

"I'm not so sure," said Clem. "He looks to me bigger than Sam."

"Yes, he does look a whacking big chap," admitted Billy. "Come a bit nearer, and let's see before we shout."

As they moved forward, the man by the water seemed to grow larger. He certainly was enormously broad. By this time the boys had had such a fright that they were both getting nervous. Though they would not confess it, they each had a sort of suspicion that this might be a wild Indian. They reached a point exactly above the spot where the queer-looking fellow was still groping in the water, and Clem, catching hold of a branch, bent forward to get a better view. There was a sharp crack, the bough broke short off, and Clem, losing his balance, toppled forward and fell right over the edge of the little bluff.

Billy saw him land with a thud on the shingle. As he did so, the figure by the water reared up sharply and whirled round, and Billy was nearly frantic when he saw its huge, shaggy shape. "A bear!" he gasped, and forgetful of his injured hand and the fact that he had no weapon—not even a knife—made a flying leap down to the beach to Clem's rescue.

It was a bigger drop than Billy had supposed, and he came down so heavily that he pitched face forward on the shingle and lay half stunned. When he recovered Clem was kneeling beside him, anxiously asking, "Billy, are you hurt?"

"N—no," gasped Billy. "I—I'm not hurt, b—but where's the bear?"

"Gone. When you came down flop, like that, he simply hooked it."

"Hooked it?" repeated Billy in a bewildered voice. "I—I thought bears were dangerous."

"This one wasn't. You wouldn't have believed that such a clumsy-looking brute could travel so fast. He simply vanished." He paused. "But, Billy, it was awfully decent of you to come to help me," he added.

"Fat lot of good I could have done!" returned Billy gruffly. "I haven't even got a knife."

"That don't matter," said Clem. "It was a jolly plucky thing to do."

"Shut up, Clem!" growled Billy. "We've got to get home."

"I'd like to know how," said Clem ruefully. "Now we've got down this bank, it's going to be a sweet job to climb up it again. And I'm just about fed up with that wood. I've a jolly good mind to camp here till daylight."

"Not good enough," replied Billy decidedly. "We're both as wet as can be, and we can't light a fire. We shall only get fever, or something nasty of that kind. Come on. It can't be very far."

Billy was so plucky that Clem felt a little ashamed. "Right you are," he said. "I'll give you a leg up."

Billy got to his feet. To say truth, he felt horribly shaky, and his arm was hurting abominably. But he set his teeth and vowed to himself that somehow they would get back.

Clem gave him a back, and he grabbed a branch and tried to scramble up the bluff. But the bough broke and let him down. He had another try, and this time got hold of a thick tuft of grass, only to have the whole thing come out by the roots and drop him once more to the shingle. "I've half a mind to do as you say and chuck it, Clem," he said at last. "There doesn't seem to be any foothold."

"We can't, Billy," replied Clem gravely.

"Why not, I should like to know?"

"Because the tide's still rising, and in about half an hour all this shingle will be under water."

"That settles it then," grumbled Billy. "You—" He stopped short and flung up one hand. "Listen!" he cried.

"Hi—yah! Hulloa!" The shout came ringing faintly up the river out of the darkness, and both boys spun round, and stared breathlessly in the direction from which the sound came.

"Hi—yah!" came the call again, and Clem managed to collect his scattered senses and answer. His ringing "Hulloa!" sent the echoes flying weirdly up the steep hillside among the giant trees.

"It's Bart," said Billy sharply. "What luck!" Then he too shouted at the top of his voice.

"That you, Billy?" came Bart's voice.

"Yes, and Clem," answered Billy. "Here we are—on the beach. Pull on. We're a good way up."

There was a splash of paddles, and soon a canoe paddled by two Indians came shooting up at a great pace. Billy thought that the sound of her bows grating on the shingle was the pleasantest he had ever heard.

"You all right?" questioned Bart as the boys came clambering in, and both of them could plainly hear the anxiety in his tone.

"Right as rain," answered Clem; "only Billy got stung by something. But Sam—is Sam safe?"

"Sam's all right. Trouble was, the tide swept him right across the other side of the river and it was an hour before anyone heard him shouting. Whar did you boys land up?"

They told him, while the two Indian paddlers drove the canoe swiftly back down the river. It was but a very few minutes before they were safe on the wharf again, where they were met by Joe Western. He took them straight to the house, and made them each take five grains of quinine, washed down by big mugs of steaming hot coffee. Then they had to tell their story all over again.

"Stung, was you?" said Joe. "No, it warn't no snake. I reckon it were that 'devil's club.' Let me see. Aye, that's it. Like nettle, only a sight worse, but I guess I got some stuff as'll take the pain out."

He went to a shelf, took down a bottle, and putting some of the contents on a rag, applied it to Billy's hand and arm.

"Why, it's wonderful!" exclaimed Billy. "It's taking all the pain away. But I say, I didn't tell you we met a bear."

"Met a bear!" repeated Joe. "What sort was he?"

"He didn't stop to tell us," answered Billy. "He simply cleared out."

Joe burst into a great laugh. "I reckon he was only a third- class bear," he chuckled. "But it might ha' been different ef you'd have met his big brother."

"Tell us," begged Billy.

"Not to-night, son. You get right to bed. I'll tell ye to- morrow, and mebbe I can show ye one in the daylight."

"WHAT'S the barrel for?" demanded Billy. Joe Western and Bart, together with the two boys, were tramping up a steep, narrow trail through the woods on the day following their adventure on the river, and Joe was carrying on his great shoulder an empty molasses barrel.

Joe laughed. "All in good time, son. I'm a-going to try to show ye a bear."

That was all the boys could get out of him, and anyhow they had not much breath left for asking questions, for the path they were following was somewhat steeper than the roof of an average house. It wound up the hillside among trunks of trees which were the biggest that Clem and Billy had ever seen.

They were mostly Douglas fir, and towered fully two hundred feet toward the blue sky. Some of the stems were so huge that it would have taken five grown men to encircle them with outstretched arms.

What utterly amazed the boys was that now and then humming- birds flashed like living jewels above the tangled undergrowth, while other birds that looked like canaries flitted in front of them. And yet they were farther north than the most northern point of Scotland.

At last, very hot and very blown, they came to more open ground above the heaviest belt of forest.

"Guess I've carried this here barrel about far enough," remarked Joe, and dumped it down just on the edge of the steepest part of the slope and under cover of a low, spreading birch-tree. Then he walked straight on without offering any explanation. His long legs covered the ground at a great pace, and Clem and Billy were both grateful when at last he stopped close to a big tree, and pointed to the trunk.

"See anything, Billy?" he asked.

"Yes," replied Billy, staring with interest at the tree. "The bark's all torn."

"My word, that was a big one, Joe," said Bart.

"A big what?" asked Clem.

"A big bear, Clem."

"You don't tell me that was a bear?" exclaimed Clem. "Why, the bark's all torn up to a height of ten or eleven feet!"

"It was a bear all right, son," said Joe. "What I calls a first-class bear."

"It must be a giant," said Billy in an awed voice.

"A 'silver tip,'" explained Bart. "Grizzly's the name the books give him. We get 'em mighty big here. Some of 'em is as large as an ox, and a sight heavier."

The boys could not answer. They only stared at the clawed trunk.

"Then there's second-class bears," said Joe. "Them's the cinnamons, and cunning chaps they are. The third class is the brown bears, same as you met last night. But set yourselves down," he continued. "We'll rest awhile and eat our grub."

He took a great packet of sandwiches from his pocket. They were of baking-powder bread with cold fried bacon and mustard inside, and very good indeed. While they ate he told them more about bears. "The Injun calls the bear his brother," he said, "and there's one thing you boys got to remember. If you're in camp with Injuns, don't you go mentioning 'bear.' It ain't good manners, according to the Injun way of thinking. You can talk of 'Mister Fur-Jacket' or anything o' that sort, but don't say '‘bear.'"

"But if we meet a grizzly, what do we do?" asked Billy.

"Walk right on and don't take no notice. Onless he's mighty hungry or got het up about something, he ain't a-going to hurt you."

Billy stared. He had always supposed that wild beasts went for you on sight.

"Same with all the rest o' the wild things," continued Joe. "They won't meddle with man onless they're in bad need of food. Only don't you leave your stores unguarded, for that's Mister Bear's chance, and he'll eat 'em all."

He stopped, and the boys saw that he was listening keenly. Suddenly he jumped up. "I said I'd show you a bear. Come right along. But quiet now. Don't you make a noise. Watch where you set your feet."

It was the boys' first lesson in woodcraft, and neither had ever had a notion how difficult it was to walk quietly until they tried to imitate Bart and Joe Western.

Joe led straight back to the spot where they had left the sugar barrel, then motioned them to a hiding-place among some shrubs. He pointed, and through a little opening the boys saw the oddest sight imaginable. A bear, a great big beast that must have weighed four or five hundred pounds, was busy with the barrel. He had turned it over on its side, and was lying by it, with his head right inside, licking the sides of it. They could hear him smacking his lips and grunting delightedly. He was evidently enjoying himself hugely.

Gradually, as they watched, he worked farther and farther in until his head and shoulders and forepaws were all inside the barrel. A very tight fit it was, but Mister Bear didn't seem to care. He was having the time of his life.

Now the barrel, as has been mentioned, had been left on a little ledge with a very steep slope below it. The bear, in his efforts to get the last lick of molasses from the bottom, had at last wedged half his body into the barrel, and in doing so had managed to turn the barrel right round, so that the butt of it projected over the lower side of the ledge. But he, of course, could not see his danger.

Suddenly the barrel went over the edge. Poor bear was far too tightly packed inside it to get out in time, and he went with it. Next instant barrel and bear were rolling downhill, spinning like a Catherine-wheel.

"Oh, he'll be killed!" cried Billy, jumping up.

Joe Western burst into a great roar of laughter. "Did you ever see the like of that, Bart?" he asked.

Bart's face was one great grin. "I never did, Joe. Say, let's see where he lands up."

Next minute all four were running helter-skelter down the hill in track of barrel and bear. For a wonder, this part of the slope, though steep, was fairly smooth, and they were just in time to see bear and barrel strike a patch of scrub fifty feet below and go through it like a shell.

"Gee, but old bear must be getting dizzy!" chuckled Bart as he went striding down the hillside. "Billy," he shouted, "don't you go too fur ahead. That beast'll be madder than a burnt cat when he gets loose again."

Billy didn't hear. He was ever so far ahead, racing along, jumping everything in his path. Clem was close behind him. Below the scrub was another sharp descent, ending in a sheer drop of ten or fifteen feet. The barrel and the bear whirled down the steep at dizzy speed.

"Clem, he'll be killed!" shrieked Billy as he saw the barrel whizzing toward the edge of the drop.

"So will you, if you don't stop!" yelled back Clem, flinging himself flat on the ground.

Billy would never have been able to stop if it had not been for a small tree which he was able to grab hold of. The barrel reached the edge of the little cliff, hurtled through the air, fell with a crash upon the hard ground fifty feet away, and instantly went to splinters. Staves flew in every direction, forming a sort of rainbow round the unfortunate bear.

Billy, gazing with all his eyes, was amazed to see the bear pick himself up and stand, shaking his head in a muddled sort of fashion, yet seemingly very little the worse.

"Lie down, Billy!" came Bart's voice behind him, curt and sharp, and Billy dropped like a flash. "He's mad as a hornet," muttered Bart. "He'll go fer anything as moves."

And just then something did move. Out of the trees, not twenty yards below where the bear was standing, a man appeared—a white man who wore knee-boots, blue jeans, and a dark blue flannel shirt.

"Look out!" yelled Bart.

It was too late. With a deep, rumbling growl, the bear lowered his pig-like head, and charged straight at the stranger. The stranger turned and ran for dear life. He was a long, lanky fellow of at least six feet, and the pace he made was surprising. So was that of the bear. You would never have believed that so clumsy-looking a beast could have gone so fast.

Clem and Billy stood at the top of the little cliff and stared. For the moment they were too surprised to do anything else. It was Bart who roused them from their trance. "The blamed fool! He'll be mauled!" he snapped out, and down he went over the ledge, climbing like a cat in spite of his heavy build.

Joe Western followed, and the boys were nearly as quick.

By this time the long man and the bear were both out of sight among the trees, but the others could still hear the crashing of heavy bodies through the undergrowth. Suddenly the sound ceased, but was followed by a terrifying growl from the bear.

"By gum, the brute's got him!" panted Joe Western, tearing onward at top speed. It was all that the two boys could do to keep up. All together, the four burst through the trees into another open space. The first thing they saw was the bear's hindquarters disappearing among the lower boughs of a small cedar, while up above the branches were being violently shaken.

Bart stopped short. "Treed!" he cried, and a broad grin spread over his jolly face.

"B—but the bear will catch him," gasped Billy, as he caught a glimpse of the long man going up through the branches at the rate of many knots.

Bart, however, did not seem seriously disturbed. "Guess there ain't much danger," he observed. "That there's no bear tree."

Clem look puzzled, but Billy's quick wits grasped Bart's meaning. "It's not big enough for the bear, Clem," he said. "The branches won't hold him very far up."

Sure enough, the bear, which was very fat and must have weighed all of five hundred pounds, had already reached a point where his weight was making the whole tree sag. It was quite a small tree, and under the combined weight of man and bear was beginning to bend right over. Quite near the top, the long man was clinging to the trunk, both legs and one arm wrapped tightly around it. He was scared to death and very angry, and the expression on his lantern-jawed face was so funny that the boys could hardly help laughing.

"But what are we going to do about it, Bart?" asked Clem. "It's all very well to laugh, but that beast is jolly near him. Look at him, reaching up with those great claws of his!"

"Help!" roared the man in the tree. "Don't stand there, a- laughing like ijiots! Shoot him, why don't ye?" As he spoke the bear made a blow at him with one great paw, but could not quite reach, and the stranger scrambled wildly another two feet higher, then stuck fast among the small twigs. The tree bent like a fishing-rod.

"Guess we'll hev to shoot him, Bart," said Joe Western, as he pulled a long-barrelled pistol from the holster he wore at his belt.

"Don't you do it!" cried Bart. But he spoke too late. Joe's action in pulling the pistol and firing was all one—so quick that the gun was hardly out of its holster before the sharp crack of the report went echoing all down the hillside.

The bear, shot clean through the head, released its hold, and fell like a sack, crashing through the thick branches. All in a flash the boys realized why Bart had shouted, for the tree, relieved of the ponderous weight of the great beast, shot up like an uncoiled spring, and with such force that the long man was torn from his hold and flung into mid-air as if shot from a catapult.

"Ow!" His terrified yell rang through the warm air; then he vanished into a thick patch of scrub.

"That was a fool trick, Joe," said Bart, as he ran forward. "He'll be lucky if he ain't as dead as the bear."

Billy was the first to reach the spot where the stranger had fallen, and plunged into the thicket. "It's all right," he cried shrilly. "He's fallen in a mud-hole. He's not dead."

"Then he ought to be mighty grateful," said Bart dryly.

But the long man was not grateful at all. On the contrary, he was very angry indeed, and the language he used was not pretty or nice. Indeed, it was so bad that Bart shut him up pretty roughly. "You'd ought to be thanking your stars as you're alive instead o' cussing like that," he said, and the boys had never yet heard their friend speak so sternly.

The other shut up, but for a time was very sulky. It was not until they were nearly back at the landing that he recovered his temper and began to explain who he was and where he came from.

"MY name is Pelly," he said. "Ed Pelly, come down from Juneau in a dug-out. Jest landed a couple o' hours ago. Thet little Jap feller o' yours, he told me I'd find you up the hill, so I walked up arter you. But I didn't reckon as I'd meet up with that there dratted bear it a-rolling down the mountain like a pea in a drum."

He paused. Clem and Billy were aching to ask him what he had come for, but they had been in the North-West just long enough to know that it is the height of bad manners to ask personal questions.

Joe Western spoke. "You looking for a job?" he asked politely.

"No, sir. I got my job fixed. I'm a prospector, and a chap in Dawson told me as there's good gold in the ranges beyond the Liard. I got my grub stake, and I reckon to go up the river and get fixed on the ground before the freeze-up."

"Why, we're going up the river!" broke in Billy.

Pelly looked at him with interest. "Is that so? And when were you reckoning to start?"

"As soon as we can get Indians," replied Billy.

"Wal now, I got two Injuns," said Pelly, and turned to Bart. "Mebbe we could fix to join up fer the trip?"

"Mebbe we could. I'll let ye know," replied Bart, but though his tone was perfectly polite, it was not by any means cordial. Billy felt somewhat snubbed, and said no more.

They took Pelly to the house, and while Joe gave him food and drink, Bart took the boys out again. "Guess we better go and skin that bear," he said. "It'll be about all we can do before dark."

As they toiled up the hill again Clem and Billy noticed that Bart was even more silent than usual. They wondered what he was thinking about, but he gave no sign. When they got near the spot where the dead bear lay, Bart stopped short. "Seems someone has got ahead of us," he said dryly.

Sure enough, a man was squatting beside the carcass, and as he rose to his feet they saw he was an Indian. He was rather short, squarely built, and wore a pair of cheap store trousers and a flannel shirt. Yet Bart looked at him with interest. "A Stick Injun!" he remarked. "Comes from the inside country," he explained.

The Indian saluted them gravely. "Klahowya!" he said.

Bart answered with another word, "Tillicum!" and there was an almost pleased expression on the Indian's wooden face.

"Me Ahkim," he said. Then, pointing to the bear, "Hyas bear," he observed.

"Hyas fat," Bart agreed. "We want um skin. You take um fat and sinews."

The Indian actually smiled, but as Bart afterward told the boys, the Indian loves nothing better than bear-fat, while he uses the sinews for a dozen purposes. In a trice he was busy skinning the bear; when this was done, the four, between them, roped the carcass and hoisted it into a tree out of reach of wolves and foxes.

With the skin on his head, the Indian followed them down the hill, and on the way he and Bart talked, but the boys could not understand much of what was said. Bart, however, seemed pleased, and when they got back he told the boys why. "He's a-going up the river. He'll come with us. If we can get one more man I guess we shall do."

"Pelly has two," said Billy. "If we join forces, shan't we be all right?"

Bart frowned slightly. "Guess I don't know a lot about Pelly," he said briefly. And for all the rest of the evening he remained curiously silent.

Early next morning Clem and Billy were down by the river examining Pelly's dug-out when its owner came behind them. "She's a real good boat," he said, "but a mite too heavy for river work. I'm reckoning to trade her with one o' the Injuns fer a bark canoe."

He pointed out the difference between his boat, which was hollowed out of a single great log, and the light birch barks used for river work. They chatted a while; then Pelly said suddenly, "Say, I wish you boys was going along with me."

"I wish we were," replied Billy.

Pelly laughed, then shrugged his shoulders. "Your boss, Mr Condon, he don't seem to trust me. Not as I blame him. He don't know nothing about me, and up here folk don't carry testimonials around in their wallets."

Not quite knowing what to say, the boys remained silent.

Pelly changed the subject. "Say, now, how'd ye like to go hunting with me to-day? I got to get some meat fer my Injuns afore starting, and I was reckoning to shoot a moose or mebbe a sheep. They do say there's plenty up the mountain."

"Oh, let's go, Clem!" cried Billy.

"We must ask Bart first," replied Clem.

"Yes, you jest go along and ask him, then we'll start right off," said Pelly.

But Bart was not in the house. He and Joe had gone out together, and Sam did not know where they were.

"He won't mind, Clem," said Billy.

Clem looked doubtful. "Bart doesn't cotton to Pelly," he answered.

"He doesn't want to travel with him. That's all. You see, Clem, Bart won't tell even us where he's going to, and that's why he doesn't want anyone else with him."